Smartwatches in the elderly care

A design intervention approach

Marianne Bansell

Interaction design

Bachelor 22.5HP VT/2018 Student id: LL031129 E-mail: marianne.bansell@live.se Supervisor: Jens PedersenAbstract

This thesis project is exploring future smartwatch use within elderly care. The user-centered designing phase uses a design intervention approach, where design and research happen simultaneously.

The research question is: “How can a smartwatch be used within the elderly

care, based on the existing TES mobile phone app, and how can these interactions be designed as smartwatch features?”. The results are four

iteratively explored design opportunities, presented as design propositions with concept sketches, and two prototypes.

The main participants in the field studies and workshops are end-users, caregivers within the elderly home care and an elderly care center. The outcome shows they are positive towards an imagined future containing smartwatches as a work tool. They see advantages with the wearable and glanceable technology, like freed hands, less to carry and simpler interactions in comparison to a smart phone.

The study also shows positive effects of using interaction design for a company’s design process, and exploration of new technology.

Table of contents

1 Introduction ... 1

1.1 Problem/topic ... 1

1.2 Motivation ... 1

1.3 Ethics ... 2

1.4 Reading the thesis ... 2

2 Background ... 2

2.1 Tunstall and TES ... 3

2.2 Elderly care in Sweden ... 5

2.3 Smartwatches ... 6

3 Methodology ... 8

3.1 Two phases’ design processes ... 9

3.2 Desktop methods ... 11

3.3 Field studies ... 13

3.4 Dialogism and presentation ... 17

4 Research phase ... 18

4.1 Getting to know the context and conditions ... 18

4.2 Identifying design opportunities ... 24

5 Designing phase ... 26

5.1 Sketch iteration ... 27

5.2 Prototyping #1: on a smartwatch ... 30

5.3 Prototyping #2 and rounding off ... 33

6 Reflections on the process ...34

6.1 Approaching design activities ... 35

6.2 About field studies ... 37

6.3 An ethical dilemma ... 39

7 Discussion ... 40

7.1 What are the outcomes? ... 40

7.2 Conclusion ... 43

8 References ... 44

9 Appendix ... 49

9.1 Attachment I: Smartwatches ... 49

9.2 Attachment II: What to look for? ... 51

9.3 Attachment III: Observation Insight D.O. ... 53

9.4 Attachment IV: Presentation “So far” – an example ... 55

Acknowledgements

Thanks to…Harakärrsgården C-F, and Ewa Wörlén, for sharing your work environment and methods, ideas, thoughts and participating in workshops. And a special thanks to Julia Sjövall in division F for your heartfelt dedication to my thesis project.

All caregivers in Hemtjänsten area west in Klippan, for sharing your work environment and methods, ideas, thoughts and participating in workshops. And a special thanks to Raida Johansson, who has helped making all this possible.

Jens Pedersen at Malmö University, who guided me to look at my design process in a different way; challenged me – which was irritating at the moment, but appreciated and educational/developing/enriching for me as an interaction designer and the thesis’s turnout.

Johan Frogner at Tunstall, for helping me find a good thesis project, showing genuine interest and providing relevant feedback.

Basil Talozi, and the TES app-team, for showing real interest in my thesis project and its results in the middle of their own busy work. And for giving support, ideas and feedback, and participating in presentations, discussions and co-design. And of course for providing a fun work environment with good lunches.

Marie Larneby, Ida Berg, Angelica Gillbjörn, Robert Bansell, Helena Olsson, and Lennart Malmquist for ideas, discussions and listening ears.

1 Introduction

This thesis project is a cooperation with the company Tunstall, which develop technology for the elderly care. I explore possible future use for smartwatches within the elderly care, by exploring design opportunities and prototyping smartwatch features to complement Tunstall’s existing mobile phone app called TES.

1.1 Problem/topic

The market for wearables is growing fast. And the smartwatches we can find today are very capable. For example, on some you can make phone calls and on some you can pay when you are at the store. Other features can include keeping track of your health or checking e-mails. How can you use all this technology and capability, and is the glanceable design working the way it is intended with positive user experiences and beneficial value?

The aim of this project is to explore how a smartwatch can complement a mobile phone app in the context of healthcare and provide usability for the target group caregivers. And why you would use a smartwatch when you have a mobile phone? This project is based on constructive design research, which means a process of combined research and design.

1.1.1 Research question

“How can a smartwatch be used within the elderly care,

based on the existing TES mobile phone app, and how can

these interactions be designed as smartwatch features?”

1.2 Motivation

1.2.1 Why work with Tunstall?

Before I chose to become an interaction designer I was a teacher, and I love working with helping people. During my interaction design education, I have developed an interest in digital health (see Bansell, 2016), which makes Tunstall a very interesting company. Tunstall is a company that produces technical solutions to help elderly or disabled people, their relatives and caregivers. So for me to get the chance to do my thesis project with a company like this, is a great opportunity and match.

1.2.2 Why smartwatch and the TES-app?

During my education I niched myself by learning how to develop mobile phone apps, and I have also taken an interest to glanceable technology (see Bansell, 2016), which has tickled my curiosity about smartwatches.

So during my thesis project I wanted to combine my interests into one project by designing smartwatch features for Tunstall, and they chose the TES-app.

1.3 Ethics

This project follows the ethical considerations described by the Swedish Research Council in “Good research practice” (Vetenskapsrådet, 2017). All participants have been informed about the project, what it is about and who they are cooperating with; that participation is voluntary and that you can quit whenever you like. All participants have given their oral consent to both participation and the documentation of their activities in the forms of notes and photos. Considerations have been made according to the elderlies’ exposed conditions, while given care for sometimes intimate situations, and especially to those suffering from dementia, who cannot be counted as mentally liable.

1.4 Reading the thesis

After this introduction, the design context’s three main areas are described in the second chapter. There you can read about Tunstall and TES; the Swedish elderly care; and designing for and the development of smartwatches, including related work.

The third chapter is about the methodology used for this thesis, and how I started out using the double diamond process and changed into a design intervention approach.

In chapter four you can see the results from the initial research phase, that landed in four design opportunities with early concept sketches.

And in the fifth chapter the iterative design intervention activities with their results are presented.

Chapter six is a reflection on the process; and in chapter seven you can find the discussion of the results, and the conclusion.

2 Background

In this chapter I present the project’s design context, divided into three main areas. Firstly, there is a description of Tunstall, what TES is, and the alternative products and services on the market. Secondly, you can find an

overview of the elderly care in Sweden. And thirdly, I talk about what it means to be designing for smartwatches, and what research on smartwatch use within elderly care says.

2.1 Tunstall and TES

2.1.1 Tunstall company

Tunstall is a company designing technology for healthcare, with focus on the elderly and the elderly care. The aim is to give people the opportunity to live at home and have a fulfilling life for as long as possible, by the help of Tunstall’s technology and the caregivers. Tunstall is a global company originating in Great Britain, and today present in 30 countries, with about 1800 employees. More than 2,5 million caretakers use their products. The TES-app is developed in Malmö, Sweden. Tunstall in Malmö was originally Svenska Trygghetstelefoner, which was bought by Tunstall.

