Encroachment Costs

of New Roads

A Summary of the Results of CVM and

"for or against" Studies

Stefan Grudemo 00 9 Z et eh q Q n © $-p Sal © = © &

Swedish National Road and # Transport Research Institute

VTl meddelande 744A - 1998

Encroachment Costs of

New Roads

-a Summary of the

Results of CVM and

"for or against" Studies

Stefan Grudemo

Swedish National Road and

Publisher Publication

VTI meddelande 744A

Published Project code

1994 50004

Swedish National Road and Project

Å Transport Research Institute Effects of new roads on the environment -how should they be taken into account in the Printed in English 1998 planning models?

Author Sponsor

Stefan Grudemo The National Road Administration (VV)

Title

Encroachment Costs of New Roads - a Summary of the Results of CVM and **for or against" Studies

Abstract (background, aims, methods, result)

The Cost Benefit Analysis carried out by the National Road Administration for each road planned, does not take into consideration the negative external effects, such as, environmental encroachment on recreational areas, visual intrusion effects etc.

At the request of the National Road Administration, VTT has carried out a number of CVM studies to find a method for taking these environmental effects into account in road investment appraisals. In addition to the CVM, which gives a direct monetary valuation, the "*for or against" inquiry is discussed, which can yield an indirect valuation of the negative environmental effects.

This report is a summary of the results of all the studies made in the project.

ISSN Language No. of pages

0347-6049 English 29

Foreword

This report comprises the final publication in the project, "Environmental effects of roads - how should they be taken into account in the planning models ?" The project, which was commissioned by the National Road Admin-istration, has been going on over a period of several years and this report is a summary of the different studies per-formed.

VT MEDDELANDE 344

It should be emphasized that a great deal remains to be done in this field. The work will continue as well, but with new financiers.

Special thanks go to Professor Jan Owen Jansson for his valuable comments and suggestions.

Contents

. 1.11. Lv AA Vvk Gk bk kk kak bb kk k kb bb kk abb bk kb b bb kb k kb kb b kb hb b kak hb bk kb bb bk kk h bk kk b hb kk kk bk b kk h bk k kk k kb kk b kk k kk b bb kk k kk kk h kb bk kk kk kk kk kk kk kk kk kak kna I

1 Background and aim baka bab abb bb b bb bb g gb abb b bb b bb kk kak b bb b bk ak bb b kb b bk kk kb b bb b bk b kk bk k bk kk k kk n 11

2 Questions of method bb bb bb bb bb abb b bb bb bk b kb b bk kk kk b kb kk k kk kk kk kak kk kk kk kk k kn k 12

2 d Ti- 12

2.2 For or against" studies kaka GGG b Gk kk ab bb bk k kk abb bb kak b bk kk kb b bb kb k hb k kk hb bb bb kk kk kk k hb kk k kk kk en 13 2.3 Alternative methods bab bb bb b bab ggg abb bb bb bb ggg abb bb b bk beh b bk bk b kk kk bh bb bb b bb bk k kk kk k kk a 13 2.4 An attempt to classify different valuation methods kk kk kk kk kk kk kk k kk kk kk kk kk k kk kk ka 14

3 Road constructions and question design in CVM studies iv AA kk kk kk kk kk kk kk kk kak 15

n f eei 15

3.2 Gillbergaleden [The Gillberga link] in Eskilstuna ... ... LL LLLL LLA AAA kk kk kak kk kk kk kk kk kk bk k kk kk ka e a 15 3.3 Osbyholm bypass bb bb b bk gg bg gaga GGG bb bb bb ggg g ga abb bb b bb kk kb b kb b bb kk kak bk b bk kk kk kk kk kk kk hb kn kk k k kk 16 3.4 Klockartorpsleden [The Klockartorp link] in Västerås VV kk kk kk ava k kk kk kk kk k 17 3.5 Söderleden [the South link] in Norrköping kb b bk kak kb b bb kk kk kk k bk kk k kk a en 18 3.6 Säterivägen [Säteri Road] in Mölnlycke vv k bk kak kk k kk abb b k bk k kk kk kk bk kk k kk ka a e 19

4 Results of completed studies lk kk kk WWW WWW kk kk kk kk kk kak k kk kk bb bb bk kk kk kk k kk kk kk k kk k kk k k k k kk kk kk a 21 4.1 Spread of willingness to pay kb bb bb bb bb bb bb bb bb bg gbg kak b bb bb b bb b bk kk kk k kk kk k kk k kk k kk k kk kn 22

5 Municipal referendums concerning road projects and "*for or against" studies ... 24 5.1 Vallaleden [the Valla link] in Linköping kk kk kk kaka k kk k kk kk kb bk kb kk kb bb b kb bb bk b kk kak kk a v 24 5.2 Broleden [the Bro link] in Vänersborg ekv kk kkk k kk k kk kk kk kk kk kk kk kk kk kak k kk k kk ka a 26

6 Conclusions kb bb bk kaka bb bb bb bb gagga abb bb b bb b kb kk kak bk b bk b kk k kak kb bb bk k kk bb bb b bk kk k kk kb kb bb bb b bb bk kk k kk kk a 28

7 References ekv bb kk aaa GGG GGG bb b bb gg kk bb bb bb kk k kk kk ahh bb b kk bk kak bb k bk kk kk hh b kb kk kk kk kk kk kk k hk kk k k k kk 29

Appendices

Appendix 1 Map of E6 Ljungskile kb b bb kak b bk bb bk kk k bb bb bb bb b kb bk kk kk kk n 31 Appendix 2 Map of Gillbergaleden kk kak bk kk kk kb kk kk kk kk kk k kk kk kk a 32 Appendix 3 Map of E22 past Osbyholm ke ke kk kk kk kk kk kk kk k kk kk k bb b bb bb bb b kk kk keen 33 Appendix 4 Map of Klockartorpsleden bb abb kaka kk bk kk kk bb k kak k k 34 Appendix 5 Map of Söderleden bb b bb bb abb bb bb kk kk kk b kb k kk k kk e 35 Appendix 6 Map of Säterivägen kaka bb b bb bab bb bab bb kak bb b bb bk k kk kk kk kk kk kk k e 36 Appendix 7 Map of Vallaleden bb bab bk k bb b bk k kb b bb bk kk kk k kk k kk ke e 37 Appendix 8 Map of Broleden bab bab b bb bk bb b bb k kk kk kk kb kk kk ke 38

Encroachment Costs of New Roads - a Summary of the Results of CVM and for or against" Studies by Stefan Grudemo

Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute (VTT 581 95 LINKÖPING

Summary

The National Road Administration's social-economic appraisal, the Cost Benefit Analysis, does not cover all the environmental effects that may occur when a new road is built, such as, visual intrusion and encroachment on natural and recreational areas. VTT has been com-missioned by the National Road Administration to elim-inate this problem by developing a method of evaluating these, often negative effects on the environment.

A number of studies have been carried out within the framework of this research assignment. These have partly been in the form of attempts at monetary valua-tion, using the "Contingent Valuation Method" CVM, which roughly speaking means, hypothetical market valuation, and partly in the form of **for or against" stud-ies. The former method is particularly suitable when winners and losers are distinctly separate groups, and the latter is appropriate when the groups overlap to a great extent, which is usually the case when the invest-ment concerns a local road.

CVM studies of six different road projects have been carried out. The spread of willingness to pay, to be spared the road completely, or to have it built in a tunnel or in a different direction so as to leave a particular rec-reational area undisturbed, is very great. There are vari-ations in value from zero up to several thousand Swedish kronor. However, the average value is 400-500 SEK/per-son. The values remain constant irrespective of wheth-er it is a question of a lump sum or an annual amount. This is absurd and reveals a flaw in the method. Question techniques must be further developed in order to eliminate this particular fault and others.

VTT has analyzed the results of a municipal referen-dum on a controversial road project - Vallaleden [the Valla

VT] MEDDELANDE 34

link] in Linköping. Approximately 74% of those taking part in the referendum voted against the road. Accord-ing to the Cost Benefit Analysis, Vallaleden would have been extremely profitable and financed by the State/the National Road Administration. That a large majority of the people of Linköping voted against the road in spite of this indicates that the encroachment costs were judged to be very great, as being at least on the same

scale as the benefits.

