Communication for Development One-year master

15 Credits Spring 2020

Supervisor: Tobias Denskus

Representation of the “Other”

Discourse of female circumcision in the Journal for Midwives

Abstract

Author Title

Anna-Kaisa Dele

Representation of the “Other” – Discourse of female circumcision in the Journal for Midwives

Number of Pages Date

51 pages 20 March 2020

Degree Master of Arts

Degree Programme Communication for Development Instructor

Tobias Denskus

This thesis studied the representation of female circumcision by analysing 32 articles published during the 21st century in The Journal for Midwives, the union journal of the Federation of Finnish Midwives. With critical discourse analysis, through post-colonial feminist theory, the thesis researched the ways the journal is contributing to the creation of readers’ bias regarding circumcised women and their sexuality.

The articles focused on multicultural healthcare, prevention of female circumcision and the most serious health detriments the practice might have. Human rights, criminal law, and gender equality were the main reasons behind the aversion of the practise. Women from the practicing communities were represented as victims of patriarchy, clueless of their position and unable to decide for themselves. Sexuality of circumcised women was widely excluded, only described through possible negative health consequences. Anthropological approach to sexuality and the role of migration was excluded and discussions about complex ethical questions, racialization, power relations and bias of healthcare professionals were absent. Female circumcision and the practicing communities were categorised and judged based on Western understanding of sexuality and gender equality.

Based on the analysis, the thesis recommends more diversity to the production of texts and to the perspectives of articles. Minorities should be included more in the production of the representation of their health issues and wider sociocultural explanations behind the practise should be presented. Discussions about health inequalities based on ethnicity and reflections about cultural hegemony of West in relation to sexuality are also recommended subjects to be included in the journal. Most importantly, stereotypical representations of broken womanhood and positioning circumcised women as oppressed victims who need to be rescued by outsiders, should be forgotten. Instead, individual care of women and the importance of personal experiences and meanings of circumcision and sexuality should be highlighted.

Keywords Female circumcision, female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C), postcolonialism, midwifery, critical discourse analysis, representation

Contents

Abbreviations and terminology ... 4

1. Introduction ... 6

2. Background ... 8

2.1. Culture, migration and sexuality ... 8

2.2. Multicultural healthcare and implicit bias ... 10

3. Analytical framework ... 12

3.1. Representations ... 12

3.2. Postcolonial feminist theory and female circumcision ... 14

4. Methodology ... 15

4.1. Critical discourse analysis (CDA) ... 16

4.1.1. Fairclough’s three-dimensional approach ... 16

4.1.2. Researcher’s position ... 17 5. Research data ... 18 6. Analysis ... 20 6.1. Textual analysis... 20 6.2. Processing analysis ... 29 6.3. Social analysis ... 34 7. Conclusions ... 39 References ... 46

4

Abbreviations and terminology

C4D Communication for development

CDA Critical discourse analysis

Deinfibulation Surgical procedure carried out to re‐open the vaginal introitus of women living with infibulation

Dyspareunia Painful sexual intercourse

EU European Union

FGM/C Female genital mutilation/cutting

M4D Media for development

NGO Non-governmental organisation

Re-infibulation Re-suturing, after childbearing or gynaecological procedures, of the incised scar tissue resulting from infibulation

STM Ministry of Health and Welfare

THL Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare

UN United Nations

Vaginoplasty Surgical procedure designed to tighten the vagina

WHO World Health Organisation

Female circumcision, also referred as FGM/C, is a partial or total removal of external female genitalia, or other injury to female genital organs for non-medical reasons. The type of circumcision ranges from pricking the clitoris or clitoral hood, to more extensive procedures in which tissue is removed. Different types have been categorised as:

Type 1. Clitoridectomy (partial or total removal of the clitoral glans (the external and visible part of the clitoris), and/or removal the prepuce/ clitoral hood)

Type 2. Excision (partial or total removal of the clitoral glans and the labia minora, with or without removal of the labia majora)

Type 3. Infibulation (in which the vaginal opening is narrowed through the creation of a covering seal, which is formed by cutting and sewing over the outer labia, with or without removal of the clitoral hood and/or inner labia)

Type 4. All other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, e.g. pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterizing the genital area.

5 Female circumcision can cause pain, severe bleeding and urination problem, and later cysts, infections, as well as complications in childbirth. Also psychological problems are possible. The risks increase with the severity of the procedure. It is estimated that around 90% of female circumcision cases include either Types I, II or IV, and about 10% are Type III, which is considered the most severe form of female circumcision. (WHO, n.d.)

Reasons behind the tradition vary depending on areas and groups that practice female circumcision. Circumcision can be performed at any age from infancy to the postnatal period after first pregnancy. The practice is mainly concentrated in Western, Eastern, and North-Eastern regions of Africa, as well as in some countries in the Middle East and Asia. Rituals for entering adulthood, beliefs regarding purity, control of sexuality, belonging to a community and symbolic meanings of womanhood are some of the many reasons behind the tradition. (WHO, n.d.) There are no simple explanations which factors influence behind the tradition, and generalization of communities practicing female circumcision should be avoided. For example, according to the research of Quichocho (2018, p.86), even among the Nigerian tribe Yoruba, female circumcision is viewed through heterogenous perspectives. Yoruba philosophy describes circumcision as a way to increase sexual pleasure, however beliefs among practitioners vary from promiscuity to the necessity to sacrifice clitoris to save the future children (clitoris is seen as a powerful and aggressive organ and it is believed that the infant will die if the clitoris touches the head of the baby).

About terminology

This thesis uses the term “female circumcision” due to its neutrality, except when referring to campaigns against female genital mutilation, when “FGM” is being used.

The term “woman” is used for people assigned as women, without further knowledge of their gender. Background researches and other source materials as well as all the research data use the term “woman” when discussing about people undergone female circumcision, and therefore the same terminology is kept for this thesis.

6

1. Introduction

Female circumcision, female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C), has been a hot topic in West for nearly 50 years, raising questions about multiculturalism, cultural relativism and human rights. The tradition has been researched in several fields from anthropology to medical sciences and feminist studies. Since the 1970s, the ideas of “global sisterhood” have driven Western feminists to stand against FGM, while awakening postcolonial critique of the anti-FGM discourse. In the 21st century the discussion has broadened to involve questions regarding freedom of choice, social constructions of sexuality as well as comparisons to Western genital cosmetic surgeries.

NGOs, governments, and powerful institutions like EU, have taken the agenda to globally stop this ancient practice, midwives being one of the key groups in the preventative work. Midwives work with the most sensitive aspects of life with people from various backgrounds. From questions of chest/breastfeeding and sexual identity to reproductive challenges and gynaecological diseases, from birth to death. Legislation and care guidelines direct the clinical work, however implicit bias has an impact, if not directly on the treatment outcome, at least on the patient interactions. Social upbringing, anti-FGM campaigns and representations of Global South influence in the minds of midwives working with circumcised women.

