Guardians of Democracy? On the

Response of Civil Society Organisations to

Right-Wing Extremism

Erik Lundberg*

This article expands on the understanding of the role civil society organisations (CSOs) play in counteracting right-wing extremism. Drawing on central strands in the defending democracy literature, this article introduces a typology to classify the responses of CSOs to right-wing extremism. The typology takes into account the distinction between tolerance and intolerance on the one hand, and active and passive political participation on the other. What is more, it allows for a more fine-tuned analysis of a variety of CSO responses vis-à-vis extreme right-wing movements. This distinction is important as it allows for a better understanding of the democratic role of civil society in general and the responses of pro-democratic civil society to political extremism in particular. Using this typology as a point of departure, the article con-tributes empirically by exploring how local CSOs in the Swedish town of Ludvika responded to the foremost neo-Nazi movement in the Nordic countries, namely the Nordic Resistance Movement (NRM), prior to the 2018 Swedish election. Drawing primarily on the perspective of civil society leaders, the findings show that local CSOs are generally intolerant of the NRM and have engaged in opposition to the movement. Notably, responses tend to be more oriented towards promoting dialogue and the importance of public discussion in civil society rather than using confrontational tactics such as protests and civil disobedience. The article concludes that CSOs serve as bulwarks against right-wing extremism at least during politically charged situa-tions; however, differences in tolerance and political participation indicate that CSOs respond differently to right-wing extremism.

Introduction

Over recent decades, the upsurge in right-wing extremism has represented one of the most dramatic developments in many Western democracies. Extremist movements, neo-Nazi subcultures along with attacks on immi-grants and racist violence have become commonplace in many countries (Mudde 2017; Malkki et al. 2018). Recently, scholars warned that the im-pact of the coronavirus pandemic has increased opportunity for leaders and

* Erik Lundberg, Department of Political Science, Dalarna University. Email: elb@du.se. This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

institutions to weaken liberal values and norms, while providing space and an audience for radial groups to propose violent extremism (Ackerman & Peterson 2020).

A central discussion revolves around how democratic actors respond to the increasing activities of right-wing extremists and the fundamental ques-tion on tolerance of the intolerant – that is, how to deal with movements that are not against democracy per se but that are at odds with liberal democracy. Scholars have paid great attention to reactions to extremism by institutional actors (mainly state) and established political parties. The discussion centres on the way democratic rulers respond to political extremism – for example, the role of anti-extremist legislation and the various forms of collaboration with populist parties (Widfeldt 2004; Capoccia 2005; Kaltwasser & Taggart 2016; Malkopoulou & Norman 2018).

The focus on the institutional responses of state actors and established political parties is not surprising since it is they who are the dominant play-ers in the political arena and who hold legal authority. However, previous research has paid limited attention to the role and responses of civil society organisations (CSOs) – that is, the intermediate associations, movements, interest groups, etc. that operate between the state and the market. In work focusing on how CSOs respond to right-wing extremism, at least two argu-ments become apparent. One follows the argument put forward by Putnam (2000) and the view that civil society has the role of bulwark against extrem-ism (Pedahzur 2002, 2003, 2004; Michael 2003; Fallend & Heinisch 2016, 330–1) and democratic counter force to the growing presence of right-wing populism (e.g., Jämte 2018; Meyer & Tarrow 2018; Roth 2018; Siim et al. 2019). Indeed, research shows how both protests and resistance within civil society raise awareness and may dampen the willingness of citizens to affili-ate with extremist movements (Art 2007), and also how CSOs serve as advi-sors and watchdogs vis-à-vis the government, thus stimulating government repression of extremism (Michael 2003; Pedahzur 2003; Minkenberg 2006; Eatwell 2010).

However, several scholars have pointed out that the effects of civil soci-ety may also be illiberal (Putnam 2000, 23, 358) and refer to the ‘bad’ or ‘dark’ side of civil society (Chambers & Kopstein 2001). Studies indicate that referring subconsciously to civil society as being an antidote to threats of democracy, such as right-wing extremism, may be misleading (Eubank & Weinberg 1997; Kwon 2004; Rydgren 2009; Rydgren 2011; Jenne & Mudde 2012). In her study on the collapse of the Weimar Republic in Germany, Berman (1997) argues that civil society does not guarantee sustained and stable democratic governance; indeed, in the case of the Weimar Republic, it contributed to the mobilisation of Nazi-sympathisers. Likewise, Molnár (2016) concludes that in the case of Hungary, civil society played an import-ant role in the rise of right-wing radicalisation.

Despite the growing interest in how democratic actors respond to politi-cal extremism, the role played by CSOs has been given relatively little atten-tion in the literature. What is more, we miss framework that would serve to uncover various types of responses directed at extreme right-wing move-ments. Therefore, the aim of this article is to bridge this research gap by pro-viding new empirical and theoretical insight into how civil society responds to right-wing extremism in a democratic context. More specifically, this arti-cle answers the following two research questions: Do CSOs respond with tolerance or intolerance, and do they do so actively or passively? To what extent and how do the responses differ between different types of CSOs? With this aim, the study contributes to previous research in several ways.

First, drawing from central strands in the defending democracy literature, this article introduces a new typology to classify the responses of CSOs to right-wing extremism in democracies. Second, using this typology as a point of departure, this article contributes empirically by exploring how civil soci-ety leaders from various types of locally based CSOs in the town of Ludvika in Sweden responded to the Nordic Resistance Movement (NRM) prior to the 2018 Swedish election when the NRM campaigned intensively to maintain representation in the local government assembly. Third, this study answers the research question by combining a quantitative and qualitative analysis, which contributes to a better understanding of the role of CSOs in counteracting political extremism. All in all, by introducing a new typology and providing empirical insights, the ambition of this study is to contribute to a renewed understanding of the role CSOs have in counteracting political extremism. This is important as it allows for a better understanding of the democratic role of civil society in general and the responses of pro-demo-cratic civil society to political extremism in particular.

The article is structured as follows: After this introduction, I present the theoretical framework first by introducing the concept civil society and second by presenting the typology for classifying responses to right-wing extremism in democracies. The third section presents the empirical case and the data and methods used, and the fourth section presents the empirical results. The concluding section summarises the results.

Theoretical Framework: How CSOs Respond to

Right-Wing Extremism

Defining Civil Society

The term civil society has been a point of reference for philosophers since antiquity; however, interpretations of what it means have varied greatly (Edwards 2014). Contemporary literature draws heavily on the conception

of civil society developed by Montesquieu and de Tocqueville, who stressed the relevance of free association as a means for citizens to counterbalance the state and develop civic competencies. Thus, civil society is often concep-tualised as being an arena in society that is distinct from the state and the market, and usually the family, where collective action in associations and through other forms of engagement takes place (Cohen & Arato 1992). This article follows this well-established conceptualisation and draws attention to the organised part of civil society and the activities that take place within some other sort of organisational framework, either permanent or tempo-rary, in which membership and activities are voluntary.

The question as to the democratic role of civil society has rendered great discussion in the literature. In line with the ideas of Alexis de Tocqueville, scholars claim that civil society plays a key role in ‘making democracy work’ and in sustaining a vibrant democracy (Putnam 1993, 39, 89–90). Civil soci-ety forms the infrastructure of the public sphere within which public opin-ion and public judgement are formed and which provides people with the capacity to resist what they do not like (Warren 2001). Besides, according to Putnam (2000), CSOs create bridging ties and instil in their members habits of cooperation, solidarity and ‘public spiritedness’. The optimism and hope regarding the democratic role of civil society are leading motives in the literature and are apparent in the word ‘civil’, which is often associated with something inherently good and with elements that both make up a good society and contribute to strengthen or uphold democracy. However, some scholars have warned against a rose-tinted picture of civil society, pointing out that political activity in civil society may not necessarily lead society in a pro-democratic direction but may instead support anti-demo-cratic and totalitarian movements (Berman 1997; Eubank & Weinberg 1997; Chambers & Kopstein 2001; Kopecky & Mudde 2003). Furthermore, CSOs may also nurture bonding ties that increase existing social cleavages and exclusion, and produce ‘downward levelling norms’ (Portes & Landolt 2000, 533) that are counteractive to democracy.

