STOCKHOLM UNIVERSITY Department of Economic History and International Relations

International Relations III Bachelor thesis

Spring of 2020

A Healthy Performance in Times of a Pandemic

A review of the World Health Organization’s policy performance in times of global public health crises

Student: Lova Loinder Arvidsson Supervisor: Elisabeth Corell

Abstract

This paper explores WHO’s response during the COVID-19 pandemic and compares it to its response during the SARS epidemic in 2003. This is done by examining the organization’s performance through a policy output approach and theoretical perspectives of effectiveness and performance theories. The policy output approach offers an operational model that suggests studying five variables of output applied to the policy documents published by the organization. The results show that WHO has increased its performance and productivity since SARS 2003 which might indicate that the effectiveness of the organization could have increased along with it. However, in order to ultimately establish effectiveness, external factors such as compliance of member states and domestic politics needs to be considered in future studies. This study contributes to the understanding of WHO’s performance in times of crisis and can be used as background for further research on effectiveness.

Table of contents

Abstract 2

Table of contents 3

Tables and figures 4

1 Introduction 5

1.1 Aim and research question 6

1.2 Making use of effectiveness and performance approaches 6

1.3 Previous research 7

1.4 Comparative case study analysis 7

1.5 Empirical material 7

1.6 Delimitations and limitations 7

1.7 Disposition 8

2 Theory 9

2.1 Establishing effectiveness and good performance 9

2.2 IO Performance 10

2.3 Theoretical limitations 12

2.4 Previous Research 13

3 Methodology 19

3.1 Most similar cases 19

3.2 The policy output approach 20

3.3 Sampling strategy 21

3.4 Content analysis 23

3.5 Conducting the literature review 25

3.6 Empirical material 25

3.7 Delimitations and limitations 26

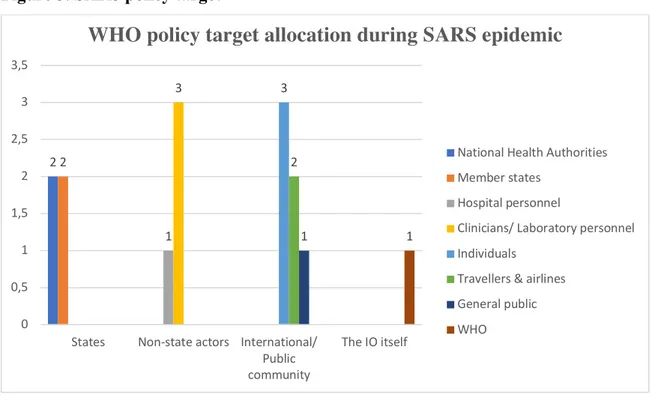

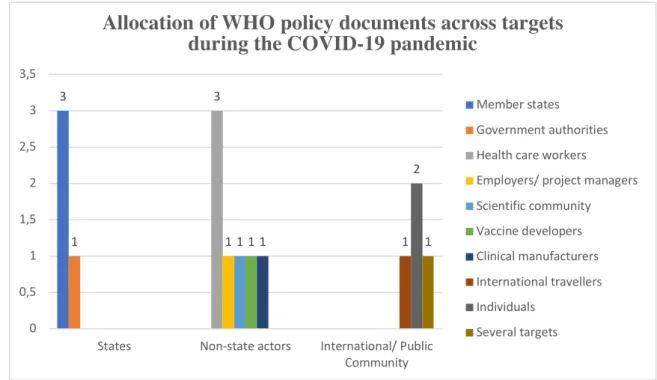

4 Results 28 4.1 Policy volume 28 4.2 Policy orientation 29 4.3 Policy instrument 31 4.4 Policy target 32 4.5 Cross-case analysis 36 5 Analysis 39 5.1 Policy volume 39 5.2 Policy orientation 39 5.3 Policy instrument 41 5.4 Policy target 42

