Challenges in the Eco-tourism Industry in

Santa Teresa, Costa Rica

A field study aimed at investigating eco-tourists’ opportunities

for traveling sustainably

Utmaningar inom Eko-turism Industrin i

Santa Teresa, Costa Rica

En fältstudie med syfte att undersöka eko-turisters möjligheter

för hållbart resande

Bengtsson, Hanna & Folkeryd, Felicia

Environmental Science Bachelor's degree 15 hp

May 2017

Abstract

A certain responsibility is accompanying the substantial impact which the tourism industry is generating. The impacts are constantly expanding due to the growing population, globalization, and economic welfare. An emerging discussion about the challenges to develop sustainable tourism is not only important but also imperative, especially in countries which are dependent on tourism as their main source of income. This field study is founded on the theoretical framework of eco-tourism which is built on the debate regarding if the eco-tourism industry can be sustainable. The data collected is based on qualitative methods, using mainly semi-structured and informative interviews along with observations in Costa Rica in the village of Santa Teresa. The purpose of the field study was to investigate eco-tourism and the tourists’ opportunities to travel sustainable in Santa Teresa. Specifically, the study strived to identify attributes that are hindering the eco-tourists from traveling sustainably. The main study object were, according to the Costa Rican Certification for Sustainable Tourism (CST), the industry's main factors, the sustainable behaviour of the tourist and the strong infrastructure of the host country. The findings of the field study aim to contribute with relevant information on how to locally improve practices to reach a sustainable development of eco-tourism in Santa Teresa. The result revealed a shortage in adequate opportunities for the tourist to travel sustainable according The International Ecotourism Society (TIES) criteria for being an eco-tourist. Factors were identified to be insufficient infrastructure, due to the suddenly emerging influx of tourists as well as the Costa Rican governments stagnation and inability to approach the subsequent consequences. Even though, indications also showed a willingness to improve the industry. In order to assure a sustainable development in Santa Teresa, and further Costa Rica, such negative attributes need to be addressed in order to handle the intangible and tangible tourism in this ongoing growing context.

Key words

Eco-tourism, opportunities, limitations, infrastructure, sustainable behavior, Santa Teresa (Costa Rica).

Sammanfattning

Ett visst ansvar medföljer den omfattande inverkan som turism har på den globala omgivningen. Effekterna industrin genererar utökas kontinuerligt på grund av den rådande befolkningstillväxten, globaliseringen och det medföljande ekonomiska välståndet. För en långsiktig hållbar utveckling av eko-turism industrin krävs det att de existerande utmaningarna uppmärksammas, vilket är nödvändigt, framför allt i länder vars primära inkomstkälla utgörs av turism. Följande fältstudie är grundad på ett teoretiskt ramverk som har sitt ursprung från problematiken gällande om det är möjligt att föra en framgångsfull eko-turism industri utan att generera negativa konsekvenser. Studien är kvalitativ och utgörs av semi-strukturerade och informativa intervjuer tillsammans med observationer utförda i Costa Rica, men främst i orten Santa Teresa beläget i Costa Rica. Fältstudien syftar till att studera eko-turism samt att undersöka vilka förutsättningar det finns för en turist att resa hållbart i Santa Teresa. Vidare, avser studien till att identifiera de brister som försvårar turistens möjligheter till hållbart resande. För att ta reda på detta var studiens främsta fokus att studera enligt Certification for Sustainable Tourism (CST), industrins två viktigaste faktorer, turisternas beteende och Santa Teresas hållbara erbjudande. Studiens resultat avser att bidra med information som kan stärka industrin och bidra till en positiv och hållbar utveckling. Resultatet av fältstudien identifierade en diskrepans mellan turisternas förutsättningar till att resa hållbart och The International Ecotourism Society (TIES) kriterier för att resa som en eko-turist. Bristfälliga faktorer som identifierades, tolkades bero på en ineffektiv infrastruktur, vilket i sin kan vara ett resultat av den snabbt ökande tillkomsten av turister till orten. Den rådande situationen har resulterat i att arbetet med turismens konsekvenser har stagnerat på grund av otillräckliga resurser. Bland den identifierade komplexitet av industrin, kunde fältstudien identifiera en vilja bland industrins involverade aktörer att föra hållbara beslut men vilka begränsas av en otillräcklig infrastruktur. För att möjliggöra en hållbar utveckling av eko-turism i Santa Teresa behövs industrins negativa faktorer uppmärksammas och åtgärdas.

Nyckelord

Eko-turism, möjligheter, brister, infrastruktur, hållbart beteende, Santa Teresa (Costa Rica).

Acknowledgments

First of all we want to thank the Swedish International Development and Cooperation Agency (Sida) for giving us the opportunity to conduct our field study in Costa Rica. Besides all the information we received for our thesis, our field study in Costa Rica has provided us with knowledge and memories that have strengthen us, not only in our profession but also as individuals.

We would also like to thank our supervisor Jonas Alwall. Your feedback has repeatedly calmed us down when we got confused. We admire your way to teach and how you really put yourself into it.

Thanks to all of you who kindly helped us forward in our study process. Hotel Tropical Latino and hotel Nautilus Boutique, we really appreciate that you allowed us to use your hotel area while we were searching for respondents to interview. We want to thank Jessica, the owner at hostel Rio Carmen in Santa Teresa where we spend the most of our time writing our thesis in “our” beloved hammocks. Thank you for providing us with valuable knowledge of Santa Teresa and got us in contact with people that helped us widen our knowledge about our research object. Furthermore, we are grateful to all our respondents, who generously agreed to provide us their time during their vacation. We have learned so much from you!

Our field study has mainly provided us with positive experiences. Still, it was inevitable not to experience some less positive moments. So last but not least, we want to thank you as a reader, for always doing your best in protecting the people around you and the earth that provides you your home.

Concept definitions

Anthropocentrism: Refers to a philosophical viewpoint arguing that human beings are the most

central or most significant entities on the planet.

Deep ecology: A holistic approach where the central idea is that humankind is part of nature, as

opposed to the existing worldview where individuals see themselves as separated from nature.

Ecocentrism: Refers to a philosophical viewpoint that holds that ecological collections such as

ecosystems, habitants, species and populations are the central objects for environmental concern.

Free riders: The stakeholders who benefit from common resources, collective goods and

services without acting according to the rules or pay when everyone else pays.

Lower-income countries: A nation or a sovereign state with a less developed industrial base and

a low Human Development Index (HDI) relative to other countries in the world.

Tikka/Tikko: The local term for a Costa Rican male (tikko) or female (tikka).

Tipping points: Refers to the increasing human pressure on ecosystems where the usage of

scarce and finite resources is causing the earth to approach boundaries or “tipping points” that, once crossed, may lead to fundamental changes is the earth’s system dynamics which could be difficult to remediate.

