Homeownership, the production of urban

sprawl and an unexpected Nightingale

Marvin Sommer

Faculty of Culture and Society

Urban Studies: Master's (Two-Year) Thesis 30 Credits

Number of words: 19.424 Spring Semester 2019

2

Summary

Homeownership, the production of urban sprawl and an

unexpected Nightingale

Homeownership and suburbanisation are two sides of the same coin in the context of

Australia. This thesis explores the housing system that facilitates homeownership under a

framework of institutional path dependence and how that has facilitated spatial patterns of

suburbanization in contemporary Melbourne. Australia has been considered a homeowner

society for the larger part of the 20

thcentury. Living and owning a house on a ‘quarter acre

block’ in one of its major cities is said to have been a virtue even before homeownership was

in reach for the majority of the Australian population. The years after WWII enabled up to 70

per cent of the population to access homeownership tenure. In that, this thesis analyses the

institutional, societal and economic configurations that enabled increased homeownership

provision, but also the historical processes that further facilitated a system around a dominant

tenure. Path dependency theory, developed in the field of historical institutionalism, offers an

analytical toolbox to examine long-term processes. In a broad sense, path dependency refers

to the continuous reproduction of institutional systems in place. The second part of this thesis

examines urbanisation processes in Melbourne, under a framework of institutional and spatial

change. Cities are changing environments that, although, they inhabit determinist and

reinforcing spatial patterns and institutions, transition over time. By looking at historical and

contemporary institutional processes, this thesis examines metropolitan strategies to

consolidate the outward growth in the city of Melbourne. Under the aspect of change, current

challenges to the built environment are presented. A third analysis connects the macro

discussion with a case study of a local housing provider in Melbourne, that in some regards

may be viewed as antithesis to the contemporary building regime in the Australian and

Melbourne context. As the first in-depth path dependency analysis in the Australian context,

this thesis can be viewed as a contribution to the growing body of path dependency literature

with a housing focus that also combines the spatial nature of urban environments.

Keywords: housing studies, path dependency, critical junctures, historical institutionalism,

gradual change, urbanisation, suburbanisation, Australia, Melbourne, Nightingale Housing

3

Acknowledgements

I would first like to thank my thesis advisor Myrto for her continuous encouragement and generous comments over the course of this writing process.

I was lucky to spend some time in Melbourne between 2019-2020. This has inspired me to write about this topic. It is a fantastic city after all.

Further, I would like to express my gratitude to Max and Daniel who have helped greatly with me with their comments and their well intended distractions (and memes). In addition I would like to say thank you to my family and their continuous support.

Studying Urban Studies in Malmö University was a great and inspiring time.

A final shout-out goes out to Soundcloud and Spotify, helping out in the long hours of work (Most streamed: Stephan Bodzin, Shlohmo, Recondite)

4

Table of Content

1. Introduction. ... 5

2. Theory. ... 7

2.1. Path Dependency and self-reinforcing patterns ... 7

2.2. Critical junctures and a theory of gradual institutional change ...11

2.3. Path dependency and gradual change in housing markets ...12

2.4. Homeownership tenure and connection to suburbanisation patterns ...14

3. Methodology ...16

4. Australian Housing system and Melbourne context. ...18

4.1. Australian housing system and affordability concerns. ...18

4.2. Greater Melbourne area...21

5. Path dependency in Australian homeownership provision and spatial and institutional change in Melbourne...24

5.1 Contingent historic conditions ...24

5.2. Developing path dependency ...25

5.3. 1970s until today: Homeownership persists ...27

5.4. Chapter 5 concluding remarks ...31

6. Melbourne’s urbanisation: physical and institutional change ...31

6.1. Suburban layering/legacies...32

6.2. Consolidation struggles and contemporary challenges ...34

6. 3. Chapter 6 concluding remarks...38

7. Case Study: Nightingale Housing – Niche development for homeownership provision ...38

7.1. Nightingale Housing and the Nightingale Housing Model...38

7.2. Chapter 7 concluding remarks...42

8. Discussion and Conclusion ...42

References...45

5

1. Introduction.

Homeownership has long been described as the ‘Australian dream’. Owning a house on a ‘quarter acre block’ in one of its major cities is said to have been a virtue almost dating back to its first colonizers and a pull factor for the migratory waves that have followed. However, housing and homeownership have seemingly grown to become an obsession in contemporary Australia (HSBC 2019). Weekend editions of the major newspaper like The Australian or The Age are filled with property magazines that discuss the current market and present the next auctions in one’s neighbourhood; Tuning on the TV one is overwhelmed by renovation competitions and the like. On the contrary, real house prices have doubled in all major Australian cities since 2000 without incomes following suit (Demographia 2020a). The property markets in Sydney and Melbourne are among the most expensive in the world, but affordability concerns and inflated house prices is an all-Australian concern (Demographia 2020a)

The first part of the thesis is an attempt to understand the historic and institutional conditions that have facilitated a housing system that is a deeply entrenched cultural institution, which stores the vast majority of Australian wealth. And then, there is the aspect of crisis – how has a system emerged that is dominated by one form of tenure – homeownership – which is increasingly inaccessible to a large number of Australians? Homeownership and suburbanisation in the Australian context are strongly connected. Melbourne, the vastly sprawling metropolis is also among the least densely populated cities in the World (Demographia 2020b). In that, it is a megacity by size but not population. The second part of this thesis is looking at the urbanisation process in Melbourne, largely driven by uncontrolled growth of owner-occupied detached housing. Suburbanisation or urban sprawl has been connected to negative externalities, such as excessive land, resource and energy consumption (Kahn 2000; Glaeser and Kahn 2010; Buxton and Scheurer 2007), automobile dependence (Newman and Kenworthy 1999, Batty et.al 2003), and can lead to detrimental health and social outcomes (Kneebone and Garr 2010; Randolph and Tice 2014; Randolph and Holloway 2005) However, others have stressed suburban virtues, showing that it is a very contentious issue (Troy 1996; Gibson 2012). Taking this into consideration, the third part of the analysis is examining a profit for purpose housing provider in Melbourne, Nightingale Housing Pty Ltd1, which has the goal to provide affordable and sustainable apartment housing – in many

ways the antithesis to the current Australian housing regime.

