The impact of

advertising

exposure on

attitudes and

purchase intention

MASTERTHESIS WITHIN: Marketing NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 ECTS PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Civilekonom AUTHOR: Robert Brolin & Carl Spångby TUTOR: Adele Berndt

JÖNKÖPING: 05/20

A quantitative study measuring the impact of

Instagram advertising exposure on attitudes toward

the ads and brands, and purchase intention of

A

CKNOWLEDGEMENTThe authors would like to give special thanks to their tutor, Adele Berndt, for valuable guidance throughout the process of conducting this study. Additional thanks are directed toward Elin Pedersèn and Amanda Persson for providing feedback regularly. Lastly, the authors would like to thank Paragitha Kusuma Wardhani and Dr. M. Gunawan Alif for sharing and translating their Indonesian scales to English.

Jönköping International Business School, Jönköping May 17, 2020

A

BSTRACTThe rise of social media has opened new possibilities of tailored advertising for specific target groups. Simultaneously, the sportswear industry is growing exponentially, raising questions of how to shape social media advertisements to attract consumers in the competitive landscape. This study measures the relationships between Instagram ad exposure and attitudes toward the ads and brands, and whether this leads to increased purchase intention of sportswear. Furthermore, the study aims to investigate the influence of the demographic factors of gender, age, and training frequency. A literature review of advertising and advertising in social media led to a model previously tested in another context being adopted for this study. This quantitative study utilized an online survey conducted in Sweden with 187 respondents. Analysis of the data revealed the ad exposure component of entertainment to have the largest positive impact on both attitudes toward the ad and brand. Furthermore, it was found that informativeness had a significant impact on attitudes toward the ad, while emotional appeal had a significant impact on attitudes toward the brand. From this, entertainment should not be neglected when designing Instagram sportswear ads, while the goal of the advertising could dictate whether it is more efficient to use informativeness or emotional appeals. Both attitudes toward the ad and brand lead to purchase intention, but attitudes toward the ad were found to have a stronger correlation with purchase intention of sportswear. Moreover, gender, age, and training frequency were found to impact the perceived emotional appeal of Instagram ads, leading to insights on how to better reach target audiences. This study contributes to the understanding of how sportswear marketers can increase purchase intention through advertising exposure, as well as contributing to the theoretical field of social media advertising.

T

ABLE OF CONTENTS1 INTRODUCTION ... 7

1.1 BACKGROUND ... 7

1.1.1 INSTAGRAM ... 8

1.1.2 SPORTSWEAR ... 9

1.2 PROBLEM AND PURPOSE ... 10

1.3 RESEARCH QUESTIONS ... 11

1.4 DELIMITATION ... 11

1.5 KEY TERMS ... 11

2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK AND HYPOTHESIS BUILDING ... 13

2.1 ADVERTISING ... 13

2.1.1 BASIC ADVERTISING MODELS ... 14

2.1.2 SOCIAL MEDIA ADVERTISING ... 17

2.2 SPORTSWEAR ... 18

2.2.1 INDUSTRY AND TRENDS ... 18

2.2.2 SPORTSWEAR AND CONSUMER IDENTITY ... 19

2.3 DEMOGRAPHICS ... 19 2.3.1 GENDER ... 20 2.3.2 AGE ... 21 2.3.3 TRAINING FREQUENCY ... 22 2.4 THEORETICAL MODEL ... 22 2.4.1 CREATIVITY ... 25 2.4.2 EMOTIONAL APPEAL ... 28 2.4.3 INFORMATIVENESS ... 30 2.4.4 ENTERTAINMENT ... 32

2.4.5 ATTITUDES AND PURCHASE INTENTION ... 34

2.5 SUMMARY OF HYPOTHESES AND THEORETICAL MODEL ... 37

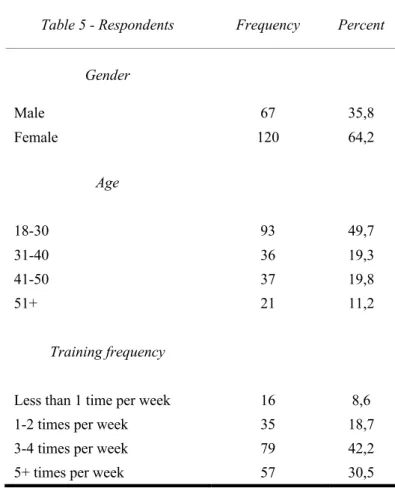

3 METHODOLOGY ... 38 3.1 RESEARCH APPROACH ... 38 3.2 RESEARCH DESIGN ... 39 3.3 RESEARCH METHOD ... 39 3.4 RESEARCH INSTRUMENT ... 40 3.5 SAMPLING ... 45 3.5.1 SAMPLING TECHNIQUE ... 45 3.6 SECONDARY DATA ... 46 3.7 QUALITY OF RESEARCH ... 48 3.7.1 VALIDITY ... 48 3.7.2 RELIABILITY ... 50 3.7.3 INDEPENDENT T-TESTS ... 50 3.7.4 REGRESSION ANALYSIS ... 51 3.8 ETHICAL CONSIDERATION ... 52 4 FINDINGS ... 54 4.1 RESPONDENTS ... 54 4.2 RELIABILITY ... 55 4.3 MULTICOLLINEARITY ... 56 4.4 T-TESTS ... 57 4.4.1 MALES/FEMALES ... 57 4.4.2 AGE ... 59 4.4.3 TRAINING FREQUENCY ... 60 4.5 FACTOR ANALYSIS ... 61 4.6 REGRESSION ANALYSIS ... 64 4.7 SUMMARY OF HYPOTHESES ... 68 5 ANALYSIS/DISCUSSION ... 69

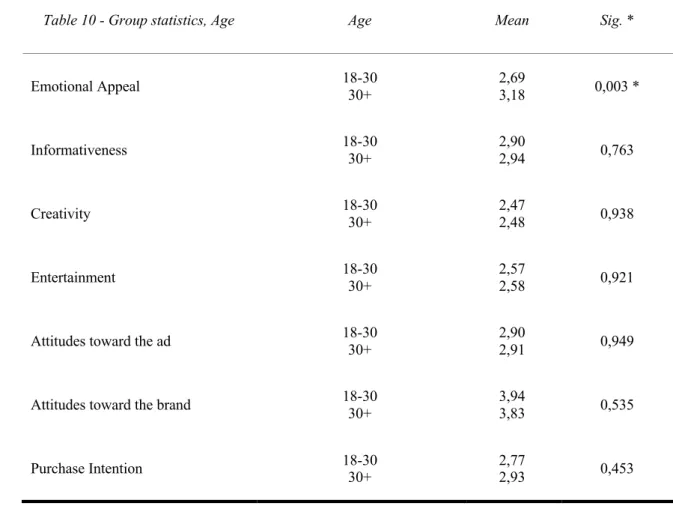

5.1 DIFFERENCES BETWEEN GROUPS ... 69 5.1.1 GENDER ... 69 5.1.2 AGE ... 70 5.1.3 TRAINING FREQUENCY ... 71 5.2 THE COMPONENTS OF AD EXPOSURE ... 72 5.2.1 INFORMATIVENESS ... 72 5.2.2 ENTERTAINMENT ... 72 5.2.3 EMOTIONAL APPEAL ... 73 5.2.4 CREATIVITY ... 73

5.3 ATTITUDES AND PURCHASE INTENTION ... 74

5.4 REVISED MODEL ... 74

6 CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS ... 76

6.1 CONCLUSION ... 76 6.2 THEORETICAL IMPLICATIONS ... 77 6.3 MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS ... 77 6.4 SOCIETAL IMPLICATIONS ... 78 6.5 LIMITATIONS ... 79 6.6 FUTURE RESEARCH ... 79 REFERENCES ... 81 APPENDIX ... 90 APPENDIX 1 ... 90 APPENDIX 2 ... 90 APPENDIX 3 ... 93 APPENDIX 4 ... 94 APPENDIX 5 ... 94 APPENDIX 6 ... 95 APPENDIX 7 ... 95