Triple bottom line: A unifying concept of sustainable development and focus on its economic,

social and ecological aspects. The combination of these three dimensions refers to the sustainability of sustainable development.

Greenwashing: Is a concept used in tourism and means, that by using green market strategies

with the economic purpose to attract more visitors to destinations and not by actually perform to minimize environmental impacts.

Contents

1.0 Introduction

……….………...…….………..11.1 Eco-tourism and its Impacts……….………..…….……….……….……1

1.1.1 The eco-tourist………...……..………..………...1

1.1.2 Eco-tourism: Ecology and Economy………..………..……….………...3

1.2 Costa Rica and Minor Field Studies ………...…...………...….….…....……….4

1.2.1 Eco-tourism and sustainable development in Costa Rica……….…….……..…….5

1.2.2 The Minor Field Studies……….………..…….6

1.3 Problem Statement, Purpose and Research Questions……….….………..……8

1.3.1 Problem statement and purpose of the study……….……..…….…..…8

1.3.2 Research questions………..….………..………..…...…….………..9

1.3.3 Delimitations of the study…….….………..………..…...…….………..9

2.0 Theoretical framework

…..……….….…...…………112.1 The social exchange theory: the interactions of tourism………..………..…11

2.2 Marxism and economic exploitation…………...……….…………..…13

2.3 Shallow and deep eco-tourism……….….………..14

2.4 Ecological Citizenship and Ecological Footprint………..……….………..………16

3.0 Methodology and research strategies

………..………....………...……183.1 Minor field study in Costa Rica……….………...18

3.1.1 Introducing Costa Rica...……….………..………..………...18

3.1.2 Introducing Santa Teresa...……….………..………..………...20

3.4.1 Preparations………...…...…….………20

3.2 Design, method and research process……….………...……….………..…20

3.2.1 An ethnographic approach……….………..………...……...………20

3.2.2 Semi-structured interviews……….……….………..……21

3.2.3 Complementary questionnaire to the semi-structured interviews……...……….……23

3.2.4 Informative interviews……...……….………...………..….….…...……23

3.2.5 Observations………...………...………..….……24

3.2.6 Analyzing process……….………...……24

3.3 Sample selection………...……….………...…………....25

3.3.1 Sample selection of the semi-structured interviews………..……...…....25

3.3.2 Sample selection of the informative interviews……….…...………26

3.5 Ethical considerations………..…….26

4.0 Empirical findings and analysis

………...………...…...………284.1 Local effects of tourism in Santa Teresa ……….………...…….…………28

4.1.1 Social structure challenges………29

4.1.2 Recycling and waste disposal………...………...…30

4.1.3 Water management………...……...……31

4.2.1 Transport opportunities………....………33

4.2.2 Consumption opportunities………..………..………...36

4.2.3 Waste management………..…………...………39

4.3 The interplay between the tourist’s environmental values and actions………..….…41

4.4 Tourists’ perceptions and expectations of Costa Rica……….………...………...…44

5.0 Discussion and concluding remarks

………...………465.1 The opportunities for being an eco-tourist in Santa Teresa………..…...…46

5.2 The discrepancy between the tourists’ values and actions ……..………....………..48

5.3 Reflections of the field study……….……….….…….…49

5.5 Considerations of the result………...……….…...…51

6.0 References

………..………...………...………...537.0 Appendix

………..………...…………..……56 Appendix 1………...………...56 Appendix 2………...………...……57 Appendix 3………...………...………59 Appendix 4………...………....…60 Appendix 5………...………....…611

1.0 Introduction

The purpose of this chapter is to make the reader familiar with the phenomenon of

eco-tourism, how it is exercised by eco-tourists and the development of eco-tourism in Costa Rica. The chapter will shed light on the debate over the tourism industry’s negative and positive impacts and how they are related to sustainable development, particularly in Costa Rica. Consequently, the chapter aims to provide the reader with knowledge in order to understand the problem statement and the main study object of the field study, the eco-tourists.

1.1 Eco-tourism and its impacts

Unlike other industries, tourism contains and relies on multiple products and services from different suppliers such as travel agencies, hotels, restaurants and airlines in order to provide the finished product of a vacation experience (Christou, 2006 & Gössling, Hansson, Hörstmeier, & Saggel, 2002). Tourism provides opportunities for development as well as creating relationships and cultural understanding (Gössling, 2002 & Lemos, Fischer, & Souza, 2012). In addition, research has shown that low-income countries should encourage the expansion of tourism, partly because tourism related developments have shown to be correlated with poverty reduction (Lemos et al., 2012). However, the industry faces numerous kinds of challenges such as balancing the dimensions of the so-called triple bottom lines: the ecological, the economic and the social. Since the beginning of the 1960s, environmental awareness and tourism have become linked together (Jones & Spadafora, 2016), and it has become obvious that tourism presents not only advantages but also problems.

1.1.1 The eco-tourist

The essential factor of eco-tourism is the eco-tourist, a person who travels with an awareness Introduction Theoretical framework

Method and research strategies Empirical findings and analyze Discussion and concluding remarks

2 about the effects of the global tourism industry and acts upon that awareness to transform the industry in a sustainable manner (Spadafora, 2016). Moreover, the Costa Rican Certification for Sustainable Tourism (CST) defines the tourist, together with a strong infrastructure, as the industry’s most important players in order to reach a sustainable development of the industry (Visitcostarica, n.d.).

One step towards ensuring eco-tourism’s endurance is to establish a better-informed traveling public. Contemporary travelers can, with a bit of research and planning, find destinations for eco-tourism around the world (Honey, 2008, Ch. 5). The International Ecotourism Society (TIES) is a non-profit organization dedicated to promoting eco-tourism which states that the concept is uniting three main criteria: conservation, communities and sustainable travel (Ecotourism, 2017). To support the traveling tourists and concerned organizations in following sustainable practices, TIES has developed a set of basic criteria of actions (The International Ecotourism Society, 2015):

1. Minimize physical, social, behavioral, and psychological impacts. 2. Build environmental and cultural awareness and respect.

3. Provide positive experiences for both visitors and hosts. 4. Provide direct financial benefits for conservation.

5. Generate financial benefits for both local people and private industry. 6. Deliver memorable interpretative experiences to visitors that help raise sensitivity to host countries' political, environmental, and social climates. 7. Design, construct and operate low-impact facilities.

8. Recognize the rights and spiritual beliefs of the Indigenous people in your community and work in partnership with them to create empowerment.

