1

The Importance of Building Trust in

Digital Co-Design

Tirsa Rosabla Ramos-Pedersen

Interaction Design One-year master 15 credits

Spring/2020

2 ABSTRACT

Social distancing due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has caused designers to rethink how they engage with users. This project involves a designer and users co-creating a digital workshop for ideating solutions through the use of information and communication technologies (ICT). The context of COVID-19 was used as a means to engage with users through digital co-design activities. However, the aim of the project was not to solve their problems of information sharing, but to understand what participants need from a facilitator in order to have more meaningful dialogues and contribute to the ideation process. The importance of trust and a sense of empowerment were identified as what participants need to better ideate and innovate. Trust and empowerment are valuable in any co-design situation, physical or digital. However, when interacting with participants through strictly digital means, it requires more time and energy to nurture trust between a designer and users. The knowledge gained through this digital design project resulted in not only a co-created digital prototype for remote co-design, but guidelines for how to develop trust with users when co-designing remotely.

3

Table of Contents

1. INTRODUCTION: RESEARCH QUESTION AND AIM ... 4

1.1 Introduction ... 4 1.2 Design opening ... 4 1.3 Research question ... 5 1.4 Project aim ... 5 2. BACKGROUND/THEORY ... 5 2.1 Co-design ... 5 2.2 Empowering users ... 6 2.3 Building trust ... 6

2.4 Cost and benefits of co-design ... 7

2.5 Canonical examples ... 8

3. METHOD ... 9

3.1 Project plan ... 10

3.2 Design before design ... 11

3.3 Exploratory Research ... 11 3.4 Co-design ... 14 4. DESIGN PROCESS ... 15 4.1 Define ... 15 4.2 Recruit ... 17 4.3 Plan ... 17 4.4 Conduct ... 19 4.5 Synthesize ... 26

5. MAIN RESULTS AND FINAL DESIGN ... 27

5.1 Main results ... 27

5.2 Final design ... 28

6. EVALUATION... 32

6.1 Review of final outcome ... 32

6.2 Evaluation of the design process ... 33

6.3 Evaluation of collaboration with stakeholders ... 34

7. DISCUSSION ... 34

7.1 Relevance to future co-design processes ... 34

7.2 Limitations and potential implications ... 34

7.3 Potential future work ... 35

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... 36

4 1. INTRODUCTION: RESEARCH QUESTION AND AIM

1.1 Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has impacted all aspects of society and daily life. It has interrupted processes and made people reconsider and reimagine how they do things. COVID-19 has impacted the design world by changing how designers interact with users. Instead of traditional “paper-based” co-design methods, designers can transition towards digital co-design. Designers meeting and engaging with different stakeholders in person has been a major part of traditional co-design methods (Shi et al., 2015, p.295). However, due to COVID-19, social distancing, and lockdowns, co-designing with users face-to-face is not currently a viable option. Furthermore, when COVID-19 issues are resolved, digital co-designing will continue to be relevant to how designers co-create in the future. Therefore, designers and/or facilitators need to reevaluate how they interact with users and move away from more physical to more digital methods. This can be achieved by conducting co-design activities remotely and reinforcing relationships between designer and user through digital means. The case study discussed in this paper revolves around expats in Sweden ideating in a digital co-design workshop about how to improve governmental

information sharing regarding COVID-19 to foreign residents. Though information sharing is the context of the workshops, the main focus of the designer will be to develop meaningful relationships with users (remotely) in order to optimize ideation. Being limited to only digital tools can make trust building difficult, but the value gained from nurturing trust between the designer and the user is unparalleled. It is this project’s claim that if a user is to take an active, meaningful role in the digital co-design process, they will need to trust the other stakeholders and feel confident about their abilities and the digital tools being used. Establishing trust between users, designers, and the digital platform will improve the ideation and innovation process. Digital co-design methods hold potential and need to be optimized (Shi et al., 2015, p.296). Especially in such unsettling times of a pandemic where some users can feel insecure or doubtful.

1.2 Design opening

1.2.1 Co-designing remotely with ICT

Current world crises have made it difficult, if not impossible for people to meet in person. Through the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) people across the world are able to connect asynchronously or in real time. ICT remove the dependence on face-to-face meetings such as physical co-design workshops and give people an alternative to maintaining relationships through digital means. There are currently many ICT on the market that facilitate collaboration within design. However, it seems that most digital co-design tools are aimed towards stakeholders from within the same organization.

Stakeholders who are already invested, have a tech culture or IT support in place, training available to them, or are somewhat knowledgeable with technology. Collaborative ICT work great for people who have technical understanding and help from their organization.

Unfortunately, these technologies are not aimed specifically to include non-designers, users, non-employees, etc. into the digital co-design process. These types of tools enable designers to work with different stakeholders all across the world and in different time zones. Yet these digital tools do not necessarily support developing relationships between a user and a

5 Designers need to be able to engage with users through digital co-design tools in a

meaningful way. They need to develop a relationship, empathize, and engage with their users even if only meeting remotely. Whereas users need to feel comfortable enough with the facilitator, other participants, and the digital tool to share their true feelings and ideas. If digital co-design participants are not part of the same organization, they might require extensive onboarding to familiarize them with the digital tools. The way this onboarding process is handled can either add to the relationship building process or hinder it (Von Hippel, 2005, p.162). There are a lot of unanswered questions when it comes to how to best develop relationships with users in a purely digital co-design environment.

1.3 Research question

Due to COVID-19 and social distancing, designers need to digitally interact with users in a meaningful way that furthers ideation. How could designers encourage trust and

empowerment through the use of existing online tools and digital co-design processes to help users design potential solutions that address their needs?

1.4 Project aim

This project aims to contribute to the design field by identifying what users find valuable for them to ideate and innovate successfully in a digital co-design space. Digital co-design is very relevant today, but also valuable for future design work as many organizations are digitizing their processes. Participants of this co-design project are limited to English-speaking,

international residents in Sweden who will ideate on a digital platform about how they would like to receive pandemic related information from the government. Government information sharing about COVID-19 to expat communities in Sweden is the context used to engage with users in a digital co-design process. However, the main focus of this project will be creating and developing trusting relationships with users through the use of ICT to facilitate

productive digital co-design. As trust is hypothesized as being a major contributor to the ideation and digital co-design process. For the purpose of this paper, digital co-design refers to a designer or facilitator engaging with users to co-create a digital workshop where users can ideate on a potential design solution. The information provided by participants will be reviewed and productive trust facilitating methods will be identified. The project will explore how users trusting a facilitator and trusting their own abilities on a digital platform will help them ideate better through strictly remote interactions. The information being reviewed will be collected through surveys, interviews, online communications, and digital co-design workshops. The end result will be a digital prototype for remote co-design, in addition to guidelines for how facilitators should co-design with users in a digital environment. 2. BACKGROUND/THEORY

