1

“Civilizations” and Political-Institutional Paths: A Sequence Analysis

of the MaxRange2 Data Set, 1789 – 2013

*(Draft, not for quoting without permission of the authors.)

Max Rånge and Mikael Sandberg max.range@hh.se & mikael.sandberg@hh.se

University of Halmstad, Sweden https://sites.google.com/site/maxrangedat

Abstract

In what sequences have nations changed institutionally in history and does that order matter for later democratization? If so, are there historical-institutional pathways of “civilizations”? These previously neglected research problems are addressed in this paper on the basis of a new, unique, and enormous data set tracking all political institutions and systems in the world monthly since 1789. The aim is both empirical and theoretical: to take steps toward an understanding of the sequential aspects of political-institutional evolution. Results visualize sequences at regime level that show few signs of path dependency. They also show that democracy may emerge in all types of regimes, though at varying paces. Separating religious-majority nations, Muslim systems are less affected by democracy diffusion than other religious-majority nations. Muslim political systems also exhibit larger regime type unpredictability. Taken together with estimates of GDP per capita, majority religions explain a minor share of discrepancies between regime types: wealth of nations is more important than majority religion on a general, regime type diversity level. However, specifications of institutional details will have to be made in future research in this new area of historical political-institutional study.

Presented at the American Political Science Association Annual Meeting 2014 in Washington D.C., August 28-31, 2014

*

We wish to thank Halmstad University, HOS (School of Social and Health Sciences), and CESAM (Centre for Social Analysis) for supporting this project.

2

Introduction

In what sequences have nations changed institutionally in history and does that order matter for later democratization? If so, are there historical-institutional pathways of “civilizations”? These previously neglected research problems are addressed in this paper on the basis on a new, unique, and enormous data set tracking all political institutions and systems in the world monthly since 1789: MaxRange2, created by one of the authors of this paper, Max Rånge. The purpose of this first overview, an initial analysis of the regime type dimensions and institutional sequences of this new data set, is to assess whether the evolution of political institutions is “path dependent”—that is, whether democratization can be inferred as primarily an outcome of previous institutional experience, and whether there are

“civilizations”—in term of majority religions— forging pathways for groups of nations. The aims are both empirical—to introduce the new MaxRange2 data set on political institutions since 1789—and theoretical—to take steps toward an understanding of the sequential aspects of political-institutional evolution.1 In addition, we introduce the sequence analysis developed for the study of life-history data on the individual level to the nation-level analysis of institutional sequences.

Method

We apply a sequence analysis technique developed for life-cycle study of individuals over the course of schooling, further education, work life, marriage, and so on. More specifically, we

3

apply some of the features of the toolbox TraMineR in R for analyzing and visualizing categorical state sequences (Gabadinho 2011). A similar technique for sequence analysis is also offered in Stata (Brzinsky-Fay et al. 2006). The primary objective of these techniques is to extract workable information from sequential data sets —i.e., to summarize, sort, group, and compare sequences. The resulting groups and sequences can then be used in classical inference of explanatory models, so that sequences and groups of sequences can be used as explanans and explanandum in causal modeling. A common approach in sequences analyses for categorizing patterns, also used in this paper, consists of computing pairwise distances by means of alignment algorithms, such as optimal matching (Abbott and Forrest 1986; Abbott and Tsay 2000). The resulting groups or clusters can then be related to hypothesized

covariates by means of logistic regressions or classification trees (Gabadinho 2011). More recently, Elzinga and Liefbroer (2007) and Widmer and Ritschards (2009) have suggested a complementary approach to focus on longitudinal diversity and complexity in the sequences. Complex techniques are the analysis of transversal characteristics of data (wave-like

dynamics), suggested by Billari (2001). Such wave-like evolution can be compared between groups and clusters, something which may give insights into the historical dynamics of various groups of institutions. This is particularly interesting for political scientists in analyzing longitudinal democratization data since we have several theories and previous results of waves and diffusion of democracy (Huntington 1991).

4

Though there are some shorter time-series data sets on political institutions, such as the Freedom House, the Economist Intelligence Unit (EUI), the Institutional and Elections Project (IAEP), and the Adam Przeworski Democracy and Dictatorship data sets (Przeworski 1991), there have only been three data sets that go as far back as the early 19th century: Polity IV (from 1800), the Boix, Miller, and Rosato Political Regimes data (BMR, from 1800) (Boix et al. 2012) , and the Vanhanen Polyarchy data set (from 1810) (Vanhanen 2003). The two last data sets are interesting but very limited in variable structure: both relate to Dahl’s

definition of democracy as based on contestation and participation (Dahl 1971). Vanhanen defines a democracy index by combining the share of party representatives not belonging to the largest party in the elected parliament and participation in the elections (Vanhanen 1997). In the BMR data set that runs to 2007, democracy versus non-democracy is given as a binary interpretation on the basis of the same distinction. This means that neither

Vanhanen’s Polyarchy nor the BMR give indications of political regime institutions in its details and variety, but rather provides us with an index of democracy. These two databases are also no longer updated.

Polity IV data, on the other hand, covers all nation states with a population of more than 500,000 inhabitants starting from 1800 (Jaggers and Gurr 1995; Gurr 1974; Marshall and Jaggers 2002, 2010; Eckstein and Gurr 1975). In this continuously updated data set, a complex structure of innovative measurements of institutions is measured. In fact, even experienced researchers argue that the Polity IV data structure is complicated and problematic (Hadenius and Teorell 2005). We argue that it would be much simpler and scientifically useful if traditional definitions are used. If needed, a complex structure can

5

later be invented on the basis of quite formal, well-known, and uncontested definitions and operationalizations.

Not only is Polity IV obsolete in concepts and measurements, but it is also exhausted empirically. Since it has been used in most studies of democratization studies, there is very little left to squeeze out of it today. In our recent efforts, Lindenfors, Jansson, and Sandberg used Polity IV data in the analysis of transitions times between autocracy and democracy (Lindenfors et al. 2011). Jansson, Lindenfors, and Sandberg found that transition to democracy duration (up to 12 years) increased the likelihood of survival of the resulting democratic regime (Jansson et al. 2013). Sandberg and Lundberg (2012) discovered certain institutional path-dependencies using Polity IV data in a principal component analysis. But during our analyses, we have increasingly realized that new, more detailed and informative data are needed to advance the studies of institutional evolution on a world scale.

Our research here has the competitive empirical advantage of sole access to an extremely promising new data set on political institutions in all countries of the world since at least 1789, on a monthly basis, and since 1600 on a yearly one. This data set, MaxRange (and its new version MaxRange2), created by Max Rånge, consists of variables of political regimes coded on a 1-1000 categorical (and not necessarily linear) scale. Codes for binary variables on all the political institutions underlying the categorization of the variable political regime s have partly been created in their initial form (with Mikael Sandberg). The yearly data set has 54,127 country-year cases so far, and more have been added for the years back to 1600. The monthly data set, so far stretching back to 1789, has 12 times more cases (649,524), which make it by far the biggest and most comprehensive political regime data set in the world.

6

MaxRange can be merged with other data sets, such as Polity IV (1800- ). Since the previous version of MaxRange, limited by its 100-degree scale, has now been updated into a 1000-degree scale of political systems, we refer to this later version as MaxRange2.

