Taxation of Bitcoin - Filling in the Blanks

An explorative analysis of tax evasion among Swedish investors and the

Swedish Tax Agency’s perception of the issue

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration, Finance

NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Civilekonomprogrammet

AUTHORS: My Larsson & Emeline Chamoun

TUTORS: Fredrik Hansen & Toni Duras

JÖNKÖPING 24

thMay 2021

ii

Master Thesis in Business Administration, Finance

Title: Taxation of Bitcoin - Filling in the Blanks Authors: My Larsson & Emeline Chamoun Tutors: Fredrik Hansen & Toni Duras Date: 2021-05-24

Key Terms: Bitcoin, Tax Compliance, Behavioral Finance, Tax Evasion, The Swedish Tax Agency

__________________________________________________________________________________

Abstract

Background: The ongoing digitalization in the world with accelerated advancement of technology both

develops and challenges the traditional view of means of payment. Legal and economic challenges have been recognized in regard to Bitcoin, one of these challenges refer to Bitcoin being defined as property of capital which has caused difficulties in individual income declaration and an overall challenge for cryptocurrencies to act as currencies. Furthermore, Bitcoin is being recognized as an investment possibility, however, since Bitcoin transactions are anonymous it contributes to issues within the public economy as profits made from Bitcoin trades are being evaded.

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to analyze tax evasion among Swedish investors when trading

with Bitcoin. Furthermore, this study aims to expand the understanding of Bitcoin traders and determine whether some individuals are more likely to evade taxes in regard to trades with Bitcoin. The intention is to identify whether there is a connection in demographic- and behavioral factors that indicate whether one is more willing to comply with tax obligations or not. This paper further aims to investigate the STA’s perception of Bitcoin in comparison to the general public as well as how the STA work with the challenges that exist today.

Method: This study uses a combination of an inductive and an explorative approach with a mainly

quantitative research strategy. Three sources of data have been used: 1) an online survey published in forums for Swedish investors, 2) interviews with the STA 3) court orders provided by the STA. Furthermore, a binary logistic model was performed in SPSS to examine statistically significant results.

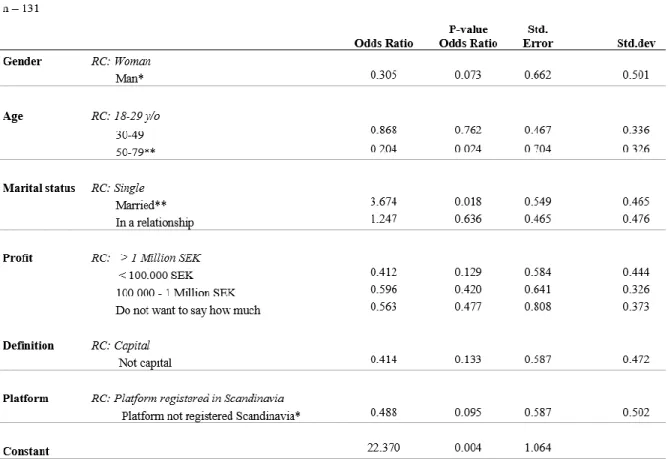

Conclusion: In regard to taxes linked to trades with Bitcoin, the findings of this study confirm that

women are more likely to evade taxes, individuals between the ages of 50 and 79 are less likely to evade taxes in comparison to ages ranging between 18 and 29, individuals who are married are more likely to evade taxes than individuals who are single and investors using platforms registered within Scandinavia are more likely to evade taxes. In addition, the findings of this study indicates that behavioral factors such as morale, trust, awareness, social influence and probability of detection may be influential in tax compliance. Furthermore, the study found a deviation in the perception of taxation linked to Bitcoin where the STA does not recognize taxation linked to Bitcoin as a cause of concern whilst the general public find it to be difficult and an increased risk of tax evasion.

iii

Acknowledgements

We would like to take the opportunity to express our gratitude to everyone who has contributed to this thesis. First of all, we would like to thank our tutor Fredrik Hansen who has provided us with helpful

insights and constructive feedback. We would also like to thank Toni Duras for his support in the statistical field.

Second of all, we would like to express our gratitude to the Swedish Tax Agency and each respondent in our web-survey for their valuable information and perspectives that have enabled us to accomplish

a thorough analysis.

Lastly, we would like to thank the participants of our seminar group who have given us valuable feedback to help us strengthen our thesis.

__________________

__________________

My Larsson Emeline Chamoun

iv

Table of Contents

Definitions ... 1

1. Introduction ... 2

1.1 Background ... 2

1.2 Problem Discussion ... 4

1.3 Purpose and Research Questions... 4

1.4 Delimitations ... 5

2. Frame of Reference ... 6

2.1 Introducing Bitcoin ... 6

2.1.1 Trading Platforms ... 9

2.1.2 Bitcoin as an Investment... 10

2.2 Regulations ... 12

2.2.1 Sweden... 12

2.2.2 European Union ... 13

2.3 Tax Compliance ... 14

2.3.1 Models of Tax Evasion ... 15

2.3.2 Motivations for Tax Compliance ... 16

2.3.3 Probability of Detection... 18

3. Methodology and Method ... 20

3.1 Methodology ... 20

3.1.1 Research Philosophy... 20

3.1.2 Research Approach ... 20

3.1.3 Research Strategy ... 21

3.2. Method ... 22

3.2.1 Data Collection ... 22

3.2.2 Population and Sampling ... 24

3.2.3 Binary Logistic Model ... 25

3.2.4 Correlation ... 27

3.2.5 Variables ... 27

3.2.6 Data Analysis ... 29

3.2.7 Reliability and Validity ... 30

4. Empirical Findings... 32

4.1 Interviews and Court Orders ... 32

4.2 Survey... 36

4.2.1 Descriptive Statistics ... 36

4.2.2 Survey Questions Regarding Attitude to Tax and Morality ... 41

v

5.1 Interviews and Court Orders ... 44

5.2 Survey... 46

6. Conclusion ... 50

7. Discussion ... 52

7.1 Perception Versus Findings ... 54

7.2 Contribution and Self-criticism ... 55

7.3 Future Investigations ... 56

8. References ... 59

vi

List of Figures

Figure 1 Structure of blockchain………7

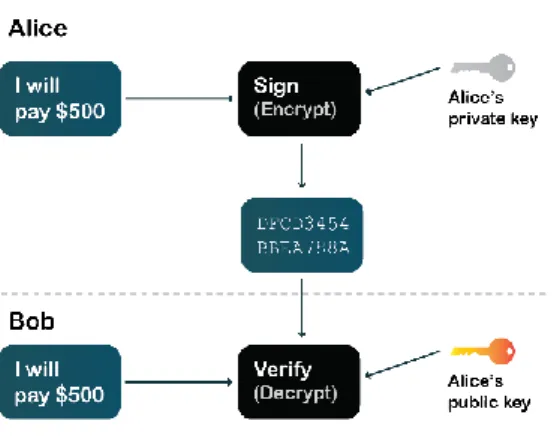

Figure 2 The keys roles in a digital transaction………..8

Figure 3 Motivation of survey participants………...31

Figure 4 Distribution of platforms used by survey participants in Regression 1……...…...36

