1

LOCALIZATION OF MANUFACTURING –

A SYSTEMATIC FRAMEWORK

Kerstin Johansen1, Mats Winroth2

1

Linköping Institute of Technology, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden 2

School of Engineering, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden

ABSTRACT

Increasing competition forces companies to find the most beneficial way to manufacture their products for a global market. Most relocations of manufacturing have been justified mainly due to reduction of cost. The manufacturing industry is therefore facing a trend of localization of manufacturing in low cost countries, mainly Asia and Eastern Europe. Previous examples have been the ship building industry and the textile industry, when manufacturing almost disappeared from Europe and North America. The choice of localization is however more complex than to be based on cost solely, even though everything in one or another way can be translated into cost or income. Non-financial issues are difficult to estimate, but important to handle in order to attain a more holistic approach.

This paper presents an illustrative and holistic framework for making decisions on locating manufacturing in relation to the market and suppliers, linked to cost and competence.

Keywords: Localization, manufacturing, supply chain.

INTRODUCTION

Increasing competition within different business segments forces companies to find the most beneficial way to manufacture their products for a global market. Most relocations of manufacturing have been justified mainly due to reduction of cost. The manufacturing industry is therefore facing a trend of localization of manufacturing in low cost countries, mainly in Asia and Eastern Europe. Previous examples have been the ship building industry and the textile industry, when manufacturing almost disappeared from Europe and North America. The choice of localization is however more complex than to be based on cost solely, even though everything in one or another way can be translated into cost or income. Non-financial issues are difficult to estimate, but important to handle in order to attain a more holistic approach. This work explores different issues of importance for the decisions regarding localization.

2

We propose that the most important choices are made in three steps:

1. Identification of possible localizations. 2. Choice of localizations.

3. Decision on how to organize the activities at the new localization.

Different industry segments are facing different global operations of supply chains. The main part of the design work is spread all over the world and the manufacturing is located in the most suitable areas according to the framework described. In this research, managers within the industry have identified different important factors as the driving force to locate manufacturing mainly in Asia.

The paper is organized in 6 parts. The introduction gives a short background to the case studies. The theoretical approach presents a performed literature review. The case study section presents the methodology and the three case studies. The systematic framework for localization of manufacturing section presents the systematic framework that is developed by comparing the literature review with the empirical findings. Finally, the managerial implications are discussed referring to the performed case studies.

THEORETICAL APPROACH

Many companies often cluster together into groups of two or more organizations, as in strategic alliances, joint ventures and value-adding partnerships (De Wit & Meyer, 2002, p.10). This implies that new forms of organizations are taking place, such as virtual enterprises, global manufacturing, logistics networks, and different company-to company alliances (D’Amours et al., 1999). These new types of organizations are common when localizing manufacturing, since localization outside the main company can give co-operation within different types of extended enterprises, with different companies and/or organizations. Extended enterprises can, however, be viewed in several ways.

Figure 1 – a) The Generic Extended Enterprise Module (GEEM) b) A complex extended enterprise (Johansen & Björkman, 2002; Johansen, 2002)

b) a) Producer Producer Producer / Product Owner

Product Owner Supplier

Producer

Supplier Product Owner /

Supplier

3

Johansen (2002) defines one type of a generic extended enterprise module (GEEM) that consists of a Product Owner, who “owns” the product and its brand, a Producer that is responsible for product introduction and manufacturing, and finally, a Supplier of components, material, and/or equipment (figure 1). GEEMs can, of course, consist of several Suppliers, Producers, and Product Owners, which can be combined in a number of different ways. This gives a complex extended enterprise that, for example, is common within the electronic industry today, and the type of Extended Enterprise studied in the first case study.

Traditionally, policies related to facilities are location, specialization and size (Hayes & Wheelwright, 1984), where location deals with the general question of how to design a network of facilities. Companies generally recognize that tight interaction within their network or supply chain is a key requirement for their continued survival (Azevedo & Sousa, 2000). The decisions of where to locate a manufacturing must be taken together with marketing and logistics decisions (Rudberg & Olhager, 2003). Vereecke & van Dierdonck (1999) found that proximity to market is by far the most important factor concerning a site’s location; both in the start-up phase of the manufacturing and after a couple of years when it is established. Furthermore, they argue for that availability of low-cost manufacturing and skills also are of great importance. In a global context the localization of manufacturing or any other part of the company should significantly affect the company’s strategy in order to realizing their basic business motives (Ng & Tuan, 2003). Furthermore, Ng & Tuan argue that a company deciding where to locate i.e. manufacturing, in fact, is seeking for its competitive advantage.

