Self-Governed Interorganizational

Networks for Social Change:

A Case Study of the Criminalization of

Online Sexual Grooming in Malaysia

Keren Acevedo

Rachel Kuilan

Main field of study - Leadership and Organization

Degree of Master of Arts (60 Credits) with a Major in Leadership and Organization (One-Year) Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organization for Sustainability (OL646E), 15 Credits Spring 2019

Thesis title: Self-Governed Interorganizational Networks for Social Change: A Case Study of the Criminalization of Online Sexual Grooming in Malaysia Authors: Keren Acevedo, Rachel Kuilan

Main field of study - Leadership and Organization

Degree of Master of Arts (60 Credits) with a Major in Leadership and Organization (One-Year) Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organization for Sustainability (OL646E), 15 Credits Spring 2019

Abstract

Cross-sector collaborations in the form of self-organized interorganizational networks are key mechanisms to address complex social sustainability problems in a systematic manner with accelerated and effective results. Self-organized interorganizational networks allow for collaborations through low degrees of hierarchy and bureaucracy while achieving high levels of ownership and commitment among member organizations. These type of networks have proven useful to achieve policy reforms to tackle societal problems related to rapid evolving and internet related crimes affecting children. This study analyses the initial conditions and emergence of self-organized interorganizational networks, as well as the structural arrangements and governance structures that facilitate the network organization. To do so, the authors used as case study the criminalization of online sexual grooming in Malaysia that resulted in the Sexual Offences Against Children Act 2017. The analysis of the case was conducted through a qualitative thematic analysis based on semi-structured interviews to 11 leaders of some of the organizations that collaborated by producing public awareness, educating about the implications of this type of crime, and simultaneously, drafting and passing the new law. The results of the study showed that the network in Malaysia was formed and organized organically through a combination of informal and formal methods and structures guided by a high sense of shared purpose and shared leadership.

Keywords: self-organization, interorganizational networks, cross-sector collaborations, governance structure, criminalization, online sexual grooming, social sustainability

Table of Contents

1. Introduction 1

1.1 Background 1

1.2 Previous Research 2

1.3 Problem Statement and Aim of the Study 2

1.4 Layout 3

2. Theoretical Background 4

2.1 Interorganizational Network Governance Structures 4

2.1.1 Formation of Interorganizational Networks for Cross-Sector Collaboration 4 2.1.2 Organization of Interorganizational Networks for Cross-Sector Collaboration 5

2.2 Kotter’s 8 Steps for Change 7

3. Research Design 9

3.1 Qualitative Case Study as a Research Method 9

3.2 Data Collection 9

3.3 Data Analysis 11

3.4 Reliability and Validity 12

4. Object of Study 13

4.1 The Online Sexual Grooming Process 13

4.2 Criminalization as Mechanism for Prevention of Online Sexual Grooming 13 4.3 Criminalization of Online Sexual Grooming in Malaysia as a Case Study 14

5. Analysis 16 5.1 Network Formation 16 5.1.1 Initial Conditions 16 5.1.2 Methods of Emergence 18 5.2 Network Organization 20 5.2.1 Structural Arrangements 20 5.2.2 Governance Structure 23 5.3 Additional Themes 24

5.3.1 Iterative Process for Legislation 24

5.3.2 Operationalization of New Laws 25

6. Discussion 27

6.1 Discussion on how effective collaborations for social change can be formed and

6.2 Discussion on how actors in a network for social change interact and relate to each other 28

6.3 Justification and Relevance of Study Findings 29

6.4 Discussion of Limitations 29

6.5 Implications for Southeast Asia and the Pacific 30

7. Conclusion 32

References i

Appendix 1 vi

Appendix 2 ix

List of Figures

Figure 1: Theoretical conceptual framework to study the formation and organization of

interorganizational networks ... 7 Figure 2: Type of emergence of the different relationships in the interorganizational network in charge of the criminalization of OSG in Malaysia ...19 Figure 3: Structural arrangements of the different relationships in the interorganizational network in charge of the criminalization of OSG in Malaysia ...21 Figure 4: Governance structures of the different relationships in the interorganizational network in charge of the criminalization of OSG in Malaysia ...23

List of Tables

Table 1: List of participants involved in the interview process per organization including size in numbers of employees ...11 Table 2: Summary of roles played by key partners in the interorganizational network in charge of the criminalization of OSG in Malaysia ...22

List of Abbreviations

NAO – Network Administrator Organization NGO – Non-Governmental Organization OSG – Online Sexual Grooming

1

1. Introduction

1.1 Background

In order to overcome the complexity arising from sustainability challenges, cross-sector collaborations are needed to bring about change in a systematic way. Such collaborations can support in generating reform movements to address gender equality issues or providing justice for marginalized groups, among other social problems. These multi-actor collaborations, also known as interorganizational networks (Stone, Crosby & Bryson, 2010), are needed to produce efforts that typically exceed the capacity of a singular organization (Clarke & Fuller, 2010). Engaging multiple stakeholders allows for the integration of various perspectives and resources that, when combined with the increasing rate of technology advances, can support in quickly iterating and adapting to address the challenges (Becker & Smith, 2018).

Interorganizational networks that serve as cross-sector collaborations bring together players from the public, private, and voluntary sectors towards a common goal, using processes, structures, and strategies to build a legitimate governance (Bryson, Crosby, & Stone, 2015). Contrary to formal development of collaborative governance, which uses careful advanced articulation and designation of roles and responsibilities, in an emergent or self-organized development, the “understanding of mission, goals, roles, and action steps emerges over time as conversations encompass a broader network of involved and affected parties and as the need for methods becomes apparent” (Bryson et al., 2015, p. 653).

Hierarchy of self-organized collaborations tends to be more horizontal, in that all involved parties apply shared leadership (Fosler, 2002). Because these informal types of collective management are often not characterized by one party imposing control over others, decision making processes are shared among all parties involved (Thomson & Perry, 2006). Since partners in self-organized informal networks share a higher commitment towards resolving challenges requiring collaborative action, they are more willing to align their agendas towards a common objective, surrender autonomy and allocate resources equally (Thomson & Perry, 2006).

Self-organized interorganizational networks can support in advancing social sustainable development by providing an accelerated platform where leaders can push transformational agendas without necessarily requiring contract-based partnerships. This type of network can also be used in an informal and temporary way to leverage political and socioeconomic circumstances to create new policies and achieve social changes, as was the case of the criminalization of online sexual grooming in Malaysia, presented in this study.

Online sexual grooming (OSG) is the process by which an adult builds a relationship with a child, significant adults close to the child, and the environment through the internet to facilitate online or offline sexual contact with the child (Molonay, 2018; Whittle, Hamilton-Giachritsis & Beech, 2015). OSG not only represents a type of child violence and abuse, but it also constitutes gender and legal inequality issues. According to a 2015 US study about OSG by the National Centre for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC), “the majority of reported child victims were girls (78%) while 14% were boys (for 9% of reports, gender could not be determined” (NCMEC, 2017, p. 1). In addition, as of 2017, only 63 out 196

2 countries had laws regarding OSG of children (NCMEC, 2017, p. 7), being Malaysia one of the 63 countries after passing the Sexual Offences Against Children Act 2017.

