Creating Sustainable Culture for Sustainability

SVETLANA ESKEBAEKMaster in Leadership for Sustainability

Malmö University, Faculty of Culture and Society, Urban Studies svetlana@eskebaek.net

JEAN-CHARLES E. LANGUILAIRE, PH.D. Assistant Professor in Business Administration, Ph.D. Malmö University, Faculty of Culture and Society, Urban Studies

205 06 Malmö – Sweden; Tel: +46 (0) 704 91 13 78 jean-charles.languilaire@mah.se

Abstract

The rapidly changing environment in which organizations operate demands adequate and fast organizational response. Organizations answer such demand with new forms of organizing among those projects. Project management can be seen as a process tool to react on fast changing environment and to be efficient and competitive. But beyond what could be seen as the structure of the organizations, the major distinguishing feature of successful companies as well as one of the most powerful factors for their success is their organizational culture. Even if in research, there is still no unique definition of organizational culture, there is no disagreement about the importance of organizational culture and its roles for attaining organization coherence and performance. Culture can be seen as the strategic key of a competitive advantage. Beyond such consensus, research is still at its infancy when it comes to understand how to develop a sustainable organizational culture. The question becomes whether project management as a form of organization and a set of tools to implement change could in fact become a tool to develop a sustainable culture. This paper aims at exploring to what extent a sustainable organizational culture for sustainability could be a sustainable outcome of a sustainable project. This paper is largely based on a literature review where few examples are used to illustrate how Agile or Extreme Project Management approaches have been discussed and used as a relevant way to use project tools and techniques to create sustainable organizational culture. The paper also shows the centrality of project as an organizational pattern to develop sustainable culture of adaption and flexibility.

Keywords Organizational culture, project management, sustainability.

INTRODUCTION

Extreme global competition has resulted in an increasingly complicated and unpredictable business environment, where many companies that once prospered are now unable to keep up due to turbulent market conditions. According to Cameron and Quinn (2006) only 16 companies of hundred largest US companies from the beginning of 1900s were still in the market by 2000s, and only 29 companies included in Fortune magazine’s first list were still operational. What makes one company to be successful, while others go out of business, and why are many of the same companies repeatedly on the lists of the best places to work, of the best providers of customer service and of the most profitable within their industries (Heskett, Sasser, & Wheeler, 2008)? Why are they sustainable?

What makes organizations sustainable?

Sustainable organizations could be characterised by two main features: adaptability and organizational culture.

On the one hand, the organizational ability to react on and adapt to changes in their external environment is essential in a rapidly changing world (Kerzner, 2010). For that, organizations have to rethink their way of organizing and operating, where project management becomes a competitive weapon for building a competitive advantage in the aim of the company’s development, survival and sustainability (Kerzner, 2010). Project-based organizations become a new model of organizational structure that enable companies to achieve high performance, increase efficiency and manage organizational change initiatives (Partington, 1996; Sahlin-Andersson & Söderholm, 2002; Whitley, 2006). The fast spread of using projects has received its own name: projectification (Söderlund, 2004a), and projects can be regarded as a sign of speed and as organizational responses. Projects bring flexibility, team spirit and the inclusion of diverse partners in the centre of the organization (Cobb, 2012; Kerzner, 2009; Partington, 1996).

On the other hand, successful sustainable companies' most important asset has been seen to be their organizational culture (Schein, 2010) as it relates to performance (Kotter & Heskett, 1992), long-term effectiveness (Cameron & Quinn, 2006) and competitive advantage (Ramadan, 2009). As summed up by Martins and Terblanche (2003), organizational culture is the key to organizational excellence and is often cited as the primary reason for the failure of implementing organizational change programs (Linnenluecke & Griffiths, 2010). Researchers have suggested that while the tools, techniques and change strategies may be present, failure occurs because the fundamental culture of the organization remains the same (Cameron & Quinn, 2006). This is still proved today in the research of Akins, Bright, Brunson and Wortham (2013) that organizational culture allows organizational adaptability and flexibility playing an important role in the competitive and changing organizational environment, Aditionally, organizational culture is still seen today as impacting organizational performance (Condruz–Băcescu, 2011; Cui & Hu, 2012) and as playing an important role in the growth and development of an organization (Phipps, Prieto & Ndinguri, 2012).

As a whole, sustainable organization may be adaptable and may have a specific culture. But nowadays to what shall organizations adapt to and what should their organizational culture be focused on?

Sustainable organizations for sustainability

As a matter of fact, one of the developments of our modern society is the growing focus on sustainability that can be seen as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (Brundtland Commission of the United Nations, 1987 in Linnenluecke & Griffiths, 2010, p.358). This could be referred as a "sustainable movement". In line with Werther and Chandler (2011) organizational, economic and societal stakeholders are, to diverse extents and in different forms, requesting organizations to participate in the "sustainable movement" by producing services and products that are sustainable and using sustainable processes. All the involved parties must be in agreement on terms and understanding of sustainable. Stakeholders are, in fact, defining sustainability and their views, opinions and beliefs become the context within which the organizations must operate.

Sustainability turns to be marketed, so that organizations answer it with sustainable goods produced using sustainable processes (Werther & Chandler, 2011). Following Werther and Chandler's view on corporate social responsibility (CSR), sustainability can be seen as a threefold concept, namely: a context, an outcome and a process. As a whole, organizations have to adapt to their external more sustainable-oriented environment and aim towards sustainability using sustainable processes. As a result, organizations must integrate sustainability thinking into the entire organizational framework, namely from the strategy to the structure and the processes. Sustainability in organizations may be commonly defined as related to ”environmental integrity and social equity, but also to corporations and economic prosperity” (Linnenluecke & Griffiths, 2010, p.358) so that the organization must systematically re-think how its internal and external actions will be evaluated in terms of sustainability by its diverse stakeholders.

Theoretically, project management enables to bring diverse stakeholders together around one specific goal already at the initial stage of a project, i.e. in the scoping process (Wysocki, 2009). Therefore we believe that to reach a sustainable outcome, projects or project-based work would be a relevant new way of organizing sustainable working processes. To integrate sustainability, organizations and projects should apply a CSR filter (Werther & Chandler, 2011) or more broadly a sustainable filter, questioning all the "whens", "whats", "hows", "whys", "wheres" and ”whos” from a sustainable perspective (see Werther & Chandler, 2011). This sustainable filter should be applied to enable to implement sustainable decisions in organizations and projects. Based on the notion above, a sustainable decision could be defined as a decision of when to implement a sustainable oriented practices in organizations and/or projects in terms of why, where, what and how it should be implemented, not to mention who should oversee the process1. This will enable the threefold element, namely the context, outcome and process to be aligned while the alignment is the central key to sustainability.

