China in Africa: A Study of Chinese Leadership in the

Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC)

Greta Simonaviciute

International Relations

Dept. of Global Political Studies Bachelor programme – IR 61-69, IR103L 15 credits thesis

Spring 2020, Date of Submission: 14/5/2020 Supervisor: John H. S. Åberg

Abstract

The leadership of powerful states in processes of institutional bargaining is significant, though still widely ignored subject in the field of International Relations (IR). Particularly, China’s active involvement and, in fact, leadership in the regime formation has drawn wide attention from scholars and policy analysts alike. The discussion to follow, therefore, focuses on the leadership role of China in the international regime process. This study uses a qualitative content analysis method in theory-driven case study research. The suggested Oran Young’s leadership theory which includes such basic factors as structural power, practice of the negotiations skills and ability to generate ideas, is aimed at analyzing the complex leadership potential of China in the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) process. Additionally, the study utilizes desktop research and therefore secondary sources, including numerical data to support this study. The findings demonstrate that China’s leadership role in the FOCAC process is influential and effective. Chinese practice of structural power, negotiation skills and knowledge leadership through the FOCAC corresponds well with its foreign policy strategy. Finally, Chinese policies in the FOCAC process show high flexibility when it comes to the complexity of China-Africa relations and China’s ability to adapt to the new circumstances.

Table of Content

CHAPTER 1

1. Introduction

1.1 Research Aim and Research Question……….2

1.2 Disposition of the Study………...3

CHAPTER 2

2. Literature Review

2.1 Emerging Powers and Political Leadership in International Relations…………42.1.1 Emerging Powers in International Relations………4

2.2.1 Political Leadership in International Relations………5

2.2 Grasping China’s Foreign Policy Strategies and its Global Impacts…………...6

2.3 FOCAC and the Quest for Leadership in Africa………..9

CHAPTER 3

3. Theory

3.1 Theoretical Approach to the Study of Leadership……….123.2 Relevance of the Leadership Theory……….14

CHAPTER 4

4. Research Method for Studying Leadership Role of China

4.1 Approach to the Research………..164.2 Data Sources and Collection of Data……….18

4.3 Validity and Reliability of the Method………..20

4.4 Limitations of the Method……….20

CHAPTER 5

5. Findings and Analytical Discussions

5.1 Structural Leadership: Practise of Bargaining Leverage………...235.2 Entrepreneurial Leadership: Practices of Negotiation Skills……….30

5.3 Intellectual Leadership: Practise of Intellectual Innovations……….34

5.3.1 Equality, Mutual Benefit, Mutual Respect and “All-Weather Friend” ……...35

5.3.2 Sovereignty, Territorial Integrity and Non-Interference……….38

5.3.3 Harmonious Coexistence and Mutual Non-Aggression………41

CHAPTER 6

6.Conclusion

………43Appendices

………....451

China in Africa: A Study of Chinese Leadership in the

Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC)

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

In the past few years, there has been an increasing number of academic interests in emerging powers’ significance to the international order in correlation to their power, strategies and evolving new roles. In particular, China’s increasing interest, participation and, in fact, leadership in multilateral organisations, which has been a hallmark of its shift in foreign policy since the 1990s (Jakobowski, 2018:659). China’s agenda has drawn wide attention and even controversy on its future ambitions and the nature of China’s global leadership (Wang, 2005). These active involvements in multilateralism symbolize the phenomenal shift in China’s foreign policy by breaking away from its tradition of bilateral diplomacy.

China’s journey to regional leadership in African continent may be observed since the establishment of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in 2000, under the period of President Jiang Zemin (Contessi, 2009:412). The forum brings together China and 53 out of 54 African countries that have established diplomatic relations with China (appx. 2). The Chinese involvement and its role in multilateral diplomacy are clearly seen in FOCAC. China’s foreign policy interests in Africa have been met with both criticism and praise from academic and policy analysts alike, across the globe. China has often been accused of luring African countries in its debt-trap by providing them loans and then control them when they fail to pay off their debts (Brautigam, 2009:12). While others argue that the forum is mutually beneficial cooperation model (Anshan et al, 2012:9).

The thesis focuses on China’s emerging practise of leadership in the multilateralism process within the field of international relations (IR). This research is a systematic and in-depth study on the leadership role of China with a special focus on the FOCAC process as an empirical point of departure. Particularly, it highlights how the role of a leader is conceived and performed. Moreover, this thesis applies Oran Young’s (1991) leadership theory of intellectual, entrepreneurial and structural leadership emphasizing the particular practise that

2 China has adopted in the process of institutional bargaining, including its use of structural power, negotiating skills and the generation of ideas governing international regimes.

As the literature review will show, some scholars applied a concept of leadership to analyse the role of emerging and regional powers (Dent, 2008; Flemes and Wojczewski, 2011). However, in any case of collective action, political leadership in international institution-building remains a topic that is less well understood (Young 1991; Underdal 1994; Tallberg 2006; Deese, 2007; Morton 2017). Most of the existing research that is conducted about political leadership has its focus on domestic politics or general governmental organisations, rather than international organisations and diplomacy (Wang, 2005:50).

For instance, traditionally, IR theories such as rationalism focuses on multilateralism from the perspective of structural and power-based quality of leadership, while constructivists and poststructuralists have only recently started to approach concepts such as discursive hegemonic strategies and the leading integrating role of power in its region (Nabers, 2008). This phenomenon is thus important to examine to enrich study on leadership in IR, particularly on the regional leadership issue. The following section outlines the purpose, research question, followed by the structure of the paper of this research.

1.1

Research Aim and Research Question

The leadership of powerful states in processes of institutional bargaining is significant, though still widely ignored topic in the field of IR (Young, 1991). The thesis, therefore, seeks to contribute to a broader conversation and debate in the political as well as in the academic circles on the issues surrounding the concept of leadership in the context of institutional bargaining.

It needs to be noted that this study is aware of China’s several failures when it comes to involvement in Africa. These include contradictions in China’s principles of non-interference, mutual benefit or human rights discourse and others. Cases of supporting weak regimes and dictatorships in Zimbabwe, arming revolutionary rebellious in South-West Africa, Congo and Alegria, and cooperation with a Sudanese regime that does not consider human rights come under wide criticism (Strauss, 2009:783; Fernando, 2014:152). However, the purpose of this study is not to detail the ways in which China’s actions differ from those principles. As Strauss (2009:778) noted, “post-Westphalian states all exhibit significant gaps between what they say and what they do”. Keeping this in mind, this research aims to examine the leadership role of China in-depth with a special focus on its grounding and framing

3 principles of Chinese policies towards and actions in Africa.

Particularly, by examining how China bridges political and ideological cleavages within the framework of FOCAC and how China tries to guide the states of the African region towards the ‘shared goal’, this study contributes to the evolving debate in international politics on the rise of China on the world stage in general and on the African continent in particular. In addition, the significance of the study is to complement already existing literature and deepen understanding of the impact of China’s emerging power, same as its negotiations of regime formation in FOCAC, thereby providing additional literature that could be used in contrast to other countries, same as to the wider public in general. Finally, theoretically, this study also aims to contribute to the testing of international political leadership theory, in part to encourage its application to the analysis of other regimes as in this case- China’s leadership role in FOCAC process.

With that in mind, the research question which is to be answered in the line of this study is the following: How is China performing a leadership role in FOCAC? To answer this question, the study will assess the qualitative content analysis as a text interpretation method in the theory-driven case study research. Additionally, this study argues that structural power asymmetry does not necessarily condition the absolute political leadership in the international regime process.

