Department of English Bachelor’s Degree Project English Linguistics

Autumn 2020

Contact-induced

change and variation in

Middle English

morphology:

A case study on get

Contact-induced change and

variation in Middle English

morphology:

A case study on get

Abstract

The present study explores the role of interlingual identification in contact between speakers of Old Norse and Old English. The study focuses on the word get as it occurred throughout a selection of texts in the Middle English period. The Old English and Old Norse words for get were cognate, which meant that some phonological and morphological characteristics of the word were similar when the contact between the two speaker communities occurred. A Construction Morphology framework is applied where inflecting features of words are treated as constructions. Interlingually identifiable constructions in Old English and Old Norse are identified by comparing forms, such as vowel alternations or affixes, with the function (i.e., meaning) which they denote. The Middle English dialectal forms were furthermore compared synchronically, and a sociohistorical perspective was considered to establish whether the areas where the Vikings settled and that came under Scandinavian rule in the Danelaw displayed more advanced leveling and/or conformation with the Old Norse system of conjugation. Additionally, the present study sought to explore cognitive processes involved in letting specific forms remain in a contact situation. It was concluded that there were two interlingually identifiable constructions: the past tense vowel alternation from <e> in the present tense, to <a> in the 1st preterite, and the past participle -en suffix. These constructions had survived in all the Middle English dialects, and they are furthermore what is left in the contemporary modern paradigm of

get. Moreover, it is plausible that these constructions survived the morphological

leveling because interlingual identification allowed the same form to trigger the same intended cognitive representation in both speaker groups in the contact situation. The results concludingly suggest that morphological constructions that were not interlingually identifiable were discarded in the morphological leveling that resulted from contact between speakers of Old English and Old Norse.

Keywords

Language contact, Language change, Middle English, Old Norse, Cognitive linguistics, Old English.

Contents

1. Introduction ... 1

1.2. Aim of study ... 3

2. Background ... 3

2.1. Old Norse, Old English, and the Viking settlements in England ... 3

2.2. Sociohistorical approaches to morphological change and variation in Middle English ... 4

2.3. Cognitive Contact Linguistics ... 7

2.4. Construction Morphology ... 8

3. Method and material ... 8

3.1. Selecting material and extracting data ... 8

3.2. Material ... 8

3.2.1. London: The Canterbury Tales ... 9

3.2.2. Southern: Sir Tristrem ... 9

3.2.3. West Midlands: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and William of Palerne 9 3.2.4. East Midlands: Havelok the Dane and The Paston Letters ... 9

3.2.5. Northern: Cursor Mundi ... 9

3.3. Methodology and theoretical framework ... 10

4. Results ... 10 5. Discussion ... 12 5.1. London ... 12 5.2. Southern ... 13 5.3. West Midlands ... 14 5.4. East Midlands ... 14 5.5. Northern ... 15

5.6. Synchronic comparative discussion ... 16

5.7. Cognitivist perspectives ... 17 6. Conclusion ... 17 References ... 19 Primary sources ... 19 Figures ... 20 Secondary sources ... 20

1. Introduction

The transition from Old to Middle English is a peculiar phase in the history of the English language. Dance (2014) discussed how grammar plays a significant role in defining the transition from Old English (henceforth OE) to Middle English (henceforth ME),and Trudgill (2010) described how the drastic decline of the rich OE morphology caused the English language to go from synthetic, to analytic.1 Scholars have reached a sort of consensus on that transition fromOE to ME is, as Dance (2014) noted, largely defined by grammatical changes, including morphological loss and simplification.

However, there is still no unified view on why these changes occurred (Trudgill, 2010). Contact-induced change has been explored as an explanation to the decline of OE morphology, and several scholars have argued that contact with Old Norse (henceforth ON) and/or Anglo-Norman2 (henceforth AN) was the cause or catalyst of the morphological decay that took place in the transition to ME (Bowern & Ewans, 2015; Trudgill, 2010; O’Neil, 2019). Bailey and Maroldt (1977) were among the first to propose a Middle English Creolization Hypothesis, where they claimed that contact with AN caused creolization. However, other scholars have argued that if a creolization process took place, AN was not involved (O’Neil, 2019; Trudgill, 2010). Barber et al. (2011) wrote that the mixing of OE and ON that took place in the Anglo-Scandinavian3 settlements is to blame for much of the morphological loss in the late OE period. Trudgill (2010) also argued that contact with ON could have been a trigger of morphological loss, and furthermore claims that the case has always been stronger for ON regarding a process of creolization since the first signs of simplified morphology are traceable to Northern and Northeastern regions where the Vikings settled. Moreover, ON and OE were mutually intelligible, meaning that the Vikings and the Anglo-Saxons were likely to have understood each other (Barber et al., 2011; Trudgill, 2010; O’Neil, 2019). The mutual intelligibility allowed scholars to consider the contact-induced changes from a new perspective, and the possibility of a koinézation hypothesis has been suggested (O’Neil, 2019). A koiné is created when two mutually intelligible languages that are of roughly equal prestige blend and form a new variety (O’Neil, 2019). Thus, the Northern and East Midlands dialects of ME filled all the criteria for a koiné (O’Neil, 2019). The emphasis on mutual intelligibility in the koiné discussion suggests that it is the mutual characteristics of the languages that should be investigated further to uncover the specific details of how certain features survived the great morphological decay in OE.

1 Synthetic languages are highly inflected, whereas analytic languages express tense etc. syntactically rather

than morphologically (Carstairs-McCarthy, 2018)

2 The variety of Norman French spoken by the Normans in England. 3 Settlements where both Scandinavians and Anglo-Saxons lived.

The mutual intelligibility of OE and ON could possibly be explained by the many shared characteristics that were inherited from Proto-Germanic, such as morphological processes. An important morphological process shared by the Germanic languages is the strong verb ablaut: verb inflection by alternation of the stem vowel (Mailhammer, 2007). Though the ablaut phenomenon was something the Germanic languages had in common, the specific patterns of ablaut were not universal. Thus, certain conjugational patterns would differ between ON and OE (Mitchell & Robinson, 1992). Moreover, some of the strong verbs in the English language are regarded as borrowings from ON, which is remarkable considering that borrowed verbs commonly take on weak forms (Carstairs-McCarthy, 2018). Get is one of the strong verbs has been considered a borrowing from ON (Lutz, 2017).However, the OE word for get was gietan, and it was cognate with ON geta that was supposedly borrowed into the English language (Brinton & Bergs, 2017). Lutz (2017) mentions the cognate status of the OE and ON words but does not comment on whether get should still be considered a borrowing. Weinreich (1979) defined a borrowing as the transfer of a lexical unit from one language to the other and wrote that borrowed words were “additions to an inventory” (p. 1). Hence, get should not be considered a borrowing since gietan and geta were cognate; they were arguably the same lexical unit as they derived from the same Germanic root.