Sustainability, project and culture: towards a purpose

As a whole, working in projects could be seen as new ways of working for sustainability but for that to be successful developing a sustainable culture could be seen a sine qua non condition. Our understanding of sustainable culture is based on definition proposed by Bertels, Papania and Papania (2010), in which a culture of sustainability is a culture where “organizational members hold shared assumptions and beliefs about the importance of balancing economic efficiency, social equity and environmental accountability” (p.10). In fact, Thiry and Deguire (2007) indicate that organizing in

1

projects can influence organizational processes and vice-versa. We would like to consider the same dual relationship between sustainable projects and sustainable culture. Whereas the link between project management and sustainability has some support in research, the focus on "sustainable culture" and how a sustainable culture is developed has been under-researched. One reason may be the actual difficulty to conduct change of organizational culture especially the theoretical debate on organizational culture being dictated by an external part or created as social interaction (see in following part). Recognising that project management may provide a sustainable way of working, the purpose of this paper is to explore to what extent a sustainable organizational culture for sustainability could be a sustainable outcome of a sustainable project.

METHOD

The purpose above indicates that we adopt an explorative inference (6 & Bellamy, 2012; Blaikie, 2003). According to Blaikie (2003) to explore means to attempt to develop an initial rough description or, possibly, an understanding of some social phenomenon. The product of explorative inference is a set of claims about any empirical topic for social research (6 & Bellamy, 2012). Explorative inference is well-suited for capturing the complexities, contradictions and change of organizational dynamics as it is open-ended and flexible.

Such exploration is done via a literature review on organizational culture and project management. Indeed, where both fields have been extensively in focus in research, the connection between both and their relation to sustainability is still at its infancy. The secondary data collection started in classical works on project management and organizational culture and an overall thematic research based on the terms: building culture by project, sustainability in project, corporative culture sustainability,

organizational culture project, leadership, stakeholder and sustainability. Thematic management

journals have also been explored especially: International Journal of Project Management, Journal of

Project Management and Journal of Organizational Change Management2. Based on our understanding of organizational culture and project management, we describe and understand to what extent project management tools and processes become essential mechanisms in the development of a sustainable culture. We are looking at commonalities and opportunities to connect both fields.

STRUCTURE OF THE PAPER

The remainder of this paper is based on three parts. The first part reviews our understanding of organizational culture as process and outcome as well as of cultural change. The second part presents our understanding of projects and project management. The third part discusses what forms of projects could be seen as tool to develop sustainable culture aiming at sustainability and to extent these forms contribute to the development of an sustainable organizational culture for sustainability. The last part provides a brief conclusion for this paper.

2

ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE AND CULTURAL CHANGE

The concept of organizational culture derives from the research on culture and has been largely discussed in the management literature (Alvesson, 1993; Schein, 1990; Wilson, 2001). Culture has first been analysed in ethnic and national comparison in fields, such as anthropology, sociology and social psychology (Alvesson, 1993; Schein, 2010; Wilson, 2001). In these studies culture is seen as being in the centre of social relations and people’ behaviours. Culture is also seen as stable in time and as a guideline for appropriate behaviours. Researchers agree that culture is learned, interrelated and shared by individuals (Wilson, 2001). One of the issues in cultural study is the relation between the different cultural layers as far as individuals belong to different “organizations” - from their family to their nation, through their work and professions, clubs and so forth, all of which have specific cultures. These cultural layers are intertwined in a conflict or complementary relations. The concept of culture has later been used in organizational theory, which based its paradigms on the former ideas, concepts and results in cultural literature. In that domain, Schein (1990) argues that the problem of defining organizational culture derives from the fact the concept of culture is itself ambiguous. Martins and Terblance (2003) suggest that perhaps the most commonly known definition of organizational culture, "the way we do things around here", was proposed by Lundy and Cowling in 1996, goes after the formal definition of organizational culture offered in 1984 by Schein:

“organizational culture is the pattern of basic assumptions that a given group has invented, discovered, or developed in learning to cope with its problems of external adaptation and internal integration, and that have worked well enough to be considered valid, and, therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems” (Schein, 1984, p.3).

Numerous issues have been raised when it comes to understanding organizational culture, among them their boundary, their degree of sharing and inconstancies (Wigren, 2003), but above all, the extent to which organizational culture is manageable (Janicijevic, 2011; Schein, 2010). Several theoretical perspectives on organizational culture are present in the literature, among those: “culture as a variable" and “culture as a root metaphor” (Smircich, 1983, p. 347). The two following sections look at these two views and their connection with cultural change is then discussed.

Culture as a variable, an outcome or a product

The first perspective explicitly suggests that culture in the organization is manageable. Managers have to act on its antecedents, among those leadership (Wilson, 2001). Schein (1984, 2010) can be seen as a part of this line of thoughts, when he describes the content of organizational culture as (1) cognitive such as assumptions, values, norms and attitudes and (2) symbolic elements such as materialistic, semantic and behavioural symbols. Schein has created a conceptual framework for analysing and intervening in the culture of organization. In particular, according to Schein (1984) organizational culture exists and can be analysed simultaneously on three different levels: observable artefacts, espoused values and basic underlying assumptions:

Artefacts are the first and the most evident components of culture, which one can see, hear and feel. It is the constructed environment of the organization and among the other includes its

architecture, technology, office layout, dress code, visible or audible behaviour patterns and public documents such as charter, employee orientation material and stories.

Espoused values are the next level of culture. They refer to the norms that provide day-to-day principles by which members of an organization guide their behaviour. Espoused values allow analysing members’ behaviour in general and reasons that govern their behaviour in particular. These are conceptions of the way things should be that are clearly communicated and consciously understood. A company’s mission statement is an example of an artefact that represents their espoused values.

Basic underlying assumptions represent the final level of culture which are typically unconscious and present the picture how group members perceive, think and feel. These ideas or beliefs are so ingrained in the culture that they go largely unnoticed. They are essentially invisible. Unlike values, they are not directly communicated. They are taken for granted. However, once uncovered, their meaning is very clear and they illuminate previously discovered values and artefacts.

This view suggests that culture could be managed, changed and used as a means to achieving greater organizational outcomes. In this respect, leadership style and national and personal values of the company’s founders influence the creation of organizational culture (Schein, 2010). Leadership can change artefacts and values to enable new culture to be created. The basic underlying assumptions are often disregarded in that view. This view is about understanding culture as what an organization has.

