Degree Project in Criminology Malmö University

120 Credits Two-year master Faculty of Health and Society Criminology Master´s Programme 205 06 Malmö

0

AGE-SPECIFIC RISK FACTORS

FOR RADICALIZATION

MOVING BEYOND IDEOLOGY

JESPER BLOMBERG

1

AGE-SPECIFIC RISK FACTORS

FOR RADICALIZATION

MOVING BEYOND IDEOLOGY

JESPER BLOMBERG

Blomberg, J. Age-specific risk factors for radicalization. Moving beyond ideology.

Degree project in Criminology 30 Credits. Malmö University: Faculty of Health and

Society, Department of Criminology, 2020.

Introduction. This study examines age-specific risk factors associated with

radicalization that could contribute to Swedish research and responsible investigative authorities. Specific knowledge of individual risk factors for radicalization is limited, especially compared to what we know about other forms of violence.

Methods. A total of 1240 cases were included after a data cleaning of the PIRUS-dataset. An exploratory factor analysis examined youths (<21), adults (>22), and a no age-specific group.

Results. The radicalized youths tend to have more often been abused as children, had some traumatic experience, and are currently part of a gang. In comparison, the radicalized adults tend to live an unstructured life with drug or alcohol addiction, have an already radicalized friend, and have actively searched for their radicalized group. The no age-specific group shares some variables with the youths and other variables with the adults, indicating a need for age-specific analysis.

Conclusion. The results imply a need for specified risk factors according to age. The age-specific analysis provides a deepened understanding of age-specific risk factors that contribute to radicalization and make individuals susceptible to radicalized groups. Since different authorities are responsible for youths and adults and already work with a risk factor approach, the findings in this essay imply that the authorities should investigate their current policies and update them to age-specific risk factors.

Keywords: Age-specific, PIRUS, Psychological Vulnerabilities, Radicalization, Risk

2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1.0 INTRODUCTION 3

1.1AIM AND RESEARCH QUESTIONS 4

2.0 CONTEXT, CONCEPT & KNOWLEDGE 5

2.1THE SWEDISH CONTEXT 5

2.2CONCEPTUALIZATION 5

2.3CURRENT AGE-SPECIFIC UNDERSTANDING 6

2.4THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK 7

3.0 METHODS AND ETHICS 9

3.1DATASET 9 3.2DATA CLEANING 9 3.3VARIABLES 9 3.4ANALYTICAL TECHNIQUE 10 3.5FACTORS 10 3.6MISSING CASES 11 3.7ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS 12 4.0 RESULTS 12 4.1DESCRIPTIVES 12

4.2FOUR FACTOR MODEL 13

4.3ONE FACTOR MODEL 16

5.0 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION 17

5.1WHAT AGE-SPECIFIC RISK FACTORS CONTRIBUTE TO RADICALIZATION AND MAKE INDIVIDUALS SUSCEPTIBLE TO RADICALIZED GROUPS? 18

5.2HOW DO THESE RESULTS COMPARE TO OUR CURRENT UNDERSTANDING OF RADICALIZATION IN SWEDEN AND AGE-SPECIFIC RISK FACTORS? 19

5.3VICTIM OFFENDER OVERLAP 20

5.4WHAT IMPLICATIONS COULD THE RESULTS HAVE FOR THE RESPONSIBLE

INVESTIGATIVE AUTHORITIES? 21

5.5LIMITATIONS 21

6.0 CONCLUSION 22

7.0 REFERENCES 23

3

1.0 INTRODUCTION

Radicalism has in the last decade transformed in western Europe as we witness numerous examples of new models of acts of terror and the formation of radical groups with a younger homegrown population (Campelo et al. 2018; Harpviken 2019; Horgan 2009). The violence associated with radicalization has escalated in Sweden (Rostami et al. 2018), and a governmental research anthology (SOU 2017:67) identified an extensive requisite of research regarding radicalization. According to official data, which Rostami et al. (2018) have taken part of, 25 % of all crimes committed in Sweden derive to violent radicalism. That percentage also includes organized gang-related crimes. The Swedish intelligence agency (SÄPO)

distinguishes between organized gang-related crimes and violent radicalism (Säkerhetspolisen 2018). One of these differences is that organized gangs commit crime more frequently and their crimes are associated with drug dealing and violence, while most of the crimes committed by radical groups are less severe and of other crime types. SÄPO (Säkerhetspolisen 2018) assesses that both Islamic-, right-wing- and left-wing- radical groups have the potential to cause a terror attack, but that the Islamic terrorist groups are the most present threat. The right wing- and left-wing terrorist groups share the goal to overthrow the governmental system but use more long term and less extreme tactics. Instead of using brutal large-scale attacks, they use other forms of violence, threats, and harassments to affect politics at large, stopping opposing groups to meet and stop individuals from entering politics

(Säkerhetspolisen 2018). The Swedish government has increased the focus on violent radicalism since 2014 (skr. 2014/15:146).

In the mists of the Syrian war and terror attacks across the world, the Swedish government began to develop new strategies to "prevent, avert and obstruct" acts of terror (skr. 2014/15:146). This declaration of intent led to preventive efforts for radicalized youths through the Swedish child protection agency and the child ombudsman (Ku2016/02295/D, Ku2016/02294/D, Ku2016/02296/D), increased penalties for acts of terror and increased usage of classified methods for the intelligence agency (SOU 2019:49, 2019/20:JuU19) and the creation of the Center Against Violent Extremism (CVE), a governmental radicalization coordinator and international collaborations (CVE: SFS 2017:1159, coordinator: Dir. 2014:103, international collaborations: the RAN network, the EU High-Level Commission Expert Group on Radicalization, Strong Cities Network and Nordic Safe Cities). SÄPO state that Islamic acts of terror often gets most of our attention but in a long-term perspective, the right-wing and left-wing radicals and is equal as a threat to our democratic society:

"The operations in the white supremacy and the autonomous environment extend beyond large-scale, brutal violent crimes with massive casualties, and more in a systematic manner to use violence,

4 threats, and harassment to abrogate or amend our democratic

government." (My translation from SÄPO 2019)

According to the European Union (2019), in 2018, the latest published official Europol data, 129 foiled, failed, and completed terror attacks were reported by EU member states. Sixty of these terror attacks took place in the UK, of which 54 relates to the conflict between England and Northern Ireland. After the UK, the highest rate of terrorist attacks occurs in France, Italy, Spain, Greece, Netherlands, Germany, Belgium, and Sweden. Eighty-three terror attacks were related to separatist

movements in the UK, France, and Spain, Islamic radicals performed 24 of the terror attacks, and the left-wing radicals conducted 19. Out of 1056 arrests on suspicion of radicalization-related offenses in the EU, 511 were Islamic radicals, 44 were right-wing radicals, and 34 were left-right-wing radicals (ibid). The global trend indicates a growth of right-wing radicalism in the last decade. The Global Terrorism Index (2019) presents a 320 % increment of radical actions by the right-wing radicalism in the last five years in the western European countries.

Recent research has shifted the focus from why specific individuals radicalize to ideology-driven radical groups, to which specific risk factors contribute to radicalization, and make individuals more susceptible to radicalized groups to increase the understanding of the last decade's transformation of radicalism in Western Europe.

1.1 Aim and research questions

The aim of this essay is to construct clusters of age-specific risk factors that contribute to radicalization and make individuals more susceptible to radicalized groups. The research questions are thus:

Q1 What age-specific risk factors contribute to radicalization and make individuals susceptible to radicalized groups in the PIRUS dataset? Q2 How do these results compare to our current understanding of

radicalization in Sweden and age-specific risk factors? Q3 What implications could the results have for the responsible

investigative authorities?

