1 CULTURE-LANGUAGES-MEDIA

Independent Project with Specialization in English

Studies and Education

15 Credits, First Cycle

Peer Review in EFL Writing: Its Effect on

Critical Thinking Skills and the Role of

Digital Tools in Facilitating the Process

Kamratrespons i skrivning för engelska som andra språk: effekterna på kritiskt

tänkande förmågor och rollen av digitala verktyg i främjandet av processen.

Murtadha Al-Kefagy

Cristina Nagy

Master of Arts in Upper Secondary Education, 300 credits English Studies and Education

2020-01-17

Examiner: Anna Wärnsby Supervisor: Jasmin Salih

2

Table of Contents

Abstract ... 3

1. Introduction ... 4

1.1 Functional Definition of Critical Thinking ... 6

2. Aim of Study ... 8 3. Method ... 9 3.1 Search Delimitations ... 9 3.2 Inclusion Criteria ... 10 3.3 Exclusion Criteria ... 10 4. Results ... 12

4.1 Research on Peer Review’s Effects on Critical Thinking Skills ... 12

4.2 Research Findings: Peer Review’s Effects on Evaluation and Self-Regulation ... 15

4.3 Research on Digital Tools’ Role in facilitating the Peer Review Process ... 17

4.4 Research Findings: Digital Tools’ Role in facilitating the Peer Reviewing Process ... 18

5. Discussion ... 20

5.1 Peer Review Can Develop Critical Thinking Skills ... 20

5.2 Digital Tools Can Help Facilitate the Peer Reviewing Process ... 22

6. Conclusion ... 24

3

Abstract

This paper focuses on peer reviewing as part of the writing process and as a pedagogical strategy that can help students develop their writing and critical thinking skills. To do so, it examines the extent to which peer reviewing can develop English as a foreign language (EFL) students’ ability to evaluate and reflect on their writing in upper secondary school. Moreover, this study investigates whether digital tools can help to facilitate the peer review process. By reviewing and synthesizing ten empirical studies from the period 2013-2020, the study found that students who engage in peer reviewing in writing develop critical thinking skills, self-regulation and evaluation. It further shows that there is a consensus

between researchers regarding the usefulness of peer review in developing critical thinking skills. However, the findings indicate the importance of including guided peer review training before peer review activities. Furthermore, there is a strong indication that digital tools can help facilitate the peer review process if used appropriately. Digital tools help engage students in the peer review process since they are able to interact with each other’s texts online. Lastly, the findings of the study are in line with the Swedish national

curriculum and the English syllabus for upper secondary school. Therefore, teachers in Sweden should consider the use of familiar digital tools to engage students in peer review to develop their writing and critical thinking skills.

Key words: Peer review, Peer assessment, Writing, Critical thinking, regulation, Self-monitoring, self-reflection, Evaluation, Digital tools, EFL, Upper secondary, Swedish classroom.

4

1. Introduction

Assessment is one of the most important tasks that teachers must perform. However, in Swedish upper secondary schools, formative assessment on writing in English is perceived as time consuming and, in some cases, ineffective (Skolverket, 2020). Similar to the

Swedish education context, Burner’s study (2015), in Norway, shows that there is hesitation from teachers to use formative feedback in EFL writing classes despite their genuine approval of using peer review. Burner (2015) claims that assessment has mainly been used for summative purposes in Norwegian schools (p. 626). The teachers’ hesitation in applying formative assessment for English writing mainly relates to the lack of time and teachers’ low expectations of how students will use the feedback (Burner, 2015, p. 641). Therefore, extensive research has been done regarding the benefits of peer review as teaching method that can help students develop their writing and critical thinking skills.

Researchers argue that peer review should be incorporated in the writing process because it enables students to reflect on the quality of others’ writing and their own (Baker, 2016, p. 188. See also Babaii & Adeh, 2019; Harutyunyan & Poveda 2018; Bozkurt 2020;

Kuyyogsuy, 2019). The peer review process is a learner-centric approach where students are included in the assessment process. It enables the learner to improve on their writing through collaborative effort with fellow peers. Accordingly, peer reviewing activities follow the social theory of Vygotsky’s “zone of proximal development” (ZPD) because students are placed in a social setting where they learn from each other. The interactions between students can be beneficial since they can challenge each others’ thoughts and reflect on their own ideas while doing so (Harrison et al., 2015, p. 79). Moreover, Skolverket (2019) encourages the use of peer reviewing in the classroom since it states that students learn more from fellow peers and teachers than they would independently (p. 3). Further, engaging students in peer review in the writing process can foster self-regulation,

independence and it promotes language learning and critical thinking skills (Baker, 2016, p.180; Baran-Łucarz, 2019, p. 313).

With the amount of information that comes with the digital era, developing critical thinking skills has become more important than ever. Further, Skolverket (2016) suggests that critical thinking skills are fundamental tools to have to be a part of a democratic society. The Swedish curriculum states that teachers need to help students with strategies for

5

selecting, researching, and evaluating sources, which is part of the critical thinking and writing process (Lgy11). The Swedish syllabus for English 5, 6, and 7 states that students should be able to produce different types of text and be able to assess, argue, and reason to strengthen their opinions (Lgy11). Harrison et al. (2015) argue that peer reviewing should be implemented in English writing classrooms as it fosters learner autonomy and self-regulation (p. 76). Moreover, Skolverket (2020) encourages further exploration of

collaborative tasks and formative feedback as strategies to help students develop complex skills such as critical thinking. However, Wang and Woo (2010) claim that students in upper secondary school lack critical thinking skills and that it is a challenge for teachers around the world. Moreover, Berridge (2009) claims, students struggle to make a connection between writing and thinking (p. 4). Therefore, it is worth exploring the benefits of peer review on developing critical thinking skills and examining whether it promotes self-regulation during the writing process.