In order to detect the various roles of civil society in defensive democ-racy, scholars have distinguished between three analytical principal types of civil society, referred to as ‘civil society I’, ‘civil society II’ and ‘civil soci-ety III’ (Foley & Edwards 1996; Booth & Richard 1998; Pedahzur 2004). The first two represent ‘pro-democratic civil society’, that is, organisations that contribute to democracy (Pedahzur 2004). ‘Civil society III’ includes the violent and destructive side of civil society that promotes ideas that undermine democratic values (Booth & Richard 1998). Included here are the NRM and other organisations that observe Nazism, fascism and other ideologies that have ultra-nationalistic, xenophobic aims.1.

CSOs pertaining to ‘civil society I’ direct their efforts against ‘civil society III’ in order to undermine extremist infrastructures and reduce the scope of

their activities (Pedahzur 2002, 142). These organisations respond by rais-ing public consciousness and knowledge about extremists; by mobilisrais-ing support against such movements; and by supporting victims of extremism. Furthermore, they are involved in more radical violent activities and civil disobedience as well as activities that foster patterns of civility in the actions of citizens in a democratic polity, primarily through education (Pedahzur 2002). ‘Civil society II’ emphasises the importance of CSOs as a counter-weight to the state. CSOs included in this principal type respond to political extremism by mobilising against a tyranny state or by limiting state confor-mity to political extremism to preserve the state’s democratic values.

The distinction between the three principal types of civil society offers a novel framework by which to understand the role of CSOs vis-à-vis polit-ical extremism. However, the framework is extensive and offers relatively little guidance to uncovering various types of responses directed at right-wing extremism. For example, ‘civil society I’ embraces responses cover-ing everythcover-ing from strengthencover-ing citizen competencies and supportcover-ing victims of extremism to mobilising support against extremist movements. Furthermore, the existing framework does not take into account the level of political participation or the fundamental query of tolerance of the intoler-ant. Although we have good reason to assume that many CSOs defy extrem-ist movements, we need analytical tools that make visible a variety of CSO responses, including the fact that CSOs may tolerate right-wing extremism and respond by being passive. This is important for a full understanding of the role CSOs have in counteracting right-wing extremism.

Typology for Classifying the Response of Civil Society to Right-Wing Extremism

Drawing on the defending democracy literature and writings on civil soci-ety, this section outlines a new typology for classifying key dimensions in civil society response to right-wing extremism in democracies. The typology is based on Downs (2012, 30–1) and distinguishes between four types of re-sponses that vary along two axes: tolerance and intolerance on the one hand, and passive and active political participation on the other (see Figure 1). The vertical axis draws attention to the democratic paradox of how to toler-ate the intolerant (Popper 1945). While tolerance requires a certain degree of intolerance, drawing on limits is necessary when it comes to defending democratic principles and the inalienable values on which our democracies are based. On the tolerant end of this axis, the dominant tendency is to ac-cept, tolerate or perhaps even welcome right-wing extremism. Civil society acknowledges the right of extremists to participate actively in political life, including their freedom of expression, and their right to vote and to stand for election, and accepts individuals or groups of individuals within such

movements (Gibson 2006, 22; Forst 2013). Intolerance, at the other end of the axis, refers to the rejection of such rights and individuals or groups of individuals within such movements since they are at odds with democratic liberal principles (Capoccia 2005).

The horizontal axis draws attention to the level of political participation and distinguishes between active and passive political participation. As pointed out in the social movement literature, various political opportunity structures shape the degree to which an organisation influences policy or politics, such as organisational resources, and legal institutional and polit-ical factors and structures (Goodwin & Jasper 1999; Kriesi 1996). As such, the extent to which CSOs mobilise responses due to right-wing extremism varies. Active political participation refers to ‘actual’ participation or ‘for-mal’ political participation, and includes any attempt to influence public attitudes, government decisions or political outcomes that limit the room for right-wing extremism to manoeuvre. Passive political participation is the lack of political participation. However, passive political participation does not suggest a complete lack of political interest or attentiveness to the issue. Accordingly, participation may be latent and include ‘pre-political’ or ‘potentially political’ activities that involve attention to and involvement in society and current affairs. In this typology, however, passive political partic-ipation draw primarily attention to the lack of manifest particpartic-ipation taking place in the public sphere.

At the intersection of tolerance and passive, accept embraces a high degree of tolerance in combination with a lack of political action in relation

Figure 1. Classification of the Responses of Civil Society Organisations to Right-Wing Extremism.

Note: Modified model based on Downs (2012, 30–1). Intolerance

Ban Protest

Tolerance

Accept Dialogue

to right-wing extremism. This type of response is reflected in the study by Berman (1997), demonstrating that tolerance, silent acceptance and a lack of political responses from civil society contributed to the mobilisation of Nazi-sympathisers. Thus, this stands in contrast to the argument by de Tocqueville (2000) and Putnam (1993) that civil society is contributive to democracy and may thus reduce the manoeuvring of right-wing extremism.

On the upper-left, ban embraces responses that demonstrate a high intol-erance of right-wing extremism and an unwillingness to engage in formal political participation. This includes responses that affirm any measures that limit civil and political rights of movements that do not respect liberal democratic principles (Capoccia 2005), for example, legal restrictions, limits freedom of speech and limits on an individual rights to stand for election. However, the response is passive. Thus, it recognises CSOs who take a stand against right-wing extremism but who for various reasons do not mobilise against such movements because of, for example, a lack of organisational resources, the fear of reprisal or an unwillingness to interfere with violent and destructive sides of civil society (cf. Ravndal & Bjørgo 2018). In addi-tion, CSOs may also choose to be passive due to a political agenda in which response to right-wing extremism is perceived to be inconsistent with their aims and mission. It is important to note, however, that such CSOs still have an indirect role in promoting democracy by bridging ties between people (Putnam 2000).

Protest at the upper-right embraces responses characterised by both high intolerance and political participation. The response includes active and expressive responses that aim to resist and counteract right-wing extrem-ism. This type of response is strongly valued in social movement literature. In the extreme forms, it includes responses that recognise the use of con-frontational tactics such as protests, riots, media campaigns, civil disobedi-ence and methods to resist, counteract or isolate such movements (Caiani et al. 2012; Della Porta & Diani 2015; Meyer & Tarrow 2018). Accordingly, it resembles the ‘militant strategy’ discussed by Capoccia (2005), be it viewed from the perspective of civil society. In its extreme forms, this includes rad-ical and violent responses.

Finally, dialogue at the lower-right acknowledges the civil and political rights of the extreme right but in contrast to protest, it embraces responses described as being essential in the deliberative model of democracy. This response emphasises the importance of tolerance, inclusion and public dis-cussions in civil society (Habermas & Benhabib 1996). It includes responses from civil society that seek both to alter the political debate, political deci-sions or public attitudes as well as to listen and include right-wing extrem-ists in dialogue while also keeping track of the compatibility of arguments and policies with the core values of liberty and equality (Rummens & Abts 2010).