This thesis aims to explore the housing system that facilitates homeownership under a framework of institutional path dependence and how that has facilitated spatial patterns of suburbanization in contemporary Melbourne. The core idea of institutional path dependency refers to persistent institutional systems that emerged from initially contingent events. In the long-run self-reinforcing processes induce interdependent institutional systems which act constraining on possible choices, outcomes and system

6 efficiency. In a broad sense path dependency is a way to conceptualize history. Housing systems comprise a wide system of institutions, and their durable spatial properties are prone to persist over long periods. Path dependency analysis is placed within the historical institutionalist research field. Key contributions employed for the theoretical background are derived from Mahoney (2000) and Pierson (2000). Mahoney (2000) has developed the functional, power and legitimation explanation for institutional reproduction, which are employed in the analysis of the Australian housing system. Pierson (2000) has conceptualised path dependency and self -reinforcing trajectories for the study of political institutions. Shortcomings in the theory of path dependency to understand change, have been placed within the concept of critical junctures by Capoccia and Kelemen (2007) and a framework for gradual institutional change by Mahoney and Thelen (2010). Path dependency analysis of housing systems has been largely developed by Bengtsson and Ruonavaara (2010). Bengtsson et al. (2017) have examined path dependency in housing systems and homeownership in the context of Finland, Sweden and Norway. Bengtsson and Kohl (2018) have furthered the framework developed by Mahoney and Thelen (2010) for analysing change in housing systems and the built environment – and applied it to the German and Swedish context. Malpass (2011) has researched path dependency and change in housing p olicies in the UK. Sorensen (2015) has developed concepts of critical junctures and change to urban environments. Sorensen and Hess (2015) applied the concepts of path dependency and critical junctures in the context of Toronto and Sorensen (2020) has examined historical urbanisation processes and change in the case of Japan. Woodlief (1998) has presented a general theory of path dependency and applied it in the context of New York City and Chicago. Claims for path dependency in the institutional Australian housing context have been made by Pawson et al. (2020) and Burke and Hulse (2010). However, these claims have been made relatively unfounded in theory. This thesis tries to fill this gap in delivering a theory grounded analysis of the Australian housing system and change in urbanisation processes in the context of Melbourne – based on the following hypothesis:

1. Homeownership provision in the Australian context follows a path-dependent trajectory. This is problematised using Mahoney’s (2010) legitimation, power and functional explanation of institutional reproduction

2. Homeownership predominance has impacted spatial patterns in the urbanisation of Melbourne. 3. The cultural, institutional and economic embeddedness of homeownership has prohibited the

ability to change spatial patterns in Melbourne.

This thesis draws in large part on secondary historical literature by housing scholars and historians, primary data such as more recent metropolitan strategy documents, statistical and survey data. Two semi-structured interviews have been conducted for the research on the housing provider Nightingale Housing.

The structure of this thesis is as follows. The following chapter will provide the theoretical background for this thesis, employing in large the theories and frameworks of path dependency, critical junctures

7 and gradual change developed by Mahoney (2000), Pierson (2000) and Mahoney and Thelen (2010). This is followed by a conceptualisation of the housing system or housing markets, mainly based on Bengtsson and Ruonavaara (2010) and Bengtsson and Kohl (2018). Chapter 3 will explain the methodological approach f or this thesis and discuss the underlying material. Chapter 4 gives a context of the Australian housing system and a background on the Greater Melbourne area. Chapter 5 examines the path dependency hypothesis in the Australian homeowner context . It is discussed along the legitimation, power and functional explanation of institutional reproduction. Chapter 6 traces the urbanisation process in Melbourne under aspects of institutional and spatial change. The focus lies on contemporary challenges towards urban consolidation strategies. Chapter 7, that focuses on the housing provider Nightingale Housing, attempts to connect institutional systems at large to the micro and local scale. In the chapter the housing provider will be analysed along with the dimensions of their housing model - Affordability, Transparency, Sustainability, Deliberative Design and Community Contribution – and place it within the context of the previous chapters. The final chapter will discuss and conclude the findings of this research and place them within the frameworks employed in this thesis.

2. Theory.

Path dependency is a concept used for historical analysis of institutions and policies in individual country or cross country analysis (or other units). The concept has been based in historical institutionalism, a social science discipline for institutional analysis, and has been applied predominantly in economical and political studies (Mahoney and Thelen 2010). Claims of path dependency point towards the persistence of institutions or policies over long-time horizons. The basic idea is to conceptualize how and why historical sequences affect the long term persistence of institutions. This theorising body tries to illuminate why there is value in understanding institutions from a historical perspectives. This chapter provides the conceptualisation of path dependency, which will be applied in the analysis of the Australian housing regime with a focus on home ownership. Shortcomings in explaining institutional change will be supplemented with the concepts critical juncture and a framework for gradual institutional change. The latter has been applied to the physical structure of housing systems by Bengtsson and Kohl (2018). It will be used for the analysis of suburbanisation patterns in the City of Melbourne. Finally, housing markets and homeownership tenure in connection to its spatial effects will be conceptualised .

2.1. Path Dependency and self-reinforcing patterns

Path dependency refers to institutional patterns that remain persistent over time, and inherit large cost of reversal. The question then arises, how do the institutional systems reach a stage of lock-in? What mechanism keep the development on a certain path? And how do these systems change the trajectory of their path? Sewell’s general definition presents this basic idea as follows: “… what has happened at an earlier point in time will affect the possible outcomes of a sequence of events occurring at a later point

8 in time.” (Sewell 1991 in Mahoney 2000, 510). At its core, this definition says little more than that history matters, which has been criticised because nearly all processes could be traced under this domain (Kay 2005). This thesis therefore follows a definition presented by Levi (1997, 28):

“Path dependency has to mean, if it is to mean anything, that once a country started down a track, the costs of reversal are very high. There will be other choice points, but the entrenchments of certain institutional arrangements obstruct an easy reversal of the initial choice.”

The entrenchments occur through processes of increasing returns – the economic term describes processes where the probability of continuing steps of a path initially chosen, will increase with every move along that path. Or in other words, once an institution is set on a pattern it reproduces itself through the benefits of increasing returns, but also through increasing costs of reversal. For the purpose of analysis of political or social processes Pierson (2000) suggests using the terms self -reinforcing or positive feedback mechanism instead of increasing returns. These terms are used interchangeable for the remainder of this thesis.

Arthur’s (1994) Polya Urn experiment schematically presents the patterns of path dependency and increasing returns. To understand the Polya experiment, consider a large urn containing a red and black ball. The process starts with one ball being drawn and then returned with a second ball of the same colour. This process is repeated until the urn is full. Characteristic features of path dependency are found in that experiment. In the beginning of the process, there is an element of contingency, in what will happen. The initial step is not fully random because there are only two events that can occur, meaning either a red or black ball being drawn. This aspect is important for the analysis of institutions later on, as choices are constraint in political processes. Additionally, eventual outcomes cannot be predicted from the initial drawing or event. Second, earlier events have a stronger effect on the ultimate trajectory than later events. In the experiment balls drawn at the beginning have a stochastically larger impact on the outcome than later ones. This is characterised as timing and sequencing – at what point in time does an event happen and what is its position in the sequence of events. Sequencing and timing of occurring events are essential for the analysis of institutions and urbanisation patterns (Sorensen 2015). Another characteristic is what Arthur (1994) calls inflexibility: As more balls have been drawn in the Polya Urn experiment, the lesser the possibility to reverse the path that is stochastically likely. Mahoney (2000), refers to this as inertia, which is better suited to describe institutions. Inertia means “once processes are set into motion, and begin tracking a particular outcome, these processes tend to stay in mot ion and continue to track this outcome” (Mahoney 2000, 511). Over time the cost of reversal makes it difficult to leave the self-reinforcing trajectory – the lock-in effect. It should be noted that the Polya Urn is a mathematical experiment and the characteristics described show fairly deterministic and static patterns. The emphasis here is to acknowledge the importance of temporal dimensions in path dependency analysis. After all institutions, although prone to persistency, are dynamic structures, which are shaped and changed by political and social processes over time.