Specific knowledge of individual risk factors for radicalization is remarkably limited, especially compared to what we know about other forms of violence (Sturup & Långström 2017). Even though the research gap is more extensive in some continents (Douglass & Rondeaux 2017), much research is still warranted in Europe (Pisoui & Reem 2016) and Sweden specifically (SOU 2017:67 Edling & Rostami 2017). The ongoing and recently published Swedish research (see: Rostami et al. 2018; Carlsson 2015; Edling & Rostami 2017 and Kaati 2019) identifies some specific societal problems, such as why Swedish authorities only identify 20 % of radicalized youths (Rostami et al. 2018). One reason could be that previous research has focused on why individuals radicalize and create profiles with inadequate empirical evidence (Horgan

5 2009; Borum 2011a). Recent research, however, focuses more on risk factors

(Horgan 2009) and psychological vulnerabilities among youths (Altier et al. 2014; Harpviken 2019; Borum 2014) to improve the empirical evidence.

2.0 CONTEXT, CONCEPT & KNOWLEDGE

2.1 The Swedish context

One extensive government public investigation (Swedish: Statens Offentliga Utredningar, SOU, SOU 2017:67), examined what areas of violent radicalism demand further research. The results include the roles of gender in extremist

environments, responsibilities of the civil society, the meaning behind the ideology of violent radicalism, parliamentary collaborations, and how violent radical groups interact. Furthermore, the authors conclude that academic research should combine different methodological traditions, combine academic disciplines, and be studied from different perspectives to increase the potential of policymaking.

The Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency has financed a project targeting the overlap of organized crime and radicalized groups (Rostami et al. 2018). Their database consists of information from, including but not limited to, the intelligence agency, the police authority, The Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention, and the child protection agency. The project aim is to investigate the mechanisms for radicalized groups to form and through which processes individuals join them (Rostami et al. 2018). According to their dataset, radical Islamic groups consist of 785 individuals in Sweden, the right-wing radical of 382, the left-wing radical of 193, and there are 281 "other" radicals in Sweden. The mean age for both left- and right-wing radicals is 23 and for Islamic radicals 26. The gender balance is heavy on the male side, with close to 90 % men in right-wing and Islamic radicals and just above 80 % of men in left-wing radical groups. Islamic radicals in Sweden tend to have a lower education level, with over 5 % not graduating from elementary school and left-wing radicals who tend to have higher education with 20 % graduating university. The presented theoretical radicalization pathway presented in Rostami et al. (2018) consists of three steps: A weakened social control, for example, being expelled from school, is followed by an interaction with the radicalized group. According to the theory, those who join the radicalized group are those who internalize the philosophy, meaning, and moral of the group.

2.2 Conceptualization

The concept of radicalization is originally political in the sense that it is

conceptualized by politicians claiming antagonistic and anti-democratic groups as hostile to the state (Lööw 2017). In a scientific context, radicalization is a concept that describes the end position in a spectrum: a political or religious spectrum. In this essay, the shared definition of radicalization by Swedish research (Rostami et al. 2018, Carlsson 2015, Edling & Rostami 2017 and Kaati 2019), the Swedish

6 intelligence agency (Säkerhetspolisen 2018) and the Swedish government (SOU 2017:67; SOU 2019:49) will be applied. Simplified, a violent individual becomes radical when he/she has ideological motives, and these are the criteria for inclusion the dataset (PIRUS 2020)

In the Swedish context, radical groups are defined as våldsbejakande extremism, which could translate into advocacy of violent extremism or follow research in English, radicalization. The concept of advocating for violence implicates a conceptual drift since the individual does not need to be violent, only to support or promote violence as a method is sufficient to be included (Carlsson 2015). Exactly where the demarcation is drawn is different from different institutions. The benefit of the conceptual drift is that leading individuals in radical organizations might never take part in violent acts but are still significant research subjects. Groups who do not advocate for violence should not be included since violence is harmful, not the opinions, in a democratic society.

While some research projects only include one type of ideology, this essay follows the Swedish tradition of including both Islamic radicalism, left-wing radicalism, and right-wing radicalism (Rostami et al. 2018; Carlsson 2015; Edling & Rostami 2017; Kaati 2019). The intuitive research approach to radicalization is to separate the different groups due to their obvious and apparent differences concerning origin, targets, and ideology. Research has found that it is not clear which pathways to radicalization are the most common (McGilloway 2015; Horgan 2004, 2008, 2009; The Council of the European Union 2018). There are apparent differences in

geographic origin, who the enemy is and the ideology (Carlsson 2015, Rostami et al. 2018), but viewing the quantitative results much of the differences are statistically significant, but not practically relevant. Rostami et al. (2018) concluded that the differences are too small between the ideological groups with several internal

conflicting results that it is more pertinent to view the radicalized groups as one from a life-course perspective. The results from both qualitative and quantitative data showed a stronger correlation with concepts like the age-crime curve, transitions, and trajectories than differences between the ideologies (ibid.). Age is a more substantial variable for violence than ideology if we accept the assumption that age is a primary variable for radicalization, as it is for most crimes, it is of most critical matter to focus our attention on the young ones (Hirschi & Gottfredson 1983). Our current

understanding of radicalization is low, peculiarly if we accept different risk factors, causal mechanisms, and functioning programs depending on age. Rostami et al. (2018) show that less than 20% of radicalized youths in Sweden were identified and investigated by the responsible authority. That only 20 % are identified is considered as a low figure, and it is. From another perspective, 80 % of radicalized individuals can continue their radicalization process without any intervention, and the end of that process is a highly dangerous lifestyle.

2.3 Current age-specific understanding

Although there is no age-specific research of radicalization in Sweden, there are examples in other western European countries. In the last decade, a rise in

7 radicalization among youths in western Europe has created new models of

radicalization with smaller radical groups, which are less hierarchical and consist of younger homegrown individuals (Campelo et al. 2018; Harpviken 2019). New

research targets the correlation between adolescent development and radicalization to address the shift in the radicalization paradigm. Youths have always been highly susceptible to radicalization with an overall young median age (Campelo et al. 2018; Harpviken 2019). Adolescence, in itself, is a risk factor for radicalization since this is a period in life when individuals break themselves free from childhood and

commence to create identities detached from their parents (ibid.). The world begins to make an effect and belonging to a community or group transmits social inclusion, an understanding of meaning in life, and comfort. Qualitative research concludes that radicalized groups take advantage of this developmental stage in adolescence (Campelo et al. 2018).

Oppetit (et al. 2019) compared radical Islamic minors to adults in Belgium between 2014 and 2016. The results of the age-specific comparison suggested that minors are more psychologically vulnerable and initiate their radicalization process online while the adult population is more often affected by perceived discrimination and become radicalized in their neighborhood. Horgan (2004; Altier et al. 2014) argued that the tradition of conceptualizing mental illness only as psychiatric diagnoses impedes the psychological aspects of radicalization. To continue how adolescent developmental struggles can make them susceptible to radicalization, researchers try to

reconceptualize mental illness to include more subtle areas of psychology (Harpviken 2019). Borum (2014) stated that psychological vulnerabilities such as perceived discrimination, early socialization, mental illness, potentially traumatic experiences, social capital, and delinquency (Altier et al. 2014; Harpviken 2019), hold much potential as causal factors for radicalization. In literature reviews of current research in the western European context, the concept of psychological vulnerabilities has a substantial impact on radicalization in western Europe and is dependent on adolescent development (Campelo et al. 2018; Harpviken 2019). The results of these studies should be handled with caution since the research is skewed. The literature review by Campelo (et al. 2018) includes 22 articles, of which 20 only included radical

Islamism. In the review by Harpviken (2019), more than half of the articles included had no definition of radicalization. To build policies on empirical evidence which is potentially skewed can lead to accusatory interventions with poor results.

