Author: Josephine Mittag ID: 950519-T107

josephinemittag@gmail.com Malmö University

Department of Global Political Studies

Subject: Human Rights (SGMRE15h), 15 ECTS Autumn 2018

Supervised by Lena Karlbrink Word count: 16,490

2018

Stolen Childhoods:

Remembering the Former Child

Soldiers Abducted by the Lord’s

Resistance Army in Uganda

Acknowledgments:

To my loving family, without your everlasting support and encouragement, I would not be where I am today. You give me the strength to follow my dreams and inspire me to dream bigger.

A special thanks is dedicated to the following people who made my minor field study in Gulu a reality:

Ida Scharla Løjmand – my friend and colleague – for teaching me Swedish and enabling me to

apply for the grant and for always being there for me.

Godfrey Canwat – Executive Director of Hope and Peace for Humanity, Uganda – for your

friendship and extensive support throughout my research.

Atim Daisy – for welcoming me into your home. I truly miss your jolly and loving soul.

The team at Hope and Peace for Humanity, Uganda – for accepting me into the family, your

encouragement, and kindness. I have nothing but immense gratitude and respect for you.

Lanam Stella Angel – Founder and Country Director of War Victim Children Networking – for

sharing your personal story and introducing me to the formerly abducted children who were interviewed for this study. You are an incredible woman with a generosity that inspires me and others in your community.

Peter Nicho, his family, and friends – for introducing me to your country and making sure I had

an incredible time in both Uganda and Tanzania.

Also, a special thanks to my translators, Bryan Eryoung and Wao Acellam, who enabled me to do my interviews in the field and in Luo. But most importantly, to all the research participations who chose to share their personal stories, thoughts, and fears. I am eternally grateful and honored that you chose to share it with me.

Abstract

The prohibition on the use of child soldiers is widely recognized. Still, it is estimated that 60,000 children were abducted and forced to take part in the internal armed conflict between the Lord’s Resistance Army and the Government of Uganda. Thus, this study examines how the formerly abducted children have experienced their return and reintegration. The thesis is based on a minor field study conducted in Gulu and aims at investigating whether the provision of remedies aids or hinders their reintegration. Using theories of recognition and a conceptualization of successful reintegration, I analyze the semi-structured interviews with fourteen former abductees and ten other community members. The findings suggest that the process of return is fraught with many

challenges. It is concluded that the absence of symbolic and material reparations is an obstacle to successful reintegration and sustainable peace as the lack of recognition can drive future social conflict in Uganda.

.

Keywords: child soldiers, human rights, peace, recognition, reparations, transitional justice, Lord’s Resistance Army, State Responsibility, Uganda