Tunstall has a variety of products and services, but no wearable smartwatch app, so this project breaks new ground and explores the possibilities of wearable technology in a new way. Tunstall is curious about experimenting with new technology and runs health case studies in several countries. (Tunstall.se and Tunstall.com, 2018, January 18)

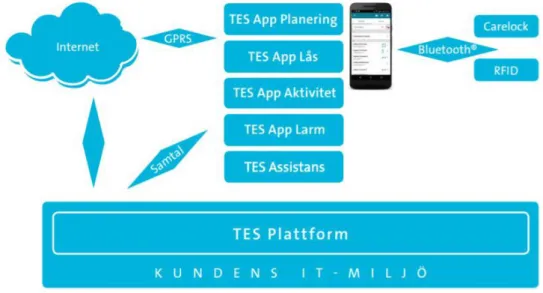

2.1.2 The TES-app

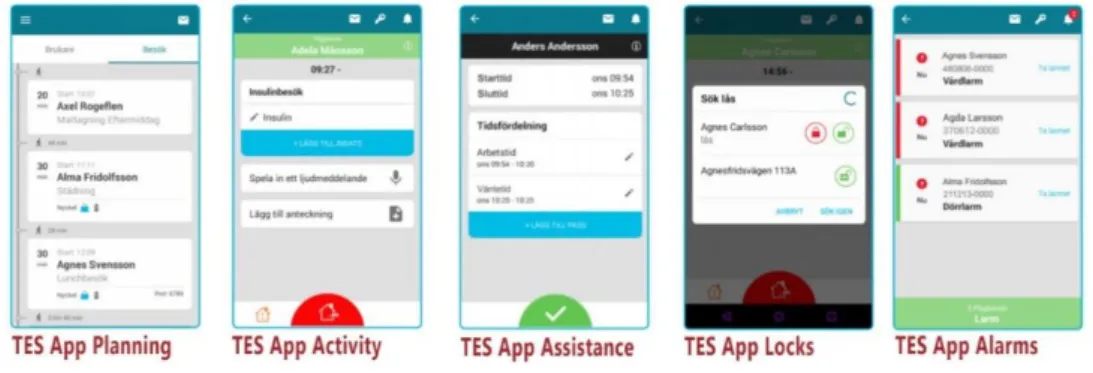

TES is an abbreviation for Trygghet (security), Enkelhet (simplicity), and Säkerhet (safety). TES is a collection of services provided by Tunstall (see figure 1). The TES-app is an app aiming to create safety and security, and make the administrative work easier and faster, within the elderly care. Today it includes: Alarms from patients, Planning of caregivers’ home visits, Activity logging, Locks with digital keys/smart locks, and Assistance for planning

work hours (see figure 2). The target group is caregivers who can use the app to plan the elderly care with schedules and forms to the authorities, lock and unlock the caretakers’ doors and handle alarms from caretakers. Each customer can choose to adopt a few or just one, or all of the service package’s parts.

For the entire TES-app there is a tight security since the elderlies’ personal and health information is being handled, as well as addresses and locks. RFID is one technique used, and you can also remotely delete all information from a mobile phone in case it is misplaced or lost. The TES-app also includes an assault alarm for the caregivers. The TES-app is being used within the Swedish elderly care in several municipalities.

(Tunstall, 2018, January 18)

2.1.3 Tunstall’s competition

Tunstall has four major competitors. Everon has an alarm watch (see figure 3) aimed for elderlies who suffer from dementia. The watch has GPS and can be locked onto the user’s wrist, to ensure that the user cannot take it off. The watch includes a phone which enables a two-way communication, and an alarm button on the side of the watch. Everon also has a digital wireless surveillance system aimed for care centers. In addition, Everon offers systems to manage locks. (Everon, 2018, April 17) 9Solutions is the next competitor, which offers a combination of systems for hospitals, care centers and home care, to allow communication between different stakeholders. They have alarm buttons with positioning, including the possibility to automatically unlock doors,

and the possibilities to program safe geographical areas for the user. The buttons can be combined with smart sensors. For the home care they have care phones connected to smartphones. (9Solutions, 2018, April 17)

SmartCare by Doro, the third competitor, is a cloud based holistic service intended for elderlies living at home assisted by relatives or the elderly home

Figure 2. Screenshots of the five different TES-apps.

Figure 3. Everon's alarm watch (Everon, 2018).

care. Doro offers a set of sensors connected to a hub placed in the home, that connects to the cloud. (Doro, 2018, April 17)

The final competitor mentioned here is Neat. They also produce safety phone systems with alarm button bracelets, and door alarms connected to positioning for people with dementia, intended for the elderly home care. They have a communicating system connected to a variety of sensors. (Neat, 2018, April 17)

2.1.4 Thesis project with Tunstall

For this thesis project I have been working with the Tunstall TES app developer-team, with two supervisors at Tunstall. Basil Talozi is product owner for the TES app, and Johan Frogner is Tunstall’s Development Director for Northern Europe. With Basil I have had most regular contact regarding the iterative process and hands-on questions, but Johan helped choosing the thesis topic and evaluate the quality of the results and putting them into perspective.

Now you have read about Tunstall in regards to the thesis topic. The next area to learn about to set the context is the elderly care.

2.2 Elderly care in Sweden

Elderly care is the designing environment for this project. Focus is placed on how technology can be of help to the caregivers.

Historically we have looked at the composition of the population and called it a population pyramid. The reason is that it has looked like a pyramid, with the more people alive the younger they are. But that has changed. We live longer now and the population pyramid looks more like a tower (see figure 4). Sweden faces the issue of how to take care of its elderlies. The elderly care employs the most people in Sweden. Almost 140 000 persons work either at elderly care centers or with home care. At the same time all reports for the past couple of years and the prognosis for the future say that there is and will continue to be, a lack of educated caregivers. (SCB, 2018, April 25)

2.2.1 Elderly home care

The elderly home care in Sweden is organized by the municipalities. Sometimes they employ caregivers, and sometimes buy the service from a private company. (Wikipedia Hemtjänst, 2018, April 25) But either way the idea is that the elderly person lives at home and caregivers come to her home, as often as needed, based on an investigation handled by the municipality.

Figure 4. Sweden's population pyramids 1900 and 2017 (SCB, 2018, April 25).

2.2.2 Elderly care center

The percentage of elderly people in Sweden living at care centers has decreased, with more people living at home with assistance from relatives and the elderly home care. (Wikipedia Äldreboende, 2018, April 25)

And now I will talk about a possible future work tool technology, smartwatches.

2.3 Smartwatches

The third area to discuss to set the thesis context is smartwatches. To design for smartwatches means you are designing for a quite unexplored new growing technology, which most people do not yet use unlike mobile phones. The screens are much smaller, and the device is attached to your body; two facts that affect the interaction designing.

2.3.1 Smartwatches today

According to Forbes (Lamkin, 2017) the smartwatch sales will double in the next five years, due to the critical mass’s adoption, or that the early majority (Interaction Design Foundation, 2017) starts buying. This means that even if sales has not grown as quickly as firstly predicted in the beginning of the millennium, designing for smartwatches will increase as a design space, and a lot more companies will need to adopt their products and services for smartwatch-usage. How people use smartwatches are often in tandem with other devices, for example mobile phones, which opens up for cross-device app design (Houben and Marquardt, 2015). This way of using a combination of several wearable screens as an interactive display ecosystem (Grubert et al, 2015) enables new design opportunities and challenges.