In order for tourists to act as eco-tourists, as suggested by TIES criteria (Ecotourism, 2017), tourists need awareness and receptiveness regarding the meaning of the concept of eco-tourism. Awareness, in order to know that there exists a different way of acting when traveling, and receptiveness of the concept to be able to commit to actions and values of being an eco-tourist (Budeanu, 2007). Even though tourists have a positive attitude towards being an eco-tourist, research shows that there is just a fraction who act accordingly by consuming responsibly, recycling and using environmentally friendly transport. The discrepancy between a tourist’s values and actions is stated to be one of the main barriers in the development of sustainable tourism (Budeanu, 2007). Research has shown that tourists’ choice of action when

3 travelling could lead to significant improvement in terms of waste management, resource consumption and transport optimization (Upham, 2001 & Budeanu, 2007). However, many tourists choice of actions remains a disadvantage for the industry of eco-tourism because the lack of engagement of the makes it harder to convert the conventional tourism into becoming eco-tourism (Martens and Spaargaren, 2005). Still, there is a small fraction of tourists who act upon their positive attitude toward sustainable tourism, and there are some tourists who do it occasionally and some who never do it. One could distinguish the different tourists from each other in order to understand the differences (Acott, Trobe & Howard, 2010). Being an eco-tourist could be exercised on different levels of deepness or eco-eco-tourists could be categorized based on different levels of pro-environmental behavior, depending on how often they act upon their environmental values and why they do it (Acott, et al., 2010, Budeanu, 2007). A

shallow eco-tourist would be defined as someone who acts as an eco-tourist when it is

suitable with a cursory engagement and would be categorized as one with a lower level of pro-environmental behavior. An eco-tourist on a deep level would be an individual who possesses a more intrinsic engagement for acting as an eco-tourist, and would be categorized with a high level of pro-environmental behavior (Acott et al., 2010 & Gössling, 2002 & Martens & Spaagaren, 2005). More of shallow and deep eco-tourism and the categorization will be explained in chapter 2.3.

1.1.2 Eco-tourism: Ecology and Economy

The ongoing debate regarding the complex definition of sustainable development and how to achieve a long-term development has been discussed since the concept of sustainable development was established in 1987 (Barkemeyer, Holt, Preuss & Tsang, 2014). Sustainable development aims to maintain the present needs of the triple bottom line without compromising the preconditions for future generations (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987). Sustainable development could be achieved by preventing irreversible tipping points such as exploitation and degradation (Steffen, et al., 2015). Today, eco-tourism is one of many tools for reaching a sustainable development (Gren & Huijbens, 2014). Therefore, the global expansion of eco-tourism and associated cause-effects is highly related to the challenges with sustainable development: balancing the economic growth with the social and the ecological aspects (Gren & Huijbens, 2014 & Horton, 2009). Since the rise of eco-tourism, numerous definitions of the concept have been discussed. The Costa Rican Certification for Sustainable Tourism (CST) summarizes eco-tourism as follows:

4

The development of sustainable tourism must be seen as the balanced interaction between the use of our natural and cultural resources, the improvement of the quality of life among the local communities, and the economic success of the industry, which also contributes to national development. Sustainable tourism is not only a response to demand, but also an imperative condition to successfully compete now and in the future (Visitcostarica, n.d.).

As CST summarizes, a balanced interaction between the economic growth and the use of natural resources is essential to maintain a sustainable development in the tourism industry (Visitcostarica, n.d.). A country like Costa Rica is highly dependent on the economic growth generated by the tourism industry in order to develop (Gren & Huijbens, 2014). In order for that development to succeed in the long term, it will need to be aligned with a sustained usage of natural resources to avoid being exploited and degraded, which will endanger the capability of having tourism as the nation’s main source of income.

1.2 Costa Rica and Minor Field Studies

The following sections introduce and describe the history, the development and the meaning of eco-tourism in Costa Rica. Moreover, it provides an introduction to our Minor Field Study and how we experienced it, such as difficulties and changes that occurred when conducting the field study. Finally, the problem statement, purpose and research questions of the study will be presented.

1.2.1 Eco-tourism and sustainable development in Costa Rica

Tourism is estimated to be Costa Rica’s main source of income followed by agriculture and export of electronic devices (Horton, 2009). The economic activity tourism generates has an important value for Costa Rica, like it has for other countries which are involved with tourism activities. The World of Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC) is the global authority on the economic and social contribution of the travel and tourism industries and has divided the industry's main contribution effects into two areas: employment and Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The total contribution of tourism to employment in Costa Rica was in 2014 calculated to estimate twelve percent of the country’s total employment (247,500 jobs) (WTTC, 2015). The effects on the employment is further estimated to rise by 13 percent to (330,000 jobs) in 2025. GDP is a monetary measure of the market value of all final goods and services produced in one year and is commonly used to determine the economic performance of a

5 country. The total contribution of tourism to the GDP was 12.5 percent in 2014, and is forecasted to rise by 13.2 percent of GDP in 2025 (WTTC, 2015).

The eco-tourism industry was mainly introduced in Costa Rica by Americans who came to study the biological riches or enjoy the peaceful society (Van der Duim & Philipsen, 2002). They brought ecological ideas, and together with biologists and environmentalists from Costa Rica they helped to spread these ideas widely (Jones & Spadafora, 2016). At the same time as the industry grew, the government was spurred into developing nature conservation programs (Groen, 2002). The first eco-tourism establishment in Costa Rica was in 1963 followed by the creation of the first national park in 1971 (Honey, 2008, Ch. 5). Between the 1970s and the 2000s Costa Rica was forced into a new beginning due to the changes that followed the expansion of tourism in the country (Jones & Spadafora, 2016). Tourists visiting the country increased from 435,000 in 1990 into 1.1 million in 2000 with revenues generated by tourism growing from US$21 million to US$1.15 billion. Furthermore, it was estimated that half of the tourists visited protected environmental areas (Jones & Spadafora, 2016). The increasing trend kept growing and in 2011 around 2.2 million tourists visited Costa Rica, which is equivalent to 51 percent of the country's total population at the time (National Institute of Statistics and Census of Costa Rica, INEC, 2013). This tourism expansion made Costa Rica a leading destination for eco-tourism (Horton, 2009) and it continued to be the largest source of income in the country (Walter, 2013 & Horton, 2009). Eco-tourism now earns more foreign exchange than the nation’s former staple exports - bananas, pineapples and coffee - combined (Departamento de Estadísticas ICT, 2006).

Besides the economic benefits eco-tourism offers Costa Rica, it also offers job opportunities to the locals, environmental education to travelers, funds for ecological conservation and political empowerment of local communities (Dasenbrock, 2002 & Horton, 2009). Due to the country's stability and openness to foreigners it has encouraged a lot of entrepreneurs, domestic as well as foreign (Jones & Spadafora, 2016). However, eco-tourism is constantly sustained in conflicts regarding priorities. Even though the upsurge of tourism generated positive effects on the society, it also brought negative impacts affecting the society, people and nature that put a lot of pressure into the local stakeholders to solve these issues. Meanwhile, a destination like Santa Teresa struggles with maintaining tourism as their main source of income, handling the consequences of the industry and at the same time protecting their position of being a destination for eco-tourism. The money tourism generates becomes a source of conflicts in communities between environmentalists and companies eager for profit, combined with immigrants without papers who are being employed in the

6 tourism sector (Jones & Spadafora, 2016). Furthermore, if tourism is poorly managed, it poses potential threats to natural resources where proper management can prevent excessive exploitation and degradation (Beeton, 2006, Ch. 3; Jones & Spadafora, 2016 & Horton, 2009).

