Sustainability

Sells

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: International Marketing AUTHOR: Sarah Fraß, Luana Walter

JÖNKÖPING, May 2021

Appeals driving Consumer Engagement of Green

Skincare Brands

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Sustainability Sells: Appeals driving Consumer Engagement of Green Skincare Brands

Authors: Sarah Fraß and Luana Walter Tutor: Tomas Müllern

Date: 2021-05-24

Key terms: Appeals, Consumer Engagement, Consumer Brand Engagement, Green Skincare, Sustainability, Instagram

Abstract

Background: Sustainability within the skincare industry is an important theme in marketing research. Sustainability sells, but it is necessary to understand how brands can drive consumer engagement on Instagram by using certain appeals. As social media has revolutionized the way consumers interact with brands, engaging online today represents a fundamental factor for a company’s success. Consequently, this study explored in particular CBE of green skincare brands with regards to female European millennials. As we were the first to research the context of three highly relevant fields in today’s time, which are sustainability, Instagram and skincare in the European setting, we contribute with new significant findings.

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to understand which appeals drive millennial’s CBE of green skincare brands on Instagram. Thus, particularly green company-created content was examined.

Method: The method chosen to answer our study purpose was semi-structured interviews. Therefore, 18 female European millennials have been interviewed to understand their thoughts and opinions concerning our purpose. Hence our study was based on an interpretivist philosophy while an inductive approach was followed. In addition, deductive elements loosely framed this qualitative study, given existing literature in respective fields of this research. Finally, we concluded this study with a conceptual framework, created upon our empirical findings.

Conclusion: The results show that in specific three different types of appeals could be identified to drive CBE of green skincare brands on Instagram. These are Affective, Identification, Spokesperson &

Trust as well as Factual. With regards to our CBE conceptualization,

these three themes all drive CBE to a different extent in terms of

cognitive processing, affection and activation. All in all, this study

could identify Affective to be the most relevant appeal in terms of driving CBE as well as affection being the only CBE dimension, which can be driven by all three themes. Green skincare brands can use these findings to understand which appeals drive engagement while also raising awareness around sustainability-related topics.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background and Problem Definition ... 1