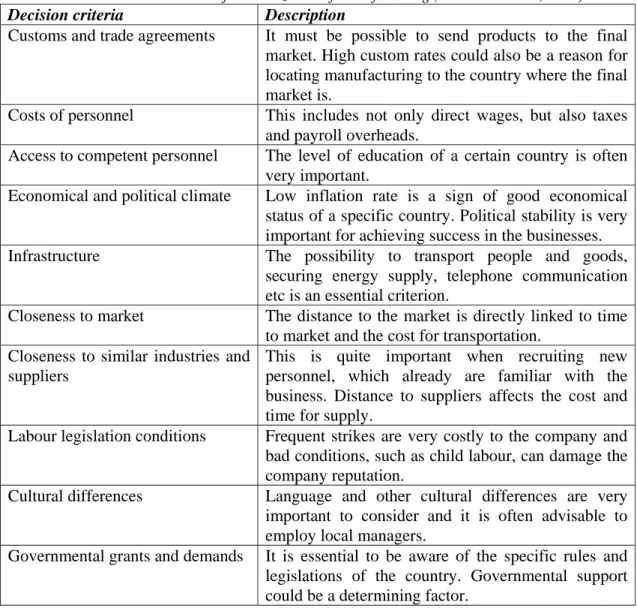

Andersson et al. (2001) performed a study of criteria for localization of manufacturing from a strategic perspective. They chose 21 countries all around the world, which the authors found to be the most interesting for locating manufacturing. These countries were situated in East Europe, Latin America, and Asia, i.e. the presently most popular countries for relocating manufacturing. Basic criteria for selection were e.g. low rate of wages, infrastructure, governmental support and demands, and that the countries were considered stable, both economically as well as politically. All ten criteria that were chosen for evaluation are described in Table 1.

Andersson et al. (2001) conclude by presenting a model for evaluating the different decision criteria. Each criterion gets a weight factor, which is estimated by comparing each criterion towards all the other. For each possible country each decision criterion is multiplied by the estimated weight factor and the most suitable country is chosen. As a complement to Table 1, Johansen et al. (2001) argue for the importance to do a sensitivity analysis before deciding for investments in new technologies, consider i.e. volume changes, frequency of new product introduction, and technology flexibility. These parameters are of importance when designing a manufacturing process. Furthermore, the technology used in a manufacturing process can differ depending on the localization of the manufacturing.

4

Table 1 – Decision criteria for localization of manufacturing (Andersson et al., 2001)

Decision criteria Description

Customs and trade agreements It must be possible to send products to the final market. High custom rates could also be a reason for locating manufacturing to the country where the final market is.

Costs of personnel This includes not only direct wages, but also taxes and payroll overheads.

Access to competent personnel The level of education of a certain country is often very important.

Economical and political climate Low inflation rate is a sign of good economical status of a specific country. Political stability is very important for achieving success in the businesses. Infrastructure The possibility to transport people and goods,

securing energy supply, telephone communication etc is an essential criterion.

Closeness to market The distance to the market is directly linked to time to market and the cost for transportation.

Closeness to similar industries and suppliers

This is quite important when recruiting new personnel, which already are familiar with the business. Distance to suppliers affects the cost and time for supply.

Labour legislation conditions Frequent strikes are very costly to the company and bad conditions, such as child labour, can damage the company reputation.

Cultural differences Language and other cultural differences are very important to consider and it is often advisable to employ local managers.

Governmental grants and demands It is essential to be aware of the specific rules and legislations of the country. Governmental support could be a determining factor.

CASE STUDIES

The case studies were performed in extended enterprises within the Swedish electronic and mechanical engineering industry.