There are approximately 10 000 circumcised women and girl living in Finland and currently 650–3080 girls are under a threat to go through circumcision (Koukkula & Klemetti, 2019, p.27). Researches have revealed circumcised women’s negative and disrespectful encounters within Finnish healthcare field (Palojärvi, & Seppälä, 2016, p.15; Mardiya & Zeinab, 2011, p. 43) as well as lack of knowledge about the tradition among Finnish healthcare professionals (Koukkula & Klemetti, 2019, p. 11). The amount of information about the practise has increased over the past decade, but the attitudes of healthcare professionals, as well as various aspects impacting on them, remain unresearched.

This thesis focuses on the discourse around the topic of female circumcision in the membership journal of The Federation of Finnish Midwives, Kätilölehti – Tidskrift för Barnmorskor. The thesis reviews research regarding implicit bias among healthcare professionals and impact of the anti-FGM discourse to the sexual wellbeing of circumcised women. The role of representation in creation and recreation of power relations is also discussed. Through

7 postcolonial feminist lens, the thesis analyses 32 articles published in the 21st century. With critical discourse analysis the purpose is to study how female circumcision and sexuality of circumcised women are represented. The thesis aims to find ways of representation which do not maintain existing inequalities but rather offer diverse understanding of sexuality and health while supporting midwives in their work for social change.

Research questions

Research question:

In which ways the Journal for Midwives is contributing to the creation of readers’ bias regarding circumcised women?

Sub-question:

How is sexuality of circumcised women addressed in the journal?

Relevance to communication for development studies

C4D includes variety of ways to approach and study communication around topics of globalisation, development and social change. This thesis engages with media representation of cultures and people of Global South in the media in Global North. The thesis is also connected to M4D approach, as it analyses the media which is used strategically as a tool for creating change in readers knowledge, attitudes and practices while aiming for social change. M4D can be defined as the strategic use of the media for creating change in people’s knowledge, attitudes and practises with an aim to achieve development goals (Scott, 2014, p.13).

Scott (2014, p.18) refers to Katz and Lazarsfeld (1955) who introduced a “two step flow” model of communication to explain how information is transferred from media to the general public. At first from media to opinion leaders and then from those leaders to masses through interpersonal communication. The main idea is the importance of targeting opinion leaders and combining media communication with interpersonal one. One key theme of M4D approach is to seek planned change targeted at particular audiences (Scott, 2014, p.20).

WHO has stated that strengthening the health sector is the most important way to prevent female circumcision. Midwives have a unique position to influence and change attitudes of their patients and therefore their knowledge about the practice is strengthened through different

8 methods, including professional health journalism. Therefore, articles in the Journal for Midwives are a form of social practice contributing to social change trough M4D approach. Due to their socially consequential role, discourses can help to produce and reproduce unequal power relations through the way they represent things and positions of people. Analysis of these discourses offer a mirror to study subconscious and institutionalised inequalities as well as how those are recreated through language and generate bias among midwives.

2. Background

This chapter focuses on key themes around female circumcision and sexual health in Western countries. It presents research about the influence of culture and migration to sexual identity and how the anti-FGM discourse in diaspora affects to the sexual self-esteem of circumcised women. In addition, the chapter explores implicit bias among healthcare professionals and how dominant anti-FGM discourse as well as prevalent stereotypes can impact on treatment outcomes and patient experiences.

2.1. Culture, migration and sexuality

Defining culture is not simple and usually it is explained as something that distinguishes insiders from outsiders, something that is “shared by people” (Bonder, Martin & Miracle, 2001, p.35). Cultures are everchanging and at times forces either from within or from outside can have a dominant influence upon a particular culture. Globalization, which Eriksen (2015, p.26– 30) views as sociocultural process that contributes to making distance irrelevant, is also influencing cultures. While cultures are transforming and blending, some local identities are strengthened as a reaction to the contest of globalization. Friction and conflict often result from migration, meetings of cultures, actualization of differences and feelings that traditions, cultures or religions are threatened.

Referring to Rubin (1984) Palm, Essén and Johnsdotter (2019, p.2) note that cultural norm systems situated in a certain time and place also influence on people’s opinions of what is considered “good” or “bad” regarding sexuality and bodies. Sexuality is politically organised into systems of power, which encourage some individuals and activities, while suppressing others (Rubin, 1992, p.171). Citing Ross (1997) Leval et al. (2004, p.757) note that sexual satisfaction is also a social construction which is experienced differently in different context.

9 Different cultural norm systems regarding sexuality also impact on the sexual health of those undergone female circumcision. Catania et al (2007, p.1675–1676) found that when circumcised women live in the culture that makes them live circumcision as a positive condition, orgasms are experienced. However, when there is a cultural conflict, the frequency of orgasms is reduced. Most medical studies on sexual function show no statistically significant difference in sexual function between those undergone female circumcision and those who are not (Johnsdotter 2018, p.20). These findings bring up important questions about the role of surrounding culture, attitudes and discourses when it comes to female circumcision and sexual wellbeing.

Anti-FGM discourse and sexual dysfunctioning

Discourses change and challenge individual subjective experiences of self. Identities are built and shaped through discourses and therefore could always be different. (Pynnönen, 2013, p.19; Baaz, 2005, p.173). Bagnol and Mariano (2008, p.49) argue that ethnocentrism underlies the production of discourses and the objectification of the African and Asian female body and stigmatises “other’s” practices. After migration, circumcised women live surrounded by this stigmatising discourse condemning them as “mutilated” and sexually dysfunctioning (Johnsdotter, 2018, p.18).

Western heterosexuality and female pleasure are traditionally very clitoral centric (Leval et al. 2004, p.756 citing Hite, 1977; Johnsdotter, 2002; Kinsey, Pomeroy, & Martin, 1948; Masters & Johnson, 1966.) While some Westerners see external clitoris as an affirmation of their sexual autonomy and gender equality, for some Africans abandonment of the same clitoris symbolizes separation from masculinity and therefore defines the archetype of matriarchal power (Ahmadu, 2007, p.308). Cultural norms influence on individuals’ sexual identity and experiences. According to Johnsdotter (2019, p.22–23) some circumcised women felt like full women in their countries of origin and only after migrating to Global North, they have learned from the anti-FGM discourse that they are “mutilated”, sexually deprived and lost their womanhood. Baršauskaitė (2018, p.14.) researched the relationship between female genital self-image and sexual dissatisfaction and discovered a significant impact of negative genital self-image to sexual dissatisfaction. While genitals are increasingly present in the public domain, genital self-image is more affected by external influences from the media. Villani (2017, p.266) as well

10 states that people give great importance to the discourse and images portrayed in the media about the model of what a desirable body and genitals should resemble. In diaspora, the practice that was performed during childhood, is interpreted by discourses and values condemning it as a form of violence. Therefore, anti-FGM discourse can influence on the feelings of loss of identity, of defective femininity, and of sexual disfigurement, and have negative impact on sexual health and wellbeing (Johnsdotter, 2018, p.21). Increasing demand for clitoral reconstructions in Europe must as well be understood in relation to the anti-FGM discourse (Johnsdotter, 2019, p.1). Study among circumcised Swedish women who went through clitoral reconstruction found that the reasons for the surgery were based on their longing to have a sense of restitution, of “normal” womanhood, and visible signs of the cutting being removed. They also hoped for improved genital self-image. (Jordal, Griffin & Sigurjonsson, 2019, p.713.) Female circumcision in itself may have a negative impact on sexual health; however, it is important to acknowledge that also anti-FGM discourse may cause sexual dysfunctioning (Johnsdotter 2018, p.20). More culturally sensitive policies are needed to reaffirm the value and positive body image in order to show respect for various cultural heritages. Those undergone female circumcision have an equal right to see themselves as normal and healthy instead of being viewed as ““mutilated” objects who are in some pathetic “search for missing

clitorises.”” (Ahmadu 2007, p.308.)

