1

Responsibility and Biodiversity

Analyzing the EU 2020 Biodiversity Strategy

Mattias Lindberg

Environmental Science

Bachelor Programme in Environmental Science

15 ECTS-credits Spring/2019

2 Abstract

The European Union biodiversity strategy 2020 has soon run its course, and it is time to start assessing its success as well as its weaknesses. As the degradation of ecosystems and loss of biodiversity continues to speed up, the importance of political governance and policy makers’ approaches toward a sustainable use of ecosystem services, and loss of the loss of

biodiversity, is greater than ever. With six targets and 20 actions to reach these goals, this study analyzes their content and context to see if responsibility, with regards to approach, has an impact on the productivity of the action, and the strategy. This has led to the creation of a model, mapping the actions and specific codes in an effort to find a relationship between the approach (direct and indirect responsibility) and productivity.

Keywords: Responsibility, Biodiversity, Environmental Responsibility, Approach, Strategy.

Sammanfattning

Europeiska Unionens strategi för biologisk mångfald 2020, har snart avklarats, och tiden är inne för att bedöma strategins styrkor och svagheter. Allt som nedbrytningen av ekosystem och förlust av biologisk mångfald fortsätter att öka, är betydelsen av den politiska

beslutsprocessen och politikers tillvägagångsätt mot ett hållbart utnyttjande av

ekosystemtjänster större än någonsin tidigare. Med sex huvudmål och 20 åtgärder för att nå dessa mål, analyserar denna studien innebörden och kontexten av dessa åtgärder för att se hur ansvar i förhållande till tillvägagångssätt har en inverkan på åtgärdens samt strategins

produktivitet. En modell skapades för att visa de specifika koderna, och relationen mellan tillvägagångsätt (direkt och indirekt ansvar) och produktivitet.

3

Table of Contents

Introduction ... 5

UN and Other International Conventions ... 7

Theory: Governance of Problems ... 8

Responsibility in Theory and Practice... 10

Method: Qualitative Data Analysis ... 12

Theoretical Sampling and Coding (Grounded Theory) ... 12

Model ... 12

Examples of Decision and Vision ... 13

Definitions and Clarifications ... 15

List of Targets and Actions ... 18

Results: Dissecting the EU Biodiversity Strategy ... 20

Target 1 - Protect species and habitats ... 20

Target 2 - Maintain and restore ecosystems ... 21

Target 3 - Achieve more sustainable agriculture and forestry ... 21

Target 4 - Make fishing more sustainable and seas healthier ... 22

Target 5 - Combat invasive alien species ... 22

Target 6 - Help stop the loss of global biodiversity ... 23

Discussion ... 25

Finishing words ... 28

References ... 30

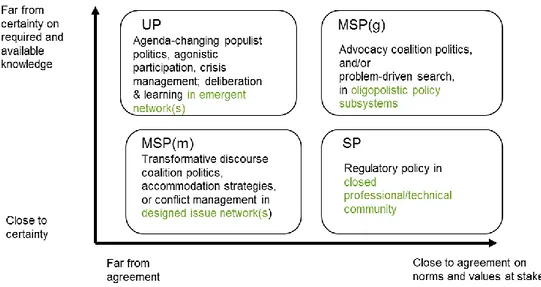

Figure 1. Problem types and type of problem in governance style (Hoppe & Wesselink, Comparing the role of boundary organizations in the governance of climate change in three EU member states, 2014) explains the strengths and weaknesses of different governance styles. “SP = structured problems, MSP(g) = moderately structured problems with goal consensus, MSP(m) = moderately structured problems with means consensus, UP = unstructured problems”. ... 9

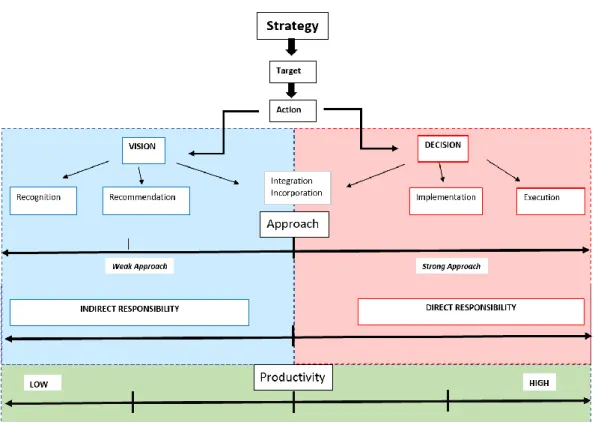

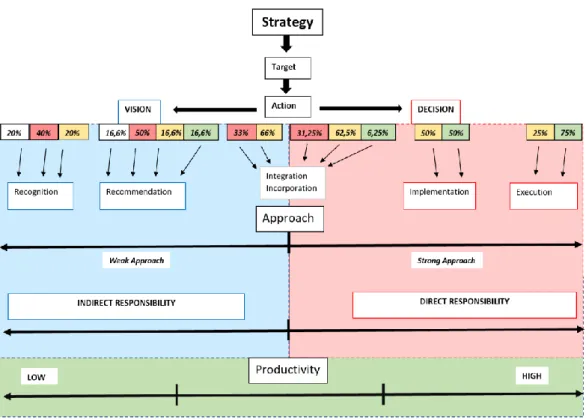

Figure 2. The model illustrates how the strategy is broken down and the analysis of actions in each of the strategy’s targets. ... 13

Figure 3. The figure illustrates the outcome of the analysis. The numbered boxes show the amount of actions that was coded the same, the color shows how far they have been met. The color green means that the action is completed or met, yellow means the partially completed or met, and red means that the action is not completed or met. ... 24 Figure 4. The figure illustrates the outcome of the analysis. The numbered boxes show in percentage the division of the result per coded approach. The color shows how far they have

4 been met. The color green means that the action is completed or met, yellow means the

partially completed or met, and red means that the action is not completed or met. ... 27

