Digital Avenues for

Sustainable Clothing

BACHELOR PROJECT

THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Sustainable Enterprise Development AUTHOR: Nils Andersson, David Lozano

JÖNKÖPING: 24 May 2021

A qualitative study exploring digitalization’s facilitating

effects to improve clothing companies’ sustainability.

i

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge and express our sincerest gratitude to everyone that made the thesis possible. It has been an arduous journey, that would not have been possible without the contributions of many individuals.

Firstly, we would like to thank our tutor Quang Evansluong, PhD for always pushing us to strive for higher limits and more perfection. Your insight and feedback throughout this entire process has truly encourage this thesis to the result it has become. Moreover, we would like to thank each and every colleague from our seminar group for their productive input, in addition to Anders Melander for providing the guidelines and course material.

Additionally, extend a special thanks to every interviewee for their time, effort, and input within this study. Their knowledge and insights made this entire research project possible. Furthermore, on a more personal note, their efforts to create a more sustainable world were deeply inspiring to both of us.

We would also like to thank everyone who gave us feedback and contributed to the final result of this thesis: Mark Edwards, PhD and Prince Chacko Johnson.

Finally, during the challenging times of the COVID-19 pandemic, we would like to thank the creators of Microsoft Teams for allowing us to conduct each of the interview safely and effectively.

ii

Bachelor Thesis Project in Business Administration

Title: Digital Avenues for Sustainable ClothingAuthors: Nils Andersson and David Lozano Tutor: Quang Evansluong, PhD

Date: 2021-05-24

Key terms: Digitalization, Digital transformation, ICTs, Sustainability, Clothing industry

Abstract

Background: Digitalization and sustainability are two of the most impactful topics concerning

businesses today which pose a nascent research field. Sustainability presents businesses with massive challenges in order to find new business models, improve processes, utilize resources more efficiently, and change their interactions with suppliers and other stakeholders. Simultaneously, digitalization is often characterized by its disruptive nature and the ways in which it creates new avenues for creating and capturing value and changes relationships. Furthermore, there are few industries in need of new ways to become more sustainable than the clothing industry.

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to explore the facilitating opportunities that digitalization presents for the clothing industry to achieve sustainability goals. The findings of this study are expected to contribute beneficial knowledge and concrete examples that managers, decision-makers, and IT personnel can use to better understand the existing prospects that digital transformation poses for their various sustainability goals.

Method: A qualitative design has been employed to perform this study. Five semi-structured

interviews were conducted with various individuals representing Swedish clothing brands. An inductive approach was utilized alongside a grounded theory design.

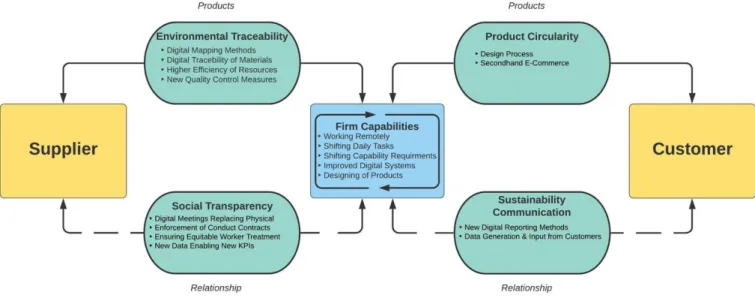

Conclusion:The results show that there are many opportunities for digitalization to facilitate clothing companies’ sustainability goals. This comes in the form of enabling effects with their downstream suppliers through: improved environmental traceability, shifting supplier relationships, and improving working condition transparency. Moreover, upstream effects are observed in adaptions to new business models and relationship improvements with consumers. Finally, within the firm, improving processes and shifting capability requirements are changing the way that firms operate, and the knowledge sets needed to function. These findings were developed into a framework presented on page 40.

iii

Table of Contents

... 1 1. Introduction ... 1 1.1 Background... 1 1.2 Problem Discussion ... 3 1.3 Research Purpose ... 4 1.4 Research Question... 5 1.5 Delimitations ... 5 2. Theoretical Framework ... 72.1 Method for the Theoretical Framework ... 7

2.2 Digitalization ... 9

Digitalization’s Evolution ... 9

Digitalization’s Transformative Power ... 10

2.3 The impact of the clothing industry on sustainability ... 13

Defining sustainability ... 13

Clothing industry’s environmental sustainability impact ... 14

Clothing industry’s social sustainability impact ... 17

2.4 UN Sustainable Development Goals Linkage to Topic ... 18

2.5 Sustainable Transformation of the textile industry ... 19

Consumer’s increasing demand for sustainable production ... 19

Clothing industry’s business model transformation ... 21

2.6 Theoretical summary ... 22

3. Methodology and Method ... 23

3.1 Methodology ... 23

Research Paradigm ... 23

Research Approach ... 23

Research Design ... 24

3.2 Method ... 25

Primary Data Collection ... 25

Sampling Approach ... 25

Semi-Structured Interviews ... 26

Interview Questions ... 28

Data analysis ... 29

Selection of quotes ... 30

3.3 Secondary Data Collection ... 31

3.4 Ethics ... 31

Anonymity and Confidentiality ... 32

Credibility ... 32

Transferability ... 33

Dependability ... 34

Confirmability ... 34

4. Findings and Discussion ... 35

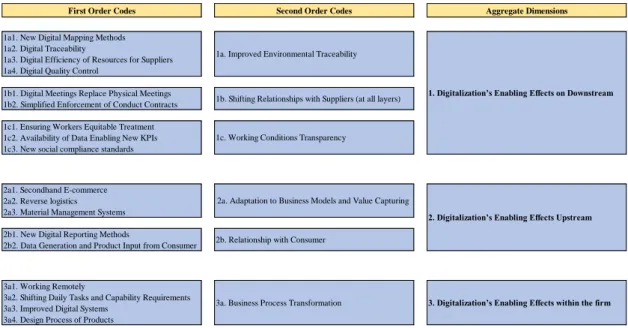

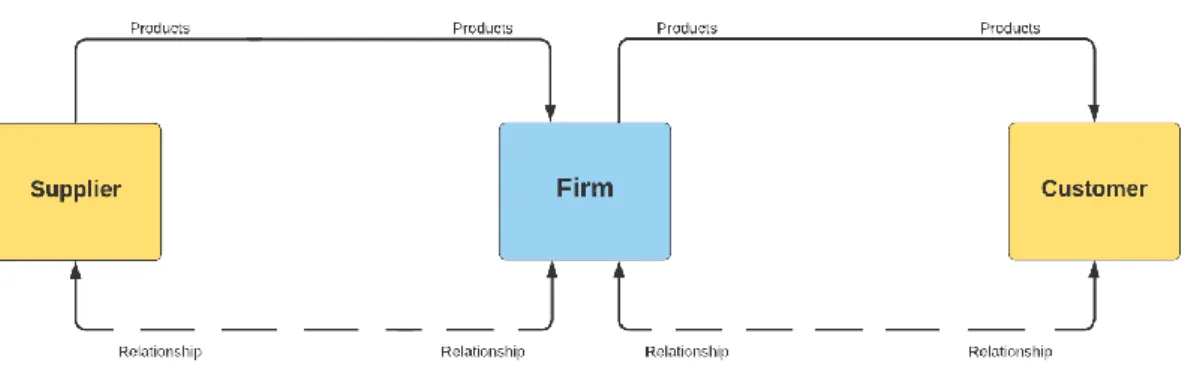

4.1 Conducting Findings & Analysis ... 35

4.2 Digitalization’s Enabling Effects on Downstream ... 37

iv

Improved Environmental Traceability ... 39

Working Conditions Transparency ... 42

4.3 Digitalization’s Enabling Effects Upstream ... 43

Relationship with consumer ... 43

Adaptation to Business Models and Value Capturing ... 45

4.4 Digitalization’s Enabling Effects within the firm ... 48

Business Process Transformation ... 48

5. Conclusion ... 52 6. Discussion ... 54 6.1 Theoretical Contributions ... 54 6.2 Practical Implication ... 55 6.3 Future research ... 55 6.4 Limitations ... 56 References ... 58 Appendices ... 74

Appendix 1: Interview Protocol ... 74

Appendix 2: Interview Consent Form ... 76

1

1. Introduction

_____________________________________________________________________________________

This chapter introduces the emergent relation nature of digitalization and sustainability. Furthermore, a problem discussion is presented, leading to the stated purpose and research question of the study. Finally, the apparent delimitations are discussed.

1.1 Background

Digitalization and sustainability are two crucial topics that have reached a crossroads. The convergence of these two topics means a changing business landscape and the creation of ripple effects across all industries (Kiron & Unruh, 2018). Both are highly contextual, and their effects change from one instance to the next (Köhler et al., 2019; Waas et al., 2011). One thing is clear though, the necessity of enterprises to adopt digital technologies to compete in today’s global marketplace and outperform competitors is crucial (Denicolai et al., 2021; Parida et al, 2019; Yoo et al. 2010). Additionally, businesses are decisive actors that must be engaged for society to achieve a sustainable transition (Cordova & Celone, 2019; Van der Waal & Thijssens, 2020; van Zaten & van Tulder, 2018). Investigating the exact interplay between the strategic digital transformation and the ability to achieve sustainability goals is still a nascent, yet crucial, field (Del Río Castro et al., 2021; Seele & Lock, 2017; Wu et al., 2018). This is especially significant if this sustainable transition is to be achieved in a way that does not further compound over-consumptive and non-sustainable habits of both society and enterprises (Helbing, 2012). Due to its innovative nature, digital transformation and the further implementation of information and communication technologies (ICTs) have the ability to increase efficiency, promote dematerialization and facilitate more optimized business models (GeSI, 2016; Hilty et al., 2011; Weber et al., 2010). Moreover, digitalization has been postulated as one of the most promising prospects in the sustainable development (SD) of society (Gouvea et al., 2018) and transitively, business. These beliefs are based upon how digitalization enables improved efficiency and implementation of: resource productivity, evidence-based decision-making, Environmental Social Governance (ESG), and altered paradigms for both investors and consumers (Holst et al., 2017; Kiron &

2

Unruh, 2018; Seele, 2016; Tjoa & Tjoa, 2016;). Furthermore, digitalization has been postulated to assist in redefining organizations´ relationships with customers (Mergel et al., 2019), employees (Vial, 2019), and their environmental resources (Atos, 2019; Gebhardt, 2017). These types of synergies are made possible because of the implementation of technologies that fall under the paradigm of ‘digitalization’, namely,

“Big Data Analytics, Artificial Intelligence (AI), Internet of Things (IoT), Blockchain or Distributed Ledger Technologies, Quantum Computing, among others…” (Del Río

Castro et al., 2021).

Until recently, the relationship between digitalization and sustainability has been primarily explored through the quantitative scope of measuring the metric data of energy consumption or carbon emissions under the terms “’Green IT’ or ‘Sustainable ICT’” (Del Río Castro et al., 2021). Supplementary research on this topic has further shown how Big Data analytics can improve both the transparency and accountability of firms, by making previously hidden connections - more accessible (Seele, 2016; Seele & Lock, 2017; Zhao et al., 2017). Furthermore, the availability of these new data points allows firms to more easily: analyze, adapt, and respond to their environmental and social impacts (GeSI, 2019; Tjoa & Tjoa, 2016). Likewise, a key characteristic of digitalization is the way in which socio-technological development occurs (Parviainen et al., 2017), which enables the opportunity to adapt business models and disrupt competitive markets (Yoo et al., 2010). These new business models allow firms new opportunities to create and capture value, while simultaneously generating the potential for higher sustainability (Parida et al., 2019).

Largely, this phenomenon can be summarized by two paradigms: the ways in which digital transformation can potentially enable sustainable transformation, and the sustainability of said digital transformation (van der Velden, 2018). The importance of the former has been touched upon above, although the crucial nature of the latter should not be understated (Etzion & Aragon-Correa, 2016). Should the sustainability of digitalization not be considered, it poses the hazards of serving to make existing social, environmental, and economic vulnerabilities worse (Helbing, 2012). Both perspectives offer large opportunities for future research and the lack of consensus amongst scholarly literature serves to highlight the importance of studying this field.

3

Understanding and applying these two paradigms is essential for nearly every industry (Kiron & Unruh, 2018). However, there are few in need of sustainable development more than the clothing industry. This statement is reinforced by the fact that the fashion industry is one of the industries that pollute the most (Niinimäki et al., 2020). Beyond the overwhelming environmental devastation, very often the fashion industry is associated with negative social and working conditions like child labor, low wages, health risks, and insufficient worker safety (Pedersen & Andersen, 2015; Pedersen et al., 2018). For this reason, this research will explore the potential that digital transformation can impart in facilitating the sustainable transition of the clothing industry.

There are many prerequisites that must be fulfilled for sustainable digital transformation to occur (Beier et al., 2017; Hofstetter et al., 2020) especially within the clothing industry. Therefore, enabling managers and decision-makers with ways to understand how digital transformation can lend to the betterment of social and environmental interests is crucial.

1.2 Problem Discussion

The connection between digitalization and sustainability is an ever-growing field of research still in its nascent stages, presenting many research gaps (Del Río Castro et al., 2021; Goralski & Tan, 2020; Yan et al., 2018). Both topics have been researched very thoroughly in their own rights. For this reason, one can understand the ways that digitalization has shifted firms´ relationships with: consumers (Berman, 2012; Kane, 2014; Mergel et al., 2019), employees (Dremel et al., 2017; Hansen et al., 2011; Hess et al., 2016), and suppliers (Deloitte, 2017). Furthermore, the disruptive nature of digitalization is well documented (Legner et al., 2017; Karimi & Walter, 2015; Sebastian et al., 2017; Vial, 2019; Yoo et al., 2010). Synchronously, the research field of sustainability and its impact on: business operations (Cordova, & Celone, 2019; Kahn & Kotchen, 2011) and the importance that business practitioners contribute in achieving sustainability (CSIL, 2017; van der Waal & Thijssens, 2020; van Zanten & van Tulder, 2018) has a sizeable amount of scholarly literature behind it. However, it is within the intersection of these two important topics where future research is needed.

4

Goralski & Tan (2020) explored that there is little overall academic consensus on the relationship between digitalization and its ability to enable SD. Frequently, this relationship is touted as a win-win scenario (Del Río Castro et al., 2021) and recent research has begun to explore the possibilities of the positive relationship between digitalization and sustainability (GeSI, 2019; Gerbhardt, 2017; Paria et al., 2019; Tjoa & Tjoa, 2016). In fact, numerous examples and instances of how digitalization can enable a shift towards sustainability are given within academic literature (Atos, 2019; Holst et al., 2017; Seele, 2016; Seele & Lock, 2017; Tjoa & Tjoa, 2016; Zhao et al., 2017). However, the exact implementation of these technologies and the resulting effects are primarily spoken about in rather general terms. Conversely, there is an additional field of scholarly literature that has raised concerns and warning signs about the complicated nature of sustainability and digital transformation (Bekaroo et al., 2016; Osburg & Lohrmann, 2017; Strubell et al., 2019; van der Velden, 2018).

A major challenge facing this research field is its highly contextual nature of both digitalization and sustainability thus, calling for the need to focus on specificities presented by these different contexts (Letouzé & Pentland, 2018). Therefore, the objective of this research is to observe the phenomenon of how digitalization facilitates sustainability efforts within Swedish clothing companies. Qualitative data will be gathered from various Swedish companies to draw a correlation between digitalization’s facilitating effects on the achievability of their sustainability goals. By doing this, the researchers intend to add their contributions to the pioneering efforts to materialize the vital relationship between sustainability and digitalization.

1.3 Research Purpose

The purpose of this research is to expand the ever-accumulating body of literature, by better understanding the relationship between these two forces driving business decisions. Primarily, the researchers examined how digital transformation and further implementation of digital technologies (ICTs amongst others) contribute towards achieving sustainability goals. As of now, gaps exist with regards to how digitalization creates, delivers, and captures value; in terms of sustainability (Parida et al., 2019).

5

Furthermore, the relationship between ICTs and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) at the micro-level is not fully understood (Del Río Castro et al., 2021).

To explore this phenomenon, primary data will be gathered through interviews with appropriate individuals of Swedish clothing companies. By drawing correlations from the primary and secondary data sources, this research can overlay the relational implications of these two forces to conclusions. Doing so will assist in helping to define the intricate and multi-faceted nature that often characterizes this research field. Finally, even though the data is collected from firms headquarter in Sweden, it is the intent of the researchers that the findings be applicable on an international context and/or to other industries with similar organizational structures.

1.4 Research Question

To investigate the stated purpose, the following research question has been postulated:

How does strategic digital transformation facilitate clothing companies’ goals towards sustainability?

1.5 Delimitations

This research has several different delimitations that have been taken into account. First, interviews with Swedish clothing companies comprise the primary data. These interviews are with individuals that represent different medium to large Swedish clothing companies (i.e., companies with at least 50 employees (OECD, 2021)). Secondly, these companies operate combined online and offline commerce channels. Thirdly, these companies’ revenues were primarily generated from the sale of their own clothing lines, but were not exclusionary of selling other clothing brands. The research question states that this study will investigate the enabling factors digitalization poses with regards to the individual organization’s sustainability goals. This specific phrasing means that this study must eliminate any information provided that does not pertain to the specific strategic digital transformation of the organization.

6

Further delimitation comes from the individuals job roles; chiefly, that these individuals have strong knowledge of the specific sustainability objectives of the company in addition to economic and digitalization goals and efforts. For this reason, individuals have been contacted that hold positions such as: CSR Manager, Sustainability Manager, Head of Sustainability, CEO, and similar authority levels.

7

2. Theoretical Framework

_____________________________________________________________________________________

This chapter begins by presenting the implemented method for the theoretical framework. Then takes a top-down approach to explaining the transformative power digitalization has on enterprises, the apparent need for sustainability within the clothing industry, and the driving forces of changes within the industry to become more sustainable. Finally, this chapter ends with a theoretical framework summary.

2.1 Method for the Theoretical Framework

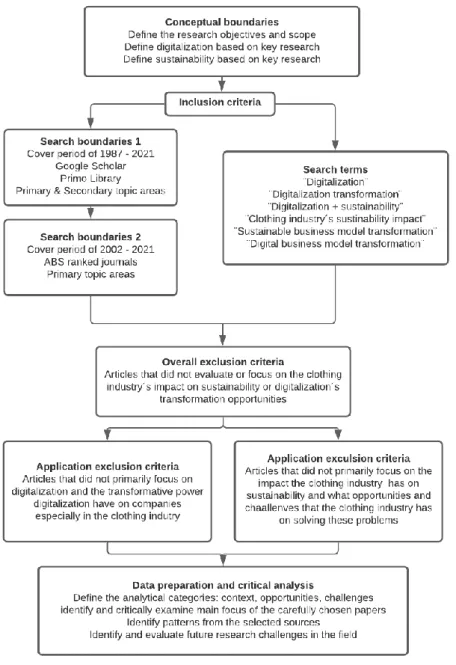

Muñoz and Cohen’s (2018) methodology was used as motivation to build a theoretical framework based on relevant sources (see figure 1). The first step comprised setting boundaries to find possibly applicable research with which to utilize. Here, six key terms were used (interchangeably) within Google Scholar and Jönköping University’s Primo library to search for literature. These terms were: ¨digitalization¨, ¨digital transformation¨, ¨sustainability¨, “clothing industry¨, “sustainable business model transformation¨, and ¨digital business model transformation¨. The motivation for selecting these terms was to adequately explore the exact interplay between digital transformation and sustainability, which is still a relatively unexplored field of research (Del Río Castro et al., 2021; Seele & Lock, 2017; Wu et al., 2018), especially within the scope of the clothing industry.

Within this first stage, the boundaries for applicable literature were kept quite broad to build a thorough historical context with which to explore these topics. Two articles, “Brundtland Report” (1987) and “A General, Yet Useful Theory of Information Systems” (1999) were selected. The boundaries were then narrowed to cover more recent publications ranging from 2002 – 2021. ABS-ranked journals were used to ensure that sources were reputable and of high esteem.

The final refinement steps included several exclusionary processes. Articles were removed from the selection that did not focus on digitalization’s transformative opportunities within the organization as highlighted by Berman (2012) and Perez (2010), facilitative power to achieve sustainability goals (Jacob, 2018), or related to the clothing

8

industry’s environmental and social impacts (MacCarthy & Javarathne, 2010). Finally, analytical categories including context, opportunities, and challenges comprised the last step of this process to explore patterns from the selected sources that could inform how the current research could contribute to future efforts.

9

2.2 Digitalization

Digitalization has been heralded as the fourth industrial revolution (Schmidt and Cohen, 2013; Schwab, 2015). However, much like the previous industrial revolutions, the long-term implications and lasting effects are not fully known. Digitalization and digital transformation refer to the transformation of business models, through core adaptations to internal processes, customer interfaces, services and products, and the integration of ICTs (Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy, 2017). This transformation affects not only organizations but society at the highest points with the implementation of ICTs (Agarwal et al., 2010; Majchrzak et al., 2016). Furthermore, included within this definition, are the changes that this digitalization and digital transformation brings about in the roles employees have the ways in which they work and the overall market sectors that exist. Vial (2019) developed the following, straightforward, conceptual definition of digitalization and digital transformation:

“a process that aims to improve an entity by triggering significant changes to its properties through combinations of information, computing, communication, and

connectivity technologies.”

The term digitalization is often used interchangeably with digitization, although it should be noted that these have different meanings (Legner et al., 2017). From a more technical perspective, digitization denotes the process by which analog signals are transferred into a digital format, specifically - binary data (Tilson et al., 2010). This process primarily is focused on the decoupling of physical transmission, formatting, and management. Whereas digitalization (and digital transformation) takes into account a more

socio-technological scope by considering how these digital technologies impact the process,

individual, organizational, and societal levels (Parviainen et al., 2017).

Digitalization’s Evolution

Digitalization has undergone its own process of evolution and integration within the general ethos. Legner et al. (2017) gave a relatively brief but comprehensive chronicle of the saga in which digital transformation has trickled into the common consciousness. Initially, the first wave consisted primarily of digitization in which information exchanged analog formats with digital ones creating much more efficient systems. These

10

information systems (IS) decreased the overall inputs required to produce a desired output (e.g., the analyzation of data) (Alter, 1999). The second phase of the digital revolution introduced the linking together of independent ISs and ICTs through the power of the internet, opening pandora’s box of possibilities. Entire industries now operate solely enabled through the power of the internet (also known as the Internet of Things (IoT)), creating disruptive potentials never before conceived (Brenner et al., 2014; Salam, 2020). Finally, the third wave in which the omnipresence of digital technologies has nearly been realized. This slightly Orwellian reality has come about through the integration of social, mobile, analytics, cloud computing, and the IoT (SMACIT) technologies (Sebastian et al., 2017) in conjunction with immense (and ever-increasing) processing capabilities, storage capacity, available bandwidth, and miniaturization of technologies. This phase is specifically important with regards to the sustainability of organizations and will be discussed in the following sections and in more detail within the conclusion.

Throughout this evolution, the utilization of technologies has also changed greatly. Fountain (2004) proposed these changes in two ways, as the implementation of: ‘objective technologies’ and ‘enacted technologies’. Objective technologies are tangible changes such as the introduction of the internet or other ICTs, whereas; enacted technologies involve the awareness, design, and application by individuals within organizations. She further claimed that the perception and situations were the primary limiting factors of these technologies. However, enacted technologies had the ability to influence the organization in a plethora of ways, a point that was widely reinforced throughout Vial (2019).

Digitalization’s Transformative Power

The introduction of new digital technologies, and general digital transformation, frequently brings large paradigm shifts to organizations (Berman, 2012; Perez, 2010). These shifts are often brought about by the fact that the ‘objective and enacted technologies’ are regularly only a small portion of the multi-faceted enigma that is digitalization (Matt et al., 2015; Vial, 2019). The remainder of this puzzle is made up of the management of these technologies as well as the subsequent adaptations to business strategies (Bharadwaj et al., 2013), procedures (Carlo et al., 2012), and even culture (Karimi & Walter, 2015). Mergel et al. (2019) postulated that, within both public and

11

private spheres, the results of these advancements meant new opportunities for value creation. This value creation is delivered in the form of innovative products and services dispensed through new networks and platforms. All of these changes could be attributed to the inherently disruptive nature of digitalization (Karimi & Walter, 2015).

Digitalization has even changed the relationships and culture between consumers and organizations (Denicolai et al., 2020 Mergel et al., 2019). Berman (2012) identified this as one of two complementary activities that firms needed to accomplish in order be successful in their digital transformation (e.g., reshaping customer value and increasing interaction and collaboration with customers). Consumer behavior and expectations have been altered by the ability to become instant experts on: market offerings, product and service comparisons, and where to make purchases (Berman, 2012; Kane, 2014). This leads to firms needing to reassess their traditionally tried-and-true customer journeys. Simultaneously enterprises have found new ways to disrupt competitive marketplaces (Yoo et al., 2010), compile and analyze large amounts of data (Loebbecke & Picot, 2015), and respond strategically to disruptions (Sebastian et al., 2017). All of these actions correlate directly back to Berman’s (2012) two success factors, specifically “reshaping

customer value propositions and transforming their operations”. In large part, SMACIT

technologies have enabled these relationship changes on both sides of the transaction (Legner et al., 2017).

Internally, digital transformations have also changed the relationships organizations have with their employees. Very often leadership within firms must be able to align their employees with a digital mindset, while concurrently maintaining the capability to respond to subsequent disruptions of digitalization within the workplace (Hansen et al., 2011). Competing within today’s marketplaces requires a level of ambidexterity from organizations, which means that employees are often required to take multi-disciplined approaches to problem-solving, frequently assuming roles traditionally outside their scope of responsibility (Vial, 2019). Furthermore, as digitalization changes the roles, tasks, and decision-making processes preformed within the workplace, employees need to be developed and trained with new skills to solve increasingly complex problems (Dremel et al., 2017; Hess et al., 2016).

12

From a sustainability perspective, digitalization has also changed the relationship that organizations have with the environment and their natural resources. Widely, academic research typically perceives the intersection of digitalization and sustainability as a win-win scenario (Del Río Castro et al., 2021). For many organizations, this has primarily come through the ability to monitor their environmental impact through Big Data analytics, increasing transparency and accountability (Seele, 2016; Seele & Lock, 2017; Zhao et al., 2017). Additionally, this improved transparency could help expand the adoption of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) performance reporting (Kiron & Unruh, 2018; Seele, 2016), reshaping the landscape for investors and consumers alike (Holst et al., 2017). Equipped by the availability of never-before conceived amounts of data, and the processing speed to analyze it, firms are able to make real-time evidence-based decisions with regards to their environmental impacts (GeSI, 2019; Tjoa & Tjoa, 2016). Additionally, AI is enabling firm’s to track qualitatively how customers feel about specific topics – and this does not necessarily omit feelings on sustainability (Zaki et al., 2021) All of this data in conjunction with digital transformation also allows improvements to resource efficiency (World Economic Forum, 2020), directly connecting to UN SDG 12 (United Nations, 2020a). These relationship alterations are all necessary in the campaign to disrupt organization resource consumption behaviors and facilitate the transition to a circular economy (Atos, 2019), while simultaneously maintaining a competitive advantage (Szalavetz, 2019).

However, the act of introducing digitalization within an organization is not serendipitous with sustainability (Fernández-Portillo et al., 2019). Even if there is a camp of academic scholars touting the win-win possibilities of sustainability facilitated by digitalization, there is another side that has raised warnings and red flags about potential hazards (Del Río Castro et al., 2021). A clear example of this comes in the increasing amount of electronic waste (e-waste). If this e-waste is not disposed of properly, the march towards a digitally transformed future could have negative effects on the health of people (United Nations, 2018) as well as on various ecosystems and biodiversity (Osburg & Lohrmann, 2017). Another current concern with digitalization is that of the energy and water consumption required (Strubell et al., 2019; Tjoa & Tjoa, 2016). Here, digitalization has been referred to as “Janus-faced” in the way that it simultaneously enables energy and low-carbon realities while yielding a huge energy demand in-and-of-themselves

13

(Rexhauser et al., 2014; Strubell et al., 2019; Bekaroo et al., 2016). Much effort will need to be given to ensure that digital solutions contribute to society’s circular economy, instead of pulling it further from it (Hilty & Aebischer, 2015; van der Velden, 2018). Both sides of this conversation highlight this area of research’s simultaneous importance and nascent nature.

In conclusion, the possibility of ICTs and digital transformation to make a net impact on an organization’s sustainability does exist (Jacob, 2018) however, it is not without serious limiting factors and potential pitfalls (Letouzé & Pendtland, 2018). For this reason, giving

the sustainable digitalization process much thought is crucial (Etzion & Aragon-Correa,

2016; van der Velden, 2018). The current model of digitalization and digital transformation does not guarantee sustainable development (Chazhaeva et al., 2019). To achieve the most desirable outcome of a sustainably digitalized future, the goals must be highly-defined (Osburg & Lohrmann, 2017), and there are many pre-requisites (Hofstetter et al., 2020; Pappas et al., 2018). van der Velden (2018) proposed that the sustainable digitalization process be re-oriented within planetary boundaries. This opens the opportunity for very much cooperation and collaboration between actors within the public and private sectors to drive policy and research for a sustainable digital revolution (Khakurel et al., 2018; Pouri & Hilty, 2018).

2.3 The impact of the clothing industry on sustainability

Defining sustainabilityThe term ¨sustainability¨ has had many different applications and has been widely used, but the publishing of the Brundtland Report in 1987 introduced the concept to the modern ethos by including a wider audience through its detailed explanation embracing the social, economic, and environmental dimensions (Kuhlman & Farrington, 2010). The Brundtland commission presented in its paper scientific evidence of the environmental degradation that exists and suggestions on how governments and individuals could take action to prevent further environmental destruction (Brundtland et al., 1987). To come up with a solution to the finite natural resources and dissuade further environmental degradation, the commission developed the remedy ¨sustainable development¨ (Kuhlman & Farrington, 2010), which refers to:

14

"development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs." (Brundtland et al., 1987, p.41).

By defining sustainable development in this manner, the United Nations was able to adapt its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by all 193 members in 2015. The aim of which was to bring this concept from an aspiration to reality by 2030 (United Nations, 2015). A subsequent result was the increased demand and focus of stakeholders, pressuring both governments and enterprises to tackle their negative social, environmental, and economic impacts. The outcome lead to organizations integrating knowledge about their ecological footprint into various aspects of their institutions (such as ESG), while simultaneously increasing their levels of transparency with customers and various stakeholders (Amran & Ooi, 2014; Heemsbergen, 2016).

To efficiently describe the impacts the clothing industry has on sustainability, the social and environmental aspects will be discussed separately. Both information regarding the international context and the Swedish context are given. This has been done to inform the reader with regards to the current research’s applicable scope. Additionally, this has been done to thoroughly highlight the environmentally and socially destructive nature of the clothing industry from the Swedish context but also on a global scale (MacCarthy & Javarathne, 2010).

Clothing industry’s environmental sustainability impact

Every human needs clothing. This necessity is so fundamental to our livelihood that it was defined as a ‘basic human need’ within Maslow’s (1943) “Hierarchy of Needs”. Unfortunately, however, this necessity of producing and selling clothing has turned into one of the world’s most destructive industries (Villemain, 2019). A large paradigm of the clothing industry is “fast fashion,” which can be defined by the imitation of more luxury trends at lower price points produced at a rapid pace (Joy et al., 2012). Despite people purchasing 60% more clothing, the portion of household income spent on clothing has been decreasing. Furthermore, the amount of time individuals wears and keep these garments has decreased by half (McKinsey & Company, 2020). This shift in consumption has caused clothing companies to re-think their production methods and introduce

faster-15

moving assortments (Nordås, 2004). Historically, clothing companies would produce four annual lines (one for each season). Yet, as a result of the fast-fashion business model, the introduction of “micro-seasonal” trends occur as often as 52 times a year (Claudio, 2007; Cline, 2013).

Concurrently, global climate temperatures have been increasing as a result of increased greenhouse gas emissions (Hansen et al., 2006), of which the fashion industry is annually accountable for approximately 10% worldwide (World Bank Group, 2019). This contribution is not static either. Expectations are that by the year 2030 the fashion industry could increase its total emissions by more than 50% (World Bank Group, 2019). One of the leading causes of these emissions is the protracted supply chain involved with the exportation and importation of clothing (Niinimäki et al., 2020). The World Integrated Trade Solution (2018) noted that Europe and central Asia are responsible for the largest proportion of these emissions, as they are the main contributors to clothing manufacturing and exporting.

Moreover, it is not simply the movement of clothing that is the problem. The physical production and life cycle of clothing and textiles also leaves behind pollutants and emissions that impact every corner of the globe (Claudio, 2007). A detail that is only reinforced by the fact that the textile industry is regarded one of the most destructive polluting industries (Niininmäki et al., 2020). These pollutions can include the chemical solutions used in the manufacturing process, the actual fabrics themselves, emissions from factories, or transportation. Additionally, during their usage phase, synthetic materials globally contribute to the release of unfathomable amounts of microplastics into the ocean when washed (Napper & Thompson, 2016). Naturally-grown materials such as cotton contribute to this problem due to the incredible amounts of water required when grown and the toxic solutions used throughout the dying processes (Chapagain et al., 2006). Globally the fashion industry accounts for 20% of the wastewater (UNEP, 2018), 24% insecticide usage, and 11% of the pesticide usage just to produce new clothing items (Radhakrishnan, 2019).

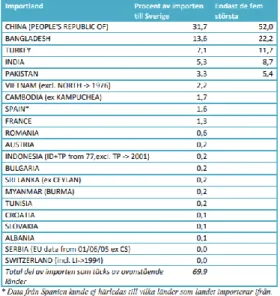

Within the Swedish clothing industry, the production phase accounted for 80% of the climate impact in 2019 (Naturvårdsverket, 2021; Sandin et al., 2019) (see Figure 2). In

16

2017, the following five countries accounted for 61% of Sweden’s clothing and textile imports: China (People’s Republic of), Bangladesh, Turkey, India, and Pakistan (Roos & Larsson, 2018) (see figure 3). Predominantly, these countries´ energy infrastructures are based on non-renewable sources (example: China 31.7% of Swedish clothing imports accounted for 95% non-renewable power as recently as 2019) (International Energy Agency, 2021; Environmental Impact Assessment, 2020) (see figure 4).

Figure 2: Climate impact from Swedes´ clothes (Sandin et al., 2019).

Figure 3: List of the largest countries of origin for Swedish textiles in 2017 (Roos &

17

Figure 4: China total primary energy consumption by fuel type, 2019 (Environmental

Impact Assessment, 2020)

Clothing industry’s social sustainability impact

Clothing production and the fashion industry operates in developing and developed nations alike. However, it is developing countries that face the largest economic, environmental, and social challenges; highlighting the importance of the implementation of sustainable industry standards. From a supply-chain research perspective, social sustainability has received the least amount of attention (Ashby et al., 2012; Crum et al., 2011; Missimer et al., 2017). Child Labor, low wages, worker safety, and health problems are just a few of the negative externalities of the clothing industry’s operations in developing countries (Pedersen & Andersen, 2015; Pedersen et al., 2018). Improved working conditions only “scratch the surface” of the many social issues that need to be addressed through legislative means (Turker & Altuntas, 2014). Nevertheless, many clothing companies try to address these problems by increasing transparency across their supply chains (Ashby et al., 2013). Unfortunately, due to the protracted and complex nature of many company’s supply chains, this is an incredibly difficult task. From the stakeholder’s perspective, this complexity and lack of transparency and clarity make understanding these supply chains difficult and time-consuming (Pedersen & Andersen, 2015).

Sweden is not innocent in contributing to this issue either. Some Swedish clothing companies have been criticized by watchdog groups, news outlets, and NGOs for their negative social and environmental impacts. Specifically, this criticization came from

18

these organizations not disclosing their subcontractors within their supply chains, nor the standards and conditions with which they operate (Fair Action, 2020). This is evidentiary of an instance where there is a lack of transparency within the Swedish clothing’s supply chain. Improving this transparency would, as previously mentioned, increase trustworthiness with customers who take sustainability into account when purchasing a product (Harris et al., 2016).

The majority of the clothing industry´s labor force (both internationally and within the Swedish context) is found in “offshore nations” (Turker & Altuntas, 2014). 70% of the industry’s labor forces consists of young and poor individuals overwhelmingly represented by women in developing countries (Allwood et al., 2006). The same study further pointed out the unfavorable working conditions of this labor force. One country, Bangladesh, has received much attention for the predatory employment structures

(Quattri & Watkins, 2019). Employees often work in factories with discriminatingly low wages and longer working days, directly exploiting an already vulnerable workforce (Turker & Altuntas, 2014). Typically, minimum wages are legally mandated within developing countries or regions, however; these workers´ wages often fall far under the living wage (Miller & Williams, 2009).

2.4 UN Sustainable Development Goals Linkage to Topic

In response to the worsening climate emergency, the United Nations adopted its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015 (United Nations, 2020a). The goal’s totality means that there are many highlighted areas that the clothing and textile industry can work towards. One of the most prominent is SDG 12: “responsible consumption and production” which directly addresses many of the aforementioned issues within the fashion industry (United Nations, 2020b). This goal basically calls for an overall decrease in humanity’s production footprint through the efficient management, usage, and reusage of resources. The only way to achieve this is through the innovation of new forms of symbiotic/cyclical market production and consumption (Gabriel & Luque, 2019). Unfortunately, the UN has pointed out that currently humanity’s overall material footprint continues to increase at an ever-alarming pace (United Nations, 2020a). Moreover goals 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 13, 16, and 17 (see figure 5) all have connections to the industry’s influences.

19

Which simultaneously serves to further highlight just how highly impactful the industry is on a global scale, and the potential opportunities that exist to make a positive impact.

Figure 5: United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations, 2020a)

van der Velden (2018) made the effort to recognize that the UN SDGs specifically mention the ICTs and their transformative potential in goals 4, 5, 9, and 17 (see appendix

3). Goal 4 (target 4b) includes training and usage of ICT in the definition of quality

education. Goal 5 (5b) distinguishes that ICTs have the potential to facilitate women’s empowerment. Target 9c of goal 9 lists access to ICTs and affordable internet as part of industry, innovation, and infrastructure development. Finally, SDG 17 (17.8) references the enabling power of technology and digital transformation, specifically facilitated through the usage of ICTs.

2.5 Sustainable Transformation of the textile industry

Consumer’s increasing demand for sustainable production

Clothing companies and fast fashion brands are not alone in sharing the blame of their environmentally and socially destructive natures - none of these trends would be possible if it wasn’t for the constant consumption of these products. Just as the brands have the responsibility to produce sustainable items, the consumer shares an equal responsibility to demand more sustainable alternatives be brought to the market (Claudio, 2007).

20

Harris et al. (2016) explored the barriers that exist between this relationship which, in large part, was manifested through the perceived disconnect and skepticism between sustainability and clothing production. A similar study from Denmark brought about many of the same conclusions, wherein respondents gave insight into the perceived contradictive nature of sustainable fashion production and consumption (Bly et al., 2015). Highlighted in both of these studies was that although some consumers do consider the sustainability of their purchases, it is often limited by their knowledge and awareness of what the different brands ‘definitions’ of sustainability (Bly et al., 2015; Cowan & Kinley, 2014; Harris et al., 2016; Radhakrishnan 2019) This issue is only further intensified by the fact that sustainability is a vague and complex term that requires a contextual scope to understand (Del Río Castro, 2021). To truly close the gap between sustainably produced clothing and the demand, consumers need to have fixed terms in how their purchases impact the planet and the individuals within the supply chain (McKinsey & Company, 2020). In the end, this level of awareness about the true levels of sustainability might be the best hope for driving clothing manufacturers to achieve sustainability (Claudio, 2007).

Sweden has developed initiatives to rectify these ambiguous effects of fashion consumption. In 2018, the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (Naturvårdsverket) worked in a tri-lateral commission (alongside the Swedish Consumer Agency (Konsumentverket) and the Swedish Chemical Agency (Kemikalieinspektionen) to increase consumers’ knowledge of various aspects of the clothing industry. These efforts included increasing awareness of the industry’s environmental and social impacts and educating consumers with information to make more informed choices, in an effort to drive demand in a more sustainable direction (Naturvårdsverket, 2021). The results of this initiative will be released in during 2021 and were not published as of the conclusion of this study (Naturvårdsverket, 2021).

In the long run, consumers have the potential to make the biggest impact by driving the market towards more sustainably produced clothes (McNeill & Moore, 2015). Clothing companies often improve their business model because they want to explore new ways of reaching their customers (Todeschini et al., 2017). Moreover, this is done in response to

21

customer’s indirect demand of new business models (McKinsey & Company, 2020) that takes the sustainable problems into account (Todeschini et al., 2017). Here opportunities present themselves such as renting clothes and reselling old clothes (McKinsey & Company, 2020). However, this does not mean that customers do not disregard the attractiveness of the clothing, which is important for companies to note to maintain a positive profit margin (Pal & Gander, 2018). Highlighting the availability of these high-quality garments from both luxury and basic brands, in the form of second-hand options, is crucial for these new business models to be successful (IVA, 2020). The appearance of this new market has led some organizations to project that the second-hand clothing markets will surpass the fast fashion market within the next decade (ThredUP, 2020).

Clothing industry’s business model transformation

Although the clothing industry worldwide is currently responsible for approximately 10% of the World’s greenhouse gas pollutions (Niinimäki et al., 2020) as well as a surplus social issue (Pedersen et al., 2018), it does not have to be this way. Many companies have taken direct action to align themselves with the UN SDGs and are actively working towards actualizing them (McNeill & Moore, 2015). For example, two of the world’s largest fashion brands have announced that they will only use sustainably produced materials by 2025 and 2030 (McKinsey & Company, 2020), which has initiated many smaller organizations to follow suit. Much of this business model development has been made on a proactive basis by organizations, but it should also be noted that an overwhelming amount is driven reactively, by increased customer awareness and in direct response to activism, such as the Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg (McKinsey & Company, 2020). However, across the clothing industry there is a variety of business models and therefore a sustainability transformation roadmap does not concretely exist; yet this poses a gap for further research to develop one (Todeschini et al., 2017). If society hopes to achieve a sustainable transition, then this gap needs to be closed and private industries must center sustainability to their actions (van Zanten & van Tulder, 2018; van der Waal & Thijssens, 2020)

Despite previous concerns of lost revenues, data has shown that companies who invest in renewing and developing their business model to align themselves more with sustainable values have proven to be both profitable and successful (in terms of sustainability)

22

(OECD, 2016). Clarkson et al. (2011) had previously postulated that companies wherein progressive efforts are made to reduce their climate impact often result in financial and leadership improvements. Furthermore, organizations’ underlying values were often reflected in their ability to change their business model, and thusly their entire organization, to become more sustainable. Pedersen & Andersen (2015) highlighted that the corporate values most synonymous for companies daring enough to undergo these transformations were ‘flexibility’ and ‘encouragement of innovation’.

2.6 Theoretical summary

As exemplified numerous times throughout this section, digitalization and digital transformation offer many new and disruptive opportunities for firms to change nearly every aspect about how they operate. Simultaneously, the clothing industry is currently contributing an overabundance of destructive and harmful environmental and social impacts. Herein, there appears to be quite a generous intersection for these aspects to create a positive relationship. Driven concurrently with new market trends and consumer demand the industry is already beginning to see a shift towards higher levels of sustainability. However, there is much left to be done. Here the theoretical framework presents gaps in spotting the concrete efforts and techniques that the clothing industry can take to become more sustainable, which is the primary purpose of this study.

23

3. Methodology and Method

_____________________________________________________________________________________

The Methodology and Method chapter begins by explaining the different methodologies adopted for this study in the sections research paradigm, approach, and design. Thereafter the Method section details the primary data collection process including: sampling approach, development of interview structure and questions, and the quote selection process. Finally, this chapter conclude with the methods and usage of primary data and ethical considerations given to the study.

3.1 Methodology

Research Paradigm

Based on the formulation of the specific research question and purpose, the interpretive paradigm has been assessed to be the most suitable. To understand the relationship between strategic digital transformation and how that is facilitating clothing companies’ sustainability goals a comprehensive perspective is required; so that the findings can be subsequently applied to real-world instances (Saldaña, 2014). Furthermore, this study must consider various aspects of natural science and social science occurrences to understand the underlying factors of the observed phenomenon (Bryman, 2016). Doing so will allow the researchers to provide a conclusion or potential theory based on the findings that have been made (MacKenzie & Knipe, 2006).

Finally, the positivist paradigm has been rejected as an option for this study because it is primarily used in quantitative studies. This is because it relies on the assumption that natural science can provide evidence from objective points of view (Ryan, 2018). For this reason, the interpretive paradigm has been judged superior in that; it will produce a more accurate result to conceptualize conclusions from the collected primary and secondary data sources.

Research Approach

An inductive qualitative research approach was chosen to answer the research question, wherein an understanding of a transformation and the “how” factors behind it (Yin, 1994).

24

In combination with the interpretive paradigm, it provides the possibility to develop a theory founded on the collection of empirical reality (through data sources such as interviews and observations) (Mackenzie & Knipe, 2006; Collins & Hussey, 2014). Additionally, the findings and observations made within this study will be examined using a top-down design to understand the larger context drawn about the studied phenomenon (Shepherd & Sutcliffe, 2011. This will result in an in-depth understanding of the phenomena, leading to developing specific conclusions from the observed data (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

On the contrary, a deductive approach applies already existing theoretical and conceptual instances to provide the researchers with a hypothesis (Byrman, 2016). This approach went against the explorative nature of this study and was therefore not chosen.

Research Design

A qualitative research design and approach will be adopted for this specific study. Frequently there is a strong correlation between the interpretive methodology and qualitative research in being able to produce results with high validity (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Moreover, Bryman (2016) stated that qualitative research is suitable when the study focuses on words and expressions of individuals instead of numerical data sets. This sentiment implies that using the quantitative research method would have proved superior had a positivism paradigm also been selected. Both quantitative and positivist research is used when collecting numerical forms of data and applying them to various contexts and was therefore not chosen for this specific study (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

Additionally, this research will adopt the grounded theory design since the study aims to develop a theory using a flexible attitude towards the collection of primary and secondary data, combined within the theoretical framework (Charmaz, 2014; Denscombe, 2014) in-service to answering the research question. Applying grounded theory allows for this study to utilize semi-structured interviews with relevant individuals to thoroughly discuss and explore the subject matter (Smith, 1995). Following this process, there will be a further transcription, organizing, and coding of data to identify potential patterns or other signaling factors for the research phenomenon. Due to the highly contextual nature and slightly subjective implications of how sustainability and digitalization can be defined,

25

secondary data will be collected from publicly available sources such as sustainability reports. Analyzing the companies’ Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) certified reports will assist in creating more reliable results when examined in combination with primary data.

3.2 Method

Primary Data Collection

Primary data will be collected, analyzed, and introduced later within the study. Mainly, primary data is defined as research that is collected directly from the source, and there are numerous different ways with which to collect this data, such as: focus groups, interviews, and observations (Collis & Hussey, 2014). This study will focus primarily on collecting its primary data through semi-structure interviews with individuals from companies that fall within the scope of this research topic.

Utilizing semi-structured interviews was chosen as an appropriate option to gain an in-depth understanding of the chosen phenomenon (Saunders et al., 2007). A pilot interview was conducted as a precautionary measure to identify and correct any errors and ambiguities with the interview process. Additionally, this was used to ensure that the interview questions were clear, understandable, and interpreted in the correct context. Thereafter, interviews were conducted with individuals representing five different companies. The qualitative methodology allowed the researchers to gain an in-depth understanding of the researched phenomenon due to its nature, even if a smaller sample size was used (Guest et al., 2013). Furthermore, the semi-structured format in combination with the qualitative nature of the study meant that respondents could give highly detailed answers on the specific research phenomena (Jack & Andersson, 2002); therefore, permitting the use of a smaller sample size to answer the research question (Marshall, 1996).

Sampling Approach

According to Collis & Hussey (2014) and Marshall (1996), the judgmental sampling approach was considered the most appropriate for this study due to it providing the researchers with the possibility to conduct non-random sampling and select candidates with the proper experience or insight that concerns the research topic. For these

26

individuals to be considered relevant for this study, they needed to fulfill two criteria. First, participants needed to work at a medium-to-large clothing company (50-250+ employees) headquartered within Sweden (OECD, 2021). A subsection of this criterion was that these companies needed to produce their own clothing and not just be an e-commerce platform for other brands. This was chosen to maintain a high level of credibility since these companies operate with different economies of scale and have more resources towards implementing digitalization efforts. The second criteria were that individuals interviewed needed to possess knowledge concerning their organization’s specific strategic decision-making processes to initiate digital transformation and sustainability goals. This was done so that data generated from these individuals would provide insight into the industry's global environmental and social impacts (MacCarthy & Javarathne, 2010) and within the Swedish context. Furthermore, the information provided by these individuals would be used to detail the opportunities and avenues these organizations could potentially take to implement digital transformation to bridge this gap (Jacob, 2018). For this reason, individuals in the roles or positions of CSR and Quality Manager, Head of CSR/Sustainability, and/or CEO were deemed to be appropriate. These individuals would be able to provide answers to the questions posed but also would be able to offer deeper insight into the thought process of the organization with regards to the research topic.

The process of contacting relevant potential interviewees started first with an evaluation process of determining various organizations' sustainability aspirations. Information was gathered from web pages, articles, and social media to select a set of potential subjects. This allowed the researchers to gather a diverse group of interviewees at potentially different phases of both their sustainable and digital transformations. The result was interviews with five different organizations (which have been quoted anonymously but can be divulged under the proper circumstances and with approval from the interviewees) and individuals in the proper positions.

Semi-Structured Interviews

When selecting an interview format, the researchers decided between structured, semi-structured, or unstructured. Because the research was to be conducted with an interpretive paradigm, an in-depth understanding of the desired phenomenon needed to be gained.

27

Additionally, this in-depth understanding would be explored through the expression of individual’s opinions, attitudes, and/or feelings. A semi-structured approach was deemed most appropriate by the researchers (Collis & Hussey, 2014). The key word of the research topic was the facilitating factors that digitalization posed to sustainability, and therefore the interviews were structured around this topic. Ultimately the semi-structured format allows for the interviewers to prepare open-ended questions to have a central theme through all of the interviews. The questions were developed and delivered in a way that directed the flow of conversation and/or touch on desired themes that were discussed. Additionally, this format allowed the researchers to have the opportunity to ask follow-up questions that may not have been thought of beforehand but about which the interviewee appeared to offer specific insight (Galletta, 2013).

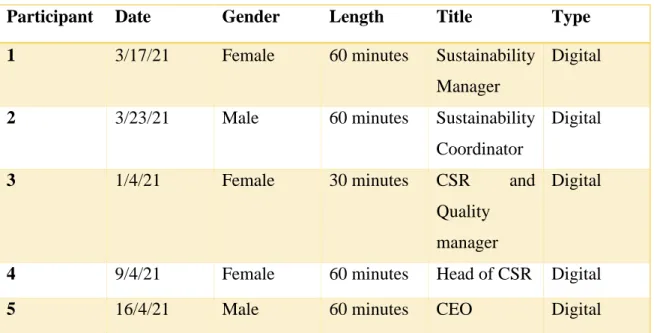

Optimally, face-to-face interviews would have been the most favourable way to perform the interviews to study the participant’s body language, emotions, and attitudes (Guest et al., 2013). However, there were two major reasons as to why this was not possible. The primary reason was the COVID-19 pandemic, which was still undergoing during the duration of this research. Folkhälsomyndigheten (2021) (The National Health Department) in Sweden strongly recommended that individuals keep at least two meters distance between one another and that gatherings be highly limited in number. Due to these restrictions, it was deemed by the researchers that organizing an appropriate place to conduct the interviews would be burdensome for both the interviewee and interviewer. Ultimately, the decision was made that the interviews would take place via Microsoft teams. An unforeseen benefit of this situation was that the individuals interviewed could book time in their schedules on shorter notice. The length of each interview was approximately 60 minutes. However, one of the interviews was closer to 30 minutes due to the participants lack of availability (see table 1).

To maintain credibility and transparency towards the participants every session started with confirming that a GDPR contract (provided one week in advance) had been agreed to and signed. Additionally, further verbal notification that the interview was to be recorded, transcribed, and analysed was also discussed, along with the purpose of the study. The intention was also expressed to the interviewees that this was to be a relatively informal conversation and that they could speak as freely as they liked. Moreover, the

28

participants were also informed that if they did not feel comfortable expressing something in English, they could do so in Swedish, as both researchers spoke Swedish. This effort was made to make sure the various participants felt comfortable and that the researchers were being as transparent as possible.

Table 1: Interviewee overview

Participant Date Gender Length Title Type

1 3/17/21 Female 60 minutes Sustainability

Manager

Digital

2 3/23/21 Male 60 minutes Sustainability

Coordinator

Digital

3 1/4/21 Female 30 minutes CSR and

Quality manager

Digital

4 9/4/21 Female 60 minutes Head of CSR Digital

5 16/4/21 Male 60 minutes CEO Digital

Interview Questions

To discover new and relevant answers to explore the research gap and purpose, open and probing questions were developed. These open questions typically started with “why, how, or what” to encourage participants to elaborate and provide detailed answers. A few examples of the types of questions devised are: “How is digitalization enabling your company to monitor its sustainability¨?; “In what ways have these changes impacted your organization’s sustainability goals?”; “Has there been unintended consequences of digitalization that your firm has encountered?”. Thereinafter, 17 open-ended questions and probing questions were developed (see appendix 1) so that the researchers could follow up on the answers given to delve deeper into the subject matter and intent of the interviewee’s organization (Guest et al., 2013). Probing questions were considered vital since they potentially lead to new insights into the given research topic.

29

The interviews were divided into four parts taking funnel approach. The first part of each was an introduction where the researchers provide information of how the interview was to be being conducted, who the researchers are, what the research is about and then the interviewee explained a little bit about his or her background, and the role he or she held at the company, in this way, it was clarified whether the participant was still relevant to the study. The second part of the interviews focused on establishing an understanding of the participants’ companies’ sustainability goals, measuring efforts, and how said organization’s viewed sustainability. Here information provided by the secondary data sources was used to tailor these questions slightly to each respondent.

The third portion of the interview focused on exploring the organizations’ digitalization processes. The questions developed were based on the established literature’s given examples of transformational powers of digitalization (Berman, 2012; Dremel et al., 2017; Hansen et al., 2011; Kane, 2014; Mergel et al., 2019; Vial, 2019). Finally, once these two foundations were established, the interviewers explore the organizations’ perceived overlap between sustainability challenges and digitalization opportunities. Here the researchers were looking for concrete examples of potential processes being used that supported or denounced the academic literature on this topic (Holst et al., 2017; Seele, 2016; Seele & Lock, 2017; Tjoa & Tjoa, 2016; Zhao et al., 2017). This final section of the interview explored this topic through the scope of how digitalization impacted the firm’s sustainability efforts on all fronts, for example: the firm’s business model (McKinsey & Company, 2020) and other sustainable challenges (Todeschini et al., 2017). Here was where the primary purpose of the study was explored. Follow up questions were given with regards to the firm’s efforts to implement sustainable digital transformation to the examples given by the interviewee (van der Velden, 2018).

Data analysis

When analyzing data throughout a qualitative study, a transcription process is crucial to understand everything the interviewee express and the underlying intentions with these meanings (Saunders et al., 2007). A thematic analysis procedure was then applied to the interview transcriptions. This method was chosen because it enables the researchers to use a flexible approach while analyzing the collected data to identify potential patterns between participants (Braun & Clarke, 2006).