Since 2016, various public, private and advocacy organizations in Malaysia collaborated to criminalize and combat OSG driven mainly by the sense of urgency generated after the case of Richard Huckle was brought to light. Richard Huckle, described by British authorities as Britain’s worst pedophile, posed as a volunteer in local communities in Malaysia while sexually grooming and abusing hundreds of children (New Straits Times, 25 September 2017). He was convicted in the UK of 71 sexual offences against children, with his youngest victim being only 6 months old (New Straits Times, 25 September 2017). Simultaneously, an investigative journalism team in Malaysia uncovered and raised awareness about internet related crimes where local sexual predators were contacting mostly girls through online chats to later abuse them (R.AGE, 2017). As part of the efforts, state officials were held accountable, educational campaigns to change public opinions were conducted, and new policy was developed and passed.

In the case of Malaysia, it was found that the whole criminalization process appeared to have been achieved through a self-organized collaboration. The authors utilized the example of the criminalization process to examine these constructs in-depth and to further verify the applicability of implementing these types of collaborations to systematically tackle sustainability-related issues.

1.2 Previous Research

Although extensive research has been conducted regarding cross-sector collaborations and interorganizational networks, material regarding self-organization is more limited, especially when focusing on social change. Previous research on self-organized or self-governed interorganizational networks focuses primarily on understanding what differentiates them from formal partnerships and top-down approaches (Fosler, 2002). Other works study how non-profit organizations link with each other in informal ways to provide human and social services through engagement with public agencies (Berardo, 2009; Jang, Feiock & Saitgalina, 2016; Innes, Booher & Di Vittorio, 2010). The role of self-organizing international co-authorships in the science and technology fields has also been studied as a phenomenon where collaboration occurs in search for recognition and reward within networks of co-authors (Wagner & Leydesdorff, 2005). Lastly, self-organized networks have been studied as part of the formation and organization processes of social movements where individuals and organizations come together, mobilize resources, and conduct protests directed towards social change (Jenkins, 1983; Willems & Jegers, 2012).

1.3 Problem Statement and Aim of the Study

The authors identified the need to delve beyond the fundamental components of what makes successful cross-sector collaborations for social change occur by studying how those collaborations are formed and organized into interorganizational networks (De Montigny, Desjardins & Bouchard, 2017). Main interest in collaboration literature has been skewed towards collaborating processes and practices rather than governance structure and arrangements (Crosby & Bryson, 2010). Therefore, there is opportunity to study how actors in an interorganizational network can organize and interact with each other effectively in a self-organized manner to produce social change.

3 In order to achieve a deeper understanding of self-organized interorganizational networks with focus on the Malaysia case study, the authors ponder the following questions:

R1: How can an effective collaboration for social change be formed and organized? R2: How do the actors in the network for social change interact and relate to each other?

This research aims to identify the structural components and leadership relationships among members of self-organized multisector interorganizational networks needed to successfully address social problems and develop policy at a societal level. The case of the Malaysian criminalization of OSG will be presented as object of study in the hopes that it can also be used as a model for other Southeast Asian countries that still have not moved towards prevention and criminalization.

1.4 Layout

To address the research problem, the second chapter of this document will include a theoretical background discussing concepts to describe how cross-sector collaborations in the form of interorganizational networks are formed and organized. The chapter will also include a summary of Kotter’s Steps Model for organizational change to be used for analysis. A third chapter will provide the guidelines used for the research design of this study and the reason for choosing Malaysia’s criminalization process as a case study. The fourth chapter will discuss OSG in further detail as well as the Malaysian legislation process as the object of study to precede the analysis of the case study in chapter five. Finally, discussion and final conclusions will be provided, including implications for South East Asia.

4

2. Theoretical Background

Interorganizational networks form and become organized by leveraging participants in diverse sectors that have the legitimacy, knowledge, and resources to collectively achieve the desired outcomes (Stone et al., 2010). The following sections will first look at theories regarding governance structures, including the formation and organization of interorganizational networks with high focus on self-organization. Lastly, Kotter’s Stepwise Model for organizational change will be introduced to explain the general steps required to manage change effectively.

2.1 Interorganizational Network Governance Structures

Cross-sector collaborations occur under a collaborative governance regime that is built on “processes and structures of public policy decision making and management that engages people constructively across boundaries of public agencies, levels of government, and/or the public, private, and civic spheres in order to carry out a public purpose that could not otherwise be accomplished” (Emerson, Nabatchi & Balogh, 2012, p. 2).

Engaging individuals and organizations in different sectors to achieve change requires developing commitment through certain initial conditions that produce an environment where change agents come together in formal or informal manners, providing space for collaboration to emerge (Crosby & Bryson, 2010). Once the collaborative network is formed, it has to be organized by developing structural arrangements and establishing leadership hierarchies (Crosby & Bryson, 2010). The following sub-sections will expand on the formation and organization elements.

2.1.1 Formation of Interorganizational Networks for Cross-Sector Collaboration

Crosby and Bryson (2010) highlights that cross-sector collaborations are more likely to form in turbulent environments. Successful cross-sector collaborations encompass important concepts of system turbulence, along with identifying institutional and competitive forces that come into play (Bryson et al., 2015). This form of system turbulence is brought to light when it is understood that a societal or public problem cannot be diffused or solved through one sector alone, hence generating a collaborative window of opportunity (Bryson et al., 2015). In such emerging or changing conditions, interorganizational cross-sector collaborations create an opportunity for re-organizing of the current system. When looking at re-organizing the system, Crosby and Bryson (2010) notes that political, economic and social structures can either benefit or hinder the collaboration process.

Therefore, in light of leading successful interorganizational collaborations, integrative leaders ought to point out current institutional arrangements, identify which of these arrangements aid or hinder the collaboration process, and simultaneously recognize and seize the opportunity of changing conditions occurring inside or outside the institutions (Crosby & Bryson, 2010). In relation to that, identifying relevant stakeholders and analyzing the current political and social climate of which the condition is occurring in is also imperative in order to have a clear context of the public predicament (Crosby & Bryson, 2010). Bryson et al. (2006) also emphasize the importance of garnering information and resources from authoritative entities and field expertise whilst ensuring to arrive at solutions and outcomes that will amass sufficient support from stakeholders.

5 Crosby and Bryson (2010) proposes that a cross-sector collaboration is more likely to occur when the leader championing the cause or change acknowledges the need for separate efforts by multiple sectors in a joint action. In addition, Emerson et al. (2012) sheds light on stakeholders that are engaged in the process, indicating that the identity of the individual signifies who and what he or she represents - perhaps themselves, a client, a public or private agency, a non-governmental organization (NGO), or a community. This is important because bringing the right people in is what makes a successful cross-sector collaboration (Ansell and Gash, 2008). It is imperative because inclusion and diversity are not just normative principles that the collaboration should abide by, but that doing so elevates multiple perspectives and ideas which will result in a more thoughtful, inclusive, and broad solution of who will benefit or be harmed by the decision made (Sirianni, 2009).

