Corporate Accelerators

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Strategic Entrepreneurship and Digital Business AUTHOR: Simon Hagedorn and Robin Thien

TUTOR:Matthias Waldkirch (PhD)

JÖNKÖPING June 10, 2020

A Study Exploring CA Program

Conditions to Foster More Successful

Startup and Corporate Engagement

A Study exploring CA Programs

conditions to foster more successful

startup and corporate engagement

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Corporate Accelerators: A Study exploring CA Programs conditions to foster more successful startup and corporate engagement.

Authors: Simon Hagedorn & Robin Thien Tutor: Matthias Waldkirch, PhD

Date: June 10, 2020

Keywords: Corporate Accelerator; Corporate Innovation; Startup Engagement; Corporate Entrepreneurship; Startup Programs

Background: Corporate Accelerators (CAs) are a relatively new phenomenon and

increasingly used by corporates to increase their level of innovation. However, there are still no best practices on how these CA programs can be structured more efficiently in order to serve the needs of startups and corporates simultaneously. Here, most extant research focuses on the general goals of CA programs and the definition of certain core elements and features which describe a CA (i.e. provision of coworking space; educational programs), while disregarding the objectives of the startups participating.

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to understand how current CA programs can be improved, by analyzing the experiences and perspectives of both corporates and startups. It aims to identify, how CA programs can be more successful for corporates and startups.

Method: To satisfy the purpose of this qualitative study, an exploratory research

approach was selected, and a multi-case research strategy applied. Data was gathered through in-depth, semi-structured expert interviews with five managers and three participants of accelerator programs managed by leading multinational corporates. Through a content analysis, new theory was created based on our findings.

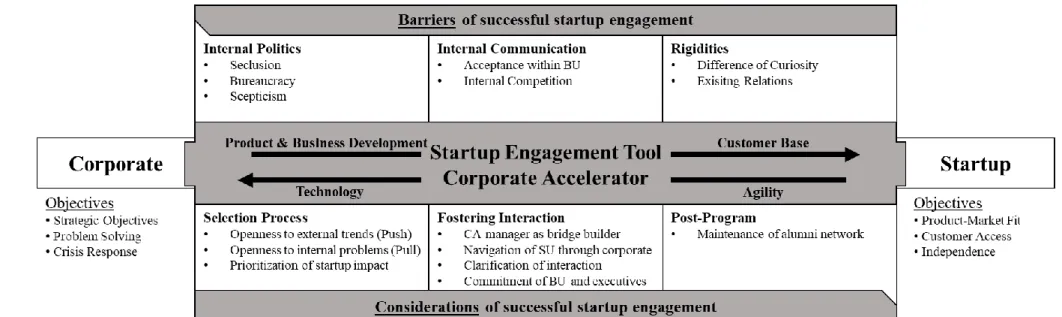

Conclusion: This study shed light on current difficulties that arise in CA programs such as internal politics and bureaucracy, internal communication, corporate rigidities, and the important tasks of CA managers navigating those issues. Our study contributes to research on CAs by (1) emphasizing current barriers of CAs; (2) presenting suggestions for creating more successful CAs; (3) showing how CA managers can foster interactions between corporate business units and startups: and (4) by creating the SET CA model.

Acknowledgements

In our quest for in-depth knowledge of Corporate Accelerators, we were able to get in contact with many kind, bright and intelligent individuals, whose contributions have been indispensable for the results of our study and the time-consuming process of writing this thesis. Therefore, we would like to dedicate this page to them and express our sincere gratitude and appreciation.

First, we would like to express appreciation to our supervisor, Matthias Waldkirch (PhD), who guided us through the entire process of writing this thesis. Thank you, Matthias, for your constructive feedback, objective criticism, and the general positive atmosphere that you created. We would also like to thank our fellow students with whom we could always exchange thoughts and who stood by our side in challenging times. This inner circle of individuals enriched our experience and taught us the importance of camaraderie, collaboration and encouragement.

Next, we want to show our sincere appreciation to all the interviewees who participated in our study. Thank you for taking the time, especially in this unusual circumstance (i.e. Covid-19). We know that your time is very scarce and therefore hope that this thesis will provide useful insights for you.

Furthermore, we want to thank our parents who always emphasized on the importance of education. Without your encouragement and your strong believe in our abilities, we wouldn’t have been able to get to this stage. We hope that our efforts towards academic expertise fills your hearts with pride.

Finally, we want to thank all individuals who mostly remain in the background and whose work is not always obvious initially. We talk about all the staff members at Jönköping University who are cleaning the facilities, support students in times of need (accommodation, health issues, career advice, library officials etc.). A special thanks goes to the staff of RIO, who provide fresh coffee everyday (one of the key ingredients for every student!). Thank you all for your support, we value your contribution.

Table of Content

1 Introduction ... 1

2 Theoretical Framework ... 3

2.1 Corporate Entrepreneurship & Corporate Venturing ... 4

2.2 Delimitation of Corporate Accelerators ... 4

2.3 Corporate Accelerator ... 5

2.3.1 Goals of Corporate Accelerators ... 5

2.3.2 Definition and Core Elements ... 6

2.3.3 Types of Corporate Accelerators ... 7

2.3.4 Design Configuration ... 7

2.3.5 Strategic Alignment between Stakeholders ... 8

2.3.6 Managing CA Programs ... 9

2.3.7 Organizational Design and Performance ... 9

2.3.8 Organizational Design and Information Flow ... 10

3 Methodology ... 11 3.1 Research Philosophy ... 12 3.2 Research Approach ... 13 3.3 Research Design ... 13 3.3.1 Qualitative Research ... 13 3.3.2 Research Strategy ... 14 3.4 Data Collection ... 15 3.4.1 Interview Design ... 15 3.4.2 Time Horizon ... 17

