DISSERT A TION: MIGR A TION, URB ANIS A TION, AND SOCIET AL C HAN GE MALIN MC GLINN MALMÖ UNIVERSIT

TR

ANSL

A

TIN

G

NEOLIBER

ALISM

MALIN MC GLINN

TRANSLATING

NEOLIBERALISM

The European Social Fund and the Governing of

Dissertation series in Migration, Urbanisation,

and Societal Change

Doctoral dissertation in Urban Studies Department of Urban Studies Faculty of Culture and Society

Information about time and place of public defense, and electronic version of the dissertation: http://hdl.handle.net/2043/24006

© Copyright Malin Mc Glinn, 2018

Cover image: Adaption of cartoonist WE Hill’s illustration “My wife and my-mother-in law. They are both in the picture – find them”, Puck, v.78, no. 2018 (1915 Nov. 6), p.11.

Supported by grants from the Swedish Society for Anthropology and Geography (SSAG) and Stiftelsen Lars Hiertas minne

ISBN 978-91-7104-826-4 (print) ISBN 978-91-7104-827-1 (pdf) Holmbergs, Malmö 2018

MALIN MC GLINN

TRANSLATING

NEOLIBERALISM

The European Social Fund and the Governing of

Unemployment and Social Exclusion in Malmö, Sweden

Malmö University, 2018

Faculty of Culture and Society

Tidigare utkomna titlar i serien

1. Henrik Emilsson, Paper planes: Labour Migration, Integration

Policy and the State, 2016.

2. Inge Dahlstedt, Swedish Match? Education, Migration and Labour

Market Integration in Sweden, 2017.

3. Claudia Fonseca Alfaro, The Land of the Magical Maya: Colonial

Legacies, Urbanization, and the Unfolding of Global Capitalism, 2018.

4. Malin Mc Glinn, Translating Neoliberalism: The European Social Fund

and the Governing of Unemployment and Social Exclusion in Malmö, Sweden, 2018.

Publikationen finns även elektroniskt, se www.mau.se/muep

CONTENT

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... 7

PREFACE: A VIEW FROM MALMÖ, SWEDEN ... 11

1. POINTS OF DEPARTURE ... 13

1.1 Research aim, questions, and object of study...13

1.2 Aspects and assumptions ...17

1.3 Encountering the European Social Fund ...19

1.4 The prison and the food ...23

1.5 Analytical and theoretical concepts ...26

1.6 Research fields ...32

1.7 Structure of the thesis ...35

2. METHODOLOGY & METHOD ... 38

2.1 Studies of governmentality ...38

2.2 Methodological principles ...42

2.3 On methods ...45

2.4 Multi-Sited Ethnography: Mapping and Translation ...47

2.5 What’s the problem represented to be? ...50

2.6 Following the projects about ...53

3. THE EUROPEAN SOCIAL FUND – A SHORT INTRODUCTION ... 57

3.1 Partnership and co-funding ...58

3.2 The Swedish program ...61

4. TRANSLATION AS FRAMING ... 64

4.1 Normalizing the precariat ...64

4.2 From human resources to empowerment strategies ...69

4.3 Problems, spaces, and human kinds ...72

4.4 Legitimacy and the language of expertise ...79

4.5 ESF-projects as modernity projects ...83

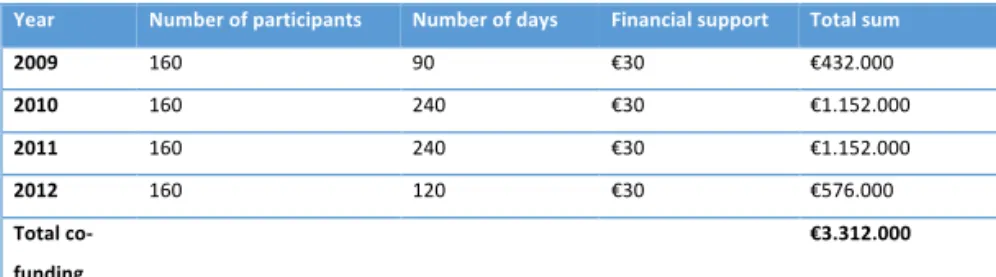

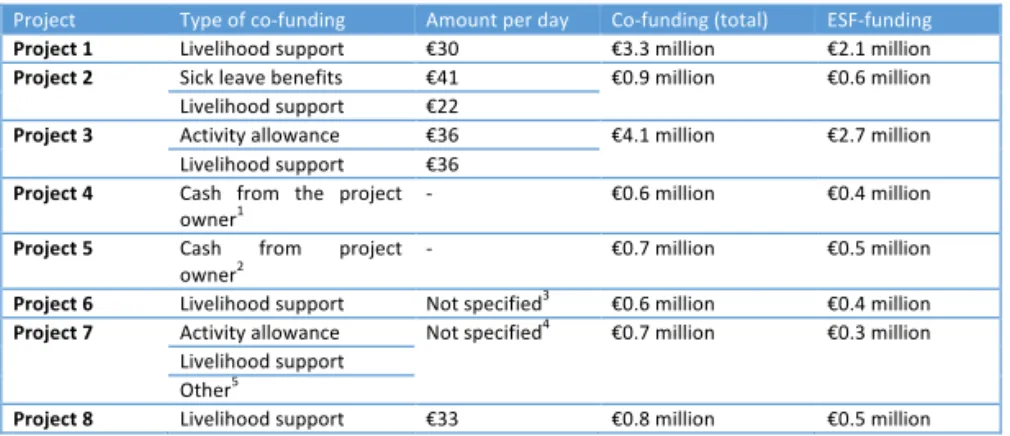

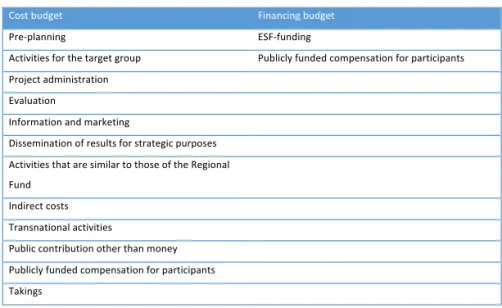

5. TRANSLATION AS CALCULATION ... 89

5.1 Critical accounting and ESF-projects ...90

5.2 How to turn €30 into €5.4 million ...94

5.3 The cost of non-attendance ...98

5.4 Balancing the ESF-budget ...100

5.5 Measuring good results ...103

5.6 Human kinds as raw material ...106

6. TRANSLATION AS ARRANGEMENTS OF VISIBILITY ...109

6.1 Promoting and branding the European Social Fund ...109

6.2 Investing in your future ...112

6.3 My story ...115

6.4 Learning lessons for life ...118

6.5 Catwalk Empowerment and the European Gift ...121

7. TRANSLATION AND LOOPING EFFECTS ...128

7.1 Arguments ...128

7.2 Systems of governing and social magic ...132

7.3 Containment, compassion, and inclusion ...134

7.4 Lost in translation?...139

REFERENCES ...143

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Writing an academic thesis is nothing one does alone. I am indebted to many people who, in different ways and on various occasions, have contributed to parts of this thesis by offering comments, critique, advice, support, friendship, and love.

In her role as my main supervisor, Carina Listerborn, has been my rock throughout this long and sometimes painful journey. I couldn’t have done it without you, Carina! Thank you for your support, advice, kindness, and friendship. I hope our journey together doesn’t end here.