1.2 Purpose and Research Question ... 3

1.3 Significance of the Study ... 4

1.4 Delimitations ... 4

2. Theoretical Background ... 4

2.1 Consumer Engagement ... 4

2.1.1 CE in the Marketing Literature ... 4

2.1.2 Definition of CE ... 8

2.1.3 Conceptualization of CE ... 9

2.2 Appeals of company-created Content on Instagram ... 9

2.3 The Rise of Social Media ... 10

2.3.1 Online CE on Social Media ... 10

2.3.2 Instagram ... 11

2.4 Definition of Sustainability ... 12

2.5 Green Skincare ... 13

2.5.1 Skincare Industry ... 13

2.5.2 Trends of Sustainability in The Skincare Industry ... 14

2.5.3 Possible Aspects of Green Skincare Brands ... 16

2.6 Millennials as the Ideal Target Group ... 19

2.7 Conceptual Framework of our Study ... 20

2.7.1 CBE Working Definition ... 20

2.7.2 Proposed Conceptual Framework ... 20

3. Method ... 21

3.1 Research Philosophy ... 21

3.2 Research Approach ... 22

3.3 Research Purpose ... 24

3.4 Research design ... 24

3.5 Justification of the Research Approach ... 26

3.6 Data Collection ... 27

3.7 Sampling ... 28

3.8 Interview Guideline Design ... 29

3.9 Execution of the Semi-Structured Interviews ... 30

3.10 Data Analysis ... 31

3.11 Validity and Reliability ... 32

3.12 Ethical Consideration ... 34

4.1 Affective ... 39

4.1.1 Positive and Negative Emotional Content Affects Consumer Engagement .... 39

4.1.2 Relational Content to Engage with Users ... 40

4.2 Identification, Spokesperson & Trust ... 42

4.2.1 Identification enhances the relation of a brand, its ambassadors and followers ... 42

4.2.2 Spokespersons as a Useful Engagement Driver ... 43

4.2.3 Trust and Credibility Drive Consumer Brand Engagement ... 44

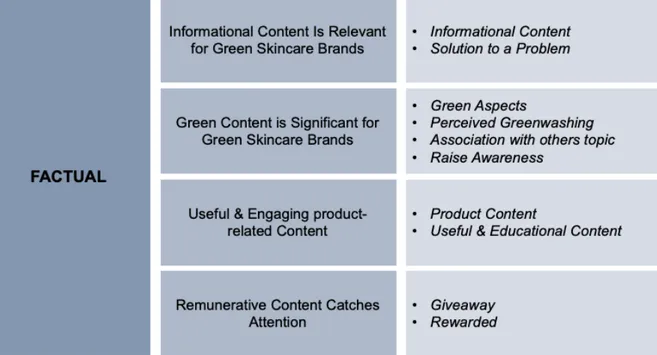

4.3 Factual ... 45

4.3.1 Informational Content is Relevant for Green Skincare Brands ... 46

4.3.2 Green Content is Significant for Green Skincare Brands ... 47

4.3.3 Useful and Engaging product-related Content ... 48

4.3.4 Remunerative Content Catches Attention ... 49

4.4 Summary ... 49

5. Analysis and Discussion ... 54

5.1 Summary of the Final Conceptual Framework of our Study ... 54

5.2 Analysis and Discussion of our Research Question ... 55

5.2.1 Affective ... 55

5.2.2 Identification, Spokesperson & Trust ... 59

5.2.3 Factual ... 66

5.3 Summary of the Analysis and Discussion of Empirical Findings ... 69

5.4 Theoretical Contribution ... 69

6. Conclusion ... 70

6.1 Key Findings ... 70

6.2 Limitations and Future Research ... 71

6.3 Managerial & Societal Implications ... 72

REFERENCES ... 74

APPENDIX ... 102

Appendix 1. Overview of company-created Instagram Posts ... 102

Appendix 2. Interview Guideline ... 110

Appendix 3. Overview of Green Skincare Brands ... 112

List of Tables

Table 1. Overview of Consumer Engagement Concepts ... 5

Table 2. Definitions of Green Products ... 15

Table 3. Definitions of Green Cosmetics ... 16

Table 4. Definitions of Green Aspects in Skincare Products ... 17

Table 5. Definition and Application of Validity and Reliability ... 33

Table 6. Instagram Engagement of our Informants ... 35

Table 7. Overview of Informants ... 37

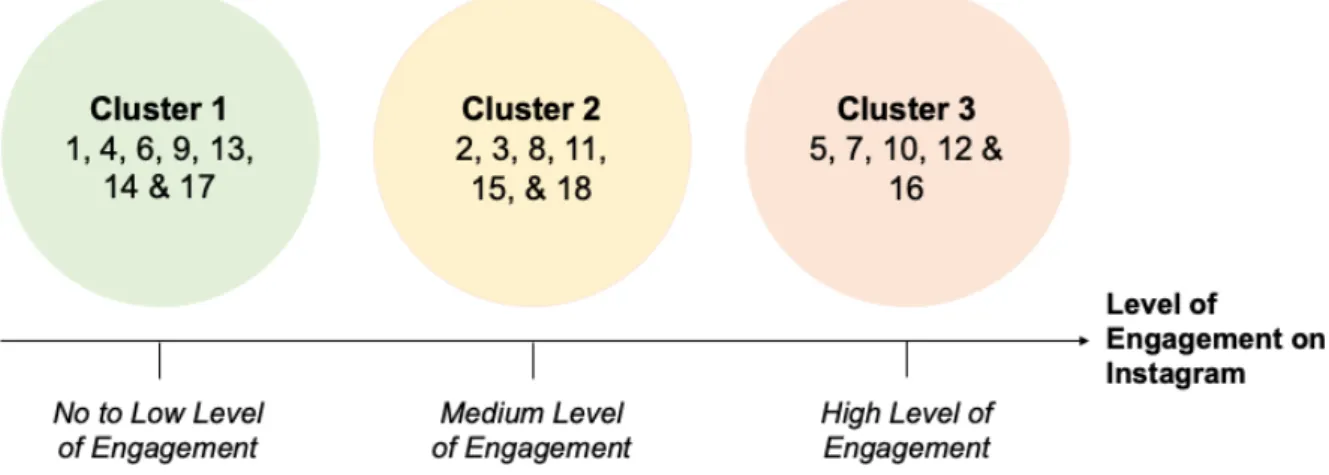

Table 8. Level of Engagement on Instagram ... 50

Table 9. Definitions and Application of Credibility Concepts ... 63

Table 10. Overview of Green Skincare Brands ... 112

Table 11. Overview of Informants‘ Level of Engagement on Instagram ... 113

List of Figures Figure 1. Proposed Framework of Appeals Driving Consumer Engagement ... 21

Figure 2. Overview Themes, Categories and Subcategories ... 36

Figure 3. Identified Clusters within their Level of Engagement on Instagram ... 50

Figure 4. Importance of Themes and Categories for Cluster 1 ... 51

Figure 5. Importance of Themes and Categories for Cluster 2 ... 52

Figure 6. Importance of Themes and Categories for Cluster 3 ... 53

Figure 7. Conceptual Framework of Appeals Driving Consumer Engagement ... 54

Figure 8. The Appeal Affective driving Affection and Activation ... 59

Figure 9. The Appeal Identification, Spokesperson & Trust driving Cognitive Processing and Affection ... 65

Figure 10. The Appeal Factual driving Cognitive Processing, Affection and Activation ... 69

List of Abbreviations

CBE Consumer Brand Engagement CE Consumer Engagement

IST Identification, Spokesperson & Trust RQ Research Question

1. Introduction

The following chapter introduces the reader to the background and problem definition of our study as well as the purpose. Thus, we give an overview of how our study contributes to existing literature and end with delimitations.

1.1 Background and Problem Definition

Since the beginning of the year 2021, more than 55% of the world population is actively using social media (Datareportal, 2021). Given technological advancements and users of social media strongly relying on visual content, the way consumers interact with companies and brands has been revolutionized (Chuang, 2020; Kujur and Singh, 2020; Tsai and Men, 2013). Thus, consumers are more active in expressing their opinions (Chuang, 2020). Due to social media’s participative and interactive nature, engaging with consumers online represents a fundamental factor for a successful implementation of marketing strategies and a company's success (Evans and McKee, 2010; Tsai and Men, 2013).

To communicate successfully with an audience, message appeals are used as they support information processing and hence represent a significant component in persuading through social marketing campaigns (Garretson Folse et al., 2012). Appeals can therefore be explained as a way of showing consumers some type of encouragement or benefit, thus, to give them a reason to pay attention to a brand/product (Kotler and Keller, 2008, as cited in Wu and Wang, 2011). Aristotle introduced an interplay of three elements, on which rhetoric relies, which are logos, ethos and pathos. Logos refers to rational appeals, thus the argument or truth of a message. Ethos covers reliability and sympathy hence a culturally and logically convincing message, whereas pathos refers to emotional appeals, so on an affective dimension (Stucki and Sager, 2018). However, as the social media environment varies from traditional media, understanding which appeals to use through social media content to evoke consumer engagement (CE) is essential (Dolan et al., 2019). This leads CE to have a significant influence on the relationship of consumers and companies (Chuang, 2020). Consequently, scholars as well as practitioners show rising interest in this topic, as it provides company benefits, such as increasing sales and improving profitability (Brodie et al., 2013; Kujur and Singh, 2020). However, according to Kaplan and Haenlein (2010), engaging on social media is not a simple task for companies, requiring new strategies. Nevertheless, such strategies will not be

successful unless marketers understand how to develop social media content effectively to drive CE, which remains unstudied (Dolan et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2018). Especially since companies have less control over available information about them online, and the webpage is only one of many sources (Kaplan and Haenlein, 2010), providing the right content is even more important.

Especially for millennials social media represents a source for entertainment, social networking and information gathering (Moore, 2012). The millennial generation is defined as people born between 1982 to 2000 (Beseler, 2016; US Census Bureau, 2015). In particular one platform comprises a similar age range of users up to 34 years, especially from 25-34 years, which is Instagram (Tankosvka, 2021a). Instagram is a social networking site (SNS) that accounts for one of the most popular ones worldwide, with more than a billion users registered (Tankovska, 2021a; Abed, 2018). Particularly regarding image-based networks, Instagram is the most prominent one in comparison to various other SNS platforms, as it provides a setting where consumers’ brand engagement can develop in a highly unique way (Okazaki et al., 2019; Kocak et al., 2020). According to Kocak et al. (2020), the usage of Instagram is crucial for brands, since it generates the greatest engagement next to Facebook, Pinterest or Twitter. On social media, different popularity trends can be noticed (Zhang et al., 2015). One trend that continues to rise is sustainability. Not only has the demand grown for it, but also the consumers’ willingness to spend more on sustainable products (Nielsen, 2020; Sahota, 2014; Valentine, 2019). Particularly millennials consider environmental and social aspects when consuming products (Euro RSCG Worldwide, 2011; Shaburishvili, 2019). To attract the interest of this generation, brands have to consider environmentally friendly actions as well as promote the benefit of them in terms of appeals (Naderi and Van Steenburg, 2018). Sustainability is also a key factor for European consumers in the cosmetics industry (ProFound, 2020), which is highly relevant as the European cosmetics market represents the world’s largest market (Cosmetics Europe, 2018). To illustrate, 75% of millennials prefer to purchase green beauty products in 2017 (Gran, 2017). Regarding sustainable cosmetics, the demand has increased, leading sales in Europe to grow at around +7% per year from 2014 to 2019 and to an expected reach of 5 billion euros by 2023 (Gallon, 2019). Consequently, this trend has led to a more mainstream view of sustainable, fair-trade, vegan, organic, and ethically sourced cosmetics (ProFound, 2020; Pop et al., 2020). In 2019, skincare displayed the greatest share of cosmetics in the European market (Ridder, 2021).

Especially millennials are the ones buying the most skincare compared to others, particularly women (Bradtke, 2019). Hence, this study concentrates on female European millennials in connection to green skincare.

Social media has highlighted the emergence of skincare, since skincare brands need a strong visual presentation (Sandel, 2020). Visuals have almost always been present in skincare advertisements, since they are noticed more than text (Hingorani, 2008). Instagram for instance is one the most visual SNS platforms (Kocak et al., 2020), leading it to be the most relevant field for this research. However, despite the increasing importance of CE on Instagram, limited studies investigate which appeals actually drive it (Rietveld et al., 2020; Dolan et al., 2019). Furthermore, there are no studies present to our knowledge in this specific context.