Figure 5 Distribution of participants profit in Regression 1………..37

Figure 6 Distribution of platforms used by survey participants in Regression 2…………...37

Figure 7 Distribution of profit in Regression 2……….. 38

Figure 8 Summary of attitude towards simplicity of declaration………...…41

Figure 9 Summary of attitude towards the opportunity to withhold income……….…41

Figure 10 Summary of how many people who know somebody that evades taxes……..….42

Figure 11 Summary of attitude to tax evasion if it is not detected………...42

Figure 12 Summary of the perception that the STA is successful in the work of finding tax

evaders………... 42

Figure 13 Summary of the perception that the STA find tax evaders……….………...42

Figure 14 Summary of the survey participants perception that the tax rules regarding Bitcoin

is correct……….……….…43

Figure 15………...…..43

List of Tables

Table 1 Facebook groups used to distribute survey……….………24

Table 2 Summary of independent variables used in the binary regression model…..……….28

Table 3 Summary of court orders……….35

Table 4 Summary of Regression 1………..….39

Table 5 Summary of regression 2……….……...40

1

Definitions

Address A Bitcoin address can be described as a virtual location to which

cryptocurrencies can be submitted.

Bitcoin A peer-to-peer digital cash system that allows anonymous payments from

one to another without the use of a financial institution

Blockchain A public and digital record of transactions among cryptocurrencies.

BTC The token of Bitcoin.

Cryptocurrency A digital currency that operates in a global, decentralized and protected

environment through the use of cryptography.

FIAT-currency Government-issued currency.

Hash The unique “fingerprint” of a block. A mathematical algorithm which maps

data into a fixed size string. Is required to create new blocks.

Mining The mathematical puzzle where transactions are added to blocks and how

new Bitcoin is extracted.

P2P

A peer-to-peer (P2P) service is a decentralized platform where online payments can be sent directly from one individual to another without the use of a third party.

Tax compliance Taxpayers’ decision to comply with tax laws and regulations.

Tax evasion An illegal and deliberate choice not to pay tax liabilities.

Trading platform

A software that allows investors and traders to make trades and control their accounts. Trading platforms often have additional features such as premium analysis, charting tools and news feeds.

Wallet

A Bitcoin wallet holds all of one’s digital Bitcoin information and verifies transactions made. The information is kept private by encrypting it with a private key.

2

1.

Introduction

___________________________________________________________________________

This chapter will introduce the motivations for the establishment of Bitcoin and explain its advantages and disadvantages. Furthermore, the problem discussion will be examined, followed by a presentation of this study’s purpose and research question. After that, the delimitations will be stated.

__________________________________________________________________________________

1.1 Background

The accelerated advancement of technology and the expansion of internet usage have resulted in many global transactions regarding online purchases. In a review of the global retail market in 2020, sales from physical retail were estimated to $18.5 trillion, while sales from e-commerce retail were estimated to $4 trillion and are expected to increase over time (Statista, 2021). Although physical retail is predominant, online retailing is becoming more popular. This modern phenomenon has forced many traditional, face-to-face stores to redirect their businesses online. Potential factors contributing to this online trend may be convenience, diminished overhead costs, and a significantly expanded online market (Bernstein et al., 2008). As online transactions require electronic payments, there is a transition towards a predominantly cashless society. As of today, bank-issued credit cards are the dominant payment method. Credit cards enable currencies to be traded instantly and globally. However, there are many risks and inconveniences involved with the global use of credit cards, such as credit fraud and inevitable fees charged by credit card providers. With a growing global economy primarily fueled by online transactions, one could argue for a stable, low-cost, and globally recognized payment method. This laid the foundation for an electronic payment system, namely the cryptocurrency Bitcoin, which was developed anonymously under the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto and was first introduced in 2009 (Nakamoto, 2008).

Nakamoto has still not been identified, however, Nakamoto has claimed that his/her wealth is equivalent to roughly $100 million in Bitcoins (Bradbury, 2013). Bitcoin was developed due to an insight into a need for an electronic payment system that was not linked to any third party. Nakamoto (2008) argues that for available systems in 2008, electronic payments were built around financial institutions as a trusted third party. However, Nakamoto (2008) states that these types of systems suffer from shortcomings related to the trust-based model. By implementing an electronic payment system that is based on cryptographic proof instead of trust, Nakamoto (2008) believes to have found a way to accomplish completely non-reversible transactions. To meet the requirements of cryptographic proof, Bitcoin is developed through a peer-to-peer network where payments are sent directly between parties. The approach excludes other financial institutions and protects sellers from fraud through computationally impractical transactions. Additionally, Bitcoin can also protect buyers by implementing routine escrow mechanisms. Nakamoto (2008) argues that cryptocurrencies, in this case,

3

Bitcoin, are a solution to the double-spending problem that arises when the electronic payment system forces buyers and sellers to involve financial institutions as a third party.Bitcoin is considered to be the first cryptocurrency and is still one of the most popular and established cryptocurrencies, despite the fact that there are currently over 1600 currencies on the market (Li & Whinston, 2020). The value of Bitcoin did not develop significantly during the first years, however, Bitcoin gained momentum and began to increase in value in the year 2017. One year later, in 2018, Bitcoin became a hot topic worldwide, and the value consistently reached new all-time-high levels. After a peak in December 2018, the interest in Bitcoin wore off, however, a dramatic interest in Bitcoin returned during 2021 and has since then more than doubled in value (Coindesk, 2021a). Thus, as Bitcoin increases in both price and popularity globally, the rush in the market has also affected Swedish investors. As Bitcoin has rushed towards new record levels, the interest in investing in Bitcoin has increased significantly in Sweden, which can be seen in information shared by banks such as Avanza and Nordnet, where large increases in Bitcoin investors have been reported. Avanza presents an increase of as much as 130 percent, while Nordnet has identified an increase of 68 percent the past year. Although Bitcoin is currently thought to be in a bull market for an indefinite time, the conditions for value development are perceived differently this time in comparison to the increase in 2017. One aspect that differs from previous years is that Bitcoin has gained legitimacy as it is supported by several prominent financial players and, thus, leading to acceptance by the professional financial community. These financial players include the electric car manufacturer Tesla, the finance company Square and the cloud service company Microstrategy. Additionally, PayPal has also opened up to the possibility of paying with Bitcoin. The fact that Bitcoin is now viewed as an investment opportunity by companies as well contributes to the price development and legitimization of Bitcoin (Pierrou, 2021).