MaxRange2 thus has several advantages compared to other available data:

1. A monthly time-series from 1789 for a longer time than any other data set, making in particular the study of transitions more detailed and reliable, since they normally occur on more detailed time-scales than years (however, this is not the subject here); 2. Yearly data available from 1600, i.e. at least 200 years longer than any other

comparable time series data set;

3. A formal and “normal” classification of democratic and non-democratic regimes in categories on the basis of non-abstract definitions like: “monarchy,”

“parliamentarism,” “Head of State elected,” etc., lacking in previous time series data. 4. The 1000-degree scale is more detailed than any other institutional data set. The

scale defines both the classifications described above and is used for dummy variable creation, so that singular institutions are coded in a way that creates up to 1000 different systems’ unique combination of these classifications.

In sum, the data set is not only a huge accomplishment in itself; it offers the opportunities to resolve fundamental issues of institutional evolution and in that sense to revolutionize our institutional analysis.

In the coding of political regimes, political systems , and institutions, MaxRange focuses on: (1) the institutional structure, (2) the strength of the executive, (3) normal vs. interim status

7

of the regime (particularly useful in transition studies), (4) the Head of State position, (5) the concentration of powers to the executive, (6) the Head of Government position, a number of institutional dummies indicating presence or absence of a number of formal institutions, and summarizing all previous dimensions, finally (7) a simplified executive strength variable.

By the variable (1) institutional structure, various forms of executive powers and systems are defined as formal institutions or complexes of institutions, such as parliamentarism,

presidentialism, semi-presidentialism, interim, military, colonial structure (see appendix and our descriptive article, forthcoming). By the variable (2) executive strength, MaxRange provides the degree to which political system executives have constitutional powers: dominating, absolute, or weak executive powers. In the variable (3) normal vs. interim systems, regimes are evaluated in the relation to their degree of “normality” in contrast to being in an interim, therefore unstable condition. In cases where institutional constructs are of interim type, some important classifications are made, such as military junta or martial law institutions. These categorical values make possible more detailed transition studies since they are unique monthly data.

The (4) Head of State variable indicates whether the nation-state is a republic, a monarchy, or has any unified head of state at all. In the (5) executive concentration variable, we find values of the executive powers in terms of whether they are concentrated, separated, or undefined in this respect. Similarly, in the (6) Head of Government variable there are values indicating who is fulfilling that function; a president, prime minister, monarch, or any other defined head of the executive. In the last variable (7) simplified strength, MaxRange provides a simplified summary of the degree to which executive powers are either decentralized,

8

centralized, or balanced as an account of the overall character of the state (s ee the code book in appendix).

The resulting political institutional scale positions each political system each month since 1789, or year since 1600, on a 1-1000 scale, where the degrees from 760-1000 are defined democratic. In this paper however, since transitions are not considered in monthly detail, only yearly data from 1789 are used. First, we may compare MaxRange2 data with Polity IV in terms of number of democracies.

Figure 1 around here.

As is seen in the figure, MaxRange2 differs from Polity IV data with respect to the measurement of democracy mainly in that it is a longer data set (from 1789 rather than 1800 in this case), and that more nations are included since Polity IV only includes nations with populations greater than 500,000. MaxRange also includes several other smaller political units listed in the appendix, namely those that proclaimed themselves independent. However, in addition to that, MaxRange2 is more inclusive than is Polity IV in the

measurement of democracy (value 6 or above on the institutionalized democracy variable, the value indicated as threshold for democracy on the Polity home page).

In this initial analysis of regime type data, values of the MaxRange2 institutional variable 1-1000 are first grouped into regime types in order to present data and major patterns in a

9

more comprehensible introduction to the data set. In the creation of the regime type simplified data set, the following operationalization was made (see table 1).

Table 1 around here.

Table 1 describes operational definitions of regime types in the MaxRange2 data set’s regime and institutional variable with a value scale 1-1000. Absolutism is defined as having MaxRange2 values from 5-75 (for further description, see the codebook in the appendix). Examples are Albania 1789 to 1911 and Brunei 1986 to 2013. Anarchy is defined as the second regime type, with values from 80-145 and 170-195 on the MaxRange2 scale. Examples are Bhutan 1789 to 1884 and Syria 2012-2013. A third regime type,

Totalitarianism, is defined by several values on the MaxRange2 scale given in table 1. Examples are Afghanistan 1789-1917 and Tajikistan 1992-2013. The fourth regime type, Military, is defined by values from 290-295, 340-345, and 470. Examples are Haiti 1804-1805 and Egypt 2013. Like totalitarianism, the Authoritarian Regime Type is defined at a larger number of MaxRange2 levels. Examples are France in 1824-1828 and Turkmenistan in 2008-2013. Finally, democracy is defined as 790-805 and 815-845. Examples are Ireland 1789-1831 and 1921-2013; and Switzerland 1803-2013. Added to that is an “Other” category. The regime type definitions are preliminary and so far primarily made for purposes of initial exploration and descriptive visualization of the rich data material and its analysis by means of TraMineR.

10

Survey of the Field

Institutional change and political trajectories have been studied in several social science disciplines, and in fact before these disciplines emerged, in the classic texts by Aristotle, de Tocqueville, Marx, and other social philosophers. Interestingly, in Politics, Aristotle had already presented a model over how certain types of regimes could change into others, such as aristocracies into oligarchies, and constitutional regimes into democracies. Modern

sociological contributions to historical comparative analysis include Barrington Moore’s study of the social origins of dictatorship and democracy (Moore 1966), and Theda Skocpol’s and Charles Tilly’s contributions to the historical explanations of revolutions and democracy. Moore saw the roots of totalitarianism and democracy in the social organization of the agrarian systems of nations and the way they industrialized. While Skocpol included international competitive pressures in her explanation of revolutions (Skocpol 1979), Tilly placed the most focus on indigenous factors such as regime change toward democracy in interaction with popular contention (Tilly 1992, 2003).

Among political scientists, we find historically comparative analyses in Lipset and Rokkan (Lipset and Rokkan 1967), who proposed roots and “junctures” of our political and party systems in the Reformation, the “democratic revolutions,” and the industrial revolution. In that sense, they were perhaps the pioneering political scientists of institutional path dependency, even before the term was coined by economists like Arthur and David (Arthur 1994; David 1985). In classics by Schumpeter (1942), Dahl (1971), Linz and Stepan (1996), and others (e.g., Vanhanen 1997), we do find narratives of institutional dynamics. Non-democratic institutions are normally defined with reference to Huntington (1991), Linz and

11

Stepan (1996), Diamond (2002), O’Donell and Schmitter (1986), Epstein et al. (2006), and others (e.g., Hadenius and Teorell 2007). In modern political science, Collier and Collier (2002), Pierson (2004), and Putnam (1992) have suggested institutional path dependencies on the basis of theory and case studies (rather than time-series data).

In this paper, we instead consider the determinants of democracy and other regime types in the perspective of institutional evolution. We therefore ask why institutions —and their resulting political systems—change by probing sequence interpretations of path dependence in our new data. Our reasons are found in the fact that we, in our previous modeling and studies of democratization internationally based on the heretofore dominant Polity IV data, have noticed the compatibility of the path dependency concept with evolutionary and political culture studies (Åberg and Sandberg 2002; Sandberg 2011; Jansson et al. 2013; Sandberg and Lundberg 2012; Sandberg 2003/04; Lindenfors et al. 2011; Sandberg 2000).