VTT has also carried out a or against" study of the planned, but now aborted, Broleden [the Bro Link] in Vänesborg which, as was the case with Vallaleden, would have meant a very considerable shortcut for many in the local community, but which also would have in-volved extensive encroachment on popular rambling areas. In the inquiry, 16% stated they were in favour of the link, 49% stated that they were against it and 35% claimed to have no opinion on the matter. If this is the equivalent of the results of a referendum in Linköping, then the share of no-votes would have been 75%. It may also be kept in mind, that when residents in the munici-pality of Ekerö near Stockholm voted in 1991 concern-ing Västerleden [the West link], 75% voted against it.

The results of completed studies indicate that en-croachment costs, in certain cases, can be of such a magnitude, that a project that in terms of the Cost Ben-efit Analysis should have been an extremely profitable one, in reality becomes social-economically unviable. Therefore, the conclusion to drawn must be that today's road impact assessments need supplementing. Despite the problems that exist with the CV method and "for or against" studies, they may be the supplement required.

1 Background and aim

A social-economic appraisal, known a Cost Benefit Analysis, is carried out for all newly planned roads in order to establish whether the proposed road will be profitable or not. This is done using methods developed by the National Road Administration. As many as poss-ible of the effects the road is expected to give rise to are given a monetary value. These effects are divided into traffic economic effects:

e changes in accidents; e changes in travelling time;

e changes in direct costs, such as, for vehicles and for maintaining roads and streets; and into environ-mental economic effects:

e changes in the number of people suffering noise related impairment;

e changes in the number of people exposed to high levels of carbon monoxide;

e changes in the number of people suffering from the road's "*barrier" effect.

For the majority of road constructions, traffic economic effects are the dominating item. However, all environ-mental effects are not covered in the Cost Benefit

Analy-VTl MEDDELANDE 7344 A

sis. The National Road Administration hitherto has not found it possible to put a monetary value on such ef-fects as visual intrusion and encroachment on natural and recreational areas.

The National Road Administration has been aware of this flaw in the Cost Benefit Analysis. VTT has there-fore been entrusted with the task of trying to assess whether this fault seriously distorts the Cost Benefit Analysis and if so, whether it is possible to eliminate it by means of some method of monetary valuation of such environmental effects. In contrast to these environmental effects of road investment today which do have a mon-etary value (and which usually result in a positive net effect), encroachment effects would almost exclusively result in a negative net effect for the new road. VTT has conducted a number of studies in the form of question-naire inquiries within the framework of this assignment. The purpose of this publication is to put together the findings of previous questionnaire inquiries. A subsidi-ary aim is to present different methods for appraising those encroachment costs that are not taken into account in today's Cost Benefit Analysis.

2 Questions of method

2.1 CVM studies

The method we have tested in our attempts to put a monetary value on the environmental effects mentioned is called the Contingent Valuation Method (CVM), or the CV method, which freely translated means, hypotheti-cal market valuation. This method uses questionnaires to ask individuals affected by a particular new road which encroaches on a natural and/or recreational area, or which spoils the view from the house or apartment, what they would be (hypothetically) prepared to pay to be spared the new road, or to have it built in a tunnel which would reduce or eliminate the inconvenience in-volved.

It is essential, when putting this kind of hypothetical question, to describe the situation as accurately as pos-sible, thereby minimising the risk of the respondent mis-understanding the question. It is also vital that the rea-soning is as realistic and easy to understand as possi-ble, so that the respondent feels motivated to answer. One way of making the question more realistic can be to establish the respondent's willingness to pay, by as-certaining the maximum increase in local taxation that would be acceptable, in return for the elimination of any encroachment caused by the particular road.

The majority of CV studies conducted by VTI have concerned completed roads. The reasoning behind this is that a questionnaire sent out immediately prior to the construction of a controversial road can be distorted by people becoming emotionally distraught. The willingness to pay specified in such a situation, can be biased for tactical reasons that are difficult to see through.

The advantage of conducting the CV study retroac-tively, which more often than not is the practice, is that by then the emotional storm has very often abated and the questionnaire does not affect the debate at all. The disadvantage is that people, retroactively, may not feel motivated to fill in the questionnaire as the issue has al-ready been decided. The decision cannot be altered and it may be difficult for them to think back to the situa-tion that pertained prior to the road construcsitua-tion, and, retroactively, state how much they are willing to pay to achieve what is now unachievable. A willingness to pay, specified retroactively, would probably underestimate the appraised willingness to pay.

The CV method is particularly suitable when win-ners and losers are distinctly separate groups. A typical case in road planning is when a highway is to be con-structed as a bypass outside a built-up area. Those with

12

most to gain in such a case are the users of the high-way and some of the residents in the central parts of the town. The gains for both groups are included in the Cost Benefit Analysis as plus items. The losers are resi-dents living in the vicinity of the new road who will be inconvenienced by encroachment on rambling areas, traffic noise and so forth.

These people gain nothing, or very little, through the creation of the new road and their losses are not taken into account in today's Cost Benefit Analyses. If these environmental costs were expressed in monetary terms, the CVM studies would be able to create better balance in the appraisal.

Preliminary studies using CVM that have been carried out on VTT:s initiative are:

e EG Ljungskile; reconstruction of E6 at Ljungskile in Uddevalla municipality at the west coast, ongoing road project (Trouvé and Jansson, 1986).

e Gillbergaleden in Eskilstuna; reliefroad, which how-ever at present is not under consideration for con-struction (Landell and Smith, 1988).

Retrospective studies using CVM that have been car-ried out are:

e Osbyholm bypass; reconstruction of E22 (previ-ously E66) at Osbyholm in Hörby municipality in the county of Skåne, opened 1986 (Grudemo,

1987).

e KJockartorpsleden [The Klockartorp link] in Väster-ås; E18 through eastern parts of Västerås, opened 1981 (Grudemo, 1988).

e Söderleden [The South link] in Norrköping, link in southern parts of Norrköping between E4 and E22 (previously E66), opened1984 (Landell and Smith, 1988).

e Säterivägen [Säteri Road] in Mölnlycke near Gothen-burg, approach from highway 40 to central Möln-lycke, opened 1982 (Grudemo, 1988).

2.1.1 -A spectacular example of applying CVM CVM is controversial and is the subject of criticism in the economic fraternity too. In its homeland USA, it is frequently the subject of debate. However, since the mid 19805 it has been applied in a number of different con-texts. A case that attracted a lot of attention is the fol-lowing one (San Francisco Chronicle, 1993, The Eco-nomist, 1991);

In 1998 the oil tanker Valdez sprang a leak off the coast ofAlaska, causing extensive damage to animal and plant life. The state of Alaska appointed a commission that, with the help of CVM, estimated the damage at almost 3 billion US dollars. In 1991 the Exxon company, which owned Valdez, made an agreement with Alaska and paid 1 billion US dollars compensation for the dam-age caused by the leak.

In order to avoid such enormous amounts of dam-ages in similar accidents in the future, Exxon and a few other companies initiated a campaign aimed at discred-iting the CV method. The intention, quite simply, was to make it impossible for the method to be used as a means of exerting pressure in damage claims. Exxon received support from a number of eminent economists who were of the opinion that there was a hopeless ten-dency to bias in the method, and that it was unsuitable both as a means of forming general policy, and of as-sessing damage.

This infuriated other distinguished economists who were advocates of CVM. They were of the opinion that the whole thing was an attempt by the major oil compa-nies to totally destroy a useful method for egoistic pur-poses.

2.2 "For or against" studies

Despite efforts to describe the hypothetical situation as accurately as possible, people may find it difficult to put a monetary value on the negative environmental effects a road can give rise to. Some may also consider it un-ethical to put a monetary value on the environment. In addition to this, there is the risk of under or overes-timating the value. This means that the stated willingness to pay is an unreliable criterion for appraising encroach-ment costs.

Another way of understanding this category of nega-tive environmental] effect would be, in a questionnaire inquiry, to ask those people affected by a new road, both as road users and ramblers in areas impaired through encroachment, whether they want the road or not. This type of or against study" is suitable for a local road for example, since the winners and losers are the same people, that is, they are the local residents. In such a case it is possible, in the inquiry, to cover all those who can conceivably be affected by the proposed road. On the one hand, the new road would mean traffic eco-nomic gains in the form of shorter travelling times, re-duced accident risks and so forth for all concerned or for the greater majority of local residents; on the other hand, it would mean impaired recreational opportunities, traffic noise in the immediate environment and so forth. When taking sides for or against a road, the local com-munity naturally weighs the traffic economic advantages

VT! MEDDELANDE 7344 A

against the environmental disadvantages. Provided that the local community is well informed and that the ma-jority of the effects are local, the overall assessment that can be shown by means of such a questionnaire inquiry provides a relevant supplement to the sub-effect values of the Cost Benefit Analysis.

