MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Strategic Entrepreneurship NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 ECTS

AUTHOR: Kristina Mayr & Sophia Seidel TUTOR:Duncan Levinsohn

JÖNKÖPING May 2021

The Hidden Voices

Impact Assessment from the Perspective

of Social Enterprises

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: The Hidden Voices: Impact Assessment from the Perspective of Social Enterprises Authors: Kristina Mayr and Sophia Seidel

Tutor: Duncan Levinsohn Date: 2021-05-24

Key terms: Social Enterprise, Impact Assessment, Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis, Critical Management Studies, Purposes, Challenges, Experiences

Abstract

Background: The field of impact assessment in social enterprises is largely influenced by the top-down demands of institutions like the European Union and other resource-giving institutions. This has caused a one-sided exploration of the topic impact assessment as the perspective of the social enterprises is so far under-researched. Therefore, the purposes, challenges and other experiences the social enterprises face when assessing impact were not yet given enough attention.

Purpose: By taking a critical perspective, we seek to inspire dialogue and a change in the practical and theoretical field of impact assessment in social enterprises. We explore the enterprise’s perspective on why they assess their impact and what challenges they face. By that, their voices that have been hidden so far are raised and existing assumptions enriched by the social enterprise’s perspective.

Method: To highlight the social enterprises’ experiences when assessing impact, the qualitative research approach Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis was chosen. A purposive sampling strategy led to eight in-depth interviews with people from different German-based social enterprises. Five steps were followed to analyze the data, including a two-stage interpretation process where the researcher’s and participant’s interpretations play an essential role.

Conclusion: This thesis shows the importance of including all perspectives in a research field. Our study found that social enterprises can have different reasons to assess impact and face challenges differently than assumed with the previous research focus on the funding perspective. At the same time, they experience the process positively. A model was developed to show the interrelations of the different experiences and influencing factors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all those who accompanied us in the realization of this thesis.

In particular, we want to thank our supervisor Duncan Levinsohn, who supported us throughout our journey and inspired us with creative approaches.

We also thank the members of our seminar group (Alina Karola Neuer, Arne Ibo Stein, Eva Medvecová and Rein Te Winkel) who regularly contributed constructive feedback and enhanced our learning beyond the scope of our topic.

A special appreciation goes out to the participants of our thesis as well as the social enterprises they work for, for spending their time, openness and dedication to this project. They also enriched us with inspiring insights into their respective fields of work and life.

And, needless to say, we express our gratitude to our family and friends who have accompanied us in the process, engaged in discussions and supported us.

Jönköping International Business School, Jönköping University May 2021

Table of Contents

1 Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1

1.2 Research Problem ... 4

1.3 Research Purpose and Research Questions ... 5

2 Literature Review ... 6

2.1 Critical Management Studies ... 6

2.2 Social Enterprises ... 8

2.3 Impact and Impact Assessment ... 9

2.4 Approaches to Impact Assessment ...11

2.5 Historical Development of Impact Assessment ...13

2.5.1 Origins of Impact Assessment ...13

2.5.2 Towards a Participatory Approach of Impact Assessment ...14

2.5.3 Impact Assessment in Development Aid ...15

2.5.4 Impact Assessment in Impact Investment ...16

2.5.5 How the Development of Impact Assessment informed this Thesis ...16

2.6 Purposes of Impact Assessment ...17

2.6.1 Purposes for Impact Assessment: Third Sector Organizations ...19

2.6.2 Purposes for Impact Assessment: Social Enterprises ...19

2.6.3 Examination of Existing Literature ...20

2.7 Challenges and other Experiences of Impact Assessment ...22

2.8 Conclusion of Literature Review ...26

3 Methodology ...27 3.1 Research Approach ...27 3.2 Research Design ...28 3.2.1 Data Collection ...28 3.2.2 Data Analysis ...32 3.3 Research Quality ...34 3.4 Research Ethics ...36

4 Empirical Findings and Analysis ...38

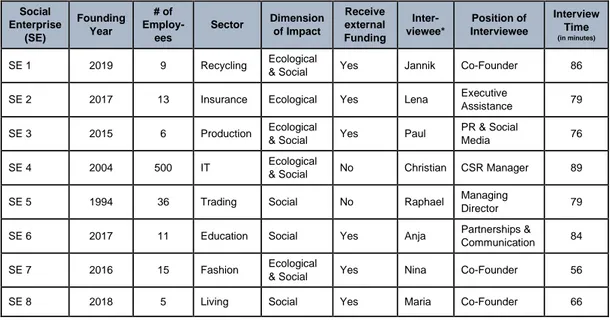

4.1 Profile of the Participants ...38

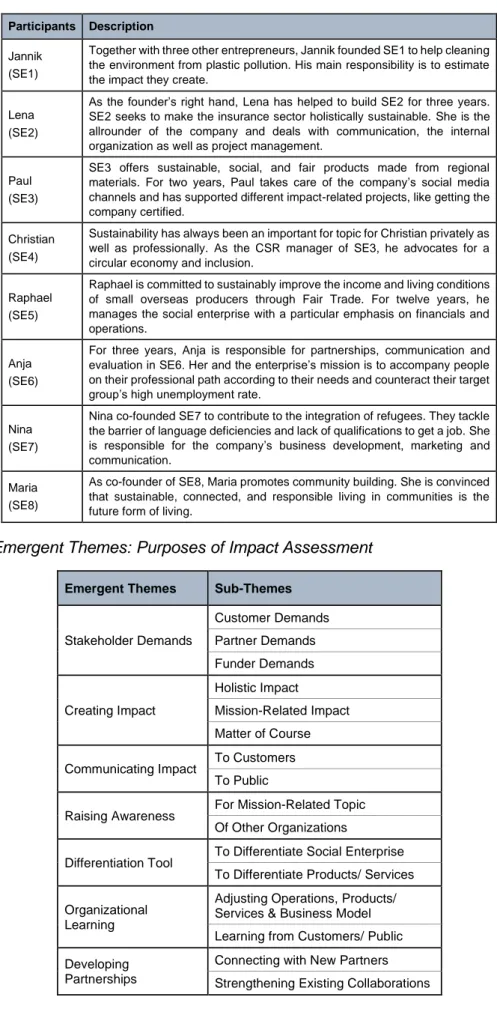

4.2 Purposes of Impact Assessment ...38

4.2.1 Empirical Findings: Purposes ...38

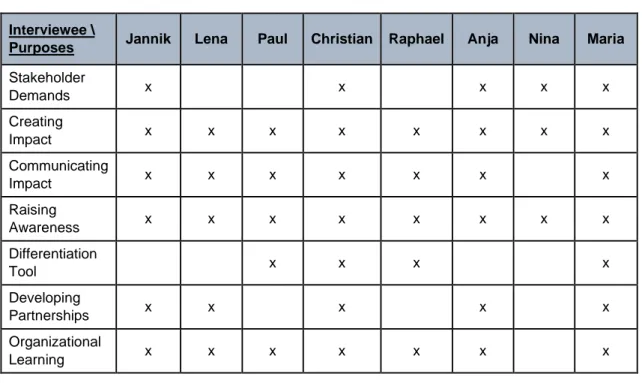

4.2.2 Analysis and Interpretation: Purposes ...44

4.3 Challenges and Other Experiences of Impact Assessment ...47

4.3.1 Empirical Findings: Challenges and Other Experiences ...48

4.3.2 Analysis and Interpretation: Challenges and Other Experiences ...58

4.4 Synthesis of the Research ...65

5 Discussion ...67 5.1 Theoretical Implications ...67 5.2 Practical Implications ...69 5.3 Limitations ...70 5.4 Future Research ...71 6 Conclusion ...73 7 References ...75