3.4.3 Participant and Sampling Strategy ... 17

3.5 Data Analysis ... 20

3.5.1 Content Analysis ... 20

3.5.2 Trustworthiness ... 25

3.6 Research Ethics ... 26

4 Findings ... 27

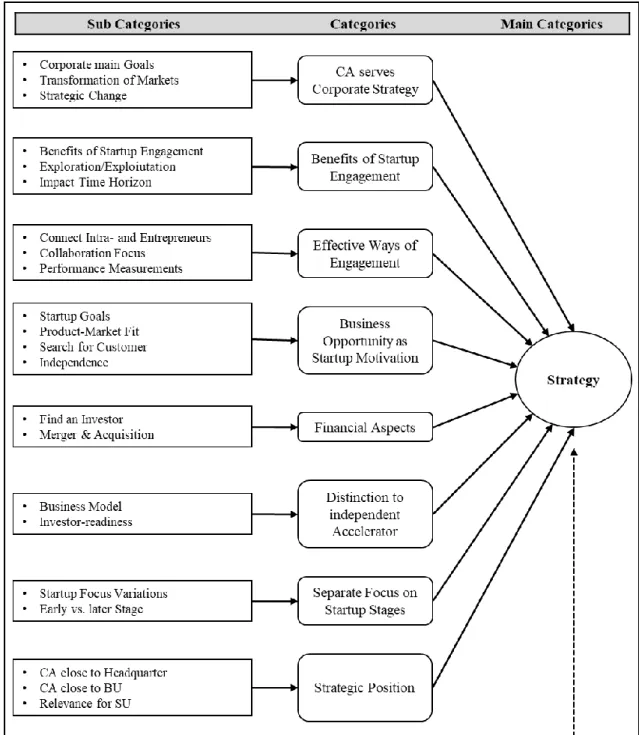

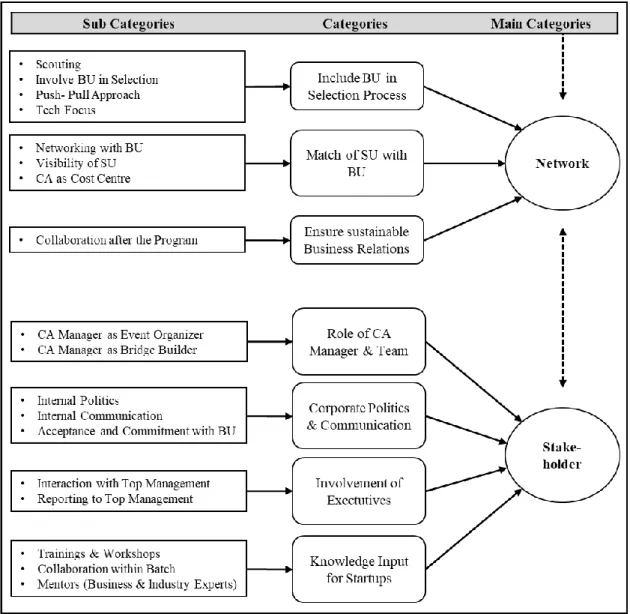

4.1 Tree-Diagram: Based on Content Analysis ... 27

5 Analysis ... 32

5.1 CA as Startup Engagement Tool ... 32

5.1.1 Corporate Strategy ... 32

5.1.2 Startup Objectives ... 35

5.1.3 Business Unit Objectives ... 38

5.2 Barriers of Corporate Accelerators ... 39

5.2.1 Internal Politics and Bureaucracy ... 39

5.2.2 Internal Communication ... 40

5.2.3 Corporate Rigidities ... 42

5.3 Considerations for successful Corporate Accelerators ... 43

5.3.1 Selection Process ... 43

5.3.2 Fostering the Interaction between Startup and Business Unit ... 46

5.3.3 Post-program Considerations ... 51

5.4 The SET CA Model ... 52

6 Conclusion ... 54

7 Discussion ... 55

7.1 Theoretical Implications ... 55

7.2 Limitations & Future Research ... 59

8 References ... 63

Table of Figures

Figure 1: Research Onion ... 12

Figure 2: Extract of Questionnaire to Startups ... 16

Figure 3: Extract of Questionnaire for CA Manager ... 16

Figure 4: Tree Diagram of Findings (Strategy) ... 29

Figure 5: Tree Diagram of Findings (Network, Stakeholder) ... 30

Figure 6: SET CA Model ... 53

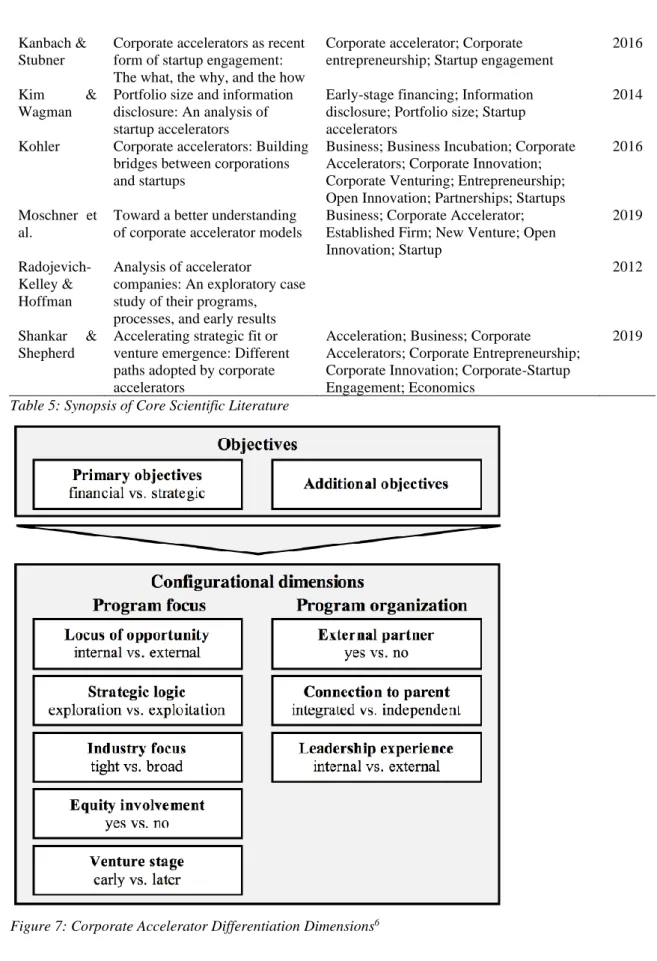

Figure 7: Corporate Accelerator Differentiation Dimensions ... 70

Figure 8: Two-Pathway Model of Corporate Accelerators ... 71

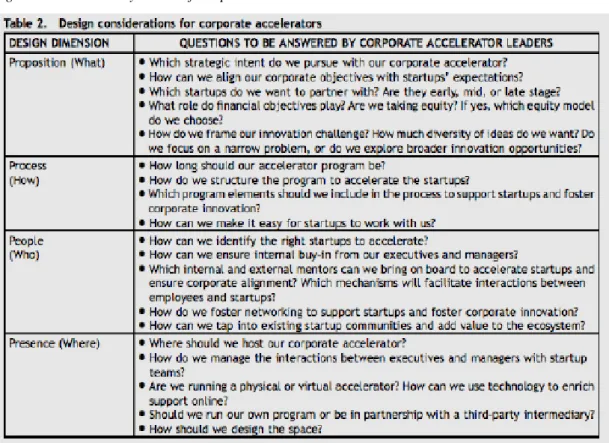

Figure 9: Design Considerations for Corporate Accelerators ... 71

Figure 10: Corporate Accelerator Typology ... 73

Figure 11: Letter of Consent ... 74

Figure 12: Questionnaire for CA Manager (Page 1) ... 75

Figure 13: Questionnaire for CA Manager (Page 2) ... 76

Figure 14: Questionnaire for Startups (Page 1) ... 77

Figure 15: Questionnaire for Startups (Page 2) ... 78

Figure 16: Coding Table ... 79

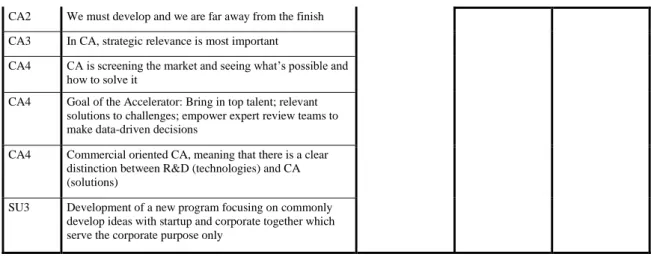

Figure 17: Coding Table (Continued) (1) ... 80

Figure 18: Coding Table (Continued) (2) ... 81

Figure 19: Coding Table (Continued) (3) ... 82

Figure 20: Coding Table (Continued) (4) ... 83

List of Tables

Table 1: List of Interviewees ... 20Table 2: Extract of Anonymized Transcript Created by Researcher 1 ... 21

Table 3: Merged Highlights of Single Researchers ... 23

Table 4: Extract of Coding Table ... 25

Table 5: Synopsis of Core Scientific Literature ... 70

1

Introduction

In the tough race of being ahead of the competition, it is important for corporates to have a reliable, promising and quality source of new businesses. Corporates face rapid changes in their technological-, economic- and competitive environment (Morris, 2011), and need to adapt rapidly to new market changes through constant innovation. Thus, creating or maintaining a competitive advantage through value creation becomes a challenging task (Porter, 1996). The responsibility of this task has further shifted towards the strategic management of a corporate (Guth & Ginsberg, 1990). The terms which deal with this challenge are called corporate entrepreneurship (CE) (Morris, 2011) or entrepreneurial orientation (EO) (Dess & Lumpkin, 2005). Scientific literature about CE and corresponding theories have been developed over decades (Sharma & Chrisman, 1999), while the way entrepreneurship is practiced in corporates is still an evolving process. A relatively new phenomenon in order to face these entrepreneurial challenges are accelerator programs, which were first introduced by Paul Graham in 2005 (Sharma, 2019). Since then, more than 3000 new accelerator programs emerged globally (Hochberg, 2016). Resulting from this independently-run accelerator forms, corporates gained interest in creating their own, internally-run accelerator programs to boost innovation, which are called ‘corporate accelerators’ (CAs) (Kohler, 2016; Weiblen & Chesbrough, 2015). Formerly, there was no clear distinction between independently-run accelerator programs and CA programs in scientific literature (Kim & Wagman, 2014; Radojevich-Kelley & Hoffman, 2012). The year 2015 has seen the first peer-reviewed publications about CA in particular (Hochberg, 2016; Kohler, 2016; Weiblen & Chesbrough, 2015), which have led to more recent scientific investigations focusing on definition, design, structure and processes of CAs (Moschner et al., 2019; Shankar & Shepherd, 2019). Admittedly, the focus mostly lied upon the modelling of different accelerator designs and structures (Hochberg, 2016; Kohler, 2016) linked to suggestions for managers on how to implement and run such programs (Moschner et al., 2019; Shankar & Shepherd, 2019). Thus, CAs represent an emerging phenomenon that still require further analysis. Therefore, the purpose of our research is

to understand how current CA programs can be improved, by analyzing the experiences and perspectives of both corporates and startups.