5.5 Summary of main findings 43

6 Conclusions 45

6.1 Concluding remarks 45

6.2 Suggestions for further research 45

7 References 47

Tables and figures

Tables

Table 1. The five subcategories of the policy output approach 11

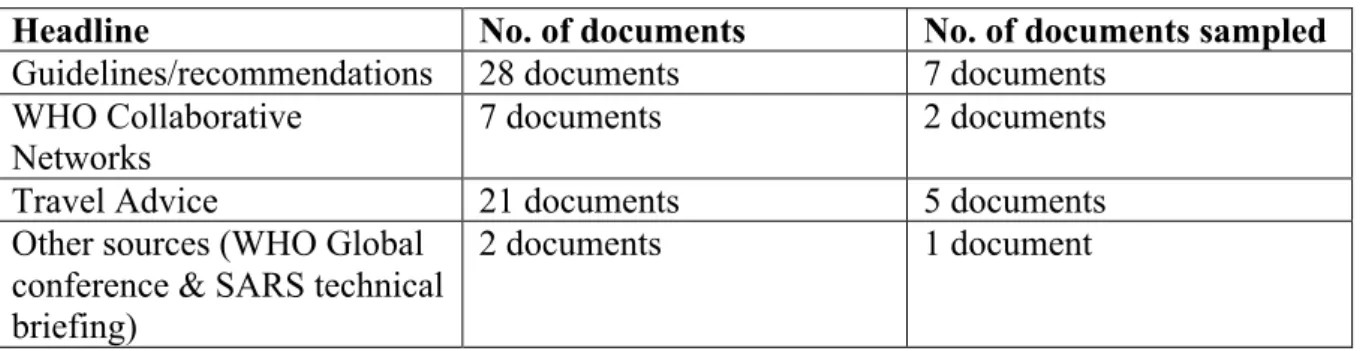

Table 2. Sampling strategy SARS 22

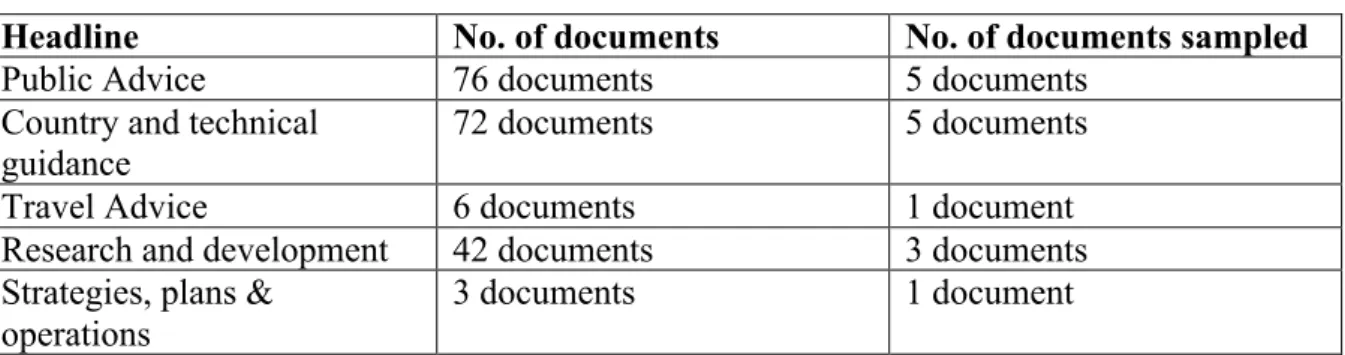

Table 3. Sampling strategy COVID-19 23

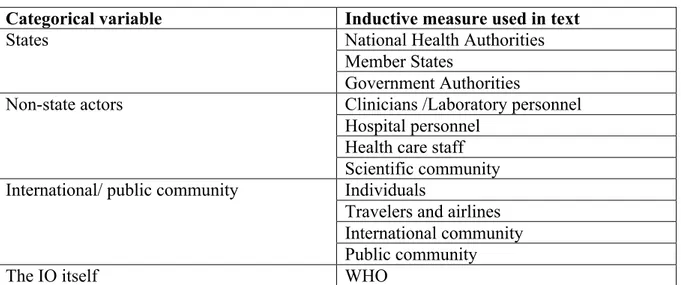

Table 4. Policy target measures 24

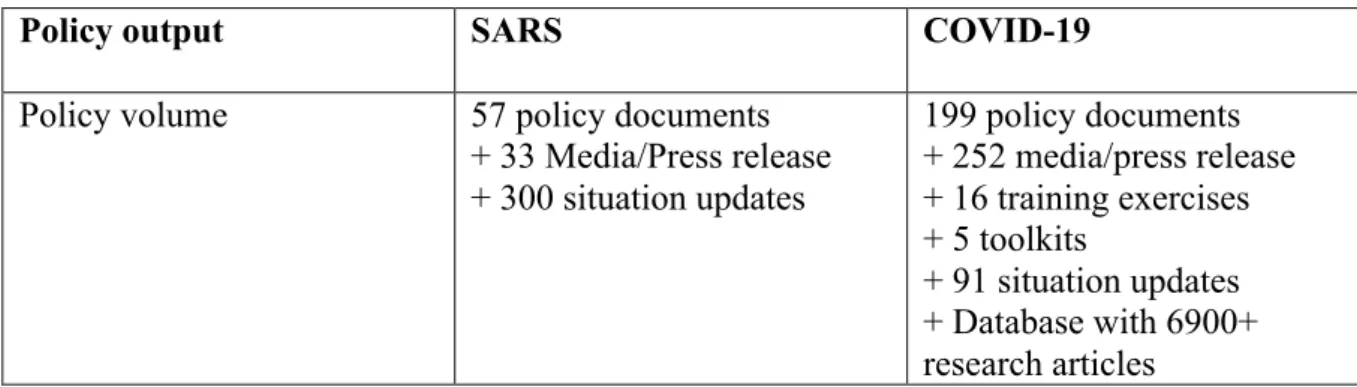

Table 5. Policy volume 28

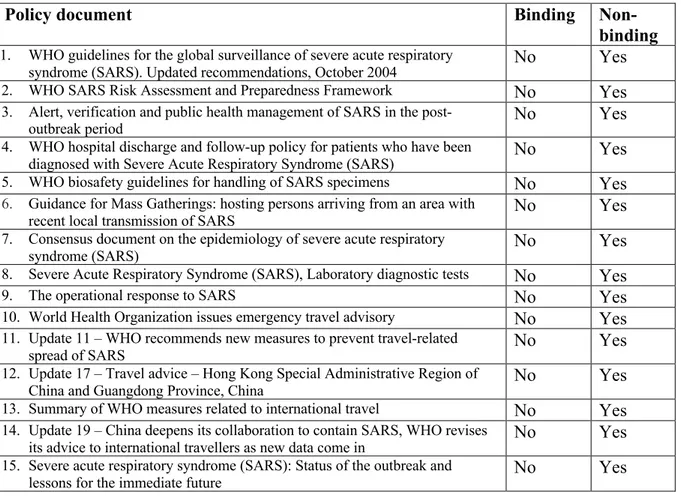

Table 6. SARS policy instrument 31

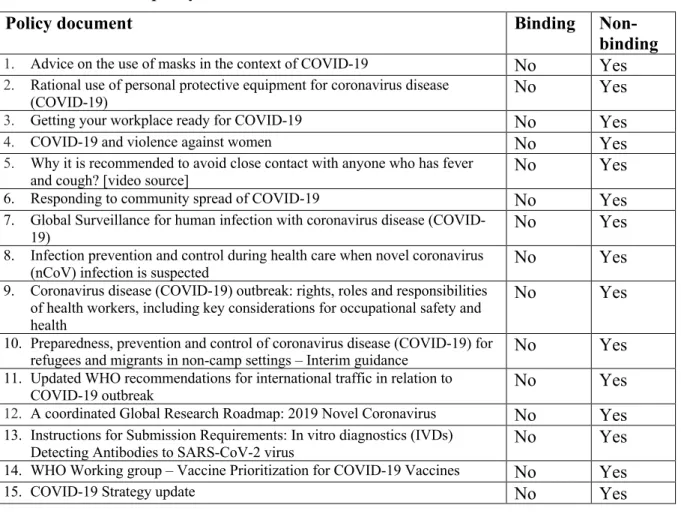

Table 7. COVID-19 policy instrument 32

Table 8. SARS policy targets 33

Table 9. COVID-19 policy target 35

Table 10. Comparison policy orientation 37

Table 11. Comparison of policy targets 38

Figures

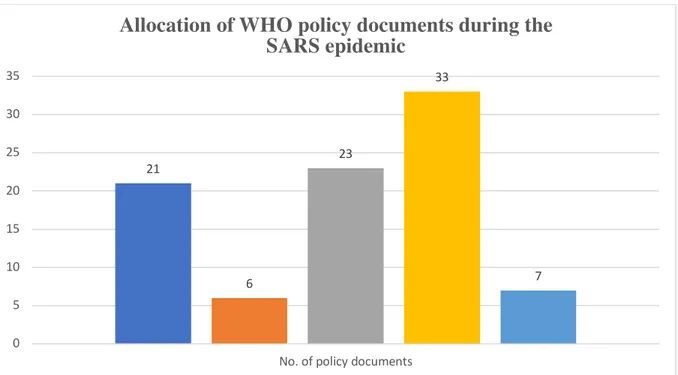

Figure 1. SARS policy orientation 29

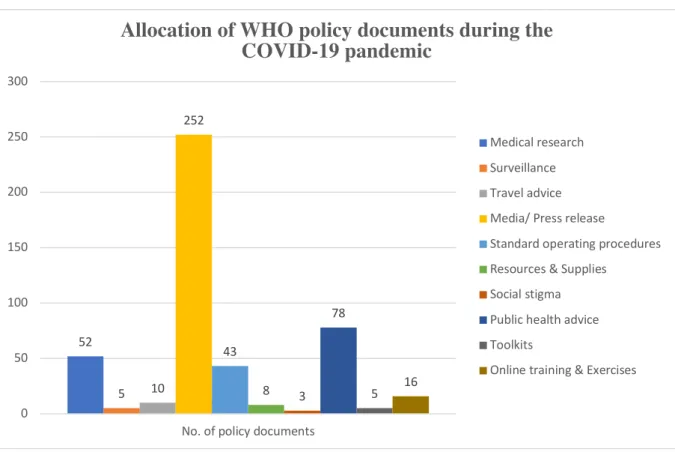

Figure 2. COVID-19 policy orientation 30

Figure 3. SARS policy target 34

1 Introduction

“I have been instructing my administration to halt funding of the World Health Organization while a review is conducted to assess the World Health Organization role in severely mismanaging and covering up the spread of the coronavirus” – President Trump (NBC News,

2020).

On the 15th of April 2020, The United States of America withdrew its funding from the World

Health Organization (WHO), and President Trump claimed that the organization was not fast or transparent enough in its response regarding the spread of the coronavirus (NBC News, 2020). In the light of the current pandemic, considerable pressure is put on WHO to achieve results and prevent the disease from spreading. The Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has thus far affected all regions of the world with 5,491,678 confirmed cases and 349,190 deaths as of May 28th.

What started out as the death of one person in Wuhan, China in December 2019, has become a worldwide pandemic causing economic, social and political turbulence as it

spreads. The world has seen thousands die and more to come as we are still seeking for medical and political ways out of this nightmare. The ongoing pandemic is raising questions whether the global health governance is able to handle crises on this scale and putting

pressure on leading agencies to react and respond efficiently. WHO has received considerable critique regarding their response to previous epidemics and its relevance as a global health governor has been questioned repeatedly (McInnes, 2015; Kamradt-Scott, 2016; Garret, 2007). During the Ebola outbreak 2014, the late response of the WHO led to the outbreak spiraling out of control and ended up in several thousand people dead. The SARS outbreak in 2003 challenged the WHO to reform and review its response in times of crises (Kamradt-Scott, 2016).

