Malmö University

Culture and Society

Urban Studies

Master Programme Leadership for Sustainability (SALSU)

The Modern-Day Radical Environmental

Movement

A case study of the goals and organisational structure of a radical

environmental group

Name and Code of the course

OL646E – Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organisation for Sustainability

Name and Code of the Examination

Master Thesis – 1201

Type and Date of Examination

Regular Examination 29/05/2020 Björn SCHEENSTRA, 22/07/1994 Stephanie PRAGASTIS, 26/05/1993 Responsible Teacher Hope WITMER Supervisor Jonas LUNDSTEN

1

Thesis title: The Modern-Day Radical Environmental Movement: a case study of the goals and organisational structure of a radical environmental group

Authors: Björn Scheenstra, Stephanie Pragastis

Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organisation for Sustainability Supervisor: Jonas Lundsten

29th of May 2020

Malmö University Culture and Society, Urban Studies Main field of study: Leadership and Organisation

Degree of Master of Arts (60 credits) with a Major in Leadership and Organisation.

2

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank several people for their help and support over the past weeks. First of all, we express our gratitude to Jonas Lundsten for his guidance and the feedback he gave as supervisor for this thesis. Also, many thanks to our fellow students, family and friends for their valuable input, motivational support and snack provisions. And thanks to SemSem for being our adorable emotional support.

3

Abstract

Background – A steep rise in citizen engagement in the environmental activist movement

following concerns about climate change and environmental destruction has led to the formation of a multitude of environmental activist organisations. These organisations encompass different ideological beliefs and doctrines and can be categorised on a broad spectrum. The radical environmental

component of this movement has manifested various organisations which advocate sweeping socio-political change to bring about improvement in the natural environment, often working with non-institutional or non-electoral methods that may or may not include illegal, non-democratic or violent action.

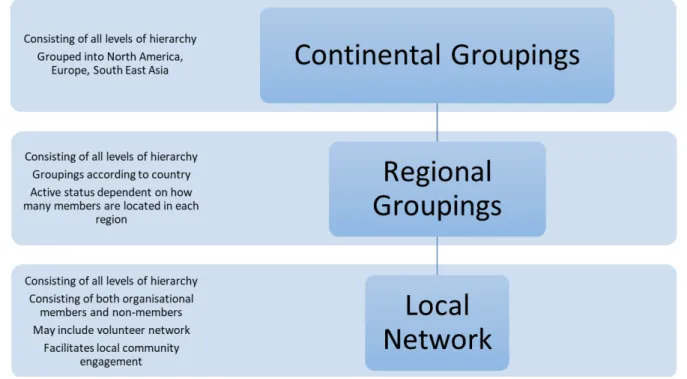

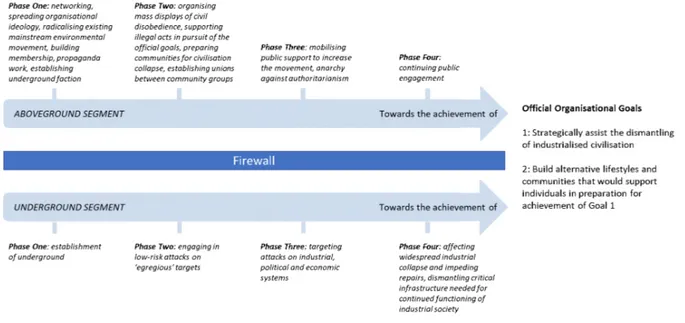

Objective – The purpose of the study is to ascertain the organisational goals and structures of a currently active radical environmental organisation. The research uses the field of organisational studies as a framework to examine these goals and structures. There is a marked lack of previous research focusing on current iterations of radical environmental organisations, therefore this research aims to provide an example of an active organisation as part of the current movement. Methods – A single-embedded case study of a radical environmental organisation was conducted to gather data. Two units of data collection were used; semi-structured interviews with members of the organisation, and content collection from the organisation’s website. Inductive methods of content analysis were applied to gathered data in order to infer results and answer the research questions. Conclusion – Based on findings, we conclude that the radical environmental group investigated has ideological goals that are in line with the personal goals of its members, which includes the overall aim of bringing down industrial civilisation in order to effectuate improvement to the natural environment. The organisation also has a distinct four-phase strategy to define its operative goals. The organisation is structured in a three-tiered hierarchy with formalised rules and procedures for members to adhere to, however, not all functions and activities of the organisation are dictated by this hierarchy and formalisation. The organisation is spatially and horizontally complex, with multiple job titles and global dispersion.

Keywords – radical environmental organisation, activism, environmentalism, sustainability, organisational structure, organisational goals, operative goals, personal goals

4

Contents

1. Introduction ... 8

2. Background ... 9

2.1. Definitions of Radical Environmental Groups ... 9

2.2. Application of Definitions to Scope of Research ... 10

2.3. Historical Background: Beginnings and Developments of the Environmental

Movement ... 10

2.4. Emergence of Radical Groups ... 11

2.5. The Earth Liberation Front ... 11

2.6. The Decline of the ELF ... 12

2.7. Radical Environmental Groups’ Resurgence in the Current Day ... 12

3. Research problem ... 14

4. Research aim ... 14

5. Research Questions ... 15

6. Previous research ... 16

6.1. Goals of the Radical Environmental Organisations ... 16

6.2. Structures of the Radical Environmental Organisations ... 17

6.2.1. Traditional Hierarchical ... 17

6.2.2. SPIN Structure ... 17

6.2.2.1.

Segmentary ... 17

6.2.2.2.

Polycentric ... 17

6.2.2.3.

Integrated Network ... 18

6.2.3. Leaderless Resistance ... 18

7. Theory ... 19

7.1. Goals ... 19

7.1.1. Types of goals ... 19

7.1.1.1.

Organisational and Personal goals ... 19

7.1.1.2.

Official and Operative goals ... 20

7.1.2. Characteristics of goals ... 20

7.2. Goals and Structure – Two Perspectives on Organisations ... 21

7.3. The Key Dimensions of Structure ... 21

7.3.1. Complexity ... 22

7.3.1.1.

Horizontal Complexity ... 22

7.3.1.2.

Vertical Complexity ... 22

7.3.1.3.

Spatial Complexity ... 22

5

7.3.3. Centralisation ... 23

7.3.4. The Relation between Complexity, Formalisation and Centralisation ... 23

8. Methodology ... 25

8.1. Ontology, Epistemology and Scientific approach ... 25

8.2. Research Design ... 25

8.3. Methods and Methodology ... 26

8.3.1. Case Sampling ... 26

8.3.1.1.

Case Sampling Criteria ... 26

8.3.1.2.

Case Sampling Process ... 26

8.3.2. Methods for Data Collection ... 26

8.3.2.1.

Semi-Structured Interviews ... 26

8.3.2.1.1.

Sampling of Interviewees ... 27

8.3.2.1.2.

Interview Guide ... 27

8.3.2.1.3.

Advantages and Disadvantages of the Method ... 27

8.3.2.2.

Content Collection ... 28

8.3.2.2.1.

Selection of the Content Collection ... 28

8.3.2.2.2.