1.2 Disposition of the Study

The thesis is structured as follows: Chapter 1 provides an overview of the research topic and its relevance, including the problem, purpose and research question of the thesis. Chapter 2 conceptualizes and examines numerous existing literatures on the chosen three themes. The themes are (i) emerging powers and political leadership in international relations, (ii) grasping China’s foreign policy strategies and global impact, and (iii) FOCAC and the quest for leadership in Africa. Chapter 3 reviews the theoretical framework grappling this ongoing debate, respectively. Chapter 4 presents a method used for the research. Chapter 5 constitutes the analytical section for the research which focuses on China’s abilities to lead in Africa based on a theory-driven case study. Chapter 6 concludes the outcomes of the research.

4

CHAPTER 2

Literature Review

This chapter aims to review previous research, ideas and approaches that are relevant to the research topic. The literature review is organised into three themes that are related to the research question. (1) Emerging powers and leadership in international relations; (2) grasping China’s foreign policy strategies and its global impact; and (3) FOCAC and the quest for leadership in Africa. These themes are relevant to ideas and interpretations of the previous research. Understanding of the previous research is necessary to understand the framework of the thesis.

2.1 Emerging Powers and Political Leadership in International Relations

China might be considered an emerging power, regional power or even a potential global leader (Alves and Alden, 2017). The theoretical understandings behind these concepts are broadly contested in IR. Therefore, this section clarifies them by presenting previous research on these concepts. This section is divided into two parts: (1) presents the concepts of emerging powers and regional powers. (2) introduces several concepts of leadership within IR.

2.1.1 Emerging Powers in International Relations

Emerging power and regional power are contested concepts in IR. Hurrell et al. (2000:1) describe that they are challenging to define. In addition, it is quite difficult to differentiate between the concepts of regional and emerging power (Nolte, 2010:890).

Jordaan (2003:165) describes emerging powers as “states that are neither great nor small in terms of international power, capacity, and influence”. This suggests that emerging powers are countries with capabilities below those of great powers, but still far above most secondary states. Additionally, Keohane (1969) arranges the states as to the degree of their influence in international affairs. He refers to emerging power as “a state whose leaders consider that it cannot act alone effectively but may be able to have a systematic impact in a small group or through the international institution” (1969:295). Malamud (2011:3) interprets Keohane’s reference to a “small group” as an emerging power’ strategy to enter the international system. Also, he refers to the “international institution” as their strategy’s preference. Keeping this in mind, international institutions, for emerging countries are helpful platforms to exercise their power (Hurrell et al, 2000:6). Nolte (2010) affirms that the

5

formation of a regional regime is the most effective strategy for global leadership. Traditionally, states that are listed as regional powers are defined as powerful states which are highly influential in regional affairs. Hence, Nolte (2010:889) notes that regional powers have the capacity and ability to lead their neighbours. Other scholars, such as Kennedy (1987), and Buzan and Waever (2003), conceptualise regional powers on the basis of structural conditions. Such power is usually maintained through the possession of natural resources. Natural resources can be used in order to get exceed ideas and assure the behaviour of partners in a specific region (Nolte, 2010:892). Such possessions, in this view, is an essential element to become a regional power.

Concepts of the emerging and regional power are similar, and therefore it is quite difficult to distinguish between them. Nolte (2010:890) stresses that the difference between a regional and an emerging power rests on leadership, which means its power resources, self-conception, and leadership. Additionally, Fonseca et al (2016:49) note that the difference between both concepts rests on leadership. This means the ability to dispute the polarity or even create hegemony in a particular region. Regional leadership, “refers to political influence in diplomatic forums, which could be exercised by emerging powers” (Nolte,2010:890). Changes in the structure of an actor's capabilities in the distribution and accumulation of global wealth are accepted as the fundamental elements in the rise as an emerging power. On the other hand, emerging power is the ability to create more favourable political decisions in multilateral spheres. Emerging power is, thus, a country that observes such aspects and is able to convert it into political power.

2.1.2 Political Leadership in International Relations

The definition of political leadership is highly contested in IR. Yet, it is an essential element of all spheres of politics, particularly, in understanding success or failure in the processes of institutional bargaining (Young, 1991; Nabers, 2008). Most of the studies on leadership exist in the domestic, rather than on the international arena of leadership (Malnes, 1995; Underdal 1994; Deese 2007).

Previous research on leadership and its importance for the regime formation was, primarily viewed through the realist approach in the notion of hegemony. Keohane (1969:136) stressed that hegemony played a crucial role in the regime establishment and its sustainability. Hence, Snidal (1985:136) organized hegemony into coercive hegemony which referred to control achieved through material power, while benevolent hegemony was applied to a group

6

of great powers to provide public goods for the regime. Later, the liberal approach started to view hegemony as the relationship between power and leadership questioning on whether the power leads to leadership within the institution (Harrison, 2004:4).

On the other hand, the second generation of political leadership researchers argues that political leadership in an international context is not only about power and dominance. Rather, it is a triangular process which involves leaders, followers, and contexts (Masciulli et al, 2009:5). Additionally, Deese (2007:25) stresses that although a leader seeks to achieve a common goal in addition to her/his own policy agenda (act selfishly), in the process of goal-seeking, self-interest must recognise the interplay between morality and power (Deese, 2007:25). Thus, Burns (1979:18) states that potential leaders must be responsive to the values and interests of current or future followers. Nye (2008:32) conceptualizes “soft power”, which refers to the ability to achieve goals through attraction rather than coercion or payment. To such a degree, Higgott (2007:95) affirms that “leadership is not the same as economic and military preponderance. Leadership can be intellectual and inspirational as well”. Leadership, in these views, requires more persuasion rather than payment, threat or any kind of use of force. In short, simply forcing others to obey does not secure a leadership position.

Academics identified two methods of exercising leadership. Ikenberry and Kupchan (1990) describe the use of material encouragements in two ways: in a negative way such as sanctions or military strikes, and in a positive way such as rewards. The second method is when one state actor tries to modify the basic beliefs of another state actor by using dialogue, lobbying and other forms of diplomacy (Ikenberry and Kupchan, 1990:285). Nabers (2012:5) argues that political leaders often treat these approaches as complementary “political leaders may readily assume that economic and military incentives are necessary to modify the beliefs of leaders in other nations”. On the other hand, Nolte (2010) notes that cooperation rather than punishment is more stable and longer lasting. In addition, Nolte (2010) also argues that it guarantees access to resources within the region, while the process enables regional leaders to diffuse their political ideas, shaping the behaviour of other states.

2.2 Grasping China’s Foreign Policy Strategies and Global Impact

Since the early 1990s, the Chinese major foreign policy goal has been to achieve international recognition and expand internationally (Kent, 2013:138). According to Chinese leaders’ the new policies, particularly, aimed to make China rich, strong, democratic and civilised (Austin, 2013:70). Indeed, the extent of China’s shift in policy demonstrates

7 president Jiang Zemin’s speech at the Royal Banquet in the United Kingdom in 1999 where he with confidence spoke about China’s new readiness to view the UK, historically perceived as one of its oppressors, as one of its partners in international responsibility (Kent, 2013:134). Later on, President Xi Jinping’s gave a statement at the World Economic Forum in Davos in 2017 reaffirmed Chinese readiness to “play the role of the leader” on a global scale (Mikheev et al. 2017:2). This demonstrates changes in China’s relations between domestic politics and external behaviour, resulting in Chinese active participation and promotion of this national interests.

The main global tool for promoting and exercising China’s leadership role became the involvement in regional organisations carried mainly in the developing world (Alden et.al, 2017; Jakobowski, 2018:660; Farooq et al, 2019). Typical examples of this are seen in the establishment of the Middle East (China-Arab States Forum), Latin America and the Caribbean (China-CELAC Forum or CCF) and Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) that have created in recent years. Goldstein (2001) argues that multilateralism became a key element in the “diplomatic face of China’s grand strategy”. Contessi (2009:405) affirms that “it has been identified as the instrument to steer a strategy for transcend[ing] the traditional ways for great powers to emerge”. Multilateralism, in this view, became a Chinese alternative strategy to achieve global power.