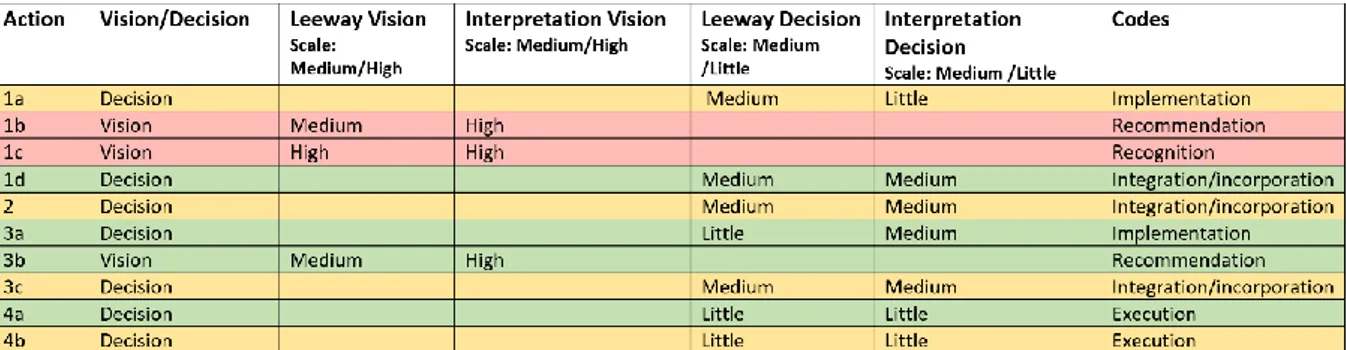

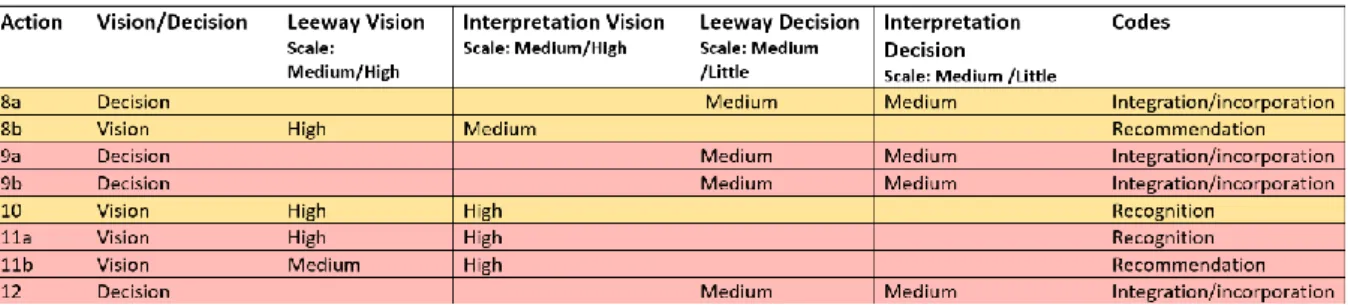

Table 1. The figure shows how the analysis of each action was coded and given a code word to be used in the model for target 1. The color green means that the action is completed or met, yellow means the partially completed or met, and red means that the action is not

completed or met. ... 20 Table 2. The figure shows how the analysis of each action was coded and given a code word to be used in the model for target 2. The color green means that the action is completed or met, yellow means the partially completed or met, and red means that the action is not

completed or met. ... 21 Table 3. The figure shows how the analysis of each action was coded and given a code word to be used in the model for target 3. The color green means that the action is completed or met, yellow means the partially completed or met, and red means that the action is not

completed or met. ... 21 Table 4. The figure shows how the analysis of each action was coded and given a code word to be used in the model for target 4. The color green means that the action is completed or met, yellow means the partially completed or met, and red means that the action is not completed or met. Two colors in the same cell means that because of regions, parts of the action is partially met, and parts in not met. ... 22 Table 5. The figure shows how the analysis of each action was coded and given a code word to be used in the model for target 5. No action in target 5 has been updated regarding

progress, thus no color in the model. ... 22 Table 6. The figure shows how the analysis of each action was coded and given a code word to be used in the model for target 6. The color green means that the action is completed or met, yellow means the partially completed or met, and red means that the action is not

5

Introduction

Biological diversity (biodiversity) and ecosystem services play an important role in the wellbeing of the natural environment, which society then benefits from (Ecologiocal Society of America , 1997). That includes a variety of recourses like, for instance, different food resources thanks to pollenating bees and clean water in the river. The European Union (EU) has for decades acknowledged the importance of a rich biodiversity and the human gain thanks to ecosystem services. Still, degradation of ecosystem services and loss of biodiversity is an ongoing problem due to anthropogenic changes in the environment, such as climate change. To what degree loss of biodiversity will have an impact on humans and which consequences humans will suffer in the future is still debated.

Biodiversity, according to the United Nations’ (UN) Convention on Biological Diversity, (United Nation, 1992) is defined as:

The variability among living organisms from all sources including, inter alia, terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part: this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems.

It is an umbrella term expressing every count of different living organisms cohabitating with one another. In contrast to the term ecosystems, ecosystems also include the “non-living” (United Nation, 1992) environment, thus the cohabitation between the living and their external environment. Since the definition of biological diversity was coined by Thomas Lovejoy (New World Encyclopedia, 2019) and later re-coined as biodiversity in 1985 by W. G. Rosen, it has changed and been updated, containing more precise parts. Björndahl, Borg and Thyberg (2003) does so by dividing biodiversity into three levels or parts:

1. Environment, containing ecosystems and biotopes 2. Diversity of species and their roles

3. The genetic variation

The first level, environment, containing ecosystems and biotopes, focuses on the different environments that are being discussed, as well as which biotopes and specific properties fit into said environment. The second level, diversity of species and their roles, explains

diversity among species, as well as the key species from which they derive, and the role they play in making the habitat possible for every organism within the same diverse ecosystem. The third and the most essential level, the genetic variation, talks about the genetic pool that makes diversity. The genetic variation, whether within a single population of a specific

6 species or in different species all together, is equally important. These different levels of biodiversity define the entirety of the term, according to Björndahl, Borg and Thyberg (2003). Ecosystem services, such as the timber in the forest, the fish in the lake, fresh water, air, etc. derives from nature (Ecologiocal Society of America , 1997). Our society has access to and gains from ecosystem services but is also dependent on it (Ibid). An important feature of a healthy ecosystem, and trustworthy ecosystem services, is the biodiversity it contains; the complicated chain of and between all organisms and the specific non-living environment they require (Reid, Carpenter, Mooney, & Kartik, 2006).

One issue with ecosystem services is “invisible values, so vital to recognize for sustainability” (Keune, Dendoncker, & Sander, 2014) which makes them easy to take for granted.

The EU published a strategy (2011) consisting of six targets and 20 tasks (actions), further broken down to a total of 37 sub-actions to slow down the degradation created by human action or intervention by 2020. This study will analyze the strategy using a qualitative data analysis as a method, in order to see which approach (meaning how the strategy

addresses/direct the member states) the strategy uses toward member states, what level of responsibility the approach results in (meaning what level of accountability to do or to obey) and how it affects the productivity of reaching the goal of minimizing degradation of

biodiversity. As shown, Farinós (2015) demonstrates the effective nature of applying responsibility or environmental responsibility law as a way of dealing with environmental issues, and has been proven to work more successfully than other more commonly used options, thus the importance with responsibility as a concept.