Sharp and Rodriguez (2020) discuss the benefits of using digital tools to further develop students’ writing through peer reviewing. Technology development can be of great use in the classroom since it has brought some innovative ways for students to collaborate and interact with each other by giving and receiving feedback (Kayacan & Razı, 2017, p. 562). According to Kayacan and Razı (2017) digital tools can facilitate the peer reviewing process because they increase students’ and teachers’ accessibility to students’ texts. This function enables students to increase collaboration throughout the writing process and during the peer reviewing process (p. 564). Skolverket (2020) emphasizes that teachers should give students the opportunity to make use of “different aids and media” to develop students’ language learning (Lgy11). However, in Swedish classrooms, these software programs are mainly used for writing essays, searching information, and making presentations (Almén et al., 2020, p. 290). Therefore, it is worth investigating innovative ways in which digital tools can help facilitate the peer reviewing process in EFL writing classrooms.

Importantly, the chosen digital tool should be familiar to both the teacher and the students for it to be useful in the peer reviewing process (Sharp & Rodriguez, 2020, p. 9-10).

Furthermore, for the tools to help learners in their writing process, teachers must provide students with clear instructions regarding how to give formative feedback. In other words, digital tools can help facilitate the peer reviewing process but only if students are provided

6

with clear instructions on how to provide helpful feedback (Sharp & Rodriguez, 2020, p. 10).

1.1 Functional Definition of Critical Thinking

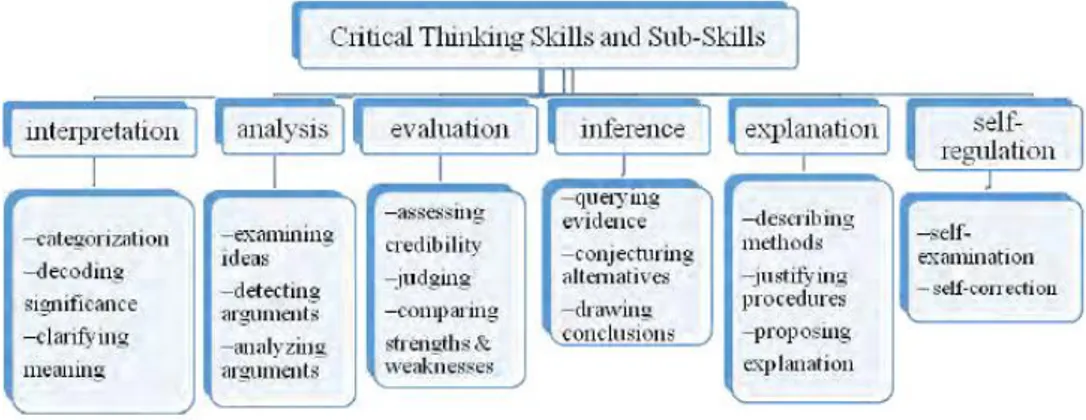

Since there are multiple definitions of the term critical thinking, we have selected a definition that will allow us to apply the term to answer our main research question. We will mainly use Facione’s (1992) definition of the term. He categorized critical thinking into six skills, each containing their own sub skills as shown in Figure 1. Of the six critical thinking skills Facione describes, we will mainly consider the use of two: evaluation and

self-regulation. The reason is because they are the most relevant in the writing process —

specifically during peer review. These skills are described as cognitive skills and are the core of critical thinking.

Figure 1. Critical Thinking Skills and Sub-Skills Based on Facione Fatemeh Sadeghi et al., 2020, p. 65)

Evaluation is defined as the ability to assess the credibility of information based on

experience, perception and/or judgement. In writing, evaluation concerns assessing whether an argument’s conclusion is well supported by the information that the writer provides. In other words, assessing if a paper has a logical and cohesive structure (Facione, 1992, p. 6). A teacher may consider structuring peer assessment in a way where students assess the information provided in a peer’s text and compare it to a set of assessment criteria. This can also enable students to compare their own writing knowledge to the set criteria. Self-regulation is about identifying and observing one’s own thoughts and

positionality in comparison to others. A general example would be to examine one’s own views on controversial matters while keeping in mind one’s own biases (Facione, 1992, p. 6). However, Baker (2016) suggests that by working with peer assessment in writing, students practise self-regulation because they must consider their own writing by giving

7

feedback to peers (p. 180). These two skills, evaluation, and self-regulation are the functional definition of critical thinking that will be examined in the reviewed studies and referred to throughout the paper.

This research will focus on peer reviewing as part of the writing process and as a

pedagogical strategy that teachers can use to help students develop critical thinking skills. Due to the complexity of “critical thinking” and the skills it entails, we will limit our research to two particular skills —specifically evaluation and self-regulation. In addition, we will explore the use of digital tools in the classroom as a strategy to help facilitate the process of peer reviewing. This will be done by analysing and evaluating different strategies of incorporating modern technology in the peer reviewing process. There are various studies that discuss how effectively students produce formative feedback and make use of peer review (Baker, 2016; Hovardas et al., 2013; Harutyunyan & Poveda, 2018). In addition, there are some research papers that discuss the benefits of peer review in relation to critical thinking skills such as self-regulation and evaluation (Harrison et al., 2015; Kuyyogsuy, 2019; Bozkurt, 2020; Harutyunyan & Poveda, 2018). However, there is no clear correlation between students’ use of peer review and the extent to which it can help students develop critical thinking skills in upper secondary classrooms. We will attempt to make the relation between the two clearer, but first we will define what we mean by critical thinking and state the specific skills we will be investigating in relation to peer review.