Contrary to popular perception, contemporary China’s role with multilateralism is unlike its previous experience. Recent scholarship on China’s multilateralism seems to corroborate this proposition by exemplifying previous China’s alliance with other emerging economies, primarily the BRICS, where it united with equal partners and was somehow balanced by other major international actors (Yu, 2017:360; Jakóbowski, 2018:659). In Contrast, contemporary China is motivated to reshape the world order rather than be shaped by the changing world. Hence, Contessi (2009:406) affirms that “China has gradually shifted its role from that of norm taker, moved by mere compliance, to that of norm broker, becoming a fully-fledged entrepreneur”.

Since the 1990s, China has participated and initiated various regional arrangements which are signalling their importance within the international system, while at the same time challenging Western dominance and creating alternatives for the developing countries. Moreover, the new policy of opening helped China, in little more than three decades, transformed itself from a closed-off Asian nation trapped in poverty to an emerging global political and economic force (Garver, 2016:1; Alden and Alves, 2017:154). Thus, Nolte

8 (2010:881) affirms that China will sooner or later outperform the United States as the largest economy in the world.

Reflecting this unique role, China adopts several tactics and strategies in international organisations. Thus, Alden and Alves (2017:155) note that the change in Chinese foreign policy is “tactical and pragmatic” since it responds to the changing circumstances. A Chinese politician Tian Jiyun in 2001 stressed that “in international relations, China adheres to non-alignment and does not engage in the formation of military blocs, arms race and military expansion. China upholds an independent foreign policy of peace and a defensive national defence policy” (Kent, 2013:137). This tactic allows China to navigate “according to circumstance or need, towards either the developing or the developed world” (Kent, 2013:137). On the other hand, Glaser and Madeiros (2012) argues that China’s strategic goals remain essentially unchanged when it comes to regional and international order. Hence, Segal (1999) questions whether China’s power matters at all.

Some academics have stressed the importance of moral principles in China's international organisational behaviour (Kim, 1992; Shih, 1993). Chinese multilateral forums, unlike North-South cooperation, have a very distinctive nature. First, Chinese-backed norms are rooted in the ‘Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence’. These include mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, mutual non-aggression, non-interference in each other's internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence (White Paper, 2007). Second, these forums include high-level visits and different agenda-setting structure, new sectoral cooperation mechanisms and financial instruments (Jakobowski, 2018:660). China’s cooperation, in this view, is designed to benefit all members equally.

Keeping this in mind, China stresses the division between developed and developing countries (Strauss, 2009). In particular, the continuous Western influence on the international system (Fernando, 2014:156). Shih (1993) notes that through the involvement in multilateral organisations, China strongly promotes self-reliance rather than self-alliance with the recipient countries, highlighting the negative dependence on them. Thus, Kent (2013:140) affirms that China’s active participation in international organisations is not only about system-maintaining but also has affected “a partial return to a system-reforming approach, which in its view redresses the imbalances and injustices of the past”. This suggests that multilateral platforms have become China’s tool to reform such an agenda.

It is important to note here that although this paper reference China, in several occasions, as ‘initiator’ of creating the multilateral platforms in the international system, this

9 has not always been agreed by scholars. As Alden and Alves (2017:157) write, the debate over creating regional forums between China and Arab world or between China and Latin America took years before reaching any agreements and were accepted with some reluctance from China. Nevertheless, while there might be some discussion on whether China or its partners initiated the idea to create a particular forum, these multilateral initiations are potentially supported by China’s economy, norms and its diplomacy which, arguably, gives preference to Chinese interests in the first place (Jakobowski, 2018). This review of information suggests that China’s leadership ambitions are beginning to grow.

2.3 FOCAC and the quest for leadership in Africa

This section presents China’s quest for leadership in Africa, including Sino-Africa past and present relations. In addition, it demonstrates how these relations let the creation of the FOCAC- one of the regional forum initiatives signed by China and Africa.

China’s engagement with African countries is not a new phenomenon (Brautigam, 2009). The origin of Sino-African relations traces back to the long history of interchange which covers various aspects of politics, trade and economy (Brautigam, 2009:23). Broadly speaking, there have been two waves of Sino-African relations: past relations and contemporary relations. The two waves are dissimilar. While past relations were anti-colonial liberation movements, the contemporary has turned into economic relations (Ka, 2018:2). Thus, Motalini and Virtanen (2017:438) note that the ideological interest of the past helped to build the current Sino-African relations with an emphasis on being mutually beneficial and common development.

There are several reasons for China’s interest in cooperation with African countries. First, the interest is driven by economic factors (Sun, 2014:5). Scholars agree that China, fuelled by decades of high economic growth, is in high demand for key commodities that had largely outstripped domestic local production (Alves, 2013:211; Garver, 2016). China, in this view, was required to source these demands from overseas. Some may even argue that the new demands were the main reason for the shift in Chinese foreign policy. This policy came to be known as the ‘go global’ policy (Alves, 2013:208). The second reason is political. China needed support from other African countries on its one-China policy which prefers China’s sovereignty over Taiwan (Kent, 2013:141). In other words, in order to cooperate with China, African countries must accept the One China policy as the only lawful representative of China. In addition, African countries politically supported China to resume their seat at the United

10 Nations (Sun, 2014:4). Lastly, China is interested in security issues. Due to the vast geographical distance makes, China hardly faces a direct physical threat to its national or periphery security (Sun, 2014:9). However, China is very concerned about its economic activities in the African region. For instance, Chinese vessels were attacked by Somali pirates in 2008 by causing economic damages (Sun, 2014:11).

China, pushed by economic globalisation, accelerated Sino-African relations. This can be indicated by various exchanges of high-level visits and its officials’ statements to promote Chinese trade (Anshan et al, 2012:15). Zhou Enlai’s visits to African countries in 1963–65 started to establish the kind of image that China presents itself today: a moral partner with a clear differentiation from the West in its dealings with Africa, respect for sovereignty, equality and self-reliance, support for anti-colonial struggles and no-strings developmental assistance (Strauss, 2009:782). Similarly, chairman Jiang Zemin during his trip to Africa in 1996 stated that “the Chinese government encourages mutual cooperation, broadening trade, increasing African imports, and finally promoting the balanced and fast development of China-African trade” (Anshan et al, 2012:15). Each of these visits had one goal to further develop China’s strategic partnership with Africa.

In most of the cases, China’s cooperation proposals were welcomed in the corridors of power in Africa (Brautigam, 2009:12). There are several reasons that make China a preferred partner for Africa. First, Africans’ image of China is shaped by Chinese historical support to Africa’s freedom struggles (Ka, 2018:2). Second, African countries view China’s economic development as an example for Africa and Chinese financial support as new prospects for Africa’s development (Motolani and Virtanen, 2017:445). Third, China’s development model of mutual benefit and non-interference in African countries’ internal affairs favoured China’s cooperation proposals (Ka, 2018:6). Fourth, Africans view Chinese involvement as being efficient with “quick implementation and deliverables and in line with their priorities for the continent” (Motolani and Virtanen, 2017:445). Lastly, the Chinese proposals have given African governments an alternative to Western financing, thereby limiting their dependence on the developed countries; many African countries have seized this opportunity (Brautigam, 2009:12). As a result, China now has a strong diplomatic profile, embassies, and political offices across the African continent.

The increasing cooperation between China and African countries led to the foundation of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in Beijing in 2000. Enuka (2010:212) notes that the FOCAC establishment “clearly demonstrated the new character of Sino-African

11 relations in the new era” by becoming a forum for collective dialogue, rooted in the principles such as long-term stability, equality and mutual benefit. In the period since FOCAC was established, relations between China and Africa have deepened. This takes the form of increased two-way trade, higher investments, cultural exchange and greater development assistance for the African continent (Naidu 2008:169). Thus, Jakobowski (2017:660) affirms that throughout the existence of FOCAC, it developed into “a far-reaching dialogue platform” which includes various aspects such as economy, development, politics and cultural issues.