2.1 Co-design

Co-design and/or participatory design (PD) takes place when designers invite users to partake in the ideation process because they value user experience and feel that users can contribute to the overall quality of the design (Kanstrup, 2012, p.111). Users are experts in their own experiences and have knowledge to contribute to making a product or service better. If provided with appropriate tools to generate new ideas or better express themselves, users can contribute to the ideation process and together with a designer, come up with better solutions (Sanders, 2002). “Co-design is also distinguished by a desire to empower and give voice to people who are traditionally left out of the design process” (Pedersen, 2016, p.172). Kanstrup further asserts that "it is central to PD to focus on supporting end users in

6 expressing themselves in and through design. [Moreover] it is important for PD to elaborate how to hear and understand end user voices” (Kanstrup, 2012, p.116). By understanding users’ voices and including them in the ideation process, better solutions can be co-created. 2.2 Empowering users

According to Briggs and Makice (2008) “increased information access, global view, ease of networking and increased activism has created non-employees who are becoming a part of the process of value creation with organizations” (p.250). Both employees and

non-employees can find value in co-creating artefacts that will either help or hinder them in accomplishing goals. Botero and Saad-Sulonen refer to these non-employees as “lead users” (2008, p.266). By including lead users in the process, they are made to feel part of the process and empowered that their voices are heard.

It is not only lead users who should be included in the design process though, Fischer and Scharff (2000) believe everyone should have a designer mindset (p.397). Technologies have the unique possibility of allowing people to make incremental changes and become designers themselves, i.e. open source programming communities. However, this ability to be a

designer should not be restricted to people with high technical skills, or “elite scribes” as Fischer and Scharff call them, but should be available to anyone who has a “designer

mindset,” who is interested, and desires to make a change (2000, p.403). To encourage users to become designers, “it requires a culture within which users feel in control and have a designer mindset” (Fischer & Scharff, 2000, p.401). Co-design and PD aide users in developing a designer mindset by empowering users to take an active role in the design process.

In a literature review of academic papers, Ertner et al. distinguish categories that influence empowerment within a PD process as well as determine that empowerment within PD “is not just a moral and politically correct design goal, but a challenged and complex activity”

(Ertner et al., 2010, p.191). Empowerment here is defined as giving power or authority as well as enabling stakeholders. PD aims to enable specific user groups to change their own life situation and ideate and innovate better futures for themselves. The designer can help users achieve this goal by providing tools and skills to the users. Enabling users and/or

“empowerment becomes a goal which is not unproblematic and depends upon the designer’s ability to create the right framework for participation” (Ertner et al., 2010, p.193). Designers also need to be empowered or equipped to communicate the value of user involvement and interact with users in a meaningful way that maintains user engagement throughout the design process. PD and co-design cannot be done without active stakeholders, it is the responsibility of the design practitioner to communicate effectively with stakeholders and keep them motivated in the process. Ertner et al. surmise that empowerment in design “is not merely associated with a positive result of user participation, but a complete and challenging activity” (2010, p.194).

2.3 Building trust

Relationship building, or trust, is key in traditional co-design. As Clarke et al. state, "trust can also be enabled through designing shared material resources tailored to or co-designed with specific groups. These activities enable contextually sensitive group understandings, empathy, and communication (2019, p.4). Materials play a role in developing trust in co-design. When designers engage in digital co-design by using ICT as their materials, more consideration needs to take place. When introducing IT artefacts into the digital

collaboration process, designers need to take care that the artefacts do not take away from the relationship building process.

7 One way to nurture relationships through co-design is with a tabletop option, which is a useful midway solution between digital and analog collaboration. Heinrich et al. (2014) argue that tabletop IT artefacts can help an advisor and client collaborate better by providing a shared space that allows them to work on the same task simultaneously. Having a shared space to collaborate gives users an active role in coming up with decisions and solutions. As well as providing transparency and openness, which provides the user with a sense of trust. But what if you cannot meet in person? What if all communication is done digitally? The same conclusions from Heinrich et al. (2014) still apply to purely digital tools; eye contact, openness, being able to see what everyone is doing, a horizontal working surface as opposed to a vertical display, and representing tools people are already accustomed to, e.g. a white board. All of these aspects are vital to incorporating digital tools into the digital co-design process. For instance, if a designer wanted to use an online white board collaborative tool remotely with a potential user. They could first have a video chat where they make eye contact, get to know each other, and write notes about the user. They should try to keep the conversation flowing as naturally as possible. Once the relationship is established, and the designer and user feel comfortable with each other, they can move on to the collaborative tool. Heinrich et al. (2014) state, “In this context, by relationship building we refer to the establishment of a trustful connection in which the client feels taken seriously, having his needs attended to and being treated respectfully. Overall, the client should feel comfortable to reveal information that is important for the solution or decision making process” (p.172). It is important for the client to be well informed and feel comfortable enough to have an open dialogue with their advisor, “because the lack of such a relationship will also hamper the cooperation and the exchange of knowledge and advice (e.g., if persons do not ask relevant questions or conceal important information)” (Heinrich et al., 2014, pp.181-182). It is important for the design process to ask the right questions and that people answer

truthfully when asked what they think or feel. In order for participants to answer in a meaningful way that contributes to innovation, a sense of trust needs to be

established. “Trust-building is, therefore, a vital initial step in designing with organisations and a prerequisite for enabling longer-term impact (Yee & White as cited in Clarke et al. 2019, p.2).

2.4 Cost and benefits of co-design

Trust within co-design allows designers to gain an abundance of knowledge and insights into their users' needs as well as positive responses from the users afterwards. However, there is a cost when it comes to involving users into the co-design process. Kujala (2003) states there is a substantial amount of raw data that is collected and needs to be analyzed which is time consuming. Sometimes it is difficult to get access to users and negotiate times that work for all stakeholders involved. Once the users are engaged, they want to impact the design, make changes, and that can slow the development process. A great deal of time and energy goes into co-designing with users (Kujala, 2003, p.5). However, as Gould et al. (as cited by Kujala 2003) states; “Extra effort in the early stages leads to much less effort later on and a good system at the end” (p.4). Organizations and designers need to conduct a cost-benefits analysis to determine how much involvement is needed in their projects. There are always benefits to involving users in the design process, they need to make sure the incurring costs such as time and money spent are worth the end results. Users might ask for more changes through the process, but their level of satisfaction will be higher than if they were not involved in the process at all (Kujala, 2003, p.5).

Steen & Kuijt-Evers (2007) acknowledge the benefits of including users in the innovation process. Yet point out the potential drawbacks of including users. For example, Van Kleef et

8 al. (as cited in Steen & Kuijt-Evers, 2007) warn against relying on end user's opinions. They may not be aware of their needs, let alone articulate them. They might also be hesitant to open up to the interviewer about their needs (p.3). That is why trust building in co-design situations is crucial. Designers need to develop an open dialogue with users where the designer can help the user identify their problems and the user can be honest about their needs. Taking the potential drawbacks of co-designing into consideration, including users into the design and innovation process is still relevant. Users are already playing an active role in the innovation process (Steen & Kuijt-Evers, 2007, p.3). For example, when they use a product or service in an alternative way than designers originally intended. Designers need to take advantage of users’ interests and ingenuity and include them in the innovation process.

