China and Climate

Cooperation –

Prospects for the

Future

China and Climate Co-operation

Prospects for the Future

A 2004 country study for the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency

2005

Joakim Nordqvist

Environmental and Energy Systems Studies Lund University

This report, originally published in Swedish, has been translated into English on behalf of the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency.

Table of Contents

Abbreviations and Acronyms... v

Summary ...vii

1 Population and Government... 1

2 Economic Profile... 1

3 Energy Profile ... 2

4 Climate Indicators ... 7

4.1 Carbon dioxide profile ... 7

4.2 Other greenhouse gases than carbon dioxide ... 10

4.3 Chinese climate policy in brief... 10

5 The Climate Arena in China... 11

5.1 Institutional structure for processing climate issues ... 11

5.2 Competence centres for climate policy and climate science... 12

5.3 Trade and industry and the climate issue ... 13

5.4 Civil society... 14

5.4.1 The media and educational institutions... 15

5.4.2 Non-governmental organisations ... 15

5.5 Bilateral and multilateral co-operation... 16

6 The Position of Environmental Policy ... 17

7. Incentives in Climate Contexts ... 19

7.1 Perspectives and key concepts ... 19

7.1.1 The foreign policy perspective... 19

7.1.2 The domestic policy perspective ... 20

7.1.3 The scientific perspective... 21

7.2 China’s priorities ... 21 7.2.1 Development ... 22 7.2.2 Economic growth ... 22 7.2.3 Sustainability... 23 7.2.4 Energy security... 23 7.2.5 Technological advancement... 24

7.2.6 Strategic development security ... 24

8 Opportunities and Limitations Beyond 2012 ... 25

8.1 The Kyoto heritage... 25

8.1.1 National emission commitments ... 25

8.1.2 The Clean Development Mechanism ... 26

8.2 Potential key issues beyond Kyoto... 28

8.2.1 Technology co-operation... 28

8.2.2 Internal actors and incentive structures... 29

9 Conclusions ... 32

Abbreviations and Acronyms

ADB Asian Development Bank Agr. agriculture

AIJ Activities Implemented Jointly AMM abandoned mine methane

APEC Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation ASEAN Association of South-East Asian Nations

BP British Petroleum

C carbon (chemical symbol)

C5 Canada-China Cooperation in Climate Change CAAC Civil Aviation Administration of China

CAS Chinese Academy of Sciences CASS Chinese Academy of Social Sciences CBM coal-bed methane

CCICED China Council for International Cooperation on Environment and Development

CCT clean coal technologies CCTV China Central Television

CDM Clean Development Mechanism

CERUPT Certified Emission Reduction Unit Procurement Tender

cf. confer (Latin: “compare”)

CH4 methane (chemical symbol)

CIIC China Internet Information Center CMA China Meteorological Administration CMM coal-mine methane

CNY Chinese yuan (international currency code) CO2 carbon dioxide (chemical symbol)

COC China’s Organizing Committee for the World Summit on Sustainable Development

DNA designated national authority

DRC Development Research Center of the State Council ERI Energy Research Institute

ESTH Environment, Science, Technology & Health Section of the United States Embassy Beijing

et al. et alia (Latin: “and others”)

EU European Union

EU-15 The fifteen Member States constituting the European Union from January 1995 to April 2004, i.e. Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom

g grammes GDP gross domestic product GEF Global Environment Facility GJ gigajoules

GONGO government-organised non-governmental organisation HFC hydrofluorocarbon

i.e. id est (Latin: “that is”)

IEA International Energy Agency

IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change kWh kilowatt hours

MCA Ministry of Civil Affairs MFA Ministry of Foreign Affairs MOA Ministry of Agriculture

MOC Ministry of Communications; Ministry of Construction MOF Ministry of Finance

MOFCOM Ministry of Commerce

MOST Ministry of Science and Technology Mt megatonnes

MWh megawatt hours MWR Ministry of Water Resources

N2O nitrous oxide or laughing gas (chemical symbol)

NBS National Bureau of Statistics

NC4 National Coordination Committee on Climate Change NDRC National Development and Reform Commission NGO non-governmental organisation

PCF Prototype Carbon Fund PFC perfluorinated carbon Res. residential

RMB rénmínbì (Chinese: “people’s currency”)

SEPA State Environmental Protection Administration SF6 sulphur hexafluoride (chemical symbol)

SFA State Forestry Administration SOA State Oceanic Administration STEM Swedish Energy Agency tce tonnes of coal equivalent

TFEST Task Force on Energy Strategies and Technologies toe tonnes of oil equivalent

Trpt. transportation TWh terawatt hours

UN United Nations

UNDP United Nations Development Programme USA United States of America

USD US dollar (international currency code) WTO World Trade Organisation

WWF Worldwide Fund for Nature

Summary

Climate change, as an environmental issue of transboundary significance, has brought about an international negotiation process and debate over global climate co-operation. A

centrepiece of this process is the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, signed during the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. More than ten years later, the world now faces the challenge of choosing the direction of its ongoing efforts to deal with and combat anthropogenic climate change. At the top of the agenda is the issue of how to progress in the wake of, and beyond, the Kyoto Protocol—the controversial declaration of ambitions from 1997, in which developed countries have committed themselves to limiting their emissions of greenhouse gases.

Carbon dioxide is commonly regarded as the most important greenhouse gas. Among the nations of the world, the United States and China are the leading carbon dioxide emitters, but of the two only China has approved the Kyoto Protocol. However, the treaty does not impose any quantitative restrictions on China regarding its emissions. The aim of this report is to analyse the following question:

What incentives, and what willingness and prospects, exist for more extensive participation by modern China in future international climate co-operation?

The climate issue may be viewed from a variety of perspectives. With Chinese conditions in mind, three dominate. These are (i) science, (ii) domestic policy, and (iii) foreign policy. Each of them sheds a different light on the issue. The scientific perspective on climate is

represented in China by an academic community with few channels to the much narrower circle of people that formulate and epitomise the two political climate perspectives. Alike in many ways, these, in turn, differ in that they are driven by separate paradigms. Whereas the main underlying concern of Chinese domestic policy is social stability, foreign policy is characterised by a strongly perceived need to uphold and defend China’s status and integrity in the eyes or the international community. Of course, climate science and domestic and foreign climate policy all interact and influence each other. However, in order to better grasp the ways in which the climate issue is perceived in China, it is helpful to view these

perspectives in parallel, rather than intertwined. For an outside observer, such a stance may be helpful in discerning such mechanisms and features that might cause confusion and make constructive international climate co-operation difficult. A concrete example of such

confusion is the process by which the country’s political leadership has arrived at its current position of openness towards the notion of China as a host to projects under the Kyoto

Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism. Depending on the insight and vantage point of the observer, this position may be understood as having taken shape either inscrutably and

haphazardly, or steadily and consistently.

China is a developing country. This general statement lies at the heart of the country’s standpoints towards international climate co-operation. It also constitutes the basis for at least six important priorities, which together envelop China’s involvement in climate issues as well as all its perceptions of the field. Without ranking them, these six priorities are: development, economic growth, sustainability, energy security, technological advancement and strategic development security. They are briefly described and commented on in the following paragraphs. The relative importance attributed to the different priorities varies depending on the context in which the climate issue is addressed. The term “context” is here meant to include the cast of actors involved, as well as their understandings of the set of relevant perspectives (i.e. science, and domestic and foreign policy) in combination with numerous other factors of greater or lesser significance.