The purpose is to see if there is a correlation between the EUs approach, direct and indirect responsibilities and the productivity of the strategy. The data collected is compared and analyzed further with the help of the theory, Governance of Problems, introduced by

Hisschemöller and Hoppe in 1996, that analyzed political landscapes, different targeted issues and controversies, and how to cope with them (Hoppe & Hisschemöller, 1996). For the sake of this study, a model was created, illustrating how the strategy is broken down and how the analysis of actions in each strategy’s target could correlate between approach, responsibility and productivity. Lastly, together with the empirical data, my model will be fitted into the model taken from Hoppe & Wesselink’s (2014) article, and, in so doing, I hope to answer the question: What approach is the most effective for the EU to use in the 2020 strategy, in applying responsibility, in order to reach the goals set for minimizing loss of biodiversity? This will then be wrapped up with an environmental perspective on political or socio-political

7 issues that, if not managed, affect the potential productivity in reaching the EU´s

environmental goals.

UN and Other International Conventions

Worries for the nature as a system of its own, affected negatively by human intervention, started evidentially before the definition of biological diversity was coined (Mauz & Granjou, 2011). Concerns from academics and scientists can be traced back to the 1960s but did not get any public or political attention at the time. When biological diversity was re-coined to

biodiversity in 1985 by W. G. Rosen, the issue raised more recognition or “reception” from both biologists and the public (ibid). This later resulted in the first major policy-making convention regarding biodiversity in Rio de Janeiro, organized by the UN in 1992, which also led to political recognition worldwide. After that, several international publications were released regarding the subject, and biodiversity started to become a well-known

environmental political subject internationally. Since then, numerous conventions and meetings have taken place to discuss how to go forward. To name a few (United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2005), (UN Environment, a, 2019):

- 2002, World Summit on Sustainable Development, Johannesburg, South Africa - 2005, International Conference on Biodiversity: Science and Governance, Paris,

France

- 2018, UN Biodiversity Conference, Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt

More so, several biodiversity related conventions have taken place (UN Environment, b, 2019):

- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)

- Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals - The International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture - Convention on Wetlands (popularly known as the Ramsar Convention)

- World Heritage Convention (WHC)

- International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC) - International Whaling Commission (IWC)

Knowledge about the subject biodiversity is not unknown from both governments and

academics, rather the subject is quite discussed, and problems humans are facing in regards to loss of biodiversity are often brought to attention, as seen on the list above. The issue that frames this study lies at the measures and solutions brought to the table from international organizations, specifically the EU, and why they in the end seem or are so ineffective.

8

Theory: Governance of Problems

What is mainly discussed in Governance of Problems, introduced by Hisschemöller and Hoppe (1996), is political controversies and how to cope with them. One focal point the article works to solve is to “point out” what makes a strategy a failure as well as a success. Hisschemöller & Hoppe (1996) further argue that “policymakers show the inclination to move from unstructured problems to more structured ones“, and tend to “limit the participants in the policy arena […] range of politically acceptable arguments – i.e. policy choices”, and play a sort of bias in “different policy strategies”.

Hoppe & Wesselink (2014), do the same, but use three European countries as the analyzing targets, and describe terms like “boundary organizations”. What is meant by boundary organizations is best described in the article, which states:

Boundary organizations are the formalized manifestation of boundary arrangements, a wide variety of collaborative configurations that straddle and mediate the boundary between professional-academic net-works and public sector or policy organizations. The role of boundary arrangements is to organize the productive interaction between science, policy and politics (Hoppe & Wesselink, 2014).

What relevance these boundary organizations have, is placed on the importance they ultimately have in political decisions, where IPCC is an example of a well-established boundary organization.

Which particular attribute(s) of different political decisions create greater productivity is hard to identify, specifically to find a causation. Taking into consideration that “political cultures” and “regulatory styles” have an impact on new policies and policy issues regarding

environment, the model “Problem types and type of problem in governance style” (Hoppe & Wesselink, 2014) is a good tool to use for analyzing the result of the qualitative data analysis. What the model shows (see Figure 1) are the different “spheres”: Unstructured Problem (UP); Moderately Structured Problem with Goal consensus (MSP,g); Moderately Structured Problem with Means Consensus (MSP,m); and Structured Problems (SP), all of which assist in describing governance problems, where they are common and how close/far they are from certainty and agreement.

9 Figure 1. Problem types and type of problem in governance style (Hoppe & Wesselink, 2014) explains the strengths and weaknesses of different governance styles. “SP = structured problems, MSP(g) = moderately structured problems with goal consensus, MSP(m) = moderately structured problems with means consensus, UP = unstructured problems”.

We can outline the EU strategy targets in the model to see the overall position of the strategy, the targets and the EU takes in the model, and analyze to what effect the choice of

governance, and its problems, has on the productivity. This parallel to responsibility and approach, which are analyzed in this study (see Figure 2) can give a general correlation of the strategy’s productivity.

10

Responsibility in Theory and Practice

Responsibility is defined as “the state or fact of being responsible, answerable, or accountable for something within one's power, control, or management”, which constitutes “A particular burden of obligation upon one who is responsible.” (Dictionary, 2012). This means that the state or organization responsible for biodiversity, wherever it may be, is accountable and obligated to look over the issue. Farinós (2015), explains how responsibility, in more legislative terms, has a fundamental value in environmental protection. He states:

Environmental Responsibility law and the Regulations that partially develop it, have provided the Spanish legal system of a solid support and major weapons to prevent, anticipate and repair actions that occur, will occur or might occur to the environment. (Farinós, 2015).

Responsibility seems to be a key factor in making progress in environmental issues, such as biodiversity; however, responsibility is not always as simple as it may seem. Bukovansky (2012), in the book “Special Responsibilities: Global Problems and American Power”, first asks the question “can states have responsibility” and lays out two criteria that compare the state to the individual.