I have also been lucky enough to have three insightful, smart, and engaged co-supervisors: Mikael Spång, Magnus Nilsson, and Timothy Engstrom. The fact that all of you come from different academic disciplines has been very helpful when navigating the interdisciplinary field of Urban Studies. Thank you! Special thanks go to Tim, without whom I would never have applied for a PhD-position. Our unofficial seminars at the Green Lion seem to have finally paid off. Thank you for believing in me when I didn’t. To the MUSA-collective: your friendship and support has been, and continues to be, invaluable. Thank you Martin Grander, Christina Hansen, Emil Pull, Rebecka Cowen Forssell, Henrik Emilsson, Ioanna Tsoni, Mikaela Herbert, Vitor Peiteado Fernandez, Maria Persdotter, Jacob Lind, Zahra Hamidi, Ragnhild Claesson, and Inge Dahlstedt. Along the way, you have provided me with encouragement, emotional support, laughter, and a beer or two.

I owe you big time. Special thanks go to Claudia Fonseca Alfaro whom I shared a room with when I first started. Your work ethic, sharp mind, and warm personality have been a real inspiration to me. Thank you, Claudie! You will not get rid of me yet!

I am very grateful to the following people who have read my work at different stages and given valuable comments: Per-Markku Ristilammi, Guy Baeten, Christian Fernandez, Stig Westerdahl, Tomas Wikström, Mustafa Dikec, Maja Frykman, Anna Lundberg, Despina Tzimoula, Victor Lundberg, Paula Mulinari, Malin Ideland, Kelly Knez, Kristin Järvstad, Mitchell Dean, Peter Parker and not least, Randi Gressgård who gave me very helpful comments at my final seminar.

I also want to congratulate some fantastic people who have managed to cross the finish line before me: Jesper Magnusson, Emil Edenborg, Mats Fred, Srilata Sircar, and Noura Alkhalili. You are amazing! Thanks so much for your friendship and for leading the way, and for encouraging me to keep going. You have been a real inspiration. To all my lovely colleagues at the Department of Urban Studies: thank you for providing me with encouragement and moral support throughout the years. I especially would like to mention Sandra Jönsson (aka best boss ever), Ebba Lisberg-Jensen, Karin Grundström, Anne-Charlotte Ek, Sabina Jallow, Mikael Ottosson, Anders Edvik, Jonas Alwall, Lina Olsson, Marwa Dabaieh, and Elisabeth Faier. I hope we can continue to work well and have fun together! I would also like to thank Karin Westerberg and Hoai Anh Tran for trusting in me as a teacher. Your support has been priceless. I also want to recognize everyone working with the educational program Urban Development and Planning. We make a really good team!

To all the students with whom I have discussed democracy and planning over the past four years. You are the people who give me energy! It has been a true pleasure engaging in conversations with you, and you teach me things every day. I wish you all the best for the future and I hope our paths cross again.

To my family in Rochester: Meredith Davenport, Jim Myers, Jessica Lieberman, Amit Ray, James Hall, James Winebrake, Anne Howard, Roberley Bell, Brian Thorn, and Diane Attea. Thanks for your friendship and hospitality, and for providing me with a home away from home. Thanks also to Jim McIntosh and Janet Gomez at the City of Rochester for being so generous and warm, and for letting me work from your office.

Over the years, I have been lucky to have worked with so many great people in the Doctoral Student Union at Malmö University. Thank you Margareta Serder, Susan Lindholm, Erik Snoddgrass, Åsa Ståhl, and Erliza Lopez Pedersen. Together, we have shown that hard work can really make a change, albeit slowly.

I am very lucky to have so many friends, within and outside academia. Our conversations, pub crawls, lunches, runs, Skype calls, chats, parties, laughs and cries are and have been priceless. You truly are my safety net and my inspiration. Thank you for putting up with me and holding my hand when I have needed it: Katja Troberg, Johanna Palmer Laws, Frida Leander, Lisa-Marie Teubler, Otto Björnberg, Cecilia Hultman, Bryan Cowie, Damian Finnegan, Micael Nord, Christan Penalva, Timothy Bender, Meghan Young and many many more. And to Karin Hallström: I think about you every single day. Thanks for smiling down on me from Nangijala and making me a stronger and better person. You are with me. Always. To my partner in crime, academia, and love: Ingrid Jerve Ramsøy! You have been my life line in so many ways over the past five years and I can’t imagine a world without you. No words can express what our sisterhood and friendship mean to me. I would never have been able to do this without you. I’ll be with you all the way to make sure that you cross that goal line too. But first, you have more important things to do.

I am very blessed to have such a loving, supportive, and wonderful family! My deepest thanks go out to my mother Marianne, my father William, my second mother Sharon, my second father Leif, my sister Sarah, my brothers William and Christian, and my

brother-in-law Albert. Thanks also to my aunt Ingrid and uncle Rolf, two more heroes of mine. I wouldn’t have made it if it wasn’t for all of you. To Erik: thank you for all the support I could ever ask for. You never get sick of me even though we both know that I can be and have been a real pain at times. There is no way I can ever re-pay you for all the times you have listened to me and been at my side. I am sorry for making you read this thesis over and over again! Thank you for making it so much better!

To Patrik: thank you for believing in me ever since I first started higher education in 2002. Your hard work, support, encouragement, and friendship means the world to me and I wouldn’t be here without you. You are the best father our daughter could possibly have. Thank you so much for being you.

And to Stella: You are my best friend, the light of my life and my greatest love. You ask the best questions and you make me better in every way. Finally, you can stop asking me when my book will be finished because it is. I dedicate it to you, my brave, funny, kind, and beautiful daughter. The sky is the limit for you. Jag älskar dig från månen och tillbaks igen.

PREFACE: A VIEW FROM MALMÖ,

SWEDEN

September 2010

A new morning dawns in Malmö, a city of approximately 300.000 inhabitants in the south of Sweden. People in all parts of town set off to start the day by taking their children to school and going to work. For a few women, the morning starts as many others, by opening the doors to the “work-integrating social enterprise”1 where

they are employed. They start the day by preparing the lunch that they sell every weekday; however, today is not an ordinary day. With the upcoming national elections just around the corner, Malmö, like other Swedish cities, is buzzing with anticipation. Who will win? Will the right-wing Sweden Democrats2 get into parliament? And if so,

what will this mean for the political landscape?

A well-known face, followed by a group of journalists, shows up at the door. Camera flashes go off as the prominent figure within Swedish party politics makes her way through the crowd. She is “welcomed with opened arms” by the women who work there, stays for a while and has a coffee.3 “The next time you come here, I hope

1 According to SKOOPI, an interest group for “work-integrating social enterprises” [Arbetsintegrerande sociala företag], such enterprises have the overarching goal of integrating people with “great difficulties” into the labor market. This is achieved both by individual measures such as vocational training and rehabilitation, and by job creation. The enterprises re-invest their profit into the business in order to create more job opportunities for others. See Regeringen. Handlingsplan för arbetsintegrerande sociala

företag.

