Leveraging External Sources of Innovation with

the Application of Collaborative Software Tools

- The case of SMEs

MASTER THESIS WITHIN Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS 30

PROGRAMME OF STUDY Digital Business, Strategic Entrepreneurship AUTHORS Fanny Nilsson & Jennifer Sturedahl

Acknowledgments

This research would not have been made possible without the guidance, participation, and support from certain individuals who deserve immense appreciation.

First and foremost, we would like to express our highest gratitude and appreciation to our supervisor, Ph. D. Henry Lopez-Vega, who has supported us with valuable insights and exceptional guidance throughout the entire research process, especially during our four enriching

seminars. A thank you also goes to our peers in the seminar group who provided support throughout the last months which gave us extra motivation. Most of all, we enjoyed the cheerful

atmosphere and the space we were given to realize our research ideas and ambitions. This thesis would of course not have been possible to perform without our participants. Therefore, we would like to thank all our interviewees who dedicated their time and energy to

participate in our study. We especially thank them for sharing their personal experiences and deep insights into their unique innovation processes. They made it easy for us to become curious

about this research topic through the engaging way they shared their insights.

A final thank you goes out to Anders Melander and Leona Achtenhagen, Professors at Jönköping International Business School, for giving us advice and always being available for consultation

from the very beginning to end.

Finally, we want to highlight that classmates and fellow students have turned into very close friends and contributed to an exciting, enriching, and instructive time of our lives over the last two years. We bring invaluable memories with us from Jönköping International Business School.

______________________ ______________________ Fanny Nilsson Jennifer Sturedahl

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Leveraging External Sources of Innovation with the Application of Collaborative Software Tools – The Case of SMEs

Authors: Fanny Nilsson and Jennifer Sturedahl Tutor: Henry Lopez-Vega

Date: 2021-05-24

Key terms: Innovation, external sources of innovation, digital tools, collaborative software tools, SMEs

Abstract

Background – Leveraging external sources of innovation (ESI) is found to be vital for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) innovation work as they commonly suffer from a lack of resources to facilitate and execute this work. The interaction with the external environment does, in turn, enable access to knowledge and capabilities that SMEs currently not possess. Moreover, as collaborative software tools (CSTs) have proven to play a critical role in today’s innovation processes and have transformed the way of interacting with the external environment, it becomes obvious that research in this field must account for the usage of these tools. CSTs have a significant impact on communication, cooperation, and coordination and are, therefore, widely used to facilitate collaborations in intra-organizational groups. Thus, these tools can be beneficial for SMEs as it provides them with greater access and availability to the external environment.

Purpose – This research aims to understand how SMEs can leverage external sources of innovation with the application of collaborative software tools and develop fruitful insights that can be used to facilitate innovation work for SMEs that typically lack internal resources.

Method – This study approaches the underlying philosophy of a relativist ontology, a social constructionist epistemology, and iterative grounded theory. For the methodology, empirical data was collected through 31 semi-structured interviews with participants from SMEs and their ESI in

the region of Jönköping County following a purposive sampling method. The empirical data was further analyzed by conducting a grounded theory strategy for process analysis.

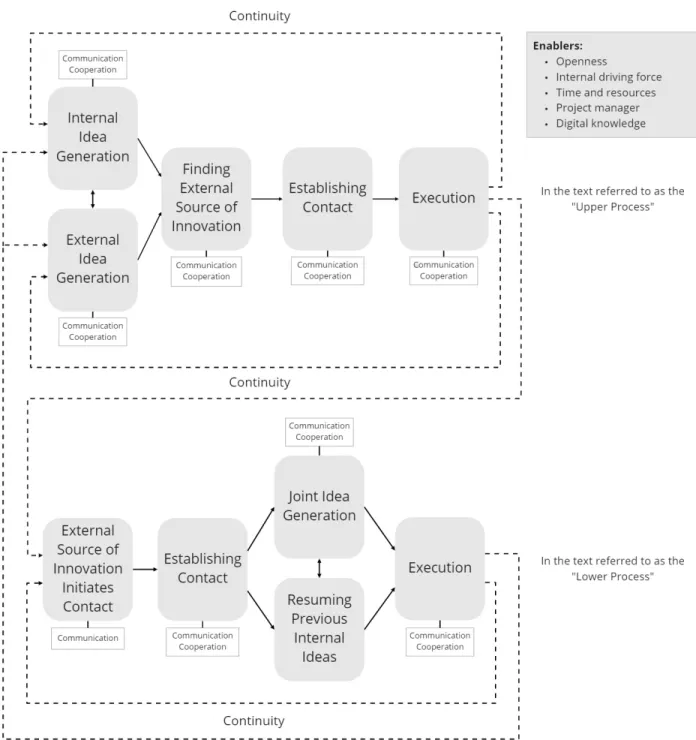

Findings – We develop two processes illustrating how SMEs can leverage ESI with the application of CSTs. It was found that the application of CSTs in these processes enables SMEs to explore, acquire, and utilize information and knowledge from ESI in ways that previously have not been possible. By providing new ways of communicating and cooperating, CSTs facilitate the activity of sourcing knowledge and resources from ESI. Consequently, the SMEs are provided with new knowledge and resources that, in turn, improve and enhance the development of innovations. Thereby we contribute to an understanding of how SMEs can leverage ESI in the 21st century.

Definitions

CSTs Interaction mechanisms facilitating user interactions. (Collaborative Software Tools) Examples: e-mails, direct messaging, digital voicemail applications, video calls, document-sharing, shared digital whiteboards, shared applications, e-calendars, and project management and workflow systems.

Digital tools Enable the information underlying innovation activities to be digitized, and the sources and ways from which ideas develop and through which concepts emerge to be captured.

ESI Local, national, or international customers, users,

(External Sources of Innovation) suppliers, competitors, consultants, universities, research institutes, trade organizations, or personal networks that a firm has direct interaction with to orient innovation efforts.

Inbound open innovation Internal use of external knowledge to innovate.

Innovation The introduction of something new.

Open innovation Intentional inflows and outflows of knowledge in a firm that aims to generate or spread innovations. Process A series of events, activities, and choices occurring

over time.

SMEs Firms with less than 250 employees and up to 50 (Small and Medium-sized Enterprises) million EUR in turnover.

