Planning for Physical Activity in

Public Open Spaces

Insights from Malmö and Copenhagen

Sandro Vita

Sport Sciences: Two-Year Master’s Thesis, IV610G, 30 ECTS Sport Sciences: Sport in Society

VT/2020

Supervisor: Karin Book Examiner: Johan R. Norberg

Abstract

The urban population of cities world-wide is steadily growing, causing pressure on land use for different purposes, such as residential, commercial, or recreational use. A growing urban population will also create new public health challenges, especially due to the epidemic increase of Non-Communicable Diseases. Creating opportunities for and increasing physical activity in public open spaces could represent a crucial resource to tackle health problems of urban residents. This multiple case study explores the strategies and approaches of two case cities (Malmö and Copenhagen) in connection to planning for physical activity in public open spaces and the collaborative efforts behind it. The empirical material for the study consists of 9 interviews with professionals connected to urban planning from the municipalities of Malmö and Copenhagen. The collaborations between urban planners and other actors were analysed using collaboration theory. Various barriers and facilitators of collaboration were identified, as well as findings which can suggest more fruitful collaboration.

Table of Content

Abstract ... 2

List of Figures ... 5

1 Introduction ... 6

2 Previous Research ... 8

2.1 Urban Planning Terms and Definitions ... 8

2.2 Urban Planning and Health ... 9

2.2.1 Urban Planning and Health – An Ambivalent Relationship... 9

2.2.2 Health Risks of Cities ... 10

2.3 Urban Planning and Physical Activity ... 12

2.4 Physical Activity and the Built Environment (PABE) Research ... 15

2.4.1 What is PABE Research? ... 15

2.4.2 PABE Research – What? How? and by Whom? ... 16

2.4.3 Issues of PABE Research and Implications for Further Research ... 21

2.5 Urban Planning Collaborations ... 22

3 Aim and Research Questions ... 27

3.1 Problem Statement ... 27 3.2 Research Aim ... 27 3.3 Research Questions ... 28 4 Theoretical Framework ... 29 4.1 Theory of Collaboration ... 29 4.1.1 Definition ... 29 4.1.2 Conceptualisation of Collaboration ... 31 5 Methodology ... 38 5.1 Research Design... 38 5.2 Empirical Data ... 39

5.3 Data Collection Techniques ... 41

5.4 Methods of Analysis ... 44

5.5 Research Quality ... 46

6 Results – Presentation, Interpretation and Conclusions ... 50

6.1 Malmö ... 50

6.1.1 Program för Aktiva Mötesplatser ... 50

6.1.2 Collaborative efforts ... 53

6.2 Copenhagen... 61

6.2.1 Blue Areas – A Harbour of Opportunities ... 63

6.2.2 Green Areas – Urban Nature Strategy ... 65

6.2.3 Collaborative Efforts ... 66

6.2.4 Conclusion ... 71

6.3 Conclusion ... 72

7 Discussion ... 74

7.1 Reflection on Process of Thesis ... 74

7.2 Implications for Practice and Future Research ... 76

8 References ... 78

9 Appendices ... 91

9.1 Example of Initial Contact Email ... 91

9.2 Interview Consent Form: ... 92

List of Figures

Figure 1: Conceptual framework for the relation between urban and transport planning,

environmental exposures and health... 10

Figure 2: Factors influencing physical activity in communities... 14

Figure 3: Conceptual model for park characteristics and physical activity ... 21

Figure 4:Antecedents – Process – Outcomes Framework ... 36

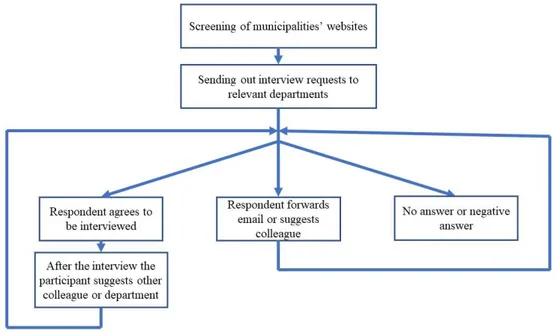

Figure 5: Illustration of Data Collection Procedure ... 42

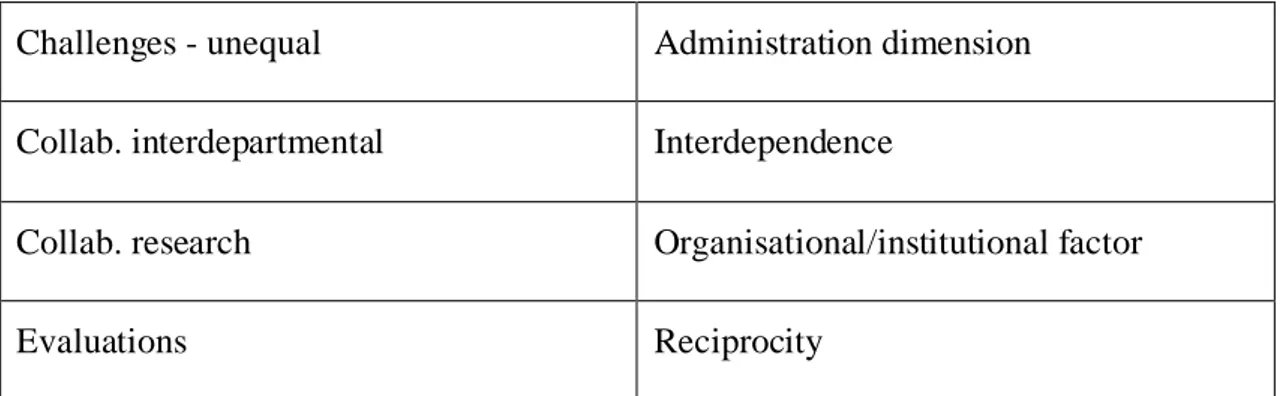

Figure 6: Examples of primary-cycle codes and secondary-cycle codes from software Nvivo ... 46

1 Introduction

Today, 55% of the world’s population lives in urban areas and the urbanisation – the process by which people move from rural areas to urban areas – is increasing. According to a UN report (2018) experts estimate that by 2050, 68% of the world’s population will be living in urban areas, and 80% of the European population. In Europe 74% of the population is already living in urban areas. Due to that, many European cities have adopted sustainable city growth plans. Whether through spatial expansion or densification, higher population in urban areas will bring new challenges to the preservation of public health, especially because of the epidemic increase in non-communicable diseases (NDC) like obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and depression (Maus, 2011). Further urbanisation and with that a rise in urban population will bring an increased demand for resources to support human activity, and it will put pressure on land for several uses like e.g. transport infrastructure, housing, green space, etc. (Carmichael et al., 2019). However, efficiently designed cities can improve the residents’ health by addressing different aspects such as physical activity, strengthening social networks and capital (Maus, 2011). Physical activity has been proved to have beneficial effects on physical health regarding different aspects, including the prevention or treatment of different NDC’s (Taylor, Davies, Wells, Gilbertson, & Taylor, 2015; Eigenschenk et al., 2019; Cavill, Kahlmeier, & Racioppi, 2006). As urban areas continue to grow in population, there is an increasing necessity to create new ways of supporting physical activity in cities (WHO, 2017). Because of this, the relationship between the urban environment and physical activity has been receiving increasingly more attention from academic research. Research which mostly comes from two fields: urban planning/travel behaviour and public health/physical activity (National Research Council US, 2005). With the former often using quantitative methods and focussing on aspects such as active transport (De Nazelle et al., 2011; Saelens, Sallis, & Frank, 2003) and the latter including personal and social determinants and focussing on aspects such as the relationship between green spaces and physical activity (Ord, 2013; Richardson, Pearce, Mitchell, & Kingham, 2013). However, in order to tackle the residents’ health issues interdisciplinary collaborations are necessary, between urban planning and other actors, such as public health, physical activity experts, etc. (Maus, 2011). Thus, it is necessary to

understand who is involved in these collaborations and what factors affect collaborations, positively and negatively.