2 The Sweden Democrats is a political party mostly associated with a clear anti-immigration agenda. In the national elections in 2014, the party received around 13% of the votes and thereby became Sweden’s third largest party.

it’s in the occupation of Prime Minister” one of the employees is quoted as saying. “I believe that the Social Democratic party is the best political party for foreigners,” she continues. Before leaving, the politician receives presents: “a crochet red rose” and a “pearl necklace.”4 The second stop of her election campaign in this part of

town is at a nearby venue in which an audience of about one hundred people has gathered to hear her talk. “It is important to vote,” the politician announces. “Many of those living here are those who the Sweden Democrats talk about.” “We have problems in Sweden,” she continues, “but they are not about skin color but concern issues of class and social circumstances.”5

4 Mattson, Anna. Mona Sahlin jagar röster i Rosengård, Expressen, 8 September, 2010. 5 Malmö TT. Öppna famnen för Sahlin hos Yalla.

1. POINTS OF DEPARTURE

1.1 Research aim, questions, and object of study

This thesis is concerned with how the governing of unemployment and social exclusion is accomplished through labor market projects that are initiated, tailored, and co-financed by the European Social Fund. Such projects, henceforth referred to as ESF-projects, are described by the European Commission as “Europe’s main tool for promoting employment and social inclusion.”6 The Fund’s goal is to

“help disadvantaged people into society” and to ensure “fairer life opportunities for all.”7 The social enterprise that the story snippet

in the preface is centered around is the result of three such projects, the first of which began in 20068 and was then followed up by

additional funding during the years 2007-2010.9 The female project

participants who were enrolled in the projects were identified as suitable candidates because they met the criteria of being dependent on social welfare and were said to have little or no previous education or work life experience.10 When talking about the participants, the

project owner states that “[they] are women who have lived in Sweden for over 15 years but have hardly moved outside of

6 European Commission. ESF - European Social Fund. 7 Ibid.

8 The first project ran between February 2006-June 2007 and aimed at enhancing levels of competence and gender equality. Funding came from the European Social Fund as well as from the local government. See Project 6, Trapphuset Rosengård, Application, Dnr 2008-3040002. Also see Friis, Eva. Projekt

Trapphuset Rosengård. Utbildningsverkstad och empowermentstation för invandrarkvinnor på väg mot arbete, Research Report in Sociology of Law 2010:1, Lund: Lund University, 2010.

9 Ibid. The second project ran between August 2007-December 2007, and the third project ran between May 2008-April 2010.

10 Friis. Projekt Trapphuset Rosengård. Utbildningsverkstad och empowermentstation för

Rosengård,”11 an area in Malmö most commonly referred to as

“segregated,” “excluded,” and “deprived.” “This was a group of people,” the project leader continues, “on which society had practically given up: a group that had been on the right track towards a working life but who had failed and not been able to come back again.”12 The enterprise and the ESF-projects that led up to

its realization therefore provided “a way out of isolation for these people.”13

Along the way, the participants have engaged in different activities such as educational workshops, coaching, and empowerment programs. The enterprise has, in turn, led to other project-based activities,14 additional ESF-funding,15 commercial spin-offs,16 and,

as will be illustrated by additional story snippets throughout the thesis, received attention, praise, and visibility. ESF-projects, as methods for tackling unemployment and social exclusion, have over time become everyday practices in Malmö as well as in other European cities. Material related to eight projects that were carried out in Malmö between 2007-2013 form the empirical starting point, but not the limitation, for this study.17 During this period, the

European Social Fund had a budget of €75 billion18 out of which

approximately €630 million (6.2 billion Swedish kronor, SEK) was allocated to Sweden.19 The “participant target” for projects intended

11 Swedish ESF-council. Trapphuset. 12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 One such activity is the educational workshop “Sumak” which is described as “a tasty road to diversity” [en smakrik väg mot mångfald]. Participants were engaged in different activities such as the “privilege walk” and cooking classes. The workshop was a collaboration between Kryddor från Rosengård [Spices from Rosengård] and Drömmarnas Hus [The house of Dreams], and was financed by the European Social Fund. See Swedish ESF-council. Slutrapport Summak, 2011; Tranquist, Joakim.

Utvärdering av Summak, Lomma: Tranquist Utvärdering, 2013.

15 See Swedish council. Y-Allas jobb; Swedish council. Y-Allas ambassadörer; Swedish ESF-council. Yalla Sofielund.

16 For instance, two books entitled “The road to Yalla- a book about the women from Yalla Trappan” [Resan till Yalla. En bok om kvinnorna på Yalla Trappan] and “Yalla Trappan – this is how we did it” [Yalla Trappan – så här gjorde vi]; a brand of spices called “Spices from Rosengård” [Kryddor från Rosengård]; photo exhibitions, a brand of marmalade, and appearances on tv-programs. Both the local and the national media have reported on different activities. See Kryddor från Rosengård. Välkommen

till smakresan; SVT. Annes härliga matrekord hos kvinnorna på “trappan” i Zlatanland, 2015.

17 A list of all the selected projects is presented in chapter 2, as well as in the reference list. 18 European Commission. The European Social Fund. Investing in people 2007-2013.

19 Swedish ESF-council. Socialfonden 2007-2013. It should be noted that Sweden, in total, received €1,6 billion via the European Social Fund and the European Regional Development Fund to meet the goal of “regional competitiveness and employment.” See European Union. Results of the negotiations of Cohesion Policy strategies and programs 2007–13, Cohesion

to help people “far away from the labor market”20 was set to 75.000,

including “at least 15.000 foreign born participants, 15.000 young people, and 10.000 who are classified as long-term sick.”21

I believe that ESF-projects are interesting objects of study because they can be viewed as manifestations of what Wendy Brown and others refer to as a neoliberal political rationality. By political rationality, she means “a specific form of normative political reason organizing the political sphere, governance practices, and citizenship.”22 Moreover, a political rationality is not, Brown

continues, “equivalent to an ideology stemming from or masking an economic reality, nor is it merely a spillover effect of the economic on the political or the social.”23 Rather, a political rationality governs

the truth criteria for what is thinkable, sayable, and doable at certain historical moments. Viewing neoliberalism as a political rationality means conceiving of it as more than market economic policies and market governance, for instance. While not dismissing that neoliberalism encompasses policies that “dismantle the welfare states and privatize public services,”24 Brown’s perspective highlights that

neoliberalism “also involves a specific and consequential organization of the social, the subject, and the state,”25 and, as a result, changes

the very meaning of the demos.26

The European Social Fund and the labor market projects that it initiates are merely one example of how neoliberal political rationalities are transformed into what Peter Miller and Nikolas Rose call “programs of government” via policies, rules, regulations,

target goals, and criteria that are decided by the European Commission. Such programs, Miller and Rose continue, “are not simply a formulation of wishes or intentions […] but lay claim to a certain knowledge of the sphere or problem to be addressed.”27

20 These projects are called PO2-projects. The difference between PO2-projects and PO1-projects will be further explained in chapter 3.

21 Swedish ESF-council. The Social Fund in Figures 2014. Project participants and benefits. 2014. 22 Brown, Wendy. American Nightmare: Neoliberalism, Neoconservatism, and De-Democratization, Political Theory, 34(6), 2006, p.693.

23 Ibid. 24 Ibid. 25 Ibid.

26 Brown, Wendy. Undoing the demos: neoliberalism’s stealth revolution. New York: Zone Books, 2015.

Other areas include education, sustainable development, and research, to mention only a few.