A

BBREVIATIONSThe following abbreviations are used throughout chapter 3 Method, 4 Findings, and 5 Analysis/Discussion as these variables are frequently occurring:

CRE - Creativity EA - Emotional appeal INF - Informativeness

AAD - Attitudes toward the ad ATB - Attitudes toward the brand PI - Purchase intention

1 I

NTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUNDThe world has seen a rise in technology affecting the way advertising is conducted, shifting focus from traditional to social media. With it, digital tools for targeting consumers have become useful for marketers, causing a greater allocation of marketing budgets toward social media (Liu, Li, Ji, North, & Yang, 2017). Simultaneously, the sportswear industry has experienced a rise in turnover and is projected to triple over a period of eight years (Business Insider, 2017). Digital tools can be utilized by sportswear marketers in their ambitions to further increase purchase intention. For example, by making use of advertising tools such as Facebook Ads Manager, taking advantage of data surrounding target groups could enable focused targeting of potential consumers. Sajid (2016) suggests that social media can be viewed as a way of targeting a particular group of people, rather than just a way of mass marketing. As consumers are exposed to advertisements, attitudes are influenced, which can lead to purchase intention, resulting in increased sales (Wardhani & Alif, 2019). However, this requires knowledge of which components of ad exposure to focus on to drive attitudes.

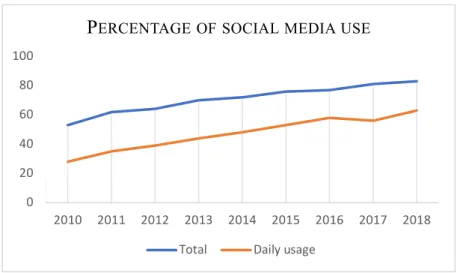

Another reason for organizations’ advertising presence on social media could be the increasing social media use (Figure 1). According to Internetstiftelsen (2019), the five largest social media platforms in Sweden are Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter, and LinkedIn. Considering the presence of social media, brands have several platforms to utilize when realizing their social media strategies.

Figure 1 - Social media use (Söderman, 2018).

0 20 40 60 80 100 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

PERCENTAGE OF SOCIAL MEDIA USE

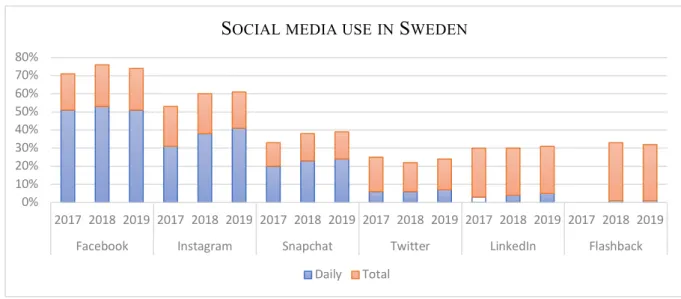

Facebook and Instagram have considerably higher numbers than the others when measuring usage in Sweden (Internetstiftelsen, 2019). People are frequent users of both platforms (Figure 2), but young people appear to be moving away from Facebook as their main choice of platform (Internetstiftelsen, 2019).

1.1.1 INSTAGRAM

Figure 2 reveals that Facebook usage is maturing as the growth appears to have stagnated, while Instagram is still on the rise for both total and daily usage. This rise in Instagram usage is occurring throughout all age-groups in Sweden (Söderman, 2018). Additionally, a study found the median engagement rate of Instagram to be 17,8 times higher than that of Facebook, making Instagram interesting for brands who want to engage with consumers (Jackson, 2019). Engagement can be an efficient tool for strengthening relationships with consumers, and thus, driving retention and loyalty (Sashi, 2012). The majority of Instagram users (65%) are between the ages of 18-34 years old according to an analysis by Clement (2019). Furthermore, according to Verma (2019), Instagram is transforming into a marketplace, which is especially useful for small and medium sized businesses with limited resources, enabling consumers to conduct purchases directly without leaving the platform. Being less of a cluttered platform, Instagram is emerging as a good marketplace for many types of brands (Verma, 2019). Moreover, it was reported by Gesenhues (2018) that ad spending on Instagram between 2017 to 2018 grew at over four times the rate of ad spending on Facebook during the same period (Instagram 177% vs. Facebook 40%). As increasingly more resources are spent on this growing platform, it is of interest to measure the effect of the components of Instagram advertisement exposure.

Ad exposure on Instagram has been found to influence consumers’ attitudes toward both brands and advertisements (Wardhani & Alif, 2019; Mukherjee & Banerjee, 2017). Furthermore, purchase intention has been shown by the same scholars to be driven by these attitudes.

Figure 2 - Instagram use (Internetstiftelsen, 2019).

1.1.2 SPORTSWEAR

In 2016 the sportswear market was valued to USD 78 billion worldwide, while the valuation is estimated to USD 231,7 billion by 2024, indicating a significant market growth in the coming years (Business Insider, 2017). As stated by Springbot (2018), the sports leisure trend is the primary driver of growth in the sportswear market, and consumer researchers have recognized dress codes becoming more casual as an antecedent for this. The strength of the individual drivers of attitudes could be shifting in line with evolving trends, resulting in implications for advertising strategies. What drove attitudes in the past may have changed when compared to today.

Previous research has found four different components of advertisement exposure to drive attitudes toward the ad (Ducoffe, 1995; Reinartz & Saffert, 2013; Taylor, Lewin, & Strutton, 2011). The four components are: emotional appeal, informativeness, entertainment, and

creativity.

From this, marketers’ needs for strategizing with a purpose when designing advertisements is salient. As increasing resources are spent on Instagram marketing and within the sportswear industry, it could be beneficial for marketers to know how to put these resources best to use in order to drive purchase intention.

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 2017 2018 2019 2017 2018 2019 2017 2018 2019 2017 2018 2019 2017 2018 2019 2017 2018 2019 Facebook Instagram Snapchat Twitter LinkedIn Flashback

SOCIAL MEDIA USE INSWEDEN

1.2 PROBLEM AND PURPOSE

This study will be investigating attitudes toward sportswear ads on Instagram and sportswear brands. The sportswear context resonates with the choice of Instagram as the platform of investigation, since Instagram has been dominating the engagement rate for sportswear brands on social media in the past years (Unmetric, 2016).

The problem for marketers working in the sportswear industry is not having direct indications as to which components of Instagram advertising exposure that drives attitudes toward sportswear ads and brands. Particularly as drivers may have changed together with the shifting sportwear trends. Measuring these components could yield further insights as to how marketers could adjust their strategies accordingly. The sportswear context could include advertising of both affective and cognitive aspects, rendering it suitable for covering components of both types. A sportswear advertisement could for example make use of informativeness (cognitive) in its explanations regarding functionality of a garment. On the other hand, marketers could also make use of appealing to the emotions (affective) of potential consumers (Belch, Belch, Kerr, & Powell, 2014). An example of this would be using storytelling conveying an underdog position thereby having consumers connect to the advertisement on an affective rather than cognitive level. Investigating the strength of each construct to ascertain their individual effect on consumer attitudes, when being exposed to advertisements, could help guide marketers toward executing targeted advertisements. It is also of interest to investigate whether there are differences in these components when looking at demographic variables such as gender, age, and training frequency in order to provide marketers with insights on how to tailor ads to their specific target group. Moreover, measuring the impact of attitudes toward the ad and attitudes toward the brand on purchase intention, will determine the importance of managing attitudes. Thus, the purpose of this study is to clarify what factors of ad exposure to emphasize when developing Instagram ads in driving attitudes and purchase intention of sportswear.