The FOCAC is based on five guiding principles and objectives that are issued in China’s Africa Policy White Paper in 2006: (a) sincerity, friendship and equality; (b) mutual benefit, reciprocity and common prosperity; (c) mutual support and close coordination and (d) learning from each other and seeking common development (White Paper, 2007). These economic and diplomatic agreements attempt to guide and shape contemporary Sino-African relations. Moreover, the FOCAC partnership has one conditionality - supporting the ‘One China’ principle, which implies no maintaining of official political relations or contacts with Taiwan as a sovereign state (FOCAC, 2006a). This conditionality is openly stated in all agreements and is clearly underlined as a prerequisite for cooperation with African countries (White Paper, 2007).

Nevertheless, the changes in both the scale and the visibility of China’s engagements with Africa, particularly, the Chinese government’s strategy of economic and political cooperation have attracted wide academic attention. Brautigam (2009:78) views China’s involvement in Africa as a well-thought-out strategy as well as manipulative cooperation for the search of raw materials to feed the demands of the growing Chinese economy. Making similar insinuations about China’s presence in Africa, Ka (2018:1) argues that these relationships “helped China to penetrate economically in many parts of Africa as a friend with total confidence and support from local politics”. Others view such cooperation as a lucrative opportunity for both parties (Anshan et al, 2012; Fernando, 2014:147). In addition to FOCAC, Enuka (2010:214) stresses that although this forum has encouraged mutual benefits for both African countries and China. Yet he problematizes China's leadership role and its danger to undermine Africa’s position in FOCAC.

12

CHAPTER 3

Theory

This chapter presents an introduction to the theoretical approach that is used for this research. The presentation focuses on the leadership theory as it was developed by the scholar Oran Young. This chapter is divided into two sections: (1) presents the concepts of leadership theory, including its meanings and interpretations; (2) concerns the relevance and the limitations of the leadership theory.

3.1 Theoretical Approach to the Study of Leadership

In IR, Oran Young has provided the concept of leadership from a behavioural perspective. Young (1991:306) emphasise that “much of the real work of regime formation in international society occurs in the interplay of bargaining leverage, negotiating skill, and intellectual innovation”. Thus, Young has developed three distinct types of leadership: structural leadership, entrepreneurial leadership and intellectual leadership. They relate to each other in shaping the related institution. This proposed way of understanding leadership in international bargaining is one way to analyse the context of China’s leadership role in the FOCAC process from a behavioural perspective.

Structural leadership (bargaining leverage in negotiations) is exercised by the state and

its officials who possess the most power, resources and have the greatest commitment issues under the negotiation (Deese, 2007:25-34). Meaning, in terms of power, resources and knowledge. Young (1991:288) specifies that structural leaders are experts in the process of translating the possession of material resources into bargaining leverage as a means of reaching agreement on the terms of constitutional contracts in the social settings. As suggested by Wehner (2011:142) in order to mobilize followers, structural leadership is exercised by using “carrots and sticks”. The “carrot” seems to describe material rewards, whereas the reference to “sticks” more closely reflects the use of threats such as sanctions. Thus Young (1991:290) concludes that to complete a successful agreement the promise of rewards or threats should be well thought, carefully designed and have credibility in itself for the others to follow.

13

refers to the bridging, building and shaping of coalitions through the use of consensual reasoning and negotiating skills (Young, 1991:293; Deese, 2007:34). In short, entrepreneurial leader crafts structures and applied domestic skills. Wehner (2011:142) also stresses leaders' capacity to mobilise passive actors who share a common interest but have not yet joined together for the achievement of such common goals. In addition, according to Young an actor with the effective negotiating skills may undertake several roles. These include: agenda-setter who presents the ideas for consideration at the international stage, populariser highlights the ideas, an inventor is responsible for developing policy options to overcome bargaining impediments and broker who makes an actual deal and brokers making deals and organises the support for salient options (Young, 1991:294). Having covered these rules, an actor will have strong negotiating skills.

Finally, intellectual leadership (the intellectual innovations governing international regimes) is the promotion of the ideas and language (Deese, 2007:35). According to Young (1991:298) “intellectual leader is an individual [state] who produces intellectual capital or generate systems of thought that shape the perspectives of those who participate in the institutional bargaining”. In short, the intellectual leader relies on the power of ideas to shape the intellectual capital. Young (1991:300) notes that “the intellectual leader is a thinker who seeks to articulate the systems of thought that provide the substratum underlying the proximate activities involved in institutional bargaining”. Although this type is an exclusively individual aspect, states may also utilize intellectual leadership due to their established identity (Wehner, 2011:142). In this paper, China may exercise intellectual leadership since it is seen as having an established identity.

In the process of regime formation, all different types of leadership appear at a certain stage in the simultaneous process. Whereas the first idea is initiated by the intellectual leader, the entrepreneurial leader plays an essential key in diffusing that idea, followed by structural leader’s ability to enforce a certain conclusion on the agreement. Moreover, although all three roles are not necessarily used to lead, this paper applies all three forms of leadership to examine the leadership role of China in the institutional bargaining process. Finally, this theory is applied to analyse state, rather than individuals with an argument that political individuals act in their capacity as state representatives. Thus, it is not important to strictly distinguish between them.

14

3.2 Relevance of the Leadership Theory

The key issue is to understand the complex interplay of leadership elements. Young’s typology directly and openly touches questions of leadership in the bargaining process with three central insights: (i) structural leadership; (ii) entrepreneurial leadership; and (iii) the intellectual leadership. Moreover, it directly integrates many different elements such as the role of power, material factors, the roles of ideas, the role of political will, and thus elements of bargaining perspectives (Deese, 2007). Additionally, Young’s leadership theory is a useful tool for understanding bargaining between states (Nabers, 2012:5). Thus Masciulli et al. (2009:3) affirm that political leadership helps “to account for significant differences across and within individual nation states” in relation to foreign policy and international events.

One of the purposes of applying leadership theory to this research is its ability to move beyond the traditional argument that hegemony and structural power are essential elements for the emergence or survival for international cooperation. Such beliefs “frequently fly in the face of reality”, especially, among IR students (Young, 1991:306). On the other hand, Young (1991) moves beyond this argument by noting that leadership from a hegemon is neither necessary nor sufficient for effective international institution building. Instead, leadership theory expands the scope of leadership by allowing to examine it from a broader perspective. Furthermore, the process of identifying and contrasting Young’s different types of leadership aims specifically to establish the existence of China’s leadership independent of the outcomes it is associated with. Young (1991:286) argues that leadership roles should not be studied with assumptions about its success because it limits “the development of propositions dealing with the relationship between the activities of leaders on the one hand and the outcomes of institutional bargaining on the other”. In this context, leadership theory will allow to systemize the performance of China’s leadership role, as well as explain in detail the eventual reasons for both: success and failure, when the role of leadership is played.

There are several limitations linked to Young’s theoretical approach to leadership. First, it has been criticized for being restrictive since it assumes that those capabilities are used only in the context of negotiation (Camilleri, 2003:122). In addition, Godehardt and Nabers (2011:143) stress that Young constantly refers to the term of leadership as a role in IR but does not provide further explanation of the leader role from a theoretical perspective (Godehardt and Nabers, 2011:143). Malnes (1995:106) notes that these divided “types of leadership are far from perfect”, however, as argued above, Young’s leadership theory is still relevant to examine China’s leadership roles in relation to both the African region and on the

15

global scale.