CAs are dealt as a promising startup engagement form. Corporates rely on the research to provide an evidence-based foundation for CA. Hence, an assessment of the existing theory is useful and necessary to avoid misleading suggestions and conclusions for corporates, which think of installing CA programs. Being a relatively new phenomenon (Shankar & Shepherd, 2019), it is still not known whether CA’s are a certain, defined, and fixed form of startup engagement, or if they are still in the process of development and require adjustments, in order to fulfil their purpose. Thus, it appears interesting to further explore how CA programs are structured and run by corporates, while specifically highlighting the level of corporate and startup engagement within these programs. Therefore, in this research, we aim to answer the following research question:

How can CA programs be more successful for corporates and startups?

By examining this research question through an empirical study, we aim to receive more clarity on the complex dynamics within CA programs and its main stakeholders, exploring both the points of view of corporate managers, who manage these programs, and startup executives, who participate.

In this research, we develop a critical literature review (chapter 2), showing what is currently known in the literature, while exploring the fields of Corporate Entrepreneurship as an introduction to our main topic, CA’s. Here, we provide a general overview of the current literature of CA. In chapter 3, we describe and explain our chosen methodology (i.e. content analysis) and our research approach. After displaying our initial findings (chapter 4), our study continues presenting the analysis (chapter 5). Here, we stress the importance of corporate (business unit) and startup engagement, by providing a descriptive model (i.e. SET CA Model), which provides major insights towards answering our research purpose and question. In chapter 6, we reflect upon our major findings and indicate the contributions to current academic knowledge. Finally, we provide theoretical implications (chapter 7.1) to the reader, discuss our study limitations and specify suggestions for future research (chapter 7.2).

2

Theoretical Framework

In general, the theoretical background can be distinguished into three main research fields. In table 5 (see appendix), core scientific literature for the theoretical background are mentioned and summarized, which shows the origin of this research topic. Starting with a view on the entrepreneurial ecosystems, supports to better comprehend the needs of startups and the elements which are relevant for their existence. Furthermore, we included digitization regarding the conceptualization of entrepreneurial ecosystems caused by the relevance of digitization and its rich content about platforms in the digital age (Hsieh & Wu, 2019; Sahut et al., 2019; Sussan & Acs, 2017; Song, 2019).

Driven by the platform-thinking in entrepreneurial ecosystems, the topic was narrowed down further to cohorts that provide acceleration support to startups (Bliemel et al., 2019). Accelerator programs represents such a cohort. Parallel, accelerator programs are a relatively new phenomenon, which have only recently been investigated in scientific literature (Dempwolf et al., 2014; Radojevich-Kelley & Hoffman, 2012; Kim & Wagman, 2014). It is described as new phenomenon for startup engagement and source for innovativeness (Cohen et al., 2019a; 2019b; Cohen & Hochberg 2014). Especially, corporates are seeking for competitive advantages and are interested in new sources of innovation. They perceive accelerator programs as one tool to achieve entrepreneurial orientation. Here, we put these accelerator programs in the context of corporate entrepreneurship (Anderson et al., 2015; Dess & Lumpkin, 2005; Guth & Ginsberg, 1990; Morris, 2011; Sharma & Chrisman, 1999).

Finally, research on CA literature and existing theories was conducted. Since CAs are a new phenomenon, the literature initially focuses on building concepts and reproduce CA designs (Kanbach & Stubner, 2016; Kohler, 2016; Moschner et al., 2019; Shankar & Shepherd, 2019). Researching about existing CA types and its components and strategic objectives led to the realization, that based on the novelty of the topic, experiences of CA stakeholders (CA managers and startups founders) require more attention. Thus, to be able to analyze CAs and the experiences of its stakeholders, we need to put existing theories in perspective to latest experiences.

2.1 Corporate Entrepreneurship & Corporate Venturing

The practice of corporate entrepreneurship has been studied in the last five decades (Anderson et al., 2015; Westfall, 1969). CE can be understood as a process in existing organizations to create a new organization or go through renewal (Dess & Lumpkin, 2005; P. Sharma & Chrisman, 1999). More in depth, its purpose is to sustain innovativeness through new products and/or services. These corporate entrepreneurial activities are involved in a corporate’s strategic management (Guth & Ginsberg, 1990). The integration of CE into the strategical management tasks of a corporate shows the relevance of sustaining innovativeness. Furthermore, large corporates seeking intensively for alternatives of entrepreneurial activities to maintain or improve their innovativeness (Weiblen & Chesbrough, 2015).

CE can be divided into two categories: strategic renewal and corporate venturing. In the strategic renewal process, a corporate can choose a complete renovation of the current strategy, a sustained regeneration, domain redefinition, organizational rejuvenation, or a business model reconstruction (Morris, 2011). Corporate venturing includes internal corporate venturing, cooperative venturing, and external corporate venturing (Morris, 2011). Internal corporate venturing focuses on the development of new ventures and innovations through own employees and can be seen as equal to intrapreneurship. It requires an entrepreneurial drive, the ability to exploit opportunities and implement these opportunities. All activities take place in the context of an existing corporate (Ma et al., 2016). Also, cooperative venturing serves as a form of collaboration between the corporate and one or more external development partners. Therefore, the new business is created and owned by the corporate and the external partner (Morris, 2011). With external corporate venturing the corporate invests or acquires an external business. This investment facilitates the founding and/or growth of the new business (Titus et al., 2017). Examples for external corporate venturing are: idea-sourcing events, business plan competitions, hackathons, incubation, and seed investments (Mocker et al., 2015).

2.2 Delimitation of Corporate Accelerators

In early accelerator research literature, the authors didn’t distinguish between independent and CAs (Heinemann, 2015; Pauwels et al., 2016). Here, a common definition of accelerators is used: An accelerator is a “fixed-term, cohort-based program,

including mentorship and educational components that culminates in a public pitch event, often referred to as demo-day” (Cohen, 2013; Cohen & Hochberg, 2014).

In recent research, authors emphasized this difference and expressed a delimitation of independent to CAs. They overlap with the above-mentioned definition of independent accelerators but add the characteristic of sponsorship respective management of the program, through one or more corporates (Kohler, 2016).

Before the establishment of Y Combinator as the first accelerator program in 2005, incubators have been the tool for new venture creation, which were investigated by scientific literature in the past (Bruneel et al., 2012; Grimaldi & Grandi, 2005; Isabelle, 2013; Vanderstraeten & Matthyssens, 2012). In their paper, Grimaldi & Grandi (2005) distinguish between four different categories of incubator. Business Innovation Centers (BIC), University Business Incubator (UBI), Independent Private Incubator (IPI), and Corporate Private Incubator (CPI). Both BICs and UBIs, are structured similarly in terms of space, infrastructure, communication channels for visibility, and access to external financing. Here, only UBIs focus on the transfer of scientific and technological knowledge from universities to the business world. Furthermore, corporate and independent private incubators exist. While IPI resemble independent accelerators in their characteristics (e.g. Y Combinator), CPI support the emerge of new BUs (spin-offs). Comparable to the new trend of CA, private incubators, IPI and CPI shorten the time-to-market, offer more specialized services, and increase the networking factor. All three mentioned chances in activities tend to show similarities to accelerator programs (Grimaldi & Grandi, 2005). To conclude, incubators still exist in the private sector, while these programs adapted characteristics, which rather resemble an accelerator program caused by the preferred acceleration factors of these programs.