2.4 Theoretical framework

The professional and academic literature has, for a long time, focused on why individuals radicalize and less on how (Borum 2011a, Horgan 2009). To answer the research question of why someone would radicalize, the research community has formulated many theories for profiling the radicalized individual. These profiling theories lack empirical evidence and are therefore misleading (Horgan 2009, Borum 2011a). The theoretical foundation has since then developed into a more process-oriented approach to the entire radicalization process, from entry to de-radicalization. The process-oriented approach includes multiple theories, and the most relevant theory for this dataset and aim is the risk factor approach, or push and pull factors as

8 some call it (Horgan 2009). Other promising theories, such as the social movement theory (Borum 2011a, Borum 2011b), are equally important and are used by Rostami et al. (2018) and Bouzar (2019). As SOU 2017:67 concluded, it is preferable to include other theories, disciplines, and methodologies. Ali et al. (2017) make a good case on that existing research have constructed many clusters of risk factors, profiles, and processes, but have still not clarified precisely when or how these clusters are significantly likely to ignite a radicalization process, or how these conditions, characteristics, and cognitions may de-radicalize someone. They (Ali et al. 2017) instead focus on what values and meanings are behind the radicalization process and apply qualitative methods to a broader understanding of radicalization.

The use of risk and protective factors originates from the 1980s and has been adopted with a variety of results (Kraemer et al. 1997; Harris & Rice 2015). Risk factors are the probability of a negative outcome of a variable within a population of subjects, and protective factors are positive outcomes. There are two typologies of risk factors (Kraemer et al. 1997; Harris & Rice 2015). Some risk factors cannot be changed, such as ethnicity, year of birth, or gender (in a traditional sense), and are therefore

static. In contrast, some risk factors are possible to change to various degrees. Age is

a variable that changes every year, but cannot be changed by treatment and is referred to as variable markers. Variables then can change with treatment, e.g., weight, but have not yet shown to alter the likelihood of having an impact of the measure, e.g., radicalization, is referred to as potentially dynamic. The third type of dynamic risk factor is the causal; those can change by treatment and are proved to have an impact on the measure (ibid.).

Although risk and protective factors cumulate and increase the contingency of radicalization (ibid.), it is misleading to understand the risk factor approach as predeterminism. The radicalized population is small, and their characteristics change over time, depending on country and context, and the individual life circumstances develop and change (Borum 2011a; Carlsson 2015). Furthermore, since everyone has risk and protective factors, some risks have a higher impact than others. An

individual with a high risk of radicalization might not radicalize, while someone else would. Over 20 years of research yielded low empirical support for what the causal relationship between risk and violence is, how different risk factors affect each other, when a change starts or if that change is the change that leads to the wanted effect (Harris & Rice 2015). No one knows if changes in any risk factors can be reliably achieved. Therefore, no one knows how to produce changes in any risk factors that can be assumed to cause parallel changes in violent behavior. Regardless, in practice, it is still important to have empirical evidence on risk factors. Often the investigative authorities know a small portion of a problem and needs an objective information as a method to increase the understanding. The responsible authority with the legal

responsibility for radicalized youth in Sweden is entirely based on the risk factor approach with the structure of the Risk-Need-Responsivity-model (Harris & Rice 2015). The benefit of applying a risk factor approach to research is, therefore, the ability to practically apply the results. The practitioners can easily understand the

9 research conclusions, be transformed into policies, and be compared with existing knowledge.

3.0 METHODS AND ETHICS

3.1 Dataset

The Profiles of Individual Radicalization in the United States (PIRUS 2020) is an open-sourced de-identified quantitative and cross-sectional dataset of 2148 individuals espousing Islamic, right-wing, left-wing radicalism and atheistic lone actors, both violent and non-violent. The PIRUS-dataset covers the years 1948-2017 in the United States, and many variables are presented on an individual level. The included individuals have been radicalized in the United States espousing ideological motives when being arrested, indicted for a crime, killed in action, or was associated with an extremist organization. The dataset was coded using open-source material, including, but not limited to, court records, police reports, journalistic articles, websites (both governmental and extremist organization), secondary data sets, and peer-reviewed academic articles.

3.2 Data cleaning

The PIRUS-dataset consists of 112 variables with a high rate of missing cases. The data collection method also leads to a variation of answer alternatives for the variables. The first step, therefore, was to clean the dataset (Osborne 2005). All the variables are examined and recoded into the same configuration to find missing cases. Since age is a determining variable, all cases in which age was missing were

excluded, and the remaining cases were coded into a binary separation at the age of 21. The dataset was split into three different age-groups, one with every case from the dataset (ALL), one with everyone aged 21 and under (<21), and the third group with every case aged 22 and over (>22). The three age-groups were analyzed precisely in the same manner. All cases prior to the year 2000 were excluded according to a meta-perspective. The society today is very different from the middle of the 20th century. Internet, globalization, and the "war against terrorism" have completely changed how we live, the ruling politics, and radicalization.

3.3 Variables

The ambition was to include as many variables as possible. Some of the variables in the dataset overlapped each other and were excluded. One example of this is variables 2 through 10, which consist of if the individual planned, executed, and completed a violent plot. By including variables 4 and 9, much of the conceptualization is included. The disadvantage of this selection of variables is, for example, the loss of nuances as when, where, against who and how much security was operationalized. Some variables were excluded since they only concern adults, such as if the

individual had been victimized in adult age. After selecting the conforming variable, 34 variables were used in the factor analysis. Variables available in the dataset are listed in table 1.

10 3.4 Analytical technique

In multivariate analysis, two methods are among the most popular, principal component analysis (PCA) and the factor analysis (Unkel & Trendafilov 2010; Russel 2002; Costello & Osborne 2005). PCA is often the default setting in software packages as SPSS but is criticized for being a simple descriptive technique (ibid.). The benefit of a factor analysis is that it does not only reduce variables, like PCA, but mathematically reveals all variances and correlations among the variables regardless of the risk of any researcher bias (Costello & Osborne 2005). In this essay, the linear factor analytical model, exploratory factor analysis (EFA), is being preferred before nonlinear techniques, to identify age differences without making any prior

assumptions about which variables are related to which factors (Unkel & Trendafilov 2010). The ambition is to move beyond prior assumptions, preconceptions, and researcher bias to identify what factors are most related to radicalization depending on age.

The methodological process consists of extraction, rotation, and interpretation. The factor extraction model of choice is the Maximum Likelihood since the data is close to normally distributed (Costello & Osborne 2005). Further analysis was executed using Principal Axis Factoring to increase the reliability of the essay. Costello and Osborne (2005) explain the difference between the extraction methods Maximum Likelihood and Principal Axis Factoring but suggest that both should be tested, and if there are substantial differences in the results, further analysis can be made. The results in this essay showed little, if any, difference. Because the difference is irrelevant, only Maximum Likelihood extraction is presented in this essay since it is proven to be the best in most cases (Osborne 2014). Both Oblimin and Promax rotation were tested, and because Promax yielded the best results in all the three age groups, Promax is the rotation method presented.

3.5 Factors

There are several ways to select how many factors should be included in the results. In this essay, both the Kaiser Criterion, the scree plot, and parallel analysis were tested in all three age-groups (appendix 4-9) (O´Connor 2000). The parallel analysis (appendix 4-6) concluded that a maximum of 31 factors for 32 variables was possible while the Kaiser Criterion concluded that 11 factors were possible (a sum over 1.0) for the All-group, 13 factors for the <21-group and 14 factors for the >22-group. Osborne (2014) discusses how important it is for the results to be interpretable and argue that no more than five factors should be included in the results. If none of the above methods are relevant, the researcher could choose factors according to a theory. That is not relevant for this essay since the aim is to present results insensible of previous assumptions. The last remaining method is to look at the scree plot (appendix 7-9) (Osborne 2014). Examining the scree plot, a commonality between the age-groups is clear, with four factors having a more robust explained variance than the others. The benefit of using the Kaiser Criterion with a sum of 1.0 would be to increase the explained variance, although is between 11 and 14 factors not

11

with the limitation of the disadvantage of lower total explained variance (around 25 %) but are easily interpreted, presented, and construct practically relevant results.

