Entrapped Between State and Tradition

The Effects of Graffiti and Street Art on the Jordanian Society

Aram Tarawneh

Faculty of Culture and Society Master of Science, Urban Studies 30 Credits

August 2020

2

Acknowledgment

I would like to first thank my supervisor, Carina Listerborn, for the constant support that she provided in order for me to finish the thesis. Secondly, I would like to thank my Mum and Dad for their support and encouragement throughout the master program.

3

Abstract:

The last seven years have been a transformation point for graffiti and street art in Jordan. Due to the constant inequality that women face in Jordan, graffiti and street artists grabbed the first opportunity presented to them in order to address these issues, when the Baladk Street Art Festival took place in the capital of Jordan, Amman. They used this festival as an opportunity to spread awareness and tell stories related to inequality as well as claim their rights. Resistance from conservative groups in the society towards these murals resulted in more restrictions from the municipality about the content of them. However, artists did not back up and fought their way to keep their art on the city’s walls, but they had to work harder in order to disguise the messages they wished to send to the public. Social change was used as the main concept to follow in this thesis in order to arrive at a conclusion that shows the change that had taken place in Jordan due to graffiti and street art, especially social change regarding ideas and social movements as well as political processes. In order to get the people’s, the municipality’s and artists’ perspectives, qualitative methods were used such as interviews and a survey. Results showed that the municipality's position on the effects of graffiti and street on the society as well as the strict regulations are partially the same. In the meantime, interviews with artists and the survey showed the struggle the artists go through when painting and also the change in the people’s behavior that occurred in the last seven years, from the start of the project until now. The survey’s results showed that most of the people understood the exact meaning of the murals and some respondents interpreted the messages according to their experiences. Therefore, it was concluded that graffiti and street art can serve as a prospective tool to drive social change in the Jordanian society, yet not solitarily. Different aspects, such as people’s behavior, shifting norms as well as a change in laws and policies need to work hand in hand in order to achieve the desired change and cause a social and cultural evolution.

Keywords: Graffiti, street art, social change, mural, women’s right, equality, Jordan, Amman

4

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Introduction ... 5

1.1 Research question and aim ... 7

1.2 Thesis outline ... 7

Chapter 2: Background ... 8

2.1 Graffiti and street art in the Middle East ... 8

2.2 Graffiti and street art in Jordan ... 9

2.3 Feminism in Jordan ... 10

2.4 Graffiti and feminism in Jordan ... 13

Chapter 3: Theoretical framework ... 15

3.1 Social change ... 15

3.2 Street art in public spaces and their role in initiating social change ... 18

3.3 Feminism and street art in Amman ... 23

Chapter (4): Methodology ... 25 4.1 Interviews ... 26 4.2 Survey ... 27 4.2 Limitation ... 30 Chapter (5): Analysis ... 30 5.1 Interview analysis ... 30 5.2 Survey analysis ... 36

Chapter 5: Results and discussion ... 44

Chapter (7): Conclusion ... 47 7.1 Future research ... 48 References ... 50 Appendix (1) ... 54 Appendix (2) ... 55 Appendix (3) ... 57

5

Chapter 1: Introduction

Contemporary graffiti started back in the 1970s in New York, where individuals used to tag their names and their crew names on buildings, walls, subway trains, et cetera, where it was a part of the street subculture of hip hop (Duncan, 2019). Not long after, graffiti started to be utilized as a method of protest and resistance such as the socio-economic crisis in New York and the student revolts in Paris, which started to link graffiti and street art to more serious topics such as politics, economics, culture and many more (Austin, 2001, as cited in Taş, 2017). At that point, people started calling it street art due to the fact that people began recognizing it as an effective urban art (Duncan, 2019). As recent as this year, with the Black Lives Matter movement, graffiti and street artists took the initiative to write and paint murals all over the world to show solidarity. In that, the artworks become a means of story-telling and symbols of resistance to the system, as well as expressions of support to the movement, in reference to the murals painted of George Floyd.

Notwithstanding, graffiti and street art are not necessarily a reason for revolutions and heated debates but they, most of the time, call for “compassion and unity amongst society members while still touching upon key issues of the contemporary world” (Zu’bi, 2018). One particular movement that used this type of art as a peaceful claim of their rights is the feminist movement. Graffiti and street art have been used to spread feminism onto the streets and from there to the society (Nour, 2017). It also helps to challenge gender norms and boundaries in societies and between disciplines (Millner, Moore and Cole, 2015). An example on that is the popular feminist slogan “A woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle”, which was first tagged on a wall of a bathroom by a woman. This indicates that “[…] Writing on a wall can actually promote social change” (Pabon, 2012, 0:20). The previous example demonstrates that movements as immense as the feminist movement start small and take a consistent effort from people all over the world in order to make it as great as it is right now. That shows that social change through graffiti and street art begins with small steps in order to have a full effect in the future. Nour (2017) also explained that graffiti and street art in the feminist movement can help inspire women all over the world to demand rights and equality and educate people about women’s rights as well, because this art is a powerful medium to show the world that women are insisting on their rights after many years of inequality and ignorance. One of the first graffiti artists to paint and write about the inequality women go through is Lady Pink, who was one of the trailblazing female graffiti artists and was active in New York in the 1980s (Mu’min, 2013). Another graffiti artist, Tatyana

6 Fazlalizadeh, who dedicated her art to feminism, where she started a ‘anti-harassment campaign’ that was called “Stop Telling Women To Smile”, for which she interviewed women about their experiences in the streets and then hanging those experiences on posters in the streets in order to raise awareness and address gender based street harassment (“Stop Telling Women to Smile”, n.d.). So, as early as the 1980s, graffiti and street art have been giving marginalized people a way to express their needs and giving them the chance to be heard by the society and the state. Hence, Nour (2017) argued that “feminism was among the most important causes that graffiti has helped”.