2.3 Corporate Accelerator

2.3.1 Goals of Corporate Accelerators

A relatively new phenomenon in the entrepreneurial activities of corporates are CAs (Hochberg, 2016; Moschner et al., 2019). Scientific literature has recently started to analyze and model the design of different accelerators (Moschner et al., 2019). CAs allow established corporates, to increase its internal level of innovation by engaging with young,

dynamic, and innovative ventures to employ emerging technologies and reinvent business models (Cohen, et al., 2019a). Thus, a CA facilitates engagement between large corporates and smaller startups with the overall idea to primarily increase the overall level of innovativeness of the large corporate by fostering innovation from entrepreneurial companies (Shankar & Shepherd, 2019). Therefore, accelerator programs have become an essential aspect of the entrepreneurial ecosystem and in particular serve as an entrepreneurial vehicle for engagement within the startup ecosystem (Moschner et al., 2019; Shankar & Shepherd, 2019). Furthermore, from a macro perspective, CAs support already existing theories like ambidexterity. Ambidexterity represents a corporate’s “ability to simultaneously execute today’s strategy while developing tomorrows arises from the context within which its employees operate” (Birkinshaw & Gibson, 2004). These programs either aim to increase a company’s capability of alignment - here, the importance lies in the exploitation of the corporate’s core assets and values-, or it focuses on adaptability in order to quickly see new opportunities in the market (Birkinshaw & Gibson, 2004). These two different design strategies for accelerator programs are further portrayed in Shankar and Shepherd’s paper where they distinguish between the above mentioned two pathways: accelerating strategic fit or accelerating venture emergence (Shankar & Shepherd, 2019).

2.3.2 Definition and Core Elements

To begin with, Kohler (2016) briefly summarizes CAs as the following:

“Corporate accelerators are company-supported programs of limited duration that support cohorts of startups during the new venture process via mentoring, education,

and company-specific resources.” (Kohler, 2016)

Next, there are certain core elements and features which describe an accelerator: specific time period (mostly 3-6 month); provision of coworking space; educational programs and access to (industry experts). However, noticeable differences apply for individual CA programs, therefore identifying specific characteristics and components is difficult as there is not one single best practice CA design1 to date (Cohen, et al., 2019b).

1 When mentioning “CA design” or “design elements” we are referring to the individual parts or

components that need to be created to establish a program (i.e. how is the program structured? Who is responsible? Which startups are relevant? Where is the CA located? What is the strategic goal?)

2.3.3 Types of Corporate Accelerators

Researchers tried to highlight different design elements and program components which are relevant when considering implementing or install a CA (Kanbach & Stubner, 2016). In their inductive study, Pauwels et al. (2016) investigate 13 accelerators across Europe and identify three different types of accelerators: ecosystem builder; deal-flow maker and welfare stimulator, as well as five key design elements with its sub headers: program package; strategic focus; selection process; funding structure; alumni relations (see table 6).

Moreover, by analyzing 13 Germany-based CA programs, (Kanbach & Stubner, 2016) have developed a model to identified four types of CAs: the listening post; the value chain investor; the test laboratory; and the unicorn hunter. Firstly, the listening post wants to identify recent trends and developments in relevant markets as well as establishing new relationships (Kanbach & Stubner, 2016). Secondly, the value chain investor aims to identify, develop, and integrate new products and services which fit in the parent corporate’s value chain (Kanbach & Stubner, 2016). Thirdly, the purpose of the test laboratory is the creation of a protected environment in which internal and external business ideas can be tested (Kanbach & Stubner, 2016). Finally, the unicorn hunter invests in rising stars, boost them to more value in order to earn a financial premium at the time of exit(Kanbach & Stubner, 2016). The authors also consider the financial and strategic objectives of a CA program as well as additional objectives(Kanbach & Stubner, 2016) 2.

2.3.4 Design Configuration

Based on the objectives the configurational dimension can be build. The first pillar for the design configuration is the program focus. Meaning, the locus of opportunity, strategic logic, industry focus, equity involvement, venture stage. The second pillar represents the program organization with or without external partners, the connection to the parent corporate, and leadership experiences(Kanbach & Stubner, 2016). The model allows a distinction between the CA programs in all the above-mentioned layers. Regarding the primary objective, all types follow a strategic goal, except the unicorn hunter who follows financial goals.

Comparably, Kohler (2016) provides two essential design dimensions which support managers in building accelerators that leverage startup innovations and link it to existing corporate strategy. Based on 40 management interviews, the author provides both, a framework and strategy for designing CAs. The first structure dimension shows four elements: Proposition (what?); process (how?); people (who?); presence (where?) (illustrated in Figure 9). These elements need primary attention in order to create the basic structure. Secondly, there is the design dimension of host choice: Inside corporate; outside corporate; independent accelerator; virtual accelerator(Kohler, 2016). Every dimension is portrayed with its individual benefits and drawbacks. At last, the overall goal is to align corporate innovation (corporate view) and valuable support mechanisms (startup view), to satisfy both, the innovation of traditional corporates and the scaling of startups(Kohler, 2016).

What is more, Pauwels et al. (2016) highlight the objectives of the accelerator shareholders as the main component driving an accelerator’s activity. In CAs, these shareholders are either the corporate or the startup participating in an accelerator. Also, by providing different element types, specific program features are linked to their performance. As a result, the article highlights the importance of the profoundly explained key design elements (program package; strategic focus; selection process; funding structure; alumni relations) which have important implications for theory and practice in regard to accelerators(Pauwels et al., 2016).

Similarly, (Moschner et al., 2019) provide an overview of the different CA types available, presenting objectives and characteristics to identify suitable solutions for individual corporates. The authors categorize these programs into four models which vary based on number of participants and management structure. The results show that it is essential for corporates to choose the correct model for their individual business objectives while ensuring that these models are integrated into other innovation activities (Moschner et al., 2019).

2.3.5 Strategic Alignment between Stakeholders

Arising differences between corporates and startups who are combined in CA programs can be a true challenge(Kohler, 2016). For this reason, accelerators need to be designed effectively to provide value for both participants (Kohler, 2016). Especially in large

corporates, there are usually many individual attempts by business units (BUs) to innovate. These attempts need to be aligned and not run in isolation, meaning that their overall potential needs to be synchronized within one accelerator model(Moschner et al., 2019). Missing strategic alignment may lead to irritations and loss of momentum between corporate and startup, especially when linked to different goals or hidden agendas (Kohler 2016). What is more, Moschner et al. (2019) recommend a holistic approach for startup collaboration by aligning accelerator model with overall company strategy. CAs need to be designed properly in order to satisfy corporate objectives and startup objectives simultaneously, which optimally leads to successful results for both parties(Pauwels et al., 2016; Kohler, 2016; Moschner et al., 2019; Cohen et al., 2019b).

2.3.6 Managing CA Programs

Another important aspect is the management of CA programs. By analyzing four different accelerator programs, Shankar & Shepherd (2019) show that companies distinguish two different ways of managing accelerators: accelerating strategic fit or accelerating venture emergence3. When running CAs, strategic choices and timeframes pressure companies in their operation of the accelerator, as well as in their judgement on potential startups for acceleration(Shankar & Shepherd, 2019). Simultaneously, startups are under pressure because they must achieve both, market-fit and corporate-fit in accelerators which might distract from the initial goal of innovation (Kohler, 2016). Therefore, it is of upmost importance to reduce wrong judgement regarding participants of CAs, to prevent immense costs (time, money, resources) for both parties. Thus, the authors provide viable insights into the processes of accelerators and highlight two distinct outcomes: nurturing innovation or nurturing ecosystems, which shows how companies communicate and deal with entrepreneurial startups to increase their own level of entrepreneurship(Shankar & Shepherd, 2019).

2.3.7 Organizational Design and Performance

Besides, Cohen et al. (2019a) analyzed correlations between organizational design and operation of accelerator programs on the one hand, and to theories of entrepreneurial performance on the other. They tried to test connections between design elements and performance. For example, there is a strong correlation between the type of accelerator

sponsor and accelerator director which clear indications of design structures that lean towards the founder’s objectives (Cohen et al., 2019a). For this reason, accelerator programs founded by former capital investors have a stronger focus on return on investment than state founded accelerators (Cohen et al., 2019a). Additionally, accelerators differ in the overall performance of their portfolio firms. Investor led accelerators for instance show higher numbers of capital raised post-graduation (Cohen et al., 2019a). For startups it is important to make the correct choice when accepting an offer, because according to Kohler (2016), they can be limited in their capacity to team up with other companies (CA owner competition) once attending specific accelerator programs, which could potentially disrupt the accelerator founder company (i.e. Pepsi vs. Coca Cola).