List of Figures

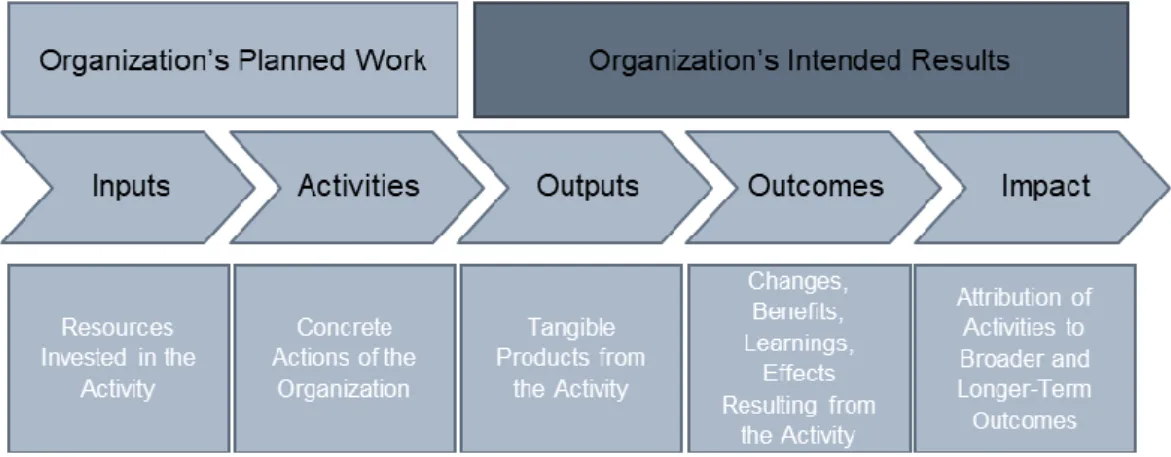

Figure 1 Logic Model (adapted from Clifford, 2014) ... 10

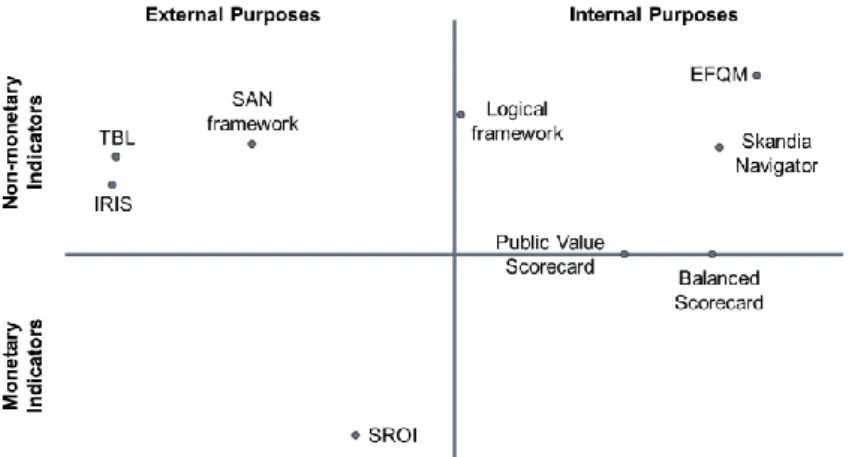

Figure 2 Classification of performance evaluation tools (based on Mouchamps, 2014, p. 734) ... 12

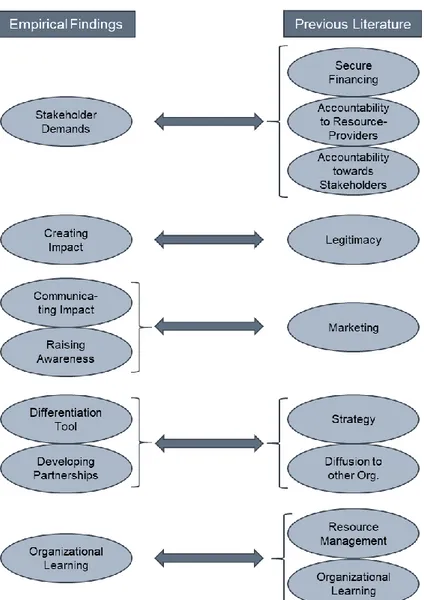

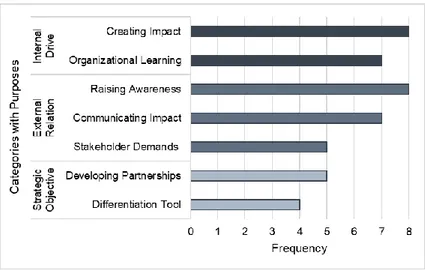

Figure 3 Emergent Themes from Empirical Findings and Previous Literature: Purposes in Impact Assessment ... 44

Figure 4 Frequency of Categorized Purposes of Impact Assessment ... 47

Figure 5 Emergent Themes from Empirical Findings and Previous Literature: Challenges and Other Experiences ... 59

Figure 6 Model of Experiences and Influencing Factors of Impact Assessment in Social Enterprises ... 66

List of Tables

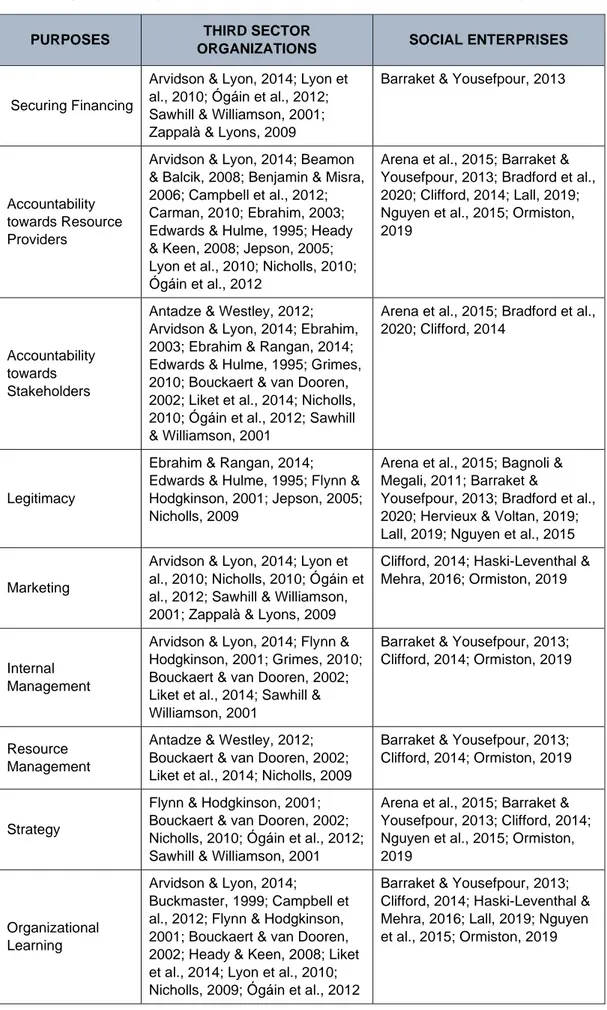

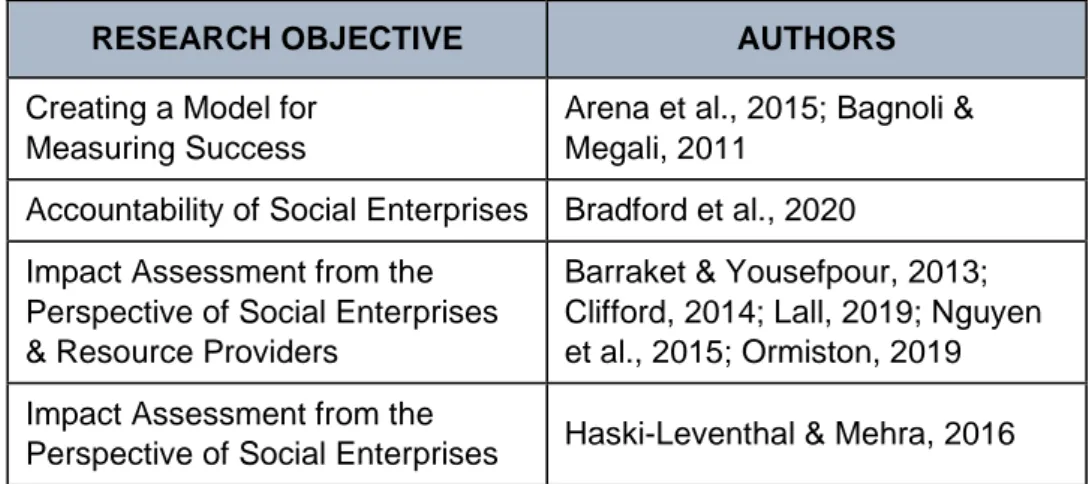

Table 1 Purposes of Impact Assessment in Third Sector and Social Enterprises ... 18Table 2 Research Objectives of Previous Studies ... 20