The social vs. natural science divide appears in the analysis of institutions. Natural science perspectives help us understand why and how institutions emerge (Young 2001; Bowles 2004). North’s concept of institutions as “rules of the game” or, more specifically, the

“humanly devised constraints that structure political, economic and social interaction”(North 1990) has been extremely influential but offers a limited explanation of why, how, and in what order they were humanly devised. Ostrom adopted an evolutionary concept of institutions (Ostrom 1990) by means of game theory, thereby focusing on institutions as equilibria, which is not easily translated into statistical modeling, whatever the qualities of her work in other respects. In fact, political science has a few but important contributions to non-evolutionary, institutional theory (for these titles, see March and Olsen 1989, 1996;

12

Pierson 2004; Peters 2012), while also being greatly influenced by institutional economics, some of which are in fact evolutionary (Veblen 1912; North 1990; Young 2001; Bowles 2004; Hodgson 2000). Greif (2006), Aoki (2001), and Acemoglu and Robinson (2009) have made important recent contributions to institutional analysis. Again, this is made without longitudinal and quantitative rigor specifically on the emergence and diffusion of institutional innovation.

As concept arising from evolutionary studies of innovation, “path dependence” as a social phenomenon is associated with evolutionary economists, perhaps primarily David and Arthur (David 1985; Arthur 1994) 2. In Pierson’s Politics in Time (2004), path dependence is defined as “social processes that exhibit positive feedback and thus generate branching patterns of historical development” (p. 21). Here, we do not investigate whether there is feedback, only if there are actual patterns of historical development among political institutions that support the thesis that institutional history matters for current institutions and that there might be branching processes or multiple pathways of institutional evolution. As Lipset and Rokkan considered path dependence—without naming it so—in political systems (Lipset and Rokkan 1967), we first look at regime type level path dependences, and whether pathways of regimes can be considered. Is the later evolution of democracy, for instance, only the case in countries that historically have sequences of specific other non-democratic regimes? Are there differences among nations with different religious majorities, as suggested in Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations hypothesis (Huntington 1993) and in some later scholarship (Potrafke 2012, 2013; Charron 2010)? Or do we instead see a diffusion pattern, so that democracy spreads in all types of regimes (Coppedge 2001; Gleditsch and Ward 2006; O'Loughlin et al. 1998; Sandberg 2011; Starr 1991; Wejnert 2005; Elkink 2011),

13

irrespective of the historical and original regime types and of the majority religion of the nations?

Regime Type Sequences

We may now overview the historical evolution of political institutions and regime types among nations since 1789. Using the sequence approach on MaxRange2

political-institutional data, a sorted sequence distribution of regime type data is first presented in full in figure 2.

Figure 2 around here

First, in the upper diagram of this figure, we see the stacked order of sequences in world political regime types 1789-2013. In this first, grey-scale figure (with Absolutism in dark and democracy in light grey), all yearly institutional states are described in full, i.e., without a regime type grouping of variable values. In the next figure, the same data are grouped into regime types from absolutism to democracy, and coded by color. In the bottom layer of this colored diagram, we have diminishing portion of absolutism, with a similarly diminishing layer of despotism on top. The thin layer of colonial states increases in number until the 1960s, where it disappears. The totalitarian layer, prevalent since 1789, continues to grow until 1989, where it decreases dramatically, though without disappearing. Authoritarianism also grows in number until the mid 1960s, where it starts to vanish. In the aftermath of the 1989 implosion of totalitarianism, it again grows in number, however. Democracy, however,

14

steadily grows in number of nations after its low tide around 1840, and in particular from the early 1990s.

Looking at the lower diagram, we instead see backwards from various regime types , which previous institutional states and sequences nations have historically had. In the upper part of that lower diagram, we see the democratic cascade, beginning in the early 1800s but in particularly diffusing from the 1860s and after the world wars. The conclusion we can draw, considering the multitude of institutional states and sequences before democratization, is that there is no obvious particular regime type predecessor to democracy.

Below the democracy diffusion in the figure, we see the (green) authoritarian group of countries and from which regime types it evolved. Again we cannot say directly what type of regimes nations have before they become authoritarian. We do see a mix of absolutist, anarchist, despotic, colonial, and totalitarian precursors to authoritarianism. The same is more or less true of still totalitarian nations; we can note a number of different precursors to it, while of course democracy seems rare. But we need more detailed scrutiny of the degree to which background factors may influence sequences and democracy. In figure 3 below, the last diagram of figure 2 is divided into blocks of sequences in accordance with their regime type status the first year (1789). Since there are 9 regime types, we have 9 blocks of sequences sorted in the order of the regime types in 2013.

15

In our view, the figure 3 falsifies the institutional path dependence hypothesis, if

investigated at crude regime type level. As is seen in the figure, all nations, whatever regime type they had in 1789, exhibit some and a growing number of democracies over time to the present. Diffusion of democracy occurs among all previously non-democratic regime types. In the first diagram 1 in figure 3, the 31 nations with absolutism in 1789 are shown to overcome their absolutism, in some layers becoming democratic already in the early 1900s, transforming into totalitarian and authoritarian, but after 1989 increasingly being

democracies. Among the 2 anarchies in 1789, we see later colonial states, with patchy transition periods of authoritarianism, totalitarianism, and democracy. Among the 90 nations that were despotic in 1789, almost all are now democracies. The transition started already in the early 1800s with colonial and authoritarian transitions. Increasingly, in particular after World War I, we see both democratic examples as well as totalitarian, but again, after 1989, approximately half of them become democratic. All 6 nations that were colonies in 1789 are democracies now. Of the three totalitarian nations in 1789, two are now democratic, while one is still totalitarian. Among the three authoritarian nations in 1789, all are democracies today. Among the six democracies in 1789, only four are democracies today, however. Even in the other regime type category, we see democracy diffusing in the post-war era. On the whole, the pattern is clear: democracy diffuses on regime type level in all nations irrespectively of their prior regimes.

Modal states for all sequences (Appendix 2) verifies the transitions to democracy in all types of regimes since 1789. All regime types except anarchy exhibit democracy in 2013.

16 Figure 4 around here.

Finally, we can calculate the Shannon entropy indicator, called the entropy index (Billari 2001). It equals 0 when all cases are in the same state (it is thus easy to predict in which state an individual nation is located). It is maximum when the cases are equally distributed between the states, in this case the regime type states 1-9 (it is thus hard to predict in which state an individual nation is located). Given the entropy index evolution in the MaxRange2 data set (figure 4), we see that predictability increases in an accelerating pace in the post-Second World War era for all the regime type groups as of 1789 except absolutism and the “other” category, in particular after 1989, as more democracy dominates among world political regime types. Only among the nations that had absolutism or an “other” regime type in 1789 can we see an increase in unpredictability. Absolutism seems thus to be an unpredictable state that can lead to any other type of regime.

Religion and Regime Sequences

Thus far, we noted that democracy could diffuse in more or less all previous regimes. But our second question is whether diffusion of democracy occurs as easy in all types of nations. Are there differences among nations with different religious majorities, as could be inferred

17

from Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations hypothesis (Huntington 1993) and in accordance with some later empirical results (Potrafke 2012, 2013; Charron 2010)?

We have very few available background variables for nation states prior to 1789, but one we do have is the kind of religion that dominated in nations. In this case, we use Laporta et. al data (1999), where the majority religion is given for 1980.3 In classic quantitative studies of democracy, Lipset correlated wealth with democracy. Maddison has managed to make an estimation of the wealth in terms of GDP per capita for a large number of nations in 1820 (2007).

Investigating the patterns of religious nation group sequences of institutions, we will consider four groups: Catholic, Muslim, Protestant, and Other denomination majority

nations, in accordance with available data. We therefore first study Catholic political systems in relation the rest (figure 5).

Figure 5 around here

The Catholic group of 63 countries, as seen in figure 5, includes several of the oldest

democracies, and also many of the second and third wave democracies. The backgrounds for these democracies are mainly authoritarian but also despotic. Looking at the nations 28-63 in the figure, we see that authoritarianism is likely before early democratization, while

18

despotism is more common among the late democratizers. Some of the despotic nations have a period of being a colony before turning democratic.