Development is a central concept in Chinese politics, where it should be understood in a

positivist sense as a technology-oriented process of societal improvement. Modernisation is another expression of the same aspiration, which has bearing on domestic as well as on foreign policy. If the leadership fails to maintain the spirit of a positive development trend, it essentially endangers its claim to legitimacy as the people’s representative and agent. Therein lies the domestic importance of development. In terms of foreign policy, its significance pertains partly to strategic interests (cf. “strategic development security” below), and partly to international status. To China, prominence in the competition among nations is an important matter, and development is seen as an essential field in which the country must not lose ground, but advance.

Economic growth is seen both as a prerequisite for the ambitions of development and

modernisation, and as their chief indicator. It is mainly regarded as a domestic concern. Protectionism, national as well as local, constitutes a significant part of the ideas and ideals of how to create and shape economic growth. China’s membership of the World Trade

Organisation might, however, gradually influence such perceptions.

Sustainability, in turn, concerns the need not to limit the space for human sustenance,

for growth and development. Through this priority, environmental issues have made their way onto China’s political agenda. The major sustainability concern, which has confronted the Chinese leadership for decades, however, is more socially and demographically oriented. China’s efforts to curb population growth include the well-known, or infamous, single-child policy, which allows only one child per family. In China, sustainability issues are primarily considered a domestic matter.

Energy security is also a sustainability issue of sorts, and one which is intimately

connected to the challenge of climate change. It is also of particular significance in China. The country is dependent on domestic fossil coal as its predominant source of primary energy, but logistic difficulties, shortcomings in quality and efficiency, technical limitations, etc., are all causes for concern. At the same time, however, the importance of safeguarding energy supplies constitutes an argument for China’s sustained focus on the further development of so-called clean coal technologies.

Technological advancement naturally carries domestic as well as scientific weight. This

is expressed through the pursuit of a political environment that encourages and supports domestic innovation as well as research, development and demonstration. This priority also has relevance from a foreign-policy perspective, for example as a component of bilateral and multilateral development co-operation. The concept of technology transfer, which in China is seen as an important part of the wording and spirit of the Climate Convention, is often

associated with such contexts.

Strategic development security is in essence an expression of risk aversion. Here,

security is contrasted with the risk of jeopardising the momentum of development achieved over the past quarter century of reforms. In defence of this priority, the main argument is that China must not engage in experiments with novel development paths. The country has an obligation to its people to pursue courses of development that are secure, in the sense that they have already been proven effective elsewhere. Thus, China cannot assume a leadership role as an international testing ground for new, and therefore uncertain, policies and measures, as these might negatively affect the pace of development.

As is indicated by their descriptions above, each of the six priorities presented here is related to the other ones. They are also, though in varying degrees, related to three key concerns, which centre on China’s rights, on the obligations of the international community, and on natural limitations. The illustration below shows one way of representing the

Prioritised issues Key concerns

Development Economic growth Technological advancement Strategic development security

China’s rights

International community’s obligations

Energy security

Sustainability Natural limitations

To China, as a developing country, development, growth and technological advancement are inviolable rights, which must not be threatened. Sustainability and energy security constitute limitations, which nevertheless represent natural threats to the exercise of such rights, and which therefore warrant attention, at least domestically. Technological advancement and strategic development security are both aspects and parts of the moral obligation owed to China by the industrialised world. China is perceived to have the right to follow in the footsteps of other nations, which through their relative lead over China, as well as through their formal, international commitments, must be prepared to pave and show the way forward. Although not as articulated as the previously listed priorities, these three key concerns capture common and deeply rooted sentiments in China, well worthy of attention.

In general it is wise always to remain attentive to which of the above priorities and concerns that, in a certain context, constitute weak spots and the most serious obstacles to accord—not least when seeking to understand Chinese positions in the climate issue, and when engaging in climate discussions with Chinese representatives. The above illustration may be helpful in preparations for such contacts. It is also worth underlining here the potential importance of bilateral dialogues as opportunities to create mutual understanding, which in turn, and in the longer run, may allow agreement in subsequent multilateral discussions. Chinese policy positions are firm and typically rest on an intricate substructure. The country’s hierarchical make-up notwithstanding, its culture is strongly consensus-oriented. This means that internal support and approval from the appropriate authorities has to be established before public standpoints can be adopted. In the case of climate policy, a national co-ordination committee has been instituted for this explicit purpose. The insights brought forward in this report, including the ones presented so far, underpin the opinion that international leadership from China should not be expected where climate change issues are concerned. However, if conflicts originating in rhetoric and mistrust can be avoided, a constructive climate for co-operation ought certainly to be possible.

As a result of their global importance and their topicality in world politics, the challenges of climate change have developed into an issue distinctly and specifically dominated by the foreign-policy dimension. Thus, in China, they are also intimately

connected with national prestige. Therefore, it would be strategically favourable for items on the international climate co-operation agenda to centre more upon needs than on obligations and duty, in order to avoid such obstacles that may otherwise and perhaps unnecessarily arise. Needs, as far as China is concerned, are primarily linked to social stability founded on

discernable societal progression. In other words, shifting the weight from a foreign-policy to a domestic perspective is to be recommended.

It should be noted that observations and recommendations made in this report in no way are intended as urging the uncritical adoption of Chinese views and ideas. Instead, the

message is to emphasise the importance of reciprocal trust and appreciation of differences as key strategies to improve the conduciveness of international negotiations. The chances of reaching constructive future agreements can be furthered by supporting and participating in new, as well as existing, fora for informal and sincere exchanges of experiences and ideas.

On a more concrete level, concerning the actual willingness and scope for an expansion of Chinese participation in future international climate co-operation, a number of issues require specific attention. Barriers abound, not least within the foreign-policy sphere. There should nevertheless be room for greater Chinese involvement, although the ability of other stakeholders to appreciate the Chinese context may be instrumental and necessary in achieving progress. Some of the most important issues are commented on below:

National commitments. China, like the European Union and Sweden, has formally

approved or ratified the Kyoto Protocol. The provisions of the Protocol, including—for developed countries—the emission targets for the 2008–2012 commitment period, may therefore be seen as having a moral imperative, regardless of whether they ever legally enter into force. A breach of the treaty will not pass unnoticed by China, whose involvement in future climate agreements will not exceed the achievements of today’s developed countries. China has no intention of jeopardising its development policies. Therefore, the international community, in order to persuade the country to choose a new and more sustainable path of development, will first have to demonstrate that such a path is navigable. In addition, the word commitment has, in Chinese climate circles, attained strong connotations of the concept of sacrifice, which means that it cannot now be understood as something which confers benefits on the committed party. This interpretation effectively gridlocks any discussion about commitments by China. Consequently, in the Chinese context, a terminology centred on ambition is likely to be considerably more conducive to progress in climate performance. An example of a possible ambition—and one which, in a way, is already internalised in the international climate process through the mandatory submission by Convention parties of so-called national communications—could be openness regarding otherwise potentially sensitive environmental and climate-related information. In this area, concrete agreements on expanded future efforts could be arrived at, not least if Chinese domestic aspects are highlighted.