8

2. Aim of Study

By analysing and evaluating studies that discuss the relation between peer review and critical thinking, this research aims to develop an understanding of the extent to which peer review can benefit upper secondary EFL students in their writing and help them develop critical thinking skills. In addition, this research will investigate whether digital tools can help facilitate the peer review process.

● To what extent does peer review in the writing process help English as foreign language learners (EFL) in upper secondary school develop critical thinking skills? ● In addition, how do digital tools help facilitate the peer review process?

9

3. Method

We will review ten articles to (1) examine the use of peer review and its effects on two critical thinking skills and (2) investigate the use of digital tools to facilitate the peer reviewing process. To collect the relevant studies, we used mainly the database ERIC because it is the main database used for education research. Further, we limited our research to only peer reviewed journals since they require a certain process to ensure academic integrity.

3.1 Search Delimitations

We initiated our study by identifying key terms for our research questions, namely “peer assessment”, “critical thinking”, “digital tools”, “Writing”, “EFL”, and “upper secondary”. Later, we used the database ERIC to search for articles using a combination of our chosen search terms such as “peer review”/“peer-assessment” and “critical thinking”. While reading some selected articles, we learned that there are multiple definitions used for the term critical thinking. Therefore, we had to find the functional definition that is most relevant to our research and include it in our search terms. As mentioned earlier, we decided to use “self-regulation” and “evaluation” to specify what we mean by “critical thinking skills”. These two new terms helped us narrow down the studies that were relevant to answering our main research question.

To find relevant sources for our follow up question we used the search terms “digital tools” and “peer review”/“peer assessment”. This resulted in studies that either discussed the general use of digital tools in the classroom or research that focused on the

effectiveness of peer review. However, we found three studies that examine the use of digital tools in relation to the peer review process. In addition, we chose to include some secondary sources to help contextualize the use of digital tools in Swedish upper secondary classrooms. These articles are mainly provided by Skolverket.

We tried using the terms, “EFL”, “upper secondary”, and “Swedish classroom” in combination with the key terms mentioned above. However, the articles we found were not relevant to our research questions. Some of the articles examined the use of digital tools in the context of Swedish classrooms but did not relate it to the peer reviewing

10

process. Other sources discussed the benefits of peer review on critical thinking, but they each had their own functional definition of the term that did not match ours. These results led us to limit our search terms to different combinations of the terms: “Peer review”, “Peer assessment”, “Critical thinking”, “Self-regulation”, “Evaluation”, “EFL”. This limitation resulted in us finding studies from other countries and most are in the context of higher education.

3.2 Inclusion Criteria

To refine our research, we included studies that discuss the use of peer review to develop critical thinking skills using the functional definition explained above. Despite our aim to investigate the benefits of peer review regarding critical thinking in EFL upper secondary school, most articles we found aimed for higher education. However, we can still apply the results of these studies to Swedish EFL upper secondary students because the participants’ level of English proficiency in the studies are equal or less than the requirement levels for English 5, 6, and/or 7 in Swedish schools (EF English Proficiency Index, 2020).

The sources’ date range is between 2013 and 2020. The reason is to ensure that we analyze the latest findings on the use of peer review and its effects on developing critical thinking. For the second research question, the date range is between 2017 and 2020. This is due to the pace in which technology develops and the way it is used in a classroom setting. It is crucial to analyse recent studies regarding the use of digital tools in the peer reviewing process because that can provide us with the most relevant answer to our second question.

3.3 Exclusion Criteria

We excluded articles that lacked an empirical study regarding the effects of peer review on developing students’ critical thinking. Moreover, articles that did not use the skills

self-regulation and evaluation as their functional definition for critical thinking were excluded. For

studies related to digital tools, we chose to exclude articles that did not discuss the use of digital tools in relation to peer review. Lastly, studies related to digital tools older than five years were disregarded since the use of technology in the classroom changes rapidly. The literature review and synthesis entail ten articles in total, some of which discuss both elements of our research questions. To clarify, we divided our ten articles based on our

11 three main research areas as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Area of interest Total number of references Peer assessment and

Self-regulation

8 Peer assessment and Evaluation 4

Peer assessment and

12

4. Results

This section will present ten research articles that will help answer the research questions for this paper: “To what extent does peer review in the writing process help English as foreign language learners (EFL) in upper secondary school develop critical thinking skills?” and “how do digital tools help facilitate the peer review process?”. First, we will summarize and synthesize seven research papers that discussed peer review and critical thinking. Second, we will summarize and synthesize three articles discussing the role of digital tools during peer review. Lastly, we will discuss the findings of our research and connect them to Swedish upper secondary education context.

4.1 Research on Peer Review’s Effects on Critical

Thinking Skills

Baker (2016) argues that students who partake in a structured peer reviewing process are more likely to make meaningful changes in their revisions (p. 187). Baker (2016)

investigated the timing of feedback, the benefits of structured feedback, and students’ engagement in the revision process. The study entails a text analysis of 91 first-year college students’ production. Furthermore, Baker (2016) structured the assignment into three phases: early submission of essay, delegation of peer review, and examination of essays. The study resulted in three findings. First, having an early deadline on drafts helped students plan and write their paper earlier. Second, structured peer reviewing helped students identify weaknesses in their writing and give meaningful solutions. Third, students made meaningful revisions of their texts (p. 187). Baker (2016) concludes that structured peer assessment helped students develop self-regulation because students who gave high quality feedback made more meaningful revisions to their final paper (p. 188).