2.5 Canonical examples

2.5.1 Case study: Researching distributed populations

MacLeod et al. (2016) introduced the asynchronous remote communities or the ARC method in which they recruit and interact with users through the use of private Facebook groups (specifically Facebook groups for people with rare diseases) and other ICT. Recruiting was fairly easy as a researcher was already a member of the groups and already had established rapport with the community members. Some of the users had participated in previous studies which resulted in them trusting the researcher and vouching for them when others in the group questioned their motives. The researchers noted the difficulties of analyzing the abundance of data they collected i.e. private and public messages, metadata, voicemail, etc. As well as touched on the limitations of using Facebook, such as participants not being notified of new activities or not engaging with each other. As many of the activities were done on their own, users would post their finding and did not get feedback from other participants. MacLeod et al. recommend encouraging participants to engage with each other and comment on each other’s contributions to nurture a sense of community and trust (2016, p.4). Some participants were confused or needed more instructions for the activities, consequently the researchers provided abstract examples to empower users and give

guidance but not nudge them (MacLeod et al., 2016, p.5). MacLeod et al. suggest careful consideration when developing activities for digital co-design, especially with sensitive topics (2016, p5). For example, the participants were homebound due to a rare illness, some

activities drew users’ attention to the negative aspects of their lives which fostered

uncomfortable feelings. When remotely interacting, it could be ethically detrimental to put vulnerable users in emotionally harmful situations. Nevertheless, participants expressed an overall level of satisfaction in the process. This project was successful in getting users

involved in the ideation process. “This is a first step in understanding how group-based research can be conducted using a common social platform like Facebook” (MacLeod et al., 2016, p.7).

2.5.2 Case study: Remote research with people living with HIV

Another example of using Facebook to engage with a vulnerable, distributed population is that of Maestre et al. They recruited participants living with HIV in their study, which is usually difficult due to the stigmatized nature of HIV. HCI research with people in the HIV community has heavily relied on traditional face-to-face methods. “Although data collection has also been done with online surveys, HCI-based research methods like photo elicitation, user testing, and co-design have not commonly been adapted to online settings” (Maestre et al., 2020, p.2). Maestre et al. describe their study where they implemented the ARC method

9 (or digital co-design) to collect data and engage with users remotely in an online group. “The ARC method has been used with populations facing in-person study constraints” (Maestre et al., 2020, p.2). They recruited participants through posting in closed Facebook groups specifically aimed at people living with HIV. They conducted two separate studies in which they compared face-to-face meetings with digital co-design. The researchers stated that the digital method proved to be more effective at generating discussions and was faster. Whereas the physical method was much slower and required more explanation about the activities. The researchers familiarized themselves with the language used by this demographic in order to avoid offending users and relating to them better. Using this shared language and understanding each other, develops a sense of trust and empowerment that users’ individual needs will be taken into consideration by the designers. To further develop a sense of trust, they set up notification to display their accessibility and used their personal Facebook accounts for more transparency. It was found that users in both studies generated more comments when they used artefacts that allowed users to contribute their thoughts,

observations, and ideas. Maestre et al. suggest that researchers continue to integrate the use of the ARC method when face-to-face interactions are not an option. “Moving forward, we hope to design more engaging activities that could […] help researchers create rapport and elicit deeper and more insightful discussions among participants (Maestre et al., 2020, p.8).

2.5.3 Case study: Digital co-design with pregnant and new mothers

Prabhakar et al. investigated the suitability of the ARC method (or digital co-design) being used in place of face-to-face focus groups to interact with pregnant and new mothers. They recruited participants through physical and digital platforms and engaged with pregnant women and new mothers through activities and discussions on Facebook and other ICT. They separated the group into different subgroups (new pregnancy, experienced pregnancy, and moms) in order to have homogeneous groups. Homogeneous groups create a sense of community and trust, allowing participants to feel comfortable with other group members and open up more about their true feelings. The researchers adapted the original ARC method to conduct multiple activities, allow time for reflection, and also provide users with limited mobility an opportunity to take part in the sessions (Prabhakar et al., 2017, p.4924). The activities ranged between private to public responses, allowing participants to express both personal insights into their lives and experiences as well as share their knowledge with the other group members. Providing the opportunity to share knowledge can empower users, by feeling as if they have valuable contributions that could help others in their community. One drawback mentioned was “the lack of opportunity for researchers to gauge the facial expressions and display of emotions by participants during the study” (Prabhakar et al., 2017, p. 4933). Heinrich et al. noted that eye contact plays a major role in interpersonal relationships by allowing users to connect, engage, and trust the other group members (2014, pp.172-173). This issue points to digital presence, relationship building, and trust being needed to better collaborate in the digital co-design process.

3. METHOD

The main method implemented in this project is digital co-design. Steen & Kuijt-Evers (2007) state:

If a goal of the project is to imagine or envision a future practice or product, or to seek inspiration together with end-users, then methods like co-designing or empathic design are appropriate; (p.18)

The aim of this research project is to work alongside users in a digital co-design setting, to identify what users need from a facilitator to ideate and innovate successfully together

10 through the use of ICT. Each subsequent method was implemented to digitally co-design with users around the topic of information sharing. Participants and the designer co-created and conducted a digital co-design workshop with the aim to produce suggestions for

successful communication between the Swedish government and expats. Developing trust between the facilitator and the participants was the main focus of the digital co-design process. Thus, identifying guidelines for developing trust and conducting productive remote co-design with users through the use of digital tools.

3.1 Project plan

3.1.1 Project overview

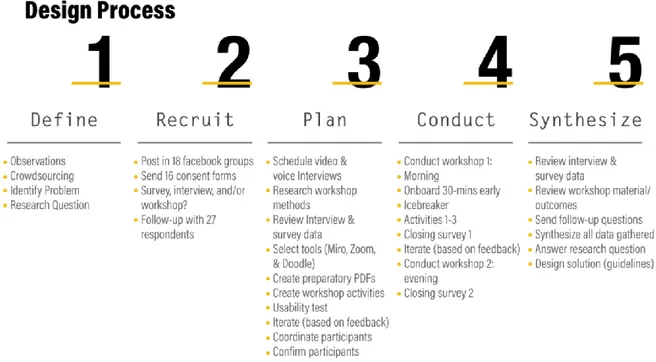

Figure 1. Design Process. Adapted from Mozilla’s Participatory Design/Co-design Worksession steps (Mozilla, n.d.).

The plan for this project was to test the theory of trust being important to digital ideation and innovation. That was done through conducting a digital co-design process (see Figure 1) with expats in Sweden, within the context of governmental information sharing about COVID-19. The process started by reaching out to different international communities in Sweden to recruit participants. This was done through English-speaking expat Facebook groups and crowdsourcing in the expat community. After people responded to the call to action, consent forms created on SUNET (a secure database provided by Malmö University) were sent out (see Appendix A). Participants were required to sign the consent form before continuing in the design process. Users were given the option of filling out a SUNET survey on their own or taking part in either a video or audio interview. The initial survey asked questions about participants’ online collaboration history, what they need from a facilitator to express themselves, how they are getting information about COVID-19, and how the pandemic has impacted them so far. Finding participants and collecting all the

documentation before the actual co-design work started was time consuming. Consequently, recruiting was done alongside researching methods and tools. After researching what was available in terms of services and tools, co-design workshop methods were also reviewed.

11 The co-design workshop was created on Miro (an online collaborative whiteboard) based on feedback from the initial survey and interviews as well as researching methods. Multiple usability tests were performed by users before conducting the real-time, digital co-design workshops about expats and information sharing. A few days after the workshops,

participants were asked to answer a follow-up or closing survey about the workshops and about their relationship and trust level with the facilitator. Data from the surveys, interviews, and workshops were collected and reviewed. The data being knowledge gained about the context (COVID-19 information sharing), as well as what worked and did not work in the digital workshop to facilitate trust and ideation (methods). An analysis of the results led to the design solution: guidelines for digital co-design that improve ideation through the facilitation of trust between the organizer and users.

3.1.2 ICT used

There are many ICT available for digital co-designing, but there is not one that completely stands on its own. Some provide different features that are better for certain tasks. As a result, multiple ICT were used to digitally co-design with users during this project. Doodle was used for scheduling which resulted in two workshops, one in the morning and one in the evening. Miro and Zoom were used to facilitate the digital co-design workshops. Miro

provided a shared space for collaboration, where participants can add and see each other’s contributions. Zoom’s audio and video conferencing allowed participants to see each other and provide a sense of familiarity instead of being limited to text comments or only seeing names on a screen. Miro does have a video conferencing feature, but that is only available through a paid subscription. Social media, messaging apps, and email were used to communicate with participants throughout the process. The awareness that participants were being asked to engage in a project that would not realize their design solutions or resolve their issues with information sharing was at the forefront of each interaction.

Therefore, the process of engaging with the facilitator through multiple ICT was supposed to be as easy as possible for users. Which is why each correspondence was made on their preferred platform.

3.2 Design before design

Before any co-design or PD process can be executed, there must be what Pedersen refers to as “design before design”. “By design before design, I mean those preparatory activities where the ‘actual’ design activities are designed” (Pedersen, 2016, p.173). When including users in the design process, there is a lot of work to be done before any of the design work begins. A designer needs to follow up, organize, and coordinate many people’s interest and schedules. Keeping participants engaged throughout the process is not always possible due to scheduling or even a lack of interest. The amount of work involved in managing

information, following up, and coordinating participants is a major part of any co-design process. Relationships need to be nurtured throughout the whole process to keep as many participants as possible engaged.

3.3 Exploratory Research

Martin and Hanington (2012) suggest using a variety of methods to provide designers with a solid base of the design territory. They refer to this use of research methods as exploratory research (p.84). Designers can create better products or services if they understand the design possibilities, existing artefacts, and empathize with future users through these exploratory research methods (Martin & Hanington, 2012, p.84). Alongside the recruiting

12 process, exploratory research was conducted to better understand the design territory and empathize with users. Many methods were used such as; crowdsourcing, surveys, interviews, observations, literature review, and concept mapping. By conducting a wide range of

exploratory research, the designer was able to empathize and gain a better understanding of the users, their problem, and work on developing trust between both parties.

3.3.1 Crowdsourcing

The designer observed a difference between how Swedes respond to government provided COVID-19 information compared to that of expats on Facebook. Expats seemed to be more anxious or critical of Sweden’s decisions, whereas Swedes seemed to be more trusting of their government. This observation opened up a potential design opportunity worth

exploring. Therefore, people in both communities were crowdsourced to see if the theory of expats distrusting the Swedish government’s decisions was accurate. Crowdsourcing is when a large group of people voluntarily respond to a call for action to perform a microtask that is accessed through a common platform and can be done fairly quickly and easily (Martin & Hanington, 2012, p.52). Understanding expats frustrations and current pain points within the context of information sharing allowed the designer to empathize and engage with users better during the co-design process.

3.3.2 Surveys

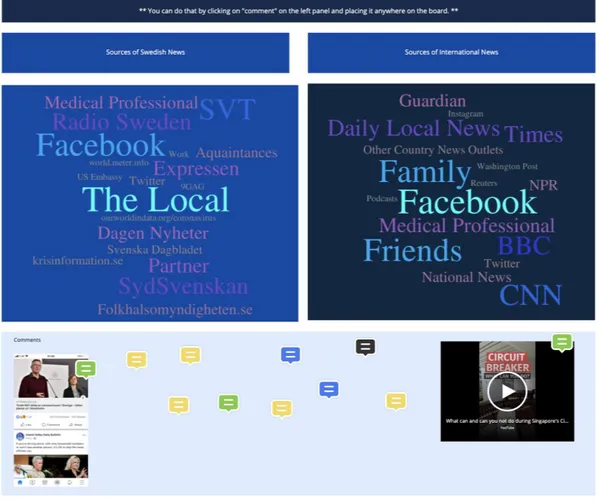

The initial survey, (see Appendix B) gave participants the opportunity to self-report their thoughts and opinions on their own time without depending on the schedules of others (Martin & Hanington, 2012, p.172). The survey had varying types of questions that generated responses about contributors to ideation, co-design, and COVID-19. Participants’ responses provided insights into the design territory they would be digitally co-designing in. The knowledge gleaned from the survey helped to construct the activities in the workshop. For instance, using their survey responses to create a word cloud of news sources. The many emotions revealed in the survey led to the creation of a pictorial Likert scale for users to share their feelings with others. In addition, the information gathered from the survey was used as examples or inspiration in the workshop activities. The surveys also helped the designer better communicate and build trust with users later in the process by learning more about them on a personal level. Unlike with the interviews, which provided a dialogue and instant relationship building. The surveys were one-sided, the participants’ views were expressed, but insights were limited to the questions asked in the survey.

3.3.3 Interviews

Some participants preferred the more personal option of interviewing over taking a survey on

their own. This provided specific answers to questions and gave the designer additional

information about the users themselves and their lives. “Interviews may be structured and

follow a script of questions, or relatively unstructured, allowing for flexible detours in a conversational format” (Martin & Hanington, 2012, p.102). The interviews were structured,meaning preselected questions were asked that corresponded with those in the survey.

However, the interviews were unstructured by allowing detours for users to expand and go

slightly off topic if they seemed like they were opening up about their lives. Allowing users

to detour from the interview questions provided an opportunity for developing trust which

would not have been available if the users chose the survey instead.

13

3.3.4 Observation

A fly-on-the-wall ethnographic observation of an online Hackathon and a second

participatory observation with an international Data Challenge were conducted (Martin & Hanington, 2012, p.90). Both digital events implemented co-design processes with different stakeholders to find solutions for public policies in response to COVID-19. These online collaborations were chosen for observations because they were related to the context of this co-design project. The organizations brought different stakeholders together digitally to strategize and create possible solutions to COVID-19 in Sweden and other countries. Both included different stakeholders in the creative process and tried to make a difference in public policy by addressing social and cultural issues that come up when dealing with COVID-19. The focus of the observations was to see how these organizations attempted to successfully communicate with participants using different digital tools. As well as identify what methods did or did not work in facilitating ideation from the users in a digital

environment. Such as providing participants enough information to complete the tasks on their own, giving them tools they need to succeed, and also how participants can struggle using digital tools in the way organizers intended.

3.3.5 Literature review

The research process began with a literature review as well as looking into online resources for co-design methods. The literature review described the importance of including users into the design process and how trust plays a major role in that. In addition to explaining how to successfully include users in the co-design process through the use of ICT.

Facilitating trust between the organization and users in the co-design process seemed crucial to successful ideation and innovation. The online resources provided inspiration for methods to implement in the digital co-design workshop. By combining methods learned from

literature, online resources, as well data from the initial surveys and interviews, the designer identified the role trust plays in traditional co-design processes and moved forward with nurturing trust through digital tools and digital co-design.

3.3.6 Concept map

The methods conducted during the design before design process i.e. crowdsourcing, interviews, and research provided a wealth of information about two specific topics. How users experience information sharing in Sweden and what users need from a facilitator in a digital co-design space to express their ideas openly. The information regarding COVID-19 information sharing contributed to the context of the workshop activities. Whereas the information regarding successful digital co-design guided the overall design process.

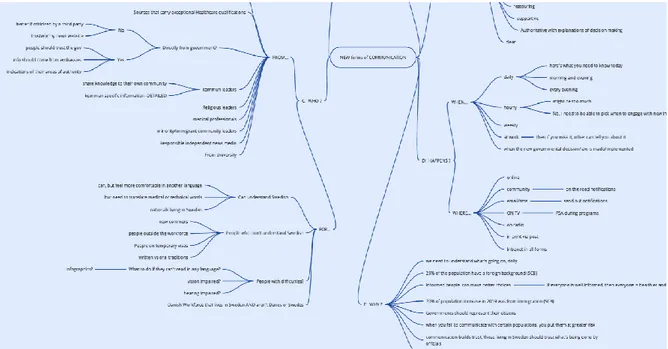

Concept mapping (Martin & Hanington, 2012, p.38) was used to identify commonalities and plot new insights (see Figure 2). Such as the difference between public and private sectors when co-designing. What users need in a digital co-design space and what providing that to users could result in . For example, many participants stated different aspects related to trust and empowerment contributed to them expressing themselves in collaborative settings. The designer then used the maps to create follow-up questions and activities in the digital co-design process.

14

Figure 2. Concept map: Used to plot commonalities and identify what could be needed when conducting digital co-design.

3.4 Co-design

3.4.1 Co-design the workshop

The information gathered from the aforementioned methods was used to co-create a workshop with the participants. By including users into the design process, the designer hoped to create a sense of trust and open communication. “Trust can also be enabled

through designing shared material resources tailored to or co-designed with specific groups. These activities enable contextually sensitive group understandings, empathy and

communication” (Clarke et al., 2019, p.4). Users were included in the creation, testing, and conducting phases of the digital co-design workshop. Their responses in the initial phases provided inspiration for the workshop activities. Users then tested and conducted the workshop in both group and individual settings. The designer included their own responses to the workshop activities as guidance and to show that it was a collaborative process which further developed the sense of community and trust.

3.4.2 Usability testing

Multiple usability tests were performed by participants before the first workshop to ensure it was understandable and self-explanatory. There were few people who opted to do the

workshop on their own time, outside of the live scheduled workshops. These asynchronous participants needed to have all the information and tools available to be able to perform the tasks on their own. In the spirit of co-design, participants were included in the testing of the workshop. The group usability test was conducted with 3 participants before releasing the workshop to everyone else. Another participant who had prior usability testing experience went through the workshop on their own, testing different aspects and emailing the results

15 throughout the week leading up to the workshop. They provided new insights, challenged design decisions, and pointed out errors in the design. Their help resulted in an improved workshop experience. It also developed a sense of trust between the testers and the designer. The designer was open to criticism and showed appreciation of users’ time and effort by making alterations according to their feedback. These factors contributed to a great working relationship and ideation process, as these users were eager to share their opinions, knowing the designer would be receptive of their input.

3.4.3 Closing user participation

To provide participants with another chance to influence the co-design process, they were provided with opportunities to share last minute comments, concerns, and criticisms about the design process and facilitation after the workshops. The workshop was to be iterated on based on feedback from workshop one participants. Therefore, a closing comments section was included in Miro (the digital workshop) as well as a follow-up survey sent out a few days after the workshop. The follow-up survey was created as a response to no participants filling in the comments section in Miro. Participants’ feedback from the first closing survey (see Appendix C) was used to iterate on the workshop before workshop two took place. One participant had critiques about the survey itself, thereby leading to an iteration of the closing survey, resulting in a second version (see Appendix D) which was given to workshop two participants.

4. DESIGN PROCESS 4.1 Define

Exploratory research was used to gain a better understanding of the problem area. As a result, the designer was able to empathize and gain insight into how different demographics within expat communities are dealing with information sharing about COVID-19 in Sweden. This information was used to build a foundation for further research and design work. By taking into consideration where and how each participant accessed information about the government’s actions against COVID-19, led to identifying gaps in the data of the problem area. The designer could ask about this lack of information in future interactions. Gathering data about the problem area also helped the designer empathize with participants in their varying levels of frustration. Empathizing with users helped the designer to better

communicate and nurture trusting relationships. This was done by responding to users in different ways, according to their experiences and views regarding information sharing. Understanding users’ pain points and values painted a better picture of who they were as individuals. Being able to empathize with users as individuals further deepened the relationship.

4.1.1 Surveys

The initial survey used open and closed questions to provide a better understanding of users’ familiarity with online collaborative tools, their experience of COVID-19 in terms of

information sharing, as well as what contributes to them sharing their ideas in a group. For example, users were asked if they have any prior experience of collaborating online and how they envision collaboration online to be. Most participants had some prior experience with collaborating online and each pointed out the drawbacks to it. Participants pointed out the challenges with collaborating online, such as "maybe more difficult to express my opinions due to not knowing the individuals very well." Thought it was "complicated by glitches in the

16 technology and connections" as one participant stated and requires “some support to learn how to use them.” Another participant said, "I think it can either be very productive or extremely unproductive. In my experience, there's very little in between." However, one participant stated, "I think it is a good solution during periods like this one we are facing right now. I try to listen to the others online and to talk my truth. " The insights gathered from the surveys were used as guidance for designing the digital co-design activities in the next stage of the design process. The designer attempted to address these issues, by

establishing a familiar relationship with the participants, providing them with information on how to use the tools and giving onboarding support. In addition to staying focused and trying to make the workshop a productive experience for all the participants.

4.1.2 Interviews

The interviews gave a wealth of information about the participants and aided the design process. Participants were asked which communication platform they preferred for

conducting the interviews. The interviews were conducted using Zoom, Facebook messenger, and mobile calls. With each interview, other topics about their lives came up casually in conversation. Their history, how they ended up in Sweden, their relationship status, family structures, and their work and emotions. A result of the interviews being open to detours, provided a level of trust between participants and facilitator. This open relationship would result in a more friendly environment where participants felt safe to share their honest opinions and ideate with others. Another benefit to the detours in conversation was that the designer was able to identify deeper issues beneath the surface problem of information sharing. The designer realized that the issue was not a lack of information but a lack in Swedish language and cultural understanding. The expats that were integrated into Swedish society did not experience issues with accessing information. These expats still had

suggestions on how the information could be better distributed to their community though and therefore were still relevant to include in the digital co-design workshop. Having users from within the same community with varying experiences added to the discussions and ideation during the workshop.

4.1.3 Observation

The fly-on-the-wall observation (Martin & Hanington, 2012, p.90) provided the opportunity to observe which ICT and methods could be used to provide users with a digital co-creation space to ideate in. This observation took place before the co-design process started, thereby providing ideas on how to proceed with this project. The Hackathon organization provided digital tools to help participants focus and complete tasks. Hackathon organizers had an announcement, resources, and question channels on slack where participants could ask questions. They gave a detailed schedule with information about the live streams, a PDF with tips and tricks, and explained the process of creating groups and submissions.

These methods were used as inspiration for this project. In this project, participants were given information early and time to process it in order to help them familiarize themselves with the tools and ideate better in the real-time workshop. Users were given the option to work on the workshop alone, and then come back and contribute their ideas to the workspace. Just as the participants in the Hackathon would work on their own and come back to share their contributions. One negative aspect to the Hackathon that was observed, was the overwhelming amount of information. It seemed as if users were bombarded with information in the form of emails and notifications. It is understandable that with such a large amount of people participating (7,400 participants) that there needed to be an abundance of information to coordinate people efficiently. However, a balance needs to be

17 struck between giving users all the information they need to succeed but also being conscious of each interaction and respecting participants’ time and energy.

4.2 Recruit

4.2.1 Recruiting participants

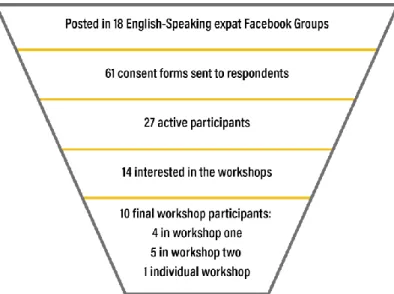

In order to co-design a digital workshop with participants, certain methods were used in the beginning stages to find participants, gain a better understanding of the problem domain, and to include participants in the design process. These time-consuming activities are

referred to as “design before design” (Pedersen, 2016). Such as following-up, scheduling, and coordinating people with different availabilities which can be difficult at times. By the time the project started the 61 people who initially showed interest, dwindled down to 27

participants of varying involvement (see Figure 3). However, once participants agreed to the activities, they were made to feel valued and heard which could have contributed to their continued involvement in the co-design process.

Figure 3. Diagram of participant drop off between recruitment and the final workshop.

4.3 Plan

4.3.1 Co-design the workshop

In attempt to use a tool that most people were familiar with, participants were asked if they ever participated in a co-design workshop or if they have used any online collaborative tools before. Most users were familiar with online collaboration and cited which digital tools they used. Only one user had experience with a collaborative whiteboard and that was Miro. After researching what other collaborative tools offered, such as digital whiteboards, video

conferencing, and organizational tools, Miro was selected as the platform for the co-design workshop. Miro provided descriptive, helpful, and concise information about their platform before having to commit and create an account. Miro had simple features which could be useful in collaborating digitally and reduce onboarding time. Using minimal features such as their sticky-note and comment features would provide an experience similar to that of physical workshops. Miro has an integrated video conferencing option, but that was only available in their paid version. Which resulted in Zoom being used alongside Miro for video

18 conferencing in this project. Miro also provided templates which were used as inspiration and adapted in this project’s workshop.

The adapted templates provided a format for the activities inspired by the initial survey and interview responses. As suggested from the usability testing, starting points were added to help guide people while remaining open as to allow for ideation. It is a fine line to walk between providing participants with inspiration while not nudging them into any particular stance. Users were given enough information to start a discussion, but not too much that it would then stifle their designer mindset. “To create designer mindsets, one of the major roles for new media and new technologies is not to deliver predigested information to individuals, but to provide the opportunity and resources for social debate, discussion, and collaborative knowledge construction” (Fischer & Scharff, 2000, p.397).

4.3.2 Usability testing

Including participants in usability testing improved the workshop by making it easier to use and more understandable. The main results from the group usability test was that people do not read instructions. Two out of three users stated that they would rather try and error and only resort to reading instructions if completely lost. One participant said there was too much text which added to the desire of not reading. A synthesized PDF version of instructions and tips were created to be faster and easier to read than the extensive help option that Miro provides. However, after the usability test the amount of text was reduced and extra information from the activities that were not vital to completing the tasks were removed. Another example of the changes resulting from the group test is users asking for inspiration or guidance in the activities. Instead of the activities being left empty, starting points for discussion were added. A few branches were added to the mind map, the designer shared their own feelings in the Likert scale, and provided examples in the One, Two and More activity.

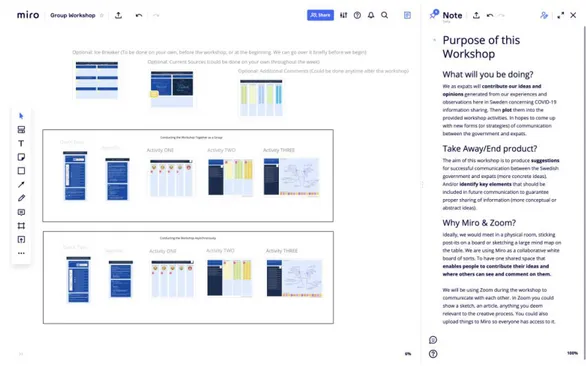

One participant conducted usability testing on their own and messaged the designer throughout the week leading up to the workshop. This participant pointed out the lack of a purpose statement in the workspace, as well as the expected end-product or take-away from the workshop, and an explanation of why Miro and Zoom were being used. These points were explained during conversations with participants and the designer expected to go over them in the introduction of the live workshop. However, agreeing that this was relevant information and it would help with expectations, this information was added to the

workspace. A pinned note was added that would appear at the side of the screen when people entered the workspace (see Figure 4). This participant also pointed out glitches and bugs in the Miro software, which needed to be addressed and the designer provided alternative methods for doing things. This proved to be very useful in the second workshop as another user experienced the same issues.

19

Figure 4. “Purpose of this Workshop” pinned note to side of workspace as suggested by test user to better prepare participants for the digital workshop.

4.4 Conduct

The workshop was further iterated on between workshop one and workshop two, based on feedback from participants. Workshop one was more open whereas workshop two used a semi-filled mind map generated from workshop one responses. Comparing both workshops revealed a noticeable difference in how much information was added to the boards in both sessions. The prefilled mind map in workshop two did not generate as many responses as workshop one (see table 1). One possible reason for that is that the openness of workshop one helped the participants see themselves as responsible for filling in the workshop with ideas and coming up with solutions to the unanswered questions. Whereas in workshop two, most of the generative work was already done for them by the previous group.

20

Table 1. Overview of the workshops: comparison between workshop results

In order to create a trusting and welcoming atmosphere, small notes with information about each participant were written down and that information was used when grouping the workshops. Commonalities of interests and which personalities would get along best were considered. For example, one survey question asked if people thought they were more outspoken or withdrawn with sharing their ideas in group settings with strangers. Different personalities were purposefully mixed in the group workshop. In the closing survey all participants except one stated they thought the atmosphere was friendly and welcoming. That outlier experienced a lot of technical issues and stated, “You, the host were very welcoming and kind. Some technical issues caused some issues in how smoothly the conversation could go. I didn’t gel with all personalities in the group and this caused me to hold back a little bit.” The rest of participants thought the final groups in the workshop were welcoming of each other which made ideation and discussion very successful. This was evidenced in how many comments, sticky-notes, information, and ideas were generated at the end of the two real-time workshops and the individual asynchronous workshop.

4.4.1 Introduction and troubleshooting

Participants were given access to Miro a week in advance in addition to being provided with a “Quick Tips” PDF (see Appendix E) and an Agenda for the workshop (see Appendix F). 90% of participants appreciated having access to Miro a few days in advance and those that familiarized themselves with the tool ahead of time, thought the platform was fairly easy to use. Giving them tools they needed before the workshop gave them a sense of confidence going into the design space. Another onboarding method was the facilitator being on Zoom 30 minutes before the workshop to help with troubleshooting. 80% of participants attended the meeting early to take part in that session. One participant (who did not access Miro or Zoom ahead of time) stated in the closing survey that they would have appreciated going over the features before each activity. “Written instructions were nice, but a bit

overwhelming.” Even though this was one user’s opinion, the comment seems valid as it corresponds with what was observed in the group usability test. Minimal text and reiterating features before each activity could make participants feel more confident in themselves and in the digital platform.

21 One attempt to get people to know each other was suggesting they add to the icebreaker activity and word cloud in the week leading up to workshop. Unfortunately, only 3 of the 9 real-time workshop participants added to those activities before the workshop. That

interaction was mainly between the participants and the facilitator. Busy schedules, jobs, or studies prevented people from contributing to the workshop during the week. However, some participants suggested a pre-session where the group could familiarize themselves with each other. Then a second session for innovation and maybe a third follow-up session. This could be a great way to make people commit to setting aside time to get to know each other instead of activities being optional and therefore not a priority in a busy schedule.

4.4.2 Icebreaker

The icebreaker activity gave participants insights into each other’s personalities and interests which made them more comfortable and able to ideate together (see Figure 5). In the closing survey participants stated that they appreciated the icebreaker. One participant stated in the closing survey, “taking a few minutes to talk with everyone and the ice breakers helped, joking always helps.” The questions in the icebreaker helped people to share about what they missed and allowed them to empathize with each other. For example, all of the participants could relate to missing their families back home. The icebreaker leveled the playing field and reminded participants that they are on the same team. They are all expats living in Sweden, struggling to understand what the Swedish government is doing in response to COVID-19. Giving participants a sense of community and equality helped them to open up and be more creative.

22

Figure 5. Optional Icebreaker Activity which asks positive questions about users’ interests to get a better understanding of each other before the ideation process.

4.4.3 Word cloud

The word cloud was a visual to spark imagination and provide new resources to group members who struggle finding pandemic information (see Figure 6). An issue that became evident during the explorative research process was that there is a lot of information out there for expats, but they do not have access to it. Either because they do not know where to look or do not know who to trust. The word cloud gave them a chance to see where others in their community are going for information about COVID-19. Laying out the information in such a way gave workshop group members a chance to help each other find news sources through adding comments to the exercise. Helping each other contributed to a friendly and supportive atmosphere amongst workshop participants.

23

Figure 6. Word Cloud to spark imagination and discussion about news sources participants currently use for COVID-19 information.

4.4.4 Pictorial Likert scale

In surveys and interviews, many participants stated that they felt as if they were not being represented in Sweden. This lack of representation lead to a wide range of emotions. As emotions can range at one time, participants were asked to add a sticky-note to all emotions that applied to their experiences on a pictorial Likert scale (see Figure 7). The facilitator shared 4 sticky-notes as examples of how users could potentially respond. This served not only as an example but an opportunity for the facilitator to connect with participants and become part of the community. The level of complexity and engagement ranged from low to high. Users could simply add a sticky-note with their name or leave it blank if they wanted to remain anonymous. That option was quick, easy, and gave them a sense of anonymity if they wanted. The option to not respond was also made available to them. If participants wanted to go more in depth and explain why they felt the way they did, they could write a comment on their sticky-note. Most participants wanted to share their feelings and reasonings to the group. A majority of the participants were feeling anxious and unsure, as well as feeling sad and angry. Only a few felt confident during the pandemic but that was more related to being in control of their own behavior and unrelated to Swedish authorities’ actions. As

participants have described themselves as feeling unheard or underrepresented during the exploratory phase, this activity gave users a platform to share their feelings with others and be heard.

24

Figure 7. Pictorial Likert scale of participants’ emotions as a means to support relationship building. Participants could share and empathize with each other before ideating together.

4.4.5 “One, two and more”

The “One, two and more” method (Thiagi Group, 2019) was adapted for this project and was successful in getting participants to discuss and ideate with each other about how

information sharing could be improved (see Figure 8). The discussions added to the group dynamics and affirmed that they were not alone in their struggles and opinions. Originally, the first question was positive, “What currently works?” As with the icebreaker, the

workshop was to have a positive tone. However, during the first usability test one participant stated, “but nothing is working!” and then disengaged. Most likely a result of feeling defeated in the situation. The question was changed to “What currently doesn’t work?” as a way to avoid potentially excluding users from the discussion. This question gave participants the chance to vent their frustrations and add to the discussions. Everyone had something to contribute and the discussions thrived as a result of changing the question to something more critical.

25

Figure 8. “One, two and more” activity done individually and in a group: stimulates critical thinking and discussions about how to improve information sharing for expats.