2.3.8 Organizational Design and Information Flow

Once accepted into a CA program, startups enter a new location and get access to new information which needs to be leveraged and integrated. Cohen et al. (2019b) use a multiple-case study (participating ventures; directors; and mentors) of eight U.S. accelerators, to explore how accelerator design choices influence start up’s ability to access, interpret, and process external information to survive and flourish. The authors analyze the challenges which naturally occur to entrepreneurs in general (not just those being part of accelerators) and highlight organizational design choices (consultancy with mentors or customers; duality between privacy and transparency; standardization vs. tailor-made solutions) which accelerators leverage in order to respond accordingly to these challenges. Unacknowledged these challenges can lead to inferior performance or bankruptcy(Cohen et al., 2019b).

Firstly, Cohen et al. (2019b) show that consultancy with mentors or customers should be concentrated to improve information search in entrepreneurs. Many meetings and knowledge exchange at the beginning of the program provide a broader amount of data to choose from. Also, when choosing between privacy and transparency, transparency is the preferred option because by exchanging knowledge with other participants and mentors, entrepreneurs receive additional information which might have been missed otherwise, because entrepreneurs mostly overestimate their own levels of knowledge (Cohen et al., 2019b). Unfortunately, many entrepreneurs overestimate competitive threats which lead them to feel anxious initially when having to share knowledge.

However, by observing pitches, sharing office space and discussing individual progress, entrepreneurs are generally better off then otherwise(Cohen et al., 2019b). At this point it is also important to let startups engage with market forces (instead of shielding them), in order to receive important market feedback, which could help the corporate to adapt (Kohler, 2016). Finally, when deciding between standardization and tailor-made solutions, standardization is key for accelerators. Thus, meetings, seminars, peer gatherings and other events should be structured and managed accordingly by mentors. This will most likely result in more reflection by the entrepreneur, especially in very early-stage firms (Cohen et al., 2019b). Additionally, early stage entrepreneurs are naturally satisfied prematurely when searching for external information. Here, standardized designs force the entrepreneur to question already accepted choices, which consequently results in an additional search for broader sets of alternatives (Cohen et al., 2019b). Finally, this study adds to traditional literature on entrepreneurship and provides a deep insight into accelerator designs, from both a director’s perspective (choosing correct design choices to increase accelerator impact) and entrepreneur perspective (identifying designs to look for when choosing accelerators) (Cohen et al., 2019b).

3

Methodology

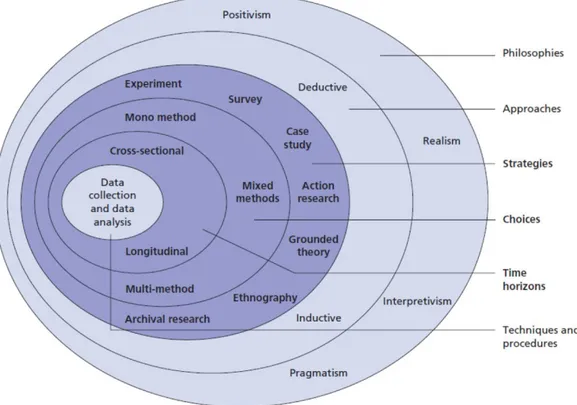

This chapter aims to show the reader how we proceed through the whole creation process of this scientific work. This thesis is guided by the principles of completeness, clarity, and credibility(Zhang & Shaw, 2012). We have a solid understanding how to conduct scientific research and explain briefly different philosophies, approaches, designs, purposes, and strategies. Afterwards decisions for a certain option are shown and examined in more detail. Furthermore, the data collection processes and analysis are explained as well as their reasoning. The structure of the chapter is inspired by the research onion created by Saunders (2012) and illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Research Onion4

3.1 Research Philosophy

The research philosophy affects the way how we conduct and interpret research. Thus, it is important to explain which ontology and epistemology was chosen and to elaborate on the reasons (Easterby-Smith, 2018). To begin with, ontology, in simpler terms is described as “the existing” or “the philosophy of being” (Easterby-Smith, 2018). For our research we chose relativism as the fitting researcher concept of reality. In relativism, reality depends on the individual’s perspective, meaning that knowledge of the external world is relative to the procedure used in gathering the knowledge and the people who create it (Easterby-Smith, 2018).

Next, the second pillar is epistemology, which according to Easterby-Smith (2018), is the “philosophy of knowing”. The essence for researchers applying interpretivism or also called “social constructionism” is to adopt empathic attitude. Here, the human rather than the object is in the focus of the research. It is important to understand the role of the human and how it interacts with others (Saunders et al., 2012). For our research, social constructionism is the corresponding epistemology to relativism since activities mainly

deal with the interaction between humans and their perspective on the world. In our case, we are interested in our interviewees’ perspectives and impressions on CAs. This epistemology allows us to develop own interpretation of the collected data. As researchers, we are involved in the actor’s world and analyze the data in a subjective way. Chapter 3.5.1 describes how we deal with the fact of being two authors with separate and individual perspectives on the same data set.

3.2 Research Approach

This thesis adopts an inductive research approach for the creation of the thesis. CA are a new phenomenon and a rising topic in the scientific literature. The theory behind CA is new, since the first regular accelerator has been established only in 2005 and the first CAs appeared around 2010 and 2011 (Shankar & Shepherd, 2019). Existing theory is not sufficient and complete. We cannot take it for granted that all information is already explored and processed in the relevant literature. An inductive approach is exploratory by nature and is conducted with the intention to develop and build a new theory (Cutis & Cutis, 2011; Saunders et al., 2012). Exploratory research asks what is happening, especially on new phenomena and reveals new insights (Robson, 2002). Adams and Schvaneveldt (1991) state that exploratory research has the flexibility to be general in the beginning, while narrowing down the research topic during the research process. Our research purpose is to assess CA programs in reality, based on collected knowledge from theory. Through the interviews we want to reveal new insights and the status quo of these accelerator programs. As argued by Creswell (2009), inductive reasoning is particularly suitable for studying recent phenomena, which makes this type of research approach ideal for the assessment of novelties such as CAs. Adopting an inductive approach will allow to analyze collected data, moving from the specific to the general, based on the existing theories, in order to reach a conclusion and contribute to CA literature (Preissle, 2008).

3.3 Research Design

3.3.1 Qualitative Research

When conducting qualitative research, the overall goal is to figure out what “things” mean and how they work in context (Easterby-Smith, 2018). Moreover, Patton (2015) describes seven contributions of qualitative research, which support in finding answers to our research question. These are illuminate meanings, study how things work, capture

people’s stories, perspectives and experiences, investigate systems and their consequences, understand how and why context matters, identify unintended consequences, and making case comparisons to discover important patterns and themes across cases. For the present thesis, qualitative research design is used to assess CAs and answer our stated research questions. Moreover, qualitative research supports us in understanding and exploring different CA design choices, motives and priorities regarding design elements. Additionally, we mostly relied on two main sources of information. One was semi-structured interviews with CA managers and startups as described. The other one was program specific information, which was analyzed if possible (i.e. company homepage, magazines), to find patterns regarding main objectives and design setups.

3.3.2 Research Strategy

This study will adopt a multi-case study approach, which is most suitable as CA programs are a new phenomenon in research, and the usage of case studies supports exploring novel topics (Yin, 2009). Furthermore, multiple-case study was chosen over single-case study, because the assessment derivation of improvements can only be achieved, when we observe several CA programs. A multiple-case study allows for recognizing patterns, contradictions and also the intensity of these findings (i.e. when several CA managers mention similar issues). One can than argue that these issues are of relevance in general and not just applicable to one single case. Additionally, the number of CAs is growing but with 71 CA programs in 2016 still low (Shankar & Shepherd, 2019). We identified and reached out to five CA programs which suit our understanding of CAs. For our specific research purpose, this number of CAs seems reasonable and sufficient for a high degree of quality, relevance, and generalizability. Besides, according to past research regarding a case study approach, three to five in-depth case studies are a suitable number for sufficient results(Eisenhardt, 1989). In chapter 3.4.3, further descriptions regarding the selected set of CAs and the reasoning behind the sample are displayed.