The Clean Development Mechanism. The Kyoto Protocol includes three so-called

flexibility mechanisms, which for countries with emission commitments may constitute channels by which to facilitate compliance. The Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) is one of these, and the only one to address climate co-operation between developed and developing countries. Concerns have been voiced over the CDM possibly becoming totally dominated by China-based projects. The probability or risk of this occurring, according to the arguments behind such concerns, could be considerable in light of China’s rapid industrial and economic growth—in combination with the substantial technical opportunities that exist for reducing the country’s greenhouse gas emissions. Remarks of varying seriousness have been made about the CDM as a presumptive “China Development Mechanism”. In China itself, however, a sceptical attitude towards the CDM has long been dominant. There were fears that developed countries would be able to use the mechanism as a means by which they could escape the moral obligation of addressing their domestic excessive greenhouse gas emissions, and shift the burden of climate change mitigation over to developing countries with far lower per-capita emissions. The efforts of such countries to modernise and progress would then be most unfairly impeded. These fears have now, in official circles, been reduced in light of the evolution of regulatory frameworks for the CDM, and China has accordingly declared its acceptance of hosting CDM projects. The concept of unilateral CDM projects is, however, rejected by the Chinese. Expectations on the actual effects of CDM in China are essentially moderate, even though the large potential for projects is also pointed out. A distillate of the observations made here would suggest that, with Chinese inertia in terms of climate co-operation in mind, as exemplified in the case of CDM, it would probably be counterproductive not to maintain, as much as possible, the momentum laboriously gained in this particular field—regardless of the fate of the Kyoto Protocol.

Technology co-operation. A commitment to the promotion and facilitation of

technology transfer from developed to developing countries is integrated into the Climate Convention. Ideas about what constitutes such promotion and facilitation, however, differ amongst stakeholders. From a Chinese perspective, the understanding of these concepts is wholly oriented towards tangible and government-driven action. This view contrasts the Western focus which gravitates more towards governance and incentive structures. Whereas a business project under the CDM, by Western standards, might well be considered as an element and act of technology transfer, such a stance can be indignantly viewed by the

Chinese as a violation of the very spirit of the Climate Convention. They expect governments, not business, as actors. In China’s view, the obvious lack of attention so far paid to “real” technology transfer in the climate context is an evident sign of the unwillingness and hypocritical attitude of Western nations towards concrete undertakings and actual delivery. Therefore, a significant step in the preparations for new agreements and treaties would be to explicitly bring this topic to the fore. In order to build faith one must first create an

overarching understanding about the fact that preconceptions about technology transfer are dependent on social order and context, as are the conditions for its promotion. It is essential to hold discussions, which address the often ignored or unrecognised differences in viewpoint that rankle in this part of the international climate process. Until such an opening is achieved, it is hard to see how these fundamental differences are to be bridged and constructive

agreements reached. For example, it is unlikely—in view of China’s centralist and

government-focused views on technology transfer—to win Chinese support for international climate co-operation in which actors within certain industrial sectors, rather than

governments, are contracting parties. A spontaneous embryo of something to this effect can nevertheless be observed within the global cement industry. On China’s part, there is interest instead in climate-related technical co-operation within the energy field. Like China, the United States rely on a large share of fossil coal in their energy supply. Consequently, since the two countries in this respect may be thought to face similar technical challenges, China anticipates that there will be room for an expanded exchange of mutually beneficial

knowledge, experience and technology. In relation to the European Union, where the proportion of coal in the energy supply is considerably smaller, it is instead developments within renewable and alternative energy sources that attract Chinese interest. This field is also one in which Sweden may be well suited for participation.

Internal actors and incentive structures. China is a vast country with a complex

structure of governance. This is an important fact to remember when assessing and trying to understand Chinese positions—not least in the context of climate co-operation. There are, in all, few domestic actors that possess insight and competence in China’s climate policy. The ones that exist are all to be found at central level, whereas the decisions that in reality affect actual climate performance are made by a multitude of completely different actors, who far from seldom are out of step with the preferences of the central leadership. Tradition, however, decrees an appearance of outward unity and conformity, obscuring domestic dissent as well as flaws in the observance of policies. Instruments to promote incentives for increased actor involvement are already part of a Chinese wish list. Much could probably be gained in this respect from an increase in transparency within public administration as well as in its relation to business and industry. Reliable reporting and policy compliance are always on the agenda of environment policy in China, and although much has been accomplished over the past thirty years, grave problems still abound. Industrial emissions in China could, however, be significantly reduced if a presumptive and progressively greater openness in reporting were to occur, leading, in turn, to increased possibilities for the implementation, control and

In conclusion, the following items of importance may be underlined. • Realistic expectations based on an awareness of China’s priorities. • Platforms for sincere dialogue untainted by matters of prestige.

• An agenda that recognises the needs and the situation of developing countries. • China’s climate ambitions, rather than its prospective commitments.

• Use and progression of already gained momentum and agreement (such as the CDM). • An earnest readiness to address different understandings of what technology-based

PART I: Overview

1 Population and Government

The People’s Republic of China was founded on 1 October 1949 and according to its 1982 constitution it is a “socialist state under the people’s democratic dictatorship”. At the highest administrative level the country consists of four municipalities, 22 provinces1 and five autonomous regions. Apart from these, there are two autonomous “special administrative regions”, Hong Kong and Macao. In the most recent census (2000), the population of China not including Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan was just under 1.27 billion2. More than 91 per cent of the population belong to the han ethnic group (Daniel 2003). The remaining eight to nine per cent belong to 55 recognised minority populations.

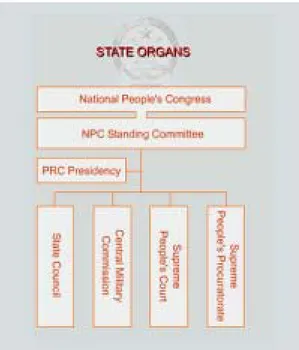

The Chinese Head of State is the President (Hu Jintao). The highest political and legislative organ is the National People’s Congress, which convenes for two weeks a year. When it is not in session, it is represented by a Standing Committee. Members of the National People’s Congress represent constituencies that consist of the people’s congresses of the next lower administrative tier and the People’s Liberation Army. Executive power is vested in the cabinet, called the State Council, led by the Premier

(Wen Jiabao). The cabinet has ministers who head ministries or state commissions.3 At the same level as the State Council are the Central Military

Commission, the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate, see Figure 1. The Chinese Communist Party exercises great influence over the state apparatus, including leading the National People’s Consultative Conference, the National Committee of which is organised in the same way as the National People’s Congress, but whose members represent the Communist Party and other approved political parties and organisations. The National Committee may be seen as a sort of upper chamber to the National People’s Congress. The term of office of all central political institutions is five years (CIIC 2003, Daniel 2003). Structures of authority at lower administrative levels mirror the structure of central government.

2 Economic Profile

Development of the economy of modern China from that of a planned economy to a mixed economy began with the launch of the Open Door policy under Deng Xiaoping after 1978 (Riskin 1987). This new policy was a marked change from the isolationism that had

characterised the previous years and the officially recently completed Cultural Revolution. In the quarter-century since then, Chinese society has undergone sweeping social, political and

1 The province of Taiwan is not included here since its government is not sanctioned by the People’s Republic of

China.

2 Throughout this report, the word “billion” is used in the meaning “thousand million”, i.e. a factor 109. 3 The State Council also includes a number of vice-premiers and state councillors, as well as the State Council

Secretary General, the Auditor-General and the Governor of the People’s Bank of China.

