School of Education, Culture and Communication

UGH, DO WE HAVE TO?

An experimental study investigating students’ attitudes

towards English and their results in a reading comprehension

test

Degree projects in English Michelle Johnsson

Supervisor: Karin Molander Danielsson

Examiner: Duygu Sert

School of Education, Degree Project

Culture and Communication ENA314 15 hp

Autumn 2020

ABSTRACT

The aim of this study is to investigate 1) students’ attitudes towards English, 2) students’ attitudes towards reading in English and 3) if there is a correlation between students’ attitudes and their results in a reading comprehension test. In total, 39 students from three different classes volunteered for this study. The data were collected by using a questionnaire regarding students’ attitudes towards English and reading in English as well as by letting the participants take part in a reading comprehension test. The results show that students’ attitudes towards English does not necessarily play a part in how well they perform in a reading comprehension test.

_______________________________________________________

Keywords: Reading comprehension, EFL, ESL, upper secondary school, Sweden

Table of contents

1 Introduction ... 1

2 Background ... 2

2.1 Terms and definitions ... 2

2.2 The English language learning situation in Sweden ... 2

2.2.1 Reading comprehension in Swedish upper secondary school ... 3

2.3 Students’ attitudes regarding the English language and reading in English ... 5

2.4 Reading in the EFL classroom ... 6

3 Method ... 8

3.1 Data collection method ... 9

3.2 Selection of participants ... 10

3.3 Ethical considerations ... 10

3.4 Analytical procedure ... 11

4 Results ... 11

4.1 The students’ attitudes towards English ... 12

4.2 The students’ attitudes towards reading in English ... 12

4.3 The results of the reading comprehension test ... 13

4.3.1 Low, intermediate, and high score ... 14

4.4 Comparison between students’ attitudes towards English and their test scores 14 4.5 Comparison between students’ attitudes towards reading in English and their test scores ... 15

4.6 Comparison between year 1 and year 2 ... 16

5 Discussion ... 17

6 Conclusion ... 20

6.1 Limitations of the study ... 21

6.2 Future research ... 21

References ... 22

Appendix 1 – Questionnaire ... 24

Acknowledgements

I would first like to thank my supervisor Karin Molander Danielsson. She has supported me throughout my entire study and shown great interest in my study. She has also steered me in the right direction when she thought I needed it. I would also like to thank my husband for being there for my ups and downs during this process. Lastly, I would like to thank my dear friend and future colleague Emma Nilsson for giving me a shoulder to cry on when needed and for providing me with support and laughter.

1 Introduction

The frequency with which English is used in Sweden has increased the last couple of years and students in Swedish upper secondary school are incorporating more English words and slang into their everyday life in the form of loan words, abbreviations, and such, (Swedish National Agency for Education1, 2011, p. 1). The increased use of English among young people in Sweden has led to a more positive attitude towards English (Sundqvist, 2010, p. 103).

Given the importance to reading comprehension in national and international testing, a study of the possible correlation between attitude to English, reading and reading comprehension would be valuable. However, I have not been able to find such research regarding the situation in Sweden. I have found research from other countries that point to a connection between reading and the development of English skills which says that enhanced reading skills could help students further develop other aspects of the English language. Asraf and Ahmad (2003) claim “free voluntary reading or sustained independent reading results in better reading comprehension, writing style, vocabulary, spelling, and grammatical development” (p. 83). Thus, by helping students become more motivated to learn English and read texts in English their English skills might develop more than they otherwise would.

The aim of this study was to investigate Swedish students' attitudes towards English as a second language and their attitudes towards reading texts in English. My aim was also to investigate the participating students’ results in a reading comprehension test to see if there was a possible correlation between the students’ attitudes towards English and towards reading texts in English as well as their results in the reading comprehension test. By

investigating the potential relationship between these two aspects of learning a language one could possibly find methods to engage and motivate students in their English language development.

In order to investigate the possible correlation between students’ attitudes towards English, their attitudes towards reading in English and their results in a reading comprehension test the following research questions were posed:

1: What are the participating students’ attitudes towards the English language? 2: What are the participating students’ attitudes towards reading in English?

3: What is the relationship between the participating students’ attitudes towards the English language, towards reading in English and their results in a reading comprehension test?

2 Background

In this section I will present some terms and definitions that I believe will need some further explanation. Thereafter, I will present the English language situation in Sweden followed by previous research that is relevant for my own study.

2.1 Terms and definitions

EFL means English as a Foreign Language. This is regard to learners of English who have

another language as their first language and learn English for foreign situations.

ESL means English as a Second Language. ESL is regarding learners who learn English as a

Second language and use English in more formal situations as well as informal ones. Not merely as a language to use when going abroad and such.