Methodology

The research is based on a qualitative approach (Leedy, 1997), where the authors want to describe and explain ways of working in multinational companies today, especially for production engineers doing investment calculations when designing a manufacturing process.

The first study was focused on the key issues to manage while deciding localization of manufacturing within a company involved in an extended enterprise. The company is a Product Owner and Supplier (see figure 1) for an electronic module that is used in telecommunication equipment. The company is responsible for product design and

5

manufacturing. Data was collected through semi-structured interviews with the company’s CEO and Senior Director for Strategic Planning in September 2002. The interview were recorded and transcribed.

The second case study was focused on the organization of a collaborative network. The interviews where performed in a semi-structured way at all partners in the collaborative network. All interviews were recorded and transcribed.

The third case study was interesting, since the collaboration between the two partners seemed somewhat unexpected, with manufacturing in Sweden and design in China. The findings are based on discussions with the president of the company.

Case study: Electronic Company

Manufacturing of electronic products is depending on material supply to the production lines according to the interviewed. The main amounts of suppliers of electronic components are, today, situated in Asia. This implies that it is not beneficial to transport all components to Sweden for manufacturing and then distribute the products globally. The studied company calculated the cost level for transportation, manufacturing and distribution to their customers and the result was to start to manufacture in China. The decision for locating the manufacturing to China was also depending on where their customers have their manufacturing of the final product. Their analysis resulted in that the market will increase in Asia – especially in China.

Reducing the time for transportation by locating the manufacturing close to the market implies that the investment in material is decreasing and the risk for obsolescence are minimized. The blue collars in China are more specialists than in Sweden, which implies that they continuously increase the competence regarding their working tasks and therefore, continuously have the possibility to increase their salary. Furthermore, the salaries, today, are much lower in China than in Sweden, which implies a possibility to reduce the cost concerning manual assembly in the manufacturing.

A localization of manufacturing is a strategic decision that will give benefits in the future. Today, all necessary knowledge and competence within our electronic segment are available in China. The interviewees argue that their fundamental competence within their area has its basic infrastructure in China.

Case study: Heavy vehicle industry

In the second case study a large Swedish manufacturer of equipment for the heavy vehicle industry decided to offer its most important suppliers to move to a location in direct connection to the final assembly plant (Winroth & Danilovic, 2003) thus forming a close collaborative network. The companies of this collaborative network are all parts of large multinational industrial groups, with head-offices outside of Sweden. The supply was previously managed from the suppliers facilities located between 40 and 80 kilometers away. This caused however problems, since the Systems Integrator (SI) competes, among other things, by being able of accepting very late changes to specifications. Three key suppliers, who all had been supplying to the SI for many years, were offered to establish

6

small branches very close to the SI. Since the SI agreed to cover possible extra costs for the suppliers and that the suppliers also could get larger scope of delivery, taking over some work tasks even inside the SI’s premises, they accepted the offer. The SI could also reduce its own personnel since no purchaser is needed. There are only general purchasing agreements, and the amount of people handling the supply of components could be reduced. SI’s planning system is now ‘transparent’, i.e. the suppliers have direct access into the SI’s product planning system in order to see the planned orders and they can guarantee that the right components will be in stock at the right time.

The main result of the study shows the reasons for NOT locating the operations in low cost countries. These reasons are:

Customer demands for very late changes of specifications

The size of the product involves large cost and problems when shipping

The possibility to involve the partners (i.e. the suppliers) in the operations of the systems integrator

In order to support these reasons for NOT locating the operation in low cost countries, some companies in the collaborative network were moving closer to the SI. This is enabled by having very short distance between the companies – like in an industrial park – since even a distance of a few kilometers makes the contacts more difficult.

The only part that sometimes is supplied by companies in other countries is the very heavy counterweight. A supplier can easily supply this part after the distribution of the final truck from the SI to the customer and therefore, it does not need to be shipped back and forth to Sweden.

Case study: Supplier to a train manufacturer

The third case describes a supplier of a part of the main frame of locomotives. This manufacturer is situated in the heart of a SME (Small and Medium sized Enterprises) focused region in Sweden, i.e. in Småland.