It should be noted that the typology does not encapsulate all possible responses, strategies or methods used by more ‘pro-democratic civil society’ in relation to extremist movements. Instead, it defines four theoretically dis-tinct forms of responses. Empirically, CSO responses are unlikely to fit per-fectly with each end of the typology as CSOs can combine and use multiple responses. In the following section, this typology is applied in order to anal-yse how locally based CSOs in the town of Ludvika in Sweden responded to the Nordic Resistance Movement (NRM). First, however, I introduce the research design and case.

Research Design

The Case of Ludvika and the Nordic Resistance Movement

To explore how CSOs respond to right-wing extremism, this article draws on evidence from the town of Ludvika, which is located in the province of Dalarna (Eng. Dalecarlia) in Sweden. Sweden is often referred to as a country with an active and well-organised civil society, with civilians taking an active role in political life. Sweden is also described as having a politi-cal culture marked by deliberation and consensus, where politipoliti-cal conflicts are expected to be settled around the negotiation table, and where violent street protests and more contentious forms of politics are relatively rare (Trägårdh 2007; Wennerhag 2017; Jennstål et al. 2020). However, while crit-icism of public authorities is deeply rooted in the ‘culture of advocacy’ of civil society in Sweden (Arvidson et al. 2018), how organisations respond to violent and destructive elements within civil society is relatively unknown.

The municipality of Ludvika has approximately 27,000 inhabitants and is renowned for its high-tech industry, with the large corporation ABB a centre for power transmission. Although Dalarna is not considered as much a stronghold for extreme nationalistic parties as the Stockholm region, western Sweden and southern Sweden (Lööw 2015, 425), underground movements, such as the White Aryan Resistance (VAM) and the Swedish Resistance Movement, have maintained a presence in Ludvika and other Dalarna towns since the 1990s (Blomberg et al. 2018). At the time of the study, Ludvika was home to several leaders of the Swedish and Nordic branch of the NRM.

The NRM has its roots in the Swedish Nazi and the neo-Nazi movement of the 1980s and 1990s, and is the leading neo-Nazi movement within the Nordic countries (Ravndal 2018; Kølvraa 2019; Ranstorp et al. 2020). It has about 1,000 members and has been registered as a political party since 2015. Up until the 2018 election, the NRM held representation in the local assem-bly in Ludvika. At that time, Ludvika was one of three towns in Sweden

that the NRM chose to prioritise in terms of mobilising electoral support to maintain representation in the local government assembly. In 2018, the NRM campaigned intensively for continued political representation, but without success.

With thought to the intense activity of the leading neo-Nazi movement in the Nordic countries and the tradition of strong civil society operating in a political culture marked by deliberation and consensus, Ludvika forms an interesting case for an analysis of CSO responses to right-wing extremism. Qualitative and Quantitative Approach

This study builds on two complementary datasets, the first of which was generated by a digital survey directed at civil society leaders in 325 or-ganisations in Ludvika. The questionnaire was distributed in August and September 2018 prior to the Swedish election to all CSOs listed in the reg-ister of organisations within the municipality of Ludvika. The target sample (N = 325) includes organisations active in various social arenas: sports and hobby organisations; cultural organisations; informal help organisations; re-ligious organisations; and local unions. A chairperson (here referred to as ‘leaders’) from each organisation completed the questionnaire as its rep-resentative. The leaders were asked to respond as representatives of their organisations, and are thus a critical source of information on how local civil society relates to the NRM. The questionnaire included 27 questions about tolerance of and sentiment towards the NRM, about political participation and about a number of background issues such as the type of organisation the respondent represented.

The categorisation of organisation was based on the leaders’ responses. More specifically, the leaders selected a category from a list of 11 organ-isation types. The list corresponds to the one used in a renowned survey from the national Swedish SOM Institute (Society, Opinion and Media). However, two subgroups were added to take into account the specific types of organisation usually found at the local level, namely village com-munities (‘Byalag/bygdegårdsförening’) and organisations that operate in public parks and meeting places for various cultural activities and events (‘Folketshusförening’).2. To allow for statistical analyses, the 11 categories

were collapsed into five broader groups, namely cultural organisations (38); humanitarian and religious organisations (14); sports and hobby organisa-tions (42); political organisaorganisa-tions (16); and citizen groups composed mainly of associations for senior citizens (9).3. The response rate was 44 per cent.

All questions, except for the question on background issues, were multi-ple-choice. In total, civil society leaders from 119 organisations participated in the study. Responses that did not give the type of organisation were excluded from the statistical analyses.

Tolerance towards the NRM was measured in two ways. First, leaders were asked the straightforward question as to whether the NRM should be banned. Second, to allow for a more nuanced understanding of the tolerance of the intolerant, tolerance towards the NRM was measured according to the rejec-tion and acceptance component (see, for instance, Sullivan et al. 1979; Gibson 1992). In the first step, CSO leaders were asked to indicate the extent to which they perceive the NRM to be disturbing or offensive. In the second step, those who found the NRM to be disturbing or offensive were asked to indicate the extent to which they were willing to extend various rights or activities to repre-sentatives of the NRM.4. More specifically, the leaders were asked to indicate

the extent to which they would allow representatives of the NRM (1) to enjoy freedom of speech; (2) to hold public office in the Swedish parliament; and (3) to teach in schools. In addition, leaders were asked to indicate the extent to which they were willing (4) to have an NRM representative as a neighbour and (5) to have a personal relationship with an NRM representative. Political participation was measured by asking the leaders to indicate their level of political participation. (Have you been involved in political activity directed against the NRM [e.g., participated in manifestation or a demonstration, or written posts in social media on behalf of your organisation]?). Here it is important to note that the use of self-reported perceptions risks respondents overestimating their responses. In addition, the threshold for being involved in political activity is low as it involves being active on social media.

To allow for a thorough understanding of CSO responses, semi-struc-tured interviews were conducted with eight civil society leaders. Six of these representatives responded to the survey. However, the survey was anony-mous, and as such, it was not possible to crosscheck the results between the datasets. The interviewees were chosen according to a snowball sampling and had to meet three criteria. First, interviewees had to hold a position as chairperson, member of the board or similar within the organisation. Second, interviewees had to take part in political activities directed against the NRM prior to the 2018 Swedish election [autumn 2017 to autumn 2018]. Third, the interviewees had to be from various types of organisation. The selected interviewees were active in religious organisations (3); humani-tarian organisations (1); cultural organisations (2); and political organisa-tions (2). Having the position as leading representatives in organisaorganisa-tions who have taken an active role vis-à-vis the NRM prior to the 2018 Swedish election, these representatives were capable of providing detailed informa-tion about responses towards the NRM in Ludvika. Thus, representatives were selected based on their relevance to the research questions rather than the fact they were representatives of a larger population – what Bryman (2016) calls a ‘purposive sample’. However, the sample is not representative nor all-encompassing, and this is important to take into consideration when interpreting the results.

The interviews were conducted between August 2018 and February 2019; lasted between 60 and 90 minutes; and were recorded and transcribed. They consisted of open-ended ‘grand tour questions’ and ‘specific grand tour questions’ (Leech 2002; Spradley 2016) covering attitudes towards the NRM and political participation (e.g., ‘What comes to mind when the NRM is brought up?’; ‘What responses have you and the organisation you repre-sent been a part of and why?’; ‘How would you describe the responses from local civil society in general?’).5. The interview material was coded

accord-ing to relevant recurrent thematic elements of the stories told (thematic analysis as in Bryman 2016).6. Finally, reports in Swedish newspapers [from

autumn 2014 to autumn 2018] were used to complement and confirm the results in the survey and interviews.