Since morphological changes have been emphasized when defining the borders between OE and ME, and language contact furthermore seems to play an important role in those morphological changes, it should be beneficial to investigate an OE and ON cognate verb that was conjugated by ablaut. The ablaut patterns of the East Midlands dialect of ME were studied by Rettger (1934) who, like others before him, found that the ME conjugational pattern of get corresponded with that of an OE class 5 strong verb. However, the ME conjugation of get also corresponds with an ON class 5 strong verb. As mentioned previously, the ablaut patterns of OE and ON as both contained features derived from the Proto-Germanic ablaut grades. In the case of get, the vowel alternations were strikingly similar, whereas the inflectional morphemes differed in many of the forms. As similarities in the languages enabled crosslinguistic communication between the two speaker communities, the similarities in the patterns of conjugation might also be the key to what forms were kept through the morphological

leveling4 that led to the decay of OE morphology. Interlingual identification

(Weinreich, 1979) could thus possibly provide an explanation to what forms were kept in the language. Weinreich (1979) specified that interlingual identification occurs when two languages in a contact situation had a similar form that carried the same semantics in both languages.

4 Hock (1986) summarizes morphological leveling as “the elimination of (unimportant) morpheme or stem

The present study investigates the conjugation of get in the ME period, and draws on the on the theoretical frameworks of Contact Linguistics, as well as Sociohistorical and Cognitive Linguistics to explore possible explanations to why certain conjugations remained when two cognate words with similar ablaut patternscame into contact.

1.2. Aim of study

The aim of this study is to establish what influence ON contact had on the conjugation of get in the ME period. Furthermore, the study seeks to explore the effects of contact between two closely related languages by studying an English word that is considered a lexical borrowing from ON. The study aims to answer the following questions:

• What inflecting features did get inherit from the OE and/or ON conjugational systems?

• What differences were there between areas that were settled by

Scandinavians versus areas that were not, regarding the conjugation of get?

2. Background

This section will present the historical background (Section 2.1.) and previous research related to the present study (Sections 2.2, 2.3, and 2.4.)

2.1. Old Norse, Old English, and the Viking settlements in England

Between 750 and 1050, CE the Vikings plundered the Northern and Northeastern parts of England where they also came to settle among the OE-speaking Anglo-Saxons (Barber et al., 2011). The Vikings that settled in these parts of England spoke a dialect of East Norse, which, for reasons of simplicity, will be referred to as ON in this paper. To make further distinction between the North Germanic dialects would be overabundant for the purpose of this study, especially considering that the first signs of dialectal distinction in ON were seen around 800 CE (Barber, et al., 2011). As mentioned in Section 1, ON and OE were mutually intelligible and had similar processes for conjugating strong verbs. OE had a rather complex conjugational system, of which only fragments are left in the English we speak today. Verbs in OE that were conjugated by ablaut (i.e., strong verbs) were regulated by a set of phonological and morphological rules. The strong verbs of OE are divided into seven classes, where the vowel that should be produced in the 1st preterite, 2nd preterite, and the past participle is determined by either the stem vowel alone, or the stem vowel the consonant or consonants that follow the stem vowel (Mitchell & Robinson, 1992). The ON system closely resembled that of OE, but as mentioned previously: they were not identical. The gradation from infinitive, to 1st preterite, and to past participle was e - æ - e in OE, and in ON it was e - a - e. The OE gietan was pronounced with an initial /j/, which caused the /æ/ to become /ea/ in the 1st preterite (Brinton & Bergs, 2017; Mitchell & Robinson, 1992). Thus, the gradation series were very similar, and endings and affixation would

likely have caused more issues as the differences were larger with regards to that matter. Because many OE diphthongs monophthongized in the late OE period and throughout the transition to ME, it is possible that the 1st preterite was pronounced /jɑt/ when contact with ON was becoming more widespread in England (Barber et al. 2011). This pronunciation would thus have made the OE 1st preterite even more similar to the ON equivalent. The complex conjugational systems of OE and ON would require a paper of their ownif they were to be described in detail, and affixation and endings will thus not be elaborated here. Nevertheless, the presentation of the results will clearly display the differences and similarities in the systems that are necessary to be aware of for the purpose of this study.

2.2. Sociohistorical approaches to morphological change and variation in Middle English

ME is commonly divided into five dialects: Northern, East Midlands, West Midlands, Southern, and Kentish. This study has not included Kentish, and instead focuses on London. London is located by the river Thames, roughly around the area where the Southern, East Midlands, and Kentish borders meet. The London dialect is furthermore the origin of contemporary Standard English (Brinton & Bergs, 2017; Lutz, 2017). Figure 1 shows the geographical division of the ME dialects.

Figure 1: Map showing the geographical division of the Middle English dialects (Harvard University).

To fully understand the contact between different languages in Medieval England, it is important to grasp the concept of stratification. Stratification of languages is based on the social classes of the speaker communities and can thus be defined as the hierarchical layering of languages or dialects based on the status of the language and its speakers (Winters, 2014). A language at the top of the social and linguistic hierarchy is the

superstrate language, and the language at the bottom is the substrate language

(Winters, 2014). Moreover, stratification affects the nature of the influence a language will have in a contact situation. A superstrate language often functions as a lexifier in official settings meaning that it commonly results in lexical borrowing, whereas substrate influence more often results in for example simplification of morphology (Lutz, 2017; Trudgill, 2010; O’Neil, 2019). If two languages are of equal prestige, they are adstratal; which is the type of relationship that most often leads to borrowing of structural features such as inflectional morphemes (Trudgill, 2010; O’Neil, 2019). Though the Vikings never settled in London, ON influence still reached the London dialect. Lutz (2017) studied Norse loans in late medieval London and noted that borrowings from ON entered the London dialect via dialectal contact as Northerners migrated to London. Furthermore, London was the home of the Norman nobility who had settled there after the Norman Conquest in 1066 (Barber et al. 2011). Thus, the main source of linguistic influence in London was AN, and not ON as in the Midlands and the North. Lutz (2017) discussed the lack of early ON influence in the London dialect, and claimed that most of the ON borrowings reached London after Chaucer’s time. The language contact that occurred in London was furthermore of a different nature than the contact with ON. Dalton-Puffer (1995) wrote that the speaker communities of AN and English were clearly separated by social class: the AN speaker community was mostly made up of the nobility and the high clergy, whereas English was spoken by the lower classes. This entails that AN became the superstrate language as the Normans took over all positions of power, and English consequently became the substrate language (Dalton-Puffer, 1995). What role AN played in causing morphosyntactic changes in the transition from OE to ME is, however, a matter of debate. Domingue (1977) claimed that AN did in fact play a part in the morphosyntactic changes that caused the English language to become more analytic in the ME period. However, O’Neil (2019) discussed how the contact with AN would have resulted in bilingual individuals rather than crosslinguistic interpersonal interactions. Arguments that AN created individual bilingualism are furthermore supported by Roig-Marin (2018) who found evidence of bilingualism in scribes during the ME period, and Ingham (referenced by O’Neil, 2019) who presented evidence of bilingualism in the educated classes where children were taught by Normans in AN. Nevertheless, AN would likely not have triggered morphological changes, as ON and AN were not used for crosslinguistic communication since they were spoken in separate contexts (O’Neil, 2019).