1.2 Purpose and Research Question

CE on Instagram can be triggered by various appeals. Green skincare brands have the option to implement several appeals to advertise them in posts, as for instance rational or emotional ones (Rietveld et al., 2020; Dolan et al., 2019). Nevertheless, different concepts can drive consumer brand engagement (CBE), such as including green aspects into the branding strategy, like vegan (Franzino and Aral, 2020). However, we will specifically focus on appeals driving CBE, as this has not been researched in the context of green skincare brands on Instagram so far. Thus, our research question is as follows.

RQ: How can green skincare brands drive CBE on Instagram?

As this question is rather broad, several interesting routes can be taken in terms of answering it. Nevertheless, our specific interest lies in appeals, since how to engineer company-created content has not been studied intensely and is highly relevant for brands nowadays to achieve aforementioned benefits. Consequently, the purpose of this study is to understand which appeals drive millennials’ CBE of green skincare brands on Instagram. Thus, particularly green company-created content is examined. The thoughts and opinions of female European millennials are analyzed, and we then conceptualize CBE by creating our own framework.

1.3 Significance of the Study

This study contributes with knowledge to research in CBE on Instagram in connection to the green skincare industry. It helps companies and marketers within the skincare sector understand the mindset of female European millennials and how CBE is affected by various appeals in the context of sustainability. Companies can benefit from our research by understanding which appeals to use to drive engagement on Instagram. Besides, this study contributes to existing literature regarding CBE, since Instagram and the setting of green skincare brands have obtained less attention in research (Hollebeek et al., 2014, Dolan et al., 2019). As understanding how to create successful company-created content remains unstudied (Lee et al., 2018), we contribute with new and relevant findings in this field. Moreover, the current study serves as a foundation and provides comprehensive insights for further research.

1.4 Delimitations

Concerning delimitations, the generalizability of our findings is not given since our study is qualitative. Besides, since the study is based on female millennials in the European skincare market, the findings are only applicable for this specific geographical area.

2. Theoretical Background

Following, the chapter introduces the reader to relevant concepts respecting our purpose and ultimately concludes with our proposed framework.

2.1 Consumer Engagement

2.1.1 CE in the Marketing Literature

Over the past years, research has focused significantly on CE from a practical and academic perspective (Leckie et al., 2016; Harrigan et al., 2017). Since the construct of engagement is connected to several meaningful brand performance measures, for instance customer involvement and sales growth, it has been attracting growing attention (Bijmolt et al., 2010; Bowden, 2009; Harrigan et al., 2017; Kumar et al., 2010; van Doorn et al., 2010). Additionally, the idea of engagement is considered a promising construct to interpret and predict the results of consumers’ behavior (Avnet and Higgins, 2006a,b; Hollebeek et al., 2014).

However, in the field of marketing, CE illustrated a comparatively new construct in the beginning of the 21st century (Hollebeek et al., 2014) in comparison to other research disciplines such as organizational behavior or educational psychology, where the initial concept is drawn from (Bowden, 2009; Brodie et al., 2011). Nowadays, due to technological innovations and particularly the rise of mobile applications, CE has gained importance (Tarute et al., 2017). Within marketing, engagement has been studied, for instance related to retail (Vivek et al., 2014) or services (Jaakkola and Alexander, 2014). Despite the short period of time the construct has been investigated in the marketing context, various studies address CE from several perspectives. Besides, literature contains qualitative and quantitative studies as well as conceptual contributions (Dessart et al., 2016). In Table 1, a summary of the reviewed concepts of engagement in marketing literature is illustrated to enhance the reader's understanding. Furthermore, this table guided us to define and conceptualize CBE and specify our own working definition.

Table 1

Author(s) Research

Type Concept Definition Dimensionality

Bowden 2009

Conceptual Customer Engagement

"The term engagement is conceptualized in this paper as a psychological process that models the underlying mechanisms by which customer loyalty forms for new customers of a service brand as well as the

mechanisms by which loyalty may be maintained for repeat purchase

customers of a service brand." (p. 65) Multidimensional Brodie et al. 2011 Conceptual Customer Engagement

"...is a psychological state that occurs by virtue of interactive, co-creative customer experiences with a focal agent/object (e.g., a

Multidimensional: (1) cognitive, (2) emotional, (3) behavioral

brand) in focal service relationships." (p. 260) Brodie et al. 2013 Empirical: Qualitative Consumer Engagement "Consumer engagement is a multidimensional concept comprising cognitive, emotional, and/ or

behavioral dimensions, and plays a central role in the process of relational exchange where other relational concepts are engagement antecedents and/or consequences in iterative engagement processes within the brand community." (p. 107) Multidimensional: (1) cognitive, (2) emotional, (3) behavioral Hollebeek (2011a) Conceptual Customer Brand Engagement

"The level of an individual customer’s motivational, brand-related and context-dependent state of mind characterised by specific levels of cognitive,

emotional and behavioural activity in direct brand interactions." (p. 790) Multidimensional: (1) cognitive, (2) emotional, (3) behavioral Hollebeek (2011b) Empirical: Qualitative Customer Brand Engagement

"The level of a customer’s cognitive, emotional and behavioral investment in specific brand interactions." (p. 555) Multidimensional: (1) cognitive, (2) emotional, (3) behavioral Hollebeek et al. (2014) Empirical Consumer Brand Engagement

"A consumer's positively valenced brand-related cognitive, emotional and behavioral activity during or related to focal consumer/brand interactions." (p. 149) Multidimensional: (1) cognitive processing, (2) affection, (3) activation

Mollen and Wilson (2010) Conceptual Online Engagement

"The cognitive and affective commitment to an active relationship with the brand as personified by the website or other computer-mediated entities designed to communicate brand value." (p. 923) Multidimensional: (1) cognitive, (2) affective Phillips & McQuarrie 2010 Empirical: Qualitative Advertising Engagement

"Modes of engagement are routes to persuasion." (p. 371) Multidimensional: consumers act to ads: (1) Feel, (2) Identity, (3) Immerse, (4) Act Schaufeli et al. (2002) Empirical: Quantitative

Engagement "Affective-cognitive state that is not focused on any particular object, event, individual, or behavior." (p. 74) Multidimensional: (1) cognitive, (2) affective van Doorn et al. (2010) Conceptual Customer Engagement

"...as the customers’ behavioral manifestation toward a brand or firm, beyond purchase, resulting from motivational drivers." (p. 253) Multidimensional: (1) customer goals, (2) scope, (3) form or modality, (4) valence and (5) nature of its impact

Note. Summary of the reviewed concepts of CBE in marketing literature, including the concept,

definition and conceptualization. Does not provide a complete list of all existing CBE definitions in marketing literature.

With regards to investigating CBE in the social media environment of Instagram, the CBE framework of Hollebeek et al. (2014) is noteworthy since it provides the conceptualization of CBE and develops a CBE measurement scale in the context of social media. Besides, the framework offers further details about the dimensionality and character of the engagement construct as well as about the interactive consumer/brand relationship in a broader sense (Hollebeek et al., 2014). However, concerning our purpose, Hollebeek et al.‘s (2014) framework does not look at appeals

driving CBE, in particular not in the context of green skincare brands on Instagram, thus our study further investigates this.