The smartwatch variety in stores is developing significantly. But considering the target group for this study consists of over 90% women, it is an interesting fact that it is still hard to find a watch that has both advanced technical affordances, as WiFi, Bluetooth, NFC, heartrate sensor, microphone etcetera, and a feminine design (see Attachment I).

Used as a work tool the smartwatch shows potential. Already research has shown how smartwatch-use can augment interactions in office work, for example by locking and unlocking doors (Bernaerts et al, 2014). And Apple say they have learned some vital UX-lessons from their first generation of smartwatches (Interaction Design Foundation, 2017). These lessons are basically: apps need to be developed for smartwatches specifically, but must be holistic and co-work with other devices; think glanceable by increasing speed because users interact with their watches for about two seconds at a time, so you need to be direct and reduce interaction to a couple of taps. So glances and notifications are the key foundation, but what does glanceable mean?

2.3.2 Glanceable

Glanceable means to understand something at a glance or repeated glances over time, using minimal attention (Glanceable, 2017). Glanceability, understood as peripheral displays (Matthews, 2006), can be a tool to show multiple kinds of information in an efficient way without stressing the user by interrupting his or her ongoing main task (Bansell, 2016). If a smartwatch app is designed right it could, using glanceable feedback (Goveia et al, 2016), help the user achieve his or her main goal while still sifting through other information. The designer wants to find the sweet spot which allows the user combining easy interpretation and fast perception (Matthews, 2006). Normally a user interacts with a smartwatch for two seconds at a time. (Interaction Design Foundation, 2017).

A smartwatch combines the smart functionalities of a smartphone with the glanceable affordances of a classic wristwatch. Google calls their smartwatch apps “wear apps”. But what does the term wearable mean?

2.3.3 Wearable technology

Wearable technology means technology that you can wear on your body. Its history can date back to the 16th century with an abacus as a necklace, or the

first wristwatch made for the queen of Naples in 1810 (Wearable computer, 2018). But the modern meaning of the words wearable technology is “a user-programmable item for complex algorithms, interfacing, and data management” (Wearable computer, 2018, January 29).

In this paper wearable refers to smartwatches that are attached to your body. Smartwatches started out as mobile phones in the form of wristwatches in the 2000s, and in the 2010s Sony released a wristwatch that needed to be paired with an Android phone (Wearable computer, 2018, January 29).

2.3.4 Developing conditions

So to develop for smartwatches has it similarities and differences to developing for smartphones. Different smartwatches use different operating systems. The most common ones are Wear OS by Google, formerly known as Android Wear but changed names in March 2018; iOS for Apple; and Tizen for Samsung. During this project Wear OS by Google is used in Android Studio, where you program in Java. Tizen Studio looks like Android Studio but you can choose to make your app in JavaScript/HTML/CSS or native in C. The different OSs mean a designer need to check which OS each watch runs on before buying it. (Tizen Developers, 2018, January 18 and Android Developers, 2018, January 18) Every watch also has different technical affordances, like WiFi, NFC, microphone, heartrate sensor etcetera. You need to do an inventory of which you need, because that will affect which watch you can buy.

Once you have a watch, you can choose to design either standalone apps that work independently of a phone, or apps that co-work with an app on a smartphone. (Android Developers, 2018, January 18)

An Android app user is supposed to recognize herself in how the wear app looks, feels and behaves. This means designers need to follow a set of design guidelines, like Google’s App Quality Guidelines which is about designing the user experience. The goal is to design smooth glanceable experiences which leaves the user and the user’s hands free for other tasks (Android Developers, 2018, April 17 and Google, 2018, April 13).

2.3.5 Academic research on smartwatches within elderly care

One research project has proved advantages of using smartwatches within the elderly care, in regards to response times. Ali and Li (2016) showed how a communication system using smartwatches in a nursing home instead of a regular lights and sounds system, could improve communications and thereby prevent fall accidents. They iterated on smartwatch prototypes with user-testing and found that the response time to alarms was reduced when the nursing home used their system instead of the regular one. When the nurses wore the watch they could immediately feel, hear and see the alarm, with more information regarding what the alarm was about, compared to an alarm system with lamps and speakers. The staff was very positive toward future use of a smartwatch system. And even though that buying watches for all staff would mean increased costs for the nursing homes, Ali and Li (2016) predict that the benefits will be worth it to the nursing home managers. But Ali and Li compared a wearable system to a wall mounted system, not smartwatch use to smartphone use, which Stisen et al (2014) did. Stisen et al looked at a smartphone versus a smartwatch versus a smartphone mounted on the forearm, and found that the wearable computers had several advantages, for example glanceability, over the handheld device. That study’s domain was a hospital with orderlies (not nurses) as their users.

Chapter 2 has set the thesis project’s design context, divided into three main areas: Tunstall and TES; the elderly care in Sweden; and what it means to be designing for smartwatches. Next chapter is about the methodology used during this project, and how the design process guided the methodological choices.

3 Methodology

In this chapter you can read about the project’s methodological choices. First It describes how and why I started out with the double diamond process for an initial research phase, and continued with a design intervention approach for the designing phase. Next the chapter talks about methods used, divided

into desktop methods and field studies. Lastly, dialogism and presentations are discussed.

3.1 Two phases’ design processes

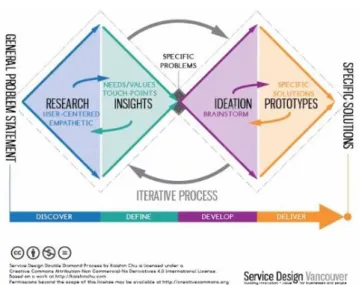

At the beginning of this project theidea was to divide the work process into two clearly defined phases. Phase one was to consist of research with literature studies and user research. The goal was to map the existing TES service used in its environment, and to learn about the users, their inner goals, their work, and what affects the TES’s usage situation. Finally, I was supposed to find which features in the TES I would design smartwatch features for. Phase two was to consist of designing and coding these

smartwatch features and user-testing them in an iterative manner. The idea was to follow the double diamond design process, where research leads to insights in an iterative process, then you identify your design space or specific design problem. After that you ideate on the problem and start prototyping (see figure 5). And in the beginning of this project I followed my plan with a research phase (see chapter 4) which resulted in four design opportunities with early concept sketches.

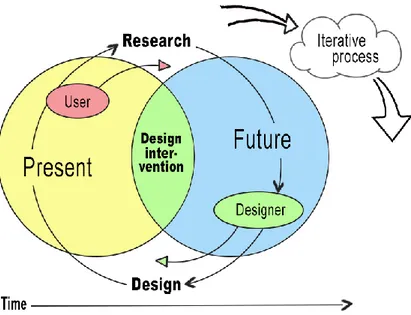

But the research had a double focus: to learn about elderly care and how it is to work within elderly care; and to learn about TES, its different parts and how you work with TES in real life. When I started seeing the users, since the focus did not just lay on learning about their job, environment and habits, but also on the TES app, and the fact that they also knew that I was supposed to do something involving the TES app and a smartwatch, that colored the discussions and topics early on. And soon the design process started. Me just being there, in the users’ environment, introduced the idea of a different possible future, which affected their thinking and reflecting on their present work. The future collided with the present, and the discussions about the present were mixed up with ideation about future possibilities. So the thesis’ topic and the effects my presence in the environment had, mixed by the project’s limited timeline, led to the designing phase starting quite early. Perhaps my inexperience as an interaction designer, and my wishes to accomplish concrete results both for my thesis and for Tunstall, contributed too. I grabbed the opportunity to catch all these ideas about the future grounded in the users’ knowledge about their work environment, and started designing while researching. That meant I tweaked my design process, from the two clearly separated phases with research about the present and then

designing for the future, into a blurrier version of the designing phase, where research and designing activities enriched each other. This next design process used in the designing phase (see chapter 5) can be described as a design intervention approach (see figure 6). In design intervention you do not draw a clear line between researching the present and designing for the future. This method is especially useful when you are exploring new ideas that are vague since they do not yet exist as neither a concept nor a specified physical manifestation. Halse and Boffi (2014, p. 1) define this design process as:

“… design interventions can be seen

as a form of inquiry that is particularly relevant for investigating phenomena that are not very coherent, barely possible, almost unthinkable, and totally underspecified because they are still in the process of being conceptually and physically articulated.”