It is important to keep in mind that the survey may not fully represent the position of CSOs in Ludvika. Only CSOs that themselves have chosen to be included in the municipal register were included in the survey. As such, it may not include all organisations in Ludvika. Active CSOs recognised by the municipality may be overrepresented in the sample. Furthermore, the results draw on opinions and experiences of leaders and are thus not valid for all members. At the same time, the register is rather extensive for a municipality, with about 27,000 inhabitants, and includes a broad range of CSOs. However, as representatives of their organisations, leaders have con-siderable information about and influence on the activities of the organisa-tion, and are thus a critical source of information on how local civil society relates to the NRM. Finally, it is important to observe that data collection took place during the general election, which may lead to more intense responses than during other less politically charged situations.

Results

Drawing primarily on evidence from civil society leaders, this section will ex-plore the responses of CSOs to the NRM prior to the election in September 2018 and will do so in three steps. First I will present the results from the survey locating CSO responses along the two axes, tolerance-intolerance and active-passive participation. Thereafter, I draw attention to the results from the interviews that describe the political activities directed against the NRM and at the same time that explore the potential differences between types of CSOs. Finally, I summarise the results.

Quantitative Results

During the election campaign, a recurring question in the public debate re-volved around questions on whether the NRM should be allowed to hold demonstrations, run political campaigns and enjoy freedom of speech. To

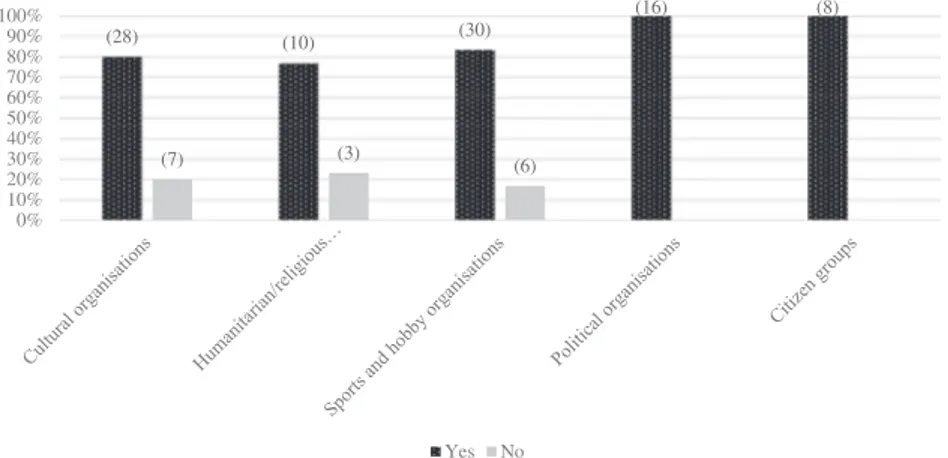

explore the extent to which and the way in which civil society tends to toler-ate the NRM, CSO leaders were first asked if the NRM should be banned. Results show that 85 per cent (96 out of 113) of the leaders in CSOs who responded to the survey agreed that the NRM should be banned, while 15 per cent (17 out of 113) did not. With focus on the differences between type of CSO, Figure 2 shows that all leaders in political organisations and citizen groups stated that the NRM should be banned, while 80 per cent (28 out of 35) of leaders in cultural organisations and 83 percent (30 out of 36) in sports and hobby organisations were of the same sentiment. Seventy-seven per cent (10 out of 13) of leaders in humanitarian and religious organisa-tions agreed that the NRM should be banned, meaning that 13 per cent (3 out of 13) did not. Seen together, these results indicate that tolerance is relatively lower among political organisations and citizen groups compared to other types of organisations.

Turning to the double-barrelled way of measuring tolerance, CSO lead-ers were first asked to indicate the extent to which they perceive the NRM to be disturbing or offensive. The results of the survey show that 93 per cent (125 out of 135) perceived the NRM to be disturbing or offensive. This clearly indicates that civil society leaders reject the NRM, perceiving the movement to be problematic, unacceptable or intolerable. Respondents who found the NRM disturbing or offensive were asked to respond to five questions that indicated the acceptance component of tolerance, that is, the extent to which they were willing to extend various rights or activities to representatives of the NRM. Results show that 33 per cent (38 out of 115) would be willing to grant freedom of speech to representatives of the NRM, while 67 per cent (77 out of 115) would not. Corresponding figures

Figure 2. Differences between Types of CSOs on the Question of Whether the NRM Should be Banned (Per cent, Numbers in Brackets, N = 108).

(28) (10) (30) (16) (8) (7) (3) (6) 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% Yes No

for allowing representatives to hold a position in public office are 17 and 82 per cent respectively. Furthermore, 13 per cent (15 out of 114) would allow NRM representatives to teach in schools. Eighty-six per cent (99 out of 115) would not. Furthermore, 34 per cent (39 out of 114) would be willing to have representatives of the NRM as their neighbour, but 66 per cent (75 out of 114) would not. A majority of the leaders, 89 per cent, were unable to conceive of a personal relationship with an NRM representative (Figure 3).

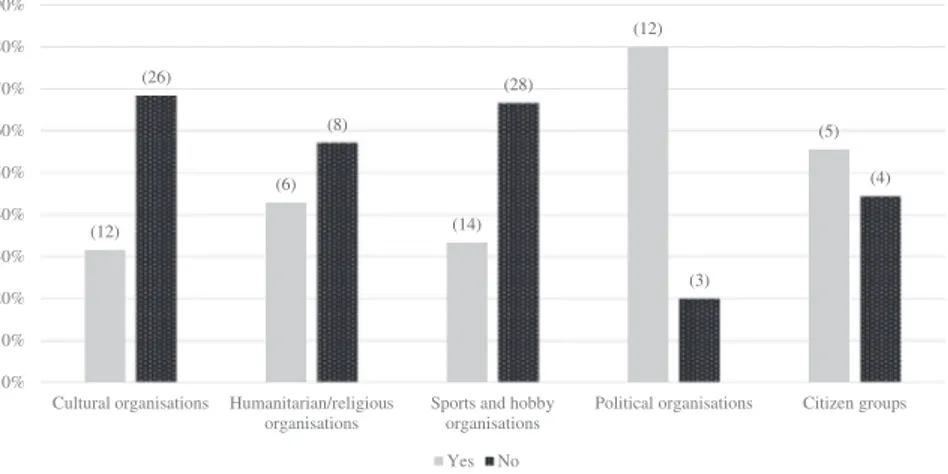

Having presented the results on the tolerance of the intolerant, we now turn to the extent to which leaders of CSOs actively demonstrated their intolerance of the NRM. Leaders were asked to indicate the extent to which they were involved in political activity in response to the NRM, such as manifestation, demonstration or posts on social media. Results show that 41 per cent (52 out of 126) of the leaders were involved in political activities, while about 58 per cent (74 out of 126) declared no political participation.

A look at the results by type of CSO (Figure 4) shows that a majority of the leaders in political organisations and citizen groups were involved in political activities such as participating in manifestations or demonstrations, or writing posts on social media: more precisely, 80 percent (12 out of 15) of the leaders in political organisations and 56 per cent (5 out of 9) of citizen groups. Among the other types of organisations, the results are the oppo-site, where a majority of the leaders were not involved in political activities. Forty-three per cent (6 out of 14) of the leaders in humanitarian/religious organisations were involved in political activities directed against the NRM.

Figure 3. Civil Society Leaders’ Tolerance of the NRM According to Different Dimensions of Tolerance (Per cent, Numbers in Brackets, N = 115).

38 20 15 39 12 77 94 99 75 102 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% Freedom of

expression Representative Teacher Neighbour Personal relationship Tolerance Intolerance

Corresponding figures for cultural organisations and sports and hobby organisations are 32 per cent (12 out of 38) and 33 per cent (14 out of 42) respectively. Taken together, this indicates that political organisations and citizen groups were more politically active when it came to participating in activities directed at the NRM compared to the other types of organisations.