2.2. Multicultural healthcare and implicit bias

FitzGerald and Hurst (2017) define implicit bias as “associations outside conscious awareness

that lead to a negative evaluation of a person on the basis of irrelevant characteristics such as race” (p.2). Stone and Moskowitz (2011, p.768) state that over time stereotypes and prejudices

become invisible to those who rely on them. Automatic categorisation of individuals can unconsciously trigger stereotypes and prejudices associated with the group the individual seems to belong to. This happens even if reactions are explicitly denied and rejected.

Negative implicit attitudes and feelings shape how also healthcare professionals evaluate and interact with minority group patients. FitzGerald and Hurst (2017, p.2,14) found that several studies from different countries, which used different methods and patient characteristics, testified of implicit bias among healthcare professionals and of negative correlation between level of bias and quality of care. Apart from implicit associations and their influence on care decisions, implicit bias results in non-verbal behaviour. Bias may not always straightforwardly

11 mean negative treatment outcomes, however clinical interaction between healthcare professional and patient is essential part of care.

Holm et al. (2017, p.360) argue that healthcare professionals’ unconscious bias is a result of unrecognised privilege and contributes to healthcare disparities. Nursing and medicine are cross-cultural professions and understanding one’s own cultural background in relation to others, is crucial in avoiding disrespect (Leval et al., 2004, p.758). Holm et al. (2017, p.360) suggest that challenging healthcare professionals’ certainty about the universality of their cultural experiences can help them to recognise the validity of different experiences. It is important for healthcare professionals to acknowledge how their handling of cultural differences has an impact on patients and realise that standards, professionalism and guidelines will not immunize them from bias (Holm, Gorosh, Brady, White & Perkins, 2017, p.360).

Female circumcision and Western healthcare

Care guidelines and policy documents guide the actions and obligations of professionals working with circumcised women; however, they are also influenced by culture specific ideas about sexuality and stories of anti-FGM campaigns. Study among Swedish healthcare professionals (Palm, Essén & Johnsdotter, 2019, p.1,9.) found that professionals showed strong commitment to helping circumcised girls and young women; however, their approach was focused on genitalia’s role in sexuality and Western image of what constitutes a functional body and sexuality. Professionals did not explore the girl’s own experiences of the situation, which might lead to professionals unintentionally projecting their own perceptions. Many professionals believed that female circumcision leads to incapableness to enjoy sex. This shows Western tendency to view sexual functionality to be something that can be damaged or taken away by cutting the genitals, thus pointing to genital focused approach to sexuality. (Palm, Essén & Johnsdotter, 2019, p.4.)

Another study researched the attitudes of midwives towards circumcised women (Leval et al. 2004, p.755–577) and states that viewing sexuality from ethnocentric perspective is a way of confirming one’s own sexuality. As Western beliefs about female sexuality are clitoris and genital orientated, midwives also expressed strong emotions over what they saw as destruction of women’s sexuality. Even though they acknowledged their limited knowledge, they still

12 expressed anger at men and saw circumcised women powerless in relation to society and male dominance.

Leye et al. (2006, p.368) highlight that healthcare providers also need to resolve the conflict between attitudes towards female circumcision and genital cosmetic surgeries. At present, tensions are obvious as regards the modification of female genitalia, and current legislation and medical practice show inconsistencies in relation to women of different ethnic backgrounds. Even the pricking of the African clitoral hood is condemned, while reduction of clitoral tissue in Western female genitalia is legal and accepted (Johnsdotter & Essén, 2010, p.34). Westerners are also permitted to go through vaginoplasty while African immigrants are denied re-infibulation after childbearing (Earp, 2016, p.121). Inconsistencies in legislation and inequalities in the quality of care are reflections of existing unequal relations of power. Anti-FGM discourses and representation of Global South contribute to the creation and recreation of bias among healthcare professionals causing health disparities.

3. Analytical framework

Analytical framework of this thesis focuses on the role of representation and discourses in creation and recreation of social inequalities. The chapter also presents postcolonial feminist theory, which is used as a lens for the analysis. Postcolonial feminist perspective was chosen as the thesis studies communication about non-white women of Global South directed to representatives of the majority in Global North.

3.1. Representations

Representation is the production of meanings of the concepts of minds through language. Hall (1997, p.1–5) defines representation as “using language to say something meaningful about, or

to represent, the world meaningfully, to other people.” It links concepts and language and

therefore enables us to refer to either what is real or to what is imaginary. Concepts are organised into relations with one another, and their meanings are dependent on the conceptual system as well as relationships between things. Representation enables to give meaning to the world by constructing a set of correspondences between things, conceptual maps and set of signs, arranged into languages which represent those concepts. “The relation between ‘things’,

13

concepts and signs lies at the heart of the production of meaning in language. The process which links these three elements together is what we call ‘representation’” (p.3).

In the use of language, different choices create different meanings which are organised in certain ways. At the same time, particular representations about topics, actors, relations and identities are produced. Representation always chooses what is described and what is left out. It is a powerful tool in its way to describe events and phenomena and their causal relations as true and to build and share information from particular angles. Representation results as certain meanings which exclude something and include another, directing mental concepts of the readers. (Pynnönen, 2013, p.17–18.) Van Dijk (1993, p.268) states that due to the lack of alternatives, members of the audience tend to adapt dominant models and corresponding attitudes. By its ability to direct mental concepts, representation also offers a possibility for a change and development. Providing alternative meanings and studying how stereotypes and discourses are institutionalized in society, are ways for a social change to occur (Baaz, 2005, p.174).

Discourse as a tool of power

Power involves control, which may concern action as well as cognition. Apart from limiting the freedom of others, power can occur as an influence on their minds by persuasion, dissimulation and manipulation. Managing the minds of others is a function of text and talk. It may not always be directly manipulative, but dominance can be enacted and reproduced in subtle manner that appears natural and acceptable. Detailed, micro-level and expressional forms of discourses are more or less automatized and less consciously controlled. The influence of power in these discourses is less direct and immediate. By making use of strategies that manipulate the mental models of the audience, discourse can be used as a tool to develop preferred social cognitions which are social cognitions that are in the interest of the dominant group. (Van Dijk, 1993, p.254,261,279–280).