What is interesting to me is that ESF-projects combine issues of unemployment and social exclusion, areas which have traditionally been handled by the Swedish welfare state. This is compelling because, although sharing many features, neoliberalism takes a slightly different form in different geographical spaces. The form it takes is path-dependent and influenced by geographical trajectories and historical imaginaries, and some traditions of thought and practice have, says David Harvey, been harder for neoliberal rationalities to penetrate than others. “Old-style social democracies and welfare states such as New Zealand and Sweden,” he argues, have been, at least up until quite recently, “more resilient to far-reaching neoliberal reforms.”28 Harvey refers to this as

“circumscribed neoliberalization,” meaning a form of neoliberalism that, on the one hand, holds on to an old-school welfare system based on ideas of social justice and fair redistribution of economic resources while, on the other hand, adjusts some policies and practices according to market-based pressures.29 Neoliberalism,

should then, as worded by Aihwa Ong, be “conceptualized not as a set of fixed attributes with predetermined outcomes, but as a logic of governing that migrates and is selectively taken up in diverse political contexts.”30 Ong differentiates between Neoliberalism

and neoliberalism and argues that the former refers to more classic Marxist explanations and approaches, while the latter views neoliberalism as “a technology of governing ‘free subjects’ that co-exist with other political rationalities.”31 What is especially

interesting about the ESF-projects that are part of this study is, following Ong’s definition of neoliberalism (with a small n), that they can tell us something about the ironies, ambivalences, and contradictions that occur when neoliberal political rationalities and certain “truths” about social exclusion and unemployment migrate from Brussels to Malmö, a geographical space that has historically

28 Harvey, David. Neoliberalism as Creative Destruction, The ANNALS of the American Society of

Political and Social Science, Volume 610, 2007, p.23.

29 Harvey, David. A brief history of neoliberalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005, p.112. 30 Ong, Aihwa. Neoliberalism as a mobile technology. Transactions of the Institute of British

Geographers, 32(1), 2007, p.3.

been governed by policy and interventions most associated with the Swedish welfare state.32

The aim of my thesis is to map and problematize how ESF-projects, as examples of neoliberal programs of government that promote social cohesion and combat unemployment amongst identified “ethnic others,” become operational and legitimized in the Swedish context through multiple acts of translation. By scrutinizing the discursive, calculative, and visual practices that constitute them, I also want to consider both some of the consequences of this way of governing, as well as the larger political landscapes in which they function.

The questions that guide my research are:

I. Through what translations are ESF-projects made legitimate and operational in Malmö, Sweden?

II. What ironies, ambivalences, and contradictions are embedded in this way of governing?

III. What political claims for social justice are incentivized and legitimized by this way of governing?

1.2 Aspects and assumptions

So far, I have stated the aim of the thesis and the questions that will guide me in my investigation. I have also described why I believe that ESF-projects are interesting objects of study. However, another way of describing what this thesis is about is to point to the assumptions on which it is premised. The first assumption is that every phenomenon can be seen, interpreted, and critiqued from different

aspects. This doesn’t mean that one way of seeing things is

necessarily truer or better than another. Rather, it means that, just like the cover picture of this thesis illustrates, two (or more) different pictures, versions, narratives, or rationalities can be operating at the same time. Karl Marx saw capitalism in this way: as something that can be both productive and destructive at the same time and in the

same moment.33 Others have also gone down this path of thinking.

One such person is Johan Asplund, who in his beautifully written book, Om undran inför samhället, talks about aspects as replacing one lens with another.34 In connection to the research ahead, this

means that I will try to shed light on ESF-projects from an aspect that is more critically focused than the critique that is encapsulated in mainstream reports and common political discourse. I don’t reject the fact that the European Social Fund might indeed be Europe’s most important tool for combating unemployment and social exclusion. But, as the idea of aspect thinking teaches us, nothing is only one thing.

The second assumption is that a person largely becomes what systems of social classification allow and facilitate. Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann talked about this in The Social Construction

of Reality. They used the word “internalization” to describe this

sociological process.35 I instead favor the term “social magic,” which

originally comes from Pierre Bourdieu.36 However, I use it in a much

simpler way than he does and I take Judith Butler’s account as my starting point.37 For her, as for me, social magic indicates a social

process in which, for example, women are produced as women. She writes: “to be hailed or addressed by a social interpellation is to be constituted discursively and socially at once […] being called a girl from the inception of existence is a way in which the girl becomes transitively girled over time.”38 Social magic in this text is thus

connected to naming and categorization, as well as to performativity; i.e., the magical transformation that occurs when someone becomes or performs what is expected of that someone. Butler reminds us of the fact that “what happens in linguistic practices reflects or mirrors what happens in social orders conceived as external to discourse itself.”39 What we think of ourselves, how

33 Marx, Karl. The Communist Manifesto. Chapter 1: Bourgeois and Proletar, Centenary edition. London: Communist Party, 1948.

34 Asplund, Johan. Om undran inför samhället. Uppsala: Argos, 1970, p.61.

35 Berger, Peter & Luckmann, Thomas. The Social Construction of Reality. New York: Anchor books, 1966.

36 Bourdieu, Pierre. Language and Power. John B. Thompson (ed.). Translated by Gino Raymond & Matthew Adamson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991.

37 Butler, Judith. Performativity’s Social Magic. In Bourdieu: A Critical Reader, Richard Shusterman (ed.). Oxford: Blackwell, 1999.

38 Ibid, p.120. 39 Ibid, p.122.

we perform our subjectivity, and how our social performances are conceived and accepted, are then bound to knowledges about how we should be. Furthermore, the process of social magic is always contained and produced from specific positions (i.e., social, cultural, and economic) and from a body (e.g., white, brown, black, normal, healthy, etc.).40 Performativity, then, Butler continues,

“describes both the process of being acted on and the conditions and possibilities for acting.”41 I will return to this discussion in chapter

2, and in the concluding chapter 7 where I discuss the relation between systems of governing and social magic.

Before moving on to outlining analytical and theoretical concepts, related research fields, and the structure of the thesis, I will first describe how I came across ESF-projects and, by doing so, both describe my journey into this field of research, as well as pinpoint the political problems that I hope to address in this thesis.

1.3 Encountering the European Social Fund

The first time I saw the ESF-logo was in a meeting room in a local citizen service office in an area of Malmö that the media, the local population, and the authorities most often refer to as segregated. It was in 2011-2012, about a year or two before I started my PhD education. I had come to attend a meeting about a nearby school. Given my background in migration studies, I was there to offer my “expertise” on the situation. Sitting in the room chitchatting with the rest of the group, I glanced across the room. I saw the sticker on the window: “The European Social Fund – investing in your future.” It looked like the flag of the European Union, the message printed underneath. From then on, I started noticing logos and stickers everywhere: in City Hall meeting rooms, in offices at Malmö University, and on windows of local NGOs. I picked up a couple of brochures and read through them, not sure what I was looking for. The European Social Fund promised a better life to people and its projects were described as investments in people.

40 This discussion has been elaborated by for instance Toril Moi in Appropriating Bourdieu: Feminist Theory and Pierre Bourdieu’s Sociology of Culture. New Literary History, 22(4), 1991: 1017-1049. 41 Butler, Judith. Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly. Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press, 2015, p.63.