However, these processes occurring in the Western world have not been reflected in the same way in the Middle East. Graffiti and street art in the Middle East have been mainly associated with war, protests, revolutions, and the Arab Spring, which will be further discussed in the background chapter. Being predominantly associated with those topics and having street art and graffiti that target other important issues, such as women’s rights and equality, had a rocky start. But in 2013 in Jordan, a street art festival by the name of Baladk Street Art Festival launched and gave the opportunity to artists to use their art beyond canvases and onto walls. This festival helped the beginning of a new approach to graffiti and street art by raising awareness about topics such as feminism and equality because “walls could be a direct reflection of the community’s needs” (Nour, 2017). Despite this progressive momentum a few years ago, some groups within the society, as well as the municipality, impeded the dissemination of this art form and partially continue to do so nowadays. Street art and graffiti that spread awareness about specific topics are being controlled both by the municipality imposing criminal laws and punitive regulations and restrictions, and by conservative groups that do not agree with what is being portrayed on the walls and therefore vandalize them or report them to the municipality, which eventually removes the mural in question. In this thesis the terms graffiti and street art are used interchangeably, as both, street artists and graffiti artists, share the same methods and the same space and hence are subjected to the same problems and rules (Gentry, 2008), especially in a controlling society as Jordan. Furthermore, different artists, who were interviewed for this thesis, referred to themselves as both graffiti artists and street artists. Albeit, this thesis will focus on murals, as it is the most popular form of graffiti and street art in Jordan.

Also, to note that, for the purpose of this thesis, classic gender binary of male and female is going to be applied. That is due to the fact that artists and the general public in Jordan do not yet identify other than both genders. It is possible that there are people, who identify otherwise, but for the current situation in Jordan, it is not evident.

7

1.1 Research question and aim

The main purpose of this thesis is to discover if graffiti and street art is helping movements in Jordan such as the feminist movement and if it is one of the factors to ensure social change in the future, through discussing first the concept of social change and then comparing it to the situation in Jordan. This thesis is aiming to investigate whether graffiti and street art are changing the Jordanian society or not. This is due to the fact that this type of art is recent in Jordan, therefore it is a new approach to tackle topics and issues in order to verify if it can achieve social change in the future. Against this backdrop, the main question explored is:

Are graffiti and street art paving a path for a change in society as well as the law that might help eradicate the unequal norms and gender-normative traditions that women are being subjected to in the Jordanian society?

Another question can be raised here, which involves the possibility of graffiti and street art being a part of a social movement in the future that might lead to social change. Due to graffiti and street art being recent in Jordan, it is still too early to answer that question in the span of this thesis. However, getting a result from the main question of the thesis might give a hint of how the situation might be in the future and the possibility of getting graffiti and street art involved in a social movement to a better future in that field.

These questions were raised when reading on the effects of graffiti and street art in the Middle East and especially the role it played in the Egyptian revolution in the Arab Spring as well as the Palestinian case and other Middle Eastern cities and countries. Since this type of art was introduced in the Middle East in a context of war, revolutions and protest, the question was raised in order to research whether it will have the same effects if applied in different aspects such as women’s rights and equality.

1.2 Thesis outline

The next chapter is going to give a background about the history of graffiti and street art in the Middle East and in general, and its outset in Jordan in particular. Moreover, the feminist movement in Jordan will be discussed, and how graffiti and street art have been incorporated within it in order to spread it within the kingdom.

Chapter 3 is targeting the theoretical framework that is going to help answer the main question. It is discussing the theory of social change and how it can be linked to graffiti and street art in order to cause social change in the Jordanian society. It will also explain

8 more on the involvement of graffiti and street art in the feminist movement in order to demand change and rights.

After explaining the theoretical framework and discussing the concept of social change, the thesis then explains in chapter 4 the methodology that was used in this thesis in order to get the public’s and the artists’ point of view on the field of graffiti and street art and their effects on the society. Followed by that, an analysis of the methodology, interviews, and a survey, will be presented in chapter 5.

Chapter 6 is elaborating on the results of both the interviews and the survey and their link to the theoretical framework.

A concluding regard of the thesis as well as a further future research that could be done on the same topic, will be explained in chapter 7.

Chapter 2: Background

Before starting to write about the impact of graffiti and street art on the social life and how it might trigger change in the core of the society and the possibility to lead to social change, this section will address the situation of graffiti and street art in the middle east in general and in Jordan specifically and look into how this type of art began and what was it like before the growth of graffiti and street art that is roaming the street of Amman nowadays. This background section will illustrate the cultural, political, and social situation in the Middle East, focusing on Jordan, and how graffiti was affected by that situation and show what made street art and graffiti in the Middle East as it is now. Also, since this thesis discusses the involvement of women in this type of art and specifically about how street art and graffiti are targeting topics such as equality and women’s rights and the role of feminism, this section will discuss feminism in Jordan and the situation of Jordanian women, which triggered the use of graffiti and street art for sending messages to the public in order to ensure change towards these specific topics.

2.1 Graffiti and street art in the Middle East

Graffiti and street art in the Middle East have started to appear in the past two decades on the walls of different cities in the area. One thing to be noticed is that this type of art became popular in these cities and countries as a result of revolutions, wars, civil war, et cetera. The example of the Gaza Wall and the Separation Wall in Palestine, which are being used to write the history of war, the different revolutions, and the political views (Peteet, 1996) represents how street art and graffiti were depicted in the Middle East. Another example is Egypt with graffiti being one of the most used methods in the 2011 revolution against the regime, for people to express their feelings and use the walls as a

9 news stand due to the lack of trust in the media (Taş, 2017). The walls of Beirut are filled with graffiti that are political in nature and are still being used even after the war in Lebanon was long gone (Najjar, 2015). Another example is the “Syria Banksy Project” from 2019, which also addresses the civil war and political instability in the country (Riziq, 2019). It is evident that graffiti and street art in the Middle East are being used to incite revolutions or are political in nature. That is why it made it harder for other Middle Eastern countries to start a base for graffiti and street art as a way to achieve societal change peacefully and not for it to be seen as resistance to the government or the political situation in the country.

2.2 Graffiti and street art in Jordan

Earlier on in Jordan, graffiti and street art were depicted as either people tagging, writing random words, phone numbers, love confessions or as art that is provided by the government that is only related to the Jordanian nationality and to show loyalty and praising the country as well as the monarchy. Even though the art provided by the municipality is public art or street art, it has been connected entirely to the country and the monarchy and it might be the only type of public art that the people in Jordan grew up seeing and drawing. This may mean that introducing other types of graffiti that address actual issues and not only to show loyalty to the monarchy, might be rejected or found strange by a huge population at the beginning.

In Jordan specifically, artists didn’t use art in the street in order to send messages about morals, the inequalities or any political statements to the public because it was and is still considered a crime that will be punished by fines or even imprisonment. This is due to the fact that Article 319 in the Jordanian Penal Law states that anyone displaying any type of drawing, images or any type of art that is offensive to morals, the monarch and traditions of the country, will face punishment (Penal Law and its Amendments, No. 16, Year 1960, Subject No. 476, Article No. 319).