In times like this, the capacity of international cooperation and global governance is tested as we try to find a solution to a common problem. International organizations (IOs) have long been a topic of research and their contributions to global governance is

unquestionable. IOs enable coordination of international cooperation, provide possibilities for small states uncapable to act themselves and work as a stabilizer for global governance. However, despite the possibilities IOs create, they are also faced with several challenges and are forced to be held accountable for the actions of nation states. Considering these

challenges, IOs still play a great role in setting agenda, creating and upholding international norms as well as form international cooperation.

Nevertheless, the critique posed must still be taken seriously and WHO, being the leading agency in global health, has to be examined regarding its role and strategies used. The global pandemic leads to questions regarding the performance and efficiency of WHO

actions. Thus, this essay examines the effectiveness and performance of WHO in order to provide insight in the global governance response to public health crises. Consequently, this is important to the study of IR since COVID-19 is a global pandemic that challenges

international cooperation and questions the role of IOs.

In order to evaluate the role of WHO in global health governance I examine the performance during this pandemic and compare it to the response during SARS 2003.

1.1 Aim and research question

The aim of this essay is to explore whether IOs actually contribute to international

cooperation. In order to do so I choose to examine WHO performance and response to two major health crises, namely SARS (2003) and COVID-19 (2019). The study explores whether WHO have learnt their lessons from the past or if they fall back into the same patterns and embrace the same strategies as in previous crises. Given the aim of the study, the research question is:

To what extent has the WHO developed its performance from the SARS outbreak in 2003 in the containment of the present-day coronavirus?

1.2 Making use of effectiveness and performance approaches

The theory section of this essay examines effectiveness and performance and the link between the two. This includes a definition and discussion of the term effectiveness. Effectiveness and performance framework are relevant to this study since the aim is to evaluate how the WHO has adapted its performance since SARS. The theory section examines literature on regime effectiveness and IO performance, examines previous research and brings up other theoretical perspectives as suggested by previous scholars on the theme of IO effectiveness (Young, 2011; Underdal, 2002; Gutner and Thompson, 2010). The approach used to conduct this study is the policy output approach developed by Tallberg et al. (2016). This framework will enable breaking out five factors of IO performance to be applied to an analysis of WHO during the two global crises of SARS and COVID-19.

1.3 Previous research

IOs has since the time of their creation been a field of study that has drawn attention from several scholars with different theoretical and ideological standpoints. The section brings up perspectives on the role of IOs (Keohane & Martin, 1995; Abbott & Snidal, 1998;

Mearsheimer, 1994) as well as the authority of WHO (Kamradt-Scott, 2016; McInnes, 2015). This study builds on some of the most relevant contributions in the field and covers both theoretical approaches used to explain the topic as well as different aspects of existing research.

1.4 Comparative case study analysis

This is a comparative case study were case one is the WHO response during the SARS epidemic and case two is the WHO response during COVID-19. The case methodology has been inspired by and in part conducted as suggested by Eisenhardt (1989).

Both cases are analyzed with the help of the policy output approach that examines the policy documents released by WHO. The results in the two cases are compared to each other using cross-case analysis (ibid), in order to draw conclusions on similarities in WHO response and which adaptions have been made. The comparative case study approach gains from making use of the policy output approach since it offers an operationalized model for examining IO performance (Tallberg et al. 2016).

In line with the policy output approach I study the policy documents released during both crises to identify how many policies were released and then conduct content analysis to examine their orientation, instrument and target. The study is abductive and I both intend to explain and provide understanding of the development of the WHO response to global crises.

1.5 Empirical material

The empirical material consists of official policy documents published on the WHO website on under the headlines of COVID-19 and SARS. The documents are all primary sources and include different guidelines, advice, recommendations and restrictions (see Appendix for full list of selected documents). A thorough description of sampling strategies and source

criticism is given in section 3.3, 3.6 and 3.7.

1.6 Delimitations and limitations

Delimitations with the study include the decision to only include official policy documents published on the WHO website. I have reached out to WHO’s official channels for additional internal policy documents but received no response and hence the delimitation was made.

Furthermore, this study eliminates one variable of policy output namely, policy type. This is done since the WHO is merely an advisory organization that mostly publishes

declarative policy documents. Policy type suggests studying different elements and types of policies but since WHO does not offer many different policy types, this classification becomes irrelevant for the purpose of the study.

A limitation is that the study does not consider how external factors affect IO

effectiveness and simply analyses its internal performance. This makes it hard to conclude the effectiveness of WHO however it still enables an insight into its productivity which will contribute to further efficiency studies in the field. An extensive discussion of delimitations and limitations is found in section 3.7.

1.7 Disposition

The introductory chapter introduces the reader to the field of study, the aim of the essay and the research problem. Chapter two develops the theoretical discussion and identifies the factors used to examine policy output and performance of WHO. Previous research places the study within the field of IR and provide insight into other approaches used to study IOs.

Chapter 3 describes the operationalized method, discussing sampling strategies, empirical material as well as limitations and delimitations. The fourth chapter presents the results and offers a cross-case analysis. Analysis is conducted in chapter five which connects the results to previous research and theoretical assumptions. Concluding remarks and future research make up chapter six.

2 Theory

2.1 Establishing effectiveness and good performance

Defining effectiveness has engaged many IR scholars and scholars studying business organization respectively, in different ways. By studying the theoretical assumptions of effectiveness, the perspective on IO performance is broadened and allow a deeper analysis of WHO’s response. Regime effectiveness literature provides several definitions of effectiveness and some suggests the level of effectiveness is the extent to which institutions shape behavior and influence other actors in the international society (Young, 1992). Although, the most prominent one examines whether the regime “solves the problem that motivated its establishment” (Underdal, 2002:11).

These interpretations all include external factors in their measurement of

effectiveness. However, others suggest looking at internal factors as a complement to these and argue that studying performance is one of the key milestones in establishing effectiveness (Tallberg et al., 2016; Young, 2011). Performance theory argues that effectiveness is complex and needs to be narrowed down to a few factors in order to be studied on a more defined level (Tallberg et al., 2016). The approach also investigates single entity IOs instead of looking at entire regime complexes. The assumption is that without good performance an IO cannot possibly be effective.

The theory has also been narrowed down to measuring performance by dividing it into three different categories; ‘outcome’, ‘output’ and ‘process’ (Gutner and Thompson, 2010). It combines ideas that stem from bureaucracy theory (Barnett & Finnemore, 1999), rational delegation and design theory (Koremenos et al. 2001) with regime effectiveness (Young, 1992; Underdal, 2002) and operationalizes a measurement for IO performance building on the three categories mentioned above. The framework enables a measurement of effectiveness in single entity IOs. Outcome and process are developed measurements used in business management and organizational theory to assess performance and is usually broken down into the organization’s ability to achieve long and short-term goals. Outcome is the quantifiable effects of the IOs actions such as better economic growth or less poverty. This approach is often used in regime effectiveness studies and is viewed as the extent to which the regime solves the problem it is set out to battle (Underdal, 2002).

However, in measuring nonprofit IOs the goals are more complex than in profit-seeking corporations. It then becomes important to identify internal process as a part of IO performance. Process could be defined as the IOs ability to mobilize resources, developing

efficient programs or even motivate staff and create a good organizational culture (Gutner & Thompson, 2010). This cannot be used alone as a measure of effectiveness since it does not imply that the IO will meet its goals but can however help to identify the level of performance of the IO. Gutner and Thompson (2010) makes a distinction between performance and

effectiveness and argues that good performance suggests capacity of the organization whereas effectiveness measures the extent to which the organization meets its goals regardless of the internal process.

In contrast to Gutner and Thompson, Young (2011) argues that IO performance is a key determinant and essential to understand IO effectiveness and legitimacy. An organization is not effective without attaining good performance and vice versa. Hence the suggestion is that by assessing the performance of an IO, conclusions might be drawn on the effectiveness of the agency (Young, 2011). In making use of Young’s understanding of performance as a key element of effectiveness, the study of WHO’s performance enables conclusions to be drawn on the performance of the organization which can work as a complement to future studies trying to establish the effectiveness of WHO.