The following work aims at analysing the collaborative1 efforts between the actors

involved in the strategies and approaches to increase the physical activity of citizens through aspects of the built environment2. However, the scope of this work will only

include strategies which target public open spaces (parks, outdoor gyms, beaches, etc.) and spontaneous, unorganised physical activity. Therefore, strategies which include sport facilities (e.g. sport halls, stadiums etc.) or organised sport are exlcuded. The differences will be explained thoroughly in the following chapters. The study follows an exploratory research approach, which means it explores a phenomenon which is characterised by a lack of preliminary research (Mills, Durepos & Wiebe, 2009). The two different cities which are to be compared are the city of Malmö in the South of Sweden and Copenhagen, the capital of Denmark located just on the other side of the Öresund bridge.

1 Collaboration is defined as occurring when a group of autonomous stakeholders of a problem domain engage in an

interactive process, using shared rules, norms and structures, to act or decide on issues related to that domain (Wood & Gray, 1991, p. 146)

2 The built environment refers to the physical environment which is built by people, such as buildings, transport

2 Previous Research

This chapter will focus on previous research connected to this study’s intent. However, before looking into what is known about the topic, it is important to clear up some central terms and concepts surrounding the milieu of urban planning. Subsequently, the section 2.2 gives a brief insight into the historical relationship between urban planning and health as well as an overview of today’s health risks of living in cities. Section 2.3 introduces the relationship between physical activity and urban planning. After that, a closer look at physical activity and the built environment (PABE) research is taken, thus what is being researched, how and what the issues with PABE research are. Lastly, some research about collaborations between urban planners and other actors is presented.

2.1 Urban Planning Terms and Definitions

The terms urban planning and city planning are used interchangeably in this paper, they refer to the political and technical process of planning and developing of the uses of space in the urban environment (Encyclopaedia Britannica, n.d.). Land-use refers to the distribution, the location and the density of different spaces within urban areas (e.g. residential areas, commercial areas, recreational areas, industrial areas, etc.) (Handy, Boarnet, Ewing & Killingsworth, 2002). Furthermore, urban planning is concerned with the development of open land as well as the revitalisation of existing parts of the city. Planning on how to use space or how to change existing infrastructure in an urban area requires to include different perspectives, such as engineering, architectural, social and political perspectives. The product of urban planners is the built environment, another central term of this study. The built environment refers to the physical environment which is built by people, such as buildings, transport infrastructure, or open space, what remains is the natural environment (Northridge, Sclar & Biswas, 2003). Transport infrastructure, or transport system refers to the physical infrastructure which is used for transport within urban areas, such as roads, sidewalks, bicycle paths, etc. (Handy, Boarnet, Ewing & Killingsworth, 2002). Public open space can be seen as a problematic term, as there are broad as well as narrow definitions of it. Koohsari et al. (2015) argue that active living researchers often use a narrow definition of public open space, mostly referring to parks and green spaces in urban areas, whereas urban planners use a broad definition of public open space, where other recreational spaces which are open to everyone are included

(such as beaches, squares and shared public areas). When used in this work, the term open public spaces, will refer to the broad definition of the term.

2.2 Urban Planning and Health

This section starts by showing the historical connections between urban planning and health and after that, an insight into which health risks the modern city bears and what influence the city has on its residents’ health is given. The section concludes by showing the severity of health risks of cities and by introducing physical activity as countermeasure to non-communicable diseases, in prevention as well as treatment.

2.2.1 Urban Planning and Health – An Ambivalent Relationship

The following overview is a general European overview, it is to note that the development of city planning differs depending on which countries in Europe one is focussing on. Historically seen, urban planning and health have always had an ambivalent relationship, often urban planning initiatives resulted out of health emergencies (Frank & Engelke, 2001). For instance, with the age of industrialism, overnight changes happened in European cities, especially regarding the health of citizens. Poor water supply, sanitation problems, light and air pollution required a sudden shift of how cities were being designed (Barton, Grant, Mitcham & Tsourou, 2009). Cities made great efforts to integrate the residents’ health into the city planning. From the second part of the 19th century and in

the beginning of the 20th century public health was integrated into the planning of cities

to a high degree, in areas such as the provision of green spaces to promote physical activity and better mental health, the instalment of drinking water supply systems and sewage systems in communities to prevent infectious diseases as well as zoning ordinances to avoid dangerous industrial exposures (Kochtitzky et al., 2006). However, over the run of the second half of the 20th century the connection between urban planning

and public health became weaker. The two disciplines of urban planning and public health became more focused on their respective field; urban planning focused on transport and architectural design, whereas public health focused on cure and prevention of diseases (vaccination programmes and epidemic research) (Maus, 2011). This disconnection of the disciplines caused that planning policies often facilitated car-dependent, sedentary and privatised ways of living, all of which affected the health of citizens (Barton, Grant, Mitcham & Tsourou, 2009).

2.2.2 Health Risks of Cities

As mentioned in the introduction to this work, cities all over the world are growing, as is the number of people living in cities. This makes cities the engines of innovation and wealth, as well as the centres of nations’ economies, nevertheless, they also are the main culprits when it comes to disease, pollution and crime (Bettencourt et al., 2007). According to Khreis et al., (2017) cities are hotspots for health detrimental lifestyles and environmental exposures, such as sedentary lifestyles, physical inactivity, exposure to air pollution, noise, heat and waste. All of which influence the health of the residents to a high degree. For instance, Mueller et al.’s (2017) health impact analysis for Barcelona showed that the abovementioned exposures and lifestyles are strongly associated with all-cause mortality.

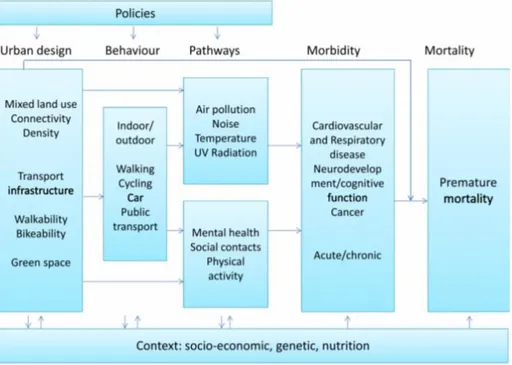

In order to see how urban planning influences the health behaviour of citizens it is important to understand the connections between land use, citizen behaviour, exposure, morbidity and mortality as seen in figure 1 (Nieuwenhuijsen, 2016).