As mentioned in Section 1, scholars have argued that ON and OE were of roughly equal prestige in the Midlands and in the North. However, in the late 9th century the

Northeastern parts of England came under Scandinavian rule. The rulers of the West Saxon and Scandinavian peoples came to an agreement where a border between their lands was defined, and the area ruled by the Scandinavians has come to be referred to as theDanelaw (Barber et al. 2011; Mitchell & Robinson, 1992). Lutz (2017) argued that

the Danelaw created a situation where ON became the superstrate language. Lutz’s (2017) arguments supporting superstratum influence rely mostly on the use of ON in law documents in the Danelaw, and Lutz has thus mainly considered a context where ON was indisputably the superstrate lexifier. Nevertheless, Lutz (2017) demonstrated conclusively that ON did have a certain degree of superstratum influence. Moreover, when studying the situation in the Northeastern parts of England which became part of the Danelaw, it should be wise to consider that the Vikings’ travels to England had begun around 800, with the so-called Great Heathen Army arriving in England at 865 (Barber et al. 2011; Mitchell & Robinson, 1992). ON would thus have been present in England for nearly a century prior to the Danelaw-agreement, and when the Danelaw was dissolved as the West Saxons reclaimed the area in the 11th century ON would have lost its superstrate position.Watts (referenced by O’Neil 2019) furthermore claimed that the contact situation between speakers of ON and OE would have been of a more intimate nature than that of AN and OE, and envisioned casual conversations taking place in the everyday life of Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian farmers. The situation described by Watts is thus very different from the OE and AN contact-situation in London. Townend (referenced by Trudgill, 2010, and O’Neil, 2019) also argued that the relation between OE and ON had been adstratal and found it particularly important to consider how intercultural marriages affected the outcomes of the linguistic contact. Trudgill (2010) agrees that ON had adstratum influence on OE but adds that the type of intimate contact that occurred between OE and ON usually causes complexification of morphology. However, Trudgill (2010) explains that similarities in the languages prevented complexification: the inventories of morphological categories were already very similar which meant that the speakers did not need to borrow these kinds of features. What Trudgill presented could thus imply that interlingual identification played a major role in defining the morphosyntactic changes caused by contact with ON. Considering the arguments supporting adstratum influence (O’Neil, 2019; Trudgill, 2010), as well as Lutz’s (2017) evidence of superstratum influence in the Danelaw, ON could arguably have influenced OE from both positions. The power dynamic between the speaker communities was clearly not static, and ON was not necessarily superstrate and adstrate to OE at the same point in time. Nevertheless, the dual nature of the relationship between OE and ON suggests that ON, unlike AN, would have reached members of all social classes – consequently affecting the language of peasants as well as nobility.

Though the present study is mostly concerned with Anglo-Scandinavian contact, it would be fair to mention Trudgill’s (2010) discussion of what contact with Celtic languages might have caused in terms of morphological decay. Trudgill (2010) noted that the morphological levelling that occurred already in the OE period was possibly a result of contact with Celtic languages. Trudgill (2010) argued that this was particularly

important since the contact with Celtic-speaking groups predates the contact with both ON and AN, and the Northern- and Midlands regions would thus have been subjected to contact with two languages – first a Celtic language, and then ON – prior to the Norman Conquest. The additional linguistic contact in the North could explain why morphological loss occurred both earlier and faster in the Northern dialects (Trudgill, 2010).

2.3. Cognitive Contact Linguistics

Onysko (in Zenner et al. 2019) emphasized the importance of tying social and cognitive factors together when studying language change. Despite this, there is little research on contact-induced change in OE and ME where a cognitivist framework has been applied. Onysko (in Zenner et al. 2019) furthermore explains how Construction Grammar has been utilized to create a framework for analyzing crosslinguistic communication. Therefore, the present study has adopted a Construction Grammar-approach to morphology (see Booij, 2013, on Construction Morphology) where inflecting affixes and vowel alternations are conceptualized as constructions (i.e., form-meaning pairs). Construction Morphology will be elaborated on further in the next subsection.

If mutual intelligibility is conceptualized in terms of Construction Grammar, one could say that mutually intelligible languages have a large number of shared constructions: identical or similar forms that express the same meaning in both languages. OE and ON would thus have had a considerable number of constructions with forms that carried the same meanings in both languages. Bybee & Becker (in Bowern & Ewans, 2015) explained that high-frequency constructions have stronger cognitive representations and are therefore less likely to be replaced as the language changes. The example given by Bybee & Becker (in Bowern & Ewans, 2015) is the -ed suffix that attaches to weak verbs to mark past tense. Because ON -inn, and OE -en attached to all strong verbs in the respective languages, they too should have strong cognitive representations. In addition, the suffixes have a similar form which could possibly have been interlingually identifiable if the form successfully triggered the same cognitive representation in both speakers. In addition, being able to attach to all strong verbs could suggest that the suffixes were also occurring very frequently. Onysko (in Zenner et al. 2019) wrote that in a contact situation where morphological features are borrowed “structurally complex form-meaning units (i.e., borrowed grammatical constructions) have become part of the neural activation patterns of the recipient language.” (p.38) This is particularly interesting considering the OE and ON terms are cognate and have a similar past participle marker. The neural activation patterns could thus already have functioned to recognize the lexeme itself, as well as the grammatical construction (i.e., the affix attached to the lexeme and the meaning denoted by the affix).

2.4. Construction Morphology

Construction Morphology is an adaptation of Construction Grammar that is specifically focused on morphology (Booij, 2013). Booij (2013) explained that the complex relations between form and meaning in inflectional morphology can be analyzed efficiently using this framework because any inflecting property of a word can be treated as a form, and the semantic property of that inflecting property can in extension be thought of as a meaning. The Construction Morphology approach therefore seems ideal to apply when analyzing ME morphology in relation to the OE and ON ablaut grades, as vowel alternations and affixes can be analyzed using the same framework. In fact, Booij (2013) specifically mentions that the framework is applicable “in cases of nonconcatenative morphology such as vowel alternation, the mechanism used for making the past tense forms of the strong verbs in Germanic languages” (p. 265), which further justifies the use of this approach in the present study. The application of this framework in the present study will be elaborated on in more detail in the following section.

3. Method and material

This section will describe the process of selecting material, the material itself, and the method of analysis. The material is chosen to enable a synchronic comparison, with a diachronic element, and they are furthermore mainly literary works.