Since this project is about exploring a possible future use of smartwatches within the elderly care this project fits the description above. The smartwatch represents a technology that is entirely new to both the users and their work environment. That means the users do not have any experience of what a smartwatch can or cannot do. And design interventions are a good way to “enable new forms of experience, dialogue and awareness…” (Halse and Boffi, 2014, p. 2). That also means every time I as a designer have visited my users, the elderly home care in Klippan or the elderly care center in Burlöv, I have represented a possible new future, and all our different activities have been colored and influenced by possible future scenarios. But in the same time, all these different activities, including for example user-testing varying prototypes, have deepened my understanding of their situation and thoughts about their job and so on. Because when they interact with the watch, or discuss concept sketches, they comment on them connected to their present situation, and by this informing me about the present, while giving feedback on the design, while ideating on other possible future scenarios. This constructive mix is why a design intervention approach is suitable as a design process for the designing phase. If I had slowed down the process and stayed longer in the research phase I would perhaps have found more design opportunities, but the circumstances led me to start designing early on.

Figure 6. An illustration of my interpretation of this project’s design intervention process. The future is brought into the user’s present by the designer. And the user informs the designer on both present and future levels while discussing the design. Thus designing and research are happening at the same time, in an iterative process.

This simultaneous ongoing design and research, researching while designing, is also called constructive design research. Constructive design research, according to (Koskinen et al, 2011, p. 5), “refers to design research in which

construction – be it product, system space, or media – takes center place and becomes the key means in constructing knowledge”. And that sums up

what this project’s designing phase is about. While designing, for example either paper sketches or a digital sketch in a smartwatch, and discussing these artefacts with users, new knowledge about the present as well as the future was produced.

Now I have established how the design process was altered according to the project’s two phases, with the double diamond design process in the beginning, followed by design interventions. Next I will describe with which methods the research and designing was done.

3.2 Desktop methods

When I write desktop methods, I mean methods used by me as a designer, without users’ direct involvement, performed outside their environment.

3.2.1 Literature studies

Before I even contacted users, I had to learn about both the TES app and the fields of smartwatches and elderly care in Sweden. So I started to read, mainly on the internet since the field of smartwatches is still young and rapidly evolving. So a lot of articles, academic papers as well as news articles and other publications and writings, and films on internet, has been processed, to get a sense of what has been done and explored and where the development is at right now and where the smartwatch interaction seems to be heading. Some of it has already been mentioned in this paper (see chapter 2) and some has just been the grounds for general knowledge and grounding point. Literature studies were also used while sketching, both on paper and digitally, to inform the design decisions, based on design guidelines. I will return to this during chapter 5.

3.2.2 From Observation – to Insight – to Design Opportunity

During the research phase, to find the design opportunities for this project, I started out identifying problems or issues, based on observations during a-day-in-the-life-sessions in Klippan and in Burlöv. I used photo-collages from the visits, together with my notes, to help me see what I had noticed in the moment. Observations are a description of something that exists today, and a problem or need represents something that is not there (Pedersen, 2018). The problems I then re-formulated into something that is generative for design solutions and points out a design direction. Those formulations became the project’s design opportunities. How this looks like for the alarms’ design opportunity can be seen in figure 7. I did the same process to find the other design opportunities (see Attachment III), and then analyzed which

design opportunities were workable within the project’s scope. On each design opportunity I brainstormed and synthesized the brainstorming into a couple of ideas per area. The interesting ideas laid ground for my first iteration of sketches.

3.2.3 Sketching

In an article about sketching as a tool, based on two books written by Bill Buxton and his colleagues, Interaction design foundation (2018, May 5) writes:

“Sketching is a distinctive form of drawing which we designers use to

propose, explore, refine and communicate our ideas. As a UX designer, you too can use sketching as your first line of attack to crack a design

problem.”

For this project the original idea was to use sketching like that, as an initial tool for communication before the coding began. But sketching played a bigger part in the design process than originally intended. When I changed direction into explorative designing, the tasks changed and therefore the methods. I chose to spend more time and focus on sketch-iterations and workshops.

Sketches are in this project used to help the users imagine and experience a possible future scenario in its environment. But sketching was also used for my own understanding of the material,

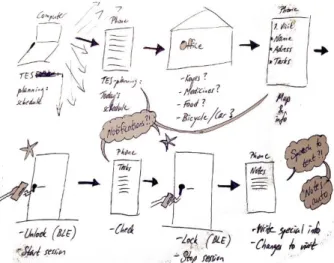

by physically enabling me to see findings and ideas (see Attachment V). For example, when I quickly sketched out a user journey (see figure 8). So what kind of sketches have been done during the project? I did a flow-analysis (IDEO, 2003) to learn how the information and communication flow between Tunstall and Klippan’s elderly home care looked like. By sketching this out it was possible to identify bottlenecks and why the communication did not work as well as

Figure 7. An example of how an observation is transformed into a design opportunity.

Figure 8. Early user-journey with design spaces ideas, regarding TES planning and locks.

all parties hoped. That sketch led to one of the project’s design opportunities (see Attachment III). Other sketches are the early concept sketches, and the second and third iterations of sketches (see chapter 5), and quick-sketches made during workshops to illustrate what was said.

I have now talked about desktop methods, divided into three parts. You have read about literature studies, turning observations into design opportunities, and sketching. Let us now move from the designer’s desk into the users’ world.

3.3 Field studies

The field studies in this project have consisted of three main methods: interviews, a-day-in-the-life-observations, and workshops. They have a sub-section each in this chapter. But first I will discuss the field studies on a general level, regarding a holistic view and the choice of users for the project. During each session in this project that includes any stakeholders, photos and written notes have been taken. These notes and photos are not a complete record of what has been happening but they trigger memory of what was going on, and help the interpretation and processing of the event (Blomberg, 1993). And during the field studies a holistic view is used, to look at, as Blomberg (1993, p. 125) puts it, “how particular behaviors fit into the larger whole”. So to explore a possible new future, with new work methods, I needed to look at the whole picture critically: Is this new piece of technology useful; and if it is, how and where?