Culture as a root metaphor, social interaction or social process

The second perspective using a root-metaphor "organization as a culture" suggests that organizations are creating meanings and values through the social relations established between people within the organization (Meyerson & Martin, 1987; Wigren, 2003). Understanding organization as culture implies that organizational culture is the “glue” that enables people in the same organization to stick together (Alvesson, 1993). It is like air, impossible to see and to feel, but necessary to live. In that sense, culture Can be defined as:

“a shared and learned world of experiences, meanings, values and understanding which inform people and which are expressed, reproduced, and communicated partly in symbolic form” (Alvesson, 1993, p.2)

This view is also reflected on Hatch (1993) who offers a revision of Schein’s model by introducing a cultural dynamic model, where the processes of manifestation, realization, symbolization and interpretation are combined. This model underlines the social interaction. The proposed cultural dynamics model reformulate Schein's original model in terms of process by making a place for symbols, assumptions, values and artefacts. Hatch (1993) suggests that

”the new goal be an explanation of organizational culture as the dynamic construction and reconstruction of cultural geography and history as contexts for taking action, making meaning, constructing images, and forming identities” (p.686).

Lim (1995) among other models examines the process-oriented approaches to organizational culture, which views organizational culture as a continuous development of shared meanings. Martins and Terblanche (2003) claim that based on Schein’s model 1985 open system approach has emerged. The

open system approach explains the interaction between such organizational sub-systems as goals, structure, management, technology and psycho-sociology. This complex interaction between individuals and groups within the organization on the one hand, and with other organizations and the external environment on the other hand, can be seen as the primary determinant of behaviour in the workplace. The open system approach allows investigating the interdependence, interaction and interrelationship between the different sub-systems and elements of organizational culture in an organization (Martins & Terblanche, 2003). Culture is about what an organization is and no longer about what the organization has. In that case, culture is difficult to grasp and to change. Changing the culture implies in-depth changes of structures and working norms but above all new social interaction enabling new underlying assumption to be developed. Indeed, with time, it can change especially with the renewal of employees. It can be argue that a careful recruitment aiming at finding individuals with an appropriate culture can lead to cultural change (Meyerson & Martin, 1987).

Organizational cultural creation, development and change

Accordingly, from both perspectives, a leeway for cultural change exists. In fact, researchers from both perspectives agree that culture evolves, but they argue differently on the degree of ease with which the organizational can change (Wilson, 2001). In the service management context, Edvardsson and Enquist (2002) suggest that the "service culture" gives guidelines for action and meaning to what is to be done and how activities should be carried out at different levels of the organization. Such an understanding of culture re-conciliates both viewpoints. Therefore, the two viewpoints should not be seen as opposing one another. The culture of an organization can be seen, in fact, as a social construction that is both a product and a process (Kathryn, 2011).

“It’s a product when it comes in the form of wisdom accumulated and passed on to others, and it’s a process because it gets renewed and recreated” (Bolman & Deal, 2003 in Kathryn 2011, p.597) Heskett et al. (2008) claim that there is a pattern in the actions and activities involved in developing strong and adaptive cultures. As culture is learned and when an organization consistently builds and reinforces such a culture, it creates a competitive edge that is hard to replicate. Organizational culture is an asset that money cannot buy and it is a factor that can make or break a business (Ramadan, 2010). That is why, according to Ramadan (2010), a company should invest in the number of training hours devoted annually to each employee. Schein claim that cultural change does not occurs even if it is announced as a primary goal; changes take place when leaders set some new goals to achieve or identify some problems that need to be solved (Schein, 2010). The psycho-social dynamics of organizational change is tightly bounded with the leadership role.

Schneider, Brief and Guzzo (1996) claim that cultural changes can be introduced by changing policies, practices, procedures and routines that altogether affect the beliefs and values, which govern employees’ behaviour. They review diverse tactics, which behavioural researches have used in attempts to change organizations and offers models and methods for comprehensive organizational change (Schneider et al., 1996). These, for example, include particular interventions with the purpose to support changes in organizations as a whole, including their goals and the way they operate in (total quality management). Moreover, they underline the role of organizational climate and culture for long-term organizational change (Schneider et al., 1996). Organizations are closely associated with their members, thus, if the people in organizations do not change, there is also no organizational change. Changes in organizations

at all levels, such as organizational structure, hierarchy, technology and communication, can be implemented successfully if changes are accepted and associated with changes in the psychology of employees. Changes will not solely occur just through introduction of a new mission, speeches, meetings, new motto and corporative parties or even through changing the organizational structure (Schneider et al., 1996). To communicate new values and beliefs successfully requires changing thousands of tangible, which define climate and daily life in an organization (Pervaiz, 1998, Schein 2010). Organizational culture refers to deeply held beliefs and values; climate reflects the tangibles that produce a culture, the kinds of things that happen to and around employees that they are able to describe (Pervaiz, 1998). Culture is therefore, in a sense, a reflection of climate, but operates on a deeper level. In a more practical way, Heskett et al. (2008) offer several suggestions on how strong organizational culture can be created and nurtured (Table 1).

Table 1: Actions for creating strong organizational culture (based on Heskett et al., 2008)

1. Leadership: Leaders should establish clear organizational mission and vision and values and set the example by themselves.

2. Reinforcement and investment in culture on a continuous basis. Team successes and individual accomplishment should be praised and noticed.

3. Fairness of leadership. Employees judge every management decision on the scale of fairness.

4. Organizations with clearly codified cultures enjoy labour cost advantages.

5. Employees and customers loyalty.

6. The result of all is "the best serving the best!"

7. Periodic revision of the company’s core values and search for best practices both inside and outside the organization.

An understanding of culture

All in all in terms of cultural change, few "visible" or "explicit" cultural aspects among those are artifacts, values and climate may be "manageable" as products so that they can be changed by external forces such as new policies but for the cultural change to be successful and sustainable, these explicit changes will need to be embedded in "deeper, visible or implicit" culture aspects (some values, norms and cultural assumptions) that are often the result of new social interactions in the organization. Integrating our understanding of culture and/or cultural change into a definition results in considering organizational culture as follows:

organizational culture is a social process and a set of values, norms and assumptions that are developed and sustained in this social process. It is composed of a visible/explicit culture and an invisible/implicit culture. The explicit culture is defined and communicated by the management in and out side the organizational boundaries, and guide action and meaning to what is to be done, and how activities should be carried out at different levels of the organization. The implicit culture is the results of the daily human, social and personal interactions between individuals in the organizational boundaries.

PROJECT MANAGEMENT AND PROJECTS

Project management is a complicated versatile empirical phenomenon defined by researchers in many different ways: as a managerial process or as a system approach or as a “temporary organization” (Kerzner, 2009, Söderlund, 2004a, Söderlund, 2004b). In 2009, Kerzner defined project management as

“the planning, organizing, directing, and controlling of company resources for a relatively short-term objective that has been established to complete specific goals and objectives” (Kerzner, 2009, p.4).