The saliency criteria for including variables are .3. According to meta-analyses, many researchers use different cut-offs from .2 to .8, often without any reasoning, and one-third of all researchers do not even have a cut off (Osborne 2014). These presented results are based on a cut off at .3, while all variable scores are included in appendix 1 to 3 (Unkel & Trendafilov 2010; Russel 2002; Costello & Osborne 2005). It is problematic with a static cut off when a variable such as loss of social standing and

alcohol or drug abuse has values just below .3 and is not included while previous criminal activity and radical family is included with values just above .3.

In the result section are each age-group presented in separate diagrams. In the

four-factor model, are the four four-factors with the highest explained variance presented

(figure 1-3). In the one-factor model is all three age-groups factor 1 presented in the same diagram (figure 4). The presented results are all variables with a coefficient score over .3 in the rotated structure matrix. Both rotated pattern matrix and rotated structure matrix are attached in appendix 1 to 3. It is essential to read both the pattern coefficients and the structure coefficients in factor analysis (Unkel & Trendafilov 2010; Russel 2002; Costello & Osborne 2005). The results of the rotated pattern matrix (the coefficients) provide information on how much of each variable it takes to construct the factor. The pattern coefficients are similar to ingredients in a recipe. The rotated structure matrix results further calculate the bivariate correlations that

together compute the factor (Thompson 2004, Osborne 2014). If the factors were utterly uncorrelated, the pattern and structure coefficients would be the same. Reading the table charts (appendix 1-3), we can see that the difference between the pattern coefficients and structure coefficients are minimal, indicating that the factors are close to uncorrelated.

3.6 Missing cases

Missing cases are always a problem in criminology, especially in research on

radicalization. The PIRUS (2020) dataset, which uses open sources, struggles perhaps even more. Viewing the descriptives, the number of missing cases is unfortunately high. Missing cases, however, is not always a reason to not use the data. There have

been a couple of valid conclusions from this dataset, see for example, Lafree et al.,

2018, Jensen et al., 2018 and Jasko et al., 2017. To handle missing cases, regression and multiple imputations have emerged as two progressive methods (Osborne 2014), and the other way is to simply not count them. The multiple imputations are most recommended and should not bias the results (Osborne 2014; Graham 2009; Gold & Bentler 2000). I would argue that this dataset is so flawed with the number of missing cases that any input data will affect the results. If the majority of the cases are

missing, they will overtake the results and decimate the practical relevance.

Therefore, the missing cases were excluded with a simple removal by excluding them pairwise. There is no perfect way of handling the missing cases. They are too many. There is a need for both national and international datasets with better data.

12 3.7 Ethical considerations

There are multiple ethical issues concerning both the research participants and the researcher him/herself to consider when performing research (Kumar 2014). The researcher is responsible for discussing and considering ethical aspects and

consequences of the involvement of potentially sensitive personal information such as ethnic origin, criminal activity, or religion concerning the research participants. In the PIRUS-dataset are the individual cases thoroughly anonymized. The individual cases cannot be identified by the variables since the data collection covers over 60 years. The data collection is additionally constructed of official data that is not covered by any privacy law, and the information could nevertheless be sensitive. The

anonymization protects those rights. The ethics are limited by the lack of consent and autonomy, which increases the significance of confidentiality, privacy, and dignity (ibid). Other aspects of important ethical aspects to consider is the role of the researcher (ibid). For this essay, no salary, provision, or sponsoring organization affects the researcher bias. The results are presented in a whole to guarantee further that the reader can follow the methodology, results, and analytical process to strengthen the reliability.

4.0 RESULTS

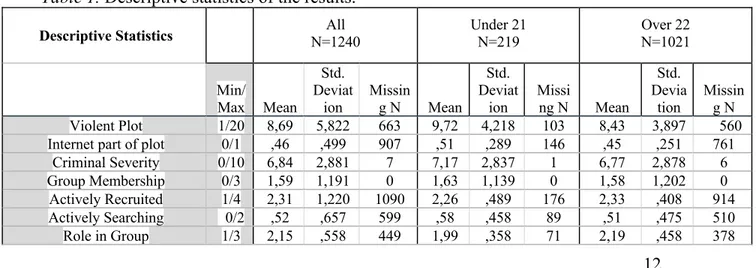

4.1 Descriptive statistics

The descriptive statistics of the three age-groups are presented in table 1. The >22-group (n=1021) is close to five times larger than <21->22-group (n=219). The number of answer alternatives, min/max, varies from indicator variables with only two answer alternatives to variables such as violent plot with 20 answer alternatives. The mean indicates that some variables are more skewed than others, such as gender (1.92 of 2),

gang member (0.1 of 1), and abused as child (0.07 of 3). Some standard deviations

are larger than others, such as violent plot (5.8), religious background (4.8), and

criminal severity (2.9), indicating a larger variation among the cases. A larger

variation induces fewer individual cases per characteristic and potentially complicates the identification of commonalities and correlations in the dataset.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the results.

Descriptive Statistics N=1240 All Under 21 N=219 Over 22 N=1021

Min/ Max Mean Std. Deviat ion Missin g N Mean Std. Deviat ion Missi ng N Mean Std. Devia tion Missin g N Violent Plot 1/20 8,69 5,822 663 9,72 4,218 103 8,43 3,897 560 Internet part of plot 0/1 ,46 ,499 907 ,51 ,289 146 ,45 ,251 761

Criminal Severity 0/10 6,84 2,881 7 7,17 2,837 1 6,77 2,878 6 Group Membership 0/3 1,59 1,191 0 1,63 1,139 0 1,58 1,202 0 Actively Recruited 1/4 2,31 1,220 1090 2,26 ,489 176 2,33 ,408 914 Actively Searching 0/2 ,52 ,657 599 ,58 ,458 89 ,51 ,475 510 Role in Group 1/3 2,15 ,558 449 1,99 ,358 71 2,19 ,458 378

13

Online Radicalization 0/2 1,02 ,612 613 1,20 ,451 81 ,97 ,425 532 Media Radicalization 0/2 ,64 ,623 830 ,71 ,365 137 ,62 ,356 693 Social Media Radicalization 0/2 ,70 ,649 637 ,96 ,449 106 ,63 ,442 531 Duration of Radicalization 0/2 2,14 ,718 695 1,73 ,425 110 2,24 ,464 585 Radical Ideology 0/5 3,43 1,587 152 3,42 1,444 29 3,43 1,496 123 Radicalization Sequence 1/3 1,23 ,597 610 1,31 ,540 91 1,20 ,395 519 Radicalization in Institution 0/2 ,31 ,641 786 ,38 ,384 125 ,30 ,388 661 Ethnicity 1/7 3,14 1,015 70 3,06 1,132 16 3,16 ,952 54 Gender 1/2 1,92 ,276 0 1,93 ,253 0 1,91 ,281 0 Religious Background 1/18 6,07 4,812 755 4,96 3,297 114 6,38 2,916 641 Immigrant Generation 0/2 ,31 ,584 86 ,48 ,688 22 ,28 ,527 64 Education level 1/8 4,27 2,178 649 3,25 ,951 62 4,64 1,527 587 Employment Status 1/5 2,35 1,585 593 3,65 1,216 103 2,07 1,021 490 Social Stratum Childhood 1/3 1,92 ,598 920 1,91 ,327 132 1,92 ,298 788