In the 1960s, Jordan was going through a transition where the Islamic group of Muslim Brotherhood started infiltrating the Jordanian society in order to restore the country to its religious state before the British occupation. The Muslim Brotherhood had different agendas such as bringing religion back into politics and following the religious laws instead of more modern and international laws (Al Shalabi, 2011). Many of their followers were considering anything that is foreign in nature, be it art/graffiti/ feminism, a Western topic that they must fight due to their perceived misalignment with religious laws and a religious way of living, and a fear of values deemed as inappropriate being entrenched into society. The situation stayed like that until 2013 when Al-Balad theatre launched a project called Baladk Street Art Festival in collaboration with international

10 organizations as well as the Greater Amman Municipality, that invites artists from Jordan and the rest of the world to participate. Each year they have different topics for artists to paint and write on selected walls around the city of Amman. The start of this project was both by a demand from the artists as well as an initiative from the municipality itself. The artists requested free spaces to paint on without the murals being removed, said Maha Hindi, a graffiti artist based in Amman, who participated a couple of times in the Baladk festival (2020). Furthermore, the municipality aimed for branding Amman as the next art destination, said Laila Ajjawi, an artist based in Irbid, the second biggest city in Jordan (2020).

Even though it is now allowed to participate in this type of art in the streets of Amman, the artists wanted less attention from the government and not the other way around (Zu'bi, 2018). This might go back to the fact that the government has to regulate and monitor every single art piece before it is being put up, which explains why “painting walls with permission has meant painting less” (Pabon, 2016). They give artists a minimal amount of freedom when choosing what to paint and highly restricts their creative freedom so that they cannot reach out with their messages. This might be the case since, beside the first Penal Law, the government requested an amendment to the Electronic Crime Laws regarding hate speech, expanding it to include “any word or action that incites discord or religious, sectarian, ethnic, or regional strife or discrimination between individuals or groups” (Human Rights Watch, 2017), which even inhibits artists in posting any ‘offensive’ content on social media even if it was a picture or a drawing, which limits the artists’ freedom of expression. Despite all of that, artists still found a way to be both non-offensive to the constitution of the country and be critical on topics such as women’s rights, equality and many more.

2.3 Feminism in Jordan

Inequality and violence towards women in the Middle East were practiced centuries ago but unlike the rest of the world, where women stood up to these inequalities and fought for their rights, it stayed the same in the Middle East. This is linked to when Jordan was released from the British occupation, movements in Jordan such as the Jordanian national movement and the Muslim Brotherhood started to form in order to change the political and social situation in the country after it got its independence (Anderson, 2005). Due to these movements, whose participants grew up in an occupied land and rejected the British influence after the occupants left, the Jordanian Law and Constitution was formed. The Jordanian law was formed in the 50s and 60s and is still in full use nowadays with many laws being unequal to women (Anderson, 2005). Women in the Middle East are facing what is called a “double jeopardy” (Sakr, 2002) which means that they are not only limited in their political and civic participation but also

11 experience hardships due to the patriarchal structure of society, where they are not the ones who decide to work, to travel or even whom to marry but their male guardian (Sakr, 2002). This indicates that “[…] discrimination against women is embedded in legal systems and social customs” (Sakr, 2002).

These practices are still being perpetuated in Jordan and the Middle East, which means that when people start demanding change and social justice, the conservative groups just justify it as an intrusion from the West. This demand was faced with opposition and resistance. Because of that, the claims from the conservative groups are that they are “resisting an intrusive and alien culture flowing from the West that threatens to encroach on the patriarchal order” (Tripp, 2013).

Charles Tripp’s (2013) book that is called “The Power and the People: Paths of Resistance in the Middle East” represents the situation in the Middle East and how conservative groups deal with any ‘Western’ topic such as equality and feminism. In different parts in the Middle East, the people who defend the practices that are unfair and unequal, while others are struggling to abolish them, see themselves as the ones who resist “a new hegemonic power that wants to dominate the globe” (Tripp, 2013). To these defenders, this ‘hegemonic power’ can be portrayed as secularism, liberalism, capitalism or any other “power of the West” (Tripp, 2013). They see that this power from the West is the foundation for the plans to dominate and occupy the Middle East that started 200 years ago. Tripp explained that, 200 years ago these invasions were simply “imperial conquests” (Tripp, 2013) but after that and especially in the post-colonial decades, Middle Eastern economy, the culture and society were involved within the Western power and were heading towards globalization. Because of that Tripp (2013) said that:

those who champion ‘tradition’ – however interpreted – see themselves as the unwilling subjects of a world order that they have not made, have no control over and that appears intent on marginalizing them and their values” (P. 178)

With that being said, some people look at feminism as a Western concept that might bring new and radical ideas to the cultural and religious traditions that have been practiced for many years. They see it as an intruder to their private lives and societal values. These groups oftentimes will distort feminist ideas and intentions and portray them as defiance of culture and religion. Nour (2017) points out that “religions and traditions in the East are still so strong and dominating that we can consider them as an unwritten constitution”. So, even though the law criminalizes some cultural practices such as honor killing and underage marriage, men are still practicing them knowingly. Their claim is that the state and the government are giving in to the term ‘globalization’ and are being corrupted by the West. This to them, means that their traditions and

12 extreme religious ideas are going to be obliterated (Tripp, 2013). Therefore, the conservative movements resist these modern trends, and the government affirming their concerns by posing lesser jail sentences to those who practice illegal cultural practices, due to the fear of demonstration to change the government which can lead to disastrous political changes as it has been the case in the Arab Spring (Tripp, 2013). Nadia Shamroukh, the director of the Jordanian Women’s Union (JWU) explained that women who are feminists do not see themselves as feminist but as activists (Cuthbert, 2017). This is due to the fact that every time the topic of feminism comes up; they have to get defensive and be prepared for criticism from different parties, such as ridiculing their values and arguing against everything they stand for. That is because “many in Jordan see feminism as a taboo subject, and a threat to the social and religious order” (Cuthbert, 2017).