Table of Contents

1. Introduction 1

1.1. Introduction of Topic 1

1.2. Relevance to Human Rights 1

1.3. Previous Research 2

1.4. Aim and Research Problem 3

1.5. Research Question 3

1.6. Material, Method, and Theoretical Approach 3

1.7. Delimitations 4

1.8. Disposition 5

1.9. Definition of Terms 5

2. Background 6

2.1. The War in Northern Uganda (1986-2010) 6

2.2. Children’s Rights in Armed Conflict 7

2.3. The Right to an Effective Remedy 8

2.3.1. The State Responsibility to Respect, Protect, and Fulfill Human Rights 8

2.3.2. The Legal Right to an Effective Remedy 8

2.3.3. Why Does It Matter? 9

2.4. Domestic Policies and Development Programs 10

3. Theoretical Approach 12

3.1. Reintegration 12

3.1.1. Definitions 12

3.1.2. What Does Successful Reintegration Mean? 12

3.2. Transitional Justice and Theories of Recognition 13

3.2.1. Transitional Justice and Peacebuilding 13

3.2.2. Recognition as Transitional Justice 14

3.2.3. The Importance of Mutual Recognition 14

4. Method 19

4.1. Semi-Structured Interviews 19

4.1.1. Primary Target Group 20

4.1.2. Secondary Target Group 20

4.1.3. Sampling and Data Collection 21

4.1.4. Delimitations 21

4.2. Ethics 22

5. Analysis 24

5.1. Material Reparations in Northern Uganda 24

5.1.1. Individual Material Reparations 24

5.1.2. Collective Material Reparations 25

5.2. Symbolic Reparations and the Lack of Recognition 29

5.2.1. Individual Symbolic Reparations 29

5.2.2. Collective Symbolic Reparations 29

5.2.3. Lack of Recognition 30

5.3. Suggestions for Successful Reintegration 33

5.3.1. Prioritized Material Reparations 34

5.3.2. Prioritized Symbolic Reparations 35

6. Discussion 36

7. Summary and Conclusion 40

References 42

Appendix 59

1. Presentation of Interviewees 59

Primary Target Group: Formerly Abducted Children (FACs) 59

Secondary Target Group: Other Respondents 61

2. Interview-Guides: 62

Primary Target Group: Formerly Abducted Children (FACs) 62

List of Abbreviations and Acronyms:

ACHPR……….(OAU) African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (1981) ACRWC………...(OAU) African Charter on the Rights and Welfares of the Child (1990) AEI………-…………...………..Acholi Education Initiative AP II Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts (Protocol II) (1977) ARLPI………..Acholi Religious Leaders Peace Initiative ASF………..Avocats Sans Frontières CRC………..(UN) Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) CSO……….Civil Society Organization FAC………...Formerly Abducted Child GoU………..Government of Uganda GUSCO………..Gulu Support the Children Organization HPH……….Hope and Peace for Humanity, Uganda HRW Human Rights Watch ICC………....International Criminal Court ICCPR………. …(UN) International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966) ICESCR (UN) International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966) ICTJ………..…International Center for Transitional Justice IDP……….Internally displaced persons LRA……….Lord’s Resistance Army NGO………Non-governmental organization NUSAF………...Northern Uganda Social Action Fund OHCHR………...(UN) Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights OPAC……….…Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict (2000) PRDP………Peace Recovery and Development Plan for Northern Uganda RS Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (1998)

UGX Ugandan Shillings

UHRC………...Uganda Human Rights Commission UPDF……….Uganda People’s Defence Forces UN………..United Nations

UN Basic Principles………. UN Basic Principles and Guidelines on Remedy and Reparations for Victims of Gross Violations of International Human Rights Law and Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law (2006)

UNDP United Nations Development Programme

UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund

1. Introduction

1.1. Introduction of Topic

The involvement of children in armed conflicts is an increasing problem (Singer, 2006). The armed conflict in Northern Uganda was, with its more than 20 years, one of Africa’s longest-running conflicts. The conflict between the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) and the government forces (UPDF) started in 1986. It has led to the abduction of approximately 60,000 children by the LRA (Blattman & Annan, 2008). At some points, child soldiers made up as much as 90% of their forces (Amnesty, 1997). Children have a legal right not to be targets of war (ICRC, Rule No. 136). But what significance does this right, or any human right for that matter, have, if remedies are not provided when it is violated (Ziegler, 1987)? While Uganda has complied, to some extent, with its legal obligations to remedy human rights violations as the situation was referred to the International Criminal Court (ICC-02/04), the Amnesty Act of 2000 has been criticized. It has been argued that issues of justice and impunity need to be addressed if former abductees are to successfully

reintegrate into the Ugandan society (Ochen, 2014; Roach, 2013).

1.2. Relevance to Human Rights

While other countries face similar problems with forcible abductions of children during armed conflict, Uganda is of particular importance due to its voluntary referral of the situation to the ICC. However, Uganda’s legal obligations are not restricted to those under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (1998) but also encompasses various international human rights treaties. Thus, this paper is very relevant to the study of human rights as it investigates the

connection between the State’s legal obligations and the experiences of the individual victims. The study will be useful for Uganda as it can point out potential gaps or tensions. Investigating how individuals are able to claim their rights in a post-conflict setting is not just a matter of transitional justice. It is important for human rights as they are derived from the inherent dignity and equality of all peoples. However, if you are not recognized as an equal member of society, they have little significance. How can former child soldiers be successfully reintegrated if they are unable to access their fundamental rights? The insight offered by the experiences of former abductees may

contribute to the development of improved remedies for the victims of gross human rights violations.

