Examen: Kandidatexamen 180 hp Examinator: Maria Engberg

Huvudområde: Medieteknik Handledare: Henriette Lucander

Datum för slutseminarium: 2021-01-14

Examensarbete

15 högskolepoäng, grundnivå

Communication, collaboration and

belongingness in virtual teams

– mapping out enablers and constraints

Kommunikation, samarbete och tillhörighet i virtuella team

– en kartläggning av möjliggörare och begränsningar

Abstract

In an increasingly digital world, virtual work becomes more common every year. Additionally, virtual work has suddenly become the reality for a large part of the world’s population due to the coronavirus pandemic. Therefore, a study on virtual teamwork is currently of high

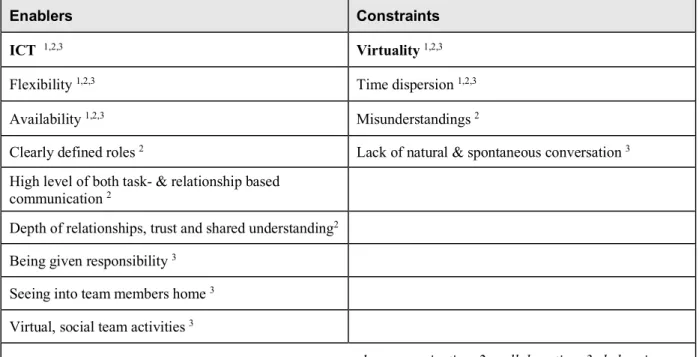

relevance. The purpose of this study is to gain a deeper understanding and provide knowledge on enablers and constraints for communication, collaboration and belongingness in virtual teams as well as ICTs impact on the virtual teamwork. The study has a phenomenological research design with a qualitative approach. Empirical data has been collected by studying three transnational, virtual teams by conducting six semi-structured individual interviews. The sample was selected through a strategic selection. A thematic analysis has been conducted to compile and analyze the data, which thereafter has been set in relation to the theoretical framework of the study. The enablers found in the results were flexibility and availability for communication, clearly defined roles, high level of both task- and relationship based communication as well as depth of relationships, trust and shared understanding for collaboration, and responsibility, seeing into team members homes and virtual social team activities for belongingness.

Additionally, ICTs were found as a main enabler for all themes. The identified constraints were time dispersion for all three themes, as well as virtuality as a whole. Additionally

misunderstandings was identified for collaboration and lack of natural and spontaneous social conversation for belongingness. Furthermore, the findings implicate that ICTs with

characteristics of richer type in relation to media richness are preferred most of the time to enable a better virtual work climate regards to communication, collaboration and belongingness. However, some criteria for media richness cannot be fully utilized in virtual teams due to time dispersion. Lastly, findings implicate that the choice of ICT based on previous experience, rather than linked to suitability, might hinder an optimal model of ICT usage for a well-functioning virtual team.

Keywords

Sammanfattning

I en allt mer digitaliserad värld blir virtuellt arbete vanligare varje år. Virtuellt arbete har dessutom hastigt blivit verklighet för en stor del av världens befolkning på grund av

coronapandemin. Därför är en studie om virtuellt teamarbete av hög relevans i dagens samhälle. Syftet med denna studie är att få en djupare förståelse och ge kunskap om möjliggörare och begränsningar för kommunikation, samarbete och tillhörighet i virtuella team samt ICTs inverkan på virtuellt teamarbete. Studien har en fenomenologisk forskningsdesign med ett kvalitativt tillvägagångssätt. Empirisk data har samlats in genom att studera tre transnationella, virtuella team genom genomförandet av sex semi-strukturerade, individuella intervjuer.

Intervjupersonerna valdes ut genom ett strategiskt urval. En tematisk analys har genomförts för att sammanställa och analysera data, som sedan satts i förhållande till det teoretiska ramverket för studien. De möjliggörande faktorer som hittades i resultaten var flexibilitet och

tillgänglighet för kommunikation, tydligt definierade roller, hög nivå av både uppgifts- och relationsbaserad kommunikation och relationsdjup, förtroende och delad förståelse för samarbete, samt ansvar, att få en inblick i teammedlemmarnas hem och virtuella sociala

teamaktiviteter för tillhörighet. Dessutom identifierades ICT som en övergripande möjliggörare. De identifierade begränsningarna var tidsskillnader för alla tre teman samt virtualitet i helhet. Utöver detta var missförstånd identifierat för samarbete och brist på naturlig och spontan social interaktion för tillhörighet. Dessutom visar resultaten på att ICTs med egenskaper av rikare typ i förhållande till media richness oftast föredras för att möjliggöra ett bättre virtuellt arbetsklimat när det gäller kommunikation, samarbete och tillhörighet. Vissa kriterier för media richness kan dock inte utnyttjas fullt ut i virtuella team på grund av tidsskillnader. Slutligen visar studiens resultat på att val av ICT baserat på tidigare erfarenhet, snarare än kopplat till lämplighet, kan hindra en optimal modell för användning av ICT för ett väl fungerande virtuellt team.

Nyckelord

Preface

This study is a bachelor thesis in Media Technology, written by Saga Fristedt in fall 2020 within the program Project Management within Publishing at Malmö University. The study is about enablers and constraints for virtual teamwork, which has been very interesting to write about due to the fact that virtual work, due to the coronavirus pandemic, has become most people’s reality during the year of 2020.

With an ongoing pandemic and a parallel (virtual) internship, the road here has not been completely straight. I would like to thank my exceptional supervisor, Henriette Lucander, for being very supportive and for giving great advice throughout the whole process. Furthermore, I would like to thank all respondents for their contribution to the result, and for taking their time to help me conduct this study.

Malmö, 2021-02-05

Table of Contents

1

Introduction... 1

1.1 Purpose ... 3

1.1.1 Research Questions ... 4

1.2 Target group ... 4

2

Research Overview & Theoretical Framework ... 5

2.1 Virtual teams ... 5

2.1.1 The usage of ICT in virtual teams ... 6

2.2 Media Richness Theory ... 7

2.2.1 Media richness in virtual teams ... 9

2.3 Crucial factors of virtual teams ... 10

2.3.1 Communication in virtual teams ... 11

2.3.2 Collaboration in virtual teams ... 12

2.3.3 Belongingness in virtual teams ... 13

3

Method ... 14

3.1 Research approach ... 14

3.1.1 Study design ... 14

3.2 Research setting ... 15

3.3 Data collection ... 16

3.3.1 Selection / Sampling process ... 16

3.3.2 Interviewing process ... 18 3.4 Data analysis ... 19 3.4.1 Thematic analysis ... 19 3.5 Ethical considerations ... 20 3.6 Quality of study ... 20