Different organizations want to disseminate and explain the concept of feminism to women in Jordan and to clarify their rights for them, but at the same time they receive harsh backlash from the society and political parties. According to data collected in a paper called “The State of Jordanian Women's Organizations - Five Years Beyond the Arab Spring” by Peter A. Ferguson (2017), a big portion of the activities initiated by women’s organizations in Jordan are directly overseen by “elites with strong regime ties” (Ferguson, 2017). This goes back to the fact that these elites are legalizing the liberalization strategy for these activities while attempting to make sure that these activities will not develop into movements that might defy the Jordanian regime (Ferguson, 2017). This strategy entails that the state will provide the organizations with tools and rules to service women, like workshops, but will undermine their roles as a political actor, that might demand change in the system and thus “challenge the regime” (Ferguson, 2017). These restrictions are explained by what Sonia Alvarez (1989), as cited in Ferguson (2017), called “NGOisation”, which means that in order for these organizations to become a legal entity, they are given “a narrow set of policy options that end up equating empowerment with overcoming marginality from the market, while disregarding the multiple oppressions faced by women” (Schild, 2000, as cited in Ferguson, 2017). This explains why women’s organizations are usually forced to focus on “unsustainable programs” rather than fight for certain rights that might require a political change, in which they are not allowed to participate in or they will lose their legality (Ferguson, 2017). Hence, Ferguson (2017) concluded:

“The strategy worked, insofar as the survival of the regime was never seriously in doubt. The ability of women’s organizations to effectively seek change in the status of women was impaired by the elite-driven interests of their leadership as

13 well as the inability to expand their programmatic focus to issues more concerning to the broader female population in the country” (P. 66)

In order to fully understand the situation, the next paragraph will give a brief context of the Arab spring and how it affected Jordan. In 2011, in the midst of the Arab Spring, people in Jordan as well went out and protested and demanded change but the adjustments that they were requesting were more towards the economy and some political changes and not to overthrow the monarchy. The people demanded the “sacking of the prime minister” and the adoption of a new election law (Cullbertson, 2016). Throughout the year of 2011, protests recurred and still insisted on the same demands, yet not comparable to the claims made in the neighboring countries. After the Jordanian protesters saw how the situations escalated in Syria and Egypt, they thought “even with the problems in Jordan, the alternatives were worse” (Al-Sharif, 2013, as cited in Cullbertson, 2016). They did not want what happened there to happen in Jordan. Also, the King himself wanted to avoid the escalation of events in Jordan, and eventually met the protestors’ demands by “sacking the prime minister, prosecution of high-profile corruption cases, constitutional amendments, government salary increases, the creation of additional government jobs, and early parliamentary elections” (Cullbertson, 2016). On the other hand, the Jordanian tribes played a huge part in the Arab Spring and the stability of the situation in the country. They help sustain the political stability as well as the social relations in the country (Kao, 2015). They have their rules and laws and most of them also go side by side with the traditions and norms that are perpetuating patriarchal societal structures such as honor killings. Going against their rules and traditions might mean that the state will lose their support, which is not in favor of the state.

Concluding this part, it can be stated that the regime’s fear of women’s organizations having a political stance and voice that might lead to political movements, such as the Arab Spring, and the fact that people with ties to the regime are responsible for such organizations, is the reason why the politicization of women’s organizations in Jordan is stagnant (Ferguson, 2017).

2.4 Graffiti and feminism in Jordan

Research published hitherto on the role of female artists in the graffiti scene can be identified as Western-centric, failing to reflect the reality in the Middle East with its specific contexts. In spite of that, Jordan followed some footsteps from feminist events around the world such as the “Femme Fierce” in London (Nour, 2017) and implemented something similar in Jordan, such as the Women on Walls, a graffiti initiative for Arab Women to paint murals that empower women around the Arab world and they had a

14 regional street art festival in Amman under the theme of “From Fear to Freedom” (“WOW- Women On Walls”, n.d.). Another Initiative was called “Break the Silence” campaign by the organization artmejo (“Break the Silence: Submission Highlights”, n.d.), where female artists were invited to submit online sketches of different topics concerning equality and women’s rights. Last year the artists were asked to present sketches of a survivor after she was subjected to domestic abuse by her husband. It was a form of a competition, where the sketch that was chosen to be the winner was painted on a wall in Amman.

It is well established in the research literature on female graffiti and street artists (Gentry, 2008; Pabón, 2013; Pursley, 2012; Nealon, 2018) that this genre is still male dominated and that female artist struggle to integrate themselves in that world without being judged or/and harassed for what they are doing. This previous research elaborates on how female artists fight to become dominant in this art field and how they leave their mark for everyone else to see.

The difference between the premises that this previous research is based on and the situation of graffiti and street art in Jordan is that in Jordan, as mentioned before, graffiti and street art did not exist and was not a dominant field of art before the beginning of this decade. So, when the government allowed graffiti and street art and the Baladk Street Art Festival began, artists, both male and female, took the opportunity alike, without any gendered competition of dominion in the field. The artists, who want to participate in the Baladk Street Art Festival are chosen according to their art and not their gender. A committee in the festival assesses art sketches anonymously and selects the artists purely on their work (Zu'bi, 2018), which allows for a more equal and fairer curation. With this removal of potential gender biases, it is noteworthy that, according to the Baladk participants in one of the annual festivals, the majority of the participants were women (Baladk, 2018).

In this context it has to be understood that what is acceptable as feminist graffiti and street art in the Western societies differs largely from what is barely acceptable in the Middle Eastern societies (Nour, 2017). Gender issues and demanding rights for freedom of sexual expression through graffiti and street art are equivalent between the West and the Middle East, nevertheless, the public reception of art is different in the Middle East and the West. Traditions and religion are heavily rooted within the society. Therefore, explicit feminist street art might be viewed as problematic for some groups. Hence, these already extraordinary art forms have to convey their messages indirectly in order to “handle sensitive subjects in their street arts […]” (Nour, 2017).

It is against this backdrop of the discourse on street art and graffiti, and feminism in the Middle East in general, and in Jordan in particular, questions regarding a possible

15 change in the status quo have to be considered. The next chapter is going to focus on the concept of social change and its different types in order to investigate what type of change has occurred in the Jordanian society and how that change has been incorporated through graffiti and street art so far as well as exploring the possibilities on how it can be more included in the society.