1.3. Previous Research

As a vast number of studies has been undertaken in Northern Uganda, it is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss all of them. Thus, common findings on the obstacles and opportunities for

successful reintegration of former abductees in Northern Uganda will be discussed before elaborating on the existing gap, which this paper seeks to fill in.

First of all, high levels of psychological distress have been documented with 49 % to 67 % of former abductees meeting the criteria of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Pfeiffer & Elbert, 2011; Pham, Vinck & Stover, 2009). However, the high levels of serious distress are questioned by Annan et al. (2011) who argue that the most people are resilient. Second, it has been clear that a lack of educational opportunities hinders reintegration (Annan, Brier & Aryemo, 2009; Singer, 2006). Third, as many as 76% of the returnees participated in killings and other atrocities (Annan et al., 2011; Vindevogel et al., 2011). The effects of these war experiences have direct consequences (e.g. psychological distress) and secondary effects as concentration issues or social stigma can hinder successful reintegration (Singer, 2006; Vindevogel et al., 2011). The lack of access to reintegration programs have also been stressed (Annan, Brier & Aryemo, 2009; Muldoon et al., 2014; Pham, Vinck & Stover, 2009). Lastly, the level of community support for social reintegration is a subject of debate. Annan et al. (2011) argue that “support from families, not rejection, is the norm” (p. 902). However, Osborne, D’Exelle & Verschoor (2018) make use of behavioral experiments and surveys to show that long-term abductees are discriminated against by other community members. There is also a rising awareness of the risks of giving reparations exclusively to former abductees. Issues may arise since the armed conflict affected other

community members as well. Thus, it has increasingly been argued that reintegration programs and policies must include all (Amone P’Olak, 2007; Annan, Brier & Aryemo, 2009; Blattman & Annan, 2008). Taken together, these findings indicate that the successful reintegration of former abductees in Northern Uganda is a complex process with many obstacles.

While previous research has investigated the relation between remedies, recognition, and transitional justice, none of the studies are specific to the case of Northern Uganda (Stanley, 2005; Tirrell, 2015). Nobody has sought to understand the reintegration of formerly abducted children in Gulu through the theoretical lens of recognition and redistribution. My research seeks to fill this gap in existing literature as an increased understanding of the connection between Uganda’s obligations under public international law and the personal experiences of former abductees have the potential to inform better policies.

1.4. Aim and Research Problem

Justice requires that we are much more concerned with the particular individuals whose rights were violated. As former child soldiers are by no means a homogenous group and the right to an effective remedy for human rights violations is an individual right, it is important to understand reintegration from the victim’s point of view. While full reintegration is a complex and long-term process, which is, perhaps, never achieved, my interest is to study the correlation between the individual’s legal rights and their lived experiences. I submit that theories of recognition can contribute to existing research by facilitating a greater understanding of the harms and needs which transitional justice must address to ensure successful reintegration. Hence, I set out to investigate whether the remedies provided to FACs in Gulu are effective from the perspective of the concerned individuals. It can be questioned whether the effectiveness of particular remedies is measurable. However, I will not discuss the effectiveness from a legal perspective but rather explore the individuals’ own views. Thus, the effectiveness is based on their own perceptions and unique experiences. My aim is to discuss whether the provision of different remedies to former abductees aids or hinders the reintegration process. The paper is based on a minor field study focusing on their experiences of return. It seeks to provide a deeper insight into the needs and challenges of some of the 60,000 former child soldiers, 10 years after the unofficial end of the armed conflict.

1.5. Research Question

I seek to answer the following research question:

• How do former abductees in Gulu experience their reintegration and return to the communities?