The *for or against" study that has been performed concerns Broleden [the Bro link] in Vänersborg south of Lake Vänern which is a link road that was never built and which at the present point in time is not of interest (Grudemo, 1993). Furthermore, there was an analysis of the referendum in Linköping (Grudemo, 1990). Even this link, which should have been part of the outer ring, has been taken off the drawing board.

2.3 Alternative methods

Instead of asking what people are (had been) prepared to pay to achieve something, one can ask them to state the minimum amount they are (would have been) pre-pared to accept for some form of inconvenience. This questioning technique is a variant in CVM. Despite the fact that both these question techniques are intended to measure the same values, the latter does have a tendency to result in higher amounts. (Cummings et al. 1986 p.35) Moreover, it can be appropriate to differentiate be-tween studies of "stated" and "revealed" preferences. CVM belongs to the former category since respondents are not required to reveal their stated willingness to pay. There is a certain risk of conceptual confusion here since "Stated Preference" (SP) in traffic planning is used as a term for a more specific method primarily applied to converting variations in transport qualities into "*gener-alised costs", that is to say, for appraisal of travelling time and comfort. It is true that there is no generally accepted definition of the SP method in the narrower sense, but the use of experimental designs for hypotheti-cal choice situations is typihypotheti-cal. What this entails is that the respondents have to specify how they would choose between different qualitative choices in a real choice situation (Bovy and Bradley, 1985, Transportation, 1994, Wildert, 1992).

However, appraisal of environmental encroachment can in part be carried out using the same method. One can, for example, use pre-printed cards on which an amount is specified which the subject has to pay in or-der to preserve a well-defined recreational area. It is possible to vary the amount and thus narrow down the full extent of the subject's willingness to pay.

Sometimes there is talk of willingness to pay stud-ies. This concept includes CVM and other SP methods as well as "Revealed Preference" (RP) studies in which respondents really have to pay the amount they stated they were willing to pay.

A further method is positional analysis (Söderbaum, 1976). In this method two or more alternatives are con-trasted with each other. Each of the alternatives leads to different effects and is appraised from the viewpoints of various interest groups. The various groups may con-sist of residents from different areas, road users, tax-payers and so forth. There is nothing to prevent one individual being found in several groups. Preferences are then expressed from the viewpoint of each respective interest group. Qualitative criteria are used. These can consist, for example, of a 3 point scale such as: **un-acceptable", "acceptable" and ""good". Positional analy-sis, in contrast to the CV and SP methods, measures the effects in non-monetary terms.

2.4 An attempt to classify different valuation methods

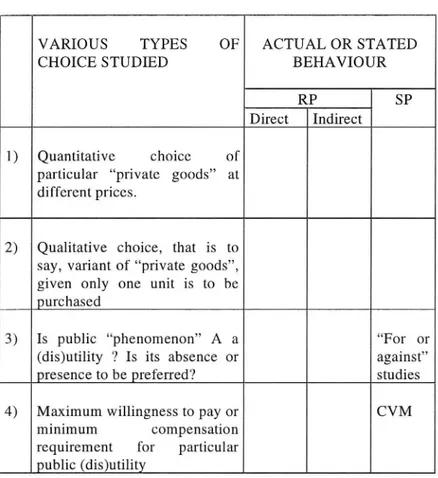

In the table on the following page, an attempt is made to classify different methods for measuring popular demand for, or valuation of, different things.

A dividing line is drawn in the table between RP and SP. Please note that the concept SP is used here in a broad sense and thus also includes CVM. RP is subdivided into studies of direct and indirect behaviour.

For instance, there is no direct market price for noise, nor is it possible to purchase on any market. However, it is possible to make an indirect valuation by studying how house prices change as soon as a source of noise, such as a road being constructed in the vicin-ity, materialises.

It is possible to distinguish between four different kinds of choice. The first is quantitative choice, which is the main subject of basic economic micro-theory, that is to say, the amount of a given product that is in de-mand at a given price. The second is qualitative choice. This means that by studying discreet choices as a func-tion of the attributes and prices of alternative goods, it is possible to deduce the value of each attribute. This is where it is possible to place SP in its narrower sense. The third and fourth kinds of choice concern "public goods" and this is where the methods employed in the studies summarised in this report can be placed. Pos-itional analysis can be put together with the ""for or against" study. The results of Vallaleden [the Valla link] referendum can be said to show "revealed preferences" which, indirectly, make it possible to assess the encroach-ment costs of a road through Vallaskogen [Valla Forest].

Table 1 Classification of methods for assessing popular demand for/valuation of different (dis)utilities.

VÄRIOUS TYPES OF ACTUAL OR STATED

CHOICE STUDIED BEHAVIOUR

RP SP

Direct Indirect

1) |Quantitative choice of particular private goods" at different prices.

2) [Qualitative choice, that is to say, variant of "private goods", given only one unit is to be purchased

3) |Is public *phenomenon" A a "For or (disjutility ? Is its absence or against"

presence to be preferred? studies

4) |Maximum willingness to pay or CVM

minimum compensation requirement for particular public (disj)utility

3 Road constructions and question design in CVM

studies

3.1 EG at Ljungskile

The new stretch of road through the built-up area is under construction and is being constructed as a mo-torway with a maximum speed limit of 110 kph. It is being built to enhance both road safety and accessibil-ity.

Ljungskile is situated in the south of Uddevalla mu-nicipality and has a population of close on 3,000. Today the E6 passes through the built-up area along the shore-line, between the houses and Ljungskile-viken [Ljungskile Bay]. The maximum speed limit here is 70 kph.

Initially it was intended that the new road should be constructed 60 metres from the old one and across Ljungskile-viken on a three metre high embankment with a noise barrier of equal height. The vehement protests raised against this led to the National Road Administra-tion drawing up a new alternative. According to this, the new road will be constructed in a sunken shaft parallel with the old one, which is to be used for local traffic.

In the Ljungskile case, it is not so much a question of encroachment on natural or recreational areas but rather of the "barrier" that the new road creates between the built-up area and the bay. However, the new solu-tion to the problem, that is the sunken shaft, has meant that the visual intrusion effect of the embankment and the noise barrier will, at least in part, be eliminated.

Environmental encroachment has occurred immedi-ately south of Ljungskile. Here the E6 was constructed along Bratteforsåns [the Brattefors river] valley which has natural scenery of national interest, with its wind-ing river surrounded by slopwind-ing hillsides covered in de-ciduous forests. This stretch of road was opened in September 1991.

The study of the E6 through Ljungskile contained the CV question below.

We may assume that the following question pertains to a real situation.

3.2 Gillbergaleden [The Gillberga link] in Eskilstuna

The link has not been built. If it is, it will be constructed in the Southwest of the Eskilstuna built-up area. The length of the link would be 2.1 km and it would relieve the traffic on the neighbouring Gillbergavägen [Gillberga Road], which is lined with houses and a school. Gill-bergaled is included as a future alternative in the event of there being a massive increase in the amount of traf-fic.

The link would be an extension of the current Gill-bergaleden [the Gillberga link] and be constructed along the Southeast edge of Kronoskogen [the Krono Forest] approx. 50 metres from single and multi-family dwell-ings in the areas of Råbergstorp, Myrtorp and Väster-malm. Kronoskogen primarily consists of deciduous forest and meadows and is crossed by several natural footpaths.

Should the link be built, it will cross an exercise track and encroach on an allotment-garden area. It would also create a barrier and curtail access to Kronoskogen for residents and others wishing to use the forest. However, the total area of the forest would not be reduced that much, since the road would be built on its edges.

The link was primarily intended for local traffic and in this respect is comparable with Vallaleden [theValla link] in Linköping and Broleden [the Bro link] in Väners-borg.

east ?

... Swedish crowns.

... Swedish crowns.

Assume that the municipality could influence the motorway project by investing its own resources.

What then is the maximum amount you, as a member of the municipality, would be willing to pay, to have the motor way built in a different direction - which will be more expensive than West 1 A - for example,

And what is the maximum amount you would be willing to pay to be spared the road completely ? (In this case the money could conceivably be used to reduce traffic noise on the existing road though Ljungskile).