The sources used in this essay use both terms; however, I believe that the term ESL is more fitting when it comes to the English language situation in Sweden. There are a couple of reasons why English in Sweden could be said to be a second language; namely the fact that English is a core subject in compulsory school as well as in upper secondary school. Another reason why English in Sweden could be said to be a second language is because in Sweden movies and TV-shows from England and America have Swedish subtitles instead of voice dubbing.

2.2 The English language learning situation in Sweden

In order to explain the English language learning situation in Swedish upper secondary

school, an explanation of the Swedish school system is necessary. The Swedish school system is constructed of two parts, namely compulsory school, and upper secondary school. The Swedish compulsory school starts with year one when children are six-seven years old, and they graduate from compulsory school when they finish year nine at the age of 15-16. Students are then allowed to choose if they would like to advance to upper secondary school

in which case most students do. Students then apply to a program of their choosing and it could either be a vocational program or a theoretical one. Upper secondary school in Sweden lasts three years, and students graduate when they are 18-19 years old.

English language learning has been a compulsory part of the Swedish school system since 1962 (SNAE). With the new curriculum in 1962 (lgr 62), English became compulsory for students in year four through year seven. With the next curriculum in 1969 (lgr 69), English became compulsory for students in year three all throughout the end of compulsory school, year nine. Finally, since the 1994 curriculum (lpo 94), the English subject is taught to students from year one to year nine (SNAE, 2011). In Swedish upper secondary school, the English subject is compulsory during the first year in a course called English 5, and then students are offered to study two optional English courses: English 6 and English 7. Students are only allowed to apply for English 6 if they achieved a passing grade in English 5, and for English 7 if they achieved a passing grade in English 6.

Since English TV-shows and movies are rarely dubbed, students meet English from an early age. Therefore, their English skills develop from an early age. Research shows that students who watch English TV-shows and movies regularly have a greater chance of developing their English skills regarding speaking, listening, pronunciation and vocabulary acquisitions

(Albiladi, Abdeen & Lincoln, 2018, p. 1570).

2.2.1 Reading comprehension in Swedish upper secondary school

The Swedish curriculum states that the students should be able to further develop their English skills regarding content of communication, production, interaction, and lastly

reception. These are some of the aspects regarding reception that students should be able to do after the English 5 course which can be found in the curriculum:

• Coherent spoken language and conversations of different kinds, such as interviews.

• Literature and other fiction.

• Texts of different kinds and for different purposes, such as manuals, popular science texts and reports.

• Strategies for listening and reading in different ways and for different purposes. (SNAE, 2011, p. 7)

It also states that students should be given the opportunity to further develop their

understanding of spoken and written English as well as to be able to interpret content (SNAE, 2011, p. 2). In Swedish upper secondary school, English reading comprehension is also part of the so-called core content2. Furthermore, reading comprehension is part of the national tests, and the tests are compulsory for students studying English 5 and English 6. Having good reading comprehension skills could help students manage in society more easily since “managing in society depends on having good understanding of the written language” (SNAE, 2016, p. 8). Reading comprehension could also help students be able to think and discuss critically about the society we live in (SNAE, 2016, p. 8).

However, what defines reading comprehension is something that can be widely discussed. Some researchers define reading comprehension as the ability to read and decode written texts. This could lead to students possibly getting a broader understanding of what they have read (SNAE, 2016, p. 17). Note that the researchers who SNAE mentions do not regard audiobooks and such as part of the term reading comprehension (SNAE, 2016, p. 15). Then, there are some researchers who argue that audiobooks and such should be included as valid tools to be used together with printed books when it comes to reading comprehension (SNAE, 2016, p. 22). According to SNAE, researchers define reading comprehension as “an

interaction between the reader and the text” (SNAE, 2016, p. 15).

In this degree project, I have focused on the definition provided by SNAE that reading comprehension is the ability to read and decode written texts. The text the participants will work with is a written text of an old national test for the English 5 course. I have also interpreted the interaction between the reader and the text (SNAE, 2016, p. 15) as an active reading session, where the students are aware of what they are reading, why they are reading the chosen text and then answering questions regarding the text.

The importance of reading and reading comprehension in compulsory school is emphasized by SNAE (2016, p. 11) and I would argue that it is of the same, if not more, importance in upper secondary school. SNAE states that students in compulsory school start off their reading as “learning to read” which then develops to “read to learn” (SNAE, 2016, p. 22).

SNAE also states that students know how to read but that they rarely fully comprehend what they have read (SNAE, 2016, p. 10). One example of this exact problem comes from one of my own supervised placements as a teacher student. The students, who were in the third grade in Swedish upper secondary school, had an English 6 lesson and were preparing for a debate about gun control in the USA. My mentor gave them a piece of paper stating if they were for or against gun control. Almost everyone read “against guns” not “against gun control” and started preparing for the debate as if they were against guns.

Students in upper secondary school should be able to “read to learn” and their reading comprehension skills should have developed further. Therefore, there is a possibility that reading English texts in upper secondary school helps students develop their English language skills more than it otherwise would.