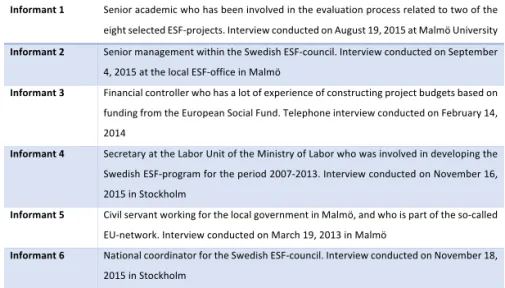

When I began my PhD education at Malmö University in 2013, I started to look into the projects in an in-depth way. I began by comparing the intended outcomes stated in the project applications with the represented outcomes presented in the evaluations. Some of the projects had shown better results than others. For a few individuals, they had really made a change. For others, they were just another project. But their success rate was not really what was interesting to me. I continued to follow the projects about, through documents (e.g., project applications, evaluations, rules and regulations), promotional videos portraying successful project candidates, newspaper articles, blogs and TV-programs. I even went to Brussels to talk to people working for the “Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion Directorate,” a permanent department of the European Commission with responsibility for issues related to unemployment.42 In addition, I interviewed people who had been

involved in writing the Swedish ESF-program for the period 2007-2013, former project workers and consultants who had been in charge of handling the budgets of various projects, as well as other “experts” such as some of my colleagues at the university who had been employed as project evaluators.

In the early stages of presenting my research, I was often asked about whether or not the projects had worked and if the people who were enrolled in them were indeed happier and more successful after the projects than before. In addition, I received questions about the European Union and about whether I thought that ESF-projects were a waste of taxpayers’ money. “What’s the alternative?” people asked me. I didn’t have any answers. One person who raised this kind of criticism was a man who, at the time, worked for the Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth [Tillväxtverket], a government body responsible for managing another structural fund.43 According to him, I was expressing a

criticism that “breathes resignation.”44 His commentary was based

on a talk that I had given on national radio and in which I had tried to outline what was both troubling and at the same time interesting

42 European Commission. Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion.

43 The European Regional Development Fund ERUF [Europeiska Regionala Utvecklingsfonden].

about the projects.45 In his mind, I was voicing a “widespread

skepticism about the European idea” and was guilty of so-called “Brussels-bashing.”46 “The problem,” he continued, “is that this type

of melancholy is starting to leave concrete marks. As we should all be painfully aware, it is the nationalist and xenophobic parties in Europe who successfully exploit this resignation and turn it into their own success.”47

But his criticism wasn’t the only such feedback I received. On November 26, 2013, I received an e-mail entitled “Empowerment is not the easiest thing.”48 It was sent from a person working closely

to the aforementioned “work-integrating social enterprise.” It read:

When Malin Mc Glinn describes our activities as well as other activities that are carried out under the umbrella term “work-integrating social enterprises” as dependent on project money and unable to fend for ourselves financially, it is a way to disparage everyone who is engaged in these activities. We are grateful for the government grants on offer - we know as well as Malmö University does that all grants are subject to uncertainty and demands - but the ambition is to show that women with immigrant background and unemployment experience are fully capable of being colleagues and competitors with anyone. We are excited to showcase what we can do - give us a cleaning task, a catering order or why not commission us to sew your sofa cushions and corporate gifts?

I stared at the e-mail for hours, reading it over and over. Anger. Sadness. Was the sender saying that it was impossible to offer a critique of the way in which the European Social Fund organized the governing of unemployment and social exclusion without being accused of disparaging individual participants or project workers? Was it ethically and morally wrong of me to question a system, a way of governing? Why was my critique taken personally? I wasn’t talking about individual project participants or project workers. I had no doubt in my mind that most people involved in these projects were trying to make a difference. My ambition was never to attack

45 Sveriges Radio. Vem vinner på projektsamhället? 18 November, 2013. 46 Sveriges Radio. Göran Brulin om EU:s strukturfondsprojekt. 47 Ibid.

48 Permission to use some of the contents of this mail has been granted by the sender. I have translated the mail which was originally written in Swedish.

or offend any individuals and I was certainly not trying to belittle anyone’s hard work or disregard the fact that some projects did indeed lead to employment. When looking back now, I realize that the email helped me immensely in thinking about the research problem that I wanted to address but so far had been unable to articulate. It triggered many questions in me, questions that can roughly be divided into three groups.

First, I pondered the statement about capability and wondered if the stated ambition was in fact adding to the problem it wanted to solve. Put in a different way: by stating that the ambition was to show that people who were categorized as “immigrants” and who were defined in terms of their non-Swedishness were fully capable, wasn’t the opposite achieved: constructing and producing an incapacity in need of the fund’s remedies? What problems were the projects hoping to solve and how were these problems and their solutions articulated, framed, and represented?

Second, what about the rhetoric of gratitude that followed from receiving government grants? What uncertainty and demands was the sender talking about? I thought about the fact that one of the projects that had led up to the social enterprise had a project budget of close to €1 million. Where did this money come from? What was it spent on and how was the project budget constructed? Who and what was calculated? The metaphor that came to mind while thinking about the project economy was a clock. When hanging on the wall ticking, it is just a clock and one can’t see how it functions; but when it is opened, the complexity of its inner workings comes into view. Small gearwheels turning in perfect harmony. If I were to open up the budgets in the same way, what would I find? What made them tick?

Third, why the need to “showcase what we can do?” Why were film teams, reporters, politicians, and students coming from near and far to observe and report on the enterprise? Why all the attention, why the spectacle? It was as if someone had found a rare bird or butterfly and people just had to see it with their own eyes to believe it. What was so special about the business that it generated newspaper

articles, books, a brand of marmalade and spices, cookbooks, TV-shows, and collaborations with local and multinational businesses? For whom and for what reasons was it valuable to create awareness, visibility, and recognition?

Something that struck me about the criticism that I encountered early on in my research, not only in the aforementioned e-mail conversation but from other people working closely with ESF-projects, was the mostly absent criticism that addressed the political aspect of this way of governing unemployment and social exclusion. Although a few people, working closely with the Swedish ESF-council, expressed frustration about the bureaucratic apparatus of the Fund, and were ambivalent about their own position within that apparatus, the criticism that they most commonly put forward was based on three strands of thought. First, that many project participants were better off after the projects even if they hadn’t managed to obtain a status of employment. Even if the project participants were still unemployed, the ESF-projects had helped them feel more empowered and included, and the projects influenced their self-esteem in a positive way and opened up possibilities for social networking. Second, even though some critics agreed that ESF-projects didn’t solve structural problems, they were convinced that it was better to do something than nothing. Third, that it was morally right to try to help those suffering from unemployment and social exclusion. These aspects are, of course, as “true” as others and I don’t necessarily disagree. However, another aspect is that they avoid and perhaps contribute to the political problems that I want to address.

1.4 The prison and the food

The political problem that I am concerned with can be illustrated by a story about a prison that was once described to me in a research seminar.49 The story is based on a scene from the French film Vive

la Republique (1997), in which a group of unemployed people in

the city of Le Mans decides to start a new political party. However, they know nothing about politics so Victor, their elected leader, is assigned the task of learning more. He therefore goes to the city and

49 The professor who told the story was Mustafa Dikec and it also appears in Dikec, Mustafa. Space, politics and the political. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, Volume 23, 2005: 171-188.

ends up having a conversation with a homeless man. In response to Victor’s question of what politics is, the man asks Victor to imagine a prison inhabited by people who were born within the prison walls without having ever committed a crime.

One day, the prisoners get frustrated over the fact that there’s no food in the prison and they begin to express their complaints loudly. Since there is representative democracy in the prison, the inmates elect a leader in the hope that she or he will be able to stop the food shortage. First, they choose a leader from the left wing who points out the unfairness of the situation but who is incapable of solving the problem. They then elect a leader from the right wing who suggests other measures. However, the food problem still remains. The prisoners don’t really care about the left or the right – they just want food! Over time, the food question comes to dominate all aspects of life in the prison. And this, says the homeless man to Victor, is the big fraud. Because even if the food problem one day is resolved, regardless which political party solves the problem, the prisoners will still be in prison. Politics, he concludes, is not about the food but about the prison.