Given the sustainability goals of eco-tourism, it is easy for skeptics to criticize the industry, claiming that the scarce ecosystems cannot be adequately protected by a profit-oriented business (Cheong & Miller, 2000 & Duffy, 2002, Ch. 1). These critics may argue that natural areas should be strictly preserved, rather than open to the public. This exemplifies the challenge of prioritizing, where arguments are primarily used as an economic justification for environmental preservation, because it serves to preserve artifacts that are demanded by the tourists (Christou, 2006, p 4 & Honey, 2016).

The Departamento de Estadísticas (ICT) is a governmental agency in Costa Rica that has been guiding the tourism industry since 1931 (it changed its name from National Tourism Council in 1951). Besides being responsible for granting numerous fiscal incentives, the agency is foremost known for promoting sustainable tourism in Costa Rica (Jones & Spadafora, 2016). In order to obtain and develop the sustainable tourism-sector, Costa Rica introduced a voluntary Certification for Sustainable Tourism (CST) program in 1997 (Visitcostarica, n.d.; Jones & Spadafora, 2016 & LePree, 2008-2009). CST focuses mainly on improving the industry's most visible factors such as hotels, gastronomy, and marketing. They are also paying attention to factors such as security, attractions, environment, local communities, and training, among others (Visitcostarica, n.d). CST has been successful and recognized by the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) as a program in the forefront in making tourism more sustainable. The CST has been important to Costa Rica in order to differentiate their tourism from other destinations and moreover to prevent greenwashing in the eco-tourism industry (LePree, 2008-2009 & UN, 2016).

1.2.2 The Minor Field Study

The Swedish International Development and Cooperation Agency (Sida) is a government agency working with the mission to reduce poverty in the world. Through the Minor Field Study (MFS), which is a Sida funded scholarship, we were able to conduct our field study in the low-income country, Costa Rica. With our combined interest in traveling and sustainability, studying eco-tourism in Costa Rica was a given choice. Costa Rica is stated to be a destination where eco-tourism is an established attraction, which is the main reason for

7 the country's rapid growth and development. Through secondary sources, we received a understanding of the general issues the industry is contributing with.

We chose to conduct our study in the village Santa Teresa, located in Nicoya Peninsula in Costa Rica (see map in appendix 5). Santa Teresa is stated to be a destination where eco-tourism is an established attraction, and since the eco-tourism boom hit Santa Teresa in the 1990’s, the village has experienced a tremendous growth and development. Except for eco-tourism, the village attracts visitors due to its diverse nature and wildlife, and its opportunities for surf and yoga. Our primary focus before arriving in Santa Teresa, and as described in our MFS application, was to examine the tourism industry in Santa Teresa and seek an answer to the question if an economy built on tourism could be sustainable. However, we could not predict what difficulties we would face during our field study. As we had anticipated, when situated in Costa Rica, we quickly discovered the great complexity in the field and due to the limit of time of our field study, we understood that we would be unable to identify all the effects that emerged through eco-tourism. Therefore, instead of trying to identify the total effects arriving from the industry, our objective would focus on identifying the main difficulties of the industry, hindering a sustainable development of eco-tourism. As will be further presented in the purpose of the study (section 1.3.1), our investigation derives from the statement of CST: the most important factors in the eco-tourism industry is presented to be the sustainable behaviour of the tourist and the strong infrastructure of the host country (Visitcostarica, n.d.). As the sustainable values of tourists often fail to match their actions, we realized the importance of a combined sustainable tourist behaviour and a strong infrastructure to reach a successful eco-tourism industry (Budeanu, 2007). Therefore, we wanted to investigate eco-tourist’s opportunities for traveling sustainably. Through semi-structured interviews we investigated the correlation between their sustainable values and actions in order to identify the behaviour of the tourists while traveling.

As intended, through our qualitative approach, we built a greater understanding of the eco-tourism industry in Santa Teresa, mainly through conducting observations and interviews. To broaden our knowledge and straighten the uncertainties we still had, we traveled around in Costa Rica (further explained in Ch. 3). The field study brought us new knowledge, mostly, we concluded the fact that issues in a low-income country require a lot of work to solve. We realized that improvements of Costa Rica's regulations and infrastructure needed to be applied regarding areas such as waste and water management, as well as transport and consumption opportunities. We noticed a discrepancy between tourists’ environmental values and their actions and saw a correlation between the need of action from the government of Costa Rica

8 to apply strategies that provided the tourists more sustainable options to make it easier for them to travel sustainably. A further introduction of the Minor Field Study process and a more detailed description of the study location - Costa Rica and Santa Teresa - is presented in sections 3.1, 3.2 and 3.3.

1.3 Problem Statement, Purpose and Research Questions

1.3.1 Problem statement and purpose of the study

In the developing country Costa Rica, tourism reigns as the nation's top enterprise and largest employer (Horton, 2009) and according to ICT, nearly half of the international travelers that are visiting Costa Rica participate in eco-tourism (Departamento de Estadísticas, 2006). Besides the economic benefits of ecotourism, it also offers job opportunities to the locals, environmental education to travelers, funds for ecological conservation and political empowerment of local communities. However, tourism poses potential threats to many natural areas. It can create great pressure on local resources like energy, food, and other raw materials that may already be short in supply (Horton, 2009). By allowing unlimited numbers of tourists into protected areas and encouraging the construction of high-rise hotels and resorts over small-scale tourism development, ecotourism industries can lead to a lot of damages on the ecosystems (Cheong & Miller, 2000). Given the environmental goals and social ideals of eco-tourism, it is easy for skeptics to criticize the industry, claiming that the world’s delicate ecosystems cannot be adequately protected by a profit-oriented business (Duffy, 2002).

The village Santa Teresa is stated to be a destination where eco-tourism is an established attraction and is the main reason for its rapid growth and development. Since the tourism boom hit Santa Teresa in the 1990’s, the village has experienced a tremendous growth and development. After the year 2000 the full-time residents living there went from just 100 people to between 2000 and 3000 (Vivatropical, 2017). Even though the industry has generated many positive benefits to the local community, both financially and socially, the negative impacts the industry is generating are constantly expanding due to the growing population, globalization, and economic welfare. The big amount of tourists visiting Santa Teresa in a short amount of time, have put a lot of pressure of maintaining a strong infrastructure in the village. Furthermore, eco-tourism has generated different kinds of negative impacts on the environment by causing disruption to both the natural habitat and its wildlife (Budeanu, 2007).