Bitcoin was the first currency based on the technology blockchain, which makes transactions with Bitcoin more difficult to track, leading to both positive and negative consequences. Privacy through the blockchain reduces risks of data leakage and targeting but at the same time makes illegal activities harder to identify and trace. For instance, Bitcoin has been established as the main payment method for retailers operating on the Darknet and ransomware attackers (Li & Whinston, 2020). The problem with tracking cryptocurrencies has also created a loophole in relation to taxation, which, if continuously exploited, can lead to a higher tax burden for taxpayers overall. The consequences can be seen as unfair for compliant individuals who report their trades with cryptocurrencies in their income declaration, at the same time as it becomes an incentive for the dishonest to refrain from reporting profits made through crypto trading (Dierksmeier & Seele, 2018). The control coordinator at the Swedish Tax Agency (STA), Henrik Kristerud, states that approximately 3000 individuals per year have reported their profits from transactions with cryptocurrencies during the recent years, ranging from small amounts to millions. However, the hidden statistics are assumed to be greater, and the actual number is likely much higher

4

(Lindström, 2021). During 2018, the STA decided to include cryptocurrencies in one of their focus areas for control initiatives which gave results. The initiative led to between 300 and 400 new investigations of individuals who traded in cryptocurrencies were initiated in 2018, which is ten times more than the previous year. In some cases, detected tax evasions led to individuals being taxed with several million Swedish crowns of the authority (Hellerud, 2019). In summary, as Bitcoin increases in popularity, it also increases its impact on the public economy. Although the STA has regulated how Bitcoin should be taxed, it can be considered an area that is in need of further development. However, a solution must be found that is applicable from both a societal perspective and for the Bitcoin investor. The estimated blind spots regarding tax evasion among Bitcoin investors indicate that the current solution has failed to solve the effective taxation of Bitcoin.1.2 Problem Discussion

Legal and economic challenges have been recognized in regard to Bitcoin, where one of these challenges refers to the definition of Bitcoin. The STA defines Bitcoin as a property of capital instead of a currency (Skatteverket, n.d.a), which has caused difficulties in individual income declaration and an overall challenge for cryptocurrencies to act as currencies (Wiseman, 2016). In 2018, the tax reform of Bitcoin was tried in the Supreme Administrative Court of Sweden. In their verdict, the Supreme Administrative Court announces that Bitcoin cannot be equated with a co-ownership or foreign currency. The sale of Bitcoin must therefore be taxed in accordance with the provisions on other assets (Högsta förvaltningsdomstolen, case nr 2674-18 verdict 04/12/2018).

Besides being used as a currency, Bitcoin is being recognized as an investment possibility as there are significant fluctuations in its value in comparison to conventional currencies. While Bitcoin is used legally in a broad variety, the aspect of anonymity has been misused and exploited for illegal purposes. Although the aspect of anonymity in the world of Bitcoin may be of advantage from an individualistic aspect, it has contributed to issues within the public economy as profits made from Bitcoin trades are being evaded (Wiseman, 2016). The issue of tax evasion in regard to trades with Bitcoin is an issue recognized by authorities worldwide, and the significant increase of interest in Bitcoin has not passed unnoticed by the STA. There are indications that the STA is aware of the existing challenges as they, for instance, implemented a control effort in 2018 and made public statements indicating that the hidden statistics among tax evasion within cryptocurrency trading are relatively high (Lindström, 2021).

1.3 Purpose and Research Questions

As cryptocurrencies increase in popularity, it is important from a societal perspective that all adhere to the existing tax rules. The STA works to ensure that the obligated taxes are constantly contributed to the foundation of Swedish society and its public economy. From the perspective of the STA, it is a given that it should be easy to pay taxes and have your affairs in order. However, when an individual is

5

faced with the choice of contributing to society or obtaining profit oneself, a dilemma might occur. The research for this study aims to analyze tax evasion among Swedish investors when trading with the cryptocurrency Bitcoin. Furthermore, this study aims to expand the understanding of Bitcoin traders and determine if some individuals are more likely to be non-compliant in reference to the Swedish tax system by committing tax offenses. The intention is to identify whether there is a connection in factors such as age, gender, and transaction amount, that indicate whether one is more willing to comply with tax obligations or not. This paper also aims to investigate the STA’s perception of Bitcoin and how they work with the challenges that exist today. Since Bitcoin is still considered a relatively new phenomenon, this study also creates an opportunity to highlight current issues in society. In order to address this problem, the following research questions were formed:RQ1: What demographic- and behavioral factors influence whether an individual chooses to evade tax

when trading with Bitcoin?

RQ2: How well does the Swedish Tax Agency’s perception reflect the actual issues regarding the

taxation of Bitcoin?

1.4 Delimitations

The study will solely analyze tax evasion in relation to Bitcoin and will thus not address other cryptocurrencies. Furthermore, the study is limited to private individuals who trade with Bitcoin and will thus not address neither corporate trading nor illegal transactions as a subject itself. Thus, the intention is not to exclude the individuals who use Bitcoin for illegal purposes. Geographically, the study is limited to Swedish investors, where the respondents have been reached through forums intended for private investors where the data was collected through an online survey. Furthermore, the court orders regarding Bitcoin used as data in the analysis have been provided by the STA, hence, further measures to find other court orders have not been undertaken.

6

2. Frame of Reference

___________________________________________________________________________

This chapter will present a deeper understanding of Bitcoin in which its structure, manufacturing, and trading platforms will be presented. Furthermore, this chapter will examine whether Bitcoin can be viewed as an investment opportunity and what the regulations regarding Bitcoin look like from a Swedish- and a European perspective. Finally, this chapter also examines the behavioral aspect regarding tax compliance to provide further theoretical basis for why individuals choose not to comply with tax regulations.

___________________________________________________________________________

2.1 Introducing Bitcoin

The Blockchain

The true innovation and core of Bitcoin is the blockchain which is described as an online ledger where all transactions of Bitcoin can be traced, all the way back to the beginning (Maram, 2018). The Bitcoin network is a peer-to-peer network, and the blockchain is available for anyone who downloads the Bitcoin core (Böhme et al., 2015). Therefore, to comprehend the concept of Bitcoin, it is important to have a thorough understanding of the technology of the blockchain. Nakamoto (2008) developed the chain, which is built on digital signatures in order to define an electronic coin. When an owner transfers a coin, he or she digitally signs a hash of the previous transaction and the next owner’s public key by adding this information to the end of the coin, the transaction data is then used by miners to add blocks to the blockchain.

Mining

The mining process is Nakamoto’s way to secure the ledger of the blockchain and is an incentivized process. When a transaction is made, digital copies of it are distributed to all “miners” in the global peer-to-peer network for verification. The miners can be either individuals or groups that use independent computers to run the Bitcoin software, so-called nodes. When a transaction is made, the mining process can be described as a race where the miners compete for the rights to bundle the transaction into a block. The winning miner is the first one to find a “magic number,” which is a solution to a mathematical puzzle involving the previous block’s encrypted data, also known as the hash, and much-computerized error and trial. The solution is complicated to find, but when the magic number is defined, it can easily be verified by other nodes in the peer-to-peer network.

