What is in a name?

Media responses to the 2017 ‘Schaumkuss’ petition in

Switzerland

Nila Chea

Media and Communication Studies One-Year Master, 15 credits Spring 2019

Examiner: Michael Krona Supervisor: Temi Odumosu Word Count: 16’630

Abstract

In September 2017, an online petition urged a Swiss candy factory to change the name of its chocolate covered meringue candy from the questionable name “Mohrenkopf” (engl. moor’s head) to anything non-racist. This demand caused a big public outcry and led to the debate over the legitimacy of the name. The aim of this present thesis is to examine the role of the Swiss news media in a discourse of racism by looking at their response to the petition. The data sample of 30 newspaper articles was analyzed with an analytical framework modeled after van Dijk’s socio-cognitive approach to critical discourse analysis. The theoretical

framework for the analysis is based on mass communication theories, discourse theory as well as on the concept of commodity and retro racism. The results demonstrated the power of Swiss news media in the debate and showed how deep denial of racism is rooted in Swiss society, which finds expression in retro racism. Ultimately, the findings question the neutrality of Swiss news media in discourses of racism.

Keywords: Mohrenkopf, retro racism, critical discourse analysis, socio-cognitive approach, Switzerland, news media, discourse of racism, neutrality

Table of contents

Lists of tables ... 4 Lists of figures ... 4 1. Introduction ... 5 2. Background ... 8 2.1 “Überfremdung” ... 9 2.2 Postcolonial Switzerland ... 112.3 “Mundart” as part of the Swiss Identity ... 12

2.4 Racism in Switzerland ... 13

3. Literature review ... 15

4. Theoretical framework ... 18

4.1 Discourse Theory ... 18

4.2 Agenda Setting, Framing and Gatekeeping Theory ... 19

4.3 Retro Racism and Commodity Racism ... 21

5. Methodology ... 23

5.1 Socio-Cognitive Approach ... 24

5.1.1 Production and Control of Public Discourse ... 24

5.1.2 Mind Control ... 25 5.2 Analytical Framework ... 25 5.2.1 Macro-level Analysis ... 26 5.2.2 Micro-level Analysis ... 28 5.3 Data Sample ... 32 5.4 Limitations ... 34 6. Ethics ... 35

7. Results from the analysis ... 36

7.1 Macro-level Analysis ... 36 7.1.1 Participants ... 36 7.1.2 Setting ... 39 7.1.3 Genre ... 39 7.1.4 Topics ... 41 7.2 Micro-level Analysis ... 42 7.2.1 Referential Strategies ... 42 7.2.2 Predicational Strategies ... 43 7.2.3 Argumentation ... 45 7.2.4 Perspectivization ... 46

7.2.5 Strategies of intensification and mitigation ... 48

8. Discussion ... 51

9. Conclusion ... 55

Lists of tables

Table 1 – Grid for analysis of control on macro-level ... 26 Table 2 - Grid for analysis of control on micro-level ... 28

Lists of figures

1. Introduction

In September 2017, the “Komitee gegen rassistische Süssigkeiten” (engl. Committee against Racist Candy) submitted an online petition on change.org, urging the Swiss candy

manufacturer Dubler to change the name of their chocolate covered meringue candy from “Mohrenkopf” (engl. moor’s head) to something non-racist (Komitee gegen rassistische Süssigkeiten, 2017). The plea was soon picked up by all major Swiss German newspapers. Even though the debate over the questionable name was not new, it sparked heated

discussions and received a lot of reactions on numerous media platforms. One news article alone received over 1000 comments in their comments section, where the top comment received almost 10’000 upvotes (see Krähenbühl, 2017a). While “Schaumkuss” (engl. “foam kiss”) is an alternative German name for the chocolate covered meringue candy, the name “Mohrenkopf” still persists and is widely used in Swiss German.

The question at the core of the debate was whether the name “Mohrenkopf” was racist or not. However, this will not be the focus of this study. I am more interested in how the Swiss news media dealt with the racism debate and how this articulated certain power structures in the Swiss society. For this reason, the present master thesis aims at answering the following research question:

How did the Swiss news media respond to the 'Schaumkuss' petition about racist candy? Derived from the main research question, I will let the following sub-questions guide me through my research:

- What discourses emerged in the retelling of the debate? - How did the newspapers position themselves?

- What does this coverage articulate about racism and race relations in Swiss society?

According to Hall (1999, p. 271), racist ideologies are produced and transformed in the media. Hence, analyzing discourses in news media with critical discourse analysis in

particular can shed light on issues and power structures of a society (van Dijk, 2018, p. 466). Following this assumption, I am going to use Critical Discourse Analysis to explore answers

to my research question. More specifically, I am going to apply a socio-cognitive approach after van Dijk (2018), as his approach specifically aims at revealing power relations within a discourse in a society.

The data for this analysis consists of all major newspaper and magazine articles which have been published in response to the online petition. Since a Swiss-German word was discussed, only articles distributed in the German part of Switzerland were considered. In order to ensure the completeness of the data sample, the articles were not only collected on GoogleNews, but also by using Swissdox, Switzerland’s media archive. The data sample consists of 30 articles which were issued between 13 September 2017 and 29 September 2017.

Even though this debate took place almost two years ago, this study seeks to investigate the role of Swiss news media in racist discourses. It unfortunately remains a current topic, as recent events show. In August 2018, the facebook pages from two traditional “Guggenmusik” formations were blocked because of their names “Mohrenkopf” and “Negro-Rhygass”

(Wieland & Schwald, 2018). This sparked a great outcry (Wieland & Schwald, 2018) and refueled the discussion around tradition, culture and racism. There are several other artifacts ranging from coats of arms to names of cafés (see Krähenbühl, 2017c) that prove that

Switzerland was affected by colonial ideologies that spread in the 19th century and may start a

new discussion over again. This thesis also looks into the history of Switzerland and Swiss postcolonialism in order to understand where some of the argumentation comes from. These insights may be beneficial to the next discourse.

However, Switzerland is not the only country experiencing these clashes. Haribo, an

international confectionary company, agreed to redesign the packaging of their Skipper Mix licorices for the Swedish and Danish market, as it depicted Black and Asian people and artifacts in an imperialistic, racist way (Danbolt, 2017, p. 107). The backlash Haribo received for this step inspired Danbolt (2017) to further explore what he coined as “Retro Racism”. Retro racism refers to the justification and legitimization of racist names or goods for its historical or cultural value (Danbolt, 2017). There are many similarities between the Haribo’s Skipper Mix case and the “Schaumkuss” debate. For this reason, I see this current thesis not only as a contribution to the research of Swiss news media, but also to this discussion on commodity and retro racism.

Over the next few chapters, I will first explain the context in which the debate and later also the analysis is embedded in. Afterwards, I am going to elaborate the theories which will serve as a framework for the subsequent analysis. The analysis is conducted along a analytical framework based on van Dijk’s (2018) socio-cognitive approach to critical discourse analysis. Ethical concerns as well as the results from the analysis will then be addressed and discussed, which will hopefully lead to answers to all research questions.

2. Background

Before I begin with the contextualization of my research, I am going to lay out what a “Schaumkuss” is and where it came from.

A “Schaumkuss” is a chocolate covered meringue that sits on top of thin waffle. According to Hoff (2016), who published a book on the history of Danish chocolate, the origin of the candies can be traced back to Scotland, before they found their way to Europe in the early 19th

century. However, it took a little more than a 100 years, before the confectionary received its first entry in a Swiss cookbook (Kulinarisches Erbe der Schweiz, n.d.). This is half a century later than in Germany, which is why the name “Mohrenkopf” most likely originated in Germany and was adopted by Swiss people.