The company manufactures the shock absorbing front cage for locomotives. The manufacturing of the structure involves large amount of metal work, including steel plate cutting and welding. All the work is performed in Sweden, except for the steel plow, which involves an enormous amount of welding. Due to high labor cost this is performed by a Czech company. The reason for not outsourcing the other man power (and consequently cost) consuming work tasks to low cost countries is solely the difficulties to transport the large structure back to Sweden for the final assembly. It would be too expensive, and the transport would take too long, if this task would be performed in e.g. South East Asia.

One interesting aspect of this frame maker is that they collaborate with a company in China, which performs the product development work and sends the drawings to Sweden electronically. This could maybe seem a bit surprising, but it has shown to be very efficient and the company responsible for the product design is skilled in CAD, which is lacking at the Swedish company. There is still the advantage of a favorable level of cost and with

7

modern communication technology the partners can have close contact during the development work.

SYSTEMATIC FRAMEWORK FOR LOCALIZATION OF MANUFACTURING Based on the theory and the case studies, we have identified a large number of issues that have impact on choice of localization, such as:

Where to find the final market Where to find the suppliers

Cost for transportation, duty and taxes Lead-times

Possibilities for collaboration with partners, since a trend among many companies is that they increase the level of collaboration in close network relationships and this facilitates through short physical distances between the partners – so called industrial parks

Communication between product development, marketing and manufacturing Economic and politic situation in the region

Trade agreements, and grants and claims from the Government Infrastructure

State of labor legislation

Salaries, including payroll taxes and other charges, since the level of i.e. automation can differ depending on the salaries

Competence and educational level in the area Language and cultural differences

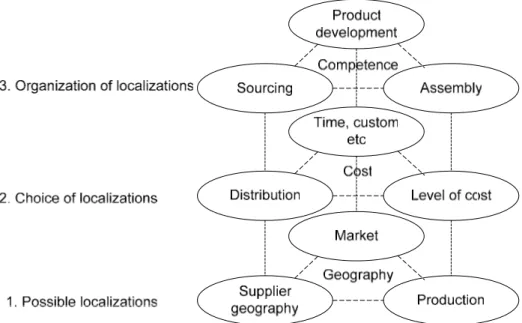

All these issues mentioned above, can or need to be considered when making global decisions on manufacturing localization. For the decision-makers there is a need for handling them in a structured and not complicated and time-consuming way. Therefore, we propose a framework for systematically choosing the localization of manufacturing, see Figure 2. The framework aims at being easy to understand and use, and it is supporting decisions made on a general level, prior to starting up a more detailed localization project. For more detailed solutions and/or studies, there are more detailed methods that can be used, but they need more facts and figures about areas, countries, and products, and therefore they are more resource- and time-consuming.

The framework is guided by three steps: 1. Identification of possible localizations.

2. Choice of localization(s). As we have seen, especially in case of the train supplier, it is possible that operations can be separated and localized differently depending on the nature of the work tasks.

3. Decision on how to organize the activities connected to the new localization(s).

Companies that are discussing localization projects do not necessarily always relocate the manufacturing. Depending on where to find the right competence and infrastructure, companies can relocate e.g. the design of product or function as illustrated in the third case study.

8

The three different steps in the framework have different focus:

Geography. Find the possible locations. The criteria can be all presented in Table 1, but the most important criteria, which are directly linked to manufacturing, are considered to be supplier geography, where the market is, and the possibilities for establishing activities in a certain region.

Cost. Chose the ‘best’ location. What are the levels of cost at the different locations? Does the infrastructure support the activities, or does that imply need for building new roads etc? What lead times for delivery would localization imply? Does the country have customs or trade barriers that involve higher cost? What impact has cost on the design of the manufacturing process?

Competence. Organize the facilities at the chosen location. Establishing activities at a certain region demands for competence. Product development, procurement, and manufacturing activities, such as assembly operations, all require the personnel to be skilled in one way or another. Is it possible to find competence or must the company put much effort into training the people?