Figure 1: Conceptual framework for the relation between urban and transport planning, environmental exposures and health. (Nieuwenhuijsen, 2016, p. 163)

According to Nieuwenhuijsen (2016), the levels of environmental exposures (such as air pollution, noise, temperature, UV radiation) can vary significantly, depending on urban and transport planning indicators. These urban and transport planning indicators are often called five Ds among urban planners, and they are crucial to understand the influence the

built environment can have on health (Ewing & Cervero 2010). The five Ds refer to density, diversity, design, destination accessibility and distance to transit. City density is usually measured by how many people live in a square km on average in a city. This is important because if the city grows in density rather than in size it means that the distances do not have to grow between destinations, and with shorter distances the chance of walking or cycling is higher than when the distance is longer and people may use cars or other motorised transport which increases air pollution, noise and creates traffic congestions. In the 90’s the European Community and the Agenda 21 (UN action plan, product from Earth Summit 1992 in Rio de Janeiro) have encouraged cities to adopt development strategies of growing in density rather than in size. Diversity refers to a diversity of land use mix, meaning that a city should not be divided into residential areas, shopping areas, recreational areas and working areas, but rather a diversity of the abovementioned areas should be present in every neighbourhood, which makes the distances shorter between home and shops, work, etc. Also, a good distribution of green spaces throughout the city can lower the heat. Design describes how the infrastructure is designed in general, which can make it more attractive for people to walk (e.g. pedestrian roads) or to cycle (e.g. cycling roads). Destination accessibility means how accessible a destination is to different groups of people, barriers which hinder accessibility can be physical but also psychological. Lastly, distance to transit refers to the shortest possible distance to a public transport source. If all characteristics of the five Ds are given one speaks of a compact city, if the characteristics are not given one is probably speaking of a city which suffers from urban sprawl and with a high tendency of motorised transport and sedentary behaviour among the citizen. All of this resulting in high exposure to health risks as seen in figure 1 (Nieuwenhuijsen & Khreis, 2018).

Another central factor in the calculation is personal behaviour of people (e.g. if a person is sedentary or mobile), which can further vary the personal exposure. Thus, the relationship between environmental exposures and personal behaviour will define how exposed people are to health risks which can lead to a higher mortality rate (Nieuwenhuijsen, 2016). Today’s most pressing health challenges are without a doubt non-communicable diseases (NCDs), which include heart disease, stroke, cancer, diabetes and chronic lung diseases. The conditions of NCD’s are causing the highest global share of death and disability, reaching up to 70% of all deaths all around the world (WHO, 2017), which makes it one of the most pressing and complex health problem with

which the modern world has to deal with, and probably will have to deal with increasingly in future (Daar et al., 2007). The magnitude of NDC’s make it a public health problem, where strategies of prevention and treatment need to be found. Prognoses estimate that the number of NCD’s will increase to a great extent in low- and middle-income countries in the coming years (WHO, 2017). Studies have shown that there is a strong evidence that physical inactivity increases the risk of various major NDC’s, such as coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, breast and colon cancers, etc. (Lee et al., 2012; Hu, 2003). In fact, physical inactivity was identified as the 4th leading risk factor of NCDs (preceded by

tobacco use, high blood glucose levels and hypertension) (Bull & Bauman, 2011). Furthermore, there is evidence that regular physical activity can help preventing as well as serve as a treatment to several NCD’s (Reiner, Niermann, Jekauc, & Woll, 2013). That is why WHO emphasises the need for people to meet their guidelines for physical activity and why they have included the aspect of physical activity in many of their policies and programmes, such as the ‘Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013-2020’ (WHO, 2013), or the ‘Global action plan on physical activity 2018-2030’ (WHO, 2019).

2.3 Urban Planning and Physical Activity

The following section aims at clarifying the connection between physical activity and urban planning. It will also serve as an introduction to the next section which will examine the current research connected with physical activity and the built environment (PABE). Social ecological models will support the claim of how physical activity behaviour can be systematically influenced by the built environment. However, before that, physical activity is defined.

Generally, from a health perspective, physical activity is defined as any bodily movement which is produced by skeletal muscles (Caspersen, Powell & Christenson, 1985). However, this broad definition can take various appearances. Thus, physical activity can be divided into different categories as the purpose of it can vary: it could be for sport and recreation (e.g. jogging, team sports, etc.), for transport (e.g. bicycling to work), for work (e.g. carrying things, lifting things), or for daily chores (e.g. household activities), also the intensity can vary from light to moderate to intensive. A further distinction, central to this work is the one between unorganised/self-organised physical activity/sport and organised physical activity/sport. Organised physical activity and sport refers to activities

which are structured and organised by clubs, where one must be a member in order to participate. The club provides facility, material and coaches for the participants and often the club takes part in locally/regionally/nationally organised competitions. Unorganised/self-organised physical activity and sport includes all sports and physical activities which can be done without membership of a sports club, such as going jogging, organising a football match with friends, etc. The scope of this work is limited to unorganised/self-organised recreational physical activity, excluding therefore organised physical activity and sport.

The previous section showed the health risks of the modern city and it showed how regular physical activity can help as a means of prevention and treatment to many NCDs. This section will show how physical activity can be connected to the modern city, and how it is used to challenge current public health problems. Public health professionals have recognised that promoting health only through programmes or changing the behaviour of individuals or small groups will not tackle the NCD crisis enough (Barton, Grant, Mitcham & Tsourou, 2009). What is needed is a more fundamental and systematic and environmental approach (Lawlor et al., 2003). The planning of cities, thus the built environment of cities, unequivocally influences the behaviour of the citizens in a systematic way. According to Barton et al., (2009), the built environment – physical form and management of places – affects the people living in and around it to a great extent, as it shapes the options of individuals, for example through the provision or lack of appropriate space and infrastructure. It can influence what kind of activities can take place or cannot take place. In connection to this, Gehl (2011) mentions three different types of outdoor activities; necessary activities (e.g. going to work, running errands, waiting for the bus, etc.), optional activities (e.g. taking a walk, go for a run, sit and sunbathe, etc.) and social activities (e.g. passive contacts, active contacts, communal activities, etc.). If the quality of the outdoor space is poor (e.g. unattractive design, with safety issues, etc.), only the necessary activities will occur. If the quality of the outdoor space is good (e.g. pedestrian friendly, with opportunities to sit and relax, etc.), necessary activities will happen in the same frequency, but they will take longer on average, and additionally optional and social activities will occur. This same explanation is of course valid for outdoor physical activity in urban areas; if the quality of outdoor space is good more people will be motivated for optional and social activities, which can include physical activity.