Figure 1. Chinese central government

economic change. The state five-year plans have changed from being obligatory to being targets, agriculture has been decollectivised, state-owned industry has been turned into corporations, private enterprises are permitted, foreign investment is accepted and a number of institutional reforms have been implemented (Zhao 2001). The ambitious political goal of quadrupling the country’s economic activity and GDP from 1980 to 2000 was achieved in 1995, far ahead of time (Bach and Fiebig 1998). Measured in a stable value of money (1995 CNY4), GDP climbed from 1 400 billion yuan in 1980 to 8 700 billion yuan in 2000 (Fridley 2001, Table 10B.1.2; cf. Table 1 below). It is hoped that this performance can be repeated: a new quadrupling target has been announced for the 2000–2020 period (DRC 2003). China is already one of the world’s leading nations in terms of GDP, second only to the United States if counted in purchasing power parity (IEA 2002) – but counted per capita, the picture is of course different (see Table 1). The composition of the economy has changed apace with its growth. From 1979 to 1999, agriculture’s share of GDP fell from 31 to 17 per cent while that of the service economy increased from 21 to 33 per cent. Industry’s share was just under 50 per cent at the beginning as well as at the end of the period (Fridley 2001, Tables 10B 1.3, 4, 6; cf. UN 2003, Table 22). The corresponding figure for Sweden in the mid-1990s was just over 2 per cent for the land-based industries, just under 70 per cent for the service sector and just under 30 per cent for industry (UN 2003, Table 22).

Table 1. GDP 2000 for China, Sweden and the USA Source: IEA 2002, Table 8

GDP (billion 1995 USD) GDP per capita (1995 USD) exchange rate

based power parity purchasing exchange rate based power parity purchasing

China 1 000 4 700 820 3 700

Sweden 280 200 31 000 23 000

USA 9 000 9 000 33 000 33 000

China’s economic expansion has been revolutionary and not without problems. One of the most important political goals of central government, as pointed to in recent years, is the evening out of increasing geographical imbalance in economic development (COC 2002). The gap between the centres of growth along the eastern and southern coasts and the poorer

western inland provinces has grown incessantly. Increasing unemployment in the wake of reform of state-owned industry also threatens the stable social development that is the overriding goal of the state. In addition, the fast growth of non-state, primarily small-scale industry in the 1980s and 1990s exacerbates acute and long-term environmental problems (Economy 2003, 1998).

3 Energy Profile

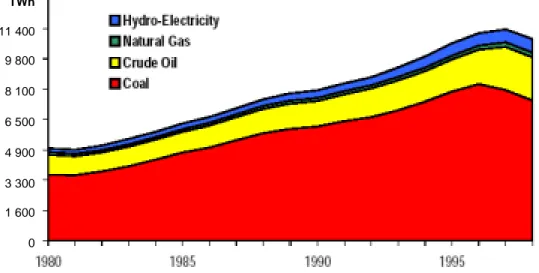

China uses a lot of energy. The country is today the second largest global energy user after the United States (Fridley 2001, Halldin 1998). Of course, figures vary according to information source and method of calculation, but Figure 2 gives an idea of current levels. Of total global

4 The Chinese currency, the yuan (CNY), has for many years followed the value of the USD at an exchange rate

of just under 8.28 yuan to the dollar. At the time of writing (December 2003), this corresponds to approximately 1.13 yuan to the Swedish crown. (In China as well as in international contexts, the currency abbreviation RMB is often used, which is short for rénmínbì, “people’s currency”).

commercial primary energy use of about 98 000 TWh5 in 1998,the USA consumed 24 000 TWh and China about 11 000 TWh (Fridley 2001, Table 9B.2.26). These numbers may be compared with the corresponding Swedish figure of 620 TWh (STEM 1999, Figure 1). Chinese energy supply has two important characteristics; these are the domination of coal as an energy source, and industry’s large share of energy use. As a rule of thumb, both amount to around seventy per cent. The explanations for this are that China is rich in coal while other conventional energy raw materials are much less available, and that Chinese industry on the whole has poorer energy performance than corresponding production in many other countries.

TWh 11 400 9 800 8 100 6 500 4 900 3 300 1 600 0

Figure 2. Chinese commercial primary energy use Source: Fridley 2001, Figure 4A.1.2 China’s energy use has increased considerably over the past twenty-five years. At the same time, the amount of biomass used for energy purposes outside the commercial energy market is regarded as having remained more or less constant at about 1 800–1 900 TWh. Bioenergy’s share of the total energy balance has therefore probably been more or less halved from almost 30 to less than 15 per cent from the early 1980s to the late 1990s. The mix of energy carriers in commercial primary energy use, however, has not changed significantly. The proportion of coal has typically stayed between three quarters and two thirds, while oil has taken up about one fifth and natural gas only one or two per cent, if that. Primary electricity’s share – mainly consisting of hydroelectric power – has shown considerable growth, but from a low level (Fridley 2001, Table 2A 1.3, Table 4B.1). For more detailed analysis of this, see the fact box on energy statistics in China (pages 6–7). The overwhelming share of Chinese electricity production is thermal, with fossil coal as primary energy source. Great efforts have been made in recent decades to increase the degree of electrification in China. In 2002, 98 per cent of the population had access to electricity (Yang 2003), which is very high for a developing country. The remainder, however, represents a very large number of people. Twenty million people, or almost five million households, are still not connected to the electricity supply (Yang and Yu 2004). What is remarkable, is that the great increase in Chinese energy use over the past twenty-five years still seems moderate compared to the economic growth over the same period. Roughly speaking, nominal GDP has more than quadrupled while commercial energy use has only doubled. This means that a more than 50 per cent reduction in the energy

5 In agreement with Swedish tradition, this report uses the watt hour as the base unit for all energy, not only for

electricity. For further comments on energy units, including a conversion table, see the fact box on pages 6–7.

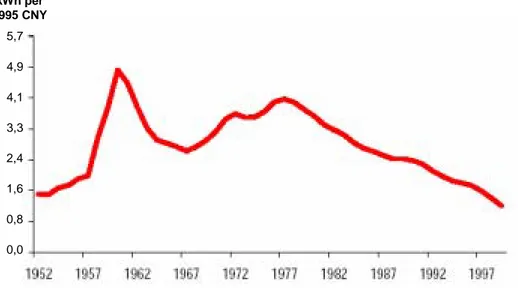

intensity of the Chinese economy has been achieved in a period of unequalled growth. Figure 3 shows the clear break in trend of the development of energy intensity that followed the introduction of the Open Door policy. (The figure also clearly shows the Great Leap Forward: the massive but failed industrialisation campaign of the late 1950s.) Despite all of this, there is still great potential for energy savings in China, not least in industry.