What is more, Yin (2009) distinguishes also between holistic and embedded case study design. The two types distinguish from each other in terms of units of analysis. With the holistic case design, only one case in a certain context is investigated. In an embedded multiple-case study, multiple units are analyzed within one case. In this thesis, five different CA programs were investigated by interviewing relevant CA managers.

Additionally, we verified information and added an additional perspective in three cases by interviewing three startup founders which participated in different accelerator programs.

While executing a multiple-case study it is important to respect the replication logic (Yin, 2009). After uncovering the first relevant findings in the first case, it is important to test the relevance by adding a second, third or even more cases. Either the other cases replicate the finding of the first case (literal replication) or they are contradicting (theoretical replication). Thus, the findings are getting robust. In the conducted interviews, we replicated the questionnaire in order to be able to compare the cases. Here, the questionnaire was initially rather broad. When we realized that some information was irrelevant, is not leading to new insights, or is out of scope for our research purpose, we made minor adjustments. Respectively, a semi-structured interview allows for asking additional questions regarding topics which provided more relevant and insightful answers. After conducting the first interviewees, the next one was selected carefully, always considering which additional new case could potentially provide the best value in terms of new insights.

Therefore, it could be argued, that a holistic multiple-case study is suitable for our study and guarantees scientific quality. Applying the design to our study, our cases are CAs. In addition, in three of five cases, extra unit of analysis were added (startup perspective) in order to strengthen the collected information through verification and reduction of subjectivity.

3.4 Data Collection

3.4.1 Interview Design

Expert Interviewees

For this research, semi-structured interviews were conducted with either managers of CAs or former participants (startups) of such programs. By interviewing these individuals, the aim was to gain insights into not just the structure of CA programs but also the motivations, opinions, thoughts, downsides and benefits.

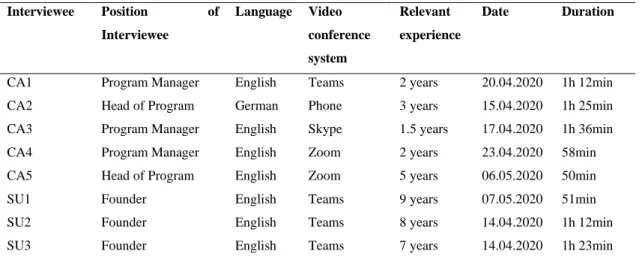

Questionnaire

The questionnaire used for the present thesis aims to gain a general understanding of the corresponding CA of the interviewee and its structure or design considerations. The structure of the questionnaire and the questions themselves are derived from the investigated structure of the articles, which are displayed in the literature review. It is divided into five main parts: Purpose, Proposition, Process, People, and Presence. Since CA managers and alumni startups were interviewed, the questions needed some modifications which resulted in two separate questionnaires. Excerpts of the questionnaire are displayed in Figure 2 and Figure 3. In this case, it shows the questions for the part purpose. The complete questionnaires can be found in the appendix (Figure 12 and 14).

Figure 2: Extract of Questionnaire to Startups

Figure 3: Extract of Questionnaire for CA Manager

The survey includes questions that are objective in nature (e.g. “Where is the corporate accelerator located?”), and questions that provide the interviewee with the freedom of including their personal opinion or perspective (e.g. “Why did you decide for this form of startup engagement?”). The questions are mostly open, which ensured the discovery of new information and not only a confirmation of existing theory. The interviewees were able to respond with their thoughts, feelings, and beliefs (Marks & Yardley, 2003). Besides, the disadvantage of open questions is that the interviewee might drift in directions which don’t provide value to the research purpose of this thesis. To prevent this scenario from happening, every interview started with a short introduction regarding research topic and research purpose. With this information in mind, the interviewees knew the specific aim of the interview and could focus on relevant information. In case an interviewee drifted of topic or answered intensely, follow-up questions were adjusted

accordingly. For instance, if information of two or more questions were covered in one answer, we dispensed with the question in order to avoid repetition but rather use the time to gain deeper insights to certain topics (Saunders et al., 2012).

Interview Techniques

Every interview began with small talk to get comfortable with each other. Thereby, intending to increase the confidence of the interviewee and to create an atmosphere of trust and comfort. Additionally, the interviews were recorded and notes were taken (Saunders et al., 2012), which increased the level of concentration and focus to fully concentrate on creating an insightful conversation, without unnecessary distractions. Furthermore, the interviewees were informed at the beginning of the recording, to increase transparency. In general, the order of the questionnaire was followed. However, whenever interviewees could provide additional insights or clarification was needed from our side, the interview techniques of ‘probing’ and ‘laddering’ were used (Marks & Yardley, 2003). Here, ‘probing’ is helpful to clarify a certain point (i.e. Researcher 1:

“Was that expectation fulfilled?”), while ‘laddering’ can provide a better understanding

of the reasoning behind the interviewees’ actions (i.e. Researcher 2: “Why [did they]

decide to run the program in both [cities]?”). It allows access to personal thoughts,

opinions, and behaviors, which are useful for the analysis and the assessment of CAs. 3.4.2 Time Horizon

According to Saunders et al. (2012), the time horizon of a study is a snapshot, which is important to consider in order to place the results of the data collection. All interviews took place between April 14th and May 7th 2020. The interviewees presented information about past experiences regarding CA management or participation. Especially the startups executives that we interviewed, talked about the conditions of the program, going back as far as 2015 and 2016. However, for the assessment of CA programs this perspective is very valuable, since it provides insights from a very early stage of CA programs. On the contrary, CA managers focused on the status quo of their existing CA program and were specifically asked about changes and the reasons behind those changes.

3.4.3 Participant and Sampling Strategy

The samples were selected purposefully in order to create information-rich cases, which is important as emphasized by Patton (2015). Thus, the interviewees in this study had to

fulfil certain quality criteria to be considered “experts” (Easterby-Smith 2018). The following sub-chapters provide further insights into the data collection process, from whom data was collected and why.

Selecting Corporate Accelerator

The distinction between corporate and independent accelerators limit the choice of accelerator program in the sense that only accelerator programs which are exclusively managed by one corporate were considered. As described in chapter 2.3, there are distinctive differences between these two models of accelerators. Additionally, all powered by accelerator (Kohler, 2016) were eliminated, because those are run by external management. Thus, by focusing on corporate-managed accelerator programs, relevant insights are gained in order to understand the motivations of corporates and its BUs. This information is essential to identify improvements of these CAs in contrast to corporate entrepreneurship. All CAs investigated in this study are owned and managed by multinational corporates, which are amongst the top-ranked corporates in the world based on revenue.

Selecting Interview Partners

After relevant CAs were identified, program executives were researched. Here, individuals with intensive knowledge of the corporate context and its intentions on running CAs, were sought out. Consequently, individuals in strategic positions, either within the program or above it, were in the scope of this research. Furthermore, one could argue that deep insights can only be communicated when the individual has worked in the CA program for at least two years. Only in one case (CA3), a reasonable exception was made, since this individual worked in related positions within the corporate for over nine years. Thus, this interviewee was even better equipped to describe the processes and issues between the CA program and the BUs.

What is more, in order to cross-check and ensure transparency, the startup perspective on CA programs, was also included. Therefore, three interviews with founders of startups were conducted, who had participated in one of the programs in question. Two of the three founders have been alumni’s and participated in two different programs. One founder has been in the end phase of his program, at the moment the interview took place. All interview partners from the startup side were experienced founders, with at least seven

years of experience (see Table 1). The goal was to ensure as much diversification between the three startup interviewees as possible, to receive a broader picture of the CA programs and also to reduce the subjectivity of the founders. For instance, if one founder experienced negative interactions with the CA and its managers, it was assumed that this person is likely to display a negative picture. Through adding a second opinion, subjectivity in several aspects was neutralized. Furthermore, at the time of data collection, most founders were focusing on surviving the “Corona pandemic” and in anticipation of a following economic crises. Beside the existence of many program alumni, the response rate was low which increased the need to cover as many perspectives as possible in a few interviews. Here it needs to be said that the CA managers were approached based on their position and founders based on their participation in a relevant program. However, positive answers were only sent by male founders and CA managers. It is more likely, that the gender of the interviewees doesn’t have an impact on the received insights about the CA programs, although the inclusion of female interviewees in the data collection would have been valuable.