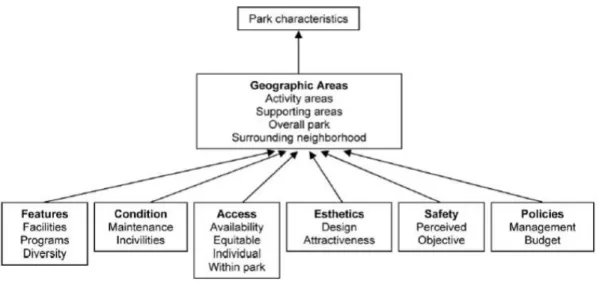

Edwards and Tsourous (2006) developed a model which depicts the environmental factors which influence an individual’s physical activity behaviour. As seen in figure 2, physical activity/active living is in the centre of the model with different layers of environmental factors influencing it. The first layer includes individual determinants such as gender, age and motivation, the second layer consists of social environmental influences such as culture, income and equity. The third layer consisting of built environmental influences, which is central to the proposed work’s perspective. The built environment can influence the physical activity behaviour through availability, attractiveness, convenience and safety of outdoor public spaces where physical activity and play is possible, such as green areas, sport pitches, running and walking paths, etc. However, there are also critical voices on the suitability of social ecological models to adequately differentiate how physical activity is influenced by the built environment (Maus, 2011). What is being criticised, more in detail, is that social ecological models are not detailed enough to assess how separate aspects of the built environment (e.g. accessibility, safety, etc.) might influence physical activity behaviour.

Figure 2: Factors influencing physical activity in communities (Edwards & Tsourous, 2006, p. 4)

This leads to an emerging field of research, which is called physical activity and the built environment (PABE) research, also connected to active living research. The next section will examine PABE research and go into more detail regarding what attributes of the built environment influence physical activity.

2.4 Physical Activity and the Built Environment (PABE)

Research

The following section will present the current state of knowledge regarding PABE research. After a short section explaining what PABE research consists of, the objects of study and the different methodologies are presented. Concluding this section, the issues and challenges of the research field are discussed as well as implications for future research.

2.4.1 What is PABE Research?

The first articles connected to PABE are dating back to the late 90’s and early 00’s, however since then the research field has been growing increasingly. Shortly said, PABE research is interested in exploring and understanding the associations between built environment and physical activity or active lifestyles (Harris et al., 2013). The aim is to demonstrate if and how certain aspects of the built environment can influence the physical activity behaviour of citizens, and to understand the relationship between the two. This field of research emerging and it is receiving increasingly more attention. In order to understand the current state of the research it is important to see the development the field has had in the last years. Harris et al.’s study from 2013 tried to map out the development of research connected to physical activity and the built environment (PABE). Through snowball sampling using citation network links they identified 318 articles related to PABE, most of them (191) were discovery-focused, meaning that they examined the relationship physical activity and the built environment, the rest of the articles were divided into reviews of previous literature (79), articles focused on theory and methods for PABE (38) and intervention studies with PABE (7), and the last four with disconnected topics. Harris et al (2013) concluded that PABE research was still in its discovery phase, however transitioning into the next phase, it was also noted how few intervention studies there were and that they were rather disconnected from the other PABE research articles. It is to note that from the time Harris et al.’s study was published to today almost seven years have passed. The fact that PABE research has been growing also after Harris et al.’s publication is underlined by Gilles-Corti et al. (2019), when they state that from the years 2001-2010, 570 articles were found using the keywords ‘environment’ and ‘physical activity’, whereas, from the years 2011-2018, 1286 were

found. This growth in articles shows that there is a need to understand how the built environment influences the physical activity behaviour of citizens.

2.4.2 PABE Research – What? How? and by Whom?

This section will try to answer the questions of what the objects of study are, how they are studied and who studies them, by referring to important PABE studies and researchers. As mentioned in the previous section, PABE research is a rather new field of study, therefore, there is no standardised way of measuring the associations between physical activity and the built environment. Adding to that, PABE research can be seen as an intersection of different disciplines, where conceptions, methodologies and interests are mixed. This is reflected on the vast variety of different studies, as the following section will show.

Who studies PABE?

Traditionally, there were three main disciplines which were interested in measuring physical activity environments: public health (including exercise and behavioural science), planning (including urban and transport planning and design) and leisure studies (Sallis, 2009). Even though all three were interested in measuring physical activity environments, they did so in different ways. The health sciences used to focus on settings like recreation facilities, schools and open spaces, where people engaged in active recreation, they tended to include the social environment into their measurements, which consisted mostly of direct observations (such as SOPLAY, System for Observing Play and Leisure Activity in Youth) and self-reports (Sallis, 2009). The planning disciplines on the other hand, were interested in the travel behaviour of the citizens in order to design communities with higher life standards, thus with less traffic congestion and better air quality (Höhner et al., 2003: Sallis, 2009). Their methods of measurement included GIS methods (geographic information system), GIS is a framework where geographical data is gathered, organised and analysed, with the use of GIS one can get deeper insight into patterns and relationships of geographical data. Lastly, the leisure studies contributed to physical environment measurements through ratings of aesthetics of recreation facilities. Their interest lied in examining the accessibility of recreation facilities regarding different attributes, such as biophysical (proximity, quantity and quality of vegetation) and social (crowding, conflict between users) attributes (Sallis, 2009). However, in the last couple years these three traditional approaches increasingly started to collaborate and influence

each other, resulting in further reaching and more complex study designs, as the three traditions complement each other.

Today, many PABE studies are conducted in collaborations between different academic disciplines, such as urban planning, public health, sport science, landscape architecture, etc, however, it is to be noted that most studies are still imprinted with the urban planning/travel behaviour approach or with the health/leisure/physical activity approach (National Research Council US, 2005).

What is being studied and how?

The objects of PABE studies are on one side aspects of the built environment, which can be whole communities and neighbourhoods, but also transport routes (e.g. cycle paths, roads), parks, green areas and other recreational spaces, and on the other side aspects of the physical activity of the citizen, which can also take various appearances (WHO, 2017; Gilles-Corti et al., 2019). When it comes PABE research, the main focus is mostly set on walking and bicycling (for transport as well as recreational purposes), jogging and other recreational activities receive less attention (Gilles-Corti et al., 2019). As mentioned above, many studies can still be attributed to one of the research traditions, be it urban planning/travel behaviour or health/leisure/physical activity, even though they collaborate more than in the past. That is why studies from the different traditions are treated in separate paragraphs.

Urban Planning/Travel Behaviour

Studies which follow the urban planning tradition usually focus more on the relationship between urban design and active transport, thus they give attention to how certain attributes of the built environment will make more people walk or bicycle to their destination. Handy, Boarnet, Ewing and Killingsworth (2002), for instance, speak of five attributes of the built environment which are crucial for understanding the relationship with physical activity: density and intensity, land use mix, street connectivity, street scale and aesthetic qualities. Similarities to Ewing and Cervero’s (2010) five Ds of urban planning are apparent. These five attributes of the built environment will be looked at closer in the following paragraphs.