2.3 Students’ attitudes regarding the English language and reading in

English

When it comes to learning EFL/ESL, there are certain factors that teachers must consider. An important factor is attitude regarding learning the language. If students have a positive attitude towards learning a language, the chance of a greater outcome is higher than if students have a negative one (Azarkia et al. 2015, p. 2516).

As stated, motivation is what helps students learn and understand English; motivation is what drives the students forward in their language development. Bin-Tahir et al. (2017) found, for example, that students become more motivated when there is a sense of competition, when the students have a desire for being the best in class (p. 87). This form of external motivation could help students become more motivated to learn English. On a different note, Lennartsson (2008) found in her study that social factors do not seem to play as big of a part as previous research might state regarding students’ achievements but what seems to be the key factor when learning a language is the so-called inner motivation (p. 20).

Students might need to have a certain purpose for learning a second language; otherwise it might be hard to motivate students (Lennartsson, 2008, p. 21). Similarly, Habók and Magyar (2019) also found that students’ motivation towards learning English and reading is what helps students become more inclined to learn more English (p. 13). Students need to be motivated in order to learn a language effectively and the source of motivation could be

different depending on the student itself. One motivating factor that seems to be of importance to the majority of students is the future. Students might want to work abroad and have

international connections regarding jobs; therefore, English could help them communicate with others and they can use the language as a lingua franca (Saleem, 2014, p. 30).

Another motivational factor seems to be success which is considered to motivate students to further develop and learn their second language. However, complete failure or complete success could also de-motivate students (Ahmed, 2015, p. 15; Parkinson & Reid-Thomas, 2000, p. 9). If students are completely successful in their learning, they can be demotivated since there is not enough of a challenge for the student in question.

Sani and Zain have also shown that motivation and attitude seems to be of importance for EFL/ESL learners when it comes to reading in English (Sani & Zain, 2011, p. 248). For example, they found that their participating students’ attitudes towards reading in English was rather low and that they believed that reading in English was a waste of time (p. 248). Sani and Zain believed that students’ unwillingness to read could be a response to the texts being irrelevant for the students (p. 250).

2.4 Reading in the EFL classroom

Communicative skills such as speaking, and writing have taken a more prominent place in the Swedish ESL classroom and due to this, literature has become less important. The Swedish curriculum for the English 5 course has three distinct parts regarding reading and reading comprehension whereas speaking and writing has seven parts (SNAE, 2011, p. 7). Literature and reading, however, could play a big part when it comes to learning a language. Reading is a rather complex process and reading could help students develop an interest in lifelong learning (Goodman, 1967, as cited in Wankah Foncha, 2014, p. 680).

Another way to look at this, however, is that literature in the EFL/ESL classroom could be too difficult for students to understand. If students do not understand what they are reading, they can be demotivated to continue to read. Literature that is being brought up in the EFL

classroom should therefore neither be too long or too difficult for the students (Bakken & Lund. 2017, p.82; Asraf & Ahmad, 2003, p. 91; Bin-Tahir et al, 2017, p. 86). This could be a rather steep obstacle to overcome for teachers. Students who are at a different level regarding their English language skills require different texts of various difficulties. Using literature in the EFL/ESL classroom could therefore be rather tricky (Bakken & Lund, 2017, p. 83).

Similarly, Parkinson and Reid-Thomas (2000) bring up the fact that literature is difficult. However, they claim that by using literature that is difficult for the students, they will be challenged and their knowledge regarding the English language will hopefully develop further (p. 10). On a different note, Parkinson and Reid-Thomas claim that literature can be too remote for students to fully understand the reason for reading certain texts (p. 11). They claim that students may or may not be able to fully understand how people lived during the

medieval time or why characters in books make certain choices depending on where in the world they live. This can lead to students being confused and therefore become demotivated when it comes to reading texts in English.

As previously mentioned, literature in the EFL/ESL classroom could be tricky but Parkinson and Reid-Thomas (2000) bring up several benefits, as well as problems, with teaching

literature in a second language. They mention “cultural enrichment” as one of the benefits for teaching literature in the EFL/ESL classroom. Although there is always cultural enrichment when dealing with literature, Keshavarzi (2012) also states that literature lets students take part in different, cultural parts of the world that are otherwise hard to obtain by other means (p. 555). Parkinson and Reid also claim that literature lets students come in contact with texts and writing that is considered “good” writing (p. 9). Furthermore, they state that by reading texts and literature which are considered to have “good” writing, students can further develop their own writing skills (p. 9). Similarly, Keshavarzi mentions that literature can be beneficial for students’ own language learning since literature lets students come in contact with various forms of language (p. 555).

However, if the texts that are being brought up in the classroom involve the students on a personal level, they might be more motivated to read (Keshavarzi, 2012, p. 555; Bakken & Lund, 2017, p. 83). In other words, discussing and talking about what they have read could be a way to make students more motivated to read. Similarly, Appleman et al. (2016) claim that literature lets learners construct different social worlds that can help them further understand the different parts of the world we live in (p. 10).