Fathi and Khodabakhsh (2019) examined the effects that peer assessment and

self-assessment have on the writing of EFL students in Iran. Furthermore, they compared peer- and self-assessment in relation to the improvements of students’ writing performance (p. 3). They conducted a study including 46 English-major college students in Iran. The

students were divided into two classes where one group assessed their peers while the other group self-assessed. Thereafter, they conducted a pre-test and a post-test for students. Both groups had sessions regarding basic writing instructions about structure and cohesion (p.

13

5). The authors claim that both groups performed similarly during the pre-test. Fathi and Khodabakhsh (2019) found that all students improved after the treatment; however, the peer assessment group improved significantly compared to the self-assessment group. The authors conclude that peer- and assessment can develop a sense of autonomy and self-regulation because peer reviewing helps students to analyze their own writing critically (p. 7).

Babaii and Adeh (2019) compared three different assessment methods to investigate their benefits and helpfulness in developing students’ English writing capabilities. Furthermore, they examined whether giving feedback was more beneficial to learners than receiving

feedback (p. 57). They divided 69 university students from Iran into three classes. The first class received teacher feedback while the second class peer-assessed in pairs, and the third class was divided into groups with one assessor per group. The instructors tested all students’ writing performance on four different occasions. Babaii and Adeh (2019) found that all students developed their writing performance. However, the peer assessment group showed the greatest improvements in writing, communication abilities, and self-regulation (pp. 58-61). Moreover, the authors claim that students who gave feedback outperformed students who only received feedback. Babaii and Adeh (2019) concluded that the reason for the improvements can relate to the process of giving feedback (pp. 61-62).

Kuyyogsuy (2019) examines the effect peer assessment has on developing L2 students’ writing ability (p. 76). The researcher used a mixed-method model where data was collected both quantitatively and qualitatively. The study involved 21 EFL university students from Thailand who were asked to write a narrative paragraph as a pre-test to later peer review. After the peer reviewing process, the students self-reflected on the feedback by writing a self-reflection. The author measured the students’ writing improvements by conducting a post-test (p. 80). Kuyyogsuy (2019) claims that students’ writing ability improved after peer reviewing (p. 80). The improvements were made regarding some writing aspects such as content and structure. Furthermore, the author argues that peer assessment was helpful in improving students’ critical thinking skills such as the ability to self-reflect (p. 82).

Kuyyogsuy (2019) concludes that students become better at critically revising texts due to the peer feedback training they had prior to the post-test (p. 84).

14

peer- and self-assessment. The author conducted qualitative research where she interviewed 21 teacher candidates (p. 50). The teacher candidates created a portfolio that included peer assessment and self-assessment. Lastly, the students evaluated each other’s portfolio anonymously. Bozkurt (2020) learned that most candidates perceived peer- and

self-assessment to be helpful in developing awareness of production weaknesses and evaluation of what is good writing. In addition, Bozkurt (2020) found that candidates learned more about their own writing by comparing it to their peers’. Furthermore, Bozkurt (2020) claims that peer assessment helps facilitate cooperative learning and “critical independent learning” (p. 55). The author found that the candidates expressed frustration regarding lack of objectivity from peers during peer review (pp. 52-54). However, she argues that with peer assessment training, teachers can overcome this limitation because students will be more familiar with the assessment process (2020, p. 57).

Harutyunyan and Poveda (2018) examine whether students perceive peer review as a contributing factor to critical thinking, and whether peer review is helpful in students’ academic writing development (p. 140). The study included 78 university students from Ecuador which were divided into a control group and an experimental group. The experimental group was tasked with writing an argumentative essay and giving formative feedback during the writing processes (pp. 141-142). Harutyunyan and Poveda (2018) found that most students perceived peer review to be helpful in developing evaluation of one’s own text and identifying writing errors. They claim that the peer review group improved their writing in areas such as structure (pp. 144-145). Harutyunyan and Poveda (2018) found that students used the feedback they provided to re-evaluate their own drafts and they referred to their own mistakes while peer reviewing (p. 146). They concluded that students had a positive approach to peer review because they felt confident and

knowledgeable during revision (p. 146).

Hovardas et al. (2013) compare peer feedback with expert feedback, to measure how well secondary school students can produce quality feedback. Secondly, the authors investigated how feedback was used during revision (p. 134). Twenty-eight seventh grade students from Cyprus worked in pairs to write a web-portfolio. Prior to peer reviewing the web-portfolio, students participated in lectures about peer review and assessment criteria. Afterwards, both the students and the experts reviewed and assessed the same web-portfolios. Each group revised the feedback they received from an expert and from a peer’s group (pp.

138-15

139). Hovardas et al. (2013) found that peer-assessors gave less feedback compared to experts on how to make relevant changes. Secondly, they discovered that students gave more positive feedback than the experts (p. 148). The authors further discovered that during revision, students made changes mostly when the feedback from the peers and experts overlapped and, in some cases, students considered their own feedback as well (pp. 146 – 147). Hovardas et al. (2013) argue that using one’s own and other’s feedback in the revision process can develop self-regulation (p. 149).

4.2 Research Findings: Peer Review’s Effects on

Evaluation and Self-Regulation

Peer review is a helpful tool for students to identify and evaluate strengths and weaknesses in their writing. Learners become better at evaluating good writing structure and cohesion when giving feedback (Baker, 2016, p. 87). Fathi and Khodabakhsh (2019) argue that students who gave feedback put more effort into having accurate and justified suggestions, which made the peer-reviewer group more aware of their own writing knowledge (p. 7). They further claim that the peer reviewing process made students more familiar with the writing criteria which in turn improved students’ understanding of cohesive and structured writing (pp. 5, 7). In addition, Harutyunyan and Poveda (2019) learned that students perceived peer review to be helpful in improving their writing in aspects like structure, language use, and cohesion (p. 145). Kuyyogsuy (2019) found similar results: students who were part of the peer reviewing process improved their writing ability in five aspects, two being organisation and content (p. 81). Hovardas et al. (2013) found that high school students were able to provide “structural feedback” similar to the experts’. Moreover, half of the students compared their own feedback to that of the experts. The comparison was later used by the students when writing their revision of the portfolios (p. 145, 149). This suggests that during the peer reviewing and revision process, students tend to evaluate their own writing knowledge to produce helpful feedback and make meaningful edits to their own text (Hovardas, 2013, p. 149).