9 For the purpose of this thesis the author follows Hall’s (1986, 19) definition of institutions: “The formal rules, compliance procedures, and standard operating practices that ensure the relatio nship between individuals in various units of the polity and economy”. The notion of standard operating features refers to the way of doing things and more importantly underlying societal norms and values that will become relevant when looking at aspects of legitimacy in path dependency of political processes. Also, worth of value is North (1990, 3) definition: “Institutions are the rules of the game in a society or, more formally, are the human devised constraints that shape human interaction.” The notion of constraints is applicable to housing market institutions and policies, which are considered as correctives to market mechanisms.

The economic arguments for increasing returns have been identified through four key features in the technological sector by Arthur (1994, 112). An example frequently encountered, although contested, is the usage of QWERTY keyboards in range of electronic devices (David 1985; Vergne 2013). The keyboards have become a global standard (lock-in), despite initial efficiency doubts and competing technologies. The keyboard and its inherent properties can be connected to the four key features of increasing returns. First, there are large set-up or start-up cost for new companies and technologies or product innovation (e.g. network of electric charging points for electric vehicles). Second, learning effects in a new technology will spur further innovation as more users learn and apply it (e.g. learning to type on QWERTY keyboard). Third, coordination effects are benefits derived by an individual from the collective activity of others. This encourages coordination around a single option, because it has greater benefit to every user (e.g. iPhone and Appstore that is open for user created apps). Fourth, adaptive expectations, where individuals are basing predictions of future aggregate usage of others into their current expectations or more colloquially referred to as ‘picking the right horse’. Competing technologies such as Betamax and VHS or more recently Blu-Ray discs and HD-DVD discs, inherit the dynamics of adaptive expectations in users and potential users of new technologies. While these key features seem to apply to scale of technological product innovation, there has been robust evidence in the field of economic geography, that path dependency can be found in agglomeration economics (Krugman 1991). One only needs to think of a large systems like the Silicon Valley, to understand the connection to the core features noted above.

The study of political institutions brings with it some characteristic which deviate from the world of economics and market mechanism. Pierson (2000, 257) presents f our characteristics that makes the political realm prone to increasing returns:

1. Central role of collective action 2. The high density of institutions

3. The possibilities for using political authority to enhance asymmetries of power

4. Its intrinsic complexity and opacity (e.g. shorter political time horizons and status quo bias of institutions)

10 Politics, as argued by Pierson, has the predominant task to provide public goods2. Political decision

making is essentially based on authority rather than exchange as in market processes, meaning that the opting out of political decisions is very limited. Collective action in politics induces tendencies of institutions to persist over long periods. Reasons for that are found in the large start-up cost of new organizations. For example, once established, most countries tend to have “frozen” party systems (Pierson 2000, 258). Efficiency that is found in market for goods thro ugh competition and prices can not be emulated in the political sphere, which is less flexible or fluid. Moreover, the development of particular political and social identities is generated through learning and coordination effects, and once established tend to persist tenaciously (Pierson 2000).

Political goals such as winning an election or passing legislation have winner-take-all outcomes that can lead to positive feedback loops, which in turn may induce power asymmetries to further institutional persistence. Political action and outcomes are less clearly linked than consumer choice outcomes: A potential buyer of a car will be able to acquire the car of its choice within a short time frame, constrained through the price, available products and information asymmetries3. That buyer has little need to

coordinate his choice with that of other market actors. In the political process the individual is largely dependent on the collective action of others, which requires coordination and adaptive expectations of other actors’ behaviour. Outcomes of the political process are usually determined over longer time horizons, meaning that the effectivity of institutions and policies are visible only after time has passed. Learning effects in economic markets are mechanism that improve the efficiency of an innovation as more users become accustomed to it. Learning effects in the political process cannot be assumed to occur and inefficient institutions are prone to persist, resulting from political time horizons. The political process makes it less likely for a new party or policy to reap benefits of the inefficiencies inherent in an institution and policy in place. This effect is likely enhanced in larger systems. A key reason for that lies in complex interdependence of institutions. The political cost of switching or creating a new institution or policy is very high, and the benefits might be reaped in the long term, which contradicts with political time horizons that are considered to be generally short term and dependant on election cycles. A final reason for self-reinforcing mechanism brought forward by Pierson (2000, 262) lies in the “Status Quo Bias of Political Institutions”, which are often by default designed in ways that make them difficult to

2 “[Public] goods are characterised by jointness of supply (marginal cost of an additional user is zero or tiny),

and non-excludability (it is very expensive or impossible to restrict users to those who have paid” (Sorensen 2015, 10). Typical examples are environmental protection, municipal infrastructure or legal systems (Sorensen 2015). The characteristics of public good provision necessitate legally binding rules, which are said to be “the very essence of politics” (Pierson 2000, 257).

3 The purchase of a properties, comes with additional constrains on efficiency, such as a heterogenous market

structure with submarkets of unique properties that are bound to location (e xceptions apply in northern Sweden, see Bromwich 2016). Additionally, there is large transaction cost, adverse information and a volatile price cycle (see Coiacetto 2009)

11 change, and thus to persist over long periods. In essence, these characteristics make the political process and institutions naturally inclined to path dependency.

Mahoney (2000) presents four mechanisms of analysing institutional reproduction over time that seem promising for the study of housing systems. Long term persistence of institutions through reproduction can be analysed using the utilitarian, functional, power and legitimation explanation (Mahoney 2000, 517ff). The two latter explanations have also been employed by Bengtsson and Ruonavaara (2010) in theorising path dependency patterns in housing systems. These explanations are not mutually exclusive in its application, and intersect with Pierson’s arguments above. Additionally, mechanisms that induce change are discussed along with these explanations. The utilitarian explanation has been neglected for the use in this thesis. The basic idea for the mechanism behind the functional explanation is that the institution serves an elemental function in a wider system, which cau ses its continuous reproduction (Mahoney 2000). In addition, the institution in question is strongly entrenched in interdependent institutional matrices. Mahoney suggests that functionality of the institution in place might be distorted in the long run. The power explanation functions through institutional reproduction induced by elite actor groups that are in favour of the institution in place (Mahoney 2000). Much like the power asymmetries arising through positive feedback loops in the political sphere presented by Pierson (2000). Finally, the legitimation explanation is employed in systems that persist based on what actors themselves see as legitimate and additionally what is viewed as legitimate in society at large. Dowling and Pfeffer (1975, 126) argue that “[l]egitimacy is a constraint, (…), on organizational [or institutional] behavior, but it is a dynamic constraint which changes as organizations [or institutions] adapt, and as the social values which define legitimacy change and are changed”. While the legitimacy explanation already incorporates an element of change, it is less clear for the power and functional mechanism. Mahoney argues that for change to occur in the power-centred approach, the elite in place has to be weakened in a way that a new subordinate group of actors is able to enforce change. In the functional approach change is induced through an exogenous shock, that has the ability to transform the system. The following section will introduce the concept critical junctures and employ a framework by Mahoney and Thelen (2010), that can be employed to analyse gradual change in housing system.