Project management has evolved from a set of processes that were once considered as nice to have and matured over the last half century (Kerzner, 2010). As underlined in the introduction, project management is one of the competitive advantages of companies and creates benefits in terms of building credibility, creating growth and providing cost control and safety of time and resources (Partington, 1996; Sahlin-Andersson & Söderholm, 2002; Whitley, 2006). Project Management can be treated as a “method” for solving complex organizational problems and the project phenomenon is important to understand the modern companies (Söderlund, 2004a; Söderlund, 2004b). In the next section, we will explain what a project is as well as the different types of projects.

What is a project?

Different views on the project are expressed by different researches (Söderlund, 2004b); however, two major streams in project management research consider projects as unique and temporary. Projects are unique in terms of outcome they produce, and projects are also temporary endeavours. Wysocki (2009) defines project as:

“a sequence of unique, complex, and connected activities having one goal or purpose and that must be completed by a specific time, within budget, and according to specification” (Wysocki, 2009, p.6).

Furthermore, the Project Management Institute defines a project” as a temporary endeavour undertaken to create a unique product, service or result” (cited in Cobb, 2012, p.11). The inclusion of projects as temporary organizations is to oppose a project with formal organization whose mission is a higher degree and thus longer term. Projects are generally constructed or created as parts of an “ordinary” organization and therefore are related to each other (Lundin & Steinthorsson, 2003). This can lead to project-based organizations or projectified organizations (Sahlin-Andersson & Söderholm, 2002; Söderlund, 2004a). Organizations are composed of "temporary organizations”, called projects. This notion goes in line with Turner and Müller's (2003) definition of a project as:

“a project is a temporary organization to which resources are assigned to undertake a unique, novel and transient endeavour managing the inherent uncertainty and need for integration in order to deliver beneficial objectives of change” (p.3).

Projects landscape

Projects take various shapes and sizes, from the small and straight forward to extremely large and highly complex (Kerzner, 2009; Wysocki, 2009). Projects uncover processes of planning, organizing, securing,

managing, leading and controlling resources to achieve specific goals. For that matter, the project landscape serves as a visual map to categorize types of projects and select an adequate Project Management Life Cycle (PMLC) model that will fit the aim/goal of the project and the solution/the processes of the project (Cobb, 2012; Wysocki, 2009).

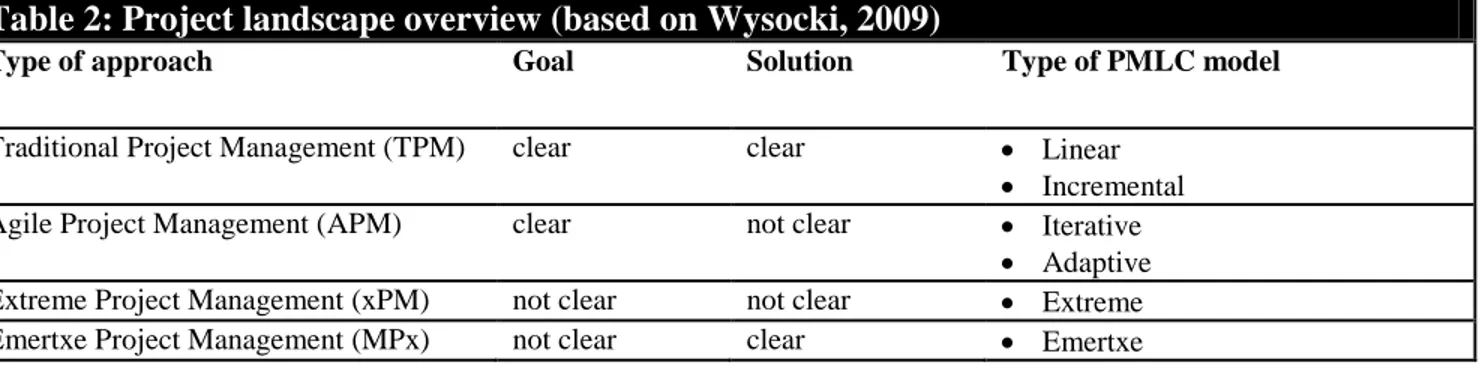

In 2009 Wysocki offered to use two variables, namely goal and solution in order to define the project landscape. Goals and solutions can each take on two values: either clear or not clear and therefore, there exists four different variants of relationship between these two variables that, in turn, leads to four types of approaches: Traditional, Agile, Extreme and Emertxe project management approach (Table 2). For Wysocki (2009), all projects fall into one of these four types. Five process groups of the PMLC include: (1) scoping, (2) planning, (3) launching, (4) monitoring and controlling, and (5) closing (Cobb, 2012; Wysocki, 2009).

As accepted in the project management literature and in line with Wysocki (2009) and Cobb (2012), each PMLC is composed of five sequential process groups: (1) scoping, (2) planning, (3) launching, (4) monitoring and controlling, and (5) closing. However, the sequences between these processes vary leading to diverse PMLC models: Linear, Incremental, Iterative Adaptive, Extreme or Emertxe. Use as a tool, PMLC indicates how the processes are organized in order for the project to be successful (see Table 2).

Table 2: Project landscape overview (based on Wysocki, 2009)

Type of approach Goal Solution Type of PMLC model

Traditional Project Management (TPM) clear clear Linear

Incremental

Agile Project Management (APM) clear not clear Iterative

Adaptive

Extreme Project Management (xPM) not clear not clear Extreme

Emertxe Project Management (MPx) not clear clear Emertxe

Based on Table 2, one can see that TPM projects are the simplest of all possible project situations, but the least likely to occur in today’s continuously changing business environment. They are plan-driven projects and can be managed by Linear and Incremental approaches. APM projects are continuously growing and can be managed by Iterative and Adaptive approaches, where the constant analysis of the situation during the life cycle of the project takes place. xPM projects are dealing with scenario of not clear goal - not clear solution. They are entirely different class of projects that are the least structured. xPM approach offers the way to manage the uncertainty and complexity of situation in order to minimize a high risk of failure. Mpx projects as a backwards version of an extreme project can be managed by xPM approach.

Wysocki (2009) continues that each of these models presents different challenges to the project managers. The design, adaptation and deployment of project management life cycles and models are based on the changing characteristics of the project and are the guiding principles behind practicing effective project management. Consequently, the question we raise is what are the types of projects and project management life cycle models that are suitable for creating a sustainable culture? This question will be discussed in the next part.