The debate over the name of “Schaumküsse” is not new. The first article about this debate found in Swiss media archives dates to 1992 and is already mocking intention to replace the name “Mohrenkopf” (GPD, 1992). Similar debates have been taking place in Finland, Germany as well as Denmark, where the candy also used to be called “Negerkuss” or “Negerkys” (engl. negro’s kiss), before it was changed to “Schaumkuss” and “Flødeboller” (Hoff, 2016; Kulinarisches Erbe der Schweiz, n.d.). In Switzerland, there were also multiple attempts to substitute the name “Mohrenkopf”, but it is needless to say that they were unsuccessful (Krebs, 2017).

The current Swiss debate was triggered by an online petition of a “Committee against Racist Candy”, a self-appointed collective who remained anonymous and silent after the publication

of the petition. The petition calls out Dubler, a Swiss candy manufacturer, who still calls his chocolate covered meringue “Mohrenkopf” (engl. “moor’s head”), despite the fact that other manufacturers are already selling their candies under an alternative name. The petitioners argue that the name, which dates back to colonial time, should be abolished (Komitee gegen rassistische Süssigkeiten, 2017). Their explanation is that the word “Mohr” goes back to the Greek word “moros”, which translates to “foolish” and “stupid”, as well as to the Latin word “maurus”, which translates to “black”, “dark” and “African” (Komitee gegen rassistische Süssigkeiten, 2017). Since this word is used together with “Kopf”, it becomes obvious that “Mohrenkopf” refers to a human body part (Komitee gegen rassistische Süssigkeiten, 2017). For this reason, they conclude that “Mohrenkopf” is a derogative description of a Black person’s head (Komitee gegen rassistische Süssigkeiten, 2017).

The committee also points out the usual reactions of Swiss people to the questionable name. They describe how the problem of language is trivialized, denied (in terms of “it has already lost its racist meaning”) and inverted (in terms of “the person pointing out racism is the bad guy”) (Komitee gegen rassistische Süssigkeiten, 2017).

Danbolt (2017) found similar reactions in the debate over Haribo’s Skipper Mix packaging and conceptualized it as retro racism, that is the displacement of racism for historical or cultural reasons. Hall (1999) argues that once the individual has identified with the ideology and assimilated the given role and knowledge, she or he becomes an “authentic author” of the ideology and its “ideological truths” (p.272). Given the strong reaction from the media and the public, this may indicate the level of efficacy of retro racism. However, I see two major differences between Haribo’s Skipper Mix case and the current “Mohrenkopf” case. First, Switzerland did not own any colonies (or at least not directly) and second, the discussion is not just about a product, but about the Swiss German language itself. For this reason, I am going to focus the contextualization around these two topics.

2.1 “Überfremdung”

Many studies date the origin of stereotypical images of Africans back to colonization (Efionayi-Mäder & Ruedin, 2017; Purtschert, Falk, & Lüthi, 2015; Rellstab, 2014). In Switzerland, racial discourses are also often found in connection with immigration. The

following brief excursion in Swiss history shows that immigration has always been seen as a threat to the Swiss identity and offers a plausible explanation why Switzerland does not always keep a welcoming attitude towards foreigners in general.

Switzerland has always been a confederation of different states. After its foundation in 1291 by the three “Ur-Kantone” (engl. founding cantons), further alliances resp. cantons joined the confederation. With the exception of the canton Jura, all cantons that represent Switzerland today were united in 1815 (Schmid, 2001, p. 125). These unions mainly emerged as a strategy against external threats and not because the cantons had cultural practices, religion or

language in common (Mottier, 2000, p. 5). For this reason, Switzerland is often referred to “Willensnation”, a nation by will (Zimmer, 2011, p. 758). The Swiss identity is not defined by “blood or language” (Hilty in Zimmer, 2011, p. 760), but rather by values, customs and commitment (Keller in Zimmer, 2011, p.758). In order to protect these characteristics, there were also pleads for “a certain degree of isolation from the outside world” (Hilty in Zimmer, 2011, p. 760), which relates to mechanisms of Othering.

In the late 19th century, Switzerland had to face a larger immigration for the first time

(Zimmer, 2011, p. 763). Swiss politicians claimed that the constitution from 1848 would not be able to cope with this circumstance, as it stated that anyone would be considered as a Swiss citizen, once that person was also a citizen of a Swiss canton (ibid). This rather loose

prerequisite was taken advantage of by the French and German citizens, who wanted to avoid military service during WWI (ibid). The constitutional article also applied to foreign workers who were in high demand due to the industrialization in Switzerland (ibid). These factors led to an increase in foreigners from 5.7% to 14.7% within 40 years (ibid). When the national census along with numbers about immigration were published in 1910, the term

“Überfremdung” (engl. over-foreignization) was conceived during the debates (ibid). It “presumed the existence of an organic national community whose character (Eigenart) had come under threat through foreign immigration.” (Zimmer, 2011, p. 766). This discourse of “Überfremdung” continued to be part of Swiss immigration politics until today (Rellstab, 2014, p. 112).

Othering and painting immigrants as an external threat can also be seen as a form of identity construction. According to Mottier (2000, p. 4), “national identities are narratives which are concerned with the drawing of boundaries between members of the nation and non-members,

between ‘us’ and ‘them’”. Hildebrand (2017) goes further and says that “a nation needs a counter-society in order to construct itself as a collective, which is why one has to think of a nation as a negative entity” (p. 27). This is especially true for Switzerland, which was founded as a confederation against foreign powers, such as Germany or France. Therefore, seeing immigration as an external threat did not only construct, but underpin the narrative identity of Switzerland (Mottier, 2000, p. 5). I see the story of Swiss national hero Wilhelm Tell as another example for this mechanism. Tell is not only famous for his accuracy in shooting an apple on top of his son’s head, but also for his resistance against the intruder, the powerful Habsburger. The same strategies of Othering also at play in the current debates on

immigration (Hildebrand, 2017; Mottier, 2000).

2.2 Postcolonial Switzerland

With the rise of capitalism and thereby commodity racism in the 19th and 20th century, racial

images and colonial views were disseminated through “advertisements, packaging, photography, film, literature (including children’s stories), exhibitions and museums“

(Purtschert et al., 2015, p. 294). Swiss companies were quick to adopt these codes and applied them to their own goods and marketing strategies (ibid.). In doing so, they reinforced the colonial mindset and white superiority (Michel, 2015, p. 422). Because of its familiarity with mechanisms of Othering, I suspect that Switzerland was especially receptive for this

dissemination of racist ideologies, which is termed by Anne McClintock (1995, p. 33) as commodity racism.

What differentiates Switzerland from (most of the) other countries affected by commodity racism, is the fact that Switzerland has never directly owned any colonies. For this reason, all involvement in colonial practices are denied. This view is widely shared within politics, news media, history classes and also everyday life (Purtschert, Lüthi, & Falk, 2012, p. 13), even though several books and studies have been published on Switzerland’s entanglement with colonial powers (see Fässler, 2005; Purtschert, 2008; Purtschert et al., 2015). In fact, the excuse of not having colonies can even be seen as a characteristic of Swiss postcolonialism (Purtschert, 2008, p. 170).