As stated, motivation is a key factor when learning a language and how teachers motivate students to read in the EFL classroom is what Bakken and Lund investigated in 2015. Their findings show that the teachers in their study, who were teaching in lower upper secondary school, use literature to help motivate their students. They also found that the teacher’s own

experience regarding reading had a big impact on their students. They had one teacher who had a very positive experience when it comes to literature and learning English, so she made sure to use literature frequently in her classroom. Although Bakken and Lund’s study were focused on teachers’ attitudes to reading English texts, it could be relevant for this study since they found a possible correlation between attitudes and literature use. Furthermore, teaching and learning is a two-way operation. Perhaps teachers’ attitudes towards reading and literature could affect their students’ attitudes towards reading in English.

Hedman’s study from 2018 connects to Bakken and Lund in as much as it investigated Swedish upper secondary students’ attitudes towards reading in English and found that most of the students in her study had a positive attitude towards reading in English (Hedman, 2018, p.18). She also found that the majority of students who attended a vocational program do not use any form of reading strategy when reading texts in order to better understand the text they have read (p.15). Furthermore, she found that students who considered themselves as good readers in Swedish did not believe that reading in English was hard either (p.18), meaning that there could possibly be a correlation between students’ reading skills in their first language and their second or third language.

Azarkia, Aliasin and Khosravi performed a study in 2015 where they investigated what the relationship between Iranian EFL learner’s attitudes towards English and their results in a reading comprehension test was. I have used their research as an inspiration regarding my own research since I am curious to see if I will get similar results as they did. The correlation of EFL/ESL learner’s attitudes and reading comprehension could be of great importance. EFL/ESL learner’s attitudes could have a big impact on their ability to learn the English language (Azarkia, Aliasin & Khosravi, 2015). This sort of investigation is lacking when it comes to a Swedish context and could therefore be of great importance in order to further motivate students’ willingness to learn English.

3 Method

In this section I will present everything concerning my method for collecting and analysing my data. I will first present my reasoning behind choosing the method I have chosen followed by my selection of informants. I will also present my procedure when sorting the data

3.1 Data collection method

I visited three different classes at the same upper secondary school in Sweden during November of 2020. In order to answer the first two research questions, I chose to use a questionnaire (see appendix 1) which consisted of ten questions and were all about students’ attitudes towards the English language both as a subject in school but also as a language in general. In the questionnaire, I also had questions regarding their attitudes towards reading texts in English, both in school and during their free time. I felt that having questions

regarding their attitudes towards English as a subject as well as their attitudes towards English in general was of importance since students might experience a difference between the two. In order to find the answer to the third, and last research question, a reading comprehension test (see appendix 2) was handed out. The reading comprehension test was the first half of an old national Reading test for the course English 5 where the lowest score was a zero and the highest score was a nine. The reason for giving the students only half of the reading

comprehension test was due to lack of time. The original test had 17 questions, both multiple-choice questions as well as open ended questions where students need to write the correct answer; however, during the national test, students have 90 minutes to answer the test whereas I had 50 minutes with each class. Therefore, in order not to stress the students, I chose to include only the first half of the test which still consisted of both types of questions. Among the of eight different old national Reading tests available on University of

Gothenburg’s website (2021) “The summer of ´63” was chosen namely because this was the only test that had both multiple-choice test as well as open ended questions. The combination of both types of questions could help determine if the students filled in the questions

randomly and skipped the open questions, or if they tried their best at answering the questions correctly.

A questionnaire is beneficial when performing a quantitative study as well as when investigating the possible relationship between two variables (Denscombe, 2017, p. 23). Quantitative studies also rely on the researcher’s impartiality which is natural and of great importance regarding both the questionnaire as well as the reading comprehension test. It is important that the researcher does not influence the participants when answering the

questionnaire (Denscombe, 2017, p. 25) as well as their answers regarding the reading comprehension test.

I collected the data in two batches in order to get as many informants as possible. I was

present in the classroom both times, which according to Denscombe (2017, p. 33) makes more participants answer the questionnaire that is handed out to them.

3.2 Selection of participants

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic during 2020 I decided that a convenience selection of participants was most fitting since I was not sure that I would be welcomed to perform my research in another school other than where I have had my placements as a teacher student. I contacted my mentor at my field school and asked permission to come and perform my study during her lessons. I performed a test with one of her classes and at the same time I performed a test with a class of her colleagues. A few weeks later I performed another test with another class of my mentors.

In total, I got 39 participants from three different classes. Out of these 39 participants, 25 were in the second grade and 14 were in the first grade, all of the participants studied the same English course: English 5. There were a total of three females and 36 males, and all of the students attended a vocational program. At first, I wanted to perform this study in a theoretical program as well as a vocational program and compare the results, but as previously

mentioned, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, this was not as easy as one could have wished. Therefore, in order to avoid not being able to collect any data, I decided to perform my study in a vocational program where I knew I would get results.