Figure 3. Energy intensity in the Chinese economy Source: Fridley 2001, Figure 4B.2

Coal will continue to be the most important energy carrier in China’s energy supply for a long time to come. The Chinese Energy Research Institute (ERI) recently published a

comprehensive report called China’s sustainable energy scenarios in 2020 (Zhou et al. 2003, Sinton et al. 2003), in which three scenarios are presented. The baseline has been called “Ordinary Effort” and the other two “Promoting Sustainability” and “Green Growth”, see Figure 4. All scenarios assume that the economic target of quadrupled GDP to 2020 is met, but they differ in how it is achieved. The differences affect how the energy carrier mix and the economy’s energy elasticity are expected to develop.

kWh per 1995 CNY 5,7 4,9 4,1 3,3 2,4 1,6 0,8 0,0

0 2000 4000 6000 8000 10000 12000 14000 16000

coal oil natural gas primary electricity

TWh

1998: 11 000 TWh

2020 Green Growth: 19 000 TWh

2020 Promoting Sustainability: 22 000 TWh 2020 Ordinary Effort: 25 000 TWh

Figure 4. Scenarios for China’s commercial energy use Source: Zhou et al. 2003, Table 7.7

Another fresh report produced by the China Council for International Cooperation on Environment and Development (CCICED) makes projections to 2050 of China’s expected energy supply (Ni and Johansson 2004, TFEST 2003). In total energy quantity and in general terms the report follows the ERI scenario Green Growth. It also assumes that the pace of energy increase will remain stable during the decades between 2020 and 2050, which would mean a total energy supply of around 30 000 TWh in the middle of this century. Moreover, the report describes two different ways in which to achieve this supply: conventional technology and advanced technology. These alternatives show radical differences in

performance, both in terms of energy supply security and environmental impact. The report describes the risk of three growing problems, which may be dealt with by actively promoting the second alternative. These problems are (1) harmful overdependency on imported oil, (2) environmental damage causing rapidly growing stress on the economy (from costing over seven per cent today to thirteen per cent in 2020) and (3) unharnessed increases in the emission of greenhouse gases. The technology mainly promoted in the report is coal gasification, but ordinary natural gas, coal-bed methane7 and renewable energy sources are also proposed as increasingly important energy carriers in the future. Concrete indicators of the performance of the advanced technology scenario include: claims of reduced sulphur dioxide emissions from 24 Mt in 1995 to 16 Mt in 2020 and 8.8 Mt in 2050, of a limitation of import dependency on oil and natural gas to thirty per cent, and of a ceiling for China’s cumulative carbon dioxide emissions at 66 billion tonnes of carbon.

Fact Box. Energy Statistics in China

Statistics for the late 1990s show a remarkable trend in the developments of China’s energy sector, as supply and use of energy declined at the same time as economic growth continued to be high. This peculiar circumstance was the object of much attention and debate in circles that monitor and carry out research on Chinese development (ESTH 2001, Sinton 2001). With hindsight, the situation can be somewhat better understood, but exact details behind the figures remain elusive and diffuse (Sinton and Fridley 2002).

The quality of official Chinese statistics deteriorated drastically in the second half of the 1990s in the wake of the institutional changes implemented at that time as part of the transition from a planned to a market economy. The

changes took place at roughly the same time as central authorities introduced strict policies on technical minimum performance in a number of key industrial sectors such as coal mining and cement manufacture (ZKG International 2002, Wiemer and Tian 2001, Zhao 2001, Sinton and Fridley 2000). These regulations and their expected effects on production affected industrial energy reporting from local and provincial statistics authorities to the central National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), which received data that more poorly than before mirrored the actual situation. Similarly, industrial incorporation, and the shift of influence over more and more industrial enterprises away from the direct control of the authorities, led to a deteriorating statistical base and gave rise to lags in state data collection (Rawski and Xiao 2001, Wang and Meng 2001). Afterwards, attempts have been made to correct the statistics for these types of errors, and updated versions of the national energy statistics show a smaller downward trend (Sinton and Fridley 2003). Nonetheless, there is reason to suspect that the marked increase reported for the first years of this century partly conceals a return to the statistics of enterprises that in the late 1990s avoided being represented in the figures. The Californian

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory regularly monitors and comments on Chinese energy statistics, and it edits and publishes a compilation of international statistics devoted to this particular field, called the China Energy Databook

(Fridley 2001).

In China, and when Chinese circumstances are presented, the usual unit for supply and use of energy is not based on the joule, nor on watt hours or even oil equivalents. Instead, coal equivalents are usually used, where a tonne of standard coal equivalent, 1 tce, equals just under thirty gigajoules, just over eight megawatt hours or about seven hundred kilogrammes of oil equivalent (see conversion table below). This report, however, consistently uses watt hours as the unit of energy, in accordance with Swedish tradition. In international literature this is a unit

generally used only for electrical energy. In converting between energy units, one should pay attention to how primary electricity (like hydroelectric power) is counted. There are two different methods. One is based on the factors in the conversion table, while the other compensates for conversion losses, i.e. the fact that primary electricity, if replaced by electricity from thermal power production, requires a larger input of fuel than what its actual energy content suggests. This way of calculating is often used in China and means that 10.0 MWh of

hydroelectric power is recalculated in the statistics to 4.04 tce. Not all literature applies this method however, meaning that information about the proportion of primary electricity in the Chinese energy supply can show large apparent differences between different sources.

Fact Box. Energy Statistics in China

Conversion table. Conversion factors with three significant figures

GJ tce MWh toe

10.0 0.314 2.78 0.239

29.3 1.00 8.14 0.700

36.0 1.23 10.0 0.860

41.9 1.43 11.6 1.00

As a curiosity, it can also be mentioned here that an average tonne of Chinese raw coal does not equate to a tonne of coal equivalent, but only to 0.714 tce (Fridley 2001).

4 Climate Indicators

Reports of greenhouse gas emissions are the most common indicator of a country’s climate performance. Chinese emissions are presented below and are supplemented by a brief status description of China’s position in international climate policy. Indicators that focus more on the impact of climate change, such as meteorological and biological factors, are not discussed in this report.

4.1 Carbon dioxide profile

China as a nation is the second largest global source of anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions. Many believe that in fifteen to twenty years, the country will in this respect have overtaken the United States, which currently emit most, but of course opinions vary (Johnston 1998, van Vuuren et al. 2003). Figure 5 below shows how carbon dioxide emissions have developed in the five largest emitting nations in the latter part of the 20th century.8

In 2004, China will submit its first so-called national communication to the secretariat of the Climate Convention, containing detailed descriptions of the country’s emissions of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide. Ten years will have passed since the reporting of the first comprehensive China greenhouse gas study, which was carried out with the aid of the Global Environment Facility (GEF) (Johnson et al. 1996). This report, which used the Kyoto

Protocol reference year 1990 as its point of departure, gave an early and preliminary compilation of China’s greenhouse gas emissions.

8 Those interested in comparing the carbon dioxide emissions of various countries can find on the Internet a data

compendium maintained and updated by the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee (Marland, Boden and Andres 2003). The address is http://cdiac.esd.ornl.gov/trends/emis/em_cont.htm.

Figure 5. Carbon dioxide emissions from the USA, China, USSR (–91), Russia (92–), Japan and

India Source: Fridley 2001, Figure 9B.17.1

According to the study, Chinese carbon dioxide emissions in 1990 were just under 680 millions tonnes of carbon, distributed by sector as shown in Table 2. Carbon sinks in the shape of woody plants and ground sequestration were estimated at seven million tonnes of carbon.