2.2. Critical junctures and a theory of gradual institutional change

Exogenous shock that alter development pathways are called critical junctures in h istorical institutional analysis (Capoccia and Kelemen 2007). The concept of critical junctures has been defined by Collier and Collier (1991, 29) as: “a period of significant change, which typically occurs in distinct ways in different countries (or in other units of analysis) and which is hypothesized to produce distinct legacies.“ The way these exogenous forces precipitate will depend on the context and institution: the creation of a new technology might be able to disrupt whole industries, while a global pandemic might be able alter previous norms and value systems that gave way to the legitimation of institutions in place. Sorensen (2015, 14) refers to critical junctures as a “window of opportunity”, that can give way to the

12 establishment of new institutions or institutional practices and policies. His article gives emphasis to the importance of major turning points in the trajectory of institutions in the urban realm. However, he goes on to cite Capoccia and Kelemen (2007 in Sorensen 2015, 18): “Critical junctures are rare events in the development of an institution: the normal state of an institution is either one of stability or one of constrained, adaptive change.” In that, change seldom occurs through critical junctures but more so in gradual ways.

Mahoney and Thelen (2010) present a framework that focuses on institutional change occuring through gradual change processes, which eventually may in fact be transformative over time. They argue that institutional analysis has focused on explaining continuity rather than change, in part, because the idea of persistence is inherently incorporated in institutions. However, their approach for institutions builds upon the idea that they are inherent endogenous contestations and fraught with tensions. Thus, institutional outcomes are more the result of compromises, and there is no clear-cut distinction between winners and losers in the process. In that regard, self -reinforcing patterns provide an exception, while the rule proves to reveal more dynamic processes of coalition building and mobilizing political support. Shifting power-balances are endogenous to institutions, in addition to constrains by institutional interdependency. Pierson and Skocpol (2002, 696) argue that evaluating the interplay in sets of institutional processes and power dynamics will prove to be more valuable than solely looking at single process or institution. Beyond power-dynamics, Mahoney and Thelen (2010), argue that, compliance with the codified rules that every institution inherits is an important variable in analysing both stability and change. In essence, compliance gives leeway for interpretation because “(…)[r]ules can never be precise enough to cover the complexities of all possible real-world situations” (Mahoney and Thelen 2010, 11). In short, interpretations and enforcement of rules might entail “gaps” or “cracks” that make institutions, which are constrained by power balance dynamics, prone to incremental change. Their framework builds on four modes of institutional change (Mahoney and Thelen 2010, 15f):

1. Displacement: the removal of existing rules and the introduction of new ones 2. Layering: the introduction of new rules on top of or along side existing ones 3. Drift: the changed impact of existing rules due to shifts in the environment

4. Conversion: the changed enactment of existing rules due to their strategic redeployment In essence, the framework is build around characteristics of power dynamics and compliance with institutional rules. Power dynamics are expressed through veto possibilities (strong or weak), which refers to ability of veto players or formalized veto points to block changes. The other characteristic in place is the level of discretion (compliance) in interpretation or enforcement of the institutional rules

2.3. Path dependency and gradual change in housing markets

The organisation of housing system or housing market regimes has some particularities that are important to be considered for the analysis. The work of Bengtsson and Ruonavaara (2010), Malpass

13 (2011) and Sorensen (2015) are essential for connecting path dependency and analysis of institutional change in connection to the housing sector. Bengtsson and Kohl (2018) have applied the analysis of change to the physical structure of housing systems. Housing regimes, as defined by Kemeny (1981, 13), represent: “the social, political and economic organization of the provision, allocation and consumption of housing”. Additionally, housing system are facilitated in physical structures that are prone to long term stability, as result of their often durable nature (Bengtsson and Kohl, 2018). Unlike public goods, housing could be to an almost full extent provided through the private market (Bengtsson and Kohl 2018). In that light, housing institutions and policies can be viewe d as market correctives, creating the setting of the market (Bengtsson and Ruonavaara 2010). This aspect can be viewed as constraining the possibility for change.

Housing tenures characterise the “basic rights of possession and exchange that are fundamental to a capitalist economy” (Bengtsson and Ruonavaara 2010, 194). Tenure is organised in four main types4 –

outright owning, owning with an outstanding loan, social renting and private renting. The dominance of one form of tenure might enhance power asymmetries, status quo bias and adaptive expectations. Furthermore, housing fulfils a dual function – it serves simultaneously as market commodity and physical shelter, which has characteristics of a social right (Bengtsson 2001). The aspect of physical shelter can induce ‘attachment cost’ on the consumer side, that if aggregated acts as further rigidity in the housing sector, which in turn has implications on the spatial nature of place (Sorensen, 2015). In the market, it serves as consumption and investment good. The aspect of commodity brings about multiple challenges in most housing regimes, and particularly in those countries that have a strong reliance on market actors like the Anglo-Saxon countries. The significance of wealth accumulation through housing creates far ranging interdependencies, that are of special importance where housing acts as complementary building block of pension systems. Generally speaking, outright homeowners need less income in retirement age because of their decrease in housing expenses. Asset-based welfare that promotes homeownership relies on rising house prices in order to ensure its function in the pension system. In that, pointing here to a elemental function homeownership might inherit in the wider economic system. Finally, Bengtsson and Ruonavaara (2010) argue that because housing is distributed in the market, the introduction of new forms of housing tenure, for example co-operative housing, can’t be enforced through political decisions because housing will have to be, in most cases, supplied through market actors who rely on consumer demand. Therefore, a political majority and voter support for a decision have to be complemented by activity in the market. All these aspects noted above indicate that housing sectors incur long term stability and path dependant trajectories.

4 This is a simplified view and it should be noted that other forms exist, such as squatter or co-operative

14 Housing systems can be categorised along four sub-systems: production, consumption, exchange and management (Burke and Hulse 2010). Each with a particular set of institutional structures. North (1990, 95) has described this as “the interdependent web of an institutional matrix”. Housing markets present dense collections of institutions and actors on different scales, which may potentially make them inclined to path dependency and reinforcing patterns. Chapter 4 presents the range of actors relevant in the Australian housing context. Property markets build the underlying frame to these four sub-systems. Coiacetto (2009) describes contemporary property markets as a combination of submarkets with highly heterogenous nature (e.g. residential property market). No property is fully substitutable with another, as result of differences in geographic location and included amenities (Coiacetto 2009). Furthermore, property markets inherit a local and global function at the same time, while housing is consumed mostly locally by its residents. The latter function might not apply to all housing markets, but global wealth accumulation has been strongly tied to property markets (Piketty 2014). Adams (1994, 66) has characterised property markets as “riddled by imperfection and failure”, which provides a rationale for state intervention and planning.