Density and intensity refers to how much activity there is in a certain area, the density

and activity of an area (e.g. of one square km) can be measured by counting how many people live there, how many jobs exist and how much commercial space there is (Handy,

Boarnet, Ewing & Killingsworth, 2002). If the density is higher it means that the distances between the destinations does not increase, which makes it more likely for people to use alternative transport modes to motorised transport, such as walking or cycling, thus increasing the physical activity. Gilles-Corti et al. (2019) note that density alone is unlikely to increase the physical activity of citizens, density must come with an increased accessibility of activities (shops, public transport, recreation, etc.), an increased land use mix. Sallis et al.’s study (2016) confirm the importance of net residential density, as it results as one of the environmental attributes which was significantly related to physical activity in their study.

Land use mix, as mentioned earlier, defines the distribution and location of different

types of spaces, the share of total land area for different uses decides how diverse the land use is (Handy, Boarnet, Ewing & Killingsworth, 2002). The diversity of destinations and provision of open public spaces is seen as central for increasing walking for transport and walking for recreation (Hooper, Knuiman, Foster & Giles-Corti, 2015).

Street connectivity and street scale are described as separate attributes by Handy,

Boarnet, Ewing and Killingsworth (2002), but are taken in the same paragraph for their close relation here. They refer to how well connected the streets are, if there are alternative routes (shortest distance to destination) and how the streets are designed (large, busy roads having a negative impact on walking behaviour). Ways to measure these two attributes can by measuring the intersection density, which was another positively significant attribute of physical activity in Sallis et al.’s study (2016).

Aesthetic qualities refer to the attractiveness of a place, this attribute, as opposed to the

previous ones cannot be measured by counting intersections or people living in a square kilometre. It can be approached in many different ways, and lately PABE research has given more attention towards the characteristics which open public spaces should have to attract people. However, the aesthetic qualities described by Handy, Boarnet, Ewing and Killingsworth (2002) refer to the aesthetic qualities which a destination must have to encourage people to walk or bike there, whereas newer research shifted its attention towards what characteristics an open public space (mostly parks and green areas) must have to attract people but also to have people be physically active in the recreational space (e.g. play, exercising, sports, etc.). Some of these studies will be presented later.

At this point it is to note that the vast majority of PABE studies are conducted in high-income countries. Only few studies have been conducted in low-middle high-income countries (Gomez et al., 2010; Parra et al., 2010; 2011). Nevertheless, the few studies from low-middle income countries showed similar results, which is also confirmed by Sallis et al.’s study (2016), which looked at how objectively measured attributes of the urban environment are related to objectively measured physical activity in a sample of adults from 14 different cities on five different continents (including low- and middle income countries). The results showed that four out of six environmental attributes were significantly related to physical activity, the four attributes being: net residential density, intersection density, public transport density and number of parks. Their conclusion is that the design of urban environments has the potential to influence the physical activity behaviour of citizens on a large scale, therefore, they suggest to focus more research on the field and to spread the knowledge.

Health/Leisure/Physical Activity

The following paragraphs present PABE studies which are associated with health, leisure and physical activity disciplines. Most of the studies connected to the health/leisure/physical activity disciplines focus more on recreational centres, such as parks and urban green spaces (UGS), furthermore, the studies include socioeconomic aspects (age, gender, income level, etc.) and individual attitudes and intentions (preferences, opinions, etc.) (National Research Council US, 2006; Bedimo-Rung, Mowen & Cohen, 2005).

For instance, one thread of research is focussed on what characteristics a park or a green area must have to encourage people being physically active. Because certain populations are less likely to use parks and UGS, it is important to understand which park characteristics attract which groups of people and furthermore which park characteristics encourage people to be physically active. Bedimo-Rung, Mowen and Cohen (2005) developed a conceptual model for park characteristics and physical activity (figure 3). Factors which influence physical activity in parks can be divided into two categories: individual characteristics of park users and park environment characteristics. Individual characteristics of park users on the one hand include aspects such as demographic (age, gender, socioeconomic status, etc.) and social characteristics (habits, interests, etc.). One demographic where a clear difference is observable seems to be gender, as Evenson et al.’s study (2016), a review of studies using SOPARC (System for Observing Play and

Recreation in Communities) in connection to parks and physical activity, concluded that typically more males than females visit parks, older adults were the least represented group. Regarding the physical activity levels varied to high degree depending on the study, however, young people were generally more physically active than adults and young children more than adolescents. Similar observations were made Lindberg and Schipperijn (2015), as in their study males were more vigorously active when using the park facilities than females.

Park environment characteristics, on the other hand include six conceptual areas as seen in figure 3: features, which refer to what facilities can be found in a park, for instance, running tracks, sports fields, outdoor gyms but also picnic areas, green areas or areas with water. A park with diverse features will attract diverse groups of people with different interests. Schipperijn et al.’s study (2013), for instance, found positive associations between physical activity in UGS with size, walking/cycling routes, wooded areas, water features, lights, pleasant views, bike rack, and parking lot. Another study showed that facilities which offer opportunities for games and playing were more used for physical activity than facilities for individual training of strength and fitness (Lindberg & Schipperijn, 2015). The ‘feature’ area also includes programmes and events offered by/in the park, such as training groups. The second area, condition, refers to the condition of the park, thus if the facilities are in a good shape or if they are worn of, also if the park is clean and well maintained. Access, the third area, includes various forms of access, first and foremost, people should have access to a park regardless of where in a city they live, parks should therefore be distributed equally across different neighbourhoods and close to one’s home. However, access also refers to perceived access to different facilities within the park, for instance, could one group of people claim ‘ownership’ over a place and hereby exclude other groups. The fourth area, aesthetics, refers to how a park is designed, including layout, landscaping, balance between sun and shade, etc. Park aesthetics can also influence perceived access, for instance an outdoor gym placed next to a ‘social area’ (e.g. area with people sitting relaxing) will probably attract more people who are comfortable being seen in a gym, and it will discourage people who would not feel comfortable. Aesthetics was identified as one of the key factors when designing parks by Lindberg and Schipperijn (2015). Safety is another important factor, it refers to how safe people feel being in a park. A distinction is to be made here between objective safety, that is how much criminal activity there actually is, and perceived safety, that is how safe

people feel. Lastly, policies, refers to the management and the budget of parks which can vary widely depending on the neighbourhood.

Figure 3: Conceptual model for park characteristics and physical activity (Bedimo-Rung, A. L., Mowen, A. J., & Cohen, D. A., 2005, p. 163)

Bedimo-Rung, Mowen and Cohen (2005) suggest the six above mentioned areas to be studied in order to better understand the how parks can encourage physical activity. Lastly, an underrepresented thread of PABE research is shortly going to be presented here; PABE intervention studies. As mentioned in the introductory part of this section, intervention studies are rather rare within the PABE field (Harris et al., 2013), as an actual alteration of the physical environment is necessary to conduct an intervention study. However, the results of the few intervention studies show some promising signs for the effectiveness of interventions, especially if the interventions involve the use of physical activity programmes combined with change of the built environment (Hunter et al., 2015; Andersen et al., 2017). Nonetheless, the need for more robust studies is emphasised by researchers.