2.2 IO Performance

Building on the work of Young (2011) and Gutner and Thompson (2010), Tallberg et al. (2016) makes a further indentation to the performance approach when they suggest an ‘output’ analysis on policy documents to evaluate IO performance. The policy output approach examines policy documents released during a certain time period and is used to evaluate the level of IO performance by assessing policy volume, its implementation strategies, targets and type of document.

This approach is of relevance in evaluating international or nonprofit organizations that do not hold much legislative power and instead has an advisory role in global governance such as the WHO. Policy output evaluates the work of one single entity IO in the same way as Gutner and Thompson (2010) does, whereas regime effectiveness generalizes the results to identify the effectiveness of the overall regime. Tallberg et al. (2016) suggest different factors to be evaluated in order to establish the level of performance. The approach examines the number of policies released under a certain time frame, the allocation of policy documents across issue areas, what type of policy documents were published, who was the target and whether the policies are binding or not. By measuring these factors, the theoretical approach identifies the productiveness and the focus of the IO’s performance. This approach enables an analysis of how productive WHO performance was in mitigating and guiding the world

through the SARS epidemic and the COVID-19 pandemic by identifying their priorities and action plans.

The policy output approach is operationalized by being divided into five factors; volume, orientation, type, instrument and target that measures different aspects of the policy documents (Table 1). This approach enables a generalizable method to compare cases across IOs or the same IO in two different time periods (Tallberg et al. 2016).

Table 1. The five subcategories of the policy output approach Output

dimension

Definition Level of analysis

Volume The no. of policy documents produced by

the WHO during a certain time period Total no. of WHO policy documents Orientation The allocation of policy documents across

issue areas during a certain time period Total no. of WHO policy documents Type The type of policy document: regulatory,

distributive, declarative, constitutional or administrative

Single policy act

Instrument Whether the policy is binding (hard law) or non-binding (soft law)

Single policy act

Target The target of a policy: states, non-state actors, the IO itself, other IOs, the international or public community

Single policy act

Source: This table has been adapted from Tallberg et al. (2016:1082).

The five dimensions of policy output gives an overall picture of the productiveness of the IO and allows for conclusions to be drawn in the comparison of the SARS epidemic and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Policy volume measures the amount of policy documents published during a certain time period. By comparing this to the number of published documents in another case, as the study intends to do, it can answer questions such as “Have individual IOs and IO bodies become more or less productive over time?” (Tallberg et al., 2016:1083). Several studies have used this measure to study IO performance (Arter, 2006; Pollack & Hafner-Burton, 2010). This factor of IO performance is however not enough to establish performance alone and must be used in combination of the other factors suggested in the approach (Tallberg et al., 2016).

Policy orientation studies the allocation of policy documents during the same time period. By identifying the different issues addressed by the IO, this variable measure the responsiveness by the IO of a changing international society (ibid). A change in policy agenda

might illuminate patterns or sources for said change. Does the IO adapt its policy decisions to other leading agencies or is it setting the agendas themselves?

Policy type identifies different types of policy documents by dividing them into categories depending on their characteristics. Tallberg et al. (2016) suggests five different types of policy documents; regulatory, distributive, declarative, constitutional and

administrative. These help to understand the strategies used by the IO by identifying if it addresses mostly internal problems in its policy documents or focuses on external problems by addressing distributive issues, authorize behavior or set common goals (ibid).

Policy instrument studies the strategies used in getting the document implemented. Policies can be adopted through elements of hard law (binding documents) or soft law (non-binding documents). The policy instrument reveals when and where the IO uses hard law to get its policy implemented and when it uses softer recommendations to get the message across (ibid). This requires insight in the discussion on whether soft law or hard law is most effective in international settings.

Policy target looks at the different target groups that the policy documents are directed at. These might include individuals, organizations, states or none-state actors (ibid). This variable makes an analysis on where the IO directs its focus and if their actions are targeting governments or societal actors to get their agenda through.

By assessing all of these factors, Tallberg et al. (2016) suggests that the analysis brings a complete overview of the IOs performance and to put this into context they suggest using this approach to compare across cases.

2.3 Theoretical limitations

Studying policy output has its advantages and disadvantages. The performance factor output is prior to both outcome and process in the chain of causation and becomes a logical first step to examine IO performance (Tallberg et al. 2016). However, it is not enough to answer

whether or not IOs are efficient problem solvers, as suggested by regime effectiveness theory. The policy output approach generates mapping of the IOs attention and productiveness to assess its performance but leaves out other important factors of effectiveness such as power relations between member states, implementation rates etc. (Young, 2011). Moreover, good policy performance is not of relevance if the implementation or communication is not efficient.

Nevertheless, since the WHO is not the sole actor in the global health regime and other agencies have a great impact on the outcome in epidemics and pandemics, drawing

conclusions on the effectiveness outcome are not applicable to WHO as a single entity organization. Measuring ‘outcome’, as suggested by other performance scholars (Gutner & Thompson, 2010), accounts for the quantifiable effects in society, which cannot be linked solely to the work of WHO. Tallberg et al. (2016:235) suggests that studying outcome hence is most relevant when examining an autonomous IO that dominates the regime it acts within and operates in issue areas where outcome is objectively measurable.

Additionally, the theoretical approach to policy performance does not explain external factors and informal sides of global governance concerning norms and practices. However, although these limitations are worth considering, the policy output approach and performance theory still help gain insight in the operation and response by the WHO during global health crises.

2.4 Previous Research

IOs has since the time of their creation been a field of study that has drawn interest of several scholars with different theoretical and ideological standpoints. This section describes some of the most relevant contributions in the field and covers both theoretical approaches used to explain the topic as well as different aspects of existing research. The section starts with an introductory section of the broad academic overlook of the study of IOs and then continues with a more detailed description of the history and theoretical research regarding the WHO.

2.4.1 The role of IOs in the international community

Research regarding IOs and their role in the global arena is widespread and offers many different explanations for their success and failure. Some of the most commonly used theoretical explanations for IO existence is institutionalist theory that argues that IOs helps international cooperation by lowering transaction costs, providing information, enabling the notion of relative gains and facilitating international coordination (Keohane & Martin, 1995). Institutionalists argue IOs are able to address both economic and security issues through transparent sharing of information and act as the leading agencies in promoting long-lasting peace (Keohane, 1998). Abbott and Snidal (1998) argues that IOs need to be taken more seriously in academia and that scholars have to continue to study the advantages and effects of interstate cooperation. In making use of institutionalist and rationalist theoretical approach, they assert that IOs play an important role in affecting international regimes and even state behavior through creation and development of common norms and practices. Accepting the fact that power relations between states make states limit the amount of authority given to

IOs, Abbott and Snidal still argue that they make an important contribution to the international system through decentralized cooperation.

An opposing argument stems from realist theory and says that IOs are a product of state interests and that they lack the ability to act independently of its member states. They are merely seen as a reflection of the distribution of power dynamics in the world and not as autonomous political actors. Thus, the most powerful state in the global arena steers the organization in its interest through the use of hegemonic power (Mearsheimer, 1994). Realists believe states would never delegate power to supranational organizations without any

incentive of increasing its own power.

Barnett and Finnemore (1999) suggest a different model of explanation when discussing the role of IOs, their behavior and effects on the international community. They argue IO have the ability to shape the social world through creating norms and common international culture which in turn provides a reason for states to give them autonomy. IOs are in this perspective viewed as powerful actors with the ability to change, shape and construct international cooperation. According to Barnett and Finnemore (1999) this perspective does not intend to favor any specific outcome or put any emphasis on whether IOs are ‘good’ or ‘bad’, instead it explains their existence and role within the international community.

Many different theories have also been used to explain WHO and its actions.