Bengtsson and Kohl (2018) have adapted the framework for gradual institutional scale to analyse the physical manifestation of housing systems. They have adapted the modes of institutional change by Mahoney and Thelen (2010) – layering, conversion, drift, displacement – and described their properties in the physical realm. Bengtsson and Kohl (2018) added a fifth d imension – exhaustion – to the framework to describe the built-in decay that constrains the possibilities of each building. Change occurs in all buildings as they are depreciate over time. Life cycles of contemporary houses are certainly shorter than of historical buildings, but changes occur over longer time horizons than for the most consumable objects. Layering refers to physical additions around the city core. Over time a cities’ gestalt is transformed as more layers are added on the existing physical domain. Conversion describes the rededication of the existing building stock into new usage forms. Drift is characterised as the deliberate neglect from strategic underinvestment in order to exploit residents and/or to drive them out. Displacement of housing structures is based on the co-existence of multiple forms of housing. Strategies of displacement could be the renovation of existing forms of housing into alternative forms, that are imported from foreign or rediscovered ideas, as part of gentrification processes. Urban redevelopment practices also fall under displacement.

2.4. Homeownership tenure and connection to suburbanisation patterns

Homeownership tenure is viewed as a commodified form of housing provision (Doling 1999). Essentially, access to homeownership is constrained by the household’s wealth and income level. In the case the household cannot purchase the property outright, the buyer has to acquire a loan which should be repaid with future income. In most cases, the property serves as collateral for the mortgage, and the security of a household’s tenure depends on its ability to service the loan. At this point, the homeowner is occupier with outstanding mortgage and becomes outright occupier after it has fully repaid the

15 outstanding mortgage. Reaching this stage is very beneficial in countries that have implemented non-taxation of imputed rents5. Imputed rents are hypothetical payments that the owner-occupier would

generate if the occupied property was rented out; The rent that would be generated in that case would be taxed. However, because the property is owner-occupied the owner lives without paying rent and is therefore untaxed. In that stage, the owner occupying household can consume their housing outside the market, and thus have created their own f orm of de-commodified housing (Doling 1999). Tax subsidies, like non-taxed imputed rents, make homeownership a more attractive form of investment than other, taxed asset classes.

The relationship between tenure form and urban structure is based on a study by Glaeser (2011). Glaeser (2011) presents a correlation between low-density suburbanization and homeownership in US metro areas. And, if homeownership is encouraged through federal or state subsidized, as is the case in the US, they subliminally subsidize suburbanisation. Homeownership can be diff erentiated between direct ownership and indirect ownership. A household is considered direct owner if they have acquired their property on a residential lot, most commonly detached housing, where they are solely responsible for renovations etc., but also the sole beneficiary of any capital gains (Bengtsson et al. 2017). Indirect ownership is another form, where a household owns a property, that is part of another property with shared spaces. In that case, the owning household is part of a superordinate legal entity that manages the whole property. This underlying form of ownership is mo st commonly found in multi-apartment housing. This distinction is an important issue because of the connection made between direct ownership and suburban spatial patterns by Glaeser (2011). His empirical work shows a correlation between single-family detached housing and homeownership and between multi-apartment housing and renting in US metro areas. Suburbanisation or urban sprawl refers to the spatial development of urban areas at the urban fringe with lower-densities than central urban areas (Harvey and Clark 1956). Suburban sprawl that follows an decentralized and uncontrolled patterns largely depend upon corrective planning policy to counteract these forces (Batty et.al 2003). Vastly sprawling cities are generally associated negative externalities which are discussed in the context of Melbourne in Chapter 6.2. Finally, it should be noted that the assumptions made in this section might only applicable in the Australian and North American context.

The following section will introduce the methodology and material employed in this thesis, and discuss limitations associated with the applied theory.

5 Most countries are not taxing imputed rents, which has been referred to as homeownership bias (Figaro et al.

16

3. Methodology

Housing theorist Jim Kemeny once stated: “usually one’s own country is the starting point of the research and this tends to impose an empirical reference point, clouding wider comparison” (Kemeny and Lowe 1998, 162). That in some ways is the starting point for the aim of this thesis. By viewing at the Australian housing systems with an outsider p erspective, one can only wonder, about the omnipresence that housing seems to inherits in this country. The historical institutionalist approach used in this thesis has been chosen because it offers an analytical toolbox to allow process tracing for long periods. Pierson and Skocpol (2002, 3) have argued that historical institutionalist “address big, substantive questions that are inherently of interest to broad publics as well as to fellow sc holars”, in that “[t]ackling big, real-world questions; tracing processes through time; and analyzing institutional configurations and contexts” (Pierson and Skocpol 2002, 15) are essential features of this research approach. Methodologically, however, there are many ways to apply the theoretical frames of path dependency, critical junctures and institutional change. This thesis has essentially a mixed-method approach that relies mainly on secondary literature accounts by housing scholars and historians in combination with statistical data and reports that cover long time series of data. For example, accessing the public database Manifesto Project6 that analysed historic party manifestos enabled to examine a long

time-series based on primary data. Using secondary accounts comes with limitations, and in the selecting process, the researcher might be confronted with a verification bias. Generally, the majority of secondary sources are peer reviewed, or come from reputable historians.

The first section of the analysis, the examination of homeownership provision through the Australian context, does mainly employ these methods. The focus is to analyse the institutional configurations but in order to examine macro phenomena such as housing system, considerations have to be made of the socio-cultural and economic conditions that accompany major episodes. Path dependency theory reveals history as a constraining force on governance structures, institutions, and urban regimes, and even when change occurs the choices are essentially constrained by these antecedent aspects. Employing Mahoney’s (2000) explanations of institutional reproduction, enables to look at a wider contextual scope, although he goes without specifying a methodological approach that is well suited for this approach. That aspect impedes the reproduction of the approach used in this thesis, in other countries. Path dependency implies that the path has to begin at some point and that it ends at another. The analysis of the point of departure, characterised under the aspect of contingency, can be broadly defined as “the study of what happened in the context of what could have happened” (Berlin in Capoccia 2016, 118). This thesis has extracted the initial ‘stepping stone’ by evaluating homeownership tenure time series and counterchecked this point in time with historical conditions that showed other possible outcomes and

6 The party manifesto data regarding views on housing tenures and homeownership has been derived from

17 choices (see Chapter 5.1.). However, the selection might be considered as subjective and less grounded in a theoretical framework.

