ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

Linguistics

and

Education

jo u r n al ho m e p ag e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / l i n g e d

Young

people’s

languaging

and

social

positioning.

Chaining

in

“bilingual”

educational

settings

in

Sweden

!

Annaliina

Gynne

a,∗,

Sangeeta

Bagga-Gupta

baSchoolofEducation,CultureandCommunication,MälardalenUniversity,Box883,SE-72123Västerås,Sweden bSchoolofHumanities,EducationandSocialSciences,ÖrebroUniversity,SE-70182Örebro,Sweden

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Available online 6 August 2013Keywords: Languaging Classroominteraction Schooldiary Sweden-Finnishschool Learning Socialpositioning

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Thestudypresentedinthispaperexamineslanguagingina“bilingual”schoolsetting.The overallaimhereistoexploreyoungpeople’sdoingofmultilingualismaswellassocial posi-tioninginandthroughtheeverydaysocialpracticeswhereliteracyissalient.Anchoredin perspectivesthathighlightthesocialconstructionofreality,andlocatedinthegeopolitical spaceofSweden,thisstudyinvestigatesaneducationalsettingwhereSwedishandFinnish areusedastheprimarylanguagesofinstructionbutwhereotherlinguisticvarietiesare present.Inthepaper,theanalyticallyrelevantconceptofchainingisempiricallyillustrated throughtheanalysisofethnographicallycreateddata.Thesedataincludevideorecordings ofclassroominteractionandmaterialsframedwithintheschooldiaryliteracypractice.The chainedflowofvariousoral,writtenandmultimodalvarietiesinhumanmeaning-making ispresentedasananalyticalfinding.

© 2013 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

InNorthernlatemodernsocieties,schoolarenasofferchildrenandyoungpeoplearangeofopportunitiesforboth conven-tionalandcreativeusageofcommunicativeresourcesrelatedtolanguaging(includingliteracy)andlearning.Participation indiverseactivitiesandpracticeswithinformaleducation,whichisinitselfanarenafornegotiatinganddisplayingsocial positions(inotherwordsidentitypositioning)isanimportantalbeitsometimesimplicitby-productoftheinstitutionally framedgoaloflearning.Forminoritystudentsattendingprogramsthataimtopromotebothmajorityandminoritylanguage varietiesinlinguisticallydiversecontexts,thisisevenmorethecase(seee.g.Bagga-Gupta,2013;Leung,2005).Focusing on(i)socialinteractionsinsideandoutsideschoolenvironmentsand(ii)practicesanddiscoursesinsocalledmultilingual educationalsettingsbothallowsforastudyofdimensionsoflanguageuseineverydaylifeinschools,butfurthermorefor researchersinterestedinmultilingualismandliteraciestoexaminelanguagingincludingliteracyusageinwhatissometimes calledidentitywork.

Broadly,thestudypresentedheretakesthefollowingperspectivesonlearningandcommunication,includingliteracy,as pointsofdeparture.First,asocio-constructional/socioculturalperspective,basedonVygotskianthinking,thatfocuseshuman beings’communicationandlearningintermsofagencyandactiveparticipationinsocialpracticesandactivities(Säljö,2000, 2005;Wertsch,1985),andsecond,approachestoliteracy,representedinthefieldofmultilingualliteracies(Bagga-Gupta, 1995,2002,2012a;Martin-Jones,2009;Martin-Jones&Jones,2000).Thelattercanbeexemplifiedthroughtheorientations

! Thisisanopen-accessarticledistributedunderthetermsoftheCreativeCommonsAttribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlikeLicense,whichpermits non-commercialuse,distribution,andreproductioninanymedium,providedtheoriginalauthorandsourcearecredited.

∗ Correspondingauthor.Tel.:+4621101693.

E-mailaddresses:annaliina.gynne@mdh.se,annaliinag@gmail.com(A.Gynne),sangeeta.bagga-gupta@oru.se(S.Bagga-Gupta). 0898-5898/$–seefrontmatter © 2013 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

labeledLiteracyStudiesorNewLiteracyStudies(NLS,e.g.Barton,1994;Heath,1983;Street,1984).Inlaterworkswithin NLS,Gee(2008)discussestherelationshipsbetweendiscoursesandliteracies,claimingthatbothofthesecompriseof group-specificrepresentations(sociallanguages),whichinturnshapeindividuals’identificationprocesses.Moreover,intermsof socialpositioning,acentralassumptionwithinthesocio-constructionalperspectiveisthatidentificationprocessesareseen intermsofajointsocialaccomplishment(Antaki&Widdicombe,1998;Bagga-Gupta,2012a,2013)ratherthaninsidethe headdevelopmentandpeople’sindividualcharacteristics.

Asmallbutgrowingnumberofstudieshaveillustratedtheroleofschoolsasmediatorsandreproducersofthecommon underlyingideasandvaluesofasociety(suchasmonolingualism),butalsothediscrepancybetweenschoolnormsand multilingualstudents’socialpractices(cf.Bagga-Gupta,2002,2004b,2012a,b; ˇCekaité&Evaldsson,2008;Cromdal,2000; Evaldsson,2003).However,despitethegrowingbodyofresearchthathighlightsthepositiveeffectsofbilingualeducation intermsofdevelopingbilingualskillsandkeepinglanguagevarietiesalivebothattheindividualandsocietallevels(seee.g. Cummins,2001;Gafaranga,2007;Garcia,2009;Grosjean,2008;Hornberger,2003,2004;Thomas&Collier,1997;Tuomela, 2001),therecontinuestoexistapaucityofknowledgethatisempiricallygroundedasfarasissuesrelatedtolanguage and literacydevelopmentor learningamongbi-and multilingualyoungpeopleinglobal,Europeanand, inparticular, Swedishsettings.ThiswasoneofthecentralconcernsforuswhentheresearchprojectDIMuL,1 DoingIdentityinand throughMultilingualLiteracypractices,wasinitiatedin2010.ProjectDIMuLisinterestedinmappingthekindsoflanguaging, includingliteracypractices,youngpeopleareengagedinbothinandoutsidewhatislabeledasbilingualschoolsettings,as wellasidentifyingwhatkindsofsocialpositionstheyhighlightandorienttowardinthecourseoftheireverydaylivesinside andoutsideofschoolsettings.Furthermore,theprojectcontributestothe(intheSwedishcontext)ratherlimitedbodyof researchthatdealswiththeso-called“forgotten”middleschoolyears(ages9–12)aswellasprovidesinsightsconcerninga large,yetsparselydocumentedminoritygroupinSweden(i.e.theSwedenFinns).Thelocalframeworkwithregardtothe projectconsistsofagroupofpreadolescentsattendingaschool,situatedinSweden,thathasanofficialbilingual/bicultural profile.

1.1. Aims,researchquestionsandfocusofpresentstudy

Theoverallaimofthepresentstudycanbeformulatedintermsofexploringhowtheparticipantsusecommunicative, includingliteracy,resourcesineverydaysocial practicesandthewaysinwhich theseinterconnectedpracticesinvoke linguisticand (cultural)social positions.Thespecificinterrelatedissuesattendedtointhestudythatisreportedhere include:

-Whattypesofcommunicativeresourcesdoyoungpeopleemployindifferentschoolpracticesinasettingthatisformally labeledbilingualeducation?

-How,andinwhatways,areaspectsofcommunicativerepertoires(suchasoracy,literacyandothersemioticresources) interrelatedinthesepractices?

-Andsubsequently:Inwhatpatternedwaysdosocialpositioningsbecomesalientineverydayoralandwritteninteractions ineducationalsettingswheremorethanonelanguagevarietyisused?

Thepresentstudycontributestoasmallbutgrowingbodyofresearchthathighlightsandillustratesthedoingof mul-tilingualisminsideandoutsideschoolarenas,andfurthermoreconnectsthiswithmultilingualliteracypracticesandsocial positioning.Thus,languagingorlanguageusebroadly,includingtheuseoforal,writtenandothersemioticresourcesrelated toworkdoneinschoolsettingsarecriticallydiscussedbaseduponanalysisoftwotypesofempiricaldatainourstudy.These includethemicro-interactionallevel(baseduponvideotapedinteractionalmaterialsofnaturallyoccurringactivitiesfrom classroomsettings)andthemesolevelofinstitutionallyframedliteracypractices(baseduponschooldiariesthatstudents andteacherscreateoverthecourseofalongertimeunit,here,duringaschoolweek;ideally,thesediariesaresenthome totheparentsonaweeklybasis).2Bringingtogetheraspectsofyoungpeoples’multilingualism,includingmultiliteracies, ourfollow-upaimistocontributefromanempiricalanalyticalpositiontochallengingthemonolingualbiasthatcurrently dominatesunderstandingsofpublicaswellasacademicdiscourses.3

Inthepresentstudylanguaging–thedynamicandsocialuseofdifferentlinguisticfeaturesforcreatingandnegotiating meanings(forfurtherelaborationsoflanguaging,seee.g.Blommaert&Rampton,2011;Garcia,2009;Jørgensen,2008;Linell, 2009)–isseenasacoreconceptforunderstandinghowhumanbeingsco-constructtheirsocialrealitiesandparticipate inmeaning-making.Asaconsequence,expressionsofsocialpositioningsandidentitiesarealsoseenasoneofthemajor

1DIMuLisapartoftheSwedishNationalResearchSchoolLIMCUL,YoungPeoples’Literacies,MultilingualismandCulturalPracticesinEveryday

Soci-ety.Formoreinformationabouttheresearchschool,seehttp://www.oru.se/English/Education/Research-education/Research-schools/Research-schools/ LIMCUL—Literacies-Multilingualism-and-Cultural-Practices-in-Present-Day-Society/.