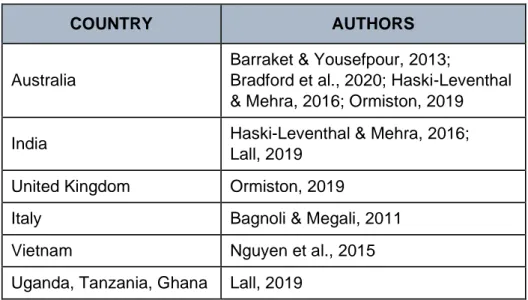

Table 3 Geographic Location of Previous Studies ... 22

Table 4 Overview of Participants ... 30

Table 5 Profile of the Participants ... 39

Table 6 Emergent Themes: Purposes of Impact Assessment ... 39

Table 7 Participants’ Allocation to Emergent Themes: Purposes ... 40

Table 8 Emergent Themes: Experiences and other Challenges of Impact Assessment ... 48

Table 9 Participants’ Allocation to Emergent Themes: Challenges and Other Experiences .. 49

Appendix

Appendix I: Interview Guideline ...82List of Abbreviations

CSR Corporate Social Responsibility CT Critical Theory

CMS Critical Management Studies e.g. For Example

EaSI Programme for Employment and Social Innovation EIA Environmental Impact Assessment

EMES The Emergence of Social Enterprise in Europe

EU European Union

EuSEF European Social Entrepreneurship Fund et al. Et alii

GECES Commission Expert Group on the Social Business Initiative GWÖ Gemeinwohl Ökonomie (‘economy for the common good’) HRM Human Resource Management

IA Impact Assessment

IAIA International Association for Impact Assessment IPA Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis n/a Not Available

NEPA National Environmental Policy Act

n.d. No Date

NGO Non-Governmental Organization NPO Non-Profit Organization

OECD Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

p. Page

SE Social Enterprise

SROI Social Return on Investment

UNECE United National Economic Commission for Europe UNEP United Nations Environment Programme

1 Introduction

According to the German Social Entrepreneurship Monitor 2021, two of three social enterprises (SEs) in Germany follow our interviewee Jannik’s call already: they assess their impact regularly (Hoffmann et al., 2020). The report relies on data from 428 SEs and suggests that impact assessment (IA) strengthens the anchoring of shared values in the organization and reduces deviation from the social mission. Hence, IA seems to be of significant importance for SEs for fulfilling their social mission (Hoffmann et al., 2020), which makes exploring the experience of SEs in doing so particularly interesting. At the same time, there is increasing pressure on SEs to demonstrate the fulfillment of their social mission (Ebrahim & Rangan, 2014). Especially funders and investors demand IA from SEs in order to be able to decide upon the most efficient investment of their financial resources (European Commission, 2020). These different interests and purposes do not seem to work well together, as commonly “there is a difference between what they [the organizations] are asked to do by stakeholders, what they say they do, and what they do in practice” (Arvidson & Lyon, 2014, p. 871).

Although IA is important for SEs for their own interest (Hoffmann et al., 2020), it is most often researched in the context of funding or investment relationships and there is a significant focus on the perspective of funders and investors (Nguyen et al., 2015; Ormiston, 2019). Therefore, the subject of IA has been explored one-sided. The question of what SEs do and experience regarding IA remains largely unanswered. This thesis aims to uncover these structures that significantly influence the research on IA to date. We will explore the purposes, challenges and experiences in measuring impact in SEs by focusing on the employees’ and founders' views.

1.1 Background

The number and influence of enterprises that combine the efficiency of traditional entrepreneurial practices with a social mission to tackle poverty, environmental issues and social injustice is growing (European Commission, 2020; Smith et al., 2013; Zahra

“[Impact assessment] must actually be a standard. So, we are not doing

anything that is incredibly fancy or anything. But if we look at the current challenges: climate crisis, plastic pollution, social upheavals … it should be a matter of course to analyze, what kind of impact do we have? Is it positive or is it negative?” – Jannik, SE1

up) as well as the provision of European funding programs (top-down) foster this growth and the emergence of new SEs (European Commission, 2020). This development attracts interest from different stakeholders such as political leaders, research institutions and public authorities (European Commission, 2020).

Although there are different definitions of what a SE is, acting economically while pursuing a social mission and aiming to have an impact is part of all of them (European Commission, 2020; Young & Lecy, 2014). An example of a SE is Discovering hands who had the core idea to improve the early detection of breast cancer. They train blind and severely visually impaired women to become tactile medical examiners in order to integrate them into the primary labor market (Hoffmann et al., 2020).

SEs are increasingly requested to prove that they achieve their particular social mission (Ebrahim & Rangan, 2014; Ormiston, 2019). The demand originates, among others, from powerful institutions like the European Union (EU) and other investors, as they aim to make social impact comparable and hence ease funding decisions (European Commission, 2020). However, since SEs operate in various fields and pursue different missions (Rawhouser et al., 2019), target different groups and have different business models (Pomerantz, 2003), it is not easy to assess, monitor and compare the impact. Therefore, different measuring tools and approaches are required to assess whether SEs manage to achieve their mission (Andersson & Ford, 2015; Hertel et al., 2020; Pomerantz, 2003).

IA is complex and SEs often face resource constraints as they operate in an environment with scarce resources (Barraket & Yousefpour, 2013). Various European funds like the

European Social Entrepreneurship Fund (EuSEFs) and the Programme for Employment and Social Innovation (EaSI) were established to support SEs. The latter alone provided

more than €86 million for investments in SEs from 2014 to 2020. The European

Commission also released approaches for IA to enable SEs to demonstrate their impact

to investors and enable fund managers to decide upon their fund distribution (Clifford, 2014), representing a top-down requirement for IA. Funders commonly believe that intensive measurement approaches with detailed, professional and complicated methods lead to a better understanding of SEs and allow accountability to receive investments (Nguyen et al., 2015). Therefore, it is no surprise that accountability towards investors and funders was the most common purpose stated (e.g., Arena et al., 2015; Barraket & Yousefpour, 2013; Lall, 2019).

These asymmetric relationships between funders and SEs warrant critical attention, as they can create pressure and inefficiencies for SEs. They may feel compelled to comply

with the demands of resource-giving stakeholders, even though they recognize that the methods are inappropriate (Nguyen et al., 2015). However, IA in SEs does not only serve to fulfill regulations and external requirements. It can also improve self-reflection of the company's operations and the achievements towards its social mission (Nicholls, 2009), which is a bottom-up approach for IA. It can increase organizational identity and staff motivation (Barraket & Yousefpour, 2013; Ormiston, 2019), provide orientation for strategy development (Arena et al., 2015) and resource allocation (Clifford, 2014). Looking at the historical development of IA, it appears that legislative requirements and powerful institutions were, from the beginning, highly involved in shaping the literature and practice of IA (Bond & Pope, 2012). However, the stakeholders, whose situation was to be improved by IA, were often not involved in the process to a sufficient extent (Vanclay, 2014). Therefore, IA practices have been criticized for different reasons, such as the limited quality and depth of analysis (Esteves et al., 2012). Many authors call for a cultural change in the field of IA and suggest a more participatory approach that involves the stakeholders more (Morgan, 2012).

Considering these historical developments and the fact that most articles on IA are related to impact investment or even written by resource-giving institutions, scientific results might be a product of ‘discursive closure’. ‘Discursive closure’ arises when potential conflicts are suppressed and certain groups are excluded from discussions. That can happen, for instance, when specific discussions are prioritized, when discussions are marginalized or when some groups are more involved in discussions than others (Alvesson & Deetz, 2020). In the case of IA, actors from the funding perspective get privileged access to discourse and the SEs' perspective is ignored to a wide extent. Therefore, IA practices and understandings are socially constructed and shaped by the relationship of SEs and their resource-providing stakeholders (Nguyen et al., 2015).

Critical reflection on how the social understandings of IA and scientific results are constructed bears the potential for emancipation and transformation to a new understanding. This critical reflection is a central element of a research path called critical

theory (CT) (Alvesson & Willmott, 1992b), which will be explained later in more detail. Critical Management Studies (CMS) applies the principles of CT to management studies

and aims to explore views of a subject that might not have been considered before (Alvesson & Deetz, 2020). The principles of CMS guide this thesis, aiming to inspire a change that benefits those that have not been considered sufficiently before in research (Fournier & Grey, 2000).

1.2 Research Problem

As of today, much of the literature about the topic of IA is written to improve funding decisions (e.g., Clifford, 2014), to compare social impact (e.g., Kroeger & Weber, 2014), or covers techniques for IA that should fulfill these aims (Nicholls, 2010). The papers that deal with the purposes and motivations of IA primarily examine the perspective of funders, investors and other resource-providing stakeholders (Barraket & Yousefpour, 2013; Nguyen et al., 2015). We found only one study that focuses on the perspective of SEs regarding the purposes of IA (Haski-Leventhal & Mehra, 2016).