1.3 RESEARCH QUESTIONS

To obtain insights for marketers creating Instagram advertisements with the purpose of maximizing consumers’ purchase intention in the sportswear industry, the following research questions are presented:

“What factors of ad exposure have the greatest impact on attitudes toward the ads and brands?”

“Do positive ad and brand attitudes lead to purchase intention?”

“Do differences in perceived ad exposure components, attitudes, and purchase intention exist within groups of gender, age, and training frequency?”

1.4 DELIMITATION

The fact sportswear could be considered part of the fashion industry led the authors to put emphasis on the fact this study solely includes the fashion industry from the angle of sportswear. The study is thereby not treating the fashion industry per se.

1.5 KEY TERMS

Attitudes toward the ad – A predisposition to respond positively or negatively to a certain

advertising stimulus during an occasion of advertising exposure (Lutz, 1985).

Attitudes toward the brand – A consumer’s overall evaluation of a brand (Davtyan &

Cunningham, 2017).

Creativity – Suprising or unique ideas, leading to elaboration. Can include artistic elements

such as an original color palette (Reinartz & Saffert, 2013).

Emotional appeal – Appealing to emotions such as happiness, fear, joy, love, anxiety, in a

Entertainment – The ability of an advertisement to arouse aesthetic enjoyment (Oh & Xu,

2003).

Informativeness – The degree to which an advertisement conveys information perceived useful

by the consumer (Logan, Bright, & Gangadharbatla, 2012; Pavlou, Liang, & Xue, 2007).

Purchase intention - Consumers’ willingness to buy a given product at a specific time or in a

specific situation (Lu, Chang, & Chang, 2014).

Sportswear - Include tops and bottoms (i.e. excluding shoes and accessories such as socks and

2 T

HEORETICAL FRAMEWORK AND HYPOTHESIS BUILDINGThe following chapter includes the literature review conducted for this study. The topics of review are: advertising (basic models, ad clutter, and social media), sportswear (industry and trends, and links to consumer identity), demographic factors, and ad exposure components. The review leads up to the theoretical model used in this study (Figure 9) and the proposed hypotheses.

2.1 ADVERTISING

Advertising is defined as a one-way mass communication about a product or organization, impersonal in nature, and paid for by a marketer (Lamb, Hair, & McDaniel, 2017). Moriarty, Mitchell, and William Wells (2009) defines advertising as persuasive communication which is paid for and that is using mass and interactive media in order to reach broad audiences, with the intent of connecting an identified sponsor with buyers letting sponsors provide information about goods or services. The five basic factors of this definition are: it is paid for by the advertiser, a sponsor is identified, broad audience reach, the ad seeks to inform, persuade, and influence consumers, and messages are conveyed through many different kinds of media (Moriarty, Mitchell, & William Wells, 2009). This popular form of promotion can be utilized e.g. in web advertising where marketers are looking to aspire behavior among consumers on the internet (Wolin, Korgaonkar, & Lund, 2002). Deeply rooted attitudes and values are not the subject of change, rather the attitudes closer to the surface of a consumer’s mind can be affected, for example by turning a negative attitude towards a product into a positive one. Furthermore, it is argued already positive attitudes are enhanced by the use of humor in ads and that ads can reinforce already positive brand attitudes (Solomon, 2011). The use of ads could have an effect on consumers’ ranking of brand attributes such as the feeling of sportswear being of durable quality or very light to wear.

Advertising can be divided into two major types, the first being institutional advertising and the second product advertising. Institutional advertising is used where the aim is to influence the consumers’ perceptions of a brand or the industry as a whole, while product advertising is used when striving for increased sales of a product or service through informing consumers about beneficial features (Lamb et al., 2017). An example of institutional advertising is a sportswear brand running ads where the focus lies not with the products but with a societal issue like

covid-19 and the importance of thinking “we” instead of “me”. These two major types of advertising could also be referred to as the economic role (product advertising), and the social and cultural

role (institutional advertising) (Lane, King, & Reichert, 2011). Making use of institutional

advertising could result in consumers associating the brand with solidarity, a positively sounding attribute. An example of the alternative advertising type, product advertising, is promoting a t-shirt as having superior breathability compared to shirts within the same category. This could result in consumers viewing the product as having greater value and thereby rank the product higher than others. Early advertising models were developed in order to achieve a greater understanding of the communication effects achieved through advertising,

2.1.1 BASIC ADVERTISING MODELS

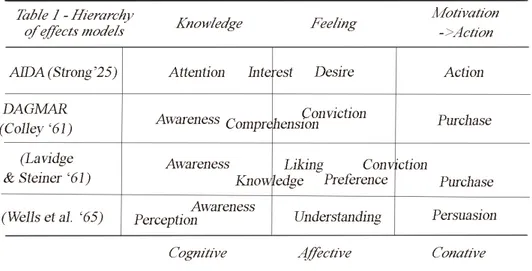

In order to measure the communication effect of an ad and to be used as a basis of marketing communication strategy, several hierarchy of effects models have been developed (Wijaya, 2015). It is suggested that the audiences respond to marketing communication in an ordered way; cognitively (thinking), affectively (feeling), and conatively (doing). The cognitive aspect can be reflected in knowledge, beliefs, or thoughts (Barry & Howard, 1990), while the affective aspect consists of feelings and emotions in connection to the brand (Egan, 2007). Conation is the intention to perform a behavior (i.e. purchase intention) or the actual behavior (Egan, 2007). Several reasons for the importance of understanding the hierarchy of effects have been provided by scholars. One is it could allow marketers to predict behavior (Preston & Thorson, 1983; Barry & Howard, 1990). Secondly, an understanding could provide insights on what advertising strategies to emphasize. Thirdly, the hierarchy of effects has proved valuable in planning, training, and for conceptual tasks in firms (Barry & Howard, 1990).

One of the early hierarchy of effects models is the AIDA model, generally attributed to Strong in 1925. The goal of this model was to serve as a framework guiding a prospect through the stages leading up to purchase. The ‘A’ stands for Attention, referring to the stage when the consumer first pay attention to the ad. ‘I’ stands Interest and represents the stage when the consumer becomes interested in the ad. ‘D’ stands for Desire, the stage when the consumer have a passion towards the product or brand. ‘A’ stands for Action and is the stage where the consumer act by, for example, buying the product or elect the brand in order to satisfy their desire (Wijaya, 2015).

Another early hierarchy of effects model is DAGMAR. According to Lamb et al. (2017) there are a number of approaches for setting relevant goals, DAGMAR (Defining Advertising Goals for Measured Advertising Results) being one of them. The model includes stages of influence in regard to advertising messages on consumer behavior. The stages are awareness,

comprehension, conviction, and purchase (Wijaya, 2015). The first stage, awareness, is where

consumers are becoming aware of the advertisement and its message. The second stage,

comprehension, is about the consumer interpreting an ad, reaching an understanding of it. The

third stage, conviction, relates to the consumers beliefs regarding the message conveyed being genuine. The fourth stage, purchase, is where consumers act on their beliefs from viewing the message and make a purchase (Wijaya, 2015). This approach calls for a complete list of objectives defining the target audience of the ad or campaign, and needs measurable goals (Lamb et al., 2017). In order to reach objectives, the creative decisions taken could enable penetration of the advertising clutter in an advertising channel, meaning targets might be more likely to notice the ad.