Purtschert et al. (2015, p. 293) also see Switzerland as a “colony without colonies”, since Switzerland was influenced by colonialism and inhabits and articulates similar colonial ideologies like those of other European colonial powers. Racism against black people

increased during colonialism (Efionayi-Mäder & Ruedin, 2017; Fässler, 2005; Michel, 2015; Purtschert, 2015). Before that time, racist ideologies circulated through travel reports or scientific journals which could only be accessed by the upper class (McClintock, 1995, p. 209). Stereotypical images from that time do still have a negative effect on black people living in Switzerland now – regardless of whether they were born in Switzerland or not

(Fröhlicher-Stines and Mennel, as cited in Purtschert et al., 2015, p. 298). However, due to the widespread denial of involvement in colonial practices, most of the population believe that there is no racism in Switzerland (Cretton, 2018, p. 843). A recent study published by the Bundesamt für Statistik (2019, p. 3), the Federal Statistical Office of Switzerland, showed that around 40% of the Swiss population do not see racism as a serious problem.

2.3 “Mundart” as part of the Swiss Identity

Mottier (2000, p. 6) identified three narratives through which the Swiss national identity is conveyed. While the narrative “Staatsnation” highlights values such as neutrality, democracy or federalism, “Volksnation” focuses on the differences in origin and race (Mottier, 2000, p. 6). Last, but not least, “Kulturnation” narratives are often used to “construct language, religion, traditions or customs as the essential ‘stuff’ of the nation” (Mottier, 2000, p. 6). These narratives reinforce the notion that language and the linguistic diversity of Switzerland are “crucial elements of national identity” (Mottier, 2000, p. 3).

Multilingualism was not always easy to maintain, particularly after the WWI divided the German and French part of Switzerland, leading to a trench (“Röstigraben”) that separates the two regions (Schmid, 2001, p. 128). This trench is still often used as an explanation when there is a noticeable difference between the German and French part, such as in the outcome of current elections (see Hildebrand, 2017, p. 202). The union of the different language groups gained more strength during a general strike in 1918 as well as with the increasingly dictatorial climate in Europe (Schmid, 2001, p. 128). I assume that in times of crisis, each linguistic part of Switzerland is reminded of its membership to the “Willensnation”. For this

reason, I also argue that this coherence is likely to support the construction of identity through linguistic diversity.

What also complicates the relationship between the four language groups is Swiss German or “Mundart”. While German is the official language, Swiss German is the spoken language used in everyday life (Schmid, 2001, p. 130). It is not only very different from German, but each German speaking canton also has a different dialect. As if German was not already hard enough to learn, Swiss German presents an even greater challenge. Van den Bulck & Van Poecke (2007, p. 222) state that the Swiss seized this opportunity and used Swiss German to construct their own collective identity and to establish an additional national boundary. Thus, seeing Swiss German as a national and cultural artifact, any attempts to change it can be perceived as a threat.

2.4 Racism in Switzerland

In their report on Switzerland in 2014, the European Commission against Racism and

Intolerance (ECRI) concludes that there are various positive developments in the fight against racism. These include strengthening action towards integration, constant low levels of racist violence as well as media concerns who have taken measures against hate speech. However, they also point out that Roma, Yenish and Black people are still suffering from racism and discrimination, which often derive from how they are represented in the media (European Commission against Racism and Intolerance, 2014, p. 9). A more recent study which focuses on racism against Black people specifically, arrived at the same conclusion (Efionayi-Mäder & Ruedin, 2017). According to the statements in the study, Black people are perceived more negatively than any other people of color. This is said to be traced back to colonial times. While all participants in this study stated that they would welcome a debate on “anti-Black racism”, the authors conclude that the majority of Swiss people would not see it as urgent. The latest numbers from the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (Bundesamt für Statistik, 2019, p. 3) similarly affirm that around 59% of the participants saw racism in general as a serious problem. However, that number has declined by 6% since the assessment two years ago. It also means that 40% of the participants do not see it as a serious problem.

This denial of racism has also been observed and studied by various researchers (Boulila, 2018; Cretton, 2018; Michel, 2015; Purtschert, 2008) and as mentioned before, it is seen as a characteristic of postcolonial discourses in Switzerland (Purtschert, 2008, p. 170). Both studies by Boulila and Cretton reveal the extent to which the denial of racism stretches. Boulila (2018) has shown that “official state anti-racist bodies” encourage the elimination of race in the fight against racism. This anti-racialism, however, is said to legitimize the denial of racism, since by the removal of race as a terminology, there are no more grounds left to fight racism (Boulila, 2018). Michel (2015) also assumes that the success of the right-wing party in Switzerland can be explained by their successful reproduction of raceless racism. Cretton (2018, p. 856), on the other hand, found that for immigrants in Switzerland, denial of racism can be seen as a part of the Swiss identity and create a sense of belonging to the Swiss community.

3. Literature review

This thesis investigates the response of Swiss news media to a debate over racism. This also entails the role of the news media in discourses of racism. For this reason, the literature review will first deal with previous research on the role of news media in Switzerland, before turning to the discourse in detail in the next chapter.

Häussler (2006) differentiates between two roles. The media may either take the role of a discourse transmitter or as a discourse participant (Häussler, 2006, p. 304). In his analysis of the Swiss mass media discourse on the role of Switzerland during WWII, he concluded that the Swiss mass media fell back into the role of a transmitter. He criticizes the media for missing the opportunity to seek a consensus. He sees this not only in critically questioning each position or presenting opposing voices, but also in exploring ways how a consensus would be possible given the different power relations. This would require a reflective aspect, which is why Häussler (2006) argues that a purely discursive analysis of how something or someone is represented is not enough (2006, p. 312). Thus, he supports the use of critical discourse analysis for investigating the role and response of Swiss news media. While Häussler (2006) examined the role of Swiss media in discourse of history, I will look at the role of Swiss news media in relation to racism.

In connection with racism, the role of Swiss news media is often broken down to how they represent minorities in their news coverage (Bonfadelli, 2007; Ettinger, 2018; Koch, 2009; Rellstab, 2014) and how this in turn effects minorities as well as attitudes toward minorities (Binggeli, Krings, & Sczesny, 2014; Schemer, 2012; Trebbe & Schoenhagen, 2011). These studies overlap in their criticism of the representation in terms of underrepresentation, negative contextualization and stereotyping.

Bonfadelli (2007, p. 95) state that a great share of the Swiss population does not have any personal experience or contact with foreigners. Therefore, representation becomes even more important since the portrayal of foreigners in the media is the only one they know. However, Trebbe & Schoenhagen (2011) found that while immigrants are overrepresented in negative frames, they are underrepresented in the portrayal of everyday situations in Swiss media. This implies that the Swiss population tend to have a more negative than positive attitudes towards

immigrants. Wirz et al. (2018) reinforces this suggestion, as they found out that “the more anti-immigrant messages individuals receive in their media diet, the more negative their cognitions toward immigrants will become” (Wirz et al., 2018, p. 501).

Trebbe & Schoenhagen (2011) pointed out, it is not only the quantitative representation of minorities, but also the qualitative representation that is questionable in Swiss news media. The qualitative representation contains contextualization and stereotypes. Ettinger (2018) analyzed contextualization by looking at how news reports on Muslims were framed. He found that episodic framing1 was evident in 84% of all news reports on Muslims, which

means more weight was given to the dominant parties (i.e. non-Muslims) in these news reports (Ettinger, 2018). Bekalu (2006) also saw a possibility to influence people’s knowledge in how news stories are presented in the context of different types of conflicts in Ethiopia. After analyzing journalists’ presuppositions, he came to the conclusion that unfair

presuppositions, which require more effort from the reader to understand the context, may lead to a different understanding of the news story. If this is done on purpose, it may indicate an attempt to disseminate ideological messages (Bekalu, 2006). Even though Bekalu (2006) did not conduct his analysis on Swiss news media, I suspect that an analysis of Swiss presuppositions would yield similar results.