9 The consequences of eco-tourism are essential to address in order to reach improvement and develop the industry towards a sustainable future. The difficulties of the industry also depend on the choice of actions of the tourists, who, moreover, are determined by the given opportunities at the destination (Budeanu, 2007). Therefore, our study strives to take a deeper look at eco-tourism in Costa Rica and thereby facilitating a clearer understanding of the complexity of this phenomenon. In order to do so, the study seeks to identify attributes that are hindering the eco-tourists from traveling sustainably. The approach was to identify limitations in the eco-tourism industry in Santa Teresa by examining its crucial factors as the sustainable behaviour of the tourist and the strong infrastructure of the host country. The final result of the field study is based mainly on the tourists' perception of whether Santa Teresa, as a stated environment-friendly destination, gives the tourists the adequate opportunities to travel according to the TIES criteria of being an eco-tourist. Moreover, the findings of the field study seeks to contribute with information regarding which practices that needs to be applied and in what areas, to strengthen the sustainable development of the eco-tourism industry in Santa Teresa.

1.3.2 Research questions

The field study will ultimately attempt to answer this fundamental question:

- Do tourists’ experiences a discrepancy between the provided opportunities and the ability to act as eco-tourists when traveling to Santa Teresa, Costa Rica?

To conclusively answer this question, the following questions needed to be resolved:

- What attributes usually define the typical eco-tourists in Santa Teresa, in terms of their actions and values while traveling?

- What characterizes Costa Rica, as given in the example of Santa Teresa, as a destination of eco-tourism in terms of the capability to exercise eco-tourism and the existing efforts being made?

1.3.3 Delimitations of the study

Due to the field study’s time limit, some delimitations had to be applied. The sample of respondents was preceded at uncertified hotels. This choice was based on the fact that there

10 was only one CST certified hotel in the area. The chosen hotels were implementing environmental efforts in various areas that were promoted on their websites, available for the conscious tourists to receive information about. However, without the measurements and structure that certification programs provide, there are no certainties that the environmental efforts performed by the non-certified hotels are properly executed. Because of this, there is a risk that the field study's reliability is flawed. The field study is limited to examine tourists’ stay in Costa Rica, not outside the country. The airplane flight and other potential impacts are therefore excluded from the field study.

11

2.0 Theoretical framework

In this chapter, the theoretical frame of reference will be established and consists of theories related to eco-tourism. The concept of eco-tourism will be examined as well as related opportunities to travel as an eco-tourist. The framework for this chapter will highlight academic discussions on the different interpretations of eco-tourism according to our chosen typological framework. The chapter will first address the push and pull factors which describes the comprehensive driving forces of tourism. Afterwards, the Theory of Social Exchange will clarify the social dimension of tourism followed by the economic aspect by using economic exploitation to continuously problematize the social impacts of tourism. Furthermore, the concepts of deep and shallow eco-tourism will be highlighted to demonstrate the subsequent complexity when eco-tourism is exercised. The concept of shallow and deep will then be applied on the eco-tourists combined with a categorization for different levels of pro-environmental behavior to further explain significant artifacts that motivate a visitor to act as an eco-tourist will be highlighted in terms of behavioral opportunities regarding the tourist industry. The concepts permeate the study and moreover, are of importance to the outcome of the study (in chapter 4). Last, the Ecological Citizenship and the Ecological Footprint will explain the behavior of a tourist and why they behave as they do. We believe that these theories and concepts combined provide a solid foundation to the investigation and discussion about how the opportunities for eco-tourism in Costa Rica and foremost Santa Teresa are performed.

2.1 The social exchange theory: the interactions of tourism

Dann (1977) developed a theory attempting to explain tourists’ motivation when traveling based on investigations regarding why people travel, significant driving forces when choosing where to go and what the choices are based on. Dann (1977) concluded that a range of

socio-Introduction Theoretical framework

Method and research strategies Empirical findings and analyze Discussion and concluding remarks

12 psychological motives and intrinsic reasons drives the wanderlust of an individual, which he names push factors. Factors could be a desire to escape, the need for a break, the hedonistic value of a travel experience as well as the willingness to experience. Dann (1977) also determined the pull factors by observing individuals’ decision-making process of where to go. Among pull factors are appealing artifacts of a certain destination that the individual is seeking in a vacation experience for example weather, beaches, recreation, activities or natural scenery. It was found that the pull factors were correlated with merchandising activities of the tourism industry which results in a retrospective influence of the tourist (Beeton, 2006, Ch. 5). Given the above, it is safe to conclude that many tourists who decide to go on a vacation are more likely to end up on a conventional vacation, due to the lack of promotion of eco-tourism and the existing insufficient knowledge about environmentally friendly vacations among most individuals (Beeton, 2006, Ch. 5 & Budeanu, 2007). This is one of the factors which enables the concept of eco-tourism from growing to the needed extension (Beeton, 2006, Ch. 5). But still, it is hard to elude the remaining impacts an expanding industry would generate, sustainably or not sustainably, which creates questioning about the protectionist and conservationist model that eco-tourism is based on. Dann (1977) and Beeton (2006, Ch. 8) also draws attention to the relationship between the residents (locals) and visitors (tourists). It is recognized that without the support of local stakeholders, tourism would not be successful in the long term and their interactions are therefore significant to understand (Beeton, 2006, Ch 8 & Gössling, 2002).

George Homans (1974) developed The Social Exchange Theory which provides an overview of the relationship. The theory describes what occurs when two cultures interact and how the initiation of information exchange is preceded (Nunez, 1989). If the exchange is positive between the residents and the visitors, a relationship is established; if the exchange is negative, one or both participants may attempt to withdraw from the process. The outcome of the exchange is based on what kind of contact the interaction created, the socioeconomic characteristics, class distinctions, size in both populations and the equity between the cultures (Nunez, 1989). This exchange is evident when visiting low-income countries. Western society, which is the primary source of tourists, tends to demonstrate the inequality by having a higher education and income than the inhabitants on the destination. This can easily result in so-called acculturation which means that the less dominant culture, the residential, starts to take on characteristics of the dominant culture of the guests and generate a cultural loss of what the visitors came to experience in the first place (Beeton, 2006, Ch. 2). Further consequences, such as the demonstration effect could also become an actuality whereas locals

13 desire to imitate the western society, creating willingness to demand western commodities. In this sense, tourism development could be called counterproductive; it carries within itself the potential tipping point of its own destruction, one of the primary paradoxes of tourism (Beeton, 2006, Ch. 2). To exemplify, popular destinations that previously consisted of numerous pull factors becomes degraded due to overcrowding and overdevelopment and leads to declining numbers of tourists visiting as well as economic earnings (Honey, 2016). Pull factors, like tourists’ willingness to experience the authenticity of a country, risks contributing to create a destination they will despise (Dielemans, 2014).