Abused as Child 0/3 ,07 ,353 0 ,08 ,374 0 ,06 ,348 0 Mental Illness 0/2 ,24 ,581 0 ,26 ,616 0 ,23 ,574 0 Alcohol/Drug Abuse 0/1 ,14 ,347 0 ,11 ,319 0 ,14 ,352 0 Absent Parents 0/3 ,66 1,030 906 ,68 ,677 118 ,64 ,498 788 Criminality Family 0/2 1,11 1,003 901 1,00 ,575 146 1,14 ,511 755 Radicalized Friend 0/3 1,90 1,147 482 1,94 1,072 45 1,89 ,855 437 Radicalized Family 0/3 ,61 1,064 821 ,54 ,810 94 ,61 ,681 602 Unstructured Time 0/1 ,38 ,485 676 ,44 ,359 105 ,36 ,319 571 Expelled 0/1 ,19 ,395 893 ,21 ,225 152 ,19 ,205 741

Previous Criminal Activity 0/3 ,95 1,234 358 ,29 ,649 64 1,09 1,070 294

Gang Member 0/1 ,01 ,150 0 0 ,068 0 ,02 ,162 0

Traumatic Experience 0/3 ,54 ,907 863 ,49 ,497 140 ,56 ,501 723 Loss of Social Standing 0/3 ,32 ,783 884 ,37 ,472 150 ,31 ,407 728

Furthermore, it is worth noticing that there are many missing cases, and some variables suffer more than others. In the variable actively recruited, there are 1090 missing cases out of 1240, in the social stratum childhood variable 920 out of 1240 cases are missing, and in the internet part of plot are 907 of 1240 cases missing. In those variables with zero missing cases, such as gang member, is it difficult to assess if that answer alternative is a missing case or not because the variable includes the answer alternative "not member of a group". Selecting the answer alternative could be based on the absence of information ergo, not a member of a group.

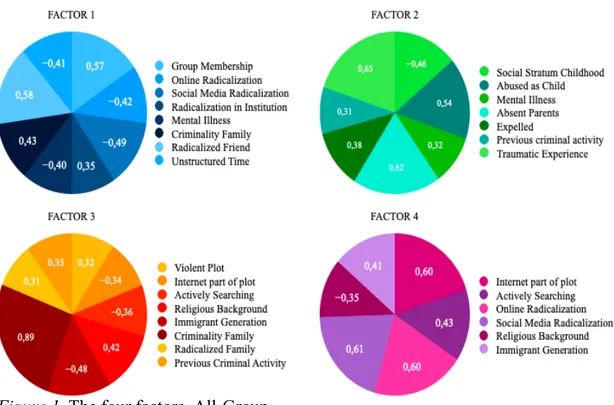

4.2 Four Factor Model

The exploratory factor analysis results are presented in figures 1, 2, 3, and 4. The complete table charts are attached in appendix 1 to 3. The diagrams (figure 1-3) are the four factors for all the age-groups. The presented results are all variables with a coefficient score over .3 in the rotated structure matrix. The extraction method was Maximum Likelihood and rotated with Promax as recommended by Costello and Osborne (2005).

4.2.1 All-group

The total explained variance of the four factors in the All-group (n=1240) is 31.8%, which is, in a practical sense, a low figure. Over 62 % of the variance among the variables is not covered. The low coverage could be augmented by including more

14 factors, but as discussed above, presenting more than ten factors are also challenging to interpret, apply in practice, and further research. Factor one has the highest initial eigenvalue (3.3) and explained variance (9.6%), which decreases for each factor. Factor two has an initial eigenvalue of 3.1 and explained variance of 9.1 %, factor three´s initial eigenvalue is 2.4, and explained variance 7.1%, followed by factor four´s initial eigenvalue of 2 and explained variance 6%.

Figure 1. The four factors, All-Group. 4.2.2 <21-group

In the group with the cases aged 21 and younger (n=219), the same extraction and rotation method was applied, Maximum Likelihood with Promax rotation. The total explained variance in this age group, 27.1%, is lower than in the All-group. The first factor has an equally high explained variance, 9.1%, and initial eigenvalue, 3.1, but the following factors have lower scores. The second factor´s initial eigenvalue is 2.5, and explained variance of 7.3%, the third factor´s initial eigenvalue is 1.9 and

explained variance 5.7%, and the fourth´s initial eigenvalue is 1.7 and explained variance of 5%. The eigenvalues are high and are no problem. The explained variance would preferably be higher.

15

Figure 2. The four factors, <21-Group. 4.2.3 >22-group

The third age-group, with those aged 22 and older (n=1021), are also extracted and rotated with the same configuration. The total explained variance of the four factors is only 24.5 %. In factor one, the explained variance is 7.7 %, in the second 6.6 %, the third 5.6 %, and in the fourth 4.6%. These low figures need to be analyzed if they were to be practically relevant. Three-quarters of the variance of the older age group is not represented in these results. In this age group, it would be relevant to discuss if more factors should be included or if other methods are preferable. The initial

eigenvalues are sufficient, in factor one 2,6, in the second factor 2.2, in the third 1.9 and in the fourth 1.6.

16

Figure 3. The four factors, >22-Group.

4.3 One Factor Model

The results of factor 1 for each age-group presented in figure 4. The diagram has extracted relevant/practically significant data from appendix 1 to 3. In appendix 1 to 3 is all the data available. The cluster of variables (factor), which explains the most variance in all the age-groups, is presented in a circle diagram (known as Factor 1). To be able to compare the different age-groups, all the values are included in the table chart, but remember that only values above .3 should be tolerated (Thompson 2004, Osborne 2014).

17

Figure 4. Factor 1 in all three groups.

Factor 1 in ALL-group has an explained variance of 9.6% and an eigenvalue of 3,3. The variables in factor 1 with a coefficient sum above 0.3 for the All-group includes which radicalized group the individual is a part of as well as that the radicalized individual is radicalized online, through social media or in an institution. The individual might have some mental illness, someone in the family might have been victimized or committed a crime, a friend is likely to be radicalized, and the

individual has much unstructured time.

The factor 1 in the <21-group shows a substantial factor sum for that the individual has been physically or verbally as a child, might have some mental illness, have experienced some trauma, and might be a member of a gang. Factor 1 has an explained variance of 9.1% with an initial eigenvalue of 3.1.

The factor 1 in the >22-group shows that the individual likely actively searched for the radicalized group, and it might be of importance which radicalized group the individual is a part of. The individual might have some alcohol or drug abuse, mental illness, a radicalized friend, and some unstructured time. Factor 1 has an explained variance of 7.7% with an initial eigenvalue of 2.6.

5.0 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

The exploratory factor analysis results are clusters of variables (factors) that explain the variance in the radicalized individuals’ characteristics. This essay aims to divide the population in regard to age instead of ideology for two reasons: 1. Since previous research is lacking empirical evidence and thence urge further research and 2. Since different authorities are responsible for the radicalized youths and adults and might require specific empirical evidence to their field. The responsible investigative authorities have integrated the risk factor approach in their line of work, and the risk factor approach is still considered to hold much potential as a theory (Borum 2011a;

18 Borum 2011b; Horgan 2008). By creating factors specific to different responsible authorities, the results can easily be interpreted, integrated, and further developed by practitioners.

5.1 What age-specific risk factors contribute to radicalization and make individuals susceptible to radicalized groups?

5.1.1 The ruling

The results imply a need for age-specific risk factors. Radicalized youths tend to have some potentially traumatizing experience with psychological vulnerabilities, while the adult population tends to have developed norm-breaking behavior. The results indicate that age-specific analysis generates more applicable, valid, and reliable results than the non-specific.