This study is based primarily on a user-centered design approach, which means I have mainly focused on the users during the explorations of the thesis’s topic. The reason is that if I am to explore how a smartwatch can be used within the elderly care, I need to look at the caregivers. The term user-centered design is used according to Abras et al’s (2004, p. 445) definition: “‘User-centered design’ (UCD) is a broad term to describe design processes

in which end-users influence how a design takes shape.”. At first, the plan was to use only Klippan’s elderly home care as users for this project. But they only used parts of the TES app series. At first I thought that would be enough. But after discussing the project with the TES app-team, I decided to contact Harakärrsgården in Burlöv as well, because they use other parts of TES. This contact proved to be fruitful in providing a more complete overview of how the TES app is used and its users. Both target groups, the home care and a care center, are equally interesting if you are to design holistically for TES users.

3.3.1 Semi-structured interviews

The first method used in my field studies was interviews. I started out by interviewing the TES app product owner/developer and after that the managers at, firstly Klippan’s elderly home care and later on the elderly care center in Burlöv. Those interviews helped bring a helicopter view of the

system, to have something to relate to, both regarding the app in focus and the elderly care, later on during the a-day-in-the-life observations (see next sub section) with caregivers. For this reason, the interviews in this study are semi-structured, meaning that there are for each interview a couple of themes or topics to be covered, but not a fixed set of formulated sequenced questions. The interviews are quite similar to narrative interviews, where the interviewee tell a story, and the interviewer mainly listens and helps the teller to keep focus or confirm the understanding of the story, the interviewee’s life’s story. And since it was the “work-life-stories” I needed, the methodological choice of semi-structured interviews suited.

The feeling of the interview is very important for when you are to interpret it later on: What was it that was said that was really important? How you know what is important is often understood by how the interviewee says it, with voice, facial expression and body language. Therefor it is important to take notes on such things as well, and perhaps underline especially interesting citations (Blomberg, 1993 and Kvale, 2008). Kvale (2008, p. 56) writes

“Much is to be learned from journalists and novelists about how to use

questions and replies to also convey the setting and mood of a conversation.” And my experience as a journalist colors the interviews and interpretations when I for example, find “the story”. Spradley formulates what is my aim with this project’s interviews (as cited in Kvale, 2008, chapter 5, p. 2):

“I want to understand the world from your point of view. I want to know

what you know in the way you know it. I want to understand the meaning of your experience, to walk in your shoes, to feel things as you feel them, to explain things as you explain them. Will you become my teacher and help me understand?”

To sum it up, interviews in this project are with the Tunstall TES app developer/product owner and the managers in Klippan and Burlöv. But also several other stakeholders have been interviewed during other activities which have included interviewing, like participating in an a-day-in-the-life where the interview becomes a contextual interview (Blomberg, 1993); any kind of workshop; observations while working at the Tunstall office; or attending meetings.

3.3.2 A-day-in-the-life

The next field study method to discuss is the a-day-in-the-life observation. To get the understanding of the users and their environment, and to map the usage of the existing TES app service, I did two a-day-in-the-life (IDEO, 2003) observations which included interviews, at an early stage in the design process, at Klippan’s elderly home care. A bit later in the process I did another two at the elderly care center in Burlöv. And I also complemented with a final a-day-in-the-life with interviews in Klippan at a late stage in the design process (see figure 11, last in this chapter), to ground my findings and

conclusions in real life. To document each session photographs and note-taking were used.

The point of a-day-in-the-life is to see what is really happening where and when it is happening, rather than to just let people tell what is happening. Because what people say they do, and what they really do can often differ, like in the alarms situation in Klippan (see chapter 4.1.5). So by following the users while they do their routines is a good way to find issues that would perhaps otherwise go unnoticed. (IDEO, 2003)

As well as caregivers’ workdays at one elderly care center and one division of elderly home care, a team leader’s planning with TES on a computer was observed. Also an area managers’ meeting between several elderly home care divisions has been observed.

3.3.3 Workshop/ideation

This project’s final field work method is the workshop. To get feedback from the users on sketches and prototypes, both to confirm I had understood correctly and based my designs on correct observations and interpretations, and to ideate on future designs, I held workshops. During the workshops the discussions were based in the users’ current work situation, all according to the project’s constructive design research approach. Pedersen (2007, p. 69) describes that kind of collaboration-style workshop as:

“The purpose of the workshop was basically – in the tradition of

participatory design – to collaboratively explore and envision […] based in the episodes described in the previous chapter and in the participants’ experiences of work and technology.”

The results from workshops at one stage led to a new iteration of sketching or prototyping, and then new workshops (see chapter 5). The decision to involve the users enabled them to look at and reflect upon my designs in their environment.

So how were the different workshops conducted? Each workshop consisted of two to three participants, where passers-by joined out of curiosity. The first workshop was a prop-workshop regarding possible placements of a smartwatch. It was the only workshop conducted during the research phase, and was a direct result, almost a reaction, to a finding that caregivers are not allowed to wear anything below the elbows, which was a bit of a shock, and almost led me to question the entire topic. But after some consideration and discussions with the users, I planned the prop-workshop with bodystorming to ideate on possible placements for a smartwatch. Bodystorming where you act out roles,

that are behavior- and context-based (IDEO, 2003), and the users tried out placements while acting out their caregiving job. The participants, mainly one person but more joined out of curiosity, played with the props (see figure 9) and together we came up with a set of possible placements. And then the thesis topic was back on track.

The workshop/ideation on the four early concept sketches was divided into different workshops to separate the caregivers (see figure 10) and the area manager. The intention was to enable free discussions. Too see the questions I had to the workshop, see Attachment II.

During the two sketch-based workshops the activities can be described as scenario testing, where the participants, two to three persons per establishment, were faced with a possible future scenario and could then share their thoughts and reactions. This method is particularly suitable for testing a new concept, according to IDEO (2003, Scenarios-card); they write that a scenario “... helps to communicate and test the essence of a design idea

within its probable context of use.” The sketches were laid out on a table in

front of the users, explained by me, and then I was silent and let the users speak freely. My only questions were either guiding or questions to check my understanding of their stories (see chapter 3.3.1). At first I invited the participants to write and sketch with pen and paper, with the only result being scribbles. So I took notes and sketched what they said.

Shorter simpler workshops during this project are: quick-testing with two 60+ year-olds with focus on eyesight, to get feedback on readability on the smartwatch; and with the Tunstall TES product owner to get feedback connected to the existing TES app, during the digital sketching (see chapter 5). I chose non-users, but in the right target group for the eyesight-test, to be able to do quick iterations and testing, while designing watch user interfaces. And when I tested with Tunstall, I did quick sketches and took notes to catch the feedback and discussions.

Just for fun, and to see what it could generate, a co-design session was conducted in Burlöv with two-three caregivers, depending on how you count passers-by who got engaged, at the elderly care center and two Tunstall developers. During that session it was the first iteration of digital sketching/prototyping that was focus. Also a short design intervention workshop was conducted with Klippan’s four area mangers, where I used narrative scenarios to start up the discussions with a smartwatch as prop. The aim for that workshop was to explore how the managers experienced a possible use of smartwatches for the caregivers.

You have now read about the three methods used during field studies: interviews; a-day-in-the-life-obervations; and workshops. Next I will discuss how regular presentations have helped drive the project’s design process.