Moreover, in collaborations, each partner has a distinct identity pertaining their separate organizational authority, while also assuming a collaborative identity linked to the collaborative interest (Thomson & Perry, 2006). Partners develop their collaborative identity through a shared purpose and vision that turns into commitment to achieve a supraorganizational goal (Thomson & Perry, 2006). In doing so, Crosby and Bryson (2005) discusses importance of arriving at an initial agreement of the goal whereby partners involved in the process come to a general agreement about altering an undesirable condition. Such collaborative settings require potential implementers to be recruited early on in the change process in order to ensure that they support and adopt the changed formulated collaboratively and within their respective authority (Crosby & Bryson, 2005).

Once the participants identify the need for collaborating, they can join forces in formal or self-organized manners. Formal developments of collaborative governance encompass careful advanced understanding and articulation of mission, goals, roles and action steps, while in self-organized developments this understanding emerges over-time as the network evolves (Bryson et al., 2015, p. 653). Formal collaborations can occur via memorandum or contract-based partnerships based on invitations or call for actions in contrast with self-organized ones which occur informally (Bryson et al., 2015). Feiock (2009) defines self-organized collaborations based on the nature of the relationships between the parties involved - whether it was forced or voluntary. Self-organized collaborations occur when the organizations coming together have shared desires in overcoming challenges requiring collaborative action. They are also defined by aligned expectations of how all parties involved enjoy mutual benefits, without a single party being coerced to another (Berardo, 2009). Having said that, these collaborations can also often come with some kinds of formalization (Jang et al., 2016).

2.1.2 Organization of Interorganizational Networks for Cross-Sector Collaboration

Different from single organizations where governance is located at the top leadership roles of the hierarchy and carried out through a diversity of set functions, collaborative and interorganizational networks have multiple players that are linked with each other to share information, resources, activities, and capabilities to achieve joint outcomes (Stone et al., 2010). The traditional approach where leaders guide followers that are employees in an organization with authority to evaluate, punish, reward, hire, and fire, does not work in the complex environments of networks due to “the various goals each member of the network has for the outcome of their combined effort”, raising the question of ‘who leads and who takes ownership of the processes and outcomes’ (Silvia, 2011, p. 67).

6 To establish order, interorganizational networks need structural arrangements where rules are established in the form of protocols or norms (Emerson et al., 2012). These rules allow for contest and conflict to co-exist within a larger framework of agreement (Thomson & Perry, 2006, p. 25). In informal engagements, these rules are observed in norms of reciprocity where partners demonstrate a willingness to collaborate if such willingness is also demonstrated by the other partners (Thomson & Perry, 2006). In more formal engagements, rules are developed as working agreements, including operating and decisions protocols, as well as charters, by-laws, and regulations, among others (Emerson et al., 2012). The larger, more complex, and long-lived the collaboration is, the more rules of engagement and arrangements are needed (Emerson et al., 2012).

In addition, structural arrangements also include the presence of clear roles and responsibilities. It has been observed that in interorganizational networks different partners “lead and manage by playing different roles (e.g. convener, advocate, technical assistant provider, facilitator, funder)” (Thomson & Perry, 2006, p. 26). Such roles are also based on the knowledge and resources owned by each partner as separate organizations. These arrangements and roles are not static, but rather can change over time as the collaborative needs also change (Thomson & Perry, 2006).

Similarly, to establish order and ownership of processes, interorganizational networks require a governance structure where hierarchy of relationships is recognized. In cases where there are agreements that bound contractually, therein lies an imbalance of distribution of power (Crosby & Bryson, 2005). This consequently results in leadership imposed vertically, defined by more authoritative forms of leadership (Jang et al., 2016). Whereas hierarchy of self-organized collaborations tends to be more horizontally guided by shared leadership in mainly informal arrangements where decision making processes are shared among all parties involved (Fosler, 2002). Thomson and Perry (2006) highlights that because partners in self-organized informal networks share a higher commitment towards resolving challenges requiring collaborative action, they are more willing to align their agendas towards a common objective, surrender autonomy and allocate resources equally.

Related to hierarchy, Provan and Kenis (2007) proposed three main types of collaborative network governance structures: participant-governed, lead organization-governed, and network administrative organization (NAO). Participant-governed does not count with a governance leader but rather is decentralized and governed in a shared manner by the network members themselves with no separate and unique governance entity (Provan & Kenis, 2007). Lead organization-governed networks are served centrally by a single network administrator or facilitator for all major network-level activities and key decisions (Provan & Kenis, 2007). In NAOs, the network uses a separate administrative entity that is not a network member but rather acts as a network broker to coordinate and sustain the network (Provan & Kenis, 2007).

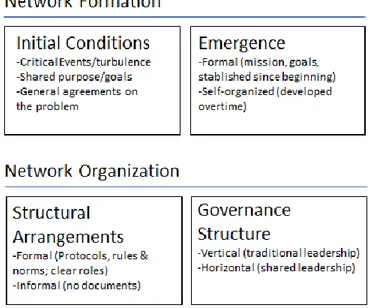

Figure 1 presents a theoretical conceptual framework integrating the interorganizational network concepts discussed before related to the network formation and organization.

7 Figure 1: Theoretical conceptual framework to study the formation and organization of interorganizational networks

2.2 Kotter’s 8 Steps for Change

Kotter’s Stepwise Model, first published in Harvard Business Review in 1995 has become an effective guide to manage organizational changes (Appelbaum, Habashy, Malo & Shafiq, 2012). Even though at the moment it did not include rigorous investigation since it was based on Kotter’s personal and business experience, subsequent studies have been conducted that found support for most of the model (Appelbaum et al., 2012). Also, some critics argue that no formal studies were found covering the holistic structure of the model (Appelbaum et al., 2012). The model was also published as a book in 1996 and later updated in 2012. Even though the model follows a sequence of steps, such sequence should be conceived as iterative and circular rather than linear (Pollack & Pollack, 2014).

The eight steps will be listed below, however, major emphasis will be given to steps seven and eight given their relevance to the analysis in this study.

1. Establishing a sense of urgency 2. Forming a powerful guiding coalition 3. Develop a vision and strategy

4. Communicating the vision

5. Empowering others to act on the vision 6. Planning for and creating short-term wins

7. Consolidating improvements and producing more change 8. Institutionalizing new approaches

As mentioned before, this study emphasizes on steps seven and eight. Step seven of Consolidating improvements and producing more change, highlights that a continuous improvement culture should be instilled in the organization where changes are evaluated, measured, learned from, planning for the next

8 changes to be implemented (Appelbaum et al., 2012). Those changes should include improving the systems, structures, and policies in alignment with the vision. Step eight of Institutionalizing new approaches refers to the importance of formalizing new change, turning them into new social norms and shared values (Appelbaum et al., 2012). To do so, is important to communicate how the changes and new attitudes have helped improve overall performance. In addition, according to the model, it is necessary to ensure that the next generations of management are able to maintain the changes by generating guidelines and standard procedures, along with training and mentoring

9

3. Research Design

This chapter provides information regarding the research methods used, the data collection and data analysis process, and the reliability and validity of the method design.