The CVM study of Gillabergaleden formed part of a more extensive study in a degree project, which included a number of attempts at appraising the environmental costs of road investments. The questionnaire on Gill-bergaleden contained the following CV question:

40 metres at the nearest point). It is here that the E22 causes problems in the form of noise, exhaust fumes and visual intrusion. From once having had a plot of land bordering on a river, these homeowners now have one that practically borders on a Euro highway.

Answer as in alternative 1 SEK.

Answer as in alternative 2

(Put a ring around your answer)

Assume that the municipality decides to build Gillbergaleden through the edges of Kronoskogen.

Assume now that there is a more expensive alternative which entails the road being built in a tunnel under Kronoskogen. Your immediate environment would, in that case, remain the same as it is today. The road would be funded through increases in local taxation.

What is the maximum Jump sum members of your household would be ready to pay (through increases in local taxation) for the tunnel, to thereby preserve your immediate environment?

0 SEK 200 SEK 400 SEK 600 SEK

800 SEK 1,000 SEK

1,200 SEK 1,400 SEK 1,600 SEK 1,800 SEK 2,000 SEK 2,200 SEK

2,400 SEK -2,600 SEK 2,800 SEK 3,000 SEK 3,200 SEK 3,400 SEK

3,600 SEK 3,800 SEK 4,000 SEK

Higher amount, namely SEK.

3.3 bypass

Osbyholm is a built-up area in Hörby municipality with a population of approximately 400. The E22, (or E66 as it was then called) which passes Osbyholm, was opened for traffic in 1986 and is 2.9 km long. The bypass is built in the form of a major road. The speed limit alter-nates near the built-up area between 90 and 110 kph (for northbound traffic). Previously the Euro highway passed through the village. The reason for constructing it out-side the village was to enhance road safety and reduce traffic noise.

After reconstruction, the E22 stretches immediately north of Osbyholm. It passes between Osbyholm cas-tle and the built-up area through the approximately 12-acre large engelska parken [the English Park], a decidu-ous forest of oak and beech trees adjacent to the castle. At the castle and park, the road crosses Hörby river on a bridge, and continues northwards over arable land.

A residence belonging to the castle and situated in the park, as well as a few private houses in the north of Osbyholm, lie in very close proximity to the road

(30-16

In a report from 1981, the stretch that was built was considered by the National Road Administration to be the most suitable one. The alternatives that were rejected were: a stretch of road parallel to the thoroughfare and one on farming land south of the village.

The inhabitants of Osbyholm and several experts protested against this choice of alternatives. The county architect, the environmental protection director and the county archaeologist had reservations about the county administrative board's decision to approve the Road Administration 's work plan (The National Road Admin-istration 1981).

At a late juncture in the discussions concerning the stretch of road at Osbyholm, an alternative proposal was put forward for a stretch north of the castle. The Road Administration never investigated this alternative. On the contrary, they stated that, because it entailed a longer stretch of road, it would be approximately 3 million SEK more expensive than the alternative opted for.

In a pilot study, carried out by the Swedish Road and Transport Research Institute, of the inhabitants of

Osbyholm, it became evident that the majority of those not living in the vicinity of the road had no objections to it. Engelska parken [the English Park] was generally regarded as being poorly managed and as not being worthy of concern. The CV study in Osbyholm was therefore carried out as a special case and all those liv-ing in the vicinity of the road were interviewed in their homes. The question was:

noise but this has been reduced by sinking the road and erecting noise barriers.

What remains of the green area today are strips of between 30 and close on 100 metres between the houses and the noise barriers (or the fences where the green area is still rather wide). The green area consists mainly of coniferous forest with a sprinkling of deciduous trees. Prior to the construction of the road there was also some

through voluntary contributions from the public.

... SEK.

Assume that the National Road Administration chose between building the E66 in accordance with the

proposal you prefer or through engelska parken (in accordance with the alternative opted for), and the latter

stretch was the one chosen because it was the cheaper of the two alternatives.

Further assume that the National Road Administration could have been persuaded to opt for the proposal

you preferred, provided the extra costs involved (incurred by the longer stretch of road) had been covered

What is the maximum Jump sum you and members of your household would have been able, or willing, to

pay for the E66 stretch preferred by you, instead of the one we have now?

3.4

Klockartorpsleden [The Klockartorp link] in

Västerås

The link is a 4.6 km long city motorway and has a speed

limit of 90 kph. It was built between 1979 and 1981 and

stretches through the eastern part of Västerås.

Klockar-torpsleden replaced Stockholmsvägen [the Stockholm

Road] as a stretch of the E18. It was felt that the latter,

which lies a few hundred metres further north, would

not be capable of coping satisfactorily with the

increas-ing amounts of traffic due, among other reasons, to the

fact that there were several level crossings. A raising of

the standard of the road was also considered to be an

inferior alternative to building Klockartorpsleden.

Approximately 3 km of the road stretches

longitudi-nally through the large intact green area which, prior to

the construction of the road, was untouched. Its width

was then between 100-200 metres. Along

Klockar-torpsleden and the remaining green areas, there are a

school and several large housing areas with blocks of

flats for the most part but with some private houses too.

Traffic along the road generates a certain amount of

VT MEDDELANDE 7344 A

meadowland in the area and the terrain was hilly in part.

There were, and still are, plenty of well-worn paths in

the area. There used to be some football pitches and

playgrounds, which lay in the direction of the road, but

these were taken away when Klockartorpsled was built.

Planning commenced during the early 19705.

Ac-cording to an inquiry the link was preferable to

rebuild-ing Stockholmsvägen. Both "Action E 18" and the

Västerås Environmental Group were active in trying to

have the E 18 built outside Västerås (a stretch had been

staked out for this). If this should prove impossible, it

was argued, then it was preferable to upgrade

Stock-holmsvägen. The possibility of building a part of

Klock-artorpsleden in a tunnel was looked into but rejected on

grounds of expense (The National Road Administration

1977).

In our CVM study of the road three different

ques-tions concerning willingness to pay were formulated in

order to see what effect this would have on willingness

to pay.

Questionnaire 1:

house/flat etc.)

... SEK.

During the period from 1974-1976 investigations were carried out into the prerequisites for constructing

part of Klockartorpsleden in a tunnel, primarily to be able to preserve the green areas. However, these plans

were rejected since the costs involved were considered altogether too high.

Imagine the following hypothetical situation (Think the situation over carefully and then answer as

realistically as possible); Assume that the department of roads could have been prevailed upon to build the

entire Klockartorpsleden in a tunnel (**an underground Klockartorpsled''), provided the extra costs a tunnel

would have involved had been covered in the form of voluntary public contributions.

What is the maximum Jump sum you and members of your household would have been able, or willing, to

contribute to have had the whole of Klockartorpsleden built in a tunnel, thus preserving the green areas?

(Please answer on the basis of conditions today: today's purchasing power, the location of your present

Questionnaire 2:

in its present form.

preserving the green areas?

house/flat, your current income etc.).

Answer as in alternative a

... SEK.

Answer as in alternative b

Put a ring round your maximum amount

During the period from 1974-1976 investigations were carried out into the prerequisites for constructing

part of Klockartorpsleden in a tunnel, primarily to be able to preserve the green areas. However, these plans

were rejected since the costs involved were considered altogether too high and Klockartorpsleden was built

Imagine the following hypothetical situation: Assume that it had been possible to build the entire

Klockartorpsleden in a tunnel ("an underground Klockartorpsled''), provided the extra costs had been

covered by means of an increase in local taxation. This would of course have affected you as well as every

other taxpayer in Västerås municipality. The question now is, how much more tax you would have been

prepared to pay in order for the tunnel to have been a reality?

Accordingly, we would like to have an answer to the following question: What is the largest amount in

local taxes you personally would have been willing to pay, that is to say how much more tax per year

would you have been prepared to pay, in return for having had Klockartorpsleden built in a tunnel, thus

(Please answer on the basis of conditions today: purchasing power today, the location of your present

0 SEK

100 SEK

200 SEK

300 SEK

400 SEK

500 SEK

600 SEK

700 SEK

800 SEK

900 SEK

1,000 SEK

1,100 SEK

1,200 SEK

1,300 SEK

1,400 SEK

1,500 SEK

1,600 SEK

1,700 SEK

1,800 SEK

1,900 SEK

2,000 SEK

More than 2,000 SEK, namely... SEK.