In relation to my research, the anecdote points to the process of representing a problem and its subsequent solution. If the problem is represented to be an absence of food, then it is the problem of food shortage, not why there is a food shortage or why only some people are continuously subjected to it, which will be addressed. In the same vein, if problems of unemployment are thought of as being caused by insufficient skills and the need for coaching instead of an unfair distribution of capital or structural racism and prejudice, then it’s the former, not the latter that will be addressed. Moreover, if problems are discursively framed in relation to certain “human kinds” and to certain “spaces of deprivation,”50 then that will have

an impact on how problems and solutions are constructed in relation to these human kinds and spaces. By human kinds I mean, following Ian Hacking:

50 I use this phrase inspired by the work of Guy Baeten. See for example Baeten, Guy. The uses of deprivation in the neo-liberal city. In Urban Politics Now. Re-imagining Democracy in the Neo-liberal

City, BAVO (ed.). Rotterdam: NAi Publications, 2007; Baeten, Guy. Clichés of Urban Doom: The

Dystopian Politics of Metaphors for the Unequal City – A view from Brussels, International Journal of

“…kinds about which we would like to have a systematic, general and accurate knowledge; classifications that could be used to formulate general truths about people; generalizations sufficiently strong that they seem like laws about people, their actions, or their sentiments. We want laws precise enough to predict what individuals will do, or how they will respond to

attempts to help them or to modify their behavior.”51

The prison in relation to ESF-projects shouldn’t be interpreted as meaning the same as “structure” in the classic sociological sense. It is not a single institution or the State, nor is it an abstract and sometimes invisible net that captures some people based on categorizations such as race, gender, sexuality, and class. The practice of governing unemployment and social exclusion through ESF-projects isn’t the result of a single political program or policy and it can’t be blamed solely or simply on EU politics. Rather, the prison is both the practical ways of doing things and the rationalities that inform these practices. In Foucault-inspired language, this view can be referred to as governmentality, a concept coined to capture “the intrinsic links between ways of representing and knowing a phenomenon (rationality) and a way of acting upon it as to transform it (technology).”52 Through technologies of government,

political rationalities are anchored in “reality” and touch ground so to speak. Furthermore, the technologies through which “rationalities of government become capable of deployment”53

generate their own rationalities. The relationship between rationalities and technologies is thus dialectic. At certain moments (symbolically speaking), there is a certain level of agreement that there is a problem that needs solving, and such problems “usually come to be framed within a common language or at least one that makes dialogue possible between different groups of experts.”54

The rationalities and technologies of government shape what is thinkable, questionable, contestable, and changeable at certain moments of time. The question of framing and “truth-making,” i.e., how “the prison” is built and remains intact, constitutes the

51 Hacking, Ian. The looping effects of human kinds. In Causal cognition: A

multidisciplinary debate, Dan Sperber, David Premack, & Ann James Premack (eds.), New York, NY:

Oxford University Press, 1995, p.352. 52 Miller & Rose. Governing the Present, p.15.

53 Rose, Nikolas & Miller, Peter. Political Power beyond the State: Problematics of Government, The

British Journal of Sociology, 6(1), 2010, p.281.

political problem that I want to address. In the research presented below, this political problem more specifically has to do with how certain “truths” about unemployed “ethnic others” in Sweden are facilitated within and co-produced by the European Social Fund and the projects it sets in motion.

1.5 Analytical and theoretical concepts

In this chapter, I have so far mentioned a few concepts that I will now revisit and expand upon. The first is problematization, which is central to the aim of this thesis and which will be deployed in three interconnected ways. First, following Roger Deacon, problematization “is concerned with how and why, at specific times and under particular circumstances, certain phenomena are questioned, analyzed, classified, and regulated, while others are not.”55 As such, problematization defines the object of

study – that is the taken-for-granted truths that produce certain

objects of thought, behaviors, spaces, or practices as problems, on the one hand, or as apolitical, on the other hand. Second, it refers to a method of analysis that concerns re-narration, re-contextualization, and discourse analysis that questions the basis of taken-for-granted problem representations. Third and finally, problematization always starts by calling something into question e.g., a phenomenon, a practice, or an event. What that something is and why it becomes interesting to problematize is, needless to say, different for different people and depends on the larger surrounding socio-economic, historic, cultural, and political contexts in which that something occurs. It is also tied to the body of the person doing the problematization, and to social magic as discussed previously. For me, problematizing ESF-projects comes from a political and normative motivation to call into question practices that are legitimized in the name of diversity, inclusion and tolerance. According to Brown, such discursive configurations are examples of Foucault’s account of governmentality, meaning that which “organizes the conduct of conduct at a variety of sites and through rationalities not limited to those formally countenanced as

55 Deacon, Roger. Theory as Practice: Foucault’s Concept of Problematization. Telos, 118, 2000, p.127.

political.”56 These configurations change meaning over time.

Tolerance for example, once “widely recognized in the United States as a code word for mannered racialism”57 is nowadays used to

describe “the key to peaceful coexistence in racially divided neighborhoods.”58 Whatever their current meaning, the rationalities

travel and take a physical and institutional form through different documents such as guidelines, policies, and visions. A critical examination of how certain concepts function can thus, “reveal important features of our political time and condition.”59 Inspired

by Slavoj Zizek, I want to move away from what he calls “the old leftist notion” that it is “better to deal with the enemy who openly admits his (racist) bias,”60 and instead focus on practices, of which

ESF-projects are one example, that describe themselves as inclusive. The three dimensions of problematization that have been discussed here can be summed up by Butler, who says:

“…we can see that norms of the human are formed by modes of power that seek to normalize certain versions of the human over others […] To ask how these norms are installed and normalized is the beginning of the process of not taking the norm for granted, of not failing to ask how it has been installed and enacted, and

at whose expense.”61

The normative and political motivations that inform the ways in which I am involved in the problematization, re-narration, and re-contextualization of ESF-projects will be discussed further in chapter 2.

The second concept, which is at the core of this thesis, is translation. The starting point for my discussion comes from Michel Callon’s

Some elements of a sociology of translation, in which he follows

how the scallops of St Brieuc Bay are transformed through what he calls “four moments of translation.”62 Through these moments,

56 Brown, Wendy. Regulating Aversion: Tolerance in the Age of Identity and Empire. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 2006, p.4.

57 Ibid, p.1. 58 Ibid, p.2. 59 Ibid, p.4.

60 Zizek, Slavoj. Multiculturalism, or, the cultural logic of multinational capitalism, New Left Review, I/225, 1997, p.33.