3.1 Qualitative Case Study as a Research Method

Qualitative analysis is a research method used to study real-world settings by exploring the context of a specific individual or group of people (Yin, 2015). Through studying the processes and meanings of people’s lives and understanding their views and perspectives, qualitative research aims at drawing out emerging concepts to make sense of human social behaviour (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015). In applying this research method, the researcher is a primary instrument for data collection and analysis, adopting an inductive approach to arrive at a richly descriptive data (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015).

A qualitative case study is an “in-depth description and analysis of a bounded system” (Merriam, 1998) used to understand the uniqueness and complexity that a phenomenon presents. It is considered a suitable method when researchers are interested in asking ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions of an issue or scenario (Volery & Hackl, 2011) as it enables researchers to understand complex social units comprising of multiple variables that gives importance to understanding a particular phenomenon (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015). Yin (2015) observes this qualitative method by further emphasizing it as a situation in which it is impossible to separate the phenomenon variables from its context. These discussions conclude one key characteristic of a case study - explaining it as a bounded system whereby the researcher aims to ask “what is to be studied” within an entity that is intrinsically bounded (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015).

In the interest of the objective of this thesis, the researchers aimed to make sense of a phenomenon where the context of the boundaries are not clearly defined or structured. The case study method was used to answer the research questions aimed at exploring the perceptions of individuals within an interorganizational network and dissecting the complex webs of collaborations that have occurred within this system. The researchers used a single-case study of events which occurred around a specific legislation that took place within a 2-year timeframe in a specific nation. This use of a single case study gave the researchers opportunity to provide a rich and deep exploration in order to detail the complexity of the phenomenon.

3.2 Data Collection

According to Yin (2015), interviews are guided conversations conducted between a researcher and participant, directed towards obtaining a specific kind of information. They are purposeful conversations to obtain information that cannot be drawn out through direct observation (Yin, 2015). There are commonly two types of interview methods, one being structured interviews while the other being semi-structured interviews (Yazan, 2015). In the case of a structured interview, the researcher presents predefined set list of questions without deviating from the selected questions through the interview process. A semi-structured interview, on the other hand, is slightly different in that only some questions are predefined and used as a guided frame for researchers during the interview, whilst making room for researchers to be flexible to deviate, explore or probe a specific area which may assist them in capturing new added information relevant to the topic (Yazan, 2015).

10 Semi-structured interviews were the primary interview method employed in this study, as the researchers drafted a predefined list of questions (see Appendix 1) that broadly answered the research questions. Since the researchers were keen to explore concepts of interorganizational networks, collaborative governance, self-organization and shared leadership, a structured interview method was deemed restricting to be able to capture the scope of responses gathered. Using a set of open-ended questions enabled the researchers to explore related themes while having the space to divert to other topics based on the responses emerged from participants.

Interview purpose: The purpose of the interviews was to gain further insights on the collaboration that took place in Malaysia before, during and after the new legislation of Sexual Offenses Against Children Act 2017. The researchers’ main focus was to explore the interorganizational networks that unfolded gradually towards societal change, by investigating perceptions of motivational incentives of individuals and organizations, shared goals between public and private sectors, collaboration strategies, types of leadership, forms of communication, structures and processes, and navigation of tension and conflict.

Interview process: Because of the difference in location between the researchers and participants, the interviews were conducted via video conferences throughout the months of April and May 2019. Verification and confirmation of interviewees were done via texts, phone calls and emails. Participants were first presented an informed consent form to sign and the signed and scanned copies were returned to the researchers prior to the interview session. All interviews were conducted in English language. Appendix 2 includes an extract of an interview as an example of the interview process.

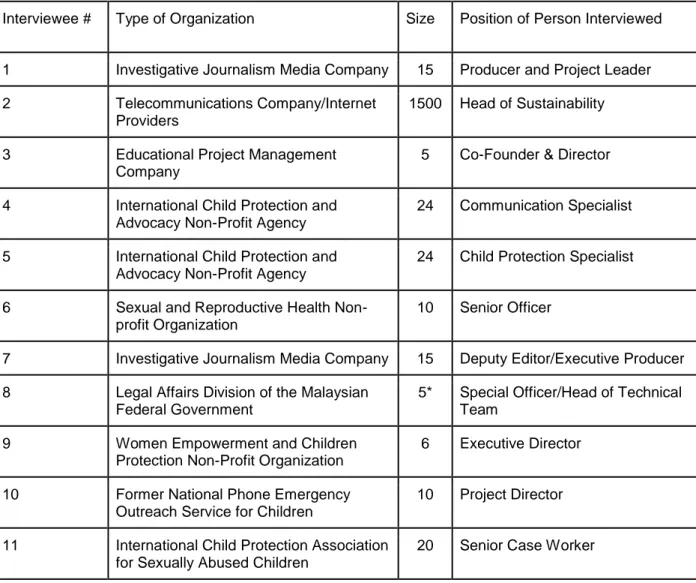

Sample selection and justification of interviewees: The sampling techniques mainly consisted of purposive sampling, also known as criterion sampling, where the sample population is chosen in a deliberate manner in order to arrive at the broadest range of information possible to the subject matter (Yin, 2015). The researchers identified specific individuals who were directly involved in a particular organization within the interorganizational network found in Malaysia. These participants were chosen because they met the criteria set for participant recruitment. These criteria included 1) having detailed information of the organization’s involvement, 2) understanding the processes of the collaboration that occurred, 3) actively participated in the collaborative process and 4) to a certain extent led either the organization or the collaboration. Snowball samplings were a secondary technique used, as suggested by Yin (2015), solely to be a complementary form of sampling to purposive sampling and should be conducted purposefully. The snowballing occurred when participants interviewed identified and introduced other key players in the interorganizational network system that the researchers were not aware of or informed about prior to the interview. The researchers then engaged these individuals and recruited them into the sampling population. The participants who were involved in the interview process are listed in Table 1.