1.6. Material, Method, and Theoretical Approach

The material for this study is unique as it was obtained during a nine-week field study in Gulu, Northern Uganda. Gulu was chosen as it was one of the areas which were severely affected by the armed conflict between the UPDF and the LRA (UNICEF, 2014). My primary sources include semi-structured interviews with 14 formerly abducted children lasting between 25 minutes and 1 hour 45 minutes. The notable difference in the length of the interviews is due to the importance of enabling the interviewees to describe their personal experiences of return and reintegration in their own voice. Other primary sources are treaty law, UN reports, resolutions, soft law, and relevant

case law. Secondary sources consist primarily of 10 semi-structured interviews with professionals working with the reintegration of former abductees, community leaders, and a state official. Three of the interviews lasted between 30 to 60 minutes, while seven took between 1 hour and 1.5 hours. This can best be explained with reference to the chosen method as semi-structured interviews enable the interviewees to add related topics and the researcher to ask clarifying questions. Lastly, other secondary sources including academic books, journal articles, and NGO-reports will be used.

A mix of theoretical approaches is undertaken to gain a deeper understanding of the former abductees’ experiences of reintegration. The use of theories of recognition and a

conceptualization of successful reintegration offers a more comprehensive understanding of their personal experiences. It enables a discussion of the complexity of the process of reintegration and makes it possible to point out any tensions between the State’s legal obligation to provide remedies to victims of human rights violations and their lived experiences. It illustrates the importance of the right to an effective remedy for both the individual and the State as claims for recognition can drive future social conflict.

1.7. Delimitations

The thesis will not focus on the experiences and acts undertaken by former abductees during the period of abduction. Nor will it investigate the extent of Uganda’s economic resources and the impact that this might have on the availability of remedies. Furthermore, it will solely focus on reparations as part of a transitional justice framework. Although the benefits and challenges of other transitional justice measures, e.g. truth-telling, are important subjects to study, that is beyond the scope of this paper. While this study included only FACs and individuals with specific knowledge and experience gained from working with that target group, it would have been interesting to interview other community members as well. If possible, it would have been appropriate to

interview more state officials since the State has a responsibility to remedy human rights violations. As the research is based on primary and secondary data specific to Gulu, the findings of the study cannot be generalized without further research. While the study might be relevant to other post-conflict situations, it is disputable whether the conclusion is valid across contexts or if additional data is collected. There are also, arguably, other factors which might impact or explain the reintegration process of former abductees in Gulu.

1.8. Disposition

In Chapter 1, I have introduced previous research and my research problem, aim, research question, methodological and theoretical approach as well as the delimitations of the study. Next, a number of important terms are explained in section 1.9 in order to further the reader’s understanding. Then, background information on the conflict, the rights of the child during armed conflict, and the post-conflict policies and programs in Uganda are presented in Chapter 2. Subsequently, the thesis proceeds in Chapter 3 with an outline of its theoretical approaches. In Chapter 4, the selected method and ethical concerns are discussed. Then, the results of the field study are presented and analyzed in Chapter 5. The discussion in Chapter 6 will point out any tensions between the State’s legal obligation to provide victims of human rights violations with an effective remedy and the former abductees’ personal experiences of return and reintegration. Lastly, Chapter 7 will provide the reader with a summary and conclusion.

1.9. Definition of Terms

For the purpose of this paper, a child is understood to be any person below the age of 18. This definition is found in various international treaties including Art. 1 of the CRC (1989) and Art. 2 of the ACRWC (1990). As Uganda is a State Party to both treaties, it is also included in Art. 257 (1) (c) of the Constitution of the Republic of Uganda (1995) and section 2 of the Children Act (1997).

A child soldier is a child “who is part of any kind of regular or irregular armed force or armed group in any capacity, including but not limited to cooks, porters, messengers, and those accompanying such groups, other than purely as family members. It includes girls recruited for sexual purposes and forced marriage” (Cape Town Principles and Best Practices, 1997). This definition, which is soft law, has been widely accepted and is used by the UN (UNICEF, 2003).

For the purpose of this paper, I define a formerly abducted child (FAC) or former abductee as a person who was forcibly removed from their home and served as a child soldier for the armed group, the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA). Similarly, a returnee is a formerly abducted child who has returned to his or her community by means of e.g. escape or rescue.

Lastly, a victim is someone whose fundamental legal rights have been violated. It does not mean that the individual is perceived as passive with no personal autonomy or agency.