The first criteria is if a state is a moral agent, as individuals are, and the second is if ‘the capacity to then act in such a way as to conform to these requirements’ (Bukovansky, et al., 2012). Two arguments are commonly used in confirming the first criteria: ‘They have a) identities different from the identities of their individual constituents, and b) the capacity for deliberation and decision-making’. For the second criteria, they express “different states have different capacities to act in response to their moral deliberations, to fulfil their

responsibilities”, thus concluding that states can have responsibilities equal to individuals. One issue in making responsibility a main path toward the minimization of biodiversity degradation is that it requires an authority that could carry consequences on to member states. Bukovansky, et al. (2012) further explains, “Responsibility is a quality we ascribe to actors […] The term is correctly applied to actors only, to those capable of answering or accounting for the things they do or fail to do. Parents are not responsible for the care of their children simply because they can affect their well-being, but because most societies deem them answerable and accountable for that well-being” (Bukovansky, et al., 2012). In terms of environmental protection, this would mean that there needs to be a sovereign force which could carry these consequences to states, one that does not recognize the impact they have on

11 biodiversity or act in agreeance or complete agreeance with the Rio Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). The problem with this, as Bukovansky, et al. (2012) mentions, is that there has never been a single sovereign power to bring solutions to global problems. Instead, Bukovansky, et al. argues that the most effective way to solve global problems is “managed through regimes of special responsibilities that have, in turn, generated a distinctive politics of responsibility” (ibid). The question then is, does the European Union (EU) fit into that

description, and how has it gone for the member states of the EU regarding degradation of biodiversity? EU is one of the most advanced supranatural organizations, with highly incorporated environmental legislations, directives, objectives and more. Environmental problems and solutions are discussed, voted on and sourced in both the European Parliament, European Commission, Council of Ministers (the Council), the European Environmental Bureau (EEB) and the European Court of Justice (ECJ) (Connelly, Smith, Benson, & Saunders, 2012). All of these actors have some influence or power to affect or change environmental regulations and, at least to some extent, place responsibility or accountability onto those whom choose not to abide by said regulations. As it stands, loss of biodiversity is actually increasing (European Environment Agency , 2016), despite the enactment of several strategies, numerous directives and legislations. An important factor to consider is the legal framework and policies, released and implemented by the EU, are not directly mandated or enforced. Mostly, the policies and legislation consist of non-binding commitments, voluntary agreements and legal directives which work “between governments and industry, with self-regulated management standards” (Connelly, Smith, Benson, & Saunders, 2012). This means that whatever the EU decides and implements, the ultimate responsibility is put on the

12

Method: Qualitative Data Analysis

To analyze the strategy published by the EU Commission, I use a qualitative data analysis in accordance with Bryman (2004). The main part of the method consists of “theoretical sampling” and coding of the text (Bryman, 2004); in this case, the strategy.

The analysis is done using a hermeneutist and qualitative perspective, thus enabling the interpretation of the meaning and an understanding for the context the strategy’s actions are embedded in. After the actions are interpreted and the context analyzed, they are coded to fit specific code words, to then be analyzed again, and fitted in even more narrow code words, giving the action a certain responsibility and productivity value (see Figure 2 and “Model” on page 12 below).

Theoretical Sampling and Coding (Grounded Theory)

This section of the study is close or equal to the “Grounded Theory” from Glaser and Strauss (1967), leading the path of the qualitative data analysis method. Theoretical sampling

according to Bryman (2004) is, “ the process of data collection for generating theory whereby the analyst jointly collects, codes, and analyzes the data and decides what data to collect next and where to find them, in order to develop his theory as it emerges”. This process in this study is the written content of each individual action’s characteristics, meaning the feature or the quality defining the underlying intention of the action and the context the action is

surrounded in. The coding process is also dependent on comparison, as Bryman (2004) says, “It refers to a process of maintaining a close connection between data and conceptualization, so that the correspondence between concepts and categories with their indicators is not lost”, meaning one code is only X if the other one is that of Y.

Model

To accurately be able to analyze the content and the context, in which the strategy is written, I have created a model to visually demonstrate the overall analysis (see Figure 2).

13

Figure 2. The model illustrates how the strategy is broken down and the analysis of actions in each of the strategy’s targets.

The strategy consists of six targets describing what changes to make in each area (forests, marine life, global, etc.). The target then includes actions, which specifically and more narrowly describe what member states should, ought to or have to do in the area the target frames. These actions, when analyzed, are coded as vision or decision and placed on either the left (blue box) or right (red box), see Figure 2.

The left box, titled Vision, means the action is:

- Vision entails the act of doing, but where much to some leeway is allowed and interpretations are expected for the course of action.

The right box, titled Decision, means the action is:

- Decision entails the act of doing, more specifically acting, in a manner where little to no leeway or interpretation is allowed for the course of action.

Examples of Decision and Vision

Decision – “Action 1a) Member States and the Commission will ensure that the phase to establish Natura 2000, including in the marine environment, is largely complete by 2012.” (European Comission, 2016).

14 What must be done is to establish the Natura 2000 “Within the legal framework provided by the Birds and Habitats Directives”, and to do it by 2012, which is fairly clear. What does not make this an execution is the word “largely”, implying the action does not have to be done. Vision - Action 1b) Member States and the Commission will further integrate species and habitats protection and management requirements into key land and water use policies, both within and beyond Natura 2000 areas.

What must be done is to integrate species and habitats protection and management requirements into land and water use policies. Interpretation is high when using the terms “further” and “key”. This gives space for member states to decide, push and pull the action themselves. Leeway is medium when the subject and goal is more clear.

After deciding the box the action fits into, analysis is made of the content of the action to determine what approach the action has toward member states. These are recognizing, recommending, integrating/incorporating, implementing and executing the action. How the action is applied to these codes depends on the leeway and the interpretation. In other words, if an action is to fit in vision, having “high” leeway and “high” interpretation for member states to go in accordance with it, the action will fall under recognition. If the action would instead have “medium” leeway, but high interpretation, it would fall under recommendation. Lastly, if the action would have “medium” on both leeway and interpretation, it would fall under integration/incorporation. The same coding method is used for decision, but with little and medium leeway and interpretation.

Which of these code words the action is applied to will determine the responsibility, direct or indirect, the action will have and what productivity that entails.

15

Definitions and Clarifications

To create the model and to analyze the strategy, key words were defined and placed differently in the model based on the expected responsibility connected to the action of the word.

Responsibility, as mentioned in the section “Responsibility in Theory and practice”, on page

9, is “the state or fact of being responsible, answerable, or accountable for something within one's power, control, or management”; this constitutes “A particular burden of obligation upon one who is responsible.” (Dictionary, 2012). In this study, I have split the term responsibility into two parts, indirect and direct responsibility.

Indirect responsibility, with the same meaning as responsibility above, indirect responsibility

also includes expected accountability of obligation, where direct responsibility is more pinpointed and describes a framed accountability of obligation.

Approach means “to make advances to; address” and/ or

“present, offer, or make a proposal or request to begin to work on; set about” and “A way of dealing with something” (Dictionary, 2012). The different frameworks used in this study when looking at the various approach the codes have, is what authority the EU have

delegating the tasks or addressing the receiver (the member states) in the individual actions. This means that a weak approach lacks authority (legal force or efficiency) addressing the receiver, or controlling other members states’ actions, whereas a strong approach has authority in addressing the receiver, or controlling the member states’ actions.