3.4 Dialogism and presentation

As the last part of the methodology-chapter, I will talk about the importance of communicating design ideas. Regular presentations in different forms have helped drive and shape this project’s design process as an ongoing design dialogue (see Attachment IV for an example). To clarify the findings and the process to me as well as the stakeholders, I have throughout this project, worked according to the principles of Mikhail Bakhtin’s dialogism, with the interpretation that every time you say or write something you enter into a dialogue with other people (Malmbjer, 2017). The positive effects of preparing and holding presentations are that you are forced to filter your own quite extensive knowledge and choose what to tell and show and how to communicate what you are thinking (Presentationsteknik, 2018). That filtering process through communication with different stakeholders has driven the design process steadily forward by forcing me to capture where I am, connecting to where I left off, and showing what is coming next in my design process. How this learning dialogue process has developed through this thesis project can be seen concretized by reading about the research and designing phases in the next two chapters, 4 and 5. In this third chapter, I have described how and why I started out with the double diamond process, and continued with a design intervention approach. I have

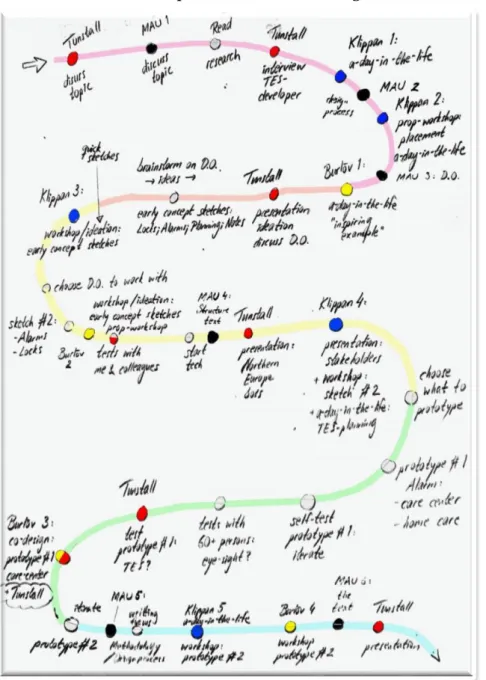

Figure 11. Illustration of the project’s design activities chronologically. The pink line corresponds to chapter 4.1; orange to 4.2; yellow to 5.1; green to 5.2; and blue to 5.3. Red dots represent Tunstall activities; blue dots are Klippan; yellow dots are Burlöv and black dots represent supervision at the university.

also described desktop and field work methods, and finally how presentations have contributed to the process. To get an overview of all activities conducted in this project, see figure 11.

4 Research phase

In this chapter the results from the project’s first phase of the design process, the research phase, are described. It was during this phase the classic double diamond process was followed (see chapter 3.1). The research phase resulted in defining four design opportunities, presented lastly in this chapter as early concept sketches.

The first part of the chapter describes what I initially found out about the design context, regarding the three project main areas: smartwatches, TES and the elderly care. The second part describes how the design opportunities were identified and defined.

4.1 Getting to know the context and conditions

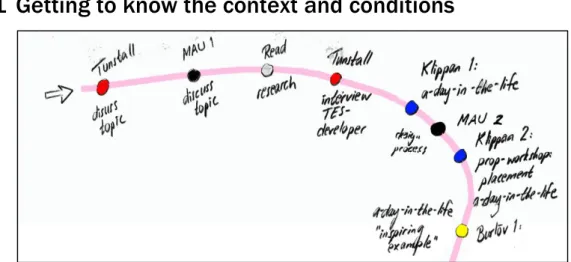

Figure 12. This chapter's activities. To get an overview of the project activities, see figure 11, where this chapter is represented by the pink line.

Now I am going to present, in short, what I learned during my initial research about the design context and conditions. The results are divided according to the three main areas: smartwatches, to know what the conditions are for designing for that platform; Tunstall’s TES, whose app the project builds upon; and the elderly care, since the target group is caregivers within elderly care. The elderly care is described by both the elderly home care in Klippan, and an elderly care center in Burlöv. To see which activities this phase included, see figure 12.

In this chapter you will also read more about how the process moved on from the setback from the finding that the caregivers are not allowed to wear anything beneath their elbows.

4.1.1 Research on smartwatches

There is a variety of research done on how to design for smartwatches, both regarding smartwatches as wearable technology and the design of smartwatch interfaces. And an academic project done at Binghamton university (Ali & Lee, 2016) combined smartwatches with caregivers at a nursing home as a work tool, with promising results regarding response time to alarms. For more information, see chapter 2.3.

If you are designing for smartwatches, you cannot design for just any smartwatch. If you are to test your design on a watch, you need to know your code match the watch OS. For example, the watch that was originally my first choice, Samsung Gear S3, proved to run on Tizen OS, and you cannot try out a Wear OS by Google (formerly known as Android Wear) app on a Gear S3 watch (Samsung Developers, 2018, March 1). If I was to design within Tizen Studio, even though it looks like Android Studio, the apps are not made in Java but instead either JavaScript/HTML/CSS or native in C (Tizen Developers, 2018, January 18). So, I preferred the Gear S3 watch, but I still made the choice to move forward with Wear OS and a Java/Android Studio-app, based on my previous experience in app development in that developer environment. Following that decision, I chose the watch Huawei watch 2 Nano-sim for this project, since it runs on Wear 2.0 and has BLE needed for the Tunstall smart locks, NFC needed for presence check in when caregivers attend to caretakers, a microphone to enable the possibility to develop for voice commands, and a sim-card slot that enables the watch to work independently from a phone. The disadvantage is the non-interchangeable bracelet, that hinders the user to personalize the watch.

4.1.2 Research on Tunstall

To learn about the TES, I read the app manual and installed it on my phone. Once I started working on the project I also conducted an interview with the TES-app product owner and developer, who helped me map the TES app and its service, and understand the idea behind it (see chapter 2.1.2). During the interview we discussed different parts of the app that could be interesting for smartwatch features-development. I also learned that the app did not use notifications at all. Together that led me to consider two out of the five app parts of TES, alarms and locks, plus the interaction of notifications, which is the basis of smartwatch designing. All in all, three intriguing design ideas.

4.1.3 Klippan: The elderly home care

Now you will get to know one of this project’s two main users: the caregivers within the elderly home care in Klippan. Klippan elderly home care is divided into four geographical areas, and I have collaborated with area West. The distances between caretakers are not greater than it is manageable by bikes. The caregivers bicycle all year round every day and night to all their visits, carrying everything they need, like work tools, keys, food and groceries for