Advantages and Disadvantages of the Method ... 28

8.3.3. Methods of Data Analysis ... 29

8.3.3.1.

Content Analysis ... 29

8.4. Validity ... 30

8.5. Reliability ... 31

8.6. Limitations ... 31

8.6.1. Objectivity of Researchers ... 31

8.6.2. Representations of Organisation ... 31

8.6.3. Scope of Research ... 32

8.6.4. Identification of Goals ... 32

8.6.5. Communication Method ... 32

8.6.6. Further Limitations ... 32

8.7. Presentation of Object of Study ... 33

9. Results and Analysis ... 34

9.1. Goals ... 34

9.1.1. Organisational Goals ... 34

9.1.1.1.

Official Goals ... 34

9.1.1.1.1.

Prioritisation ... 34

6

9.1.1.1.3.

Evaluation Type ... 35

9.1.1.1.4.

Ownership ... 35

9.1.1.1.5.

Hardness ... 35

9.1.1.1.6.

Negotiability ... 35

9.1.1.2.

Official Operative Goals ... 36

9.1.1.2.1.

Prioritisation ... 36

9.1.1.2.2.

Horizon ... 37

9.1.1.2.3.

Evaluation type ... 37

9.1.1.2.4.

Ownership ... 37

9.1.1.2.5.

Hardness ... 37

9.1.1.2.6.

Negotiability ... 38

9.1.1.3.

Unofficial Operative Goals ... 38

9.1.2. Personal Goals ... 38

9.1.2.1.

Ideological Goals ... 38

9.1.2.2.

Practical Goals ... 38

9.2. Structure ... 39

9.2.1. Formal Structure ... 39

9.2.1.1.

Distinct Hierarchy on Three Levels ... 39

9.2.1.2.

Regional Groupings ... 39

9.2.1.3.

Central Organiser ... 39

9.2.1.4.

Numbers of Members ... 40

9.2.1.5.

Aboveground vs Underground ... 40

9.2.2. Informal Structure ... 41

9.2.2.1.

Hierarchical Structure, Egalitarian Functioning ... 41

9.2.2.2.

Informal Leaders in Groups ... 41

9.2.2.3.

Informal Community Outreach and Inter-Organisational Networks ... 42

9.2.3. Complexity ... 42

9.2.3.1.

Horizontal complexity ... 42

9.2.3.2.

Vertical complexity ... 43

9.2.3.3.

Spatial complexity ... 43

9.2.4. Formalisation ... 43

9.2.4.1.

Code of Conduct ... 44

9.2.4.2.

Other guidelines ... 44

9.2.4.3.

Application Process ... 44

9.2.4.4.

Promotion Process ... 45

7

9.2.4.5.

Formalisation in the Day-to-Day Practices ... 45

9.2.4.6.

Non-Compliance to Rules, Guidelines and Processes ... 45

9.2.5. Centralisation ... 46

9.2.5.1.

Centralisation and Formalisation ... 46

9.2.5.2.

Decision-Making Based on Discussion and Consensus ... 46

9.2.5.3.

Individual autonomy ... 47

10.

Discussion ... 48

10.1.

SRQ 1 What are the goals of a currently operating radical environmental

organisation and its members? ... 48

10.1.1.

Official Organisational Goals ... 48

10.1.2.

Official Operative Goals ... 49

10.1.3.

Unofficial Operative Goals ... 49

10.1.4.

Personal Goals ... 49

10.2.

SRQ 2 How is a currently operating radical environmental organisation structured?

50

10.2.1.

Formal structure ... 50

10.2.2.

Informal structure ... 50

10.2.3.

Complexity ... 50

10.2.3.1. Horizontal complexity ... 50

10.2.3.2. Vertical Complexity ... 50

10.2.3.3. Spatial complexity ... 51

10.2.4.

Formalisation ... 51

10.2.5.

Centralisation ... 51

10.3.

Relation to Previous Research ... 51

10.3.1.

Goals ... 51

10.3.2.

Structure ... 52

11.

Conclusion ... 53

12.

Reference list ... 54

8

1. Introduction

History is made by active, determined minorities, not by the majority, which seldom has a clear and consistent idea of what it really wants. Until the time comes for the final push toward revolution, the task of revolutionaries will be less to win the shallow support of the majority than to build a small core of deeply committed people

- Ted Kaczynski, ’The Unabomber’, 1995 In recent years, concerns about climate change, sustainability and environmental destruction associated with the Anthropocene era have been propelled to the forefront of international political debate. Varied citizen responses have ensued— one of the largest being a steep increase in citizen activism and environmental activist organisations; across the world, climate strikes and marches have amassed millions of participants from diverse backgrounds and groups, and global environmental activism has become part of the mainstream, with a large media attention devoted to it (Laville & Watts, 2019). These movements are taking a proactive role in spreading awareness and influencing public opinion, especially within the field of sustainability (Heyes & King, 2020). Within this activist movement however, activism encompasses different ideological beliefs and doctrines and can be categorised on a broad spectrum, with groups and organisations formed to reflect this. The radical faction of the environmental activist movements manifests notably different strategies from the mainstream movement; underpinned by philosophies that can be described as extremist or even terrorist, often embodying an aboveground and underground movement (Posłuszna, 2015). Within the debate around ecological sustainability, these groups advocate a highly alternative approach to that of the mainstream. Many of these organisations were not established recently, however the current political climate and debate around environmental destruction has provided ample impetus for recruitment of new members, with groups reporting an increase in levels of engagement (Bartlett, 2017). Although the movement does not appear to be as ‘extreme’ in its tactics as it did in its heyday (with the most active groups in the 90s and early thousands described by law enforcement in the United States as ‘the most dangerous domestic terrorism threat’ (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2002)), the radical environmental (RE) movement continues to operate, often engaging in illegal methods of direct action to protest. Furthermore, international law-enforcement has recently directed attention towards some of the largest mainstream activist organisations due to perceived threat to security, and scholars theorise that some of these groups have the potential to move towards more radical ideologies and strategies (Grierson & Scott, 2020; Nagtzaam, personal communication, April 16, 2020).

The following study will examine the organisational structure and goals of a currently operating global RE group. These two perspectives have been chosen due to their foundational underpinning and influence over all processes in an organisation. Furthermore, current scholarly research on RE organisations does not reflect the contemporary movement, thus a substantial gap in research is apparent. An examination of these two perspectives in a current RE organisation will therefore provide a starting point in researching this phenomenon.

9

2. Background

In this chapter, a working definition for the topic (group of interest) of this thesis will be presented, and an overview of the historical development of the radical environmental movement (including the current day) will be given in order to show the relevance of this study. This will be done to position the research aim and problem in a broader context.

2.1. Definitions of Radical Environmental Groups

In order to limit the scope of our study, it is important to define the groups which will be researched. Our study will gather data on groups that fall under the banner of radicalism within the environmental movement, rather than a mainstream activist group. Furthermore, we use the terms groups and organisations interchangeably, as both are able to have an organisational structure and goals, which is the main focus of our research (Simon-Brown, 1999; Tolbert & Hall, 2016). The term environmental group or organisation also delineates the scope of our research, which is defined as ‘as any national or regional organisation that seeks to bring about improvement in the natural environment’ (Brulle, Turner, Carmichael, & Jenkins, 2007, p. 197).