Vision is defined as “Anticipating which will or may come to be or happen” (Dictionary,

2012), but has more layers compared to the dictionary definition. Vision in this study is an action in the strategy, meaning something someone else has to do, which includes an

approach to the receiver and a responsibility from the receiver. As seen in Figure 2, it means the approach is weak (lacks authority), and the responsibility followed is indirect (expected accountability of obligation). As explained earlier, when analyzed, the vision part also

includes leeway and interpretation, which is what determines the type of approach (code word in the model, see Figure 2) the vision has.

Decision is defined as “the act or process of deciding; determination, as of

a question or doubt, by making a judgment” and “a conclusion or resolution reached after consideration” (Dictionary, 2012). Equal to vision, it is layered with more meaning and means, as an action, something someone else has to do and entails a strong approach (has

16 authority) and direct responsibility (pinpointed and framed accountability of obligation). This too, when analyzed, includes leeway and interpretation to determine the approach.

Recognition is one of the code words that makes up part of the analysis under vision or, more

exact, of the approach the individual action has. Because it is a code word for an approach, from an action in the strategy, it means that someone is asking something of you. The definition is “The acknowledgment of something as valid or as entitled to consideration. The perception of something as existing or true” (Dictionary, 2012). Recognition is the weakest approach in the model, where “basically” just acknowledgment is what is mostly expected. It also means that the action has a potential outcome as if the member state just acknowledged it. An example is “Member States and the Commission will encourage the adoption of Management Plans […]” (European Comission, a, 2016), a part of the 11a action that was coded to be approach recognition. If looking into what leeway and interpretation this has, it was considered high on both points, due to the vagueness of encouragement and lack of what is expected from not just the member states, but the member states’ receivers.

Recommendation is defined as “a suggestion or proposal as to the best course of action” and

“representation in favor of a person or thing” (Dictionary, 2012). This is also is an approach from an action but, in contrast to recognition, proposes the “course of action” which makes it more specific. For it to be a recommendation instead of recognition, it will have either medium interpretation (somewhat a meaning of it) and high leeway (completely free to choose how to go about it) or high interpretation (completely free to understand it how you want) and medium leeway (somewhat saying how to go about it).

Integration/Incorporation means “to bring together parts into a whole” (Dictionary, 2012),

and is under both vision and decision. As an approach, it works equally for both decision and vision, as it asks to apply something into what currently exists. This makes it a stronger vision, acting as the changing or adding of something or bettering what currently exists, which ensures somewhat of a change. It is the weakest form of a decision as it still has some level of uncertainty. If the action is set on vision, it must have medium leeway and medium interpretation which is the same for decision, making integration/incorporation merely based on which side of the model it lands on.

Implementation is the second strongest approach, and means “the process of putting a

decision or plan into effect” or simply “putting into effect” (Dictionary, 2012). By

17 the process of the action is structured enough and able to be applied to member states, then the ability for member states to interpret and change the action lessens. In order for the approach to be implementation, in contrast to integration/incorporation, it requires either leeway or interpretation of the action to be minimal, meaning very little choice for states’ choice of action.

Execution is defined as “to carry out; accomplish” or “to perform or do” (Dictionary, 2012),

and has the most direct and clear approach of all possible categories. This makes it the strongest course of action, with very little interpretation or leeway allowed. It has its position due to the fact that responsibility to the receiver is directly applicable, thus accountability too. That way, it makes it harder for member states to pick and choose or to misunderstand the meaning of the action.

Leeway means the “freedom to act within particular limits” (Dictionary, 2012) and bears the

same meaning in this study.

Interpretation is defined as “an explanation or opinion of what something means”

(Dictionary, 2012) and, more specifically, as what freedom a member state has to understand the action and apply their own meaning to it.

18

List of Targets and Actions

The analysis was done of all the actions each target consists of, listed down below: Target 1 - Protect species and habitats, (European Comission, 2016).

- Action 1: Complete the Natura 2000 network and ensure its good management - Action 2: Make sure Natura 2000 sites get sufficient funding

- Action 3: Raise awareness of Natura 2000, get citizens involved and improve the enforcement of the nature directives

- Action 4: Make the monitoring and reporting of the EU nature law more consistent, relevant and up-to-date; provide a suitable ICT tool for Biodiversity

Target 2 - Maintain and restore ecosystems, (European Comission, 2018).

- Action 5: Map and assess the state and economic value of ecosystems and their services in the entire EU territory; promote the recognition of their economic worth into accounting and reporting systems across Europe

- Action 6: Restore ecosystems, maintain their services and promote the use of green infrastructure

- Action 7: Assess the impact of EU funds on biodiversity and investigate the

opportunity of a compensation or offsetting scheme to ensure that there is no net loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services

Target 3 - Achieve more sustainable agriculture and forestry, (European Comission, a, 2016). - Action 8: Enhance CAP direct payments to reward environmental public goods such

as crop rotation and permanent pastures; improve cross-compliance standards for GAEC (Good Agricultural and Environmental Conditions) and consider including the Water Framework in these standards

- Action 9: Better target Rural Development to biodiversity needs and develop tools to help farmers and foresters work together towards biodiversity conservation

- Action 10: Conserve and support genetic diversity in Europe's agriculture - Action 11: Encourage forest holders to protect and enhance forest biodiversity

- Action 12: Integrate biodiversity measures such as fire prevention and the preservation of wilderness areas in forest management plans

19 - Action 13: Ensure that the management plans of the Common Fisheries Policy are

based on scientific advice and sustainability principles to restore and maintain fish stocks to sustainable levels.

- Action 14: Reduce the impact of fisheries by gradually getting rid of discards and avoiding by-catch; make sure the Marine Strategy Framework Directive is consistently carried out with further marine protected areas; adapt fishing activities and get the fishing sector involved in alternative activities such as eco-tourism, the monitoring of marine biodiversity, and the fight against marine litter.

Target 5 - Combat invasive alien species, (European Comission, 2017).

- Action 15: Make sure that the EU Plant and Animal Health legislation includes a greater concern for biodiversity.

- Action 16: Provide a legal framework to fight invasive alien species

Target 6 - Help stop the loss of global biodiversity, (European Comission, b, 2016).

- Action 17: Reduce the impacts of EU consumption patterns on biodiversity and make sure that the EU initiative on resource efficiency, our trade negotiations and market signals all reflect this objective.

- Action 18: Target more EU funding towards global biodiversity and make this funding more effective.

- Action 19: Systematically screen EU action for development cooperation to reduce any negative impacts on biodiversity.