2.4.3 Issues of PABE Research and Implications for Further Research

This section will present some issues of PABE research and discuss the implications for future research. It is not to be seen as an exhaustive listing, but rather it covers the key critique points of the emerging research field.

One of the key critique points throughout the different PABE research traditions was the inconsistency of measurement. If one, for instance, looks at the systematic review of PABE studies by Ferdinand et al. (2012), which showed that out of 169 articles (found

with keyword search and then abstract screening) 89,2% reported a beneficial relationship between built environments (e.g. trails, parks, sidewalks) and physical activity, but on a closer and more critical look, the authors remark that most studies used simple observational study design which are not suited to determine causality. Other studies using more objective physical activity measurement (e.g. pedometer) reported 18% less beneficial relationships.

Similarly, Giles-Corti et al. (2019) examined systematic reviews and studies concerned with how ‘walking for transport’ and ‘walking for recreation’ are influenced by the built environment. What Giles-Corti et al. criticised was that many studies showed inconsistencies on how the exposure was measured, but also that research is often poorly linked to policy and practice. Especially the lack of specificity of many studies caused that the actual results cannot be used by planners.

Another key issue was the issue of stratification, which is discussed by different researchers (National Research Council US, 2005; Gilles-Corti et al., 2019; Koohsari et al., 2015). It refers to how the relationship between physical activity and the built environment can vary depending on subpopulation, urban setting, etc. Therefore, studies should differentiate between population groups (age, gender, socio-economic status, etc.) and in order to be more instructive the different groups should be examined and reported separately (Gilles-Corti et al., 2019). Which would make it easier to design new studies which are focused on specific target groups and specific attributes of the built environment (Koohsari et al., 2015). More longitudinal and intervention studies are necessary in order to define causal relationships between physical activity and specific attributes of the built environment (Koohsari et al., 2015).

The future of PABE research should seek interdisciplinary multi-sector research collaborations including experts from various fields, such as public health, physical activity, urban planning, landscape architecture, etc. in order to develop more complete conceptual models which help to suggest and analyse variables and relationships between types of physical activity and attributes of the built environment for different groups of populations (Gilles-Corti et al., 2019; National Research Council US, 2005).

2.5 Urban Planning Collaborations

The previous sections of this literature review aimed at gradually drawing the attention towards the scope of this research by first presenting the relationship between urban

planning and health (2.2), after that showing the importance of physical activity for health and its connection to the urban environment (2.3), in order to then present the current state of research connected to PABE (2.4). Through these sections it has been shown that physical activity is a crucial health resource and that the built environment can represent an effective instrument to influence the physical activity of citizens in a systematic way. The review of previous PABE research has shown that the research field has grown and made advancements, however, there are still important issues which need to be considered. Different of the cited authors and sources emphasised the importance of collaborations when it comes to health interventions connected to the built environment, be it for interagency collaborations between urban planning and public health (Maus, 2011; Barton, Grant, Mitcham & Tsourou, 2009), or interdisciplinary collaborations connected to research (Gilles-Corti 2019; National Research Council US, 2005).

The following section examines previous research concerned with collaborations between urban planning and other actors and institutions such as public health, researchers and communities regarding the built environment and health. The section aims at showing that there is a gap of knowledge connected to how urban planners collaborate with other actors in order to increase physical activity through the built environment. A research gap which this research will try to address.

When it comes to previous research about collaborations which target health interventions in the built environment, relevant studies were found which can be divided into three categories: firstly, studies which aim at reconnecting public health and urban planning or integrating the approaches from the two disciplines (Hoehner et al., 2003; Maus, 2011; Carmichael et al., 2012; Koohsari, Badland & Giles-Corti, 2013).Secondly, studies which look at collaborations between urban planning practitioners and researchers (Fazli, 2017; Crist, Schipperijn & Kerr, 2016; Crist et al., 2018). And lastly, collaborations between urban planning and communities. For this category only one article (Pawlowski et al., 2017) could be found (which is also related to health interventions through the built environment), however, it is still regarded as relevant.

Urban planning and public health

What the studies here have in common is that they all attempt to reconnect public health with urban planning, because they see that a stronger collaboration between the two fields would be beneficial.

For instance, Hoehner et al.’s (2003) study focused on the different methodological approaches for examining the association between the environment and behaviour which are used by professionals from the fields of urban planning and public health. According to Hoehner et al. both disciplines had the same question they tried to answer, which was ‘how do we get more people to bike and walk?’, however, the motives were different. For urban planning researchers, more people walking and bicycling would lower congestion and lighten the environmental impact of motorised transport, whereas the main aim for public health researchers was to tackle the increasing inactivity, obesity and chronic disease. Hoehner et al.’s concluded that collaborations between urban planning and public health (in research and dissemination) can increase the number of communities which will encourage active living.

Maus (2011) and Carmichael et al. (2012) pursued similar goals in their studies. Both looked at barriers and facilitators of collaborations between urban planning and public health. On the one hand Maus (2011) explored the process of collaboration between urban planning and public health in different municipalities in California, USA. As a result, he developed theoretical models for collaboration to identify barriers and incentives and a cost-benefit analysis tool which can be used in practice to determine if fruitful and sustainable collaborations are possible.

Carmichael et al., (2012), on the other hand, focussed on examining the barriers and facilitators of integrating the dimension of health into spatial planning. Their results (which are mostly based on UK literature) showed four categories of facilitators and barriers. The first category sees different conceptions and understandings of health by the different stakeholders involved in the process as possible barrier or facilitator, thus narrow health definitions used by planners would be seen as barriers and close collaboration between health and planning professionals as facilitators of integrating health into spatial planning. Secondly, the types of governance and the political context had a meaningful influence on the inclusion of a health perspective. Cultural and structural differences between sectors and departments are seen as barriers, whereas close partnerships between sectors as facilitators. The third category is concerned with how the institutions work, barriers in this case would be scarce funding, and different sectoral priorities, whereas facilitators would be high level of guidance and support from above. Lastly, the fourth category is connected to appraisal (evaluation) processes, where barriers are late timing of appraisals and inadequate appraisal processes, facilitators are monitoring plans through

appraisal and developing a robust Health Impact Assessment3 (HIA) methodology. The

concluding proposition made by Carmichael et al. (2019) was to include a robust HIA into the planning process, such as is done with Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and Strategic Environment Assessment (SEA).

Urban planning practitioners and researchers

As seen in section 4.3.2, where the issues and implications of PABE are discussed, one important issue of PABE research was that often research was poorly linked to practice and therefore not usable (Gilles-Corti et al., 2019). Different researchers have understood that often collaborations between urban planning practitioners and researchers are not proceeding as it they optimally could (Crist, Schipperijn & Kerr, 2016; Crist et al., 2018). Crist et al.’s (2018) study, for instance, interviewed transport planning practitioners and academics with expert knowledge in health or planning about how they perceived collaborations with each other. Their results show that factors which were perceived as barriers to collaborations were e.g.: difficulty of changing existing practices, setting up contracts with universities or research organisations, different needs or priorities in research foci. Whereas facilitators of collaborations were e.g.: understanding each other’s needs, having mutual goals, having research tied to existing regulations.