2.2 Marxism and economic exploitation

The hermeneutic development, spurred from Marxism, criticizes and questions the domination of western society in many fields, tourism included. Previous research explains that the level of social and cultural empowerment in a person’s surrounding has a significant meaning for the pro-environmental behavior (Dobson, 2003, Ch. 3 & Scott Arnold, 1995, Ch.1). Marxism describes a society consisting of inequality of power and distribution which will generate a class distinction as well as a disconnection in the community. The pivotal problems with class distinctions and disconnection derives from the fact that larger groups of people are exploited by smaller and dominant groups (Dasenbrock, 2002 & Gössling 2002). In terms of tourism, in which involved societies are often dependent on the income from tourism, the larger group is represented by the working residents in the host country and the dominating group is the visiting tourists. A tourism-dependent society is formed and adapted to fulfill the needs of the dominant group in order to attract visitors and generate income. Marxism promotes a society that is extricating from previous statement and supports the pursuit of an equal, classless society (Allwood & Eriksson, 2010 & Scott Arnold, 1995, Ch. 1). Dobson (2003, Ch. 3) argues that eco-tourism could operate as a positive factor in the existing class-based society in terms of the Marxist concept of economic exploitation. Economic exploitation is a concept spawned from the methodology of Marxism and aims to involve welfare and revenues in a society which is proceeding towards exploitation and to illuminate the relationship between the capitalist (the tourist) and the worker (the resident) (Scott Arnold, 1995, Ch. 3). As stated before, tourists’ purpose for visiting a destination is based on different push and pull factors which are inevitably affecting the dimensions of the triple bottom line and could divert focus from the well-being of the local population (Dasenbrock, 2002; Duffy, 2002, Ch. 3 & Gössling, 2002). In order to minimize these effects,

14 the principles of economic exploitation states that it is important that the right price is paid which will benefit the nation’s economic and social preconditions (Bonnedahl, 2012, Ch. 3). Eco-tourism is determined to be more expensive than conventional tourism, which results in fair trade and decreasing class distinctions (Dobson, 2003, Ch. 3 & Dasenbrock, 2002) but is challenged by the limiting factor of tourists’ access to financial resources to choose to go on a responsible vacation (Budeanu, 2007).

2.3 Shallow and deep eco-tourism

Since the rise of eco-tourism in Costa Rica, the industry has continued to grow along with the promotion of natural resource preservation and sustainable development (Budeanu, 2007). The creation of Costa Rica’s image of a natural paradise enabled many businesses that were not acting sustainably to free ride on the green image (Jones & Spadafora, 2016). The lack of environmental interest in free riding businesses creates a discrepancy and detract the ability for tourists to make environmentally friendly choices (Gössling, 2002 & Jones & Spadafora, 2016). To separate the operative businesses that free rides from the environmentally benign, the concepts of deep and shallow eco-tourism could be applied (Acott, Trobe & Howard, 2010). The concepts aim to clarify the disparity between positive and negative impacts of eco-tourism, where deep eco-tourism is positive and shallow eco-tourism is negative. The latter is closely related to green washing, meaning the use of green market strategies with the purpose to attract more visitors to tourist places (Gundter, Ceddla & Tröster, 2017). The criteria for shallow eco-tourism could be summarized as an anthropocentric approach, where nature is rated based on its usefulness to humans and where monetary profits are prioritized over the wellness of the cultural or ecological resources (Acott et al., 2010). Honey (2016) phrases the term of shallow eco-tourism as lite eco-tourism, and describes how associated businesses works with minimal environmental remembrance, cost-effective earnings such as not washing sheets and towels every day which implies that they seem to be sustainable even though they do not take their fully ecological responsibility (Honey, 2016). On the contrary to the shallow approach, deep eco-tourism is based on the conception of ecocentrism and deep ecology, focusing on the importance of the intrinsic value in nature, community identification and participation and remote materialism, large-scales as well as mass consumption (Acott et al., 2010). Gundter et al. (2017) means that the advantages of eco-tourism only will be generated through deep eco-tourism, which Honey (2016) states is both exceptional and often imperfect. Hence, that clarifies the two sides of Costa Rica’s green profile stigmatization whereas the

15 level of deepness of the exercised eco-tourism often get criticized; one side implies that the green profile is in the sense of greenwashing and on the other side that the green profile has an intrinsic value for the country. There are reasons for questioning the different levels of sustainability in eco-tourism, but regardless, the meaning of the concept aims at achieving something good. The concept of deep and shallow eco-tourism gives the complexity of tourism substance and is a generalized approach when studying the industry and has been used as an underlying framework throughout the study.

The efforts of the eco-tourist in terms of deep and shallow eco-tourism

The efforts of reaching Costa Rica's sustainability goals shows that there are encouraging signs that tourists provision can be improved by a shift in demand in terms of resource consumption, waste management and transport optimizing (Budeanu, 2007 & Upham, 2001). Research shows the lack of response regarding sustainability among most tourists. Only a minimal percentage of the tourists seem to be acting accordingly to their values regarding sustainability and possess only a cursory interest in understanding a culture or the impacts of their behavior (Acott et al., 2010; Gössling, 2002 & Martens & Spaagaren, 2005). The majority of tourists could therefore be mentioned as shallow eco-tourists. The deep eco-tourist would on the contrary recognize the intrinsic value in nature and search for meaningful understanding to obtain extended knowledge (Acott et al., 2010). However, on the other hand, shallow eco-tourists have intrinsic reasons for not behaving according to sustainable practices (Budeanu (2007). Henceforth, a deep eco-tourist has a holistic motivation and would not call for western comfort if that would have a negative influence, the person in question should be prepared to conserve resources in the same way that host populations do and would want to eat local food instead of foreign cousin (Acott et al., 2010). A shallow tourist is influenced by an anthropocentric purpose and want to experience untouched nature without the perception of attending impacts. Further they want to experience and help maintain nature preservation but at the same time participate in activities that is contradictory to their values. Shallow and deep eco-tourism is determined through analyzing attitudes, values and behavior which reflects tourists’ underlying environmental sensibilities (Acott et al., 2010). Horner and Swarbrooke (2016, Ch. 5) implies that tourists could be categorized in three groups, depending on their level of pro-environmental behavior: the green, who are inclined to act on behalf of others, the brown, who are ambivalent to such issues and the grey, who are not interested in the well-being of others. This categorization is further used throughout the thesis as a complement to the concept of shallow and deep eco-tourists. To ensure eco-tourism’s

16 survival and to push towards a deep eco-tourism development, quality information should be spread to the traveling public, along with stronger economic incentives such as taxes and fees to inspire environmental behavior combined with the usage of marketing power (Budeanu, 2007).

2.4 Ecological Citizenship and Ecological Footprint

To target the importance of an individual pro-environmental behavior and to understand characteristics of such behavior the theory of Ecological Citizenship (EC) could be helpful (Sverker & Martinsson, 2010 & Jagers & Martinsson, 2009). Dobson (2003, Ch. 3) founded this theory which states that all human beings should have the equal right to use provided resources, with an emphasis on doing so responsibly. The theory aims on secure a sustainable Ecological Footprint (EF). Dobson (Ch. 3, 2003) definition of the concept of EC and EF is as followed:

...The Ecological Citizen will want to ensure that her or his Ecological Footprint does not compromise or foreclose the ability of others in present and future generations to pursue options important to them” (Dobson, 2003, p. 120).