The ideologies encompassed and actions carried out by radical factions are the central component that differentiates them from the mainstream activist movement, however, within academia and government, the term radicalism is not always clearly defined (Schmid, 2013).

Moskalenko and McCauley (2009) created a distinction between activism and radicalism; according to their research, (mainstream) activism is ‘readiness to engage in legal and non-violent political action’ (p. 240) and radicalism is ‘readiness to engage in illegal and violent political action’ (p. 240). The relationship between both concepts is explained as follow:

...radicalism is a different [than activism] appraisal of the political situation, an appraisal that justifies or even requires political violence as the only possible path to political change. [...] activism and radicalism can be competing responses to a

perceived need for political change. Radicals may or may not want change more than activists, but radicals disagree with activists about how best to bring the desired change. (Moskalenko & McCauleym 2009, p. 255-256)

A limitation to this definition is highlighted by Schmid (2013), who attests that national governments have the power to change national law and therefore can decide what constitutes as legal (activism) and illegal (radicalism); meaning that definitions of the terms radicalism and activism would appear context dependent. Hence, Schmid (2013) created a description of the concept of radicalism, existing out of two elements and not based on legal definitions:

1. Advocating sweeping political change, based on a conviction that the status quo is unacceptable while at the same time a fundamentally different alternative appears to be available to the radical. (p. 8);

2. The means advocated to bring about the system-transforming radical solution for government and society can be non-violent and democratic (through persuasion and reform) or violent and non-democratic (through coercion and revolution). (p. 8)

Hence, Schmid’s explanation highlights that radicalism is distinguished by the ideologies encompassed rather than methods, as ‘the means advocated to bring about the system-transforming radical solution’ could manifest in multiple ways (Schmid, 2013, p. 8).

Furthermore, Derville’s (2005) research draws on radicalism definitions to characterise radical organisations as ‘a group of two or more people who come together in opposition to something in their environment, including threats to the status quo; they work outside of the system to express their objections, influence social goals, or both’ (p. 528). This definition is in line with Schmid’s (2013)

10

explanation of radicalism as an opposition to the status quo. Derville (2005) further distinguishes radical groups from mainstream groups by the goals of the organisation;

Although different activist organisations share common elements, they use different approaches and have different goals. [...] [a] distinction among activist organisations involves the degree of change sought, which determines whether they are more radical or more mainstream on the classification spectrum. (p. 528)

We can infer from this definition that the goals held by radical organisations become a distinguishing factor in differentiating them from mainstream groups. This highlights the importance of understanding the goals of radical organisations, as according to Derville, they are a basic identifying element. This is a motivating factor for incorporating this perspective in our research.

Pickard (2020) applies the idea of radicalism to organisations in the environmental movement. Pickard’s definition of the term radical focuses on the methods used by groups rather than their ideologies. They further juxtapose radical groups with reformist groups (which appear similar to the activist groups defined by Moskalenko and McCauleym (2009)); reformist groups encompass a more moderate approach, preferring traditional electoral political methods of activism, such as lobbying and other institutional methods; whereas radical groups tend towards non-institutional or non-electoral methods like direct action and civil disobedience, which can manifest as violence, although not always. Pickard further distinguishes between formal and non-formal environmental movement organisations; formal groups embodying a set structure and ability to acquire resources via membership fees and fundraising, with an organisational structure that is essentially hierarchical; non-formal groups, conversely, usually take the form of pressure groups, community groups and environmental networks with a leaderless organisational structure and no official membership, thus less access to funds (Pickard, 2020). Under both of these distinctions is the possibility for a group to embody radical environmentalist ideologies (Pickard, 2020). Therefore, according to this definition, radical environmental groups can take the form of both formal or non-formal organisations; for example, in the animal rights movement, PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) would embody a formal organisation, whereas the Earth Liberation Front (often just a ‘banner’ under which individuals organise themselves) would represent an non-formal organisation. Both of these organisations have, at certain points, been labelled as radical, even though their strategies and goals differ greatly (Griffiths & Steinbrecher, 2010; Leader & Probst, 2003). Since these groups are able to embody multiple structures (Pickard, 2020), this highlights the significance in understanding the structures the current iteration of groups within the RE movement manifest. Furthermore, an examination of the structures of formal and non-formal groups provides an in-depth understanding of how they direct their actions and resources towards the achievement of radical environmental goals.

2.2. Application of Definitions to Scope of Research

From the examined definitions above, a working definition of radical environmental groups will be established in order to define the scope of research:

Two or more people advocating sweeping political change to bring about improvement in the natural environment, based on the opposition to something in their environment or to the status quo, working with non-institutional or non-electoral methods that may or may not include illegal, non-democratic or violent action.

This will be used to discern groups that are relevant to the field of our research.

2.3. Historical Background: Beginnings and Developments of the

Environmental Movement

The origins of the environmental movement can be traced back to the second half of the 20th century; however, it was the 1960s that saw ecological consciousness burgeoning within industrial societies, with questions raised around environmental exploitation and economic growth, and issues such as

11

overpopulation, species extinction and pollution at the forefront of this debate (Posłuszna, 2015). Prior to the 1960s, environmental groups focused on ideas of conservation; however, these movements signalled the beginnings of a more holistic and less reactive approach (Posłuszna, 2015). Furthermore, events such as Earth Day in 1970 (in which 20m people in the USA participated), ecological tragedies like the Torrey Canyon oil spill in the UK, and the Limits to Growth report published by the Club of Rome helped propel environmental consciousness into the mainstream (Hoornweg, 2015). This shift in public perception is credited as inspiring the formation of various environmental groups across the North American and Europe which focused on socio-environmental issues; some of the most prominent examples are the Group Against Smog and Pollution (GASP), founded in Pennsylvania, U.S.A. in 1969 and active in lobbying for legislation changes to safeguard air quality (GASP, n.d.) and Greenpeace, founded in Canada in 1969 with the initial objective to stop nuclear weapons testing in Alaska (Greenpeace Australia Pacific, n.d.). Also important to note was there was a proliferation in member numbers in these groups during 1960-1979, reaching the millions (Posłuszna, 2015).

2.4. Emergence of Radical Groups

Among these movements were groups that used more radical methods of activism. These groups were frequently borne out of existing environmental organisations which used more legal, above-ground methods; with some members becoming dismayed with the existing tactics and ideologies behind these movements, opting for a more radical or revolutionary approach to environmentalism (Nagtzaam, 2017). These groups were often structured as ‘self-guided, clandestine, autonomous units’ in order to support the illegal tactics that they employed, such as sabotage (or ecotage), arson, vandalism and various other methods in order to achieve organisational goals (Loadenthal, 2017 p.1). The first groups to adopt this approach were aligned with the animal rights movement, with groups focused on multiple-issue environmentalism emerging later on (Posłuszna, 2015). The most well-known and widely-studied group within the radical environmental movement is the Earth Liberation Front (hereafter ELF), which was inspired by the Animal Liberation Front (hereafter ALF)— a highly active radical animal rights group (Leader & Probst, 2003). The influence of the ELF can be observed today in current radical environmental organisations, and the goals and organisational structures used have provided strong inspiration for presently operating radical environmental groups; Loadenthal (2017) theorises that the expansion of the movement initiated by the organisation contributed to ‘at least 300 similarly styled groups’ found on an international scale’ (p. 2). Furthermore, the bulk of scholarly research around the radical environmental movement has focussed almost exclusively on this group, making their findings foundational in understanding the current iterations of the radical environmental movement.

2.5. The Earth Liberation Front

The Earth Liberation Front was founded in 1992 in England. Members of existing environmental activist organisations (like Earth First!, for example) gradually became dissatisfied with the ‘lessening radicalism’ of their movement and chose to begin their own, with a doctrine more aligned to their personal philosophies (Posłuszna, 2015 p.144). ELF’s ideologies stemmed from two schools of philosophy; biocentrism, or the belief that all organisms on earth are equal and deserve rights; and deep ecology, which advocates for a return to a pre-industrialised society in order to live more harmoniously with the natural environment and return it a state free from the negative impact of humanity (Leader & Probst, 2003).

ELF described itself as an international organisation with a mission to ‘stop the exploitation and destruction of the natural environment’ (Hirsch-Hoefler & Mudde, 2014, p. 591). Facilitation of this mission was realised through both an ecological lens and a wider social lens—consequently, Posłuszna (2015) theorises that the overarching aim from a social perspective for the ELF was the ‘rapid and unconditional abolition of capitalism’ (p. 148). The ELF’s strategy was direct action in the form of economic sabotage (Brown, 2020). The motivation for committing economic sabotage was its efficiency in building towards ELF’s goals; in 2007, Leslie Pickering—a former press office for the NAELFPO quoted:

12

[by] using real direct action in the form of economic sabotage, the ELF is treating what the greedy entities care about: their pocketbooks. By inflicting as much economic damage as possible, the ELF can allow a given entity to decide if it is in its best economic interest to stop destroying life for the sake of profit. (Posłuszna, 2015, p. 149)

The organisational structure of the ELF was one of leaderless resistance (see 6.2.3) (Brown, 2020). Arranged under the ELF banner were a multitude of groups working in a decentralised, anti-hierarchical structure whose main goal was to stop crime perpetrated against the environment through a method of economic sabotage (ecotage) (Loadenthal, 2017). Any individuals who identified with the ELF philosophy were encouraged to join in the movement by forming their own group and committing acts of economic sabotage against industry contributing to environmental destruction under the ELF banner (Loadenthal, 2014). The chosen structure of this group to achieve its organisational goals was highly novel and a central focal point for researchers and furthermore, law enforcement officials in order to discern how the organisation functioned (Posłuszna, 2015). Throughout the group’s history, it claimed millions of dollars in damage to property, targeting ‘entities they believed to be privileging financial profit over environmental preservation’ (Olson, 2018 p. 58); the most well-known direct action perpetrated by the ELF resulted in 26 million USD worth of damage and involved the arson of a ski resort in Colorado in 1998 (Loadenthal, 2014). To claim responsibility from ELF, oftentimes a spray-painted E.L.F. or message from the Elves would be found at destruction sites, the credit claim for this attack then being communicated to the ELF press office for publicity reasons (Brown, 2020).

2.6. The Decline of the ELF

Due to an increase in police intervention and legislation, the majority of radical environmental groups, including the ELF, are not as active as in the past (Nagtzaam, 2017). It is theorised by scholars that the bulk of the ELF movement has been dismantled by law enforcement across the globe (Loadenthal, 2014). The decline of ELF actions can be attributed to the closure of the aboveground ELF Press Office, which was responsible for the organisation’s publicity and became a central communications hub; the shutdown was caused by extensive FBI investigation, which caused the two members of the press office to resign (Brown, 2020). As a result of this, there was no focal point for communication of credit claims, which had an important role in community building, agenda setting and growth of the ELF; according to a former ELF activist: ‘The lack of a press office disaggregates the ELF narrative, erodes the sense of simultaneity, and impedes cells’ efforts to establish community. Incoherence of narrative also complicates recruitment and organizational continuity’ (Brown, 2020, p.248). After the above ground segment of the ELF was cracked down on, the FBI focused on the underground organisation of the ELF, causing a series of arrests in the US which reduced the number of attacks, as the ELF also failed to replace apprehended cells (Loadenthal, 2014).

2.7. Radical Environmental Groups’ Resurgence in the Current Day

Whilst activity under the ELF banner has declined, the environmental movement has amassed numerous other radical groups working with a range of goals that encompass a holistic approach, including anti-capitalist, anti-industrialist, feminist and anti-globalisation ideologies (for example, Individualistas Tendiendo a lo Salvaje (Individualists Tending to the Wild)—a Mexican eco-extremist organisation with a strong anti-technological doctrine (El Líbero, 2019) and Sociedade Secreta Silvestre (Wild Secret Society)—a Brazilian organisation that has been described as ‘ecoterrorist’ for their threatening of ministers (TRAC, n.d.)). Many of these groups operate above-ground with large numbers, however it is impossible to estimate the scope of the underground movement. Furthermore, there has been a resurgence in membership to groups such as Earth First! (which was the precursor and less-radical organisation that the ELF was borne out of) as reported by Bartlett (2017), with long time members quoting that they have ‘never seen this level of interest’. That said, tactics used by currently operating organisations in the radical environmental movement do not appear as extreme as they did previously at their peak in the early thousands and late nineties, when certain radical groups

13

were also given a domestic terrorist organisation status (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2002). Accordingly, there are currently no environmental groups listed as terrorist organisations by the European Union, United States or United Kingdom (Bureau of Counterterrorism, 2020; European Union, 2019; United Kingdom Home Office, 2020).

To take a more mainstream and current approach and to link this to the contemporary context, global environmental activism is on the rise and numbers of participants are proliferating in strikes, marches and protests around the world. One of the most prominent examples of this is the youth activist movement Fridays for Future, which has mobilised millions of environmental activists across the globe and been credited with ‘changing the whole landscape of the climate movement’ (Hockenos, 2020). Activist groups have been proactive in not only bringing environmental issues into mainstream debate, but positioning them at the forefront. Nonetheless, there is a strong indication that global law enforcement perceives a risk of violence or disobedience from current (even mainstream) activist groups—suggesting that ideologies and tactics are shifting towards more radical approaches; for example, in the United Kingdom in January of 2020, the largely popular environmental activist group Extinction Rebellion was listed as a key threat by City of London counter terror police, after a series of high-profile civil disobedience actions which led to the arrest of more than 1000 protestors (Grierson & Scott, 2020). These actions were largely non-violent, however were highly successful in disrupting the economic activity in the city, costing ‘millions in lost productivity’ (Eells, 2020). This key

threat listing was later reconsidered by police, however law enforcement agencies across the city were

delivered counter-terrorism awareness training in direct response to this (Grierson & Scott, 2020).

Though not currently observed on the same scale as the ELF movement, scholars theorise that radicalism in the environmental movement may become a new global phenomenon due to the conditions present in the current global context. Posłuszna (2015) theorises that the phenomenon has a high development potential due to multiple factors; firstly, that groups have developed operational strategies and structures that have a ‘risk-free method’ and are highly impenetrable to law enforcement (p. 223); secondly that the broadly encompassing ideologies represented in the movement mean that potential members can originate from a wide range of areas; thirdly because the advent of new media (such as social media) increases group efficiency and security; and lastly, as the movement is related to other activist movements (such as anti-globalisation), which constitutes more goals and actions across within the RE movement, fuelling motivations to remain active and to develop. Nagtzaam (Personal Communication, April 16, 2020) also speculates that existing global movements have the potential to become more radical, identifying the global Extinction Rebellion movement as having a high potential to move towards more radical tactics and ideologies. As historically, more radical groups and ideologies have formed out of a frustration of members that not enough action was being taken (Nagtzaam, 2017), the slow-moving nature of the global political-environmental landscape appears a potential impetus for a spike in radical environmentalism.

14

3. Research problem

There is little to no data available about currently active radical environmental groups, with research in this field tending to focus on the most active years of the radical environmental movements (the nineties and early thousands), with a focus on groups like the ELF. Our line of research will aim to contribute to this field to provide a snapshot of the current era of radical environmentalism through the lens of organisational studies.

The importance of this research is that it is highly topical in nature. At a time when globally, environmental issues are at the forefront of political and civil engagement, a plethora of groups are taking a proactive role in spreading awareness and influencing public opinion on issues of ecological sustainability; as stated by Heyes and King (2020) ‘Environmental activists have become an important voice in public and private politics, urging governmental and corporate responses and solutions to ongoing environmental damage’ (p. 7). However, among these movements, radical environmental groups are more prominently being identified and, on occasion, being investigated by governments and law enforcement (Algemene Inlichtingen- en Veiligheidsdienst [AIVD], 2013; Grierson, 2020;). Furthermore, individuals are becoming more radical in their efforts to promote and support environmentally responsible behaviour (Nagtzaam, 2017).

Our research will fall at the intersection of organisational studies and radical environmental groups, with a focus on the goals and structures of these organisations. To the researchers’ knowledge, an in-depth examination of structures and goals within RE groups (past and present) has not been merged before from an organisational perspective; rather, this has been undertaken from the frame of political and legal studies. We further see the relevance of applying this frame in that there has been a notable departure by RE organisations from the violent or illegal tactics that were more frequently employed in the past, as detailed in the background section.

Organisational structures and goals have been chosen as the focal point of this research for multiple reasons; firstly, organisations are formed in order to achieve a goal, and striving for the realisation of a common goal provides the impetus for individuals to meet together (MacIver, 1924; Popova & Sharpanskykh, 2011); secondly, goals heavily influence the organisational structure, as these structures signal how to coordinate efforts in pursuit of the goal (Gross, 1969). Furthermore, Heyes and King (2020) theorise that for groups within the scope of activism (including radicalism), goals provide the purpose of the organisation, and this purpose is what ‘binds individuals to organisations’ (p. 11); meaning that the goals of the organisation also appear the impetus for members to join, remain in and sustain the organisation. From this, we can infer that the structure and goals provide a foundational understanding of an organisation, and as little data exists within this field, this research has the opportunity to contribute in building a knowledge base that is seminal in understanding these topics from the lens of organisational studies. This presents an opportune and unique research problem to be investigated.

4. Research aim

The aim of this research is to examine the ways that currently operating radical environmental groups are organised. As stated in our research problem, no data exists on groups that are presently functioning, and scholars and law-enforcement envision a development within this area; therefore, our aim is to contribute to this topical, yet under-researched field. Our research will examine one case of a RE organisation and the empirical data will exist as an example to contribute to the research field. Our study is intended to provide a basis for further research in this field. Moreover, in investigating a radical environmental group through the lens of organisational theory, we want to understand how existing goal and structure theory can be applied outside the context of a traditional ‘work organisation’; or those with employees; and to groups with voluntary membership based on an ideological underpinning (Tolbert & Hall, 2016, p. 3). This will be achieved through researching the organisational structures that underpin a currently operating radical environmental group’s organisational and personal goals.

15

5. Research Questions

Based on the defined scope, our research problem and research aim, the following research question and sub-questions have been identified. The sub research questions will be used to provide two perspectives to answer the overall research question. These questions have been formulated in line with the selected method (see section 8.3) of a single-embedded case study and the aim of the study (to contribute to the currently under-researched field). We aim to gather data that is representative of an example of a RE organisation within the current movement, hence the sub research questions are written in singular form.

RQ: How are currently operating radical environmental organisations organised?

SRQ 1: What are the goals of a currently operating radical environmental organisation and its members?

16

6. Previous research

In this chapter, an overview of the previous research on radical environmental groups in the context of goals and structure will be presented. This will serve as a starting point for the topic of this thesis.

As previously stated, the majority of research conducted on the topic of radical environmental organisations has focused on the late nineties and early thousands, which represents some of the peak active years of the most well-researched radical organisations (Posłuszna, 2015). Therefore, the previous research section is representative of groups that were most active during this time period. There is thus a gap in data corresponding to organisations that were active after this time, which may or may not continue to be active today, and our research will aim to contribute to this.

6.1. Goals of the Radical Environmental Organisations

The radical environmental movement’s overarching goals (that are embodied by various organisations) are described by Leader and Probst (2003) as ‘restoration [of the environment] to its imagined pristine state, … [which] they believe has been despoiled by the selfish actions of the human race’ (p. 40); by Hirsch-Hoefler and Mudde (2014) as ‘realising a world in which the environment is fully respected’ (p. 590); by Posłuszna (2015) as ‘protecting the natural environment’ (p. 11); and by Loadenthal (2017) as ‘opposing violence towards the environment’ (p. 2). Unlike the mainstream environmental movement, these goals are believed to be reached through a process of radical socio-political transformation— accordingly, RE organisations’ goals often encompass themes that concern not only environmental protection, but socio-political goals which usually ‘aim for total changes in the world’ (Posłuszna, 2015, p. 11). For example, Posłuszna (2015) theorises that the overarching aim of the ELF was the ‘rapid and unconditional abolition of capitalism’, as this is perceived by the group as the direct cause of the socio-ecological problems that define its focus (p. 148). Moreover, these aims often facilitate connections with other movements; for example, the ELF had strong ties to the anti-globalisation movement and members were often involved in these via other organisations (Leader & Probst, 2003).

These goals are facilitated through strategies that frequently include direct action, rather than traditional lobbying of reformist environmental organisations (Pickard, 2020); Trujillo (2005) argues that the objective of this direct action ‘is increasingly to influence public opinion and secondary parties, such as the government, upon whom demands can be made’ (p. 147). Groups believe this strategy, which includes violent, anti-democratic and revolutionary means, to be most effective in facilitating overarching goals of the movement (Posłuszna, 2015).

Scholars postulate that organisational goals of RE groups are highly important in organising specific groups and oftentimes function as an organisational structure. Leader and Probst (2003) theorise that the loosely defined, non-hierarchical, leaderless structures frequently employed by RE organisations (see 6.2) make governance seemingly challenging, meaning that organisations rely on defined goals (and members’ understanding of these) to govern individuals’ actions on behalf of the organisation. This highlights the importance of organisational goals within the RE movement and provides further rationale for it to be a focal point of our research.

However, there is a research gap in data relating to the personal goals of members of previous RE movement organisations; to the researchers’ knowledge, data has not been gathered before on this topic. This could be due to the often illegal nature of actions carried out by members, meaning that there would be strong incentive to avoid identification as a member, thus proving difficult to gather data pertaining to individuals. Furthermore, the lack of structure (see 6.2) and banner movements (like the SPIN and leaderless resistance models) further complicates this process, as membership becomes fluid and harder to define, and rests solely on self-proclamation of individuals to establish them as members (Brown, 2020; Gerlach, 1971).

17

6.2. Structures of the Radical Environmental Organisations

Existing theories focused on the organisational structures of RE movement groups have emerged from a variety of fields, such as sociology (understanding these groups as part of a ‘social movement’) or criminology (conceptualizing groups as illegal entities). Furthermore, structures of RE movement organisations have notably shifted over time and in response to changing contexts—for example, technology has been a driving force in adapting organisational structures. The current body of theory therefore may not be representative of RE movement organisations that are active today, as research has typically focused on groups that were most active in the early nineties and thousands.

6.2.1. Traditional Hierarchical

Posłuszna (2015) details organisational structures that are frequently seen amongst radical environmental organisations. Traditionally, structures have been geared towards a hierarchical and centralised structure, with command sitting at the top of a four level pyramid, and subsequent levels fed information from this top layer. The second layer consists of active personnel—those responsible for direct action—however this layer may also involve members of the commanding staff; the third layer comprises active supporters, who are not responsible for direct action, but supply hiding places, communicate information and enable logistics; and the fourth layer is made up of ‘passive supporters’ who merely provide financial and logistical support, do not maintain direct contact with members and are frequently ‘not aware of the fact that they are members of an organization’ (Posłuszna, 2015, p. 156). The degree of formalisation within the pyramid is not specified and can differ between organisations.

6.2.2. SPIN Structure

The SPIN (Segmented, Polycentric and Integrated Network) structure, first detailed by Gerlach (1971), emerges from a sociology perspective and has been used to describe the structure of organisations intrinsically linked to social movements. This type of structure has faced criticism; not only from theorists, but also from movement participants; for being ‘poorly organised and underdeveloped’, with opponents citing its perceived shortage of efficiency as an argument for it to naturally evolve towards a centralized bureaucratic form (Gerlach, 2001 p. 302). However, the structure has proven advantageous in the face of attempted suppression of RE organisations by authorities— in its ability for groups to evolve with new membership, its high adaptability, the permitted division of labour due to multiplicity of groups, and its high system reliability (as failure of one component does not necessarily influence other components) (Gerlach, 2001). The elements of this structure are described below.

6.2.2.1. Segmentary

The organisation is made up of various groups that are highly adaptable and subject to constant change— appearing and disappearing, joining and dividing, expanding and diversifying (Posłuszna, 2015), representing a high level of horizontal and spatial complexity, as the groups are not hierarchical and organisations aim to operate in multiple geographical locations. These groups are semi-autonomous, and members may overlap and be part of multiple groups, with different organisational roles defined for individuals in different groups (e.g. leader or follower) (Gerlach, 1971). Groups divide for varied reasons, such as ideological differences, competition, pre-existing tensions or power structures, and different groups represent different divisions of labour within the same organisation (Gerlach, 2001).

6.2.2.2. Polycentric

This represents total decentralisation and lack of hierarchy. There is no designated leader for the entire organisation, and therefore multiple leaders emerge—sometimes only temporarily or situationally (for example, those leaders invited to talk via the media), sometimes in competition with one another

18

(Posłuszna, 2015). Among these leaders, there is no chain of command to delineate a central hierarchy, person or group responsible for making binding decisions within the organisation (Gerlach, 2001). Bennett (2003) also notes that this is a shift from movements in the past, which were more likely ‘to be defined around prominent leaders’ (p. 147).

6.2.2.3. Integrated Network

Although diverse and highly complex, the organisational groups remain networked to one another in order to ‘exchange information and ideas and coordinate joint direction action’ (Gerlach, 2001, p. 295). This network is not only linked internally or within the organisation, but furthermore, linked to other organisations under different activist movements (Gerlach, 1971). The basis of this network revolves less around ideology and more towards personal forms of association, with members of each group often maintaining personal relationships with other group members, facilitating the network (Bennett, 2003). Other network facilitators include ‘visitors’ to the movement groups, who carry information across the network and across movements, large gatherings such as conventions, and Internet communication technologies (Gerlach, 2001). The integrative component arises from the shared opposition groups hold toward externalities, and the shared ideologies, beliefs and core themes that the organisation encompasses (Gerlach, 2001).

6.2.3. Leaderless Resistance

This model has emerged most recently and represents a total abandonment of formal organisational structures and is almost completely decentralised and non-hierarchical (Posłuszna, 2015).. A loose configuration of small and autonomous cells that are not controlled by any decision-making body represents the bulk of the organisation, with the coalescing element among them being the ideologies, philosophies and spiritualities central to the movement that were also most probably their reason for participation in the first place (Posłuszna, 2015). The aim of this is to reduce the risk of infiltration by law enforcement bodies; however, Leader and Probst (2003) speculate that this then becomes ‘more of an amorphous movement than an organisation in any conventional sense of the word’ (p. 39). That said, groups self-organise under the banner of an activist organisation and therefore declare themselves part of this organisation, which would posit a type of organisation with some semblance of structure. This structure incorporates high horizontal complexity, as quite often cells will become specialised in one form of direct action or embody a certain ideology under the movement (Nagtzaam, 2017); and although almost completely decentralised, usually there is a form of internal communication that can link cells and provide details of other direct actions or attacks perpetrated under the organisation— most often, a website that disseminates this information or publishes ‘credit claims’ (Brown, 2020 p.100). This structure allows for high spatial complexity; with groups having the opportunity to form in locations far from each other; and also rapid expansion; as a complete lack of bureaucracy enables fast membership since activists can simply join by carrying out actions on the organisation’s behalf (Hirsch-Hoefler & Mudde, 2014). This structure was employed by the ELF during its active years (Leader & Probst, 2003).

Layout of the Paper

In the following chapter we will present the theory used in this research in order to interpret gathered data to answer the research questions. After this, in the chapter methodology, the research design, research methods and methodology will be defined. The subsequent chapter will present the research

results and analysis, followed by the chapter discussion in which the research questions will be answered.

19

7. Theory

This chapter will present the theories used in order to fulfil the research aim. Several theoretical concepts and frameworks will be defined and their relevance to the research questions will be explained. These theories will be used to analyse gathered data (see Results and Analysis (9)).

7.1. Goals

Goals are intrinsically linked to the purpose of an organisation; as stated by Popova and Sharpanskykh (2011)— ‘every organisation exists or is created for the achievement of one or more goals’ (p.335). They not only define the orientation of efforts of an organisation, but can be conceptualised as the fundamental marker of the organisation itself; Gross (1969) posits that ‘it is the dominating presence of a goal which marks an organisation’ (p.277). From a sociological perspective, the relationships observed within an organisation are also defined by the attainment of some sort of goal, as their meeting together is in fact the means towards the realisation of that goal, and the relationship would not exist without it (MacIver, 1924).

Etzioni (1964), whose work is considered seminal in organisational goal theory, defines goals as ‘…a desired state of affairs which the organisation attempts to realize‘ (p.6). Goals have several functions within organisations; they provide orientation for members for what the organisations tries to realise, they are a source of legitimacy for the actions of the organisation and perhaps most importantly, they can be used to determine the success of the organisation (Etzioni, 1964).

7.1.1. Types of goals

There are different typologies of goals within organisations. The two typologies of goals that will be examined in our research are official and operative, and organisational and personal. These typologies will be used to delineate key concepts required to answer SRQ 1 and therefore will inform the data collection and analysis methods.

7.1.1.1. Organisational and Personal goals

There is a difference in organisational goals and personal goals. Individuals might have their own reason to work within an organisation and these goals might be different from the organisational goals (Tolbert & Hall, 2016). Some even argue that the organisation’s goals are the intersection of the goals of key participants in the organisation; Cyert and March (1963) explain in their Behavioral Theory of the Firm that organisational goals emerge out of a coalition of different members’ personal goals, such as workers, shareholders, managers and customers. Due to this goal structure, conflicting goals may arise, and often it is important to maintain and streamline the goals of this dominant coalition (Miner, 2006). Cummings (1983) describes an organisation as a mechanism ‘in which participants can engage in behaviour they perceive as instrumental to their goals’, with an understanding of the organisation as a ‘key instrument in fulfilling their needs’ (p. 536), defining organisations from the standpoint of member’s personal goals. However, the differentiation between personal goals and their importance in the goal defining process is imperative to conceptualise, as these may not correspond to the organisation’s goals at all—rather, follow the desired state of affairs for the individual themselves; we cannot assume that personal and group goals will correspond (Gross, 1969). A personal goal, for example, may represent what the individual hopes to achieve for themselves in the organisation—for example, earning money, attaining more responsibility or networking. Gross (1969) also states ‘in the case of ideological organisations, where personal values coincide, there may be a close correspondence between personal goals […] and group goals. Yet in general one cannot assume that personal and group goals will coincide’ (p. 278); this is relevant to the defined scope of the study as RE groups, which exist as an expression of an ideological movement or organisation. This emphasises the importance of personal goals as a foundation for membership in an organisation, which might be a significant impetus for RE organisation participants.

20

7.1.1.2. Official and Operative goals

Another typology of goals within organisations is the distinction between official and operative goals (Etzioni, 1964). Official goals are goals that serve as the general purpose of the organisation—they are abstract and hard to measure, and do not indicate the priority of multiple goals nor the multitude of decisions that need to be made in order to reach them (Perrow, 1961). Operative goals, on the other hand, are the actual goals of organisations; they show the actions an organisation must execute in order to (directly or indirectly) achieve official goals (Tolbert & Hall, 2016). As operative goals give the details of official goals, this also will unmask competing values between goals, as they have the ability to both support one goal and subvert another (Perrow, 1961). Moreover, it is also possible that unofficial operative goals are created as well; these goals may not originate in furtherance of official goals, however are borne out of group interests and personal ambitions of the dominant coalition (Etzioni, 1965; Perrow, 1961).

7.1.2. Characteristics of goals

Popova and Sharpanskykh (2011) created several characteristics of goals as part of a formal framework used in order to model goals based on organisational performance indicators (Table 1). Since it is beyond the scope of our research to gather data on performance indicators, we will only utilise part of the model that relates to goal characteristics. The model is most often referred to in relation to performance indicator monitoring via organisational data, business intelligence and information systems (Bravos et al., 2014; Cardoso, 2013a; Izhar et al., 2017). However, the model is also used in relation to enterprise modelling (or organisational structure modelling) (Cardoso, 2013b; Jonker et al., 2012); we therefore see the ability to apply it to our research. The model proposed by Popova and Sharpanskykh (2011) was developed through previous in-depth goal modelling experience of the authors and ‘inspired by existing goal modeling frameworks’ (p. 339). The characteristics serve as ways to understand the dimensions and specifications of goals, especially those which are defined in a ‘vague and informal way’ (Popova & Sharpanskykh, 2011 p. 340). They will be employed in our research as a framework to dissect the official and operative goals of the organisation and its members (to answer SRQ1). This will provide clarity in classification of data gathered from interviewees and collected content.

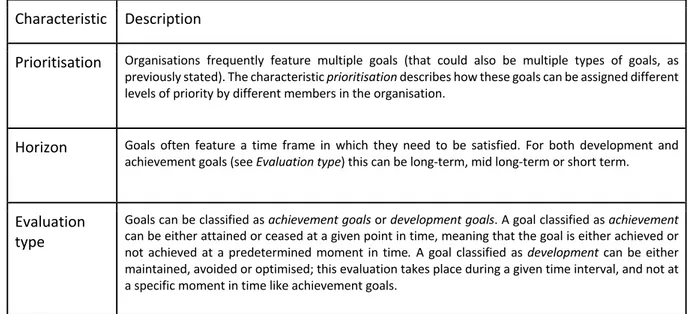

Table 1 Characteristics of Goals (Popova & Sharpanskykh, 2011)

Characteristic Description

Prioritisation Organisations frequently feature multiple goals (that could also be multiple types of goals, as previously stated). The characteristic prioritisation describes how these goals can be assigned different levels of priority by different members in the organisation.

Horizon Goals often feature a time frame in which they need to be satisfied. For both development and achievement goals (see Evaluation type) this can be long-term, mid long-term or short term.

Evaluation type

Goals can be classified as achievement goals or development goals. A goal classified as achievement can be either attained or ceased at a given point in time, meaning that the goal is either achieved or not achieved at a predetermined moment in time. A goal classified as development can be either maintained, avoided or optimised; this evaluation takes place during a given time interval, and not at a specific moment in time like achievement goals.

21

Ownership Goals can belong to the organisation, departments, roles, or individuals within the organisation and may vary according to their ownership. This variety in goal ownership can impact the prioritisation of goals. Normally, organisational goals have a high level of priority.

Hardness The extent to which goal achievement can be quantified is the hardness of goals. There is a distinction between soft goals and hard goals. Hard goals are those whose satisfaction can be quantified; soft goals are those whose satisfaction cannot be quantified and is therefore difficult to define. Satisfaction of hard goals is therefore determined objectively, and soft goals; subjectively.

Negotiability Negotiability expresses the ability to negotiate goals. Goals can be non-negotiable and need to be achieved without compromise, or they can be negotiable; meaning compromises can be made.

The model from Popova and Sharpanskykh includes one characteristic that will not be of use in this research:

-

Perspective: the perspective of organisational goals shows the viewpoint that is described by the goal. Goals can be stated from the viewpoint of different stakeholders, for example, shareholders may state goals as maximising share price, and customers may describe goals as keeping prices as low as possible.This characteristic is not relevant in our research due to the data collection methods, which will only gather data from one type of organisational stakeholder (members) and will not include other internal or external stakeholders.