Young’s leadership theory is primarily and explicitly concerned with leadership questions of international regime formation in world politics. Thus, three types of leadership: structural, entrepreneurial and intellectual leadership allow this research to analyse the different capabilities of China’s leadership role in the international bargaining process. These capabilities include: the practice of the bargaining leverage, practise of the negotiation skills and practise of the intellectual innovations. Therefore, the adaptability and credibility of this theory are highly appreciated in this paper.

16

CHAPTER 4

Research Method for Studying the Leadership Role of China

The methodology section aims to provide clarification about the proposed research framework. In order to create an understanding of the conduct of the inquiry and to present how collected data will be used in the analysis, this chapter is divided into four parts: (1) explains the chosen research method that is used in this paper; (2) describes the data sources and data collection process; (3) presents validity and reliability and; (4) highlights the limitations of the chosen methods of inquiry.4.1 Approach to Research

This paper employs qualitative content analysis as a text interpretation method in the theory-driven case study research. Babbie (2001:304) defines content analysis as "the study of recorded human communications". In other words, this study collects and transforms the ‘raw data’ such as official documents and speeches into an organised form (Babbie, 2001). The content analysis will organise the data into specific phrases and short statements that will support the research. Additionally, theory-guided analysis “constantly compare theory and data—iterating toward a theory which closely fits the data" (Eisenhardt, 1989:541). Therefore, there is a relevant connection between China’s leadership role in the FOCAC process and Young’s leadership theory. Through a combination of the theory, qualitative content analysis and FOCAC official documents and speeches this relevance will be shown. Figure 1 visualizes the chosen method approach: qualitative content analysis from the theory to the analysis and interpretation.

17

Figure 1. Visual presentation of qualitative content analysis in theory-driven case study research

Source: Kohlbacher, Florian (2006)’ The Use of Qualitative Content Analysis in Case Study Research’,

Qualitative Social Research, (7:1), p.18.

Explaining the use of figure 1. Young’s theory is divided into three types of leadership. The FOCAC documents and speeches were coded with these three types. The documents were summarized, explained and structured into organised information. The organised information is applied and interpreted in the analysis chapter.

There are several reasons for applying qualitative content analysis in the theory-driven case study research. The first strength of a qualitative method is that it allows detailed analysis through the use of many different sources and addresses a broader range of historical, attitudinal, and behavioural issues (Yin, 2003:97). Thus, since qualitative content analysis includes methodologically controlled step-by-step procedures, it has an ability to investigate difficult-to-observe phenomena and hard-to-define concepts (Halperin and Heath, 2017:14). Hence, Stake (2010) notes that qualitative research allows for inquiry into what is not known. Besides, qualitative content analysis has an ability to “synthesize two contradictory methodological principles: openness and theory-guided investigation” (Kohlbacher, 2006:12). As a result, this thesis demonstrates how this research, in some way, contributes to a chosen theory by establishing the relation between both theory and empirical observation.

This paper employs theory-based ‘category system’. Titscher et al. (2000:58) refer it to coding: “every unit of analysis must be coded, that is to say, allocated to one or more

18 categories”. Thus Kohlbacher (2006:14) affirms that the central tool of qualitative content analysis is a category system (coding). The main strength of coding is that it, “forces the researcher to make judgments about the meanings of contiguous blocks” (Kohlbacher, 2006:10). Additionally, a theory-based category system is more open and flexible when it comes to the “extraction when relevant information turns up but does not fit into the category system” (Kohlbacher, 2006:17). Category system, in this view, can be adjusted consistently in the analysis.

4.2 Data Sources and Collection Process

This section presents a presentation of what type of data has been used, where it has been collected and how it has been collected. In other words, it presents the data collection process by highlighting the main undertaken steps.

Overall, this research project used desktop research. One common type of data for desktop research is secondary data (Halperin and Heath, 2017). The secondary data sources included speeches, official documents, reports and statistics from governmental sites, scientific articles, journals, books, internet sources and other literature. By using desktop research this study dealt primarily with reanalysing data that have already been collected for other purposes.

The main object- ‘text’ (figure 1) of qualitative content analysis is secondary sources that are produced and related to the FOCAC ministerial conferences between 2000-2018. These sources include official documents and speeches. The official documents and speeches from the seven FOCAC ministerial conferences are currently available on the FOCAC website. The coding of the data limited itself to notions concerning place, participants and, primarily, commitments. The summaries of the seven FOCAC ministerial conferences can be found in appx. 1.

The data for official documents and speeches is gathered from the following sources: Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (FMPRC), Ministry of Commerce People’s Republic of China (MOFCOM), official websites of Chinese Embassies in Zambia, Botswana and others. Additionally, the numerical data is collected from the following databases: The World Factbook in The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), UN Comtrade Database, China Africa Research Initiative (CARI) and Trade Map in The International Trade Centre (ICT).

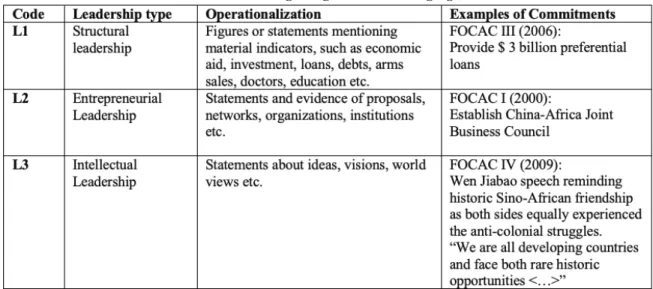

19 The data collection is based on three theoretical categories. The coding divided FOCAC commitments and speeches according to the nature of each leadership type. For instance, since the structural leadership is about structural power, one must view the material indicators such as Chinese provided loans for the African countries. This is just one example of how data collection helps to organise raw materials into a useful form. Table 1 visualizes how the data were coded according to the different types of leadership.

Table 1. Collecting categories in a coding agenda

Source: author’s own compilation

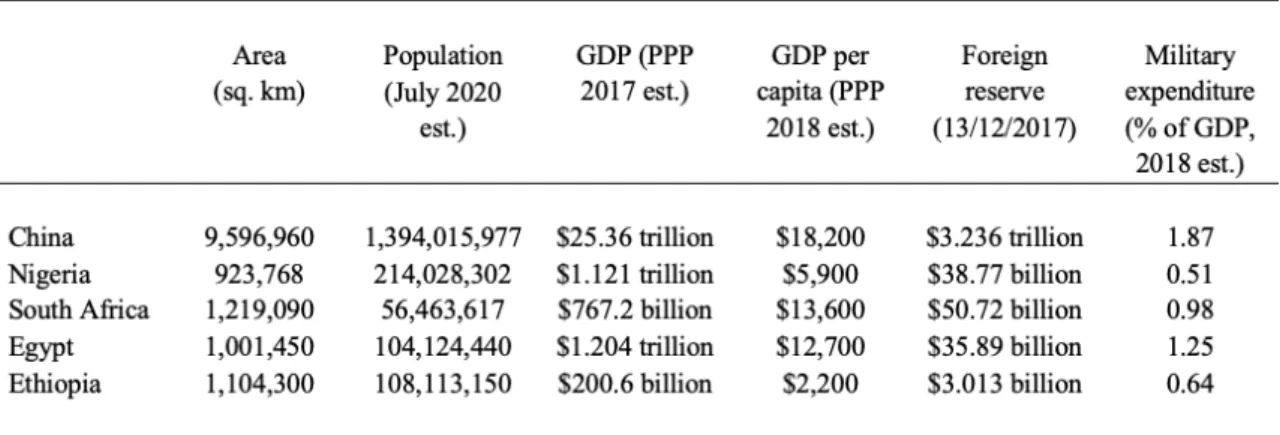

Since each of the leadership types is quite different in their nature, therefore the data collection is extended in a few cases. The structural leadership examines asymmetries in the distribution power among FOCAC countries. The numerical data is collected from the year 2018 to compare China and four other FOCAC members: South Africa, Nigeria, Egypt and Ethiopia. The selected African countries are the wealthiest countries ranked by GDP, followed by Ethiopia being number eight in the top ten (CIA, 2020). The selected countries are through the data compared with China in their size of population, territory, economic and military capabilities.