In table 1 a comparison between some of the hierarchy of effects models is found. However, the classical hierarchy of effects models have a number of shortcomings, as noted by Egan (2007). There has been no empirical support that consumers go through each stage. The models do not account for interaction between the stages. Lastly, Egan (2007) stated that post-purchase experience is often neglected. Furthermore, these models do not accommodate for the changes in the way consumers socialize, communicate, and are influenced by today’s technology such as social media. Specific models for the social media context will be discussed more in-depth in section 2.4 Theoretical model.

Table 1 - Hierarchy of effects models (Egan, 2007)

2.1.1.1 ADVERTISING CLUTTER

According to Ha and McCann (2008), advertising clutter is defined as the perceived presence of a large amount of editorial content in an editorial medium. When this amount of non-editorial content exceeds the consumers’ acceptance levels, it is referred to as clutter (Ha & Litman, 1997). Instagram is one form of editorial medium, consumed primarily for its editorial content, i.e. entertaining or educating content. Here the non-editorial content would consist of the ads being displayed in the Instagram feed.

Ha and McCann (2008) state that some of the issues that arise with a cluttered environment is both that consumers will be irritated and try to avoid ads, and also that they will not be able to remember the ads because of limited memory. However, Ha and McCann (2008) suggests that perceived ad clutter can be mediated by factors such as consumers’ attitudes toward the advertising, product relevance, and ad presentation (e.g. entertaining, informational). When an ad is seen as informational or entertaining, it can become desirable since it provides uses or gratification for the consumer (Ha & McCann, 2008).

Previous research have found differences in attitudes toward the advertising depending on the media. For example, attitudes towards print advertising were more positive than attitudes toward electronic media advertising (Grusell, 2007). Therefore, it could be especially important for electronic media advertisers to shape positive attitudes, as well as ensuring other influencing

factors such as product relevance and presentation have a positive impact for the consumer to not see the ad as clutter.

From this, social media could be perceived as a cluttered environment, strengthening the need of a deeper understanding of social media advertising for marketers to break through the clutter. 2.1.2 SOCIAL MEDIA ADVERTISING

A common reason for social media advertising or marketing is companies desire to build their brand through utilizing social media’s communication advantages (Tiago & Verissimo, 2014). The communication portion of social media enable companies to aspire word of mouth among people, this with the help of the very people sharing information with one another about brands or products (Kotler & Keller, 2016). Social media marketing is preferably used when marketers value measuring the reach of ads, and by using social media platforms instead of traditional media, such as television or radio, marketers are able to acquire similar local reach with the upside of gaining information about actual reach (Das & Lall, 2016). With social media having become ubiquitous, the practice of using social media to connect and build relationships has become a common undertaking (Tuten & Mintu Wimsatt, 2018). Scarpi (2010) argues that social media enables a direct link to individual consumers given its

communication possibilities (e.g. comment sections), and that this would be tough to establish using traditional. Such a link could be valuable for maintaining consumer relationships. Sashi (2012) adds to this by arguing that social media enable companies to co-create value together with consumers due to the interactive nature of social media. From this, building relationships and maintaining consumer attitudes through advertising on social media could render

consumer retention.

With an increasing amount of advertising on social media the interest of conducting research on the topic has increased, and researchers have been investigating specific marketing

objectives reaching suggestions on how to improve brand image or increase brand awareness (Felix, Rauschnabel, & Hinsch, 2017). In these areas’ consumer attitudes could play a

significant part. Several researchers have investigated consumer attitudes in regard to online ads, and social media advertising (Wardhani & Alif, 2019; Mukherjee & Banerjee, 2017; Boateng & Okoe, 2015). On Instagram sponsored advertising is commonly done through the use of two types of content; firm-generated content and paid content. Unless consumers

actively have chosen to follow specific brand profiles, they are solely exposed to advertising through paid content (Kumar, Bezawada, Rishika, Janakiraman, & Kannan, 2016). Two examples of successful sportswear brands on Instagram are Nike and Adidas, which are among the top ten most popular brands on Instagram (Jahns, 2019).

2.2 SPORTSWEAR

2.2.1 INDUSTRY AND TRENDS

According to Salfino (2017), a cursory look at the sportswear industry could lead to the perception of the industry having a bad time with retail store closings and reported lower earnings from major brands. She states two major reasons for this. An increase in newcomers in the market, such as Lululemon, and a growth in online sales means the market environment is changing. The sportswear industry is still doing well, especially due to the growing athleisure trend (Salfino, 2017).

Athleisure is a portmanteau of “athletic” and “leisure”, referring to casual clothing that can be worn for both sports and in general (Lipson, Stewart, & Griffiths, 2020). This trend was introduced to the fashion world with the form-fitting yoga pants (Holmes, 2015; Segran, 2015), and has evolved into one of the dominant trends of this century (Wilson, 2018). Originally, athleisure was primarily targeted to women but as it has increased in popularity it now includes men as well (Lipson et al., 2020). Moreover, as guidelines for work-appropriate clothing have changed in recent years, millennials and generation Z are more likely to gravitate toward this new trend than the older generations (Salfino, 2016).

Athleisure sales have grown exponentially (Kell, 2016) and were accounting for 24% of total apparel sales in the Unites States in 2018 (The NPD Group, 2018). This market is projected to continue growing, even if the general apparel market would stagnate or decrease (Cheng, 2018). Compared to the valuation of the sportswear industry of 78 billion USD (Business Insider, 2017), the global athleisure market was valued to over 44 billion USD (Roberts, 2017), indicating it is a significant part of the sportswear industry.

The term sportswear has in this study been defined by looking at the three largest sportswear brands globally: Nike, Adidas, and Under Armour (Bhasin, 2019). These brands are

categorizing sportswear separately from shoes and accessories (socks, underwear, and protective gear). Therefore, the same categorization will be utilized to define sportswear in this study.

2.2.2 SPORTSWEAR AND CONSUMER IDENTITY

Clothes can both communicate symbolic meaning (Kaiser, 1997) and be understood as an extension of one’s self (Wilson, 2003). Scholars have argued that clothes mark a boundary between our biological bodies and the social world (Wilson, 2003). One major driver of the athleisure trend is proposed to be an increasing cultural desire of appearing “fit” and “healthy” (Green, 2017; Salpini, 2018). Therefore, consumers buying athleisure may be doing so to identify with the “wellness” trend and communicate participation in this lifestyle.

However, Conner, Peters, and Nagasawa (1975) suggests that physical appearance has a greater impact on athletic impressions than clothes do, and thus the body could significantly impact how the conveyed message is interpreted. As people may wear sportswear to try to achieve a body ideal that is difficult or impossible to reach, there will be an indefinite desire to continue to strive for manipulating the bodily appearance through clothes (Boultwood & Jerrard, 2000). This could be one explanation of the exponential growth of the sportswear market.

Another aspect of wearing clothes is the possibility of triggering associated concepts and meanings, as people embody the symbolic meaning of the clothes (Adam & Galinsky, 2012). For example, Adam and Galinsky (2012) found that, in a lab setting, people wearing a lab coat were able to focus better than those not wearing a lab coat. Similar results have been discovered in a sportswear context as well. Lipson et al. (2020) found that athleisure influenced the wearers feelings, thoughts, and behavior. For example, it resulted in the wearer being encouraged in fitness-based activities, feeling more confident and athletic, and therefore, were more likely to move their bodies.

2.3 DEMOGRAPHICS

Examples of demographics are gender, age, income, education, nationality, plus a variety of additional factors (Armstrong & Kotler, 2005). Demographics are useful when differentiating

between consumers, and this type of segmentation can help marketers develop strategies by providing purchasing-patterns (Barrie & Furnham, 1992). By utilizing analytical tools for segmentation, the aim is to increase the likelihood of consumers responding positively to a promotion (Dibb & Simkin, 1996). The following section will dig deeper into differences between consumers, and its effects on ad response in regard to three demographic variables: gender, age, and training frequency. The first two were chosen as the authors believe them to be commonly used by organizations for segmenting consumers. All three demographic variables could be large enough segments to yield profitable results if properly addressed. Additionally, training frequency served as a reasonable choice of psychographic variable given the study’s direction towards ad exposure of sportswear.