Table of Contents

1 Introduction ... 1 1.1 Background Information ... 1 1.2 Problem Discussion ... 2 1.3 Research Purpose ... 3 1.4 Delimitations ... 4 2 Frame of Reference ... 5 2.1 Literature Collection ... 5 2.2 Literature Review ... 6 2.2.1 Innovation ... 62.2.2 External Sources of Innovation ... 6

2.2.2.1 Obtaining Innovations from External Sources ... 8

2.2.2.2 Integrating External Sources of Innovation ... 9

2.2.2.3 Commercializing Innovations ... 9

2.2.2.4 Interaction Phase ... 10

2.2.3 The Impact of Digital Tools ... 11

2.2.3.1 The 3C Model and Collaborative Software Tools ... 12

2.3 Interconnections Between Fields of Research ... 15

3 Methodology ... 15 3.1 Research Philosophy ... 15 3.2 Research Design ... 17 3.3 Research Approach ... 18 3.4 Method ... 19 3.4.1 Data Collection ... 19 3.4.1.1 Semi-structured Interviews ... 20 3.4.1.2 Sample Selection ... 21 3.4.1.3 Interview Design ... 22 3.4.2 Data Analysis ... 24 3.5 Research Ethics ... 29 3.6 Research Quality ... 31

3.6.1 Credibility ... 31 3.6.2 Transferability ... 32 3.6.3 Dependability ... 32 3.6.4 Confirmability ... 33 4 Empirical Findings ... 34 4.1 Overview ... 36 4.2 Enablers ... 40

4.3 Idea and Demand Generation ... 45

4.4 Finding External Sources of Innovation ... 52

4.5 Establishing Contact ... 56

4.6 Execution ... 61

4.7 Continuity ... 70

5 Analysis ... 75

5.1 Leveraging External Sources of Innovation ... 75

5.2 The Application of Collaborative Software Tools ... 80

6 Conclusion ... 85

7 Discussion ... 86

7.1 Theoretical Implications ... 86

7.2 Practical Implications ... 87

7.3 Limitations ... 88

7.4 Future Research Recommendations ... 89

Reference List ... 91

Appendices ... 101

Appendix 1 – Literature Table ... 101

Appendix 2 – Interview Guide ... 102

Appendix 3 – Participant Consent ... 105

Figures Figure 1 – 3C Model of Collaborative Software Tools ... 13

Figure 2 – Coding Tree ... 27

Figure 4 – The Process of Leveraging External Sources of Innovation with the Application of Collaborative Software Tools ... 36 Figure 5 – Applied 3C Model of Collaborative Software Tools ... 37 Tables

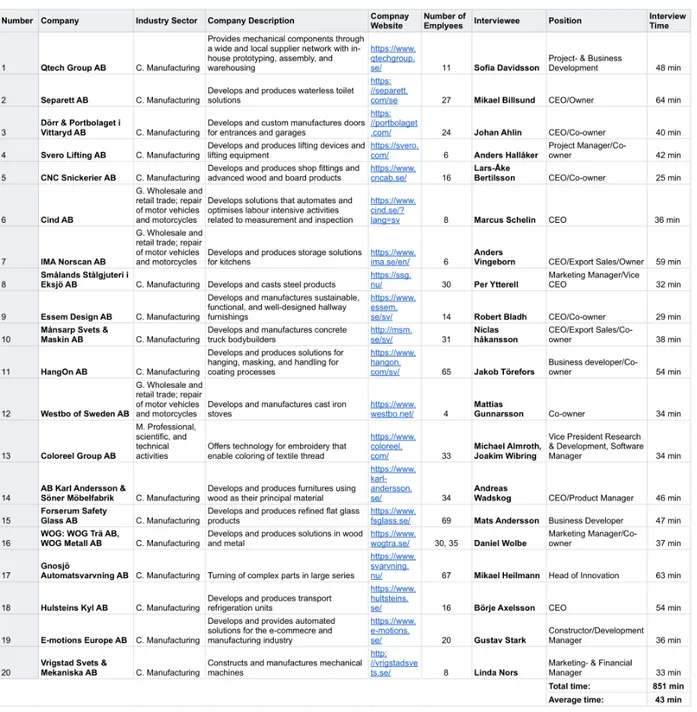

Table 1 – Participants: Company Representatives ... 23 Table 2 – Participants: External to the SMEs ... 24 Table 3 – Theme Statements ... 35

1

1 Introduction

This chapter begins with an introduction to the background of the current research on external sources of innovation and collaborative software tools in relation to SMEs. This is followed by a presentation of the problem discussion and research purpose to create an overall understanding of the research. Lastly, delimitations are presented.

1.1 Background Information

In today’s constantly changing environment with advancements in technology, shifts in consumer preferences, and growing competition, firms are increasingly concerned with how they must act on the opportunities and challenges arising (Kotter, 2014; Morris et al., 2011). One way for organizations to survive in this fast-paced environment is to continuously innovate (Morris et al., 2011). Innovation is defined as the introduction of something new (Merriam-Webster, 2021; Morris et al., 2011). Still, organizing for continuous innovation is highly challenging in an environment characterized by continual change (Garud et al., 2013). This forces firms to rethink, redesign, and cross the existing boundaries of their organization (Morris et al., 2011). Hence, companies increasingly face the tension of depending on external sources to complement their internal resources for creating innovation outputs. This is especially true for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), as they tend to have limited internal resources to facilitate the development of innovations (Radziwon & Bogers, 2019). Accordingly, leveraging external sources of innovation is vital for firms’ innovation activities (Brunswicker & Vanhaverbeke, 2015; Fakhreddin & Castonguay, 2019; Lasagni, 2012; Lopez-Vega et al., 2016; Nieto & Santamaria, 2007; Rammer et al., 2009; West & Bogers, 2014). As a result, innovation processes are becoming increasingly open (Lasagni, 2012). External sources of innovation (ESI) will in this research be defined as local, national, or international customers, users, suppliers, competitors, consultants, universities, research institutes, trade organizations, or personal networks that a firm has direct interaction with to orient innovation efforts (Brunswicker & Vanhaverbeke, 2015; Lasagni, 2012; Moilanen et al., 2014; Rammer et al., 2009).

2 Open innovation processes have been facilitated by the development of digital tools, as it allows for easier access and sharing of knowledge (Urbinati et al., 2020) and has enabled new interaction possibilities to emerge (Yoo et al., 2012). Digital tools enable the information underlying innovation activities to be digitized, and the sources and ways from which ideas develop and through which concepts emerge to be captured (Orellana, 2017). As SMEs have a lack of internal resources, digital tools can help them to explore and acquire information and knowledge from the external environment. In turn, SMEs that use digital tools will experience an increased collaboration with external actors and hence, better manage their internal resources (Scuotto et al., 2017). Likewise, Brunswicker and Vanhaverbeke (2015) argue innovative firms’ to be those that develop strategic abilities and related digital tools appropriate for integrating and sharing knowledge in intra- and inter-organizational processes.

In this research, digital tools will be viewed from the perspective of collaborative software tools. Collaborative software tools (CSTs) are defined as interaction mechanisms facilitating user interactions and aim to facilitate and handle group work and can be used to communicate, coordinate, share, cooperate, and solve problems. It includes software tools such as e-mails, direct messaging, digital voicemail applications, video conferencing, document-sharing, shared digital whiteboards, shared applications, e-calendars, and project management and workflow systems. Hence, it is widely applied in interactions and collaborations with intra- and inter-organizational teams (MacFadden, 2018). As CSTs have a great impact on how individuals interact in collaborations (MacFadden, 2018), and digital tools are found to benefit external collaborations (Scuotto et al., 2017), it becomes relevant to understand how firms leverage ESI with the application of CSTs.

1.2 Problem Discussion

The leverage of ESI is found to be vital for SMEs’ innovation work as they often suffer from a lack of resources to facilitate and execute this work (Radziwon & Bogers, 2019). Hence, SMEs are continuously forced to search for external resources to complement their internal (Lasagni, 2012; Nieto & Santamaria, 2007). The interaction with the external environment can enable access to knowledge, information, and capabilities that the company does not currently possess (Brunswicker

3 & Vanhaverbeke, 2015; Lasagni, 2012; Nieto & Santamaria, 2007; Rammer et al., 2009), which further drives innovation efforts in SMEs (Lasagni, 2012).