2.1.2 Definition of CE

The conceptualization of CE tends to integrate an object, for example a product or brand, and a subject like a consumer (Hollebeek, 2011a,b) and differs in intensity levels (Lee et al., 2018; Tafesse, 2016). Additionally, engagement is also related to a specific context (Hollebeek, 2011a) and takes place in interrelation to consumption that goes beyond the purchase (van Doorn et al., 2010).

Yet relatively few definitions of customer/consumer engagement do exist by authors in the scientific literature of marketing (Brodie et al., 2013), especially regarding our context of Instagram as illustrated in Table 1. Thus, to develop an own working definition is needed.

The current definitions vary between “‘engagement’, ‘brand engagement’, ‘brand community engagement’ and ‘consumer engagement with a product’“ (Dessart et al., 2016, p. 402). The variability of the concept results from either diverse engagement foci or the absence of a consent terminology (Dessart et al., 2016) (Table 1). According to Phillips and McQuarrie (2010) “modes of engagement are routes to persuasion” (p. 371). Schaufeli et al. (2002) characterized engagement as an “affective-cognitive state that is not focused on any particular object, event, individual, or behavior” (p. 74). In contrast, Hollebeek (2011b) defines customer brand engagement as “the level of a customer’s cognitive, emotional and behavioral investment in specific brand interactions” (p. 555). Regarding the definition of Hollebeek et al. (2014), CBE also refers to a customer’s activities “...during or related to focal consumer/brand interaction” (Hollebeek, 2014, p. 149). Moreover, van Doorn et al. (2010) specifies customer engagement as “...beyond purchase...” (p. 253). Considering the conceptual framework of the engagement process of Bowden (2009), CE is considered as a psychological process including affective and cognitive facets. Mollen and Wilson (2010) illustrate CE interrelating to an online environment and describe the idea as “a cognitive and affective commitment to an active relationship with the brand as personified by the website or other computer-mediated entities designed to communicate brand value” (Mollen and Wilson, 2010, p. 923).

2.1.3 Conceptualization of CE

With regards to the above-mentioned definitions, the conceptualization of CE has been developed differently (Table 1). Most of the relevant marketing research constructs are conceptualized on the basis of a multidimensional model including cognitive, emotional and behavioral dimensions (Bowden 2009; Brodie et al., 2013; Hollebeek, 2011a,b). However, for instance the online dimensions of Mollen and Wilson (2010) comprise

active sustained cognitive processing, experimental value and instrumental value. Van

Doorn et al. 's (2010) dimensions of CE include customer goals, scope, form or

modality, valence and nature of its impact.

Concerning the CBE dimensions in connection to social media, Hollebeek et al. ‘s (2014) study identified the subsequent three elements: cognitive processing, affection and activation (Hollebeek et al., 2014). Cognitive processing is described as “a consumer’s level of brand-related thought processing and elaboration in particular consumer/brand interaction” (Hollebeek et al., 2014, p. 154). The term affection indicates “a consumer's degree of positive brand-related affect in a particular consumer/brand interaction” (Hollebeek, et al., 2014, p. 154). The last dimension represents activation which refers to “a consumer’s level of energy, effort and time spent on a brand in particular consumer/brand interaction” (Hollebeek et al., 2014, p. 154). Those dimensions guided us in our study, as stated in chapter 2.7.1.

2.2 Appeals of company-created Content on Instagram

To understand which appeals drive millennial’s CBE of green skincare brands on Instagram, several appeals can be considered (Rietveld et al., 2020; Dolan et al., 2019; Correia Loureiro et al., 2020).

Based on Aristotle's rhetoric elements ethos, pathos and logos (Stucki and Sager, 2018), in the traditional media context, various studies distinguish between rational and emotional appeals (Wu and Wang, 2011). Within the background of social media, according to previous studies, Dolan et al. (2019) differentiate social media content between emotional (entertaining or relational content) and rational (informational or

remunerative content) (Dolan et al., 2019).

Emotional refers to personal, employee, customer relationship, brand community,

experiential or cause-related (Shahbaznezhad et al., 2021). Hereby, emotional appeals can either generate negative feelings such as guilt or fear, or positive emotions

for instance humor or love (Zhang et al., 2014). By this, to engage with consumers on social media (Rietveld et al., 2020) and attain a positive response towards a brand or product, emotional appeals, especially image-based appeals, can be used (Goldberg and Gorn, 1987). In connection to social media, emotional content can be distinguished by being entertaining or relational. Entertaining content is described as the scope of entertaining and fun content to the media user and relational content represents the scope of content to meet the needs for social interaction and integration of consumers (Dolan et al., 2019).

Rational indicates functional, educational, informational or current events

(Shahbaznezhad et al., 2021). Thus, informational appeals are described as being pertinent and factual information about a brand presented in a transparent and consistent manner (Puto and Wells, 1984). Based on arguments, the beliefs of a consumer towards a brand can be changed through informational appeals (Chandy et al., 2001). The social media setting distinguishes rational content between

remunerative or informational content. Remunerative content refers to the scope of

content about monetary rewards or incentives. This content refers to promotional strategies or direct calls to purchase (Swani et al., 2013) as well as brand resonance and sales promotional content (Füller et al., 2006). Informational content represents the scope of informative and useful information provided to the user (Dolan et al., 2019).

These two types do not represent our appeals but instead introduce different possible appeals to the reader, which could be detected along the study process. However, we assume to find similar appeals, since those types also refer to social media content.

2.3 The Rise of Social Media 2.3.1 Online CE on Social Media

Every second, around 15 ½ users join a social media platform (Kemp, 2021). To illustrate, compared to the last decade, the user base of such platforms has almost tripled in size (Dean, 2021). Consequently, regarding digital activities, the utilization of social media is one of the most popular ones worldwide (Tankovska, 2021b). Not only consumers network online, but also companies. Especially in Europe, more than half of the companies have at least one SNS account, with around 86% of them using it to market products and build their image (Eurostat, 2020). Although companies need social media to stay present and relevant for the consumer, it comprises many

downsides (Ryan, 2019). To illustrate, consumers become addicted to constantly checking their feeds and additionally are facing constant competition concerning their self-image. Especially filters and photoshopped images can lead to mental health issues, like self-esteem problems and depression (Dalomba, 2020; Ryan, 2019). Since online media are not experienced in the same way as traditional media, like print (Calder et al., 2009), it is necessary to address CE in an online setting. Online is perceived to be more interactive, participatory and active as well as more social in nature, as one of its uses is communicating and sharing, which multiplies social engagement (Calder et al., 2009; Mathwick, 2002). The increasing number of always-connected SNS platforms allows consumers to have more power in controlling their consumer experiences and to decide when and where to engage, but also offers companies endless possibilities to engage with consumers (Marbach et al., 2019). Thus, compared to other advertising platforms, marketers can engage consumers in a more interactive and intimate manner (Tsai and Men, 2013). Dix (2012) as well as Schultz and Peltier (2013) studied CE particularly in the social media context. Barger et al. (2016) extended this research and operationalized “consumer engagement as a set of measurable actions that consumers take on social media in response to brand-related content” (p. 270), which can be reactions such as liking, commenting (Doyle et al., 2020; Rietveld et al., 2020), saving (Boosted, n.d.) and sharing posts or following a profile (Valentini et al., 2018). In contrast, online CE is defined by Leong et al. (2019) as “a degree of affective, behavior and cognitive attachment of an individual to a certain services or company through online social media” (p. 799). Further, according to Topal et al. (2020) online CE can be explained as the “online experience and interaction that consumers have through social networks with businesses” (p. 465), which goes beyond the relationship of buyer and seller.