Abeysinghe (2012) uses the theory of path dependency to explain the behavior of WHO. The underlying assumption in this theory is that institutional processes are determined by the expectations at the time of the organization’s creation (ibid). Thus, the actions of an organization are likely to be based on its historical actions and processes. Abeysinghe suggests that WHO repeats its failures and successes without learning from its mistakes. During the H1N1 pandemic (swine flu) both historical evidence and discourse promoted the use of vaccine as a protective measure which consequently targeted the focus of the IO. WHO’s response against the H1N1 pandemic was highly criticized. In the rush of delivering a fast response to the pandemic, research on the negative side effects such as autoimmune diseases and immunological complications were overlooked (ibid).

2.4.2 Authority or inadequacy?

As the leading organization in global public health, WHO has long been a target of critique for its actions and in-actions during global epidemics. The SARS outbreak in 2003 exposed deficits in the International Health Regulations (IHRs) and illuminated the organizations inadequate implementation and enforcement mechanisms (Kamradt-Scott, 2016). In 2005

new IHRs were adopted with the intention of increasing the rate of compliance among member states, giving WHO the authority to “name and shame” countries that refused to implement public health recommendations in times of crises, which can be argued made WHO go from being a passive to an active organization (Burkle, 2015). Despite the new IHRs, the organization has still been questioned. A study that analyzed WHO implementation strategies between 2007 to 2015 showed that 21 percent of the strategies were passive and most of the strategies contained sections identical to older guidelines by the same technical unit (Wang et al., 2016). In conclusion, the study suggested that WHO should include evidence-based techniques for implementation and contextualize their response in order to attain higher levels of compliance. In addition, member states were also left to self-report progress in public health as WHO lacked objective methods to measure compliance and progress (McInnes, 2015).

The critique against WHO extends beyond lack of efficient strategies, and many argues the organization has deeper organizational faults. Medford-Davis and Kapur (2014), argued that WHO is a decentralized organization that lacks common goals and shows inefficient internal coordination. During the Ebola crisis in 2015, the WHO Africa Division declared internal grade 2 emergency without consulting or reporting to headquarters, illuminating tensions between the regional offices and the Geneva office (Harman, 2014; Kamradt-Scott, 2016). The role of WHO has been debated among scholars that use different explanatory models to illustrate their critique. McInnes (2015) questions the authority of the WHO by using a constructivist approach that separates authority into three different variables: expert, delegated and capacity based. He argues the authority the WHO beholds is mostly built on the trust of its member states and its technical expertise. Consequently, the authority WHO possesses is both expert and delegated but lacks elements of capacity-based authority (ibid).

Despite the critique against WHO, some argue that the fault of inefficient crisis management also lays with its member states. Kamradt-Scott (2016) asserts, using Principal-Agent theory, that IOs are the creations of governments and that the ultimate authority is possessed by its principals. Hence the responsibility of the WHO’s failure to handle global health crises or implementation of IHRs comes down to government action and cooperation (ibid:413).

In addition, the WHO controls less than one fourth of its budget they receive from member states and voluntary contributors since a lot of funding is directed towards specific programs specified by the donor (McInnes, 2015). Garrett (2007) describes the extent to

which WHO is dependent on voluntary financial support by mentioning the contributions of the Gates Foundation that donated US$6.6 billion to global health programs in 2006. With many earmarked donations comes challenges of allocating resources and WHO has problems coordinating its donor activities. The result is an organization with a divided focus (Garrett, 2007). During the summer of 2014, the WHO was not only involved in the containment of the Ebola outbreak but also in four other emergencies among them the outbreak of polio in Syria (McInnes, 2015). At the same time the contributions from member states had not changed since the 1980s and WHO was restrained by limitations in financial means (Kamradt-Scott, 2016). WHO had to operate on a limited budget during the Ebola outbreak which affected its performance during this crucial time (Clift, 2013; McInnes, 2015; Kamradt-Scott, 2016).

2.4.3 Containing SARS

A number of studies have investigated the global response to SARS. Koh and Sng (2010) looks back at the lessons learned from SARS in light of the swine flu (H1N1). They gathered data on contamination, number of days until isolation and number of secondary cases from Singapore and concluded that in cases of early detection and quarantine, the public was effective in its prevention and control. If isolation or quarantine measures were delayed, the amount of secondary cases rapidly increased. The lesson learned is that general principles of prevention of global viruses can be effective if isolation is implemented immediately after detection.

A similar study, looking at the rate of quarantined individuals and the spread of the virus shows comparable results (Pang et al., 2003). It suggests that the containment of SARS was effective due to the rapid quarantine measures, improved management in hospitals and communities of suspected SARS patient and the spread of information to health care workers and the public (Pang et al., 2003). However, critique have been directed towards governments and their management of SARS. Studies show that legislative factors such as basic laws and policies had a negative impact on the containment of the epidemic (Lee & Jung, 2019).

During the SARS epidemic, China refused to comply with WHO regulations which made tracing the virus very difficult (Chan, 2010). WHO responded by issuing travel

restrictions to mitigate the spread of the virus (ibid). China eventually changed its stance on the outbreak due to international pressure. This shows that WHO is able to push member states into compliance using normative power and shaming tactics. Chan asserts that unlike in the UN Security Council, “no country can veto WHO decisions to issue health advisories” (Chan, 2010:97) and even asks if the WHO might be the world’s most powerful IO. Despite

WHO has been ranked “most effective member of UNDS in supporting the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)” there is internal institutional tension within the organization and a divide between its technical and normative role (Harman, 2014:1).

2.4.4 The issue of transparency during COVID-19

The novel coronavirus is today’s most pressing issue for states as well as individuals and global health actors such as WHO. As this virus is present in everyday life and knowledge is limited, these studies are merely information gathering and can be questioned, not on their methodology or approach but rather the limitations of knowledge and research. Sohrabi et al. (2020) compares the international response during the SARS outbreak to the novel

coronavirus and asserts that the response has been much more transparent now. There are still things to be considered in the novel coronavirus outbreak, e.g. it has been suggested that Chinese authorities knew about the virus long before they announced it to the public. The central government issued response guidelines 13 days before public announcement was made, suggesting lack of transparency might still be a contributing factor to the spread of the virus (Sohrabi et al., 2020). However, it took only one month to recognize the existence of COVID-19 while the same procedure took four months during the SARS epidemic (Zhu et al., 2020).

There are still lessons to be learned from the outbreak, such as lacking transparency, delay in travel restrictions and quarantine measures as well as problems in misinformation among the public and lack of funding in initial research stages (Sohrabi et al., 2020). Gralinski and Menachery (2020) discusses the difference in government response between SARS and the novel coronavirus. In contrast to Sohrabi (2020) they argue that the

management of COVID-19 has been transparent. Both the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention and the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission have been releasing regular updates on the confirmed cases and patient status in order for public health governors to be able to follow the situation closely (Gralinski & Menachery, 2020). They assert that the globalization and connectedness have enabled research communities to share information of the spread and development of the disease. Comparing the response to the SARS outbreak, the management and prevention measures have been more transparent and efficient today (Gralinski & Menachery, 2020; Wang et al., 2020). The conflicting results in the two studies further validate my research question and identifies that there is a gap in research on this subject.

WHO has been the target of several studies aiming critique and using different perspectives to explain its actions. Norris et al. (2018) reviewed guidelines published by WHO during four infectious disease outbreaks (H1N1, H7N9, MERS-CoV & Ebola) and found that severe errors in quality and information insurance were made. Findings revealed that external peer review and quality assurance processes were rarely performed and that references were infrequent and incorrect. Conclusions suggested that in order to assure trustworthiness, WHO has to carefully consider self-evaluating its guidelines after principles of transparency, avoiding confirmation bias and focusing on evidence rather than expert opinion (Norris et al., 2018). According to the critique presented above and the result of the previous study, the need for a thorough evaluation of WHO performance becomes evident. In light of the contemporary pandemic, the actions and performance of WHO has to be

examined. The following section describe my methodology in examining WHO’s performance and in detail discusses the empirical data and limitations.