The first miner to solve the magic number for a transaction is rewarded with Bitcoins as a means of gratitude, and the block will then be added to the previously calculated blocks, which creates the blockchain (Maram, 2018). The structure of the blockchain is illustrated in figure 1. After a reduction in May 2020, the current (in April 2021) reward for mining one block is 6.25 Bitcoin, with an

7

approximate value of 3.2 million SEK (Godbole, 2021). The reward for solving the puzzle is reduced by half the amount of Bitcoins every fourth year, at the same time, the puzzle gets more complicated to solve when more nodes join the network. When minors have solved the puzzle for 21 million Bitcoins, there will be no more rewards left, and no new Bitcoins will be created (Böhme et al., 2015). Mining might seem available for everyone, however, it requires a large number of electricity resources. In one year, mining for Bitcoin consumed approximately 87.1 terawatt-hours of electricity which corresponds to the energy consumption of a country like Belgium (Badea & Mungui-Pupazan, 2021). Further, the mathematical puzzle increases in difficulty such that the time interval between the solution of two blocks is kept around 10 minutes. Thus, the mining process will continue to require a large number of resources as the reward reduces (Böhme et al., 2015)Figure 1 Structure of blockchain

Hash

A hash can be explained as a mathematical algorithm mapping data that results into a fixed-size string. In general, the data for blocks in blockchains include the previous block’s hash and the

recorded transactions. This means that if you want to write a new block, you need to find the previous hash (Li & Whinston, 2020). Easily explained, the hash for a block can be interpreted as a fingerprint. The hash is unique for each block, just as the fingerprints are unique for humans.

Verification

Due to the Bitcoin core, all nodes possess a copy of the blockchain. For a person with limited knowledge of the blockchain, it may sound strange and may be perceived as an opportunity for nodes to manipulate the ledger, however, that is not possible. In principle, the structure of the blockchain is considered secure since the mathematical puzzle is too complicated and hard for the same miner/node to solve every time. Thus, no one would be able to rewrite the ledger since they cannot access the encrypted links required. Due to the blockchain being an online ledger of all transactions ever made with Bitcoin, it can be used as proof of ownership. As mentioned before, it is possible for anyone to download the “Bitcoin core,” which also means that it is possible to create a wallet for storage of your Bitcoins without proving your

8

identity or giving your real name (Böhme et al., 2015). Thus, even though it is not that complicated to follow the coin between wallets, it is not quite as easy to determine who is the real owner among them.Keys

Further, the concept of so-called keys is a significant part of Bitcoin’s structure. In order to spend and store money, Bitcoin uses public-private key cryptography. The keys are generated in pairs and are mathematically related, however, it is not feasible to calculate a private key through a public key. The public key is a cryptographic code that can be seen as an address or account number of the users. It is created and stored by cryptocurrency wallets. The public key makes it possible to follow where the ownership of cryptocurrencies is registered (Li & Whinston, 2020). The public key should, as the name implies, be available to the public, and the encryption of the data is implemented using this key. The private key, however, is never revealed and is used for decrypting the data (Maram, 2018).

The standard public-private key cryptography means that it is possible for anyone to create a pair of keys intended for Bitcoin trade (Böhme et al., 2015). In terms of traditional currency, the keys can be equated with personal information. If you have money in a bank account, you ensure your ownership of that account through your personal information. Simply put, the function of the keys can be interpreted in the same way. The ownership of the Bitcoin is registered on the account number provided by the public key, and the transaction is authorized by a digital signature created through the private key. Thus, the digital signature certifies the ownership of the Bitcoin associated with the public key (Li & Whinston, 2020). Looking at an example where Alice transfers Bitcoin to Bob, the three pieces of information in the transaction are Bob’s Public Key, the amount that Alice sends to Bob, and Alice’s public key. The roles of public and private keys are presented in figure 2, illustrating the transaction between Alice and Bob (Marman, 2018).

9

Wallets

In order to make the transactions and store Bitcoin, all users require the keys mentioned in the previous section and a Bitcoin wallet. A wallet can easily be described as a digital bank account holding a collection of public and private keys. Every wallet has its own secret key to gain access, if this key is lost, there is no way for the owner to prove that they are entitled to the wallet and the Bitcoins in it. Thus, an owner who cannot access their wallet will lose all ownership (Volety et al., 2019). There are two main categories of wallets: hot wallets and cold wallets. A hot wallet requires an internet connection in order to gain access to it whilst a cold wallet does not. Cold wallets can be compared to a bank vault where the users can store a large number of Bitcoins. Furthermore, cold wallets can be exemplified as hardware- and paper wallets. Hot wallets, on the other hand, are often used when purchasing online or hold a smaller amount of Bitcoins. Examples of hot wallets are mobile, desktop, online, and multi-signature wallets (Jokić et al., 2019).

2.1.1 Trading Platforms

There are a wide variety of spot exchanges for Bitcoin on the Internet that are more or less reliable. CoinMarketCap (n.d) ranks 304 different platforms on their website. The list is composed by evaluating the platforms through traffic, trading volumes, liquidity, and trust in the recorded legitimacy of trading volumes. The platform with the highest score is Binance, ranked with a score of 9.8 out of 10. Of all 304 platforms, Binance is the one with the highest trading volume and has the most visits. Binance supports 46 different FIAT currencies (government-issued currencies), where the Swedish krona is included among them. The headquarters of Binance is located in Malta, and the platform was founded in 2017. Binance is used worldwide, and over 1.4 million transactions are executed every second via the platform (Binance, n.d).

Huobi Global, a Seychelles-based platform, receives the second-highest ranking of 9.1 from

CoinMarketCap (n.d). By using Huobi Global, it is possible to realize transactions through 62 different FIAT currencies, including the Swedish krona (Huobi OTC, n.d). Huobi was founded in China and currently employs over 1,300 people around the world (Huobi, n.d). The third place on the list provided by CoinMarketCap goes to Coinbase with a ranking of 8.9. Coinbase was founded in 2012 and is headquartered in San Francisco, USA (Coinbase, n.d). As for FIAT currencies, Coinbase supports the currencies USD, EUR, and GBP (CoinMarketCap, n.d). On April 14 of this year, Coinbase was listed on the Nasdaq stock exchange. The market capitalization was estimated between 70 and 100 billion dollars, thus, the listing was expected to be the largest in the U.S. since Facebook (Wilson, 2021). However, Coinbase has not had a stable journey on the stock exchange since listed. According to analysts, this is not surprising as the stock is expected to follow developments for cryptocurrencies which are known for their volatility (Åkerman, 2021). In the top five of the CoinMarketCaps (n.d) ranking list, the two remaining platforms are Kraken with a score of 8.6 and Bitfinex, with a score of

10

8.4. Kraken supports seven FIAT currencies and is headquartered in the U.S. (Kraken, n.d), whilst Bitfinex was founded in Hong Kong (Bitfinex, n.d) and supports the currencies USD, EUR, GBP, and JPY.Even though the previously mentioned platforms receive the highest-ranking, they do not necessarily have the highest trading volumes. Binance has the highest trading volume ($41.211.007.252/day), however, the following places ranked in order of trading volume are received by platforms with rankings ranging between 3 and 4.5. Two examples on platforms with high trading volume but rather low rankings are HBTC ($18.615.878.732/day) and Hydax Exchange ($16.226.693.296/day) (CoinMarketCap, n.d). Furthermore, it has also become possible to invest in bitcoin certificates via various banks such as Avanza and Nordnet in recent years. An important difference here, however, is that banks and credit institutions are obliged to provide control information to the STA (SFS 1990:325, ch. 3 § 27).