Another perspective on the issue is given by Fazli et al. (2017). In their study, they conducted a qualitative thematic analysis of data collected through consultations with a broad group of stakeholders involved in decision making and policy development related to the built environment in and around Toronto, Canada. The top priorities for them regarding research were e.g.: improved coordination and standardisation of methods for measuring associations between the built environment and physical activity, increased examination of effects for different populations (what works for whom under what circumstances), more evaluations of interventions on the built environment as well as health economic evaluations for estimating the costs, benefits and impacts.

Urban planning and communities

Communities represent another actor in collaborations when it comes to creating changes that have effect on active living. The findings were rather scarce, however, one interesting article was found which presents a study protocol for a study which aims at conducting a

3Health Impact Assessment (HIA) is a means of assessing the health impacts of policies, plans and projects in

community-based intervention in a deprived neighbourhood in Copenhagen, where children and seniors co-design urban installations in an interdisciplinary collaboration with researchers (Pawlowski et al., 2017). Unfortunately, the results of the study are not yet available. Nevertheless, this study represents a novel approach to active living interventions in the built environment, as the community is involved in the designing of the intervention and researchers from different disciplines (health researchers, designers, architects, landscape architects and anthropologists). One can expect valuable insights from this new interdisciplinary approach to increase physical activity through the built environment.

This last section of the second chapter showed that collaborations between urban planners and different actors are beneficial when it comes to health interventions connected to the built environment. It also showed that not much research has been conducted regarding collaboration to increase physical activity through the built environment. This work aims at addressing that knowledge gap and give an insight into the issue. In order to create more fruitful and sustainable collaboration it is therefore necessary to the get a deeper understanding of the collaborations which take place when health interventions, or approaches to increase the physical activity through the built environment are carried out.

3 Aim and Research Questions

3.1 Problem Statement

The research field of PABE is rather new and upcoming, with an increasing number of publications (Giles-Cort et al., 2019), this shows that the need for a deeper understanding of how the built environment can influence the physical activity is existing. This is reflected by a recent publication by the WHO (2017), were several examples of cities are portrayed which are attempting to change the built environment in order to increase the physical activity of their citizens. Even though there are examples of cities which have active living initiatives, little is known about how cities approach the issues of the built environment and physical activity in a systematic way. That is to ask, who is involved and in what way. As seen in the ‘previous research’ chapter, collaboration is a key element necessary in order to address the complex health problems connected to built environment (WHO, 2017; Maus, 2011). Interagency collaboration between city planning and external actors such as universities and public health, interdepartmental collaboration, between the different departments and offices, and collaboration with communities and citizens. If the assumption is to be sustained that different kind of collaborations can support the attempt of increasing physical activity in cities, then it is necessary to get a deeper understanding of the factors that represent the facilitators and barriers of such collaborations.

3.2 Research Aim

The aim of this study is to analyse the collaborative efforts between the actors involved in the strategies and approaches to increase the physical activity of citizens through aspects of the built environment. The focus of this research lies on strategies and approaches which target unorganised/self-organised physical activity in public open spaces in Malmö, Sweden, and Copenhagen, Denmark. To analyse the collaborative efforts, the strategies of the respective cities’ departments were investigated. The empirical data for this study consists of interviews with urban planners and other professionals from the municipal offices as well as official city documents from the two cities. Concepts and constructs from collaboration theory were used in the analysis to identify possible barriers and facilitators of the collaborations which were the objects of investigation.

3.3 Research Questions

1. What strategies are used by Malmö and Copenhagen to increase the physical activity of citizens in public open spaces?

2. What are the barriers and facilitators of collaboration between the actors involved in the strategies?

3. Are there findings which can help to propose more fruitful/sustainable collaborations and strategies?

4 Theoretical Framework

The following chapter will develop a theoretical framework which supports the research aim and offers tools for analysis to help answering the research questions. In order to understand how collaboration works, what makes collaboration thrive but also what hinders collaboration, it is necessary to have a look at how collaboration is defined and how it is conceptualised. A closer look at the theory of collaboration will help with that. First, the previously used definition of collaboration is clarified. After that, different conceptualisations of collaboration are mentioned. A combination from different conceptualisations from various researchers is then explained more in detail, as it will serve as theoretical framework for this study.

4.1 Theory of Collaboration

4.1.1 Definition

This work will use the definition of collaboration by Wood and Gray (1991), which was mentioned earlier in the text. In their article, which aims at developing a comprehensive theory of collaboration, they looked at different conceptualisations of collaboration used in previous research, and they noticed that the definitions were often vague and imprecise, also that important elements were missing. According to them the definition of collaboration should answers the questions: who is doing what, with what means, towards which ends? Thus, they developed a definition which can include different forms of collaborations which are observed:

Collaboration is defined as occurring when a group of autonomous stakeholders of a problem domain engage in an interactive process, using shared rules, norms and structures, to act or decide on issues related to that domain (Wood & Gray, 1991, p. 146)

The part ‘stakeholders of a problem domain refers to the organisations or actors who have an interest in the problem domain. It is to note that the definition does not specify if the different stakeholders have the same or if they different interests, because both can be the case, furthermore, the interest may change or be redefined as the collaboration proceeds. The fact that the definition states a ‘group’ of stakeholders means that not all stakeholders (with an interest in the problem domain) need to be involved, but it can also just be a part of them.

The word ‘autonomous’ refers to the fact that in a collaboration, the stakeholders who are involved still have their independent decision-making power, even though in a collaboration there are shared norms and values. The level of autonomy, however, can vary between different kinds of collaborations. Wood and Gray specify that when stakeholders do not have any autonomy, one does not speak of a collaboration anymore, but rather a different form, e.g. a merger.

‘Interactive process’ means that all the stakeholders who are involved are actively contributing to the relationship, and that the relationship has some duration and change can happen.

In a collaboration the involved stakeholders have to share ‘rules, norms and structures’ during the interactive process. The rules and norms could be implicit or explicit (e.g. with contracts). Structures could be temporarily and evolving, but they could also be permanent, as for e.g. international associations or federations.

Even though a collaboration is pursuing a goal, one can still speak of a collaboration even when the goal is not achieved. That is why the definition uses the words ‘act or decide’. As a process can be called a collaboration when stakeholders engage together in order to act or to decide.

Lastly, ‘issues related to that domain’ refers to the fact that the stakeholders need to orient their actions and decision towards the problem domain which brought them together. The problem domain could be extremely broad as well as very narrow.

This definition of collaboration can include many different forms of collaboration, Maus (2011) notes how cross-disciplinary collaborations can be distinguished into at least three dimensions of scope: organisational, geographic and analytic. The organisational scope defines if the collaboration happens only within one organisation (intra-organisational), or multiple (inter-organisational), one can distinguish furthermore if the collaboration involves actors from different sectors (intersectoral), for instance when universities work together with communities or pubic sector organisations, etc. The geographical scope of a cross-disciplinary collaboration can range from local to national or international context, whereas the analytic scope can range from molecular (e.g. neuroscience) to molar (e.g. public policy) levels.