61 Butler. Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly, p.37.

62 Callon, Michel. Some elements of a sociology of translation: domestication of the scallops and the fishermen of St Brieuc Bay. In Power, Action and Belief: A New Sociology of Knowledge?

which Callon terms problematization, interessement, enrolment, and mobilization, the scallops go from being living beings in the sea, to becoming numbers in tables, graphical representations, and subject to mathematical analysis.63 Translation is then, says Callon, “a process

before it becomes a result;”64 it is “the mechanism by which the

social and natural worlds progressively take form.”65 The result of

such processes of translation is a situation in which “certain entities control others.”66 Ultimately then, and much like the starting point

for Foucault, the sociology of translation is an approach to the study of power which focuses on the processes (moments of translation) that “result in the designation of the legitimate spokesman.”67

Although not employing Callon’s “four moments,” his study is used as a starting point for highlighting the inseparable relation between problematization and translation; both in terms of methods of analysis (discourse analysis, re-narration, and re-contextualization), and in terms of defining an object of study and connecting it to the wider production of truth. To link the language of the sociology of translation with the previously used language of governmentality, would be to say that the moments of translation that Callon speaks of can be viewed as the dialectic process through which political rationalities are transformed into technologies, and, also, a process in which the technologies feed back into and potentially upset or change, these rationalities. Governing, understood broadly by Paul Rabinow as practices “that contain institutionally legitimated claims to truth,”68 is thus, I argue, achieved through multiple processes of

translation. As pointed out by Barbara Czarniawska, among others,

such translations involve both a transformative dimension of defining and redefining different issues at hand, as well as a transportational dimension, which I interpret to mean the ways in which certain ideas are translated from one geographical context or spatial scale to another. Ideas and truths travel from the local community and

John Law (ed.). Sociological Review Monograph 32, London: Routledge, 1986, p.59. 63 Ibid, p.71.

64 Ibid, p.75. 65 Ibid. 66 Ibid. 67 Ibid.

68 Rabinow, Paul. Anthropos today. Reflections on modern equipment. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2003, p.20

become global, and global ideas seep down to the local context.69

As was pointed out previously, this dimension is important to me because it allows us to see what happens when ideas about social exclusion for instance, travel from board meetings in Brussels to local project leaders in Malmö.

This thesis is concerned with three identified processes of

translation, namely framing, calculation, and arrangements of visibility. These processes are the outcome of going back and forth

between the empirical material and other readings, and of trying to make sense of how the selected ESF-projects are made and how they function. They are also used as sorting mechanisms for my material, as ways of structuring the thesis, as well as entry points for problematizing how unemployment and social exclusion is governed through the European Social Fund in present day Malmö, Sweden. By framing, I mean on one level, the words and grammar used to describe people, problems, solutions, and spaces, because it is through language, says Foucault, that “the limits and the forms of the sayable”70 can be traced and, furthermore, related to the field

in which it is deployed. Beyond the purely linguistic usage, on another level, the translational act of framing and representing is deployed within social science contexts to describe the act of turning knowledge with meaning in one domain into meaning within another. In this light, framing is also a struggle for meaning that not only describes the world but also brings about relations in particular ways. When seen as a process that involves interpellation,

classification, narration and, representation, the latter of which I

believe to be the inseparable result of problematization and translation, the translation process of framing is part of what I described as social magic earlier; of being constituted discursively and socially as something, and performing accordingly. In addition, processes of framing are, as we will see, intimately tied to the rise of experts and the neoliberal language of expertise, which, in turn, creates certain practices such as the already decided-upon categories

69 Czarniawska, Barbara. On time, space, and action nets. Göteborg: GRI, 2004. Also see Czarniawska, Barbara and Sevón, Guje (eds.). Translating organizational change. Berlin: de Gruyter, 1996. 70 Foucault, Michel. Politics and the study of discourse. In The Foucault Effect. Studies in

Governmentality, Graham Burchell, Colin Gordon and Peter Miller (eds.), Chicago: The University of

and check-boxes on the project application form that the project leader must respond to in order to apply for funding. In chapter 4, I will problematize three processes of framing that are related to the construction of ESF-projects. The analysis will center on the multivalent relationship between colonial and neoliberal rationalities of government, and, in doing so, will also initiate a discussion about how compassion (and pity) functions to legitimize certain practices.

The second process of translation, calculation, refers to what Miller and others call calculative practices.71 In relation to the European

Social Fund and the projects it sets in motion, these are practices through which human kinds are classified, evaluated, counted, and reported. This is accomplished through a variety of measures such as accounting, by which Miller means “a process of attributing financial values and rationalities to a wide range of social practices, thereby according them visibility, calculability and operational utility.”72 Consequently, his advice is to direct attention to “the ways

in which accounting shapes social and economic relations,”73 and

to the mechanisms through which the choices open to individuals, organizations, and businesses are framed. In other words, we should take seriously the numerous methods of categorizing and counting that influence the ways in which we administer the lives of others and ourselves.74 Another way of saying this is, following Keith

Robson, that “the relationship between accounting and its social context can be understood as a process of translation,”75 in which,

for example, certain individuals and groups are “couched in the technical and professional discourses of economic representation,”76

thereby turning them into calculative objects that can be time-managed, recorded, measured, and compared. I have identified

71 Miller, Peter. Governing by numbers: Why Calculative Practices Matter. Social

Research, 68(2), 2001: 379-396. Also see Agyemang, Gloria & Lehman, Cheryl. Adding

critical accounting voices to migration studies. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, Volume 24, 2013: 261-272; Lapsley, Irvine, Miller, Peter & Panozzo, Fabrizio. Accounting for the city. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 23(3), 2010: 305-324. 72 Miller, Peter. On the interrelations between accounting and the state. Accounting,

Organizations and Society, 15(4), 1990, p.316-317.

73 Ibid.

74 Miller & Rose. Governing the Present.

75 Robson, Keith. On the arenas of accounting change: The process of translation.

Accounting, Organizations and Society, 16(5/6), 1991, p.550.

three calculative practices of accounting and auditing, which will be elaborated upon in chapter 5. The focus of the analysis is the complex and contradictory ways in which social benefits are re-calculated into co-funding, and what this means in terms of measurable outcomes and the evaluation of success.

By arrangements of visibility, which is the focus of chapter 6, I mean, following Emil Edenborg, “a specific staging or organization of what can be seen, heard and felt in the public sphere.” 77 As such,

I view the booklets, photographs, reports, posters, and films that are generated through the European project machinery as cultural products that offer a specific view of the world. According to Stuart Hall, such products are central to knowledge production and thereby contribute to “the giving and taking of meaning between members of a society or group.”78 The arrangements of visibility, as

they are produced by the European Social Fund, can thus be viewed as a translational process in which unemployable “ethnic others” become eligible for recognition according to neoliberal norms of inclusion. This is accomplished when, for example, the promotional needs of the Fund are translated into visual representations of successful project participants. In other words, the need of selling the European Union, promoting a European identity, and, as one informant put it, creating “legitimacy for a European membership,”79 is translated into the celebration of individual

project participants who “have made it.” The focus for the analysis is the complex relationship between visibility and recognition. Inspired by Jacques Derrida, as understood by Ilan Kapoor, I elaborate on certain aspects of gift giving to problematize this dimension of the European project machinery.

The theoretical discussions in chapters 4 through 7 - the last of which rests on some of Hacking’s thoughts about human kinds and looping effects, as well as on Sara Ahmed’s concept of containment - comprise what is often referred to as a theoretical framework. I choose not

77 Edenborg, Emil. Politics of Visibility and Belonging: From Russia’s “Homosexual

Propaganda” Laws to the Ukraine War. London: Routledge, p.34-35.

78 Hall, Stuart. Introduction, in Representations: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. Stuart Hall (ed.). London: Sage, 1997, p.3.

to describe this framework of ideas at length upfront but instead integrate theory when it is needed in relation to the material at hand. The contribution of this thesis to the wider debate is that it illustrates how ESF-projects, as examples of programs of government that are constructed and normalized through the idiom of neoliberal political rationalities, are made and function in the Swedish context of Malmö, thus providing an example of what Neil Brenner and Nik Theodore call “actually existing neoliberalism.”80 Additionally,

I hope that the discussions that I have throughout the thesis will contribute to thinking about the intertwined and inseparable processes of translation, subjectification, social magic, and looping effects, and also, to how we might think differently about how unemployment and social exclusion is governed in Malmö, Sweden.