Stereotypes are especially problematic, when they are generalized (Ettinger, 2018), because they are encourage practices of racial profiling (Efionayi-Mäder & Ruedin, 2017; European Commission against Racism and Intolerance, 2014). These generalizations also have a negative effect on minorities, as they are directly and indirectly confronted with them in their everyday life (Efionayi-Mäder & Ruedin, 2017; European Commission against Racism and Intolerance, 2014). According to Boomgaarden & Vliegenthart (2007), news media play a role in facilitating these generalizations by creating “a sense of in-group belonging and, accordingly, to out-group hostility” (p.518). An example of this is when the ethnicity of the person of interest is specifically mentioned in the context of an event or situation that does not necessarily require it. This links to mechanisms of Othering (Riggins, 1997).

1 Iyengar and Simon (1993, p. 369) differentiate between episodic an thematic framing. Episodic framing is used

to quickly draw a clear picture for the reader, while thematic framing is painting a broader picture, placing the framed issue in a context.

Given the literature review, I situate my thesis within the research of the role of Swiss news media in discourses of racism. However, as proposed by Häussler (2006), I will use critical discourse analysis to provide me with a more holistic view of the role of news media in Swiss society.

4. Theoretical framework

“Critical discourse analysis is far from easy. In my opinion it is by far the toughest challenge in the discipline. As suggested above, it requires true multidisciplinarity, and an account of intricate relationships between text, talk, social cognition, power, society and culture.” (van Dijk, 1993, p. 253)

In order to meet the requirement of multidisciplinarity, the present research touches upon theories that have originated from various fields of research as suggested by Wodak, de Cillia, Reisigl, Rodger, & Liebhart (2009). It is not the intention to explain each theory in detail, but merely to capture the essence of each theory, so that they will provide a solid framework for the analysis.

4.1 Discourse Theory

There are several definitions of ‘discourse’. Schiffrin, Tannen & Hamilton (2001) distinguish three categories for these definitions. For this paper, I am going to use their definition which they claim is widely used by Critical Discourse Analysts:

“Discourse of power or racism refers to […] a broad conglomeration of linguistic and nonlinguistic social practices and ideological assumptions that together construct power or racism” (Schiffrin et al., 2001, p. 1)

This definition also leads to discourse theory after Laclau and Mouffe (see Laclau & Mouffe, 2001), which builds on the notion that reality is constructed by discursive practices, which are exercised in everyday communication (Fairclough, Mulderrig, & Wodak, 2011; Farkas, Schou, & Neumayer, 2018; Hildebrand, 2017; Wodak et al., 2009). The goal of every participant group of the discourse is to achieve hegemony, that is to establish their

claim/perspective as true and/or good. This hegemony can be seen as a reached consensus among the participants. It also implies that the “defeated” groups not only accept the

dominant claim (and its views), but also support them on their own. (van Dijk, 1993). Thus, this concept may explain how social order and racism is enforced in society (Fairclough et al., 2011; Farkas et al., 2018; Hildebrand, 2017; Wodak et al., 2009).

According to (van Dijk, 1993), the dominant group may reinforce their power in a discourse by controlling the context and by controlling actions. The first means that the dominant party may choose the context, which then may already exclude or limit participation of other groups. Controlling actions implies that the dominant party restricts participation in a discourse. This is achieved by either simply not including the other party or by choosing a topic that the other party cannot talk about (van Dijk, 1993). This control can be exercised consciously or unconsciously by dominant individuals (van Dijk, 1993), so it is possible to observe both overt and inferential racism. However, both ways lead to underrepresentation and marginalization of the suppressed group, which are often minorities in racist discourses.

Discourse Theory also assumes that this influence works both ways. Discourses shape society, which again shape following discourses (Fairclough et al., 2011; Farkas et al., 2018;

Hildebrand, 2017; Wodak et al., 2009). This leads to the following conclusion: “all identities and discourses are treated as the outcome of contingent processes of inclusion and exclusion that reflect particular power relations in society at large” (Farkas et al., 2018, p. 467). This theory is also the foundation and starting point of Critical Discourse Analysis (Schiffrin et al., 2001), which is applied in this study and introduced in the next chapter.

4.2 Agenda Setting, Framing and Gatekeeping Theory

These theories essential to mass communication research particularly concerning media production and its effects on society. Since I am analyzing discourses within Swiss news media, these theories cannot be neglected. They will help me investigate the mechanisms behind these discourses, in terms of what is presented when and how to the public. Danbolt (2017) also underpins the importance of including the theory of framing: “While the media debates have been structured around the question of whether racialized things are racist or not, the framing of the question has usually ensured that the answer could only be dismissive” (Danbolt, 2017, p. 106).

Agenda Setting Theory assumes that mass media is able to influence the public agenda by raising awareness to certain issues (McComb & Shaw, 1972). It has been proven by numerous studies that issues that have been given more attention by the mass media are seen as more

important by the readers (Iyengar & Simon, 1993; Luo, Burley, Moe, & Sui, 2019; McComb & Shaw, 1972). This also implies that mass media hold great power in influencing political discourses and ultimately also political events (McComb & Shaw, 1972). Bonfadelli (2007) argues that mass media’s agenda setting function also serves as a “social integration

function”. By setting the agenda and offering “urgent” topics to talk about, the mass media would set a common ground for social and political discourses. At the same time, these topics would also create shape identities by (re-)presenting “values, lifestyles and identities of the members of the majority as well as minority group and interpreting events”(Bonfadelli & Moser, 2007, p. 96). Based on this point of view, analyzing salient arguments voiced in the debate by the Swiss news media may not only point me to the main discourses, but it may also shed light on the underlying power structures and presumptions regarding Black people in Swiss society.

Since the first study on Agenda Setting Theory by McComb & Shaw (1972), researchers are now differentiating multiple levels of agenda setting (Luo et al., 2019; McCombs, Shaw, & Weaver, 2014), whereas two approaches are especially of interest for this present thesis. The first level refers to the original study by McComb & Shaw (1972) and, as explained in the paragraph before, focuses on the salience of an issue that leads to a perceived importance of these issues. The second level focuses on the attributes with which an issue is presented in the media (Luo et al., 2019). The second level of agenda setting, which is considered to effect the public stronger than the first level, is also closely tied to the concept of framing (Luo et al., 2019). While some researchers even equate the second level of agenda setting with framing, others see it as an extension of agenda setting theory. Weaver (2007) sees the difference in their foundation. According to him, Agenda Setting Theory is primarily grounded in the theory of attitude accessibility, whereas Framing is based on Prospect Theory. This means that, in agenda setting theory, opinions and decisions are formed and made based on attributes that are continuously presented and connected with the issue, which are then easier and quicker to associate for the human brain. Framing, on the other hand, would imply that attitudes with which an issue is presented with leads to an active change in thinking (Weaver, 2007).

Gatekeeping theory has also been applied in a previous study of Swiss mass media by Wettstein, Esser, Schulz, Wirz, & Wirth (2018). However, this includes more than just selection, as the theory also covers decisions on how the news story is presented or when it is

published (Shoemaker, Eichholz, Kim, & Wrigley, 2001; Vos & Thomas, 2019). As a

consequence of this, journalists or news media hold a lot of power in a discourse. Shoemaker et al. (2001) also compare gatekeeping to how reality is constructed in the news media. On the other hand, gatekeeping can also be studied as a role which a journalist inhibits (Vos &

Thomas, 2019; Wettstein et al., 2018). However, the individual journalist may not decide freely on what news to pass on, as there are other factors, such as newsworthiness (Wettstein et al., 2018).