- Action 20: Make sure that the benefits of nature's genetic resources are shared fairly and equitably.

20

Results: Dissecting the EU Biodiversity Strategy

Analyzing each action for its content and its context, to evaluate how the EU strategy

approach the member states, coding the action and compare it to the actual result released by the EU, will give perspective to if different approaches includes responsibilities that changes the productivity. This chapter provides color coded tables that visually contributes to see what code the actions got, how it well it has gone meeting the action for the member states in reality, and where it fits in my model.

Target 1 - Protect species and habitats

Target 1 is focused on protecting “species native to the EU and the habitats they depend on” (European Comission, 2016), and consists of four actions, spread out to a total of 10 actions including sub-actions (S-A). To reach the target by 2020, the target fixates its actions in areas like “full compliance, efficient management and better enforcement of the EU nature law” (ibid).The analysis placed three of the actions on vision (1b, 1c and 3b) and seven on decision (1a, 1d, 2, 3a, 3c, 4a and 4b), see Table 1.

Table 1. The figure shows how the analysis of each action was coded and given a code word to be used in the model for target 1. The color green means that the action is completed or met, yellow means the partially completed or met, and red means that the action is not completed or met.

As seen in Table 1, vision got two actions placed in the code recommendation (1b and 3b) and one in recognition (1c). Decision got two in implementation (1a and 3a), three in

21 Target 2 - Maintain and restore ecosystems

Target 2 focuses on “maintain and restore ecosystems and their services” (European Comission, 2018), by aiming the actions toward “including green infrastructure in spatial planning […] also ensure protected habitats are better connected, within and between Natura 2000 areas as well as in the wider countryside”. It consists of three actions, and a total of five actions including S-A. Three were placed in vision (6a, 7a and 7b) and two in decision (5 and 6b), see Table 2.

Table 2. The figure shows how the analysis of each action was coded and given a code word to be used in the model for target 2. The color green means that the action is completed or met, yellow means the partially completed or met, and red means that the action is not completed or met.

Two of the actions placed in vision were given the code integration/incorporation (6a and 7a) and one recommendation (7b). Of the two actions placed in decision, one got the code

integration/incorporation (5) and the other got implementation (6b), see Table 2. Target 3 - Achieve more sustainable agriculture and forestry

Target 3 is about agriculture and forestry, which are two of the largest industries affecting biodiversity and, as an industry, it is dependent on biodiversity itself (European Comission, a, 2016). It consists of five actions which totals eight including S-A. Four of the actions were placed in vision (8b, 10, 11a and 11b) and four in decision (8a, 9a, 9b and 12), see Table 3.

Table 3. The figure shows how the analysis of each action was coded and given a code word to be used in the model for target 3. The color green means that the action is completed or met, yellow means the partially completed or met, and red means that the action is not completed or met.

Of the four actions fitted into vision, two of them got the code recommendation (8b and 11b) and two were given recognition (10 and 11a). For decision, all were given the code

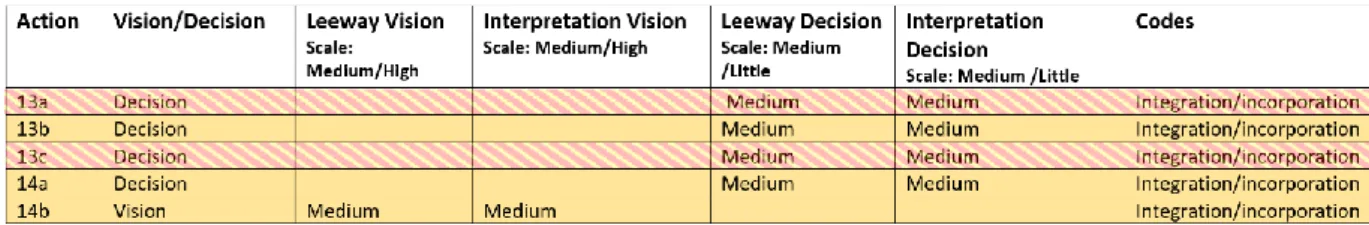

22 Target 4 - Make fishing more sustainable and seas healthier

Target 4 focuses on the fishing industry and seas in or part of the EU. Like Target 3, the fishing industry is the main industry affecting biodiversity, despite being completely dependent on healthy stocks of fish. The EU has two actions in Target 4, altogether 5

including S-A. Out of those, one was placed as vision (14b) and the rest were decisions (13a, 13b, 13c and 14a), see Table 4.

Table 4. The figure shows how the analysis of each action was coded and given a code word to be used in the model for target 4. The color green means that the action is completed or met, yellow means the partially completed or met, and red means that the action is not completed or met. Two colors in the same cell means that because of regions, parts of the action is partially met, and parts in not met.

All of the actions for Target 4 were given the code integration/incorporation (13a-14b), see Table 4.

Target 5 - Combat invasive alien species

Target 5 is about invasive alien species not naturally found in the EU member states’

environment (European Comission, 2017). The target aims the actions toward the problem by “control the pathways of their introduction, prevent their establishment and spread, and manage already established populations”. The European Commission’s main aim is

prevention regarding invasive species because “established populations can be expensive to manage and difficult or impossible to eradicate”.

Table 5. The figure shows how the analysis of each action was coded and given a code word to be used in the model for target 5. No action in target 5 has been updated regarding progress, thus no color in the model.

Target 5 has two actions (15 and 16). Both actions were placed as vision, action 15 got the code recognition and 16 got recommendation, see Table 5.

23 Target 6 - Help stop the loss of global biodiversity

Target 6 is about contributing to the goals agreed upon in the Convention on Biological Diversity, meaning global biodiversity by “greening its economy and endeavoring to reduce its pressure on global biodiversity” (European Comission, b, 2016). Target 6 consists of four actions, seven including S-A. Out of those seven, one was placed as vision (17c) and the rest as decision (17a, 17b, 18a, 18b, 19 and 20), see Table 6.

Table 6. The figure shows how the analysis of each action was coded and given a code word to be used in the model for target 6. The color green means that the action is completed or met, yellow means the partially completed or met, and red means that the action is not completed or met.

Vision got the code integration/incorporation, three of the decisions got implementation (17a, 18a and 19), two got execution (18b and 20) and the last one was given

integration/incorporation (17b), see Table 6.