3.5

Söderleden [the South link] in Norrköping

The link is 4.6 km long and stretches in a west-east

di-rection through the south of Norrköping. It was built in

the period from 1982-1984 and the intention was to

eliminate the traffic from the centre of the town as well

as to create a link between the E4 and the E22 (the old

18

E66). The road has two lanes and has a speed limit of

70 kph.

Söderleden was built through green areas that

pre-viously had lain in the form of narrow strips between

the surrounding housing areas. In part the green areas

consisted of hilly meadowland and woodland. Very little

VT] MEDDELANDE 73 44A

of the green areas remain today.

Areas with houses and blocks of flats lie adjacent to the road. Several plots of land with houses in the areas of Kneippen and Klingsberg now border straight onto the road, with just a noise barrier separating them from it. The barrier and the fact that the road is sunken mean that disturbance from traffic noise is moderate.

A sports ground with several football pitches lay in the way of the road. The sports ground is still there but has fewer football pitches.

The study of Söderleden was included in the same degree project as Gillbergaleden. The CV question was formulated as follows:

in the area. It is approximately one kilometre long and stretches from Råda Porter to the manor farm.

The area, through which Säterivägen stretches, is hilly and consists of meadowland and deciduous forests with a sprinkling of oak trees. The terrain slopes down towards Lake Råda and there is a plenitude of pedes-trian and cycling paths, some of which have been as-phalted.

The first time the plans for Säterivägen were pre-sented was in the mid 1960s. Even at that juncture the National Road Administration was aware that the road was to be built through an area of sensitive natural

scen-environment then please write 0 SEK.)

Assume it had been possible to build Söderleden; where it now passes through housing areas, in an underground tunnel. This would have preserved the green areas and the environment but entailed higher costs. The tunnel could have been funded by means of increased local taxes.

How much would your household have been willing to pay in the form of a lump sum via local taxes for such a solution ? (If you believe that Söderleden would not have led to any changes in your local

SEK.

3.6 Säterivägen [Säteri Road] in Mölnlycke The road is a 2.6 km approach road from highway 40 to Mölnlycke centre. It was built between 1981-1982 to relieve the thoroughfare Allé Road and at that time the only approach road. Säterivägen has two lanes and has a speed limit of 70 kph.

The road stretches in an arc near Rådasjön [Lake Råda] which has a rich bird life, passing as close as 50-60 metres from it. The northern part of the road is ap-proximately 40-50 metres away from some houses in the Råda Portar residential area. It is here that traffic on Säterivägen generates a certain amount of disturbance due to noise and gives rise to visual intrusion.

The road is built near Råda Säteri [Råda Manor Farm] which is situated close to the lake. There is also a rid-ing-school in the vicinity of the lake. Near the manor farm the road crosses and intersects a gravelled road and an avenue of chestnut trees that borders onto it. In earlier times the gravelled road was the only motor road

VT] MEDDELANDE 7344 A

ery. As an alternative, an outline diagram was made of a tunnel under a couple of housing areas. However, these plans were rejected on grounds of cost.

During the 1970s and up to the commencement of construction, field biologists, members of the youth associations of the Centre Party (CUF) and the Social Democrats (SSU) and the "Anti-Säterivägen Associa-tion", worked actively to stop the road. They were of the opinion that it was possible to solve the traffic prob-lems of Allé Road by erecting noise barriers and fitting nearby houses and flats with triple glazing.

When building commenced there were riots between police and demonstrators. Seven of the latter were pros-ecuted and fined for "*disobeying the police" (Korn, 1983).

The CVM study's willingness to pay questions were formulated to include both open responses and forced responses selected from a pre-printed scale. The ques-tions are displayed below:

Suppose that there is no Säteriväg. The natural environment at Lake Råda and Råda Manor Farm are preserved. There is altogether too much traffic on Allé Road which has to be reduced.

This can be achieved either by building Säterivägen or by building a road tunnel under the Råda Portar and Manor Farm housing areas. The tunnel is however more expensive than the road, both as concerns

construction costs and operational costs. If the tunnel is to be built, the municipality must therefore contribute to the funding and this entails increases in local taxation.

The question now is; what is the maximum amount you personally would be willing to contribute annually, for example, in the form of increased local taxes, in return for getting the road tunnel instead of

Säterivägen? In other words, we are not asking about an increased tax rate, what we are asking about is the total amount, expressed in Swedish crowns (SEK) per year, you would be willing to pay.

Answer as in version 1

Your maximum annual amount: ... SEK.

Answer as in version 2

Put a ring round your maximum annual amount.

0 SEK 100 SEK 200 SEK 300 SEK 400 SEK

500 SEK 600 SEK 700 SEK

800 SEK 900 SEK 1,000 SEK 1,250 SEK 1,500 SEK 1,750 SEK 2,000 SEK 2,250 SEK

2500 SEK 2,750 SEK 3,000 SEK 3250 SEK 3,500 SEK 3,750 SEK 4,000 SEK 4,250 SEK

4500 SEK 4,750 SEK 5,000 SEK

More than 5,000 SEK, namely... SEK.

4 Results of completed studies

As is evident from the preceding chapter, questions con-cerning willingness to pay are not directly comparable. The specified willingness to pay may apply to

e a tunnel instead of a particular road,

e a different direction instead of the present one, e upgrading of existing road.

The answers given can also differ from one another due to the fact that they concern

e lump sums or annual amounts (for example by means of local tax increases),

* household amounts or personal amounts.

Moreover, the amount can be specified in two different ways:

e Freely chosen amount (open response),

e Amount selected from a pre-printed scale (forced response).

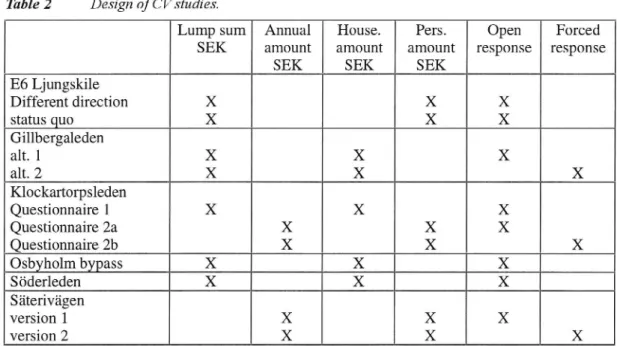

The above are displayed in Table 2

Table 2 Design ofCVstudies.

Please note the CVM studies were carried out from 1987-1988. The average values below therefore need adjusting upwards by about 30-40% to be expressed at 1994 levels.

A Directly comparable.

(Ilump sum, household amount, and open response)

e Klockartorpsleden, questionnaire 1: average value 464 SEK.

e Osbyholm bypass:

average value 22,350 SEK. e Söderleden:

average value 7.018 SEK. e Gillbergaleden, alt. 1:

average value 355 SEK.

Lump sum SEK Annual amount SEK House. amount SEK Pers. amount SEK Open response Forced response E6 Ljungskile Different direction status quo X X X X Gillbergaleden alt. 1 alt. 2 P4 4 P Klockartorpsleden Questionnaire 1 Questionnaire 2a Questionnaire 2b P4 [P4 P4 >4 > på > på > Osbyholm bypass P4 | Söderleden på > Säterivägen version 1 version 2 X X P4 [PA ]PD A] -> Då X X X

If we group the various objects according to how it is possible to compare them and, in addition, add the average values from the different studies, we arrive at the results to be found below. Unfortunately it is impos-sible to present any comparable average values for the Ljungskile study. This is due to the fact that the values in this study were worked out using a different method than the one used in the other studies (among other things, the zero-offer was not included).

VT] MEDDELANDE 3 44A

B Directly comparable.

(annual amount, personal amount, open response)

e Ljungskile, different direction.: e Ljungskile, status quo:

e Klockartorpsleden, questionnaire 2a: average value 372 SEK.

e Säterivägen, version 1: average value 371 SEK.

C Partially comparable (different design of scale with pre-printed amount).

(annual amount, personal amount, forced response)

e Klockartorpsleden, questionnaire 2b: average value 376 SEK.

e Säterivägen, version 2: average value 526 SEK.

The number of people or households affected by road constructions can be estimated as follows:

- KTlockartorpsleden: 2,500 households = 5,800 people = 4,400 adults.