Chapter 3: Theoretical framework

3.1 Social change

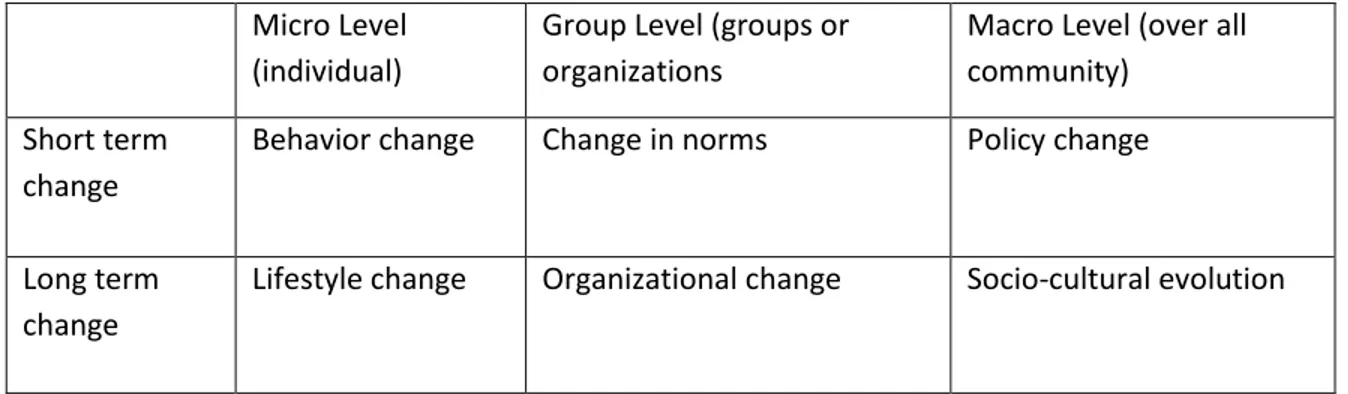

Social change is a wide topic and can be interpreted in different ways depending on the context it is based on. Social change can be applied to different fields such as environment, demographic processes, technological innovations, economic processes, ideas and social movements, political processes and so forth (Wilterdink and Form, 2019). In the context of this thesis, social change is targeting the ideas and social movements field, since the demands that are being represented on murals are targeting a change in traditions and how people approach topics such as women’s rights. Diani (1992) defined social movement as “[...] networks of informal interactions between a plurality of individuals, groups and/or organizations, engaged in political or cultural conflicts, on the basis of shared collective identities”. By comparing this definition to what graffiti and street art is trying to achieve, they share the same aspects such as being informal, and involving a group of people targeting specific aspects of a society such as the cultural and the social aspects which will lead to targeting topics as women’s rights and inequality.

Before exploring the discourse on social change, the term society, in this context, needs to be addressed as the understanding of change employed here is a societal phenomenon, in which the society consists of various layers defined by different aspects. According to Sztompka (1993), the first two layers of society are the ideas (beliefs) and rules (values and norms) which make up the cultural dimension. The other two layers are actions (interactions) and interests (opportunities) which make up the societal fabric. These four layers combined make up what is called the “socio-cultural field” (Sztompka, 1993). Each of these layers undergo changes constantly and these changes can be the transformation of ideas, the disappearance and appearance of values, norms, morals and ideologies, the acceptance or rejection of new norms, rules, and values.

These changes can be explained by the definition of social change “social change, accordingly, is conceived as the change occurring within, or embracing the social system. More precisely, it is the difference between various states of the same system succeeding each other in time” (Sztompka, 1993). According to this definition, social

16 change targets the social system that includes the social dynamics of the system, which means that it triggers the development and progress of a society in order to move on from previous social thinking into a new social thinking. According to Sztompka (1993) there are 6 different components of social change which are: 1- the ultimate elements which involve the human population. 2- Interrelations among elements which includes the relationships between humans and their interactions. 3- The function of elements in the system as a whole which can mean the different roles that individuals play as well as the actions taken by individuals in order to change the social or preserve it. 4- The boundary which involves inclusion or recruitment in different groups 5- The subsystems which are the different groups and sections of a society 6- The environment which means the natural conditions. In accordance with these sections, street art and graffiti can be discussed from all of these angles, but for the purpose of this thesis, the focus will be on the interrelations among elements and the functions of elements in the system as a whole. Street art and graffiti might possibly be the driver to social change and artists might be the individuals that initiate that change. According to Sztompka (1993), the possible changes within the social system involve 1- Change in structure which means the appearances of equalities and inequalities and the emergence of new relationships. 2- Change in function which means the role individuals play in order to insure this change, meaning that the artists that lead a normal life and have different jobs can change their functions from their day jobs and use street art and graffiti as a tool to change the dynamics of a society after work or in their free time. Furthermore, social change is driven by individuals and depending on the effect that they are trying to accomplish and the kind of change they are trying to insure, they will also change and modify their choices and motives in order to achieve the effect they are aiming for. This definition of social change enables the elaboration of art as a driver for change, as graffiti and street artists use their works to address inequality and marginalization, especially in a context like the Jordanian one, where unequal gender-normative traditions and structures heavily limit marginalized groups’ impact on the society and their right to change these inequalities.

Art that is intended to discuss these issues will focus on the community and the society as a whole which can facilitate empathy in people that might pave the way for social change and life improvement. An example for that is Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy (2017), who said in an article about her involvement in targeting, through art, the crimes against women in Pakistan “art can directly empower the most vulnerable members of society” as well as “creativity and individual freedom can generate new opportunities” (Chinoy, 2017). Her movies about the violence committed towards women in Pakistan have triggered change in the law and the severity of punishment towards the people

17 who commit these crimes, which means that her type of art had a major change both in the social structure as well as the legal one. If art exists in a society where artists have the chance to send out messages, people will be more aware of the lack of rights for vulnerable individuals in the society such as women. This is why, nowadays, with the increase of graffiti and street art in the Jordanian society, the current situation may shift and artists, from both genders, can participate to send out messages to the people that an alteration might be taken place or that the artists are constructing a new platform to demand change. Street art and graffiti can be used as a tool to communicate with the people, just as Jessica Pabon (2012) said in a TED talk “graffiti is a form of writing and writing is fundamentally about communicating. So, these writers are reclaiming public space, they are stating their presence […]”. Further she quotes a Chilean graffiti crew member by the name of Bisy that explains how graffiti can be a driver for change:

“Painting your voice in the street becomes an act of courage and perseverance, without realizing it you transform the city, along with transforming yourself… transform everything around you” (2012, 10:05)

This change might also be able to bring feminists and women activists to the street in order to let people recognize the reason for their activism and the rights that they are demanding and to let the community acknowledge their presence in the society (Nour, 2017).

This type of social change might eventually lead to resistance from parts of the society. As mentioned in the last chapter, a majority of people in the Middle East resist any type of Western concepts, street art and feminism included, and this will form a type of resistance from conservative groups, such as taking down murals or reporting murals to the municipality as being offensive to the status quo. However, there is another type of resistance that can stem from the artists themselves. The fact that these artists started painting murals talking about inequalities and demanding rights is a type of resistance itself but directed at the social norms that are already being practiced in the society. Just as Charles Tripp (2013) explains it:

“Thus, there are two registers of resistance. One draws upon universal principles of citizens’ rights to fight against the discriminatory practices of social institutions and the laws of the state. The other portrays any such campaign as part of a larger imbalance in a world where Western power works against the identities, religions and cultural traditions of Muslims, Arabs or other subordinated peoples” (p. 179)

The reformation of these traditions and norms might be initiated through artists from their exposure to the concepts of modernization, feminism, human rights, and women’s rights to be specific.