What is also examined predominantly in a direct relationship with resource-giving stakeholders are the experiences and challenges of assessing impact. An example is Ormiston (2019), who looked at the relationships in an impact investment environment. In this context, demands for accounting and marketing are prominent and influential and encourage an overly positive and optimistic IA and reporting practice. This focus undermines other functions, such as organizational learning and thus a more critical IA practice is required. Beyond that, only limited attention has been paid to the purposes and experiences of IA in SEs (Ormiston, 2019).

The little research that has been conducted found that SEs need to invest disproportional high time and money to fulfill the demands from different stakeholders (Molecke & Pinkse, 2017). Although SEs often recognize that the required assessment methods are inefficient for achieving social goals, they may feel compelled to comply with them. In the resource-scarce environment of SEs (Bengo et al., 2020), this is an additional burden that hinders the realization of the social mission (Nguyen et al., 2015). It is necessary to conduct further research that sheds light on the perceived challenges of SEs in order to redress this imbalance and inefficiency.

The one-sided focus on the perspective of investors or funders suggests that the narrative on the topic of IA is limited. Researchers have not included the fundamental perspective of the actors themselves: The social enterprises. Moreover, a critical perspective demands considering the historically and socially constructed nature of IA (Alvesson & Willmott, 1992a), but so far, scholars have failed to do so. Therefore, the purposes, challenges and other experiences of IA have not yet received adequate attention from the perspective of SEs.

1.3 Research Purpose and Research Questions

This work builds on previous studies that have explored the purposes and challenges of IA in SEs (e.g. Barraket & Yousefpour, 2013; Bengo et al., 2020; Molecke & Pinkse, 2017; Nguyen et al., 2015). We distinguish and enrich those by shifting the excessive focus that has been placed on the funding perspective to the SEs’ view. We explore the different purposes of IA for SEs, study what challenges they face and how they experience IA in their everyday activities.

Moreover, in line with the critical standpoint of CMS, we intend to uncover the socially constructed nature of IA. Through carefully listening to the members of SEs and critical questioning, we discover different perspectives, significant themes, discourses and dominant practices (Alvesson & Deetz, 2020). This is important because the current debate and scientific findings on the topic are restricted. Through critical reflection about the current status, we aim to inspire dialogues and create room for transformation, both theoretically and practically (Alvesson & Willmott, 1992a).

Understanding IA and its benefits beyond serving funders’ interest is essential as it allows entrepreneurs to shift more attention to other purposes of IA. Insights into the experiences and practices of IA will be beneficial for SEs as an orientation and inspiration for their IA process. Detecting common challenges and their origins will also serve to create dialogue about the topic and facilitate change. Thus, our thesis is valuable for SEs wanting to emancipate themselves from mainly serving the demands of their funders. Raising the hidden voices of SEs serves to overcome the assumption that SEs primarily measure impact in order to satisfy stakeholder demands. When SEs and funders or investors engage in an equitable relationship, IA can be used to improve the businesses’ performance and allows both parties to achieve their shared goal of creating social impact (Nguyen et al., 2015).

Therefore, the following research questions guide our investigation to serve the purpose of this paper:

(1) What are the perceived purposes of assessing impact from the perspective of social enterprises?

(2) Which challenges do social enterprises face when assessing impact?

2 Literature Review

_____________________________________________________________________

This chapter aims to set an appropriate frame for our research topic by reviewing the existing literature about the related topics. Firstly, we introduce critical theory and the principles of critical management theory, which guide this thesis. Then the chapter elaborates on the definitions of the terms social enterprises, impact and impact assessment. Following that, the most relevant approaches to impact assessment are explained and the historical development presented. It is followed by the purposes of impact assessment that have been found so far. The chapter concludes with the challenges and other experiences of assessing impact perceived in social enterprises.

_____________________________________________________________________

2.1 Critical Management Studies

Critical Theory

A commonly stated problem with research and theories is that many aspects are seen as self-evident, natural and unproblematic even though there are alternative views about these issues and different ways of constructing situations. These assumptions avoid that the matters are questioned (Alvesson & Deetz, 2020). For this reason, critics point out that theories often have little to do with people's everyday problems and little relevance for practitioners (Kelemen & Rumens, 2008). Some researchers make a conscious choice to challenge taken-for-granted assumptions about social reality. The research following this path is called critical theory (CT). It involves questioning what is seen as given, unproblematic and natural, to trigger critical comments and inspire dialogue (Alvesson & Willmott, 1992a). CT argues that, by critical reflection, the potential for transformation is created (Alvesson & Willmott, 1992b).

A prominent example of such transformation is the relationship between sex, gender and sexuality, which has traditionally been explained and analyzed using human biology. This theoretical approach has not given room for different sexual orientations or alternative genders. However, a more critical perspective can help uncover and rethink these assumptions and recognize that the connection between sex, gender and sexuality might be culturally constructed (Kelemen & Rumens, 2008). As presented in this example, CT approaches epistemological questions and catalyzes change (Kelemen & Rumens, 2008) by directing attention to important details (Alvesson & Deetz, 2020). Through

critical reflection on how the social world and the self are constructed, the potential for emancipation can unfold (Alvesson & Willmott, 1992b).

CT is inspired by different streams, especially by the Frankfurt School of Critical Theory and Neo-Marxist views (Kelemen & Rumens, 2008). While these subgroups differ in their understanding of some aspects (Alvesson & Willmott, 1992a), scholars within CT agree that science should create value through its potential to develop beneficial conditions for human beings. Moreover, to realize the potentials of CT, social structures must change so that they support and facilitate, rather than exploit, human creativity and rationality (Alvesson & Willmott, 1992b). As a collective concept, CT incorporates different theoretical perspectives, such as feminism and gender studies, as seen in the example above and is used within organization theory and management studies. In the 1990s, the application of CT in management led to the emergence of the research body Critical

Management Studies (CMS) (Kelemen & Rumens, 2008). Critical Management Studies

CMS criticizes traditional management theory for producing oppressive management forms and argues that many management theorists fail to consider the historical and socially constructed nature of processes (Kelemen & Rumens, 2008). By doing so, established management discourse tends to be narrow and restricted and negatively affects the intellectual, practical, environmental and social spheres (Alvesson & Willmott, 1992b).

The subject matter of CMS and its research approaches vary widely (Kelemen & Rumens, 2008). Mabey et al. (1998) give an illustrative example of CMS, which deals with human resource management (HRM). He points out that much of the literature aiming to improve HRM practices has focused on the management perspective, attempting to manage and organize human resources. However, little attention has been paid to the experience of people at the receiving end. This perspective is fundamentally vital as “It is they [the employees], after all, who are expected to enthusiastically engage

with and fully participate in the HR strategies promulgated by senior management in their organizations. And it is largely upon them that such strategies stand or fall, are seen to endure and succeed or wither and fail.“ (Mabey et al., 1998, p. 7). Negative

consequences of neglecting this perspective are that the goals of HRM strategies, such as empowering employees, improving trust, or improving relationships with customers, remain widely unachieved (Mabey et al., 1998).

change in the interest of those that are underprivileged or not considered sufficiently in research (Fournier & Grey, 2000). In impact assessment (IA), this is the case with social enterprises (SEs). It is predominantly viewed from the perspective of funders and investors, while the perspective of the organizations is neglected. Investors and funders have extensive requirements for quantitative and elaborate impact reporting (Nguyen et al., 2015), but the justification of these profound demands is hardly challenged. While this might seem natural and unavoidable, it might also be the outcome of discursive domination, calling for a critical investigation (Alvesson & Deetz, 2020).

Applying the philosophy of CMS to IA, we listen to the perspective of SEs and create the potential to transform the status quo. To be able to do so, we first need to define what we understand as a SE.

2.2 Social Enterprises

The term social enterprise was introduced only about 30 years ago (European Commission, 2020; Kerlin, 2006; Nyssens et al., 2006). There is no universal definition of the term (Evers, 2001), but one can observe different streams of research in the United States (US) and Europe, respectively (Nyssens et al., 2006).