Using power through discourse requires access to social resources and therefore those who dominate the public discourse are central actors. Access to discourses enables more power and opportunities to influence in societies and in the minds of the audience. Dominant, “obvious” and unchallenged discourses limit understanding and dictate what is acceptable and legitimate behaviour and action. Simultaneously it excludes alternative knowledge and models of

14 behaviour. (Pynnönen, 2013, p.17.) Discursive reproduction of power results from social cognitions of the powerful (Van Dijk, 1993, p.259).

3.2. Postcolonial feminist theory and female circumcision

Hernández and McDowell (2010, p.30) define colonialism as a promotion of dominant group ideologies, beliefs, and cultural practises in order to maintain domination over cultural, social and economic capital. This leads indigenous and diverse lifeways to be devalued, marginalised and associated with low cultural capital, resulting euro-centred theories, practices and social hierarchies, that are based on privilege and oppression, becoming preferred (Alva 1995 cited by Hernández & McDowell, 2010, p.30). Citing Quayson (2000), O’Mahony and Donnelly (2010, p.443) highlight that the term “postcolonial” does not mean that the colonial stage has passed, but it should be viewed as ongoing process of the struggle against colonialism and its effects. Postcolonialism challenges ideologies and structures of power that stem from Western hegemony and analyses everyday encounters to determine how notions of race, class and gender intersect and continue to oppress certain groups of people (Mohammed, 2006, p.100).

Fox-Keller (1985), cited by O’Mahony and Donnelly (2010, p.444), describes the essence of feminism as viewing gender as a basic organizing factor that is shaping the individual life conditions. Postcolonial feminist theory again, according to Tyagi (2014, p.45) is concerned with the representation of women in once colonized countries and in Western locations. Rajan and Park (2010) describe postcolonial feminism as “an exploration of and at the intersections

of colonialism and neo-colonialism with gender, nation, class, race, and sexualities in the different contexts of women’s lives, their subjectivities, work, sexuality, and rights” (p.53).

Postcolonial feminist theory reflects the relationship to white feminism. Tyagi (2014, p.47–49) argues that white feminists have overlooked racial, cultural and historical conditions in their eagerness to voice the concern of the colonized women. By imposing white feminist models on women of Global South, they by themselves have worked as an oppressor. Rajan and Park (2010, p.67) highlight that postcolonial feminism attends to understand the legacy of colonialism and neo-colonialism as one of the most important obstacles for attainment of the more egalitarian world.

When viewing female circumcision and anti-FGM discourse from the postcolonial feminist perspective, there is a need to acknowledge how the discourse is shaped by and recreating the

15 imperialist views of Westerners and how even the idea of sexuality is culturally constructed. Njambi (2000, p.177.) refers to Escobar (1989) in arguing how representations of female circumcision systematically organises those who are not Western and white according to European constructs. This “othering” of people dictates “them” to be “out there” and perpetuates the image of West as superior. Generally feminist discourse empowers women to make choices for themselves, but anti-FGM discourse, despite of its significant feminist component, perpetuates the colonialist attitude that non-white women require outside intervention for social change to occur (Njambi, 2000, p.176).

4. Methodology

This chapter introduces CDA which is used as a method for the research. CDA was chosen as a research method as it is a tool developed to analyse the use of language of those in power and the way discourses produce and reproduce social domination (Wodak, 2013). Research questions “In which ways the Journal for Midwives is contributing to the creation of readers’

bias regarding circumcised women?” and “How is sexuality of circumcised women addressed in the journal?” aim to find answers from the use of language of those having social power.

Van Dijk (1993, p.255,279) argues that CDA only makes contribution to social analysis if it is able to provide an account of the role of language, language use, discourse or communicative events in the reproduction of dominance and inequality. In addition to the analysis, this thesis aims to challenge the prevailing discourses and to offer alternative ways of representation which challenge the existing inequalities. According to Van Dijk (1993, p.252) the researcher must take an explicit socio-political stance and state out their perspective and aims. Breeze (2011, p.520) as well states that CDA requires clearly defined theoretical background and the point of view of the researcher must be defined. For this reason, the research presents postcolonial feminist theory which is used as a lens for the analysis. In addition, a separate chapter is dedicated discussing the position of the researcher and how it is reflected from the study. According to Breeze (2011, p.521) researchers must also pay attention to the reception of the text, and how the readers’ response might vary and be different than the interpretation of the researcher. This is taken into consideration in chapter 6.2.

16 4.1. Critical discourse analysis (CDA)

CDA is an analytical research that studies the way social power abuse and inequality are put into practice, reproduced, legitimated and withstood by text and talk in the social and political context. It does not only explicit relationships between discourse, power and ideologies, but it also aims to apply in practise the research results. (Van Dijk, 2012 cited by Wodak, 2013). The analytical aim of CDA is to systematically research the relations between text, discourse and social context as well as to analyse how those are formed by and representing existing power relations. Analysis includes linguistic description, receiving and producing discourses and reflection of social contexts in relation to text. (Pietikäinen, 2000, p.208–209.) As important as the content of the text, is what is missing from it, including representations and participants that are excluded. Each discourse describes and organises views, beliefs and notions of the world, events and people and therefore discourses build or challenge ideologies and create or maintain selected and limited views of the world. (Pynnönen, 2013, p.19–20.)

4.1.1. Fairclough’s three-dimensional approach

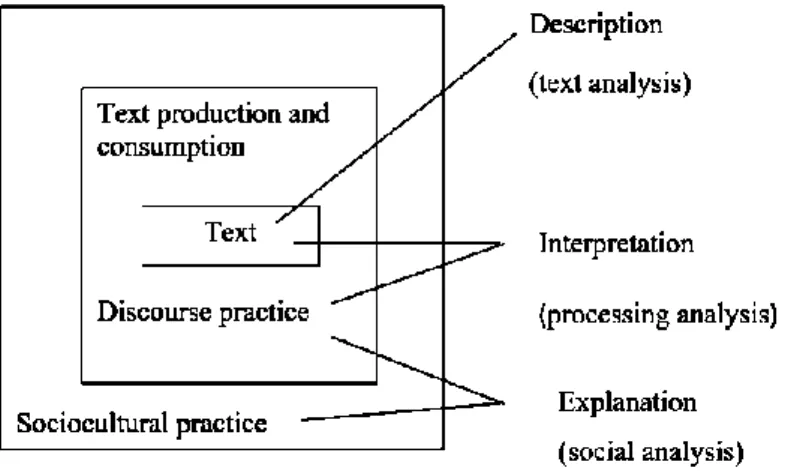

Fairclough (1995, p.98) approaches CDA from three different levels: (1) the actual text, (2) production, distribution and consumption of the texts and (3) the social context which may have influenced the creation of the text and to which the text influences. Figure 1 presents a graphical representation of this process.

Figure 1. Fairclough's critical discourse analysis framework (Fairclough, 1995, p.98).