4

Results ... 23

4.1 Communication ... 23 4.2 Collaboration ... 25 4.3 Belongingness ... 26 4.4 ICT ... 28 4.5 Opportunities ... 325

Discussion ... 33

5.1 Enablers for virtual teamwork ... 33

5.1.1 Communication ... 33

5.1.2 Collaboration ... 34

5.2 Constraints for virtual teamwork ... 36

5.2.1 Communication ... 36

5.2.2 Collaboration ... 37

5.2.3 Belongingness ... 37

5.3 Interdependency between enablers and constraints ... 37

5.4 Effects of enablers and constraints ... 39

5.5 ICT ... 40

5.5.1 Media richness of ICTs... 40

5.5.2 Preferences and usage ... 41

6

Conclusion ... 43

6.1 Limitations and suggestions for future research ... 44

References ... 45

List of tables and figures

Figure 1. Communication Media and Information Richness (based on Daft & Lengel,

1984) ... 8

Table 1. Respondents mapped out in relation to their teams ... 18

Table 2. ICT usage in the teams ... 28

Table 3. Enablers and constraints for virtual teamwork ... 38

1

1

Introduction

In an increasingly digital world, with rapid globalization, environmental changes and collaboration technology development, virtual work has been an upcoming trend for the last couple of decades (Samul & Petre, 2019; Felstead & Henseke, 2017). According to Flexjobs (2019), the American remote workforce grew 159% between 2005 and 2017. However, the coronavirus pandemic has sped up the development of virtuality in our daily lives and has heightened the need for companies to adopt digital business models to allow teams within the organization to continue “business as usual”, even though stay at home orders heavily has affected workers all over the world (McKinsey, 2020). Due to the fact that only about 2% of employees in Europe worked from home in 2015 (Eurofound, 2017) and only 3,4% of Americans had remote working experience on a 50% activity grade or more before the

pandemic (Flexjobs, 2020), it is understandable that there are concerns about how a virtual work climate will work out within organizations, both temporarily and in the long run (PwC, 2020). Due to the rapidly increased trend of virtual work as an effect of the current coronavirus pandemic, the need for more up to date research within the field is crucial (Zeuge et al., 2020).

Since the birth of the internet, almost all teams use some kind of technology in their work, meaning they are all virtual to some extent (Gibson & Cohen, 2003). Within the field, several terms are frequently used to describe the same phenomenon and there are several definitions of a virtual team. However, most seem to agree on main characteristics such as that a virtual team is a group of individuals interdependent in their tasks with a shared responsibility for outcomes who are dispersed over time and/or location and use a range of communication technology to accomplish their tasks (Gibson & Cohen, 2003). Virtual teams will in this study be defined as fully dispersed, relying on a fully virtual work model with no face-to-face interaction between any team members, thus, teams with a limited extent of virtuality will be excluded.

Furthermore, the geographical dispersion will be of great relevance in the study, as the studied teams work between Sweden and the U.S. and therefore over several time zones. The

technology used for enabling virtual teamwork will in this study be termed ICT, Information and Communication Technology. Examples of such tools are email, video-conferencing tools, file-sharing and chat-based tools.

Previous research does not seem to have a coherent picture of whether virtuality is positive for team effectiveness or not (Gilson et al., 2015). However, Hafermalz and Riemer (2016) emphasize that the virtual aspect can have both positive and negative effects on the work, with one large concern being the fear of isolation. With individual well-being in mind, Bartel,

2

Wrzesniewski and Wiesenfeld (2012) raise awareness of the challenge for employees to develop a strong sense of organizational membership when working virtually. It is common that remote workers express concerns about missing out on social interactions, both on work and non-work-related topics, that occur more naturally in the office than when working remotely (Cascio, 1999, 2000; McCloskey & Igbaria, 2003). Research has shown that virtual teams face more significant communications challenges than face-to-face teams (Hertel et al., 2005). It is also shown that the communication within virtual teams are more impersonal than for colocated teams (Lepsinger & DeRosa, 2015; Schlenkrich & Upfold, 2009).

According to Zeuge et al. (2020) virtual teams have already been widely considered in research. However, due to the rapid change towards a more virtual work climate for a large part of the world’s population due to the coronavirus outbreak, further research is needed since the future will continue to be shaped by virtual teams. Furthermore, Zeuge et al. (2020) believe that a comprehensive, up to date overview of the current situation is missing, as most of the research material is written in a pre-corona environment. Additionally, a comprehensive, recent study on remote work (Buffer, 2020) shows that collaboration, communication and belongingness are the most concerning factors for remote workers globally. These findings have founded the interest of focusing the thesis around the concerns about communication, collaboration and

belongingness in virtual teams. As Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) have been proved to play an important role in a virtual landscape, a desire to gain further

understanding of how these can affect the factors above has also arisen.

Marlow et al. (2017) find that findings in prior research regarding communication in virtual teams are widely mixed. Therefore, they have identified the most relevant features of

communication to the study in future research on virtual teamwork. Marlow et al. (2017) argue that communication frequency, communication quality and communication content are the most vital factors for functioning communication in virtual teams, which therefore will be taken into consideration in this study.

Depth of relationships, trust and shared understanding are suggested to be crucial factors for collaboration within virtual teams (Peter & Manz, 2007). However, these factors have also been proven to be harder to achieve in virtual teams (Zimmerman, 2011). The virtuality and

geographical dispersion entail a higher risk of differing beliefs, contradictory values and divergent interpretations (Florea & Stoica, 2019). Therefore it is of interest to examine whether there are opportunities to decrease these constraints by particular ICT usage. According to International Labor Organization (2020) teams in which the majority or all of the members are

3

working remotely rely heavily on regular electronic communication to foster collaboration, trust, and transparency.

A literature review made by Gilson et al. (2015) shows that there has been limited research on the topic of well-being and whether well-being is positively or negatively affected by virtual teamwork. The authors stress that there are split thoughts on the effects as some virtual team members may feel a sense of isolation and loneliness, whereas others might relish the higher levels of autonomy and independence. Patterns of results for this have been found in research on adjacent topics (e.g. Bélanger et al., 2013) but, to date of their review in 2015, it had not been extensively integrated into work on virtual teams. It is therefore evident that there is a research gap within the field of virtual teamwork regarding belongingness as this can be linked to well-being, making it essential to further study the phenomenon. Furthermore, the fact that most workers today, due to the pandemic, do not even have a choice whether they would like to work in a virtual team or not, the fact of forceness into virtual teams is also an unexplored area within the field.

Reviews show that empirical studies on technology’s role in virtual teams have concentrated on technology’s effect on team performance (Schweitzer & Duxbury, 2010; Van der Kleij et al., 2009; Aritz et al., 2018). Nevertheless, research has not yet shed much light on how technology can enable and constrain communication, collaboration and belongingness in virtual teams. Furthermore, most previous research within the field have limited their studies to just a few media channels, and have not made an extensive review of a wider range of media used to communicate in virtual teams (Aritz et al., 2018). Therefore, a specific study on how different ICTs can help overcome the concerns of communication, collaboration and belongingness, that has arisen in comprehensive studies of remote workers (Buffer, 2020), will be of relevance to fill a gap within a research field that is now more relevant than ever.