As one of the first initiatives to study SEs, the EU initiated the project Emergence of

Social Enterprise in Europe (EMES) in the late 1990s. The aim was to investigate the

development of SEs in the different member states (EMES International Research

Network, 2015). Dees and Elias (1998) describe SEs as initially being a consequence of

the funding problems of non-profit organizations (NPOs). Charitable organizations had to find innovative approaches to ensure their financial viability as collecting donations and money from grants became more difficult. Further, the public authorities of the welfare states were not able to tackle all problems that occurred, which created a need for new organizational forms to fill those gaps and contribute to the conversion of the welfare system (European Commission, 2020; Leadbeater, 1997).

With their distinct organizational characteristics, SEs can be allocated to the third sector (Defourny, 2014). The term third sector was introduced in the 1970s to refer to organizations, such as charities, NPOs, or non-governmental organizations (NGOs), that are neither part of the public nor the traditional private sector (Corry, 2010).

Dees and Elias (1998) describe a spectrum with two extremes of private enterprises. Some enterprises only seek to act in favor of society and do so by receiving donations and grants. On the other side of the spectrum, there are enterprises whose only objective is to create economic value. SEs fall somewhere in the middle of this spectrum (Dees &

Elias, 1998). There is no clear definition of SE but rather a ‘continuum of possibilities’ (Peredo & McLean, 2006, p.63). However, an essential characteristic of SEs is that they pursue a social mission by acting on the economic market. They sell products and/ or services and thereby aim to have an impact (Young & Lecy, 2014). According to Nyssens et al. (2006), the nature of the commercial operation must be linked to the social purpose. For the European dialogue, the EMES research network specified some criteria, which SEs should aim for as an ideal (Defourny, 2001). In contrast to commercial businesses, SEs may get financial support in the form of subsidies and grants. However, unlike other third sector organizations, they pursue to be profitable in the long-term in order to be financially sustainable and independent from other funding sources. By that, they are able to act autonomously and by doing so they face some degree of economic risk (Nyssens et al., 2006). Furthermore, SEs can combine monetary and non-monetary resources such as paid employees and volunteers (Defourny, 2001). As opposed to Europe, where the EMES research network defined SEs quite clearly, there is no detailed definition of the term in the US (Defourny, 2001). There, SE refers to a broader concept of aiming for a social impact using some economic practices (Kerlin, 2006; Nyssens et al., 2006).

The activities classified as SEs vary across countries, such as work integration, health-related topics, educational issues and others. Furthermore, the degree of stakeholder participation and the required extent of practicing economic activities classified as a SE are different (European Commission, 2020; Kerlin, 2006). Even within the EU, the definition of SEs varies from country to country. The various regulations and distinct legal frameworks make it challenging to find one universal definition (European Commission, 2020).

As for this thesis, we define SEs as organizations that aim to solve social issues by producing and/ or selling goods and/ or services. The organizations act responsibly not only in their production of goods and services but seek sustainability in all their activities. This is commonly called to follow a triple bottom line: they care about people, our planet and their profits (Slaper, 2011).

2.3 Impact and Impact Assessment

Impact

As mentioned above, the main characteristic of SEs is the intention to create an impact. For this reason, we need to elaborate on what impact actually is.

Researchers use different terms to describe the results of the actions of SEs, but often the terms lack precise definitions. They use social impact (Rawhouser et al., 2019; Stephan et al., 2016), social value (Hall et al., 2015; Martin & Osberg, 2007), social

outcome (Husted & De Jesus Salazar, 2006), public value (Meynhardt, 2009; Stoker,

2006), social return (Emerson, 2003), social effectiveness (Bagnoli & Megali, 2011) and

social performance (Chen & Delmas, 2011; Hertel et al., 2020).

Another possibility of approaching the definition of impact is looking at the so-called Logic

Model (or Theory of Change). It was developed by the US Agency of International

Development in the 1960s and describes the causative links between the five aspects of an intervention, being input, activities, output, outcome and impact (see Figure 1) (Ebrahim & Rangan, 2014). The model is commonly used to differentiate between the results of the actions of SEs. For example in the Social Impact Measurement report by the European Commission, the model is referred to as impact value chain (Clifford, 2014).

Figure 1 Logic Model (adapted from Clifford, 2014)

In this framework, inputs include all kinds of human and capital resources that the organization uses. Activities refer to the organization's specific actions and tasks to improve a situation or tackle an issue. Those activities result in tangible products/ services for the beneficiaries, also called outputs (Andersson & Ford, 2015; Bagnoli & Megali, 2011). The intangible effects on the lives of the beneficiaries resulting from the company’s activities are called outcomes (Bagnoli & Megali, 2011; Ebrahim & Rangan, 2014). Those can be positive and negative, intended or not, long- and short-term (Clifford, 2014; Roche, 1999). Impact implies broader and more future-oriented

outcomes affecting the beneficiaries (Clifford, 2014; Hehenberger et al., 2015) or society as a whole (Bagnoli & Megali, 2011; Ebrahim & Rangan, 2014).

Some authors do not differentiate between the terms output, outcome and impact but use them interchangeably (Clifford, 2014). While a close differentiation of the three can be beneficial in some areas, we lean our definition on Mulgan (2010), Rawhouser et al. (2019) and Stephan et al. (2016) for the context of this thesis. They describe impact as short- or long-term, non-monetary effects on the targeted individuals’ or communities’ welfare or the environment. The effects result from the implementation of projects or actions by market-based organizations, in our case SEs. Therefore, we distinguish between impact, output and outcome, but for the IA process all elements are essential as they enable SEs to contextualize impact with input factors.

Another aspect of the discussion about the term impact is the kind of mission that SEs pursue. There is an inconsistency in the existing literature whether social, environmental, or other domains are referred to (Ormiston & Castellas, 2019). Comparing impact across domains is challenging (Rawhouser et al., 2019). However, as we do not aim to compare impact but want to investigate the challenges and purposes of assessing it, we include all domains in our definition.

Impact Assessment

For the process of assessing impact, the terminology is also not standardized. The terms

assessment, measurement, evaluation, or appraisal are commonly used (Ormiston,

2019). This leads to a wide range of different combinations, such as impact

measurement (Lyon & Arvidson, 2011), outcome measurement (Rawhouser et al.,

2019), impact evaluation (Arvidson & Lyon, 2014), performance measurement (MacIndoe & Barman, 2013; Nicholls, 2010), impact reporting (Nicholls, 2009) or

performance assessment (Ebrahim & Rangan, 2014). These processes include

activities, tools, methods and standards that assess impact and aim to enable comparability across similar sectors (Ormiston, 2019). In the interest of consistency, we use the term impact assessment.

2.4 Approaches to Impact Assessment

During our review, we found a wide range of approaches used to assess the impact of SEs, some of which are more popular than others. However, none has yet become a universally recognized norm. It is unlikely that any method will ever become the golden standard as the different objectives, scales of projects, stakeholders activities require

distinct assessment methods and various ways of presenting the information (Clifford, 2014).

SEs commonly adapt performance-measuring tools for IA that were initially developed for commercial businesses. Mouchamps (2014) describes with the analogy of weighing elephants with kitchen scales. To present the most used approaches by SEs, he developed a framework in which he classifies approaches according to whether they serve external or internal purposes. Another differentiation is whether they use monetary or non-monetary indicators to assess impact (see Figure 2). However, due to the particular characteristics and the complex nature of SE’s, those traditional approaches are often not appropriate to assess their performance (Molecke & Pinkse, 2017). Therefore, new tools designed specifically for SEs need to be developed (Mouchamps, 2014).

Figure 2 Classification of performance evaluation tools (based on Mouchamps, 2014, p. 734)

The scope of this thesis does not allow us to go into detail about the approaches. However, Figure 2 shows that SEs use a wide range of different IA methods and variations thereof. They creatively find ways to give strategic attention to capturing and disclosing both social and financial value creation (Nicholls, 2009). According to Clifford (2014), however, both funders and SEs widely agree that any attempt to use pre-defined quantitative indicators to measure and capture success would be counterproductive. The reason for that is that quantitative indicators often cannot be aligned with the mission and needs of the organizations (Clifford, 2014).

To solve that issue, different associations seek to define common indicators for assessing impact and developing a shared language to communicate it (International

Federation for the Economy for the Common Good e.V., n.d.). One example is the economy for the common good movement (from German: Gemeinwohl Ökonomie (GWÖ)). However, also this approach faces criticism, for instance that there is not enough variety of indicators that show the value for the public. Moreover, it lacks legitimization by states, so its applicability is questionable (Meynhardt & Fröhlich, 2017). This confirms that also innovative approaches cannot represent the integrity of impact.

2.5 Historical Development of Impact Assessment

When conducting CMS, it is necessary to exercise sensitivity, as most critical research themes investigate hidden themes. ‘Discursive closure’ is, for instance, often an aspect of critical research. It exists whenever certain groups are not included in a discussion, for example, through marginalizing, disqualifying, or privileging certain groups and thus potential conflict is suppressed. ‘Discursive closure’ produces an apparent consensus that is actually deficient and incomplete (Alvesson & Deetz, 2020). Uncovering dissent and differing opinions usually requires historical insight into the development of what is now considered natural or consensus. When looking at history, one understands through which discussion and processes the consensus has been formed. Often, scholars fail to consider the historically constructed nature of existing processes, resulting in close-minded scientific results (Alvesson & Willmott, 1992a). The development of IA is elaborated on below to avoid such an outcome.

2.5.1 Origins of Impact Assessment

After the Second World War, the population, as well as technological and economic developments, grew explosively. Along with that came the spread of pesticide usage, oil spills and nuclear fallouts, all contributing to public concerns about the consequences on the environment and people’s health and safety (Caldwell, 1988). In 1970, the National

Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) was an innovative response from the US to these

concerns. The policy act aimed to assess planned governmental actions, such as policies and projects, regarding the effects of human activity on the biophysical and social environment. It demanded an integrative and interdisciplinary use of natural and social sciences and environmental design arts (Caldwell, 1988). The process of identifying and responding to the environmental impact of decisions gave rise to the term

environmental impact assessment (EIA) (Morgan, 1999, 2012). Bond and Pope (2012)

consider EIA as the original form of IA. Although the US government initiated it to reform policy-making, the intention was also to influence the private sector (Caldwell, 1988).

After the US introduced NEPA, other countries implemented similar legislation that was typically compatible with private and public development actions (Vanclay, 2014). Although EIA was initially supposed to cover both social and environmental impact (Esteves et al., 2012), the social aspect developed as a field on its own during the late 1970s and 1980s (Vanclay, 2014). Other IA forms have developed under the term EIA, such as social impact assessment, health impact assessment and strategic

environmental assessment (Morgan, 2012). Our understanding of IA covers all these

fields.

The formalization of IA through legal requirements contributed to spreading legislation like NEPA and related thinking patterns worldwide. Influential organizations also promoted the spread of IA practices (Bond & Pope, 2012). For instance, the United

Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) enforced IA by including it in their operations.

Also, finance corporations introduced performance standards, such as the Equator

Principles, which expanded IA standards to developing country investments (Bond &

Pope, 2012). For instance, the World Bank Group included environmental and social assessment procedures as guidelines for funding decisions in developing countries (Morgan, 2012). There, IA is mainly used in its original understanding, an ex-ante prediction of the possible social consequences of a planned intervention to allow a competent authority to decide upon the decision and conditions of project approval (Vanclay, 2014). These developments indicate that IA was initially shaped in a top-down approach originating from the public sector, influential institutions and investors.

Esteves et al. (2012) argue that IA was always subject to different interpretations, leading to a wide range of different implementation practices. Early developments of IA procedures have been criticized for different reasons, for example, that only limited resources and importance were devoted to it and therefore only a minimum of effort was put in to pass the expectations. Moreover, they state that low quality and missing depth in the analysis is an issue, for instance, when IA is pursued from secondary data about the impacted communities (Esteves et al., 2012).

2.5.2 Towards a Participatory Approach of Impact Assessment

To ensure a more profound analysis of impact, Dierkes and Antal (1986) suggest that a certain amount of public and stakeholder interest is needed so that businesses will implement significant efforts towards a comprehensive form of IA. Moreover, the spread of internet access brought increased possibilities for global communication. Thus,

affected communities had more opportunities to raise their voices and started to demand greater involvement in the IA process. Thereby they demonstrated real risks for the businesses, such as reputational damage, strikes, blockades and legal and financial consequences (Vanclay, 2014).

The issues called for a cultural change within the IA field and suggested a more participatory approach, which entails equal participation of different stakeholders (Morgan, 2012). Intending to incorporate these aspects into IA practices internationally, the International Association for Impact Assessment (IAIA) developed a new set of principles for IA from 1998 to 2003. They point out that the main challenge of developing guidelines for a participatory practice of IA is that the stakeholders whom the guidelines should address are often not involved in the development process, which is why there is a lack of identification with the principles (Vanclay, 2003). As long as sustainable decisions that involve all affected stakeholders are the goal of IA, subjectivity and interpretive distinctions are not obstacles but strengths to promote the process and create a necessary dialogue. Debates between conflicting interests promotes learning and the development of values that foster more significant personal and social responsibility (Wilkins, 2003). Such a cultural change can only occur if social and organizational learning occurs, demanding a participatory approach to IA. Therefore, stakeholders, community groups and individuals might have to use their influence to alter power relations in existing policymaking processes (Morgan, 1998).

2.5.3 Impact Assessment in Development Aid

IA plays an essential role in the philanthropic sector and development aid (Roche, 1999). Monitoring, evaluating and assessing operations has become an integral part of aid givers' and receivers' formal requirements. Here, IA serves to win funding and fulfill advocacy work to be accountable to both funders and the stakeholders that NGOs seek to support (Roche, 1999) and discuss whether foreign aid is effective (Mahembe & Odhiambo, 2020). The lack of a shared definition of impact and a standard methodology to measure it are common problems also in development aid.

Another difficulty in measuring and interpreting impact in development aid is the diversity of environments and aid projects and the complexity and interdependence of their results (Jiggins, 1995). Hence, there is a variety of approaches to assess impact. Traditionally, economic analysis is of use, but input, for instance from management and gender studies, has led to various innovations. Critical voices called for more participatory approaches to IA in development aid that involve stakeholders (Jiggins, 1995).

2.5.4 Impact Assessment in Impact Investment

Following the stock market crash of the early 2000s and the following resource constraints, social purpose organizations of any kind had to move from reporting philanthropic inputs to presenting outputs and outcomes to their grantees. Moreover, they had to engage in alternative and market-based income strategies (Nicholls, 2009), leading to a rise in enterprises that combine a social purpose with income-generating activities (Dees & Anderson, 2003). Therefore, another field of IA emerged from the philanthropy and social investment field, aiming to measure the impact of investments (Vanclay, 2014). The global financial crisis in 2008 amplified these developments, demanding that scarce funding resources are invested in projects or organizations that can demonstrate their impact (Clifford, 2014).

The pressure from regulations and investors demanded more advanced reporting practices from SEs than in traditional charities and pushed the adoption of reporting practices initially used in commercial organizations (Nicholls, 2009). Social return on

investment (SROI) is one of these practices (Vanclay, 2014), which uses financial

proxies to capture the impact for different project areas. Although some experts in the field of IA have consistently refused to assign monetary values to predict social impacts (Esteves et al., 2012), it illustrates the diversity of understandings.

The role of legislation and powerful institutions in driving the spread of IA is also evident in recent developments of IA in SEs (Bond & Pope, 2012). The European Commission

Expert Group on Social Entrepreneurship (GECES), which was created to agree on a

European methodology to measure the impact of SEs, is an example of that (Clifford, 2014).

Impact investment has been a significant driver for the theoretical and practical development of IA in SEs (Bengo et al., 2020). This is why there is much literature on impact investment and the associated methods to measure, document and compare impact in recent years (e.g., Nicholls, 2009; Ormiston, 2019; Ormiston & Seymour, 2011). However, demands from potential investors are often not in line with SE’s internal objectives of evaluating their activities (Barraket & Yousefpour, 2013) and create tension for SEs (Ebrahim, 2019). We examine this challenge in more depth in section 2.7.

2.5.5 How the Development of Impact Assessment informed this Thesis

SEs lie somewhere between businesses that only seek to make profits and organizations that only exist to create societal value and rely on donations and grants (Dees & Elias, 1998). As the literature on IA also does not draw clear boundaries on the continuum

between the disciplines, it is questionable whether the existing literature matches the needs of SEs. This confirms the need to study IA in SEs independently.

Moreover, the historical development indicates that IA has predominantly been imposed on enterprises and institutions from a top-down direction. Initially, governmental legislation required it (Caldwell, 1988). Powerful institutions such as the OECD or the

World Bank Group demand IA from companies in order to make investment decisions

(Bond & Pope, 2012; Morgan, 2012).In development aid, funders require it to allocate financial resources (Roche, 1999), which is similar to the area of impact investment, where investors decide on investments based on the assessed impact (Bengo et al., 2020). The perspective of SEs, however, is missing.

The historical development of IA is evident in both practice and theory. This confirms our critical understanding that unequal power relations significantly shape the discourse on IA as the perspective of SEs has been widely neglected. To redress this imbalance, we now provide an overview of the perceived purposes and challenges of IA drawn from the existing literature, to later discuss them in context with our own research.

2.6 Purposes of Impact Assessment

After elaborating on the history of IA, the question arises why enterprises bother to assess their impact in the first place. As our research aims to study SEs, we first specifically looked for articles exploring their purposes and assigned special attention to those findings. However, we only identified nine articles. As explained earlier, SEs can be assigned to the third sector. That is why we then also examined papers covering the purposes of IA in third sector organizations, as those are potentially relevant for SEs as well.

We summarized the purposes identified for both third sector organizations and SEs into higher-level themes, as shown in Table 1 with the corresponding articles. The following sections give a more detailed explanation of the themes.

Table 1 Purposes of Impact Assessment in Third Sector and Social Enterprises

PURPOSES THIRD SECTOR

ORGANIZATIONS SOCIAL ENTERPRISES

Securing Financing

Arvidson & Lyon, 2014; Lyon et al., 2010; Ógáin et al., 2012; Sawhill & Williamson, 2001; Zappalà & Lyons, 2009

Barraket & Yousefpour, 2013

Accountability towards Resource Providers

Arvidson & Lyon, 2014; Beamon & Balcik, 2008; Benjamin & Misra, 2006; Campbell et al., 2012; Carman, 2010; Ebrahim, 2003; Edwards & Hulme, 1995; Heady & Keen, 2008; Jepson, 2005; Lyon et al., 2010; Nicholls, 2010; Ógáin et al., 2012

Arena et al., 2015; Barraket & Yousefpour, 2013; Bradford et al., 2020; Clifford, 2014; Lall, 2019; Nguyen et al., 2015; Ormiston, 2019

Accountability towards Stakeholders

Antadze & Westley, 2012; Arvidson & Lyon, 2014; Ebrahim, 2003; Ebrahim & Rangan, 2014; Edwards & Hulme, 1995; Grimes, 2010; Bouckaert & van Dooren, 2002; Liket et al., 2014; Nicholls, 2010; Ógáin et al., 2012; Sawhill & Williamson, 2001

Arena et al., 2015; Bradford et al., 2020; Clifford, 2014

Legitimacy

Ebrahim & Rangan, 2014; Edwards & Hulme, 1995; Flynn & Hodgkinson, 2001; Jepson, 2005; Nicholls, 2009

Arena et al., 2015; Bagnoli & Megali, 2011; Barraket &

Yousefpour, 2013; Bradford et al., 2020; Hervieux & Voltan, 2019; Lall, 2019; Nguyen et al., 2015

Marketing

Arvidson & Lyon, 2014; Lyon et al., 2010; Nicholls, 2010; Ógáin et al., 2012; Sawhill & Williamson, 2001; Zappalà & Lyons, 2009

Clifford, 2014; Haski-Leventhal & Mehra, 2016; Ormiston, 2019

Internal Management

Arvidson & Lyon, 2014; Flynn & Hodgkinson, 2001; Grimes, 2010; Bouckaert & van Dooren, 2002; Liket et al., 2014; Sawhill & Williamson, 2001

Barraket & Yousefpour, 2013; Clifford, 2014; Ormiston, 2019

Resource Management

Antadze & Westley, 2012; Bouckaert & van Dooren, 2002; Liket et al., 2014; Nicholls, 2009

Barraket & Yousefpour, 2013; Clifford, 2014; Ormiston, 2019

Strategy

Flynn & Hodgkinson, 2001; Bouckaert & van Dooren, 2002; Nicholls, 2010; Ógáin et al., 2012; Sawhill & Williamson, 2001

Arena et al., 2015; Barraket & Yousefpour, 2013; Clifford, 2014; Nguyen et al., 2015; Ormiston, 2019

Organizational Learning

Arvidson & Lyon, 2014;

Buckmaster, 1999; Campbell et al., 2012; Flynn & Hodgkinson, 2001; Bouckaert & van Dooren, 2002; Heady & Keen, 2008; Liket et al., 2014; Lyon et al., 2010; Nicholls, 2009; Ógáin et al., 2012

Barraket & Yousefpour, 2013; Clifford, 2014; Haski-Leventhal & Mehra, 2016; Lall, 2019; Nguyen et al., 2015; Ormiston, 2019

2.6.1 Purposes for Impact Assessment: Third Sector Organizations

Some authors identify IA as a means to receive funding (e.g., Lyon et al., 2010). They found that some grant givers require the organizations to fulfill certain criteria when applying for funds and IA enables the organization to show evidence. Further, it proved to be a way to attract other donors. Following that, it is not surprising that being accountable towards different stakeholders is identified by most of the studies as a reason for IA. On the one hand, organizations need to justify their activities towards their resource providers like funders and/ or grant givers (e.g., Arvidson & Lyon, 2014). Those want to make sure that they have chosen the right organization to support and therefore require them to deliver reports, or the like, to give proof of their activities.

On the other hand, the organizations are also accountable to other stakeholders such as beneficiaries, employees, managers, board members, supporters and the public (e.g., Ebrahim & Rangan, 2014). The stakeholders expect the SEs to show what they are doing and to what extent they achieve their mission. Therefore, measuring their impact enables organizations to justify and legitimate their operations by disclosing the results (e.g., Flynn & Hodgkinson, 2001). Another theme that we found is to use IA to support marketing activities (e.g., Nicholls, 2010). By demonstrating their impact, organizations can increase their credibility and publicity and thereby attract new customers.

When looking at the function of IA as a means for internal management, showing the impact created can increase staff motivation and strengthen the organizational identity (e.g., Bouckaert & van Dooren, 2002). Further, the collected data helps executives to manage their resources (e.g., Antadze & Westley, 2012) and gives orientation when determining a strategic and long-term plan (e.g., Flynn & Hodgkinson, 2001). Literature also suggests that measuring impact can help third sector organizations reflect on their operations and thereby improve the quality of their activities, services and programs (e.g., Heady & Keen, 2008).

2.6.2 Purposes for Impact Assessment: Social Enterprises

As mentioned earlier, there has only been limited research looking at IA purposes in the context of SEs (Ormiston, 2019). As elaborated on in chapter 2.2, SEs can receive external funding but seek to be profitable and finance themselves in the long term (Defourny, 2001). That might be a reason why the purpose of assessing impact to secure financial support seems to be less prevalent in studies on SEs as it is in the third sector in general. Surprisingly, however, most authors point out that the enterprises use IA to prove accountability, especially towards funders, investors and other stakeholders (e.g.,

Clifford, 2014). It seems that SEs are still quite dependent on their stakeholders. Due to those dominant external demands, it is not surprising that the purpose of gaining legitimacy through IA is evident in most studies (e.g., Hervieux & Voltan, 2019).

As SEs act on the economic market by offering goods and/ or services (Young & Lecy, 2014), it is expectable that they use the IA results to demonstrate quality and advertise their products/ services (e.g., Haski-Leventhal & Mehra, 2016). Likewise, IA results can motivate staff (e.g., Ormiston, 2019) and help to manage resources (e.g., Clifford 2014). It is also used as a strategic tool to benchmark and make decisions (e.g., Arena et al., 2015). What was mentioned by the majority of authors is the purpose of learning within the organization through IA (e.g., Lall, 2019). IA enables enterprises to engage with their target group, define their needs and thereby improve and scale their impact. This shows that they want to do their best to follow their main mission: to act in favor of society (Young & Lecy, 2014).

2.6.3 Examination of Existing Literature

When examining the existing literature, we noticed that it is worth looking at the primary objectives of the studies that identified purposes of IA for SEs. Table 2 gives an overview of that: The left column shows the studies’ focus and the right one the authors of the articles.

Table 2 Research Objectives of Previous Studies

The papers of Arena et al. (2015) and Bagnoli and Megali (2011) aim to create a model to measure the success of SEs. In their study, they identify some IA purposes, but as it was not the main objective of their research, those are rather a side finding. In contrast

RESEARCH OBJECTIVE AUTHORS

Creating a Model for Measuring Success

Arena et al., 2015; Bagnoli & Megali, 2011

Accountability of Social Enterprises Bradford et al., 2020 Impact Assessment from the

Perspective of Social Enterprises & Resource Providers

Barraket & Yousefpour, 2013; Clifford, 2014; Lall, 2019; Nguyen et al., 2015; Ormiston, 2019 Impact Assessment from the

to that, Bradford et al. (2020) explored the aspect of being accountable and, therefore, did not discover any additional purposes for assessing SEs' impact.

Interestingly, five out of the nine papers reviewed include the viewpoint of investors, funders or resource providers in general (e.g., Barraket & Yousefpour, 2013). The

European Commission report emphasizes the aim to help fund managers, investors and

grant givers to make better decisions (Clifford, 2014). Therefore, it is not surprising that when looking at the purposes of IA, there is a strong focus on the perspective of the financiers and why IA is crucial to them, while only a couple of points from the SEs’ perspective are mentioned. The other authors all conducted qualitative studies interviewing founders or employees from SEs and people from the funding organization, investors or similar (e.g., Ormiston, 2019). Lall (2019), Nguyen et al. (2015) and Ormiston (2019) specifically articulate their focus on the relationships between SEs with funding institutions. Therefore, they have explored how the purposes of IA are experienced in this specific context. Only the study of Haski-Leventhal and Mehra (2016) focuses solely on the perspective of the SEs and thereby allows more independent results.

The extensive focus on the perspective of the resource providers could be the reason for finding similar themes of purposes of IA for SEs as for the third sector in general. We assume that, by focusing on the perspective of resource providers, the SEs’ perspective and their distinct purposes for IA are undermined. This calls for an independent examination of SEs' perspectives without considering the funders’ views.

What also stands out is the geographical location of the conducted studies (see Table

3). Australia is a frequently researched field, as our review shows four studies focusing

on this context (e.g., Bradford et al., 2020). Other than that, SEs in India (e.g., Lall, 2019), United Kingdom (Ormiston, 2019), Italy (Bagnoli & Megali, 2011) and Vietnam (Nguyen et al., 2015) have been investigated. Lastly, Lall (2019) also looked at SEs in Uganda, Tanzania and Ghana. So far, there have been not many studies examining the purposes of IA for SEs in the European context. The definition of SEs and the level of stakeholder participation differs globally (Kerlin, 2006) and different corporate cultures and legal frameworks exist even within Europe (European Commission, 2020). That is why it is valuable to investigate the perspectives of SEs based in other locations than the ones mentioned above.

Table 3 Geographic Location of Previous Studies

2.7 Challenges and other Experiences of Impact Assessment

It is not only important to look at why SEs measure their impact but also how they experience the IA process. Challenges provide insights into the experiences of SEs. Since there is little research on the experiences of assessing impact SEs, the following sections aim to elaborate on challenges based on existing literature and extract other experiences when available. This is in line with our philosophy CMS, which aims to discover and acknowledge contradictions and clashing power relations that influence organizational practices (Spicer et al., 2009). Therefore, patterns indicating towards discourses and dominant practices are of significant interest and attention is given to situations, ideas and practices that imply repression or ‘discursive closure’ (Alvesson and Deetz, 2020). It has to be noted that, similar to the purpose section, not all of the literature reviewed for this chapter deals explicitly with SEs. In some cases, it refers to the third sector in general. Moreover, the perspective of funders and investors is very prominent in the papers discussed.

Choosing a Method

SEs and their employees face multiple challenges when assessing impact. While there are various methods to assess impact, the lack of standards makes it challenging (Molecke, 2017) as the right tool depends on the context of the SE (Willems, 2014). Organizations struggle to navigate and decide when facing diverse methods, metrics, frameworks and processes (Bengo et al., 2020). As different stakeholders have different requirements for IA and reporting, SEs are reluctant to invest in implementing a particular

COUNTRY AUTHORS

Australia

Barraket & Yousefpour, 2013;

Bradford et al., 2020; Haski-Leventhal & Mehra, 2016; Ormiston, 2019 India Haski-Leventhal & Mehra, 2016;

Lall, 2019 United Kingdom Ormiston, 2019

Italy Bagnoli & Megali, 2011

Vietnam Nguyen et al., 2015

process (Clifford, 2014). Frequently, the implementation process also requires specific data that is typically not available in a consistent form. Therefore, deciding on an IA process in dynamically changing organizations is challenging (Barraket & Yousefpur, 2013).

Complexity of Impact Assessment

Another challenge lies in the complexity of operationalizing impact due to various reasons (Barraket & Yousefpur, 2013). SEs most often do not operate in narrow and well-defined commercial spaces, which target a specific market. Instead, they work across a spectrum of heterogeneous activities, engage with many sectors of society and different resource inputs and generate multiple, non-measurable outputs (Nicholls, 2009). No method can capture all impacts fairly or objectively (Clifford, 2014) and often it is challenging for SEs to articulate desired outcomes (Hervieux & Voltan, 2019). Social metrics are often abstract, impractical and difficult to implement (Ormiston, 2011). It could be argued that one life being saved by a SE is priceless (Nicholls, 2009). This illustrates why impact is sometimes described as unmeasurable (Molecke, 2017). Contributing to this is the problem of timely reporting for long-term impact (Nicholls, 2009; Hervieux & Voltan, 2009). For example, the success of a criminal's rehabilitation program can only be observed after several years (Nicholls, 2009). However, long-term outcomes have to be assessed in shorter terms when using certain methods (Barraket & Yousefpur, 2013).

It is also often difficult to establish a clear link between cause and effect (Hervieux & Voltan, 2019). Describing an impact as the result of a specific initiative is especially challenging when there are complex input factors such as different financial resources, volunteer work and organizational efforts (Nicholls, 2010). Exogenous factors outside the enterprise’s control may neutralize the efforts of a specific intervention, making it even harder to assign a specific intervention to an impact (Molecke, 2017). Because of their abstract and immeasurable nature, social metrics are sometimes ignored in contrast to economic and financial metrics, as those offer a level of comparability. Therefore, there is a tendency to use quantitative and growth-based measures originating from the difficulty for SEs to express the achievement of a social mission (Ormiston, 2011). These quantitative indicators cannot express the qualitative backgrounds and undervalue the qualitative nature of impact (Clifford, 2014).

Resource Constraints

How to do IA is a matter of choice, but also a matter of resources. SEs experience time constraints and work commitments hindering IA and evaluation (Barraket & Yousefpur, 2013). It requires specialized data and expertise to choose a suitable method and customizing it to the SE’s needs, which is costly and time-consuming. This is particularly relevant as SEs often operate in a resource-scarce environment (Bengo et al., 2019). Following the IA process in five SEs, Barraket and Yousefpur (2013) identified staff commitment, limited staff skills and experience and staff turnover as barriers. They found that sometimes staff turnover even led to the loss of organizational knowledge. IA is often perceived as not proportional to the efforts considering the extensive resources required (Clifford, 2014; Molecke, 2017).

Competing Demands and Experience of Power Relations

SEs experience rising demands for IA as the competition around resources in their environment increases (Arvidson & Lyon, 2014). The demands from stakeholders are different and sometimes competing with the organization’s perceived benefits of IA, such as organizational learning and performance increase (Barraket & Yousefpour, 2013). Funders, for instance, seek information that is easily transferable and interpretable, mainly being quantitative, while other stakeholders demand rich and experiential information, mostly in qualitative nature (Molecke & Pinkse, 2017). As demands for accountability encourage a positive and optimistic IA and reporting practice, internal demands of a more critical IA practice might be undermined and organizational learning hindered (Ormiston, 2019).

Often, it is difficult for SEs to fulfill the reporting requirements of their funders and conflicts between the expectations of the funders and the demands of other stakeholders arise (Ebrahim, 2019). From resource-providing stakeholders, requests for IA affect the SE in a top-down approach, while internal drivers work in a bottom-up approach (Ebrahim, 2003). This is a challenge for SEs, as frequently, the top-down demands overshadow the bottom-up drivers (Carnochan et al., 2014), resulting in asymmetries of power based on resources and access to information (Arvidson and Lyon, 2014).

As donors often focus on expanding and scaling organizational reach, these goals are commonly not aligned with the enterprise’s social mission. Adjusting to quantitative measures, the enterprise moves further away from achieving the social value it aims to follow (Ormiston, 2011). This imposes the wrong incentives on SEs, which are neither relevant for future success nor help with decision-making (Molecke, 2017). Ormiston