3 Methodology

This essay examines WHO performance in the COVID-19 crisis by comparing to its response to the SARS outbreak 2003. The study is abductive (Dubois & Gadde, 2002) in its approach since it stems from the previously introduced policy output approach (Tallberg et al., 2016) but also uses inductive elements when searching for key coding schemes and categorization. The deductive elements of this study are used to identify factors and measures of IO

performance. Using the policy output approach enables an understanding of where the WHO has focused its efforts and resources as well as enables comparison of how the organization’s handling of global crisis has evolved since 2003.

This essay has no intention of generating any generalizations across IOs or cases but instead it aims to investigate the response in these two particular cases. This chapter

introduces the two cases and proceed to discuss the sampling strategies, methodological limitations and intended delimitations. Lastly, a critical discussion of the empirical material ends the chapter and connects to the study that follows.

3.1 Most similar cases

The study is a comparative case study that investigates WHO response in two different cases, SARS and COVID-19. This case methodology has been inspired by and in part conducted as suggested by Eisenhardt (1989). SARS was an epidemic that broke out in November 2002 and was confirmed contained by the WHO in July 2003 (World Health Organization, 2003). COVID-19 is the ongoing global pandemic that was reported to the WHO on the 31st of

December 2019. The two diseases derive from the family of coronaviruses that causes respiratory syndromes such as pneumonia and spread from person to person via droplet contamination. The medical terms for the two viruses are SARS-CoV for the virus that caused the outbreak in 2003 and SARS-CoV2 for the present-day coronavirus. These two cases were chosen because of their similar qualities and high probability in similar response from the WHO, as influenced by the most similar system design (Anckar, 2008). This study aims to investigate the role of the WHO by examining its performance during both crises and does so by using the operationalized policy output approach offered by Tallberg et al. (2016).

3.2 The policy output approach

The policy output enables mapping out the performance of WHO and offers a concrete framework for comparison across cases. The method is structured according to the policy output approach (see Table 1, p.11) and starts by investigating the total policy volume of each case. This is conducted by a thorough count of the empirical material in order to establish the amount of policy documents, media and press release statements, training exercises, toolkits and situation updates. The total policy volume only corresponds to the documents that can be defined as setting policy agenda by working as guidelines, recommendations, advice and information.

The next step is to study policy orientation, more specifically the orientation of policy documents across different issue areas. This classification of policy topics was done on all policy documents in the respective cases. Different policy topics are divided into

categories used to classify the policies (Tallberg et al, 2016). These categories could either be chosen based on an established list of topics such as ‘development’, ‘security’ and ‘human rights’ or they can be inductively established based on thorough studying of the empirical material (Tallberg et al., 2016:1084; Baumgartner & Jones, 1993). Since this study is not used to evaluate all of WHO’s work but merely its response in two specific cases, the predefined topic list is too general to identify differences in policies concerning SARS and COVID-19. Hence the predefined categories were not applicable in this study and the choice was made to inductively establish the categories based on the empirical material. The categories and their respective description are presented below (see 3.2.1). Once the categories have been

established, categorization of the policy documents were made through examining the content of its headline. This enables results to be presented in a chart that shows the number of policy documents allocated to each topic.

3.2.1 Categorization of policy orientation

Medical research: Any document where the headline indicates guidelines, recommendations, suggestions or findings of medical research. Based on a study of Röhrig et al. (2009), medical research includes everything from primary clinical, epidemiological and basic research to secondary meta-analysis and reviews.

Surveillance: Any document where the headline indicates guidelines, recommendations and restrictions on how to report, alert and verify cases of SARS outbreak.

Travel advice: Any document where the headline indicates any restriction, recommendation or guidelines in travel, transportation, gatherings, exports and imports that do not include media or press release statements.

Media/Press release: Any document where the headline indicates that the document was a presented during a press release or any other media forum including internet and video sources.

Standard operating procedures: Any document where the headline suggests that the document describes standard operating procedures for member states, hospitals or the international community excluding guidelines on laboratory, clinical or research practices.

Resources & Supplies: Any document where the headline indicates that the document describes strategies and recommendations on resources or supplies.

Social stigma: Any document where the headline suggests that the document describes any type of social stigma, including mental health, socially vulnerable and risk prone groups.

Public advice: Any document where the headline or categorization on website suggests that this includes guidelines, recommendations, information and policy for the public community.

3.3 Sampling strategy

In order to identify policy instrument and policy target, a representative sample of each case had to be created to delimit the amount of policy documents to analyze. Scholars have debated the appropriate sample size for qualitative studies and while some argue a too small of a sample size is not able to provide enough material to generalize or theorize the result, others say a too large of a sample size also brings methodological problems and makes it hard to conduct a thorough analysis (Bryman, 2012:425). However, in a study that examined the abstracts of doctoral theses based on interviews and qualitative research concluded that the mean sample size was 31 and the median was 28 (Mason, 2010).

Based on this and other studies, Bryman (2012) concludes that the sample size differs depending on the aim of your research, an appropriate sample size might not be predefined but rather reached when you feel a theoretical saturation is achieved. However, in order to adopt a comparable approach and due to the scope of the essay, I limit my sample

size to 15 policy documents in each case while examining the policy instrument and target. This limitation enables a thorough content analysis of each of the policy documents and yet still provide a enough data to make the sample representative of its case. This limitation also had to be made in order to fit the scope and timeframe of the essay.

To avoid the risk of missing out important documents listed under headlines on the website, the strategy of stratified sampling was used. Stratified sampling divides the policy documents into subgroups so that every headline with a connection to SARS on the website is included in the investigation (Suri, 2011). To create a representative sample for SARS, the sample size, 15, was divided by the total policy volume generating an estimated 26 percent. This enabled 26 percent of the documents under each headline to be sampled. In order to establish a representative sample, random selection was conducted on the policy document under each headline. The headlines investigated were the same as assigned by the WHO themselves on their website (Table 2).

Table 2. Sampling strategy SARS

Headline No. of documents No. of documents sampled

Guidelines/recommendations 28 documents 7 documents WHO Collaborative

Networks

7 documents 2 documents

Travel Advice 21 documents 5 documents

Other sources (WHO Global conference & SARS technical briefing)

2 documents 1 document

Twenty-six percent of the policies were chosen from each headline using random selection, which ultimately created a sample of 15 documents representative to the case of SARS. The similar process was repeated when creating a sample for the case of COVID-19. Stratified sampling was used to divide the material into subcategories made up by the headlines concerning COVID-19 on WHO’s website. In order to create a sample of 15 documents, the number 15 was divided by the total amount of policy documents which turned out to estimate to 7,5 percent. Consequently, 7,5 percent of the policy documents under each headline were chosen using random selection as described in the first case. The headlines investigated during COVID-19 are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Sampling strategy COVID-19

Headline No. of documents No. of documents sampled

Public Advice 76 documents 5 documents

Country and technical guidance

72 documents 5 documents

Travel Advice 6 documents 1 document

Research and development 42 documents 3 documents Strategies, plans &

operations

3 documents 1 document

All headlines containing six documents or less during both SARS and COVID-19 were represented by one policy document. This is not representative of neither 26 nor 7,5 percent of the total amount of documents under these headlines but the strategy was used in order to not miss important documents singled out under separate headlines.

3.4 Content analysis

Once the sample for both cases has been established, conducting content analysis to conclude the policy instrument and policy target can commence. Policy instrument refers to the

methods of application the policy document suggests. Is it hard law, meaning the document has binding qualities that must be implemented by its member states or does it make use of soft law and work in form of recommendations and advice? Identifying policy instrument enables conclusions to be drawn on the procedure of WHO’s response. Does hard and soft law present possibilities or restraints on the effectiveness and compliance with the policy? How has it affected the WHO’s response?

The coding scheme for identifying policy instrument requires a definition of what hard and soft law is (see 3.4.1). Making use of the definition of hard and soft law presented below, the coding scheme used to detect binding qualities is the use of the textual marker ‘entry-into-force’ as suggested by Mitchell (2003). A lack of said code infers that the policy document is non-binding. Other indicators of non-binding documents are: ‘advice’,

‘guideline’ and ‘recommendation’.