Table 2. China’s carbon dioxide emissions in 1990 by sector Source: Johnson et al. 1996

Fossil fuel use Process9

650 Mt C 29 Mt C

Electrical power production and industry Res. Trpt. Agr. Other

75 % 14 % 4 % 3 % 4 % Σ 100 %

A B C D E F G H

32 % 15 % 12 % 10 % 10 % 4 % 4 % 13 % Σ 100 %

A: Power B: Energy production C: Building materials D: Iron and steel E: Chemicals F: Food and tobacco G: Machinery H: Other industry

More studies of China’s carbon dioxide emissions were carried out in the 1990s. One funded by the Asian Development Bank (ADB), was completed back in 1993. The GEF study described above was completed the year after. Two studies, funded by the US Department of Energy and the ADB, respectively, were both finished in 1998 (Sinton and Ku 2000, Heij et al. 2001, Ramakrishna et al. 2003). Generally, it can be said that the two earlier studies indicate somewhat higher carbon dioxide emissions in China in 1990 than the later ones do. The 1998 ADB report gives emissions in the reference year of the magnitude of 550 million tonnes of carbon from fuel and 26 million tonnes from industrial processes. Sinks were estimated at ninety million tonnes of carbon. Distribution by sector is roughly the same, however, as in Table 2. Distributed by energy carrier, solid fuels (i.e. largely coal) give rise to

9 For all practical purposes, China’s industrial process emissions may be said to originate from cement

just under 85 per cent of energy-related emissions, liquid fuels (i.e. petroleum products) just under 14 per cent, and natural gas just over one and a half per cent (ADB 1998, Table 3-6).

As a comparison with the above figures, Swedish carbon dioxide emissions in 1990 were 15 million tonnes of carbon, of which one million tonnes resulted from industrial processes and the rest was due to energy use (Miljödepartementet 2001). Carbon sinks were equivalent to five and a half million tonnes.

In the 1990s, statistics for Chinese carbon dioxide emissions continued largely to follow the energy statistics, which of course means that the same uncertainty exists concerning developments in the later years of the period as described in the fact box on pages 6–7.

According to these figures, Chinese carbon dioxide emissions, starting in 1990, first increased by over thirty percent up to 1997 and then fell over the next three years. Emissions have climbed steeply, however, since the turn of the century. According to BP’s statistics, carbon dioxide emissions in China in 2002 exceeded 1990 emissions by almost forty percent (over 910 Mt C in 2002 compared to just under 660 Mt C in 1990) (Zittel and Treber 2003, Table 2 and Figure 6), and the upward trend continues.

China also continues to have the world’s most carbon-dioxide intensive energy supply. This remains true in spite of the fact that intensity fell somewhat, from, in 1990, 3.5 tonnes of carbon dioxide per tonne of oil equivalent in primary energy supply, to just over 3.3 tonnes in 2002 (but with a climbing trend from 2000). In comparison, the United States during the same period remain rather constant at around 2.7 tonnes, as does India at approximately 3.2 tonnes. The countries of EU-15 and Russia, however, both show falling intensities from 2.6 tonnes in 1990 to 2.4 tonnes in 2002 (Zittel and Treber 2003).

There are several scenarios for China’s future carbon dioxide emissions. Based on the IPCC’s (the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) Special Report on Emissions Scenarios from 2000, the ERI has produced six scenarios for the period up to the beginning of the next century (Jiang 2002, cf. van Vuuren et al. 2003). According to these scenarios

projected emissions in 2100 range from just over half a billion tonnes of carbon at the lowest to just under five billion tonnes of carbon at the highest. The reference scenario follows a steadily climbing trajectory until 2050, after which it levels out and ends up at around three and a half billion tonnes by the end of the century, see Table 3.

Table 3. A reference scenario for China’s future CO2 emissions Source: Jiang 2002, Table 2

Year 2010 2030 2050 2100

Primary energy [TWh] 15 000 27 000 46 000 75 000 CO2 emissions [Mt C] 1 100 2 000 3 300 3 500

These estimates are lower than those of the 1994 GEF study, which predicted that China’s carbon dioxide emissions would, in the reference scenario, amount to some 2 200 million tonnes of carbon as early as 2020 (with a span to the lowest scenario of only 330 million tonnes.) The 1998 ADB study also calculated scenarios for 2020; one reference scenario and two abatement scenarios. These results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Three scenarios for China’s carbon dioxide emissions in 2020

Source: ADB 1998, Tables 1-7 and 1-8

Scenario Reference Abatement-I Abatement-II

Year 2010 2020 2020 2020

Primary energy [TWh] 18 000 24 000 21 000 19 000 CO2 emissions [Mt C] 1 300 1 700 1 400 1 300

4.2 Other greenhouse gases than carbon dioxide

An appendix to the Kyoto Protocol, called Annex A, specifies the substances defined as greenhouse gases by the agreement. Besides carbon dioxide (CO2), the list includes methane

(CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), sulphur hexafluoride (SF6), and the group of chemicals consisting

of both completely and partially halogenated fluorocarbons (HFC and PFC compounds). Along with carbon dioxide, methane is of particular importance in China, but it is very difficult to estimate the scope of methane emissions. The greatest sources, however, are rice cultivation, coal mining and livestock keeping. Of China’s greenhouse gas emissions in 1990 (according to the GEF study completed in 1994 and limited to carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide), methane at 36 million tonnes was equivalent to thirteen per cent, counted in carbon dioxide equivalents. Nitrous oxide, according to the same study, was just over two per cent. But as has been said, there are great uncertainties in these measurements. For example, methane release from rice cultivation is said to vary within the quite wide interval of 0.2–0.7 g per square metre and day (Johnson et al. 1996).

In discussions about China’s climate performance, and apart from carbon dioxide, the methane released by coal mining has attracted particular attention. Geological coal deposits can contain considerable amounts of methane, and the gas has long been known as a safety risk in mining. The gas also makes a large contribution to the greenhouse effect if it is released freely, but if is collected it can be used, like ordinary natural gas, to reduce the proportion of coal in primary energy use. There is a large technical potential for such methane capture in China. In climate and energy contexts, therefore, coal-bed methane(CBM), coal-mine methane (CMM) and abandoned coal-mine methane (AMM) are seen as important untapped natural resources (Haugwitz 2002).

4.3 Chinese climate policy in brief

Since the entry into force of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1994, China is a non-Annex I participant within international efforts to address the climate issue. The work of completing the country’s first national communication under the Climate Convention is still underway (in December 2003) but is in its final stages. The report is expected to be received by the Convention Secretariat in Bonn during 2004.

The main feature of China’s international climate policy is the principle of all countries’ common but differentiated responsibilities for measures addressing the threat of climate change. The official interpretation of this principle means that Chinese commitments to limit emissions of greenhouse gases cannot be accepted until (1) the developed countries accept, and act upon, their responsibility and (2) China has achieved an economic standard (in per capita GDP) that corresponds to an average developed country. The latter condition might, according to some estimates, be expected to be fulfilled at some point in the middle of this century (Haugwitz 2002). China’s position should not, however, be understood to mean that the country does not intend to take steps to limit emissions, but rather that such steps will be taken on China’s own terms.

China’s domestic climate policy is strategically subordinate to the issue of sustainable development, which covers a wide range of subjects whose common feature is that they touch on the country’s prospects of a continued and stable increase in wealth and welfare. These subjects include economic growth, demographics and resource allocation, as well as issues concerning health, environment and supply issues etc. Therefore several central authorities are

involved.10 In time for the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg in 2002, the government had a report compiled that describes the country’s challenges and strategies in its attempts to achieve greater sustainability (COC 2002). There is awareness in the central leadership that anthropogenic climate change threatens to hamper the country’s development, and so it is admitted that the climate issue is important to China. So far, however, this awareness has not spread much within authorities, neither national ones nor at lower political levels, nor within society at large. This means that local support for climate policy is poor.