Furthermore, as digital tools have proven to play a critical role in today’s innovation processes and have transformed the way of interacting with the external environment (Agostini et al., 2019; Durmuşoğlu & Barczak, 2011; Ferreira et al., 2019; Nambisan et al., 2019; Marion & Fixon, 2021; Scuotto et al., 2017; Urbinati et al., 2020; Yoo et al., 2012), it becomes obvious that research in this field must account for the usage of such tools. CSTs, specifically, can have a significant impact on teams’ communication, collaboration, and cooperation and are, thus, widely used to facilitate group work in intra- and inter-organizational groups (MacFadden, 2018). Such tools can be beneficial for SMEs as it provides them with greater access and availability to the external environment (Marion & Fixon, 2021; Thissen, 2007). Hence, there is a need to bridge the literature on SMEs, ESI, and CSTs to fill the current research gap. This would allow us to understand how to leverage ESI with the application of CSTs, from the perspective of SMEs. Since research has found that many SMEs lack the ability to purposefully make use of ESI (Brunswicker & Vanhaverbeke, 2015) and CSTs are changing the game of how this activity is performed, this understanding could provide new insights and opportunities for SMEs to leverage ESI in the 21st century.

1.3 Research Purpose

This research aims to fulfill and bridge the existing gap in the literature on ESI and CSTs through the lens of SMEs. This will be done by conducting a qualitative study with the purpose to develop a theoretical understanding of the process of leveraging ESI with the application of CSTs, in the context of SMEs. Consequently, we hope to develop fruitful insights that can be used to facilitate innovation work for SMEs that typically lack internal resources. To make these research efforts tangible, we have formulated the following research question:

RQ: How can SMEs leverage external sources of innovation with the application of collaborative software tools?

4 In the pursuit to answer this question, we conduct an interview-based study where managers from SMEs and individuals that have been externally involved in the SMEs innovation efforts or otherwise have good insights into the SMEs innovation work were interviewed. We chose to interview managers from the selected SMEs as management teams have an overall understanding of their innovation-related processes and are involved in the execution of this work (Lasagni, 2012). Additionally, we chose to include the perspective of the externally involved individuals as it allowed us to gain various perspectives on the same phenomenon. Hence, by choosing to include the perspective of the managers of SMEs and externally involved individuals, it is possible to obtain information on all aspects needed to answer the research question. Furthermore, to fulfill the purpose of understanding the process of leveraging ESI with the application of CSTs, in the context of SMEs, we must first understand what a process is. In this research, a process will be defined as a series of events, activities, and choices occurring over time (Langley, 1999; Van de Ven, 1992).

1.4 Delimitations

This study focuses on SMEs. SMEs were deemed suitable for this study as research has found that SMEs can greatly benefit from external inputs due to their scarce resources (Brunswicker & Vanhaverbeke, 2015; Fakhreddin & Castonguay, 2019; Lasagni, 2012; Radziwon & Bogers, 2019), but many SMEs lack the ability to purposefully make use of ESI (Brunswicker & Vanhaverbeke, 2015). Hence, as the application of CSTs can facilitate inter-organizational group work (MacFadden, 2018), understanding the process of leveraging ESI with the application of CSTs could potentially have a great impact on SMEs and their innovation processes. To achieve the most valuable and incisive results within our time frame, resources, and network, we have made some conscious decisions regarding this study’s delimitations in relation to the research scope. Our study has been limited to SMEs in the region of Jönköpings County and a total of 30 participants. More specifically, the participants include 21 managers involved in innovation and development activities at firms classified as SMEs in the region of Jönköping County and nine external individuals that have been involved in innovation efforts with one or more of the selected SMEs or have good insights into the SMEs innovation work. Moreover, digital tools were limited to CSTs. The reasoning behind these choices was to narrow down the scope of the research since the topic is extensive in nature. Still, the

5 need for increased awareness of how firms can leverage ESI with the application of digital tools apply to firms in all different industries and sizes, and for various digital tools. Consequently, this research could be executed from other and different perspectives.

Furthermore, in our literature review, we begin by demonstrating digital tools' possible effects on innovation and related processes. Since digital tools are a broad concept, we delimit digital tools to CSTs. By applying the 3C Model to CSTs, we categorize CSTs into the three categories of communication, cooperation, and coordination. Even though CSTs can be divided into different categories, we examine CSTs as captured in the 3C model, and thus, the literature studied in our literature review does not focus on the topics of communication tools, cooperation tools, and coordination tools separately. Consequently, we do not include literature about each topic respectively. Also, we acknowledge that researchers have used various terminologies to describe CSTs. For example, Marion and Fixon (2021) refer to CSTs as Collaborative Information Technology whereas Thissen et al. (2007) group CSTs under the name of Communication Tools.

2 Frame of Reference

This section examines the current state of the literature concerning the phenomena under study. The process of the literature collection is described along with a literature review of relevant topics, including innovation, ESI, and CSTs.

2.1 Literature Collection

This study combines various fields of literature and the research question emerged from the interconnections between ESI and CSTs. To obtain relevant peer-reviewed scholars, understand the current state of the topic, and systematically approach the research problem, the database Google Scholar was used to perform searches for scientific evidence. Specifically, the academic articles were found by combining search words such as “Innovation”, “External sources”, “SME”, “Digital Tools”, and ”Collaborative Software Tools”. The literature review aims to discuss, assess, and compare previous definitions and theories within the topic as a fundamental grounding of the empirical part of

6 the paper. To assure high quality for our research, we also took advantage of the scholars citing the articles we considered as most relevant, which brought us further appropriate articles around the phenomenon. Moreover, while reading and reviewing the articles, we created an Excel sheet with relevant parts and subtopics to recognize relevant themes and keywords. After identifying the most appropriate themes, the process of finding consistent and contradicting perspectives from academic scholars was highly facilitated. Also, the review questions developed by Wallace and Wray (2016) were used to examine the credibility and relevance and determine the purpose of the study. After a careful analysis of the literature, we ended up with 27 articles. An overview of the selected literature can be found in Appendix 1.

2.2 Literature Review

2.2.1 InnovationOriginally, innovation was related to the activities of research and development (R&D) but has in the last years been associated with the knowledge used in the process of creating and generating new ideas (Lasagni, 2012). Scholars agree that innovation outputs benefit from the presence of relationships, networks, alliances, and other forms of contacts with external parties (Brunswicker & Vanhaverbeke, 2015; Fakhreddin & Castonguay, 2019; Lasagni, 2012; Nieto & Santamaria, 2007; Rammer et al., 2009; West & Bogers, 2014). Consequently, many firms have started to embrace the internal use of external knowledge to innovate by leveraging ESI. This is referred to as one form of open innovation (Lasagni, 2012), called inbound open innovation (Dahlander & Gann, 2010; Fakhreddine & Castonguay, 2019; Urbinati et al., 2020). The term open innovation is more broadly defined to explain all intentional inflows and outflows of knowledge in an organization that aims to generate or spread innovations (Dahlander & Gann, 2010; Inauen & Schenker-Wicki, 2011). Further, the leverage of ESI is found as a key driver for innovation success in SMEs (Lasagni, 2012).