Policy target was established by using a list of different targets presented by Tallberg et al (2016). They argue the most commonly targeted actors are states; none-state actors; the international and public community; the IO itself; or other IOs. Policy target is

operationalized by the use of these targets as categorical variables. The table below presents the different categorical variables and their respective inductively established measures.

Table 4. Policy target measures

Categorical variable Inductive measure used in text

States National Health Authorities

Member States

Government Authorities

Non-state actors Clinicians /Laboratory personnel

Hospital personnel Health care staff Scientific community International/ public community Individuals

Travelers and airlines International community Public community

The IO itself WHO

Note: One of the targets suggested by Tallberg et al., namely ‘other IOs’ have been excluded since none of the policy documents included this target.

By using the respective inductively established measures, each policy document in the two cases was assigned a policy target.

3.4.1 Hard and soft law definition

In order to identify policy instrument, it is crucial to establish a definition of hard and soft law. Scholars have debated whether hard and soft law is supposed to be viewed as a

dichotomy or as a continuum (Abbott & Snidal, 2000; Tallberg et al., 2016). Hard law can be defined as “legally binding obligations that are precise (or can be made precise through adjudication or the issuance of detailed regulations) and that delegate authority for interpreting and implementing the law” (Abbott & Snidal, 2000:421). Abbott and Snidal further establish three dimensions of hard law: precision of rule, level of obligation and delegation of implementation to third parties.

Soft law however can be defined as a realm or a continuum where legislations or legal arrangements are weaker along one or more of these three dimensions. Thus, soft law is everything between pure political arrangements to a weakened legislation. Using this

interpretation of hard and soft law enables an classifying analysis of policy instrument. While still acknowledging the fact that soft law can be understood as a continuum this analysis uses the coding scheme suggested by Mitchell (2003).

3.5 Conducting the literature review

To create the literature review I conducted searches primarily on the Stockholm University online library database: https://www.su.se/biblioteket/ where I delimited myself to only search for peer reviewed articles, searched for secondary sources and used the snowball-technique on google scholar.

Key search words included:

“Epidemic”, “Compliance”, “Global governance”, “WHO”, “Effectiveness”, “2003”. Each of the phrases were combined with “SARS” and “COVID-19” respectively.

3.6 Empirical material

The empirical data are primary sources and consists of the official policy documents released during the SARS epidemic 2003 and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The data on the case of SARS was recovered from the WHO official website1 and their equivalent during the

COVID-19 pandemic2. The material is to a large extent qualitative but WHO policies include

both qualitative and quantitative elements. In collecting the data, I have employed the snowball method, going through secondary sources and conducting searches on the WHO official website using search words such as: ‘SARS’, ‘coronavirus’, ‘COVID-19’, ‘policy documents’ in different combinations.

I acknowledge that there might be more policy documents of relevance that have not been made public, concerning internal operations or confidential documents, and I have contacted the WHO to request further documents of interest. I did not receive any answer to my request and hence I have delimited my empirical material to only consist of the policy documents made official by the WHO on their website.

Another limitation with the data is that COVID-19 is an ongoing crisis and the material is constantly being updated, thus it is hard to draw any firm conclusions before this crisis has been resolved. This essay examines the first stages of WHO response and identifies whether their performance has been effective or not compared to the response during SARS. However, I will not be able to conclude whether the response as a whole were more or less effective than during SARS, in order to do that one would have to repeat this study when the COVID-19 pandemic is declared contained.

1https://www.who.int/csr/sars/en/

3.6.1 Definition of policy document

The definition of what is included as policy document in this study is based on an empirical understanding of WHO’s documents on the two cases. In order to be classified as policies these had to include any type of guideline, recommendation, advice or suggestion on further actions in addition to just delivering information. Thus, situation updates containing

descriptive statistics, such as lists of affected areas, number of infected and diseased, were not included in this definition. However, policy documents included different types of media channels and whereas most of them were traditional written sources, other sources included video and visual images that provided information, advice and recommendations to the public.

3.7 Delimitations and limitations

Delimitations made to material include not making use of the third policy output variable namely; policy type. This variable has been excluded from the analysis since WHO is an advisory organization and holds no legislative power over its member states. Consequently, one might suppose that most of the policy documents contain declarative policy types. This type of policy creates a new agenda or position of member states by declaring common goals, providing advice and recommendations (Tallberg et al., 2016). They also assert that some policy types are associated with certain policy instruments, meaning, given the role of the organization, only declarative, administrative or constitutional policy types might be

expected. Since this classification would not provide considerable evidence that would change the final conclusions and because its policy types can be guessed in advance, the variable policy output has been eliminated from the analysis.

Another delimitation with the analysis is the sample size. Larger samples would have been preferred, however, because of the scope of the essay, the sample size had to be limited. This is made up for by the usage of a thorough sampling strategy that enables a representative sample. This study would gain from being repeated with the use of larger samples.

A limitation with the policy output approach is the fact that it overlooks external factors and independent variables that has an effect on the performance of an IO. The method aims to study the performance and productivity of an IO without considering factors such as cooperation problems, tensions between member states, implementation of policy and international norms. However, as a complement to other effectiveness studies concerning outcome, impact and process, policy output serves a great purpose in establishing IO performance as a key baseline to IO effectiveness (ibid).

The policy output approach uses a neopositivist epistemology (Bryman, 2012) that eliminates critical analysis and elements describing the impact that external factors have on performance and effectiveness. This delimits the analysis to not consider how IOs interact in regime formations, or how power relations or disagreements among member states affect the actions of the IO.

The theoretical approach has both its advantages and disadvantages. The

operationalized model measures IO performance and facilitates a comparative approach that enables conclusions to be drawn on WHO’s performance in two cases. However, the method also has its drawbacks since it excludes analysis of external independent variables that plays a big part in establishing the effectiveness of the organization. Hence this approach offers no hands-on explanation for establishing effectiveness.

As the empirical material consists of predefined, primary sources and the study aims to investigate the response of WHO by examining its policy document, extensive source criticism is not done in this case. However I acknowledge the fact that the policies analyzed are only official documents published by WHO and that they possibly reflect a bias in what WHO want to communicate. According to the policy output approach, an organizations policy documents are of relevance when examining output (Tallberg et al., 2016). However, the same limitations as discussed regarding the approach in general apply.

4 Results

The following chapter presents the results of the study according to the logical structure of the policy output approach (Table 1). The results are presented in categorical order starting with policy volume, policy orientation, policy instrument and policy target. Under each headline both the case of SARS and COVID-19 is represented. In the end of this chapter a comparative and theoretical analysis follows, that connects back to the research question, theoretical framework and previous research and enables conclusions to be drawn.

4.1 Policy volume

The policy volume represents the total amount of policy documents published during both cases. The result is presented in the table below.

Table 5. Policy volume

Policy output SARS COVID-19

Policy volume 57 policy documents + 33 Media/Press release + 300 situation updates 199 policy documents + 252 media/press release + 16 training exercises + 5 toolkits + 91 situation updates + Database with 6900+ research articles Note: These include policy documents published up until the 20th of April 2020.

The total policy volume are 57 policy documents during the SARS epidemic ranging from March 2003 until October 2004, a span of 20 months. The policy volume during the current COVID-19 pandemic is 199 documents that range from 10th of January 2020 until 20th of

April 2020, making it a little more than 3 months, 101 days to be exact. Excluded from this calculation are media and press release that make up 33 transcripts of WHO press releases during the SARS epidemic and 252 media sources during the COVID-19 pandemic. These are different types of internet, picture and video sources as well as transcripts of WHO press release. During both outbreaks the WHO has published situation updates regularly that present statistics and information on the affected areas as well as reported number of infected and deceased, these are 300 updates during SARS and 91 during COVID-19.

In addition, the WHO has included new ways of mediating information by publishing 15 online training exercises and 5 toolkits for assessing performance and

COVID-19. These are targeted to government officials, health care staff, public health authorities and scientists.