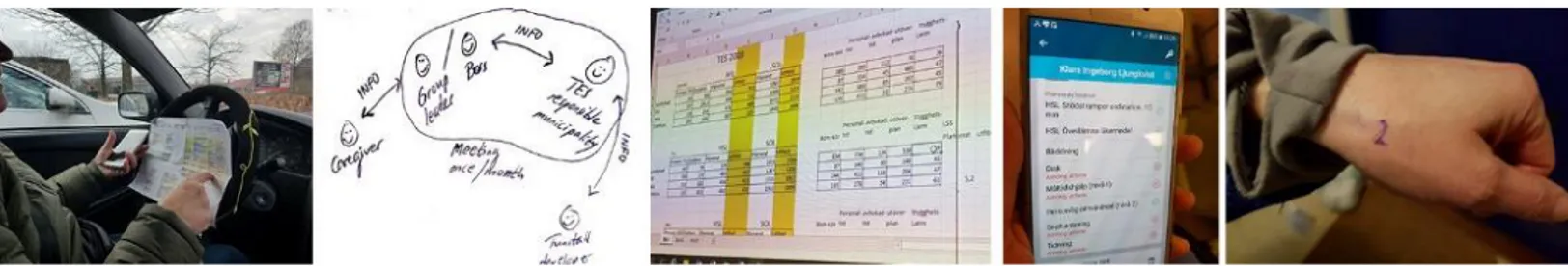

the caretakers and medicines (see figure 13, top image, a home care bike). During mornings the tasks mainly consist of morning routines for the caretakers, including showering, toilet visits, medicines, breakfast and getting dressed. Midday are the lunch rounds with a lot of very short rapid stop-bys (see figure 13, bottom image), in the afternoon walks and shopping, and in the evenings there are the evening routines. They also take care of other meal times, cleaning and alarms. A schedule for a caregiver consists of a series of visits to caretakers, and each visit contains a set of tasks. When the caregiver arrives she starts a logged visit on the phone, and when she leaves she ends the visit-log. The caretaker is charged by the minute. The caretakers are often quite lonely, with the elderly home care as their highly appreciated main social contact (see figure 13, second from the bottom). The caregivers are well aware of that, but cannot stay any extra minutes on that account, since their schedules are tight. But the caregivers say they enjoy their work, and enjoy biking around at least most of the time, and the atmosphere at the home care office is positive and engaged. The caregivers work alone on their rounds, except for some visits requiring assistance, meaning the visit needs two caregivers to manage one or several of the tasks. Putting a person with physical disabilities to bed is an example, because it means heavy lifting. The caregivers truly care for the elderlies and use a variety of techniques and tricks. At one time I saw that sherry was noted on a visit in the app. The caregiver told me that it used to be the medicine Malvitone, to add to the caretaker’s appetite, but the nurse said: “It works just as well with sherry!”. During a discussion in the lunch room we discussed

the future use of a smartwatch, suddenly one nurse mentioned that they are not allowed to wear anything beneath the elbows due to health regulations (Socialstyrelsen, 2015). The fact that caregivers are not allowed to wear anything beneath the elbows, highly affects the ability to wear a watch. See next chapter about the results on a watch placement-workshop.

Regarding notes on the visit, the caregivers lack a possibility to check whether for example, the sherry has been served. They also need to actively change a visit’s tasks if, for some reason, like a relative doing the dishes, a task has not been done. The default is that all tasks are pre-checked in the app (see figure

Figure 13. Four photos from a- day-in-the-life at Klippan’s elderly home care.

13, fourth image). That means tasks are easily forgotten, if the caregiver does not read thoroughly. Here I saw a potential to work with notifications on a smartwatch.

When the caregivers are handling locks, especially on the lunch rounds, they are constantly taking up and putting down their phone, to unlock and lock each door for each minimalistic visit. They often have several visits in the same building or corridor, and each visit takes about two minutes. But every time they handle a lock, two times per visit, they collect their phone from a pocket or waistbag and put it back again, to be able to carry the food box with them (see figure 13, bottom image). A smartwatch could perhaps simplify that interaction, I thought.

Another set of events that caught my attention was when a caretaker received an alarm. In Klippan they use Tunstall’s alarm central. Each time a caretaker presses her alarm button, the alarm central phones firstly one of two alarm mobile phones. Two caregivers are chosen each work shift to carry the alarm phones. If the first person does not answer, the alarm central phones the next. The caregiver receiving the alarm has a bunch of papers with today’s schedule for all caregivers in their area (see figure 14, left most image). She then tries to find someone who can act on the alarm, regarding tasks, distance and personality, and phones that person. If that person does not answer, or cannot go, the process starts over. This procedure is time-consuming and stressful for the person carrying the alarm phone, which means I saw it as a potential design space.

The caregivers told a story about a man with back pains helping his wife to the toilet, even though she had pressed her alarm button, but he had not in his heart to let her wait for an unknown amount of time. So when the home care arrived at their home, the alarm was no longer an issue. Apparently this happens regularly. For me, that equaled a design space. Another eye catching observation was the caregivers’ different methods to take notes regarding a visit or caretaker. I saw one use pen and paper, and another using the app which she told me she had to manually rewrite into the computer in the office since it did not sync. A third caregiver wrote on her hand. Then she disinfected her hands. And when she was to write her next note on her hand, the previous one was gone (see figure 14, last image). All these different and faltering note-taking systems pointed me towards another design space.

Figure 14. Observations that caught my eye during a-day-in-the-life in Klippan:

During an interview with the area manager, she told me that the caregivers, who use the TES app, tell her about issues or wishes regarding the app, then she and the other area managers have a meeting once a month with a municipality TES responsible person, and then that TES-person talks to Tunstall (see figure 14, second image. This means the Tunstall developers and the TES users never speak to each other. I interpreted that as an improvable area, a design space.

When I attended an area managers’ meeting, where TES-generated statistics were discussed (see figure 14, third image). It became apparent to me that changes to the schedule, like logging a visit, must be corrected on a computer at the end of the day; and if two caregivers change visits, all visits are first logged as “bom-run”, missed, and then re-logged as unplanned visits, which results in misguiding statistics. That statistic is what area managers discuss with municipality officials, and what they see of TES. So, if the statistics is what the TES buyers see from TES, and it does not work satisfactory, I recognized that as an important design space from a business point of view. To sum it up I found the following interesting areas for design: Locks (the constant up and down with the phone); Planning (with schedules in scroll-lists, and tasks pre-checked); Alarms (the paper list); and Communication chain (between Tunstall developers and the users); Schedule-changes (“bom-run” visits, instead of changed caregivers). But, as mentioned previously, a major obstacle was found. Now I will tell you how that issue was resolved.

4.1.4 Smartwatch placements

During the workshops regarding possible placements of a watch, due to caregivers’ obligation to be bare beneath the elbows, the caregivers tried out different placements (see figures 15 and 16). Together we found a set of possible choices: the upper arm; an extendable key chain; a necklace; and “Vårdklockan” where you fasten a watch on your chest pocket.

The alternatives were discussed and evaluated regarding for example eyesight, the risk of getting stuck, or losing the watch. For

them the key chain was the favorite. But, considering the project scope and time frame, I choose to stop at the conclusion that it would be possible to use a smartwatch within the elderly home care; and a variety with possibilities for the user to choose between regarding placement, based on personal preferences, could perhaps be the best solution.

Figure 15. Caregivers acting out watch placements.

4.1.5 Burlöv: An elderly care center

Harakärrsgården C-F, an elderly care center for people suffering from dementia, has four divisions with eight to nine apartments per division, decorated by the caretakers themselves (see figure 17, third image). In most care centers for demented all the doors are locked, since the caregivers need to constantly watch the elderlies so they will not hurt themselves or someone else. But in Burlöv they use the technology provided by Tunstall, with door alarms/sensors (see figure 17, the image in the red circle), GPS, and alarm buttons to enable the doors being unlocked and the caretakers walking freely about, both indoors and outdoors. If an elderly steps out the door, an alarm sounds amongst the caregivers. The nearest caregiver grabs one of the center’s jackets, sorted by size (see figure 17, bottom image), and accompanies the elderly on the walk. All the while giving the caretaker a sense of self power. So the technology and some investments into home decorations, like table cloths and turning the canteen into a restaurant (see figure 17, second image), has changed this care center. The area manager explained that negative symptoms connected to dementia have been reduced at Harakärrsgården, thanks to the freeing changes. They have less aggressions, paranoia, schizophrenia, depression, and apathy. She says:

“Today the center has 100% customer satisfaction,

while another care center for demented in the same village only has 40%.”