To explore further responses between different types of CSOs, the two dimensions of tolerance- intolerance and active-passive participation are combined. The result is somewhat mixed but is in line with previous find-ings indicating that leaders from political organisations and citizen groups are among the more intolerant and active CSOs, as shown in Figure 5. The pattern varies more among the other types of organisation. Leaders from cultural organisations and sports and hobby organisations stand out as being the most intolerant and passive. However, it is important not to draw far-reaching conclusions, as the absolute number of cases in each category is very few. Ideally, one would like to use various measures that capture CSO responses along the two dimensions and the spatial aspects of the theoreti-cal typology. At the same time, the measures applied here have the benefit of focusing on critical aspects of CSO responses, namely whether there was participation and whether right-wing extremist movements should be per-mitted. In the subsequent section, CSO responses are explored further using the qualitative empirical material.

Figure 4. Involvement of Civil Society Leaders in Political Activities Directed at the NRM by Type of CSO (Per cent, Numbers in Brackets, N = 118).

Note: The tolerance-intolerance dimension was based on the question as to whether or not the NRM should be banned. The dimension referring to active-passive participation was based on the item measuring the involvement of CSOs in political activities directed at the NRM.

(12) (6) (14) (12) (5) (26) (8) (28) (3) (4) 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90%

Cultural organisations Humanitarian/religious

organisations Sports and hobbyorganisations Political organisations Citizen groups

Qualitative Results

Turning to the qualitative results, all interviewees referred to the NRM as ‘provocative’, ‘hostile’ or ‘threatening’. In addition, several interviewees ar-gued that the presence of the NRM had created a sense of insecurity and concern, particularly in conjunction with the NRM election campaign, a time when the movement was very active. An interviewee representing a cultural organisation stated:

You are constantly reminded of them [the NRM]. They organise various activities, they are present downtown. They are so obvious. They put advertisements in the mailbox and currently their behaviour is very intense, very intense. They are in town almost every day, and visible in one way or another. They do their ‘walk for security’ but instead of creating security, which is what they want to achieve, they cause anxiety and concern. There is a fear within the population.

Figure 5. The Responses of Civil Society Leaders to the NRM in Terms of Tolerance– Intolerance and Passive–Active Participation (Per cent, Numbers in Brackets, N = 115).

Note: The tolerance-intolerance dimension was based on the question as to whether or not the NRM should be banned. The dimension referring to active-passive participation was based on the item measuring the involvement of CSOs in political activities directed at the NRM.

(6) (2) (4) (1) (1) (1) (2) (19) (6) (22) (3) (3) (11) (5) (12) (12) (5) 0.0% 5.0% 10.0% 15.0% 20.0% 25.0%

A couple of interviewees were also sceptical about granting freedom of speech to the NRM as this, they felt, would compromise democracy. A strik-ing feature of the interviewees’ stories was the difference in how they re-lated to the representatives of the NRM in terms of the fundamental query of tolerance of the intolerant. One representative from a political organisa-tion explained:

I think it is questionable whether the NRM should be allowed to exist. Should an organisa-tion whose goal it is to suppress democracy be permitted to demonstrate and run for office? I am very doubtful. When speaking to other people, I see that I am not alone. After all, our society is based on democratic values, and the NRM state clearly that they do not want de-mocracy. So, should they be allowed to spread their messages of hate? I do not think so; it is against our society’s conviction when it comes to the value of democracy.

In contrast, one interviewee representing a religious organisation claimed that freedom of expression is ‘unconditional’ and a ‘universal democratic right’ that must also apply to the NRM unless it is likely to cause imminent violence and harassment. Referring to the polarised political climate, he ar-gued that dialogue with contending parties such as the NRM is needed: ‘It is how democracy works’.

The reluctance among many of the leaders to allow representatives to hold public office or to teach in schools is another theme in the interviews. In May 2018, the NRM attempted to recruit members at the upper-secondary school in Ludvika, which led to coverage in Sweden’s leading national news-paper. One interviewee perceived this as being a ‘turning point’ in how local civil society related to the NRM. From perceiving the NRM to be relatively harmless, the national media debate encouraged a more negative opinion of the NRM as being an unwelcome and threatening element within the local community. This may explain the very low tolerance towards allowing representatives of the NRM to teach in schools.

At the same time, two interviewees described how it was difficult to avoid the NRM in such a small community as Ludvika and therefore they had no choice but to tolerate them. One leader representing a cultural organisation stated: ‘I talk to their kids and I have children in the same daycare. So I am forced to be tolerant’. Another interviewee representing a humanitarian/ religious organisation expressed this more directly:

Intolerance must be allowed, but we must also realise that we are all human beings. We need to look at each other while trying to see the good in the other person. It is often the case that when you take a step closer, you see that they [members of the NRM] are also humans. Although people are capable of the most brutal things, which is frightening, it is also important that we do not distance ourselves [from members of the NRM]. Otherwise, we cannot live together.

The qualitative interviews also provide in-depth insight into CSO re-sponses to the NRM prior to the 2018 election. First, all interviewees strongly dismissed the use of violence as a response to the movement. This is apparent from the survey results, where ninety-four per cent (116 out of 124) dismissed the use of violence as a response to the NRM and 47 per cent (59 out of 125) dismissed the use of civil disobedience. Furthermore, there were few reports of violent conflicts or demonstrations vis-à-vis the NRM. Instead, local civil society reacted to the NRM primarily by (1) promoting the importance of democracy, human rights and tolerance; (2) encouraging dialogue with citizens of Ludvika; and (3) trying to limit the prominence of the NRM in the public arena.

Several interviewees referred to the manifestation ‘love is greater than everything’, where leading actors from civil society, along with national pol-iticians, took part in a joint march through the town of Ludvika to advocate the importance of equal values and human rights. The manifestation was organised by humanitarian and religious organisations such as the Church of Sweden, Save the Children, the Red Cross, Ria All Humans, the study organisation SENSUS and local religious organisations with the aim to ‘cre-ate meeting places’, ‘maintain a public presence in the public arena’ and ‘be a counterforce in society’. One respondent from a humanitarian organisa-tion explained:

It [the manifestation] is to create meeting places and to show that we [the organisation] come forward when needed and talk to people. It sounds very pretentious, but to be a coun-terforce in some way – to show that there is a councoun-terforce in society and to show that we stand opposed to the NRM.

There are similar examples from Britain of Christian churches taking a clear stand against right-wing extremism (Eatwell 2010, 225). In addition, Sanchez Salgado (2020) shows that human rights and humanitarian CSOs operating in the European context have over time come to use strategies that appeal to the emotions to make human rights more popular and chal-lenge increasing populism.

Another example from Ludvika in terms of responses to the NRM was the initiative ‘Medmänniska i valtider’ (Fellowship During Elections, my translation), which was headed by the Church of Sweden: several interview-ees and their associated organisations assembled in the town during the 2018 election campaign to meet citizens and to deliberate the importance of humanity and democratic values. Similar responses aimed at raising the awareness of right-wing extremist movements and at discouraging socie-tal actors and citizens from engaging in violence have been reported by Michael (2003, 173) and Scrivens and Perry (2017, 539, 548). In addition, the findings from Ludvika tally well with the study by Pedahzur (2003, 71) on

the response of CSOs to right-wing extremism in Brandenburg in Germany, where CSOs responded by educating and strengthening citizens’ demo-cratic values, and organising community activities intended to strengthen democracy.

Another interviewee representing the political organisation and anti-Nazi group ‘Clowns against anti-Nazism’ described how she/he and other group members dressed up as clowns in conjunction with the actions/campaigns of the NRM. This occurred on a number of occasions during this period to demonstrate the political illegitimacy of the NRM. Another response of the organisations was to restrict the attendance of the NRM in public arenas by removing posters and advertisements that it had distributed.

We always spray over their logo and replace it with a heart. Especially in Dalarna, it takes so long for the [municipal council] to clean up. Therefore, we always make a little heart so you can’t see their message. Even if this is illegal, it doesn’t cost more to clean up an extra layer of paint because it is in the same place. So we use civil disobedience and I believe that it can be used to protect democracy.

Similar findings have been reported in the USA, where CSOs excluded extremists’ views from ‘the market place of ideas’ as well as in the media (Michael 2003, 171). According to the interviewee representing ‘Clowns against Nazism’, the removal of posters and advertisements distributed by the movement also serves to open up for discussion with the residents of Ludvika.

Removing their propaganda is important, as it is a cornerstone of their organisation. They always work at night. We always work during the day because we want to show people that this is not ok, it is offensive. Many people stop and wonder what we are doing, and that’s when we get an opportunity to talk to the public about the NRM and explain what we are doing and why […]. So while doing what we do, we also get the opportunity to share knowledge.

An interviewee representing a religious organisation also addressed the importance of promoting public debate. During the 2018 election campaign, a religious organisation chose to invite all political parties represented in the local parliament to a public dialogue about their perceptions on hu-manity and diaconia. The purpose was to deliberate on matters of huhu-manity and everyone’s equal value to make the political stances of the parties more visible to the residents of Ludvika. The existence of the NRM was the clear impetus for holding the event. However, the organisation decided to call it off as a result of severe criticism in national media.

One of only a few examples of more oppositional activity is when ‘Clowns against Nazism’ published the names of NRM members on their homepage and dumped cow manure in front of the stage where the NRM

were supposed to hold a public speech. In addition, a couple of interviewees provided examples of more subtle responses or silent protests. One inter-viewee representing a cultural organisation described how she, on behalf of the local organisation, encouraged citizens to return flyers distributed by the NRM prior to the election. In addition, other interviewees explained how they had encouraged residents of Ludvika to eat at a local restaurant after members of the NRM threatened its owner.

Summary

Taken together, the results indicate that CSOs are intolerant of the NRM. Leaders in CSOs express some tolerance of the NRM in their immediate environment and of the movement’s right to express its views publicly and to nominate candidates to political assemblies. However, when it comes to personal relationships, and to teaching young people and our children in school, tolerance is very low. Overall, it seems that the closer the NRM gets, the lower the tolerance becomes. Political organisations and citizen groups appear most intolerant, while humanitarian and religious organisations, sports and hobby organisations and cultural organisations are somewhat more tolerant, at least when viewed from the perspective of leading rep-resentatives within the CSOs. Furthermore, results reveal that a majority of the leaders in civil society have taken a public stand against the NRM, while a minority have participated in political activities against the NRM. Responses have primarily come about by means of promoting the impor-tance of democracy and human rights; encouraging dialogue with citizens about the NRM; and limiting the visibility of the movement in the public sphere. Thus, the responses that existed prior to the 2018 election tended to be more oriented towards promoting dialogue and the importance of public discussions in civil society. Confrontational tactics, such as protests, riots and civil disobedience, are less evident. Finally, the results indicate that political organisations and citizen groups tend to be more active in terms of involvement in political activities directed at the NRM. However, humani-tarian and religious organisations and political organisations appear to take a leading role when it comes to organising and mobilising events directed against the NRM.

Conclusion and Discussion

The aim of this article has been to expand the understanding of the role CSOs play in counteracting political extremism. I posed two overarching research questions: Do CSOs respond with tolerance or intolerance, and do they do so actively or passively? To what extent and how do the responses differ between different types of CSOs. The questions has been answered

in two stages. First, I introduced a new theoretical typology for classifying CSO responses towards right-wing extremism. The typology developed here has a number of advantages compared to the three principal types of civil society (I, II and III) used to understand the role of CSOs vis-à-vis political extremism (e.g., Foley & Edwards 1996; Booth & Richards 1998; Pedahzur 2004). It takes into account the important distinction between tolerance and intolerance on the one hand, and between active and passive political par-ticipation on the other. What is more, it allows for a more fine-tuned anal-ysis of a variety of CSO responses vis-à-vis extreme right-wing movements. This distinction is important as it allows for a better understanding of the democratic role of civil society in general and the responses of pro-demo-cratic civil society in particular, a query that has had relatively limited atten-tion in the literature.

Second, using the proposed typology, I have provided empirical insights on how locally based CSOs in the town of Ludvika in Sweden responded to the leading neo-Nazi movement in the Nordic countries, the Nordic Resistance Movement (NRM), prior to the 2018 Swedish election. Drawing on the perspectives of leading representatives, results show that CSOs are generally intolerant of the NRM and have engaged in opposition to the movement. Restricted tolerance along with relatively widespread political participation indicates a preparedness and ability within civil society to stand up to defiant elements of the extreme right. Rather than nurturing or upholding right-wing radicalisation, civil society appears to operate as a bulwark or counter force (see also Meyer & Tarrow 2018; Roth 2018; Siim et al. 2019) against right-wing extremism, at least during politically charged situations. The results are in line with the general argument by Putnam (1993) and de Tocqueville (2000) – that being that civil society contributes to democratic life as well as the concept of a ‘pro-democratic’ civil society (Pedahzur 2003).

The typology introduced and applied in this article has disentangled var-ious forms of responses. Notably, dialogue and deliberation rather than pro-test and contention characterise the responses. CSOs responded primarily by means of promoting the importance of democracy and human rights; encouraging dialogue with citizens about the NRM; and limiting the visibil-ity of the movement in the public sphere. As such, the response resembles ideals described as being essential in the deliberative model of democracy, emphasising the importance of tolerance, inclusion and public discussions in civil society. The reasoning behind the types of responses varies. One inter-pretation is that it can be understood from the context of the Swedish politi-cal culture, which is characterised by deliberation and consensus, and where the use of violent street protests and more contentious forms of politics is relatively rare (Trägårdh 2007; Wennerhag 2017; Jennstål et al. 2020). At the same time, the findings from Ludvika tally well with the study by Pedahzur

(2003, 71) on how CSOs responded to right-wing extremism in Brandenburg in Germany: there, CSOs responded by educating and strengthening citi-zens’ democratic values, and by organising community activities intended to strengthen democracy. Another interpretation is that the emphasis on pro-moting dialogue and public discussion is due to the fear of reprisal and an unwillingness to interfere with violent and destructive sides of civil society. Simply put, CSOs may deliberately choose less oppositional tactics in order not to trigger violent repercussions from the NRM.

A final important result of the study presented in this article is that CSOs differ in their responses to right-wing extremism. Political organisations and citizen groups appear to be the most intolerant and slightly more active type of organisation, while cultural organisations and sports and hobby organi-sations figured slightly more frequently among the intolerant and passive organisations. However, humanitarian and religious organisations demon-strated more multifaceted responses and appear to have taken on a greater role in mobilising joint initiatives in the public sphere, fostering public delib-eration and promoting democratic norms. The different responses raise the question as to whether or not CSOs that are driven by a political agenda take on a more repressive stance towards right-wing extremism in line with the substantive view of democracy compared with socially oriented organ-isations that combine dialogue and containment strategies along with what Rummens and Abts (2010) refer to as a concentric view of democracy. An interesting future study would be to investigate the extent to which, the time at which and the reason for which such responses emerge in civil society and the ways in which various types of CSOs act against right-wing extremism. Here it may be worth taking a comparative approach in order to explore further the conditions under which responses to political extremism at the local level emerge and develop before eventually waning.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This article benefited from comments made by scholars at The European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR) Virtual General conference, 24–28 August 2020 and the Annual Conference of the Swedish Political Science Association (SWEPSA) 2–4 October 2019. I would also thank to the anonymous reviewers for their remarks and constructive and helpful comments.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares no conflicting interest.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This project was funded by the municipality of Ludvika.

NOTES

1. However, Kocka (2006, 40–1) refers to civil society as a specific social action that (among other criteria) operates non-violently. This suggest that violent organisations,

such as right wing extremist movements are not included in the sphere referred to as ‘civil society’. I thank the reviewer for this remark.

2. The leaders could choose from the following types of organisations: village community; ‘Folketshusförening’; hobby organisation; sports and leisure organisation; environmen-tal organisation; labour organisation; political party/association; cultural organisation; association for senior citizens; humanitarian organisation; the Church of Sweden or other religious organisation; other type of organisation.

3. Each category included the following types of organisations (numbers in brackets): tural organisation included village community (21) and Folketshusförening (6) and cul-tural organisation (11). The category humanitarian and religious organisation included humanitarian organisations (10) and the Church of Sweden or other religious organisa-tion (4). Sports and hobby organisaorganisa-tions included hobby organisaorganisa-tions (22), and sports and leisure organisations (20). Political organisation included environmental organi-sations (6), labour organiorgani-sations (3) and political party/association (7). Finally, citizen groups included associations for senior citizens (6) and other types of organisations (3). 4. In this article, tolerance is interpreted as being the willingness to ‘put up with’ others

who are different from oneself. This is the definition used in this article and implies that tolerance is a reaction to something that the individual perceives as difficult or problematic, such as ideas, opinions and people of certain groups, and their fundamental values and behaviours. Thus, tolerance includes an element of rejection and an element of acceptance (Scanlon 2003; Forst 2013). What this means is that an individual, to be tolerant, first rejects or takes notice of what he or she perceives as problematic, unac-ceptable or intolerable, only then to accept, tolerate or perhaps even welcome the same. 5. The benefit of using these types of questions was that it allowed for a general overview of the type of responses that came about in Ludvika at the time of the election. It also provided an insight into the sentiments of leading representatives vis-à-vis the NRM. A specific grand tour question enabled a more detailed focus on a topic, for example the type of responses used by the organisation (cf. Leech 2002).

6. Ethical considerations have been taken into account using the Swedish Research Council’s Codex (www.vr.se) and the recommendations from the AoIR Ethics Working Committee on Ethics and Internet Research (Markham & Buchanan 2012).

REFERENCES

Ackerman, G. & Peterson, H. 2020. ‘Terrorism and COVID-19: Actual and Potential Impacts’,

Perspectives on Terrorism, 14(3), 59–73.

Art, D. 2007. ‘Reacting to the Radical Right: Lessons from Germany and Austria’, Party Politics,

13(3), 331–349.

Arvidson, M., Johansson, H., Meeuwisse, A. & Scaramuzzino, R. 2018. ‘A Swedish Culture of Advocacy? Civil Society Organisations’ Strategies for Political Influence’, Sociologisk

forsk-ning, 55(2–3), 341–364.

Berman, S. 1997. ‘Civil Society and the Collapse of the Weimar Republic’, World Politics, 49(3), 401–429.

Blomberg, H., Båtefalk, L. & Stier, J. 2018. Extremistisk ideologi i den retoriska kampen om

sanningen: fallet Nordiska motståndsrörelsen på sociala medier och i lokalpress. [Extremist Ideology in the Rhetorical Struggle for Truth: The Case of the Nordic Resistance Movement on Social Media and in Local Press]. Rapport: 5 i skriftserien Interkulturellt utvecklingscen-trum Dalarna (IKUD). Falun: Högskolan Dalarna.

Booth, J.A. & Richard, P.B. 1998. Civil Society, Political Capital, and Democratization in Central America. The Journal of Politics, 60(3), 780–800.

Bryman, A. 2016. Social Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Caiani, M., Della Porta, D. & Wagemann, C. 2012. Mobilizing on the Extreme Right: Germany,

Italy, and the United States. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Capoccia, G. 2005. Defending Democracy: Reactions to Extremism in Interwar Europe. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press.

Chambers, S. & Kopstein, J. 2001. ‘Bad Civil Society’, Political Theory, 29(6), 837–865. Cohen, J. & Arato, A. 1992. Civil Society and Political Theory. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

de Tocqueville, A. 2000. Democracy in America. The Complete and Unabridged Volumes I and

II. New York: Bantam Dell.

Della Porta, D. & Diani, M. 2015. The Oxford Handbook of Social Movements. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Downs, W. M. 2012.Political Extremism in Democracies: Combating Intolerance. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Eatwell, R. 2010. ‘Responses to the Extreme Right in Britain’, in Eatwell, R. & Goodwin, M. J., eds, The New Extremism in 21st Century Britain. London: Routledge. 211–230.

Edwards, M. 2014. Civil Society. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Eubank, W. L. & Weinberg, L. B. 1997. ‘Terrorism and Democracy Within one Country: The case of Italy’, Terrorism and Political Violence, 9(1), 98–108.

Fallend, F. & Heinisch, R. 2016. ‘Collaboration as Successful Strategy against Right-Wing Populism? The Case of the Centre-Right Coalition in Austria, 2000–2007’, Democratization,

23(2), 324–344.

Foley, M. W. & Edwards, B. 1996. ‘The Paradox of Civil Society’, Journal of Democracy, 7(3), 38–52.

Forst, R. 2013. Toleration in Conflict: Past and Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Gibson, J. L. 1992. ‘Alternative Measures of Political Tolerance: Must Tolerance be

“Least-Liked”?’, American Journal of Political Science, 36(2), 560–577.

Gibson, J. L. 2006. ‘Enigmas of Intolerance: Fifty Years after Stouffer’s Communism, Conformity, and Civil Liberties’, Perspectives on Politics, 4(1), 21–34.

Goodwin, J. & Jasper, J. M. 1999. ‘Caught in a Winding, Snarling Vine: The Structural Bias of Political Process Theory’, Sociological Forum, 14(1), 27–54.

Habermas, J. & Benhabib, S. 1996. ‘Three Normative Models of Democracy: Liberal, Republican, Procedural’, in Kearney, R. & Dooley, M. eds., Questioning Ethics. Contemporary Debates in

Philosophy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 21–30.

Jämte, J. 2018. ‘Radical Anti-Fascism in Scandinavia: Shifting Frames in Relation to the Transformation of the Far Right’, in Wennerhag, M., Fröhlich, C. & Piotrowski, G., eds,

Radical Left Movements in Europe. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 248–267.

Jenne, E. K. & Mudde, C. 2012. ‘Can Outsiders Help?’, Journal of Democracy, 23(3), 147–155. Jennstål, J., Uba, K. & Öberg, P. 2020. ‘Deliberative Civic Culture: Assessing the Prevalence of

Deliberative Conversational Norms’, Political Studies. Online March 30 2020.

Kaltwasser, C. R. & Taggart, P. 2016. ‘Dealing with Populists in Government: A Framework for Analysis’, Democratization, 23(2), 201–220.

Kocka, J. 2006. ‘Civil Society in Historical Perspective’, in Kean, J., ed, Civil Society Berlin

Perspectives. New York: Berghahn Books, 37–51.

Kølvraa, C. 2019. ‘Embodying ‘the Nordic race’: Imaginaries of Viking heritage in the Online Communications of the Nordic Resistance Movement’, Patterns of Prejudice, 53(3), 270–84. Kopecky, P. & Mudde, C. 2003. Uncivil Society? Contentious Politics in Post-Communist Europe.