2.3.2 Instagram

Being a visual-based platform, Instagram has quickly developed as a modern marketing medium and accounts for the number one photo-sharing application (Chen, 2018; Blystone, 2020). The extraordinary success of this SNS platform is supported by the fact that the content shared in the form of photos and videos account for key social currency drivers online (Career, 2020; Hu et al., 2014). Companies have the opportunity to advertise through this medium in various ways. For instance, the feature stories can be used, where moments can be shared for 24 hours, as well as advertising

through photo, video, carousel, collection or explore posts (Instagram Business, 2021a, Instagram, 2020). With the introduction of Instagram Reels in 2020, a new possibility to create or discover entertaining and short videos was added to the SNS platform (Instagram, 2020). Additionally, sponsored posts are another way of advertising, where an influencer shares content on their account for a company in exchange for a specific compensation (Gotter, 2020). Posts can also be unsponsored, when influencers tag or name a company voluntarily, although this still accounts for advertisement (Warren, 2019). Influencers are online opinion leaders and significant promoters of services and products in various business areas, which can influence the opinions of others (Zak and Hasprova, 2020).

Instagram is visited by its users to get inspiration and learn about things they are passionate about, including content from brands and businesses (Instagram Business, 2021b). Thus, also marketers recognized the value of such a platform, because of its significant role in creating new business opportunities as well as reaching and keeping customers (Alkhowaiter, 2016). Most importantly though, according to Alkhowaiter (2016), public needs can be identified through SNS platforms. For companies to appear on the feed of Instagram users, engagement is the most important factor to do so. Instagram is known to have changing and specific algorithms. As of now in 2021, content is prioritized by the algorithm that achieved the most engagement, which can be in the form of likes, reshares, comments and views for videos (Warren, 2021). Instagram recognized the tremendous potential of the platform for commerce and pushes the rise of social commerce through the creation of new shopping features (Magento, 2018). Brands can now embed their products on Instagram Shops, giving them the possibility to tag the exact products, which provides consumers with information and details about them, the price and a link for instant buying (Instagram Business, 2021c). Since particularly skincare brands are highly visual, Instagram has developed to be a valuable tool to drive brand awareness, sales and engagement (Dreghorn, 2020). However, in terms of sustainability, this is controversial, as sustainable consumption means consuming more attentively or even reducing or avoiding consumption completely (Scott and Weaver, 2018).

2.4 Definition of Sustainability

The term sustainability is denoted widely different among various authors and organizations due to multiple information sources (Bom et al., 2019; Glavic and

Lukmann, 2007). Sustainability has been applied in various contexts and different disciplines. Depending on the context referring to an economic, social or ecological perspective, the meaning of the term differs (Brown et al., 1987). This results in various new sustainability definitions or the extension of existing ones and leads to an assumption of an estimated number of 300 definitions regarding sustainability or sustainable development. Consequently, this causes confusion since the terms are either alike or unsystematic, or only differentiate slightly from each other (Glavic and Lukmann, 2007; Johnston et al., 2007). To define sustainability provokes challenges, such as a diversity of synonyms as well as a lacking standard definition that is utilized in literature (Moore et al., 2017). However, the first addressed and widely acknowledged definition of sustainability was developed from the United Nation World Commission on Environment and Development, often referenced as Brundtland Commission, in 1987 (Belz and Peattie, 2013; Bom et al., 2019; Johnston et al., 2007). In the report Our Common Future, the sustainability concept is characterized as to “meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (Brundtland, 1987, p. 6). As an extension to the definition of the Brundtland commission, in 1994, Elkington introduced the concept of the Triple

Bottom Line of sustainability (Elkington, 2004). The Triple Bottom Line measures a

company’s success and performance by including the financial, environmental and social/ethical performance of a business. The concept offers companies the possibility to meet the needs of all key stakeholders including suppliers, customers, employees and communities (Norman and MacDonald, 2004). Consequently, the sustainability definition of Brundtland Commission and the concept of the Triple Bottom Line guided us in our study.

2.5 Green Skincare 2.5.1 Skincare Industry

For most people in the world their appearance is important. In particular women are highly aware of their face (Jan et al., 2019). Thus, in today’s society, cosmetics are of essential character, since using cosmetic products refines the appearance, enhances the mood while offering an opportunity of social expression (Bom et al., 2019; Cosmetics Europe, 2018). The industry of personal care and cosmetics consist of products related to beauty, well-being and health. The product range includes skin and

hair care, body and oral care as well as decorative cosmetics and perfumery (Cosmetics Europe, 2018).

Since our skin represents the largest human organ and plays a significant role in the nervous and immune system as well as acts as a defense against external influence, cosmetics have been used to maintain skin health (Thukaram, 2019). Particularly, skincare is utilized to protect and take care of the skin to prevent wrinkles, dry skin or irritations, amongst others (MarketResearch.com, 2021). Skincare products include products in form of lotions, powders and creams for body, hand and facial care as well as make-up remover and depilatories (Fortune Business Insights, 2018; MarketLine Industry Profile, 2019). Skincare refers to improving the appearance of the skin (Chin et al., 2018). However, concerns arise when using skincare extensively as chemical ingredients of products can be absorbed by the skin and taken up by the body (Darbre and Charles, 2010). This can lead to an increased risk of cancer obliged to hormones, such as breast cancer (Rylander et al., 2019). Therefore, the demand for green skincare increases, as stated in the following chapter.

2.5.2 Trends of Sustainability in The Skincare Industry

The rising awareness for the environment has changed consumers’ thinking and buying behavior concerning sustainable products. This has influenced consumers to use sustainable cosmetic products (Boon et al., 2020; Chin et al., 2018; Cutolo, 2021; Hsu et al., 2017), boosting the growth of the global cosmetics market (GlobalNewswire, 2021). Also, companies recognized this change, and many have implemented sustainability programs, aiming to become more efficient with resources and reduce their environmental impact (CBI, 2020a). In the worldwide market, the fastest growing sector of sustainable cosmetics is skincare, compared to other cosmetic products (Chin et al., 2018), such as natural hair care, makeup, sunscreen, fragrance or nail care (Gran, 2017). Consumers now seek healthy skin rather than covering it with heavy cosmetics (Espitia, 2020). One factor that has pushed skincare into the spotlight is social media, with users displaying their skincare routines and consumers showing increasing interest in natural beauty and self-care (Sandel, 2020). Leaving no barriers between consumers and companies, consumers can draw critical attention towards unsustainable practices of companies but also show their support towards sustainable companies (Conard, 2018). However, this trend has also led companies to increasingly greenwash, which means that brands claim to be green when in reality they are not

(Biologi, 2019). Companies are not necessarily enhancing their products’ ingredients and health benefits but instead investing in smart marketing (Botani, 2019). Hence for consumers it is increasingly difficult to trust green brands (Rud, 2020).