11 Table 1: List of participants involved in the interview process per organization including size in numbers of employees

Interviewee # Type of Organization Size Position of Person Interviewed

1 Investigative Journalism Media Company 15 Producer and Project Leader

2 Telecommunications Company/Internet

Providers

1500 Head of Sustainability

3 Educational Project Management

Company

5 Co-Founder & Director

4 International Child Protection and

Advocacy Non-Profit Agency

24 Communication Specialist

5 International Child Protection and

Advocacy Non-Profit Agency

24 Child Protection Specialist

6 Sexual and Reproductive Health

Non-profit Organization

10 Senior Officer

7 Investigative Journalism Media Company 15 Deputy Editor/Executive Producer

8 Legal Affairs Division of the Malaysian

Federal Government

5* Special Officer/Head of Technical

Team

9 Women Empowerment and Children

Protection Non-Profit Organization

6 Executive Director

10 Former National Phone Emergency

Outreach Service for Children

10 Project Director

11 International Child Protection Association

for Sexually Abused Children

20 Senior Case Worker

*Size of the Technical Team of the Legal Affairs Division of the Malaysian Federal Government

3.3 Data Analysis

Data processing: All interviews were audio recorded and later transcribed verbatim. Documents of transcriptions are made available by authors upon request.

Data analysis: An overall comparative and inductive analysis strategy was employed. One of the most common initial techniques of analyzing qualitative data is by coding. Coding is a process in which information is deduced from the interviews to transition towards a more in-depth data analysis (Yazan, 2015). To begin with, the researchers adopted a bracketing and phenomenological reduction strategy, by suspending as much as possible the researchers’ natural attitude towards the world and instead focusing on analysing the unique experience of the interviewees (Gearing, 2004). Next, the process of delineating units of general meaning of the data was used to arrive at common themes. According to Hycner (1985), delineating units in qualitative research is the process of extracting the essence of the meaning expressed in a word, sentence or paragraph. This technique includes condensing what the interviewee has said without

12 altering the literal words of the participant as much as possible (Hycner, 1985). In doing so, this phenomenological strategy enabled the researcher to understand the lived experiences of the participants interviewed. Then, the researchers delineated the units of meaning to address the research questions. The goal of this step was to identify if the units derived from participants are related to the RQs. Given that the key concepts in the RQs are interorganizational networks, shared leadership and self-organization, the researchers delineated words, phrases or short sentences in relation to these concepts. Accordingly, the researchers then eliminated redundancies by referring back to all the units listed and removing those that are clearly redundant and irrelevant to previously listed units (Gearing, 2004). The next steps included clustering of units and determining themes. The researchers reviewed the list of units and begun clustering them into groups that have similar and relevant meanings. Once the groups were clustered together, the researchers then determined emergent and central themes that could express these clusters.

3.4 Reliability and Validity

The reliability of qualitative analysis refers to how consistent the results are, whether the application of differing methods used to induce themes would yield the same results (Yin, 2015). High reliability is achieved through prolonged scrutiny of data and codes/themes agreed upon by multiple researchers (inter-coder reliability). The reliability of this study is addressed through the inductive steps taken to draw out central themes and the presence of two authors through the data analysis process, in particular the delineating and clustering of units and determining themes.

Assessing the validity in qualitative research is aimed at testing the ‘accuracy’ of the findings of the researcher (Whittemore, Chase & Mandle, 2001). High validity of qualitative data analysis is achieved when there is evidence of rich and thick descriptions, ensuring that responses collected provide ‘abundant, interconnected details’ reaching theoretical saturation (Whittemore et al., 2001). Another evidence of high validity is communicative validity, whereby the researcher checks in with interviewees to clarify or verify a statement or phrase made. This was done during the data collection process, when the researchers asked probing questions to understand further or ensure that the responses made clearly reflected what participants meant.

13

4. Object of Study

Before providing the results of the thematic analysis, it is important to present the details of the case study of the criminalization of OSG in Malaysia.Hence, this chapter will first describe the process that predators generally follow to groom children. Then, the importance and implications of criminalizing OSG will be explained, finalizing with a summary of the criminalization process conducted in Malaysia.

4.1 The Online Sexual Grooming Process

Given the widespread and 24 hours accessibility to cheap, high-speed internet and ownership of mobile smartphones, social media networks and other information and communication technologies have become a major platform for child sexual abuse through grooming mechanisms (Molonay, 2018; Choo, 2009). At any given moment, there are approximately 750,000 online sexual predators worldwide (ICMEC, 2017 as cited by Molonay, 2018). These predators gain the trust of children - ranging mainly from 8 to 17 years old, with a mean age of 15 (NCMEC, 2017) - through the use of empathy and emotions (Choo, 2009), while also using manipulative tactics such as flattery, threats, sexualization, and bribery to achieve sexual consent (Whittle et al., 2015).

Facebook is the primary medium used by offenders to contact children (Molonay, 2018), given its easiness to share pictures, text, and videos (UNODC, 2018). In addition to social networks, offenders take advantage of platforms where membership is based on personalized profiles, such as apartment hunting, job applications, and travelling abroad, among other types. In the case of sexual trafficking purposes, for which OSG has become the principal gateway (Molonay, 2018), the offenders also sequence the actions of victims through the use of encrypted messages and hosting of groups of users with similar interests, “creating dependency and subsequently entrapping the victims for exploitative situations” (UNODC, 2018, p. 38).

According to an OSG study conducted by the NCMEC in 2015 in the US, the goals of the reported offenders evaluated (n=3,592) were four: “to want sexually explicit images of children (60%); to meet and have sexual contact with children (32%); to engage in sexual conversation/role-play with children online (8%) and; to acquire some type of financial goal (2%)” (NCMEC, 2017, p. 4). The grooming process usually follows four main relationship stages: (1) initial contact; (2) grooming techniques where the trust-building and manipulation mainly occurs; (3) sexualization including either sexual contact, exchange of photos or videos, and continued abuse; and (4) assessment of relationship where status and future of the relationship is pondered by either victim and groomer (Whittle et al., 2015). Furthermore, in child sex trafficking cases, enslaving typically occurs after the initial sexual abuse is conducted (Molonay, 2018).

4.2 Criminalization as Mechanism for Prevention of Online Sexual Grooming

Protecting children translates into creating a better future for the next generations. Effective non-legislative measures include the understanding of offending patterns - common red flags include the words ‘young’, ‘sweet’, college’, and ‘new’ (Molonay, 2018) - as well as the removal of offenders from diverse websites, denial of access to offenders to financial payment systems by the financial services industry, and educational strategies such as awareness campaigns (Choo, 2009). However, producing legislation to combat OSG keeps being crucial to ensure the protection of children, especially girls, and to prevent grooming abuse (ICMEC, 2017).

14 Because the Internet provides accessibility and anonymity in fulfilling sexually motivated behaviour, the modus operandi of an online sexual groomer is becoming more versatile, complex and difficult to detect. For starters, sexual offenders are finding it easier today to create a sense of false intimacy and relationship with their preys, due to the increasing online activity and decreasing social interaction in real-world settings among children and adolescents (Elliot & Ashfield, 2011). Adding on, sexual exploitation through online grooming can occur even without an offender physically being in the same proximity with the child (Kloess, Beech & Harkins, 2014). Apart from that, Quayle and Taylor (2001) also notes the rapidly emerging online communities formed by like-minded offenders with mutual interests to exploit children. These supportive environments such as encoded websites and exclusive community groups further foster and reinforce the behaviours, attitudes and norms of sexual offenders - driving them to escalate in offending behaviours because of how discreet and hidden communication technologies have become (Quayle & Taylor, 2001). Therefore, successful criminalization of OSG relies heavily on swift and comprehensive enactment of laws that take into account the aforementioned technological advancements and internet-related crimes (Stakstrud, 2013). Amendment and adaptation of current legislation is also vital to encompass the wide range of issues and crimes associated to internet use and abuse (Stakstrud, 2013).