18

3.2 Street art in public spaces and their role in initiating social change

Considering street art in public spaces necessitates the discussion of the socio-cultural perspective of public space. According to Borja and Muxi (as cited in Ortiz, Garcia-Ramon and Prats, 2004), public spaces from a socio-cultural perspective can be defined as spaces “of interrelation, social encounter, and exchange, where groups with different interests converge”. They explain that the design and creation of public spaces serves as a vital element to encourage social interaction, to increase the quality of life and to minimize age and gender exclusions. In the field of street art and graffiti, the public spaces that are used to show the art are what is called the “everyday spaces” (Mean and Tims 2005). The locations of street murals are situated on housing walls, stairs, and sidewalks, which people use and see on an everyday basis. Everyday spaces in Amman are used by everyone, women and men alike, and since Amman is a city highly dependent on cars, the murals’ locations inside tunnels, on tall buildings and walls are strategically selected in order to increase exposure. In nowadays Amman, these everyday spaces are being used as a platform for artists to show their art and to resist the norms and traditions as well as to give the voiceless a voice to fight for their rights such as women. Street art and graffiti in the public space can be “vital to social and cultural movements that seek to challenge dominant orthodoxies” (Calhoun, 2005). Changing the social system and “challenging the dominant orthodoxies” starts with the artists in that everyday space, where a group of individuals who share the same experiences, can be a part of the change (Tripp, 2013). Change starts in that time and space, where the main goal for all of the artists is to participate in this type of resistance in order for social change to unfold. By doing that, street artists establish a sense of belonging to that public space and will provide the people the chance to feel the same sense of belonging to that space and to the art that is there that relates to their social exclusions. By saying that, a public space, in that sense is not only its geographical location, but what the artists make of it in order to give people a space to relate to (Albet, 2001. As cited in Ortiz, Garcia-Ramon and Prats, 2004). These murals and art pieces connote the public spaces they are occupying with particular meanings for particular individuals due to the actions performed within it by the artists.

This gives these spaces a “dualistic quality” being related to an individual’s experience and a space or “object” in the world (Entrikin, 1991).

After establishing that some of these everyday spaces are related to people’s experiences and not merely geographical locations, a discussion is needed on the possibility of those spaces to facilitate social change, especially for the excluded individuals, through street art and graffiti. Street art and graffiti are a “vital instrument” (Gleaton, 2012) to demand social change in communities, where many voices are left

19 unheard. It visualizes protests for everyone to see in order to empower those who are marginalized and excluded (Gleaton, 2012). That way people may become involved in the process of change and it gives them the opportunity to be a vital part in what is going to be placed on walls (Lewisohn, 2008). Also, it will trigger dialogue between people and motivate people to ask questions. Individuals who walk by these murals are now acknowledging them and can interpret them as they please. In contrast to other sources of information, such as traditional news, which can be limited in terms of content and availability, street art and graffiti are available for anyone to see (Chaffe 1993, as cited in Gleaton, 2012).

However, a challenge that these artists face is the fact that it is always easier to acknowledge the aesthetic and the beauty of a mural rather than trying to decipher its intended meaning or it can be “[...] easier for the observer to assess the aesthetics of the work of art itself and the intentions of the artist than to be certain of the effect it might have on the spectators” (Tripp, 2013). The effects of this type of art on people are sometimes misunderstood and that might be connected to the fact that people are made to think decades ago that art is not connected to any aspect of a society (Millner et al., 2015), especially in Jordan, where the messages and meanings that target social society and the traditional norms are well hidden. But according to Lefebvre (1996) “[…]the future of art is not artistic, but urban, because the future of 'man' is not discovered in the cosmos, or in the people, or in production, but in urban society”. He explains that, when art is put at the service of a city it does not necessarily mean the beautification of the city through art but the appropriation of the urban, where the artworks serve as examples of progress. Lefebvre argues that using resources such as art, helps the integration of the urban society into that city. Lefebvre’s argument corresponds with how Gentry (2008) treated the city as “a living and breathing system created by those living in it” which can be linked to what Park and Burgess (1925) said, that the city is not just a ‘physical mechanism’ but is a part of a vital process of those who create it, being the people. Graffiti and street artists take the initiative to rewrite and reinvent the city because the “city is not a neutral space but reflects the values of its creators” (Gentry, 2008). Thus, especially in a society as Jordan, artists plan their art in a way that resonates with the experiences that the people go through in that urban society in order to help them focus on important topics such as women’s rights and equality. This can be achieved through quotes, poems, and idioms and thereby the artists themselves will create a new type of “visual idioms” (Tripp, 2013), which “[…] generate[s] a sense of identity by creating the visual reference points for shared historical memories” (Tripp, 2013).

20 Graffiti and street art as a tool for protest is situated between the poles of novels and unfamiliarity, and the ability for it to resonate with its beholders. Some murals in Amman that call for women’s rights and feminism use poems and idioms that people are familiar with in order to enable people to rethink the meanings behind these poems and idioms and linking them to what is being drawn (Tripp, 2013). Also, poetry “has always represented the highest literary expression for Arabs” (Capezio, 2017), which indicates that people in the Middle East are well attached to poems. An example for that is a mural (Figure 1) that was painted by the end of 2019 in solidarity with a woman, Fatima Abu Akleik, who was subjected to extreme torture, having her eyes gouged out by her husband. The mural consisted of a black and white portrait of a woman looking to the sky with a line that is repeated 11 times from a poem written by Saba Firas Al-Abadi, that translates to “Let your eyes be cast on the mountain tops”. This poem was written for the purpose of the “Break the Silence” campaign initiated by an online platform called Artmejo and the Embassy of the Netherlands in Jordan.

21 Art is meant for everyone, but the messages are for certain people. Some individuals will appreciate the aesthetic value of it while others will relate to the presumed meaning due to personal experiences, which might give them a chance to reconsider the status quo and eventually act upon that reconsideration. By accomplishing that, this kind of art can be an essential part in a resistance movement against the political and the social climate in the area, such as the graffiti used in the Egyptian revolution, which may create a “new, possibly radical aesthetic” (Tripp, 2013). According to these examples, graffiti and street art will eventually be a reminder and a slogan for resistance towards the “political [and social] status quo” of the city (Taş, 2017).