As mentioned in chapter 2.4, the term sustainability has been used broadly in literature. A term that is often used as a synonym to sustainable is green (Pizam, 2009; Han et al., 2009; Miller and Szekely, 1995; Savage, 2009; Mamun et al., 2020), which will therefore be used mainly in this study. Other words that are used similarly in literature are environmentally-friendly, eco-friendly or environmentally responsible activities (Kalafatis et al., 1999; Roberts, 1996; Laroche et al., 2001; Manaktola and Jauhari, 2007). Several authors have described green products in literature, as stated in Table 2.

Table 2

Authors Definition

Ottmann et al. (2006)

Ottman et al. (2006) define green products as “those that strive to protect or enhance the natural environment by conserving energy and/or resources and reducing or

eliminating use of toxic agents, pollution, and waste” (p. 24). Tomasin et al.

(2013)

Tomasin et al. (2013) indicated that “green products are designed to prevent, limit, reduce, and/or correct harmful environmental impacts on water, air, and soil” (p. 274). Peattie (as cited in

Dangelico and Pontrandolfo, 2010)

A product can also be characterized as green when its societal and environmental output during production, usage and disposal is in comparison to competitive or conventional products considerably refined and improving. Thus, different life cycle phases have to be considered in this context (Dangelico and Pontrandolfo, 2010).

Note. This table does not show all existing green product definitions given in literature, but

instead provides an insight of how they can be defined.

As a form of green products, also green cosmetics can be defined differently, as highlighted in Table 3.

Table 3

Authors Definition

Chin et al. (2018)

According to Chin et al. (2018), green cosmetics can be described as products “made from natural ingredients without any chemical agents, artificial coloring, or other substances” (Chin et al., 2018, p. 4).

Quoquab et al. (2020) and Mamun et al. (2020)

Quoquab et al. (2020) and Mamun et al. (2020) describe

cosmetics as green when they contain natural ingredients, thus when they are chemical-free.

Hsu et al. (2017) and Boon et al. (2020)

Green skincare is outlined by Hsu et al. (2017), as not containing synthetic chemicals but instead as products that contain naturally derived ingredients as well as preservatives or humectants. The research of Boon et al. (2020) supports this statement

concerning natural ingredients of a green skincare product.

Note. This table does not show all existing green cosmetics definitions given in literature, but

instead provides an insight of how they can be defined.

Green in the context of skincare products has not been studied widely in literature (Mamun et al., 2020), thus the provided definitions in literature lack depth and precision. This is because there are various aspects that can be relevant when explaining green skincare which do not only regard natural ingredients but many more aspects. Thus, in the following chapter we will provide an overview of possible green aspects.

2.5.3 Possible Aspects of Green Skincare Brands

As mentioned previously, the skincare industry as well as the demand for green options is growing. Trending terminologies have emerged that are used by companies to label their brand (Mukti, 2019). However, since many different labels are used under the umbrella term green, it is important to understand what the differences are and mean (Roestorf, 2019). This is especially important, since these terms differ from company to company, allowing the issue of greenwashing to emerge (Fleming and Rosenstein, 2020), because there is no official regulation (Levesque-Tremblay and Petruzzelli, 2020). Because of the existing great number of green terms (Franzino and Aral, 2020;

Fleming and Rosenstein, 2020; Cosmetics Europe, 2019a; Mukti, 2019), we present eight aspects used in literature, to introduce the reader to the topic and give examples of what green can mean in terms of skincare (Table 4). This is necessary to be able to comprehend how we use several terms in the following chapters. Therefore, definitions are given for some of the most recurring terms regarding our context (Atzori, 2021; Amly, 2020; Bisharat, 2018; Franzino and Aral, 2020; ProFound, 2020; Salehaldin, 2020) and ones claimed to be influential green, ethical and eco-friendly aspects by Euromonitor International (Szalai, 2017).

Cosmetics Europe (2019b) highlights green behaviors in all parts of a product’s lifecycle. Hence it is important to consider not only ingredients, but also the manufacturing process and packaging up to the consumer use (Cosmetics Europe, 2019b). The following aspects partly represent these steps in the lifecycle of a product. As they are used differently in literature, they are considered individually in this overview, thus a green skincare product does not have to incorporate all of these terms to be green.

Table 4

Aspect Description

Cruelty-free Cruelty-free implies that no testing on animals has been done regarding the ingredients of a product or the product itself (Cruelty Free International, n.d.). Hence cruelty-free skincare products refer to ethical consumerism (Fux and Čater, 2018).

Vegan Vegan is a term that describes the abstinence of the usage of animal-derived products (Braunsberger and Flamm, 2019; The Vegan Society, 2021). Thus, such products avoid for instance pollution, deforestation or water pollution as animal agriculture causes such

environmental problems (Fleur & Bee, 2019; PETA, 2019). Water efficient Products are water efficient when requiring less water

during use, such as a two-in-one shampoo (Cosmetics Europe, 2019b). Additionally, water efficient products can be ones that do not contain water themselves (Daniel, 2017) or consider less use of water in the production

(School of Natural Skincare, 2020). By 2025 it is expected that water shortages will greatly impact around 2 billion people, thus reducing water waste in the beauty industry is highly relevant (Isler, 2020).

Sustainably sourced ingredients

While sourcing ingredients, actions are taken to ensure the conservation of biodiversity or the minimization of deforestation (Cosmetics Europe, 2019b).

Natural ingredients Ingredients considered as natural are sourced from nature, such as plants, minerals, or animal by-products, such as aloe vera, chamomile or beeswax (Boon et al., 2020; Franzino and Aral, 2020). Thus, those products do not include chemicals and hence will not be released into the environment which is beneficial (Naturals Begin, n.d.). Organic Ingredients Organic ingredients describe ingredients which are free

from pesticides and organically grown, excluding harsh chemicals (Gross, 2016; Franzino and Aral, 2020). Fragrance free Fragrance-free cosmetics are ones that contain 0%

fragrances in order to reduce possible allergies and effects such as asthma or migraine (Cabaleiro et al., 2012). As wastewater treatments are not able to break down fragrance chemicals, they negatively impact the marine environment, such as fish and other wildlife (Niven-Phillips, 2019).

Recyclable/Recycled Packaging

Recyclable packaging defines a packaging which can be recycled and reused (Green Processing Company Inc, 2019). Recycled packaging means choosing materials for the packaging which have already been recycled, such as a shampoo bottle made from recycled plastic (Murray and Schroeder, 2020). In Europe in particular, there is a legal obligation to recover and recycle packaging waste

(Cosmetics Europe, 2021). Thus, through such packaging, the carbon footprint will be reduced and disposal becomes easier (Green Business Bureau, 2017).

Note. This table does not show all existing green aspects and their definitions given in

literature, but instead provides an insight of some of the most recurring ones.

As green terms differ in their definitions, we will only refer to the provided definitions of Table 4, when naming them later in the study. Since we are focusing our study on

Europe, cruelty-free is one aspect a brand needs to include, as animal-testing has been banned in the EU since 2013 (European Commission, n.d.). We consequently developed our own definition specifically for this study and thus define green skincare brands as:

Green skincare brands are those which are cruelty-free, as they are based in Europe and contain additionally one or more green aspects provided in Table 4.