- Osbyholm bypass: 14 households.

- Säterivägen: 3,700 households = 8,000 adults.

Unfortunately it is not possible to draw up any estimates for Söderleden and Gillbergaleden.

The above mentioned estimates enable the follow-ing attempts at appraisfollow-ing the encroachment costs of road constructions (cost level 1987-88).

- KTlockartorpsleden as in A above (lump sum): 464 * 2.500 = 1,160,000 SEK as in B above (annual cost): 372 * 4.400 = 1,636,800 SEK as in C above (annual cost): 376 * 4.400 = 1,654,400 SEK - Osbyholm bypass

as in A above (lump sum): 22.400 * 14 = 313,600 SEK - Säterivägen

as in B above (annual cost): 371 * 8,000 = 2,968,000 SEK as in C above (annual cost): 526 * 8,000 = 4,208,000 SEK

What is strange about the attempts above is that the encroachment costs for Klockartorpsleden are greater

22

when expressed as an annual amount than when ex-pressed as a Jump sum. This is of course absurd and proves that the CVM"©s questioning technique needs to be further developed if it is to win general acceptance.

4.1 Spread of willingness to pay

The spread of willingness to pay is of course very great. However, generally speaking, it is possible to say that the average value lies around 400-500 SEK. This is ir-respective of whether the declared willingness to pay is in the form of a Jump sum, an annual amount, a per-sonal amount or a household amount, or whether it is a freely chosen amount or is selected from a pre-printed scale. This proves that the method needs further devel-opment and testing .

The proportion of zero-offers is 50% or more when the amount is freely chosen. If the amount is selected from a pre-printed scale, then the proportion of zero-offers falls to 35-40%. It must, however, be pointed out that people who write comments about being opposed to the particular road also make zero-offers. This incon-sistency must be due either to the fact that the respond-ent has misunderstood the reasoning in some way, or because there is a resentment to the CV method.

The stated maximum willingness to pay usually lies between 5,000 and 10,000 SEK. The exceptions are the special cases of Ljungskile and Osbyholm which dem-onstrated a remarkably high willingness to pay. In these cases however, it is not primarily a question of encroach-ment on rambling areas, but rather a question of gen-eral damage to the local environment.

Generalising in very broad terms, it is possible to say that those who demonstrate the greatest willingness to pay are women, young people and families with chil-dren.

The figure below shows the spread of willingness to pay for Säterivägen.

of a Willingness to pay in Säterivägen study 607

--- Annual, personal amount,

/-52 freely chosen

50

-- -- --Annual, personal amount, 40-

(40

pre-printed alternatives

h

--Average value: 371 Max: 5000

30 4k

--- Average value: 526

-Max: 5000

20414

1041 '

0

0

500

1000 1500 2000

Figure 1

Spread ofwillingness to pay in Säterivägen study.

5 Municipal referendums concerning road projects and

"for or against" studies

Two referendums have been held in Sweden concerning controversial road constructions: Vallaleden in Linköping in 1989 and Västerleden on Ekerö in 1991. 74% of those taking part in the referendums rejected the roads in both cases. VTT carried out an analysis of the Vallaleden ref-erendum in 1989-90.

In addition, a **for or against" study of Broleden in Vänesborg was carried out during the period from 1992-93. It is possible to interpret this study as an attempt at appraising encroachment costs using non-monetary values in terms of reduced sacrifices on the part of road-users, in contrast to the CVM studies referred to above.

5.1 Vallaleden [the Valla link] in Linköping Vallaleden has not been built and is now no longer on the drawing board. This happened after the municipal referendum which resulted in a clear majority for op-ponents to the road.

The link had been intended to form a 1.6 km long section of an outer ring and would have stretched through Vallaskogen [the Valla Forest], which is a well-frequented rambling area right outside the central parts of Linköping. Vallaskogen is criss-crossed by several pedestrian and cycle paths. On one side of the forest lies Valla recreation ground which has a mini zoo, a play-ground, a miniature golf course and a riding-school; on the other side lies Gamla Linköping which has an out-door museum with homes from the turn of the century. Traffic on the road would probably not have dis-turbed any residents since there are no houses or blocks of flats in the vicinity of where the road was intended to be.

In the campaign that was conducted prior to the referendum, supporters of the road argued that it should be built in a rock tunnel through the most frequented part of the forest (1/3 of the total length of the link). However, it was planned to build the link in a sunken, open shaft.

As early as 1955 an outline diagram for a Valla link was made by a traffic consultant. In 1972 an inquiry stipulated that, of eight different alternatives, Vallaleden was the most preferable.

Despite growing public opinion, the municipal coun-cil in 1978 decided to apply for state subsidy for what

24

was known as the Southwest link. This comprised stage 1, the South link, and stage 2, the West link (Vallaleden). The National Road Administration announced that there would be a state subsidy provided that both stages were built.

Two different tunnel proposals were put forward, comprising a third of Vallaleden; a rock tunnel and a concrete tunnel. The rock tunnel was to be blasted through the bedrock and the concrete tunnel involved the covering of a shaft with a roof. In 1984 an associa-tion called "Save Valla Forest" was formed.

The South link was built and opened for traffic in 1988. Public debate on Vallaleden flared up again. Poli-ticians could not agree on the issue. Finally the munici-pal council decided to carry out a local referendum on the road. This was held in April 1989 and those entitled to vote were residents in the municipality aged 18 and above. 49.5% of these participated in the referendum, 25.7% of them voted in favour of the road, 73.5% voted against it and 0.8% voted blank or handed in void bal-lot-papers.

A couple of months after the referendum, VTI con-ducted a questionnaire inquiry to find out which groups had voted in favour of and which had voted against Vallaleden.

477 of the 698 questionnaires sent out were filled in, which is a response frequency of 68%. 32.4% of re-spondents stated that they had not taken part in the Vallaled referendum, 15.6% stated that they had voted in favour and 51.2% stated that they had voted against (0.8% stated that they had voted blank). Thus the study showed a clear under representation of those who had not voted compared with the actual percentual share of 50.5%. Non-participants in the referendum also seemed to show less interest in taking part in the study.

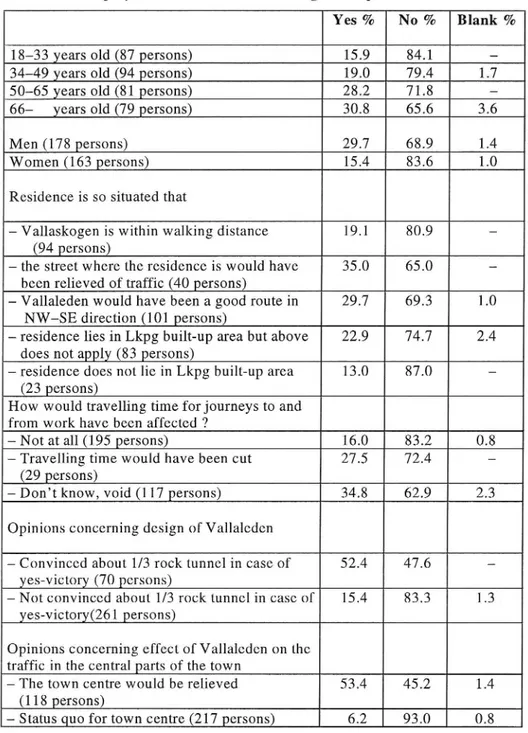

The intention was to establish how people had voted in different strata. This is shown in Table 3 and the responses from the 341 respondents who stated that they had taken part in the referendum form the basis of the table. In the last two groups, the number of responses is fewer than 341. This is due to the fact that some did not reply to the question concerning what they thought about the design of Vallaleden and the road's effect on traffic in the central parts of the town.

Table 3 Inquiry results. Vallaleden, excluding non-respondents.

Yes % No % Blank %

18-33 years old (87 persons) 15.9 84.1

-34-49 years old (94 persons) 19.0 79.4 1.7

50-65 years old (81 persons) 28.2 71.8

-66- years old (79 persons) 30.8 65.6 3.6

Men (178 persons) 29.7 68.9 1.4

Women (163 persons) 15.4 83.6 1.0

Residence is so situated that

- Vallaskogen is within walking distance 19.1 80.9 -(94 persons)

- the street where the residence is would have 35.0 65.0 -been relieved of traffic (40 persons)

- Vallaleden would have been a good route in 29.7 69.3 1.0 NW-SE direction (101 persons)

- residence lies in Lkpg built-up area but above 22.9 74.7 2.4 does not apply (83 persons)

- residence does not lie in Lkpg built-up area 13.0 87.0 -(23 persons)

How would travelling time for journeys to and from work have been affected ?