1.6 Research fields

Previous research that serve as inspirational and advisory for this study can roughly be divided into four groups. The first group shares my empirical interest in the European Social Fund. However, such research has tended to focus on the European policymaking process and difficulties of accessing the Fund,81 or offers a criticism of the

financial dependency system that is created by it.82 Other studies

focus on the Fund’s equal opportunities objective and Europe 2020-strategy,83 or different aspects of European integration.84 In

addition, a steady stream of reports concerned with good practice routines, evaluations, and guidelines have been produced within this

80 Brenner, Neil & Theodore, Nik. Cities and the Geographies of ‘Actually Existing Neoliberalism.’ Antipode, 34(3), 2002: 349–379.

81 See for example Brine, Jacky. Over the Ditch and through the Thorns: Accessing European funds for Research and Social Justice, British Educational Research Journal, 23(4), 1997: 421-432; Brine, Jacky. The European Social Fund. Flexibility, Growth,

Stability, Sheffield: Continuum, 2002; Kosschatzky, Knut & Stahlecker, Thomas. A new

Challenge for Regional Policy-Making in Europe? Chances and Risks of the Merger Between Cohesion and Innovation Policy, European Planning Studies, 18(1), 2010: 7-25; Rivolin, Janin. EU territorial governance: learning from institutional progress, European

Journal of Spatial Development, Volume 38, 2010: 1-28; McCormick, John & Olsen,

Jonathan. The European Union – Politics and Policies, Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 2014. 82 See for example Camská, Dagmar. Financial Situation for Municipalities Supported by EU Funds,

International Advances in Economic Research, 19(3), 2013: 315-316.

83 See for example Brine, Jacky. Equal Opportunities and the European Social Fund: Discourse and practice, Gender and Education, 7(1), 1995: 9-22; Daly, Mary. Paradigm in EU social policy: a critical account of Europe 2020, Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 18(3), 2010: 273-284.

84 Rumford, Chris. European Cohesion? Contradictions in EU Intergration. London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2000.

field of study. In sum, this kind of research is more directly interested in the Fund itself. Although sharing some interest in the Fund, I am, as has already been pointed out, more interested in the political rationalities of which the Fund and the projects it sets in motion are manifestations. Thus, I am more attentive to how ESF-projects in Sweden are made, how they function, and what they do politically. The relation between my research and this type of research is hence interpretively and purposely loose.85

The second corresponding research area offers a criticism of what can be referred to as “the project society,”86 meaning a system of

governance that has an impact on how societal issues like poverty, integration, and spatial segregation can be dealt with. The critique that is offered is that projects that are intended as a method for organizing and managing societal problems very seldom lead to any real changes on a societal or structural level.87 Whether the focus

is on welfare projects, integration projects, area-based projects, or development projects, project-based governance of social problems has been compared to putting a bandage on a broken arm. As has been pointed out by Monika Krause, rather than solving complex problems, projects have a tendency to give rise to more projects and the project machinery becomes a self-feeding operation.88 This

research field is relevant for my thesis, especially in chapter 5 when I take a closer look at the ways in which project budgets are constructed and what this means in relation to Krause’s conclusions.

85 However, there are exceptions such as e.g. Mynttinen, Laura. Technologies of Citizenship in the

Finnish EU-Funded Empowerment Projects, Master diss, University of Helsinki, 2012; Vesterberg,

Viktor. Learning to be Swedish: governing migrants in labour market projects, Studies in Continuing

Education, 37(3), 2015: 302-316; Vesterberg, Viktor. Exploring Misery Discourses: Problematized

Roma in Labour Market Projects, European Journal for Research on the Education and Learning of

Adults, 7(1), 2016: 25-40.

86 Jensen, Anders Fogh. The Project Society. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2012.

87 See for example Forssell, Rebecka, Fred, Mats & Hall, Patrik. Projekt som det politiska samverkanskravets uppsamlingsplatser: en studie av Malmö stads projektverksamheter,

Scandinavian Journal of Public Administration, 17(2), 2013: 13–35; Abrahamsson,

Agneta & Agevall, Lena. Välfärdssektorns projektifiering – kortsiktiga lösningar av långsiktiga problem? Kommunal ekonomi och politik, 13(4), 2009: 35–60; Karlsson, Sandra. Områdesbaserad politik – möjligheter till strukturell förändring. Lokalt

utvecklingsarbete i marginaliserade bostadsområden i Malmö. PhD diss, KTH, 2016.

88 Krause, Monika. The Good Project. Humanitarian Relief NGO’s and the

The third related research area is what Ignacio Farías and Thomas Bender call the study of “urban assemblages.”89 The field takes as

its starting point the idea that the city “is made of multiple partially localized assemblages built of heterogeneous networks, spaces, and practices,”90 or what Czarniawska calls “laboratories.”91 It is

in these laboratories that the possibilities for and restrictions on urban life are constructed through e.g. technical systems, calculative activities, architecture, and planning. This approach to cities, in my view, has the potential of opening up “the traditional” field of urban studies to the influence of adjacent research areas. One such area is critical accounting, in which accounting is used as a tool for explaining everyday agents and practices that take place in cities.92 In

line with Rose and Miller, as well as scholars like Anthony Hopwood, and Ted O’Leary, I view the calculative activity of accounting as a technology of government that profoundly influences the management and governing of urban spaces and people living within them.93 My connection to urban assemblage thinking will be further

explained in chapter 2.

The fourth research field from which I take inspiration is related to the above but is more specifically concerned with how unemployment and un/employability in present day Sweden is governed through different technologies of government. Besides accounting, these technologies include different administrative systems, classifications and coding. Not only do such studies tell us about the systems through which governing is achieved, but they also bring forward how the act of working is conceived and what

89 Farias, Ignacio & Bender, Thomas (eds.). Urban Assemblages. How Actor-Network

Theory Changes Urban Studies. Abingdon: Routledge, 2010. Also see Farias, Ignacio.

The politics of urban assemblages, City: analysis of urban trends, culture, theory, policy,

action, 15(3-4), 2011: 365-374.

90 Ibid.

91 Czarniawska, Barbara. A Tale of Three Cities: On the Glocalization of City Management. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

92 McNeill, Donald, Global Cities and Urban Theory. London: Sage Publications, 2016.

93 Examples of critical accounting studies are Rose, Nikolas. Governing by numbers: figuring out democracy, Accounting, Organizations and Society, 16(7), 1991: 673-692; Rose, Nikolas.

Powers of Freedom. Reframing political thought, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004;

Hopwood, Anthony & Miller, Peter (eds.). Accounting as Social and Institutional Practice, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994; Miller, Peter & O’Leary, Ted. Accounting expertise and the politics of the product: economic citizenship and modes of corporate governance, Accounting, Organizations

and Society, 18(2-3), 1993: 187–206; Harney DeMaria, Nicholas. Accounting for African migrants

in Naples, Italy. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, Volume 22, 2011: 644-653; Kornberger, Martin & Carter, Chris. Manufacturing competition: how accounting practices shape strategy making in cities. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 23(3), 2010: 325–349.