Chapter 6, the second part of the analysis, that examines the urbanisation process draws, in addition to the methods described above, on survey data, strategic planning documents or statistical data from official sources such as the Victorian State Government, the Australian Bureau of Statistics or the Reserve Bank of Australia. The selection of Melbourne as subject matter this thesis follows Flyvbjerg (2006, 229), who stated: “atypical or extreme cases often reveal more information because they activate more actors and more basic mechanisms in the situation studied”. In the Australian context, that is a fitting description for the chosen case city. Naturally, there is variation between cases, but by employing this approach, the findings might show a more polarised picture. As a larger urbanity, with a well-researched history, it also gives the researcher a wider range of material to use. However, by selecting an ‘extreme case’ there is no claim for universality of the findings. Employing Bengtsson and Kohl’s (2018) framework of institutional and spatial change in the urban context has no precedents in research. Using an ‘untested’ framework has inherent difficulties and might prohibit the sharpness of the analysis. Tracing diverging outcomes in housing systems and urban environments in comparative analysis is an often employed approach of path dependency analysis. That exceeds the scope of this thesis. In a broad sense, the analysis of this thesis aims to synthesize findings from secondary publications in combination with data time series and contemporary policy documents. Limitations that arise through the selected method are that they cover long periods. This is justified as path dependency analyses have not been facilitated in the Australian context.

Chapter 7, can broadly be considered as qualitative case research, as it is “an object of interest in its own right” (Bryman 2012, 68). Essentially the analysis examines if the case has wider applicability for the contemporary housing regime in Melbourne and Australia by focusing on the case of Nightingale Housing. Moreover, pointing to Flyvbjerg (2006) again here, and his extreme or atypical cases, the housing provider NH is a clear outlier in the private market. From the urban studies perspective, the researcher would argue, that there is value in looking at the local scale, also to make the research more tangible for the reader unfamiliar with the context. In some ways, it functions as a cross-check to evaluate the challenges that have arisen in the Australian housing system. It might also be viewed as an outlook into future housing provision. The analysis is facilitated in consideration of the five dimensions of the Nightingale Housing Model. As such, the model serves as the frame. For the case analysis of Nightingale Housing, two semi-structured interviews were realized: one with a representative of Nightingale Housing and the other with a local official in Moreland City Council. The first, working in the area of communication for the housing provider. The latter interviewee had been selected for the reason, that the majority of Nightingale Housing buildings have been constructed within Moreland Council. Having these interviewees from the organisation and the public space enabled the opportunity to consider two potentially opposing perspectives. The interviews were held in March and April 2020

18 through video calls, and were recorded for the purpose of analysis. Generally, semi-structured interviews give the interviewer more flexibility in adapting to the interview situation, while also having a structural framework through the interview guide (Bryman 2012). Besides the interviews, the researcher attended a public tour of a Nightingale building in February 2020, that was mainly to gather background information about the case. Other material was largely derived from the official website7, such as

publicly available presentations of the building projects8. The following chapter will present the object

of study for the analysis of path dependency and change in institutional and spatial patterns.

4. Australian Housing system and Melbourne context.

The following chapter is set to give context to the current housing regime in Australia and in particular a description of homeownership as the predominant form of tenure. The chapter touches upon affordability concerns in the current system. Following is a background for the context of the Greater Melbourne area.

4.1. Australian housing system and affordability concerns.

The Australian Housing system includes a range of institutions, different governmental levels and multiple private and non-governmental actors. The majority of constitutional housing responsibilities is held by the six states New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and Tasmania and the two territories Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory in Australia. This entails the land use planning, metropolitan strategies, building regulation, public housing provision and property-related tax settings (Pawson et al. 2020). The Federal Commonwealth Government is not formally responsible for housing matters but has, facilitated , to varying and increasing degree, an active role in housing-related matters, such as subsidies, tax settings, welfare provision and major infrastructure policies (Pawson et al. 2020; Ruming et al. 2014). Local councils’ responsibilities lie between land use planning and development control (Pawson et al. 2020). Other key players that complement governmental entities in the housing policy context are “industry bodies, not-for-profit organisations, universities, private consultancy firms (both large generalists and smaller specialists) and high-level independent authorities, such as the Reserve Bank of Australia and the Productivity Commission” (Milligan and Tiernan 2012, 392)9. State and Federal Governments have implemented several pieces of

legislation that directly or indirectly target the expansion of homeownership. Ball (1983, 341) categorizes them as follows:

• Creating the preconditions for market exchange

7 nightingalehousing.org

8 E.g. presentation of the Nightingale Village available online under vimeo.com/276660386

19 • Attempts to lower the income threshold to ownership

• Supply subsidies and land policies • Tax reliefs.

The housing industry in Australia is a major contributor to annual GDP. The property sector has directly contributed AUD 202.9 billion to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2015 -16, according to a report created for the property industry representative Property Council of Australia10 (AEC Group 2017). That

number reflects 13 per cent of total contributions by all industries for that year in Australia. Additionally, the report states that 1,4 million people are directly emp loyed in the property industry – the largest industry in Australia according to the AEC report. Historically, the industry has played a large contributing role to the Australian economy dating back to the 1880s (Fisher and Kent 1999).

Australia, like other Anglo-Saxon countries, is considered a liberal welfare regime, as defined by Esping-Andersen (1990), where the market is the dominant institution in the allocation of goods and services, and welfare provision is generally means-tested. This has implications for the legal structure of the four common tenure types and accompanying owner and tenants’ rights. A fundamental aspect of tenure right is tenure security, which Pawson et al. (2020, 13) describe as “a residents occupier’s legal right to remain in the dwelling or (…) the level of risk that an occupier may be legally removed (formally evicted) from their home.” Owner occupancy is considered “largely unqualified” for outright owners in solely owned property (Pawson et al. 2020, 13). Restriction for tenure security arises for owners with an outstanding loan, as they rely on future income to service the mortgage. Indirect ownership in multi-occupied properties is restricted through the strata owners’ corporation (Pawson et al. 2020). Private rental tenure is constraint through market rents and tenant selection, limitation of the rental period (usually 6- 12 month), landlord consent for dwelling alterations or pet ownership and the continued occupancy depending on maintaining terms of contract (Pawson et al. 2020). Social rental tenants, “[g]enerally speaking, (…) enjoy stronger rights of occupation as well as lower rents than their counterparts renting from private landlords (…)” (Pawson et. al. 2020, 14). However, public rental through government agencies or not-for-profit providers11 has never been above six per cent of total

housing tenure composition between 1947 and 2018 (see Appendix 1). Housing theorist Kemeny, describes the rental system in Australia, as dualist rental regime, which is found among Anglo -Saxon countries (Kemeny 2006). It is dualist because it mainly consists of private renting and public (social) renting. The latter is only accessible through means-testing. Private rentals are profit-driven, rent setting

10 The definition of the property sector is included in the report (AEC Group 2017, 24ff). The specific definition

makes a cross country definition difficult. Paris (1993) claims, without provid ing figures, that the relative size of the property industry is larger than in otherwise comparable countries.

11 The non-profit sector in Australia was around 16 per cent of all social housing in 2014. In 2009 the Housing

20 is largely unregulated and tenants security is weak (Kemeny 2006).