The announcement of China’s formal approval11 of the Kyoto Protocol was made at the

Johannesburg summit in 2002. China agrees to act as a host country for projects under the Clean Development Mechanism, and the building of national capacity and the creation of institutions necessary for such participation are underway. (ESTH 2003b.)

5 The Climate Arena in China

To obtain an overview of the factors that define China’s climate position and describe its dynamics, it is important to see the Chinese climate arena. In this context the word “arena” refers to the relationships between actors, i.e. such groups and institutions in society whose attitudes and actions jointly define China’s climate impact. The following sections comment on a number of actors and structures of particular importance on the Chinese climate arena. This overall description begins with the sphere of public administration and is then extended in subsequent paragraphs to other groups of actors. It should be emphasised that when

discussing authorities, this report focuses on the national, Beijing-centred climate arena, while in a country as big as China – with its multitude of administrative tiers – there are of course sub-arenas at many levels. A more detailed discussion of the importance of this tiered structure for climate engagement is found under the heading “Internal actors and incentive structures” in section 8.2.2 of the report.

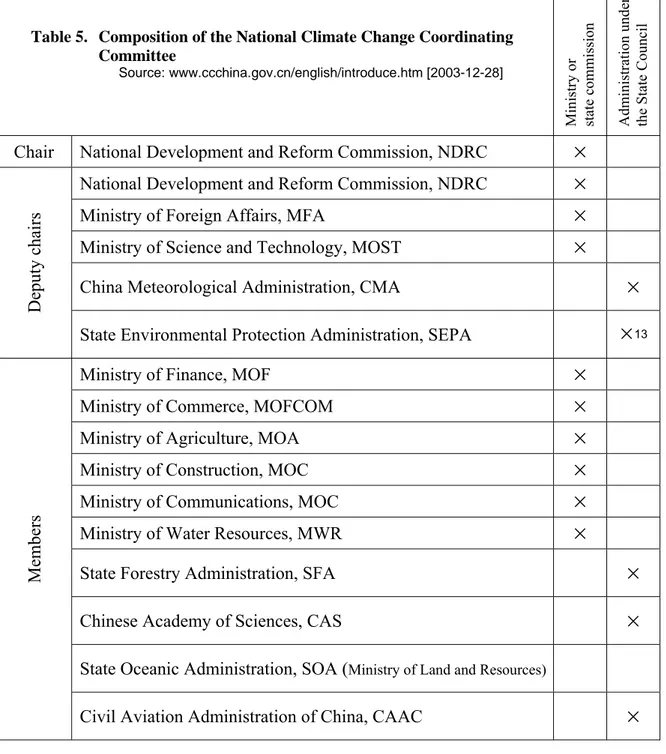

5.1 Institutional structure for processing climate issues

The two most important authorities from the point of view of climate issues are the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), which leads the Chinese negotiating delegations to the conferences of the parties to the Climate Convention, and the National Development and Reform

Commission (NDRC). For climate decisions and consensus-building at the central

government level, there is the National Coordination Committee on Climate Change (NC4)12, which is located at and chaired by the NDRC. The committee members are vice-ministers or deputy director-generals of ministries and state commissions or administrations. Table 5 shows the composition of the committee. When the predecessor to the current committee was established in 1990, responsibility rested mainly with the China Meteorological

Administration, which builds, supervises and collects scientific competence in the field, and which is China’s focal point for the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change(IPCC). As the climate issue has entered the realm of politics however, strategic responsibility has shifted, and since the 1998 reforms of China’s national institutions, the NDRC has had the co-ordinating role (Zhang 2004b, Zhao 2001.) The NDRC will also function as China’s

Designated National Authority (DNA) for the Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism (Zhang 2004b).

10 The National Development and Reform Commission and the Ministry of Science and Technology are

particularly important. For example, China’s national Agenda 21 office is run by the latter. Information about sustainability and Agenda 21 is posted on the Internet at www.sdinfo.net.cn/english/ and

www.acca21.org.cn/english.

11 Approve in this context is equivalent to ratify. See the first paragraph of Article 25 of the Kyoto Protocol. 12 www.ccchina.gov.cn/english/

Mi ni st ry or state commissi on Ad mi ni st rat io n u nde r th e State Council

Chair National Development and Reform Commission, NDRC

×

National Development and Reform Commission, NDRC×

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, MFA×

Ministry of Science and Technology, MOST×

China Meteorological Administration, CMA×

Deputy chairs

State Environmental Protection Administration, SEPA

×

13Ministry of Finance, MOF

×

Ministry of Commerce, MOFCOM×

Ministry of Agriculture, MOA×

Ministry of Construction, MOC×

Ministry of Communications, MOC×

Ministry of Water Resources, MWR×

State Forestry Administration, SFA×

Chinese Academy of Sciences, CAS×

State Oceanic Administration, SOA (Ministry of Land and Resources)Members

Civil Aviation Administration of China, CAAC

×

5.2 Competence centres for climate policy and climate science

Research and knowledge gathering in the field of climate science take place at many locations in China, and not just in Beijing where the China Meteorological Administration is the key actor. Several large universities in other parts of the country carry out this type of work. With regard to climate policy issues, however, the situation is different, largely due to their

strategically important and foreign-policy related nature. There are therefore no plans to

13 SEPA is a national administration directly subordinate to the government (unlike administrations that are

subordinate to ministries and state commissions), but since the 1998 reforms of government institutions, its leader has the rank of minister.

Table 5. Composition of the National Climate Change Coordinating Committee

establish co-ordinating committees like the NC4 at provincial levels. Those climate-policy oriented competence centres that do exist are largely concentrated to Beijing, and the number of people working on these issues is limited. The important academic institutions in the field are Tsinghua University and to some extent Beijing University. The leading bodies of the NC4 also have research units or advisory departments that specialise in climate policy issues. The ERI, of course, which is affiliated to the NDRC, plays a very important role, but SEPA and MOST also have units that are active in the field. There is also an important node at CASS, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. But the number of people engaged in the core issues of climate policy is small.

5.3 Trade and industry and the climate issue

The importance of trade and industry for China’s climate performance can hardly be overestimated. Within these sectors it is industry, representing the largest share in the

country’s coal-dominated energy supply, that has the most impact. This applies particularly to the highly coal-intensive industries in power, cement and iron and steel production. In spite of its status as a developing country, China is highly industrialised. At the same time, however, only thirty per cent of the population is counted as urban (Zhou and Ma 2003). Reflecting these circumstances, China’s industrial structure is different from most other countries, both in that it to such a large extent consists of small-scale rural industries, and in the fact that these exist not only in light manufacture but also in heavy industrial sectors such as mining and in the other sectors mentioned above (Maddison 1998, Pei 1998).