According to Gleaton (2012), graffiti and street art are not supposed to be unbiased and neutral or hard to interpret and it should be easy and simple to understand the message behind it so it can speak to everyone, whether they agree or not, in order to start “political [and social] dialogue[s]” (Gleaton, 2012). Banksy said that graffiti eventually wins because “it becomes part of your city, it’s a tool” (Banksy, as cited in Gleaton, 2012). But in the case of Jordan, it does not always win. It can be hard to decipher or be biased. A further difference in the Jordanian case is that artists have the permission to paint on wales to a certain extent. Sending messages or telling a story through graffiti and street art without taking restrictions and the culture in mind is deemed to be removed from the city’s context. An example for that is the mural that was painted as a memorial for an Egyptian LGBTQ+ and feminism activist Sarah Hegazi, who committed suicide after she was subjected to torture and oppression for coming out to the public as homosexual. The mural also had the words “but I forgive” written on it, referring to of the lines Sarah wrote in her suicide note. The mural was immediately reported to the municipality through a surge of hate speech on Twitter. Consequently, the municipality localized and investigated the mural, and not even 12 hours after the installation of the mural it was covered in black paint by order of the municipality. The anonymous artist who painted it, posted on social media platforms that they received a large amount of hate messages as well as death threads for what they painted.

22

Figure 2: Top photos: Sarah Hegazi Mural in Amman. Bottom photos: The Municipality’s response on Twitter

This example shows that the artists are using their right of free speech in public through their work that speaks to people in a different way, to show solidarity and establish a particular language for them to use in order to amplify the strength of a protest or a progressive idea. Artists can also use their pieces to tell a story about oppression and inequality in a way that keeps people informed about topics that most of the local news does not address. Sometimes a number of artists, just as the artist who painted the mural in Figure (2), look the other way when it comes to ‘taboo’ topics such as homosexuality and target the topic straightforwardly without any restrictions with an intention to amplify the message conveyed in order to normalize these topics and make art related to it acceptable (Tripp, 2013).

23 This example also reveals that the more the authorities try to destroy any works of art that defy the general status quo, the more it becomes apparent that they “have failed to establish their own version of the truth” (Tripp, 2013) regarding these topics. This exposes the opportunistic and contradictory stance of the authorities, as they on the one hand welcome art (as long as it serves their favored purposes of non-disruptive place-making and city branding), while on the other hand turn against the very same art, condemning and eradicating it in order to appease the conservative groups within society (Tripp, 2013).

Nevertheless, when artists use art in public spaces to protest, they pave the way for it to become a space of resistance. Tripp (2013) explains that when people start utilizing public spaces through controversial murals such as the example in figure (2), evidence of resistance is shown which indicates that there is a shift in power and that the current dominant power is resisted (Tripp, 2013).

3.3 Feminism and street art in Amman

As mentioned in the previous chapter, the context of graffiti, street art and feminism in the Middle East, and Jordan specifically, is different from Western-centric research results on these topics, especially in regards to gendered participation in these fields of artistic activism. But the similarity between the two sides, Western and Middle Eastern, is that “the subculture of graffiti is similarly unwelcoming to females and femininity” (Pursley, 2012). Whether it is the dominance of men in the field, just as it was depicted in the Western-centric research, or it is the society’s unequal traditions and the social norms in the Middle East, as it was explained in the previous chapters, both sides do not welcome females in the field of graffiti and street art.

Nonetheless, female artists are still fighting for their part in the field of street art and graffiti. Graffiti and street art give female artists the chance to claim the public space, to make their presence known and to get the opportunity to change the society (Gentry, 2008). According to Lefebvre (1974), a city can be read on what is written and painted on its walls and public spaces just as you read a text (Lefebvre, 1974). Extrapolating Lefebvre’s thoughts onto the field of street art and graffiti this means that reading a city’s wall art and graffiti is revealing the local socio-cultural structures. The presence of female artists in the streets, and their performative acts of painting and writing on walls also creates a social space for other marginalized women to feel connected to that space through connecting to the delineated struggles (Gentry, 2008). This kind of feminist art helps to expand the gravitas of the artwork beyond its aesthetic features only and make it play a crucial role in impacting the social change dynamics that may lead to changing the lives of disadvantaged people for the better. The possibility of that to take place is partially dependent on the artists because “these artists are

24 frontrunners in the movement to use the arts to address social, economic and political inequities and improve opportunities for all” (Sidford, 2011). Holly Sidford (2011) further elaborates that these artists use their art in order to make the community as diverse as they possibly can and for that society to be able to address the inequalities that cause societal problems.

Thus, feminist art “highlight[s] the importance of social connection and work[s] through community” (Millner et al., 2015) by using the art as an ice breaker for the social tension between the genders in order to integrate feminism and women’s rights in the community in a subtle, but artistic way rather than imposing it onto a society that historically has resisted feminism as a perceived Westernizing intrusion into their established traditions and norms. That is why artists in Amman informed Zein Zu’bi (2018) that they need to manage art gradually when targeting topics that are less talked about and are considered a taboo.

Sardine, who is an informant for a study by Zu’bi (2018), stated that “there is no value in shock value. If I want to continue what I want to do and what I love, I’ll have to be respectful of the culture”.

In conclusion, the goals of Jordanian feminist artists line up with the objectives of feminist critics in art history, that is:

“recuperating the experience of women and women artists; critiquing and deconstructing the authority, institutions, and ideologies that created the gender bias; and evaluating the traditional cultural and psychological roles assigned and demonstrated by women” (Pursley, 2012, p.57).

Millner et al. (2015) discussed how their community in Australia employed the tool of feminist art and history reading circles in order to inspire their art and to establish a link between activism and feminist art. They also realized that women in societies are being underrepresented in the arts field in general. If this would have been introduced in Jordan it might, in the long run, also change how society looks at female artists and might achieve the tip of the social change that needs to be happening towards equality and feminism.

The previous chapter mentioned the existence of women’s organizations in Jordan that target the achievement of women’s rights and feminism and their inability to enforce a political change in order to make the lives of marginalized women better. An interviewee in Ferguson (2017) said that “if you want to be effective, social movements are important but they need political support, even a coalition with political parties or being more active in politics yourself….This is one major obstacle”.

Another interviewee in Ferguson (2017) said that, what women need is “more coordination and consistency” because what they do in these organizations is

25 scheduling meetings with officials to discuss different issues and these organizations have to negotiate and compromise and in the end will not get what they want. She mentioned an example on how the government will listen to their demands is shaped by what is happening in the streets, not in meeting rooms.