2WhileAuthor1(inpreparation)attendstocommunicationissues,includingliteracies,atthreelevelsorscales:micro-interactional,mesoactivity

levels(forinstancepracticesinschoolsandhomes)andmacrosocietaldiscourselevelswithinprojectDIMuL,bothauthorsworkatallthreescales indifferentethnographicallyorientedprojectswithintheongoingworkattheCCDresearchenvironment,seehttp://www.oru.se/English/Research/ Research-Environments/Research-environment/HS/Culture-Communication-and-Diversity-CCDKKOM/.

functionsoflanguaging.Identitiesandsocialpositioningsthen,areunderstoodasinteractionallyanddiscursivelyconstructed, ever-changingplurals,ratherthansingular“possessions”thatindividualsown(e.g.Gee,2000;Hall,1996;seealsoPavlenko &Blackledge,2004).Furthermore,thereproductionandtransformationoftheseisconsideredadynamicprocessoccurring throughtheinterconnectednessofinteractionandcommunicativepractices.Inconcertwiththisandinconjuncturewith framingswithinLiteracyStudiesorNLS,ourfocusis,inadditiontolanguagingandsocialpositioning,onliteracypracticesand literacyevents,orthesocialexperiencessurroundingeventsandactivitieswherethewrittenmodalityisorientedtowardor playsarole(seee.g.Gee,2008;Hornberger,2003).

1.2. Organizationofthepaper

Therestofthepaperisorganizedasfollows:Section2presentssomebackgroundinformationconcerningthelinguistic andculturallandscapeofthefieldthatisfocusedandabriefoverviewofpreviousliteraturerelevantforthepresentstudy. Inthesectionthatfollows(Section3),methodologicalperspectivesandtheresearchdesignofthestudyarespelledout.The centralsectionofthearticle,Section4,presentsanalyticalexplorationsoftheinteractionalandtextualdatasourcesthat havebeendrawnupon.CentralfindingsandconcludingreflectionsarepresentedinSection5.

2. Framingthestudy

AgainstthebackdropofthecontemporarylinguisticandeducationallandscapeinSweden,theresearchpresentedhere focusesontheeverydaylivesofyoungpeoplewhoaremembersofwhatisdescribedasabilingual/bicultural Swedish-FinnishminorityschoolincentralSweden.SwedenFinnscomprisethelargestlinguisticminorityinSweden,4consisting ofapproximately200–250000speakers(Lainio,2001),aswellasoneofthefiveofficiallyrecognizednationalminorities (LanguageCouncilofSweden,2011).Historicallyandespeciallysincethe1950s,theSwedenFinnshaveseenasignificant processoflanguageshiftfromFinnishtoSwedishduetosocietal,attitudinalandpracticalreasons(Kangassalo,2003,2007; Lainio,2001;LanguageCouncilofSweden,2011).Ithasalsobeenarguedthattheeducationalsystemhasplayedasignificant roleinthisprocess.Furthermore,duetomuch-debatedchangesinnationaleducationalpolicysincetheearly1990swhen thecompulsoryschoolsystemwasdecentralized,theresponsibilityforofferingbilingualprogramsinSweden(forlanguage pairslikeEnglish-SwedishandFinnish-Swedish)hasatapracticallevelbecometheresponsibilityofsocalledindependent schools5(Huss&Lindgren,2005;Kangassalo,2003,2007;Lainio,2005).ThenumberofindependentschoolsinSwedenhas morethandoubledduringthelast15yearsandwas741duringtheacademicyear2010/11,whenthedatacreationadhering tothepresentstudywasconducted.Inall,13%ofchildrenattendingschoolsinSwedenwerestudentsinindependent schools,asopposedto87%inmunicipalschools(TheSwedishNationalAgencyofEducation,2011).Ofthese,approximately 1000studentsattendwhatisformallylabeledasthebilingualSwedish-Finnishprogramsofferedbysevenindependent Swedish-Finnishschools.TheDIMuLprojectschoolisoneofthese.

Asindicatedearlier,theresearchwepresentherefocusesmundaneaspectsofbothmicro-interactionaldimensionsof schoolpracticesandzoomsinonthemeso-realmsofnaturallyoccurringlanguagingincludingliteracypracticesinschools, suchastheDIMuLprojectschool.Previousresearchfindingsthatbuilduponthesetypesofempiricalmaterialfrombilingual settingsareuncommonandwhenavailableareprimarilybaseduponinteractionaldatathatiseithersubjectedto micro-levelCA,conversationalanalysisoradescriptivepresentation.Somecentralfindingsfromthefewstudiesthathavebeen identifiedandarerelevantforthepresentstudyaresummarizedbelow.Foramoresystematicreviewofpreviousresearch withrelevancefortheongoingworkinDIMuLproject,seeAuthor1(inpreparation).

InbothNordicandinternationalcontexts,scholarsinterestedinyoungpeople’slanguageusageandidentitiesin multi-lingualclassroomshaveprovidedthefieldwithasubstantialbodyofresearchoninteractionaldata.Tworecentstudiesfrom socalledmultilingualschoolsettingsdealingwithadolescents’socialinteractionandidentificationprocessesaswellas language,interactionandlearningincontemporarysuburbanSwedenhavebeenpresentedbyGröning(2006)andHaglund (2005).Theirresearchillustratesmultilingualyoungpeople’sparticipationincreatinginstitutionalorderaswellas socio-culturalchange.Forinstance,Gröning’scentralfindingisthatstudentsparticipatinginsmallgroupactivitiesengagein languageproblemsandsupporteachotherinaccomplishingadequatesolutionstothetasksathand.Severalother stud-ieshavealsohighlightedtheconstitutivepowerofpeergroupsforgradualmasteryofbothexplicitlinguisticcapabilities andgeneral(pragmatic)interactionalroutines(seeforinstanceCorsaro,1985;Corsaro&Eder,1990;Cromdal,2000;Heath, 1983).AmongearlystudiesoflanguagesocializationandlanguagelearningSchieffelinandOchs’s(1986)andWatson-Gegeo andBogg’s(1977)contributionscanbementioned.Inmorerecentstudies,peerinteractioninsideandoutsideschoolarenas arebothempiricallyandtheoreticallyinvestigatedbye.g.Bagga-Gupta(1999,2002),Evaldsson(2005),Knobel(1999)and Kyratzis(2004).Kyratzis(2004),forinstance,focusesonanumberofpreviousstudieswithinsociology,sociolinguistics andlinguisticanthropologyandexaminespeerinteractionandhowpeergroupsandculturesarebothco-constructed,as

4OfSweden’spopulationof9.4million,thenumberofpeopleofFinnishdescentoverthreegenerationsisroughly675000(SCB2009).

5Whilethelargemajorityofschoolsaregovernedbylocalmunicipalities,socalledindependentschoolsinSwedenarerunbyotherprincipalorganizers

andowners.Theyare,however,publiclyfinancedthroughavouchersystem.Theseschoolsofferabroadrangeofeducationalchoicesintermsofprofiles, aims,andpedagogicmethods.

wellastheroletheyplayforlanguagelearningandtheprocessoftalkingidentitiesintobeing(Bagga-Gupta,2012a).Ina similarlineofresearch,ˇCekaité(2006)portraysthemultilingualclassroomintermsofa“socialsiteforlanguagelearning” (2006,p.11)andhighlightslearners’communicativepracticesthroughtheanalysisofvideorecordingsthatconstitutes hermainmethodofdatacreation.Suchcollaborativecommunicativepracticesthatcreatecomprehensionandfacilitate communicationinpeergroupsareinvestigatedalsobyOlmedo(2003)inaSpanish-Englishschoolsetting.Olmedosuggests thatprovidingscaffoldingthrough,forinstance,paraphrasingorspontaneouslytakingtheroleofatranslatorcantogether withparalinguisticcuesbeunderstoodintermsofsignsofmetacommunicativeawarenessamongchildren.Thediscursive constructionoflocallyemerginglearneridentitiesinclassroominteractionisillustratedbyanumberofmorerecentstudies (e.g.Bagga-Gupta,2003,2010,2012a; ˇCekaité,2006; ˇCekaité&Evaldsson,2008).Hereacommonpointofdepartureisthe intrinsicinterestinsocialinteractioninmultilingualclassroomsettingsandafocusuponlanguageusageandidentityissues. BarringBagga-Gupta’sresearch,noneofthem,however,explicitlyattendstoliteracyasanelementofmultilingual interac-tionandsocialpositioning.Nordothesestudiesexplicitlydiscuss“languaging”asdoing,thoughmanyofthemeffectively illustratetheuseoflanguagefromaperspectivethathighlightsthedynamicandsocialaspectsoflanguage,aswellassocial positioningaccomplishedthroughlinguisticmeans.

Focusingaspecificformofliteracyfromthelanguagingpointofview,systematicanalysisofschooldiaries(orlogbooks) areuncommonandfurthermoresuchliteraturerarelyfocusesonissuesoflanguagevarietiesandsocialpositionings. Col-lectingparticipantdiarieswithintheframeworkfordatacreationhasbeenemployedwithinqualitativeresearch,especially instudiesthattakehermeneuticalandphenomenologicalpointsofdeparture.However,withintheseperspectivesdiarydata isoftenelicitedbytheresearcher,implyingthatdataisconstructedtoservespecificpurposesrelatedtotheaimsofthat research.Workingwith“authentic”diarydata(i.e.diariesorlogbookscreatedwithinpracticesuponwhichtheresearcher haslittleornoinfluence)isthusalesscommonresearchdesignperspective.SomerecentexceptionsintheNordiccontexts includeGranath’s(2008)workondevelopmentaltalksandlogbooksfromthreeSwedishschools;BergqvistandSäljö’s (2004)sociohistoricaldiscussionsoneducationalpractices;and,Dysthe’s(1996)andHalse’s(1993)workonlogbook writ-ing.LogbookwritingisreportedtobeacommonschoolpracticeinSwedenandNorwaythathasbecomepopularduringthe lastfewdecades.Theresearchthatexistssuggeststhatideasof“process-orientedwriting”,fromforinstanceTheBayArea WritingProjectatBerkeleyUniversity,areaccountedforasinspirationalsourcesforthespreadofthisschoolpracticein Scandinaviancontexts(Granath,2008).AccordingtoGranath’staxonomy,therearetwocommonformsoflogbookwriting inSwedishschools.Whilethefirstofthesefocusesonreflectionsonthecontentofdifferentsubjectsandlessons,theother isconcernedwithplanningandevaluatingtheweekthathaspassed.Furthermore,BergqvistandSäljö(2004)highlightthat whilethemainpurposesof“planningbooks”intheirstudyhavetodowithorganizingthecomingweekanddocumentation ofpastevents,thesecomprisealsoaworktaskintheirownright.Theauthorstherebydiscuss“planning”intermsofa discursivepractice.Takingasomewhatdifferentangle,“recurring”three-foldfunctionsoflogbooksarereportedina Nor-wegianschoolstudy(Dysthe,1996)intermsof:“askingquestions,writingpersonalreflections,butalsoforidentification, linkingandgeneralizing”(1996,p.102).OneofthemainanalyticalfindingsinthesestudiesisalsoprominentinHalse’s (1993)researchandrelatestothedialogicalnatureoflogbooks.BasedonaBakhtiniananalysis,Halsesuggeststhattheir centralfunctionistheaffordancestheycreateintermsof“doubledialogicism”(1993,p.10).Asatoolforself-exploration, reflectionandconfession,thelogbookintertwinesthe“voices”frominsideandoutsidethestudent.Acommonthemein thisliteraturethusincludesthedialogicalandmulti-facetednatureoflogbookordiarywriting.Forpresentpurposesitis importanttohighlightthatthepreviousliteraturethatexplicitlyfocusesonlogbooksinschoolsettingsdoesnot,however, dealwithactivitiesinwhichthelogbookwritingisembeddedexplicitlyfromliteracypracticespointsofdeparture.