While the studies are different in their methodology, the researchers found that the process of giving feedback to peers enables students to develop self-regulation and evaluation during the writing process (Baker, 2016; Babaii & Adeh, 2019; Harutyunyan & Poveda 2018; Bozkurt 2020; Kuyyogsuy, 2019). Babaii and Adeh(2019) compared three different methods, one being peer review, to find out the effectiveness of each method, whereas

16

Baker (2016) investigated the benefits of peer review during a four-week period. Both studies found that the process of giving feedback is helpful to students’ self-regulation and

evaluation of their own writing (Baker, 2016 p. 188; Babaii & Adeh, pp. 61-62). Harutyunyan

and Poveda (2018) further found that students perceived the peer reviewing process to be helpful because students were able to evaluate their papers and approach their own texts from a reader’s perspective (p. 147). Bozkurt (2020) instead examined teacher candidates’ perception on the benefits and limitations of peer assessment. She learned that teacher candidates found peer assessment to be useful because they were able to reflect on their own writing and assessment skills. Bozkurt (2020) claims that peer review helps teacher candidates develop teacher skills like self-regulation and evaluation of writing (p. 57).

Kuyyogsuy (2019) adds on by explaining that peer review is an effective pedagogical tool for EFL students to use in their learning because it helps them develop the ability to self-regulate during the writing and the revision process (p. 86). While the studies presented are in agreement regarding peer-review’s effectiveness in fostering self-regulation, Hovardas et al. (2013) found that high school students were unable to produce the same “quality” of feedback as experts (p. 148).

Baker (2016) claims that giving students more time to reflect on their feedback can help students make better revisions (p. 187). Babaii and Adeh (2019) study confirms Baker’s (2016) theory and adds that students who provided feedback performed better in their own revision compared to students who only received feedback (pp. 61-62). In other words, both studies show that by giving students the opportunity to reflect on their writing and provide quality feedback, students can make better revisions in their final drafts.

Hovarda et al.’s (2013) finding brings attention to the importance of training students before making them carry out peer reviews. Baker (2016) argues that for the feedback to be helpful, students need a brief training and explanation on how to provide formative

feedback during peer review. Most researchers in this paper included a peer review training session before students had to peer review independently. In Bozkurt’s study (2020) teacher candidates had to participate in forming a rubric based on their collective understanding of the assessment criteria later to be used during peer review (p. 51). Kuyyogsuy (2019) argues that peer review training is an important factor for students to develop their understanding of formative feedback and to learn more about writing mechanics (p. 86). Baker (2016) and Kuyyogsuy (2019) claim that providing guidance

17

regarding writing prior and during the peer reviewing process can help students give meaningful suggestions to peers. By including proper structure and making students familiar with the peer reviewing process, students learn to trust each other as helpful assessors (Babaii & Adeh, 2019, p. 62). Lastly, Hovardas et al. (2013) argue that training students in the assessor role can be helpful during peer review; however, teachers need to be mindful of the training and scaffolding they provide for students to produce helpful feedback (p. 149).

4.3 Research on Digital Tools’ Role in facilitating the

Peer Review Process

Hojeij and Hurley (2017) investigate how the use of different peer reviewing apps can improve students’ writing (p.1). They examined the effectiveness of digital tools in

providing guided peer- and self-assessment while studying the usefulness of comments and annotations. The study involved 32 EFL university students that were divided into two groups, each consisting of 15 and 17 participants. First, each student received input on their essays through Powtoon videos; second, they peer reviewed each other by using Notability, and thirdly, they published their edited essays in Edmodo. The authors found that most students had a positive experience using digital tools during peer review. Hojeij and Hurley (2017) claim that students were thorough in their revisions before posting their texts online (p. 4). The authors concluded that most students preferred Edmodo because they were able to provide feedback using comments and they learned to notice their writing mistakes by peer reviewing (p. 3).

Kayacan and Razı (2017) examine the effect of anonymous peer review while using digital tools by comparing 46 high school students’ first and final drafts (p. 562). Two groups wrote an opinion essay using Edmodo as the peer review platform (p. 565). Both groups had peer review training before providing feedback. While one group had to peer review the first two assignments, the second group self-reviewed their texts. Thereafter, for the last two assignments, the groups swapped learning methods. Kayacan and Razı (2017) found that anonymous peer review performed better compared to self-review while using digital tools. However, they argue that both methods showed a significant improvement from the first to the last draft (pp. 567-568). Kayacan and Razı (2017) claim that students’ perception of anonymous peer review on Edmodo was mostly positive because it allowed them to be objective when peer reviewing. They concluded that students increased their

18

awareness of how technology can be used to develop their writing (p. 571-572).

Sharp and Rodriguez (2020) investigate the use of software programs to learn about how they affect the instructional phase of peer review learning and the extent of technology tools’ helpfulness for peer reviewing (p. 2). The study was conducted using two groups where one group of 44 students used Eli Review as their peer review platform and the second group of 33 students used either Word or Google Docs. Prior to the feedback activity, both groups were instructed to apply a specific feedback model (pp. 3-4). Sharp and Rodriguez (2020) found that students who used Eli Review provided useful feedback regarding content and clarity. The second group, using Word or Google Docs provided helpful feedback regarding APA use and rewording suggestions (p. 6-7). Lastly, Sharp and

Rodriguez (2020) conclude that the digital tool should be accessible and familiar for both the instructor and the students for it to be helpful in the peer reviewing process (pp. 9-10).