In the Muslim group of 45 countries, as seen in diagram 2 in figure 5, we have only a few late democratizers today (nations 35-41) and only patches of democracies of the first, second, and third wave. Particularly few democracies seem to emerge from absolutism, but some periods of democracy arise out of colonies and authoritarian rule. The post-1989

authoritarian and totalitarian Muslim nations form two distinct cascades, visible around nations 16 and 32.

The Protestant nations are difficult to distinguish from the Catholic, as is seen in the last diagram in figure 5. The same typical pattern described for Catholic countries holds also for the Protestant ones. Both democratize increasingly after the world wars, both have the (green) authoritarian predecessor states, both only to a minor extent (5-10 nations or so) are authoritarian today, and are otherwise democratic.

In Appendix 3, we can use modal values to distinguish more clearly what is typical to each group. The Catholic nations typically pass through despotism and a couple of decades of authoritarianism in the late 19th century and increasingly grow democratic after World War II (with a reversal in the early 1970s). Muslim nations rather pass throug h absolutism and despotism, before they, after World War II, shift to a number of non-democratic regime types, including totalitarianism, authoritarianism, and even despotism. Protestant nations typically suffer from despotism until the end of World War II, when the most common state is increasingly democracy. We can indeed find typical traits of civilizations, or at least

19

considerable differences among nations with different religious-majority groups, even if we from the institutional data used so far cannot in detail give an indication of exactly why or by means of exactly what institutions.

Differences between the three religious-majority group regimes are also obvious when presenting the mean time spent from 1789-2013 in various regime types in each group. In the appendix, we see that among Catholic-majority countries, time spent as democracy is less than both in despotism and authoritarianism. Among Muslim-majority systems, time spent in despotism, absolutism, totalitarianism, and authoritarianism exceeds the time spent in democracy (and as mentioned, the democracy value includes those countries with above 790 on the MaxRange2 scale, i.e., both limited and qualified democracies). Among the Protestant-majority nations, only mean time spent under despotism is longer than the time spent under democracy.

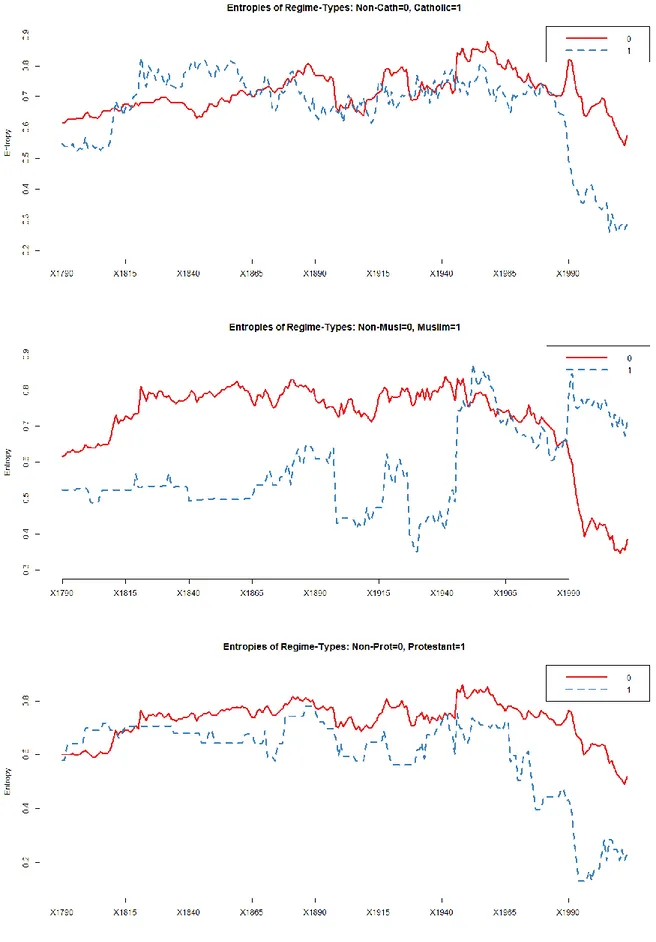

Figure 6 around here.

Finally, entropy of the three groups of nations reveals interesting variety. In the Catholic-majority nations, entropy decreases drastically, indicating an accelerating predictability—in this case, further democratization. The same is true for the smaller group of Protestant-majority nations. In Muslim-Protestant-majority nations, however, we notice an ominous increase in entropy, making them less predictable in their future evolution.

20

Finally, can the religious-majority factor contribute in statistically significant ways to the explanation of further institutional evolution? TraMineR offers tools for analyzing

discrepancies of sequences. The logic is that the sum of squares can be expressed in terms of distances between pairs, used in the optimal matching process, which makes it possible to estimate dispersion, which is, in turn, the basis for analysis of variance (Studer et al. 2011).4

Table 2 around here

Figure 7 around here

In the first of the four sliding R squared analyses in figure 7, we see the contribution of being a Catholic-majority nation on the variance in discrepancies in regime types. The overall pseudo R squared is significant but very low. However, the influence of religion on

discrepancy varies greatly over time. Pseudo R squared stretches from around 0.005 three times from the 1950s to the 1970s, while it peaks twice with 0.05 in the 1990s. Previously in history, Catholic majority reached levels around the same value in early 1800s and around 1890.

Looking at the sliding R squared for Muslim influence on discrepancy, we see a drastic increase since the early 1970s, i.e., in the third wave, from around 0.025 to 0.15. The overall pseudo R squared is only 0.04. Previously in history, there is one peak between the World Wars of 0.05, i.e., at the same level as for the Catholic-majority nations at least three times in history. So the Muslim effect is a third wave phenomenon.

21

The Protestant-majority factor increased its importance for the R squared of discrepancy up to more than 0.05 in the late 1970s to the early 1980s, with some additional minor peaks after that. Since Protestant countries are relatively few, it means that a relatively small number of Catholic countries democratized around that time. But apart from that peak, there are no important periods in history for Protestant-majority reduction in shared discrepancy variance.

The other denomination factor has an extremely weak pseudo R squared and peaks of 0.025 or smaller.

Finally, we generalize the previous approach for multiple covariates. We measure the additional contribution of each covariate when we account for all other covariates. Significance is assessed again through permutation tests. Results are presented in table 2.

Table 3 around here.

The multiple factor analysis reveals the extremely limited contributions of religious majority to the explanation of regime type sequence discrepancies. Religious majorities contribute with few percentages, while the factor GDP per capita (as measured by Maddison for 1820), explains 0.24 of the discrepancy in regime type states. Religion provides extremely little explanatory power by itself, as compared by the proxy for early levels of wealth in the time series under investigation which explains over ten times more. Economic wealth seems a

22

much more important factor for long term political-institutional pathways than do the religious majorities of nations. The somewhat paradoxical conclusion means that sequences of institutions do not matter for later democratization, but majority religion does, namely as an obstacle if Muslim. Why this is the case with only the Muslim-majority nations, we do not yet know in detail. Simultaneously, using the religious majorities as explanations for overall institutional discrepancy helps us only to a limited extent. Rather, it is wealth in terms of GDP per capita that can explain at least a quarter of the discrepancy found in institutions using MaxRange2 data.