5.1.2 Justification

Examining the first factor, the factor which explains the most variance, there is a large difference between the different age groups. In the group of those who are aged 21 or younger, the experience of being abused as a child is a crucial and decisive component. The factor further included mental illness, traumatic experience, and gang membership. These four variables together explain 9.1 % of the total variance. In the adult group, aged 22 and older, there are different variables in the first factor compared to the younger group. The results show that individuals aged >22 years old have probably actively searched for the radicalized group, and it might be of

importance which radicalized group the individual is a part of. The individual might have some alcohol or drug abuse, mental illness, a radicalized friend, and some unstructured time. Factor 1 has an explained variance of 7.7%.

Different risk factors are essential for different purposes and in different parts of the radicalization process. The static risk factors and variable markers are events or circumstances that already have happened, such as how the individual was

radicalized, and which radicalized group the individual has joined, or variables that cannot be changed (Kraemer et al. 1997; Harris & Rice 2015). If the goal is to prevent radicalization, these factors might be of interest because it might be too late to influence the impact of these risk factors after the individual has been radicalized. The static risk factors and variable markers might also be the only information the investigative police and child protection agency has. If their goal is to de-radicalize the individual, their investigation should aim at the potentially dynamic and causal

risk factors. The analytical technique in this essay does not allow for a proper causal

explanation of risk factors (Osborne 2014), but the results could influence a hypothesis in such research. In the one-factor model, some variables could be impacted by treatment, such as if the individual has a considerable amount of unstructured time, radicalized friends, is a gang member, has a mental illness, or an alcohol or drug abuse. The results indicate that treatment focusing on psychological factors such as mental illness, alcohol or drug abuse, and the experience of potentially traumatizing events or social factors such as unstructured time, radicalized friends, or being a gang member hold much promise.

19 Previous research that does not specify risk factors according to age would present the All-group as their results (For example: Rostami et al. 2018; Carlsson 2015; Altier et al. 2014). The results of this essay imply issues with non-specific age results. The only concurrent variable in all the age-groups is mental illness. The >22-group additionally shares the variables group membership, radicalized friend, and

unstructured time. The results indicate that age-specific analysis generates more

applicable, valid, and reliable results than the non-specific. The younger population tend to have more often been abused as a child, had some traumatic experience and are currently part of a gang, while the older population tend to have alcohol or drug abuse problems and more unstructured time, have a radicalized friend and have actively searched for their radicalized group. If the only available research presents non-specific age results, the empirical evidence could be misleading when

constructing policies.

5.2 How do these results compare to our current understanding of radicalization in Sweden and age-specific risk factors?

5.2.1 The ruling

The results are consistent with recent age-specific research in western Europe. Research on radicalization in the Swedish context could benefit from age-specific analysis with a subtle definition of psychology.

5.2.2 Justification

Analyzing the <21-group, the risk factors which explain the most variance indicate a high psychological vulnerability. Risk factors as being abused, having a mental illness, or experiencing potentially traumatizing events have empirically robust evidence (Altier et al. 2014; Harpviken 2019; Campelo et al. 2018). The second factor indicates that youths often has actively searched for the radicalized groups online and on social media. When they plot a terror attack, they do it online as well. Their online communications and activity are also consistent with previous research (Campelo et al. 2018; Kaati 2018). The psychological vulnerabilities are not only present among the youths, in the >22-group is the results from the second factor indications of psychological vulnerabilities. Experiencing social stratum as a child, being abused as a child, having absent parents, and experiencing potentially

traumatizing events are examples of massive psychological vulnerabilities (Harpviken 2019). The first factor, which explains the most variance, is although different from the <21-group. Consistent with the comparative analysis by Oppetit (et al. 2019), the older age group is more often radicalized in their physical environment with radicalized friends. The results of this essay also indicate alcohol or drug abuse, much unstructured time, and mental illness. Previous research implies that perceiving discrimination is one of the most influential risk factors for radicalization (Campelo et al. 2018; Harpviken 2019; Borum 2004; Oppetit 2019). There is no variable in the PIRUS-dataset which measure if the individual has perceived any form of

discrimination which previous research has found to one of the most decisive risk factors. Future research should include if the individual has perceived discrimination.

20 Comparing the results with current Swedish research is challenging. Swedish

researchers do not specify their analysis by age. Rostami et al. (2018) argue in the conclusion from the extensive research project that it was unexpected that 80 % of the radicalized individuals were not identified in their youth. One reason why Rostami et al. (2018) does not find any empirical understanding of why the responsible

authorities do not identify youths might be because they do not do any age-specific analysis. In accordance with Rostami et al. (2018), the results in this essay from the All-group are also problematic. Since different authorities are responsible for radicalized youths and radicalized adults, there is a need for age-specific empirical evidence. If the responsible authority for radicalized youths built their policies on risk factors from the All-group, they would miss much of the explained variance. This essay's results indicate that psychological vulnerabilities make youths susceptible to radicalization and that alcohol/drug abuse, unstructured time, and radicalized friends are the most relevant risk factors among adults. Policies based on the results from the All-group constitute that the individuals radicalize online, as youths do, but with the risk factors of unstructured time and radicalized friends, which is more present among the adults. Despite that, SOU 2017:67, does not highlight a need for age-specific analysis, the results from this essay indicate that age-age-specific research could increase the understanding of radicalization. A combination of psychological

vulnerabilities and age-specific analysis could improve the capacity of the responsible authorities. Rostami et al. (2018) attempted to explain why only 20 % of the

radicalized youths were identified with psychiatric diagnoses and found ambiguous empirical evidence. The result from this essay implies, with consistency with Campelo et al. 2018, Harpviken 2019, Borum 2004, Oppetit 2019, that it is not psychiatric diagnoses that are relevant, but the more subtle area of psychology. 5.3 Victim offender overlap

In the PIRUS-dataset (2020) are variables of both offending and victimization included. Variables regarding offending include criminal severity, violent plot and

previous criminal activity, and variables regarding if the individual had been

victimized include if the individual has been abused as a child, traumatic experience,

and criminality in the family. Previous research concludes that variables such as

victimization and psychological vulnerability are correlating with radicalization (Altier et al. 2014; Campelo et al. 2018; Harpviken 2019; Oppetit et al. 2019) and those variables are frequently occurring from analyzing the results of this essay. Even if the radicalization process is a complex development, the first mechanism seems to be some kind of adverse event as a turning point (McGilloway 2015; Rostami et al. 2018; The Council of the European Union 2018). Every event is unique, and everyone reacts differently to similar types of events, meaning that it is difficult to predict who will radicalize. Further problematizing our understanding studies have shown that there is a victim-offender overlap, which means that the offender profile often shares many characteristics with the victim profile (Daigle 2013; Mulford et al. 2018). The offender is often also a victim of other offenses. It is essential to

acknowledge that the radicalized individual is a threat to our democratic society at the same time as he or she probably has been victimized and suffers from psychological vulnerabilities.

21 5.4 What implications could the results have for the responsible

investigative authorities?

5.4.1 The ruling

The results indicate disparate risk factors depending on age and since different authorities are responsible for investigating youths and adults, they should consider evaluating current policies.

5.4.2 Justification

The official intention in Sweden is to “prevent, avert and obstruct” acts of terror (Skr. 2014/15:146). One part of prevention is to identify youths in the radicalization

process as early as possible and de-radicalize them. Therefore, it is a critical problem that the responsible authorities only identified 20 % of the radicalized population in Sweden in their youth (Rostami et al. 2018). This essay did an age-specific analysis and found different clusters of risk factors for youths and adults (Oppetit et al. 2019). Furthermore, the results of the All-group indicate that policies based on non-specific data are misleading.

This essay has studied the effects of analyzing radicalization depending on age instead of ideology in a Swedish context. The dataset is although American (PIRUS). There is no public dataset available in Sweden, but Swedish researchers have access to the necessary information (Rostami et al. 2018). The results of this essay are an argument for the necessity of age-specific analysis and the inclusion of subtle psychological vulnerabilities.