In the specific case of the collaboration which is the object of interest in this work, the group of autonomous stakeholders are city planners from different departments (in

Malmö and in Copenhagen), researchers and communities. Which means that the scope includes both intra-organisational as well as intersectoral level. The problem domain is strategies, approaches and projects which aim at encouraging unorganised physical activity in/through open public spaces. The geographical scope therefore is only local. Part of the aim is to identify which factors work as facilitators or as barriers for the process of interaction between the stakeholders. Which makes the analytic scope of the collaboration molar.

4.1.2 Conceptualisation of Collaboration

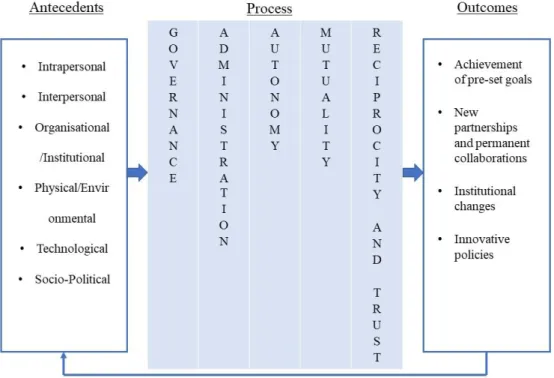

The broadness of the definition indicates that there is vast amount of different forms of collaboration, which makes it problematic to have one general theory of collaboration. Rather, different research fields have varying conceptualisations of collaboration. Wood and Gray (1991) were influential for collaboration researchers to come, researchers in the fields of public health (D’Amour et al., 2005), public management (Thomson & Perry, 2006; Thomson & Perry, 2009) and team science literature (Stokols et al., 2005; Stokols et al., 2008) are influenced by Wood and Gray’s work on collaboration theory. Although, the mentioned researchers have different approaches to how they conceptualise collaboration, they all have share the same basic framework, proposed by Wood and Gray (1991), which postulates that collaboration can be divided into three dimensions: preconditions – process – outcomes. On the one hand, some researchers use the exact same or similar terms for their frameworks, Thomson and Perry (2006; 2009) and Stokols et al., 2005; 2008) use antecedents instead of preconditions. D’Amour et al. (2005) on the other hand, notes that some researchers (especially from public health) choose a perspective based on a systems approach, where collaboration is made of inputs, processes and outputs. In that case inputs would be organisational, professional and structural factors which influence the process, and the outputs would be the efficiency of the team which is collaborating. As mentioned in the previous chapter, this study aims at identifying the barriers and facilitators of collaboration in context with the approach and strategies for increasing unorganised physical activity in public open spaces. In order to understand what could facilitate or hinder a collaboration it is necessary to have a look at how researchers conceptualised collaboration, thus the different dimensions: antecedents – process – outcomes.

Preconditions/Antecedents

Preconditions or antecedents of collaboration are factors which make it possible for a collaboration to even happen. Furthermore, they are factors which influence the process of collaboration, thus affecting the outcome of the collaboration as well. Depending on the research tradition or the researcher there can be differences on which antecedents are seen as key factors to enhance the readiness for collaboration among stakeholders (Gray & Wood, 1991; Stokols et al., 2005). Some of the most mentioned, and recurring factors are e.g. high levels of interdependency, high degree of organisation in problem domain, previous history of collaboration or a situation in which one stakeholder has resources to other needs and vice-versa(Wood & Gray, 1991; Thomson & Perry, 2006; Stokols et al., 2005). Stokols et al. (2005), researchers from team science, tried to categorise the antecedents into different domains in their model of transdisciplinary scientific collaboration, and the domains which they created were: intrapersonal (e.g. values and attitudes towards collaboration), social (e.g. mutual respect among team members), physical environmental (e.g. spatial proximity of offices), organisational (e.g. organisational incentives for collaboration) and institutional (e.g. institutional support for collaboration). These factors contribute to enhancing collaboration preparedness and can influence the process of collaboration. In their later work, Stokols et al. (2008), reviewed articles from various disciplines about team science and collaboration and adapted their first model of collaboration. Their examination of different fields of research connected to team science and collaboration revealed a typology of contextual influences on transdisciplinary research collaboration4. The typology of contextual influences includes

six categories. The following typology will serve as an analytical tool for the underlying work, thus they are presented in more detail below:

• Intrapersonal: Refers to attitudes and characteristics of each single stakeholder. For instance, the stakeholders’ attitudes and values towards collaboration, if they value and support a culture of sharing and embrace opening up to other perspectives from different professions or disciplines. Also, if the stakeholders want to invest time and energy into an endeavour which could bring tensions and

4 The term transdisciplinary is often used interchangeably with interdisciplinary or multi-disciplinary. This work

follows the distinction made by Rosenfield (1992, p. 1351):

Multi-disciplinary: Researchers work in parallel or sequentially from disciplinary specific base to address common problem

Interdisciplinary: Researchers work jointly but still from disciplinary-specific basis to address common problem Transdisciplinary: Researchers work jointly using shared conceptual framework drawing together disciplinary-specific theories, concepts, and approaches to address common problem

uncertainties. Earlier collaboration experiences fall into this category as well, as they can enhance collaboration preparedness. Lastly, the presence of leaders who are empowering and inclusive can be key drivers for a collaboration to happen. • Interpersonal: Refers to how the stakeholders relate to each other as well as the

composition of the collaboration. Such as the diversity of skills and expertise found among the involved stakeholders, as well as the stakeholder’s willingness to arrive to a shared vison with common goals through communication and mutual respect.

• Organisational/Institutional: Organisational incentives which encourage collaboration and institutional support through supportive structures (e.g. non-hierarchical) for collaboration. The presence of resources which make it possible for long term support of collaboration was seen as another key factor, as well as opportunities for informal contact and communication among stakeholders. • Physical/Environment: For instance, spatial proximity to stakeholders’ offices

and availability of close and comfortable meeting places for collaboration. • Technologic: Refers to the stakeholders’ technologic infrastructure readiness as

well as the involved actors’ knowledge and familiarity with various technological information and communication tools.

• Socio-political: Refers to socio-political influences such as policies which can support or encourage collaboration between stakeholders, or problems (e.g. environmental, public health, etc.) which prompt collaboration.

The factors appearing in these six categories can support or impede the development of collaboration. It is to note at this point that Stokols et al.’s (2008) typology is created to analyse transdisciplinary research collaboration, however, the typology was created by analysing research on collaboration from different disciplines (e.g. social psychological and management research, community based coalitions, transdisciplinary research centres). Therefore, it is considered suitable as an analytical tool in this work as well. As the next paragraph will show, many of the factors mentioned here in the antecedents dimension, have central importance in and influence on the process of collaboration.

Process

The process of collaboration is often seen as the ‘black box’, and the part which is least known of in research (Wood & Gray, 1991; Thomson & Perry, 2006). What is clear is that collaboration “occurs over time as organisations interact formally and informally