Discussion

Aristotle pioneered the sequence analysis of political regime types. He noted (in Politics, Book four, Part II), that kingly rule, aristocracy, and constitutional government, the “true forms,” may lead to three corresponding “perversions”: tyranny, oligarchy, and democracy. Later in Book four, Part VI, he also considered several forms of democracy on the basis of their origin. Interestingly, no political scientist since seems to have made an empirically based analysis of which types of political system we actually have had—and in what order or sequence—in the world, and how these sequences may be explained. One reason is of course a lack of data. The data set dominant today, Polity IV, has yearly institutional variables since 1800, but they are conceptualized in a way that makes them more or less impossible to use for a sequence analysis (Lundberg and Sandberg 2012).

23

Thus far, we have not found any previous attempt to follow up this study of Aristotelian themes. As we know, MaxRange2 data is also the largest data set in the world on political systems, and we are confident in presenting nothing less than the first ever comprehensive sequence analysis of all political institutions and political regimes in the world since 1789. As the data structure is new—a huge nominal to ordinal scale time series for over 200 nations over 224 years—new techniques for analysis are also required. In our project and this paper, relying on the MaxRange2 institutional data set used, stretching as far back as 1789 for all nations in the world, we can investigate sequences or pathways in world system states over the previous two centuries with respect to the major political institutions.

MaxRange2 data, as mentioned, uses a 1000-degree scale of political systems or regimes, of which approximately 175 are actually used in the empirical material of all nations in the world since 1789. Sequences of 175 states are not used in this analysis, since that would produce a hopelessly complex but fascinating fabric of institutional states (see the upper diagram in figure 2). Instead, groups of institutional states have been created (defined in appendix 3 and described in the middle and lower diagrams in figure 2), namely a categorical scale of 9 different types: (1). Absolutism, (2) Anarchy, (3) Despotism, (4) Colony, (5)

Totalitarianism, (6) Military, (7) Authoritarianism, (8) Democracy, and finally (9) Other. Using this simplification, we may first consider regime type path dependencies, in particular whether democracy is more or less connected with previous experiences of certain other regime types. Obviously, later analyses may be elaborated with more or less detailed categorizations.

24

We first consider the sequences and notice that democracy may diffuse from all types of previous regimes. We then also notice that Muslim-majority nations, for reasons unknown in detail, are typically reluctantly immune to democracy. For this reason, one might be

surprised that the discrepancy of institutional setups over time in sequences to a large extent cannot be explained by religion in nations. Instead, as a general rule, an economic factor such as wealth among nations plays a much more important role in affecting nations in their regime type variety. But we must distinguish the role of majority religion in

understanding receptivity for democracy diffusion separately from the statistical explanation of general discrepancy among regime types. Religion is important for the former, but not for the latter, for which instead wealth is a much more critical factor. However, the specific details of these causal mechanisms are not yet known. We wish to use further specifications at sub-regime institutional level in our future analyses of MaxRange2 data with the purpose of reaching a richer explanation of these mechanisms.

25

References

Abbott, A, and A Tsay. 2000. "Sequence Analysis and Optimal Matching Methods in Sociology, Review and Prospects." Sociological Methods and Research 29 (1):3-33. Abbott, Andrew, and John Forrest. 1986. "Optimal Matching Methods for Historical

Sequences." Journal of Interdisciplinary History 16 (3):471-49.

Acemogli, Daron, and James R. Robinson. 2009. Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Aoki, Masahito. 2001. Toward a Comparative Institutional Analysis. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Aristotle. 1976. The politics of Aristotle. Books I-V : a revised text. New York: Arno Press. Arthur, Brian. 1994. Increasing Returns and Path Dependence in the Economy. Ann Arbor:

University of Michigan Press.

Billari, FC. 2001. "The analysis of early life courses: complex descriptions of the transition to adulthood." Journal of Population Research 18 (2):119-42.

Boix, C, MK Miller, and S Rosato. 2012. "A Complete Dataset of Political Regimes, 1800‐ 2007." Comparative Political Studies 20 (10):1-32.

Bowles, Samuel. 2004. Microeconomics : behavior, institutions, and evolution. Princeton, N.J. ; Woodstock: Princeton University Press.

Brzinsky-Fay , Christian, Ulrich Kohler , and Magdalena Luniak. 2006. "Sequence analysis with Stata." Stata Journal 6 (4):435–60.

26

Charron, Nicholas. 2010. "Déjà Vu All Over Again: A post-Cold War empirical analysis of Samuel Huntington’s ‘Clash of Civilizations’ Theory." Cooperation and Conflict 45 (1):107-27.

Collier, Ruth Berins, and David Collier. 2002. Shaping the Political Arena. Critical Junctures, the Labor Movement, and Regime Dynamics in Latin America. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

Coppedge, Daniel M. Brinks and Michael. 2001. "Patterns of Diffusion in the Third Wave of Democracy." In Annual Meeting of American Political Science Association. San Fransisco, CA.

Dahl, Robert Alan. 1971. Polyarchy; participation and opposition. New Haven,: Yale University Press.

David, Paul. 1985. "Clio and the Economics of QWERTY." The American Economic Review 75 (2):332-7.

Diamond, Larry K. 2002. "Thinking About Hybrid Regimes." Journal of Democracy 13 (2):21-35.

Eckstein, Harry, and Ted Robert Gurr. 1975. Patterns of authority : a structural basis for political inquiry. New York: Wiley.

Elkink, Johan A. 2011. "The International Diffusion of Democracy." Comparative Political Studies 44 (12):1651-74.

Elzinga, Cees H., and Aart C. Liefbroer. 2007. "De-standardization of Family-Life Trajectories of Young Adults: A Cross-National Comparison Using Sequence Analysis." European Journal of Population 23:225-50.

Epstein, David L., Robert Bates, Jack Goldstone, Ida Kristensen, and Sharyn O'Halloran. 2006. "Democratic Transitions." American Journal of Political Science 50 (3):551-69.

27

Gabadinho, A, Ritschard, S, Müller, N S, Studer, M. 2011. "Analyzing and Visualizing State Sequences in R with TraMineR." Journal of Statistical Software 40 (4):1-37. Gleditsch, Kristian Skrede, and Michael D. Ward. 2006. "Diffusion and the International

Context of Democratization." International Organization 60 (4):911-33.

Greif, Avner. 2006. Institutions and the Path to the Modern Economy: Lessons from Medieval Trade. Boston: Cambridge University Press.

Gurr, Ted Robert. 1974. "Persistence and Change in Political Systems, 1800-1971." The American Political Science Review 68 (4):1482-504.

Hadenius, Axel, and Jan Teorell. 2005. "Assessing Alternative Indices of Democracy." In International Political Science Association IPSA. Concepts & Methods Working Papers 6.

———. 2007. "Pathways from Authoritarianism." Journal of Democracy 18 (1):143-57. Hodgson, Geoffrey M. 2000. Evolution and institutions : on evolutionary economics and the

evolution of economics. Geoffrey M. Hodgson. ed. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. Huntington, Samuel P. 1991. The third wave : democratization in the late twentieth century.

Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

———. 1993. "The clash of civilizations?" Foreign Affairs 72 (3):22.

Jaggers, Keith, and Ted Robert Gurr. 1995. "Tracking Democracy's Third Wave with the Polity III Data." Journal of Peace Research 32 (4):469-82.

Jansson, Fredrik, Lindenfors Patrik, and Sandberg Mikael. 2013. "Democratic revolutions as institutional innovation diffusion : rapid adoption and survival of democracy." Technological forecasting & social change 80 (8):1546-56.

La Porta, R, F Lopez-de-Silanes, A Shleifer, and R Vishny. 1999. "The quality of government." Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 15 (1):222-79.