At the text level, the focus is on describing the contents and language of the text in itself. In intertextual level the analysis is linguistic and descriptive in manner with the aim of studying what is represented in the text. Discursive level analyses how social actors interpret events and

17 how it impacts on the production and consumption of texts. Social analysis explains the wider socio-cultural, political, ideological, institutional and historical context and structures surrounding the text in order to understand how texts are produced and consumed and how text itself impact on sociocultural practices.

4.1.2. Researcher’s position

By doing CDA researcher does not aim for universal answers or facts (Pynnönen, 2013, p.35). Discourses are always analysed from certain discursive positions, from some partial fixations of meaning and there is a major power in the discourse of the researcher (Baaz, 2005, p.171). CDA demands the researcher to be reflective of one’s own use of language and research results. Researcher also participates in the construction of discourses by using language and producing text. (Pynnönen, 2013, p.35–36.) The use of postcolonial feminist lens in research is as well defined by the researcher’s own position in society and researcher’s race, class, gender, and culture is acknowledged and incorporated into the research analysis (O´Mahony & Donnelly, 2010, p.442).

CDA of this thesis is made from the perspective of a white Northern European ciswoman, born and raised in a country ranked as one of the most gender equal place in the World (World Economic Forum, 2019. p.6). The viewpoint is also coloured by the facts that I have worked in some African countries, organised an African film festival in Helsinki with the strong key theme being Africa represented by Africans and raised alone my non-white daughter whose family background is in one of those communities that traditionally practise female circumcision. This certainly does not give me an eligibility or understanding of diverse cultural norms and habits, or experiences of colonialism and racialization, but instead, variety of life experiences have awakened my interest in such topics. As a midwifery student I also have a first-hand experience of how female circumcision is taught to healthcare professionals in Finland. My personal experiences and conversations I have had in the hospital world provoked the interest to study how the attitudes of healthcare professionals are formed, whether professional healthcare journalism is participating in reproduction of stereotypes and bias, and how professional journalism is supporting the aimed social change and development.

This thesis does not aim for universal answers and is most of all a project of self-reflection. The aim is to challenge prevailing discourses and create discussion by offering alternative ways of

18 representation and communication. Selected articles are analysed with the knowledge based on the literature review, screened through postcolonial feminist theory and reflected from my own personal position.

5. Research data

The research data was collected from the publications of the union journal of the Federation of Finnish Midwives from the past 19 years. The journal is a professional paper meant for midwives and students of the field. The first issue was published on the 1st of January in 1896. The journal is sent to each member of the union as well as to several libraries, universities, hospitals and other collaborators. Currently the journal is 32-36 pages and copies are approximately 4000. (Kätilölehti - Tidskrift för Barnmorskor, n.d.) The original intention was to go through journals from the beginning of 1990s when the first groups of Somali immigrants arrived and Finnish midwives encountered the first circumcised women. However, due to ongoing renovations and changes in University libraries, the older journals were not available. This limited the research data to cover only the 21st century.

One methodological challenge with CDA, related to research data, is to avoid choosing only the text that best fits the assumptions and theory of the researcher (Wodak, 2013). The public media representation and anti-FGM discourses have been researched over the years offering various perspectives to approach the topic. The interest in this research was not the mass media representation of female circumcision, but how professional health journalism contributes in recreation of inequalities and stereotypes. The interest of sexual health and representation of sexuality directed the decision to choose journal targeting midwives.

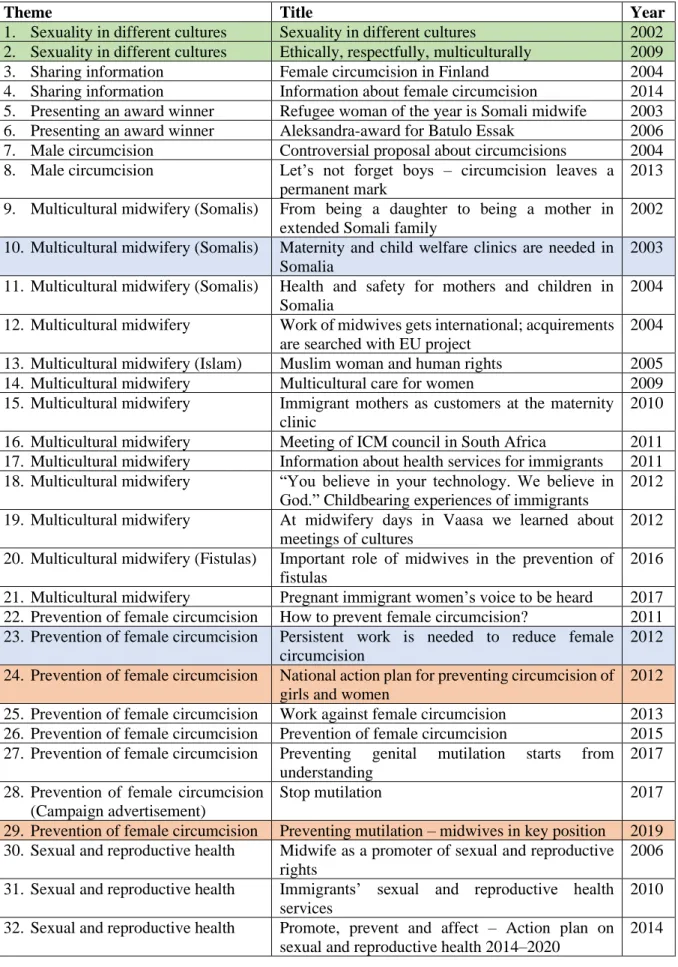

Between the years 2000 and 2019 the journal published 10 articles that directly focused on female circumcision and 22 articles that addressed it in addition to other content of the articles. Apart from these, the journal published 5 articles about trans/multicultural care written in Swedish which mentioned female circumcision. Due to the language I decided to leave these articles out of the research. At first the collected articles were organised by themes. 32 articles which were written in Finnish, published during the years 2000-2019, are presented in Table 1.