3.1. Selecting material and extracting data

The material was selected using University of Michigan’s Middle English Dictionary (n.d.), where the entry on geten gave an overview of the occurrences of get in ME texts. The present study is only concerned with the transitive get, with a sense such as ‘obtain’, ‘acquire’, ‘catch’, or ‘fetch’, and occurrences with other senses were thus excluded. The texts for the material were chosen based on the following criteria:

• At least 3 occurrences of get within the text that represent 3 different morphological categories, i.e., at least 3 tokens of 3 different types.

• The text must have been situated geographically through previous research on its origins.

After selecting the texts excerpts were extracted that were extensive enough to perform a satisfactory morphological analysis; meaning that if an analysis was not possible based on the token in its direct syntactic context additional text from the same page or stanza was extracted, and inflectional features of other words would then enable the data to be interpreted correctly.

3.2. Material

3.2.1. London: The Canterbury Tales

The Canterbury Tales was written by Geoffrey Chaucer in the late 14th century. The

Canterbury Tales is a framed collection of tales, where the frame-narrative is a pilgrimage, and the tales are in turn told by the different pilgrims (Greenblatt, 2018). The genres of the individual tales vary, but the work is at the essence a satire (Greenblatt, 2018). Furthermore, Chaucer’s life is well documented in historical documents, and we can thus say with certainty that Chaucer lived in London, was in association with the Norman nobility, and could speak French (Greenblatt, 2018).

3.2.2. Southern: Sir Tristrem

Sir Tristrem is a metrical romance written ca 1330 by an unknown author (Lupack,

1994). Though the origins of this text have been debated, the most convincing evidence, such as the use of Southern-specific pronouns, suggests that it was written in the South of England (Lupack, 1994).

3.2.3. West Midlands: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and William of

Palerne

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is a metrical romance written in the late 14th century, by a writer whose name remains unknown (Greenblatt, 2018). The text has been traced dialectally to the northern parts of the West Midlands (Meecham-Jones, 2017). Furthermore, it is notable that Sir Gawain and the Green Knight contains an extraordinary number of ON loanwords (Dance, 2018).

William of Palerne is also a metrical romance, and it was written in the mid-14th century (Skeat, 1867). In contrast to the Northern Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, William of

Palerne was written in the Southern parts of the West Midlands (Skeat, 1867).

3.2.4. East Midlands: Havelok the Dane and The Paston Letters

Havelok the Dane is a metrical romance written in the early 14th century. The dialect it

is written in is that of North Lincolnshire (Dickins & Wilson, 1951).

The Paston Letters stand out from the rest of the material, as they are largely made up

of interpersonal correspondence. The Paston Letters provide a diachronic element to the study, as they were written in the 15th-16th century as opposed to the 14th like the rest of the material.

3.2.5. Northern: Cursor Mundi

Cursor Mundi is a religious poetic work written by an unknown author in the early 14th

century. Dickins & Wilson (1951) emphasized the author’s “literary sense” (p.114), which makes Cursor Mundi stand out from other religious texts. The literary qualities of

Cursor Mundi arguably make the work suitable for comparison with the metrical

romances that make up most of the other material for the present study.

3.3. Methodology and theoretical framework

The method of analysis is close reading of the extracted excerpts, including a morphological analysis. Contact Linguistics (Weinreich, 1979) is the foundation of the theoretical framework in the present study. The complexity of studying language contact and contact-induced change calls for a broad approach where several factors must be considered (Onysko in Zenner et al., 2019). Hence, the present study considers sociohistorical factors, and ties Cognitivist theories to concepts from Contact Linguistics. Moreover, Construction Morphology has been utilized to analyze and explain contact-induced change. The concept of constructions has thus been applied to inflectional morphology by treating any inflecting alternation or addition to the infinitive as a form, and the function that form denotes as the meaning. In other words, an affix or a vowel alternation can be a form, and the tense, mood or number that affix or vowel alternation marks is the meaning. Furthermore, entire words and their meanings can also be treated as constructions (Booij, 2013) and the tokens and types that were extracted will thus be referred to as forms. Nevertheless, for a holistic approach to inflectional morphology, the Constructivist framework (Booij, 2013) is combined with a more traditional framework for morphological analysis (Carstairs-McCarthy, 2018); meaning that, in the present study, affixation and vowel alternation will be discussed as constructions, but also as morphemes and conjugational processes.

4. Results

The present study found 60 tokens distributed as follows:

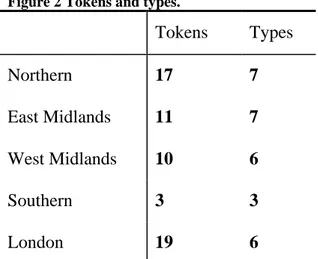

Figure 2 Tokens and types.

Tokens Types Northern 17 7 East Midlands 11 7 West Midlands 10 6 Southern 3 3 London 19 6

For clarification, in this case type refers to different forms within one morphological category, as well as identical forms from separate morphological categories. Form

furthermore refers to the orthographical or phonological representation tied to a meaning. Thus, the West Midlands gete which occurs in 4 separate morphological categories is regarded as 4 types despite all those types having the same orthographical form. The same applies to the past participles geten and gotten in the East Midlands, which are within the same morphological category but counts as two types as they have different orthographical forms. The term form will henceforth be used for anything that denotes meaning – entire words as well as morphemes. Form is arguably a more holistic term than type, and it is furthermore the most appropriate term to use with regards to the Constructivist framework. It is worth noting that some of the forms featured in the tables occurred with orthographical variation where “h” was used in a manner that was arguably ornamental; meaning that the “h” would not have been pronounced. Because the scope of the present study would not allow for an elaborate discussion on such orthographical variation in ME, only the variants without the ornamental “h” are featured in the tables.5

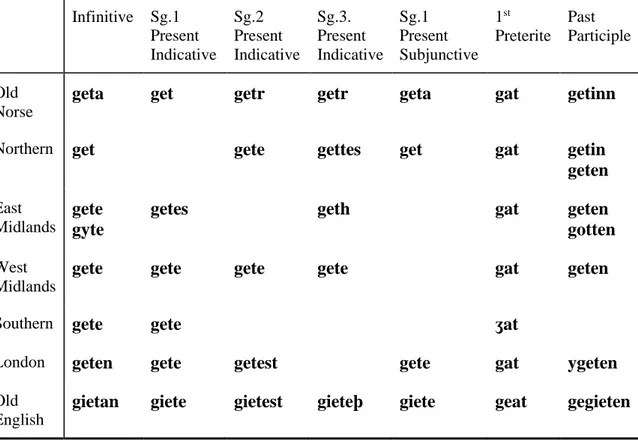

Table 1 displays an overview of all the ME dialectal forms from the data, compared to the equivalent forms in Old Norse, and Old English.