When I presented the study and the test to the students, I told them that this was an old national test for the English 5 course. I did this in order to perhaps make the students more motivated to perform well on the test as well as possibly making them see this as an opportunity to practice their English.

3.3 Ethical considerations

This study has been conducted in agreement with the ethical principles of social studies (Vetenskapsrådet, 2017). I informed the participating students that their participation was voluntary and that if they chose not to participate, they could withdraw their participation at any time. They were assured that they could refuse to answer a question and they were also made aware that they would be completely anonymous. I informed them that their answers could not be tracked back to them and that their answers would be used only in this study.

3.4 Analytical procedure

After collecting the data, I first sorted the tests and questionnaires into two piles, the test and the questionnaire were attached to each other: year one and year two separately in order to have the possibility to compare them, even though that was not the main purpose of this study. After that, I corrected each test according to the answer key provided by SNAE. Each question was worth one point, meaning that the lowest possible score was a zero and the highest possible score was a nine. Then I sorted each year into three sub-piles. These three sub-piles were: students who had a positive attitude towards English, students who had a negative attitude towards English, and students who were undecided. Thereafter, I sorted the three piles into three more sub-piles: positive attitudes towards reading, negative attitudes towards reading, and students who were undecided. By undecided, in both cases, I mean students who answered, for example, that they like English as a subject in school but that they would rather spend their time on other subjects than English.

After sorting the results into these piles, I started looking at the results of the reading comprehension test in each pile and highlighted those who had high scores, between seven and nine, or those who had a low score, between one and three. I also highlighted those who had high results in the pile of students who had a negative attitude towards English or low results in the pile of students who had a positive attitude towards English. Then, I started transferring my findings into charts which will be presented in the result section of this study. After having collected and analysing the data, a simple item analysis was carried out to investigate what types of questions, if any, the participating students struggled with as well to investigate if the students tried to do their best at answering the test or not and if they simply did not care. An item analysis allows the researcher to investigate both students’ answers to certain questions as well as the test questions provided in the test (Siri & Freddano, 2011, p. 189). However, since the purpose of this study is not about analysing test questions and given answers, the item analysis information will not be provided in detail but instead will be

mentioned of when necessary.

4 Results

The result section will first present the results of the questionnaire. The questions consisted of questions such as if the enjoyed learning English, if they thought of English as an important part of upper secondary school and if they enjoyed reading texts in English. Thereafter, I will

present the test results of the students who had a positive attitude towards English, a negative attitude towards English and the students who were undecided. Followed by a presentation of the test results of the students who had a positive attitude towards reading in English, the students who had a negative attitude towards reading in English and students who were undecided. Lastly, I will present a comparison of the test results between the students in year 1 and year 2.

4.1 The students’ attitudes towards English

The results of the questionnaire show that most of the students had a positive attitude towards English.

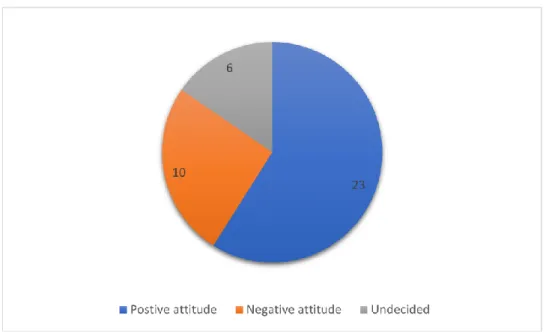

Figure 1: Students' attitudes towards English

Out of the 39 participants, 23 students had a positive attitude towards English, 10 students had a negative attitude towards English, and 6 students were undecided regarding their attitude towards English. The students who were undecided claimed that they enjoyed English as a subject but would rather spend their time on other subjects than English.

4.2 The students’ attitudes towards reading in English

The questions regarding students’ attitudes towards reading in English where questions such as if they enjoyed reading texts in English both in their free time and in school, also questions regarding their thoughts of reading as a method of learning English.

Figure 2: Students' attitudes towards reading in English

As can be seen in Figure 2, most of the students had a negative attitude towards reading in English. 23 out of the 39 participants had a negative attitude towards reading in English. 10 had a positive attitude, and 6 were undecided. The students who were undecided claimed that they believe that reading is an important aspect of learning a language but would rather not read to improve their English skills.

4.3 The results of the reading comprehension test

The average score of the entire group of participants in the reading comprehension test was five.

There was a wide spread of results, from one to eight. The most frequent result was a seven that was achieved by ten students followed by a score of six which was achieved by seven students and more than half of the students scored a five or higher. The median result of the entire group was six.