- Not at all (195 persons) 16.0 83.2 0.8

- Travelling time would have been cut 27.5 72.4 -(29 persons)

- Don't know, void (117 persons) 34.8 62.9 2.3

Opinions concerning design of Vallaleden

- Convinced about 1/3 rock tunnel in case of 52.4 47.6 -yes-victory (70 persons)

- Not convinced about 1/3 rock tunnel in case of 15.4 83.3 1.3 yes-victory(261 persons)

Opinions concerning effect of Vallaleden on the traffic in the central parts of the town

- The town centre would be relieved 53.4 45.2 1.4 (118 persons)

- Status quo for town centre (217 persons) 6.2 93.0 0.8

As can be seen, the subdivisions in the table above have partly been made on an objective basis (age, gender, location of residence, change in travelling time) and partly on a subjective one (opinions about design of the road, opinions about the road as a traffic reliever).

As is evident in the table, yes-respondents form a slight majority amongst those who were convinced that a third of the road should have been built in a tunnel, and likewise amongst those who were of the opinion that the road would have relieved the traffic in the central parts of the town. However, these groups were relatively small; 21% and 35% respectively of the total number of respondents .

However, these yes-majorities invite speculation. The yes side claimed with certainty in their campaign, that a third of the road should be built in a rock tunnel.

Obvi-VT] MEDDELANDE 73 44A

ously they succeeded in persuading very few of this. What would have been the outcome, if they had suc-ceeded in convincing the majority that the design of Vallaleden would be just the one proposed? Perhaps, the result of the referendum would have been quite differ-ent.

A traffic prognosis from the city planning office showed that Vallaleden would have meant that the traf-fic on the streets in central parts of the town would have been reduced by on average five per cent. A slight ma-jority of those believing this were in favour of the road. If more people had been convinced of this, it too would probably have meant a different result.

As can be seen, all other groupings show a clear majority for the no side. It is worth noting that the great-est opposition to the road was to be found amongst

young people and women. This is no great surprise since it is just young people and women, generally speaking, who are regarded as being more environmentally aware than older people and men.

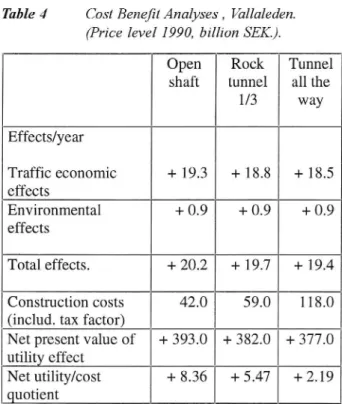

5.1.1 Theoretical discussion about the profit-ability of Vallaleden

According to the Cost Benefit Analysis, Vallaleden should have been an extremely profitable investment. The cal-culations we made prior to the referendum show this. The Cost Benefit Analysis the National Road Administration carried out in the early 19805, also showed good profitability but in this analysis Vallaleden was only the one half of what was known as the South-west link (the remaining half was opened for traffic in

1988).

As has already been mentioned, it was not completely clear how Vallaleden was to have been designed. A sunken and open shaft was the design that had been planned for, but a rock tunnel under the most frequented part of Vallaskogen - a third of the total length of the road - was the design the yes-campaign argued for. That the entire road should be built in a tunnel was never an alternative in the debate, but we also made an appraisal for such a design. The various Cost Benefit Analyses are shown in the table below.

Table 4 Cost Benefit Analyses , Vallaleden. (Price level 1990, billion SEK.).

Open Rock Tunnel shaft tunnel all the

1/3 way Effects/year Traffic economic +193 +18.8 +18.5 effects Environmental + 0.9 + 0.9 + 0.9 effects Total effects. + 20.2 +19.7 +19.4 Construction costs 42.0 59.0 118.0 (includ. tax factor)

Net present value of +393.0 +382.0 + 377.0 utility effect

Net utility/cost + 8.36 +5.47 +2.19 quotient

Net utility/cost quotient (also designated net value quotient) is the current measurement of profitability. It is obtained by subtracting the construction costs from the present value of the utility effects and then dividing the difference by the construction costs. As can be seen,

26

all three variants of Vallaleden would have been profit-able. It should be pointed out that construction costs of 118 million SEK for building the entire road in a tunnel is our own guesstimate. In all three cases travelling time gains account for 13.9 million SEK of the traffic eco-nomic effects.

Despite the fact that, according to the National Road Administration's appraisal methods, Vallaleden would have been very profitable, the great majority of the public rejected it. What is more, this was done by a public which must be regarded as having been well informed thanks to the intensive campaigning that preceded the referendum. In this case theory squares poorly with practice.

An additional factor is that Vallaleden would not have cost the municipality of Linköping anything. This is because the state subsidy the municipality would have received for the Southwest link would only have been granted if the entire stretch, that is to say Vallaleden too, had been built. They failed to secure this. 70% of the respondents to our questionnaire stated that they were at the least somewhat aware of this.

So, a majority of those voting were of the opinion that the positive effects of the road would not compen-sate for the encroachment that it would have caused. In this case we can ignore the construction costs, since the road would have been free for the municipality and thus for its taxpayers too. This means that the encroach-ment costs would have exceeded the estimated 20 mil-lion SEK annually in positive effects that would have been brought about by the link.

5.2 [the Bro link] in Vänersborg Broleden was intended as a link to the existing and planned settlement on Onsjö in the south of Vänersborg. A nature reserve was set aside for the road in Väners-borg 's municipal general plan 90 (dated March 1990). Following severe criticism from among others, the So-ciety for the Conservation of Nature and residents in the vicinity, it was taken off the drawing board in Septem-ber 1990. Critics were of the opinion that it would mean the loss of rambling areas and areas of natural interest. People were also critical of the high-level bridge the road was to cross over Karls Grav canal.

The road was to have stretched through areas of varied forest and meadowland, which are frequently used by ramblers. Quite a significant number of houses in the housing areas of Onsjö and Mariedal would have ended up some twenty or thirty metres from Broleden if it had been built.

Our questionnaire on the link was sent to 602 peo-ple. 464 replied (after it had been sent three times) which is a response rate of 77%. The main question in this *for

or against study" was whether people thought that Bro-leden should be built or not.

The responses to this question were distributed as follows:

- Yes 15.7 %

- No 49.0 %

- No opinion 35.3 %

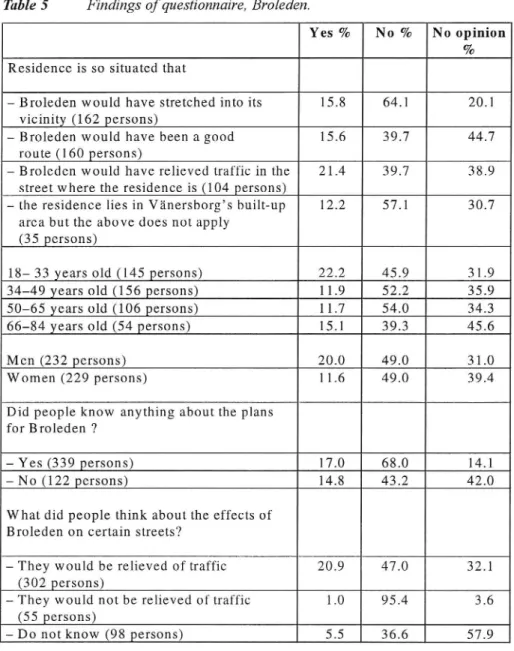

The results that follow here in Table 5 were subdivided into different strata. Three of the questionnaires were incorrectly filled in so the table is based on 461 ques-tionnaires.

As can be seen in the table, no group showed a ma-jority for Broleden. It received the greatest support from residents in streets that the road was intended to relieve

of traffic, from the youngest age group, from men and from those who believed it would have relieved certain streets of traffic. Approximately a fifth of Broleden sup-porters was made up of these strata. That the greatest support was to be found amongst the young must be regarded as surprising. Young people are usually the strongest opponents of roads of this kind.

Knowledge of the plans seems to entail strong re-sistance to the road. 68% of these respondents were against it. To a large extent, those who had no knowl-edge of the plans did not have an opinion about it.