All interviewees are displayed in Table 1. In total, nine interviews were conducted, which lasted between 50 and 96 minutes. In seven out of eight cases, the interview language was English, which mostly was the only common language of communication. In some cases, the interviewees were able to speak the researchers’ mother tongue (i.e. German). Here, the choice of language was given to the interviewees. Only in one case, the interviewee preferred German as interview language in order to provide more detailed insights. This approach guaranteed the highest amount of information. All interviews took place in a digital form by using video conference system (i.e. Zoom or Teams). One interview took place via a phone call as it turned out to be more convenient for the interviewee. Mostly, the conversations were taking place with audio and video, in order to create a more personal atmosphere. However, in some cases the interviewees felt more confident without video. Here it is important to mention that, the confidence and preferences of the interviewee were taken into consideration at all times. Unfortunately, a face-to-face interview was not feasible, as a consequence of geographical distances, as well as travel restrictions, which were in place at the time of the study (i.e. Covid-19). The interviews took place in the time period between April 14th and May 7th, 2020.

Table 1: List of Interviewees

In order to fulfil clarity and credibility (Zhang & Shaw, 2012), letters of consent were sent in advance, to inform the interviewees about the thesis (i.e. research purpose, usage of data collected, anonymity). To acknowledge the research procedure, the interviewees were asked to provide signed letters of consent. By conducting the research in this way, key ethical principles (Bryman & Bell, 2011) were followed, which are also further described in chapter 3.6.

3.5 Data Analysis

In the following paragraphs, describe and explain how the raw data was analyzed and transformed into a meaningful framework. Here, content analysis was used to extract the most relevant insights from the present data set.

3.5.1 Content Analysis

To begin with, the collected data was analyzed using content analysis, a method that allows to systematically describe the meaning of qualitative data. It is the most common analysis approach for qualitative data (Elo et al. 2008, Kondracki et al. 2002). Content analysis is a time-consuming procedure (Hsieh et al., 2005), and it is important to mention, that the quality outcome of a content analysis depends on the researchers’ skills and interpretation of the data.

The body of the analysis is a coding frame in which the material is successively assigned to different categories. This frame is the fundament for the presented findings, descriptions and interpretations. Furthermore, qualitative content analysis is characterized

Interviewee Position of Interviewee Language Video conference system Relevant experience Date Duration

CA1 Program Manager English Teams 2 years 20.04.2020 1h 12min

CA2 Head of Program German Phone 3 years 15.04.2020 1h 25min

CA3 Program Manager English Skype 1.5 years 17.04.2020 1h 36min

CA4 Program Manager English Zoom 2 years 23.04.2020 58min

CA5 Head of Program English Zoom 5 years 06.05.2020 50min

SU1 Founder English Teams 9 years 07.05.2020 51min

SU2 Founder English Teams 8 years 14.04.2020 1h 12min

by data reduction, structure, and flexibility (Schreier, 2014), which is shown in the following section, where the overall procedure is displayed.

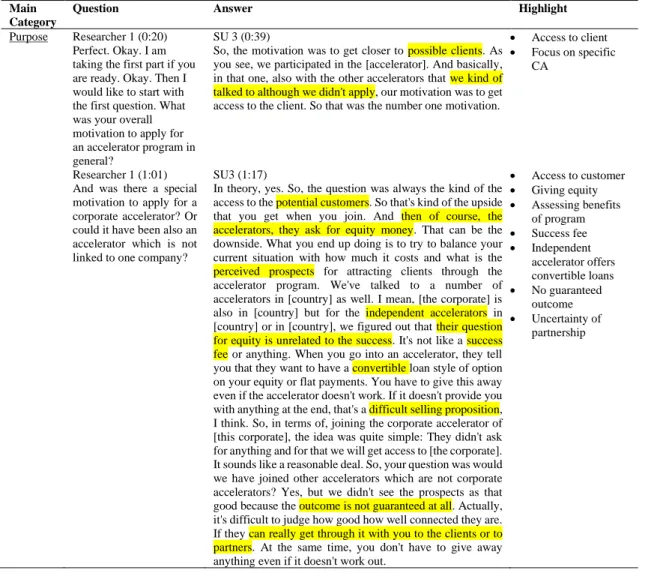

Transcripts

A record of every interview was made in order to create a transcript for further content analysis. Having a transcript allows to highlight, comment and absorb relevant content from the interview more easily. An extract of an anonymized and processed transcript can be found in Table 2. Here, going through the transcripts and audio separately, while creating individual notes, helped to identify patterns and common understandings.

Main Category

Question Answer Highlight

Purpose Researcher 1 (0:20) Perfect. Okay. I am taking the first part if you are ready. Okay. Then I would like to start with the first question. What was your overall motivation to apply for an accelerator program in general?

SU 3 (0:39)

So, the motivation was to get closer to possible clients. As you see, we participated in the [accelerator]. And basically, in that one, also with the other accelerators that we kind of talked to although we didn't apply, our motivation was to get access to the client. So that was the number one motivation.

• Access to client • Focus on specific

CA

Researcher 1 (1:01) And was there a special motivation to apply for a corporate accelerator? Or could it have been also an accelerator which is not linked to one company?

SU3 (1:17)

In theory, yes. So, the question was always the kind of the access to the potential customers. So that's kind of the upside that you get when you join. And then of course, the accelerators, they ask for equity money. That can be the downside. What you end up doing is to try to balance your current situation with how much it costs and what is the perceived prospects for attracting clients through the accelerator program. We've talked to a number of accelerators in [country] as well. I mean, [the corporate] is also in [country] but for the independent accelerators in [country] or in [country], we figured out that their question for equity is unrelated to the success. It's not like a success fee or anything. When you go into an accelerator, they tell you that they want to have a convertible loan style of option on your equity or flat payments. You have to give this away even if the accelerator doesn't work. If it doesn't provide you with anything at the end, that's a difficult selling proposition, I think. So, in terms of, joining the corporate accelerator of [this corporate], the idea was quite simple: They didn't ask for anything and for that we will get access to [the corporate]. It sounds like a reasonable deal. So, your question was would we have joined other accelerators which are not corporate accelerators? Yes, but we didn't see the prospects as that good because the outcome is not guaranteed at all. Actually, it's difficult to judge how good how well connected they are. If they can really get through it with you to the clients or to partners. At the same time, you don't have to give away anything even if it doesn't work out.

• Access to customer • Giving equity • Assessing benefits of program • Success fee • Independent accelerator offers convertible loans • No guaranteed outcome • Uncertainty of partnership

Table 2: Extract of Anonymized Transcript Created by Researcher 1

Coding Rules

We agreed on basic coding rules in order to reduce the amount of content which needs to be discussed after every interview transcript. These coding rules had to be applied to every transcript without exception. Furthermore, we went through the other researcher’s coding

results to cross-check and make final adjustments before adding the codes to the overall frame. The coding rules below are presented below:

1. Keep subjectivity on the code level: It is important to understand what the individual interviewees thought and what their opinions were. This procedure allowed flexibility and included the interviewee’s subjective opinion in the assessment of the different parts of the CA program. Including the emotions of the interviewees played an important role for the analysis of the data.

2. Watch out for third-party statements: When realizing that the interviewees were talking about something, they had no real knowledge of (e.g. talking about another startup and its interaction with the corporate), this content was ignored and not included in the codes. This procedure ensured a high-quality standard and excluded assumptions or guessing, which might not be true or manipulative. 3. Code interview per interview: It made more sense, coding one interview after

another instead of section for section. This approach helped in following the interviewees thoughts and provided a better understanding when the interviewees referred to previous statements.