Important in Chinese trade and industry is the heritage of decades of planned economy. It affects how businesses are run and manifests itself through widespread state and collective ownership. It affects practical operations and strategies, since political aspects, particularly local ones, often carry great weight (Zhao 2001, Pei 1998). Furthermore, it is visible in the fact that the organisational structure of trade and industry mirrors that of public

administration, with management that is highly fragmented and spread over many small units. Large industrial groups by contrast are less common, even although they are regarded as increasingly important and encouraged from higher political levels (Smyth 2000). On the whole, the existing structure presents difficulties to industrial organisations that wish to operate vertically, creating instead strong horizontal ties of dependency and loyalty between individual businesses and local authorities. Thus, the Chinese Enterprise Confederation, a central industrial interest group that among other things addresses issues such as energy and the environment (mainly in the form of environmental management systems), works in

completely different conditions than does for example the Swedish Confederation of Industry. And since climate policy in China so far has extremely limited distribution outside the central political level, it is easy to see that climate performance is a non-issue for most actors in Chinese trade and industry.

For foreign actors, the Chinese market is still an arena hard to penetrate. This also has to do with the legacy of a planned economy which encourages local protectionism at the same time as market reforms have given local actors more economic power at the expense of central control (Zhao 2001, Economy 1998). China is indeed open to foreign investment, but creating good relationships with local authorities and an atmosphere of mutual trust can require great effort on the part of foreign companies that through ownership wish to establish a foothold in the country. Foreign owners are still an unknown element in business tradition in most places in China, and can often be regarded by local officials as a threat to their influence over developments in the area, region or province. A foreign investor therefore often

encounters many demands and limitations that are not applied to domestic businesses. Since China formally supports the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), there is at least theoretical support for the promotion of industrial initiatives for improved climate

performance, for example through greater energy efficiency. Unlike several other countries however, unilateral CDM projects are not accepted in China at present (Zhang 2004b,

AM-CDM 2003). Involvement by foreign actors is therefore necessary already at the initiation stages of the project, but the host business must still be wholly or mainly Chinese owned.

Obstacles to the establishment of privately or enterprise initiated CDM projects in China can be expected. The fact that knowledge and awareness of the climate policy of the central authorities is poor reduces the trust of local businesses and authorities in the CDM concept (Wang and Yan 2003). In coal-intensive electricity production, for example, Chinese actors are experiencing and expecting, in the next few years, a strong increase in demand. This currently leads to massive investments in new production capacity, including small-scale coal power. In spite of the potential for greenhouse gas prevention measures, the CDM is not regarded as an attractive prospect by the sector. Capital for new installations is often not a problem, particularly in the light of the expected increase of demand, and the involvement of central bureaucracy that a CDM project would involve makes it less attractive. Apart from CDM bureaucracy, there remains, from the point of view of foreign actors, the already complex and difficult procedures associated with regular market establishment in China. The process for launching a CDM project, and having it properly approved, will not in the

foreseeable future be coordinated with the permit and establishment routines that otherwise apply, or in any other way change them.

From what has been said above, it is apparent that the promotion of climate measures in Chinese industry is not without problems. This includes not least CDM activities oriented towards energy efficiency measures. Despite this, foreign companies are still expressing their interest in the mechanism. Chinese actors working with renewable energy technology also express hopes about the CDM. (A more detailed discussion of the prerequisites for CDM in China is presented in section 8.1.2 of this report.)

Improving active climate involvement on the part of Chinese industry will require many measures on a broad front, among other things in capacity building. In this respect, activities are underway or being prepared, supported and initiated by central climate-policy circles in Beijing (World Bank et al 2004, ADB 2002). The close ties between industry and local political administrations need to be loosened, however, in order to reduce protectionism, to deal with fragmented corporate structures, etc.; circumstances that combine to make the implementation of central initiatives and policies more difficult.

5.4 Civil society

The most important actor in a society is, in the end, the individual: all those who together make up the collective citizenry. This collective should not be disregarded in an overview of the climate arena, even if it is not meaningful to try and treat it as a single unit. There are, however, institutions that can be used as tools for bringing about a heightened focus on climate issues within the citizenry, thereby allowing it to influence, and be influenced by, official policies. Some important channels of this type will be commented on in this section.

Generally speaking, it is clear that public awareness of climate science and climate policy is very poor in China. This means that seen from a climate perspective, the population – including trade and industry – is not a particularly constructive actor. If people are to become more willing to get actively involved, downward communication towards the individual is necessary, and if the collective is to exercise influence upwards, it is also necessary that there are two-way channels that permit dialogue. The latter type of phenomenon, however, can be a sensitive thing in China, since, in Chinese government tradition, unsanctioned political activism has a tendency to be seen as a threat to society.

5.4.1 The media and educational institutions

In China, the role of the media differs somewhat from than in Sweden. Social order, security and stability are the most prominent concerns of China’s political leadership. The media and their news coverage have the important task of showing the population how this concern leads to steady improvements for the individual, both in the fight against threats – in the shape of crime and social incongruities, environmental problems, natural disasters, and so on – and in promoting the conditions for an ever better future. Another, equally important task for the media is to examine and report on unsatisfactory situations – not primarily to the public, but to those in control (Cheung 2001). Therefore, the media in China are a poor forum for

discussion and dialogue, even about completely uncontroversial subjects (Samuelsson 2000). Since climate policy has a clear foreign policy aspect, the media can in principle adopt no other positions than the official ones (Cheung 2001). Media’s capacity to penetrate, however, naturally makes them an excellent organ for education and propaganda. The spreading of increased awareness in the population about sustainability and the environment – including climate – is a strategy, the importance of which is recognised by the leadership. Such education is seen as a significant means for countering environmental threats to continued social progression (Economy 2003). Media attention is therefore increasingly being devoted also to the climate issue: primarily to its scientific aspects of course, but domestic climate aspects favourable to the leadership’s agenda can also be highlighted (as for example, reports and comments on China’s falling energy intensity in the 1980s and 1990s). A sign of the deliberate use of such a media-driven public education effort on climate is the national

broadcasting company CCTV’s plans to increase its existing range of television channels with an additional one, whose programming schedule would be dedicated to climate-related

programmes and items (Chen 2004).

In addition to the media, schools and academic institutions are naturally very important as institutions for the dissemination of knowledge (Liu 1991), but, as mentioned above, the climate policy dimension is limited to a few institutions in Beijing. Efforts to extend

educational measures about the scientific aspects of climate change ought not to be politically controversial. However, a great deal of inertia in curricula, course schedules and the teaching profession would have to be overcome.

In summary, journalists, teachers and similar professional categories need to be included as key actor groups in an overview of the Chinese climate arena.

5.4.2 Non-governmental organisations

China has no freedom of association. Non-profit associations and other non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have to register with the Ministry of Civil Affairs (MCA) or its local counterparts. Exceptions to this rule are made for associations, which belong to a selection of defined categories, or which are classed as departments of already existing institutions, organisations or companies. In consequence, many associations work under an umbrella such as a university. Organisations initiated by the authorities do not need to be registered, which has given rise to the acronym GONGO (government-organised non-governmental

organisation). These organisations may function as think tanks with considerable influence. For ordinary associations, however, the registration requirement and the subsequent influence of authorities over their activities can significantly affect their manoeuvring space. Still, in 2001, over 200 000 associations were registered with the MCA, and the number rises steadily. There are also estimates that indicate that the number of unregistered associations in China might be as high as one and a half to two million (ESTH 2003a).

In many cases, NGOs can work without much interference from, or even in co-operation with, the authorities. This applies in particular to those that are dedicated to non-controversial topics such as environmental (science) or health education, care of the disabled, etc. Among