4.4 Research Findings: Digital Tools’ Role in

facilitating the Peer Reviewing Process

Digital tools can enable students to access and interact with each other’s text online and in class, which helps facilitate the peer reviewing process (Kayacan & Razı, 2017, p. 564). Hojeij and Hurley (2017) learned that students perceived the digital environment as an engaging and innovative way to interact with peers’ texts. Furthermore, working in a collaborative digital environment helped students notice their own writing errors (p. 3).

Sharp and Rodriguez (2020) found that some software tools can be used for different functions. Their study shows that students who used Eli Review provided mostly feedback on content, citation, and clarity while students who used Word or Google Drive gave feedback that focused on APA use and rewording suggestions. However, Sharp and

Rodriguez (2020) explain that teachers’ different assessment criteria did affect the feedback students provided (pp. 7-8). Hojeij and Hurley (2017) claim that students found Edmodo useful because the discussion platform allowed students to comment and interact with peers. Moreover, they argue that students found the authenticity of publishing on Edmodo motivating and made them revise their texts thoroughly before posting it (p. 3). The three studies show that digital tools increase interaction between students during the peer reviewing process and improves accessibility to students’ production (Sharp & Rodriguez, 2020; Kayacan & Razı, 2017; Hojeij & Hurley, 2017).

19

Teachers can make use of digital tools to make the peer reviewing process anonymous. Anonymous peer reviews help students to be objective while peer reviewing which in turn helps them evaluate their own knowledge of writing (Kayacan & Razı, 2017, p. 573). Kayacan and Razı (2017) claim that students had a positive outlook on digital anonymous peer review as it allowed them to give objective feedback to fellow students (p. 572). Moreover, Hovardas et al. (2013) suggest that anonymous chat rooms can improve

communication between students and instructors (p. 149). Furthermore, Kayacan and Razı (2017) claim that anonymous peer reviews helped students improve their writing skills in aspects like content and grammar (p. 569).

Regardless of the chosen software, teachers need to have clear, structured guidelines and peer assessment criteria for students to follow. Moreover, the digital tool should be

accessible and familiar to the students and teachers for it to be useful in the peer reviewing process (Sharp & Rodriguez, 2020; Kayacan & Razı, 2017; Hojeij & Hurley, 2017). Sharp and Rodriguez (2020) found that for one of the instructors, a lot of time was put on learning the functionality of Eli Review while the other teacher was already familiar with Word and Google Drive which gave the teacher more time to plan the assignment (pp. 5-6). Furthermore, the authors explain that even though each student group used a specific software for their assignment, all students managed to apply the peer assessment criteria they received from their teachers (p. 8). Hovardas (2013) concludes that teachers need to support the students during the peer reviewing process whether they are using digital tools or not (p. 149).

20

5. Discussion

5.1 Peer Review Can Develop Critical Thinking Skills

The benefits of peer review have been discussed in numerous studies. Instead, this paper has focused on the benefits of peer review in relation to critical thinking skills, particularly

self-regulation, and evaluation. These skills are relevant for EFL students because by practising

these skills, the students improve their writing, autonomously. The Swedish syllabus for English 5, 6, and 7 states that students should be given the opportunity to write and evaluate different types of texts. Skolverket (2013) describes the importance of developing students’ critical thinking skills, confidence, and curiosity because this will be their foundation for lifelong learning (Skolverket, 2013, pp. 5-6). Furthermore, Harrison et al. (2015) express the importance of making learners autonomous while reviewing their writing. This study found that there is a consensus between researchers about developing critical thinking skills when giving feedback to peers (Baker, 2016; Babaii & Adeh, 2019; Harutyunyan & Poveda 2018; Bozkurt 2020; Kuyyogsuy, 2019). Despite the different ways of examining the benefits of peer review in EFL and English-speaking countries, the studies show that students who engaged in peer reviewing —especially in providing feedback — had to reflect upon their

peers’ writing and their own feedback which developed students’ writing. Furthermore, peer review enabled students to revise their text to make it more cohesive and logical (Harutyunyan & Poveda, 2018). Moreover, teacher candidates expressed that peer

assessment helped them reflect on their own ability to provide useful feedback and evaluate their writing knowledge (Bozkurt, 2020). However, for the peer reviewing process to be helpful, it is important to consider including clear guidelines and training sessions prior to engaging students in peer review (Hovardas, 2013). In addition, Baker’s (2016) finding shows that students make better revisions when they have more time to reflect on the feedback they received (p. 187). This research has shown that there are multiple benefits in including peer review in the writing process for the development of critical thinking skills. Peer review is deeply rooted in social learning theory because it requires a collaboration between two or more learners. The studies show that peer review enables the possibility for students to interact with each other’s work to improve their own language learning.

Skolverket encourages teachers to include collaborative activities between students and engage their learning in social settings, which is in line with Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory.

21

Vygotsky emphasized the importance of engaging students in social interactions; it is an important aspect of cognitive learning because it enables learners to share their knowledge by communicating and collaborating with each other (Hojeij & Hurley, 2017, p. 2). The peer reviewing process can enable students to challenge each other’s thoughts and ideas regarding different writing components like structure, content and/or language use. When comparing self-assessment with peer review, it was clear that the students who engaged in peer review performed significantly better in their final drafts (Fathi & Khodabakhsh, 2019; Babaii & Adeh 2019). This finding affirms the idea that students make better revisions after collaborative efforts than they would do independently. The studies showed a pattern of using ZPD since the instructors considered the students English proficiency level and used peer review as a strategy to develop students’ writing by engaging them in a social setting with essential guidelines to help them through the writing process. This resulted in students improving their ability to reflect and evaluate their production by collaborating and

interacting with each other (Baker, 2016).