Since there is empirical support for age-specific risk factors (Campelo et al. 2018; Harpviken 2019; Oppetit et al. 2019), this essay also indicates that responsible authorities should investigate the empirical support for their current policies and update them if necessary. Age-specific risk factors could, for example, improve how the Swedish child protection agency identifies youths in the risk of radicalization, understand their situation and better help them. The present ruling policies of, for example, the child protection agency could benefit from understanding the risk of child abuse and understanding that the radicalized youths might have been victimized before.

Risk factors should though not be considered as predeterministic. The significance of each particular kind of risk factor will vary for each individual (Borum 2014). The genuine significance of any cluster of risk factors must be considered with caution, particularly in the absence of any acknowledgment of the supposed positive factors. 5.5 Limitations

This essay is a vital addition to what is currently known and researched regarding radicalization, especially in a Swedish context. This essay raises a discussion about if radicalization should be divided depending on ideology, which we know have more commonalities than differences, or according to age, which provides data that can be implemented directly by the responsible authorities. With that in mind, this essay

22 would greatly benefit from a dataset with information on the Swedish context.

Performing the same kind of analysis with a dataset with official data and fewer missing cases would significantly improve validity and reliability. Even though the essay suffers from the limitations of missing cases and uncertainties in the data collection method, the results are consistent with recent similar research. By viewing this essay together with similar research, the validity increases, and certain

conclusions can be made.

6.0 CONCLUSION

Radicalization has become a prioritized issue across the world, both academically and in the society in general. In the last decade, the radicalization process, terror attacks, radicalized individuals, and group formation have developed, leading to an increasing urgency, at least in Sweden, to develop new strategies to "prevent, avert and obstruct" acts of terror. In this new paradigm, old theories of creating profiles for terrorists have been replaced with research aiming to find risk factors for radicalization. This essay unites with newly published research moving from ideologically driven categorization to age-specific analysis. Previous research has already submitted empirical support for commonalities among ideology-driven radical groups and individuals. The specific analysis provides a deepened understanding of age-specific risk factors that contribute to radicalization and make individuals susceptible to radicalized groups. The results of this essay are consistent with similar current age-specific research in western Europe and could complement Swedish research. This essay should be reproduced, but with a better dataset with official data from Sweden or other Nordic countries. Since different investigative authorities are responsible for youths and adults and already work with a risk factor approach, the findings in this essay proclaim that the authorities should evaluate their current policies and potentially update them to age-specific risk factors if necessary.

23

7.0 REFERENCES

Ali, M. R. B., Moss, S. A., Barrelle, K., & Lentini, P.. (2017). Does the Pursuit of Meaning Explain the Initiation, Escalation, and Disengagement of Violent

Extremism? Aggression and Violent Behavior, 34, 185–192

Altier, M. B., Thoroughgood, C. N., & Horgan, J. G.. (2014). Turning Away from Terrorism Lessons from Psychology, Sociology, and Criminology. Journal of Peace

Research 51 (5): 647–61.

Borum, R.. (2011a). Radicalization into Violent Extremism I: A Review of Social Science Theories. Journal of Strategic Security. 4. 7-36

Borum, R.. (2011b). Radicalization into violent extremism II: A review of conceptual models and empirical research. Journal of Strategic Security, 4(4), 37–62.

Borum, R.. (2014). Psychological vulnerabilities and propensities for involvement in violent extremism: “Mindset”, worldview and involvement in violent extremism.

Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 32(3), 286–305.

Bouzar, D.. (2018). The stages of the radical process report. Partnership against violent radicalization in cities.

Campelo, N., Oppetit, A., Neau, F., Cohen, D., & Bronsard, G.. (2018). Who are the European youths willing to engage in radicalisation? A multidisciplinary review of their psychological and social profiles. European Psychiatry, 52, 1-14.

Carlsson, C.. (2016). Att lämna våldsbejakande extremism: En kunskapsöversikt. Stockholm: Institutet för Framtidsstudier

The Council of the European Union (2018). Radicalisation, Recruitment and the EU

Counter-radicalisation Strategy. The European Commission

Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. W.. (2005). Exploratory Factor Analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment,

Research, and Evaluation, 10(7), 1-9.

Daigle L. H. (2013). Victimology. The essentials. London ; Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

Douglass, R. W., & Rondeaux, C. (2017). Mining the Gaps: A Text Mining-Based

Meta-Analysis of the Current State of Research on Violent Extremism. Washington

D.C.: United States Institute of Peace (USIP).

European Union (2019). Terrorism Situation and Trend Report. European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation.

24 Global Terrorism Index (2019). Measuring the Impact of Terrorism. Institute for Economics & Peace. Sydney, November 2019

Gold, M. S., & Bentler, P. M.. (2000). Treatments of Missing Data: A Monte Carlo Comparison of RBHDI, Iterative Stochastic Regression Imputation, and Expectation-Maximization. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 7(3), 319-355.

Graham, J. W.. (2009). Missing Data Analysis: Making It Work in the Real World.

Annual Review of Psychology, 60(1), 549-576.

Harris, G. T., & Rice, M. E.. (2015). Progress in violence risk assessment and communication: Hypothesis versus evidence. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 33, 128–145.

Harpviken, A. N.. (2019). Psychological Vulnerabilities and Extremism Among Western Youth: A Literature Review. Adolescent Research Review, 1-26. Hirschi, T, Gottfredson, M (1983). Age and the explanation of crime. American

Journal of Sociology 89(3): 552–584

Horgan, J. G.. (2004). The Social and Psychological Characteristics of Terrorism and Terrorists. In: Bjørgo, T.. (Ed.), Root Causes of Terrorism: Myths, Reality and Ways

Forward (pp. 44–54). New York: Routledge.

Horgan, J. G.. (2008). From Profiles to Pathways and Roots to Routes: Perspectives from Psychology on Radicalization into Terrorism. Annals of The American Academy

of Political and Social Science 618. 80-94.

Horgan, J. G.. (2009). Walking away from terrorism: accounts of disengagement from

radical and extremist movements. London: Routledge

Jasko, K., LaFree, G., & Kruglanski, A.. (2017). Quest for significance and violent extremism: The case of domestic radicalization. Political Psychology, 38(5), 815– 31.

Jensen, M. A., Seate, A. A., & James, P. A.. (2018). Radicalization to Violence: A Pathway Approach to Studying Extremism. Terrorism and Political Violence, 1-24. Kaati, L.. (2019). Digitalt slagfält: en studie av radikalnationalistiska digitala

miljöer. Stockholm: Totalförsvarets forskningsinstitut (FOI)

Kumar, R.. (2014). Research Methodology: A Step-by-Step Guide for Beginners (Google eBook) 4th Ed., London: SAGE.

25 Kraemer, H.C., Kazdin, A.E., Offord, D.R., Kessler, R., Jensen, P. & Kupfer, D.J.. (1997). Coming to term with the terms of risk. Archives of general psychiatry. 54. 337-43.

Ku2016/02295/D (2016). Uppdrag till Socialstyrelsen att fortsatt stödja

socialtjänstens arbete mot våldsbejakande extremism. Regeringskansliet:

Kulturdepartementet

Ku2016/02294/D (2016). Uppdrag till Barnombudsmannen att öka kunskapen om

barns upplevelser av våldsbejakande extremism och terrorism. Regeringskansliet:

Kulturdepartementet

Ku2016/02296/D (2016). Uppdrag till Statens institutionsstyrelse att utveckla det

förebyggande arbetet mot våldsbejakande extremism. Regeringskansliet:

Kulturdepartementet

LaFree, G., Jensen, M. A., James, P. A., & Safer-Lichtenstein, A.. (2018). Correlates

of Violent Political Extremism in the United States. Criminology,

Lööw, H.. (2017). Våldsbejakande extremism - begrepp och diskurs. in: SOU 2017:67 C. Edling & A. Rostami (red.), Våldsbejakande extremism: En

forskarantologi. Stockholm: Regeringskansliet

McGilloway A., Ghosh P. & Bhui K.. (2015). A systematic review of pathways to and processes associated with radicalization and extremism amongst Muslims in Western societies. Int Rev Psychiatry 27:39–50.