All actions have been analyzed and coded, a total of 37 including all sub-actions (see

Figure 3). Two “additional” actions were added in

Figure 3 because of action 13a and 13c, which were both partially met and not met (see Table 4). Thirteen of the actions were coded vision, four of those were recognition, six were

recommendation and three were integration/incorporation. 26 of the actions were coded decision, of which 16 were integration/incorporation, six were implementation and four were execution. As seen in

Figure 3, vision has five “not met or completed” (red) actions, distributed between recognition

(two), recommendation (three) and integration/incorporation (one). The same number is found for decision, but where all of the five “not met or completed” are only under

integration/incorporation. Vision has four “partially completed” (yellow) actions, one each for recognition and recommendation and two for integration/incorporation. 14 “partially

completed” actions are in decision, where 10 were in integration/incorporation, three in implementation and one in execution.

24

Figure 3. The figure illustrates the outcome of the analysis. The numbered boxes show the amount of actions that was coded the same, the color shows how far they have been met. The color green means that the action is completed or met, yellow means the partially completed or met, and red means that the action is not completed or met.

Of the “completed” (green) actions, vision only had one under recommendation, whereas decision had one on integration, three on implementation and three on execution. Of the two that do not have a follow up, both are in vision, one in recognition and one in

25

Discussion

Biodiversity is a greatly valuable recourse, commonly taken for granted despite being a natural consequence of being, as in nature in its natural state. The EU estimates that the monetary value of pollinating insects within the EU region alone is at €15 billion per year (European Comission , 2011). Also, the EU valued a “new job sector” with “new

opportunities”, “job skills” and “investments” related to biodiversity, “to be worth US$2-6 trillion by 2050” (ibid).

Biodiversity has an intrinsic value to humans’ economic interests, and an equal value to our welfare or even survival. Still, the rate in which species are currently being lost is “100 to 1,000 times faster than the natural rate” and is “Driven mainly by human activities” (European Comission , 2011).

Whether or not the loss of biodiversity is mainly a behavioral, sociological or political issue in its roots, the fact remains, it is still an ongoing environmental problem. This study tried to look further into responsibility as a matter of fact in the process of minimizing the loss of biodiversity. As shown, responsibility has its function, where Farinós (2015) found the benefit in “environmental responsibility law and regulations […] to prevent, anticipate and repair actions that occur, will occur or might occur to the environment” (Farinós, 2015). This study also focused on policy makers in a supranational organization - the European Union. More exactly, I have tried to highlight how the EU, in its strategy to minimize the loss of

biodiversity, approach the member states and what responsibility could be derived from this approach. The purpose of this study is to see if there is a correlation between the EUs approach, direct and indirect responsibilities and the productivity of the strategy, to answer the question: What approach is the most effective for the EU to use in the 2020 strategy, in applying responsibility, in order to reach the goals, set for minimizing the loss of

biodiversity? To be able answer the question, a qualitative data analysis was done on the strategy’s actions (and sub-actions), to extract the different approaches, what responsibility that entails, which productivity that should have, followed up with the actual progress of the action. This was further developed for easier visual understanding through the model ( Figure 2) which was presented in the chapter “Model“ on page 12. This has then been analyzed with the help of “Governance of Problems”, introduced by Hisschemöller and Hoppe in 1996, and the model taken from Hoppe & Wesselink (2014).

26 As Hisschemöller and Hoppe (1996) explain:

[…] a policy problem is usually defined as a gap between the existing and normatively valued situation that is to be bridged by government action. Since not everyone considers the same situation as

undesirable, policy problems are no objective givens. A problem is a social and political construct. These constructs articulate values as well as facts. What one person considers a matter of fact, another may well consider as a matter of ideology or a lie (Hoppe & Hisschemöller, 1996).

This explains the importance of how the communication and the approach from the EU´s strategy to member states is done as well as when it could change the actual desired outcome. Another important feature that is discussed is, as Hisschemöller and Hoppe (1996) explain:

If a problem is well-defined or structured, it is to be solved by standardized (quantitative) techniques and procedures. The disciplines and specialism to be invoked are clearly defined and the policy-making responsibility is in the hands of the actor (Hoppe & Hisschemöller, 1996).

What is said could be correlated with the empirical data the qualitative data analysis delivered, as well as the hypothesis in this study. The difference between this study and Hisschemöller and Hoppe’s (1996) analysis is their focus on the “problem”, whereas my focus is on the action, to evaluate the approach and responsibility. What is similar is

dependent on how the EU “structured” their actions/problems; the responsibility shifts, and so does the productivity. This is supported by Hisschemöller and Hoppe (1996) explanation:

If a problem is ill-defined […] or unstructrured – technical methods for problem solving appear inadequate. The boundaries of the problem are diffuse, so it can hardly be separated from other problems […] Conflicting values and facts are interwoven, and many actors become involved in the policy process. Hence, these problems are to more explicitly defined as political. Whereas structured and moderately structured problems can move straight from recognition to resolution, unstructured problems are too controversial and ambiguous to do so (Hoppe & Hisschemöller, 1996).

The outcome of the qualitative data analysis shows that decision had seven completed or met actions, where six of those were located at implementation and execution (three each). Vision had one, located at recommendation which, in this analysis, is an outlier. The not completed or met actions were distributed between recognition (two), recommendation (three) and integration/incorporation (six), where one was on vision and five on decision. This is a bit contradictory to my hypothesis, but what has to be factored in is the overall amount of actions that were coded in decision compared to vision (almost double). But for each of the

27 Figure 4. The figure illustrates the outcome of the analysis. The numbered boxes show in percentage the division of the result per code/approach. The color shows how far they have been met. The color green means that the action is completed or met, yellow means the partially completed or met, and red means that the action is not completed or met.

As seen in Figure 4, a big part of the completed action is located furthest on the decision part of the model. 75% of the actions within the execution approach have been completed, and 50% of the actions within the implementation approach were completed. The remaining actions were either partially met or completed. On the other hand, 40% of the actions with recognition as an approach were not completed or met, and 50% of the actions with recommendation as an approach were neither completed or met. It is with confidence one could tell that there is not enough data, when analyzing one single strategy with this method, to confidently test the hypothesis and prove it right or wrong.

As we previously established, states could be seen as moral agents (or actors), and therefore can be held accountable for their actions with regards to responsibility. An issue is the way the EU works around change which, as mentioned earlier, consists of mostly non-binding commitments, voluntary agreements and legal directives that work “between governments and industry, with self-regulated management standards” (Connelly, Smith, Benson, & Saunders, 2012). This means that whatever the EU decides and implements, the ultimate responsibility is to be put on the member states. Which is along the lines of how Hisschemöller & Hoppe

28 (1996) argued around problems not being directed toward the ones with solutions, the

structured ones.

Hoppe & Wesselink (2014) came to the same conclusion when they stated “We find that the climate change policy issue is generally treated as a moderately structured problem with goal agreement”, which on the model “Problem types and type of problem in governance style”, would mean that it is close to agreement, but far from certainty.