4.2 Policy orientation

The policy orientation is referred to as the allocation of policy documents across different policy issue areas. The different policy areas were established inductively and operationalized through use of categorical variables. The categories and their definition are presented in 3.2.1 and results of the study in 4.2.1 & 4.2.2.

4.2.1 SARS

The figure below presents the different policy topics and their respective number of policies allocated to that topic.

Figure 1. SARS policy orientation

This shows the allocation of policy documents across issue areas during SARS (March 2003- October 2004). Media/ Press release has been included not as policy documents but rather to map out the development of information channels from 2003 to present day. The results show that travel advice is the most represented policy issue area with 23 documents, closely

followed by medical research were 21 policy documents were set out to contribute to research debates. The standard operating procedures included 7 guiding documents on actions and procedures that stakeholders and leading actors were expected to follow. Lastly, 6 policy

21 6 23 33 7 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35

No. of policy documents

Allocation of WHO policy documents during the

SARS epidemic

documents were set out to advice and steer the surveillance methods member states were expected to follow in terms of alert, verification and reporting cases of SARS.

4.2.2 COVID-19

The results of the policy orientation in the case of COVID-19 is presented in the figure below. The figure shows a bar chart of the different policy topics with respective number of policy documents.

Figure 2. COVID-19 policy orientation

Note: This study shows results of policy document allocation up to 20th of April 2020.

The results show that public advice is the most represented policy issue area with 78 policy documents contributing to the public, this is followed by medical research that includes 52 policy documents that aim to advice, inform and contribute to medical research of any kind. 43 policy documents have been allocated to standard operating procedures whereas resources and supplies, social stigma and surveillance has received lower attention with an allocation of 8, 5 and 3 policy documents. As motivated in 4.1, tools, training and exercises are included to shed light on new types of information channels adapted by the WHO however they cannot be defined as policy documents and hence is not included in the total policy volume. Media/ Press release is also excluded from the total policy volume.

52 5 10 252 43 8 3 78 5 16 0 50 100 150 200 250 300

No. of policy documents

Allocation of WHO policy documents during the

COVID-19 pandemic

Medical research Surveillance Travel advice Media/ Press release

Standard operating procedures Resources & Supplies

Social stigma Public health advice Toolkits

4.3 Policy instrument

Mapping out policy instrument is crucial to understanding the strategy of the IO and in order to draw conclusions on the performance of the WHO. Comparing the results of SARS to COVID-19 enables analyzing any changes made to the strategies and response of the WHO. Presented below is a table that describes the instrument of each policy document analyzed. The results show that none of the policy documents during the SARS outbreak nor during the COVID-19 outbreak shows any element of binding nature or hard law implementation.

4.3.1 SARS

The table below presents every policy document in my sample from the case of SARS and presents its policy instrument and binding or non-binding nature.

Table 6. SARS policy instrument

Policy document Binding

Non-binding 1. WHO guidelines for the global surveillance of severe acute respiratory

syndrome (SARS). Updated recommendations, October 2004 No Yes 2. WHO SARS Risk Assessment and Preparedness Framework No Yes 3. Alert, verification and public health management of SARS in the

post-outbreak period No Yes

4. WHO hospital discharge and follow-up policy for patients who have been

diagnosed with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) No Yes 5. WHO biosafety guidelines for handling of SARS specimens No Yes 6. Guidance for Mass Gatherings: hosting persons arriving from an area with

recent local transmission of SARS No Yes 7. Consensus document on the epidemiology of severe acute respiratory

syndrome (SARS) No Yes

8. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), Laboratory diagnostic tests No Yes 9. The operational response to SARS No Yes 10. World Health Organization issues emergency travel advisory No Yes 11. Update 11 – WHO recommends new measures to prevent travel-related

spread of SARS No Yes

12. Update 17 – Travel advice – Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of

China and Guangdong Province, China No Yes 13. Summary of WHO measures related to international travel No Yes 14. Update 19 – China deepens its collaboration to contain SARS, WHO revises

its advice to international travellers as new data come in No Yes 15. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): Status of the outbreak and

lessons for the immediate future No Yes The policy documents during the SARS outbreak shows no elements of binding nature or hard law implementation.

4.3.2 COVID-19

Table 7. COVID-19 policy instrument

Policy document Binding

Non-binding 1. Advice on the use of masks in the context of COVID-19 No Yes 2. Rational use of personal protective equipment for coronavirus disease

(COVID-19) No Yes

3. Getting your workplace ready for COVID-19 No Yes 4. COVID-19 and violence against women No Yes 5. Why it is recommended to avoid close contact with anyone who has fever

and cough? [video source] No Yes

6. Responding to community spread of COVID-19 No Yes 7. Global Surveillance for human infection with coronavirus disease

(COVID-19) No Yes

8. Infection prevention and control during health care when novel coronavirus

(nCoV) infection is suspected No Yes

9. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak: rights, roles and responsibilities of health workers, including key considerations for occupational safety and health

No Yes

10. Preparedness, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) for

refugees and migrants in non-camp settings – Interim guidance No Yes 11. Updated WHO recommendations for international traffic in relation to

COVID-19 outbreak No Yes

12. A coordinated Global Research Roadmap: 2019 Novel Coronavirus No Yes 13. Instructions for Submission Requirements: In vitro diagnostics (IVDs)

Detecting Antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 virus No Yes 14. WHO Working group – Vaccine Prioritization for COVID-19 Vaccines No Yes

15. COVID-19 Strategy update No Yes

The policy documents during the COVID-19 shows no elements of binding nature or hard law implementation.

4.4 Policy target

This part of the study investigates the target of the policy documents and aims to enable an understanding of the focus and directed response of the WHO. The policy target is

operationalized and classified categorically according to a list of policy targets offered by Tallberg et al. (2016). In making use of the categories proposed by Tallberg et al, I also offer inductively established subcategories for coding and placing each policy document in a category (see Table 4 for categorical variables and respective measures).

4.4.1 SARS

This table presents the different policies and their target through usage of inductive measures. Table 8. SARS policy targets

Policy document Inductive measure Categorical

variable 1. WHO guidelines for the global surveillance of severe

acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Updated recommendations.

National Health Authorities

States (4 docs.) 2. WHO SARS Risk Assessment and Preparedness

Framework. Member States

3. Update 11 – WHO recommends new measures to

prevent travel-related spread of SARS. National health authorities 4. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): Status of

the outbreak and lessons for the immediate future. Member states 5. Alert, verification and public health management of

SARS in the post-outbreak period. Clinicans, laboratory personnel

Non-state actors (4 docs.) 6. WHO hospital discharge and follow-up policy for

patients who have been diagnosed with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS).

Hospital personnel

7. WHO biosafety guidelines for handling of SARS

specimens. Clinicans, laboratory personnel 8. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS):

Laboratory diagnostic tests. Laboratory personnel 9. Guidance for Mass Gatherings: hosting persons

arriving from an area with recent local transmission of SARS. Individuals International/ Public Community (6 docs.) 10. The operational response to SARS General public

11. World Health Organization issues emergency travel

advisory Travellers and airlines 12. Update 17 – Travel advice – Hong Kong Special

Administrative Region of China and Guangdong Province, China

Individuals

13. Summary of WHO measures related to international

travel Individuals

14. Update 19 – China deepens its collaboration to contain SARS, WHO revises its advice to international travellers as new data come in

Travellers & international community 15. Consensus document on the epidemiology of severe

acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) Mainly: WHO, clinicians, The IO itself (1 docs.)

Figure 3. SARS policy target

Presented in this bar chart is the allocation of policy documents across targets during the SARS epidemic. Results show that 4 of the policy documents were directed at member states, 4 at non-state actors such as hospital personnel and clinicians, 5 documents were directed to the international or public community and 1 to the WHO themselves.

2 2 1 3 3 2 1 1 0 0,5 1 1,5 2 2,5 3 3,5

States Non-state actors International/ Public community

The IO itself

WHO policy target allocation during SARS epidemic

National Health Authorities Member states

Hospital personnel

Clinicians/ Laboratory personnel Individuals

Travellers & airlines General public WHO