1.1

Purpose

The intent is to gain a deeper understanding and provide knowledge on enablers and constraints for communication, collaboration and belongingness in virtual teams. More specifically, ICTs will be studied to understand what impact their elements have on these factors and how the usage of technology can contribute to a well-functioning virtual work model.

4

1.1.1

Research Questions

To reach the purpose, the study will aim to answer the following research questions:

RQ 1: What are the enablers and constraints for communication, collaboration and

belongingness in virtual teams?

RQ 2: How do the characteristics of ICTs impact communication, collaboration and

belongingness in virtual teams?

1.2

Target group

The study is aimed atresearchers within the field of virtual teamwork who want to identify enablers and constraints for virtual teamwork and who have an interest of understanding how characteristics of technology tools affect virtual teams. Furthermore, the study is aimed for organizations working with virtual teams who want to gain knowledge of successful design methods for virtual teams. It can also be of interest for managers of teams which have been forced to transition into a virtual work model due to the current pandemic, as well as for decision makers who want guidance regarding user preferences of, and attitudes towards, different ICTs in a work or study climate in an implementation process regarding virtual work.

5

2

Research Overview & Theoretical

Framework

The research overview and theoretical framework is the research foundation which this study is based on. A definition of virtual teams and usage of ICTs, which is an essential part of virtual teamwork (Laitinen & Valo, 2017), initiates the chapter, followed by a presentation of the Media Richness Theory which will work as a foundation for analyzing the ICTs in the study. Furthermore, an overview of crucial factors of virtual teamwork identified in previous research regards to communication, collaboration and belongingness and their challenges is presented. The structure of this chapter is chosen as knowledge about theory on ICT usage and media richness is needed to gain a better understanding of the previous research related to communication, collaboration and belongingness in virtual teams.

2.1

Virtual teams

A virtual team is a group of individuals interdependent in their tasks with a shared responsibility for outcomes who are dispersed over time and/or location and use a range of communication technology to accomplish their tasks (Gibson & Cohen, 2003). Regarding upsides of virtual teamwork there are several aspects both for the employer and employee. From the perspective of organizations, some aspects that have been shown as advantages of virtual teams include higher profits, improved access to global markets, environmental benefits (Cascio, 2000), higher productivity by using different time zones of members who are geographically dispersed (Dulebohn & Hoch, 2017), greater flexibility and responsiveness (Hunsaker & Hunsaker, 2008, Piccoli et al., 2004, Powell et al., 2004) as they often are based on flat organizational structures without hierarchies and central authority (Jarvempaa & Tanriverdi, 2003), opportunities to reduce travel, relocation (Dulebohn & Hoch, 2017), operating and capital costs (Geister et al., 2006). From the perspective of individuals working in virtual teams, they may enjoy the flexibility of working from a location of their preference, which can implicate a flexibility that may facilitate the balance of employees' work and life and potentially increase their satisfaction with the job (Samul & Petre, 2019). Overall, virtual teams have been shown to more easily and innovatively respond to the changing requirements of the environment based on the latest knowledge, flexible working arrangements and application of information and communication technologies (ICTs), making organizations agile and competitive (Samul & Petre, 2019).

Regarding documented downsides, virtual teams tend to meet more communication-related obstacles than colocated teams (Florea & Stoica, 2019), and interpersonal relationships are

6

proven to be harder to achieve (Zimmermann, 2011). Studies have also shown that virtual teams can face difficulties in regard to the technology-mediated collaboration in form of time lags and a greater occurrence of misunderstandings (Gilson et al., 2015). According to Florea and Stoica (2019), the lack of face-to-face interaction may be associated with negative affective

commitment. A recent literature review conducted by Morrison-Smith and Ruiz (2020) identified the distance factor to be the most associated with challenges in virtual teams, where reduced motivation and awareness, as well as establishing trust were main challenges virtual teams face due to the fact that they lack the common denominator of location.

When a virtual team is transnational, and thereby distributed over several parts of the world, a distinct difference from colocated teams can be the time difference. The time aspect has showed to affect virtual teamwork both positively and negatively. It may enable a greater extent of effectiveness and productivity due to the fact that the team may operate over several time zones (Sarker & Sahay, 2002), but the time difference may also implicate abnormal or uncomfortable working hours that can cause difficulties for team members to fit their work to their private life (Felstead & Henseke, 2017). The abnormal working hours may also entail a more flexible work style, where individuals can plan their time after more personal preferences than in a traditional work environment (Felstead & Henseke, 2017), which therefore can be seen as a positive aspect, but also as a negative aspect for someone in need of a clear and set structure. Sarker and Sahay (2002) have identified several issues regarding time dispersion that have a negative effect on virtual teams. For example, working on different time zones mean that teammates might have different psychological and social activity patterns, such as that a European team member might reach the end of the workday when an American member of the team wakes up.

Therefore, Sarker and Sahay (2002) mean that virtual teams need to find ways to use time lags in a positive manner, rather than seeing it as an obstacle, as members of these teams most often cannot work in parallel to each other.

2.1.1

The usage of ICT in virtual teams

Technologies that are used to enable virtual teamwork can be termed Information and

Collaboration Technologies (ICTs). Examples of such technologies are tools like Zoom, Slack, Microsoft Teams, Outlook and Google Suite. Even though ICTs make virtual teamwork possible, they are seen as widely inadequate for repairing the problem of distance in virtual teams, not the least with regards to the social aspect (Hafermalz & Reimer, 2016). However, there is also research arguing that ICT-based communication does not have to cause a limitation in the actual interaction, but rather just need some extra time to foster social relationships

7

between team members, as the pace of communication tends to be slower than face-to-face interaction (Henttonen & Blomqvist, 2005). Furthermore, studies have also shown that some virtual teams have reported a deeper intimacy and cohesion than some face-to-face teams (Henttonen & Blomqvist, 2005), which indicates that the outcome depends on additional factors, and that virtual teams actually have a possibility to obtain a social value to a great extent.

2.2

Media Richness Theory

The Media Richness Theory (MRT), also known as Information Richness Theory, was originally presented by Daft and Lengel (1984; 1986). It aims to explain how different media channels offer certain levels of media richness depending on its characteristics, and thus indicate that organizational success is based on the organization's ability to process information of appropriate richness to reduce uncertainty and clarify ambiguity (Daft & Lengel, 1984; 1986). Despite its age, MRT is still seen as a landmark foundation of studies on continuously evolving communication technology and media use behavior, and is commonly used within research on virtual teamwork (Ishii et al., 2019). According to MRT, the richness of media is evaluated based on the following four criteria: (1) immediacy of feedback, (2) number of social

and non-verbal cues, (3) language variety, and (4) personal orientation (Daft & Lengel, 1984;

1986; Daft et al., 1987).