A recommendation for another paper would be to analyze the similarity of all the actions that were met, all the actions that were partially met and all the actions that were not met, basically starting with the result instead of ending with it. From there, one would be able to see if there is something that makes an environmental policy successful in regard to responsibility or not.

Finishing words

The loss of biodiversity as an environmental issue is a global problem and requires all parties to participate in the work toward minimizing degradation. We have already concluded that the EU resembles the regimes of special responsibilities, and that the EU could be the sovereign power, a perfect agent for carrying out consequences, holding states and parties accountable for not doing anything or not doing enough. In that way, we should see the member states as actors, who do not act in accordance with what was decided. As mentioned earlier, states could be seen as moral agents and could adapt to the social requirements of being a moral agent, meaning we can hold them accountable. We also know that there is no evidence of a sovereign power working in a global setting, bringing solutions to global issues. This means being careful of whom we attribute power to, and using precautionary principles to guide sovereignty. But responsibility and accountability have been proven to work in solving environmental problems and have the most potential in serious, drastic solutions. How do we enforce a burden of obligation upon the responsible actors, without having a stronger

sovereign power dictating the actors? My take on this would be a combination of both. As we know, legislative directions in environmental protection work, and a sovereign body with too much power is not a good idea, so implementing both could potentially have a greater

outcome. I would argue that a body like ECJ, that would exclusively work with environmental legislation, could be a way of reaching the goal of minimizing loss of biodiversity. This way, you could compromise the sovereignty but uphold the burden of obligation. This would not mean that they are the only body in the European Union working with environment, all

29 sections should still set the goals, visions, directives etc., but only one organ could enforce the responsibility upon member states.

30

References

Björndahl, G. B. (2003). Miljökunskap (1 uppl., Vol. 2). Stockholm, Sweden: Liber AB. doi:91-47-01731-7

Bryman, A. (2004). Social Research Methods (2 uppl.). Oxford: Oxford University Press Inc., New York. doi:10: 019-926446-5

Bukovansky, M., Reus-Smit, C., Wheeler, N. J., Price, R. M., Clark, I., & Eckersley, R. (2012). Special Responsibilities : Global Problems and American Power (1 ed., Vol. 1). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:1107691699

Connelly, J., Smith, G., Benson, D., & Saunders, C. (2012). Politics and the Enviroment:

From Theory to Practice (3 uppl.). Oxon: Routledge. doi:978-0-415-57211-8

Dictionary. (2012). Definitions. Hämtat från Dictionary.com: https://www.dictionary.com/browse/ den 08 04 2019

Dictionary, a. (2012). Approach. Hämtat från www.dictionary.com: https://www.dictionary.com/browse/approach?s=t den 05 05 2019

Ecologiocal Society of America . (1997). Eco System Services: Benifits Supplied to Human

Societies by Natural Ecosystems . ESA.

European Comission . (2011). The EU Strategy to 2020. Luxembourg: European Comission. European Comission. (den 10 06 2016). Protect species and habitats - Target 1. Hämtat från

http://ec.europa.eu:

http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/biodiversity/strategy/target1/index_en.htm den 03 05 2019

European Comission. (den 16 10 2017). Combat invasive alien species – Target 5. Hämtat från http://ec.europa.eu:

http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/biodiversity/strategy/target5/index_en.htm den 03 05 2019

European Comission. (den 16 04 2018). Maintain and restore ecosystems – Target 2. Hämtat från http://ec.europa.eu:

http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/biodiversity/strategy/target2/index_en.htm den 03 05 2019

European Comission. (den 07 08 2019). https://ec.europa.eu. Hämtat från Make fishing more sustainable and seas healthier – Target 4:

https://biodiversity.europa.eu/mtr/biodiversity-strategy-plan/target-4-overview

European Comission, a. (den 10 06 2016). Achieve more sustainable agriculture and forestry

– Target 3. Hämtat från http://ec.europa.eu:

http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/biodiversity/strategy/target3/index_en.htm den 03 05 2019

European Comission, b. (den 10 06 2016). Help stop the loss of global biodiversity – Target

31 http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/biodiversity/strategy/target6/index_en.htm den 03 05 2019

European Environment Agency . (den 15 10 2016). Biodiversity. Hämtat från

www.eea.europa.eu: https://www.eea.europa.eu/soer-2015/europe/biodiversity Farinós, J. M. (2015). Enviromental responsability and corporate social responsability.

Vitruvio: International Journal of Architectural Technology and Sustainability, 0(1),

87-91. doi:10.4995/vitruvio-ijats.2015.4477

Fontaine, C., Haarman, A., & Schmid, S. (2006 ). Stakeholder Theory of the MNC. Hämtat från Semantic Scholar :

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/606a/828294dafd62aeda92a77bd7e5d0a39af56f.pdf Government of Sweden. (2014). En svensk strategi för biologisk mångfald och. Government

of Sweden.

Hoppe, R., & Hisschemöller, M. (1996). Coping with Intractable Controversies: the Case for Problem-Structuring in Policy Design and Analysis. Knowledge and Policy: The

International Journal of Knowledge Transfer and Utilization., 8, ss. 40-60.

Hoppe, R., & Wesselink, A. (12 2014). Comparing the role of boundary organizations in the governance of climate change in three EU member states. Environmental Science and

Policy, ss. 73-85. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2014.07.002

Keune, H., Dendoncker, N., & Sander, J. (2014). Ecosystem Services : Global Issues, Local

Practices (1 uppl.). San Diego, CA: Elsevier Science. doi:9780124199804

Mauz, I., & Granjou, C. (den 15 03 2011). The construction of biodiversity as a political and

scientific problem. doi:10.14758/SET-REVUE.2011.3BIS.04

New World Encyclopedia. (den 05 03 2019). New World Encyclopedia. Hämtat från Biodiversity: http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Biodiversity

Reid, W. V., Carpenter, S. R., Mooney, H. A., & Kartik, C. (11 2006). Nature: The many

benefits of ecosystem services. Hämtat från ResearchGate:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/6745013

UN Environment, a. (den 18 03 2019). UN Biodiversity Conference. Hämtat från https://www.cbd.int: https://www.cbd.int/conferences/2018

UN Environment, b. (den 18 03 2019). Biodiversity-related Conventions. Hämtat från https://www.cbd.int: https://www.cbd.int/brc/

United Nation. (1992). Convention On Biological Diversity. Convention On Biological

Diversity (s. 28). Rio de Janeiro: United Nation.

United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization. (07 2005). International

Conference on Biodiversity: Science and Governance. Hämtat från www.unesco.org: