ARTICLES

PUBLISHED ONLINE: 14 AUGUST 2017 |DOI: 10.1038/NPHYS4208

Evidence for light-by-light scattering in heavy-ion

collisions with the ATLAS detector at the LHC

ATLAS Collaboration

†Light-by-light scattering (γ γ → γ γ ) is a quantum-mechanical process that is forbidden in the classical theory of electrodynamics. This reaction is accessible at the Large Hadron Collider thanks to the large electromagnetic field strengths generated by ultra-relativistic colliding lead ions. Using 480 µb−1 of lead–lead collision data recorded at a centre-of-mass

energy per nucleon pair of 5.02 TeV by the ATLAS detector, here we report evidence for light-by-light scattering. A total of 13 candidate events were observed with an expected background of 2.6 ± 0.7 events. After background subtraction and analysis corrections, the fiducial cross-section of the process Pb + Pb (γ γ ) → Pb(∗)+ Pb(∗)γ γ , for photon transverse energy ET>3 GeV,

photon absolute pseudorapidity |η|<2.4, diphoton invariant mass greater than 6 GeV, diphoton transverse momentum lower than 2 GeV and diphoton acoplanarity below 0.01, is measured to be 70 ± 24 (stat.) ±17 (syst.) nb, which is in agreement with the standard model predictions.

O

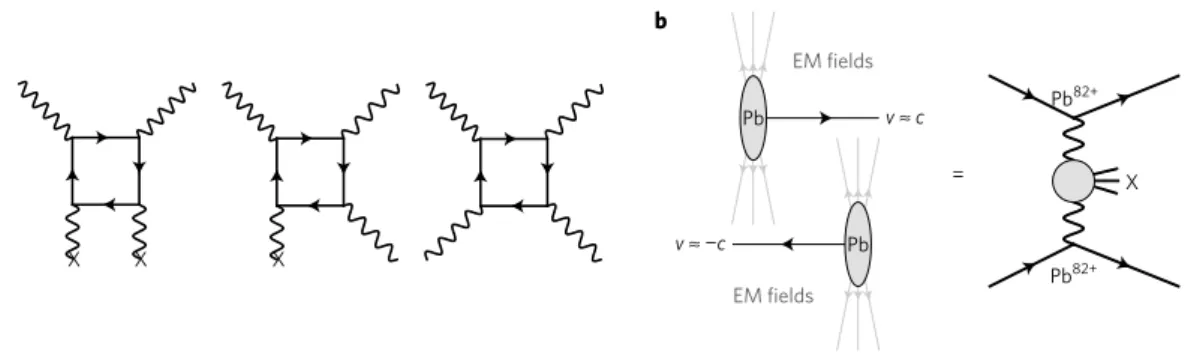

ne of the key features of Maxwell’s equations is their linearity in both the sources and the fields, from which follows the superposition principle. This forbids effects such as light-by-light (LbyL) scattering, γ γ → γ γ , which is a purely quantum-mechanical process. It was realized in the early history of quantum electrodynamics (QED) that LbyL scattering is related to the polarization of the vacuum1. In the standard model of particle physics, the virtual particles that mediate the LbyL coupling are electrically charged fermions or W±bosons. In QED, the γ γ → γ γ reaction proceeds at lowest order in the fine-structure constant (αem) via virtual one-loop box diagrams involving fermions (Fig. 1a), which is an O(α4

em≈3 × 10

9) process, making it challenging to test experimentally. Indeed, the elastic LbyL scattering has remained unobserved: even the ultra-intense laser experiments are not yet powerful enough to probe this phenomenon2.

LbyL scattering via an electron loop has been precisely, albeit indirectly, tested in measurements of the anomalous magnetic moment of the electron and muon3,4 where it is predicted to contribute substantially, as one of the QED corrections5. The γ γ → γ γ reaction has been measured in photon scattering in the Coulomb field of a nucleus (Delbrück scattering) at fixed photon energies below 7 GeV (refs 6–9). The analogous process, where a photon splits into two photons by interaction with external fields (photon splitting), has been observed in the energy region of 0.1–0.5 GeV (ref. 10). A related process involving only real photons, in which several photons fuse to form an electron–positron pair (e+

e−

), has been measured in ref. 11. Similarly, the multiphoton Compton scattering, in which up to four laser photons interact with an electron, has been observed12.

An alternative way by which LbyL interactions can be studied is by using relativistic heavy-ion collisions. In ‘ultra-peripheral collision’ (UPC) events, with impact parameters larger than twice the radius of the nuclei13,14, the strong interaction does not play a role. The electromagnetic (EM) field strengths of relativistic ions scale with the proton number (Z). For example, for a lead (Pb) nucleus with Z = 82 the field can be up to 1025V m−1 (ref. 15), much larger than the Schwinger limit16above which QED corrections become important. In the 1930s it was found that highly

relativistic charged particles can be described by the equivalent photon approximation (EPA)17–19, which is schematically shown in Fig. 1b. The EM fields produced by the colliding Pb nuclei can be treated as a beam of quasi-real photons with a small virtuality of Q2< 1/R2, where R is the radius of the charge distribution and so Q2< 10−3GeV2. Then, the cross-section for the reaction Pb + Pb (γ γ ) → Pb + Pb γ γ can be calculated by convolving the respective photon flux with the elementary cross-section for the process γ γ → γ γ . Since the photon flux associated with each nucleus scales as Z2, the cross-section is extremely enhanced as compared with proton–proton (pp) collisions.

In this article, a measurement of LbyL scattering in Pb + Pb collisions at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is reported, following the approach recently proposed in ref. 20. The final-state signature of interest is the exclusive production of two photons, Pb + Pb (γ γ ) → Pb(∗)+

Pb(∗)

γ γ , where a possible EM excitation of the outgoing ions21is denoted by (∗

). Hence, the expected signature is two photons and no further activity in the central detector, since the Pb(∗)ions escape into the LHC beam pipe. Moreover, it is predicted that the background is relatively low in heavy-ion collisions and is dominated by exclusive dielectron (γ γ → e+

e−

) production20,22. The misidentification of electrons as photons can occur when the electron track is not reconstructed or the electron emits a hard-bremsstrahlung photon. The fiducial cross-section of the process γ γ → γ γ in Pb + Pb collisions is measured, using a data set recorded at a nucleon–nucleon centre-of-mass energy (√sNN) of 5.02 TeV. This data set was recorded with the ATLAS detector at the LHC in 2015 and corresponds to an integrated luminosity of 480 ± 30 µb−1. In addition to the measured fiducial cross-section, the significance of the observed number of signal candidate events is given, assuming the background-only hypothesis.

Experimental set-up

ATLAS is a cylindrical particle detector composed of several sub-detectors23. ATLAS uses a right-handed coordinate system with its origin at the nominal interaction point in the centre of the detector and the z axis along the beam pipe. The x axis points from the interaction point to the centre of the LHC ring, and the y

†A full list of authors and affiliations appears at the end of the paper.

= X X X Pb82+ Pb82+ X v ≈ c v ≈ −c EM fields EM fields Pb Pb a b

Figure 1 | Diagrams illustrating the QED LbyL interaction processes and the equivalent photon approximation. a, Diagrams for Delbrück scattering (left),

photon splitting (middle) and elastic LbyL scattering (right). Each cross denotes external field legs, for example, an atomic Coulomb field or a strong background magnetic field.b, Illustration of an ultra-peripheral collision of two lead ions. Electromagnetic interaction between the ions can be described as

an exchange of photons that can couple to form a given final state X. The flux of photons is determined from the Fourier transform of the electromagnetic field of the ion, taking into account the nuclear electromagnetic form factors.

axis points upwards. Cylindrical coordinates (r, φ) are used in the transverse plane, with φ being the azimuthal angle around the z axis. The pseudorapidity is defined in terms of the polar angle θ as η = −ln tan(θ /2).

Angular distance is measured in units of 1R ≡√(1η)2+(1φ)2. The photon or electron transverse energy is ET= Esin(θ ), where E is its energy. The inner tracking detector (ITD) consists of a silicon pixel system, a silicon microstrip detector and a straw-tube tracker immersed in a 2T magnetic field provided by a superconducting solenoid. The ITD track reconstruction efficiency is estimated in ref. 24 for minimum-bias pp events that, like UPC Pb + Pb events, have a low average track multiplicity. For charged hadrons in the transverse momentum range 100 < pT< 200 MeV the efficiency is about 50% and grows to 80% for pT> 200 MeV. Around the tracker there is a system of EM and hadronic calorimeters, which use liquid argon and lead, copper or tungsten absorbers for the EM and forward (|η| > 1.7) hadronic components of the detector, and scintillator-tile active material and steel absorbers for the central (|η| < 1.7) hadronic component. The muon spectrometer consists of separate trigger and high-precision tracking chambers measuring the trajectory of muons in a magnetic field generated by superconducting air-core toroids. The ATLAS minimum-bias trigger scintillators (MBTSs) consist of scintillator slabs positioned between the ITD and the endcap calorimeters with each side having an outer ring of four slabs segmented in azimuthal angle, covering 2.07 < |η| < 2.76 and an inner ring of eight slabs, covering 2.76 < |η| < 3.86. The ATLAS zero-degree calorimeters (ZDCs), located along the beam axis at 140 m from the interaction point on both sides, detect neutral particles (including neutrons emitted from the nucleus). The ATLAS trigger system25consists of a Level-1 trigger implemented using a combination of dedicated electronics and programmable logic, and a software-based high-level trigger.

Monte Carlo simulation and theoretical predictions

Several Monte Carlo (MC) samples are produced to estimate background contributions and corrections to the fiducial measurement. The detector response is modelled using a simulation based on GEANT4 (refs 26,27). The data and MC simulated events are passed through the same reconstruction and analysis procedures.

LbyL signal events are generated taking into account box diagrams with charged leptons and quarks in the loops, as detailed in ref. 28. The contributions from W -boson loops are omitted in the calculations since they are mostly important for diphoton masses mγ γ> 2mW(ref. 29). The calculations are then convolved with the Pb + Pb EPA spectrum from the STARlight 1.1 MC generator30. Next, various diphoton kinematic distributions are cross-checked with predictions from ref. 20 and good agreement is found. The

theoretical uncertainty on the cross-section is mainly due to limited knowledge of the nuclear electromagnetic form factors and the related initial photon fluxes. This is studied in ref. 20 and the relevant uncertainty is conservatively estimated to be 20%. Higher-order corrections (not included in the calculations) are also part of the theoretical uncertainty and are of the order of a few per cent for diphoton invariant masses below 100 GeV (refs 31,32).

The sources of background considered in this analysis are: γ γ → e+

e−

, central exclusive production (CEP) of photon pairs, exclusive production of quark–antiquark pairs (γ γ → q¯q) and other backgrounds that could mimic the diphoton event signatures. The γ γ → e+

e−

background is modelled with STARlight 1.1 (ref. 30), in which the cross-section is computed by combining the Pb + Pb EPA with the leading-order formula for γ γ → e+

e−

. This process has been recently measured by the ALICE Collaboration, and a good agreement with STARlight is found33. The exclusive diphoton final state can be also produced via the strong interaction through a quark loop in the exchange of two gluons in a colour-singlet state (see Supplementary Fig. 2). This CEP process, gg → γ γ , is modelled using SUPERCHIC2.03 (ref. 34), in which the pp cross-section has been scaled by A2R4

g as suggested in ref. 20, where A =208 and Rg≈0.7 is a gluon shadowing correction35. This process has a large theoretical uncertainty, of O (100%), mostly related to incomplete knowledge of gluon densities36. The γ γ → q¯q contribution is estimated using Herwig++ 2.7.1 (ref. 37) where the EPA formalism in pp collisions is implemented. The γ γ → q¯q sample is then normalized to the corresponding cross-section in Pb + Pb collisions30.

Event selection

Candidate diphoton events were recorded in the Pb + Pb run in 2015 using a dedicated trigger for events with moderate activity in the calorimeter but little additional activity in the entire detector. At Level-1 the total ET registered in the calorimeter after noise suppression was required to be between 5 and 200 GeV. Then at the high-level trigger, events were rejected if more than one hit was found in the inner ring of the MBTS (MBTS veto) or if more than ten hits were found in the pixel detector.

The efficiency of the Level-1 trigger is estimated with γ γ → e+ e− events passing an independent supporting trigger. This trigger is designed to select events with mutual dissociation of Pb nuclei and small activity in the ITD. It is based on a coincidence of signals in both ZDC sides and a requirement on the total ETin the calorimeter below 50 GeV. Event candidates are required to have only two reconstructed tracks and two EM energy clusters. Furthermore, to reduce possible backgrounds, each pair of clusters (cl1, cl2) is required to have a small acoplanarity (1 − 1φcl1,cl2/π < 0.2). The extracted Level-1 trigger efficiency is provided as a function of the

ARTICLES

ET (GeV)

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18

Photon PID efficiency

0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 1.2 1.4 ATLAS Data, 480 μb−1 MC Data, 480 μb−1 MC Ee T − pTtrk2 (GeV) 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18

Photon reconstruction efficiency

0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 1.2 1.4 ATLAS Pb + Pb √sNN = 5.02 TeV Pb + Pb √sNN = 5.02 TeV b a

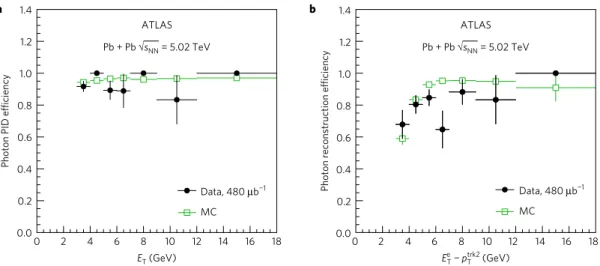

Figure 2 | Photon identification and reconstruction efficiencies. a, Photon PID efficiency as a function of photon ETextracted from FSR event candidates.

b, Photon reconstruction efficiency as a function of photon ET(approximated with EeT−ptrk2T ) extracted from γ γ →e+e−events with a

hard-bremsstrahlung photon. Data (filled markers) are compared with MC simulations (open markers). The statistical uncertainties arising from the finite size of the data and simulation samples are indicated by vertical bars.

sum of cluster transverse energies (Ecl1 T + E

cl2

T ). The efficiency grows from about 70% at (Ecl1

T +ETcl2) = 6 GeV to 100% at (ETcl1+ ETcl2) > 9 GeV. The efficiency is parameterized using an error function fit, which is then used to reweight the simulation. Due to the extremely low noise, very high hit reconstruction efficiency and low conversion probability of signal photons in the pixel detector (around 10%), the uncertainty due to the requirement for minimal activity in the ITD is negligible. The MBTS veto efficiency was studied using γ γ → `+

`−

events (` = e, µ) passing a supporting trigger and it is estimated to be (98 ± 2)%.

Photons are reconstructed from EM clusters in the calorimeter and tracking information provided by the ITD, which allows the identification of photon conversions. Selection requirements are applied to remove EM clusters with a large amount of energy from poorly functioning calorimeter cells, and a timing requirement is made to reject out-of-time candidates. An energy calibration specifically optimized for photons38is applied to the candidates to account for upstream energy loss and both lateral and longitudinal shower leakage. A dedicated correction39is applied for photons in MC samples to correct for potential mismodelling of quantities that describe the properties (‘shapes’) of the associated EM showers.

The photon particle identification (PID) in this analysis is based on three shower-shape variables: the lateral width of the shower in the middle layer of the EM calorimeter, the ratio of the energy difference associated with the largest and second largest energy deposits to the sum of these energies in the first layer, and the fraction of energy reconstructed in the first layer relative to the total energy of the cluster. Only photons with ET> 3 GeV and |η| < 2.37, excluding the calorimeter transition region 1.37 < |η| < 1.52, are considered. The pseudorapidity requirement ensures that the pho-ton candidates pass through regions of the EM calorimeter where the first layer is segmented into narrow strips, allowing for good separation between genuine prompt photons and photons coming from the decay of neutral hadrons. A constant photon PID efficiency of 95% as a function of η with respect to reconstructed photon can-didates is maintained. This is optimized using multivariate analysis techniques40, such that EM energy clusters induced by cosmic-ray muons are rejected with 95% efficiency.

Preselected events are required to have exactly two photons satisfying the above selection criteria, with a diphoton invariant mass greater than 6 GeV. To reduce the dielectron background, a veto on the presence of any charged-particle tracks (with pT> 100 MeV, |η| < 2.5 and at least one hit in the pixel detector)

is imposed. This requirement further reduces the fake-photon background from the dielectron final state by a factor of 25, according to simulation. It has almost no impact on γ γ → γ γ signal events, since the probability of photon conversion in the pixel detector is relatively small and converted photons are suppressed at low ET(3–6 GeV) by the photon selection requirements. According to MC studies, the photon selection requirements remove about 10% of low-ETphotons. To reduce other fake-photon backgrounds (for example, cosmic-ray muons), the transverse momentum of the diphoton system (pγ γT ) is required to be below 2 GeV. To reduce background from CEP gg → γ γ reactions, an additional requirement on diphoton acoplanarity, Aco = 1 − 1φγ γ/π < 0.01, is imposed. This requirement is optimized to retain a high signal efficiency and reduce the CEP background significantly, since the transverse momentum transferred by the photon exchange is usually much smaller than that due to the colour-singlet-state gluons41.

Performance and validation of photon reconstruction

Since the analysis requires the presence of low-energy photons, which are not typically used in ATLAS analyses, detailed studies of photon reconstruction and calibration are performed.

High-pT γ γ → `+ `−

production with a final-state radiation (FSR) photon is used for the measurement of the photon PID efficiency. Events with a photon and two tracks corresponding to oppositely charged particles with pT> 1 GeV are required to pass the same trigger as in the diphoton selection or the supporting trigger. The 1R between a photon candidate and a track is required to be greater than 0.2 to avoid leakage of the electron clusters from the γ γ → e+

e−

process to the photon cluster. The FSR event candidates are identified using a pttγT < 1 GeV requirement, where p

ttγ T is the transverse momentum of the three-body system consisting of two charged-particle tracks and a photon. The FSR photons are then used to extract the photon PID efficiency, which is defined as the probability for a reconstructed photon to satisfy the identification criteria. Figure 2a shows the photon PID efficiencies in data and simulation as a function of reconstructed photon ET. Within their statistical precision the two results agree.

The photon reconstruction efficiency is extracted from data using γ γ → e+

e−

events where one of the electrons emits a hard-bremsstrahlung photon due to interaction with the material of the detector. Events with exactly one identified electron, two reconstructed charged-particle tracks and exactly one photon are studied. The electron ETis required to be above 5 GeV and the pT

γγ acoplanarity 0.00 0.01 0.02 0.03 0.04 0.05 0.06 Events/0.005 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 Signal selection no Aco requirement Data, 480 μb−1 γγ → γγ MC γγ → e+e− MC CEP γγ MC mγγ (GeV) 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 Events/3 GeV 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 Signal selection with Aco < 0.01 ATLAS Pb + Pb √sNN = 5.02 TeV Data, 480 μb−1 γγ → γγ MC γγ → e+e− MC CEP γγ MC ATLAS Pb + Pb √sNN = 5.02 TeV b a

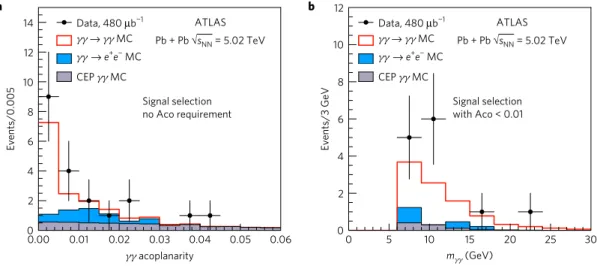

Figure 3 | Kinematic distributions for γ γ →γ γ event candidates. a, Diphoton acoplanarity before applying the Aco < 0.01 requirement. b, Diphoton

invariant mass after applying the Aco < 0.01 requirement. Data (points) are compared to MC predictions (histograms). The statistical uncertainties on the data are shown as vertical bars.

of the track that is unmatched with the electron (trk2) is required to be below 2 GeV. The additional hard-bremsstrahlung photon is expected to have ETγ≈(ETe− p

trk2 T ). The p

trk2

T < 2 GeV requirement ensures a sufficient 1R separation between the expected photon and the second electron, extrapolated to the first layer of the EM calorimeter. The data sample contains 247 γ γ → e+

e−

events that are used to extract the photon reconstruction efficiency, which is presented in Fig. 2b. Good agreement between data and γ γ → e+

e− MC simulation is observed and the photon reconstruction efficiency is measured with a 5–10% relative uncertainty at low ET(3–6 GeV).

In addition, a cross-check is performed on Z → µ+ µ−

γ events identified in pp collision data from 2015 corresponding to an inte-grated luminosity of 1.6 fb−1. The results support (in a similar way to ref. 42) the choice to use the three shower-shape variables in this photon PID selection in an independent sample of low-ETphotons. The photon cluster energy resolution is extracted from data using γ γ → e+

e−

events. The electrons from the γ γ → e+ e− reaction (see Supplementary Information) are well balanced in their transverse momenta, with very small standard deviation, σpe+T−p

e− T < 30 MeV, much smaller than the expected EM calorimeter energy resolution. Therefore, by measuring (Ecl1

T − E cl2

T ) distributions in γ γ → e+

e−

events, one can extract the cluster energy resolution, σEcl

T. For electrons with ET< 10 GeV, the σE cl T/E

cl

T is observed to be approximately 8% both in data and simulation. An uncertainty of δσEγ

T/σE γ

T =15% is assigned to the simulated photon energy resolution and takes into account differences between σETclin data and σEγ

T in simulation.

Similarly, the EM cluster energy scale can be studied using the (Ecl1

T + E cl2

T ) distribution. It is observed that the simulation provides a good description of this distribution, within the relative uncertainty of 5% that is assigned to the EM cluster energy-scale modelling.

Background estimation

Due to its relatively high rate, the exclusive production of electron pairs (γ γ → e+

e−

) can be a source of fake diphoton events. The contribution from the dielectron background is estimated using γ γ → e+

e−

MC simulation (which gives 1.3 events) and is verified using the following data-driven technique. Two control regions are defined that are expected to be dominated by γ γ → e+

e− backgrounds. The first control region is defined by requiring events with exactly one reconstructed charged-particle track and two identified photons that satisfy the same preselection criteria as for the signal definition. The second control region is defined similarly

to the first one, except exactly two tracks are required (Ntrk=2). Good agreement is observed between data and MC simulation in both control regions, but the precision is limited by the number of events in data. A conservative uncertainty of 25% is therefore assigned to the γ γ → e+

e−

background estimation, which reflects the statistical uncertainty of data in the Ntrk=1 control region. The contribution from a related QED process, γ γ → e+

e− γ γ , is evaluated using the MadGraph5_aMC@NLO MC generator43and is found to be negligible.

The Aco < 0.01 requirement significantly reduces the CEP gg → γ γbackground. However, the MC prediction for this process has a large theoretical uncertainty; hence, an additional data-driven normalization is performed in the region Aco > b, where b is a value greater than 0.01 which can be varied. Three values of b (0.01, 0.02, 0.03) are used, where the central value b = 0.02 is chosen to derive the nominal background prediction and the values b = 0.01 and b =0.03 to define the systematic uncertainty. The normalization is performed using the condition: fnorm,b

gg →γ γ=(Ndata (Aco > b) −Nsig (Aco > b) −Nγ γ →e+

e−(Aco > b))/Ngg →γ γ(Aco > b), for each value of b, where Ndatais the number of observed events, Nsigis the expected number of signal events, Nγ γ →e+

e−is the expected background from γ γ → e+

e−

events and Ngg →γ γ is the MC estimate of the expected background from CEP gg → γ γ events. The normalization factor is found to be fnorm

gg →γ γ=0.5 ± 0.3 and the background due to CEP gg → γ γ is estimated to be fnorm

gg →γ γ× Ngg →γ γ (Aco < 0.01) = 0.9 ± 0.5 events. To verify the CEP gg → γ γ background estimation method, energy deposits in the ZDC are studied for events before the Aco selection. It is expected that the outgoing ions in CEP events predominantly dissociate, which results in the emission of neutrons detectable in the ZDC20. Good agreement between the normalized CEP gg → γ γ MC expectation and the observed events with a ZDC signal corresponding to at least 1 neutron is observed in the full Aco range (see Supplementary Information for details).

Low-pT dijet events can produce multiple π0 mesons, which could potentially mimic diphoton events. The event selection requirements are efficient in rejecting such events, and based on studies performed with a supporting trigger, the background from hadronic processes is estimated to be 0.3 ± 0.3 events. MC studies show that the background from γ γ → q¯q processes is negligible.

Exclusive neutral two-meson production can be a potential source of background for LbyL events, mainly due to their back-to-back topology being similar to that of the CEP gg → γ γ process. The cross-section for this process is calculated to be below 10% of the CEP gg → γ γ cross-section44,45and it is therefore considered to

ARTICLES

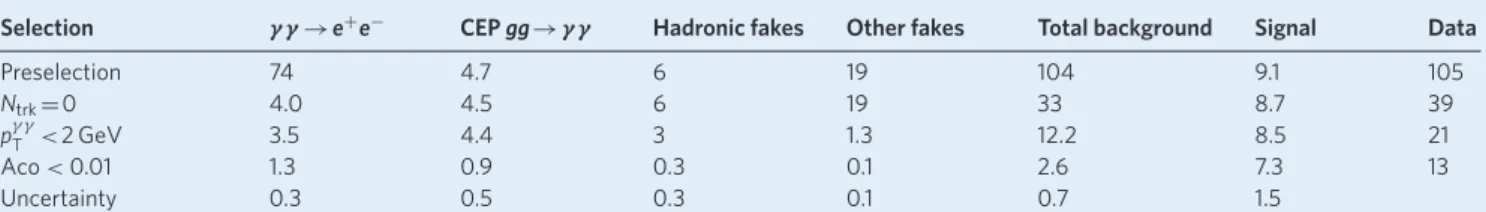

Table 1 | The number of events accepted by the sequential selection requirements for data, compared with the number of background and signal events expected from the simulation.

Selection γ γ →e+e− CEP gg→γ γ Hadronic fakes Other fakes Total background Signal Data

Preselection 74 4.7 6 19 104 9.1 105 Ntrk=0 4.0 4.5 6 19 33 8.7 39 pγ γ T <2 GeV 3.5 4.4 3 1.3 12.2 8.5 21 Aco < 0.01 1.3 0.9 0.3 0.1 2.6 7.3 13 Uncertainty 0.3 0.5 0.3 0.1 0.7 1.5

The signal simulation is based on calculations from ref. 28. In addition, the uncertainties on the expected number of events passing all selection requirements are given.

give a negligible contribution to the signal region. The contribution from bottomonia production (for example, γ γ → ηb→γ γ or γ Pb → Υ → γ ηb→3γ ) is calculated using parameters from refs 46, 47 and is found to be negligible.

The contribution from other fake diphoton events (for example those induced by cosmic-ray muons) is estimated using photons that fail to satisfy the longitudinal shower-shape requirement. The total background due to other fake photons is found to be 0.1 ± 0.1 events. As a further cross-check, additional activity in the muon spectrometer is studied. It is observed that out of 18 events satisfying the inverted pγ γT requirement, 13 have at least one additional reconstructed muon. In the region pγ γT < 2 GeV, no events with muon activity are found, which is compatible with the above-mentioned estimate of 0.1 ± 0.1.

The contribution from UPC events where both nuclei emit a bremsstrahlung photon is estimated using calculations from ref. 13 and is found to be negligible for photons with |η| < 2.4 and ET> 3 GeV.

Results

Photon kinematic distributions for events satisfying the selection criteria are shown in Fig. 3. The shape of the diphoton acoplanarity distribution for γ γ → e+

e−

events in Fig. 3a reflects the trajectories of the electron and positron in the detector magnetic field, before they emit hard photons in their collisions with the ITD material. In total, 13 events are observed in data whereas 7.3 signal events and 2.6 background events are expected. In general, good agreement bet-ween data and MC simulation is observed. The effect of sequential selection requirements on the number of events selected is shown in Table 1, for each of the data, signal and background samples.

To quantify an excess of events over the background expectation, a test statistic based on the profile likelihood ratio48is used. The p value for the background-only hypothesis, defined as the probability for the background to fluctuate and give an excess of events as large or larger than that observed in the data, is found to be 5 × 10−6. The p value can be expressed in terms of Gaussian tail probabilities, which, given in units of standard deviation (σ ), corresponds to a significance of 4.4σ . The expected p value and significance (obtained before the fit of the signal-plus-background hypothesis to the data and using standard model predictions from ref. 28) are 8 × 10−5and 3.8σ , respectively.

The cross-section for the Pb + Pb (γ γ ) → Pb(∗)+ Pb(∗)γ γ process is measured in a fiducial phase space defined by the pho-ton transverse energy ET> 3 GeV, photon absolute pseudorapidity |η| < 2.4, diphoton invariant mass greater than 6 GeV, diphoton transverse momentum lower than 2 GeV and diphoton acoplanarity below 0.01. Experimentally, the fiducial cross-section is given by

σfid=

Ndata− Nbkg

C ×R Ldt (1)

where Ndata is the number of selected events in data, Nbkg is the expected number of background events andR Ldt is the integrated

Table 2 | Summary of systematic uncertainties.

Source of uncertainty Relative uncertainty

Trigger 5%

Photon reco. efficiency 12%

Photon PID efficiency 16%

Photon energy scale 7%

Photon energy resolution 11%

Total 24%

The table shows the relative systematic uncertainty on detector correction factor C broken into its individual contributions. The total is obtained by adding them in quadrature.

luminosity. The factor C is used to correct for the net effect of the trigger efficiency, the diphoton reconstruction and PID efficiencies, as well as the impact of photon energy and angular resolution. It is defined as the ratio of the number of generated signal events satisfying the selection criteria after particle reconstruction and detector simulation to the number of generated events satisfying the fiducial criteria before reconstruction. The value of C and its total uncertainty is determined to be 0.31 ± 0.07. The dominant systematic uncertainties come from the uncertainties on the photon reconstruction and identification efficiencies. Other minor sources of uncertainty are the photon energy scale and resolution uncertain-ties and trigger efficiency uncertainty. To check for a potential model dependence, calculations from ref. 28 are compared with predictions from ref. 20, and a negligible impact on the C-factor uncertainty is found. Table 2 lists the separate contributions to the systematic uncertainty. The uncertainty on the integrated luminosity is 6%. It is derived following a methodology similar to that detailed in refs 49,50, from a calibration of the luminosity scale using x–y beam-separation scans performed in December 2015.

The measured fiducial cross-section is σfid=70 ± 24 (stat.) ±17 (syst.) nb, which is in agreement with the predicted values of 45 ± 9 nb (ref. 20) and 49 ± 10 nb (ref. 28) within uncertainties.

Conclusion

In summary, this article presents evidence for the scattering of LbyL in quasi-real photon interactions from 480 µb−1of ultra-peripheral Pb + Pb collisions at√sNN=5.02 TeV by the ATLAS experiment at the LHC. The statistical significance against the background-only hypothesis is found to be 4.4 standard deviations. After background subtraction and analysis corrections, the fiducial cross-section for the Pb + Pb (γ γ ) → Pb(∗)+Pb(∗)γ γ process was measured and is compatible with standard model predictions.

The analysis is mostly limited by the amount of data available and the lower limit on transverse energy for reconstructed photons (ET=3 GeV), below which more signal is expected. Advancements on these two points would also allow for reconstruction of low-mass mesons decaying into two photons, which in turn could be used to improve detector calibration. The heavy-ion data yield is expected to double at the end of 2018 (and again increase tenfold after

LHC Run 4, scheduled to start in 2026), which would significantly reduce the statistical uncertainty. Future upgrades of ATLAS, such as extended tracking acceptance from |η| < 2.5 to |η| < 4.0, will further improve this.

Data availability. The experimental data that support the findings of this study are available in HEPData with the identifier http://dx.doi.org/10.17182/hepdata.77761.

Received 9 February 2017; accepted 15 June 2017; published online 14 August 2017

References

1. Heisenberg, W. & Euler, H. Folgerungen aus der Diracschen Theorie des Positrons. Z. Phys. 98, 714–732 (1936).

2. King, B. & Heinzl, T. Measuring vacuum polarisation with high power lasers. High Power Laser Sci. Eng. 4,e5 (2016).

3. Hanneke, D., Fogwell, S. & Gabrielse, G. New measurement of the electron magnetic moment and the fine structure constant. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 120801 (2008).

4. Bennett, G.W. et al. (Muon g –2 Collaboration) Final report of the muon E821 anomalous magnetic moment measurement at BNL. Phys. Rev. D 73, 072003 (2006).

5. Laporta, S. & Remiddi, E. The analytical value of the electron light-light graphs contribution to the muon (g − 2) in QED. Phys. Lett. B 301, 440–446 (1993). 6. Wilson, R. R. Scattering of 1.33 MeV gamma-rays by an electric field. Phys. Rev.

90, 720–721 (1953).

7. Jarlskog, G. et al. Measurement of Delbrück scattering and observation of photon splitting at high energies. Phys. Rev. D 8, 3813–3823 (1973). 8. Schumacher, M. et al. Delbrück scattering of 2.75-MeV photons by lead.

Phys. Lett. B 59,134–136 (1975).

9. Akhmadaliev, S. Z. et al. Delbrück scattering at energies of 140–450 MeV. Phys. Rev. C 58,2844–2850 (1998).

10. Akhmadaliev, S. Z. et al. Experimental investigation of high-energy photon splitting in atomic fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 061802 (2002).

11. Burke, D. L. et al. Positron production in multi-photon light by light scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79,1626–1629 (1997).

12. Bula, C. et al. Observation of nonlinear effects in Compton scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76,3116–3119 (1996).

13. Bertulani, C. A. & Baur, G. Electromagnetic processes in relativistic heavy ion collisions. Phys. Rep. 163, 299–408 (1988).

14. Natale, A. A., Roldao, C. G. & Carneiro, J. P. V. Two photon final states in peripheral heavy ion collisions. Phys. Rev. C 65, 014902 (2002).

15. Şengül, M. Y. et al. Electromagnetic heavy-lepton pair production in relativistic heavy-ion collisions. Eur. Phys. J. C 76, 428 (2016).

16. Schwinger, J. S. On gauge invariance and vacuum polarization. Phys. Rev. 82, 664–679 (1951).

17. Fermi, E. On the theory of collisions between atoms and electrically charged particles. Nuovo Cimento 2, 143–158 (1925).

18. Weizsäcker, C. F. Radiation emitted in collisions of very fast electrons. Z. Phys.

88, 612–625 (1934).

19. Williams, E. J. Nature of the high energy particles of penetrating radiation and status of ionization and radiation formulae. Phys. Rev. 45, 729–730 (1934). 20. d’Enterria, D. & Silveira, G. G. Observing light-by-light scattering at the large

hadron collider. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 080405 (2013); erratum 116, 129901 (2016).

21. Abelev, B. et al. (ALICE Collaboration) Measurement of the cross section for electromagnetic dissociation with neutron emission in Pb-Pb collisions at √

sNN=2.76 TeV. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 252302 (2012).

22. Knapen, S. et al. Searching for axionlike particles with ultraperipheral heavy-ion collisions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 171801 (2017).

23. ATLAS Collaboration. The ATLAS experiment at the CERN large hadron collider. JINST 3, S08003 (2008).

24. ATLAS Collaboration. Charged-particle distributions at low transverse momentum in√s =13 TeV pp interactions measured with the ATLAS detector at the LHC. Eur. Phys. J. C 76, 502 (2016).

25. ATLAS Collaboration. Performance of the ATLAS trigger system in 2010. Eur. Phys. J. C 72,1849 (2012).

26. Agostinelli, S. et al. GEANT4: a Simulation toolkit. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 506, 250–303 (2003).

27. ATLAS Collaboration. The ATLAS simulation infrastructure. Eur. Phys. J. C

70, 823–874 (2010).

28. Kłusek-Gawenda, M., Lebiedowicz, P. & Szczurek, A. Light-by-light scattering in ultraperipheral Pb-Pb collisions at energies available at the CERN Large Hadron Collider. Phys. Rev. C 93, 044907 (2016).

29. Fichet, S. et al. Light-by-light scattering with intact protons at the LHC: from standard model to new physics. J. High Energy Phys. 2, 165 (2015). 30. Klein, S. R. et al. STARlight: a Monte Carlo simulation program for

ultra-peripheral collisions of relativistic ions. Comput. Phys. Commun. 212, 258–268 (2017).

31. Bern, Z. et al. QCD and QED corrections to light by light scattering. J. High Energy Phys. 11,031 (2001).

32. Kłusek-Gawenda, M., Schäfer, W. & Szczurek, A. Two-gluon exchange contribution to elastic γ γ → γ γ scattering and production of two-photons in ultraperipheral ultrarelativistic heavy ion and proton-proton collisions. Phys. Lett. B 761,399–407 (2016).

33. Abbas, E. et al. (ALICE Collaboration) Charmonium and e+

e−

pair photoproduction at mid-rapidity in ultra-peripheral Pb-Pb collisions at √

sNN=2.76 TeV. Eur. Phys. J. C 73, 2617 (2013).

34. Harland-Lang, L. A., Khoze, V. A. & Ryskin, M. G. Exclusive physics at the LHC with SuperChic 2. Eur. Phys. J. C 76, 9 (2016).

35. Eskola, K. J., Paukkunen, H. & Salgado, C. A. EPS09: a new generation of NLO and LO nuclear parton distribution functions. J. High Energy Phys. 4, 065 (2009).

36. Aaltonen, T. et al. (CDF Collaboration) Observation of exclusive gamma gamma production in p¯p collisions at√s =1.96 TeV. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 081801 (2012).

37. Bähr, M. et al. Herwig++ physics and manual. Eur. Phys. J. C 58, 639–707 (2008).

38. ATLAS Collaboration. Electron and photon energy calibration with the ATLAS detector using LHC Run 1 data. Eur. Phys. J. C 74, 3071 (2014).

39. ATLAS Collaboration. Measurement of the photon identification

efficiencies with the ATLAS detector using LHC Run-1 data. Eur. Phys. J. C 76, 666 (2016).

40. Höcker, A. et al. TMVA - toolkit for multivariate data analysis. PoS ACAT Preprint athttp://arXiv.org/abs/physics/0703039(2007).

41. Baur, G. et al. Coherent gamma gamma and gamma-A interactions in very peripheral collisions at relativistic ion colliders. Phys. Rep. 364, 359–450 (2002).

42. ATLAS Collaboration. Reconstruction of Collinear Final-State-Radiation Photons in Z Decays to Muons in√s =7 TeV Proton-Proton Collisions (ATLAS-CONF-2012-143, 2012);https://cds.cern.ch/record/1491697

43. Alwall, J. et al. The automated computation of tree-level and next-to-leading order differential cross sections, and their matching to parton shower simulations. J. High Energy Phys. 7, 79 (2014).

44. Harland-Lang, L. A. et al. Central exclusive meson pair production in the perturbative regime at hadron colliders. Eur. Phys. J. C 71, 1714 (2011).

45. Harland-Lang, L. A. et al. Central exclusive production as a probe of the gluonic component of the eta’ and eta mesons. Eur. Phys. J. C 73, 2429 (2013).

46. Ebert, D., Faustov, R. N. & Galkin, V. O. Properties of heavy quarkonia and Bcmesons in the relativistic quark model. Phys. Rev. D 67,

014027 (2003).

47. Segovia, J. et al. Bottomonium spectrum revisited. Phys. Rev. D 93, 074027 (2016).

48. Cowan, G. et al. Asymptotic formulae for likelihood-based tests of new physics. Eur. Phys. J. C 71,1554 (2011); erratum 73, 2501 (2013).

49. ATLAS Collaboration. Improved luminosity determination in pp collisions at√ s =7 TeV using the ATLAS detector at the LHC. Eur. Phys. J. C 73, 2518 (2013).

50. ATLAS Collaboration. Luminosity determination in pp collisions at√s =8 TeV using the ATLAS detector at the LHC. Eur. Phys. J. C 76, 653 (2016). 51. ATLAS Collaboration. ATLAS Computing Acknowledgements 2016–2017,

ATL-GEN-PUB-2016-002 (2016);https://cds.cern.ch/record/2199109 Acknowledgements

We thank CERN for the very successful operation of the LHC, as well as the support staff from our institutions without whom ATLAS could not be operated efficiently. We acknowledge the support of ANPCyT, Argentina; YerPhI, Armenia; ARC, Australia; BMWFW and FWF, Austria; ANAS, Azerbaijan; SSTC, Belarus; CNPq and FAPESP, Brazil; NSERC, NRC and CFI, Canada; CERN; CONICYT, Chile; CAS, MOST and NSFC, China; COLCIENCIAS, Colombia; MSMT CR, MPO CR and VSC CR, Czech Republic; DNRF and DNSRC, Denmark; IN2P3-CNRS, CEA-DSM/IRFU, France; GNSF, Georgia; BMBF, HGF and MPG, Germany; GSRT, Greece; RGC, Hong Kong SAR, China; ISF, I-CORE and Benoziyo Center, Israel; INFN, Italy; MEXT and JSPS, Japan; CNRST, Morocco; FOM and NWO, Netherlands; RCN, Norway; MNiSW and NCN, Poland; FCT, Portugal; MNE/IFA, Romania; MES of Russia and NRC KI, Russian Federation; JINR; MESTD, Serbia; MSSR, Slovakia; ARRS and MIZŠ, Slovenia; DST/NRF, South Africa; MINECO, Spain; SRC and Wallenberg Foundation, Sweden; SERI, SNSF and Cantons of Bern and Geneva, Switzerland; MOST, Taiwan; TAEK, Turkey; STFC, United Kingdom; DOE and NSF, United States of America. In addition, individual groups and members have received support from BCKDF, the Canada Council, CANARIE, CRC, Compute

ARTICLES

Canada, FQRNT, and the Ontario Innovation Trust, Canada; EPLANET, ERC, ERDF, FP7, Horizon 2020 and Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions, European Union; Investissements d’Avenir Labex and Idex, ANR, Région Auvergne and Fondation Partager le Savoir, France; DFG and AvH Foundation, Germany; Herakleitos, Thales and Aristeia programmes co-financed by EU-ESF and the Greek NSRF; BSF, GIF and Minerva, Israel; BRF, Norway; CERCA Programme Generalitat de Catalunya, Generalitat Valenciana, Spain; the Royal Society and Leverhulme Trust, United Kingdom. The crucial computing support from all WLCG partners is acknowledged gratefully, in particular from CERN, the ATLAS Tier-1 facilities at TRIUMF (Canada), NDGF (Denmark, Norway, Sweden), CC-IN2P3 (France), KIT/GridKA (Germany), INFN-CNAF (Italy), NL-T1 (Netherlands), PIC (Spain), ASGC (Taiwan), RAL (UK) and BNL (USA), the Tier-2 facilities worldwide and large non-WLCG resource providers. Major contributors of computing resources are listed in ref. 51.

Author contributions

All authors have contributed to the publication, being variously involved in the design and the construction of the detectors, in writing software, calibrating subsystems, operating the detectors and acquiring data, and finally analysing the processed data. The ATLAS Collaboration members discussed and approved the scientific results. The manuscript was prepared by a subgroup of authors appointed by the collaboration and subject to an internal collaboration-wide review process. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Additional information

Supplementary information is available in theonline version of the paper. Reprints and

permissions information is available online atwww.nature.com/reprints. Publisher’s note:

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to ATLAS Collaboration.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

ATLAS Collaboration

M. Aaboud181, G. Aad116, B. Abbott145, J. Abdallah10, O. Abdinov14‡, B. Abeloos149, S. H. Abidi210, O. S. AbouZeid184,

N. L. Abraham200, H. Abramowicz204, H. Abreu203, R. Abreu148, Y. Abulaiti196,197, B. S. Acharya218,219,236, S. Adachi206,

L. Adamczyk61, J. Adelman140, M. Adersberger131, T. Adye171, A. A. Affolder184, T. Agatonovic-Jovin16, C. Agheorghiesei39,

J. A. Aguilar-Saavedra160,165, S. P. Ahlen30, F. Ahmadov95,b, G. Aielli174,175, S. Akatsuka98, H. Akerstedt196,197, T. P. A. Åkesson112,

A. V. Akimov127, G. L. Alberghi27,28, J. Albert225, M. J. Alconada Verzini101, M. Aleksa46, I. N. Aleksandrov95, C. Alexa38,

G. Alexander204, T. Alexopoulos12, M. Alhroob145, B. Ali168, M. Aliev103,104, G. Alimonti122, J. Alison47, S. P. Alkire57,

B. M. M. Allbrooke200, B. W. Allen148, P. P. Allport21, A. Aloisio135,136, A. Alonso58, F. Alonso101, C. Alpigiani185, A. A. Alshehri79,

M. Alstaty116, B. Alvarez Gonzalez46, D. Álvarez Piqueras223, M. G. Alviggi135,136, B. T. Amadio18, Y. Amaral Coutinho32,

C. Amelung31, D. Amidei120, S. P. Amor Dos Santos160,162, A. Amorim160,161, S. Amoroso46, G. Amundsen31, C. Anastopoulos186,

L. S. Ancu73, N. Andari21, T. Andeen13, C. F. Anders84, J. K. Anders105, K. J. Anderson47, A. Andreazza122,123, V. Andrei83,

S. Angelidakis11, I. Angelozzi139, A. Angerami57, F. Anghinolfi46, A. V. Anisenkov141,c, N. Anjos15, A. Annovi157,158, C. Antel83,

M. Antonelli71, A. Antonov129‡, D. J. Antrim217, F. Anulli172, M. Aoki96, L. Aperio Bella46, G. Arabidze121, Y. Arai96, J. P. Araque160,

V. Araujo Ferraz32, A. T. H. Arce69, R. E. Ardell108, F. A. Arduh101, J.-F. Arguin126, S. Argyropoulos93, M. Arik22,

A. J. Armbruster190, L. J. Armitage107, O. Arnaez46, H. Arnold72, M. Arratia44, O. Arslan29, A. Artamonov128, G. Artoni152,

S. Artz114, S. Asai206, N. Asbah66, A. Ashkenazi204, L. Asquith200, K. Assamagan36, R. Astalos191, M. Atkinson222, N. B. Atlay188,

K. Augsten168, G. Avolio46, B. Axen18, M. K. Ayoub149, G. Azuelos126,d, A. E. Baas83, M. J. Baca21, H. Bachacou183,

K. Bachas103,104, M. Backes152, M. Backhaus46, P. Bagiacchi172,173, P. Bagnaia172,173, J. T. Baines171, M. Bajic58, O. K. Baker232,

E. M. Baldin141,c, P. Balek228, T. Balestri199, F. Balli183, W. K. Balunas155, E. Banas63, Sw. Banerjee229,e, A. A. E. Bannoura231,

L. Barak46, E. L. Barberio119, D. Barberis74,75, M. Barbero116, T. Barillari132, M.-S. Barisits46, T. Barklow190, N. Barlow44,

S. L. Barnes55, B. M. Barnett171, R. M. Barnett18, Z. Barnovska-Blenessy53, A. Baroncelli176, G. Barone31, A. J. Barr152,

L. Barranco Navarro223, F. Barreiro113, J. Barreiro Guimarães da Costa50, R. Bartoldus190, A. E. Barton102, P. Bartos191,

A. Basalaev156, A. Bassalat149,f, R. L. Bates79, S. J. Batista210, J. R. Batley44, M. Battaglia184, M. Bauce172,173, F. Bauer183,

H. S. Bawa190,g, J. B. Beacham143, M. D. Beattie102, T. Beau111, P. H. Beauchemin216, P. Bechtle29, H. P. Beck20,h, K. Becker152,

M. Becker114, M. Beckingham226, C. Becot142, A. J. Beddall25, A. Beddall23, V. A. Bednyakov95, M. Bedognetti139, C. P. Bee199,

T. A. Beermann46, M. Begalli32, M. Begel36, J. K. Behr66, A. S. Bell109, G. Bella204, L. Bellagamba27, A. Bellerive45, M. Bellomo117,

K. Belotskiy129, O. Beltramello46, N. L. Belyaev129, O. Benary204‡, D. Benchekroun178, M. Bender131, K. Bendtz196,197, N. Benekos12,

Y. Benhammou204, E. Benhar Noccioli232, J. Benitez93, D. P. Benjamin69, M. Benoit73, J. R. Bensinger31, S. Bentvelsen139,

L. Beresford152, M. Beretta71, D. Berge139, E. Bergeaas Kuutmann221, N. Berger7, J. Beringer18, S. Berlendis81, N. R. Bernard117,

G. Bernardi111, C. Bernius142, F. U. Bernlochner29, T. Berry108, P. Berta169, C. Bertella114, G. Bertoli196,197, F. Bertolucci157,158,

I. A. Bertram102, C. Bertsche66, D. Bertsche145, G. J. Besjes58, O. Bessidskaia Bylund196,197, M. Bessner66, N. Besson183,

C. Betancourt72, A. Bethani115, S. Bethke132, A. J. Bevan107, R. M. Bianchi159, M. Bianco46, O. Biebel131, D. Biedermann19,

R. Bielski115, N. V. Biesuz157,158, M. Biglietti176, J. Bilbao De Mendizabal73, T. R. V. Billoud126, H. Bilokon71, M. Bindi80, A. Bingul23,

C. Bini172,173, S. Biondi27,28, T. Bisanz80, C. Bittrich68, D. M. Bjergaard69, C. W. Black201, J. E. Black190, K. M. Black30,

D. Blackburn185, R. E. Blair8, T. Blazek191, I. Bloch66, C. Blocker31, A. Blue79, W. Blum114‡, U. Blumenschein107, S. Blunier48,

G. J. Bobbink139, V. S. Bobrovnikov141,c, S. S. Bocchetta112, A. Bocci69, C. Bock131, M. Boehler72, D. Boerner231, D. Bogavac131,

A. G. Bogdanchikov141, C. Bohm196, V. Boisvert108, P. Bokan221,i, T. Bold61, A. S. Boldyrev130, M. Bomben111, M. Bona107,

M. Boonekamp183, A. Borisov170, G. Borissov102, J. Bortfeldt46, D. Bortoletto152, V. Bortolotto87,88,89, K. Bos139, D. Boscherini27,

M. Bosman15, J. D. Bossio Sola43, J. Boudreau159, J. Bouffard2, E. V. Bouhova-Thacker102, D. Boumediene56, C. Bourdarios149,

S. K. Boutle79, A. Boveia143, J. Boyd46, I. R. Boyko95, J. Bracinik21, A. Brandt10, G. Brandt80, O. Brandt83, U. Bratzler207, B. Brau117,

J. E. Brau148, W. D. Breaden Madden79, K. Brendlinger66, A. J. Brennan119, L. Brenner139, R. Brenner221, S. Bressler228,

D. L. Briglin21, T. M. Bristow70, D. Britton79, D. Britzger66, F. M. Brochu44, I. Brock29, R. Brock121, G. Brooijmans57, T. Brooks108,

W. K. Brooks49, J. Brosamer18, E. Brost140, J. H. Broughton21, P. A. Bruckman de Renstrom63, D. Bruncko192, A. Bruni27,

G. Bruni27, L. S. Bruni139, B. H. Brunt44, M. Bruschi27, N. Bruscino29, P. Bryant47, L. Bryngemark112, T. Buanes17, Q. Buat189,

P. Buchholz188, A. G. Buckley79, I. A. Budagov95, F. Buehrer72, M. K. Bugge151, O. Bulekov129, D. Bullock10, H. Burckhart46,

S. Burdin105, C. D. Burgard72, A. M. Burger7, B. Burghgrave140, K. Burka63, S. Burke171, I. Burmeister67, J. T. P. Burr152, E. Busato56,

D. Büscher72, V. Büscher114, P. Bussey79, J. M. Butler30, C. M. Buttar79, J. M. Butterworth109, P. Butti46, W. Buttinger36,

A. Buzatu52, A. R. Buzykaev141,c, S. Cabrera Urbán223, D. Caforio168, V. M. Cairo59,60, O. Cakir4, N. Calace73, P. Calafiura18,

A. Calandri116, G. Calderini111, P. Calfayan91, G. Callea59,60, L. P. Caloba32, S. Calvente Lopez113, D. Calvet56, S. Calvet56,

T. P. Calvet116, R. Camacho Toro47, S. Camarda46, P. Camarri174,175, D. Cameron151, R. Caminal Armadans222, C. Camincher81,

S. Campana46, M. Campanelli109, A. Camplani122,123, A. Campoverde188, V. Canale135,136, M. Cano Bret55, J. Cantero146,

T. Cao204, M. D. M. Capeans Garrido46, I. Caprini38, M. Caprini38, M. Capua59,60, R. M. Carbone57, R. Cardarelli174, F. Cardillo72,

I. Carli169, T. Carli46, G. Carlino135, B. T. Carlson159, L. Carminati122,123, R. M. D. Carney196,197, S. Caron138, E. Carquin49,

G. D. Carrillo-Montoya46, J. Carvalho160,162, D. Casadei21, M. P. Casado15,j, M. Casolino15, D. W. Casper217, R. Castelijn139,

A. Castelli139, V. Castillo Gimenez223, N. F. Castro160,k, A. Catinaccio46, J. R. Catmore151, A. Cattai46, J. Caudron29,

V. Cavaliere222, E. Cavallaro15, D. Cavalli122, M. Cavalli-Sforza15, V. Cavasinni157,158, E. Celebi22, F. Ceradini176,177,

L. Cerda Alberich223, A. S. Cerqueira33, A. Cerri200, L. Cerrito174,175, F. Cerutti18, A. Cervelli20, S. A. Cetin24, A. Chafaq178,

ARTICLES

D. Chakraborty140, S. K. Chan82, W. S. Chan139, Y. L. Chan87, P. Chang222, J. D. Chapman44, D. G. Charlton21, A. Chatterjee73,

C. C. Chau210, C. A. Chavez Barajas200, S. Che143, S. Cheatham218,220, A. Chegwidden121, S. Chekanov8, S. V. Chekulaev213,

G. A. Chelkov95,l, M. A. Chelstowska46, C. Chen94, H. Chen36, S. Chen51, S. Chen206, X. Chen52,m, Y. Chen97, H. C. Cheng120,

H. J. Cheng50, Y. Cheng47, A. Cheplakov95, E. Cheremushkina170, R. Cherkaoui El Moursli182, V. Chernyatin36‡, E. Cheu9,

L. Chevalier183, V. Chiarella71, G. Chiarelli157,158, G. Chiodini103, A. S. Chisholm46, A. Chitan38, Y. H. Chiu225, M. V. Chizhov95,

K. Choi91, A. R. Chomont56, S. Chouridou11, B. K. B. Chow131, V. Christodoulou109, D. Chromek-Burckhart46, M. C. Chu87,

J. Chudoba167, A. J. Chuinard118, J. J. Chwastowski63, L. Chytka147, A. K. Ciftci4, D. Cinca67, V. Cindro106, I. A. Cioara29,

C. Ciocca27,28, A. Ciocio18, F. Cirotto135,136, Z. H. Citron228, M. Citterio122, M. Ciubancan38, A. Clark73, B. L. Clark82, M. R. Clark57,

P. J. Clark70, R. N. Clarke18, C. Clement196,197, Y. Coadou116, M. Cobal218,220, A. Coccaro73, J. Cochran94, L. Colasurdo138,

B. Cole57, A. P. Colijn139, J. Collot81, T. Colombo217, P. Conde Muiño160,161, E. Coniavitis72, S. H. Connell194, I. A. Connelly115,

V. Consorti72, S. Constantinescu38, G. Conti46, F. Conventi135,n, M. Cooke18, B. D. Cooper109, A. M. Cooper-Sarkar152,

F. Cormier224, K. J. R. Cormier210, T. Cornelissen231, M. Corradi172,173, F. Corriveau118,o, A. Cortes-Gonzalez46, G. Cortiana132,

G. Costa122, M. J. Costa223, D. Costanzo186, G. Cottin44, G. Cowan108, B. E. Cox115, K. Cranmer142, S. J. Crawley79,

R. A. Creager155, G. Cree45, S. Crépé-Renaudin81, F. Crescioli111, W. A. Cribbs196,197, M. Crispin Ortuzar152, M. Cristinziani29,

V. Croft138, G. Crosetti59,60, A. Cueto113, T. Cuhadar Donszelmann186, J. Cummings232, M. Curatolo71, J. Cúth114, H. Czirr188,

P. Czodrowski46, G. D’amen27,28, S. D’Auria79, M. D’Onofrio105, M. J. Da Cunha Sargedas De Sousa160,161, C. Da Via115,

W. Dabrowski61, T. Dado191, T. Dai120, O. Dale17, F. Dallaire126, C. Dallapiccola117, M. Dam58, J. R. Dandoy155, N. P. Dang72,

A. C. Daniells21, N. S. Dann115, M. Danninger224, M. Dano Hoffmann183, V. Dao199, G. Darbo74, S. Darmora10, J. Dassoulas3,

A. Dattagupta148, T. Daubney66, W. Davey29, C. David66, T. Davidek169, M. Davies204, P. Davison109, E. Dawe119, I. Dawson186,

K. De10, R. de Asmundis135, A. De Benedetti145, S. De Castro27,28, S. De Cecco111, N. De Groot138, P. de Jong139, H. De la Torre121,

F. De Lorenzi94, A. De Maria80, D. De Pedis172, A. De Salvo172, U. De Sanctis174,175, A. De Santo200, K. De Vasconcelos Corga116,

J. B. De Vivie De Regie149, W. J. Dearnaley102, R. Debbe36, C. Debenedetti184, D. V. Dedovich95, N. Dehghanian3, I. Deigaard139,

M. Del Gaudio59,60, J. Del Peso113, T. Del Prete157,158, D. Delgove149, F. Deliot183, C. M. Delitzsch73, A. Dell’Acqua46,

L. Dell’Asta30, M. Dell’Orso157,158, M. Della Pietra135,136, D. della Volpe73, M. Delmastro7, C. Delporte149, P. A. Delsart81,

D. A. DeMarco210, S. Demers232, M. Demichev95, A. Demilly111, S. P. Denisov170, D. Denysiuk183, D. Derendarz63,

J. E. Derkaoui181, F. Derue111, P. Dervan105, K. Desch29, C. Deterre66, K. Dette67, P. O. Deviveiros46, A. Dewhurst171, S. Dhaliwal31,

A. Di Ciaccio174,175, L. Di Ciaccio7, W. K. Di Clemente155, C. Di Donato135,136, A. Di Girolamo46, B. Di Girolamo46,

B. Di Micco176,177, R. Di Nardo46, K. F. Di Petrillo82, A. Di Simone72, R. Di Sipio210, D. Di Valentino45, C. Diaconu116,

M. Diamond210, F. A. Dias70, M. A. Diaz48, E. B. Diehl120, J. Dietrich19, S. Díez Cornell66, A. Dimitrievska16, J. Dingfelder29,

P. Dita38, S. Dita38, F. Dittus46, F. Djama116, T. Djobava77, J. I. Djuvsland83, M. A. B. do Vale34, D. Dobos46, M. Dobre38,

C. Doglioni112, J. Dolejsi169, Z. Dolezal169, M. Donadelli35, S. Donati157,158, P. Dondero153,154, J. Donini56, J. Dopke171, A. Doria135,

M. T. Dova101, A. T. Doyle79, E. Drechsler80, M. Dris12, Y. Du54, J. Duarte-Campderros204, E. Duchovni228, G. Duckeck131,

A. Ducourthial111, O. A. Ducu126,p, D. Duda139, A. Dudarev46, A. Chr. Dudder114, E. M. Duffield18, L. Duflot149, M. Dührssen46,

M. Dumancic228, A. E. Dumitriu38, A. K. Duncan79, M. Dunford83, H. Duran Yildiz4, M. Düren78, A. Durglishvili77,

D. Duschinger68, B. Dutta66, M. Dyndal66, C. Eckardt66, K. M. Ecker132, R. C. Edgar120, T. Eifert46, G. Eigen17, K. Einsweiler18,

T. Ekelof221, M. El Kacimi180, R. El Kosseifi116, V. Ellajosyula116, M. Ellert221, S. Elles7, F. Ellinghaus231, A. A. Elliot225, N. Ellis46,

J. Elmsheuser36, M. Elsing46, D. Emeliyanov171, Y. Enari206, O. C. Endner114, J. S. Ennis226, J. Erdmann67, A. Ereditato20,

G. Ernis231, M. Ernst36, S. Errede222, E. Ertel114, M. Escalier149, H. Esch67, C. Escobar159, B. Esposito71, A. I. Etienvre183,

E. Etzion204, H. Evans91, A. Ezhilov156, F. Fabbri27,28, L. Fabbri27,28, G. Facini47, R. M. Fakhrutdinov170, S. Falciano172, R. J. Falla109,

J. Faltova46, Y. Fang50, M. Fanti122,123, A. Farbin10, A. Farilla176, C. Farina159, E. M. Farina153,154, T. Farooque121, S. Farrell18,

S. M. Farrington226, P. Farthouat46, F. Fassi182, P. Fassnacht46, D. Fassouliotis11, M. Faucci Giannelli108, A. Favareto74,75,

W. J. Fawcett152, L. Fayard149, O. L. Fedin156,q, W. Fedorko224, S. Feigl151, L. Feligioni116, C. Feng54, E. J. Feng46, H. Feng120,

A. B. Fenyuk170, L. Feremenga10, P. Fernandez Martinez223, S. Fernandez Perez15, J. Ferrando66, A. Ferrari221, P. Ferrari139,

R. Ferrari153, D. E. Ferreira de Lima84, A. Ferrer223, D. Ferrere73, C. Ferretti120, F. Fiedler114, A. Filipčič106, M. Filipuzzi66,

F. Filthaut138, M. Fincke-Keeler225, K. D. Finelli201, M. C. N. Fiolhais160,162,r, L. Fiorini223, A. Fischer2, C. Fischer15, J. Fischer231,

W. C. Fisher121, N. Flaschel66, I. Fleck188, P. Fleischmann120, R. R. M. Fletcher155, T. Flick231, B. M. Flierl131, L. R. Flores Castillo87,

M. J. Flowerdew132, G. T. Forcolin115, A. Formica183, A. Forti115, A. G. Foster21, D. Fournier149, H. Fox102, S. Fracchia15,

P. Francavilla111, M. Franchini27,28, S. Franchino83, D. Francis46, L. Franconi151, M. Franklin82, M. Frate217, M. Fraternali153,154,

D. Freeborn109, S. M. Fressard-Batraneanu46, B. Freund126, D. Froidevaux46, J. A. Frost152, C. Fukunaga207,

E. Fullana Torregrosa114, T. Fusayasu133, J. Fuster223, C. Gabaldon81, O. Gabizon203, A. Gabrielli27,28, A. Gabrielli18, G. P. Gach61,

S. Gadatsch46, S. Gadomski108, G. Gagliardi74,75, L. G. Gagnon126, P. Gagnon91, C. Galea138, B. Galhardo160,162, E. J. Gallas152,

B. J. Gallop171, P. Gallus168, G. Galster58, K. K. Gan143, S. Ganguly56, J. Gao53, Y. Gao105, Y. S. Gao190,g, F. M. Garay Walls70,

C. García223, J. E. García Navarro223, M. Garcia-Sciveres18, R. W. Gardner47, N. Garelli190, V. Garonne151, A. Gascon Bravo66,

K. Gasnikova66, C. Gatti71, A. Gaudiello74,75, G. Gaudio153, I. L. Gavrilenko127, C. Gay224, G. Gaycken29, E. N. Gazis12,

C. N. P. Gee171, M. Geisen114, M. P. Geisler83, K. Gellerstedt196,197, C. Gemme74, M. H. Genest81, C. Geng53,s, S. Gentile172,173,

C. Gentsos205, S. George108, D. Gerbaudo15, A. Gershon204, S. Ghasemi188, M. Ghneimat29, B. Giacobbe27, S. Giagu172,173,

P. Giannetti157,158, S. M. Gibson108, M. Gignac224, M. Gilchriese18, D. Gillberg45, G. Gilles231, D. M. Gingrich3,d, N. Giokaris11‡,