2.1.2 Bitcoin as an Investment

There are different views on whether Bitcoin should be seen as an investment vehicle or a speculative vehicle. From a macroeconomic perspective, Bitcoin is argued to be not only an alternative to cash (Evans-Pughe, 2012) but also an alternative to replacing the financial institutions (Kerner, 2014). Furthermore, Bitcoin can be perceived as a tool when hedging against economies with high inflation rates (Richardson, 2014). However, there is a negative perception that is important to underline in this discussion. As Bitcoin can be used as a payment method (Li & Whinston, 2020), especially within the darknet, it serves as a gateway for money laundering and is further argued to be a force that can cause economic destabilization (Stokes, 2012). Baek and Elbeck (2015) state that Bitcoin should be considered a speculative vehicle rather than an investment vehicle. The statement is explained by their findings indicating that the return of Bitcoin is not influenced by macroeconomic conditions. Instead, the return is internally driven by buyers and sellers and according to the risk appetite of the investors. However, Baek and Elbeck (2015) also emphasize the future development of Bitcoin and how a potential increase of usage will affect the volatility and contribute to a more balanced investment vehicle. Since 2015 the value of Bitcoin has increased by about 145 times (Coindesk, 2021a). In regard to the price of Bitcoin, there have been significant increases and declines, which have resulted in high volatility. In general, the characteristic of significant fluctuations is a common issue in speculative assets. Thus, individuals who work within fields of law, economy, entrepreneurship, and investors have a great interest in the determination of whether Bitcoin can be identified as an investment- or monetary asset. Their interest stems from their dependence on the type of asset in their decisions and investment strategies (Eom et al., 2019). Platanakis and Urquhart (2020) analyzed Bitcoin in contrast to other financial assets by observing price changes and weekly rebalancing their portfolio, the findings of Bitcoin indicated similar hedging capabilities to gold.

11

Lammer et al. (2019) performed an analysis using administrative data with the aim to identify the general cryptocurrency investor by investigating descriptive statistics of crypto- and non-crypto currency investors. They found that significant volatility and trading activity have attracted investors within retail to Bitcoin, although specific information regarding personal characteristics and demographics remain unidentified as the underlying nature of cryptocurrencies is the aspect of anonymity. However, Lammer et al. (2019) findings indicate that male- and high-income investors are more likely to invest in cryptocurrencies. Furthermore, Lammer et al. (2019) argue that investors that are inclined to invest in the lottery- and penny stocks and appreciate gambling may be attracted to cryptocurrencies due to their similarity in risk. Lammer et al. (2019) further found that both young, less wealthy, and uneducated single men as well as wealthy and educated men invest in lottery-type stocks. Thus, there is a high probability that the average cryptocurrency investor may be a middle-aged man, however, whether the average investor is wealthy or educated remains unknown. Although, it can be presumed that the average cryptocurrency investor has a riskier portfolio than the average individual investor.Recently, large institutional investors have been investing and speculating about investing in Bitcoin, which has increased its legitimacy as well as increased the price of Bitcoin to all-time high levels. To name a few publicly traded firms that have adopted Bitcoin as a reserve asset, the electric vehicle manufacturer Tesla has invested in Bitcoin with an amount equivalent to $19.384 billion cash holdings. Tesla has further stated that their expectation is to accept Bitcoin as payment for their products in the future (Phillips & Graves, 2021). However,Bitcoin’s role in Tesla’s business model became uncertain shortly after the investment when the company’s CEO, Elon Musk, announced that Tesla would suspend car purchases using Bitcoin due to environmental concerns.Musk has stated that Tesla will not sell any holding, but the statement still caused a significant drop in the value of Bitcoin. However, the total increase in the value of Bitcoin over the past year remains very high (Kharpal, 2021). Furthermore,

MicroStrategy is a well-established market analytics platform that has made Bitcoin their predominant

reserve asset. Microstrategy develops mobile software and cloud-based services; as of February 2021, they now hold 71 079 BTC in reserve, which is equivalent to over $3 billion in Bitcoins. Michael Saylor, CEO of MicroStrategy, argues that Bitcoin is preferred over gold as a reserve asset since its return is far more compelling and draws the resembles to digital gold (Phillips & Graves, 2021). However, Swedish- and European authorities, such as The Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority and The

European Supervisory Authority, have warned about cryptocurrencies as an investment as they involve

great risk and weak protection for the consumer. They indicate that consumer protection is insufficient and that cryptocurrencies are difficult or impossible to estimate in a reliable manner. They further point out that this type of product is not covered by the same consumer protection rules that apply to several other types of investments, resulting in an even greater risk of lost money among consumers (Finansinspaktionen, 2021; Coindesk, 2021b).

12

2.2 Regulations

2.2.1 Sweden

Sweden’s welfare system is built on the presumption that everyone should contribute by paying taxes. In Sweden, residents declare their income to the tax agency once a year. Since Bitcoin is considered an alternative asset (Förvaltningsrätten Göteborg, 2246-46), once a private individual sells or uses Bitcoin, he or she is obligated to declare it in the tax declaration as capital using form K4, section D (Skatteverket, n.d.a). If the transaction results in a profit, the user is obligated to pay tax on that profit. On the other hand, if the transactions generate a loss, the users must deduct it in their tax declaration. Examples of activities that, according to the Swedish income tax law, requires a declaration of Bitcoin are:

• Sale of Bitcoin

• Exchange Bitcoin to one or more other types of cryptocurrencies • Exchange Bitcoin for a FIAT currency, for instance, SEK

• Pay in Bitcoin when purchasing a product or a service (for instance, clothing and/or a taxi ride)

• Lend or use Bitcoin as a gaming stake

(Skatteverket, n.d.b). To calculate the final profit or loss, private individuals subtract the average cost for their Bitcoins from the selling price. If the result is positive, the whole profit will be taxed with 30 percent. If the results are instead negative, the loss is deducted by 70 percent. The average cost is, in general the actual cost for the Bitcoin. However, since the approach to acquire Bitcoin can differ, there are also different approaches in order to calculate the average cost. If the Bitcoin is purchased, the average cost equals the amount paid for them. If Bitcoin is acquired through mining, the average cost equals the market value in SEK in the allocation of Bitcoin in the mining process. In a situation where Bitcoin is received as a payment in a sole proprietorship, the average cost is determined through the value reported as sales, including the eventual VAT. If the salary were to be paid out as Bitcoin, the average cost would be the value reported as income from employment. If Bitcoin is acquired on several occasions, an average of the average cost should be calculated. However, the so-called “Standard method” where 20 percent of the selling price is used as an average cost is not applicable to Bitcoin.