Immediacy of feedback is measured by how quickly someone responds to your message. For example with an email, you will not be sure if it has been received until you get a reply, which can take more or less time. In a call or face-to-face meeting, you will get immediate feedback as you speak. Number of social and non-verbal cues aims to measure the variety of ways in which message through a medium can be communicated, such as visually or verbally. Furthermore, language variety refers to the range of ways a message can be mediated. For example, numbers can indicate precise measures, while oral communication simplifies the process of decoding for more complex information. Personal orientation refers to the fact that media in various degrees enable personality in forms of feelings and emotions. For example is face-to-face interaction most commonly seen as more personal than communication over email. (Daft et al., 1987)

Channels that are high in richness hold a higher degree of these four criteria than media of lower richness, and media of varied richness might be suitable in different contexts (Draft & Lengel, 1984; 1986). Daft and Lengel (1986) recommend rich media to be used for more equivocal messages, such as in situations when things need to be discussed between team members where

8

a shared understanding and “rapid information cycles” have to be achieved, whereas lean, written media is preferred for clear, easily interpreted messages, such as information sharing, or something simple as a scheduled meeting time, where the risk of misunderstanding is small. Lean media generally contains less social characteristics, and is therefore suitable for sharing a wider range of information, compared to richer media that tends to include a higher degree of social characteristics, which means it is more suitable for deeper, more interpersonal

information exchange (Miranda & Saunders, 2003). MRT suggests that individuals should match media to the level of equivocality of a task to optimize effective communication in the specific context (Draft & Lengel, 1984; 1986).

Figure 1 below, based on Daft and Lengel (1984), show how different media can be mapped out on a scale of media richness. Face-to-face interaction is evaluated to be the richest medium because of its high score in all four criteria for media richness (Fleischmann, Aritz & Cardon, 2019). Face-to-face interaction enables instant feedback, personal communication and the largest number of social and non-verbal cues as well as variety of language in form of signals through eye contact, body movement and facial expressions additionally to the verbal

communication (Daft & Lengel, 1984).

Figure 1. Communication Media and Information Richness (based on Daft &

9

2.2.1

Media richness in virtual teams

As a theory presented in the 1980s, MRT has been widely discussed for several decades. However, more recent studies have investigated how the theory can be revisited and developed to be better adapted to the modern media climate with rapid technological development and the many new ICTs in today’s world. In the original theory, computer-mediated work was seen as a lean medium (Daft & Lengel, 1984; 1986), but due to the development of such communication tools, this type of medium could nowadays be seen as more or less rich depending on its characteristics and functions (Carlson & Zmud, 1999; Dennis, Fuller & Valacich, 2008; Ishi et al., 2019). Additionally, as MRT originally determined particular media in an objective manner, and due to irregular empirical findings when using the original theory, scholars started to add subjective views of the media which have shown that personal experience, attitudes and knowledge about a medium should, additionally to the objective characteristics with regards to media richness, be considered when evaluating the usefulness and effects of different ICTs in virtual teamwork (Ishii et al., 2019). Later research on MRT in virtual teams has thus shown that there is also a distinct correlation between users’ previous experience with a medium and how favorable the channel will be perceived (Fleischmann et al., 2019).

Rich media is, according to Daft and Lengel (1984), recommended to be used more extensively in organic organizations where the environment is changing and complex, as richer media tends to enable a better collaboration in this type of environment due to a higher level of immediacy of feedback, higher degree of cues, personalization, and language variety. In general, media low in richness is used more extensively in mechanistic organizations within stable environments, as tasks in this type of environment tend to be more structured and wider well-known, which most often means that uncertainty and ambiguity is less occurring (Daft & Lengel, 1984). As virtual teams often operate in an agile, more complex and changing manner (Samul & Petre, 2019), it can thus be considered that these teams would benefit from using richer forms of media in their work.

A recent study on media use and media richness in modern, virtual teams showed that teams using richer communication channels early in their team process were better coordinated and reached better results than teams using leaner communication channels (Aritz et al., 2018). Additionally, the team members of the studied virtual teams evaluated richer channels, such as interactive tools like Google Docs, to be more effective, and lean channels such as traditional email as less effective (Aritz et al., 2018). Industry reports have for years indicated that traditional tools like email are much less efficient for virtual teamwork than newer, interactive and collaborative tools (Aritz et al., 2018), which due to their ability to score higher on the four

10

criteria for media richness (Daft & Lengel, 1984; 1986) can be categorized as richer channels even though they are not always similar to face-to-face interaction. The importance of using richer media early in a team process was also originally stressed by Daft and Lengel (1984) as they meant that equivocality is caused by divergent frames of reference, which can be resolved by discussions through rich media. Furthermore, they believed that less rich media, such as more impersonal written communication, documents and reports, could be used for coordination in a team once a common understanding of tasks and the organizational work had been

established (Daft & Lengel, 1984).

Regarding ICTs that are being used to enable virtual teamwork, video conferencing, such as Zoom or Skype, is a medium high of richness as it is as close to face-to-face interactions as you can get in a virtual climate (Fleischmann et al., 2019). Since video conferencing enables the possibility to see and hear each other in real time, it scores high in all four criteria of MRT (Daft & Lengel, 1984; 1986). However, later research suggests that media, and specifically modern technologies, should not be distinguished along a straight line between rich and lean, but rather from a more nuanced perspective, as new media tend to combine the traditional criteria for media richness (immediacy, cues, language variety and personal orientation) in unexpected ways (El-Shinnawy & Markus, 1997; Fleischmann et al., 2019). Certain media may be positioned on the leaner side of the scale of media richness when focusing on one criteria, but richer when focusing on another (Fleischmann et al., 2019). For example, an online chat tool like Slack enables quick feedback, but tend to be low on cues and language variety, which means that the criteria of MRT do not align with each other for this particular ICT.

2.3

Crucial factors of virtual teams

Working in teams normally means social interaction to a great extent, and when discussing virtual teams in particular, this type of interaction is often challenged in one way or another due to the lack of face-to-face interaction. As suggested by the previously explained Media Richness Theory, face-to-face interaction is the richest kind of medium with the most social cues that enables more personal communication (Daft & Lengel, 1984; 1986). In its absence, virtual teams have to find alternative ways to include a high degree of social interaction through technology tools, as this is proven to have a great impact on virtual teamwork (Florea & Stoica, 2019).

According to a recent literature review made by Dulebohn and Hoch (2017), previous scholars cannot seem to agree on a mutual conclusion regarding effects of virtuality on teamwork.