2. Background

Uganda is a landlocked country in East Africa with a population of about 35.6 million. Uganda was a British colony and became independent in 1962 (BBC, 2018). Uganda is classified as a low-income country with a GNI per capita of 995 USD or less (World Bank, 2018). The Northern region has the country’s highest poverty rate (UNDP, 2014).

2.1. The War in Northern Uganda (1986-20101)

The more than 20 years of armed conflict between the LRA and the UPDF started in 1986 after Yoweri Museveni overthrew the president, Milton Obote. One of the guerrilla forces in Northern Uganda, who resisted his takeover, was the LRA that under the leadership of Joseph Kony employed a strategy of forcibly abducting children (Blattman & Annan, 2008). Approximately 60,000 children and youth have been abducted by the LRA in the course of the conflict with minors making up as much as 90% of the LRA forces at some points (Amnesty, 1997; Blattman & Annan, 2008). The conflict was strengthened by geopolitics as the Khartoum-government of Sudan

supported the LRA while the Government of Uganda aided the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) (Borzello, 2007; Conciliation Resources, 2014).

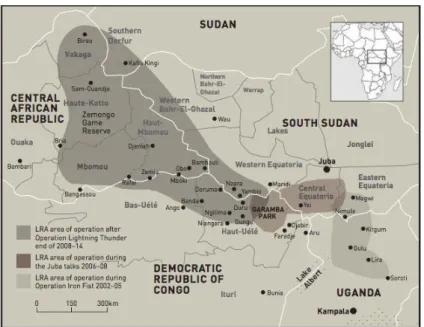

Figure 1: Map of LRA activity. This map is intended for illustrative purposes only (Conciliation Resources, 2014).

1 NB: While the exact timeframe of the war is debatable, this indication is based on previous research and the

The GoU has also been criticized for its forcible displacement of approximately 400,000 civilians, mainly from Gulu district, into ‘protected villages’ between 1996 and 2000 (HRW, 2003; UN OHCHR & UHRC, 2011). Sometimes, force including bombs and threats of physical violence were used by the UDPF soldiers to force the civilians to go to the camps (UN OHCHR & UHRC, 2011). While the ‘villages’ were supposed to protect the civilians from LRA-attacks and abductions, the UPDF did not offer adequate protection to the civilians and, indeed, failed to intervene on multiple occasions (HRW, 2003). Still, the GoU has tried to resolve the conflict by e.g. adopting the Amnesty Act (2000), which exempts former combatants from punishment and prosecution in order to

facilitate peace. It has made the return of more than 26,000 former combatants possible (Africa Research Bulletin, 2012). The five senior leaders of the LRA are not covered by the Amnesty Act as they were indicted by the ICC for their war crimes. Dominic Ongwen is the only one standing trial as he surrendered in January 2015. Kony remains at large (ICC-02/04).

2.2. Children’s Rights in Armed Conflict

Child Soldiers:

The conscription of children under the age of 15 into the armed forces is considered a war crime under international criminal law (RS, 1998, Art. 8 (2) (e) (vii)). It is also part of international humanitarian law which is the rules that govern the conduct of all parties to an armed conflict (AP II, 1977, Art. 4 (3) (c)). As a State Party to the AP II (1977), Uganda is obliged to protect the rights of civilians during an armed conflict. While the children were an active part of the hostilities, they cannot be seen as belligerents due to the forceful nature of their abduction. The prohibition on child soldiers is also part of international human rights law, e.g. Art. 38 of the CRC (1989). While

international humanitarian law is specific to situations of armed conflict, it is widely recognized that international human rights law is applicable in times of armed conflict and peace. Thus, during an armed conflict, the two bodies of public international law complement each other (UN, 2011, HR/PUB/11/01). The recruitment of children under the age of 18 is also prohibited by virtue of Art. 2 of OPAC (2000). Importantly, ACRWR, CRC, and OPAC also refer to the State’s duty to protect the civilians during armed conflict (ACRWC, 1990, Art. 22; CRC, 1989, Art. 38 (4); OPAC, 2000, Art. 4). Others argue that the prohibition can be directly derived from the child’s inherent right to life. Uganda is also a party to various human rights treaties protecting this right including ACHPR (1981) (Art. 4), ACRWC (1990) (Art. 5), CRC (1989) (Art. 6), and ICCPR (1966) (Art. 6).