7.2. Goals and Structure – Two Perspectives on Organisations

The organisational structure functions as a foundational attribute of an organisation and is intrinsically linked to the achievement of the organisation’s goal; on the topic of structure, Merton (1940) states ‘a rationally organised social structure involves clearly defined patterns of activity in which, ideally, every series of actions is functionally related to the purposes of the organisation’ (p. 560). This highlights the importance of the ‘purpose’ of the organisation (which was previously defined as attainment of the goal) in dictating the structures to direct actions and resources, and we can infer that the structures designed by an organisation should be directed towards achieving organisational goals (Gross, 1969).

The organisational structure can be defined two ways— by looking at the formal structure; the ‘explicit organisational specifications’, and the informal structure, which ‘involves norms and social expectations that are not officially prescribed by an organisation, but can be a powerful force in channelling people’s behaviour’ (Tolbert & Hall, 2016, p. 20). The purpose of a formal organisational structure is to ensure consistent and standardised organisational outputs to achieve organisational goals (Tolbert & Hall, 2016). The organisation of these informal/formal structures lead to formalisation, complexity and centralisation, which will be used as key concepts to both collect and characterise data in researching and answering SRQ2.

Thus, we can conceptualise the purpose of the organisation as the striving to achieve organisational goals, and the structure as the facilitator of these efforts towards achieving goals.

7.3. The Key Dimensions of Structure

Complexity, formalisation and centralisation are seen as the three traditional variables of organisational structure (Pertusa-Ortega et al., 2010). These dimensions were first investigated by Mintzberg (1979) as part of the contingency theory of organisations, which claims that there is no optimal way of

22

organising to maximise performance of an organisation (Contandriopoulos et al., 2018; Negandhi & Reimann, 1972). The variables are organisational dimensions on their own, which also interact and influence each other (Tolbert & Hall, 2016).

7.3.1. Complexity

Complexity is most often expressed as the range of specialisations or job titles within an organisation. These different sub-parts within an organisation require coordination, which is more complex when an organisation has more job-titles or roles (Tolbert & Hall, 2016).

According to Baccarini (1996) and Beyer and Trice (1979), complexity can be divided in horizontal differentiation and vertical differentiation. The former entails the division in departments, tasks or units, while the latter focuses on the hierarchical depth of an organisation. Hall et al. (1967) adds spatial dispersion, also known as spatial complexity, as another level of complexity. They argue that distance from an organisation’s headquarters or the dispersion of physical locations also leads to complexity.

7.3.1.1. Horizontal Complexity

Horizontal complexity emerges from tasks that are divided over different jobs or departments. Individuals might specialize and therefore there are a higher number of jobs or departments within an organisation (Baccarini, 1996; Tolbert & Hall, 2016). This is efficient, as people are specialised in the work they do, and they can innovate within their field; however, it takes more time to control and coordinate activities within an organisation (Tolbert & Hall, 2016). Hall et al. (1967) also indicate that a higher number of organisational goals can lead to horizontal complexity.

One way of measuring horizontal complexity is counting the number of job titles within the organisation (Tolbert & Hall, 2016). Other ways of expressing horizontal complexity is looking at the training and specialisations of employees within the organisation (Hage & Aiken, 1967; Tolbert & Hall, 2016):

The more specialised occupational training people have, the more they differ in the knowledge bases that they use in their work from others who might have similar amounts of training but in different occupations. Such specialisation often requires extra effort for the individuals to communicate and coordinate their work. (Tolbert & Hall, 2016, p.44)

Thus, horizontal complexity can be defined in various ways. 7.3.1.2. Vertical Complexity

Vertical complexity, or hierarchical complexity, is caused by organisational hierarchy; the division in decision making and supervisory roles. The deeper the hierarchy, the more complex an organisation becomes (Baccarini, 1996; Hall et al., 1967; Tolbert & Hall, 2016). There are different measures for this, such as the number of levels within an organisational structure, or the number of levels between the CEO and the employees working on output (Hall et al., 1967; Pugh et al., 1968). Vertical complexity, often referred to as differentiation, is linked to the dimension centralisation (see 7.3.3) (Tolbert & Hall, 2016).

7.3.1.3. Spatial Complexity

Spatial complexity arises from geographical dispersion. When an organisation has different physical locations, complexity both vertically and horizontally can occur; different tasks are executed at different locations or decision-making power lies in different locations (Hall et al., 1967; Tolbert & Hall, 2016). Spatial complexity might also occur when ‘…organisations create separate establishments in

23

different locations that all do the same kinds of tasks’ (p.45), for example within a retail chain (Tolbert & Hall, 2016). The most used measures of spatial complexity are counting the number of locations or the number of employees not working at the head office. Advantages of spatial complexity is the possibility to make use of resources over a wider area. Customers, employees and resources on different locations can be served or utilised. A disadvantage, however, is coordination and control, in other words, increased complexity (Tolbert & Hall, 2016).

7.3.2. Formalisation

Formalisation is the extent to which procedures, tasks and assignments within an organisation are codified or made permanent and influence decision making; this can be the written rules people have to follow in executing tasks which can help in reducing the variation in work outcomes (Fredrickson, 1986; Tolbert & Hall, 2016). Hage and Aiken (1967) make a distinction between having rules within an organisation and following these rules—this difference indicates two different ways of measuring formalisation: by counting the number of rules (job codification) or by measuring whether rules and policies are adhered to (rule observation) (Tolbert & Hall, 2016).

The advantages of a high level of formalisation is a lower variability in outcomes, as behaviour is set in rules; secondly, it is easier to train new members/followers of the organisation because their expected work is codified in rules; furthermore, it can enhance equity in treatment of members/followers (Hall et al., 1967; Tolbert & Hall, 2016). Disadvantages, however, are the risk of creating so many procedures and rules that limit the flexibility as a leader to influence members/followers, as well as slowing the production process and limiting innovation because following work processes is favoured over experimentation (Tolbert & Hall, 2016).

7.3.3. Centralisation

The degree to which decision-making power and responsibility about planning, resource allocation and task execution is distributed among different members/followers is referred to as the level of centralisation (Fredrickson, 1986; Tolbert & Hall, 2016). One measure of centralisation is explained by Blau (1968), who uses a ratio of managers to non-supervisory officials. The assumption is that more managers means a spread in decision-making power, so less centralisation. However, there is a limitation to this measure—when formalisation is high, it means that there are rules dictating actions to take (work procedures are codified). In other words, most decisions are already made, and therefore the level of centralisation is high. Therefore, a high level of formalisation can cause a high level of centralisation (Blau, 1968; Tolbert & Hall, 2016).

The advantages of centralisation are that it is easier to coordinate the organisation as less people are involved in decision making, thus decisions can be made faster. A disadvantage, however, is that decisions made high in the hierarchy might lack information from members lower in the hierarchy necessary to make a well-considered decision; therefore, decisions can be of lower quality (Tolbert & Hall, 2016).

7.3.4. The Relation between Complexity, Formalisation and Centralisation As mentioned earlier, complexity, formalisation and centralisation are connected to each other. Here are two examples to showcase that connection (Pugh et al., 1968; Tolbert & Hall, 2016):