11

However, comprehensive factors that seem to be present in the majority of all research on virtual team in one way or another are communication, collaboration and belongingness, which all are indicated to have an impact on team outcome – task-related as well as regarding social relationships. Therefore, communication, collaboration and belongingness in virtual teams are presented below.

2.3.1

Communication in virtual teams

Marlow et al. (2017) claim that findings in prior research regarding communication in virtual teams are widely mixed. They argue that this is due to lack of clarity on what should be included when studying communication in a virtual context, significantly due to technological advancement, meaning team communication has been greatly developed. To address this gap and set an agenda for future research, Marlow et al. (2017) have identified the most influential communication features in virtual teams. Their findings suggest that three main factors of communication play a vital role in the functioning of virtual teams: communication frequency,

communication quality and communication content.

Marlow et al. (2017) suggest that a higher communication frequency is more important in a new team to create a higher degree of collective understanding and cognitive behavior within the team. However, too high frequency can be a hinder for team processes as it can cause information overload. Furthermore, Marlow et al. (2017) mean that the quality is the most important aspect of communication in virtual teams and is a main enabler for shared

understanding, both regarding shared beliefs within the team and understanding regarding roles and responsibilities. Communication quality refers to the degree to which the communication among team members is accurate and understood, instead of the actual amount or frequency. Marlow et al. discuss communication timeliness and closed-loop communication as part of quality. They mean that timeliness can be an issue in virtual teams due to time dispersion causing delays and constraining real-time communication. Closed-loop communication means that the sender of a message follow-up with the receiver to make sure no misunderstandings occurred in the communication process, which is an issue more occurring in virtual teams than in colocated teams. Marlow et al. argue that communication content can be divided into two types; task-oriented interaction where the communication is focused on task completion, and relational interaction which is communication of interpersonal nature. Both types are argued as being important for virtual team functioning, but interpersonal communication has been evident to foster cohesion and trust (Jarvenpaa & Leidner, 1998). Media richness theory suggests that media of lower richness, that has no social and non-verbal cues, will constrain social

12

relationships (Daft & Lengel, 1986. However, Marlow et al. (2017) argue that it is evident that virtual teams are able to create social, relational bonds through ICT (without social and non-verbal cues) and thereby develop affective aspects such as trust within the team.

2.3.2

Collaboration in virtual teams

Similarly to Marlow et al. (2017), Kauffman and Carmi (2017) divide communication in task based and relationship based communication. Furthermore, Kauffman and Carmi suggest that a higher and better level of collaboration within a virtual team can be obtained by incorporating a high level of both task and relationship based communication in the virtual work model, as these can build cognitive respectively affective trust, which is seen as another important factor for a functioning virtual collaboration. Furthermore, Peter and Manz (2007) suggests that depth of relationships, trust and shared understanding are crucial factors for collaboration within virtual teams. Therefore, they mean that virtual teams can create a context for the team members by focusing on these factors, which thus can lead to better team performance and collaboration.

Clearly defined roles have by several scholars been stressed as an important factor for

functioning virtual teams as this has shown to have a large effect on other aspects (Zimmerman, 2011). For example poorly defined roles can cause stress and confusion which can affect both individual well-being and team effectiveness (Zimmerman, 2011). It is suggested that greater task complexity in virtual teams need greater task interdependence, which in turn is dependent on clearly defined roles (Bell & Kozlowski, 2002).

Trust, which can be explained as a shared psychological view on intentions and behaviors between members of a team, is crucial for a functioning virtual team, but is often challenged due to the virtuality (Gibson & Cohen, 2003; Morrison-Smith & Ruiz, 2020). Both the

geographical dispersion and the use of ICT in virtual teams have been evident to make it harder for team members to build common ground and to gain an understanding of each other’s behavior, as the time, space and lack of social cues makes identities of individuals more ambiguous, which in turn can cause a lower level of trust in a team (Henttonen & Blomqvist, 2005; Morrison-Smith & Ruiz, 2020). Furthermore, the virtuality and geographical dispersion imply that differing beliefs, contradictory values and divergent interpretations may have a higher impact on the team results than in colocated teams due to fewer natural opportunities to address these differences and that way find common ground (Florea & Stoica, 2019). However, it is suggested that team identity can help bridge these concerns and strengthen trust and shared understanding (Henttonen & Blomqvist, 2005).

13

2.3.3

Belongingness in virtual teams

As in all teams, virtual teams can have a stronger or weaker team identity, and it has been proved that a higher degree of team identity in virtual teams can reduce some of the negative aspects of geographic dispersion (Zimmerman, 2011). However, a high degree of team identity seem to be harder to achieve in virtual teams than in colocated teams due to the virtuality and reliance on ICT, which means a lack of non-verbal cues such as facial expressions and body language as well as less natural personal, informal bonding (Zimmerman, 2011). A shared team identity may also be more challenging to obtain due to the lack of a shared context between the team members (Florea & Stoica, 2019).

It is argued that virtual teams tend to be more task-oriented than traditional teams and therefore, a main concern when analyzing virtual teams is the lack of social interaction and belongingness (Hafermalz & Riemer, 2016). By studying how remote working tele-health nurses overcome the issue of social isolation due to team dispersion, Hafermalz and Riemer (2016) found that individuals within virtual teams can create and maintain a belongingness through technology. Their study indicates that the creation of virtual “water cooler chats” build belonging within the team and can contribute to a positive team performance. Furthermore, other research have shown that positive, interpersonal affect, such as liking and affection, towards other members of the team can foster trust as well as motivation to contribute towards mutual goals due to a higher identification with the team (Zimmerman, 2011).

However, there are research with contradicting findings suggesting that the interpersonal bond between team members that can be enabled through for example virtual water cooler chats, does not have to be the most important for creating belongingness. Rogers and Lea (2005) argue that a sense of belonging as well as a social presence within a virtual team can be achieved by creating a shared social identity as a group, rather than creating interpersonal bonds between the individuals. They also mean that belongingness can be created without simulating face-to-face interaction in the virtual setting, e.g. through video functions. By conducting two case studies, both consisting of ten groups of distributed, collaborating students, Roger and Lea (2005) found that social and physical presence could be conceptually separated as a shared social identity and feeling of belonging to the team could be achieved with the use of technology tools of relatively low richness, such as text-based platforms. Thus, they suggest that it is social presence that is of most importance for the motivation for group based behavior, rather than the feeling of physical presence.

14

3

Method

In the following chapter, the methodology used for conducting the study is presented and backed by method theory. Argumentation for selected methodology choices are presented throughout the chapter, but a specific discussion of how quality has been assured in the study is presented by the end of the chapter.

3.1

Research approach

Due to the nature of the purpose and research question in this thesis, a qualitative research approach has been used. This kind of approach is suitable for exploring and understanding how individuals and groups perceive and handle a social or human problem (Creswell & Poth, 2017).