A SUSTAINABLE CULTURE FOR SUSTAINABILITY

At the starting point of this paper it has been indicated that sustainable organizations are dependent on their adaptability that can be given via project management and their organizational culture that in turn, in our modern context has to be aligned with the sustainable movement. Therefore, organizations have to create and develop a sustainable culture, and the project may be used as a tool for such development. In line with the project landscape, it becomes central to identify what type of project has to be developed. For that matter, understanding sustainability as part of the "scoping" process (definition of the aim of project) is essential. First, we start our discussion with sustainability and then connect it with types of projects that could be used to develop a sustainable culture. It finally reflects on why these types of projects are relevant to creating culture for sustainability.

Sustainability and introducing sustainability in organization

In line with the “sustainable movement” identified in the introduction of this paper, humanity has reached the critical level for people and the planet with profound changes for human health and wellbeing and the nature of the environment. Within society, growing number of proactive organizations recognize the benefits and the potential return of moving towards sustainability. In the last decade, sustainability has become an increasingly integral part of doing business in any industry. Sustainability in relation to organizations is often referred as corporative sustainability (Linnenluecke & Griffiths, 2010). For companies to balance their financial, social and environmental risks, obligations and opportunities, sustainability must move from being an add-on to “just the way we do things around here” (Bertels et al., 2010, p.8). Business sustainability is becoming a prerequisite for global competitiveness and companies worldwide are aligning their core competencies and business processes with the principles and objectives of sustainable development (Labuschagne & Brent, 2005). Several recent studies have pointed to external and internal organizational pressure for adopting sustainability practices (Linnenluecke & Griffiths, 2010), where, for instance, company’s reputation as well as job satisfaction have become important characteristics for external and internal stakeholders to demonstrate their loyalty to the company that, in turn, leads to company’s competitive advantage (Werther & Chandler, 2011). When it comes to adopting sustainability in organizations at corporate and project levels, Keeble, Topiol and Berkeley (2003) develop indicators to measure sustainability performance. Keeble et al. (2003) suggest three main areas to concentrate on: (1) involvement of all members of the company in deciding on primary indicators and after that concentrating on delivering results, (2) involvement of external stakeholders in developing indicators, here project managers have to achieve sustainable results through their own decision-making and (3) sustainable results that are gained by united efforts and ensure the results are truly embedded in the company and reflect the company’s values. These three areas reveal that in order to integrate sustainability it requires leadership involvement to commit all the members of the organization. The goals must be agreed and understood by all. Additionally, the processes that have to be followed must also be agreed and understood by projects managers who lead the projects independently. Finally, to enable that sustainability must be anchored in values so that the team members will be lead by values and not only by directives. All in all, this indicates that leadership as a process of influence, where, what and how to achieve, is required and must be understood and agreed upon by team members (Yulk, 2006). Beyond this aspect, no indication of how to build a sustainable culture is given.

Similarly, Linnenluecke and Griffiths (2010) state that on a surface level of organizational interaction, the adaptation of corporate sustainability practices becomes visible through the publication of sustainability reports, the integration of sustainability measures in company’s and employees’ performance evaluation, technical solutions etc. Linnenluecke and Griffiths (2010) continue that on a value level, integration of sustainability practices goes through changes in a company’s values and beliefs towards more ethical and responsible values; and on an underlying level, the integration of sustainability practices take place through a change in core assumptions. Consequently, integrating sustainability is seen by Linnenluecke and Griffiths (2010) as a culture change, where different levels must be reached. This goes in line with our understanding of culture, where an explicit and an implicit part of culture must be developed to enable the organizational culture change to be sucessfull. However, here again, no clear indication on how this is done is provided.

As a whole, as any company’s sustainable efforts start inside the organization, sustainability issue has become a challenge for leadership (Thomason & Marquis, 2010). Leaders have to set and communicate sustainability goals, articulate how they will be achieved and engage all levels of the organization in problem solving and implementation. As organizations work through these changes, business leaders are starting to recognize that organizational culture plays a fundamental role in the shift toward sustainability. The challenges are how to make it happen.

What types of projects for sustainability?

To understand how to create sustainable culture as an outcome of a project the characteristics of the future project have to be clearly identified and addressed to the business situation the company is in: what do we have to do, how do we have to do it and how will we know we reach our initial goal? To start to elaborate on a project the project landscape should be done (Cobb, 2012; Wysocki, 2009). A project manager role is first to define relationship between goal and solution, and then the extent to which the goal and the solution of the project given are clear or not clear (Wysocki, 2009).

In our context, the ultimate goal of the project is to create a sustainable organizational culture (for sustainability). Sustainable culture is a multidimensional phenomenon and there are many elements that can reflect the "soul" of organizational culture (Phipps et al., 2012). As cultural phenomenon is composed of visible/explicit and invisible/ implicit characteristics, indicating that our goal – the culture can be regarded both as clear and not clear. On the one hand, clear goals may come from understanding of organizational culture as a discrete entity. In this respect, organizational culture is one of the components of an organization, so an organization has a culture and the culture has its purpose and function. In line with seeing organizational culture as an outcome and following the notion that organizational culture could be managed means that it is possible to enforce a set of clear goals by applying clear instructions and giving directions. The goal, for instance, can be to alter structures, policies, strategies, recruitment, cultural values and assumptions. The values stress the importance of people and processes that can create change with emphasis on competent leadership throughout all managerial levels. On the other hand, not well controllable social processes make the goal of creating sustainable culture not clear. These unclear goals come from understanding that organizational culture is the reality itself. This notion is related to organizational culture as a root metaphor. Culture exists as a pattern of symbolic relationships and meanings sustained through the processes of human interaction. Sustainability issues add additional uncertainty in setting the goals as the company should develop and agree upon sustainability indicators; and whether the company is planning to focus on business,

environmental and social sustainability or only on one of sustainability components. The leaders should constantly monitor changes in the company’s environment and adjust strategies and practices to keep the company and its culture closely aligned with its operating environment. The value system that drives cultural adjustments should be focused on the company’s key stakeholders needs. On the other hand, the company’s external stakeholders might have their own perception of sustainability that is not always in line with the company’s strategies.

Solutions are rarely clear even if culture is seen as an outcome and therefore it is possible to develop guidelines and perform training in an attempt to influence the wanted changes in culture (Schein, 2010). As underlined in the previous section, several activities can be done and leaders may find several practical advices to affect culture. On the other hand, when seeing an organization as culture, the development of social interaction is not planed and cannot be controlled as such. In this respect solutions are largely unclear. The same as seen for the goals, sustainability issues add uncertainty to solutions. Sustainability as a concept is ambiguous by itself and therefore creates different understanding: whether it is conscientious integration of social, environmental and economic concerns in the organizational culture or it is external pressure in terms of regulations, standards and laws that makes the organization to react (Linnenluecke & Griffiths, 2010). In this respect it influences and determines organizational decisions and actions.