Women were, to a lesser extent than men, in favour of the road. However as can be seen, the proportion of opponents was just as large. Instead, fewer women than men, had an opinion concerning the road.

Table 5 Findings of questionnaire, Broleden.

Yes % No % |No opinion % Residence is so situated that

- Broleden would have stretched into its 15.8 64.1 20.1 vicinity (162 persons)

- Broleden would have been a good 15.6 39.7 44.7 route (160 persons)

- Broleden would have relieved traffic in the 21.4 39.7 38.9 street where the residence is (104 persons)

- the residence lies in Vänersborg*'s built-up 12.2 57.1 30.7 area but the above does not apply

(35 persons)

18-33 years old (145 persons) 22.4 45.9 31.9

34-49 years old (156 persons) 11.9 52.2 35.9

50-65 years old (106 persons) 11.7 54.0 34.3

66-84 years old (54 persons) 15.1 39.3 45.6

Men (232 persons) 20.0 49.0 31.0

Women (229 persons) 11.6 49.0 39.4

Did people know anything about the plans for Broleden ?

-Yes (339 persons) 17.0 68.0 14.1

- No (122 persons) 14.8 43.2 42.0

W hat did people think about the effects of Broleden on certain streets?

- They would be relieved of traffic 20.9 47.0 32.1 (302 persons)

- They would not be relieved of traffic 1.0 95.4 3.6 (55 persons)

- Do not know (98 persons) 5.5 36.6 57,9

6 Conclusions

The results of the encroachment studies shown here demonstrate that there can be major negative environ-mental effects that are not caught in today's appraisal models. At least two of the road construction projects, Säterivägen and Vallaleden, gave proof of good economic profitability according to The National Road Administration 's Cost Benefit Analysis. In spite of this, the public vehemently opposed the construction of these roads.

There seem to be contradictions between the traffic economic appraisal on the one hand, and public percep-tion of encroachment on the other.

The conclusion to be drawn from this should be that there is a need to supplement the road impact assess-ments that are carried out today. Both the CV method and "for or against" studies are suitable supplements.

28

However, one must be aware of the problems entailed in the methods. For example, is it possible to get a per-son in a CVM study to state his/her "true" willingness to pay when the discussion is in any case hypothetical ? Is it possible that a representative person in a **for or against" study is so well informed that one can consider his/her opinion for or against the road in question valid? It 15 impossible to give an unambiguous answer to these questions. By describing a situation as accurately and realistically as possible, one can get the respondent to understand the situation and even feel motivated enough to answer.

However, more refined studies must be carried out. Once this has been done, it will be possible to draw more far-reaching and general conclusions and develop ap-praisal methods.

i References

Bovy, P. and Bradley, M.: Route choice analyzed with Stated Preference approaches. Transportation Re-search Record 1037, p. 11-20. 1985.

Cummings, R.D. et al.: Valuing environmental goods: An assessment of the contingent valuation method. Roman & Allanheld. 1986.

Grudemo, S.: CVM-studie av intrång i rekrea-tionsområde - fallstudie Klockartorps-leden i Västerås. VTI Notat T 29. Statens väg- och transportforskningsinstitut. Linköping. 1988. Grudemo, S.: CVM-studie av intrång i

rekreations-och naturområde - fallstudie Säterivägen i Mölnlycke. VTI Notat T 47. Statens väg- och transportforskningsinstitut. Linköping. 1988. Grudemo, S.: Förbifart Osbyholm (CVM-studie).

Arbetspapper. Statens väg- och transportforsk-ningsinstitut. Linköping. 1987.

Grudemo, S.: Folkomröstningen om Vallaleden -analys av valresultatet beträffande ett omstritt vägprojekt i Linköping. VTI Meddelande 613. Statens väg- och transportforskningsinstitut. Linköping. 1990.

Grudemo, S.: Ortsbefolkningens inställning till ny väg för lokaltrafik genom strövområden -fallstudie Broleden i Vänersborg. VTI Meddelande 714. Statens väg- och transportforskningsintitut. Linköping. 1993.

VT] MEDDELANDE 7344 A

Korn, D.: Mölnlyckeboken. 1983.

Landell, E. and Smith, S.: Miljökostnader av väginvesteringar - en metodstudie. Examens-arbete. Ekonomilinjen T7. Universitetet i Linköping. 1988.

San Francisco Chronicle, Tuesday, February 9, 1993. Statens Vägverk: Promemoria avseende alternativa

sträckningar och utformningar av E18 i Västerås på delen Folkets Park - Hälla. 1977.

StatensVägverk, VFM: Utredningsplan väg E66, delen vid Osbyholm. 1981.

Söderbaum, P.: Tillämpning av positionsanalys vid transportplanering - Exemplet Kungsängsleden i Uppsala. Rapport nr. 86. Institutionen för ekonomi och statistik. Lantbrukshögskolan. 1976.

The Economist, August 17th, 1991. Transportation Volume 21, No 2 May 1994.

Trouvé, J. and Jansson, J.O.: Värdering av miljökost-nader av en ny väg - en fallstudie av planerad motorväg på vägbank över Ljungskileviken. VTI Notat T 07. Statens väg- och transportforsk-ningsintitut. Linköping. 1987.

Widlert, S.: Stated Preferences - Ett sätt att skatta värderingar och beteende. KTH. Trafikplanering. Transek. 1992.

Appendix 1 Page 1(1)

Map: E6 Ljungskile

...

Alternative selected: West 1A f""""'"

p

%* i

f gt

ed tl

SUNETI

X, . » # 2 u l l l n l u n g s k 44 a no m S e t t l e m e n t 1 j inet. 3 oå lé '.: i fl å! " U L >pågå. H " % # 5 Q & fås = 2 O el: © $ eh SPD-o i a E

4;

P = -m

0

-%.

# gÅ

ad

o "2

år

v ? 3

1

- 8 8 E

8 - &

t

1-2 % >

2

©

ad

Z 4 8 A

H 91

l i'l

4

r

WWWmW%

sf

St

p

1

MEDDELANDE 73 44A

32 VTT MEDDELANDE 744 A * . ] ? ! 3 å i b S a t I r å gx X N 57 1? w a "No R u n n ve rs x r' v " , .. . , , " 4 po ct -, i a! pi .fi p % & i, fö rs t w i ; PN h. , Sa . ? :? . Bl ä ' . NP te y Map | e | i T/k eG Fa n b u dOm s 1 "t a. f J" " H4, i ju (the Gillberga

li

i

Gillbergaleden nl E f " u f T_ k Nöje :; lif -"' i:I tt f 2&l n u u b u r A i ät i i * 3 ht an #* lt em e * X 3 4 4 2 T 00 % % -Å 4 u + o -; åk .-i. Lung by t V a m f P hv "M e r eat. 20-4 2" i J T Y % ; 3 å & 7 ', Ske llp *, n u " ?f ut o 5 r -fS kr T G * 4 i , g 8 s ; ; * 7 E il l % 4 i 41 % ;$ sfl uns byu tte ne:%

&

-S

-Q m w äy x x b c utal ka nu " K U. f o m b m g " Z j / q m d m , 21 3 "g 0 Ko is tu be rg et : +-0 = st i 2 sk & I e l e m m & R e x q 9 ? ( Ä n n u an d: G. .-.: : es Åp å -Hc mlyy qd wm i medlen # Authorization code: 94.0346Public map material from surveyor's office |

o & S u l p Q L åS ?r vj nh ru l d M L sta Gy + hrfu , 361, Q H m ät te r * X A n t k ' l ' du m l 1 r x f w t "l a bra t i3 & I, & % % ( % [L BB T f X i -al i , P C VS o s Z ' S e *" . N x rep sl ulad uz mr hn o X "R )( .1 ad; d 70. # = = M a t LT p]1 0 k ot .. ed a _ fS o _.-y . i ti ' ' $ ? & ( ; x > i .. ,. _, l . 2? L : : |) a I 2 , ' & 7 .. . :' -, + ' '.: 'I! W u _. .' .-. '| ' nu ll ;. .-S Z p e (8 S O S se ; NF t? ' * Appendix 2 Page 1(1)

VT 1 M ED D E LAND E 7 4 4 A 33 Authorization code: 94.0346 P%) s e s Hö rb yån sg o ss +69 0 office /

Public map material from surveyor's