19

Theme Title Year

1. Sexuality in different cultures Sexuality in different cultures 2002 2. Sexuality in different cultures Ethically, respectfully, multiculturally 2009 3. Sharing information Female circumcision in Finland 2004 4. Sharing information Information about female circumcision 2014 5. Presenting an award winner Refugee woman of the year is Somali midwife 2003 6. Presenting an award winner Aleksandra-award for Batulo Essak 2006 7. Male circumcision Controversial proposal about circumcisions 2004 8. Male circumcision Let’s not forget boys – circumcision leaves a

permanent mark

2013 9. Multicultural midwifery (Somalis) From being a daughter to being a mother in

extended Somali family

2002 10. Multicultural midwifery (Somalis) Maternity and child welfare clinics are needed in

Somalia

2003 11. Multicultural midwifery (Somalis) Health and safety for mothers and children in

Somalia

2004 12. Multicultural midwifery Work of midwives gets international; acquirements

are searched with EU project

2004 13. Multicultural midwifery (Islam) Muslim woman and human rights 2005 14. Multicultural midwifery Multicultural care for women 2009 15. Multicultural midwifery Immigrant mothers as customers at the maternity

clinic

2010 16. Multicultural midwifery Meeting of ICM council in South Africa 2011 17. Multicultural midwifery Information about health services for immigrants 2011 18. Multicultural midwifery “You believe in your technology. We believe in

God.” Childbearing experiences of immigrants

2012 19. Multicultural midwifery At midwifery days in Vaasa we learned about

meetings of cultures

2012 20. Multicultural midwifery (Fistulas) Important role of midwives in the prevention of

fistulas

2016 21. Multicultural midwifery Pregnant immigrant women’s voice to be heard 2017 22. Prevention of female circumcision How to prevent female circumcision? 2011 23. Prevention of female circumcision Persistent work is needed to reduce female

circumcision

2012 24. Prevention of female circumcision National action plan for preventing circumcision of

girls and women

2012 25. Prevention of female circumcision Work against female circumcision 2013 26. Prevention of female circumcision Prevention of female circumcision 2015 27. Prevention of female circumcision Preventing genital mutilation starts from

understanding

2017 28. Prevention of female circumcision

(Campaign advertisement)

Stop mutilation 2017

29. Prevention of female circumcision Preventing mutilation – midwives in key position 2019 30. Sexual and reproductive health Midwife as a promoter of sexual and reproductive

rights

2006 31. Sexual and reproductive health Immigrants’ sexual and reproductive health

services

2010 32. Sexual and reproductive health Promote, prevent and affect – Action plan on

sexual and reproductive health 2014–2020

2014

20 Articles with the main theme being female circumcision mostly focused on the preventative methods. Articles that mentioned female circumcision were mainly about multicultural midwifery either in Finland or in an international context, three of the articles discussing specially about Somalis and one about Islam. All of the articles about prevention of female circumcision were published after the year 2010, most of the other articles before. The time frame also creates its own characteristics to the research as the political and sociocultural atmosphere in Finland was different 20 years ago. Communication technologies have developed and the way information is shared has changed. This offered another aspect to the analysis and is discussed in chapter 6.3.

All 32 articles were included in the research and examined throughout the analysis. However, since one of the key interests of the research was sexuality of circumcised women and how it is constructed and interpreted as well as represented for midwives, for closer analysis two articles (1 & 2) about sexuality in different cultures were selected. These are highlighted with green in table 1. In addition, since CDA studies how also institutionalised social power and inequality are put into practice, reproduced and legitimated by text, two articles (24 & 29) that present the national action plans for preventing circumcision of girls and women, published by STM were also selected for closer textual and processing analysis. These articles are highlighted with red in table 1. In the processing analysis the study also focuses on two articles (10 & 23) chosen based on their authors. One was written by Western NGO representative and the other one by Somali midwife. Those are highlighted with blue in table 1.

6. Analysis

The analysis is separated to textual, processing and social analysis according to Fairclough’s three-dimensional concept, presented in chapter 4.1.

6.1. Textual analysis

Visuality was considered as a part of the text and was analysed in descriptive manner. In the analysis of vocabulary and grammar, word choices, word meanings, lexicon and modality of texts were examined. Analysis of the text structure dealt with coherence, macrosemantics and representation.

21

Visuality

Article 1, “Sexuality in different cultures”, was pictured with two pigeons of different colours. The picture could be understood to illustrate how we are similar despite the way we look like. In this sense the content of the article was contradictory as it highlighted the differences between people from different cultures. The way a person looks like does not define one’s cultural identity and therefore picturing article which represents cultural differences with different looking birds, contributes in reproduction of stereotypes and evaluation of other people based on their exterior.

Article 29, “Preventing mutilation – midwives in key position”, was visualised with symbols of broken women whose pieces were scattered to several pages (see cover of this thesis). National action plan for preventing FGM, which the article was about, writes about the media representation of female circumcision and mentions that the media should avoid highlighting

“the suffering of the victims of mutilation” (Koukkula & Klemetti, 2019a, p.60). Yet the article

itself was visualised with broken women and pieces of them scattered all over, reinforcing the notions of broken womanhood. The whole journal had renewed its outlook and it had become more magazine like. Fourth article was the only one where the name of the illustrator, Riikka Käkelä-Rantalainen, was mentioned.

Visuality of other articles varied a lot. Different types of reports from Global South or meetings included pictures related to the situation. Covers of information booklets were present in few articles, giving formal outlook for the articles. Many articles about multicultural care and healthcare of immigrants contained pictures of black women or couples. One article was pictured with a stork carrying a black baby. According to Kreuter and McClure (2004, p.440) in both practice and research, culture is commonly conflated with race and ethnicity, especially for non-majority populations. Picturing immigrants always black creates an image that immigrants always come from Africa and enforces stereotypes that non-white people in Finland are always immigrants or representatives of a “different” culture. Contradictory, majority of immigrants in Finland are from former Soviet Union and Estonia (Tilastokeskus, 2018).

22

Picture 2. Article “Sexual and reproductive health services for immigrants” was pictured with two non-white woman-man couples (Kettu, 2010, p.9).

Two articles about female circumcision were pictured with flowers, old symbols of female genitals and sexuality, and one with a Somali woman holding a booklet about female circumcision. One article about female circumcision involved rather dark picture of two Somali women, other one holding a leg of someone, apparently presenting the situation where circumcision takes place. One “Save the pussy” campaign advertisement was visualised with hand holding a dirty knife (picture 2). Instructions for visual presentation of female circumcision advice avoiding reinforcing negative stereotypes and showing used instruments due to their negative impact in the minds of the audience. (UEFGM 2016; UNFPA-UNICEF 2016 cited by Koukkula & Klemetti, 2019a, p.60–61).

23

Vocabulary and grammar

Article 1 used the term “female circumcision” except when talking about men. Somali men were told to penetrate through “mutilated” and “sewn” vagina, and to prefer “non-mutilated

women”. Non circumcised girls were described to be “whole”. Words “hidden” and “mysterious” were linked to sexuality and words “torture” and “rape” were also mentioned

in relation to sexuality and Islam. The article used active sentences making it less formal and detached. Article 2 talked about “female circumcision” and “circumcision tradition”. Article 24 presented all used terms; “female circumcision”, “female genital cutting” and “female

genital mutilation”. After arguing why, it used female circumcision throughout. Article was

neutral and formal with its vocabulary and grammar.