Table 1 Overview of all types/forms.

Infinitive Sg.1 Present Indicative Sg.2 Present Indicative Sg.3. Present Indicative Sg.1 Present Subjunctive 1st Preterite Past Participle Old Norse

geta get getr getr geta gat getinn

Northern get gete gettes get gat getin

geten

East Midlands

gete gyte

getes geth gat geten

gotten

West Midlands

gete gete gete gete gat geten

Southern gete gete ʒat

London geten gete getest gete gat ygeten

Old English

gietan giete gietest gieteþ giete geat gegieten

In Table 1 the dialects are arranged so that the one with the most ON influence is adjacent to ON, and the one with forms that mostly resemble those from OE is placed

adjacent to OE. The following section will elaborate on the results from each dialect, and then discuss the sociohistorical and cognitive factors behind any morphological changes.

5. Discussion

In this section, each dialect will first be discussed separately. This is then followed by a discussion with synchronic perspective – and to some extent diachronic - on the dialects, and cognitive perspectives on the morphological leveling.

5.1. London

Table 2 displays the forms from the London dialect.

Table 2: London forms with ON and OE equivalents.

Infinitive Sg.1 Present Indicative Sg.2 Present Indicative Sg.1 Present Subjunctive 1st Preterite Past Participle

London geten gete getest gete gat ygeten

Old English gietan giete gietest giete geat gegieten

Old Norse geta get getr geta gat getinn

Table 2 shows that the conjugation of get in the London dialect follows the pattern of an OE class 5 strong verb. Sg.1 and sg.2 are still distinguished at this point, as seen in the difference between sg.1 present indicative and sg.2 present indicative where the -st suffix from the OE system remains as a marker of sg.2. Furthermore, the ge- prefix that was commonly used to mark past participles in OE (Mitchell & Robinson, 1992) has been reduced to y-. In some situations, namely when the past participle follows a letter representing a front vowel, such as <i> or <e>, the y- prefix is left out in the text. Moreover, there are no clear signs of morphological leveling which is no surprise considering London was never settled by the Vikings that settled in the Northeastern parts of England, where Trudgill (2010) furthermore noted that the earliest signs of simplified morphology have been observed.

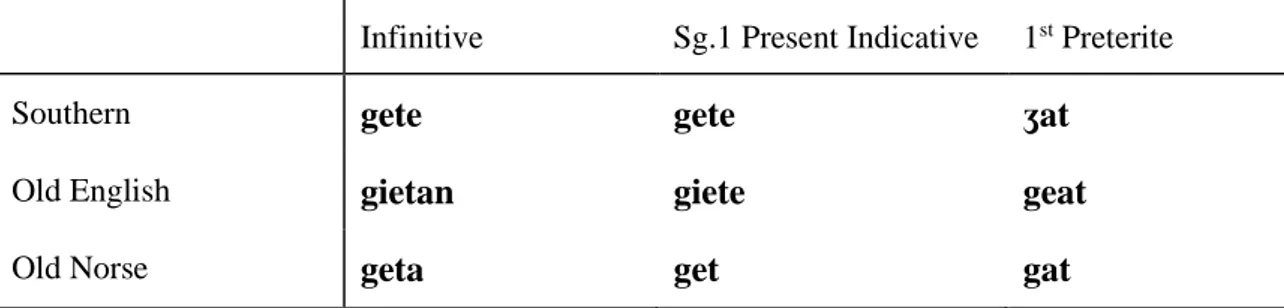

5.2. Southern

Table 3 displays the forms from the Southern dialect in comparison with OE and ON forms.

Table 3: Southern forms with ON and OE equivalents.

Infinitive Sg.1 Present Indicative 1st Preterite

Southern gete gete ʒat

Old English gietan giete geat

Old Norse geta get gat

It is notable that the 1st preterite in Table 3 has an initial <ʒ> where the other dialects, as well as OE and ON, have a <g>. <ʒ> could possibly represent a more palatalized pronunciation of the initial consonant than a <g> would, but since orthography was not standardized at this point, it is difficult to say exactly what sound the letter represented. Determining what phoneme <ʒ> represents is made even more difficult by the fact that it was not used consistently by the author. Nevertheless, <ʒ> does not seem to have an inflecting function and the letter will not be elaborated further.

Table 3 clearly displays the effects of morphological leveling in the Southern dialect, as observed in the infinitive and sg.1 present indicative. The OE system distinguished between these, but the two morphological categories now feature the same form. This suggests that the distinction was made syntactically, meaning that the language had become more analytic. Moreover, the leveling could have been caused by internal changes in OE, where phonological factors affected morphemes and ultimately caused morphological simplification (Lutz, 2017). These internal changes have been discussed by Allen (1996) as well as O’Neil (2019) who argued that internal changes in OE caused simplification of morphology, and that advanced morphological leveling had occurred already in the OE period prior to the arrival of the Vikings and the Normans. Nevertheless, the results of the present study confirm what the scholars mentioned above had already found: morphological leveling occurred in dialects that had not been affected by ON contact.

5.3. West Midlands

As seen in Table 4, leveling has caused everything in the present tense to be expressed using the same form.

Table 4: West Midlands forms with ON and OE equivalents.

Infinitive Pl.1 Present Indicative Sg.2 Present Indicative Sg.3 Present Indicative 1st Preterite Past Participle West Midlands

gete gete gete gete gat geten

gaten

Old Norse geta get getr getr gat getinn

Old English gietan giete gietest gieteþ geat gegieten

Table 4 shows that in the ME West Midlands forms, leveling has eliminated all the different endings found in the OE and ON equivalents. It is furthermore notable that none of the forms in the present tense of OE and ON were identical and it would thus have caused confusion to use the differing forms in crosslinguistic communication. Leveling all present tense forms down to one was possibly the most efficient way enable successful crosslinguistic interaction between the two speaker groups. Moreover, the past participle is not marked by a prefix, which could imply that geten is a development of ON getinn. However, the past participle-form gaten stands out in the data as it has an <a> stem just like the 1st preterite. A similar phenomenon occurs in the East Midlands dialect, and this phenomenon will be elaborated on in the next subsection.

5.4. East Midlands

As seen in Table 5, the results of the present study confirm that which has previously been observed by other scholars: the vowel alternation of get corresponds with that of an OE class 5 strong verb (Rettger, 1934).

Table 5: East Midlands forms with ON and OE equivalents.