2.2.2 External Sources of Innovation

Leveraging ESI is the activity of obtaining knowledge and information from outside the organization, contributing to an organization’s innovation outputs (Fakhreddin & Castonguay, 2019; West & Bogers, 2014). Knowledge and information can be sourced from a variety of actors. In this study, it

7 will be defined as direct interaction with local, national, or international customers, users, suppliers, competitors, consultants, universities, research institutes, trade organizations, or personal networks to orient innovation efforts (Brunswicker & Vanhaverbeke, 2015; Lasagni, 2012; Moilanen et al., 2014; Rammer et al., 2009). Research has shown that these types of activities drive innovation and build a reputation (Brunswicker & Vanhaverbeke, 2015; Lasagni, 2012). It also increases the likelihood of achieving innovation success and thereby increases the success of launching innovations, the amount of financial value that can be generated from innovations, and the degree of novelty of the innovations (Brunswicker & Vanhaverbeke, 2015; Lasagni, 2012; Nieto & Santamaria, 2007; Rammer et al., 2009). Moreover, it enables organizations to access knowledge and capabilities which they previously lacked (Dahlander & Gann, 2010; Brunswicker & Vanhaverbeke, 2015; Lasagni, 2012; West & Bogers, 2014) and minimize risks associated with innovation (Lasagni, 2012). West and Bogers (2014) further explain improved efficiency through economies of scale to be a motivator for external knowledge sourcing. Yet, the sharing of information, which may be necessary for collaborations with external partners, also entails certain risks as information spreads outside the boundaries of the organization (West & Bogers, 2014).

Having diversity in the collaborative network is found to favor innovation novelty. A heterogeneous network will provide firms access to diverse knowledge and information which, in turn, increases the likelihood of achieving more novel innovations (Nieto & Santamaria, 2007). Hence, different ESI are complementary, rather than substitutes to one another (Dahlander & Gann, 2010; Fakhreddine & Castonguay, 2019; Nieto & Santamaria, 2007). This complementary effect is enhanced by interactions with ESI because as the openness to one ESI increases, the openness to another ESI increase as well (Fakhreddine & Castonguay, 2019). Similarly, Lasagni (2012) explains small firms with previous experience of external collaborations to be more capable of developing external connections, suggesting a learning process. In accordance, Nieto and Santamaria (2007) argue that previous experience influences both the organization’s learning of innovation processes and management of collaborative interactions. Creating a path of continuous collaboration, with the same or different partners is, therefore, found to encourage innovation (Fakhreddine & Castonguay, 2019;

8 Lasagni, 2012; Nieto & Santamaria, 2007) and particularly the degree of novelty (Nieto & Santamaria, 2007).

In the next sections, phases identified in the previous literature to be relevant for the leverage of ESI is outlined. This provides an understanding of the related activities that will be further explored in this study in relation to SMEs and the application of CSTs.

2.2.2.1. Obtaining Innovations from External Sources

To be able to leverage ESI, companies must first obtain innovations from external sources. This step requires two actions, namely finding ESI and then acquiring those (West & Bogers, 2014). The choice of ESI will mostly be based on risk and return calculations conducted by the company seeking to interact with external partners (Nieto & Santamaria, 2007). Brunswicker and Vanhaverbeke (2015) identifies five different types of sourcing strategies that are commonly applied by companies, being minimal searcher, supply-chain searcher, technology-oriented searcher, application-oriented searcher, and full-scope searcher. The latter two were found to provide direct performance benefits in terms of the success of launching innovation and the monetary benefit from the innovation. Application-oriented searchers are demand-driven in their searching. Such SMEs regularly interact with customers, suppliers, and network partners. Full-scope searchers aim for a high diversity of external innovation sources. Thus, such SMEs want to access market, technology, and scientific knowledge by interacting with various sources without becoming dependent upon them (Brunswicker & Vanhaverbeke, 2015). Research has found that the larger number of interactions with ESI, the more open will the firms' search strategy be (Dahlander & Gann, 2010). Moreover, the rise of the internet has enabled greater access to external sources. Even though search- and collaboration diversity are found to be positively related to innovation success (Ebersberger & Herstad, 2011), relying on an increasing variety of external sources may yield decreasing returns. Accordingly, firms must try to find the optimal level of search breadth and depth (West & Bogers, 2014).

9 2.2.2.2 Integrating External Sources of Innovation

After having obtained innovations from external sources, they must be integrated into the firm. This step is necessary for companies to be able to profit from ESI (West & Bogers, 2014). Two factors that influence organizations’ ability to integrate innovations are the organizational culture and the level of absorptive capacity (AC). The organizational culture must be developed to allow for external influences, creating a willingness to involve ESI. Yet, more research is necessary for this field (West & Bogers, 2014). Further, AC is said to be required to be able to transform external knowledge inflows into innovations (Fakhreddine & Castonguay, 2019; Moilanen et al., 2014; West & Bogers, 2014). AC is an organization’s ability to identify, assimilate, and exploit information and knowledge from its surroundings. Hence, it affects the organization’s ability to identify and evaluate potential value from relevant ESI (Fakhreddine & Castonguay, 2019; Moilanen et al., 2014). Given the role of AC in facilitating the utilization of ESI, it must be considered. However, research has found it to be less important in non-R&D firms, as external knowledge inflows have a much stronger direct effect on innovation success in such organizations compared to organizations with in-house R&D (Moilanen et al., 2014). Consequently, firms commonly scan the external environment before initiating internal R&D (Dahlander & Gann, 2010). Rammer et al. (2009) argue that non-R&D firms must instead apply human resource management (HRM) tools or teamwork to promote innovation processes. Hence, implying that R&D can be substituted by management practices in SMEs (Rammer et al., 2009). The relevance of AC will, thus, depend on the nature of the firm.

2.2.2.3 Commercializing Innovations

When innovations from external sources have been obtained and integrated, the next step is to commercialize innovations. This step is concerned with value creation and value capture of the innovation that, together with the actual innovation, constitute the organization’s business model. Hence, it does, among other things, explain how the firm makes money from the innovation (West & Bogers, 2014). Yet, Van Hemert et al (2013) found that even though openness towards ESI is applied in the development and production phase of innovations, it is often neglected in the commercialization phase. Still, SMEs can greatly benefit from collaboration in the commercialization process (Van Hemert et al., 2013). However, measuring value creation and value capture can be difficult and various methods for this have been applied in research. In terms of value creation, organizations seek

10 to source knowledge, ideas, technology, market needs, or other information to create value from external innovation sources. In terms of value capture, organizations seek to increase profitability by utilizing ESI, either by reducing costs or increasing prices. Yet, some studies have found relying on ESI to instead decrease profitability, as the cost of involving ESI exceeded the value it created (West & Bogers, 2014).