Such data is, arguably, more applicable for this analysis as it provides more concrete and clearly visualised information about asymmetries in the distribution power among FOCAC members. As a result, this data gives more depth to the understanding of the problem. Moreover, the study examines China’s share in the selected countries’ imports and their exports. This includes finding statistics of these countries’ total export and import with China, divided by their total trade worldwide. This type of information shows the dependence and independence between China and their trading partners.

20

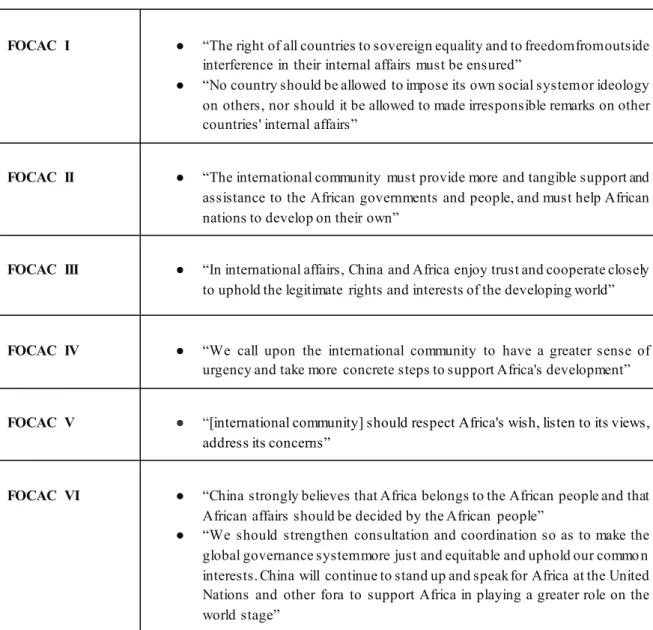

The data collection for intellectual leadership depended on the speeches at the FOCAC opening ceremonies from 2000-2018. These speeches, arguably, represent the Chinese way to express their views and ideas to the wider FOCAC public. The key phrases in the data were based on the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence. These principles guide the FOCAC platform. Overall, all data collection for intellectual leadership aims to examine China’s ideas, views and their sustainability or flexibility to change over the period of FOCAC existence.

4.3 Validity and Reliability of the Method

This section presents the criteria of validity and reliability for qualitative content analysis method in theory-driven case study research. When discussing validity, the importance is on the theoretical relevance to the empirical analysis (Halperin and Heath, 2017:355). In this study, the materials are reconstructed under the three theory-driven categories: structural leadership, entrepreneurial leadership and intellectual leadership. Each category is followed by theoretically based definitions (table 1).

Such data collection allows for precise sampling. In this view, the validity is material oriented. Moreover, the chosen method shows process-oriented validity. The thesis emphasizes the clear process of the collection of the data. Finally, to strengthen the validity of the study, several kinds of data collection processes were used. For instance, the numerical data approach is employed to support the results of structural leadership. Also, secondary sources such as academic journals and books were used to support the findings.

The reliability of this paper depends mainly on two factors. First, to ensure reliability it is important to have consistent methods (Harrison, 2013:129). For example, by the use of figure 1, this study follows a consistent method of coding. Second, qualitative methodologist stresses the importance of transparency (Armstrong et al, 1997:598). Therefore, all sources used are represented in the reference list. Through these two considerations, the study has concern itself with the aspect of reliability.

4.4 Limitations of the Method

As with every study, this study has several limitations. This section of the chapter will go through the restrictions to help to comprehend the results of the research in a broader manner.

21 Halperin and Heath (2017:14) highlight the limitations of qualitative content analysis methods by stressing that “its findings might not have wider relevance to contexts outside the immediate vicinity of where the research was conducted”. Thus, Kohlbacher (2006:1) affirms that qualitative research method as data analysis is described as unscientific, or only exploratory and subjective. In this case, any outcome of this research is unlikely to make predictions about the future of China’s position as a global leader in general and China’s leadership role within multilateral platforms in particular, nor about the Sino-Africa relations, but is rather limited to theoretical beliefs. In this case, one may argue that a case study method does not adequately address the complexity of China's leadership role in the international regime formation

.

To some extent, these arguments are applicable to this paper as well. However, Flyvbjerg (2014:120) argues that such criticism can be applied to all research methods and other qualitative methods. Therefore, this paper does not deny the existence of limitations that exist through the chosen method, rather it shows its potential weaknesses. Yet, despite these limitations, this thesis aims to overcome these shortcomings by producing coherent knowledge and having a clear focus. In addition, it examines a variety of academic sources, including the use of political theory.

When discussing data collection, since data comes, mainly, from secondary sources, it comes with a challenge to avoid bias information. The official Chinese publications often have a highly promotional nature and use grand language to describe China-Africa cooperation. For instance, the White Paper on China’s African Policy 2006 reads as follows: “China and Africa have all along sympathized with and supported each other in the struggle for national liberation and forged a profound friendship” (White Paper, 2007:376). In order to avoid bias information in secondary data, the study critically collected data from official FOCAC documents.

Although large numbers of FOCAC and Chinese foreign policy documents, official reports and speeches can be found online, for example on the FOCAC official website, yet documents are quite limited in their public nature. Meaning, that the insight into the direction and the scope of the documents are quite limited. Additionally, several events are described very briefly while others contain more information. For instance, the FOCAC official website provides limited information about the FOCAC II ministerial conference held in 2003. It misses wider insights and has quite limited information about commitments. In order to avoid such weakness, it looks at these findings critically and seeks confirmation from other sources

22

such as academic journals and others before accepting certain claims. On the other hand, FOCAC VII contains a lot of commitments. Most of them is a continuation of previous FOCAC conferences. In this way, the collected information presents only new statistics and new establishments.

Moreover, both China and Africa are known to have unreliable data (CARI, 2020). The information from certain countries is limited due to the inconsistent trade reports from African and Chinese governments. For instance, “figures for Chinese imports from South Africa as reported by the Chinese government are much larger than those reported by the South African government” (CARI, 2020). Additionally, several important Chinese trade partners such as Libya, Gabon, Algeria and Equatorial Guinea did not provide their trade reports for the year 2019. In order to move from limitations, this study relied on the year of 2018 summary. Such data has more validity since it provides more consistent results and currently exists on the databases.

23

CHAPTER 5

Findings and Analytical Discussions

This chapter contains an analysis of the leadership role of China in the FOCAC process. For analytical clarity and simplicity, this chapter is divided into three main themes. These include (1) structural leadership: practice of bargaining leverage; (2) entrepreneurial leadership: practice of negotiation skills and (3) intellectual leadership: the practice of intellectual innovations.

5.1 Structural Leadership: Practise of Bargaining Leverage

The ability of a state to practise its bargaining leverage for the advancement of agreements comes from its structural power vis-a-vis other members. In reality, it means that there exist asymmetries in the distribution of power among parties (Young, 1991:289). The asymmetries refer to inequality in states’ power possessions such as military and material resources. Despite the fact that this paper chose the wealthiest African members, it is clear that China is the asymmetrical partner in the relations to the African FOCAC states. Table 2 provides FOCAC members’ (Nigeria, South Africa, Egypt and Ethiopia, including China) most important statistics regarding their size of population and territory, same as economic and military capabilities.

Table 2. Economies of FOCAC members

Source: The World Factbook, CIA, www.cia.gov/index.html, accessed:19/4/2020 (author’s own

24 Evidently, China is a FOCAC representative with more power compared with the other members. Whether in terms of economic and military capabilities, there is a large gap between them. Overall, all four African countries remain little actors in comparison to the Chinese area, population, economy and military power. Particularly, Ethiopia’s military and economy accounts for a small part of China’s wealth. In table 2 Nigeria has an advantageous position in terms of economy. Egypt and South Africa have greater military power than all the other selected African countries. However, it does not change the structural power when compared to China. It means that African countries collectively and in terms of individual states are not able to reach the same economic and barely military capabilities as China currently has. Therefore, it can be concluded that there is a clear asymmetry among the FOCAC member states. As a result, it allows China to exercise its structural power in the African continent.

Leadership under structural power raises an important question of “what an actor stands to lose or gain relative to what others stand to lose or gain from institutional bargaining” (Young, 1991:289). Table 3 visualizes China’s top five trading partners in Africa. On the left side of the table, one can see African imports to China, while on the other side it shows China’s share in African exports.

Table 3. African countries by China’s share in their imports and their exports, 2018

Source: Trade Map, https://www.trademap.org/, accessed:25/4/2020, (author’s own compilation)

This table indicates that for several African countries, China is the dominant trade partner. For instance, Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo export to China is 57% and 51% of their total exports. Kenya, Tanzania, Nigeria and South Africa import from China 21, 20,6, 19,4, 18,3%, respectively, of their total imports (Table 3). On the other hand, Africa is still a minor trade partner for China. According to the UN Comtrade data, only 4,2% of China’s total exports and 4,6% of China’s total imports in 2018, followed by the year 2019 with imports of only 4,5% and 4,5% of total exports to Africa.

Furthermore, most of the FOCAC members are fragile states with underdeveloped economies, political instability and poverty (Aiping and Zhan, 2018:102). In this way, main

25 Africa’s motivation to cooperate with China is economic development (Ka, 2018:6). The African leaders hoped that the FOCAC would strengthen the trade and economic ties between them and China. Moreover, the Chinese proposals and its conditions for cooperation seem to be appealing for African states (Motolani and Virtanen, 2017:445). In addition, Africans see the Chinese presence in the continent as the good leverage on which they can balance the power of the traditional hegemony of the West (Brautigam, 2009:12). The conclusions from the table 3 could suggest that the development rate of Africa suggest that African countries are important for China, both economically and politically. Numbers show that China stands to gain more and lose less, relative to what African countries separately stand to lose or gain from FOCAC.

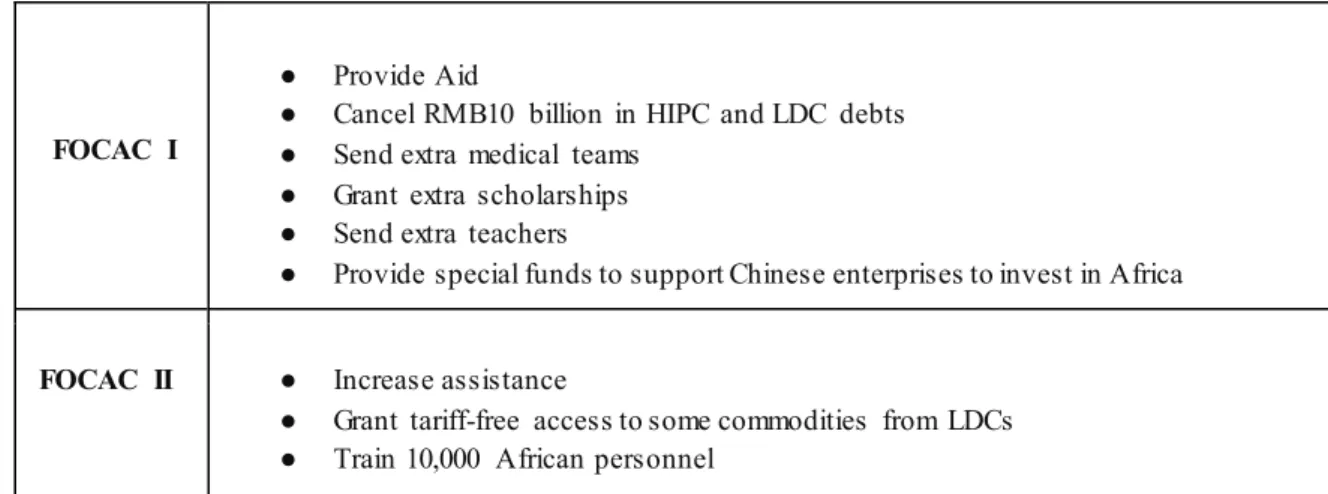

Actors with structural leadership are not only the ones who possess the most resources but also are experts in translating the material capabilities into leverage for the bargaining process (Young, 1991:289). Table 4 provides figures and statements highlighting material indicators that have been proposed during the seven FOCAC conferences. These commitments cover economic aid, investments, loans, cancellation of debts, doctors, education, military and other sectors.

Table 4. L1: Structural Leadership

Evidence of material indicators: Economic aid, investment, cancel debts, doctors, education, etc.

FOCAC I

● Provide Aid

● Cancel RMB10 billion in HIPC and LDC debts ● Send extra medical teams

● Grant extra scholarships ● Send extra teachers

● Provide special funds to support Chinese enterprises to invest in Africa

FOCAC II ● Increase assistance

● Grant tariff-free access to some commodities from LDCs ● Train 10,000 African personnel

26

FOCAC III

● Double aid by 2009 (from 2006)

● Provide $ 3 billion as preferential loans; $ 2 billion as preferential buyer's credits ● Offer zero-tariff treatment to 30 African LDCs; increase the number of export items

from 190 to 440

● Provide RMB 300 million for artemisinin (anti-malaria drug); build 30 malaria prevention centres; build 30 hospitals

● Cancel debts owed by HIPCs that matured at the end of 2005

● Train 15,000 African professional; send 100 senior agricultural experts

● Dispatch 300 youth volunteers

● Increase the number of scholarships for African students from 2,000 to 4,000 per year; build 100 rural schools

● Build an AU conference centre

FOCAC IV

● Provide $ 10 billion in concessional loans; $ 1 billion for African small and medium-size business

● Cancel debt associated with interest-free government loans due to mature by the end of 2009

● Give zero-tariff treatment to 95% of products from African LDCs

● Build 50 schools; train 1,500 school principals; increase Chinese scholarships to 5,500 by 2012

● Build 100 clean energy projects

● Carry out 100 joint scientific and technological research projects; accept 100 postdoctoral fellows to conduct scientific research in China

● Build 20 agricultural centres; send 50 agricultural technology teams to train 2,000 African technicians

● Provide medical equipment worth RMB 500 million; train 3,000 doctors and nurses

FOCAC V ● Scale funds up to $ 5 billion

● Zero-tariff treatment to products under 97% of all tariff items ● Provide $ 20 billion aid

● Train 30,000 African professionals; offer 18,000 scholarships

● Provide free treatment for African cataract patients; send 1,500 medical workers ● Provide $ 2m million for education projects; sponsor 100 academic programs

FOCAC VI ● Provide $ 60 billion: $5 of free aid and interest-free loans; $ 35 billion of preferential loans, $ 20 commercial assistance

● Provide $ 5 billion of additional capital for China-Africa development fund ● Train 200,000 technicians; provide 40,000 training opportunities in China ● Offer 2,000 education opportunities (diploma); provide 30,000 scholarships; invite

2,000 African scholars

● Cancel debts matured at the end of 2015

● Provide $ 156 million of emergency food to LDCs ● Sent 30 teams of agricultural experts

27 FOCAC VII ● Provide RMB 1 billion of emergency humanitarian food assistance; send 500 senior

agriculture experts to Africa

● Provide regional aircraft for civilian use; train aviation professionals; provide capacity building

● Build innovation centres, internet connectivity ● Provide $10 billion aid assistance

● Zero-tariff treatment for 97% of tax items from African LDCs ● Provide $5 billion special funds for financing imports from Africa

● Extend $20 billion of credit lines; support the setting up of a US$10 billion special fund for development financing

● Grants $15 billion, interest-free loans and concessional loans to Africa

● Train 1,000 high-calibre Africans; provide 50,000 scholarships; provide 50,000 training opportunities for seminars and workshops

● Provide 150 African students to receive master's or PhD education in China ● Invite 200 African scholars to visit China

● Invite 2,000 young Africans to visit China

● Provide 100 million dollars military assistance in support of the African Standby Force and African Capacity for Immediate Response to Crisis

● Train 100 African anti-corruption officials ● Set up a China-Africa peace and security fund

Source: FOCAC 2000-2018, https://www.focac.org/eng/, accessed:25/4/2020, (author’s own compilation)

These material indicators demonstrate China’s ability to translate its material capabilities to leverage bargaining in the FOCAC process.