The STA offers a digital service on their website where it is possible to get help with the calculation of the average cost. The private individual should be able to strengthen the average cost stated in a tax declaration through, for instance, original bank statements from exchange companies or receipts. With trades between wallets, the transactions should be able to verify in the blockchain. Losing control over Bitcoins cannot be equated with a loss, even if losing a key to your wallet makes it impossible to access

13

the Bitcoin, it still cannot be deducted as a loss in the tax declaration. The same view applies to Bitcoins lost due to fraud or a potential hacker attack. Thus, if a trading platform suffers a hacker attack and Bitcoin is stolen, it does not justify loss deduction (Skatteverket, n.d.b).A private individual is responsible for submitting correct information in the income declaration. Providing the STA with incorrect information may consequently lead to a tax surcharge (Skatteverket, n.d.c). Incorrect information can refer to inaccurate numbers, but also if tax obligated income is omitted (SFS 2011:1244, 49 kap. 5 §). In the case of final tax, the tax surcharge is 40 percent of the income tax withheld. Even though it is the individual’s responsibility to submit correct information, there are grounds for evasion. For example, circumstances like age or illness might impact whether tax surcharges are to be issued or not. Furthermore, if an open claim is made on the income declaration, no tax surcharge will be levied (Skatteverket, n.d.d). This means that taxpayers can state in their declaration that they trade with Bitcoin but are unsure of how to declare it. The STA then has a special investigation obligation and does not have the right to impose a tax surcharge (Skatteverket, n.d.e). The STA has a wide-ranging audit mandate, however, the duty to investigate does not indicate that the STA must open an investigation in all situations where a statement in a declaration can be questioned (Skatteverket, n.d.e). The proportion of income declarations investigated is in actuality small, and only a small percentage will, in practice, be subjected to manual investigation and review. The selection is made through different types of risk analyzes and is implemented mechanically. The legislator also assumes that the STA’s auditing operations are centralized on taxpayers who are, due to various aspects, worth investigating (prop. 1989/90:74 and prop. 1993/94:224).

2.2.2 European Union

The European Union’s general tax policy states that the member states themselves determine their tax rates as well as the area of use. However, some areas of national tax rules are monitored by the European Union. Areas monitored are particularly relevant when linked to E.U. enterprise and consumer policies. The E.U. argues that the monitoring contributes to the free movement, eliminates unfair advantages between competitors in different countries, and ensures workers and companies are not discriminated against (European Union, n.d.a). Being a part of the European Union means that Sweden must adapt its legislation to E.U. law and are not allowed to implement laws that contradict E.U. rules. Many laws that are voted by the Council of Ministers at the E.U. level are binding, meaning that even if Sweden voted against the proposition, the country is obligated to follow the regulations. It does not matter if Sweden has national, contrary laws, E.U. law takes precedence over the Swedish law (Sveriges Riksdag, n.d.a.).

Even though the European Commission states that effective and fair taxation is a top priority (European Commission, 2018), there are still no clear guidelines to be found regarding how Bitcoins should be

14

defined (European Union, n.d.b). For example, in Germany, the position of tax on cryptocurrencies differs quite a lot from Sweden. The Federal Central Tax Office in Germany (BZST) treats Bitcoin as private money and not as capital like the STA does. In Germany, sales under 600 euros are evaded from tax. Also, if you hold an investment in Bitcoins for over one year, the profit from a possible sale is not obligated with tax (De Hoon, n.d). The European Union, however, made an important statement regarding the taxation of Bitcoin a couple of years ago. In 2015 the European Court of Justice announced that transactions where a traditional currency is exchanged to the virtual currency Bitcoin, and vice versa, are evaded from VAT liability (European Court of Justice, C-264/14). European Court of Justice is the highest court and, thus, has the last word in the matters (Sveriges Riksdag, n.d.b.). After the judgment in the matter of Bitcoin and VAT, the same perception applies in Sweden (SFS 1994:200, 3 kap. 9 §). Even though the E.U. does not control the regulations Sweden has chosen for Bitcoin, support and guidelines are offered. In order to assist the countries within the European Union to plan and propose their regulations in a correct way, a toolbox has been developed. The toolbox is called the “Better regulation toolbox” and consists of 64 different tools to be used by the countries in the E.U. The initial section of the toolbox concerns the general principles of better regulation and contains the seven following tools: 1) Principles, procedures and exceptions, 2) The Regulatory Fitness Programme and the REFIT Platform, 3) Role of the Regulatory Scrutiny Board, 4) Evidence-based better regulation, 5) Legal basis, subsidiarity, and proportionality, 6) Planning and validation of initiatives, and 7) Planning and validation of initiatives (European Commission, n.d).2.3 Tax Compliance

Within the context of public finance, taxation is of great importance as collected tax revenues finance public expenditures. Common issues in the aspect of public finance are related to individual tax compliance, which is described as the choice to comply- or not to comply with existing tax regulations (Youde & Lim, 2019). In an early theoretical study by Allingham & Sandmo (1972), the connection between taxation, risk-taking, and the individual decision on whether to comply or not with existing tax legislations, has been analyzed. Allingham & Sandmo (1972) describe that individuals would comply with tax regulations when they realized that the probability of detection and penalty was too high in relation to the potential money that could be retrieved through non-compliance. In addition, in Bird & Davis-Nozemack's (2018) manuscript, the role of legislation is described as an influential factor on tax avoidance, where fear is described as a predominant motivational factor for tax compliance. In regard to tax compliance, or rather non-compliance, the concepts of tax evasion and tax avoidance need to be clarified and comprehended in order to proceed with this section of the report. Alm (2019) has defined tax evasion as the deliberate choice not to report the individual income tax to the tax agency. Further, Alm (2019) argues that illegal actions committed for the purpose of not paying taxes are equivalent to tax evasion and can also include actions like report more expenses than entailed, avoid paying obligated

15

taxes or report a lower tax amount than obligated. Tax avoidance, however, is defined as simply minimizing taxes using legitimate methods, thereby tax avoidance is considered legitimate and as complying with tax obligations. To comprehend an individual’s decision to comply with tax obligations or to evade them, one needs to look at tax compliance in relation to the existing theory, i.e., the neoclassical and behavioral theories on tax compliance. Moreover, this chapter will present motivations for tax compliance and the probability of detection.2.3.1 Models of Tax Evasion

The initial neoclassical economic model on tax evasion was introduced by Allingham and Sandmo (1972) and has later been further developed by other researchers. The neoclassical economic model on tax evasion aims to clarify non-compliant behavior as a rational choice, meaning that individuals make a deliberate choice on how much to declare in income taxes on the basis of the benefits gained if getting away as well as the risk of being caught. The neoclassical model presents the motivations behind tax compliance in connection to avoiding being investigated by tax authorities. Allingham and Sandmo’s (1972) research could conclude that individuals would comply with tax regulations when they realized that the probability of detection and penalty was too high in relation to the potential money that could be retrieved through non-compliance. However, the issues of the rational choice theory as the explanation of tax compliance stems from its misrepresentation of the level of tax evasion in relation to what is actually observed. Since audit probabilities and the number of fines are low in the real world, most taxpayers would rationally evade most of their income, but that is not the case. The motivation behind why a rational taxpayer would evade stems from the low audit rate, hence, the low probability of detection makes it rational to underreport income. Furthermore, in order for evasion to be irrational, it would have to be more costly than to comply, hence, fines and penalties would have to be excessively high. This becomes problematic in real circumstances as audits are not completely random and tax authorities often prioritize examining the taxpayers who have previously been detected for tax evasion. This would entail those rational taxpayers would have to modify their expected utility of evasion if they had been detected before. An example of a high tax compliance scenario can be examined through an opportunity-based aspect, provided that the taxpayer is a waged employee. In such cases, the income is automatically reported to the tax authorities, which diminishes their opportunity not to comply. Besides rationality, factors such as social norms, influence, fairness, and perceptions of the outcome are considered to be influencing tax compliance (Hashimzade et al., 2013). These factors indicate that the traditional economic model is not solely able to account for issues within tax compliance.