2.2.2.4 Interaction Phase

A phase that can occur at any step in the leverage of ESI is interaction. Interaction can involve feedback loops, reciprocal interaction with external collaboration partners, and integration with external innovation networks and communities depending on the type of collaboration efforts pursued (West & Bogers, 2014). Nieto and Santamaria (2007) state that regardless of what external innovation source is being used, organizations must sustain a pattern of interaction over time. This will result in the development of a shared understanding and common ways of working together and, therefore, increases the likelihood of utilizing the shared information in the development of innovations. These findings demonstrate the importance of continuity in external collaborations (Nieto & Santamaria, 2007).

Firstly, feedback loops including ESI can be constructed to produce innovation ideas or test innovations in an early stage of development, often by generating market feedback. Secondly, reciprocal interaction involves collaboration between the firms and single or multiple external innovation sources. This type of interaction is often seen in collaborations between the innovating firm and its suppliers, competitors, universities, or other partners. Furthermore, networks with industry firms and firms located in the same geographical area can be utilized as ESI (West & Bogers, 2014). Lasagni (2012) found such networks to facilitate the exchange of resources and enable joint development of new ideas and skills. Consequently, West and Bogers (2014) explain it to be positively related to innovation success. Lastly, firms can engage in open innovation communities, i.e., ongoing voluntary association of individuals or organizations, organized by profit-making organizations. The level of involvement is up to the company to decide, and they must balance the benefits from sharing their internal work against the potential loss of information and control (West

11 & Bogers, 2014). Today, these types of collaborative communities have been facilitated by digitalization (Yoo et al., 2012).

2.2.3 The Impact of Digital Tools

The adoption of digital tools has gained significant attention in today’s contemporary world as it causes major changes for organizations (Agostini et al., 2019; Ferreira et al., 2019; Nambisan et al., 2019; Parviainen et al., 2017; Yoo et al., 2012). The result of digitalization of existing tools for collaboration, and the development of entirely new digital collaboration tools, is a far more major change of innovation than previous tools enabled. The usage of digital tools not only impacts the quality of the output and speed of its generation, but it also impacts the innovation work itself. Digital tools transform collaboration patterns, decision authority, structures, firm boundaries, and work content (Marion & Fixson, 2021). Hence, understanding the benefits and implications of the adoption of digital tools becomes relevant in the context of leveraging ESI.

Companies increasingly utilize digital tools throughout innovation processes to facilitate communication and collaboration among the involved partners (Marion & Fixson, 2021). The usage of digital tools reduces time and costs in the development processes. It can also enhance the efficiency of knowledge creation and transfer among stakeholders (Banker et al., 2006; Marion & Fixson, 2021; Urbinati et al., 2020). As a result, most innovation work increasingly occurs in inter-organizational contexts of actors as inputs are gradually becoming interrelated. Thus, making the innovation processes increasingly open (Agostini et al., 2019). The adoption of digital tools at various phases of innovation processes also contributes to a new level of product effectiveness and new idea management processes (Durmuşoğlu & Barczak, 2011). Yet, executives aiming to leverage digital tools to enhance the deployment of resources during the innovation process need to find and adopt the right digital tools (Agostini et al., 2019).

Moreover, digital tools do not necessarily democratize innovation as they can also have destructive sides and negative influences (Berger et al., 2019; Parviainen et al., 2017). Digital tools are beneficial to some groups, but they can also harm others. Particularly, it might isolate some parties that lack the needed resources or skills to utilize them. Besides, digital tools can result in harmful emotional and

12 psychological reactions, including role conflict and stress among innovators (Berger et al., 2019). Similarly, Nambisan and Baron (2021) highlight that utilizing digital tools can come with additional costs such as in terms of learning and adaptation. It includes learning new capabilities that can support the changes that come with it, especially in terms of resources, internal and external users, and processes. This, in turn, can require a change in habits, routines, and ways of working (Parviainen et al., 2017). Even though an increased usage of digital tools in the innovation processes will demand new sets of resources, it also provides opportunities for developing new relationships, processes, and organizational forms (Urbinati et al., 2020; Yoo et al., 2012).

Digital tools are found to capture collaborations, including interactions between individuals, teams, and external parties, as well as support communication, work coordination, and knowledge creation and sharing (Orellana, 2017). As these aspects of digital tools will be of interest for this research, we chose to narrow down the concept of digital tools to CSTs. Therefore, the collaboration areas of communication, cooperation, and coordination will be further explained by using the 3C model presented in the next section.

2.2.3.1 The 3C Model and Collaborative Software Tools

Collaboration can be referred to as the combination of communication, cooperation, and coordination. This is captured by the 3C model (Figure 1) originally developed by Ellis et al. (1991) with some terminological differences. Communication refers to the exchange of messages and information sharing among parties. Cooperation is the work that takes place in the joint workspace (Fuks et al., 2008). Finally, coordination is the management of individuals internally and externally including their activities and resources. Yet, how people work today has significantly changed with the emergence of the connected society and digital tools (Fuks et al., 2005).

13 Figure 1 - 3C Model of Collaborative Software Tools

Classification of CSTs based on the 3C model. The 3C triangle appears in Borghoff & Schlichter (2000)

The 3C model classify CSTs into three categories. Firstly, communication includes message systems (Fuks et al., 2005), such as e-mails, instant messaging, chats, and shared information space. E-mails allow users to send messages or files. Instant messaging and chat tools have the same functions, but they enable instant interactions where the user can see who is available. Finally, shared information space enables the sharing of information to a group of people with access to the software (Thissen et al., 2007). Secondly, cooperation includes electronic meeting rooms and group editors (Fuks et al., 2005) which enable communication in real-time and the work on the same documents and files simultaneously (Thissen et al., 2007). Finally, coordination includes management systems and workflows (Fuks et al., 2005) which enable sharing calendars, contact lists, and arrange meetings

14 (Thissen et al., 2007). Further, it is found that sharing knowledge by voice, documents, images, and shared optional software which is enabled by communication, cooperation, and coordination tools supports individuals' need for aural, visual, and tactile communication (Thissen et al., 2007). Hence, such tools have seen enormous growth in popularity in the last 15 years (Marion & Fixson, 2021). Even though specific CSTs are argued to support, and thus be classified as, one of the categories, it can also be argued to support the other categories. Hence, the classifications are not exclusive, which can be identified by the CSTs positioning in Figure 1.

Common for all three categories of collaborative software systems is that they reduce the need for traveling (Thissen et al., 2007). Some of the tools also facilitate the reuse of information and knowledge through shared files and stored data. The usage of CSTs can, thus, reduce project cycle times and development costs (Banker et al., 2006). Additionally, it is argued that it is easy to adapt to the tools, especially if the users can influence the choice of CSTs. Still, the different tools come at different costs, and their setup efforts vary (Thissen et al., 2007).

The 3C model was deemed as most suitable for this study as it captures the three major pillars of collaboration, namely communication, cooperation, and coordination, which is a highly relevant part of interacting with ESI. Other similar models focus on other contexts, such as digital tools’ implications in teaching which is captured by the SAMR model (Puentedura, 2010). Even though this model also has been applied in other settings, it is not suitable in this research as it goes beyond the scope of understanding the application of digital tools and rather assesses the incorporation of digital tools. Another model that could have covered the purpose of this study is the DIGCOMP framework (Ferrari, 2013) with the aim to contribute to a better understanding and development of Digital Competence covering dimensions such as communication and problem-solving. However, this model is also referred to as the European digital conference framework and is, thus, developed based on the area of Europe and goes beyond the scope of this research.