4.3.1 Low, intermediate, and high score

The frequencies of each tier: low, intermediate, and high scores, is presented in figure 4 below.

Figure 4: Low, intermediate, and high score

Almost half of the students had an intermediate score between four and six. 14 out of the participants had a high score between seven and nine and 8 students had a low score between one and three.

4.4 Comparison between students’ attitudes towards English and their test

scores

The average score among the students who had a positive attitude towards English was five and the average score among the students who had a negative attitude towards English was also five. The average score among the undecided students was four.

Figure 5: Comparison between students’ attitudes towards English and their test scores

The highest score among students with a positive attitude towards English was eight which was also the case among the students with a negative attitude towards English. Interestingly, the lowest score among the students with a positive attitude was one which was also the case among the undecided students whereas among the students who had a negative attitude towards English the lowest score was three.

4.5 Comparison between students’ attitudes towards reading in English

and their test scores

The average score among the students who had a positive attitude towards reading in English was six and the average score among students who had a negative attitude towards reading in English was five which was also the case among the undecided students.

Figure 6: Comparison between students’ attitudes towards reading in English and their test scores

The highest score among the students who had a positive attitude towards reading in English was eight, the same as among the students who had a negative attitude towards reading in English. The lowest score among the students who had a positive attitude towards reading in English was one, once again the same as among the students who had a negative attitude towards reading in English. The highest score among the students who were undecided was six and the lowest was two. There was a more concentration of high scores among the students who had a positive attitude towards reading than among the students who had a negative attitude.

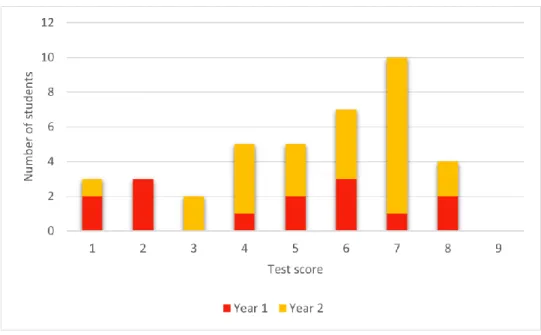

4.6 Comparison between year 1 and year 2

The average score among the students in year 1 was five whereas the average score among the students in year 2 was six meaning that the students in year 2 scored somewhat better than those in year 1.

Figure 7: Comparison between year 1 and year 2

Eight out of the 14 students in year 1 had a score between intermediate and high, and 22 out of the 25 students in year 2 scored between four and eight. There was a wider spread of results among the students in year 1 and a more concentration of higher scores among the students in year 2 with more than half of the students who scored a high score between six and nine. The simple item analysis that was carried out showed that the students in year 1 answered more questions incorrectly than those in year 2.

5 Discussion

The results of the questionnaire show that the majority of the students had a positive attitude towards the English language overall just as Sundqvist (2010, p. 103) mentions in her study. It is worth noting that all but nine students having the same teacher. This could of course have affected the students’ attitudes towards English. Their teacher could possibly have affected their students’ attitudes towards English in a positive way and therefore made them more motivated towards learning English.

The results of the questionnaire also show that the participating students’ attitudes towards reading were low with only 10 students who had a positive attitude towards reading in English. This result correlates to the findings of Sani and Zain (2011) who found that their participating students did not enjoy reading in English (p. 245). The students’ negative attitudes towards reading in English could possibly be because of its perceived irrelevance

and students who believe that reading is irrelevant for them will also not put in the required effort in order to perform well (Sani & Zain, 2011, p. 250).

Students’ attitudes towards English could potentially play a part in how well they perform in school regarding English as a subject (Azarkia, Aliasin & Khosravi, 2015, p. 2516). In their study they found a significant relationship between their participating students’ attitudes and their results in a reading comprehension test. Interestingly, the results of my study show that the average score of the reading comprehension test was the same for the students who had a negative attitude towards English and among those who had a positive attitude towards English. Worth noting though is that there was a rather low number of students who had a negative attitude towards English. Because there were a low number of students with a negative attitude, I cannot with any sense of certainty claim that there is a significant connection between their attitudes towards English and their results in the reading comprehension test.

The students who scored a relatively low score between one point and three points, could perhaps believe that reading is too hard for them, and as Bakken and Lund (2017) mentioned, this could mean that the students in my study simply have given up (p. 86). Not surprisingly, the students in year 2 scored somewhat higher than the students in year 1, this could be due to the fact that they have studied English for an entire extra year and were more comfortable with their English skills. Because the students in year 2 have gotten further into their English 5 course and therefore developed other skills and have had more time to process the English language than those in year 1, the chosen text could for these reasons also have been easier for the students in year 2. This means that the students in year 1 could have been demotivated to perform well if they thought the text was too hard for them which is something that Bakken and Lund (2017) argued was a possible outcome when dealing with literature in the EFL/ESL classroom (p. 82). The higher scores among the students in year 2 could also be due to the fact that they were more used to the test situation than those in year 1. The students in year 2 may have performed more tests than those in year 1 making them more comfortable and knowing what to expect from the test situation.