In the syllabus for English 5, 6, and 7, Skolverket requires that students learn how to process others’ and their own written and oral production (Lgy11). Furthermore, Babaii and Ayler (2019) found that students who engaged in peer reviewing improved their writing significantly. This result was common across all ten research papers since they found the peer reviewing process to be useful for the students, if structured properly. Similarly to Baker’s (2016) finding about giving time for students to reflect on the received feedback, Skolverket argues that students should be given time to reflect on their own learning and make use of different learning strategies (Lgy11). Furthermore, Skolverket suggest that teachers should give students the opportunity to produce and evaluate different types of text.

Despite that most participants from the different studies were from higher education level, the studies and theories presented are in line with Skolverket’s requirements and can work well with Swedish upper secondary students. This is because by comparing the common European framework for English, we can see that Swedish students’ English proficiency rates high compared to other EFL learners (EF English Proficiency Index, 2020).

Furthermore, some of the studies done on EFL classrooms found it challenging to engage students in peer reviewing because students saw the teacher as the one having all the knowledge and that their fellow peers could not help them (Babaii & Ayler, 2019;

22

the national curriculum, which emphasizes the importance of creating a safe and trusting environment for students to make use of each other's different knowledge and experiences.

5.2 Digital Tools Can Help Facilitate the Peer

Reviewing Process

The reviewed studies support the use of digital tools in the peer reviewing process and describe a variety of benefits that emerge when including these tools in the writing process. In Swedish classrooms, digital tools have mainly been used as a replacement for pen/paper since they are mainly used for writing essays, searching information, and making

presentations (Almén et al., 2020, p. 290). However, Skolverket (2011) suggests that students should make use of different digital tools to develop their language learning (Lgy11). Studies have shown that the use of digital tools—such as Edmodo, Eli Review, Google Drive, and Word—can facilitate the peer reviewing process by improving students’ interaction with each other’s texts (Sharp & Rodriguez, 2020, p. 8). Moreover, Hojeij and Hurley (2017) argue that digital environments are helpful in the writing process because it enables learners to notice their own errors and communicate them by using comments and annotations. Students expressed that working with Edmodo motivated them to be aware of their errors while revising their texts, before posting them on the website (Hojeij & Hurley, 2017, p. 3). Another benefit of using digital tools is the function of anonymous peer review. Kayacan and Razı (2017) argue that anonymous peer review helped students be objective when peer reviewing which in turn enabled them to reflect on their feedbacks’ accuracy. Thus, digital tools can promote language learning through peer review, which is in line with the Skolverket’s requirement for developing students’ English language learning.

The findings show that digital tools are appreciated during peer review; however, for the tool to be useful, teachers and students need to be familiar with its functions and it needs to be accessible for the user. Hojeij and Hurley (2017) learned that students were not comfortable using Notability because they had to pay for the software and the functions were not easy to use. On the other hand, students found Edmodo to be easier to access because it was free and engaging (p. 3). In addition, Sharp and Rodriguez (2020) explained that Eli Review was time consuming because the teacher was not familiar with the software (pp. 5-6). Lastly, there is an agreement between the authors that when using digital tools in the writing process, it is important that there are clear guidelines about the peer reviewing

23

process and the assessment criteria to make the process accessible to the students (Hojeij & Hurley, 2017; Kayacan & Razı, 2017; Sharp & Rodriguez 2020).

24

6. Conclusion

To conclude, we examined and evaluated ten studies about the benefits of peer review in relation to critical thinking skills (in particular, evaluation and self-regulation) and the extent to which digital tools can be used to help students in the peer review process. The findings show that the process of giving feedback can help students reflect on their own knowledge of writing. Furthermore, engaging students in peer review can help them identify and evaluate their writing strengths and weaknesses. This added knowledge can help them become better at self-regulating their revisions and evaluate others’ and their own writing. However, it is important to include a structured peer review training before students are tasked with giving each other feedback. These findings imply that students can develop critical thinking skills in a social setting where they learn from each other’s

knowledge and experiences, which comply with the learning theories recommended in Swedish upper secondary education. Furthermore, the findings provide more context to the Swedish curriculum because they explain how beneficial peer reviewing can be in developing critical thinking skills and writing skills.

For our second research question, the findings show that digital tools can improve interaction and accessibility to students’ production, which complies with Skolverket’s recommendation to encourage collaboration between students. The learners found it easier to notice mistakes and communicate with each other using the comment section and annotations. Moreover, the anonymity function when using digital tools was helpful since students were able to be objective in their assessment. However, the chosen software should be familiar and easy to access for students and teachers. In addition, teachers need to have clear instructions on how to peer review no matter what software they use. Currently, digital tools in Swedish classrooms are mainly as a replacement for traditional tools such as paper/pencil. Therefore, it is important that teachers find innovative ways to include accessible software programs in the peer reviewing process because it can engage students in their writing progression.

It is important to acknowledge that most of the studies were for university students and, in a few cases, for secondary education. A second limitation was regarding the contexts of the studies. Most of the studies were in school cultures that are vastly different to the Swedish school culture. Some of the students in the studies perceived their teacher to be the main

25

source of knowledge and almost dismissed their peer’s feedback. This raises the question of whether the studies would have shown a different result if conducted with Swedish upper secondary students.