International laws for OSG from 2003 to 2007 criminalized predators who were found with intentions to procure or “groom” any individual below the age of 16 (Urbas, 2010; Davidson & Gottschalk, 2011) - these laws include but are not limited to countries such as Australia, Singapore, New Zealand and the UK (Stakstrud, 2013). By 2007, Norway presented further provisions for amendment to the UK 2003 Sexual Offences Act, proposing that grooming laws should also include making it illegal for an adult to befriend someone underage through electronic means of communication, with intention to commit physical abuse on said child (Davidson & Gottschalk, 2011). This is because, before seeking to meet the child, many sexual offenders obtain sexual gratification through online means by “showing sexualized images to the child, engaging in sexualized conversations with the child, or asking the child to send sexually explicit photographs or videos to the offender” (ICMEC, 2017, p. 13).

Out of the 63 countries with OSG laws, Malaysia is one of only four countries in the South East Asian region with legislation in place to criminalize OSG—other countries include Brunei, Philippines, and Singapore (ICMEC, 2017). However, from that region, only Malaysia and Philippines have comprehensive laws that not only include the definition of OSG, but also make provision to criminalize the online grooming regardless of having proof of intent from the offender to meet the child (ICMEC, 2017).

4.3 Criminalization of Online Sexual Grooming in Malaysia as a Case Study

The criminalization of OSG in Malaysia was used as a suitable case study to understand self-governed interorganizational networks since it consisted of more than 10 organizations from both public and private sectors working at different levels and for varying timeframes to contribute towards the forming of new legislation. Deriving from the researchers’ present knowledge on the matter at hand, The Sexual Offences Against Children Act 2017 was established through multiple entities with different functions working together, comprising of educational and policy reform on holistic reproductive health, data collection of sexual behaviour and activity of Malaysian youths, investigative work on sexual predators, provision of up-to-date resources, and drafting of new laws on child safety and protection.

15 At the wake of December 2015, a budding Malaysian investigative journalism team developed a docuseries going undercover to pose as underage girls to chat with sexual predators online after it was brought to their attention of an exponential increase in internet-related crimes, specifically concerning underage rape cases (R.AGE, 2019). On the 6th of June 2016, serial pedophile Richard Huckle received 22 life sentences in the UK for grooming and sexually abusing 200 babies and children in Malaysia while he posed as a social worker for more than 20 years in the region (The Star Online, 2016). These charges created a momentum among women rights and child protection organizations, the local police force, media channels, private sector corporations and even celebrities to take action and voice out about child sexual crimes occurring in Malaysia. Within the next two years, both public and private sectors continued to rally for awareness and the criminalization on child sexual offences resulting in a new task force set up by the Prime Minister’s Office in Malaysia consisting of the Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development, the Attorney-General’s Chambers, UNICEF Malaysia, The Bar Council and other relevant NGOs (The Star Online, 2016).

In the following months, recommendations for new laws were drafted in criminalizing child sexual crimes while a campaign called #MPAgainstPredators was launched, leading to 115 Members of Parliament pledging their support to pass the new bill being tabled in Parliament (R.AGE, 2017). Shortly after, these collaborative efforts led to the unanimous agreement in Parliament for the Sexual Offences Against Children Bill 2017 to be passed effective immediately (Predator in My Phone, 2017). The follow-up events included the first sexual predator identified through the investigative documentary series brought to trial within the same month the bill was passed, which then led to the launching of the first Special Criminal Court in Malaysia to handle cases of child sexual offenses, the first of its kind in South East Asia (The Star Online, 2017).

In the case of Malaysia, it is crucial to note that cross-sector collaborations were key in facilitating the change process—running educational campaigns for relevant stakeholders, drafting out recommendations for new OSG laws in collaboration with advocacy groups for women and children rights, lobbying for Members of Parliament to take action within their regions, and making a police report on the first online sexual groomer uncovered through investigative documentary—in time for the newly tabled Sexual Offences Against Children Act 2017 to take its full effect.

16

5. Analysis

After conducting all interviews, several common themes were identified. The analysis of these themes will be presented following the theoretical conceptual framework shown before in Figure 1, based on network formation and organization. Finally, additional common themes were identified related to the iterative process of producing legislation and the process needed to operationalize new laws, to be presented separately.

5.1 Network Formation

Three common themes were identified related to the network formation process, including topics related to the initial conditions that formed the collaboration, as well as how the relationships in the collaborative network emerged.

5.1.1 Initial Conditions

5.1.1.1 Turbulence/Urgency generated by a Critical Event

The main common agreement among all interviewees was that, even though advocates of women’s rights and child protection had been pushing for comprehensive laws for years, it was the Richard Huckle case that moved multiple players for action.

“I think because of Huckle case. This all started because of Huckle case. Yeah. Although these campaigns that have been happening for so long, for many years, as I remember, but there was no, there's no push for us to go forward.” (Senior Officer, personal communication, May 18, 2019). This critical event generated public awareness and provoked the public will necessary to claim for new laws, advocating for better child protections. With the increased awareness, the public was also more receptive to the documentaries and campaigns released by the journalism company regarding local predators. That media campaign made people realize that the problem were not only foreigners that went to Malaysia to abuse children, but that the problem was also ‘in-house’, with local citizens who also contacted children to sexually abuse them.

“So, the Richard Huckle case comes in first in 2016 and because of Richard Huckle, I mean that's why there is a new law come in. Um, that's why the campaign, that's why the most [sic]of the Malaysian are aware of child sexual abuse. The awareness of child sexual abuse have [sic] raised up because of Richard Huckle.” (Senior Case Worker, personal communication, May 16, 2019). Apart from that, the case also heightened political will from the Prime Minister, cabinet ministers, and members of parliament. Therefore, the critical event of the Huckle case turned into a collaborative window of opportunity that provoked the call for action from the Prime Minister to create a task force led by the Minister of Legal Affairs Division and composed of multiple organizations, including leaders of various public agencies, NGOs focused on both women’s rights and child protection topics, and private organizations such as the journalism company. In addition, a major conference was conducted by the Prime

17 Minister’s wife and town halls were carried out throughout eight Malaysian states, to educate children and teachers about online sexual grooming and digital safety.