Infinitive Sg.1 Present Indicative Sg.3 Present Indicative 1st Preterite Past Participle East Midlands gete

gyte

getes geth gat geten

gotten

Old Norse geta get getr gat getinn

Old English gietan giete gieteþ geat gegieten

The lack of a prefix in the past participle suggests that the foundation of the strong verb conjugations in the East Midlands, at least when it comes to get, could have been the

ON ablaut grades. However, it is notable that the present tense forms do not clearly correspond with those of ON or OE. Brinton and Bergs (2017) discussed how the ME dialects featured a variety of endings in the present indicative, such as -s seen in the sg.1 present indicative, and -th in sg.3 present indicative in Table 5. These endings occurred under certain morphosyntactic conditioning and both the conditioning and endings varied throughout the dialects (Brinton & Bergs, 2017). It has furthermore been suggested that the endings that are specific to the Northeastern regions are a result of ON contact (Brinton & Bergs, 2017). Moreover, the past participle gotten is from The

Paston Letters which, as mentioned, is a slightly later text than the rest of the material.

This form had evolved through an assimilation of the past tense form, which was often

got in the 16th century (Oxford English Dictionary, 1989). The stem vowel has gone through a shift as gotten has a stem represented by an <o>. However, the <o> stem is not used consistently throughout The Paston Letters, and the shift could thus have been at an early stage when the letters were written. Though elaboration on the technicalities of the phonological changes that caused this will not fit within the scope of this paper, the results from The Paston Letters are arguably still interesting to include as they show an early stage in the development towards the full paradigm of the contemporary get, including the regional past participle gotten.

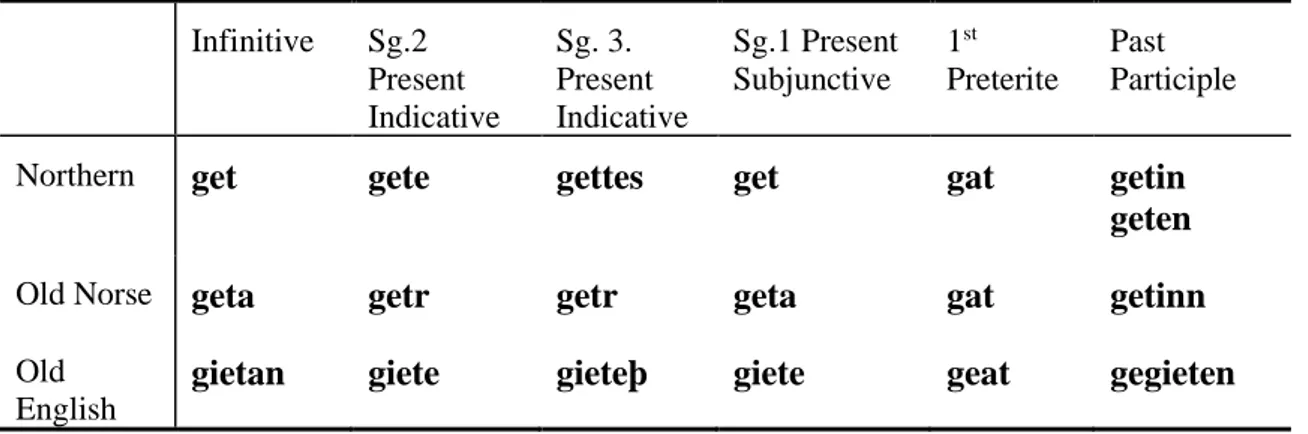

5.5. Northern

Table 6 shows the Northern dialectal forms in comparison to the ON and OE equivalents.

Table 6: Northern forms with ON and OE equivalents.

Infinitive Sg.2 Present Indicative Sg. 3. Present Indicative Sg.1 Present Subjunctive 1st Preterite Past Participle

Northern get gete gettes get gat getin

geten

Old Norse geta getr getr geta gat getinn

Old English

gietan giete gieteþ giete geat gegieten

The Northern dialect unsurprisingly shows signs ON influence, most strikingly in the past participle getin, which is nearly identical to the ON getinn. Furthermore, there is no prefix in the past participle in either of the ME forms, which is possibly a sign of ON influence considering the ON past participle did not feature a prefix.

The -e ending in the sg. 2 present indicative, and the -es ending in the sg.3 present indicative are features specific to the Northern dialect (Brinton & Bergs, 2017). Like the endings from Table 5, discussed in the Section 5.4., these endings occur under certain

morphosyntactic conditioning, and they furthermore vary depending on “the category and adjacency to the verb of the subject” (Brinton & Bergs, 2017, p. 158).

5.6. Synchronic comparative discussion

As mentioned in Section 2.2., Domingue (1977) argued that contact with AN caused the English language to become more analytic in the ME period. If this would have been the case, there should arguably be more signs of leveling in the London dialect considering London was the home of the Norman nobility. Nevertheless, the London dialect, as mentioned, seems to correspond to the OE conjugations. London thus differs the most from the West Midlands, where only one form is used to express anything in the present tense. This entails that the language in the West Midlands had - as Allen (1995) had already found evidence of - become more analytic. Trudgill (2010) noted that ON influence likely caused morphological leveling in the Midlands and Northern dialects. Thus, the more advanced leveling in the West Midlands, as compared to London, supports that ON was a catalyst of the morphological decay in OE. However, Trudgill (2010) also emphasized the role of Celtic contact in the simplification of OE morphology and cites Dixon who said that contact between two closely related languages does not provide many opportunities for borrowing of grammatical forms. Trudgill (2010) argued that contact with ON caused simplification of morphology but not to the same extent as the contact with speakers of Celtic languages, because the Celtic languages were largely different from OE and there would thus have been a greater need for simplification to enable crosslinguistic communication. Hence, since the West Midlands borders on Wales, Trudgill’s (2010) arguments become even more important to consider, and these arguments could furthermore explain the leveling in the Southern dialect as well. However, the scope of the present study does not allow for further elaboration on Celtic contact.

The East Midlands and the North are the dialectal areas that experienced the most extensive and intimate linguistic contact with ON. The Northern dialect has the most solid evidence of ON influence in the past participle getin, which only differs from the ON past participle by the additional <n> in ON getinn. Both the Northern and the East Midlands dialect lacks the OE ge- or ME y- prefix in the past participle; a prefix that the present study furthermore only found in London. The speaker communities of AN and OE in London were, as discussed in Section 1.4, separated by social class. The more distinct stratification in London could thus explain why an OE prefix could remain in the language as the lack of crosslinguistic communication did not create a need for such prefixes to be leveled out.

As seen in Table 1, all the ME dialects mark 1st preterite with the vowel alternation from <e> to <a>. Both OE and ON featured this alternation,and that is also a plausible reason as to why the alternation remained in all dialects regardless of the extent and nature of contact between OE and ON in the respective areas. Moreover, the inheritance of this feature will be elaborated on from a cognitivist perspective in the following subsection.