Therefore, for future studies, it is worth investigating how peer review can develop

Swedish students’ critical thinking skills in upper secondary education. In addition, it would be useful to examine how different digital tools can engage students in the writing process

—especially during peer reviewing and revision. This can be examined by instructing

approximately ten randomly chosen students to write a short expository paper to later peer review it, using Google drive and/or Word. Students will learn more about how to give formative feedback prior to peer reviewing independently. During their training period, they will be asked to peer review a short paragraph as an example. The chosen students will be from English 6 as they are more likely to know how to write an expository text. This is an important factor because it will reserve time for the peer reviewing activity. After peer reviewing, they will have time to reflect on the received feedback to compare it to their own produced feedback. Finally, to track students’ approach of giving and using feedback, students will be asked to record their screens during the peer review and revision process.

26

References

Almén, L., Bagga-Gupta, S., & Bjursell, C. (2020). Access to and Accounts of Using Digital Tools in Swedish Secondary Grades. An Exploratory Study. Journal of Information

Technology Education, 19, 288-310.

Accessed: https://doi.org/10.28945/4550

Babaii, E., & Adeh, A. (2019). One, Two,..., Many: The Outcomes of Paired Peer Assessment, Group Peer Assessment, and Teacher Assessment in EFL Writing.

Journal of Asia TEFL, 16(1), 53-66.

Accessed: http://dx.doi.org/10.18823/asiatefl.2019.16.1.4.53

Baker, K. M. (2016). Peer Review as a Strategy for Improving Students’ Writing Process.

Active Learning in Higher Education, 17(3), 179-192.

Accessed: https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787416654794

Baran-Łucarz, M. (2019). Formative Assessment in the English as a Foreign Language Classroom in Secondary Schools in Poland. Report on a mixed-method study. The

Journal of Education, Culture, and Society, 10(2), 309-327.

Accessed: https://doi.org/10.15503/jecs20192.309.327

Berridge, E. (2009). Peer Interaction and Writing Development in a Social Studies High School Classroom, 5-38.

Bozkurt, F. (2020). Teachers Candidates’ Views on Self and Peer Assessment as a Tool for Student Development. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 45(1), 47-57.

Accessed: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ajte/vol45/iss1/4

Burner, T. (2015). Formative Assessment of Writing in English as a Foreign Language.

Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 60(6), 626-648.

Accessed: https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2015.1066430 EF EPI 2020, EF English Proficiency Index

Accessed: https://www.ef.com/ca/epi/

Facione, P. A. (1992). Critical thinking: What it is and Why it Counts. Insight Assessment.

California Academic Press, 102, 53-66.

Fathi, J. & Khodabakhsh, M. R. (2019). The Role of Self-Assessment and Peer-Assessment in Improving Writing Performance of Iranian EFL Students. International Journal of

27

Fredriksson, C. (2019), Elevrespons – elevers samarbete i skriftlig produktion. Stockholm: Skolverket.

Grönlund, A. (2020). Forskningsöversikt om formativ bedömning väcker frågor. Stockholm: Skolverket.

Accessed:

https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/forskning-och- utvarderingar/forskning/forskningsoversikt-om-formativ-bedomning-vacker-fragor

Harrison, K., O'Hara, J., & McNamara, G. (2015). Re-Thinking Assessment: Self-and Peer-Assessment as Drivers of Self-Direction in Learning. Eurasian Journal of Educational

Research, 60, 75-88.

Accessed: https://doi.org/10.14689/ejer.2015.60.5

Harutyunyan, L., & Poveda, M. F. (2018). Students' Perception of Peer Review in an EFL Classroom. English language teaching, 11(4), 138-151.

Accessed: https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v11n4p138

Hojeij, Z., & Hurley, Z. (2017). The Triple Flip: Using Technology for Peer and Self-Editing of Writing. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning,

11(1), 1-4.

Accessed: https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2017.110104

Hovardas, T., Tsivitanidou, O. E., & Zacharia, Z. C. (2013). Peer Versus Expert Feedback: An investigation of the Quality of Peer Feedback Among Secondary School

Students. Computers & Education, 71, 133-152.

Accessed: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.09.019

Kayacan, A., & Razı, S. (2017). Digital Self-Review and Anonymous Peer Feedback in Turkish High School EFL Writing. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 13(2), 561-577.

Kuyyogsuy, S. (2019). Promoting Peer Feedback in Developing Students' English Writing Ability in L2 Writing Class. International Education Studies, 12(9), 76-90.

Accessed: 10.5539/ies.v12n9p76

Popov, O. (2016). Förmåga att tänka kritiskt. Stockholm: Skolverket. Accessed 2020-12-23: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:umu:diva-124631

Samuelsson, J. (2020). Formativ bedömning kan forma kritiskt tänkande. Stockholm: Skolverket. Accessed:

https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/forskning-och-utvarderingar/forskning/formativ-bedomning-kan-forma-kritiskt-tankande Sharp, L. A., & Rodriguez, R. C. (2020). Technology-Based Peer Review Learning

28

Activities among Graduate Students: An Examination of Two Tools. Journal of

Educators Online, 17(1), 1-12.

Skolverket. (2011). Subject – English [Syllabus]. Accessed 2020-12-23:

https://www.skolverket.se/undervisning/gymnasieskolan/laroplan-program-och-amnen-i-gymnasieskolan/amnesplaner-i-gymnasieskolan-pa-engelska

Skolverket. (2013). Curriculum for the Upper Secondary School: Lpgy 13. Stockholm. Accessed: https://www.skolverket.se/getFile?file=2975

Wang, Q., & Woo, H. L. (2010). Investigating Students’ Critical Thinking in Weblogs: An Exploratory Study in a Singapore Secondary School. Asia Pacific Education Review,