Combining goals and solutions and finding out what type of project is relevant to creating a sustainable culture is related to what views one will have on culture, whether culture is manageable as an object or is manageable as it is social. Nonetheless, we have been looking at these two views not as opposed but as two types of elements in the culture, the explicit and the implicit, which are related to each other. Hereby, we argue that as a whole, goals are clear, when it comes to visible elements of culture but unclear when it comes to the deep values and culture assumptions in the organizations. Solutions, however, are not given in any case. Even if creating artefacts could be seen as clear, artefacts must be genially seen as having a role to be relevant. If not they will be ignored. Creating "good" artefacts is neither clear nor simple. Thus, we argue that the project of creating sustainable culture tends to have a clear goal for explicit part of the culture and unclear goal for implicit part of culture and not clear solution. All in all, in agreement with the project landscape, this implies that Agile project management and Extreme project management are to be considered as relevant project management types for creating a sustainable culture. The choice of project management approach is based on analysing the project specifics and defining an approach that is best applicable and makes sense.

Agile and Extreme project management as relevant "tool" for sustainable culture

As the decision about the landscape is clear, the project can move further to the five processes of PMLC: scoping; planning; launching; monitoring and controlling and closing (Cobb, 2012; Wysocki, 2009). In line with the project landscape (see Table 2), three PMLC models are possible namely iterative, adaptive or extreme. Figure 1 presents the three models respectively.

Iterative

Adaptive

Extreme

Figure 1: Iterative, Adaptive, and Extreme PMLC models (based on Wysocki, 2009)

When it comes to change the explicit part of the culture, it becomes interesting to look at the differences between iterative and adaptive as goals will be more clear but solution unclear. In this case adopting APM approach gives the project adaptability and flexibility. Different situations occur during PMLC require different approaches as the solutions move from clear towards those solutions that are not clearly specified. Iterative PMLC model is better to apply when some of the features are missing or not clearly defined. Adaptive PMLC model is better to apply when the solution is less clearly specified - functions, as well as, features are missing or not clearly defined (Picture 1). This may be illustrated with the adoption of “sustainable report” that can be run as project where few guidelines have to be followed depending of the industry and where goals in terms of diverse stakeholders could be identified and controlled so that when it is in lines with guidelines the project can be closed.

When it comes to change the implicit part of the culture, it becomes interesting to look at the differences between iterative and extreme life cycle, knowing that having an Extreme would be more relevant. As it can be observed from Picture 1, the main difference between APM and xPM models is lying in the scoping process. In AMP project scoping is done at the beginning of the project. In xPM project scoping is adjusted at each stage. The scoping process starts with the general statement of the goals and business value of the project, making sure that all involved parties understand the big picture (Wysocki, 2009). This phase is extremely important because here the true needs of the client are extracted and for the final success of the project has the beginning from here. Interests of stakeholders should be included and considered at the earliest stage to avoid and reduce risks in the future. A clear understanding of the project scope is critical to the planning and execution phases of the project.

Extreme project is unstructured and designed to handle projects with ‘‘fuzzy goals’’ or goals that cannot be defined because of the exploratory nature of the extreme project (Picture 1). If it is not possible to clarify the goal from the beginning, the project management have to move forth and back to accomplish both with clarification of the goal and solution. The project starts with the goal as a guess and tries to achieve the situation, where goal and solution converge on some points. During each iteration the learning and discovery take place between the project team and the client to move the project ahead. xPM requires the client to be more involved within and between phases. In many xPM projects, the client takes a leadership position instead of the collaborative position that the client takes in APM projects. So the top managers in the host organization lead the project together with the project manager, who is more likely a representative of the board directors or is one of the top HR managers.

The type of the project very much depends on the parameters that are set for the final outcome. Culture can be looked upon through different dimensions, and the focus or choice of the particular dimensions will define the type of project. For example, if the goal as sustainable culture can be interpreted and put into parameters, such as training hours or number of workshop (see table 1 before), in this respect the project will tend to have clear goal- not clear solution. Hence, APM approach can be applied to construct the project. Else, focus on the issues like changing climate, raise the awareness for sustainability, the project will tend to have not clear goal-not clear solution. Hence, xPM approach can be applied to construct the project.

Why agile and extreme project are relevant: Leadership and Stakeholders as a key to success

Having discussed Agile and Extreme project management, we can see that their relevancy for creating a sustainable culture lies onto 2 majors characteristics: leadership and stakeholders. These characteristics must be related to the explicit and implicit level culture that must combined to successfully create a sustainable culture for sustainability.

A leadership argument

Stakeholders’ involvement as it has been stated should be done at the earliest phases of PMLC and for that matter, there are different techniques for the broader stakeholders’ involvement. In a project aiming at “Creating sustainable culture for sustainability”, the project manager should be particularly skilled to communicate effectively with both team members and stakeholders. Active listening is a key skill to employ in the mutual communication. As the purpose of the project is to change and deliver sustainable cultural values to the host organization, bridging the gap between the project team and the other stakeholders is another challenge for the project management. Cobb (2012) claims that the literature has traditionally focused on two dimension of leadership: the task and the social-psychological dimensions. Project tools help leaders do a variety of task work, including clarifying the project’s mission and objectives; planning, organizing, and structuring project work; coordinating the flow of resources and task outputs; and controlling the operational side of project work. The social-psychological dimension of leadership focuses on leaders actions in the social context and leader-subordinate relationships: leading project team and dealing with stakeholders. Leaders have to staff, develop, motivate and ensure commitment from their project teams. Social context includes stakeholders as well and leaders have to take into account their interests and needs. Project leaders must be able to communicate effectively with both team members and stakeholders, they bridge the gap between their teams and the project’s other stakeholders (Cobb, 2012).

Four main leadership tasks were underlined by Zairi and Al-Mashari in 2005: (1) leaders exert leadership in the planning of the project through clarity of vision, formulating and communicating strategy and developing goals and outcomes; ( 2) they have the responsibility of following closely the implementation of projects through proper gatekeeping, monitoring and reviewing outcomes; (3) they allow teams enough flexibility to deal with issues, to carry out execution of the project and use innovative ways for achieving time-to-market measures; (4) teams have to be empowered by senior managers to make decisions and own the projects and guide them successfully.

Leadership can be examined in the context of doing the right things in the right time. One of the most important factors for high performance is a clear vision. Cleland (1995) attracts attention to other key issues that leaders must consider: (1) the identification, development and communication of a vision for the project stakeholders as the most important factor for high performance is a clear vision; (2) identifying the resources for realizing the vision; (3) the conceptualization and designation of the project’s organizational design to align the people and the resources to facilitate the accomplishment of the vision; (4) the commitment of the stakeholders in supporting the leader’s initiatives in attainment of the vision. The communication skills of the leader and the followers are important in gaining and retaining this commitment.