This is where the role of the artists becomes vital, as they are not bound to any specific organizations and therefore, use their art to trigger social movements so that these movements might have a chance to build a ground for social change.

To summarize this chapter, the concept of social change can be applied in many different fields but in the context of this thesis, social change is targeting the ideas and social movements in a society in order to change norms and tradition from one state to another. The content of this chapter is also going to assess the application of the methodology explained in the next chapter in order to come to a conclusion whether the discussed concept of social change is taking place in the Jordanian society from the perspective of artists, people and the municipality or not. The examples of the Sarah Hegazi’s mural and the ‘Break the Silence’ mural mentioned in this chapter gave an introductory overview of the situation in Jordan. But the next chapters are going to put emphasis on the general public and the artists.

Chapter (4): Methodology

In the following chapter, an introduction to the methodology applied is going to be provided as well as a discussion of the limitations.

This thesis uses a multimethod approach in order to gather different inputs and data. This multimethod research includes documents, observations, and interviews (Salmons, 2015). Both interviews and surveys are used in this thesis in order to gather primary data to analyze in order to reach a reliable result. The other method that is used is the iconography and iconology for the interpretations of the survey.

This methodology can be classified as a visual ethnographic research because it employs one of the most classical ethnographic methods, which is interviews but at the same time it is called ‘visual’ ethnographic research because it addresses the analysis of visual (Hamdy, 2015). In this type of research, as Hamdy (2015) noted that “the visual material is treated as evidence supporting a particular hypothesis on the meanings that the visuals elicited in their original context”. Hamdy’s (2015) argument indicates that the murals that are analyzed in this thesis will help support the thesis’ hypothesis.

26

4.1 Interviews

In order to gather as much elaborative data as possible, interviews were chosen as one of the methods to gather information from both graffiti and street artists as well as the municipality. Qualitative data was collected in order to gather as many opinions, points of view, and insights as possible from the informants. Quantitative data was not used due to the lack of statistical facts on the topic of street art and graffiti in Jordan.

The interviews were conducted using VoIP (Voice over Internet Protocol) technologies (Lo Iacono, Symonds and Brown, 2016) such as Skype and Facebook, as well as other internet research methods (Biber, 2012 as cited in Lo Iacono et al. 2016) such as email correspondence, WhatsApp texting and voice recording. The interviews with the artists were semi-structured, i.e. an interview guide with key questions was formulated (see appendix 1), but the actual course of the interview was structured by the informants, allowing ad hoc excuses and follow-up questions, depending on discourses touched upon and emphasized by the interviewees themselves.

The interviews were conducted with three graffiti artists in Jordan, Haneen Khamaiseh Maha Hinidi and Laila Ajjawi, with the latter two also participating in the Baladk Street Art Festival. All of them also exhibit independent works outside of any organized project or festivals.

The informant from the municipality was Shayma’a Al-Tal from the culture department. The interview with the municipality was structured because they requested the interview guide and their answers were sent via WhatsApp voice recording without the possibility for any extra or follow up questions (see appendix 2). This request was required because of the time constraints the informant had and the lack of other municipality employees in the culture department nowadays due to COVID-19.

A total of 13 invites were sent to artists, municipality employees and people from the Baladk Project. Two of them could not participate, four answered and seven did not reply. Two of the interviews were conducted in Arabic, with a translated version of the interview guide, and the other two were conducted in English. Later on, the transcription was translated by the author from Arabic to English in order to use it in the analysis.

The interviews were thematically analyzed, which, according to Braun and Clarke (2006) can be defined as “a method for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns (themes) within data. It minimally organizes and describes [the] data set in (rich) detail”. After the identification of recurring themes in the interviews, these were categorized in order to make them comparable to one another, as well as applicable to the theoretical framework.

27

4.2 Survey

Furthermore, a survey featuring 7 pictures of murals around Amman was conducted. This tool was used in order to investigate whether the general public would decipher the intended meanings behind the artworks or not. The survey was distributed on Facebook groups as well as sent out to individuals and they also sent it to others in order to get as many responses as possible and through different ages and genders. A sample of 67 responses was received from random people in Jordan over different age groups (see survey in appendix 3).

The methodology used to analyze the responses, iconography and iconology is “both a method and an approach to studying the content and meanings of visuals” as Müller (2011) explained. Traditionally, iconography and iconology were mainly applied to classic paintings in order to classify them into particular themes but more recent applications of this method have shown that it also can be used as “an analytical method of visual content analysis” (Müller, 2011). Iconography and iconology can be defined as “a qualitative method of visual content analysis and interpretation, influenced by cultural traditions and guided by research interests originating both in the humanities and the social sciences” (Müller, 2011). Müller also indicated that this method has potential to clarify and comprehend a better understanding of any mediated visuals as well as its ability to unravel how people interpret a piece of art and its relation to culture. He described it as a “forensic method” (Müller, 2011) as well as a method, in which different pieces are put together in order to understand the complete picture of an art piece and its relations to the period and the place it was produced in. Müller (2011) also identified iconology as “qualitative method aimed at the interpretation of visual content. Rooted both in art history and sociology, the method has the potential to better understand and explain the meanings of contemporary mass mediated visuals” (Müller, 2011).

The method that is used in this thesis is adapted from Erwin Panofsky (1955), as seen in Figure 3, and it consists of three stages in order to analyze a piece of art and reveal the meaning behind it.

28

Figure 3: Visual Interpretation by Panofsky, E. (1955). Meaning in the Visual Arts. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Those three visual interpretation steps are: Pre-iconographical description, iconographical analysis, and iconological interpretation. They are explained as follows:

1. Pre-iconographical description: As depicted in Figure 3, Panofsky (1955) labelled this stage as Primary or natural subject matter, which is apprehended by the person’s identification of “pure form” which consists of colors, lines, shapes as well as the depictions of natural objects just like animals, humans, plants, et cetera. This also includes acknowledging postures and gestures. Müller (2011) described this step as an attempt to see a visual “in a most neutral way, avoiding too early attributions of meaning”.

For this first step, Panofsky described the matter as simple because “everybody can recognize the shape and behavior of human beings, animals and plants, and everybody can tell an angry face from a jovial one” (Panofsky, 1955). By spotting these natural subject matters, we are using our “practical experience” (Panofsky, 1955) in order to literally read what we see.

2. Iconographical analysis: Building up on the pre-iconographical description is the iconographical analysis. After acknowledging the simple matter of art, the