4.3 Retro Racism and Commodity Racism

The accusations made by “Committee against Racist Candy” in the online petition relate to ‘Commodity Racism’, a term conceived by Anne McClintock (1995), whereas the reactions to the petition can be classified as ‘Retro Racism’, a term coined by Mathias Danbolt (2017).

Commodity Racism describes racism that emerged during the times of imperialism and “converted the narrative of imperial Progress into mass-produced consumer spectacles” (McClintock, 1995, p. 33), and therefore imperial progress became synonymous with undermining the identity of “other races”. This could be seen in advertisements from soap companies or world exhibitions, such as the Great Exhibition in 1850 at the Crystal Palace (ibid.). These new forms of media enabled racist ideologies to travel much further and reach a great share of the population. Before commodity racism was prevalent, imperial ideologies and thoughts were mainly shared “in anthropological, scientific and medical journals, travel writing and ethnographies”, which is why they were only accessible to a limited number of people (McClintock, 1995, p. 209).

The difference between Commodity Racism and Danbolt’s (2017) ‘Retro Racism’ lies in what Danbolt (2017) calls “temporal logic” (Danbolt, 2017, p. 109). Retro racism refers to the negation of racism in commodities by justifying its historical origin and cultural value that inhabit the particular commodities. In the discussion about Skipper Mix candy, Danbolt (2017) also witnesses a desire to protect culture and refers to Philomena Essed’s (2013) work on “entitlement racism”, where racism is legitimized by freedom of expression. At the same time, Danbolt (2017, p. 109) was able to observe a sense of nostalgia in the debate, which can render the imperial and racist connotation of an object invisible. Moreover, criticizing “retro”

objects for its racist connotation can even be seen as a threat to a community that consumes these objects. In the process, the critic is marked as an outsider (ibid.). Therefore, Danbolt (2017) delivered the concept of retro racism which focuses on how people nowadays deal with commodity racism. Seeing the Swiss candy as a form of commodity racism because of its name, the concept of retro racism can be applied in the analysis of the media debate over it.

According to the “Committee against Racist Candy”, the name “Mohrenkopf” originated during the colonial times and carries a prerogative meaning for a Black person’s head. For this reason, the name of the candy can be categorized as a case of commodity racism, as it conveys the imperial idea of the appropriation of a Black person. The appropriation of a Black person’s head goes back even further than imperialism. Lowe writes that “many European families in the Middle Ages had incorporated Moor’s heads into their coats of arms, and others in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries had been allocated coats of arms that included Moors’ heads as a reflection of their involvement in the slave trade” (Lowe, 2013).

Switzerland also has coats of arms which show similar depictions, as a list by 20 Minuten revealed, which was (ironically) compiled as a legitimization of the name “Mohrenkopf” (Krähenbühl, 2017c). As discussed in Chapter 2, Purtschert et al. (2015) state that colonial ideologies and concepts, such as commodity racism, are also present in Switzerland, even though Switzerland did not have any colonies.

5. Methodology

The present thesis aims at answering the following research question and consequential subquestions:

How did the Swiss news media respond to the 'Schaumkuss' petition about racist candy? - What discourses emerged in the retelling of the debate?

- How did the newspapers position themselves?

- What does this coverage articulate about racism and race relations in Swiss society?

In order to investigate and expose discourses in the debate over the terminology of

“Mohrenkopf” or “Schaumküsse”, I will draw on Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), which constitutes another branch of Discourse Analysis. While Discourse Analysis may reveal how social practices are represented and how common knowledge is generated in a discourse, CDA goes one step further and critically questions these representations (Fairclough et al., 2011; van Leeuwen, 2018). Thus, a discourse analysis may answer sub-questions about discourses as well as the positioning of the Swiss news media. However, CDA is crucial to find answers to the sub-question regarding racism and race relations in Swiss society as well as to critically and holistically answer the main research question.

Unlike Discourse Analysis, CDA calls for an alignment of the researcher with the underprivileged social group (Fairclough et al., 2011; Wodak et al., 2009). Gaining their perspective allows Critical Discourse Analysts to question discursive strategies which reproduce dominance by legitimating or naturalizing control, social order or inequality (van Dijk, 1993).

There are numerous approaches to Critical Discourse Analysis, as illustrated by Fairclough et al. (2011). What unifies them – apart from their roots in Discourse Theory – is their aim to critically question subliminal, naturalized discourses and revealing underlying power

structures and ideologies (Bauder, 2008; Fairclough et al., 2011; Teo, 2000). Therefore, CDA also appears to be a competent analytical framework to investigate retro racism in discourses,

as suspected in the “Schaumkuss” debate. As argued in the previous chapter, retro racism has promoted, justified and naturalized racist and imperial ideologies.

5.1 Socio-Cognitive Approach

Like other approaches to CDA, the socio-cognitive approach builds on the notion of social power (van Dijk, 2018). However, he sees social power as control (van Dijk, 2018). The more social power a participant has, the more control she/he has to exert in a discourse to

(re)produce dominance and power (van Dijk, 1993). This exercise of control occurs in the production as well as reception of discourses (van Dijk, 1993).

This approach has proven to be a qualified instrument to analyze power relations and racist discourses in particular (see Häussler, 2006; Teo, 2000; van Dijk, 1988). I am confident that it will also be a competent approach for the present thesis, given that my research objective also includes the positioning of Swiss news media in racist discourses, which also entails

investigating their power relations.

In order to structure the analysis, van Dijk (2018) differentiates between a macro and micro level. Macro-level covers structures, institutions and organizations within a society, while micro-level refers to agency and interactions (van Dijk, 2018). In CDA, an analysis of the macro level includes looking at the participants of a discourse with a special regard to preferential access and power relations. Consequently, an analysis on a micro level means investigating language and discourses.

5.1.1 Production and Control of Public Discourse

Dominance can be enacted by controlling a discourse (van Dijk, 1993). Control over a discourse can be exerted by controlling access to a discourse, such as excluding (less

powerful) people from a group (van Dijk, 1993). A less obvious access limitation may follow from choosing a topic that automatically leads to the exclusion of certain groups (van Dijk, 1993). The inclusion of this parameter in the analysis will uncover whether or not there is a participant in the debate who exerts more control and therefore, holds more social power in Swiss society.

5.1.2 Mind Control

When social power is influencing the reception of discourses, van Dijk (2018) refers to it as mind control. Van Dijk (2018) understands that each individual has a mental model and a contextual model, which allow for a social life.

An individual needs mental models to make sense of discourses and thereby, reality (ibid 2018). They are based on personal experiences and memories (van Dijk, 2018). Every experience leads to either confirming and reinforcing, or objecting and renegotiating mental models (van Dijk, 2018). Thus, if a participant intends to disseminate racist ideologies, “discourse properties must be geared towards the production or activation of an episodic mental model about ethnic minorities, in such a way that this model will in turn confirm negative attitudes and ideologies in the audience” (van Dijk, 1993, p. 263). In the case of the “Schaumkuss”-debate, the opponents of the name change would try to influence the mental model about people advocating for a change. By doing so, they also disseminate retro racism. Contextual models represent the context in which the experience or discourse is embedded in (van Dijk, 2018). A context model provides the individual with “properties of the discourse”, such as speech acts or politeness, that are important to understand these discourses (van Dijk, 2018). Thus, a context model also determines how likely the message of a discourse is to be accepted. Van Dijk also identifies four contextual conditions that lead to a better reception (van Dijk, 2018):

- the content comes from a trustworthy source,

- the content has to be accepted, e.g. in school or at work, - there are no other sources, or

- they lack the knowledge to question the message

(van Dijk, 2018).