2.3. The Right to an Effective Remedy

2.3.1. The State Responsibility to Respect, Protect, and Fulfill Human Rights

While individual human beings and, to some extent, groups are rights holders under international human rights law, the State is the primary duty bearer. Hence, it must respect, protect, and fulfill the fundamental rights and freedoms. This entails that the State must not restrict the enjoyment of human rights, must protect the right holder from human rights abuses, and take affirmative action to ensure the full enjoyment of all human rights (UN OHCHR, n.d.). There is also a general obligation under the UN Charter (1945) to promote and respect human rights (Art. 1 (3)). As a State who has voluntarily consented to be bound by the ICCPR (1966) by means of ratification, the GoU must respect and ensure the treaty rights to everyone within its jurisdiction (CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add. 13, 2004, §3). This also entails that a failure to “prevent, punish, investigate or redress the harm” caused by non-state parties can give rise to a breach of the State’s responsibility to protect (ibid., §8). Therefore, the State is responsible for remedying violations of international human rights law that it commits or fails to prevent (UN Basic Principles, 2006, Art. 15). Notably, this is also applicable in situations of armed conflict (CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add. 13, 2004, §15).

2.3.2. The Legal Right to an Effective Remedy

“Ubi jus, ibi remedium” is a Latin legal maxim meaning “where there is a right there is a remedy” (Oxford Reference, n.d.). The right to an effective remedy is also explicitly found in several international human rights treaties to which Uganda is a Party e.g. Art. 2 (3) of the ICCPR (1966). Moreover, it is implied in Art. 39 of the CRC (1989) and Art. 7 (1) (a) and Art. 50 of the ACHPR (1981). The right to reparations for victims of grave breaches of international law can also be found in international criminal law, in particular, Art. 75 of the RS (1998). The UN Basic Principles (2006) are based on the existing legal obligations of the State under international human rights law and international humanitarian law and do not create new duties for States. Thus, they are an affirmation of the State’s obligation to provide an effective remedy under e.g. Art. 2 (3) of the ICCPR (1966). According to Art. 11 of the UN Basic Principles (2006) the right to a remedy entails:

(a) Equal and effective access to justice;

(b) Adequate, effective and prompt reparation for harm suffered; (c) Access to relevant information concerning violations and reparation mechanisms.

Reparations are only one aspect of the right that can take various forms including restitution, compensation, rehabilitation, satisfaction, and guarantees of non-repetition (UN, 2010; UN Basic Principles, 2006, Art. 19-23). Furthermore, it is recognized that a victim-orientated approach must be taken which encourages the State to remedy harms caused by third parties (UN Basic Principles, 2006, Art. 13, 16). While it is widely recognized that the State has a responsibility to remedy breaches of human rights caused by its omission, the UN Basic Principles (2006) provides that the victim’s right to an effective remedy is “irrespective of who may ultimately be the bearer of

responsibility for the violation” (Art. 3 (c)). The UN Secretary-General’s report, “The Rule of Law and Transitional Justice in Conflict and Post-Conflict Societies” (2004), also suggests that the State have a duty to act on behalf of victims which includes providing reparations (S/2004/616, 2004).

The UN General Comments are a guide for the legal obligations of states. The aim is for the relevant treaty body to interpret and elucidate the duties of State Parties (Ask Dag, 2018). As the treaty body to the ICCPR (1966), the UN Human Rights Council has stressed that remedies must consider the vulnerability of children and be proportionate to the harm even in times of emergency (CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.11, 2001; CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.13, 2004). Thus, the right to an effective remedy is non-derogable, which means that it cannot be ignored or suspended by the State. The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights has also affirmed that ACHPR (1981) provides for the right to an effective remedy (2000 AHRLR 149 (ACHPR 2000); 2000 AHRLR 56 (ACHPR 1995)). Lastly, the right to an effective remedy is part of the domestic legislation, e.g. Art 50 of the Constitution of the Republic of Uganda (1995). Yet, it is argued that the majority of victims, whose human rights were violated during the armed conflict in Northern Uganda, have not yet realized their right to an effective remedy (Otim & Kihika, 2015; Sarkin, 2014; UN OHCHR & UHRC, 2011).