2.3.1 GENDER

Differences between genders have been investigated throughout a number of fields, in this study the focus lies on ad exposure responses, meaning the processing of information provided by ads, ultimately influencing purchase intentions. Scholars argue differences between the genders regarding this matter more often than not relates to the environment in which males and females find themselves in, for example the social roles or pressures associated with the respective gender (Burstein, Bank, & Jarvik, 1980; Meyers-Levy & Stermthal, 1991). However, contrasting brain functions between males and females provides further explanations as to how differences exists (Meyers-Levy, 1994). Being male or female has been proven to mean differences in information processing, where male and female responses to objective and subjective ad arguments differ, a topic which could be deemed the most important for marketers to fathom (Darley & Smith, 1995). Females are considered comprehensive information processors and males are considered selective processors, this means females are responding to complete sets of cues whereas males are not (Meyers-Levy, 1989; Meyers-Levy & Stermthal, 1991). For marketers active in sportswear advertising, insights relating to Darley and Smith’s (1995) arguments could be considered valuable seeing as sportswear often is gender specific. In a study investigating how the involvement with a clothing product influences consumer perceptions of a product Kim, Damhorst, and Lee (2002) found gender differences to exist within two variables, namely comfort and fashion. The variable of comfort was proven, for males, a greater component of clothing involvement, meaning the resulting positive influence on product perception may have been greater for males than females as well (Kim et al., 2002). The results were reversed with females having greater clothing involvement in regard to the

variable of fashion (Kim et al., 2002), indicating fashion yielded a more positive influence on product perception for females than males. Investigating differences between males and females in respect to sportswear ad responses could yield additional insights of the gender differences within the context.

2.3.2 AGE

Previous research investigating age-related differences in the response of consumers viewing ads argue consumers of an older age responds in an alternate fashion compared to those of a younger age. Examples are age-related differences regarding susceptibility to ads that are deceiving, age-related differences in the effects of ad repetition on perceived truthfulness (Gaeth & Heath, 1987; Law, Hawkins, & Craik, 1998; Skurnik, Yoon, Park, & Schwarz, 2005), and to which extent strategic processing of information is detailed-based or schema-based depending on age (Yoon, 1997). However, as the famous phrase reads: “Age is just a number”, Wray and Hodges (2008) investigated whether or not there existed a difference in consumer response to ads within the concept of age itself. According to Wray and Hodges (2008), cognitive age is an individual’s own perceived age comprised of feel-age, look-age, do-age, and interests. Cognitive- versus chronological age was investigated, and a consumer’s perception of their cognitive age was found to influence their response when marketers designed ads bearing it in mind (Wray & Hodges, 2008). Therefore, not only chronological age is of interest, but also the cognitive age of consumers when designing ads.

Research suggests that people adopt a more active role of managing and processing emotions as they are aging (Carstensen, 1992). In line with this, Isaacowitz, Turk-Charles, and Carstensen (2000) argue older people are adopting a more subjective and evaluative (i.e. emotional) processing mode, while younger people tend to engage in processing of a more objective and factual nature. Investigations have been conducted regarding the memory of older consumers, finding emotionally appealing ads to be remembered to a greater extent than when alternate appeals were used (Williams & Drolet, 2005). Whether or not age is considered cognitive or chronological, testing could yield insights as to how age groups differ in their response to sportswear ads.

2.3.3 TRAINING FREQUENCY

The two previously discussed variables are part of what can be called the traditional demographic base, helping marketers to access certain consumer segments. However, in order to increase the understanding of the consumers, additional variables can be utilized (Barrie & Furnham, 1992). The psychographic type of segmentation works by dividing consumers into groups based on factors such as lifestyle, interests or attitudes (Pickton & Broderick, 2005). The lifestyle concept has, according to Vyncke (2002), been used frequently within marketing due to consumer processing, as well as patterns of consumption, being influenced by the lifestyle of consumers. Using psychographic variables could prove useful for differentiating between consumers when recognizing behavioral differences. Within the context of sportswear such a variable could be training frequency. A difference in training frequency could indicate a positive attitude towards training in general. Logically it could be assumed a higher need, and therefore purchase intention of sportswear, exists among consumers that are working out to a greater extent. However, this has to be tested in order to make such a statement.

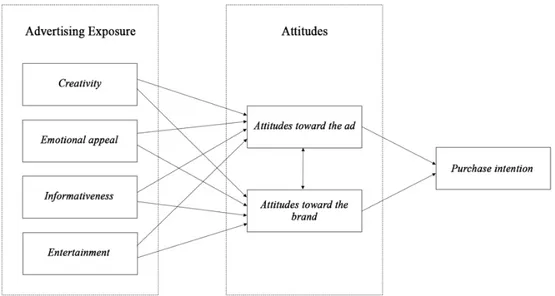

2.4 THEORETICAL MODEL

Several studies have been performed on advertising and attitudes on social media (Boateng & Okoe, 2015; Kim & Ko, 2012; Wardhani & Alif, 2019; Mukerjee & Banerjee, 2017). Through exposure, attention, and perception, marketers can develop consumers’ opinions as well as create values (Kim & Ko, 2012), which could be argued to resemble attitudes. In order to examine moderating effects of corporate reputation and consumers’ attitude toward social media advertising on consumers’ behavioral response, Boateng and Okoe (2015) performed a hierarchical multiple regression on three variables. In their study, Boateng and Okoe (2015) made use of a survey made up of items loading on three different constructs: consumer

response, corporate reputation, and attitudes toward social media advertising. The study found

that corporate reputation and attitude towards social media advertising individually influenced positive consumer response, where attitudes towards social media advertising accounted for the highest influence; a 50% increase in favorable response to social media advertising. The study by Boateng and Okoe (2015) did not investigate how attitudes toward advertisements and brands come about but found that attitudes play a significant role in consumer response. Advertising exposure can elicit both cognitive (Belch & Belch, 2015) and affective (MacKenzie, Lutz, & Belch, 1986) responses among individuals, leading to both attitudes

toward the ad and attitudes toward the brand (Wardhani & Alif, 2019). It was suggested by Ryan and Bonfield (1975) that attitudes toward the ad and attitudes toward the brand leads to purchase intention. Later support has been found for this in the contexts of traditional media (MacKenzie et al., 1986) and social media (Wardhani & Alif, 2019).

A study by Lee and Hong (2016) found informativeness and ad creativity to be key drivers of behavioral response to social media ads. Furthermore, they found that perceived herd behavior (perceived tendency of an individual to mimic the actions of a larger group) had an indirect impact on purchase intention through the mediators of intention to express empathy (i.e. liking an ad on Instagram) and subjective norm. However, perceived herd behavior will not be treated in this study as it is not part of the ad exposure per se, and not within the control of the marketer to the same extent as for example ad exposure components.

Wardhani and Alif (2019), and Mukherjee and Banerjee (2017) digs deeper into the ad exposure antecedents of attitudes, meaning insights are possible to draw regarding what marketers could focus on for influencing positive attitudes towards their ads. Although similar, Mukerjee and Banerjee’s (2017) model, and Wardhani and Alif’s (2019) model includes differences. The first investigated three antecedents; entertainment, information, and credibility, whereas the second investigated four; emotional appeal, informativeness, creativity, and entertainment. Additionally, Mukerjee and Banerjee’s (2017) model portrayed these antecedents as ultimately leading to both word of mouth- and purchase intention, while the one presented by Wardhani and Alif (2019) solely led to purchase intention. Even though word of mouth intention could serve as a positive outcome of an ad, the model does not include it as a driver of purchase intention, which this study intends to measure.