London: Routledge.

Kriesi, H. 1996. ‘The Organizational Structure of New Social Movements in a Political Context’, in McAdam, D., McCarthy, J. D. & Zald, M. N., eds, Comparative Perspectives on Social

Movements. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 152–184.

Kwon, H. K. 2004. ‘Associations, Civic Norms, and Democracy: Revisiting the Italian Case’,

Theory and Society, 33(2), 135–166.

Leech, B. L. 2002. ‘Asking Questions: Techniques for Semistructured Interviews’, PS: Political

Science and Politics, 35(4), 665–668.

Lööw, H. 2015. Nazismen i Sverige 2000–2014 [Nazism in Sweden 2000–2014]. Stockholm: Ordfront.

Malkki, L., Fridlund, M. & Sallamaa, D. 2018. ‘Terrorism and Political Violence in the Nordic Countries’, Terrorism and Political Violence, 30(5), 761–71.

Malkopoulou, A. & Norman, L. 2018. ‘Three Models of Democratic Self-Defence: Militant Democracy and its Alternatives’, Political Studies, 66(2), 442–458.

Markham, A. & Buchanan, E. 2012. Ethical Decision-Making and Internet Research: Version

2.0. Recommendations from the AoIR Ethics Working Committee.

Meyer, D. S. & Tarrow, S. 2018. The Resistance: The Dawn of the Anti-Trump Opposition

Michael, G. 2003. Confronting Right-Wing Extremism and Terrorism in the USA. London: Routledge.

Minkenberg, M. 2006. ‘Repression and Reaction: Militant Democracy and the Radical Right in Germany and France’, Patterns of Prejudice, 40(1), 25–44.

Molnár, V. 2016. ‘Civil Society, Radicalism and the Rediscovery of Mythic Nationalism’, Nations

and Nationalism, 22(1), 165–185.

Mudde, C. 2017. The Populist Radical Right: A Reader. London: Routledge.

Pedahzur, A. 2002. The Israeli Response to Jewish Extremism and Violence. Defending

Democracy. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Pedahzur, A. 2003. ‘The Potential Role of “Pro-Democratic Civil Society” in Responding to Extreme Right-Wing Challenges: The Case of Brandenburg’, Contemporary Politics, 9(1), 63–74. Pedahzur, A. 2004. ‘The Defending Democracy and the Extreme Right: A Comparative

Analysis’’, in Eatwell, R. & Mudde, C., eds, Democracy and the New Extreme Right Challenge. London: Routledge, 108–133.

Popper, K. 1945. The Open Society and its Enemies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Portes, A. & Landolt, P. 2000. Social Capital: Promise and Pitfalls of its Role in Development.

Journal of Latin American Studies, 32(2), 529–547.

Putnam, R. D. 1993. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Putnam, R. D. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Ranstorp, M., Ahlin, F. & Nordmark, M. 2020. ‘Nordiska motståndsrörelsen – den samlade kraften inom den nationalsocialistiska miljön i Norden’, in Ranstorp, M. & Ahlin, F., eds,

Från Nordiska motståndsrörelsen till alternativhögern Centrum för asymmetriska hot – och terrorismstudier. Stockholm: Försvarshögskolan, 146–238.

Ravndal, J. A. 2018. ‘Right-Wing Terrorism and Militancy in the Nordic Countries: A Comparative Case Study’, Terrorism and Political Violence, 30(5), 772–792.

Ravndal, J. A. & Bjørgo, T. 2018. ‘Investigating Terrorism from the Extreme Right: A Review of Past and Present Research’, Perspectives on Terrorism, 12(6), 5–22.

Roth, S. 2018. ‘Introduction: Contemporary Counter-Movements in the Age of Brexit and Trump’, Sociological Research Online, 23(2), 496–506.

Rummens, S. & Abts, K. 2010. ‘Defending Democracy: The Concentric Containment of Political Extremism’, Political Studies, 58(4), 649–665.

Rydgren, J. 2009. ‘Social Isolation? Social Capital and Radical Right-Wing Voting in Western Europe’, Journal of Civil Society, 5(2), 129–50.

Rydgren, J. 2011. ‘A Legacy of “Uncivicness”? Social Capital and Radical Right-Wing Populist Voting in Eastern Europe’, Acta Politica, 46(2), 132–57.

Sanchez Salgado, R. 2020. ‘Emotion Strategies of EU-based Human Rights and Humanitarian Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) in Times of Populism’, European Politics and Society, 1–17. Scanlon, T. M. 2003. The Difficulty of Tolerance: Essays in Political Philosophy. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Scrivens, R. & Perry, B. 2017. ‘Resisting the Right: Countering Right-Wing Extremism in Canada’, Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 59(4), 534–558.

Siim, B., Saarinen, A. & Krasteva, A. 2019. ‘Citizens’ Activism and Solidarity Movements in Contemporary Europe: Contending with Populism’, in Siim, B., Krasteva, A. & Saarinen, A., eds, Citizens’ Activism and Solidarity Movements. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 1–24. Spradley, J. P. 2016. The Ethnographic Interview. Long Growe: Waveland Press.

Sullivan, J. L., Piereson, J. & Marcus, G. E. 1979. ‘An Alternative Conceptualization of Political Tolerance: Illusory Increases 1950s–1970s’, The American Political Science Review, 781–194. Trägårdh, L. 2007. State and Civil Society in Northern Europe: the Swedish Model Reconsidered

(Vol. 3). New York: Berghahn books.

Warren, M. E. 2001. Democracy and Association. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Wennerhag, M. 2017. Patterns of Protest Participation are Changing. Sociologisk forskning,

54(4), 347–351.

Widfeldt, A. 2004. ‘The Diversified Approach: Swedish Responses to the Extreme Right’, in Eatwell, R. & Mudde, C., eds, Western Democracies and the New Extreme Right Challenge. London: Routledge, 168–189.

APPENDIX

SURVEY QUESTIONS AND OPERATIONALISATION OF VARIABLES

Tolerance

Tolerance is measured in two steps following its rejection and acceptance compo-nents (Sullivan et al. 1979; Gibson 1992). First, the respondent is asked to indicate the extent to which he/she perceives the NRM to be disturbing or offensive. ‘To what extent do you perceive the Nordic Resistance Movement (NRM) to be disturbing or offensive?’ Reponses were recorded on a scale from 1–5: ‘to a great extent’, ‘to some extent’, ‘not particularly’, ‘not at all’ and ‘not familiar with the organisation’.

In the second step, the respondents who found NRM to be disturbing or offensive were asked to indicate to what extent they were willing to extend various rights or activities to representatives of the NRM. (‘To what extent do you agree with the following statements about the NRM?’)

• ‘People from this organisation/movement should be allowed to express their opinion publicly’

• ‘People from this organisation/movement should be allowed to hold public office in the Swedish parliament’

• ‘People from this organisation/movement should be allowed to work as teachers in schools’

• ‘I would be accepting of people from this organisation/movement living in my residential area’

• ‘I can imagine having a personal relationship with a person from this organisation/movement’

Responses were recorded on a scale from 1–4: ‘Agree fully’, ‘Agree partly’, ‘Agree to a lesser extent’, ‘Do not agree’. Alternatives 1 and 2 were collapsed into one category indicating tolerance, and alternatives 3 and 4 were collapsed into another indicating intolerance.

Political Participation

• ‘Have you been involved in political activity directed against the NRM [for example, participated in manifestations or demonstrations, or written posts in social media on behalf of your organisation]?’ Responses were recorded on a scale from 1–3: ‘Yes, several times’, ‘Yes, once’, ‘No’.