The item analysis showed that students in year 1 answered more incorrectly than those in year 2. However, the majority of the students who answered incorrectly answered the same wrong answer, proving that they did actually try their best, and that they perhaps thought that the test was too difficult for them. For example, for the first question, while four students in year 1

marked the correct answer, eight students marked B which was incorrect, and two students marked A which was also incorrect. Had the students not cared about the test, and had randomly filled it out, there would have been a wider spread of wrong answers and not so concentrated on the same wrong answers as it happened in my case.

When it comes to attitudes towards reading in English, the results of the students who had a positive attitude towards reading in English seems to be the same as previous research that states that attitude and motivation seems to play a big role when it comes to students’ results in school. Similarly, Azarkia, Aliasin and Khosravi (2015) found that motivation is a key factor when it comes to students’ results and their attitudes towards English and reading (p. 2516). In my study, the students who had a positive attitude towards reading in English all scored high, except for one student who had an intermediate score of five and another student who had a low score of one. What is interesting though is out of the 23 students who had a negative attitude towards reading in English, 18 of them had intermediate or high scores whereas only six of them had a low score. This could of course be because, after all, the majority of the students had a positive attitude towards English in general. The students who had a negative attitude towards reading in English could still enjoy the English language, and therefore be more motivated to perform well.

What also strikes me as interesting and odd is that the average score among the students who had a negative attitude towards English and those who had a positive attitude towards English was the same. According to previous research, students who have a positive attitude tend to perform better in school and have higher results in tests (Azarkia, Aliasin & Khosravi, 2015, p. 2516). This study’s results contradict Azarkia, Aliasin and Khosravi’s findings and this could of course be because I was present in the room and the fact that they were aware that their results were going to be used outside of the classroom, this could have led to the students being anxious and nervous. As Azarkia, Aliasin and Khosravi mention in their study, students who have a positive attitude tend to perform better in tests. Therefore, I believed that the students in my own study who had a positive attitude towards English would perform somewhat better than those with a negative one. I did not, however, expect them to have the same average score.

The students were aware that their results would be presented in this study, but also that their results had nothing to do with their grade in the English 5 course which could have been a factor behind the same average score among students who had a positive attitude towards

English and those with a negative one. Another factor could be because there was a lack of competition among the students, something that Bin-Tahir et al. (2017) claim help students become more motivated and perform better in school and tests (p. 87).

Another potential factor for the relatively low scores among the students who had a positive attitude could be the difficulty level of the chosen text. A text which is too hard for the students to comprehend could demotivate the students (Bakken & Lund, 2017, p. 82). As stated, the text the students had to read was an old national test for their course, English 5. Therefore, the difficulty level should not have been too hard for the students but rather perfect for them. However, the English 5 course in Sweden is normally read during the first year of upper secondary school, then the students choose to move on to English 6 and English 7, respectively. The students who participated in this study read English 5 during the first two years of upper secondary school meaning that the students in year 1 have quite a long way to go before they reach the end of the course, which is when the national test will take place. It is therefore not surprising if the students believed that the text was too hard for them, and that they did not perform well because of this (Asraf & Ahmad, 2003, p. 91; Bin-Tahir et al., 2017, p. 86).

The results of my study show that the students’ attitudes towards the English language and the results in a reading comprehension test could have a connection. However, the results of my study are not clear enough to say that there is a distinct connection between the students’ attitudes and their test results.

My results also show that the majority of the participating students had a positive attitude towards English in general but a negative attitude towards reading in English. Being aware of the potential factors that affect students’ attitudes and the possible connection with their results in a reading comprehension test could be beneficial for teachers in their work towards making students more motivated towards both English and reading in English. However, due to the relatively low number of participants, the results do in no way show how the majority of students at upper secondary school in Sweden would perform in a reading comprehension test in connection to their attitudes towards English in general and reading in English.

6 Conclusion

There could possibly be a connection between students’ attitudes towards English and their results in a reading comprehension test. The results of this study show that the participating

students’ attitudes do not necessarily have to be linked to their results in a reading

comprehension test. There was no difference in the average score between the students who had a positive attitude towards English in general and those who had a negative one. There was only a one-point difference in the average score between the students who had a positive attitude towards reading in English and those who had a negative one. The results show that the majority of the participating students had a positive attitude towards the English language in general but that the majority had a negative attitude towards reading in English. The results also show that students in year 2 performed slightly better in the reading comprehension test than those in year 1.

6.1 Limitations of the study

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic I was only able to conduct my study in three classes in a vocational program. It would, however, have been interesting to investigate and compare the results with students in a theoretical program.