5.7. Cognitivist perspectives

As discussed in the introduction, the present study sought to explore contact-induced morphological change by tying Cognitivist theories to contact phenomena such as interlingual identification (Weinreich, 1976). In the synchronic comparative discussion, the vowel alternation from <e> to <a> was mentioned, and how both the OE and ON ablaut grades featured it. The vowel alternation can in accordance with the Construction Morphology-framework be thought of as a form, and the past tense it denotes would in turn be its meaning. In other words, the past tense vowel alternation was an interlingually identifiable construction; and that furthermore allowed for get to retain its strong pattern of conjugation. Another interlingually identifiable construction is the past participle suffix: -en or -in. Since the construction/suffix attached to all classes of strong verbs in both OE and ON, it was a high frequency construction with a consequently strong cognitive representation, much like the -ed suffix discussed by Bybee & Becker (in Bowern & Ewans, 2015). Moreover, as mentioned in Section 2.3., Onysko (in Zenner et al. 2019) argued that morphological patterns became part of the neural activation pathways when they were borrowed into a language. If the morphological pattern, or in this case the morphological construction, already existed in both languages, there would be no need to borrow that construction. The form of the mutually intelligible construction would already successfully have triggered the same cognitive representation, thus also eliminating the need to discard the construction. The results suggest that the inheritance of certain morphological constructions is largely dependent on interlingually identifiable constructions. In other words, it seems as if the interlingually identifiable constructions are what make it through the morphological leveling, whereas the differing constructions are eliminated – consequently simplifying the morphology of the language.

6. Conclusion

The present study sought to explore language contact as a cause of morphological loss in ME. Emphasis was laid on the contact between speakers of OE and ON, and, furthermore, how the mutual intelligibility of these languages affected the outcomes of the contact. The results suggest that ON impacted how get was conjugated, because the dialects that had not experienced ON influence used forms that corresponded to the OE system rather than ON. The most striking similarities with the ON forms were found in the Northern dialect, where the past participle was nearly identical to the ON equivalent. The results thus further confirm what Trudgill (2010) claimed: that morphological leveling started earlier and seems to have occurred at a quicker rate in dialects that experienced ON influence. While the results correspond with those from previous studies, they also provide an answer to the second RQ: “What differences and/or similarities are there between areas that were settled by Scandinavians versus areas that

were not, regarding the infinitive and conjugated forms of get?” The similarities lie mostly in the vowel alternations. Both the ON and OE system marked the 1st preterite

with a shift from <e> to <a> in the stem. In turn, all ME dialects have a 1st preterite form with <a> in the stem, and the only form that stands out in this group is the Southern form which has an initial <ʒ>. This in extension answers the first RQ: “What features did get inherit from the OE and/or ON conjugational systems?”. In short, the ME, as well as the contemporary, paradigm of get has inherited the past tense construction with a vowel alternation from <e> to <a>, which was found in both the OE and ON systems. The vowel alternation is thus derived from both OE and ON. The past participle -en suffix also derives from both ON and OE; however, this feature is regarded as dialectal or informal in contemporary English. Moreover, as observed in Table 5, the past participle form gotten has an <o> stem whereas the other dialects have an <e> stem. The inconsistent use of the <o> suggested that there was an ongoing shift as the letters it occurred in were written. Nevertheless, this shift caused the stem to take on the form it has in the contemporary ablaut pattern.

The differences between the dialectal forms are more numerous. Certain morphosyntactic conditioning caused a final -s, -e, or -th to appear in the East Midlands and Northern dialects. Moreover, the forms in the Northern dialect correspond well with the ON system, which is expected considering the influence of ON as both adstrate and superstrate to OE in the region. As discussed at the beginning of this section, the Northern past participle was nearly identical to the ON equivalent. In contrast, the past participle in the London dialect had retained the prefix that was used to mark past participle in OE, although in a reduced form. Moreover, the London-dialect was - based on Lutz’s (2017) evidence regarding the late arrival of ON loans - treated as unaffected by ON. The assumption that ON had not influenced the London-dialect seems to be correct, as all the forms seem to be directly derived from the OE forms. Furthermore, based on previous research and the present results, it seems as if AN had not caused significant impact on the inflectional morphology in the London-dialect. Had contact with AN caused simplification of inflectional morphology, London would arguably have been the area where the earliest signs of such changes would show.

Interlingual identification (Weinreich, 1979) was considered from a Cognitivist perspective, and the results suggested that the interlingually identifiable constructions had potential to occur frequently in both OE and ON. Frequently occurring constructions have been found to have stronger cognitive representations, and this could explain why constructions like the past participle -en suffix were kept in the English language. The past participle -en suffix was an interlingually identifiable construction that furthermore had an equally strong cognitive representation in both speaker groups; in other words, a form that was found in both OE and ON would trigger the same cognitive representations in both speakers in crosslinguistic communication, and the form did thus not need to be eliminated.

Based on the present results and discussion, the possibly most intriguing theory to explore further would be the koinézation that possibly took place between OE and ON. Convincing evidence of such a process was discussed by O’Neil (2019), and the results

of the present study imply that the similarities of the languages and the role they played in the contact between the two should be held at an even greater importance in future studies. Similarities and relatedness furthermore explain why get has retained its strong pattern of conjugation. As mentioned in Section 1., Carstairs-McCarthy (2018) wrote that borrowings in English most often take on weak forms. The survival of a strong conjugation pattern seemingly relying on interlingual identification of the ablaut gradation makes the koinézation theory even more intriguing.

In conclusion, the results of the present study indicate that interlingual identification of morphological constructions is the key to understand the process of morphological leveling that occurred as a consequence of Anglo-Scandinavian language contact. Further studies could possibly focus on finding additional constructions that were interlingually identifiable and take a quantitative approach to the matter that would allow for more generalizations based on the qualitative elements that have been explored in the present study.

References

Primary sources

Cursor Mundi, (Ed.) R. Morris, Early English Text Society, Original Series 57 (1874;

reprint 1961); 59 (1875; reprint 1966); 62 (1876; reprint 1966); 66 (1877; reprint 1966); 68 (1878; reprint 1966) retrieved 2020-12-18 from

http://name.umdl.umich.edu/AJT8128.0001.001 last visited at 2020-12-18

Middle English Dictionary. (n.d.). Geten, v.(1). In Middle English Compendium (online edition). Retrieved 2020-12-18 from https://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/middle-

english-dictionary/dictionary/MED18489/track?counter=1&search_id=4871814

Paston Letters and Papers of the Fifteenth Century, (1971, 1976). (Ed.) N. Davis.