2.6 Millennials as the Ideal Target Group

In literature, different studies investigate millennials in the context of sustainability (Bollani et al., 2019; Schoolman et al., 2016). This is because millennials grew up facing realities like climate change, rising sea levels and species extinction, arguably leading them to be the generation most concerned about social and cultural issues as well as environmental stability (Lee et al., 2020; Shaburishvili, 2019). Thus, they display a generation of people engaged to drive change and desiring sustainability in a mainstream culture (Shaburishvili, 2019).

Especially concerning clean, healthy and natural skincare and beauty products, millennials are leading the trend (Boon et al., 2020; Masory, 2019). This generation favors skincare over make-up, because they practice self-care and self-love with the use of it (Dimuro, 2020). Because they are open-minded to innovative products, they are willing to experiment with new skincare and take their skincare very seriously (Goldsmith, 2020). Around 73% of female millennials are actively seeking for products that are more natural (Megan, 2020). Thus, millennials have reformed the personal care and beauty industry drastically, by relying on social media to get the “instagramworthy glow” (Masory, 2019, para. 1). In particular women invest in green skincare products and love to share their favorite ones as well as their rituals on platforms like Instagram, because they are strongly mindful of their overall well-being and health (Bradtke, 2019; Goldsmith, 2020). Not only can consumers share green behaviors on social media, but also companies. To illustrate, a company has used it to educate consumers through a video to reduce the water use by suggesting practical options (Cosmetics Europe, 2019a). As the so far most technologically savvy generation, millennials are never far from a device that connects them to the internet (Black Bear Design, n.d.). For them, SNS platforms are not just for communication but function as a one-stop-shop for any of their everyday needs (Smart Insights, 2020). However, millennials are contradictory in their behavior, on one hand favoring green

products/brands and on the other hand consuming the internet extensively and spending much on expensive hardware. They typically have large monthly data plans and own many technological devices (Deloitte, 2015), which are known to have a negative impact on the environment (Okafor, 2020). Instagram is the most used social media platform by millennials, and it is said that this generation interacts more on SNS platforms than in real life (Benson, 2018). This is highly relevant for companies. With 25 million business profiles and over two million advertisers on Instagram, this platform has emerged to be one of the main revenue generating tools for companies (Whitney, 2021).

Given the fact that female millennials are not only the generation most involved in sustainability concerns but also represent the largest group of users of skincare as well as Instagram, they are the most suitable group for our study and will therefore be the focus of our research.

2.7 Conceptual Framework of our Study

As mentioned in chapter 2.1.2, we introduce our own working definition of CBE and conclude with illustrating our research approach in a proposed conceptual framework.

2.7.1 CBE Working Definition

Regarding the above-mentioned definitions and conceptualizations of the CE construct, Hollebeek et al. (2014) represents a predominant study in the context of social media. Consequently, cognitive processing, affection and activation will be incorporated partly into our own definition and framework to conceptualize CBE. Thus, we define CBE in our study as the following.

Consumer Brand Engagement is a multidimensional construct including cognitive processing, affection and activation, leading to an interaction between the user and a brand on the visual-based SNS platform Instagram in terms of liking, commenting, sharing or saving company-created content or following a brand.

2.7.2 Proposed Conceptual Framework

Concerning our purpose, thus, to understand which appeals drive CBE, our following framework is used to conceptualize and build a base to answer our research question. Therefore, appeals will be examined in terms of driving the CBE conceptualization, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Note. Appeals driving Consumer Brand Engagement. The right side of the proposed

framework, thus the CBE conceptualization including cognitive processing, affection and activation, is adapted from “Consumer Brand Engagement in Social Media: Conceptualization, Scale Development and Validation” by L. D. Hollebeek, M. S. Glynn and R. J. Brodie, 2014,

Journal of Interactive Marketing, 28, p. 157. Copyright 2013 by Direct Marketing Educational

Foundation, Inc., dba Marketing EDGE.

Since our study revolves around the opinions and thoughts of female European millennials, this framework will be finalized after conducting research and analyzing data. Thus, a definite model will be provided in chapter 5.1.

3. Method

This chapter introduces a critical assessment of the methods chosen to fulfill the purpose of our study. How we were influenced by philosophy in the way we approached our study purpose and collected and analyzed data will be discussed in detail.

3.1 Research Philosophy

Choosing a method for this research has been influenced by our interest in the field of CBE on social media, particularly Instagram. In the context of the skincare industry and sustainability, it has led us to find a gap in literature. After gathering a theoretical background and formulating our research question, our strategy to answer it needed to be unrestricted. An open approach allowed us to explore and understand the nature of our problem. Thus, choosing a relevant research philosophy is of importance. According to Rubin and Rubin (2005), a research philosophy forms the way individuals study their world. By whom and how the research is conducted as well as the degrees

of dispassion and involvement is indicated by the research philosophy (Rubin and Rubin, 2005). In marketing research, positivism, realism, interpretivism and pragmatism are the four main research philosophies (Saunders et al., 2016).

Interpretivism describes an approach where the “aim is primarily to explore and

understand the nature and interrelationships of marketing phenomena” (Malhotra et al., 2017, p. 175). As we hope to gain new insights and understand the nature of CBE on Instagram and ultimately seek to portray this phenomenon in the context of green skincare brands, we considered this philosophy as appropriate for our study. Trauth (2001) stated that “interpretivism is the lens most frequently influencing the choice of qualitative methods” (p. 7). This influenced our choice of research method hence we decided to conduct interviews. Further, examining a rather small sample in detail instead of a large sample, is the focus of investigation (Malhotra et al., 2017). In our study, this is shown in our sample size of 18 informants. Instead of searching for the average, interpretive researchers seek for the detailed and specific and attempt to develop an understanding based on those specific views (Rubin and Rubin, 2005). By formulating interview questions evolving around the informants’ specific opinions with the aim to build an understanding based on those, we are led by the interpretivist approach. Being a subjectivist and humanistic approach, this philosophical school allows us to view our informants in individual contexts to elicit information and gain access with the best means (Nunan et al., 2020). In this study, this is given by the fact that each individual is interviewed separately. Additionally, being guided by the interpretivist approach, we were able to interpret our informants’ opinions, which ultimately influenced our study results.

3.2 Research Approach

Induction is a type of reasoning involving the observation of a repeated combination of

events, which can often be legitimized through the interpretivist approach. Thus, no framework or a limited form is used, so that the researcher is not restricted (Bryman, 2016; Malhotra et al., 2017). Since in our study we want to base our framework on the opinions and thoughts of female European millennials and hence aim to understand them, we are led by the inductive approach. Even though inductive arguments do not logically imply a conclusion, detected patterns through observation can be used to draw conclusions (Dowden, 2021), which is what we aimed at. Hence data will be collected and function as a base for exploring a phenomenon, identifying patterns and

themes and consequently creating a conceptual framework (Saunders et al., 2016). However, data is never free of theory, since prior knowledge inevitably affects the collection and observation of data (Kennedy, 2018). As given in chapter 2, we intensely researched literature regarding our context, thus our prior knowledge affects our data collection. Consequently, previous theory can loosely frame or guide the research but instead of focusing on testing this theory the focus lies on seeking a true reality in a deliberate situation (Carson et al., 2001). In our study, we decided to be loosely framed by Hollebeek et al.’s (2014) research in our CBE conceptualization and framework. The opposite of induction is the deductive approach, where based on a theory, predictions are made, which are then tested through experiments or observation (Bryman, 2016). Conclusions are hence made upon established and measurable ‘facts’, which are tested in the form of hypotheses (Malhotra et al., 2017). As for this study no predictions are made nor are we testing hypotheses, but instead developed a research question, we are led by an open empirical approach.