Twocommonlyrecognizedconceptsthathighlighttheinterconnectedrelationshipsinandbetweendiscoursesand texts–orlanguagingincludingliteracies–areintertextuality(Bakhtin,1981,1986;Kristeva,1986)andinterdiscursivity (Fairclough,1992).Accordingtothislineofthought,therearemultiplevoicespresentintheproductionandtransformation ofdiscoursesandtexts.Furthermore,senseandmeaningareseenasdialogicallylinkedtopriorandforthcomingstretchesof communication,quitesimilartoourearlierdiscussionontheworkofDysthe(1996)andHalse(1993).Intertextualitythus referstotherelationshipbetweenpracticesandtexts(inabroadsense).Fromanempiricalpointofview,thesetheoretical ideasarerelatedtoaspecificthemethathasbeenidentified intherecentresearchonsocalledbilingual multimodal communicationinthemultidisciplinaryfieldofDeafStudieswhereethnographershavestudiedsocialinteractionindiverse settingswheredeafandhearingstudents,teachersandparentsaremembers(seeBagga-Gupta,2000,2003,2004a;Erting, 1999;Hansen,2005;Padden,1996).Forpresentpurposeswewillcallattentiontoaninteractionalpatternfromthisbody ofliteraturethatisinterchangeablytermed“linking”and“chaining”.Chaining,accordingtoHumphriesandMacDougall (2000,p.90),isa“techniqueforconnectingtextssuchasasign,aprintedorawrittenword,orafingerspelledword...this techniqueseemstobeaprocessforemphasizing,highlighting,objectifyingandgenerallycallingattentiontoequivalencies betweenlanguages”.6Morerecently,chainingisemergingintermsofarobustempiricallygroundedconceptintheanalysis ofmonolingualandmultilingualhearingoralandwrittenlanguageuseaswell(seee.g.Bagga-Gupta,2009,2011,2012a; Hansen,Bagga-Gupta,&Vonen,2011;howeverseealsoBagga-Gupta,1995).Ananalyticallygroundedconceptofchaining

6“Chaining”asananalyticaltermisthusapplicableformappingcomplexdiscursive-technologicalpracticesindifferentsocalledmultilingualsettings.

(incontrastto“switchingbetweenseparatecodes”),throwslightonthemeaning-makingpotentialsinvarioussettings wherehumanbeingsusearangeofcommunicativeresourcesinboth“oral”and“literacy”contexts.

IntheNordicaswellasNorthAmericanliterature,chaininginmultilingual-multimodalsettingshasbeenobservedas occurringinatleastthreedifferentlevelsconsideredaslocalchaining,eventoractivitychaining,andsimultaneous/synchronized chaining(seee.g.Bagga-Gupta,2000,2002,2004a;Hansen,2005).Whatthispreviousliteratureonthemicro-interactional languaginginmultilingualcontextshighlightsistheinter-linkednatureoflanguage-varieties-in-useineverydaylifewhere thewritten-oralorwritten-oral-signedmodalitiesareintricatelyconnectedtooneanother.Forthepurposesofthepresent study,chainingisconceptualizedintermsofemicwaysinwhichhumanbeingsconnectoral,writtenandothersemiotic resourcesincludingdifferentmodalitiesinthecourseofnaturallyoccurringdailylife.Itischaininginandbetweensuch resourcesthatcreatesacommunicativeflow.

3. Thetraditionofethnographicenquiryandmethods

TheDIMuLprojectandthestudybeingreportedherebuilduponthetheoretical-methodologicalperspectiveof ethnog-raphy(Aspers,2007;Heath,Street,&Mills,2008;Wolcott,2008).Inlinewiththeworkofothercriticalethnographers(for instanceWhyte,1999),wecontendthatethnographicfieldworkisashorthandtermforthecreation(ratherthanthe “col-lection”ofpre-existingdata)ofdatathroughavarietyofmethods.Inotherwordsourdataismutuallycrafted,producedand constructedinthefieldandwiththecommunitystudied,i.e.themembersofwhatwecall“Class6C”inaSwedish-Finnish schoolprogramduringthebeginningoftheseconddecadeofthe21stcentury.

3.1. Datacreation

TheprojectschoolwhereethnographicfieldworkwasconductedbyAuthor1,7characterizesitselfas“offeringeducation fromprimarytosecondary levelswithhigheducationalstandardsand learningobjectiveswiththeaimofdeveloping thestudents’bilingualaswellasbiculturalSwedish-Finnishskills”(originalinSwedish,availableintheschool’spublicity materials(2010)).Thebilingualprogramintheschoolcanbecharacterizedaspartlycorrespondingtotheso-called Two-WayorDualLanguageImmersionprograms(seee.g.Thomas&Collier,1997)andpartlytowhatismoregenerallycalled asMaintenanceprograms(seee.g.Baker&Jones,1998).SimilartoallindependentschoolsinSweden,theprojectschool followstheSwedishnationalcurriculumandsyllabi,whichmeans,amongotherthings,thatEnglishasasubjectisincluded inthecurriculum.Specificfortheprojectschoolis,however,thatitcaterstotheeducationalneedsofoneofSweden’slargest linguisticminorities,SwedenFinns,asitprovidesbilingualinstructionacrossthecurriculuminbothSwedishandFinnish. ApartfromservingthehistoricalSwedenFinnishlinguisticminority,theschoolalsoprovideseducationforchildrenofe.g. FinnishexpatriatesemployedononeortwoyearworkingcontractsinSweden.Thenumberofstudentsintheschoolis approximately370withapproximately50staff.

The present studyfocuses data generated in Class6C where a handful of adults (subjectteachers, class teachers, substitutes,etc.)and18studentsbetween12and13yearsofage,tengirlsandeightboysaremembers.Asiscommon forthelargemajorityofstudentsattendingtheschool,allthepreadolescentsinClass6ChaveatleastoneparentofFinnish originandthuscomefrompredominantlymultilingual(Swedish-Finnish,butalsootherlanguagevarietycombinationssuch asGerman-Swedish-Finnish,Spanish-Swedish-Finnish)homesettings.Furthermore,allstudentshadarangeofexperiences inusingwhatcanbecharacterizedasinformationandcommunicationstechnologies(ICT)suchascomputersandmobile phones.Thesamplingofthisgroupofparticipantswasbasedonourinterestinmultilingualeducationalsettingsingeneral andtheSwedenFinnishminoritygroupinparticular,aswellastheaimofinvestigatingidentifications,languageincluding literacypracticesofpreadolescentsinacertainagecohort(“theforgottenmiddleschoolyears”).Theprojectschool,being oneofonlysevenformallydesignatedbilingualSwedish-FinnishschoolsinSweden,togetherwithClass6Cinwhichall membersagreedtoparticipatethereforeprovidedanexcellentsiteofinvestigationforprojectDIMuLandthepresentstudy. ThedataintheDIMuLprojectemergedduringaperiodof20monthsoftacticallyandsystematicallyplanneddimensions offieldwork.Asinmuchethnographicresearch,therelationshipbetweentheresearcherandtheresearchedevolvedand fluctuated,whilegraduallydeepeningoverthecourseofthistime.Amongotherthings,thedatacreatedduringthefieldwork includedvideotapingpracticesinsideclassroomsoverentiredaysandcollectingtextsusedandcreatedintheclassroom practices.Also,asinanyethnographicenterprise,theprojectincludeddatacreationthatoccurredinalessdeliberatemanner wheregettinginvolved,overhearingconversations,casualchattingandparticipatinginactivitiesareacknowledged.In alltheseprocesses,thesocalledmultilingual(Finnish-Swedish-English)resourcesofAuthor1weresignificantfroman analyticalpointofdeparture.Inotherwords,theprojectdataiswide-rangingandassuch,otherelementsoftheprojectdata willbeaccountedforinforthcomingstudies.8Thetwomainmethodologicalpointsofdepartureaddressedinthispaper

7FieldworkinprojectDIMuLhasbeenconductedbyAuthor1.Author2,togetherwithanothermemberofprojectDIMuLhasconductedfieldworkina

parallelSwedenFinnishschoolwithintheframingsofanotherSwedishResearchCouncilprojectrecently.

8Moredetailedaspectsofthefieldwork,conductedbyAuthor1,inbothschoolandvirtualenvironmentsrelatedtostudyingtheeverydaylivesof

membersofClass6Caswellasissuesofsocialpositioningandlearningwillbeaccountedforinforthcomingstudies.Anoverviewanddescriptionofdata availableinDIMuLprojectisavailableinAuthor1(inpreparation)andGynneandBagga-Gupta(2011).

Table1

Datafocusedinthestudy.