5.2 Analytical Framework

Following the socio-cognitive approach to CDA by van Dijk (1993), I am going to analyze both dimensions of control, that is the control of public discourses and mind control, on a micro and macro level. In order to do so, I created a grid based on the socio-cognitive approach for each level, which will serve as an analytical framework (see Table 1 and 2). A

grid will not only act as a guideline in the examination of each article in the data sample, but also allow for a better comparison of the articles. As proposed by van Dijk (1993), I will begin with investigating the macro level, before having a more detailed look at the micro level. The findings will be presented in Chapter 7 and discussed in Chapter 8.

5.2.1 Macro-level Analysis

The parameters for the analysis are based on van Dijk’s (1993, 2018) approach and were adjusted to meet the needs of this study. In contrary to van Dijk (1993), “speech act” is not part of the analysis, as the present data sample does not include any speeches. The grid for the macro-level analysis contains criteria listed in the left column and the two dimensions of control in the first row (see Table 1). Based on this framework, I developed questions, that will guide my analysis of each article. The parameters as well as the derived questions will be discussed in the following paragraphs.

Table 1 - Grid for macro analysis of control

Analysis on Macro-level

Control of Public Discourse / Production

Mind Control / Reception

Setting What access is predetermined by the setting?

What contextual conditions are given by the setting?

Genre What access is predetermined by the genre?

What contextual conditions are given by the genre?

Participants Who has access to the debate and who does not?

Any participants in the discourse that enjoy authority or more trust than others?

Topics Who sets the agenda and who can change it?

How are topics framed in the headlines and leads?

Setting & Genre

Both parameters “setting” and “genre” investigate the “starting positions” of the participants in the discourse. Therefore, they aim at revealing any preferential treatment of the dominant group, which led to a restricted participation of others, and at responding to the same

questions.

On the discourse production-side, I am therefore interested in what setting and genre the discourse is embedded in, as certain settings and genre automatically lead to an exclusion or preferential access, which is considered as a crucial power resource by itself (van Dijk, 1993, p. 259). Apart from analyzing the genre of news media, I will also take into account the different type of articles, such as news articles, commentary, interview and news flashes.

On the discourse reception-side, I am going to check for contextual conditions that work in favor of the dominant group. As elaborated before, people are more likely to accept a message, when certain conditions are given. Since different genres and type of articles have different impact on people’s reception (Machin & Mayr, 2012), I am also interested in the contextual conditions that originate from different genres.

Participants

This parameter accounts for all participants of the discourse as well as their roles and relations to each other. This sheds light onto underlying power structures and inequalities. Analyzing participants must also include an analysis of absent groups, as another straightforward way to claim dominance over a discourse is by excluding people from the discourse (van Dijk, 1993).

In regard of mind control, I will focus on the identity and role of each participant. These roles may convey authority or another trustworthy attribute. Quotes from these individuals or groups are then perceived as more credible (Riggins, 1997, p. 12).

Topics

Another straightforward way to control a public discourse is by choosing a topic. Submissive groups are then forced to either participate in a discourse on this chosen topic or to exclude themselves from the discourse (van Dijk, 1993). Either way, their freedom of choice is limited (van Dijk, 1993). Therefore, this parameter focuses on who is in charge of setting and

changing a topic in the “Schaumkuss”-debate.

Topics are usually introduced in headlines and leads, which is why I will focus on them in the analysis of mind control. According to (van Dijk, 2018), the way these topics are presented in the headlines and leads have already an impact on the attitude towards these topics, as they activate certain mental models.

5.2.2 Micro-level Analysis

I start my micro-level analysis with investigating the Swiss news media response on a Micro level. This consists of analyzing the text structures of all articles in the data sample. For this investigation, I draw on the discursive strategies by Jiwani and Richardson (2011). Based on these strategies found in their examination of racist discourses, they formulated five

questions, which I borrowed to guide me through the examination of my data sample. They are aligned with the dimension of control of public discourse as they address the production of the text.

However, control of public discourse and mind control are tightly interwoven on the micro-level. Every lexical choice in an article has implications for reception by the audience

(Machin & Mayr, 2012). Therefore, the choice of strategies not only implies control of public discourse, but also influences mental and contextual models. In order to gain more insights on how mind control is exerted on a micro-level, I am also going to refer to the theoretical framework established in Chapter 4.

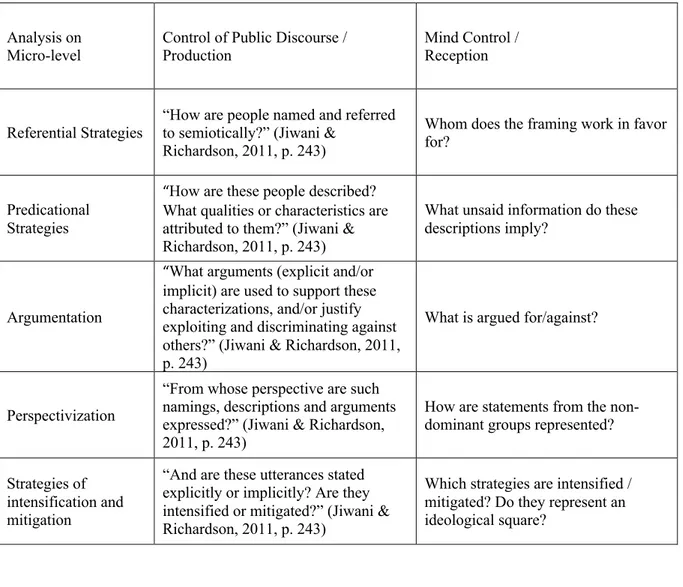

Table 2 - Grid for micro analysis of control

Analysis on

Micro-level Control of Public Discourse / Production Mind Control / Reception

Referential Strategies “How are people named and referred to semiotically?” (Jiwani & Richardson, 2011, p. 243)

Whom does the framing work in favor for?

Predicational Strategies

“How are these people described? What qualities or characteristics are attributed to them?” (Jiwani & Richardson, 2011, p. 243)

What unsaid information do these descriptions imply?

Argumentation

“What arguments (explicit and/or implicit) are used to support these characterizations, and/or justify exploiting and discriminating against others?” (Jiwani & Richardson, 2011, p. 243)

What is argued for/against?

Perspectivization

“From whose perspective are such namings, descriptions and arguments expressed?” (Jiwani & Richardson, 2011, p. 243)

How are statements from the non-dominant groups represented?

Strategies of intensification and mitigation

“And are these utterances stated explicitly or implicitly? Are they intensified or mitigated?” (Jiwani & Richardson, 2011, p. 243)

Which strategies are intensified / mitigated? Do they represent an ideological square?

Referential Strategies

According to Jiwani & Richardson (2011), racist discourses no longer rely on overtly racist terms. Nowadays, racist discourses rather use a more subtle language to discriminate others. This is also valid for how minorities are referred to in public discourses, especially because they are often depicted using negative language (Jiwani & Richardson, 2011). According to Reisigl and Wodak (2001), the use of rhetoric figures such as metaphors, metonymies, as well as synecdoches for generalizations in particular fosters an inferior image of others. Using and establishing stereotypes in discourses can also be categorized as a referential strategy. Thus, I am interested in how participants are referred to by the Swiss news media in order to uncover any hidden intentions and also go after the question, who profits from these references that influence our mental models.