As a response to the challenges presented by the traditional neoclassical view, the behavioral influence in economics and finance emerged. In contrast to the traditional view, behavioral finance aims to explain the financial markets through models where agents are not completely neoclassically rational. In this aspect, the focus is instead put on the psychological and social factors contributing to a compliant- or

16

non-compliant choice. Some people may never evade tax even though the likelihood of getting caught is low. Instead, this can be viewed as psychological costs since the discomfort of proceeding with an illegitimate action may be more costly than the potential outcome (Barberis & Thaler, 2003). In Cullis and Lewis's (1997) early theoretical study, economic approaches to compliance are exemplified in relation to social psychology. Psychological costs related to tax evasion were presented as a factor that prevents people from non-compliance and arguably stemmed from the fear and public humiliation of being detected, overweighting the potential outcome, thus, making it a psychological cost. Cullis and Lewis (1997) further distinguish the impact of fairness on tax compliance as the concept of either being fair to the government and being fair to other taxpayers. If the quality of government services and publicly-provided goods is poor, taxpayers may think that paying taxes is unfair. Similarly, if taxpayers vary greatly from one taxpayer to another, those who need to pay more shares may think this is unfair. What Cullis and Lewis (1997) further emphasize is that the models that contained behavioral effects can, in general, explain empirical findings to a greater extent than solely the traditional neoclassical model as social influence can have a significant impact on compliance.2.3.2 Motivations for Tax Compliance

Psychological factors such as morale, trust, awareness, and overall social influence can have a great impact on tax compliance. As identified in Luttmer and Singhal (2014) through evidence from laboratory studies and emerging literature conducting field experiments, Tax morale has been found to be an important component of compliance decisions. The concept is described as “the intrinsic motivation to pay tax that affects compliance behavior” and is closely linked to social influence as morality is affected by the surroundings and the willingness to comply with the existing obligations. For instance, in an environment where compliance is the norm, taxpayers will adopt the actions of other compliant taxpayers. Thus, as tax morale increases in society, it could lead to an improvement in tax compliance which makes tax morale an integral component within tax compliance. Additionally,

Taxpayer awareness is an additional psychological factor influencing tax compliance that has been

identified in Anto et al. (2021) analysis of taxpayers through multiple linear regression. The concept is described as the taxpayers' comprehension of the tax obligations and encompasses what taxes one is obligated to pay as well as how to proceed. Therefore, to improve tax compliance, one would need to be educated and aware of one’s compliance obligations. The taxpayers were found to voluntarily comply with tax obligations if they comprehended their obligation to pay various taxes. Anto et al.’s (2021) argumentation can be linked to Swedish taxpayers and the Tax Error Model developed by the STA. The model describes how different factors can affect the risk of tax error. The measures implemented by the STA in the model are divided into four main categories where one of them is guidance. Through guidance, the STA aims to ensure that information is easily accessible and that taxpayers have knowledge of how the Swedish tax system is structured and works (Skatteverket, 2017; Skatteverket, 2018). Furthermore, in Kirchler et al. (2008) slippery slope framework, economic factors

17

such as tax audits and fines are assumed to represent the power of authorities which in turn could cause forced tax compliance. On the contrary, psychological factors of tax behavior lead to trust in authorities, which instead could result in voluntary tax compliance. Thus, the concept of trust- and power of taxauthorities are central within the framework where trust refers to the taxpayer being influenced by their

belief that the tax authorities' motives are of good intentions whilst power refers to the perception of the probability of being detected. This has further been demonstrated in Kogler et al. (2013) study, where different assumptions of the slippery slope framework were tested by displaying different scenarios of trust and power to the participants. Kogler et al. (2013) found that a high-trust relationship between respective parties would motivate voluntary tax compliance. Furthermore, what could be obtained was a connection between high- and low trust and an increase- and decrease in tax compliance. Additionally, an increase of trust for tax authorities could be observed when they obtained a greater ability to detect non-compliance, which came to have an influence on voluntary tax compliance. After investigating the Swedish tax system and the public opinion of it, Vogel (1974) states that evasion breeds evasion. Further, Vogel (1974) argues that even if tax evasion is condemned by most Swedes, there still are many that practice it. Evasion can arise as a result of both disseminating information on how to get around the tax regulations and by instilling distrust in those whose honesty compels them to bear the burden of those who cheat (Vogel, 1974). The authors are aware that Vogel’s statement can be argued to be outdated since much has happened in Sweden, both in society and the regulation of taxation since the mid 70’s. However, it is the newest peer-reviewed source to be found in the subject that only focuses on Sweden and is therefore considered, with a critical interpretation, to contribute to the work of addressing the research question.

As previously mentioned, Allingham & Sandmo (1972) have found tax compliance to be related to the perceived risk of being audited and fined. However, additional demographic factors such as age, gender, income, and psychological factors may also be influential in regard to compliance. In Alm’s (2019) paper on what motivates tax compliance, an analysis of TCMP-data (Taxpayer Compliance Measurement Program) suggests lower indications of compliance for individuals who are younger, single, and self-employed. Additionally, the findings indicate that individuals who are male, younger, and who do not prepare their own taxes for declaration themselves are more inclined to decrease their compliance. In Kastlunger et al. (2010) study, decision-making experiments were performed in 60 experimental periods to examine tax compliance of women and men. Women were found to be more risk-averse and compliant in general, however, there were indications of women evading taxes, although, to a smaller extent than men. Furthermore, Kastlunger et al. (2010) argue that differences in tax compliance among women and men may be due to differences in morality and risk aversion as women were found to overestimate the probability of detection in comparison to men.

18

2.3.3 Probability of Detection

A taxpayer's compliance decision is a choice made under uncertainty, the motive for this is that the choice to not comply by not declaring full income does not necessarily result in a penalty. The two strategies of choice that are recurring are to either comply and declare the full income or not to comply and declare less than what is obligated. If the taxpayer chose not to comply, the payoff would be unexpected as it is dependent on whether the individual is detected by tax authorities. As argued by Youde & Lim (2019), the probability of detection represents the possibility for tax authorities to detect illegitimate actions committed by compliant taxpayers. The capability of identifying tax non-compliance would be beneficial for tax authorities as it enhances the level of detection, hence, a great detection level implies that tax authorities have the ability to detect non-compliance. Furthermore, an increase in tax audits leads to an increase in the probability of detection. Hence, when taxpayers interpret the probability of detection as high, tax compliance increases. In a study conducted by Klepper and Nagin (1989), 163 master students were asked about their opinions on tax compliance and perception of risk through a survey. One of their conclusions was that taxpayers appear to calculate their decisions by weighing the benefits and costs of non-compliance. Hence, the benefits from withholding income must outweigh the losses if you are detected.