Finally, for the success of the project the success of the team and team effectiveness is important to consider. This is also a leadership issues. To construct the team leaders need to decide about team structure: team size, time composition and team governance. It is an additional challenge for the project manager to create an efficiently performing team and decide about team composition and team governance. The other factors as identity, interaction and ideology should also be taken into account. There is no magic number for the time size- it all depends on the project’s task. Team composition very much depends on the nature of the task that should be done too. Team governance and team control are very important factors for the project success. It shows the authority structure and there are four basic types to consider: (1) managed-led teams that have little control over their operation and are told what to do and how to do; (2) self-managed teams that can manage their own operations when the goals are set; (3) self-directed teams that develop their own goal within the broader scope of the larger organization’s mission and (4) self-governing teams that have the authority to develop the general mission of the organization and how it is to be pursued (Cobb, 2012). It can be argued that there are two choices between models of governance in our project that seems to be appropriate: a directed team or a self-governing team. We believe that a self-directed team, where the team develops their own goal within the broader scope of the larger organization’s mission, is applicable for Agile PMLC. A self-governing team, which has the authority to develop the general mission of the organization and how it is to be pursued, basically exists extremely rare and almost never found among project teams. This variant is usually reserved for top management teams of organizations and seems as a logical fit for our project based on Extreme PMLC model. By that we propose the composition for the project (Table3).

Table 3: Proposed construction of the project

Type of project Team governance composition

Agile Project Management Self-directed team

Extreme Project Management Self-governing team

Different styles and leadership behaviour are needed to respond to different situations that might occur during the project life cycle. Leaders’ role here is both external and internal. There are different priorities and requirements depending on the stage of PMLC, and to meet the expectations of different

group of stakeholders is one of the challenges of the project. Project leaders have to influence different groups of stakeholders. The influence comes through charisma, knowledge, skills, political savvy, networks, interpersonal skills, the ability to communicate, empathy and coaching techniques.

As a whole, we believe that project management enables the “leadership” perspective to be operationalized and this becomes central when the aim of the “projects” is to develop a sustainable culture.

A stakeholder argument

Projects never exist in isolation and no project is on an island (Engwall, 2003). They are surrounded by a network of stakeholders, often with different interests in the project, who can determine its success or failure. That is why the sense-making activities of project participants are import for producing sustainable outcome (Alderman, Ivory , McLoughlin & Vaughan, 2005). In other terms, it is indeed at the end stakeholders who will decide and judge on the sustainability process and outcome given by the projects. To understand who project thinking especially Agile and Extreme project management enable sustainable organization to emerge, lets first have a look at the diverse categories of stakeholders. Each project has its own unique profile of stakeholders. Olander (2007) cites Freeman (1984) who describes the concept of stakeholders as any group or individual who can affect, or is affected by, the achievement of a corporation’s purpose. Olander goes further and defines a project stakeholder as

“a person or group of people who has a vested interest in the success of a project and the environment within which the project operates” (p.279).

A first way to look at stakeholders is to think of two categories of stakeholder: internal and external. Internal stakeholders are those who actively involved in project execution; and external stakeholders are those who are affected by the project. It is important to recognize all the stakeholders in order to meet their needs. When it comes to culture, employees inside the organization may be seen as the internal stakeholders as they will be the first impacted with culture. Thus, there need to have projects to develop artefacts for the internal stakeholders and for example “sustainable workshop” or “use of sustainable material” could be seen as project build to create such artefacts and this can be done with Agile project management. When it comes to deeper and invisible level of culture it is about changing relationships between people and this will requires constant questioning of the meaning of sustainability and this more Extreme project management. External stakeholders will be clients or society and here again artefacts like sustainable report can be developed as “agile projects”.

Another way to look at stakeholders is to think in terms of classes. Classes of stakeholders can be identified by their possession of one, two or all three of the following attributes: (1) first class refers to the stakeholder’s power to influence; (2) second class underlines the legitimacy of stakeholder relationships; (3) third class deals with the urgency. In accordance with stakeholders attributes Mitchell et al. (1997) cited by Olander (2007) define different stakeholder classes. There are seven different classes of stakeholders: dormant, discretionary, demanding, dominant, dangerous, dependent and definitive stakeholders. Olander’s notion that some of stakeholders are more important than others and should be prioritized go in line with the same ideas of Werther and Chandler (2011) in terms of sustaibaility. Priorities and concerns change over time and new classes and configurations of

stakeholders appear in response to changing circumstances (Olander, 2007). The author states that managers need to assess each stakeholder’s interest in order to express its expectations on project decisions and if there is the power to follow it through. Johnson and Scholes (1999) cited by Olander (2007) propose a stakeholder mapping technique, the power-interest matrix, for stakeholders’ evaluation. In the power-interest matrix, project stakeholders can be categorized depending on their power towards the project and their level of interest. They identify seven groups of stakeholders and offers mapping technique with stakeholders’ impact index. Based on the mapping technique, a stakeholder management process can be established. Stakeholder analysis based on the stakeholder impact index can be used as a planning and as an evaluation tool. This mapping technique can be used to structure the project stakeholders and their influence on the project especially in the scoping phase. When in extreme situation when it comes to deeper level changes of culture this must be done regularly as the project life cycle requires a loop at the scoping phase.

Yet another way to categorize and look at profile stakeholders is offered by Cobb in 2012. He divided stakeholders into eight groups. There are three particularly important groups of stakeholders: the project clients, the managers of the organization that hosts the project and the project team. The remaining five are: external suppliers, internal suppliers, regulators, end users and implementers, and political stakeholders. Project stakeholders are tied to each other and form project networks. By building ties and strong connections, leaders increase and develop social capital. The success of their project very much depends on their ability to develop ties with the broader number of stakeholders in the project network. Project leaders should start developing their social capital early in the planning phase of a project by identifying stakeholders and making contacts with them. As the project progresses, the leader needs to spend more time with the more influential stakeholders of the project. As the number and types of stakeholders may be seen as increasing, thus enabling deeper change of the culture will again be require Extreme project management and vice-versa, Extreme project management will enable to continuously reflect on this set of diverse stakeholders.