Typeofdata SpecificdatainprojectDIMuL (ofrelevancetothisstudy)

Sampledatausedinpresentstudy Levelofanalysis Videorecordingsofclassroomactivities 25h 2sequences Micro-interactional Schooldiaries 98diaries 2diaries Meso(localpractice)

arevideotapingbyusingaSonyHandycamHDR-SR11videocameraandparticipantobservationsintheschoolsetting,as

wellasdocumentationofparticularkindsoftextsusedandcreatedbymembersofClass6C.Thus,twocoredatasetsare

focusedinthepresentstudy:approximately25hofvideorecordingsand98logbooksorschooldiaries(seeTable1).In

videotaping,thefocuswasonlearningpracticeswheretheinterplayofdifferentformsofsocalledmultilingualliteracies includingoraciesinschoolworkwasdiscernible,whilefocusinguponschooldiariesgaveusanopportunityforunveilinga literacypracticethatframestheweeklyroutinesofClass6C.

3.2. Dataanalysis

ThefirstsetofdataincludesvideorecordingsofsocialinteractionsamongthestudentsandadultsinClass6Catthe Swedish-Finnishschool.Datasamplingandcodingfromthevastmaterialof25hofrecordingsfocuseduponsequences thatdisplaytheparticipants’useofmultilingualresourcesaswellaswhatwasidentifiedasliteracypracticesinarangeof situations.TheentirevideocorpushasbeensubjectedtopreliminaryanalysisbyusinganadaptedversionofConversational Analysis(CA,seee.g.Sacks,1992a,b;Jefferson,2004)thatisinspiredby(i)ˇCekaitéandEvaldsson(2008)inconjuncture with(ii)twospecificextensionsfromourongoingworkinBagga-GuptaandSt-John(2010,forthcoming)andHolmström andBagga-Gupta(submittedforpublication).Inbothoftheabove,aswellasinthepresentwork,inadditiontoworking withdetailedanalysesoftheinteraction,theanalystshavedrawnuponresourcessuchastheethnographicknowledgein makingsenseoftheorientationsandsocialpositioningsoftheparticipants.Themicro-interactionalanalysishaspaidspecific attentiontothesituated anddistributednatureofmultilingual(differentlanguagevarieties)andmultimodal (written-oral-etc.)dailyclassroomcommunication,includingtheinteractionthatfocusesuponthethemes,categoriesandsocial positioningsbroughttolifebyparticipantsintheeverydaylifethatconstitutesClass6C.Forthepresentstudy,twosequences, illustratingsalientfeatures thathaveemergedintheanalysisofmultilingualliteracypractices,havebeenselectedfor presentationanddiscussion.Thesesequencesrepresentacommonlyoccurringphenomenonintheclassroominteractional datathatentailstheusageofdifferentlinguisticincludingtextualresources.They,inaddition,pointtowarddimensionsof socialpositioning.Whiletheparticularsequencesanalyzedhereshowfeaturesspecificallyrelatingtotheactivityathand, correspondingphenomenawheredifferentkindsoforalandwrittenlinguisticelementsinterconnectwereobservedwhile conductingascreeningofourentirevideocorpus.

Thesecondsetofdataconsistsofmaterialspertaining totheschooldiary literacypractice,alocalliteracypractice occurringinClass6C.Aschooldiaryinthestudyisareportthateachstudentauthorsattheend ofaschoolweek.At leastthreediariesfromeachofthe18studentsinClass6Cwereaddedtotheprojectdataduringthefalltermof2010, resultinginatotalof98diariesinthedata(seeTable1).Intermsofdataanalysisprocesses,thisdatasethasbeencodedas follows:Byadaptingadiscourseanalytical(DA)approachwherethefocushasbeenonwhate.g.Fairclough(1992)describes astheconditionsofthediscoursepracticeorthesocialpracticesoftheproductionandconsumptionassociatedwiththe textsanddiscourses,wehavezoomedintothe(i)purposesandthenatureofthediarypracticeaswellasdiariesinterms offormaltextsinschoolsettings,(ii)languageusageinthediariesbyyoungpeopleandadults,and(iii)thecontentof thediaryentriesaswellasothermaterialspertainingtotheschooldiarypractice.ThelattertwoarerelatedtoFairclough’s formulationoninterdiscursivityandintertextualchains:“theobjective(...)istospecifythedistributionofatypeofdiscourse samplebydescribingtheintertextualchainsitentersinto,thatis,theseriesoftexttypesitistransformedintooroutof” (Fairclough,1992:232).Priortoapplyingthediscourseanalysisonspecificdatasets,thediarytextswerealsosubjectedto aquantitativeanalysisthatrevealedthatthestudents’contributionsinthevastmajority(81%)ofnearlyahundreddiary entrieswerewritteninmostlyFinnish,whereas19%oftheentrieswerewrittenprimarilyinSwedish.Languagevarieties otherthanSwedishandFinnishortouseacommonconceptfromtheliterature,“code-switching”9inindividualdiaries appearedmoreuncommonly.Itappearedin15%ofthetextsandprimarilyassinglewords.Theteacher’scontributionof textspertainingtothediarypracticewashoweveralwaysinbothFinnishandSwedish.Multimodalityintermsofthe co-presenceofalphabeticaltext,numbersandothersemioticresourceslikedrawings,useofdifferentcolorsandsymbols,on theotherhand,wasamorecommonphenomenon,visiblein26%ofthestudents’texts(seeSection4.1below).Twospecific diariesthatrepresentandreflectbothuniqueandcommonlyreoccurringelementsoftheschooldiarypracticehavebeen chosenfromthecorpusinordertoillustratethediscourseanalysisandfindings.

Thecombinedanalysisofthesedataprovidesinsightsonhowyoungpeople’swrittenandorallanguageresourcesthat includearangeoflinguisticvarieties,andothersemioticdevices,connectandintertwinewithineducationalsettings.Inour analysis,thenamesofallparticipantsarepseudonyms.

4. Languagingacrosstimeandspace–chainingandotherlinks

InSection4.1,twomicro-interactionalexamplesfromalessoninthelanguage-focusedsubject“Swedish”areprovided. Theseexamplesillustratetheintricatewaysinwhichmembers’languaginginvolvesanumberofchainedlinguisticand multimodalresourcesinheteroglossicclassroominteraction.Section4.2,then,illustratesthelayeredchaining(explained inthatsection)thatoccursintheschooldiaryliteracypractice.Thisisexemplifiedbyananalysisofthepracticeaswellas twodiarycasesthathighlightcommonroutinewaysinwhichtheform,contentandcontextofthischainedcommunicative practicehasemergedinthedata.

4.1. Multilingualchainedclassroompracticesatthemicro-interactionallevel

Inthissection,weanalyticallydiscussexamplesofclassroominteractiontoillustratesomecommonlyoccurringeventsin thestudents’livesinthedata.Twoempiricalexamplesfromalessoninthelanguage-focusedsubject“Swedish”arediscussed. Theexamplesrepresentinteractionsthatexplicatearangeofphenomenathatemergeinmultilingualclassroominteraction. Theexcerptsillustratethephenomenaofbothinitiation-response-evaluation/follow-up(IRE/IRF,cf.Cazden,2001;Mehan, 1979;Sinclair&Coulthard,1975)andpeerscaffolding(cf.Cazden,2001).Inaddition,andsignificantly,ourmicro-level analysisillustrateshowtwoormorelinguisticvarieties,aswellasdifferentliteracyresourcesarecloselyinterconnectedor chainedinthemeaning-makingprocesses.Excerpts101and2illustratecomplexhybriditywheremembersofClass6Cuse multilingualliteraciesinordertoco-constructmeaninginthecourseoftheflowofeverydaylifeintheclassroom.

Sixstudentsandateacherparticipateindiscussionsthatarefocuseduponinthetwoempiricalexamplesbelow.The focalpersoninthefirstsequence(seeExcerpt1)isHugo,a12-yearoldboywhoisanew-comerbothintheclassandin SwedenfromFinlandandonecanthusassumethathehaslimitedexperiencesofusinglanguagesotherthanFinnish.His situationdifferssomewhatfromJonas’s,another12-yearoldboyborninFinland,who,despiteofhavinglimitedexperiences ofusingSwedish,seemedtohaveahighercommandofEnglishthanmanyofhisclassmates,possiblyduetothefactthat hespentseveralyearsinanotherEuropeancountry(seeExcerpt2).ThefocalpersonofExcerpt2,Janne,wasalsobornin FinlandandhadbeenlivinginSwedenandattendingtheSwedish-Finnishschoolforlessthantwoyearsatthetimeofthe study.ThesethreestudentsdifferedfromtheotherstudentparticipantsintheExcerpts(aswellasotherstudentsinClass 6C):Felicia(Excerpt1),Hans(Excerpt1and2)andFilippa(Excerpt2),intermsoftheirlinguisticheritage,giventhatthe majorityofstudentsinClass6CwerebornandhadgrownupinSweden.Itcanthereforebeassumedthatthelatterhave richexperiencesofusingbothSwedishandFinnish(inadditiontootherlinguisticvarieties).

OuroverarchingethnographicanalyseshighlightthatnewlyarrivedstudentswhoaremembersofSwedishlanguage classesareusuallyprovidedseparateinstructionsforlearningSwedishandareseldomengagedinfull-classactivitiessuch astheonesrepresentedbyExcerpts1and2.TheExcerptsshow,however,acommoninteractionalpatternwhereinbothoral Swedish,Finnishand/orEnglisharelocallychainedorlinkedwithwrittengraphicresources,suchaswordsthataredisplayed onthewhiteboardortextsinstudents’books.Suchchainingoccurswhenthe(male)teacherduringtheintroductionphase ofaSwedishlanguagelessonintegratesEnglishwrittenwordsthataredisplayedvisuallyonthewhiteboardfromprevious Englishlanguagelessoninhisinstructionalwork.Inanactthatmightseemarbitrary,hedynamicallymakesuseofaliteracy resourcecreatedbyateacherinapreviouslessontoestablishalinkagebetweendifferentsubjectcontentsaswellastemporal phasesoftheschoolday.