3.1.1

Study design

The study is formed out of a constructivist worldview perspective, where the purpose is to seek understanding of how individuals experience the world in which they live and work (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Rather than starting off from a theory, an approach of inductive character is usually taken in this type of research to try to find a pattern of meaning in the empirical material to develop theories of how things are and why (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). However, this study has more of an abductive approach, which means that the researcher has gone back and forth between theory and empirical findings throughout the research process. This alternating process between theory and data collection is used in abduction to examine how the empirical data support existing theories as well as whether the data may result in new perceptions and findings that call for modifications in existing understandings (Thornberg, 2012). The abductive approach was thus considered suitable for this study, as the concept of virtual teamwork has been set in a new light in today’s society due to the coronavirus pandemic, which therefore could mean that pre-existing knowledge could fail to explain the empirical findings.

Furthermore, a phenomenological research design has been applied, which means individual experiences of a specific phenomenon is studied (Creswell & Creswell, 2018) – in this case the phenomenon of virtual teamwork. The research design is applied on a case, which means the study could also be seen as a case study. However, it is argued that a comprehensive case study needs a research design in form of a mixed method (Yin, 2018), but as a case in this study is more used as a part of the method to explore the phenomenon of virtual teamwork, the author would argue that this is not the main study design. To enable the phenomenological study design, interviews have been conducted using an interview guide with open-ended questions,

15

which according to Creswell and Creswell (2018) is a recommended way of collecting rich data when approaching a phenomenon, as well as a case, to analyze in this type of study.

3.2

Research setting

The object studied in this phenomenological case study is an American business organization promoting Swedish-American trade through events, networking and business matchmaking. The organization consists of several smaller, regional organizations located all over the U.S., with separate teams that come together in an umbrella organization, striving for streamlined operations over the regional borders. The organization is working both towards the Swedish and the American market, but most activities are normally conducted towards the American time zones.

The selected object is chosen due to its Swedish-American characteristics, where the

coronavirus pandemic has had a great impact on the teamwork model all over the organization, as most of the teams now work over several time zones – most commonly a Swedish and an American one, which is a main difference from before, as all team members in each team normally were located in the same office, in the U.S.. Most teams within the organization consists of 3-5 persons; an Executive Director and one to four additional team members. The team members beyond the executive director are replaced every 6-12 months, as these most commonly are interns moving from Sweden to the U.S. for a limited internship period as part of their studies. Because of the time cycles, which means that all interns have been replaced since the beginning of the year, and due to visa and travel bans into the U.S., most interns are currently working from Sweden, as they have not been able to travel to the U.S. for their internship period, which means all teams have been forced to transition into a virtual work model.

All the three studied teams consisted of one manager based in the U.S. and one or more interns located in Sweden. Additionally, two of the teams did also have interns located in the U.S., but the interns used as respondents in this study were all located in Sweden. None of the teams have had any face-to-face interaction with each other prior to the start of the virtual work model, which means all social interaction and eventual get-to-know-each-other activities have had to be done virtually.

The size of the team varied from 2-4 members: Team A had two members, whereof one intern in Sweden, Team B three members, whereof one intern in Sweden and one in the US, and Team C four members, whereof two interns located in Sweden and one in the US. The team with only

16

two members had help from the board of directors which was present in the daily operations to a greater extent than in the other teams. A table of the teams and respondents used in the study is presented below in section 3.3.1 – Selection/Sampling process.

Some of the respondents had prior experience from working remotely, but not to any greater extent than a few months before joining the current virtual team.

3.3

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews have beenused as a qualitative data collection method to find answers to the research question. This type of interview is characterized by the fact that it follows an interview guide with rather open questions and themes that lead the discussing forward (Alvehus, 2013). However, the semi-structured design still leaves room for personal influences of the respondents, which means each interview can look quite different (Alvehus, 2013). According to Creswell and Poth (2017), qualitative research is used when we want to empower individuals to share their stories and this type of interviews will make it possible to do so. Creswell and Creswell (2018) as well as Gray (2014) refers to this type of data collection as most suitable when conducting a study with a phenomenological research design as it gives an opportunity to find out about individuals’ personal views on a phenomenon. This methodology has been beneficial in this study due to the fact that the purpose is to investigate individuals’ feelings as well as human interaction within teams, which means that it was of importance to ask about personal experiences and thoughts during the interviews.

The questions were focused on attitudes and feelings about the virtual teamwork with a focus on communication, collaboration and belongingness and how the respondents thought this was working out in their teams. Furthermore, the questions aimed to explore the respondents’ attitudes towards different ICTs and how they believe the tools supported or counteracted the concerns about collaboration, communication and belongingness within the virtual team.

3.3.1

Selection / Sampling process

The selection of interview respondents was done from a strategic selection, which means that the respondents are chosen based on specific experiences or positions in relation to the

questions that will be asked (Alvehus, 2013). The strategic selection was based on the fact that it was seen as an advantage of interviewing several members on the same team. This way the possibility of individual differences on how the members of the same team experienced the

17

ICTs’ effect on their virtual teamwork could be discussed. Respondents were also selected out of several teams to enable a comparison of how the work models could differentiate for teams within the same organization. It was believed that it could be of interest to interview at least two people who hold different roles within each team, such as a manager and an intern, to

investigate whether differences in attitudes and thoughts about the virtual work model may have had a connection to the position held. By investigating this, it also enabled the possibility to compare the findings from the different teams to look for possible patterns.

Alvehus (2013) explains how a sample can be homogeneous or heterogeneous, where

homogeneous means that respondent are more alike, and heterogeneous means that respondents are more diverse. It can be argued that the selection in this study can be seen as both

homogenous and heterogenous, as respondents homogenously work in similarly functioning teams, but both managers and interns were selected to make it more diversified in a

heterogeneous manner.

A recommended sample size for a qualitative study varies widely, and according to method theory it is hard to recommend a specific number as qualitative research aims to elucidate something particular and specific, rather than generalize information which more is the case in quantitative research where a larger sample therefore can be of greater importance (Alvehus, 2013; Creswell & Poth, 2017). Thus, the importance of the sample size it that it is big enough to achieve saturation of the material (Alvehus, 2013). Creswell and Poth (2017) means that an optimal sample size also depends on the chosen research approach and that a sample size of 3 to 10 participants could be a considered a reasonable recommendation for phenomenology.

Furthermore, Gray (2014) recommends a sample size of 6-8 participants to secure validity of the material. To ensure saturation of the data in the study, i.e. that no new information would emerge during a further data collection through more interviews, the aim was therefore to conduct at least six interviews, where at least two people within three different teams were interviewed. Two backup interviews were also planned in case of low quality or irrelevant data collection from any of the initially planned interviews. When saturation of the data was believed to have been met, an extra interview was conducted to further secure the saturation of the data collection.