Predicational Strategies

These strategies are closely related to referential strategies. Words that are chosen for describing a subject or action may already imply certain information (Jiwani & Richardson, 2011) and activate certain mental and contextual models. These strategies are often used to create certain presuppositions and reflect what a journalist believes is shared common knowledge and conduct (Bekalu, 2006).

This is why predicational strategies are also interesting for this paper. Having a closer look at how a subject or action is described by Swiss journalists may lead to uncover unfair

presuppositions, which in turn hint at hidden ideologies. Referring to the different dimensions of control, the analysis of control of public discourse focuses on what words have been used to describe any actions, whereas the analysis of mind control concentrates on the use of unfair presupposition.

Argumentation

While there is extensive literature on argumentation strategies, models and how to study them (see Bauder, 2008; Eemeren, Jackson, & Jacobs, 2011), I am focusing on what arguments are actually used to justify or legitimize the use of the word “Mohrenkopf”. This grounds on the work by van Dijk (2018), Wodak (2018) and Reisigl (2001), who list justification and legitimization as one of the main argumentation strategies to reproduce dominance. I am referring to Danbolt’s (2017) work in particular, which shows that these strategies are also typical in discourses on retro racism. Based on Danbolt (2017), I argue that retro racism is conveyed in arguments and (re)produced when

- history and culture are used for justification,

- freedom of expression is used for legitimization, and/or - commodity racism is neglected.

Arguments that are produced in a discourse are directly aimed at changing mental models. For this reason, I am not going to differentiate between the “production” and “reception”

Perspectivization

This aspect concentrates on quotation patterns. When a public discourse is dominated by a group, minorities suffer from marginalized representation in the discourse, as their access to the discourse is restricted. This also leads to a very one-dimensional perspective of a given topic, as the dominant group is able to share their point of view more than others (Jiwani & Richardson, 2011).

After I have analyzed the quotation patterns on the production side, I am also going to

determine, how quotes from the “other” group are represented by the Swiss news media. This will provide me with information about how voices from the ‘other’ groups are seen and treated.

Strategies of intensification and mitigation

This strategy refers to how events or actions are described. Racist discourses often contain intensified expressions of events or actions to emphasize the wrong doing of others (Jiwani & Richardson, 2011). The intensification also aims at emotionalizing the news and thereby, create negative attitudes towards the “out-group” (Reisigl & Wodak, 2001). This is often observed in populist language (Wirz et al., 2018). Hodkinson (2017) also refers to these exaggerations as creating a “moral panic”.

The strategy can also work in the other direction. Mitigation techniques are usually used in racist discourses to describe good actions by “others” as well as to downplay bad actions by the dominant group. Van Dijk (2018) speaks of an ideological square: “Emphasize Our good things, emphasize THEIR bad things, mitigate Our bad things, mitigate Their good things” (van Dijk, 2018, p. 474). He also refers to this tactic as the general strategy in racist

discourses to (re)produce dominance (van Dijk, 2018).

As suggested by Reisigl and Wodak (2001), I will look for particles that hint at intensification or mitigation, such as “very”, “really” or “doubtfully”, to name a few (2001, p. 83), in order to determine whether I am dealing with exaggeration or mitigation.

5.3 Data Sample

As outlined in the introduction, the data for the following analysis consists of event-based newspaper articles. It would have certainly been interesting to analyze the audience’s reaction to the news media coverage as well as to compare them, as it has been demonstrated in a previous study by Rellstab (2014). However, due to dimensions of this outcry, this would have resulted in analysis of an immense set of data, which would have exceeded the scope of this thesis. Furthermore, by prioritizing a profound analysis to a broad analysis, I also chose to focus on written news media and exclude TV and radio reports. The data was limited to German media texts, as the debate evolved around a (Swiss) German word.

These constraints led to a sample consisting of all texts covering the “Schaumkuss”-petition, which were published between September, 13, 2017 and September, 29, 2017. This represents the period between the publication of the first article about the online petition and the

publication of the last article which can be directly linked to the debate. The data was

collected on GoogleNews and on Swissdox, Switzerland’s media archive. Over the two week-period of interest, Swiss news outlets published 40 media texts online and offline. Among the found data sample were also letters to the editor which were excluded from the analysis, as the focus of the study lies on texts which were produced by the media.

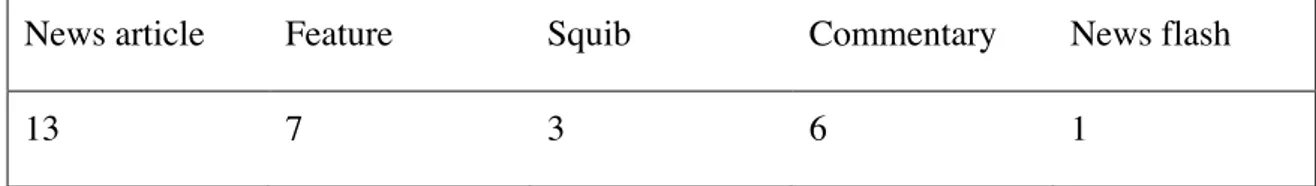

The remaining sample of 30 media texts include news articles, features, opinion pieces (commentaries and squibs) as well as news flashs, which were published in 19 different newspapers and online magazines.

Table 3 - Type of Articles present in the Data Set

News article Feature Squib Commentary News flash

13 7 3 6 1

The story about the petition also made it on the cover of “20 Minuten”, Switzerland’s tabloid with the highest reach (Bundesamt für Statistik, 2018). Some articles may have been

published in different newspapers and magazines, as they are owned by the same publishing house. At the same time, many news outlets published more than one article on the topic, which were available either online, offline or both. Articles which were published offline

only, were gathered on Swissdox. Unfortunately, the articles were provided without their original layout. For this reason, I no longer differentiated between on- and offline

publications.

Table 4 - Data Sample

Type of Media Publication

Amount of articles published offline Amount of articles published online Amount of articles published offline & online Quality Tages-Anzeiger2 2

Neue Zürcher Zeitung 1

Regional

Newspaper Aargauer Zeitung 3 3 Basellandschaftliche Zeitung 1 Basler Zeitung 1 Bündner Tagblatt 2 St.Galler Tagblatt3 1 Tabloid 20 Minuten 6 2 Blick 1 1 Blick am Abend 1

Weekly Die Weltwoche 1

Die Wochenzeitung (WoZ) 1

Schweiz am Wochenende 1

TagesWoche 1

Online

publication Vice - 1 -

Total news articles published 6 12 12

2 Same article was also published in Berner Zeitung, Der Bund and Newsnet 3 Same article was also published in Thurgauer Zeitung

5.4 Limitations

The main limitation of this methodology refers to the exclusion of visual analysis. According to Wodak & Reisigl (2018, p.580), strategies of Othering are especially prevalent in the media. The layout, space as well as the illustration or photograph chosen to illustrate the article could have provide more insights. However, I refrained from conducting a visual analysis, as the original layout for most of the articles were not available as well as for the limited scope of the thesis.