15

2.3 Interconnections Between Fields of Research

Based on the literature review, existing literature commonly deals with the above-mentioned areas of research independently. Current research elaborates separately on how innovation benefits from the presence of ESI and how CSTs have influenced the ways of communicating and interacting. Hence, there is a lack of research connecting these areas and, specifically, how firms can leverage ESI with the application of CSTs. We would, therefore, like to combine the phenomenon of using ESI, while examining the application of CSTs in our study. In other words, this research aims to fill existing gaps in the literature in terms of these fields.

3 Methodology

The purpose of the following chapter is to present the research context. Specifically, the adopted research philosophy, design, and approach are presented. These are followed by the methods including data collection, semi-structured interviews, sample selection, interview design, and data analysis. Subsequently, decisions regarding data analysis are presented. Thereafter, the underlying standards of research ethics and research quality are discussed which concludes this chapter.

3.1 Research Philosophy

Research philosophy is defined primarily by two constructs which are ontology and epistemology. While it is important to be familiar with the methodology and methods of a study, it is also essential to understand the underlying philosophy and assumptions the authors apply to fully understand the scientific work. Ontology consists of the basic assumption researchers possess regarding the nature of reality and existence (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). Since this research aims to study innovation processes in SMEs with regards to CSTs, a relativist ontology is selected as the most suitable standpoint. In relativism, facts are dependent on the perspective of the observer and acknowledge that multiple truths exist (Easterby-Smith, et al., 2018; Smith, 2008). Furthermore, the relativism applied in this research can be identified through the usage of different and several interview participants to obtain a vast heterogeneity. Accordingly, this demonstrates that we believe that individuals’ approach and perceive reality from different viewpoints. Similarly, we believe that multiple truths exist of how

16 individuals work with innovation processes and are impacted by CSTs. Hence, we agree that individuals are perceiving situations differently, and include different motivations for how to do so. This aligns with Smith (2008) who argues that the key aspects of relativism include that anything can only be observed in relation to e.g., language and/or social norms and the denial of universal truth. Consequently, to serve the purpose of this study, we take a relativist ontology.

Epistemology is the second part of research design and considers how the nature of knowledge is generated and in which ways it can be used to inquire about the social and physical world. It is made up of two perspectives on knowledge generation which are positivism and social constructionism (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018; Saunders et al., 2019). In accordance with our research topic and a relativist ontology, we develop our research on social constructionist epistemology. According to Easterby-Smith et al (2018), the fundamental basis of social constructionism emphasizes that there is no objective and exterior reality but rather it is socially constructed, and individuals give meaning to it in their interactions with others. Thus, constructionism regards reality as constructed socially. Accordingly, we believe that we continually share a social reality through our interactions with our interview subjects during the interview process. Further, we regard this as objectively factual and subjectively meaningful (Berger & Luckmann, 1991). Similarly, we also have an active presence in the phenomenon by understanding and explaining human behavior and interaction through generalizing the topic from a smaller sample due to its characteristics, to a broader context (Berger & Luckmann, 1991; Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). Hence, given the nature of the phenomenon under study and the primary purpose, we deem social constructionism the most suitable choice for our epistemology. Correspondingly, this study centers on the meaning individuals make of their experience and reality, and not on gathering facts and frequencies. However, according to Bell and Bryman (2007), social constructionism can also lead to findings examined outside of the social context under study.

To summarize, our study approaches the underlying philosophy of a relativist ontology and a social constructionist epistemology. This allows for a holistic and complete situation of the phenomenon we are analyzing and connects to our research approach which will be described in the following section.

17

3.2 Research Design

Social constructionism implicates the emphasis of this research on the usage of a qualitative method to collect data and construct novel theories (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). By addressing the purpose of this study, which focuses on developing an understanding of the process of leveraging ESI with the application of CSTs in the context of SMEs, we aim to fill the gaps in the current literature. Hence, a qualitative exploratory research approach was considered as the most suitable to develop insights and findings for a research area that has not yet received sufficient examination. Consequently, exploratory research allows generating a deeper understanding of a phenomenon that has little prior research by relying on qualitative research data (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

Moreover, as a social constructionism view of epistemology is applied, it led us further to the choice of qualitative research design based on grounded theory. There are multiple approaches to grounded theory, including the Classic, Straussian, and constructivist grounded theory (Kenny & Fourie, 2015). Although all approaches share the same goal of identifying theory grounded in data, they differ in various aspects (Sebastian, 2019). While some argue that the researcher should be free from influences and that prior knowledge should be ignored (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), others apply a more constructivist approach of grounded theory stating that you cannot escape previous knowledge (Charmaz, 2014). In this research, we take Charmaz’s (2014) approach to grounded theory and treat research as a construction but, simultaneously, acknowledge that it occurs under specific conditions. Conditions that we may not be aware of or may not be of our choosing (Charmaz, 2014). Hence, by applying this approach with our defined research philosophy, we acknowledge that our values can shape the facts we identify. Furthermore, using the exploratory method of grounded theory allowed us to examine the process of leveraging ESI in different settings and construct a theory based on the systematically collected data (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). Specifically, we aim to develop a conceptual framework that enriches the existing theory ESI and CSTs through building theoretical analyses from our research data and subsequently verifying their theoretical interpretations, following the grounded theory method (Charmaz, 2014). We collected and analyzed the data simultaneously, which allowed data collection and the analysis phase to shape each other in an iterative process (Charmaz, 2014). Hence, it enabled us to simultaneously investigate and explain the process of

18 leveraging ESI with the application of CSTs, in the context of SMEs, and treat theorizing as an ongoing activity (Charmaz, 2014). Furthermore, to justify our selection, the predetermined requirements for a classic approach ignore prior literature while the Straussian version opposes prior knowledge gained from the literature but with skepticism (Mills et al., 2006). However, both approaches support a more positivist perspective on grounded theory. Since we apply a constructivist approach where reality depends on different perspectives, the perspective of Charmaz (2014) that the researcher is part of the research process rather than separate is more suitable (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018).