From the STA’s standpoint, various control measures are carried out with the aim to minimize tax errors which entails examining that the declaration information is correct. The STA uses control measures and guidance to detect intentional errors and inform taxpayers of their obligations. What these activities have in common is that they, according to the STA, create a preventive effect that enables the authority to prevent tax errors to a greater extent than only direct control can. The preventive effect can be defined as taxpayers choosing to avoid cheating and instead pay the right tax due to the perceived risk of detection. Either the preventive effect prevents a tax error by creating a fear of being detected in the event of a deliberate error declaration, or errors can be prevented in advance when unconscious errors are remedied with sufficient information. It is further described by the STA that the tendency to pay taxes is affected by perceived justice, how taxes are used, and the prevailing norms regarding tax evasion in society. It is clarified that significant background factors to citizens’ attitudes and acceptance of tax evasion are social factors such as prevailing societal norms. Societal norms are a broad concept and contain different definitions. Normally, they are defined as normative behavioral expectations, although it can also be about perception and attitude. The STA conducted a citizen survey aimed at the general public’s opinion on the general tax system, tax evasion, and the STA’s preventative work. What could be obtained was that there is a social perception or norm that many people avoid tax or that the tax system is incorrect and deficient, which gives rise to an indirect acceptance of consciously paying incorrect tax (Skatteverket, 2017). Furthermore, Welch et al. (2005) argue that the risk of being detected and sanctioned for tax offenses needs to be perceived as great in order for individuals to choose to comply with tax obligations. The STA (2017) citizen survey found that the social dimension of the

19

embarrassment of being detected and sanctioned is important in this regard. This includes the social stigma of being stigmatized as a “tax evader”, including the fact that the experience of the risk of being detected is described to have increased and that more people perceive the consequences of tax offenses as serious. This can be linked to the traditional neoclassical view where Wahlund (1991) argues that the choice of non-compliance involves a deliberation between financial gain and an “expense” of a bad conscience, where the experience of the severity of the act entails a greater social and moral cost for the individual. Wahlund (1991) argues that if an individual considers the moral expense to be greater than the financial gain, the person will not commit tax evasion due to his moral standpoint. However, an individual’s moral perception can change if individuals develop a more accepting perception of the action, which, according to Wahlund (1991), occurs the more one evades taxes. An additional argument by Wahlund (1991) is the overall attitude in reference to criminality which has a great influence on the perception of tax evasion from a social perspective. As the more serious the act is considered to be, the more the tendency increases for alternative actions, and the higher perceived risk of being detected leads to a diminished tendency to avoid tax. Thus, the severity of tax avoidance is determined by the risk of being caught (Wahlund, 1991).20

3. Methodology and Method

___________________________________________________________________________

This chapter will present the methodology for the research including the research- philosophy, approach, and strategy. Furthermore, the method for the study will be presented which includes the data collection, the sampling technique and the analysis method. In the end of this chapter the reliability and validity of this study is discussed.

___________________________________________________________________________

3.1 Methodology

3.1.1 Research Philosophy

The research philosophy represents what the researcher sees as knowledge, truth and reality. The base of a research should build on the ability to reject or adopt a philosophy. Thus, it is important to understand which paradigms to use as guidance through analysis and research methods (Ryan, 2018). According to Collis and Hussey (2014) there are two main paradigms in research philosophy; positivism and interpretivism, and to design a study the framework of paradigm is needed. To create that framework, the study needs to be evaluated as broadly interpretivist or broadly positivist. The approach of an interpretivist is qualitative, subjective, humanist and phenomenological. Looking at positivism the approach is quantitative, objective, scientific and traditionalist. Based on these assumptions this study is primarily identified through positivism since it is built on data collected through a survey. This study also implements data collected from, and selected of, the STA, which also is a methodology associated with positivism. Further, Collis and Hussey (2014) argue that positivists believe that knowledge is gathered through a measurable and observable phenomena and comes from objective evidence, which is in line with the research process of this study. Due to the lack of former studies within this area, the research question is addressed in a wider perspective with more alignments than one. Even though the study is conducted to be positivist, the research also includes collecting some information through interviews. Thus, the research is influenced by interpretivist through its qualitative, subjective, humanist, and phenomenological angle.

3.1.2 Research Approach

This study aims to fill a gap in existing knowledge of tax evasion linked to profits made from trades with Bitcoin. By addressing the research purpose and an in-depth analysis of which individuals who declare profits from Bitcoin in their declaration and which individuals who does not, the study contributes to fill an existing gap. Easterby-Smith et al. (2018) highlights the importance of choosing a methodological framing suitable for the theoretical question, otherwise, it may have a negative impact on how the research question is answered and the direction of the research purpose.

21

The nature of this study is considered to be explorative. With an explorative approach the goal is not to test a hypothesis, instead the study aims to investigate if there are any patterns or new ideas linked to the research question. The outlines of this strategy are due to the lack of information and previous studies within the subject. Implementing an explorative approach, the usage of observations, case studies and historical analysis are typical techniques to address the research question. Thus, this approach can contribute to both quantitative and qualitative data. Due to few constraints regarding which type of data to collect and activities employed, the techniques used in the explorative approach makes the research process very flexible (Collis & Hussey, 2014). However, even though the positivism approach mainly results in the choice of a quantitative research method, it does not mean that the researcher exclusively chooses that method (Saunders et al., 2016).By using the exploratory approach, the researchers are able to conclude if there are existing concepts and theories that can be applied to the problem or if the research question requires development of new ones. Instead of providing a conclusive answer, taking an explorative approach often leads to ideas and recommendations for future research. Since there are no theories to be found directly connected to the research purposes, the study aims to analyze both quantitative and qualitative data and conclude if there are any patterns to be found among tax evasions and Bitcoins, the research questions will be addressed from an explorative approach (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

For this study, the two methods investigated further are deductive and inductive research. The most suitable approach for the study is concluded to be inductive research. This conclusion is based on the outlines of inductive research, implying an approach where the researcher begins with gathering relevant data for the topic, implementing, and analyzing it and then, as a final step, develop a theory. This study’s main focus is to analyze data collected from a survey and interviews in order to determine if there are any factors to be found that impact tax evasions related to Bitcoin trade. With this research purpose, it is not appropriate to use the deductive research method. Compared to the inductive research method, deductive research can be explained as an approach beginning in the other end of a research circle. This means that the researcher starts off by identifying a theory and then tests it by empirical observations. Since there are no theories to be found regarding the research purposes, the inductive method as the main approach is preferable (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

3.1.3 Research Strategy

The methodological choice of research strategy for this study is quantitative. A quantitative strategy is in line with positivism and is often described as a procedure of data analysis, for example statistics and graphs, or a data collection technique such as surveys. Using a quantitative strategy is mostly associated with a deductive research approach. However, the quantitative strategy can also be incorporated in an inductive approach (Saunders et al., 2016).