28

Lindenfors, Patrik, Jansson Jansson, and Mikael Sandberg. 2011. "The cultural evolution of democracy: saltational changes in a political regime landscape. ." PLoS ONE 6 (11):e28270. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028270.

Linz, Juan J., and Alfred C. Stepan. 1996. Problems of democratic transition and consolidation : southern Europe, South America, and post-communist Europe. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press.

Lipset, Seymor M, and Stein Rokkan. 1967. Party systems and voter alignments: cross-national perspectives. New York: Free Press.

Maddison, Angus. 2007. Contours of the world economy, 1-2030 AD : essays in macro-economic history. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press.

March, James G., and Johan P. Olsen. 1989. Rediscovering Institutions: The Organizational Basis of Politics. New York: The Free Press.

———. 1996. "Institutional Perspectives on Political Institutions." Governance 9 (3):247–64. Marshall, Monty G., and Keith Jaggers. 2002. "Political Regime Characteristics and

Transitions, 1800-2002: Dataset Users' Manual." Polity IV Project, University of Maryland, College Park, MD.

———. 2010. "Polity IV Project: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions 1800–2008." University of Maryland.

Moore, Barrington. 1966. Social origins of dictatorship and democracy; lord and peasant in the making of the modern world. Boston,: Beacon Press.

North, Douglass Cecil. 1990. Institutions, institutional change, and economic performance. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press.

29

O'Donnell, Guillermo A., and Philippe C. Schmitter. 1986. Transitions from authoritarian rule : tentative conclusions about uncertain democracies. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

O'Loughlin, John, Michael D. Ward, Corey L. Lofdahl, Jordin S. Cohen, David S. Brown, David Reilly, Kristian S. Gleditsch, and Michael Shin. 1998. "The Diffusion of Democracy, 1946-1994." Annals of the Association of American Geographers 88 (4):545-74. Ostrom, Ellinor. 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective

Action. Boston: Cambridge University Press.

Peters, B. Guy. 2012. Institutional theory in political science: The 'new institutionalism'. New York: Continuum.

Pierson, Paul. 2004. Politics in time : history, institutions, and social analysis. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Potrafke, Niklas. 2012. "Islam and democracy." Public Choice 151 (1-2):185-92.

———. 2013. "Democracy and countries with Muslim majorities: a reply and update." Public Choice 154 (3-4):323-32.

Przeworski, Adam. 1991. Democracy and the market : political and economic reforms in Eastern Europe and Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Putnam, Robert D. 1992. Making democracy work : civic traditions in modern Italy.

Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Sandberg, Mikael. 2000. "Politiska och ekonomiska ”uttrycksarters” uppkomst genom institutionell selektion." Statsvetenskaplig tidskrift 103 (2):116-47.

———. 2003/04. "Hur växer demokratin fram? Dynamisk (evolutionär) Komparation och några metodtest på europeiska regimdata." Statsvetenskaplig tidskrift 106 (4):2 6 5 - 3 03.

30

———. 2011. "Soft Power, World System Dynamics, and Democratization: A Bass Model of Democracy Diffusion 1800-2000." Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation 14 (1):4.

Sandberg, Mikael, and Per Lundberg. 2012. "Political Institutions and Their Historical Dynamics." PLoS ONE 7 (10):: e45838. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045838.

Schumpeter, Joseph Alois. 1942. Capitalism, socialism, and democracy. New York, London,: Harper & Brothers.

Skocpol, Theda. 1979. States and social revolutions : a comparative analysis of France, Russia, and China. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Starr, Harvey. 1991. "Democratic Dominoes: Diffusion Approaches to the Spread of Democracy in the International System." The Journal of Conflict Resolution 35 (2):356-81.

Studer, Matthias, Gilbert Ritschard, Alexis Gabadinho, and Nicolas S. Müller. 2011. "Discrepancy Analysis of State Sequences." Sociological Methods and Research 40 (3):471-510.

Tilly, Charles. 1992. Coercion, capital, and European states, AD 990-1992. Rev. pbk. ed. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

———. 2003. The politics of collective violence. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Vanhanen, Tatu. 1997. Prospects of democracy : a study of 172 countries. New York: Routledge.

———. 2003. Democratization : a comparative analysis of 170 countries. London ; New York: Routledge.

31

Veblen, Thorstein. 1912. The theory of the leisure class; an economic study of institutions. [New ed. New York,: The Macmillan Company; etc.

Wejnert, Barbara. 2005. "Diffusion, Development, and Democracy, 1800-1999." American Sociological Review 70 (1):53-81.

Widmer, Eric D, and Gilbert Ritschards. 2009. "The de-standardization of the life course: Are men and women equal?" Advances in Life Course Research 14 (1-2):28-39.

Young, H. Peyton. 2001. Individual Strategy and Social Structure: An Evolutionary Theory of Institutions. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Åberg, Martin, and Mikael Sandberg. 2002. Social capital and democratisation : roots of trust in post-Communist Poland and Ukraine. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Data

MaxRange

32

33

Figure 2. The Historical Landscapes of Political Institutions, MaxRange2, 1789-2013

Note: MaxRange2 Institutional (in grey, total institutional scale 1-1000) and Regime Type Sequence Indexes: in color, by 1-9 Regime Types and by End State Order).

34

35 Figure 4. Entropies for Regime Types as of 1789

36

Figure 5. “Civilizations” and Regime Type Sequences

Note: Catholic, Muslim, Protestant, and Other Denomination Majority Nations (Right Column=1) vs Non-Catholic, Non-Muslim, Non-Protestant, and Non-Other Denominations (Left Column=0)

37

Figure 6. Entropy in Catholic, Muslim, and Protestant Majority Systems vs. Catholic, Non-Muslim, and Non-Protestant

Note: Catholic, Muslim, and Protestant Majority Systems (blue dashed=1) vs. Catholic, Non-Muslim, and Non-Protestant (red=0)

38

Figure 7. Sliding Pseudo R Squared influence of Catholic (purple), Muslim (dark red), and Protestant Majority (green) in a Nation on Regime Type Discrepancy, 1789-2013

39 Table 1. MaxRange2 and Regime Types

MaxRange2 values Regime

Types

Examples of Country-Year Cases

5 thru 75 Absolutism Albania 1789-1911,

Brunei 1986-2013

150 thru 155 Anarchy Bhutan 1789-1884,

Syria 2012-1013 80 thru 145, 170 thru 195 Despotism Algeria 1789-1947,

Uzbekistan 2004-2013

350 thru 355, 230 thru 235=4 Colonial Barbados 1789-1961, Zambia 1924-1950 250, 360 thru 365, 320 thru 335, 260 thru 265, 240 thru

245, 200 thru 225, 390 thru 405, 300 thru 305, 270 thru 285, 160 thru 165

Totalitarian Afghanistan 1789-1917, Tajikistan 1992-2013 290 thru 295, 340 thru 345, 470 Military Haiti 1804-1805,

Egypt 2013 310 thru 315, 370 thru 375, 380 thru 385, 410 thru 415, 420

thru 425, 430 thru 435, 440 thru 445, 455, 460 thru 465, 480 thru 485, 490 thru 495, 500 thru 505, 510 thru 525, 530 thru 565, 570 thru 575, 590 thru 605, 620 thru 645, 660 thru 715, 740 thru 755, 780 thru 785

Authoritarian France 1824-1828, Turkmenistan 2008-2013

790 thru 805, 815 thru 845, 870 thru 895, 905 thru 1000 Democracy Ireland 1789-1831, 1921-2013;

Switzerland 1803-2013

Else Other

40

Table 2. ANOVA Test Values of Religious Majority on Regime Type Discrepancy Catholic Muslim Protestant Other

Denomination Pseudo R2 0.029** 0,039** 0.015* 0.032*

Note: ** = sign. at 0.01 level, *=sig. At 0.05 level. For interpretation of pseudo R Squared, see Studer et al. (2011).