“I think it started with, with the, the call, the call to action was from the prime minister “sic”. Actually, uh, a lot of the leadership with the conference and so on was done by the Prime Minister's wife. [...] Yeah. So, I mean leadership. That is leadership. Yeah. So, I think it’s fantastic that they, they used the power and influence they had and of course [Minister of Legal Affairs Division] as well “sic”. I mean, never take it away from her that she really was very, very... Her office worked very hard on this.” (Communication Specialist, personal communication, May 3, 2019).

The fact that a critical event shook the social and political conditions in Malaysia is aligned with the proposed theory that states that cross-sector collaborations develop through initial conditions composed of turbulence in systems or environments (Crosby & Bryson, 2010). These conditions provide opportunities for change requiring leaders that can identify and bring in the right people from different sectors to collaborate and share their legitimacy, resources, and knowledge (Emerson et al., 2012), with the aim of re-organizing the political, economic, and social structures (Crosby & Bryson, 2010). Nevertheless, participants interviewed perceive that the tabling of the new legislation would still have taken place even without the occurrence of the Richard Huckle case. However, they concur that it would have taken a much longer time.

5.1.1.2 Shared Purpose

Another theme that emerged from the interviews was a sense of shared purpose amongst the various public and private sector organizations working together. Because there was a common agreement among the stakeholders on the dire need to protect children in Malaysia better, representatives were able to work on the matter at hand to achieve a consensual outcome albeit having different organizational agendas.

“Children. That's the key. Because I think when we talk about it... like we went, I think The Star (R.AGE) went to all the MPs, the, the Members of Parliament and a main emphasis was children “sic”. Everyone has children. Everyone wants the world to be better for their children. So that was the key ingredient that made everyone sign the law and everyone understood the importance of it.” (Executive Director, personal communication, May 3, 2019).

Because of the political climate at that time due to the 14th General Election approaching near, there were sentiments of political unrest emerging (Chevroulet, 13 April 2018). It was difficult for politicians of opposing parties to find a common topic that everyone could agree on. However, because the issue that was raised was concerning a common area that all parties could relate to, it garnered immediate and undivided support on the matter.

“So, at that time, when there was a lot of political turmoil, and a lot of politicians wanted to look for a topic that is generic, that is supported by all - all groups of society. Regardless of which political, political group you focus on, it was something that both political groups could come together and support.” (Head of Sustainability, personal communication, April 29, 2019).

18 In relation to that, right from the start of the formation of the special task force by the Malaysian federal government, the acting Minister appointed by the Prime Minister’s office ensured that the task force was a representation of as many relevant stakeholders as possible advocating for child protection and safety in Malaysia.

“We want to make sure that they deliver the results that we want. So, we, even when the first meeting that we call upon, there was a consensus among all the members that we needed a specific law to address sexual offenses against children. [....] So, we bring them, we build them together. They are the cross-sector people from government or from the NGOs and all of it, and listen all [sic], there was an opportunity to uh, to, to uh, to listen all the, all the suggestions made by them.” (Special Officer, personal communication, May 4, 2019).

In effectively navigating policy change through problem formulation, the initial agreements set out by change advocates ought to undergo expansion as they prepare to recruit new stakeholders and expand the coalition for change (Crosby & Bryson, 2005). Margerum (2002) further elaborates that it is imperative for these forms of collaborations to gain general agreement from all or most of the involved/affected stakeholders in order to form a winning coalition.

5.1.2 Methods of Emergence

An intriguing aspect of the complex web of the interorganizational network that unravelled was that many of these relationships emerged seemingly without formal structures in place. Words interchangeably used to describe nature of the networks the interviewees were involved in consist of “organic”, “voluntary” and “informal”, demonstrating the self-organized nature of this network. Yet, not all of the relationships in the network were informal, which is also a characteristic of self-organized interorganizational networks (Jang et al., 2016).

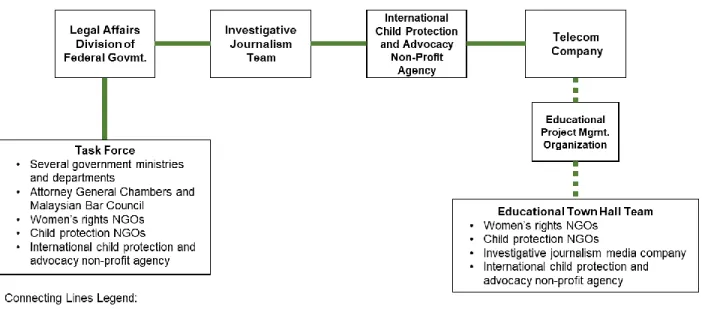

Figure 2 shows the overall structure of the interorganizational network that formed in Malaysia to aid in achieving the criminalization of OSG. The lines in the figure are coded based on the type of relationship that emerged.

The organizations on the top of Figure 2 established informal partnerships. For example, the relationship between the Legal Affairs Division and the investigative journalism media team emerged based on the important role that the journalism team assumed by exposing interactions of local predators with young girls on a national media campaign. The journalism team then supported the Legal Affairs Division in contacting the members of parliament to make sure they agreed to pass the law act created by the Task Force. However, the goals of this relationship were developed overtime, without the use of contracts or memorandums.

In a similar fashion, the relationship between the Legal Affairs Division and the participants of the Task Force (left side of Figure 2) was voluntary and informal; nonetheless, the Task Force was formed due to an official call to action from the Prime Minister and the participants were formally invited to participate in the recurring meetings where clear mission and goals were established since the beginning (Bryson et al., 2015).

19 Figure 2: Type of emergence of the different relationships in the interorganizational network in charge of the

criminalization of OSG in Malaysia

“No, it was a purely voluntary, you see, cannot force anyone to be part of these task force. So, this task force was directly [sic], the secretariat was the minister's office. So, we personally took charge of this task force to ensure that they move it in a less bureaucratic manner. (Special Officer, personal communication, May 4, 2019).

On the right side of Figure 2 are the organizations involved in the development of town halls, carried out to educate students, teachers and parents on the implications of OSG and the importance of digital safety. It all started organically between the international child protection and advocacy non-profit agency and the telecom company. Even though these organizations have a global partnership, the relationship in Malaysia came to be due to the work both organizations were doing years before on the field, deciding then to collaborate.

“[The international child protection and advocacy non-profit agency] and [the telecom company] have a global partnership. Okay. But the relationship that we started cultivating with [the telecom company] had very little to do with that global partnership. [...] It started off organically of course.” (Communication Specialist, personal communication, May 3, 2019).

The international child protection and advocacy non-profit agency had also been working informally on the media campaign about the local predators. These players came together and developed the concept of the town halls and identified participants to play as host and panelists as part of the educational town hall team. This team was coordinated by an educational project management organization contracted by the telecom company. But the participants of the educational town hall team partnered through a memorandum of understanding (MOU).

20 “Yes. For [the educational town halls campaign], we signed a MOU. Uh, uh, I think like a contract of agreement, a letter of agreement, uh, all four organisations signed it.” (Executive Director, personal communication, May 3, 2019).