Choi and Rifon (2002) found three antecedents of ad credibility: website credibility, advertiser

credibility, and relevance. However, website credibility and advertiser credibility are not per

se part of the ad exposure components that the marketer have direct control over in designing a social media ad. Relevance was found to increase ad attention (Jung, 2017), which could be useful in breaking through the clutter. Although, Jung (2017) found that in the social media context this effect is mediated by resulting privacy concerns, leading to increased ad avoidance. From this, ad credibility will not be included in the model of this study.

Early research on ad exposure have found four constructs influencing attitudes toward ads:

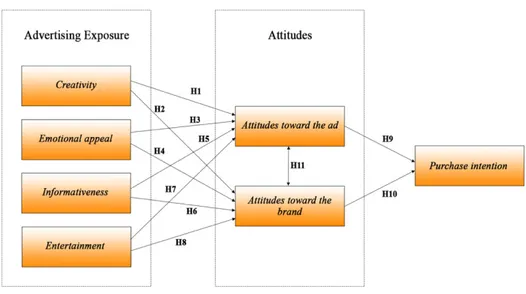

Saffert, 2013; Taylor et al., 2011). Wardhani and Alif’s (2019) model builds on this previous research and the model fits well with the purpose of this study. It is similar to the early hierarchy of effects models, including cognitive, affective, and conative aspects, but more specifically developed to be applied in a social media context. Additionally, the reliability measures performed by Wardhani and Alif (2019) resulted in high reliability scores of the scales used. The model will therefore be used in this study to conceptualize and measure the impact of Instagram ad exposure on attitudes, and subsequently, purchase intention. Although the original model was intended for use in a general context of Instagram advertising, this study will be using it in the context of sportswear advertising on Instagram. The model is conceptualized in Figure 3, followed by an in-depth literature review of all constructs.

2.4.1 CREATIVITY

Up until the 2000s there have been no systematic research defining advertising creativity and investigating its relationship with advertising effectiveness (Smith & Yang, 2004; Reinartz & Saffert, 2013). However, creativity has been a subject for investigation among psychology scholars for a considerably longer time. Early research by Guilford (1950), interested in the relationship between creativity and intelligence, produced a model defining creativity as an important component of the human intellect - divergent thinking. Subsequently, two stages of creativity were identified by Maslow (1970; 1971), the primary stage which related to divergence, in line with Guilford, and the secondary stage, related to relevance. Mumford and Gustafsson (1988) found support for this in their review of definitions of creativity in psychology, as they concluded creativity could be defined as ‘the production of novel, socially

valued products’ (p. 28). This could for example be a novel solution to a social problem.

Although it is important to note that the previous definition refers to psychology and not marketing.

In marketing and advertising literature creativity has been conceptualized in a variety of forms. Factors mentioned include for example: novelty (Amabile, 1983), originality (Thorson & Zhao, 1997) and imaginativeness (Duke & Sutherland, 2001), which can be argued to resemble divergence as mentioned in the psychology literature. Moreover, relevance factors are mentioned as; appropriate, useful, meaningful and valuable (Amabile, 1983; Haberland & Dacin, 1992; Thorson & Zhao, 1997). A third major stage, effectiveness, was found in some definitions in a review by Smith and Yang (2004). However, Smith and Yang (2004) argue using effectiveness as an explanatory variable for creativity is illogical, since one of the main reasons for investigating creativity is to explain advertising effectiveness as a consequence of creativity. Hence, it is argued effectiveness per se should not be part of the definition of advertising creativity.

As only a handful of studies had been investigating certain aspects of advertising creativity, and fewer modeling the overall phenomenon Smith, MacKenzie, Yang, Buchholz, and Darley (2007) performed a study in order to explain the components of advertising creativity. To achieve parsimony and reduce conceptual redundancy Smith et al. (2007) limited their model to only include the five components of divergence with the strongest correlations to advertising creativity; originality, synthesis, artistic value, flexibility, and elaboration (Smith et al., 2007).

This means their original nine components were reduced to these five to simplify the model, as the remaining four accounted for a smaller portion of the variance in advertising creativity. Furthermore, relevance was found to play an interacting role with divergence in predicting creativity, but a lacking effect for relevance on its own (Smith et al., 2007; Lehnert, Till, & Ospina, 2014). Therefore, it could be suggested relevance is playing an enabling role in determining the effect of divergence on advertising creativity.

Since relevance is a secondary factor (Maslow, 1970) and is not by itself directly correlating with advertising creativity (Smith & Yang, 2004), coupled with the fact that it has been previously researched extensively under the term ‘involvement’ (Smith & Yang, 2004), theoretical focus will lay on the five components of divergence.

The components of divergence in the advertising context were described by Reinartz and Saffert (2013) as:

ORIGINALITY

The advertisement make use of surprising or rare elements, focusing on unique ideas or features of the advertisement. It can also diverge from norms through visual or verbal aspects.

SYNTHESIS

Through synthesis an advertisement blends or connects objects that are normally seen as unrelated.

ARTISTIC VALUE

Advertisements with high artistic value can almost be seen as a piece of art by consumers rather than a pure sales pitch. This is achieved through high production quality with appealing visual or sound elements, making ideas come to life. For example, using an original color palette or memorable music.

FLEXIBILITY

This dimension means smoothly linking for example a product to a range of various uses or ideas.

ELABORATION

High elaboration is achieved by advertisements containing unexpected details or extending basic ideas, making them more intricate and complicated.

Reinartz and Saffert (2013) revealed elaboration to be having the largest impact by far, followed by artistic value, originality, flexibility, and synthesis. Another finding of Reinartz and Saffert (2013) was that certain combinations yielded superior results. Combining

elaboration and originality, or artistic value and originality resulted in nearly twice the

creativity relative to their indexed average.

However, even though increased focus on creative advertisements in most cases will drive effectiveness, this is not always the case. Reinartz and Saffert (2013) found it to vary significantly across product categories, suggesting for functional products (i.e. body care, cleaning detergents), satisfying clear consumer goals, less unorthodox approaches were preferred. Thus, it is important to understand the sensitivity of individual categories in respect to creativity before investing in expensive campaigns. It is therefore necessary to determine whether the sportswear category is suitable for advertising creativity, as this category could include both utilitarian as well as hedonic values for the consumers.

In a study measuring the effect of creativity on advertising effectiveness, Reinartz and Saffert (2013) found that money invested in highly creative advertising campaigns yielded nearly twice the amount of sales compared to money spent on non-creative campaigns. Moreover, support for the importance of creativity was fortified by Till and Baack (2005) arguing creative advertisements are easier to recall. In addition to this, Ang, Lee, and Leong (2007) saw an increase in the attitude toward both the advertisement and the brand with highly creative ads. Hence, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1: Creativity (CRE) in an ad positively impacts attitudes toward the ad (AAD) H2: Creativity (CRE) in an ad positively impacts attitudes toward the brand (ATB)

Figure 4 - H1, H2

2.4.2 EMOTIONAL APPEAL

Emotional appeal has been of interest for a long time, although with alternate terminology. Prior to the term emotional appeal being used Allport (1935) spoke of affective components. According to Allport (1935), affective components are consisting of an individual’s internal feelings when exposed to advertisements. Advertising using emotional appeals are aimed to arouse emotion in an attempt to stimulate purchase intentions (Kotler, 1997; Albers-Miller & Stafford, 1999). The intentions of using emotional appeals are to convey connections that are part of the individual consumer’s experience with the product of focus (Rossiter & Percy, 1997). It has been recognized by researchers that the consumers’ advertising judgements are impacted by emotions, and by including emotions within their advertising marketers are aiming to increase effectiveness through the consumers’ emotional reactions to the ad (Batra & Ray, 1986; Cotte & Ritchie, 2005).