41

Table 3. Multi-Factor Discrepancy Analysis of GDP per capita, Catholic, Muslim, Protestant and Other Denomination Majority contributions to explained discrepancy in Regime Types.

Variable Pseudo F Pseudo R2 P value GDP per capital (1820) 1.1611457 0.235492471 0.016** Catholic majority 0.6087257 0.003011120 0.692 Muslim majority 3.3356224 0.016499976 0.011** Protestant majority 1.6936994 0.008378047 0.133 Other denomination 0.5554048 0.002747363 0.751 Total 1.5709051 0.347049318 0.001**

42

Appendix 1. Mean Time Spent in Regime Types: Catholic, Muslim, and Protestant Majority Systems (right column) vs. the Non-Catholic, Non-Muslim, and Non-Protestant Majority Systems (left column)

43

44

Appendix 3. Modal State Sequences of Catholic, Muslim, and Protestant Nations (Right Column=1) vs. Non-Catholic, Non-Muslim, and Non-Protestant Nations (Left Column=0), 1789-2013

0 S ta te f re q . (n = 1 3 4 )

Modal state sequence (0 occurrences, freq=0%)

X1790 X1820 X1850 X1880 X1910 X1940 X1970 X2000 0 0.25 .5 0.75 1 1 S ta te f re q . (n = 4 5 )

Modal state sequence (0 occurrences, freq=0%)

X1790 X1820 X1850 X1880 X1910 X1940 X1970 X2000 0 0.25 .5 0.75 1 Absolutism Anarchy Despotism Colonial Totalitarian Military Authoritarian Democracy Other

45 Appendix 4. Code book MaxRange2

46

Endnotes

1

By political systems, we mean the fundamental arrangements of political institutions adopted by nations. Often, types of political systems are categorized as different regime types. For example, political systems belonging to the regime type “democracy” ma y have presidentialism or parliamentarian political systems, depending on the institution regulating how cabinets or governments are being formed.

2 David (2007) defines a path-dependent stochastic system as “one possessing an asymptotic distribution that evolves as a consequence (function) of the process's own history.” We have a simpler operational definition of institutional path dependence, namely a statistically significant and substantial contribution from previous institutions on the explanation of variance or event histories in survival or emergence of specific later institutions.

3

We assume rather crudely that the same religion was in majority in 1789. 4

Applying this procedure, an estimate of the empirical distribution of F under independence and compute the F value associated with a random permutation which randomly reassigns each covariate profile to one of the observed sequence, and to repeat this step R (in this case 5,000) times. The test can be performed comparing the groups of nations with various religious majorities historically in order to assess the association. Homogeneity of the difference of within group discrepancy is made on the basis of a generalization of the Bartlett Test and Significance assessed through permutation tests (Studer et al. 2011).

MaxRan ge2 value Demo- cracy level Democ racy Auto- cracy Institutional structure Executive strength Normalal vs. Interim

Head of State Executive Concentration Head of Government Simplified Strength Election of Head of State 1000 QD 1 0 Parliamentarism Constitutional Normal

Republic

Concentrated

Executive Prime- Ministerial Decentralized

Indirectly 995 QD 1 0 Parliamentarism Constitutional Normal

Monarchy Concentrated Executive Prime- Ministerial Decentralized Undefined 990 QD 1 0 Presidential- Parliamentarian Constitutional Normal Republic Separated Executive Prime- Ministerial Decentralized Directly 985 QD 1 0 Divided Executive Constitutional Normal Republic Separated Executive Prime- Ministerial Decentralized Directly 980 QD 1 0 Divided Executive Constitutional Normal Republic Separated Executive Prime- Ministerial Decentralized Directly 975 QD 1 0 Semi- Presidential Constitutional Normal Republic Prime- Ministerial Decentralized Directly 970 QD 1 0 Semi- Presidential Constitutional Normal Republic

Presidential Decentralized Directly 965 QD 1 0 Parliamentarian-

Presidential

Significant Normal

Republic

Presidential Balanced Directly 960 QD 1 0 Parliamentarian-

Presidential

Significant Normal

Republic

Presidential Balanced Directly

955 QD 1 0 Divided Executive Constitutional Normal Republic Prime- Ministerial Decentralized Indirectly 950 QD 1 0 Semi- Presidential Constitutional Normal Republic

Presidential Decentralized Indirectly 945 QD 1 0 Parliamentarian-

Presidential

Significant Normal

Republic

Presidential Balanced Indirectly 940 QD 1 0 Parliamentarian-

Presidential

Significant Normal

Republic

Presidential Balanced Indirectly 935 QD 1 0 Parliamentarian Constitutional Normal

Undefined Undefined

Prime- Ministerial

Decentralized Undefined 930 QD 1 0 Presidential Constitutional Normal

Republic Undefined

Presidential Decentralized Undefined 925 QD 1 0 Accountable

Presidential

Constitutional Normal

Republic

Presidential Decentralized Directly 920 QD 1 0 Accountable

Presidential

Constitutional Normal

Republic

Presidential Decentralized Directly 915 QD 1 0 Presidential Constitutional Normal

Republic

Presidential Decentralized Directly 910 QD 1 0 Presidential Constitutional Normal

Republic

Concentrated Executive

Presidential Decentralized Directly 905 QD 1 0 Parliamentarian Constitutional Governmen

t Acting Undefined Concentrated Executive Prime- Ministerial Undefined Undefined 900 Int 1 0 Interim Parliamentarian Undefined Governmen t Extra- Parliament Undefined Concentrated Executive Prime- Ministerial Undefined Undefined

895 QD 1 0 Presidential Constitutional Normal

Republic

Presidential Decentralized Directly 890 QD 1 0 Presidential Constitutional Normal

Republic

Concentrated Executive

Presidential Decentralized Directly

885 QD 1 0 Council

Parlimentarian

Constitutional Normal

Republic

Prime- Ministerial Decentralized Indirectly

880 QD 1 0 Council

Parliamentarian

Constitutional Normal

Republic

Prime- Ministerial Decentralized Indirectly 875 QD 1 0 Constitutional

Executive

Constitutional Normal

Republic

Prime- Ministerial Decentralized Indirectly 870 QD 1 0 Constitutional

Executive

Constitutional Normal

Republic

Prime- Ministerial Decentralized Indirectly 865 Int 1 0 Parliamentarian Constitutional Parliament

arism obsolete

election Undefined

Undefined Prime- Ministerial Undefined Undefined

860 Int 1 0 Parliamentarian Constitutional Parliament arism illegitimate

election Undefined

Undefined Interim Undefined Undefined

855 Int 1 0 Interim Undefined Interim

Post-

election Undefined

Undefined Interim Undefined Undefined

850 Int 1 0 Interim Undefined Interim

Post-

election Undefined

Undefined Interim Undefined Undefined 845 ED 1 0 Parliamentarian Constitutional Normal

Undefined

Concentrated Executive

Prime- Ministerial Decentralized Undefined 840 ED 1 0 Presidential-

Parliamentarian

Constitutional Normal

Republic

Prime- Ministerial Decentralized Undefined 835 ED 1 0 Monarchical

Parliamentarism

Constitutional Normal

Monarchy Prime- Ministerial

Decentralized Undefined 830 ED 1 0 Monarchical Parliamentarian Constitutional Normal Monarchy Concentrated Executive Monarchy Decentralized Undefined 825 ED 1 0 Divided Executive Constitutional Normal