2.3.3. Why Does It Matter?

“A right without a remedy is not a legal right; it is merely a hope or a wish” (Ziegler, 1987, p. 678). Rights are important as they define the social relations of citizens in a democracy, but they have little effect if they are not supported by remedies. As rights enhance the individual’s self-respect, justice entails that they must be respected and enforced. When the denial of rights is systematic, conflicts may emerge (Ziegler, 1987). Consequently, democratic governments must work to enforce rights rather than “invent ways to deny them” (ibid., p. 728). According to Sarkin (2014), providing remedies promotes justice. They also have a moral aspect as they show “that harm was done, but

not the amount of suffering or loss that was endured” (Sarkin, 2014, p. 534). It is impossible for reparations to restore a life (Ziegler, 1987). Nonetheless, the principle that rights should have remedies is still important as reparations signify the acknowledgment of the State’s responsibility for the breach of a victim’s fundamental rights. While victims can benefit from e.g. development programs, they do not include any acknowledgment of responsibility or recognition of harms. The policies do not seek justice for victims but are of potential benefit to other individuals too (ASF, 2016; Carrington & Naughton, 2012; UN OHCHR & UHRC, 2011). Reparations are about rights and “requires State and public recognition of the violation of victims’ rights” (UN OHCHR & UHRC, 2011, p. 23). Only then can victims of gross human rights violations obtain justice.

2.4. Domestic Policies and Development Programs

In 2000, the Government passed the Amnesty Act which gives immunity to anyone “engaging in war or armed rebellion” (s. 2(1)). The Amnesty Commission which was set up and had the

responsibility of reintegrating and resettling the returnees (Amnesty Act, 2000, s. 6-8). However, the Commission has been criticized for not taking a gender-sensitive approach to the issue of

reparations as it “makes no special provision for women who returned with children, giving them the same reintegration package as those who returned alone” (Justice and Reconciliation Project, 2015, p. 1). While the success of the Juba Peace Talks (2006-08) can be debated, as Kony refused to sign the peace agreement in the end, it still serves as a reminder of the government’s

responsibility to provide victims with effective remedies. Indeed, the Juba Peace Agreement recognized the need for the GoU to grant remedies to the victims including compensation, restitution, and rehabilitation (UN OHCHR & UHRC, 2011). In 2008, the Transitional Justice Working Group was established under the Justice, Law, and Order Sector (JLOS) as the unit responsible for drafting a national transitional justice policy which shall provide reparations to the victims of the armed conflict. Ten years later, the transitional justice policy is still not in place (Otim & Kihika, 2015).

As reparations seem to be confused with development programs in Northern Uganda, three of the major ones implemented by the GoU will be discussed shortly (Kisembo, 2018; Oywa, 2018).

The Northern Uganda Social Action Fund (NUSAF):

This program aims at improving the socio-economic status of the people in Northern Uganda. It is funded by the World Bank and has three phases, which all have a budget of between 100-133 million USD each (World Bank, 2002; World Bank, 2008; World Bank, 2015). NUSAF I (2003-2009) aimed at enhancing the capacity of vulnerable groups (e.g. ex-abducted) to “systematically identify, prioritize, and plan for their needs and implement sustainable development initiatives” (World Bank, 2002). NUSAF II (2010-2015) aimed at empowering the communities to improve their livelihoods (World Bank, 2008). However, they were both criticized for not reaching the intended beneficiaries due to corruption (ASF, 2016). NUSAF III (2015-2020) builds on the previous initiatives and includes e.g. livelihood investment and institutional development (World Bank, 2015).

The Peace, Recovery, and Development Plan (PRDP):

First launched in 2007, this had a budget of 606 million USD for its first phase (Sarkin, 2014). PRDP I and II focused primarily on the development of infrastructure and resettlement of IDPs in the Northern and Eastern regions. They faced many challenges including reporting issues and insufficient staffs. Most importantly, they have been criticized for high levels of corruption and misuse of public funds, in particular, by the Office of the Prime Minister (ASF, 2016; Dan, 2018; Nyeko, J., 2018; Omony, 2018; Otim & Kihika, 2015). The current program, PRDP III (2015-2020), focus on livelihood assistance and issues of land (ASF, 2016). It is worth noting that the PRDP is funded out of the GoU’s budget and specific project donations from e.g. NUSAF (Institute for War & Peace Reporting, 2012).