Kotler (2003) describes emotional appeal as consisting of several types (e.g. fear appeal, social appeal, music appeal, sex appeal) in a variety of combinations. Emotional appeals do not solely consist of “happy” feelings, although appeals of this type are what profit-oriented brands are using the most (Roozen, 2013). Brands deem strategies involving evoking emotions of the opposite nature, such as fear or anxiety, too risky (Roozen, 2013). By linking emotions to products or services through the use of symbols or images, marketers are able to influence consumers’ emotions associated with the product or service (Hadjimarcou, 2012). However, Ruiz and Sicilia (2004) argue for caution when utilizing emotional appeals. Depending on the

individual consumer processing preference (i.e. whether it is skewed towards a cognitive or affective nature), an advertisement may be interpreted or processed differently by various consumers (Ruiz and Sicilia, 2004). Thus, it can provide reason for marketers to consider consumers’ processing, something that might lead to a higher desired effect on attitudes toward an ad or brand. With an attitude built on emotions, Dubé and Cantin (2000) argue, consumers are more likely to respond to promotions with persuading intentions. This regardless of appeals being emotional or informational.

Emotional appeals are sometimes compared to that of informational (Kotler & Keller, 2009). In their study Teichert, Hardeck, Liu, & Trivedi (2018) investigated the effects of both informational and emotional appeals on five key variables; purchase intention, information

search intention, positive attitude change, closer advertisement-examination intention, and integration into the evoked set. Teichert et al. (2018) found that emotional appeals showed

greater capacity for influencing all variables except integration into the evoked set, indicating marketers are not to disregard the possible use for emotional appeals.

According to Kotler and Keller (2009) the type of appeal used by marketers depend on variables such as who the target audience is, objectives, and what the product is. Additionally, it is argued the effectiveness of emotional appeals depend on the particular marketing situation of the advertisement being evaluated (Johar & Sirgy, 1991), such as within the specific context of this study. From this, two hypotheses are formed measuring the construct of emotional appeal and its correlation with attitudes toward the advertisement and attitudes toward the brand: H3: Emotional appeal (EA) in an ad positively impacts attitudes toward the ad (AAD)

Figure 5 - H3, H4

2.4.3 INFORMATIVENESS

The informational role of advertising was pioneered by Nelson (1974), suggesting the idea that an advertisement could be informative. Informational advertising was defined by Albers-Miller and Stafford (1999) as logical arguments, communicating explicit and objective product features, with the intention to solicit rational decision making through a focus on cognitive consumer responses. These arguments, containing facts and information, convey why a consumer should buy a product (Hadjimarcou, 2012). Previously, Rotzoll, Haefner, and Sandage (1990) defined informativeness as an advertisement’s ability to inform consumers about products, to enable them to make choices yielding the highest value. Earlier research supports this, as Resnik and Bruce (1977) found informative advertisements in fact enable consumers to make more intelligent buying decisions. Under the assumption that an informative advertisement is not deceptive, this could mean utilizing informativeness leads to positive societal effects if resulting in better purchasing decisions. Therefore, it could be important informative advertisements are accurate. The argument of using accurate information is further strengthened by scholars, as it was found consumers value advertisements if they give accurate portrayals of products (Andrews, 1989; Taylor et al., 2011). Consumers also consider information a major benefit of advertising exposure (Bauer & Greyser, 1968; Bartos & Dunn, 1974).

An aspect to bear in mind when publishing informative ads is the wear-out effect, as information will be learned and consumers are valuing the ads less with every exposure (Craig, Sternthal, & Leavitt, 1976; Ducoffe & Curlo, 2000). Too repetitive communication can lead to inattention

and, ultimately, negative thoughts (Cook, 1969; Calder, Insko, & Yandell, 1974; Wright, 1975). Therefore, it could be more efficient to shift advertisement spending from frequency of exposure, to increasing reach.

According to Lee and Hong (2016), informativeness is a perceptual construct, encompassing rational appeal, since it can help consumers in making informed judgments in acceptance of the communicated message. Thus, informativeness could be described as the degree to which an advertisement conveys information that the consumer perceives as useful (Logan et al., 2012; Pavlou et al., 2007). Moreover, Kotler and Armstrong (1994) defined a rational appeal to include emphasizing value performance, product quality, and economy. When compared to emotional appeal, in a study by Vaughn (1980), rational appeal was found to be superior when used in high-involvement, thinking situations. Furthermore, when factual information is to be communicated, Aaker and Norris (1982) found that informational appeals led to advertisements being more likely to be perceived as information.

Although an informational appeal could be more efficient in certain situations, there seems to be no consensus of an overall superior appeal. As previously mentioned, Kotler and Keller (2009) found the type of appeal utilized often depended on target audience, advertising objective, and product. Another example is Johar and Sirgy (1991), who found the marketing situation to dictate the effectiveness of the appeal.

There have been contradictory findings in the literature as well. For example, Stafford and Day (1995) found informational appeals to be more effective in a service context, while Matilla (1999) suggested the contrary, namely that emotional appeals are more effective for service marketing. Hence, a range of factors may be in play determining effectiveness, increasing the need for measuring the effectiveness of informativeness in the specific context of sportswear ads on Instagram.

Studies have found informativeness to be a driver of consumer attitudes in a range of different contexts. For example, it was found to influence attitudes toward television advertising and traditional media (Resnik & Bruce, 1977; Ducoffe, 1995; 1996), as well as attitudes toward e-commerce websites (Gao & Koufaris, 2006). It was also found important in the formation of consumer attitudes toward social media advertising by Taylor et al. (2011). Therefore, the following hypotheses are presented:

H6: Informativeness (INF) in an ad positively impacts attitudes toward the brand (ATB)

Figure 6 - H5, H6

2.4.4 ENTERTAINMENT

The Oxford Dictionary describe entertainment as amusement and or enjoyment. According to Oh and Xu (2003), entertainment is the ability to arouse aesthetic enjoyment. Effectiveness of advertisements has been said to depend on content and form (i.e. informativeness and entertainment) by Aaker, Mayers, and Batra (1992). Ducoffe (1995) recognized ads need to be examined from additional perspectives apart from business goals. In order for the topic to be researched in its full capacity one must also consider the value derived by consumers being exposed to advertisements and not solely the value derived by businesses (Ducoffe, 1995). Rodgers and Thorson (2000) claim in order for researchers to understand how internet users are responding to advertising, they must take motivations regarding why people are using the internet into consideration, an area in which the construct entertainment has been widely used. According to Hoffman and Novak (1996), factors of pleasure and involvement, in harmonious interaction with computer-based media, will lead to subjective perceptions in favor of a positive consumer mood. Entertainment being one motivational factor as to why people are viewing media has been a subject present among the works of scholars far earlier than the internet emerging.

Early claims were made surrounding people viewing media with the intent of escape (Katz & Foulkes, 1962). The reasoning behind such claims is people seeking gratification elsewhere but their reality, meaning entertainment could be a factor at play when the selection of media takes place. Thus, marketers could be able to take advantage of this behavior when creating ads by adhering to such needs. However, according to Katz and Foulkes (1962), it is necessary to note that not all involvement patterns in regard to media (e.g. tv, movies, newspapers) are to be deemed solely coming about due to the individual attempting to escape. Nonetheless, this reasoning could enable for insights regarding consumer behavior. Moreover, gratifications theory postulates people are selectively exposing themselves to their media of choice in order to meet gratification-needs (Taylor et al., 2011).