Another limitation I see in the methodology is that the socio-cognitive approach to CDA fails to account for the factor of reach. It soon became clear, that reach is another power resource, since the more people these strategies reach, the more effective they are in reproducing power and establishing dominance. Furthermore, the socio-cognitive approach does not account for newspapers who publish more articles than the average. This may lead to a potential bias in the results of the micro-level analysis. Therefore, strategies examined on a micro-level could be adjusted for the reach of each newspaper as well as for the number of publications in a newspaper to allow for a more insightful comparison and conclusion. Since this thesis is first and foremost interested in how the Swiss news media responded to the petition, these

6. Ethics

As elaborated in the beginning of the previous chapter, critical discourse analysis asks for taking the perspective of the minority group. Growing up as a person of color in Switzerland, this requirement did not seem to present a challenge at first. However, because I grew up in Switzerland, I had to realize that I was not immune to denial of racism either. This led me to question the blurry lines between political correctness and traditional, cultural artifacts several times. At the same time, this once again made me aware of the sensitivity of the topic. The challenge of this topic already presents in terminology and how to refer to Black persons. Lowe (Lowe, 2013) uses Black African, but distances herself immediately from the label of “black” 38. While I also distance myself from the label, I first chose to align myself with other researchers and use “Black person.

Another consideration includes the use of the word “Mohrenkopf” along with other racist terminologies. Whenever possible, I tried to use alternative descriptions. However, there are several paragraphs in which the use of these words was necessary to understand the message (better).

Despite being a native Swiss German speaker, another concern relates to my lack of previous experience with coding. However, I am confident that the analytical framework proved to be a competent device to address both concerns. It helped me keeping my focus on the relevant parts of my analysis.

The data considered in this analysis consist of articles that were publicly available or available through Swissdox, the Swiss media archive. Therefore, the usage of these articles for this analysis is appropriate and does not violate any copyright laws. However, one could argue that all articles may reveal the personal and social cognition of the author, which is why the journalist would need to consent to his participation in this study. Following a

consequentialist approach to ethical standards after Collins (pp.82-83), I chose not to ask for consent. I argue that journalists have already given their consent to share their work with the public, which includes the possibility of media research, once the article was published. Furthermore, the exclusion of a news article would compromise the validity of the thesis, as it would no longer represent the whole response of the Swiss newspapers to the ‘Schaumkuss’-debate. Since no visual analysis, interviews or surveys were conducted, no further privacy or consent issues need to be addressed.

7. Results from the analysis

In this chapter, I am going to present my results from the analysis conducted following the analytical framework. The implications of these results are then discussed in the next chapter.

7.1 Macro-level Analysis

For the sake of clarity, I am going to discuss the participants of the debate first, before I continue with other parameters.

7.1.1 Participants

Participants in the “Schaumküsse”-debate can be broadly divided into two ideological

positions: advocators of the petition support a change of the name, whereas opponents prefer the old name.

Advocators

The naming debate started with a group of advocators who formed a committee against

racist candies. The “ad hoc” in front of their signature, with which they signed the online

petition, implies that the committee was founded specifically for this cause. However, their individual members remained silent during the course of the public discussion. Furthermore, apart from the petition on change.org, it seemed neither possible to contact them, nor to gather more information about them and their cause. For this anonymity, I assume that they suffered a loss in their credibility, which did not benefit their cause.

Advocators were therefore represented by various individuals during the discourse. Most present in the debate were Dr. Franziska Schutzbach, a gender studies researcher, Brandy

Butler, musician and activist, Gülcan Akkaya, Vice-President of the Federal Commission

against Racism, and Celeste Ugochukwu, President of the African Diaspora Council of Switzerland. Their occupations already indicate a certain level of authority, which, according to Wodak (QUE), makes them more credible to the readers. However, when represented in Swiss news media, they were not entirely free to express themselves in the discourse, since it was journalists who decided whether or not to give them a voice. Since a few newspapers

used some quotes from them to justify the name “Mohrenkopf”, it seems as if some

journalists even took advantage of the level of credibility these advocators have. This raises questions in regard to the neutrality of journalists in reporting. I will have a look at the quotes in more detail in the micro-level analysis (see Chapter 7.2.4. Perspectivization).

Opponents

The main person in the debate, who represented opposition to change was Robert Dubler, the owner of the company Dubler AG, who produces the candies. As he was the primary recipient of the online petition, he was the first person to comment on it for the media. Dubler

successfully took over the family business which was founded in 1946 (Breitschmid, 2019). The media also characterized him as an unpretentious, but stubborn Swiss man, who was only minding his own long-established family business with no bad intentions at all, and who is all of a sudden finding himself as victim in a defensive position.

Furthermore, the name change is motivated and supported by people who want to fight racism against Black people. However, given the racism in Switzerland and the concept of Post-colonial Switzerland (as elaborated in Chapter 2), I assume that Black people are still seen as foreigners. For this reason, the petition can also be seen as a threat to the Swiss culture and plays into the fear of over-foreignization, as it wants to remove a word from colloquial Swiss vocabulary in order to create a more tolerant atmosphere towards “foreigners”. This leaves Dubler as the defender of not only his long-standing family business, but also of Swiss

culture. This representation is similar to Wilhelm Tell, the Swiss freedom fighter and national hero, who managed to successfully defend himself and his home country against the

Habsburger, who at that time invaded and occupied large parts of Switzerland, by shooting an apple on top of his son’s head amongst other things. For these reasons, I suspect that a lot of people were able to relate to him and were more inclined to sympathize with him.

Another major opponent to the name change was the “Junge SVP”, the Junior party of the Swiss right-wing party SVP (engl. Swiss People’s Party). They supported Dubler with a public action and gave away over 1000 pieces of Dubler’s candies. While a political agenda can be suspected, Dubler clearly distances himself from any political parties.

Swiss news media

Based on the articles published in the present debate, a majority of Swiss news media

demonstrated solidarity with Robert Dubler and argued against the change of the name. Even though professional journalism expects a high level of objectivity, journalists also have their own personal and social cognition including ideologies they follow. Therefore, some

journalists may take advantage of their control of discourse to (re)produce their ideologies. Bekalu (2006) notes, this may happen intentionally or unintentionally. Thus, the negative reporting on the petition hints at a (sub)conscious alignment with the opponents of the petition.

In addition, I would like to highlight two newspapers whom I attribute major roles in the discourse to: Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ) and 20 Minuten. Even though the discussion of the appropriateness of the name “Mohrenkopf” was brought to the table by the committee against racist candies, it was for Switzerland’s largest quality newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung

(NZZ) and Switzerland’s largest tabloid 20 Minuten that the debate became a public

discourse. NZZ was the first newspaper to comment on the petition (see Grob, 2017). This story was picked up by 20 Minuten (see Krähenbühl, 2017b), who decided to make it a cover story the next day. I argue that it was the cover story that raised so much attention to the petition. With six online articles and 2 printed articles, 20 Minuten was also the newspaper who published the most content. This proves the capability of NZZ and 20 Minuten to set the agenda of public discourse.

This brings me to the role of journalists and the Swiss newspapers in particular. They act as gatekeepers, as they decide on which story to publish and how. The “how” refers to framing a topic and also includes the choice of who to quote or interview. While I will discuss these aspects in more detail in my micro-level analysis, I would like to focus on the social power of the Swiss news media in a discourse here. NZZ introduced the petition with a commentary that argues strongly against a name change and frames it as “fight for an allegedly politically correct language” (Grob, 2017). Afterwards, only a few journalists managed to offer new perspectives on the petition and address its aim of reducing racism in Switzerland. This reflects the control the Swiss news media or NZZ holds over the discourse. According to Van Djik (1993, 2018), this control over a discourse can be seen as social power.