Below is a table of the selected respondents and their anonymization for the presentation of the result and data analysis.

18

Table 1. Respondents mapped out in relation to their teams Team A A1 (U.S.) A2 (Sweden)

Team B B1 (U.S.) B2 (Sweden)

Team C C1 (U.S.) C2 (Sweden)

3.3.2

Interviewing process

An interview guide was constructed with questions focusing on finding answers to the research question. After the construction of an interview guide, the guide was tested in a test interview. This made it possible to get feedback from a person not involved in the study, who could give direct feedback on the questions and process. The test person was working in a virtual team herself and could therefore give valuable and relevant inputs on the material. By conducting a test interview, the questions could be modified to fit the purpose of the study better, and thereby be better constructed to help answer the research question.

Potential interview respondents were approached through email. The email briefly described the purpose and aim of the study and suggested several dates and times for conducting the

interview, if the respondent would accept the invitation. Seven interviews were scheduled between November 6 and November 9, 2020, and an additional interview was later on scheduled for November 16 to assure saturation of the collected material. All interviews were conducted through Zoom Video, which meant they could be automatically recorded. The interview started with a further explanation of the purpose and aim of the study, which was followed by an explanation of the premises of the study, as well as the respondents’ rights to decline to answer a question or to discontinue the interview at any time. Further on the respondents consent to record the interview was requested before starting. The importance of asking for consent and other ethical questions will be discussed in section 3.6 – Ethical considerations. The interview followed the interview guide, but if a question became of irrelevance it was deleted from the guide, where an example is if it had been answered in relation to a previous question. Furthermore, due to a semi-structured design, relevant follow up questions where constructed and asked during the interview to dig deeper into concepts that arose in the answers. Some additional questions were added after a couple of conducted interviews, as new angels came to mind during previous interviews that could give a further understanding of the phenomenon of virtual teamwork in the rest of the interviews.

19

3.4

Data analysis

The interviews were recorded and thereafter transcribed. The software ATLAS.ti was used for transcription and coding of the collected qualitative data, and later on sorted into themes. ATLAS.ti is according to Creswell and Poth (2017) a relevant tool to use for this purpose, and the data analysis tool has also been used by Koivula, Villi and Sivunen (2020) who has conducted a study on a similar topic with some similarity regarding methodology, which was found helpful when planning and organizing the sorting of the collected data in this study.

3.4.1

Thematic analysis

After transcription, the collected data from the interviews was analyzed through a thematic analysis. Firstly, all material from the interviews was read through and coded, where quotes that were of interest in different ways were highlighted. These were of interest due to the fact that they were in line with something stated in previous research, because it contradicted previous research or believes, and therefore were somehow surprising, or opened up for new questions. Further, the codes were reviewed and sorted into a first set of themes which were centered around the three factors communication, collaboration and belongingness. This was a natural choice due to the fact that these were the factors stated in the research questions, and therefore the most relevant main thematization of the data. This was identified in the first cycle of

analysis. Furthermore, a second cycle of analysis was conducted where these three main themes was divided into sub-categories where enablers and constraints within the three factors of remote teamwork were extracted from the interview data. Furthermore, a theme regarding ICT was applied to the data, which most often was applied to quotes that also had a relation to one of the three other main themes about communication, collaboration and belongingness. A sub-category of the ICT theme was ICT preferences, which helped identify what ICTs and elements of these that were preferred in the virtual teamwork amongst the respondents. Quotes that didn’t fit in to the main thematization, but were considered interesting for the study, was added to two additional codes regarding general upsides and downsides of virtual work, which in a later stage could be added to the result if proved to be of relevance in relation to the rest of the result and study as a whole. After the thematization in ATLAS.ti, the quotations within each theme were read through again to identify patterns or contradictions in the material.

20

3.5

Ethical considerations

Regards to ethical considerations, measures have been taken in all steps of the study, as this is of great importance when conducting a study in a human setting (Wiles, 2013). The ethical considerations taken are mainly based on Wiles’ (2013) suggestions of informed consent,

anonymity and confidentiality and risk and safety as key principles of qualitative research

ethics. The aspects were greatly taken into account for the data collection, where parts could be psychological sensitive for respondents of the interviews and therefore of great importance.

Informed consent involves providing the participants with clear information about the study,

from which information they can decide whether they would like to proceed with their

participation or not (Wiles, 2013). Therefore, the aim of the study was clearly explained to the respondents in the email request for participation, as well as before starting the interview. Before continuing, consent for recording the interviews were also asked for. Furthermore,

anonymity and confidentiality is about keeping identifiable information of participants private

(Wiles, 2013). In the study, anonymity of the participants was assured by coding all names in the results, and thus present the data in an anonymous way. Regarding risk and safety some researchers suggest that there are very few risks in this type of research, compared to for example physical, experimental research (Wiles, 2013). However, Wiles claims that a great risk to consider is one related to participants emotional and psychological well-being. In this study, some parts in the data collection could be considered ‘sensitive’, such as when discussing belongingness and feelings of loneliness. To minimize this type of risk, the participants were informed that they could interrupt at any time and that they were not obliged to answer questions they were not comfortable with.

3.6

Quality of study

Actions to assure quality of the study have been taken during the whole process from idea generation to final product. Obstacles for quality assurance are inevitable in all studies (Gray, 2014), but the course of action to bridge the obstacles for this study is presented below.

Traditional terms within research quality are validity, reliability and generalization (Gibbs, 2007). Validity means that explanations are accurate and correctly captured in relation to what has actually been studied, reliability indicates that results would be consistent when repeating the study under other circumstances and with another researcher and generalization means that findings of the study can be applied in a wider perspective than just in the specific studied context (Gibbs, 2007). However, these terms are originally constructed for quantitative research,

21

which means that it might be misleading to directly apply the original definitions of the terms to assure quality in qualitative research (Gibbs, 2007). For example, reflexivity, i.e. the recognition of background and presumptions of the researcher, is widely discussed in qualitative research (Gibbs, 2007) and means that total objectivity of a researcher is unachievable. Thus, individual perspectives of the researcher can in that sense threaten reliability. As qualitative interviews with a small sized sample were used as a single method for gathering data for the results of this study, it could be argued that the generalization is limited, as the results are highly influenced by individual views. However, the constructivist, phenomenological design of this study means that the purpose is to seek understanding of individuals’ experiences (Creswell & Creswell, 2018) and therefore, generalization is not aimed for in any great extent. Yet, by using a

quantitative sampling process as a second methodology in addition to the qualitative interviews, the results could possibly have been more adaptable for a larger part of a population and thus more generalized.

Tracy (2010) has defined alternative terms to the traditional ones, more specifically suitable to assure quality in qualitative research. Amongst Tracy’s suggestions are the terms worthy topic,

sincerity and credibility, which are discussed in relation to this study below.