Taylor et al. (2011) argue ads on social media have potential to influence the consumers attitude towards the ad if the entertainment value of the ad is high enough. Aaker et al. (1992), and Ducoffe (1996) suggests entertainment as being vital for the effectiveness of advertising. Ducoffe (1996) argue this to be true for what he calls web advertising, a category in which advertising on Instagram fits. Wardhani and Alif (2019) argue that making sure to include entertainment within ads will attract consumers. Furthermore, a study conducted by Tsang et al. (2004) measuring constructs driving attitudes toward mobile advertising (e.g SMS advertising) found that entertainment contributed the most to positive attitudes. By creating advertisements that are highly entertaining, Ducoffe (1996) argue marketers will optimize ad value, and thus, achieve increased effectiveness. Tsang et al. (2004) argues entertainment have a significant effect and is to be considered imperative when measuring attitudes within the context of mobile advertising.

From the review on entertainment, the decision to include entertainment as a construct when measuring the correlation between the same and attitudes toward ads as well as attitudes toward brands fits. Therefore, two hypotheses of entertainment impacting attitudes are formed: H7: Entertainment (ENT) in an ad positively impacts attitudes toward the ad (AAD) H8: Entertainment (ENT) in an ad positively impacts attitudes toward the brand (ATB)

Figure 7 - H7, H8

2.4.5 ATTITUDES AND PURCHASE INTENTION

Attitude toward the advertising was defined by Lutz (1985) as a predisposition to respond positively or negatively to a certain advertising stimulus during an occasion of advertising exposure. The idea of consumers displaying affective reactions to advertising stimuli is far from a new concept (MacKenzie et al., 1986). In a literature review by Silk and Vavra (1974), research was found from the late 1920’s of ads as a causal factor evoking pleasant or unpleasant feelings among consumers.

Being a mediator of advertising response, the attitude towards the ad is described as both a cognitive and affective construct (Ducoffe, 1995). Muehling and McCann (1993) explained its cognitive dimensions as more centrally processed and deliberately evaluated, while the affective dimensions consist of low involvement, peripheral processing. However, MacKenzie and Lutz (1989) argued that attitude towards the ad does not distinguish between affect and cognition, nor is it a dual-component construct. They claimed this distinction is instead to be made among the antecedents to a general attitudinal response (Appendix 1). Therefore, attitudes toward the ad will be treated as a construct of a general attitude towards the ad, making no distinction between affect and cognition in this particular construct.

According to MacKenzie et al. (1986), the brand-related cognitions of ad exposure is a causal antecedent of brand attitudes. The concept of attitudes toward the brand is defined by Davtyan

and Cunningham (2017) as the overall evaluation of the brand by the consumer. Furthermore, Percy and Rossiter (1992) says the evaluation must be related to currently relevant motivation of the consumer. Thus, if the consumer’s motivation change, so might the evaluation of the brand. Furthermore, attitudes toward the brand consists of both a cognitive dimension guiding behavior, and an affective dimension energizing the behavior (Percy & Rossiter 1992). The more a consumer is exposed to a brand, the more likely it is their attitudes will be affected (Kotler & Keller, 2016).

According to the theory of reasoned action, a person’s attitude toward a particular behavior will influence the person’s intentions, indicating their behavior (Ajzen & Fishbein 1980; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). Moreover, evidence was found, using an “extended” Fishbein model, that attitudes toward the ad and attitudes toward the brand directly influences purchase intention (Ryan & Bonfield, 1975). This has been further confirmed in later research as well, in both traditional media (Mackenzie et al., 1986) and social media (Wardhani & Alif, 2019). Hence, the following hypotheses are formed:

H9: Attitudes toward the ad (AAD) positively impacts purchase intention (PI) H10: Attitudes toward the brand (ATB) positively impacts purchase intention (PI)

MacKenzie et al., (1986) suggested a correlation between attitudes toward the ad and attitudes toward the brand. Although, the direction of causal flows could depend on the specific situation. When a consumer is introduced to a novel product and brand, the flow is expected to be stronger from attitudes toward the ad to attitudes toward the brand. In a situation where the consumer is already familiar with the brand, the causal flow is expected to be stronger in the opposite direction (Edell & Burke, 1984; Messmer, 1979). Wardhani and Alif (2019) did only infer a causal flow from attitudes toward the brand to attitudes toward the ad but supplied no underlying reasoning for doing so. Thus, based on the reasoning above, the model in this study is slightly altered from the original, using a double-headed arrow for H11 instead. From this, a hypothesis is formed:

H11: Attitudes toward the ad (AAD) are positively correlated with attitudes toward the brand

2.5 SUMMARY OF HYPOTHESES AND THEORETICAL MODEL

H1: Creativity (CRE) in an ad positively impacts attitudes toward the ad (AAD) H2: Creativity (CRE) in an ad positively impacts attitudes toward the brand (ATB) H3: Emotional appeal (EA) in an ad positively impacts attitudes toward the ad (AAD) H4: Emotional appeal (EA) in an ad positively impacts attitudes toward the brand (ATB) H5: Informativeness (INF) in an ad positively impacts attitudes toward the ad (AAD) H6: Informativeness (INF) in an ad positively impacts attitudes toward the brand (ATB) H7: Entertainment (ENT) in an ad positively impacts attitudes toward the ad (AAD) H8: Entertainment (ENT) in an ad positively impacts attitudes toward the brand (ATB) H9: Attitudes toward the ad (AAD) positively impacts purchase intention (PI)

H10: Attitudes toward the brand (ATB) positively impacts purchase intention (PI)

H11: Attitudes toward the ad (AAD) are positively correlated with attitudes toward the brand

(ATB)

3 M

ETHODOLOGYThe following chapter explains the structure of the research, the aim of which was to yield results appropriate for upholding the purpose of the study.

3.1 RESEARCH APPROACH

The purpose of the study and the associated research questions allows for answers measurable in nature. The following section explains the approach the authors have taken, and why, towards reaching conclusions surrounding the measurable relationships between the constructs in the model presented in Figure 9. The authors have performed the study with the philosophical approach of positivism. Caldwell (1980) says the philosophical approach of positivism, with its substantial focus towards analytics and synthetics, came about as early as the 19th century. This focus, according to Caldwell (1980), meant researchers were only to consider meaningful statements (i.e. statements that are evidence-based as well as testable). Giddens (2007) further explains that statements have to uphold the criteria of being meaningful, while statements not adhering to this criterion are said to be of a metaphysical nature, they exist only in the human mind. This means they are not possible to physically prove. For a positivist researcher statements not meaningful are pointless (Giddens, 2007). As the authors of this study are interested in objective measures surrounding the relationships of constructs and not subjective ideas, they are positivists in their approach, and in line with how the positivist approach have been explained by scholars. By being objective the authors are able to analyze findings and draw conclusions based on evidence, which could prove as valuable information for marketers advertising sportswear on Instagram.

Deductive studies originate from theory leading up to the building of hypotheses, guiding the researchers towards conclusions regarding what is being investigated Gales (2003). This means deduction is fitting for conductive research from a positivist mindset. Deduction is defined by the Cambridge dictionary as ‘the process of reaching a decision or answer by thinking about

the known facts’, further adding to the appropriateness of a deductive study following the

mindset of a positivist researcher. Trusting observations to be aiding in gaining insights, and grasping the situation through deduction, is a clear use of positivism (Ryan, 2006). This kind of trust was adopted in this study. This view is shared by Kaboub (2008), who explains positivism as a philosophy in which events occurring in real life are explained through the use of empirical observations, followed by analysis. In this study, the authors made use of a