Byusingthewhiteboardliteracytooltheteacher(seeExcerpt1)attemptstoengagetwoboys,Hugo(seeExcerpt1)and Janne(seeExcerpt2)inthesharedclassroomdiscourse.HugoandJanneprimarilymakeuseofFinnishintheiroral com-munication.PriortothebeginningoftheinteractionrepresentedinExcerpt1,theteacherhaslookedupatthewhiteboard andbyorientingtowardthelistofwrittenwordsdisplayedthere,nowcommentsonwhatwasservedforlunchearlierthe sameday(turn35).Theteacherthenposesaquestionconcerninganotherwordonthewhiteboard(“flavor”,turn38)and subsequentlyturnstoHugo(turn42).Localchaining(i)betweendifferentlanguagevarietiesand(ii)betweentheoraltalk andthewrittenwordsdisplayedonthewhiteboard,emergesintheinteractionpriortotheteacher’scontributioninturn 42.

WhenorientingtowardHugo,theteacher’sturnindicatesanexplicitwaytoengageHugointhediscussionascompared towhathasbeenobvioushithertowhenheaddressedtheentireclass.Thismarksthebeginningofan initiation-response-evaluation/follow-upsequence.UsingSwedishandEnglishaslanguagevarietiesdeployedinoralinstruction,heemploys somemeta-languagewhenheposesthequestion“andthenI’mgoingtoask(.)thenI’mgoingtoaskHugowhatsausage isbothinFinnishandinSwedishifyourememberthat”[originalutteranceinSwedish](turns42–43).Theaudiorecording dimensionofthedatasuggeststhattheteacher’sarticulationofthewords“InFinnishandinSwedish”[originalutterancein Swedish]isslowerandmoreemphasizedthanthesurroundingoraltalk.Aspectsoflinkingoflanguagevarietiesbecomes visibleasseveralstudentsengageinthediscoursebyusingFinnishtoassistHugo(“whatisthatsausageinFinnish”[original inFinnishandEnglish],turn44).Thus,theparticipantsmakeuseofthreedifferentlinguisticregisters,acrosstwoturns. Thisdisplayoflanguagehybridityandchainingcontinuesinthefollowingturnsasanotherstudent(Janne)attemptsto helpHugobyofferingaresponse(“sausage”[originalinSwedish],turn45)totheteacher’ssecondquestion.Janne’sturn

Fig.1.Sausage-makkara-korv(47sec.SeetranscriptionnoteinAppendixA).

isfollowedbyFilippa’sprotest(turn46).Atthispointtheteachergoesontorepeatthefirsthalfofhisquestion,thistime usingbothSwedishandEnglishvarieties(turn47).HugonowdeliversthecorrectanswerintheFinnishvarietyinajovial voice(turn48).InthefirstpartofExcerpt1,theteacherinvestsconsiderableeffortinformulatinghisinitiativeaimedat Hugo.Hedoesnotexplicitlyemploytheliteracyresourcewrittenonthewhiteboard,butascanbenotedinthisstretchof socialinteraction,chainingoccursnotonlybetweenvisuallyavailablewrittenwordsandverballyarticulatedorallanguage resources,butalsobetweendifferentoralvarieties(Swedish-English-Finnish).

Bythistime,Hugohasdeliveredhalfaresponse,andtheteacher’sre-initiationleadstheinteractiontothenextphasein thisexcerpt.Theteacher’s11repetitionofHugo’sanswer(turn49)differssomewhatfromastandardFinnishpronunciation

11Themajorityofteachersattheprojectschoolareconsideredmultilingual,i.e.havingacommandofbothFinnishandSwedish(inadditiontoEnglish

and/orotherlanguagevarieties).ThelinguisticresourcesoftheteacherparticipatingintheclassroominteractionrepresentedinExcerpts1and2are, however,limitedtoSwedishandEnglish.Heself-reportstohavinglittleornocommandofFinnish.Ourempiricaldataalsocorroboratestheteacher’s limitedexperienceswithFinnish.

Fig.2. Bowl-kulho-skål(19sec.SeetranscriptionnoteinAppendixA).

andbecomesasourceofimitationandlaughterforthestudents(turns50–51,57,alsolaterin59–60).UsingEnglishhe continuestofinishthetaskathandbyaskingHugo(“andinSwedish”[originalutteranceinEnglish],turn49,“wehaditin atlunchtoday”[originalutteranceinEnglish],turn52),wherebyHugofinallydeliversthecorrectanswerinSwedish(turn 53).Thisisrewardedbyonestudentthroughanencouraging“yay”(turn55)andbyanotherthroughapplause(turn56).In additiontoshowinghowthreedifferentorallanguagevarietiesandalistofwrittenwordsinEnglishandArabicnumerals onthewhiteboard(seeFig.6)arechainedtoeachother,theexcerptshowshownewcomersintheclassroom(Hugoand Janne)aresocializedintothemultilingualsocialorderthroughbothexplicitandimplicitmeans.Inotherwords,theanalysis illustrateshowtheparticipantsorienttowardamultilingualinteractionalorderinasettingthatisformallyperceivedasa “Swedishlesson”inaschoolthatisformallylabeledbilingual.Furthermore,intheprocess,theparticipantsalsopositionboth eachotherandthemselvesindifferentkindsofsocialpositionssuchas“learnersofSwedish”,“competentinSwedish(and English)”,or“helpfulpeers”aswellasothersociallyconstructedpositions.Theseissuesarealsoillustratedintheanalysis ofanothermundanestretchofeverydayinteraction(seeExcerpt2below).

TheanalysisofExcerpt1abovehighlightstheroutinewaysinwhichmeaning-makingandsocialpositioningoccur throughthechainingofdifferentlinguisticandmultimodalelementsparalleltothesupportofpeersinmundanelocal-level interactionsinclassroomsettings.Thiscanalsobeseeninthenextexcerpt,acontinuationofExcerpt1,wheretheteacher responsibleforteachingintheSwedishlessoncontinuesusingtheEnglishwordsonthewhiteboardinordertoengage studentsinthecommonclassroominteraction.

TheinitialinteractionrepresentedinExcerpt2illustratesatypicalIRE/IRF-sequencewiththeteacheraddressingJanne withaquestionaboutthemeaningoftheword“bowl”inSwedish(turn61–62).WhileJannedoesnotacknowledgethe teacher’sinitiationverballyheattendstothequerynon-verballybyshiftinghisgazeuptowardthewhiteboardand/orthe teacher.Filippa’sensuingverbalcontributionsinturns64and66includetwochainingstoavisualwrittenresource(an Arabicnumeral)relevanttotheinteractionwhenshepointsouttwiceinquicksuccessionthenumbernexttotheword onthewhiteboardthattheteacheriseliciting(“seven”[originalinFinnish],64,“it’snumberseven”[originalinFinnish], 66).Anotherstudentsuppliesanotherhintbyreadingaloudthewordonthewhiteboard(“bowl”[originalinEnglish],turn 67),thusmakingyetanotherlinktothewrittenresourcethatisavailablevisually.Janne’sensuingturn(68)canbeseen asdirectedtoeitherFilippaorallthepreviousparticipantswhenheannouncesthathedoesnotknowwhattheoraland writtenword“bowl”meansinFinnish,EnglishorSwedish.

Atthispoint,Hans,inturn69,attemptstohelpbyrepeating/clarifyingtheteacher’soriginalquery(andbythisstagethe entiregroup’squestion)inFinnish:“whatisitinSwedish”.(turn69).Jannereiteratesthathedoesnotknowtheanswer. Duringthisstretchoftalkweseethatrepeating/clarifyingalsoconstitutesanimportantaspectoflocalchaining(turns64

Individual

diary

entries

and planning/instructive

texts

Weekl

y

plan

(Teacher)

Overhe

ad

instruction/Set

of questions

(Teacher)

School

diary

(Student)

Feedback

(Teacher/Parent)

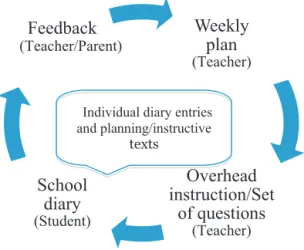

Fig.3. Layeredchainingintheschooldiaryliteracypractice.

and66,aswellas68and70).Inturn71,Jonasrepeatsthekeywordofthisinteraction,butnowinFinnish:“bowl”,after whichJanneprovidestheteacherwiththerequestedresponseinturn72.

Consideringthemicro-levellocallychainedinteractionrepresentedinturns64–72,wecanseethatFilippa,Hans,Janne’s andafourthstudent’sturnstogetherconstitutebotheffectivepeersupportandamultipartynegotiationofmeaningwhere fourdifferentparticipants,threekindsoforallinguisticvarieties(Finnish,Swedish,English)andtwowrittenlinguistic resources(Arabicnumerals&EnglishwordsintheLatinscript)onthewhiteboardarelocallychainedtooneanother.The metacommunicativeawarenessofthestudentsparticipatingintheaboveinteraction,(aswellastheinteractionrepresented inExcerpt1),isillustratedthroughbothspontaneoustranslationsandparaphrasingoftheteacher’scues.Interestingly,this collaborativeanddistributedworkinproducingtheresponseisevaluatedbytheteacherasJanne’ssingularaccomplishment (“good(.)youdoknow”[originalutteranceinSwedish],turn73).However,asExcerpt2illustrates,communicationgets accomplishedinconcertthroughtheworkofmanymembersinClass6Candtheuseofmultiplelinguisticandmodality resources.Onecanthusseethatthechainingofmultilingualliteraciesandlanguagingisperformedorplayedoutinthis communitythroughmembers’behaviorsthatarebothsituatedanddistributed.