In the article 29, the term “mutilation” was consistently and continuously used, even when it could have been left out without influencing the meaning of the sentence. Word “mutilation” was used 77 times in the article. Highlighted was a part of a sentence “If there is a suspicion

that family plans to mutilate their daughter,…”, where the representation of the matter was

stressing the family being the one posing the violence on the child. Geographically the article discussed about “Africa”, “Middle East” and “Asia” in comparison to “Western

understanding”. When discussing about the health consequences, the article used terms like “danger is”, “are possible” and “might cause”. About the recommended treatments, terms

like “would be good”, “can be offered” and “it would be optimal” were used. Then again, when talking about the role of midwives, the modality was much higher and the word “must” was used continuously. It was made clear to the reader that it is your responsibility to act. There was no consistency in the journal, whether “female circumcision” or “female genital

mutilation” should be used. Some articles used the term “circumcision” when discussing about

circumcised women and switches to “mutilation” when talking about the preventative work. Some articles used different terms mixed. It seemed like it is really not clear which term is appropriate. In the first National action plan for preventing circumcision of girls and women, term “circumcision” was used and recommended among healthcare as it is neutral and respective. The second National action plan for preventing FGM, had switched to the term

“mutilation”, likely due to the recommendations of WHO and UN for emphasising preventative

work. From postcolonial feminist perspective, the label “mutilation” is problematic and filled with colonial tones. Olajubu (2003, p.100) raises the question “who calls it genital mutilation”,

24 people practicing it, or those who do not have comprehensive understanding of the sociocultural context, those observing it from the outside? Who even has a right to define another person mutilated? (Considering terminology, translation can be a bit problematic. It is worth to mention that in Finnish language there is no proper translation for English term “female genital cutting” as “cutting” has the same translation as “surgery” and therefore in Finnish either circumcision (ympärileikkaus) or mutilation (silpominen) is used.)

“Human rights” was mentioned in almost every article, many also referred to the “criminal law” as rhetorical methods to appeal to the ethics of the reader and to stress the Western

perspective towards female circumcision. Some articles did not use the word “midwife” when talking about women who assist in childbearing in Global South, as if they were not qualified for what they do. Most articles talked about “immigrants”, few times “minorities” was mentioned. Reference to “developing countries” and “patriarchy” was present in three articles about circumcised women. One advertisement promoted campaign “Save the pussy – Stop

mutilation”, re-enforcing white saviour attitude by inviting readers “to save” women “out

there” from being “mutilated”.

Text Structure

Article 1, “Sexuality in different cultures” had a pretty broad title as it only dealt with the sexuality in relation to Romani people, Somalis and Islam. The ingress explained how Finland was becoming more multicultural and knowledge about other cultures is needed. Mood of the ingress was formal but the actual content of the article was quite the opposite of culturally sensitive. Part of the article translated:

“Somalis in Finland

Somalis were the first immigrants who came to Finland and whose culture was strange and weird to us. Almost all Somali women are circumcised, which caused, especially in the beginning, problems with attitudes for example towards childbearing. Childbearing of Somali women was learned to be handled by doing episiotomy for the both sides. After especially radical circumcision, childbearing is managed with caesarean section.

It is part of Somali culture that at the wedding night the husband penetrates through the mutilated and sewn vaginal opening. That is the measurement of the manhood. Tradition might frighten and distress young men, they are afraid whether they can do it. Often some sharp weapon is needed, and it is a part of the tradition that after the wedding night, bloody bedsheet is an evidence of the entry to the vagina.

25

Circumcised women are approximately 130 million in the World, while the tradition lives in about 30 West, Central and East African countries. Circumcision by no means is an order of religion, it is a sign of belonging to a community. In poor conditions being part of a community is vital for a woman. Woman is not good enough to be a spouse unless she is circumcised. Necessarily people do not even know what and why is happening. Circumcision might be a rite for entering adulthood or an old habit, which is not even understood to be questioned.”

Somali culture was represented as “strange and weird”, and tradition of the wedding night was described in quite detailed manner. Women were represented as clueless victims who do not even know what is happening to them. The article continued by explaining how soon after arriving to Finland Somalis learn that they can influence on female circumcision. Several men have brought their wives to be surgically restored which the writer deduced to mean that “men

like women who are not mutilated”. This conclusion reflects the mind of the author, as the

conclusion could have as well been, that the husbands deeply care about the wellbeing of their wives and seek medical assistance as it is available in Finland.

The last chapter of the article dealt with contradiction of Islam and Western sexuality. Sexuality was presented to be understood as a drive that might cause mental and physical destruction if not controlled. Women’s sexuality was mentioned to be strictly guarded and spouse chosen by parents. Even though it was previously mentioned “circumcision by no means is an order of

religion, it is a sign of belonging to a community”, the chapter about Islam continues by stating

that “Boys are more valued than girls. Apparently due to this as well, the radical circumcision

of the girls has continued, because it has not really mattered whether the girl dies from possible complications”. The article created very generalized image of all Muslims practicing radical

female circumcision and made very derogative statement as if Muslims would not care whether their daughters died or not.

Sexuality was described to be hidden and secretive and women told not to initiate. Next the article stated that sexual torture is common in Iraq and Iran for example in prisons: women are raped and electricity is led to male genitals. As stated in the ingress, the aim of the article was to create more cultural understanding and respect in multicultural Finland. However, the way it represented the sexuality of “the other” was not a sensitive one but rather highlighting the most brutal and savage things like sexual violence in prisons.

26 Article 2, “Ethically, respectfully, multiculturally”, a book review, with its title, reflected the willingness to promote culturally sensitive healthcare. The beginning of the article continued this same theme by noting that no matter how sincerely healthcare professionals might act, it can still be hurtful or even humiliating. The article ended with a sentence: “This book does not

save the world, but after reading it, one might be closer to the idea that spectrum of cultures is a richness”. The text represented the wish to raise awareness of multiculturalism and different

ways of being and experiencing the world. However, as Monk (2008), cited by Hernández and McDowell (2010, p.30) notes, multicultural healthcare places groups of people in categories using a predominant view of ethnicity. Also, the article represented the chapter about Lutheran church and sexuality as home-like and being highly different from the others, creating a gap between “us” and “them” while normalising “our” view of sexuality.

Article 24, “National action plan for preventing circumcision of girls and women”, had a formal tone and outlook. The ingress presented the action plan and its goal to prevent female circumcision and to improve the wellbeing and quality of life of circumcised women. Legitimation of the action plan was present within the first two sentences of the article: “Female

circumcision or genital mutilation in all of its forms violates human rights. Practise is one of the forms of violence towards girls and women and it is prohibited by the criminal law of Finland”. Moral appealing immediately awakened the readers negative approach towards the

traditional practice. The article defined female circumcision as “all cultural or other

non-medical operations that involve female genitals’ partial or complete removal or injuring”.

Article 2 raised a question of the contradiction between female circumcision and cosmetic genital surgeries. This was ignored and left out of from every other article, also from the article 24, even though the offered definition clearly would involve cosmetic genital surgeries performed in Western countries. The article highlighted the importance of cultural sensitivity and support of the dignity and privacy of circumcised women during health examinations. Deinfibulation was recommended for asylum seekers only after granted asylum in order to avoid possible problems back in the country of origin. Overall the article dealt with the topic with a sensitive and professional manner, avoiding strong rhetorical methods. Sexuality of circumcised women was not discussed.