Figure 2 – Framework for deciding localization of manufacturing

The following examples show how to use the framework presented in Figure 2. Applying this framework in the first case study – the electronic company – shows that the management first of all strategically identified the future market to increase dramatically in Asia. Furthermore, the majority of the suppliers are situated in Asia. Regarding to this information they found out that possible areas of localization is in Asia. The next step identified that the most beneficial place to locate a manufacturing was in China, since the cost level for transportation, distribution, and salaries were lowest there. Finally, the level of critical competence within the electronic industry is increasing in China and today the fundamental competence within the electronic company’s area has its basic infrastructure

9

in China. Therefore the third step in the framework indicated that it is preferable to locate the manufacturing in China.

The case study covering the supplier to a train manufacturer (Case study 3) shows the following discussion when applying the framework. Possible locations (Fig. 2, step 1) are preferable in Europe since the major market is there, even the majority of the suppliers and the major part of the production are today situated in Sweden. Choice of localization (Fig. 2, step 2) indicates that distribution and transportation costs are low since the market is geographically close to the manufacturing. Organization of localizations (Fig. 2, step 3) indicated, however, that it is beneficial to locate the product development in China in order to decrease the development costs and use their competence in this area. Furthermore, it is strategic to locate the time consuming welding in Czech, since they have much lower salaries than Sweden and the final component is suitable to transport. Furthermore, the competence for manufacturing this product is located in Sweden and it is not beneficial to relocate.

MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS

The suggested framework is general and can be used at companies within different segments of the industry with different types of relocation. The framework aims for being a support for the strategic management in order to choose an interesting and suitable area for localization of manufacturing. To choose localization do not necessarily means that the manufacturing must be relocated. As shown in the third case study the market is close to Sweden and the distribution cost and transportation time will be too expensive if the manufacturing are located in Asia, but in that case it is more beneficial to locate the product development in China. For the electronic industry in the first case study, however, it is more beneficial to locate the manufacturing in the China region, since most of the suppliers of components are situated there and the market in that region is increasing in the future. Furthermore, China has the competence for electronic manufacturing. In the second case study, describing a heavy vehicle industry, the management has decided to locate all involved competencies geographically close to each other in order to achieve short distribution / transportation time and fast communication between personnel.

The academic and industrial contribution is to present a framework for deciding localization of manufacturing that is easy to apply and at the same time gives a fast indication and support to the management for where to start the evaluation of a suitable localization.

REFERENCES

Andersson, M., Blomberg, R. & Bode, U. (2001), Lokalisering av produktionsanläggningar ur ett strategiskt

perspektiv, LiTH-IKP-R-1182, Report from Linköping University, Sweden (in Swedish)

D’Amours, S., Montreuil, B., Lefrançois, P. & Soumis, F. (1999), Networked manufacturing: The impact of information sharing, International Journal of Production Economics, Vol.58, p.63-79

De Wit, B. & Meyer, R. (2002), Strategy – Process, Content, Context, Thomson Learning, London, UK Hayes, R.H. & Wheelwright, S.C. (1984), Restoring our competitive edge – competing through

10

Johansen, K. (2002), Product Introduction within Extended Enterprises – Description and Conditions, Licentiate Thesis No. 978, Linköping University, Sweden

Johansen, K. & Björkman, M. (2002), Product introduction within extended enterprises, ISCE’02, Ilmenau, Germany

Johansen, K. & Winroth, M. & Björkman, M. (2001), An economical analysis on a strategic investment in an assembly line: Case study at Ericsson Mobile Communications AB, Linköping, Sweden, ICPR-16, Prague, Czech

Leedy, P. (1997), Practical Research: Planning and Design, Sixth Ed. Merril, An imprint of Prentice Hall, NJ

Ng, L.F.Y. & Tuan, C. (2003), Location decisions of manufacturing FDI in China: implications of China’s WTO accession, Journal of Asian Economics, Vol.14, p.51-72

Rudberg, M. & Olhager, J. (2003), Manufacturing networks and supply chains: an operations strategy perspective, The International Journal of Management Science, Omega 31, p.29-39

Vereecke, A. & van Dierdonck, R. (1999), Design and management of international plant netowrks:

Research report, Gent: Academia Press

Winroth, M. & Danilovic, M. (2003), Linking Manufacturing Strategies to Design of Production Systems in Collaborative Manufacturing Networks, POM-2003, Savannah, Georgia, USA

View publication stats View publication stats