3.3 Research Approach

The research approach, together with the research philosophy, guides what method will be applied in the research and enables the researcher to better understand how to conduct the study (Collis & Hussey, 2014; Saunders et al., 2019). In our research, an abductive research approach has been applied as it seemed most suitable given the nature of the research objective. Unlike inductive and deductive approaches, abductive research can explain, develop, and change the theoretical framework before, during, and after the research process. Specifically, abductive research allows for moving back and forth between inductive and open-ended research settings to more hypothetical and deductive attempts to verify hypotheses (Meyer & Lunnay, 2013). Consequently, the abductive approach is useful when the aim is to refine and redevelop theory successively throughout the research process (Alvesson & Sköldberg, 2018; Meyer & Lunnay, 2013) and in the identification and development of codes, categories, and themes (Lipscomb, 2012), which have been made in this study. Furthermore, in this research, there is existing knowledge within the area of ESI that will be advanced with the application of CSTs. Hence, an interaction between induction and deduction will emerge as previous literature will guide the collection of empirical data. Consequently, the empirical data and theory are inevitably linked to each other, as theory is needed to understand empirical observation and vice versa, typical for an abductive research approach (Meyer & Lunnay, 2013). However, there can still be generality challenges associated with abductive research since the reasoning often relies on the reflective abilities of the abductors (authors). As such, it is also possible to question the level of reliability. Yet, we have been very clear in justifying our decisions which help balance the level of

19 reliability and abductive research positively. Moreover, Bishop (2010) highlights that other hypothesis can be abducted with reflection from evidence while other evidence simultaneously can support other hypotheses. In other words, in our study we might transcribe an interview capable of being interpreted as X or Z. But whether which interpretation is ‘correct’ or most accurately explains what the participant said is still difficult to prove. Hence, we acknowledge that there might also exist other interpretations of our data and results. Still, the generality problem can also appear in inductive and deductive research (Lipscomb, 2012).

A grounded theory methodology is most often associated with inductive reasoning (Reichertz, 2009). Still, that the grounded theory approach acknowledges observations and development of theory to be necessary always guided by theory (Charmaz, 2014; Strauss & Corbin, 1990), as well as allows for the fact that researchers must be able to modify or even reject concepts during and due to observations, falls within the abductive research logic (Reichertz, 2009). Applying grounded theory with an approach that falls between induction and deduction is also referred to as iterative grounded theory and is commonly applied by organizational process researchers due to the high flexibility (Orton, 1997). Hence, this approach is suitable for this research as we aim to investigate the process of leveraging ESI with the application of CSTs.

3.4 Method

3.4.1 Data Collection

New and revealing results can only be retrieved and achieved through a systematic form of data collection which includes some specific characteristics. In our paper, the research relies exclusively on non-numeric data that help understand and contextualize what things mean and how things work, also referred to as qualitative data (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). Moreover, using qualitative data in research facilities to (1) illuminate meanings: how individuals make sense of their world, (2) understand how things work, (3) gather individual’s perspectives and experiences, (4) understand how systems work and potential consequences, (5) understand how and why context matters, (6) explore unintended consequences, and (7) identify essential patterns and themes (Patton, 2014).

20 The process of how SMEs leverage ESI with the application of CSTs is highly related to interactions and collaborations. Therefore, to understand the phenomenon under study, we also need to understand the reality and stories of individuals having knowledge within this area. Consequently, this type of data, experience, and stories, is best collected qualitatively by interviews with individuals having experience or have been part of innovation processes where external sources have been leveraged and CSTs have been applied. As a result, to gain a better understanding of the phenomenon and develop valuable qualitative data, we conducted 31 semi-structured interviews as our main source for primary data. The interviews were semi-structured to disclose the situational context and the participants’ subjective ideas and assumptions regarding this unexplored phenomenon (Galkina & Atkova, 2019). 3.4.1.1 Semi-Structured Interviews

Interviews can be structured, semi-structured, or unstructured. Semi-structured interviews are commonly used in exploratory studies (Saunders et al., 2019) and were found to be the most suitable interview method to fulfill the purpose of our research. Semi-structured interviews allow researchers to follow a set of key themes and topics which are identified in previous research and, simultaneously, offer flexibility to ask supplementary questions (Saunders et al., 2019). Consequently, this method encourages the interviewees to provide developed answers, requiring them to reason, elaborate, and motivate their answers (Saunders et al., 2019). Further, it allows for other related topics and valuable additions to arise during the conversations which, in turn, provides the researchers with rich and detailed data (Collis & Hussey, 2014). However, as interviewees are encouraged to speak freely, it creates possibilities to retrieve irrelevant information (Saunders et al., 2019). Therefore, we put much effort into creating an interview guide (Appendix 2), including formulating key questions, and designing an overall layout to minimize the risk of sidetracks. The interview guide was constructed based on our research purpose and key findings from the literature review, following the abductive research approach.

Our semi-structured interviews were constructed with mainly open-ended questions, requiring the interviewees to elaborate on their points. Accordingly, open-ended questions are exploratory in nature (Saunders et al., 2019) and, thus, appropriate for our study. Yet, probing questions and specific and closed questions were occasionally. Probing questions were used to gain deeper insight into what our

21 interviewees just told us, helping to uncover the reasons behind what they said. Specific and closed questions were used to confirm information when needed. Moreover, the order in which the questions were asked varied depending on the flow of the conversation, which is an additional advantage with semi-structured interviews as it allows for this type of adaptation (Saunders et al., 2019).

3.4.1.2 Sample Selection

A purposive sampling method was used in this study which is a form of non-probability sampling design with predetermined criteria for inclusion due to the qualities the participant possesses (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018; Etikan et al., 2016). It is commonly used in qualitative research to identify and determine the information-rich cases for the optimal usage of available resources (Etikan et al., 2016). This technique enables researchers to focus on and select samples regarding the purpose. Hence, potential participants unable to fulfill the purpose are rejected (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). Consequently, this allows for the most relevant information to be obtained as we have carefully filtered the cases and participants, and thus, used limited resources efficiently (Green et al., 2007). However, it is more problematic to draw generalized results applicable to the whole population (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018).

Three predetermined criteria had to be fulfilled by the subjects in this study. First, the companies had to be classified as SMEs, defined as having less than 250 employees and up to 50 million EUR in turnover, following the standard definition of SMEs by the European Commission. Secondly, the SMEs had to be in the region of Jönköping County, following our delimitation. Thirdly, the SMEs should have been involved in two or more interactions with ESI. This criterion was necessary to ensure that the SMEs had been involved with ESI and have experience from the related process. Furthermore, for the sampling of this research, we took six steps to find suitable companies. First, we examined the list of projects that have been granted EU-funding accessible in the project bank provided by Tillväxtverket (Tillväxtverket, 2020). We identified projects that had the aim to support and/or consult SMEs in the region of Jönköping County for continued growth, innovation, and competitiveness. These projects were identified to be a relevant starting point as multiple of the project organizations act as ESI for SMEs. Hence, providing us the possibility to easily identify companies that have had at least one interaction with ESI. Second, we reached out to the project

22 managers of the selected projects to ask for a list of recommendations of firms that fulfilled all our three criteria, mentioned above. Third, the recommended companies were cross-checked with databases that contain public information such as the number of employees and turnover, to assure that each company met the definition of an SME. Additionally, company descriptions and areas of operations were identified. Fourth, this information was documented in an excel list, in which we also marked the projects the companies have been involved with. This allowed us to easily identify companies that have been taking part in multiple projects with ESI and, in that way, determine their relevance for this study. Fifth, based on this information, we created a priority list in which SMEs with the most interactions with ESI, which we were able to identify, were put at the top. In the case of having multiple companies with the same numbers of interactions, we selected based on their relevance for this study in terms of their previous innovation and development efforts and their area of operation. Last, we contacted the companies according to the priority list and scheduled interviews. Our final priority list included 26 companies, of which we were able to schedule interviews with 20 of them.