Induction allows us to interpret the research results and extract meaningful insights and explanations to answer our research question. Particularly our data collection and analysis have been influenced by induction, thus in the way we created open-ended interview questions, but also our coding process. For instance, chapter 4 is the result of an inductive data collection and analysis process, as we identified patterns and interpreted the empirical data from our interviews to draw conclusions from recurring themes. Additionally, our results guided us in chapter 5 in terms of finding relevant theory for analyzation and interpretation, where linkages were detected with our frame of reference in chapter 2, but also additional literature. Chapter 2 therefore only served as a first introduction into our context, while we developed our own theory and framework in chapter 5.

However, elements of deduction have been borrowed in this study. Chapter 2.2 includes theoretical elements, as we know from previous research that companies can use certain appeals to communicate effectively. Nevertheless, they do not represent theory that is tested in this study and instead are only introduced with the purpose of giving examples to the reader, thus they are in no way a complete list of existing appeals. Additionally, the choice of using Instagram post examples, as explained in chapter 3.8, is inspired by deduction, as the four appeals introduced in chapter 2.2 have influenced our selection of pictures. Nevertheless, the use of visuals in this study is relevant, since Instagram is a visual-based platform. Since we made sure to choose

a variety of pictures regarding topics and emotions, as elaborated in chapter 3.8, induction affected our choice as well. Moreover, the interview guideline was informed by theory which represents another deductive element. Nonetheless, our open-ended questions offered our informants the opportunity to express opinions freely (Kumar, 2011; Misoch, 2014; Saunders et al., 2016).

Consequently, by researching inductively, we had the opportunity to develop a framework out of the analyzed findings, as other researchers have done it similarly (Hollebeek et al., 2014, Calder et al., 2009). Thus, although our study is partly inspired by deduction, the main approach of this study is induction, as it resulted in the creation of our own framework, based on our empirical findings, in chapter 5 and finally affected the conclusion of this research.

3.3 Research Purpose

The manner of formulating a research question refers to the research purpose, as this ultimately involves the choice of the design. Three main types exist, which are exploratory, explanatory and descriptive (Saunders et al., 2016).

Concerning the research design, an exploratory design was chosen. This is an evolving and flexible approach in order to understand marketing phenomena which are constitutionally complex to measure (Malhotra et al., 2017). Since we are focusing on a gap in literature, this approach provided us with the opportunity to explore and find new valuable information in our research field. Thus, the aim was to discover new relationships and ideas (Sontakki, 2010). Comparably to Brodie et al. (2013), we in our research wanted to study the nature of CBE in particular on Instagram, which is why we argue for exploratory being the appropriate research design. By this, we could gather the best possible information on this subject, observe and consequently draw conclusions from our empirical findings. Additionally, the discovery process occurring in exploratory studies, is often guided by research questions in contrast to hypotheses, which are used in causal research (Babin and Zikmund, 2016). This is exemplified in this study by our research question, which is stated in chapter 1.2.

3.4 Research design

The general plan regarding the handling of answering a research question is called a research design, which can be divided into a quantitative, qualitative or mixed-method approach (Saunders et al., 2016).

With regards to our chosen research purpose, a tool that is used to conduct exploratory research is qualitative research (Silver et al., 2013), which is commonly associated with the philosophy of interpretivism (Saunders et al., 2016). Qualitative research is used when wanting to find out about a problem which cannot be verbalized, thus “non-routine problems that have no clear solution” (Silver et al., 2013, p. 56). Hence a qualitative approach allowed us to comprehend the complexity of our context and to facilitate it. The emphasis of qualitative research is therefore to understand rather than to simply measure (Carson et al., 2001; Nair, 2009), which was our goal concerning our purpose. Thus, empathizing with consumers to understand their meanings regarding brands, products or other marketing factors was the aim (Nair, 2009). Nevertheless, qualitative research can hardly be generalized, as it is not based on statistical controls or random samples (Niaz, 2007). Thus, our findings are specifically relevant for understanding our peculiar context. For the exploratory research design, and hence a qualitative approach, usually a small sample size is chosen (Malhotra et al., 2017). This is exemplified in this research by a sample size of 18 informants. Methods used can consequently be focus groups, interviews, ethnography or grounded theory and are dependent on observation, description and categorization (Silver et al., 2013).

In terms of collecting data in qualitative research, interviews are the most extensively used method and its popularity is led by the fact that they are perceived as ‘talking’ and talking is natural (Doody and Noonan, 2013; Griffee, 2005). Additionally, it is a uniquely powerful and sensitive method for capturing the lived meaning and experiences of an individual’s everyday life, allowing them to share their personal perspective in their own words (Brinkmann and Kvale, 2018), which is what we aimed at. By this, memories, feelings and interpretations can be revealed that otherwise could not be discovered or observed (Carson et al., 2001). Since observations in studying inductively are the base to then draw conclusions, we argue that interviews were a suitable research method. This allowed us to answer our research question and to understand the opinions our informants have regarding our topic. Thus, facial expressions, body language, the tonality of the voice and overall mood as well as reactions of the informants were observed, enabling us to interpret and analyze their responses on a deeper level (Abrams et al., 2015).

However, this method contains some disadvantages that need to be considered. One considerable downside is the researcher bias, which can occur when framing the

questions but also when interpreting the responses (Kumar, 2011). Since we are both from Germany, we could have been biased regarding our cultural background in interpreting the findings. In addition, according to Saunders et al. (2016), an interviewee or response bias can occur. Although in principle respondents are willing to participate, they might choose not to discuss or reveal certain aspects of a subject if they feel like it is sensitive information they do not wish to share (Saunders et al., 2016). As our research revolves around delicate subjects, respectively sustainability and skincare, this could represent a limitation of the study. This is because sustainability is a topic that affects everyone and every individual can contribute to it, leading to an occurring phenomenon called sustainability shaming, where people shame others for in their opinion unsustainable actions (Klimatrådet, 2020; McMullin, 2019). Additionally, as there is a great association of skin diseases and psychiatric disorders (Dalgard et al., 2015), also skincare is a delicate subject. Thus, informants could feel vulnerable when answering questions concerning these topics. What could have been done differently regarding these issues is to additionally conduct a survey, where respondents could be guaranteed anonymity to provide trustworthiness of the medium and reduce the response bias (Bryman, 2016). However, a survey alone would not have allowed us to interpret body language and facial expression and hence would have limited our results.

3.5 Justification of the Research Approach

In literature, several different approaches to understand what drives CE have been used, ranging between research types such as conceptual or empirical qualitative and quantitative (Hollebeek et al., 2014; van Doorn et al., 2010; Brodie et al., 2013). To discover and further explore relevant aspects regarding CBE, Hollebeek et al. (2014) used an exploratory qualitative approach and developed a scale for specific social media settings. Brodie et al. (2013) also followed a qualitative approach by selecting netnography and qualitative in-depth interviews as their research methods to explore CE in a brand community environment online.

Nevertheless, there is a gap in literature concerning CBE in the context of green skincare brands on Instagram. Since our aim was to discover new information and create a framework, the choice of an interpretivist, inductive, exploratory, qualitative approach was the most suitable for this study.