Besidesillustratingacommonfeatureofmultilingualhumanbehavior,i.e.howthechainingofdifferentkindsoforaland writtenlinguisticelementsoccursintheclassroom,theexcerptsrevealsomeotherinterestingphenomena.Theyillustrate, forinstance,howstudentswithlimitedexperienceofSwedishcanbesocializedintomultilingualismandmultilingual waysofbeingandexemplifyhowlanguagingandchainingbecomerelevantformeaning-makingandsocialpositioning (seealsoBagga-Gupta,2012a,b).Furthermore,scaffoldingandpeersupportareillustratedhere.InExcerpt2,forinstance, Janne’sfailuretodeliveraresponsetotheteacher’sinitialqueryappearstobearesultofalackofexperiencewithboth EnglishandSwedish,butintheend,withthe(multilingual)helpofhispeershedoesindeedsucceedindeliveringthe correctanswer.Similarkindsofscaffolding,bothverticalorinstructional(theteacherextendingastudent’slearningby askingfurtherquestions)andhorizontallyorganizedgroupscaffolding(occurringamongpeers)areextensivelyillustrated byCazden(2001:60–68).Additionally,amultilingual-multimodalorderandpeerscaffoldingareestablishedineveryday mundaneclassroomlife,mainlythroughthedifferentiateddivisionofroles/positioningsamongtheparticipants.

Inadditiontothemultilingualandmultimodalrepertoiresthatareemployedineverydayinteractionalspacesbythe teachersandyoungmembersofClass6C,linguisticandmultimodalvariationsaswellaschainingoftheseelementsarealso visibleintheschooldiarypractice.Theanalysispresentedinthenextsectionhighlightsthisthroughtwoexamplesofdiary entriesaswellastheschooldiarypracticeassuch.

4.2. Amultilingual-multimodalchainedliteracypractice

SchooldiariesframetheweeklyplanningandaccomplishmentsofeachyoungmemberofClass6C.Theyconstitutea centralartifactthatframesschoolworkinthissettingaswellasprovideaspaceforportrayingdifferentidentificationsand positionings.Theschooldiaryalsoconstitutesaninstitutionalpracticeinwhichplanningandreportingacrossapredefined periodoftimeandactivitiestakesplaceatschools.Assuch,itisalsoanexampleofapracticewherelayeredchainingoccurs: First,acyclicchainingofactivitieswithinthepracticeacrosstime,suchasadministeringaweeklyplan,instructingdiary writing,writingdiaryentriesandgivingandreceivingfeedback.Thiscyclicactivitychainingisrepresentedbythe“global” outercircleinFig.3.Second,thelocallyoccurringchainingofdifferentlinguisticandmultimodalelementssuchaswritten textanddrawingswithinindividualdiaryentriesauthoredbythestudentsaswellastheinstructionsprovidedbytheadults

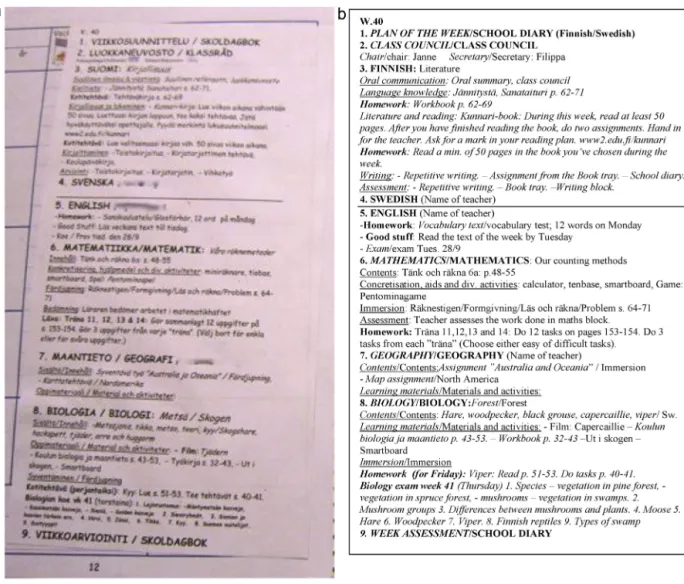

Fig.4. Weeklyplanauthoredbyteacherandpastedonleft-handsideofdiaryinFinnish/Swedish(originaltextonleftabove)withEnglishtranslation(on rightabove).Thecondensedtranslationmapstheconcentratedformatoftheoriginaldocument(seetranscriptionnoteinAppendixA).

inthepractice.Thislocalchainingisrepresentedbythe“core”inFig.3.Furthermore,thereexistsandinterconnectedness andaflowbetweenthelocalandcyclicactivitychaining.12

The interlinked and chained flow of activities acrosstime that occurs within the framework of the school diary bringstogethertheparticipationofdifferentpeople–teachers,theindividualstudent,thestudentsasagroup,andthe guardians/parents.Thechainingofthisstringofactivitieswheredifferentpeopleparticipateacrosstimeandspaceis repre-sentedschematicallybytheoutercircleinFig.3(comparewith“activity-chaining”discussedinBagga-Gupta,2000,2003, 2004a,and“cyclicchaining”inBagga-Gupta,1995).Fromaninstitutionalizedperspective,acentralpurposeofthediary istoallowforreflectionsupontheweekthathaspassed,inasimilarmannertowhathasbeendescribedintheliterature (seeSection2above).Inourdatathisisexpectedtobedonewiththehelpoftwoliteracyresourceslocatedattheouter circleofFig.3.First,a(bilingual)weeklyplan(seeFig.4)thattheteachercreatesandhandsouttothestudentsusuallyatthe beginningofeachschoolweek,andsecond,asetofquestions/instructionthatframestheworkdoneinfillingintheschool diary(seeFig.5),writtenmostlyinFinnishanddisplayedonanoverheadprojector(OH)duringthetimeallottedinthe timetableattheendofeachweekfor“writing”intheschooldiary.Thestudentsareexpectedtousethesetworesources(see Figs.4and5)aspointsofdepartureforaccomplishingtheactivitypertainingtotheirschooldiaries;ontheright-handsideof thetwo-pagedschooldiarytheyarerequiredtofillintheirreflectionsregardingtheweekthathaspassed(seeFigs.6and7) keepinginmindboththeteacher-authoredplanningthatispastedontheleft-handpageofeachstudent’sschooldiaryand thesetofquestions/instructionsthataremadeavailablepubliclyviatheOHduringclasstimeattheendofeachweek.

12Fromasocio-constructionalpointofviewitisconceptuallyratherreductionisttomanifestphenomenasuchaslayeredchaininginafigure.Thisis

Fig.5.Overheadinstruction/setofquestionsinFinnish(originaltextonleftabove)forwritingschooldiarywithEnglishtranslation(onrightabove)(see transcriptionnoteinAppendixA).

Fig.6.Hannes’sentryontheright-handpageofhisschooldiary(originaltextonleftabove)withtranslationfromFinnishtoEnglish(onrightabove)(see translationnoteinAppendixA).

Inadditiontoreflectingontheweekthathaspassed,anaspectofthetaskwithinthissemi-sanctionedactivityforeach studentistowriteaminimumof50wordsintheirindividualschooldiary.Theanalysispresentedbelowhighlightsthat theschooldiaryisusedforamultitudeofpurposes,includingnonpredeterminedofficialones.Ideally,thediariesarealso supposedtofunctionasameansofcommunicationbetweentheschool,childandparent,butinpractice,thisseldomseems tobethecase.Together,theweeklyplan,OHinstructions,thecompositeschooldiaryandfeedbackformacyclicchained practice(cf.Bagga-Gupta,1995),wheredifferentsetsofactivitiesandtheworkofdifferenthumanbeingsarelinked(see Fig.3).Thistypeofcollaborativeworkwithdistributedresponsibilitiesamongparticipantsiscommonlyaccomplishedby membersinmanykindsofinstitutions.Thecyclicchainingofdifferenttextsandactivitiesaswellasactors’contributionsto themalsocomprisesthefirstoftwospheresoflayeredchaining.Inthissphere,theinterconnectednessofactivitiesneedsto

Fig.7. Right-handpageofIris’sdiary(originalonleftabove)withtranslationfromSwedishtoEnglish(onrightabove)(seetranslationnotesinAppendix A).

beunderstoodmoregloballyintermsofdistributedresponsibilitiesamongparticipants,relationsbetweenthetextswithin theactivityandfinally,differenttemporalphasesoftheschoolweek.

Apartfromthegloballycomprisedchainedcyclicflowbetweenthedifferenttextsandactivitiespertainingtothediary practice,thereexistsanothertype oflocallyemergentinterconnectednesswithinthisliteracypractice,namelythatof differentlinguisticandmultimodalelementsinindividualdiaryentriesaswellasininstructivetexts(seeFig.3).Thetwo diariespresentedinFigs.6and7illustratethechainingofdifferentlinguisticandmultimodalresourceswithina“text”. Theauthorsofthesediaryentries,twoClass6Cstudents,HannesandIrisare12yearsofage.13Bothofthemaretypical representativestudentsfromClass6Cintermsoftheir“mixed”culturalheritageaswellastheiraccesstomultiplelinguistic resourcesintheirhomeenvironments.InHannes’scasethismeansthathisfatherisFinnish-bornandmotheris Chinese-born.HethushasahomeenvironmentwhereFinnish,ChineseandSwedishlinguisticvarietiesareused.Iris,ontheother hand,hasamotherwhoisFinnish-bornandafatherwhoisMoroccan-born.Iris’sparentsareseparated.Sheself-reports thathereverydaylinguisticenvironmentathomeconsistsprimarilyofFinnishandSwedish.

Hannes’sentriesinhisdiariesareoverwhelminglyinFinnish.Fig.6illustratesacommonmannerinwhichHannes’s contributionsaremade.Thisincludesasummaryoftheweek(seelinei)aswellasacommentaryontheschoolactivities ingeneral(linesvi–ix)anddiarywritingmorespecifically(lineii).Hannes’sentriesreflectacriticalperspectivetowardthis schoolliteracypracticeaswellaswhatheinfersintermsoftheteacher’sengagementinthepractice(linesiii–v,Fig.6).14 Thismessagegetsaccentuatedbothbythecontentsofhisentries,especiallythelistingof“boringsubjects”,andthedrawing ofatongue-stickingfacialcaricatureforthereaderofhisentry.Thisisalsowhereweobservelocalchaininginthewritten modality:thechainedconnectednessofa(Swedishlanguagebased)diarytemplate,hand-writtentextandahand-drawn picturewithinadiaryentry.Together,thesecreateaneffectandameaningthatcanbeinterpretedasanactofresistance towardaninstitutionalliteracypractice–ameaningthatwouldbelesspalpablewithoutthechainedvisualandtextual elements.Thesocialpositionhighlightedbythisdiaryistheoneof“acriticalstudent”.