3.4.1.3 Interview Design

For this study, a total of 31 interviews were performed with 30 individuals. Specifically, 20 SMEs were selected as subjects in which one interview was performed with representatives from each of the SMEs. In 19 of the interviews, we interviewed one company representative. In one of the interviews, two representatives from the company were interviewed. Hence, 20 company interviews were held with a total of 21 company representatives. The company representatives are managers that are personally involved in innovation and development efforts at their respective SMEs. Additionally, 11 supplementary interviews were performed with nine individuals that have been externally involved in the SMEs innovation efforts or have good insights into the SMEs innovation work. As several of these individuals have been involved in projects with multiple of the selected SMEs, the additional interviews allowed us to get an outside perspective from all 20 SMEs. Two of the interviewees have been involved with four respectively seven SMEs, thus, two separate interviews were conducted with each of those individuals due to the length of the interviews. At this point, we had ensured knowledge saturation, meaning that we conducted interviews to the point where no new knowledge was

23 generated (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). Hence, additional interviews would have provided similar insights. Consequently, a total of 31 interviews were conducted with 30 individuals in the period of January 25th to March 26th. In Tables 1 and 2, you find an overview of the participants. Table 1 shows the 20 selected SMEs, including company information and the company representatives. Table 2 shows the interviewed external individuals, including the organization they work for and the SMEs they have been externally involved with.

24 Table 2 – Participants: External to the SMEs

Due to the Covid-19 virus, many of the interviewees were bound to work from home which resulted in all interviews being performed virtually. This gave the advantage of more flexibility, however, some aspects of a face-to-face interview might have been lost, including the immediate contextualization and depth (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018), as well as it restricted the possibility to observe body language (Cater, 2011). Still, as most of the interviews were conducted via video call, we were able to observe and analyze verbal data and some non-verbal cues like facial expressions (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). Furthermore, we used the software Microsoft Teams for the digital interviews. The interviews lasted on average for 43 minutes with the company representatives and 35 minutes with the external individuals, which gave us a total interview time of approximately 21 hours. 30 of the interviews were conducted in Swedish since it is the native language of those interviewees. One interview was conducted in English as that was the shared language of the interviewee and us. The interviews were recorded with Microsoft Teams recording function and with a phone as extra back-up and then processed initially with Microsoft Word dictation into written text. Thereafter, the provisional transcriptions were carefully and manually checked, corrected, and completed. We ended up with 255 pages of raw data.

3.4.2 Data Analysis

This research aims to understand the process of leveraging ESI with the application of CSTs, in the context of SMEs, and therefore, we chose to perform a process analysis. A process logic can be used to explain and understand why an independent (input) factor employs an influence on a dependent (outcome) factor. For example, in this study, how the application of CSTs influences the leverage of

25 ESI in SMEs. Thus, a theory of process includes statements explaining why and how a process develops over time, including why and how things emerge, grow, or terminate (Langley et al., 2013; Van de Ven, 1992).

As grounded theory is applied in this research, a grounded theory strategy for process analysis was chosen to analyze our collected data. This model is suitable when you have details on many similar incidents (Langley, 1999), which is true for this study. It is likely to produce outcomes that are high on accuracy. However, it may be difficult to go from substantive theory to a more general level (Langley, 1999), which is one possible limitation of this method. In section 3.6.2, ‘Transferability’, we describe actions that we have taken to increase the transferability of this study and thus, trying to overcome this possible limitation. Furthermore, the underlying assumption of grounded theory is that data collection and analysis occur simultaneously (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). Hence, we were able to move back and forth between the emerging model and evidence through data gathering and writing. Additionally, since the analysis in this research began from the first interview, it enabled us to direct and adjust for the next interviews and identify irrelevant and misleading questions early in the interview process. Thus, we transcribed the interviews that were recorded to prepare the data for further analysis, which were a key part to ensure a full and rich data basis.

The data was analyzed in different steps, including familiarization, reflection, open coding conceptualizing, focused re-coding, linking, and re-evaluation (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). To familiarize ourselves with the data, we screened all our available and raw data, including transcripts, notes, and recordings. To make sense of the data, we highlighted suitable quotes and words and copied them into an Excel file to get a complete overview of how it connected to our purpose. The Excel list enabled us to further identify first-cycle codes by linking the highlighted quotes and words into systematic categories and keywords. Further, to conceptualize the data, we looked for patterns such as similarities, differences, and frequencies. By doing this, we identified concepts and themes that we deemed to be important for understanding and answering our purpose. This was also made in accordance with Charmaz (2014), stating that codes should be simple, and the researcher should stay close to the data. When the most relevant and important codes and categories were identified, we

26 performed a focused re-coding which further limited the number. This required a process of going back and forth several times between the raw data and the determined codes and categories, also known as second-cycle coding. The process of selecting first-cycle codes is commonly made to develop a framework, while the second-cycle coding aims to frame that data for a more in-depth analysis (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). In our case, to understand the process of leveraging ESI with the application of CSTs and, thus, fulfill the purpose of this study, we first investigated the process of leveraging ESI to determine the phases of the process in the first cycle coding. Then, in the second-cycle coding, we analyzed codes related to CSTs to understand the application of those in the different phases of the process. Consequently, the main categories that evolved are related to the process of leveraging ESI whereas the application of CSTs is captured by sub-categories related to specific main categories. It resulted in 16 categories that were clustered into six themes. Further, patterns and linkages were established between the codes and categories which emerged into a theory. Hence, as we continued to work iteratively between our data and the identified literature, we converged upon a process model showing how SMEs leverage ESI with the application of CSTs. Further, we performed a final round of coding to alter, merge, and elaborate on earlier codes as we developed the model. Thus, we performed a re-evaluation with second-cycle coding which eventually led us to the final theory. Finally, to sort the codes, categories, and themes, a filter function in Excel was applied which enabled us to identify the quotes and statements belonging to a particular rubric. In Figure 2, an overview of our coding, including categories, subcategories, and themes is provided. In Figure 3, data related to each of the categories and subcategories can be identified.

27 Figure 2 - Coding Tree

28 Figure 3 – Coding Tree: Data Examples

29

3.5 Research Ethics

Research can have a major impact on individuals and society, which highlights the importance of taking ethical considerations into account. As researchers investigate companies, company processes, and interactions of different stakeholders, which potentially can harm participants and/or the firms, researchers must carefully adhere to several principles that are suitable for their context of study to establish research ethics, to balance the ethical components, and the value that the research can add to academia (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018; Saunders et al., 2019; Bell & Bryman, 2007). Consequently, researchers must acknowledge and be aware of the potential dynamics that their findings may set in motion (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). In this study, the eleven key principles for research ethics developed by Bell and Bryman (2007) are used. By taking the following outlined principles into account, we were able to develop a suitable framework for maintaining a high level of ethics in conducting our study. A description of the ethical considerations combined with reflections and actions is proposed to stimulate other researchers to act accordingly.

The “eleven categories of ethical principles” (Bell & Bryman, 2007, p.71): 1. Ensuring no physical and psychological harm to participants

2. Respecting participants’ dignity 3. Establishing fully informed consent 4. Ensuring confidentiality of research data

5. Protecting the privacy of individuals and organizations 6. Protecting the anonymity of individuals and organizations 7. Communicating honestly and transparently about the research 8. Preventing deceptions about the research