Figure 1 shows the timeline for housing tenure data from 1947 until 2018 (see Appendix 1 for data). The data differentiates between the four main tenure types and other tenure types until 1991, after that other tenure types are added to the total rental value. Total homeownership rates had been around 53 per cent in 1947 in comparison to 44 per cent of rental tenures. By 1954 total homeownership rates had increased by ten per cent to 63 per cent. Homeownership rate reached its peak in 1966 with 71 per cent. Since the 1960s homeownership rates have remained fairly stable around 70 per cent up until the new millennium when homeownership rates started to slowly depreciate, with an accompanying rise in rental tenure rates up to 32 per cent in 2018. Additionally, since 2000 the rates in outright ownership have decreased nearly ten per cent from 39 per cent to around 29,5 per cent in 2018. Since 2005 homeownership had been predominantly among owners with outstanding mortgage12. Interestingly,

since around 2004 the rise in total rentals is claimed solely through increase in private rental tenure and the public rentals have decreased from 4,9 per cent to 3,1 per cent in 2018 as share of total rentals.

Figure 1. Housing Tenures Australia 1947-2018, percentage shares

Source: 1947-1991: Bourassa et al. 1995, 1994-95-2017-2018 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2019; (a): From 1994-95 onwards ‘Other Tenure type’ included in ‘Total Rental’

The recent trends in housing tenures have largely been related to increasing affordability issues. The slow but steady decrease in homeownership rates and the increase in owners with an outstanding

12 This analysis takes into account all age cohorts. The differentiation between age groups shows that home

ownership is reached at a later stage in life among younger age groups than previous age groups (AIHW 2019). 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Owner without a mortgage Owner with a mortgage Total

21 mortgage have been accounted to rising house prices. Affordability of ho using “refers to the relationship between a household’s (or a person’s) income and the amount spent on housing” (Pawson et al. 2020, 18). The Australian wide median real house price has nearly quadrupled since the 1970s, while over the same period real wages only doubled (Yates 2017). Over the last 15 years, Australia’s major cities have been considered least affordable in the annual survey of affordability by Demographia (2020). The dwelling price to annual income ratio has a present value between six to seven in Australia (Yates 2017). Australia’s major cities Sydney and Melbourne are among the most expensive property markets globally with median property values of AUD 1.026.400 and AUD 818.800 respectively in 2020 (Knight Frank 2020, AIHW 2020). Both cities places third and fourth least affordable in Demographia’s global affordability survey in 2020 (Demographia 2020). Taking into consideration the gross median yearly income in the Greater Melbourne area the dwelling price to income ratio is approxima tely 1113.

Australia, although with decreasing rates, has been a homeowner society for at least the last seventy years.

4.2. Greater Melbourne area

The city of Melbourne is capital of the state Victoria. Legal jurisdiction of the entire Greater Melbourne area covers 9992.5 square kilometres14. Melbourne is Australia’s second largest populated city and is

projected to overtake Sydney by 2026 and reach a population of 8 million by 2050 (Sakkal and Wright 2019, Buxton et al. 2015). The Greater Melbourne area comprises of 32 local councils, from which 14 are governing the established suburbs and 17 are within the Urban Growth Boundary (UGB). The UGB was implemented by the Victorian State Government in the 2002 metropolitan strategy Melbourne 2030 (see Chapter 6.2.). The majority of regulation and services are enacted through the Victorian State Government, that also has power to override local planning decisions. The councils have th eir own elected decision making body. Head of the Melbourne City Council, Lord Mayor of Melbourne fulfils a representative role for the whole Greater Melbourne region. However, there is no legislated metropolitan governance body consisting of elected officials.

In Demographia’s World Urban Areas report (2020) Melbourne ranks as the 34th largest urban area in

the world and as the 968th out of 1.056 most densely populated city15. In that, it is among the hundred

13 Gross median weekly total household income in Greater Melbourne area was AUD 1.438 in 20 16 Census

results. Multiplying the value by 52 working weeks gives a gross total household income of AUD 74.776 AUD for 2016. The ratio is calculated using the median dwelling price to in median yearly income value (AUD 818.800 /AUD 74.776 = 10,95). The calculated value shall be seen as an approximation.

14 The area value is of limited use because it takes into consideration the legal Greater Melbourne jurisdiction

borders, which also includes uninhabited land and that would give a distorted value for density calculations. A more accurate way to determine urban areas are the ‘Urban Centre Localities’ that defines urban areas along continuous urbanised areas (Charting Transport 2016).

15 The Demographia report (2020) estimates Melbourne’s continuous built up area that is within a single lab or

22 least densely populated areas in the world. Charting Transport (2016) estimates that Melbourne has a population weighted density16 of 26 persons per hectare, placing fourth lowest populated urban area

among a ranking of 53 cities17 with a population over one million. Table 2 shows the largest dwellings

types in the Greater Melbourne area for 2016. The majority of dwellings are separated detached houses, in contrast to around 16 per cent multi-apartment dwellings. In connection with Table 4, it is visible that ownership (outright and with mortgage) is most common with detached housing accounting to around 81 per cent. In comparison, renting is most common with living in multi-storey apartments ranging between 65 and 71 per cent. The result here are similar to Glaeser’s (2011) observations about tenure type and correlation to dwelling type in the US. Table 3 shows that over 95 per cent of tenures (owning and private renting) are determined on the housing market and only 2.8 per cent of tenures are characterised social housing beneficiaries outside the market. The population in Melbourne has grown from around 3.5 million in 2001 to 5.08 million in 2019 with an average growth rate of 1.9 per cent (ABS 2020). 80 per cent of the new the population in that time has been absorbed in the outer urban growth areas in the years between 1991 and 2003 (Buxton and Scheurer 2007). Between 2003 and 2013 the largest growth in dwellings has been in the outer suburbs with 63 per cent, in comparison to growth of 24 per cent in the middle and 13 per cent in the inner suburbs (Buxton et al. 2015).

The following chapter will first analyse the Australian housing system and homeownership provision under the aspect of path dependency. In consideration of the aspects presented here, chapter 6 will examine the urbanisation process in Melbourne under aspect of suburbanisation p atterns, and institutional and spatial change, in consideration of the aspects presented here.

Table 1. Dwelling Structure Greater Melbourne

(2016 Census), percentage shares

16 Instead of dividing the total population in an urban area by the entire urban area, which includes also

sparsely populated land. The population weighted density uses urban area divided into parcels (using kilometre grid) and aggregates all parcels into an density average (see Charting Transport 2016)

17 The ranking included 53 cities with a population over 1 million from Europe, Canada, Australia and New

Zealand’s three largest cities.