Therefore, even though, in general, the interorganizational network was developed through self-organized and informal methods, parts of the network developed contractual partnerships or formally articulated mission and goals.

5.2 Network Organization

Three other common themes were identified related to the network organization process including topics already signaled in the conceptual framework, such as structural arrangements and governance structure. 5.2.1 Structural Arrangements

Structural arrangements in the interorganizational network were identified by the way the relationship between members of the network were formalized or kept informal, in addition to how the roles were carried out among members of the network. Therefore, this section will be divided into Relational Arrangements and Roles.

5.2.1.1 Relational Arrangements

As discussed in the theoretical background section, structural arrangements include rules and norms on which the interactions among members of the network are based. Formal engagements require rules in the form of working agreements, including operating and decisions protocols, as well as charters, by-laws, and regulations, among others (Emerson et al., 2012). In the absence of protocols and working agreements, the relationships still work informally based on norms of reciprocity where partners demonstrate willingness to collaborate with each other (Thomson & Perry, 2006).

Figure 3 shows the same structure of the interorganizational network that formed in Malaysia to aid in achieving the criminalization of OSG, but this time the lines in the figure are coded based on the type of arrangements that were used to sustain the relationships among partners.

Communication among the partners on top showed no evidence of protocols or working arrangements. In fact, their communication was highly informal.

“Uh, we met quite often but a lot of communications was by phone call and Whatsapp. [...]So he would type on Whatsapp, uh, just tell me that, you know, uh, "Hey, uh, this is going to happen in parliament tomorrow". (Project Leader, personal communication, April 17, 2019).

Similarly, the collaboration among the Task Force participants was also kept informal, and no documents or working arrangements were developed.

21 Figure 3: Structural arrangements of the different relationships in the

interorganizational network in charge of the criminalization of OSG in Malaysia

“So, it's very like meetings that will, you know, it was called, it was very ad hoc basis for the meetings at that time “sic”. So, from the first informal meeting and then second, third, what, I can't remember how many meetings that we had.” (Child Protection Specialist, personal communication, May 6, 2019).

The only evidence of protocols was identified in the relationship among the educational town hall team, given that the questions and topics discussed in the events were mainly scripted. Similarly, the logistics of these type of events required the participants to know their schedules in advance.

“We made sure everyone knows the roles, uh, and uh, what our roles are in contribution for the program and everything.” (Executive Director, personal communication, May 3, 2019).

5.2.1.2 Roles

As mentioned before, establishing structural arrangements includes division of labor into diverse roles. Thomson and Perry (2006) noted that in successful cross-sector collaborations roles and expectations are clearly defined.

When asked what was a key element that supported the criminalization of OSG in such a short time—the criminalization of OSG in Malaysia has been the fastest one reported being achieved in less than six months from drafting to approval of the law—there was a consensus among interviewees that everyone knew their role and what was expected from them.

“I think everyone saw that they had a role to play. [...] And I think everyone, all the different actors saw that. Saw the role they had, and they started getting really invested in it. [...] So I think that

22 was, it almost seems that there was really serious commitment, uh, from different parties that, you know, yes, I have a role to play in and maybe I will play the role on the law part, and I would play a role in another.. [...] So everyone I think saw, and I think that's important, uh, with each actor in that response sees [sic] that they have a role. And that their role is a valuable role.” (Communication Specialist, personal communication, May 3, 2019).

Thomson and Perry (2006) observed that in interorganizational networks different partners lead and manage by playing different roles. Table 2 summarizes the roles they the key partners played in the whole network.

Table 2: Summary of roles played by key partners in the interorganizational network in charge of the criminalization of OSG in Malaysia

Key Organization Main Role

Legal Affairs Division of Federal Government

Lead the Task Force to draft and table the Sexual Offences Against Children Act 2017

Investigative Journalism Media Team

Create public awareness; provide knowledge for drafting of the law based on research; calling Members of Parliament to ensure support for passing the new law

International Child Protection and Advocacy Non-Profit Agency

Convene and facilitate information sharing among partners; provide funding for town halls

Telecom Company Provide funding for town halls; provide knowledge in digital safety

Educational Project Mgmt. Organization

Coordinate and facilitate town halls

Women’s rights and Child protection NGOs

Advocacy, provide knowledge for drafting of the law and town halls based on experience

Government Ministries and Departments

Provide knowledge for drafting of the law based on experience and needs of the people served by their offices

Attorney General Chambers and Malaysian Bar Council

Provide knowledge for drafting of the law based on experience and needs of the people served by their offices

Even though all members of the network played a key role for the successful criminalization of OSG, there was also a consensus among some interviewees that the investigative journalism media team played a lead role in pushing the collective action forward.

“The only person, I mean that [sic] do this I will still say is [the Investigative Journalism Media Team]. The campaign that they have done. Yeah. It's a success that they [were] able to push it and

23 prove it and show it to them [the Task Force] that this is the debate. They basically pull all the resources together.” (Senior Case Worker, personal communication, May 16, 2019).

A unique aspect of this interorganizational network is that the players came to work together mainly in an informal manner without the use of rules and norms, but each member knew what they could contribute and how to play their role effectively.

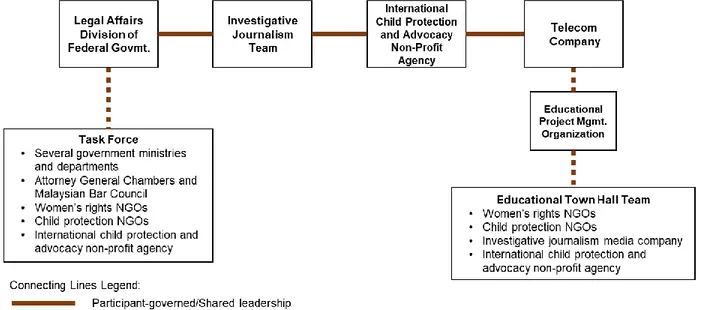

5.2.2 Governance Structure

Collaborative interorganizational networks are composed of governance structures that define how information is shared and how decisions are made based on leadership hierarchy. Hierarchy can be either vertical following a traditional and authoritative leadership approach or rather horizontal where leadership is shared and mainly informal (Jang et al., 2016).

Again, the interorganizational network discussed in this study did not show a single overall governance structure for the whole network. Rather, the network was composed of a combination of different governance structures, depending on the task at hand.

Figure 4 shows the same structure of the interorganizational network that formed in Malaysia to aid in achieving the criminalization of OSG, having this time the lines in the figure coded based on the type of governance structures used to organize the interactions among partners. The line coding used in the figure follows Provan and Kenis (2007) approach, defining participant-governed structures as those where there is no governance leader but where rather authority is shared among members of the network. As well, Provan and Kenis (2007) define lead organization-governed structures as those in which networks are served centrally by a one member of the network that functions as facilitator or leader of all major network-level activities and key decisions.

Figure 4: Governance structures of the different relationships in the interorganizational network in charge of the criminalization of OSG in Malaysia