Dobson (2003, Ch. 3) highlights the emerging importance of environmental rights in the citizenship context in order to create positive change in behavior and attitudes. Seyfang (2006) exemplifies the aim of the theory by saying that EC creates environmental responsibility and incentive to change behavior through the attending awareness of an individual’s impacts on its surrounding. The EC clarifies the materializing relationship between the individual and the environment which illuminates the EF which in turn clarifies the relationships with affected parties (Dobson, 2003, Ch. 3). All living beings rely on the products and services of nature and by analyzing the EF it enables to estimate resource consumption and waste assimilation requirements of a human population as well as define the environmental impacts of the triple bottom line. Due to the multinationality of environmental problems, the impact could be far away or closely to the origin of the problem (Gössling et al., 2002 & Jagers & Martinsson, 2009). Our impact on the environment is related to the quantity of nature that we use in our consumption patterns. What kind of citizen you are depends on your attitude towards obligation, awareness, moral responsibility and participation (Dobson, 2003, Ch. 3). What kind of tourist you are is correlated with personal safety preferences, motivations, culture and race as well as what kind of surrounding population you

17 are exposed to (Budeanu, 2007). These attributes reflect in the individual behavior of the tourist.

The theory of EC together with the concept of deep eco-tourism describes the need for collective action among individuals in order to bring about notable change (Acott et al., 2010; Dobson, 2003, Ch. 3). Operators whose environmental engagement is integrated into their companies’ principles, could be affected by the influx of less environmentally aware individuals. Therefore, it is important for responsible vacation operators to offer experiences as good and accessible as those of conventional vacation suppliers (Budeanu, 2007). This exemplifies the difficulties of a sustainable tourism development whereas operators which are environmentally benign compete for inexperienced international customers, with shallow operators (Acott et al., 2010 & Jones & Spadafora, 2016). The preferences of a tourist impact the available supply and contribute to defining the destination and how to distribute its resources (Albaladejo, & Martínez-García, 2013). The difficulties created by ecological damage are due to the lack of adequate tools (Dobson, 2003, Ch. 5 & Seyfang, 2006) and a multidisciplinary understanding of how attitudes, personalities and lifestyles influence a tourist’s choice (Budeanu, 2007). But even if a tourist would have a positive attitude towards eco-tourism the majority do not comply with the criteria of an eco-tourist because of obstacles such as unavailability, lack of time and that being an eco-tourist is less comfortable (Budeanu, 2007 & Legget, Kleckner, Boyle, Dufield, & Mitchell, 2003). To summarize, to be able to travel responsibly, tourists’ need to be given the right external opportunities combined with an internal environmental sensibility and attitude.

18

3.0 Method and research strategies

This chapter aims to explain the research strategy of the thesis. Chosen design, research process and methodological considerations such as location, respondents, data collecting and analyzing process will be presented. The chapter will firstly provide an introduction of the field study and the study location, were the research was executed. This includes a brief description of preparations that were of importance before travel to the study location.

Furthermore, each method conducted during the field study will be presented and last, ethical considerations that were taken into account during the field study are discussed.

3.1 Minor field study in Costa Rica

Minor Field Studies (MFS) is a Sida funded scholarship program aimed to give Swedish students the opportunity to acquire knowledge concerning low-income countries and development. Through Sida we were able to conduct our study in Santa Teresa located on Nicoya Peninsula in Costa Rica (see map in appendix 5). The fieldwork lasted for eleven weeks between the 28th of February until the 14th of May 2017. An introduction of the study location will be presented below to provide the reader a fuller understanding of the study object and affecting factors of the study.

3.1.1 Introducing Costa Rica

Costa Rica is a small low-income country located in Central America with a population of five million people (Svenska FN-förbundet, 2014). Compared to its surrounding neighbors, Costa Rica differs by having the best social welfare system and living conditions in Central America. According to The Human Development Index (HDI), who operates to assess long-term progress in three basic dimensions of human development: a long and healthy life, access to knowledge and a decent standard of living, in year 2015, Costa Rica reached a value of 0.776, on an index ranging from 0 to 1, where 0 is the lowest value and 1 is the highest

Introduction Theoretical framework

Method and research strategies Empirical findings and analyze Discussion and concluding remarks

19 (United Nations Development Programme, n.d.). In addition, Costa Rica was once again assigned the first place among 140 countries at the Happy Planet Index (Happyplanetindex, n.d.). HPI is an index that proves how well nations are to achieving long, happy and sustainable lives, meaning that Costa Rica is one of the happiest, if not the happiest country in the world.

Costa Rica is mostly linked to its outstanding nature that despite the country's small surface of only 1.03 percent of the world's landmass, they are still estimated to contain five percent of the world's biodiversity (Honey, 2008, Ch. 5). Their various nature and wildlife has developed the country into one of the world’s biggest eco-tourism destination (Budeanu, 2007 & Stronza & Gordillo, 2008). The country has long been perceived as one of the most sustainable countries in Central America as well as the world, and a role model of environmental protection such as reforestation efforts, which has resulted in a duplication of the forest cover in less than 20 years (Hsu & Johnson, 2014 & Happyplanetindex, n.d.). In addition, the government of Costa Rica makes priorities of investing in renewable energy in order to achieve their aim of becoming carbon neutral by 2021.

The Environmental Performance Index (EPI) provides a global view of a country’s environmental performance. In 2016 Costa Rica was ranked to be number 42 out of 180 countries, measured in more than 20 environmental indicators (EPI, 2016). The recent results of EPI, Costa Rica received the lowest ranking yet in 2014, when they went from being ranked as 5 out of 132 (year 2013) countries to 54 out of 178. The reason for the downgrading in performances was due to the inclusion of a new index indicator, wastewater treatment. The table below presents an overview of Costa Rica's EPI from 2016 where nine different issues are categorized.

20

3.1.2 Introducing Santa Teresa

Santa Teresa is a small town, located in the southwestern corner of Peninsula de Nicoya in Costa Rica (see map in appendix 5). With its various surrounding nature and supply of activities, sights and mix culture the village attract a lot of visitors. (Fallon, Gleeson, Harding, Hecht, Masters, Spurling, Vidgen & Vorhees, 2016). The pacific coastline makes the destination essential for surfers. Many visitors are also drawn by the large variety of yoga experiences (Alexander, 2012). Furthermore, a Costa Rican expression that essentially embodies the tikko philosophy of enjoying life peacefully in a strong community, an element of simplicity and an appreciation of one’s natural surroundings is often refereed to as Pura

vida (Alexander, 2012). The pura vida philosophy defines Santa Teresa and is said to be one

of the reasons why the area is one, among five other places in the world that has been assigned as a blue zone (Poulain, Herm & Pes, 2013). A blue zone is describes as a limited area where the inhabitants shares a lifestyle and the environment, combined with an unusually high proportion of long-lived individuals. Studies have shown that significant factors to obtain this long life span is: reduced level of stress, consumption based on locally produced food and a strong elderly support from the community and family (Poulain et al., 2013).