4.4.6 Mind map

The mind map was co-designed with participants. Originally the mind map was left blank as to not limit or direct participants into any particular direction. Only “feels like” and “looks like” were included, attempting to keep the ideation space open. However, during the group usability test the participants thought the mind map needed more direction as they did not know where to begin. They suggested including more text, prefilling some branches, and guiding them in the order they should fill in the branches. As a result of their feedback, the initial surveys and interviews were reviewed to get inspiration of words to include into the mind map. The mind map was to be representative of their ideas, thus showing participants that the facilitator valued their input and was open to hearing their suggestions. Letters were added to the branches to guide participants through the mind map. The participants

suggested using numbers, however numbers seemed more restrictive. The letters could be used as a guide but not restrict users from jumping around if another idea pops up in the process, which numbers could possibly prevent. By inviting participants to give their opinions of the mind map before the workshop, it sparked more ideation with the participants during the real-time workshop (see Figure 9).

26

Figure 9. Close up of workshop mind map: The capitalized words were provided by the designer and users filled in the rest of the branches together.

Note: For a full view of the Workshop mind map (see Appendix G).

4.5 Synthesize

4.5.1 Closing survey posted in Miro

There was a survey section in Miro where participants could add comments about the activities, the workshop, or other general comments (see Figure 10). There were two workshops scheduled, with the intention to iterate on the workshop before the second workshop. The iterations would be based on feedback from the first round of participants. No participants left feedback on Miro, which prompted the designer to create a follow-up survey.

Figure 10. Closing comments section in Miro platform that was never filled in which led to the creation of the closing survey.

27

4.5.2 Closing survey

As no one filled in the closing survey section in Miro, the facilitator responded by creating a closing SUNET survey. One participant answered the questions but also provided criticisms and advice on how to improve the survey for clarity. The feedback about the workshop was used to iterate on the workshop before the second workshop took place. The feedback about the survey itself lead to a second version which was clear and concise. The second version of the survey was sent to participants from workshop two. The second survey provided more detailed information about the digital co-design platform and the relationship between user and facilitator. The second survey was a big improvement, however after reviewing it, there were 2 more questions that needed to be asked to help answer the research question. Each participant was messaged through their preferred platform and responded right away. The information from the closing surveys and subsequent follow-up questions led to interesting findings (see table 2) and validated the process of nurturing trust in order to provide a more successful space for innovation.

Table 2. Interesting findings: validation of the trust building process with users. All participants trusted the facilitator and thought the platform was appropriate for ideation.

5. MAIN RESULTS AND FINAL DESIGN 5.1 Main results

This project set out to identify what users deemed important to better ideate in a digital co-design setting. It was hypothesized that the major contributor to ideation and productive digital co-design processes was trust. The designer explored how to facilitate trust and develop meaningful relationships with users throughout the design process. “Meaningful” meaning producing value and ideas that could be used for innovation. The process revealed that users do need to develop relationships and trust, as well as feel empowered (confidence

28 in themselves, the facilitator, and the digital platform) to successfully ideate with others digitally.

Trust could be achieved by understanding the motives of others in the group, resulting in more open discussions and varying decisions. Participants stated they are able to express their opinions more openly if they trust their group members will not judge them for their views. One participant described a previous project to exemplify the importance of trust in the innovation process, “If we didn't trust the parties who financially supported the

innovation process, the parties who contributed ideas, the parties who evaluated the ideas, and the parties who implemented process results, then innovation would never have

happened.” Another participant went on to describe trust building as a process. “Trust is the last stop on a path that begins with being comfortable with the facilitator, feeling respected, feeling that your thoughts are welcome, and lastly feeling your thoughts are valued. Trust develops from that.” Trust is the last step of a long process. When engaging in digital co-design activities, co-designers and/or facilitators can build up trust by making participants feel respected, welcomed, and valued. This is especially important when interactions are only done through digital means. Facilitators will need to also provide users with the tools they need to feel confident in their own technical abilities and in the digital tools themselves. i.e. providing users with information about features ahead of time. It will take extra time and planning, but once trust is established during the digital co-design process, users will feel empowered and openly contribute to the creative space. Building trust and empowering users will result in a more successful ideation and innovation process.

5.2 Final design

5.2.1 Digital co-design guidelines

The final design solution is a set of guidelines (see Figure 11) for nurturing trust amongst users and empowering them in a strictly digital co-design environment. For the purpose of facilitating meaningful and productive ideation and innovation Users can better ideate solutions that fit their needs in a digital co-design process if trust has been developed, and they feel safe and confident enough to share their ideas with the group. Nurturing trust amongst users in the ideation phase leads to richer and more successful innovation when co-designing digitally.

In order to build trust with users in a digital co-design space, the designer needs to develop a rapport with the users, empower them, consider users’ needs when designing the digital platform, and remember that the advantages outweigh the disadvantages.

29

Figure 11. Digital co-design guidelines: Overview of what needs to be considered to build trust with users.

5.2.2 Develop rapport

How can a designer or facilitator develop trust with users in digital co-design for better ideation?

Be friendly.

• Provide a welcoming and nonjudgmental atmosphere every time you interact with users. Show a sincere interest in them and their ideas. Even if it is a quick message, an email, or during a session.

Consider users’ mental states.

• When discussing a sensitive topic, remember that emotions are high, and people are impacted in different ways. You cannot address each person in the same way,

adjustments will need to be made according to circumstances and personalities. Engage on users’ preferred platform.

• Regardless of where the initial call to action took place, communicate with users through their preferred digital platform, whether that is social media, email, or mobile.

Remember details and refer to them.

• Make users feel heard and valued by remembering aspects of their life. This could be done simply. E.g. copy/paste generic information in messages for efficiency. But personalize the greeting so each user feels you are writing to them personally.

30 Be prepared as a facilitator.

• Prepare the activities, provide users with preparatory information, guide the session, and respect the time. If users feel confident in your skills as a facilitator, they will trust that you can guide them into successful ideation and innovation.

Remember and work around consent.

• Note which users did not give consent for i.e. image recording. Work around it without drawing attention to the issue. For example, have cameras on for an icebreaker activity but announce you will start recording afterwards. This allows users to see and meet first and then turn off cameras if desired while working. Respect users’ wishes.

5.2.3 Empower users

How can a facilitator empower participants to improve ideation and innovation? Let users feel knowledgeable.

• Give users information about the topic early on they can become confident in their understanding of it. The confidence gained will empower them during discussions with other participants.

Prepare users.

• Prepare users for the workshop in advance. Give them tips, tools, and an agenda with the purpose of the co-design session and the expected results. They will feel more confident in themselves and appreciate you for helping them achieve their goals. Extend the time of the event.

• Interacting multiple times helps users feel more confident in themselves, the

platform, and with everyone present. If they are unsure of their abilities to perform, they could lead them to hold back during the ideation process.

Encourage a sense of community.

• Introduce users to the other group members so they get to know each other better and create a sense of familiarity. A casual pre-session where users acquaint themselves with their fellow group members could be useful.

Create a safe space.

• Create a friendly atmosphere without judgement. Reiterate rules of engagement at the beginning of a session to reaffirm that judging others or being rude will not be tolerated. This sense of security will give the participants the confidence they need to share openly.

Protect users’ data.

• Striving for data privacy is key to empowering participants to share more openly.

5.2.4 Digital platform