Despitetheactsofresistance,thegloballyframedchainingofthedifferenttexts(teacher’scontributionsandHannes’s individualentry)inthisliteracypracticeisvisibleinthelocallyconstitutedact;Hannes’sconformingtowritinganentry –irrespectiveofwhetherhedesirestodosoornot.Withthisinmind,thelackofsubsequentreactionfromtheadult participantsinthepractice(forinstanceinthe“teacher’sandparents’space”ontheright-handpageofthediary,seeFig.6) isnoticeable.Theadultfeedbackcanbeinterpretedasunsatisfactoryatitsbestasonlytheinitialsoftheteachercanbe notedinthesquare,perhapssignaling,“Ihaveseenthis”.Theadultfeedbackcanalsobeunderstoodintermsofthe“weakest link”inthismoregloballyframedchainedcommunication.Thereforeitisreasonabletosaythatdespitethefoundingidea ofdialogicismbetweentheconstellationsteacher-studentandschool-home,theliteracypracticessurroundingtheschool diarydonotappeartoliveuptotheinstitutionallydesiredfunctionsascribedtoit.Asapractice,however,theschooldiaryis notjustcyclicandchainedinnaturebutisalsocollaborativelyandinstitutionallyaccomplished,whichreinforcesitsglobal characteristicsinthelayeredchaining.

Tofurtherillustratethechainingofdifferentlinguisticandmultimodalelementswithindiaryentries,wenowzoominto onanotherstudent,Iris’s,schooldiary(seeFig.7).

13SevendiaryentrieswrittenbyHannesandfiveentriesauthoredbyIrisconstitutepartofthisdatatypeinprojectDIMuL.Theirnames,aswellasall

othernamesusedinthispaperhavebeencodedforethicalreasons.

14OneofHannes’sdiaryentriesinparticular,consistsoftheFinnishwords“50sanaa”(English:50words)written25timestofulfilltheformalcriteria

Iris’sentriesareusuallywritteninSwedish,ascanbeseenintheexamplepresentedaboveinFig.5.Herdiaryentry startswithasummaryoftheweek(linei),withareferencetoaneventthathaslittletodowithschoolactivities(lineii). Commentingthesetextmessages,sheusessmileys(inspiredbydigitalconventionsinfree-handwriting)aswellasslang, resourcesfromdifferentlanguagevarietiesandconvention-mixing(linesiii–iv).Irisbuildsherfocusonissuesoutsideformal instructionandschoolbusinessbyreportingthatsheisbeingbulliedbyanothergirl(linev)andclaimsfuturecounteraction (linesvi–viii).Thus,intermsofcontent,Iris’sdiaryentrydiffersconsiderablyfromHannes’s,which,despitedisplaying resistance,primarilyfocusesupon(institutional)schoolactivities.Irisseemstobringherlifeoutsideformalschoolinto schoolintheinteractionalspaceprovidedbytheschooldiary.

Nevertheless,boththeseexamplediariesillustratethesecondessentialaspectoflayeredchainingwhenelucidating locallyframed(seethecoreinFig.3)chainingoflinguisticandmultimodalelementswithinthediaryentriesastexts.In additiontocombininghand-writtentextwithsmileyimagesinasimilarfashionasinHannes’sentry,Iris’sdiaryentry displayswordswrittenincapitals(“UNKNOWN”,“NOO”,“NOT!”“AAJA”,“PUNC”)toexpressemphasis.Thisisacommon conventioninbothchildren’sandadults’writinginbothdigital(cf.HårdafSegerstad&SofkovaHashemi,2004;Messina DahlbergandBagga-Gupta,2012,submittedforpublication)andnon-digital(seeBagga-Gupta,1995,2012a)environments. InIris’sdiary,theyaccentuatethefeelingofprivacyinthetext,aswellasservetoanimatethedramaoftheeventsthatare beingreported.ThisappliesalsotothepresenceofEnglishinthediary.Thewords“scary”,“NOT”,“theBitc[h]”intensify Iris’smessage,andaccentuatethefeelingof“writingasonespeaks”,aswellasexemplifytheinterconnectednessoftwo linguisticvarieties:SwedishandEnglish.

BothHannes’sandIris’sentriesillustrateacommonthemethathasemergedintheanalysisofthematerial:thisrelates tothemakingoffeaturesofspokenvernacularavailableinthewrittenmodality.Thus,eventhoughmostofthestudents generallyseemtoorienttowardthestandardwrittennormsofprimarilyFinnish,theyfrequentlyemployfeaturesofspoken Finnish,SwedishandEnglishintheirdiaryentries.Furthermore,andyetagainconnectedtoamoregloballyframedlevelof chaining,despiteappearinginthe“weeklyplan”asapartofthe“writingagenda”ofthesubjectFinnish(seeFig.4agenda 3:“3.FINNISH,Writing”),itisapparentthatparticipantsdonotaccordthediariesthesamestatureasotherformalliteracy practicesintheschoolcontext.Thisisemphasizedalsobythefactthattheschooldiaryisnotmentionedundertheheadline “Assessment”intheweeklyplan(seeFig.4agenda3:“3.FINNISH,Assessment”).

Tosummarize,Iris’sdiaryentryrepresentsacommonfeatureinthedatawhereinthereisatransferofnormsandelements fromonemediatoanother.ThesmileysoremoticonsinIris’stextaswellasothersymbolcombinationscommonlyseen ine.g.technology-mediatedcommunicationillustratehowtheconventionsofwritingindigitalizedmilieus(socialmedia viacomputers,mobiles,etc.)arenowsurfacinginhand-writtenliteracypractices.Inadditiontoillustratinghowyoung people’sexpertiseincommunicationindigitalmilieusspillsoverintoanimatedandnewhybridformsofcommunicating innon-digitalmilieus,theanalysisalsodemonstrateshowconventionalwritingandvisualhand-drawnimagescoexist multimodallyinyoungpeople’sliteracypractices.Chainingofdifferentelementsmorelocallyinatextbecomesvisibleas animportanttechniqueformeaning-makingintheseprocesses.Moreover,bringinglinguistic,includingliteracy,resources morecommonlyusedine.g.socialmediaworldsintoclassroomsettingsinthistypeofliteracypracticeallowsustogeta glimpseofhowyoungpeoplestagesocialpositioningsinandthroughtheireverydaywritingwork.Itisnormallynoteasy togaininsightonsuchprocessesthroughwrittenrecordswithintheinstitutionalframeworkoftheschool.

5. Chaininginandbetweenlanguagevarietiesandmodalities.Concludingreflections

Thestudypresentedherehighlightsthecomplexityandhybridnatureofyoungpeople’slanguagingincludingliteracy practicesinamultilingualeducationalsettingwhereSwedishandFinnishareformallyunderstoodasframinglearningand instruction.Throughtheanalysisofethnographicallycreateddatasetsandactivitytypes,specificallymundanedailysocial interactionduringlanguage-focusedinstructionandschooldiaries,thisstudyhasillustratedthewaysinwhichyoungpeople andadultsininstitutionalsettingsemployarangeoflanguagevarietiesandmodalitieswhenparticipatingin meaning-making.Moreimportantly,theanalysispresentedhereilluminatesthechainednatureoflanguaging,i.e.theusageoforal, writtenandothersemioticresources,includingatleasttwo,sometimesthree,languagevarietiesthatareavailabletothe participantsinlearningenvironments.

Theanalyticalfindingsofourstudyhaveanumberofimportantimplicationsfortheunderstandingofhumanbeings’ languagingandsocialpositioningineducationalsettings.First,theanalysisofthedatasetsfocuseduponinthisarticlehas shownthattheconceptofchainingallowsforthe(re)examinationand(re)interpretationofhumanbeings’participationin variouskindsofcommunicativeactivitieswhereliteracyplaysarole.Drawingattentiontotheinterconnectednessoforal, writtenandothersemioticresourcesinhumancommunicationratherthanemphasizingtheseparatenaturesofe.g.different linguisticcodesorwrittenandoraltextsentailsanovelwayofunderstandinglanguagingandmeaning-makingpractices. Toexemplify,wecontendthatthelargebodyofliteraturethathasfocusedmultilingualismfromamicro-interactional perspectiveprimarilyhighlightsoraluseoflanguage15andeticperspectivesonlanguageuse,whereintheanalystshighlight boundariesbetweencodesinplay,ratherthanthefluidityinherentinthemeaning-makingenterprisethatparticipantsorient

towardineverydaylifesituations.Thepresentstudyemphasizestheimportanceofhighlightingtheinterplayoforal,written andothermodalitiesfromarangeofdatasets,bothmicro-interactionalandmesoscaleanalysisofliteracypractices.

Second,chainingasaphenomenonseemstoemergeinspacesthatarerichinwhatmaybecalledmultilingual–multimodal interactionsanddiscourses.Whetherthesespacesareconstructedlocallyatthemicro-interactionalscale–asseeninthe analysesof“Swedishlesson”zoomedintointhepresentstudy–oratthemesolevelasseenthroughtheflowofactivities relatedtotheschooldiaryliteracypractice,chaininghasbeenillustratedasplayinganintrinsicroleforinteractionwhere differentlinguisticvarieties,modalitiesandsemioticresourcescometogether.Ouranalysesillustratethecomplexityof linksbetweendifferentresources,varietiesandmodalities.Thisconstitutesanoverridingthemeinthedata.Theobserved phenomenainthemicro-interactionallevelinthepresentstudyresemblefindingsfromtheDeafStudiesfield,wherestudies sincethe1990shaveshownthatchainingisaccomplishedininterestingwaysincommunitieswheretwoormorelanguage varieties(forinstanceEnglish&AmericanSignLanguage,Swedish&SwedishSignLanguage)areusedinschooland/or homesettings.Thishasbeenshowntobeespeciallyrelevantwhennewvocabularyknowledgeisintroducedordiscussed indifferentsocialpracticesbothinsideandoutsideinstitutionalsettings.Forinstance,HumphriesandMacDougall(2000) suggestthattheanalyticallyframedlanguaging,i.e.chaining,whereAmericanSignLanguage-Englishlanguagevarieties areusedoccurswhenadultsintroducenewcontentorEnglishvocabulary.This,theysuggest,canbeinterpretedbothas amethodforsignalingdistancebetweentwolinguistic-cum-modalresourcesandforbridgingthegapbetweenthem.The examplesthatrepresenttheanalysisinthepresentstudyreinforcethisissue,especiallyintermsofopeningupmeaning potentialsofconceptsthatstudents/adultsorpeersmighthavelimitedexperiencesin,inSwedishorFinnishorEnglish.The micro-interactionalexamplesdiscussedhereincludealsoIRE/IRF-sequencing(cf.Mehan,1979;Sinclair&Coulthard,1975). Throughcarefulexaminationoftheseexamples,itcanbeconcludedthattheconstructionofthethreephases (initiation-response-evaluation/feedback)occursinseveraldifferentways.InExcerpt1,bothteacherandstudentsparticipateinthe constructionofinitiation,butalsointheshapingoftheresponse,wherecollectiveandchained(re)productionisespecially salientintheinteractionalsequencerepresentedinExcerpt2.Moreover,differentmembers’participationinthe meaning-makingenterprisealsoreinforcesthechainednatureofthesocialpractice.Thischainingofdiverselinguisticandmultimodal resourcesconstitutesanimportantelementoflanguaging(seealsoJewitt,2009).