What I observed was a place where both the caretakers and the caregivers seemed happy and enjoying themselves (see figure 17, top image).

Another interesting observation in Burlöv, was that the caregivers at the center actually wear a key button around their wrists (see figure 18, first image). As long as they disinfect it between shifts it is allowed. A fact that partially contradicts what I learned in Klippan. But it is not the main focus of this study, which is why I suggest for the future, further research and designing regarding placements of a watch.

I also noticed how often the caregivers need to handle their phones while working at the center. For example, to

Figure 17. An elderly care center for people with dementia, where the Tunstall technology enables the caregivers to keep the doors unlocked.

attendance check-in in the caretakers’ apartments, for unlocking medicine cabinets, and for handling alarms (see figure 18, the three grouped images). Could perhaps smartwatch use simplify these interactions?

So why does the technology sometimes not work? Well, one explanation I found was that they had not installed smart locks on some doors, like the laundry room (see figure 18, second image from the right), only on the apartment doors. So the staff needed to carry their keys anyway, and saw therefor no point in using their wearable key buttons. As a business point of view, this is an interesting observation.

Regarding alarms, the caregivers told me that they normally shout into the corridor (see figure 18, image on the right), if they need help. They said that this system works, but I saw it as a design space.

To sum up, Burlöv uses TES alarms and TES locks, and both areas are interesting for future smartwatch use.

You have now read about what I learned during my initial research about the three main areas: smartwatches, TES, and the elderly care, through a series of activities. These results and activities laid the ground for identifying the design opportunities. So how did I do that?

4.2 Identifying design opportunities

This chapter is about how I identified the project’s design opportunities, and defined them in early concept sketches (see figure 19). Those sketches symbolize the ending of the project’s first phase, the research phase.4.2.1 Turning observations into DOs

I identified six design opportunities by looking at all my notes and photos and finding the most interesting observations

relevant for design. Each observation I translated into an insight, and each insight into something that tickles the designer imagination (see figure 20 for an example of how that looks). This last formulation is what in this paper is

Figure 19. This chapter's activities. For an over-view of the project activities, see figure 11, where this chapter is represented by the orange line. Figure 18. Observations that caught my eye during a-day-in-the-life at Harakärrsgården in Burlöv.

called, a design opportunity, DO. There are six potential DOs: Locks; Planning; Alarms; Changes/Notes; Sync; and IxD-process. To see on which observations each DO is based, see Attachment III.

4.2.2 Non-opportunities

Two of the six potential DOs were not suitable for this thesis project. The “Sync” is formulated “How do we design so that changes to the schedule or

changes to a visit, must not be double-corrected on a computer?”, and

focuses mainly on coding. That means it does not lie within interaction design. But working on this design space would help the users and could help Tunstall with a selling argument that their system communicates with other systems.

Another potential DO, called “IxD-process”, is formulated “How do we create

a design process that enables direct communication between more stakeholders, like users, buyers and Tunstall developers?”. This actually lies

perfectly within interaction design, but not within the thesis’s scope. Working on this design space could make Tunstall’s design process more effective, result in better user experiences, and by that increase sales.

4.2.3 Four workable opportunities

Four of the DOs I decided to move on with. Those are:

DO1 Locks: “How can we design key-less locks and session-logging which

free the caregivers’ hands?”

DO2 Planning: “How can we design for an easy overview of the schedule for

“right now” with tasks and reminders?”

DO3 Alarms: “How do we design to reach the right caregiver with an alarm

without disturbing the work for someone else?”

DO4 Changes/Notes: “How can we design an easy to use and easily

reachable note-system that communicates between caregivers and the system?”

By now I knew I had some interesting findings that could be of interest to Tunstall, so I held two presentations at Tunstall. During those we discussed the findings and ideated on the design opportunities.

4.2.4 Early concept sketches

On each DO I brainstormed. These brainstorming notes I synthesized into ideas (see Attachment V). Then I chose the interesting ideas and used them as basis for the first iteration of sketches (see figure 21). The early concept sketches mark the ending of the research phase.

5 Designing phase

This chapter is about the development of the design during the thesis project’s second phase, where a design intervention approach was used (see chapter 3.1). That means that I was designing during this phase, while still researching.

The design development is presented in three stages: firstly, the second iteration of sketches; secondly, the first iteration of prototyping; and finally, the second iteration of prototyping and the project’s final design proposition.

Figure 21. Early concept sketches on Design Opportunities for: Locks; Planning; Alarms; and Notes/changes. These sketches symbolize the result and ending of the project’s first phase, the research phase.

All iterations are designed based on workshops with stakeholders, where feedback were received on both the design, the future and the present.

5.1 Sketch iteration

In this chapter you can read about how I chose which two design opportunities to work further with, and do a second iteration of sketches on. In figure 22 you can see which activities were included.

5.1.1 Workshop/ideation “Early concept sketches”: Klippan

Findings during workshops on first iteration of sketches, the early concept sketches, that helped the development of the design will be exemplified now. A caregiver commented that the interactions must not be too complicated, while she pointed at the planning-concept with its many different user interfaces.

And at first everybody was very positive toward the idea of locking and unlocking using a smartwatch instead of the phone. But as one of the nurses said:

“What will happen when we have laundry duty? Then we go down into the

basement to do laundry, and lock the apartment door, but we do not stop the caretaker’s session. How can we do that with a watch?”

Another example of interesting feedback, is when the discussion continued about the locks-concept, and one caregiver suddenly asked the others: “Sometimes the

wrong [non-intended] door could be opened, right?” They

all agreed that sometimes a door on a different floor can be opened, or when the doors are really close (see figure 23). They suggested that you need to hold your smartwatch close to a lock to unlock a door.

Figure 23. Quick-sketching during the workshop, showing how a caregiver can accidently open the wrong caretaker's door.

Figure 22. This chapter's activities. To get an overview of the project activities, see figure 11, where this chapter is represented by the yellow line.

Klippan were excited about the idea of not having to go through paper schedules to handle incoming alarms. After that the remaining discussion on alarms, was about the little image of the possibility of producing statistics on accepting/denying alarms. They agreed that statistics actually could be beneficial for everybody. They reasoned, that if it became visible to everybody how it differed between caregivers regarding how many alarms you accept, perhaps that could be grounds for valuable discussions and development. The workshop results showed that the most obvious DO regarding a smartwatch’s affordances, is locks, with the benefit to not constantly needing to pick up and put back a mobile phone. The alarms were the DO that was most generative for design ideas. Adding to the decision to pick that DO to work further on, was that all stakeholders prioritize alarms, and the interactions around the alarms affect everyday work-life for the users. So, I decided to go on sketching another iteration of sketches for alarms and locks.

5.1.2 Sketch #2

For the second iteration on sketches I worked on alarms and locks. This time I sketched differently for the two user groups, the elderly home care and the care center, since I now knew more about their different conditions. In the sketches (see figure 24), I have made more detailed interfaces and simple wireframes, based on observations and discussions during workshops with the users. I have also started to look at design guidelines, and adjusted some of the design accordingly.

Figure 24. The second iteration of sketches, “concept and interfaces”. Red frames are alarms for the elderly home care.

Blue frames are locks for the elderly home care. Yellow frames are alarms for the elderly care center.