3.4.1 Preparations

Through the Minor Field Study program we participated in a four-days introduction course before we went to Costa Rica, located at Sida’s headquarters in Härnösand, Sweden. The course acquired knowledge about low-income countries, development issues and further discussion about the possible contradictions and outcomes while performing our field study in Costa Rica. Further, to prepare and widen our knowledge of our field study, research through secondary sources such as news and scientific articles and books were conducted. This preparatory knowledge supported better possibilities to overcome possible adversities while performing the field study in Costa Rica. In addition, we established contact with Travel Excellence, a travel agency based in San Jose, Costa Rica, to further ease eventual adversities.

3.2 Design, method and research process

3.2.1 An ethnographic approach

As Russell (2006, Ch. 10) implies that the choice of method is best decided based on what matches the needs of the research, we found the most suitable approach of methods for this study to be qualitative. Dilthey (1989, Ch. 1) distinguishes in his interpretation of the separate

21 forms of science by relating the qualitative approach to understanding. To reach an understanding of the eco-tourism industry in Santa Teresa and seek an answer to the research question of the study, we choose to incorporate different types of qualitative methods. The methods that were used during the field study were semi-structured interviews with tourists living at hotels with sustainable approaches. After each semi-structured interview an accompanying questionnaire was conducted to confirm the data collected from the interview. Furthermore, to widen our understanding of the eco-tourism industry in Santa Teresa, informative interviews with stakeholders in the eco-tourism industry and underlying observations were performed during the eleven weeks of field work in Santa Teresa. These methods and the research process will be further discussed in the following sections below.

3.2.2 Semi-structured interviews

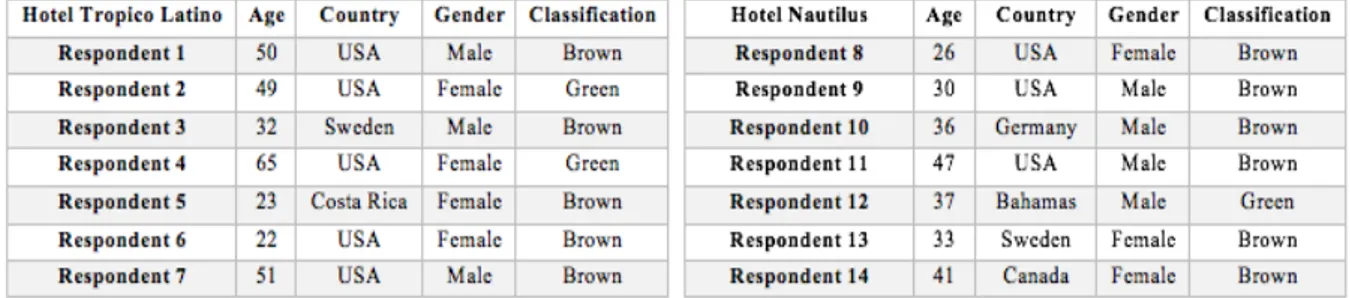

The primarily executed method of the field study is interviews with semi-structured questions to tourists in Santa Teresa, due to Alvehus (2013, Ch. 3) perception of “interviews to be an almost indispensable method of trying to find out how people think, feel, and act in different situations”. The purpose behind interviewing these tourists’ was to examine their experience of the possibilities to travel eco-friendly in Santa Teresa and furthermore to identify differences between their sustainable values and actions. 14 semi-structured interviews with tourists that stayed at two different hotels with a sustainable approach were conducted. The sample of selection is further described in section 3.3 and the hotels in Appendix 1.

Design of the questions to the semi-structured interviews

Rapeley (2004) means that the process of finding respondents and setting up interviews is central to the outcomes of the research. The process of making an orderly interview questions was therefore a priority. The questions were mainly based on the criteria of being an eco-tourist according to TIES (The International Ecotourism Society, 2015), which strived to ascertain the impacts of tourism and if the tourists correspond to the criteria of acting sustainably while traveling in Santa Teresa. Based on these criteria together with our own experience and pre-knowledge, the semi-structured questions were divided in different themes, were we perceived the tourist were most likely to engage in while traveling which was correlated with situations that might had an impact on the eco-tourism industry. The questions that were used in the semi-structured interviews were circled around those themes and are following: the tourist, choice of hotel in Santa Teresa, activities, transport, food,

22 consumption, waste, the expectations of Costa Rica as a destination for vacation and the perspective of tourism (all questions are presented in appendix 2).

Kahneman (2003) asserts that methods, useful for avoiding biased answer are largely missing out in tourism research. Furthermore do Dickinson and Dickinson (2006) state that when asking tourists about their behavior in hypothetical situations, it may trigger positive answer, meaning, that the response gives a good impression but are less truthful. To respond to this criticism and avoid ending up with less reliable results, efforts was executed to avoid biased answers. Therefore, questions related to subject such as environmental issues was avoided.

Performance of the semi-structured interviews

On site, at the two hotels (mentioned in sample selection of the semi-structured interviews 3.3.1 and in appendix 1) the guests were asked if they wanted to participate in an interview about tourism. To prevent influencing the outcome of the interviews, all information except that it was about tourism was excluded. The interviews were performed immediately or later if desired. The duration time of each interview varied between 50 to 80 minutes and was executed in the restaurant area of the hotels. Russell (2006, Ch. 9) informs the importance of not relying on your memory while interviewing. To secure the data of the interviews, they were recorded through two different iPhone units. Further Russell (2006, Ch. 9) adds that recording is not a substitute for taking notes. Technical problems can occur and your information can easily get lost. Factors like body language of the respondent or suddenly conclusions of the interview may appear that you would not perceive on the recorder. To avoid such outcome, one of the interrogators performed the interview while the other was held in the background, taking notes of important emphases or body language of the respondent.

The semi-structured questions were primarily open wishing to comprehend the respondent’s view of their reality. The approach was to let them talk as much as possible without being led by the interrogator. According to Russell, (2006, Ch. 9) who claims that the key to successful interviewing is to learn how to probe effectively, we used different probe-techniques in order for the respondents to develop their answers. The probe-probe-techniques used in the interviews were mainly the silent probe and the tell-me-more probe (Russell, 2006, Ch. 9). Depending on the situation, we either remained quiet and waited for the informant to continue or probed to encourage the respondents to elaborate the answer. Due to the variation of people's different requirements in and how they want to be approached, we responded on