Oxford Clarendon Press. Retrieved 2020-12-18 from

http://name.umdl.umich.edu/Paston

Sir Tristrem, (Ed.) G. P. McNeill, Scottish Text Society Publications 8 (1886) Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, (1967). (Eds.) J. R. R. Tolkien and E. V. Gordon;

2nd ed., rev. N. Davis. Retrieved 2020-12-18 from

http://name.umdl.umich.edu/Gawain

The Lay of Havelok the Dane, (Ed.) W. W. Skeat, Early English Text Society, Extra

Series 4 (1868; reprint 1903) Retrieved 2020-12-18 from

http://name.umdl.umich.edu/AHA2626.0001.001 last visited at 2020-12-18

The Canterbury Tales, Geoffrey Chaucer, in The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer (1957)

Houghton Mifflin. Retrieved 2020-12-18 from

http://name.umdl.umich.edu/CT

The Text of the Canterbury Tales (1940). (Eds.) J. M. Manly and E. Rickert William of Palerne: An Alliterative Romance (1985). (Ed.) G. H. V. Bunt

Figures

Figure 1: Map showing the geographical division of the Middle English dialects. From Harvard’s Geoffrey Chaucer Website, Harvard University. Retrieved 2020-12-17 from https://chaucer.fas.harvard.edu/pages/middle-english-dialects

Secondary sources

Allen, C. (1996). Middle English case loss and the ‘creolization’ hypothesis. English

Language & Linguistics, 1(1), 63-89, DOI:

https://doi-org.ezp.sub.su.se/10.1017/S1360674300000368

Bailey, C. J. & Maroldt, K. (1977). The French lineage of English. In Jürgen Meisel (ed.), Langues en contact: Pidgins, creoles, 21–53, Tübingen: TBL. Barber, C, Beal, J. C. & Shaw, P. A. (2011). The English language: A historical

introduction (2nd ed), Cambridge University Press.

Barnes, M. (2008). A new introduction to Old Norse: 1 Grammar. (3rd ed), Viking Society for Northern Research.

Booij,G. (2013) Morphology of Construction Grammar. In Hoffmann, T. & Trousdale, G. (Ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Construction Grammar DOI:

10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195396683.013.0014

Bowern, C. & Ewans, B. (2015). Routledge handbook of historical linguistics. Routledge.

Brinton, J. & Bergs, A. (Ed.). (2017). Old English. De Gruyter Mouton. DOI:

https://doi-org.ezp.sub.su.se/10.1515/9783110525304

Brinton, J. & Bergs, A. (Ed.). (2017). Middle English. De Gruyter Mouton. DOI:

https://doi-org.ezp.sub.su.se/10.1515/9783110525328

Carstairs-McCarthy, A. (2018). An introduction to English morphology (2nd ed). Edinburgh University Press.

Cole, M. (2014). Old Northumbrian Verbal Morphosyntax and the (Northern) Subject

Rule. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Dalton-Puffer, C. (1995). Middle English is a creole and its opposite: On the value of plausible speculation. In Fisiak, J. (Eds.). (2010). Linguistic Change under

Contact Conditions. De Gruyter Mouton. doi:

https://doi-org.ezp.sub.su.se/10.1515/9783110885170

Dance, R. (2014). Getting a word in: Contact, etymology, and English vocabulary in the 12th century. Journal of the British Academy.

Dance, R. (2018). Words derived from Old Norse in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: An etymological survey: Volume 1 & 2. Transactions of the Philological

Society, 116(2), 1–238, DOI: 10.1111/1467-968X.12148_01

De Haas, N. & Van Kemande, A. (2014). The origin of the Northern Subject Rule: subject positions and verbal morphosyntax in older English. English

Language and Linguistics, 19(1), 49-81, Cambridge University Press,

DOI: https://doi-org.ezp.sub.su.se/10.1017/S1360674314000306

Dickins, B. & Wilson, R. M. (Ed.). (1951). Early Middle English texts. Bowes & Bowes.

Domingue, N. Z. (1977). Middle English: Another creole? Journal of Creole Studies 1. 89–100.

Greenblatt, S. (Ed.). (2018). The Norton Anthology of English Literature: The Middle

Ages. (10th ed) W.W. Norton & Company.

Hock, H. H. (1986). Principles of Historical Linguistics. De Gruyter Mouton. Lass, R., & Laing, M. (2010). In celebration of Early Middle English 'H'.

Neuphilologische Mitteilungen, 111(3), 345-354. Retrieved January 21,

2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/43344720

Lupack, A. (1994). Lancelot of the Laik and Sir Tristrem, Medieval Institute Publications.

Lutz, A. (2017). Norse loans in Middle English and their influence on late medieval London English. Anglia 135(2), 317-357, DOI:

https://doi-org.ezp.sub.su.se/10.1515/ang-2017-0028

Mailhammer, R. (2007). The Germanic strong verbs: Foundations and development of

a new system. De Gruyter Mouton, DOI: https://doi-org.ezp.sub.su.se/10.1515/9783110198782

Meecham-Jones, S. (2017). Code-switching and contact influence in Middle English manuscripts from the Welsh Penumbra – Should we re-interpret the evidence from Sir Gawain and the Green Knight?". In Multilingual

Practices in Language History. De Gruyter Mouton. DOI: https://doi-org.ezp.sub.su.se/10.1515/9781501504945-006

Mitchell, B. & Robinson, F. C. (1992). A guide to Old English (5th ed). Blackwell. O’Neil, D. (2019). The Middle English creolization hypothesis: Its persistence,

implication, and language ideology. Studia Anglia Posnaniensia, 54(1), 113-132, DOI: https://doi.org/10.2478/stap-2019-0006

Onysko, A. (2019). Reconceptualizing language contact phenomena as cognitive processes. In Zenner, E., Backus, Ad, & Winter-Froemel, E. (Eds.). (2019). Cognitive Contact Linguistics. De Gruyter Mouton. DOI:

https://doi-org.ezp.sub.su.se/10.1515/9783110619430

Oxford English Dictionary. (1989). Get, v. In Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Retrieved 2020-12-18 from https://www.oed.com/oed2/00094176 Robinson, O. W. (1992). Old English and its closest relatives: A survey of the earliest

Germanic languages. Stanford University Press.

Roig-Marin, A. (2018). When the vernaculars (Anglo-Norman and Middle English) and Medieval Latin fuse into a functional variety: Evidence from the

administrative realm. Studia Neophilologica 90(2), 176-194, DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1080/00393274.2018.1482781

Skeat, W. (Ed.). (1867) William of Palerne

Trudgill, P. (2010). Investigations in sociohistorical linguistics: Stories of colonization and contact, Cambridge University Press. DOI:

https://doi-org.ezp.sub.su.se/10.1017/CBO9780511760501

Weinreich, U. (1979). Languages in contact, De Gruyter Mouton, DOI: https://doi-org.ezp.sub.su.se/10.1515/9783110802177

Winters, M. E. (2014). Lexical Layers. In Taylor. J. R. (Eds.). (2014) The Oxford

Handbook of the Word, DOI:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199641604.013.38

Zenner, E., Backus, Ad, & Winter-Froemel, E. (Eds.). (2019). Cognitive Contact

Linguistics. De Gruyter Mouton. DOI: https://doi-org.ezp.sub.su.se/10.1515/9783110619430

Stockholms universitet 106 91 Stockholm Telefon: 08–16 20 00