Article 29, “Prevention of mutilation – midwives in key position”, already in its title stressed the preventative work. Ingress of the article started by stating that due to the migration, ancient

27 tradition has spread around the world, and continued by presenting the number of circumcised women in Europe and in Finland. This drew the attention of the reader and directed how the rest of the article is approached. Next subtitle was “health detriments of mutilation” following subtitles related to deinfibulation and reconstructive surgeries, creating a narrative of a harmful tradition hurting women, but who can be fixed by modern medicine. Next subtitles concerned

“preventative methods in midwifery” and “the new National action plan for preventing mutilation”, giving solutions for the problem first presented. Third page presented large key

numbers related to female circumcision, pieces of broken women below them, creating dramatic mood for the text (picture 3).

Picture 4. Amounts of circumcised women in Europe and in Finland (Koukkula & Klemetti, 2019b, p.10).

The article represented circumcised women as victims of a tradition which has been there to control their sexuality, protect from pre-marital sex and to prepare for marriage. The article discussed about the health detriments of circumcision mainly describing the potential consequences of infibulation, which in reality covers approximately 10 % of the female circumcision cases (WHO, n.d.). The practice and reasons behind it were simplified and generalised. Sexuality of circumcised women was also represented from the supposition the woman has gone through infibulation. Dyspareunia and decreased sexual desire as well as possible post-traumatic stress reaction and “horror during the intercourse” were mentioned. The article did not mention that not all women experience problems with their sexuality and the majority has satisfying sex lives. Constructive surgeries were mentioned to possibly increase sexual wellbeing and pleasure but support for gender identity and womanhood are also essential

28 part of the procedure. The text did not consider the possibility that challenges with gender identity and feelings of lost womanhood might be caused by the surrounding discourses and attitudes rather than the actual circumcision. This opposes the holistic approach to sexuality. As Johnsdotter (2019) states: “There is something deeply disturbing about societies telling

women that they are mutilated and not fully feminine, and then offering them a solution that involves a knife” (p.23).

The article ended with comparison: “Among the communities that practise the tradition, female

genital mutilation has been seen as a protective and good thing for the child. According to Western view, mutilation is abuse of the child, crime and violation of human rights. Finding a common understanding between these two extremities takes time.” The National action plan,

which the article is referring to, writes: “Journalists should avoid creating “us against them”

or “here against there” notions” (Koukkula & Klemetti, 2019a, p.60). The article failed in

what is guided in the action plan it was promoting. Finding the common understanding again, seemed to be expected from the “others”, as no steps towards more sensitive approach was taken, rather the discourse and legislation had become more judgemental. Compared to the article 24, which presented the previous national action plan, article 29 created much more dramatic mood and used different methods to legitimate its message and to appeal to the readers emotions. Legitimation represents certain matters as positive, ethical, necessary or acceptable and others negative, harmful or morally questionable, and uses for example strategies of normalisation, rationalisation and arguments based on emotions and moral, authority or inevitability (Pynnönen, 2013, p.11). Appealing to human rights, legislation and international conventions were ways the article legitimated its content. The article was written by health experts for professionals of the field and therefore could be categorised as specialist article, however the visuality and different tools to create more dramatic mood for the text, were closer to a style of a magazine article.

According to Van Dijk (1993, p.263), justification of inequality uses positive representation of the own group and the negative representation of the “others”. Different models are being expressed to create the contrast between us and them, for example emphasizing our tolerance, help or sympathy while focusing on negative cultural differences of them. Many of the well-meaning articles about multiculturalism stumbled to this by presenting negative cultural habits of the “other” and highlighting “our” sensitivity, sympathy and help for the circumcised

29 women. One strategic way to emphasize the generality of expressed attitudes is by stating that the current model is typical and that negative actions of the “others” cannot be explained or excused (Van Dijk, 1993, p.264). Consistently most of the articles stated that “female

circumcision is a form of violence towards women and is globally considered violating human rights”. “Globally considered” raised a question whose opinion is needed for something to be

so called “global opinion”.

Different reasons that were stated to be behind the “ancient tradition” were “religion”, “various

beliefs about dirtiness or growth of female genitalia”, “fear of libido”, “women being immoral or dangerous with clitoris”, “sustaining virginity”, “moral norms”, “aesthetic reasons”, “economic and social reasons”. Only one article mentioned that circumcision can have

important meaning for women for example related to their sexual and gender identity. Rather mostly it was highlighted that other people decide about the bodies of women, making all circumcised women look like victims who have no control over their lives. “Social position of

women” and “patriarchy” were mentioned in relation to women being incapable of

understanding their situation because of the social inequality. Referring to patriarchy and gender equality were tools to engage the reader to stand against female circumcision. However, social systems are diverse in communities practicing female circumcision. As Tyagi (2014, p.47–49) argues, when social structures are judged by Western standards and racial, cultural and historical conditions are overlooked, Western feminists are working as oppressors by imposing white feminist models on women of Global South. This discursive oppression can be seen as what Spivak (1988) referred to as “white seeking to save brown women from brown

men” (Earp, 2016, p.120).

6.2. Processing analysis

This chapter focuses on the contexts surrounding the production and consumption of the texts. Discursive production and reproduction of power result from social cognitions of the powerful, in this situation the authors, the publishers and the social structures behind them. Social relations, beliefs, attitudes as well as goals of people and institutions were taken into consideration in relation to text production and consumption. Also, the consequences for the minds of recipients and various ways to interpret the text was analysed.

30

Text production

Some articles included the title of the author, some did not have even the name written. Healthcare professionals, NGO representatives, researchers, healthcare students and the editor in chief were the most common authors.

The articles included results of two bachelor’s thesis about female circumcision and immigration as well as two dissertations related to Somalis in Finland. The focus of the Universities when directing topics for thesis also impacts on the articles published in the journal. For example, at the moment Metropolia University of Applied Sciences, points thesis topics for midwifery students based on the offers of the collaborators. In that way the needs and interests of the collaborators direct also the topics of the articles written by students.

Four of the articles were written by the representatives of THL, a research institute operating under STM. Two of these were informing about the National action plans to prevent female circumcision, and two were promoting their website which provides more information about the practise. THL responses to the international conventions and standards and follows WHO’s guidelines and that was reflected from the articles. Compared to an individual midwife, or midwifery student, representatives of THL have more power and articles written by them, are more likely to be published. Their words also carry more power when the titles of the authors are mentioned, therefore it is even more crucial to pay attention, not only to what is said, but how it is said.

One article was informing about “Say No to FGM – female circumcision” booklet, written and published by African Care Women, NGO established by women of African descent. Articles against male circumcision were written by a researcher from the Central Union for Child Welfare and project workers from the project INTACT which educates about the risks and complications of circumcisions. Both of these highlighted the children’s right for bodily integrity and equated male circumcision to female one as a violence against children. Generally, the backgrounds of the authors were visible on the perspectives of the articles.

Two articles about sexuality in different cultures were written by the same author. Internet revealed her to be the current principal of the Emergency Services Academy, former midwife, the former communications manager of the Federation of Finnish Midwives and the former editor in chief of the membership journal. The other article was a review of a book called