Merging Separate Highlights to Codes

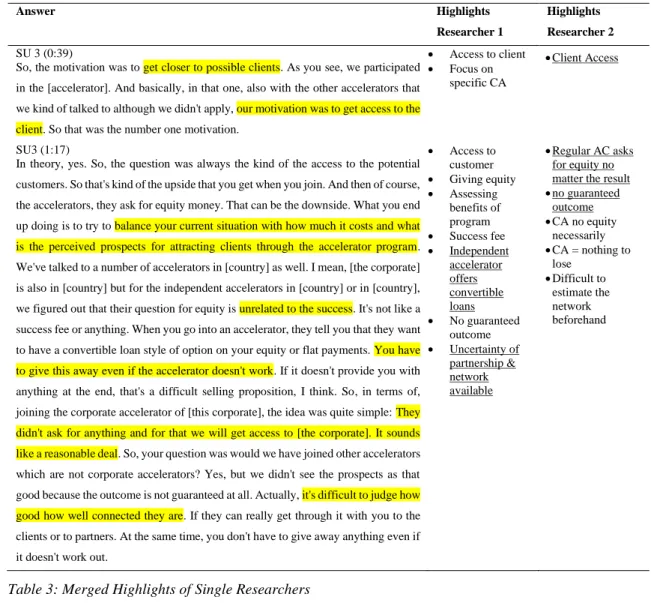

As mentioned above, content analysis depends on the researchers’ interpretation. To reduce the subjectivity of the researcher, we made use of the fact that we are two researchers with different perspectives. After highlighting the most relevant content of the first interview separately, every individual opinion was discussed on the relevance of the content and agreed upon a common understanding of relevant aspects. The comparison, adjustment and compression of the relevant content, which is identified and highlighted by the single researcher, is occurred after every interview and is the basis for the created codes. Only for the last two interviews, researcher 1 was responsible for the coding. We agreed on this procedure for the following three reasons: time saving, learning-process in the understanding of the other researcher’s perspective during the first six interviews, and a specialized focus on certain codes. Table 3 illustrates the procedure for the final creation of codes. Going from answer to answer, we discussed our individual views on the interviewees statements and agreed on the relevant content. The agreed content is underlined. Following this process, ensured that the codes included only content which was reliable and related to the general topic of CA.

Answer Highlights Researcher 1

Highlights Researcher 2

SU 3 (0:39)

So, the motivation was to get closer to possible clients. As you see, we participated in the [accelerator]. And basically, in that one, also with the other accelerators that we kind of talked to although we didn't apply, our motivation was to get access to the client. So that was the number one motivation.

• Access to client • Focus on

specific CA

• Client Access

SU3 (1:17)

In theory, yes. So, the question was always the kind of the access to the potential customers. So that's kind of the upside that you get when you join. And then of course, the accelerators, they ask for equity money. That can be the downside. What you end up doing is to try to balance your current situation with how much it costs and what is the perceived prospects for attracting clients through the accelerator program. We've talked to a number of accelerators in [country] as well. I mean, [the corporate] is also in [country] but for the independent accelerators in [country] or in [country], we figured out that their question for equity is unrelated to the success. It's not like a success fee or anything. When you go into an accelerator, they tell you that they want to have a convertible loan style of option on your equity or flat payments. You have to give this away even if the accelerator doesn't work. If it doesn't provide you with anything at the end, that's a difficult selling proposition, I think. So, in terms of, joining the corporate accelerator of [this corporate], the idea was quite simple: They didn't ask for anything and for that we will get access to [the corporate]. It sounds like a reasonable deal. So, your question was would we have joined other accelerators which are not corporate accelerators? Yes, but we didn't see the prospects as that good because the outcome is not guaranteed at all. Actually, it's difficult to judge how good how well connected they are. If they can really get through it with you to the clients or to partners. At the same time, you don't have to give away anything even if it doesn't work out.

• Access to customer • Giving equity • Assessing benefits of program • Success fee • Independent accelerator offers convertible loans • No guaranteed outcome • Uncertainty of partnership & network available • Regular AC asks for equity no matter the result • no guaranteed outcome • CA no equity necessarily • CA = nothing to lose • Difficult to estimate the network beforehand

Table 3: Merged Highlights of Single Researchers

Coding Table

The coding table (see Table 4) is the result of the analytical induction (Preissle, 2008). The coding process itself represents a filtering of the relevant content from the single interviews and a clustering of statements from different interviewees. Accordingly, the creation of the coding table and the transfer of the codes from the single interview into the table, is the first time that the content of the interviews was cross-checked. Moreover, the development of the framework in the coding table happened incrementally and with the intention to identify cross-case patterns (Eisenhardt, 1989). Based on the codes of the first interview, initial clusters were built. These first clusters were filled with codes from other interviews, or a new cluster were created whenever a cluster didn’t exist. Consequently, these clusters turned into sub-categories after realizing in which direction further research would probably proceed. Table 4 shows an extract of the final coding table. This table includes only relevant codes and sub-categories. In total, 344 relevant

codes were created, which turned into 39 sub-categories, 17 categories and 5 main categories. Codes and clusters which are out of scope (e.g. facilities), or just confirm known aspects (e.g. definition of CA) were not included in the final coding table.

Codes consist of subjective statements from the interviewees. However, the sub-categories were labeled with a neutral heading in order to collect all different perspectives under one sub-category. For the creation of the categories, this subjectivity was used to label the categories with a heading, that contained a tendency or represented a so-called ‘action title’. This tendency or call-to-action relied on the underlying codes of the sub-categories. If a tendency was identified as highly relevant or influential, they were considered in the creation of the header for the categories (see Table 4). This procedure was useful in the analysis to better see trends, connections and contradictions.

Respon-dent Codes Sub-Category Category Main Category

CA3 Strategic goals: increase sales, company value, and shareholder value Corporate main goals CA serves corporate strategy Purpose

CA4 Merging strategic focus; customer journey and unmet needs

CA3 Contradiction of CA with corporate (innovation) CA1 Accelerator startups should have impact within the next

two to five years

CA1 Venture arm investments are strategic investments for the next 5 to 10 years

CA3 Many things transitioned into “services”

Transformation of markets

CA3 Sharing risk of unknown

CA3 Transformation from today’s business model to future business model

CA3 Pushing towards innovation while remaining stable at the core is key

CA3 Transformation is a constant pace of change which will never be done

CA3 Shorter response rates in corporates needed

CA3 Old school customer-supplier relationships are broken up CA3 Strategic impact by seizing new markets (measured in

EUR billions)

CA3 Open market development

CA4 Strategy: Challenges tackle US, German and French market with the option to afterwards be rolled-out in Europe and China

CA5 Evolvement of the goals of the accelerator

Strategic Change

CA2 New strategical direction through the diesel crisis CA2 Strategy is to not make revenues with the hardware but

also software and everything around the car CA2 Ask for honest feedback from startups

CA2 We must develop and we are far away from the finish CA3 In CA, strategic relevance is most important

CA4 CA is screening the market and seeing what’s possible and how to solve it

CA4 Goal of the Accelerator: Bring in top talent; relevant solutions to challenges; empower expert review teams to make data-driven decisions

CA4 Commercial oriented CA, meaning that there is a clear distinction between R&D (technologies) and CA (solutions)

SU3 Development of a new program focusing on commonly develop ideas with startup and corporate together which serve the corporate purpose only

Table 4: Extract of Coding Table

3.5.2 Trustworthiness

In order to provide a scientific work with a standard of quality and the verification of quality for the qualitative findings, several aspects regarding trustworthiness needs to be ensured (Guba, 1981). These aspects are credibility, dependability, conformability,

transferability, and authenticity. Firstly, credibility refers to ensure that the individuals

participating in the research are identified and described properly. As stated before, the interviewees were selected purposefully based on their experiences and positions. The principle of triangulation was also respected in several contexts. For the selection of the interviewees, not just CA manager were chosen but also startup founders who participated in the observed CA programs. In addition, triangulation was considered when discussing on codes until a consensus was found. Dependability emphasizes on the stability of the data over time and under different conditions. Explaining the decision trail in this study helps future researchers, to build on this research and assess how the data collection depends on the research participants. Conformability implicates objectivity. Accordingly, the findings accurately represent the information given by the interviewees. As shown in the coding process illustration in chapter 3.5.13.5.1 and the complete coding table (figure 16 -20 in the appendix) proofs that the data is not invented but bases on real conducted interviews. The aspect transferability is congruent with generalizability. One strength of our sampling is that we conducted interviewees with managers and participants of CAs of leading multinational corporates, which also have been one of the first implementing these programs. They have the experience and act as a role model for other corporates considering to establish a CA. Thus, our findings can be applied to new concepts and also to other existing corporates. For existing CAs in particular, it is important to know that the five CAs investigated are active in three different industries. Lastly, authenticity refers