Third,chainingcanbeseenasemergingincircumstanceswhereinterconnectednessacrossdifferentscalesofanalysis becomesanimportantissue.Intheliteracypracticeframedbytheschooldiariesthechainingoflinguisticandmultimodal resourcesbecomesvisibleinanequallysignificant,albeitsomewhatuniquemanner.16Animportantfindinghereiswhat wecalllayeredchaining,illustratedintheemergenceoftheoverarchingschooldiarypracticethroughtheflowofcyclic andrepetitiveactsand activitiesofdifferentparticipants(whathasbeencalled“activitychaining”intheliterature)– includingthechainingofdifferentlinguisticandmultimodalelementswithinindividualdiaryentriesandinstructivetexts andtheinterplaybetweenthese(whathasbeencalled“localchaining/linking”intheliterature).WhenDysthe(1996,p. 103)describesoneofthefunctionsoflogbookwritingaslinking,sheemphasizestheaffordanceofthelogbooksinterms ofprovidingstudentswiththepossibilityofdialoguingwiththemselvesandthuscreatinglinksbetweenone’spersonal selfandtheoutsideworld,betweenhistoricalandcurrenteventsandbetweenbitsofknowledgesummonedfromdifferent areasoflife.Chaininginouranalysisis,however,examinedfromaslightlydifferentpointofview.Theanalyticalfocusison theinterlinkedflowofactivities,linguisticandothersemioticresourcesandmembers’participation,ratherthanfocusing individualinternalprocesseswithintheperson.Moreover,featuresoflogbookspresentedbyDysthe(1996)aswellas BergqvistandSäljö(2004)andHalse(1993)canalsobeidentifiedintheliteracypracticesthatframeschooldiariesinthe presentstudy.InconcertwithBergqvistandSäljö’s(2004:111)observationsregardingchild-centeredpedagogy,thepresent studyalsohighlightstherelevanceofstudents’participationinplanningactivities–aswellaspossibilitiesandlimitations withinpracticesofthiskind.

Insummaryoftheabove,theconceptofchaininghasanalyticalrelevancefortheexaminationofpracticeswhere rela-tionshipsbetweenvariousformsofmultilingual–multimodalcommunicativeresourcesarefocused.Fourth,highlighting chainingasananalyticalconceptallowsustoexaminesocialpositioningandidentityworkfromanewangle.The find-ingsofthepresentstudyillustratethatparticipationin dailyinteractionand literacypractices inwhatcanbetermed multilingual–multimodaleducationalsettingsoffersyoungpeoplespecificopportunitiesforstaging,makingvisibleand (co)constructingboththeirownandtheirco-participants’socialandidentitypositioningsatthemicro-interactionallevel. Assuch,theusageofdifferentkindsofcommunicativeresourcesalsoappearstohighlightthefluidandlinkednatureof identities-in-actionatthemicrolevel,whileconstructinglocalandtemporarysocialpositioningssuchas:“beingahelpful student”or“beingalearnerofSwedishorEnglish”.Intermsofliteracypracticessuchastheonethatframesschooldiaries, theyoftenstemfromaninstitutionalenterprise,butalsorelatetoliteracyhabitsandfunctionsinthestudents’semi-private sphere.Ashasbeenillustratedinthisstudy,theaffordancesoftheschooldiarypracticegobeyondtheinstitutional frame-work.Thus,apartfromfulfillingtheinstitutionallyprojectedgoalswithinthepractice,theschooldiarycanbeconsidered bothaspacewherelifeagendasmorebroadlycanbefocusedandatoolforportrayingsocialpositioning.Forinstance,the diariesforcebutalsoofferparticipantsachanceforlocatingthemselvesinrelationtotheactivityathand–conformingto writingcanalsoincludeanactofresistanceasseenintheanalysis.Furthermore,reflectionsinindividualdiaryentriesmay

alsopositionastudentinrelationtothesurroundingworldbothwithinandbeyondschoolactivities.Thussituatedidentities thatareorientedtowardindiarywritingintermsof“beingagoodstudent”(byfulfillingthetaskofwriting)canalsobecome shapedintermsof“beingadissatisfiedstudent”or“beingabulliedstudent/asocialoutcast”,etc.Theconnectednessof diverselinguisticandmultimodalresourcesplaysacentralroleinstagingthesesocialpositioningsandaspectsofidentity. Onecansaythatlanguagingortheways-with-wordsinitselfenablestheidentificationprocessesortheways-of-beinghere. Theoverarchingframeworkfortheresearchpresentedheredealswiththeissuesoffluidityoflanguagingandsocial positioning.Aswesummarizeinthisconcludingsection,thiscanbecontrastedwiththestrictcode-perspectivesonlanguage varietiesinpolicies,thefocusonlanguagecompetenciesasaspectsof“stuff”thathumanbeingsown,andthefocusupon traditional.Thefindingspresentedhereindicatethatbeingapartofamultilingualcommunitysuchastheonethatconstitutes theSwedish-FinnishschoolaswellasClass6Calsomeansusingawiderangeoforal,writtenandothersemioticresources inlearningandinstructionandperformingsocially.Thus“beingbilingual”canbeunderstoodashavingaccesstoandbeing abletoparticipatein(institutional)multilingualcontextsinafruitfulmanner.Finally,fromadidacticpointofdeparture, theresearchpresentedherehasrelevanceforissuesthatdealwiththeconstructionofandtheflowofeducationalpractices thattakeplaceinallclassrooms–irrespectiveofwhethertheseareformallyidentifiedasbeingmultilingualornot.Creating learning environmentsthatarenotonlyrich intermsofdiverselinguistic(includingliteracy)resources,but thatalso creativelyandeffectivelyemploydifferenttoolsandaffordancesthemembersthemselvesbringintoclassroomsisachallenge forinstitutionaleducationbothinSwedenandelsewhere.

Acknowledgements

ThestudypresentedinthispaperisconductedaspartoftheDIMuLprojectwithintheSwedishResearchCouncilsupported multi-disciplinarynationalresearchschoolLIMCUL(YoungPeople’sLiteracies,MultilingualismandCulturalPracticesin EverydaySociety).TheprojectandtheresearchschoolarebothaffiliatedtotheCCDresearchenvironment(Communication, CultureandDiversity)atÖrebroUniversity,Sweden.Wewouldliketoacknowledgecriticalfeedbackreceivedtoprevious versionsofthisarticlebytheblindreviewersofthisjournalaswellasmembersofDIMuLandCCD,includingJarmoLainio andMarja-TerttuTryggvason.

AppendixA. Transcriptionnote

Transcriptionkeyforschooldiaries(Figs.4–7).

bold originaltextinEnglish italics originaltextinFinnish regular originaltextinSwedish #you# vernacular

[name] authorcommentary

Transcriptionkeyforinteractionmaterial(Excerpts1and2). bold originalutteranceinEnglish italics originalutteranceinFinnish regular originalutteranceinSwedish

Hello stress

** denotatessmileyvoice

(xxx) inaudible

(here) unsuretranscription ((looksup)) non-verbalaction [look] overlappingutterances (.) pauselessthan1s (1.0) pauselongerthan1s

References

Antaki,C.,&Widdicombe,S.(1998).Identitiesintalk.London:Sage.

Aspers,P.(2007).(Ethnographicmethods–Understandingandexplainingthecontemporary)Etnografiskametoder–Attförståochförklarasamtiden.Malmö, Sweden:Liber.

Bagga-Gupta,S.(1995).Humandevelopmentandinstitutionalpractices:Women,childcareandtheMobileCreches(130)Linköping,Sweden:Tema,Linköping University,StudiesinCommunication.

Bagga-Gupta,S.(1999).Instructionalinteraction.PractisinglanguageandthepracticesoflanguageatthebilingualSwedishSchoolsfortheDeaf.InPaper presentedattheSymposium“LiteracyMattersInside&OutsideClassrooms”atthe8thBiennialConferenceofEARLIEuropeanAssociationforResearchon LearningandInstructionGothenburg,Sweden,August,

Bagga-Gupta,S.(2000).VisualLanguageEnvironments.ExploringeverydaylifeandliteraciesinSwedishDeafbilingualschools.VisualAnthropologyReview, 15(2),95–120.

Bagga-Gupta,S.(2002).Explorationsinbilingualinstructionalinteraction:Asocioculturalperspectiveonliteracy.JournaloftheEuropeanAssociationon LearningandInstruction,5(2),557–587.

Bagga-Gupta,S.(2003).Gränsdragningochgränsöverskridande.IdentiteterochspråkandeivisuelltorienteradeskolsammanhangiSverige.InJ.Cromdal,& A.-C.Evaldsson(Eds.),Ettvardagslivmedfleraspråk.Ombarnsochungdomarssamspeliflerspråkigaskolsammanhang(pp.154–178).Stockholm,Sweden: Liber.