6.2 Future research

In the future, it would be interesting to study several upper secondary schools in Sweden and even around the World and compare the results. An extensive item analysis could also be beneficial in order to further investigate what types of questions referring to which learning objective students struggle with. A comparison between students in vocational programs and theoretical programs could also be beneficial in order to broaden the knowledge regarding this field of research.

References

Ahmed, S. (2015). Attitudes towards English learning among EFL Learners at UMSKAL. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(18), 6 – 16.

Albiladi, W., Abdeen, F., & Lincoln, F. (2018). Learning English through movies: Adult English language learners’ perceptions. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 8(12), 1567 – 1574.

Appleman, D., Beach, R., Fecho, S., & Simon, R. (2016). Teaching literature to adolescents. Routledge.

Asraf, R., & Ahmad, I. (2003). Promoting English language development and the reading habit among students in rural schools through the Guided Extensive Reading program. Reading in a Foreign language, 15(2), 83 – 102. Doi: http://doi.org/10125/66772 Azarkia, F., Aliasin, H., & Khosravi, R. (2015). The relationship between Iranian EFL

learners’ attitudes towards English language learning and their inferencing ability in reading comprehension. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 5(12), 2512 – 2521. Doi: https://doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0512.11

Bakken, S., & Lund, R. (2017). Why should learners of English read? Norwegian English teachers’ notions of EFL reading. Teaching and Teacher Education, 70, 78 – 87. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.11.002

Bin-Tahir, S., Kusumaningputri, R., Salikin, H., & Yuliandari, D. (2017). The Indonesian EFL learners’ motivation in reading. English Language Teaching, 10(5), 81 – 90. Doi: 10.5539/elt.v10n5p81

Denscombe, M. (2017). Forskningshandboken. För småskaliga forskningsprojekt inom samhällsvetenskaperna. Studentlitteratur AB.

Exempel på uppgiftstyper för Engelska 5. (2020, October 5). University of Gothenburg. Retrieved November 4, 2020, from https://www.gu.se/nationella-prov-frammande- sprak/prov-och-bedomningsstod-i-engelska/engelska-5-gymnasiet/exempel-pa-uppgiftstyper-for-engelska-5

Hedman, M. (2018) Reading in English in Swedish classrooms: A study of Swedish upper secondary students’ reading habits and their attitudes towards reading in English. Dalarna University, oai: DiVA.org:du-30095

Keshavarzi, A. (2012). Use of literature in teaching English. Procedia, social and behavioral sciences, 46(1), 554 – 559.

Lennartsson, F. (2008). Students’ motivation and attitudes towards learning a second language: British and Swedish students’ point of view. Växjö University. Lundahl, B. (2017) Engelsk språkdidaktik: texter, kommunikation, språkutveckling.

Studentlitteratur AB.

Saleem, J. (2014). The attitudes and motivation of Swedish upper secondary school students towards learning English as a second language. Malmö högskola. Doi:

http://hdl.handle.net/2043/17579

Sani, A., & Zain, Z. (2011). Relating adolescents’ second language reading attitudes, self-efficacy for reading, and reading ability in a non-supportive ESL setting. The Reading Matrix, 11(3), 243 – 254.

Siri, A., & Freddano, M. (2011). The use of item analysis for the improvement of objective examinations. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 29, 188–197. Doi:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.224

Sundqvist, P. (2010). Extramural engelska – En möjlig väg till studieframgång. Karlstads universitet. Oai: DiVA.org:kau-7087

Swedish National Agency for Education. (2011). Curriculum for the upper secondary school. Retrieved from: https://www.skolverket.se/publikationer?id=2975

Swedish National Agency for Education. (2016). Att läsa och att förstå: Läsförståelse av vad och varför?

Parkinson, B., & Reid-Thomas, H. (2000). Teaching literature in a second language. Edinburg University Press

Vetenskapsrådet. (2017). Good research practice. Swedish Research Council. Retrieved from: https://www.vr.se/english/analysis/reports/our-reports/2017-08-31-good-research-practice.html

Wankah Foncha, J. (2014). Reading as a method of language learning among L2/first additional language learners: A case of English in one high school in Alice. Mediterranean Journal of School Sciences, 5(27), 675 – 682. Doi:

Appendix 1 – Questionnaire

1 2 3 4 Strongly Slightly Slightly Strongly

Disagree Disagree Agree Agree

English as a subject

1. Learning English is great. 1 2 3 4 2. I hate English as a subject. 1 2 3 4 3. I really enjoy learning English. 1 2 3 4

4. I would rather spend my time on subjects other than English. 1 2 3 4

5. English is a very important part of upper secondary school. 1 2 3 4

6. I think reading is an important part of learning a language. 1 2 3 4

7. I like to read books and short stories in English during class. 1 2 3 4

8. I think we should read more books & short stories during English class. 1 2 3 4

9. I think we read too many books & short stories during English class. 1 2 3 4

English during my free time

10. I like to read books and short stories in English during my free time. 1 2 3 4