Dwelling Structure Percentage

Separate house 66,72%

Semi-detached, row or terrace house, townhouse etc. (one or more storeys)

17,06%

Flat or apartment in a one or two storey block

6,06%

Flat or apartment in a three or more storey block

10,17%

Total 100,00% Source: ABS 2017

23

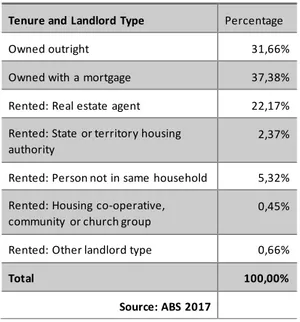

Table 3. Tenure Type and Dwelling Structure Greater Melbourne, percentage shares

Greater Melbourne (2016 Census)

Tenure and Landlord Type Percentage

Owned outright 31,66%

Owned with a mortgage 37,38% Rented: Real estate agent 22,17% Rented: State or territory housing

authority

2,37%

Rented: Person not in same household 5,32% Rented: Housing co-operative,

community or church group

0,45%

Rented: Other landlord type 0,66%

Total 100,00%

Source: ABS 2017

Table 2. Tenure and Landlord Type in Greater Melbourne, percentage shares

Greater Melbourne (2016 Census), Source: ABS 2017 Tenure Type Owned

outright

Owned with a mortgage

Total Owner Rented Other tenure type

Dwelling Structure

Separate house 37,22% 43,49% 80,71% 18,88% 0,41%

Semi-detached, row or terrace house, townhouse etc. with one storey

27,75% 26,62% 54,37% 44,91% 0,72%

Semi-detached, row or terrace house, townhouse etc. with two or more storeys

22,39% 35,44% 57,83% 41,81% 0,35%

Flat or apartment in a one or two storey block

16,15% 18,43% 34,59% 64,91% 0,51%

Flat or apartment in a three storey block

11,12% 17,50% 28,61% 70,96% 0,42%

Flat or apartment in a four or more storey block

11,57% 16,59% 28,17% 71,44% 0,39%

24

5. Path dependency in Australian homeownership provision and spatial and

institutional change in Melbourne

This chapter will assess the path dependency hypotheses for homeownership in the Australian context, followed by tracing institutional and spatial change in Melbourne. The initial step is to single out a point in time where the path to increased homeownership has started. Arthur (1994) had characterised the processes leading to path dependency as contingent events, meaning that other possible trajectories and choice were enabled in the process. Following this initial tracing, the analysis will follow the three explanations of institutional persistence by Mahoney (2000). In accordance with them, the organisational configurations that enabled homeownership as dominant tenure are analysed. The author divides the homeownership institutionalization into two main periods. The first ranging from colonial settlement in the late 18th hundred until the mid-1970s will be examined through the power and

legitimation explanation. The second period from the mid-1970s until today will be assessed mainly with the functional explanation. It is important to “recognise that housing systems in specific countries function within distinctive cultural, political and institutional traditions” (Pawson et al. 2020, 3). By beginning the analysis with early colonialization of the Australian continent, it needs to be acknowledged that the indigenous owners of the Australian continent, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, were violently displaced and largely excluded from the equal participation in housing market that is described in the following chapter up until the late 1960s18 (Pawson et al. 2020) Up until

this day indigenous Australians, experience far lower socio-economic conditions relevant for the participation in the highly commodified Australian housing system (Pawson et al. 2020)

5.1 Contingent historic conditions

It has been argued that homeownership had been a core ideal dating back to the first white settlement in 1877 (Gurran and Bramley 2017, Pawson et al. 2020). Homeownership and resistance to landlordism were continuing ideals of ordinary working people in the late 19th century (Davison et al. 1987). Rates

of homeownership had been at around 50 per cent at the end of the 19th century, which was comparably higher than in other Anglophone countries (Brett 2017). The British building society movement emerged in Australia around the 1840s and enabled easier financing for aspiring homeowners (Ronald 2008). The initial popularity of homeownership among early immigrant European settlers, can in hindsight be viewed as contribution to the building of societal norms and values that foster long-term legitimation. Nevertheless homeownership rates had been almost in parity with rental tenures until after World War II. Recorded in the 1947 Census is a tenure split between owners and renters of 53 per cent and 47 per cent respectively (see Appendix 1). The depression and war years had resulted in a severe housing shortage of approximately 300.000 dwellings (Bourassa et al. 1995). The shortage was a key rationale

18 Indigenous Australian’s were granted citizen rights first in 1967. In the subsequent years Commonwealth and

25 behind the Commonwealth State Housing Agreement (CSHA) - a milestone that led to the creation of a previously basically non-existent public housing stock to 100.000 – 120.000 dwellings from 1945 until 1956 (Hayward 1996; Beer 1993). Additionally, the newly funded Commonwealth Housing Commission (1944, quoted in Troy 2012, 52f) declared that: “a dwelling of good standard and equipment is (…) the right of every citizen – whether the dwelling is to be rented or purchased, no tenant or purchase should be exploited for excessive profit.” In that, the Commission can be viewed as somewhat tenure neutral. Moreover, federally imposed rent controls19 during WWII made rental tenure

financially attractive for households. These instances indicate a level of contingency which is seen as elemental in the path dependency analysis (Mahoney 2000). In that, a variety of tenure outcomes were possible.

5.2. Developing path dependency

The rise in homeownership rates after World War II, then, falls into the second Menzies Government, who led the Labor Party from 1949-1966. Robert Menzies has been attributed the famous quote that “one of the best instincts in us is that which induces us to have one little piece of earth with a house and a garden which is ours; to which we can withdraw, in which we can be among our friends, into which no stranger may come against our will” (Menzies 1942). The quote is still cited today by the Liberal Party officials when promulgating the importance of homeownership for Australia (Ronald 2008; Brett 2017). Menzies had been a proponent of homeownership in Australia for three main justifications (1) democratization of capital by providing a path-towards prosperity for households, (2) homeownership attracts immigration and establishes a connection between newly arrived and good citizenship (nation-building), (3) Encouraging capitalist behaviour and acting as an antidote to foreign ideologies like communism (Kemeny 1986; Ronald 2008; Troy 2000). Under Menzies, several financial instruments20

have eased and supported housing finance. Direct housing finance through public funds accounted up to 30 per cent of all finance in between 1947 and the 1970s, the time homeownership rates rose to its current level (Pawson et. al. 2020). State Government began to sell off their existing public housing stock to increase the state treasury, which diminished the public rental supply. Additionally, one-sixth of private rental accommodation had also been sold off to owner-occupiers between those years, further reducing the overall rental stock (Ronald 2008). The after WWII years are viewed as the foundational years towards the Australian home-owning society. Kemeny (1983, 22), has viewed governmental involvement in support of homeownership in these years as “aggressively interventionist”. An additional

19 The effects of rent control are a contested economic issue, however, Albon ( 1981) concludes that they have

a long-term adverse effect on the supply of private rental accommodation. The increased governmental intervention in public housing supply through the CSHA has additionally been viewed as “crowding-out” the private rental market (Albon 1981, 94).

20 For detailed presentation of the financial instruments see Bourassa et. al. 1995 or Chapter 5 i n Pawson et al.