China made a consisted effort to rectify the trade deficits of least developed African countries (LDCs) through FOCAC by increasing their exports to China (Fernando, 2014:154). For instance, by the second FOCAC ministerial conference, China confirmed to forgive of debt owed by the least developed African countries (LDCs). As a result, 190 commodities from 28 African LDCs fell under the tariff-free policy (Anshan et al, 2012:58). Additionally, the fourth FOCAC conference, over 4,700 items covering 95% of commodities enjoyed tariff-free policy (Anshan et al, 2012:60). The implementation of the tariff-tariff-free measures in FOCAC VII have resulted in LDCs countries enjoying zero-tariff treatment covering 97% of exports to China. This suggests that China’s efforts through FOCAC to increase exports from the least developed African countries were consistent and effective.

Under the African Humanitarian Resource Development Fund (AHRDF) established after the first Forum in 2000, Chinese also pledged to provide strong support for the educational and health sector (Alves and Alden, 2017:160). In FOCAC III, China offered about 2,000 scholarships per year for Africans to study in China. The number doubled to 4,000 per year by 2009, followed by 18,000 offered in FOCAC V with the last number of 32,000 government scholarships provided to Africa by China in FOCAC VII. In addition, up

28 to the last FOCAC conference, China provided financial support to build schools in rural areas, trained school principals, sponsored agricultural research programs.

Furthermore, China provides financial assistance to the health sector. For instance, in FOCAC III China offered to build 30 hospitals and 30 malaria prevention centres. China also provided RMB 300 million (about $40 million) for artemisinin (antimalarial drug) in 2006 and increased the amount to RMB 500 in 2009. Additionally, China provided financial assistance to train 3,000 doctors and nurses for Africa in 2009. By the fifth FOCAC meeting, China financed free cataract treatment for African people.

It is noteworthy to look deeper at China’s financing commitment made to Africa at the sixth FOCAC meeting in 2015. Indeed, the FOCAC VI financial commitment from China to Africa differ from past ones. Looking at the FOCAC meetings’ period between 2000-2012 can be seen in China’s pattern of doubling financing commitments at each FOCAC meeting. For instance, the financial assistance in previous meetings went from $5 billion in 2006, to $10 billion in 2009, and to $20 billion in 2012. However, at the FOCAC VI ministerial conference, China tripled it by totalling $60 billion.

Furthermore, the difference between FOCAC VI and previous commitments is situated in the ‘composition’ of the financial promises. For example, in the FOCAC III meeting, China specified that the provided assistance of $5 billion consisted of $3 billion preferential loans and $2 billion of preferential buyer’s credit. Similarly, in FOCAC IV, provided $10 billion was entirety given to the concessional loans. Contrary, in FOCAC VI, the $60 billion were divided only into $5 billion for grants and zero-interest loans and $35 billion for preferential loans while the rest 20 billion were given to additional commercial financing. This could suggest that either China is more confident in the economic future with Africa or that China is becoming more intrusive and comfortable in its role as a structural leader.

Under the establishment of China-Africa Cooperative Partnership for Peace and Security in 2012, China began to assist military projects financially (Lema, 2019). For example, in FOCAC VII China provided $ 100 million funds for military assistance in support of the African Standby Force and African Capacity for Immediate Response to Crisis. This proposal to finance security relations reflects China’s changing position and wish to start security cooperation as well. Lema (2019) argues that financing security sector, China tries to promote national interests such as ensuring access to resources, accessing the growing African market protection of its economic investments as well as the safety of its surging number of

29 citizens in Africa. Moreover, during FOCAC VII China suggested to launch a China-Africa security fund.

Of the two traditional hegemon choices, it is evident that China exerts its structural leadership through the promise of material rewards, rather than the use of coercion (Kent, 2013:137). In other words, the main bargaining chip of China, so as to make African countries cooperate, is Chinese granted large direct assistance to the FOCAC member states. On account of China’s economic strength when compared with the other FOCAC members, China has the ability to provide more immediate benefits to African states (Motolani and Virtanen, 2017:445). As a result, Chinese political capital as a great power is accepted among African nations.

Yet, the behaviour of a structural leader is often based on self-interest (Young, 1991:293). In its participation in FOCAC, China, like most states, seeks to maximise its power and interests (Kent, 2013:155). In this case, one can argue that Chinese practise of leverage bargaining is self-serving to promote their own values and its structural power has the ability to enforce and change the goals of African states to suit those of China’s. This suggests that FOCAC members become Chinese instrumental actors that share similar aims in a specific course of action and in a particular outcome.

China’s structural leadership also presents some of the limitations of China’s involvement in the African region. What complicates the Chinese involvement in the African continent is that China is not the only and most power hegemon in the region (Strauss, 2009:752). The African continent is the traditional West sphere of influence (Alves and Alden, 2017). In particular, the increase in China’s influence in the region is against the wishes of the US since it poses a threat (Fernando, 2014:156). Despite Chinese reassurance that FOCAC is beneficial to all partners, the US considers FOCAC as China’s tool to make its mark on the region (Harrison, 2004:93). These obstacles limit China’s practise of structural power.

To sum up, looking from the structural leadership form, China has a clear lead in the FOCAC due to its structural power. Africa consisting of 54 states of which 53 have diplomatic relations with China. Among them, China has a structural advantage. As a result, African countries cannot present the FOCAC agenda vis-a-vis China. Additionally, these China’s material rewards cover almost all sectors. Moreover, on account of China’s economic strength when compared with the other FOCAC members, China has a great power ability to exercise bargaining leverage by providing more immediate benefits to African states. This suggests

30 although FOCAC meetings layout common policy objectives, Chinese values, norms and interests are more likely to be employed in policies and structures of FOCAC.

5.2 Entrepreneurial Leadership: Practise of Negotiating Skills

Entrepreneurial leadership represents an actor's abilities and skills in the negotiating process at the international regime formation. As mentioned in the theory chapter, an actor with effective negotiation skills may act as an agenda-setter, a populiser, an inventor and lastly as a broker (Young, 1991:294). These abilities are used to convince and attract the other side towards an agreement. This part examines whether China has played any of these roles in the FOCAC process, including its negotiation skills in general.

Compared to other FOCAC members, China sets most of the agenda in the FOCAC process (Anshan et al, 2012:38). This can partly be attributed to China's structural power which gave special opportunities to influence the FOCAC agenda. Figure 2 visualizes FOCAC decision-making procedure where it clearly shows that agenda is set by China.

Figure 2. FOCAC decision-making procedure

Source: Anshan et al, 2012:38, FOCAC Twelve Years Later, pp.38

This visualization provides evidence that although FOCAC was institutionalized at its first ministerial conference, there is no organisation established to represent and guide African policy framework (Anshan et. al, 2012:38; Mthembu and Wekesa, 2017:2). In addition, most of the FOCAC members lack well thought out frameworks towards China which consequently