Regarding worthy topic, Tracy (2017) states that qualitative research should be relevant, timely, significant, interesting, or evocative to be of good quality. Worthy studies often present

surprising results, which is a reason for why studies on less explored phenomena might be of high interest (Tracy, 2017). The phenomenon of virtual teamwork could definitely be considered a worthy topic, as it is timely and relevant in today’s society, in the light of the pandemic. Furthermore, the review of previous research within the field indicates that the phenomenon is worth to explore further.

By sincerity Tracy (2010) mean that a study is authentic and genuine in the sense that the researcher is being honest and transparent regarding choices, biases, methods and mistakes. Regarding transparency, the author of this study has tried to describe the methodology as detailed as possible for the reader to understand exactly how the results and conclusions have been found, and to explain the choices that have been taken throughout the research process. Worth mentioning is the bias of the author in the sense that she had previous experience within the organization chosen as study object. The organization was partly chosen as study object as the author had prior knowledge of the organization and the way of working. Through a quality perspective, this could be seen as both an advantage and disadvantage. On one hand, this can mean that it is easier to get a deeper understanding of the work model and processes, but on the other hand, this can result in preconceptions and a biased view of the material. Therefore, the

22

author has tried to put personal experiences aside when conducting the interviews and analyzing the data, to not draw any conclusions based on preconceptions. However, the prior knowledge has been an advantage when constructing the interview guide as it was easier to find relevant and meaningful questions.

When discussing credibility, the trustworthiness of the study is centered (Tracy, 2010). Using an abductive approach enhanced the credibility of the study as it meant that the author went back and forth between theories and empirical data to make necessary changes to fit the research question. This way, it was easier to ensure findings were adequate both regarding the purpose as well as in relation to previous research.

23

4

Results

The presentation of the results from the interviews, i.e. the empirical data, follows a structure where results regarding the main themes communication, collaboration and belongingness are first presented, followed by results regarding the theme of ICT, which can be set in relation to the three themes above. Furthermore, geographical dispersion as well as time dispersion were identified as main influencing factors of teamwork in the data from the interviews and are therefore integrated in the results for the three main themes. Lastly, identified possible improvements of the virtual teamwork are presented as well as the respondents’ attitudes towards working virtually if there was a choice.

4.1

Communication

Team meeting frequency varied from one set time for a team meeting a week, to twice a day, meaning the teams had between one and ten set team meetings a week. Additionally to the set meeting times, there were meetings booked on shorter notice throughout the week, depending on the workload and communication need.

Regarding communication in the virtual teams, each respondent thought it worked surprisingly good in their teams, but had not really anything to compare with. However, the new work model meant that the respondents had to be more flexible and adaptable, since the working hours were not as set as before. An advantage identified about the flexibility was that you could be more free to set your own schedule. Several respondents empathized with the fact that you have to be very structured with your own time schedule and be more self-paced than in a normal work setting. A negative aspect of this could arise if you would not set limits, as it would be easy to work around the clock due to the time difference.

Previously, I didn't really structure my day the same. I kind of, waited for new tasks to show up. They usually show up late in the evening. So then I felt I got really stressed, because I didn't feel like I had any kind of separation between personal life and work life.

Respondent C2

Respondent C1 also believed that people on the Swedish time zone were suffering as the normal workday was about to end for them when work started in the US, which she thought could contribute to a non-functioning work model with no borders between work and free-time:

24

I think the people in Sweden suffer because the US day is starting when the Swedish working day is done. I think you have to be very disciplined on the Swedish end to stop checking your emails, around let’s say 6pm CET, and we here in the US will go on for another 6 hours. Therefore it’s very tempting for people in Sweden to follow the emails and conversations to literally midnight Swedish time.

Respondent C1

However, being in the Swedish time zone could also be seen as an advantage as one is always ahead of time. For example, respondent B2 mentioned that he felt like he always had six additional hours for a deadline, which he saw as a positive aspect of the time dispersion.

Furthermore, respondent A1 saw a negative aspect of being on the American time zone as it could make you feel a bit behind on things when having the morning meeting US time in Swedish afternoon. That made it hard for her to prepare properly and decide what to discuss.

Communication in the virtual setting was seen to be less spontaneous. In the office it was seen as easier to “chitchat” more, and now most real-time communication was scheduled in advance, which meant that spontaneous conversations disappeared. Respondent B1 stressed that she missed that type of communication that they would normally have in the office, but that it was more effective to work this way:

I would say it’s more time efficient being like this. I just know that when we go into the office, it can be an hour before we actually get started – you get coffee, and chitchat about things, especially on Mondays, and now that’s like 5 minutes in the beginning of a zoom meeting, so much shorter than in the office. So I think like 8 hours in the office could be less when working remotely.

Respondent B1

An advantage that was stressed by each respondent regarding communication was the fact about availability. In general, it was seen as easier to get on hold of people, and to schedule a short zoom call was seen as easier and more efficient than trying to book an in-person meeting. Additionally, since all meetings could be done in the same spot, there was an opportunity to have time for more meetings.

You could take a zoom call, you could have a (virtual) in person meeting so to speak, even if you’re on the run. I don’t have to change venue to meet with someone. I could almost be on my bike now!

25

Virtuality was also seen as an enabler to open up the possibility to communicate easier with people and organizations in different locations:

As an organization I think all the regional organizations become closer as a whole since we can more easily arrange meetings all together in the umbrella organization. One advantage is that it's easier to talk to more people from everywhere, like for example to network.

Respondent A1

4.2

Collaboration

The collaboration was often discussed in relation to the communication. Each respondent believed that that collaboration takes a bit longer when working in virtual teams. A main reason for this was the time difference, as the real-time collaboration was not as frequent due to different work schedules within the teams. Respondent B1 also mentioned that it was easier to misunderstand each other when collaborating:

I think things take a little more time now when we’re not together cause it was easier when we could look at it together and get it done. […] It’s easier to misunderstand what someone means when you want to change something in a design for example.

Respondent B1 Respondent B1 continues, and realize how the collaboration could get more efficient:

It’s not like we go on zoom just to check a poster, but maybe that’s what we should do now when I think about it, to discuss the proposal, maybe that’s an idea of making it more efficient. The fact about discussing designs etc on zoom instead of sending over in an email just hit me now, I haven’t thought about it, or what the best thing to do is. Like in a meeting just showing and saying “here’s the proposal”.

Respondent B1

However, respondent C1 believed it was an issue to collaborate, even when on Zoom, as there still where obstacles for explaining things to someone on another screen.

Something else that was identified regarding collaboration was the fact that borders between roles seemed to be a bit blurred due to virtuality. Respondent C2 mentioned the fact that it is hard to know what others are doing when not being in the office, and respondent B2 also agreed