As we have seen above, a critical element is the inclusion of stakeholders at the start of the project. Indeed, in the early project planning stage, leaders need to identify all those stakeholders who will play important decision-making and resource-sharing roles for the project. The project leaders have to assess the stakeholder’s interests in the project, their influence on the project and their true role. Cobb (2012) continues that building social network is important for project success. As the project progresses, project leaders need to spend time working with the more influential stakeholders and those who have access to important project resources. It is important that project leaders perform these kinds of networking tasks. The social capital gained via project networks provides project leaders with the information, support and other resources that they need to be successful. Olander (2007) argues that it is not enough simply to identify stakeholders. He suggests that, in fact, little is known about the nature of the various project stakeholders, “who they are, what their drivers and separate agendas are, and how to understand the nature of project stakeholder trade-offs” (p.283). The management of internal and external stakeholders represents a challenge that most project managers are only just beginning to acknowledge (Cova & Salle, 2005).

As a whole, we believe that project management enables the “stakeholders” perspective to be operationalized and included and this becomes central when the aim of the “projects” is to develop a sustainable culture.

CONCLUSION

The purpose of this paper was to explore to what extent a sustainable organizational culture for sustainability could be a sustainable outcome of a sustainable project. To provide the sustainable outcome of the project, the project life cycle should be sustainable. Sustainability is a leadership challenge and requires constant questioning of its meaning by the diverse stakeholders. We believe that adopting a project thinking when wishing to develop a sustainable culture is essential. Project management enables to re-put the focus on leadership and on stakeholders that are central to the development of both levels of the organizational culture. However we believe that to develop each level, two types of projects must be developed. Agile projects can enable to enhance the development of visible part of the culture whereas extreme projects can enable to enhance the development of invisible part of the culture which requires more time and more reflection of the scope and meaning of sustainability. Artefacts could be created with clearer goals and clearer solutions than social relation. As a whole, we would like to suggest that changing what the organization has can be done via Agile project management whereas changing what the organization is can be done via Extreme project management. As both aspects (has and is) must be managed by leaders seeking cultural change, we suggest that creating a sustainable organization is a balance between Agile and Extreme project management where both forms of projects will enable leadership issues and stakeholders issues to be in the centre of the cultural change. The process of the overall project aiming at creating a sustainable culture (outcome) will be sustainable if balancing agile and extreme project and if this is made while reflecting of the stakeholders in the context/environment of the organization. Figure 2 summarises our thoughts:

Figure 2: Balance between Agile and Extreme project management for developing a sustainable culture

Visible part of Culture (artefacts, few values and norms)

• AGILE PROJECT MANAGEMENT

Invisible part of culture (few values and norms and deepen culture assumptions) • EXTREME PROJECT MANAGEMENT SUSTAINABLE CULTURE Diverse Stakeholders

REFERENCES

6, P., & Bellamy, C. (2012). Principles of methodology. Research design in social science. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publication.

Alderman, N., Ivory, C., McLoughlin, I., & Vaughan, R. (2005). Sense-making as a process within complex service-led projects. International Journal of Project Management, 23(5), 380-385.

Alvesson, M. (1993). Cultural perspectives on organizations. Cambrigde: Cambridge University Press. Akins, R., Bright, B., Brunson, T., & Wortham, W. (2013). Effective Leadership for Sustainable Development. Journal of Organizational Learning and Leadership, 11(1), 29-36.

Bertels, S., Papania, L., & Papania, D. (2010). Embedding sustainability in organizational culture. Retrieved from http://nbs.net/wp-content/uploads/dec6_embedding_sustainability.pdf

Blaikie, N. (2003). Analyzing quantitative data. From description to explanation. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publication.

Cameron, K. S., & Quinn, R. E. (2006). Diagnosing and changing organizational culture: based on the

competing value framework (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Wiley.

Cleland, D. I. (1995, April). Leadership and the project-management body of knowledge. International

Journal of Project Management, 13(2), 83-88.

Cobb, A. T. (2012). Leading project teams: the basics of project management and team leadership (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

Condruz–Băcescu, M. (2011). Enterprise Culture. Synergy, 7(1), 102-108.

Cova, B. & Salle, R. (2005, July). Six key points to merge project marketing into project management.

International Journal of Project Management, 23(5), 354-359.

Cui, X., & Hu, J. (2012). A literature review on organization culture and corporate performance.

International Journal of Business Administration, 3(2), 28.

Edvardsson, B., & Enquist , B. (2002). ’The IKEA saga’: How service culture drives service strategy.

The Service Industries Journal, 22(4), 153-186.

Engwall, M. (2003). No project is an island: linking projects to history and context. Research policy,

32(5), 789-808.

Hatch, M. J. (1993, October). The dynamics of organizational culture. The Academy of Management

Review, 18(4), 657-693.

Heskett, J., Sasser, W. E., & Wheeler, J. (2008). Ten reason to design a better corporate culture. Retrieved from Harvard Business School http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/5917.html

Janicijevic, N. (2011, April – June). Methodological approaches in the research of organizational culture. Economic Annals, 56(189), 66-99.

Kathryn, A.A. (Ed.). (2011). Leadership in non-profit organizations: a reference book. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Keeble, J. J., Topiol, S., & Berkeley, S. (2003, May). Using indicators to measure sustainability performance at a corporate and project level. Journal of Business Ethics, 44(2), 149-158.

Kerzner, H. (2009). Project management: a system approach to planning, scheduling, and controlling. (10th ed.). Hoboken: Wiley.

Kerzner, H. (2010). Project Management: Best Practices - Achieving Global Excellence. (2nd ed.). Hoboken: Wiley.

Kotter, J.P., & Heskett J. L. (1992). Corporate culture and performance. New York: Free Press. Labuschagne, C. & Brent, A. C. (2005, February). Sustainable project life cycle management: aligning project management methodologies with the principles of sustainable development. International

Journal of Project Management, 23(2), 159-168.

Linnenluecke, M. K., & Griffiths, A. (2010). Corporate sustainability and organizational culture.

Journal of World Business, 45(4), 357-366.

Lim, B. (1995). Examining the organizational culture and organizational performance link. Leadership

& Organization Development Journal, 16(5).

Lundin, R. A., & Steinthorsson, R. S. (2003, June). Studying organizations as temporary. Scandinavian

Journal of Project Management, 19(2), 233-250.

Martins, E. C., & Terblanche F. (2003). Building organisational culture that stimulates creativity and innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management, 6(1), 64-74.

Meyerson, D., & Martin, J. (1987). Cultural Change: An integration of three different views. Journal of

Management Studies, 24 (6), 623-647.

Olander, S. (2007, March). Stakeholder impact analysis in construction project management.

Construction Management and Economics, 25(3), 277-287.

Partington, D. (1996, February). The project management of organizational change. International

Journal of Project Management, 14(1), 13-21.

Pervaiz, A. (1998). Culture and climate for innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management,