Republic Prime- Ministerial

Decentralized Undefined

820 ED 1 0 Semi-

Presidential

Constitutional Normal

Republic

Presidential Decentralized Undefined 815 ED 1 0 President Constitutional Governmen

t Acting Republic

Concentrated Executive

Presidential Decentralized Undefined

810 Int 1 0 Interim Undefined Governmen

t Extra-Parlia ment Republic Concentrated Executive Presidential Decentralized Undefined 805 ED 1 0 Parliamentarian- Presidential Constitutional Normal Republic

800 ED 1 0 Presidential Constitutional Normal

Republic

Concentrated Executive

Presidential Decentralized Undefined 795 ED 1 0 Parliamentarian-

Presidential

Significant Normal

Republic

Presidential Balanced Undefined 790 ED 1 0 President Significant Normal

Republic

Concentrated Executive

Presidential Balanced Undefined

785 LD 0 0 Semi-

Parliamentarian

Constitutional Normal

Undefined

Prime- Ministerial Decentralized Undefined 780 LD 0 0 Undefined Constitutional Normal

Undefined

Prime- Ministerial Decentralized Undefined

775 Int 0 0 Interim Undefined Interim

Elected

Assembly Undefined

Presidential

Undefined Undefined

770 Int 0 0 Interim Undefined Interim

Opposition grand coalition Undefined Concentrated Executive Presidential Undefined Undefined

765 Int 0 0 Interim Undefined Interim

Parliament

Plural Undefined

Undefined Interim

Decentralized

Undefined

760 Int 0 0 Interim Undefined Interim

Parliament Dominated Undefined Undefined Interim Decentralized Undefined 755 LD 0 0 Monarchical- Parliamentarian Significant Normal Monarchy Monarchical Balanced Undefined 750 LD 0 0 Monarchical- Parliamentarian Significant Normal Monarchy Concentrated Executive Monarchical Balanced Undefined 745 LD 0 0 Parliammentarian-P residential Constitutional Interim Presidential Republic

Presidential Decentralized Undefined 740 LD 0 0 President Constitutional Interim

Acting President Republic Concentrated Executive Presidential Decentralized Undefined

735 Int 0 0 Interim Undefined Interim

coalition New Regime –

Old Regime Undefined

Undefined

Interim

Undefined Undefined

730 Int 0 0 Interim Undefined Interim

Pre- election coalition Constitutio

nal Undefined

Undefined Interim Undefined Undefined

725 Int 0 0 Interim Undefined Interim

coalition Undefined

Undefined Interim Undefined Undefined

720 Int 0 0 Interim Undefined Interim

New Undefined

Regime Constitutio nal or Pre- election 715 LD 0 0 Parliamentarian Constitutional Normalal

Undefined

Concentrated Executive

Prime- Ministerial Decentralized Undefined 710 LD 0 0 Presidential-

Parliamentarian

Constitutional Normal

Republic

Prime- Ministerial Decentralized Undefined 705 LD 0 0 Monarchical-

Parliamentarian

Constitutional Normal

Monarchy

Prime- Ministerial Decentralized Undefined 700 LD 0 0 Monarchical- Parliamentarian Significant Normal Monarchy Concentrated Executive Monarchical Balanced Undefined 695 LD 0 0 Divided Executive Constitutional Normal

Republic Prime- Ministerial

Decentralized Undefined

690 LD 0 0 Sem-

Presidential

Constitutional Normal

Republic

Presidential Decentralized Undefined 685 LD 0 0 Parliamentarian-

Presidential

Constitutional Normal

Republic

Presidential Decentralized Undefined 680 LD 0 0 President Constitutional Normal

Republic

Concentrated Executive

Presidential Decentralized Undefined 675 LD 0 0 Parliamentarian Dominating Normal

Undefined Concentrated Executive Prime- Ministerial Centralized Undefined 670 LD 0 0 Parliamentarian Dominating Normal

Undefined

Concentrated Executive

Prime- Ministerial Centralized Undefined 665 LD 0 0 President Dominating Normal

Republic

Concentrated Executive

Presidential Centralized Undefined 660 LD 0 0 President Dominating Normal

Republic

Concentrated Executive

Presidential Centralized Undefined

655 Int 0 0 Interim Undefined Interim

New Regime Undefined Concentrated Executive Interim Undefined Undefined 650 Int 0 0 Interim Undefined Interim Old

Regime Constitutio nal Undefined Undefined Interim Undefined Undefined

645 LD 0 0 Monarchical Constitutional Normal

Monarchy Monarchical

Decentralized Undefined 640 LD 0 0 Monarchical Constitutional Normal

Monarchy Concentrated Executive Monarchical Decentralized Undefined 635 LD 0 0 Parliamentarian- Presidential Significant Normal Republic

Presidential Balanced Undefined 630 LD 0 0 President Significant Normal

Republic

Concentrated Executive

Presidential Balanced Undefined 625 LD 0 0 Parliamentarian Overwhelmingi

ng

Normal

Undefined

Concentrated

Executive Prime- Ministerial

Centralized Undefined 620 LD 0 0 Parliamentarian Overwhelming Normal

Undefined

Concentrated Executive

615 Int 0 0 Interim Undefined Interim Old Regime Pre- Election Undefined Concentrated Executive Interim Undefined Undefined

610 Int 0 0 Interim Undefined Interim Old Regime

Reform Undefined

Concentrated

Executive Interim

Undefined Undefined 605 LD 0 0 President Overwhelming Normal

Republic

Concentrated Executive

Presidential Centralized Undefined 600 LD 0 0 President Overwhelming Normal

Republic

Concentrated Executive

Presidential Centralized Undefined

595 LD 0 0 Colony Undefined Normal

Undefined

Concentrated

Executive Colonial

Undefined Undefined

590 LD 0 0 Colony Undefined Normal

Undefined

Concentrated

Executive Colonial

Undefined Undefined

585 Int 0 0 Interim Undefined Interim

dem open to ref opp pos Undefined Undefined Interim Undefined Undefined

580 Int 0 0 Interim Undefined Interim

dem ref open to reform Undefined Undefined Interim Undefined Undefined 575 False Authorita rianism

0 0 Parliament Constitutional Normal

Undefined

Prime- Ministerial

Undefined Undefined 570 FA 0 0 Presidential Constitutional Normal

Republic

Concentrated Executive

Presidential Decentralized Undefined 565 LD 0 0 Monarchical Constitutional Normal

Monarchy Monarchical

Decentralized Undefined 560 LD 0 0 Monarchical Constitutional Normal

Monarchy Concentrated Executive Monarchical Decentralized Undefined 555 LD 0 0 Parliamentarian- Presidential Significant/ Dominant Normal Republic

Presidential Centralized Undefined 550 LD 0 0 President Significant/ Dominant Normal Republic Concentrated Executive

Presidential Centralized Undefined

545 LD 0 0 Parliament Dominate Normal

Undefined

Concentrated Executive

Prime- Ministerial Centralized Undefined

540 LD 0 0 President Dominate Normal

Republic

Concentrated Executive

Prime- Ministerial Centralized Undefined 535 LD 0 0 Monarchical Significant/ Dominant Normal Monarchy Monarchical Balanced Undefined 530 LD 0 0 Monarchical Significant/ Dominant Normal Monarchy Concentrated Executive Monarchical Balanced Undefined 525 Semi-Aut h

0 0 Parliament Constitutional Normal

Undefined

Concentrated Executive