Mulford, C.F., Blachman-Demner, D.R., Pitzer L., Schubert, C.A., Piquero, A.R. & Mulvey E.P.. (2018). Victim Offender Overlap: Dual Trajectory Examination of Victimization and Offending Among Young Felony Offenders Over Seven Years.

Victims & Offenders, 13:1, 1-27

National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), University of Maryland. (2020). Profiles of Individual Radicalization in

the United States (PIRUS) [Data file]. Retrieved from

http://www.start.umd.edu/data-tools/profiles-individual-radicalization-united-states-pirus

O'Connor, B. P.. (2000). SPSS and SAS programs for determining the number of components using parallel analysis and Velicer's MAP test. Behavior Research

Methods, Instrumentation, and Computers, 32, 396-402.

Oppetit, A., Campelo, N., Bouzar, L., Pellerin, H., Hefez, S., Bronsard, G., Bouzar, D. & Cohen, D.. (2019). Do Radicalized Minors Have Different Social and

26 Osborne, J. W.. (2013). Best Practices in Data Cleaning: A Complete Guide to

Everything You Need to Do Before and After Collecting Your Data. Thousand Oaks,

CA: Sage Publications.

Osborne, J. W.. (2014). Best Practices in Exploratory Factor Analysis. Createspace Independent Publishing Platform

Pisoui, D., & Reem, A.. (2016). Radicalisation Research – Gap Analysis. RAN centre of excellence

Rostami, A., Mondani, H., Carlsson, C., Sturup, J., Sarnecki, J. & Edling, C.. (2018).

Våldsbejakande extremism och organiserad brottslighet i Sverige. Stockholm:

Institutet för framtidsstudier

Russell, D.. (2002). In Search of Underlying Dimensions: The Use (and Abuse) of Factor Analysis in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. Personality and

Social Psychology Bulletin. 28. 1629-1646.

Sturup, J., & Långström, N.. (2017). Individuella riskfaktorer och riskbedömningar för våldsbejakande radikalisering: en översikt av forskningsläge och metoder. In: SOU 2017:67 C. Edling & A. Rostami (red.), Våldsbejakande extremism: En

forskarantologi. Stockholm: Regeringskansliet

Säkerhetspolisen (2018). Säkerhetspolisens årsbok för 2018. Stockholm: Säkerhetspolisen

Säkerhetspolisen (2019) Långsiktigt hot mot demokratin. Available:

https://www.sakerhetspolisen.se/ovrigt/pressrum/aktuellt/aktuellt/2019-03-14-langsiktigt-hot-mot-demokratin.html

SOU 2017:67. Edling, C. & Rostami, A.. (red.), (2017). Våldsbejakande extremism.

En forskarantologi. Stockholm: Regeringskansliet

SOU 2019:49. (2019). En ny terroristbrottslag. Stockholm: Norstedts juridik Skr. 2014/15:146. (2014). Förebygga Förhindra Försvåra: Den svenska strategin

mot terrorism Regeringens skrivelse 2014/15:146

The Council of the European Union (2018) Radicalisation, Recruitment and the EU

Counter-radicalisation Strategy. The European Commission

Thompson, B. (2004). Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis: Understanding

concepts and applications. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association

Unkel, S., and Trendafilov, N.T.. (2010) Simultaneous parameter estimation in exploratory factor analysis: an expository review. Int. Stat. Rev. 78, 363–382

27 2019/20:JuU19 (2019) Hemlig dataavlyssning. Riksdagen: Justitieutskottet

28

8.0 APPENDIX

Appendix 1. Four factor model of All-group.

Four factor matrix in All-group a

Rotated pattern matrix

Rotated structure matrix Factor 1 Factor 2 Facto r 3 Facto r 4 Facto r 1 Facto r 2 Facto r 3 Facto r 4 Violent Plot -,127 -,138 ,363 ,018 -,079 -,080 ,319 -,067 Internet part of plot -,032 ,094 -,222 ,551 -,052 ,040 -,344 ,601

Criminal Severity -,162 ,101 -,031 -,242 -,171 ,104 ,023 -,241 Group Membership ,586 ,036 -,159 ,055 ,566 ,006 -,090 ,102 Actively Recruited -,011 ,013 -,055 -,278 -,023 ,014 ,013 -,265 Actively Searching ,319 ,132 -,338 ,349 ,280 ,065 -,360 ,432 Role in Group -,030 ,051 -,008 -,166 -,034 ,055 ,036 -,167 Online Radicalization -,432 -,040 -,018 ,603 -,424 -,061 -,227 ,601 Media Radicalization ,157 ,073 ,086 ,248 ,172 ,078 ,059 ,227 Social Media Radicalization -,496 -,067 -,045 ,600 -,492 -,092 -,266 ,605 Duration of Radicalization ,127 -,033 ,008 -,201 ,125 -,026 ,068 -,200 Radical Ideology ,239 ,073 -,029 ,026 ,235 ,066 ,007 ,035

29 Radicalization Sequence ,003 ,038 ,070 ,181 ,015 ,044 ,033 ,163 Radicalization in Institution ,385 -,038 -,263 -,100 ,349 -,079 -,194 -,029 Ethnicity ,073 -,075 -,223 ,139 ,047 -,116 -,259 ,197 Gender ,002 ,089 -,091 -,027 -,010 ,075 -,070 -,008 Religious Background -,326 ,008 ,399 -,251 -,279 ,082 ,419 -,354 Immigrant Generation ,142 -,007 -,423 ,308 ,092 -,086 -,480 ,412 Education level ,186 -,206 -,137 -,098 ,167 -,226 -,122 -,055 Employment Status -,186 ,017 ,018 ,056 -,183 ,019 -,017 ,048 Social Stratum Childhood -,004 -,450 -,037 -,022 -,008 -,455 -,105 ,001 Abused as Child -,048 ,557 -,142 -,012 -,069 ,535 -,056 ,003 Mental Illness -,376 ,340 -,133 -,141 -,397 ,324 -,093 -,127 Alcohol/Drug Abuse -,266 ,206 -,012 -,070 -,270 ,207 ,004 -,078 Absent Parents -,022 ,605 ,099 -,031 -,012 ,622 ,202 -,075 Criminality Family ,310 ,152 ,897 ,294 ,431 ,286 ,891 ,077 Radicalized Friend ,554 -,027 ,206 ,057 ,582 ,002 ,261 ,017 Radicalized Family ,166 -,104 ,330 ,091 ,211 -,054 ,313 ,018 Unstructured Time -,430 ,193 ,123 ,044 -,414 ,214 ,087 ,001

30 Expelled -,126 ,379 ,025 ,046 -,124 ,382 ,059 ,025 Previous Criminal Activity -,165 ,253 ,305 -,095 -,128 ,306 ,347 -,180 Gang Member ,010 ,087 ,068 -,033 ,018 ,099 ,091 -,052 Traumatic Experience ,169 ,686 -,204 ,007 ,140 ,652 -,073 ,036 Loss of Social Standing -,180 ,297 ,022 ,060 -,177 ,299 ,032 ,041

aExtraction Method: Maximum Likelihood. Rotation Method: Promax with Kaiser Normalization. Rotation converged in 7 iterations. Total explained variance 31,8 %

b Initial eigenvalue 3,3. Explained variance 9,6%. c Initial eigenvalue 3,1. Explained variance 9,1%. d Initial eigenvalue 2,4. Explained variance 7,1%. e Initial eigenvalue 2,0. Explained variance 6,0%.