The Youth Livelihood Program (YLP):

The YLP is another five-year government program running from 2013-2018. It has a budget of approximately 71.5 million USD and aims at improving the socio-economic status of poor and unemployed youth through skills training and income-generating activities. Another feature that is shared with the previous development programs is corruption (Dispatch, 2018; New Vision, 2017).

3. Theoretical Approach

The theories of recognition will be used to clarify the possibilities and limits of reparations as undertaken in Northern Uganda. The combination of theories of recognition and a conceptual understanding of successful reintegration makes it possible to understand and discuss the post-conflict experiences of formerly abducted children in Gulu. While the theories will be connected to the gathered data in Chapter 5, this section will explain each of the chosen theoretical approaches.

3.1. Reintegration

3.1.1. Definitions

While the concept of reintegration is widely used in academia, there is a tendency to leave it undefined (Amone-P’Olak, 2007; Blattman & Annan, 2008; Cheney, 2005; Harnisch &

Montgomery, 2017; Ochen, 2014; Pham, Vinck & Stover, 2009; Roach, 2013; Vindevogel et al., 2011). Adding to the confusion, many different definitions exist. Nonetheless, the right of the child to “physical and psychological recovery and social reintegration” after e.g. armed conflict is

protected under international human rights law (CRC, 1989, Art. 39). For the purpose of this paper, reintegration is understood to be a long-term societal process that enables the individual to

participate equally in the social, economic, and political life. A similar conceptualization is used in both academia and employed by the International Organization for Migration (IOM, 2015; Nilsson, 2005). While it is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss all definitions, it should be noted that many existing formulations focus on socio-economic factors (Annan et al., 2011; Osborne, D’Exelle & Verschoor, 2018; Veale & Stavrou, 2007).

3.1.2. What Does Successful Reintegration Mean?

Effective reintegration programs are seen as fundamental to securing a sustainable peace and promoting reconciliation (UN, 2016; Veale and Stavrou, 2007). However, successful reintegration is hard to measure (Banholzer & Haer, 2014; Nilsson, 2005). Scholars have often focused on the three aspects of social, economic, and psychological integration as determinants for successful programs (Banholzer & Haer, 2014; Ruben, van Houte & Davids, 2009). Similar criteria are

suggested by the UN Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict who also include gender-sensitivity and long-term funding as components of successful reintegration (UN, 2018). Reintegration is a long-term process which must also encompass continuous follow-up. As argued by Nilsson (2005), the time it takes to achieve

successful reintegration vary according to the ex-combatants and their environments. This paper follows the Paris Principles and Guidelines on Children Associated with Armed Forces or Armed Groups (2007) in asserting that “sustainable reintegration is achieved when the political, legal, economic and social conditions needed for children to maintain life, livelihood and dignity have been secured. This process aims to ensure that children can access their rights” (§2.8, emphasis added).

3.2. Transitional Justice and Theories of Recognition

3.2.1. Transitional Justice and Peacebuilding

Since its emergence in the late 1980s and early 1990s, transitional justice has been the topic of vast research (Buckley-Zistel et al., 2014; ICTJ, 2009; Sharp, 2015). Nonetheless, it is important to keep in mind that “there is not one theory of transitional justice” but several (Buckley-Zistel et al., 2014, p. 4, original emphasis). Traditionally, a move towards a liberal democracy was understood to be an essential feature of transitional justice. However, it is increasingly acknowledged that a

fundamental political change is not a necessary condition. Rather a move from armed conflict to peace, as in the case of Northern Uganda, suffice (Laplante, 2014; Moyo, 2012; Sharp, 2015). This begs the question, what is peace? A negative definition of peace understands it as the lack of direct violence. Contrarily, positive peace also requires social justice and the absence of structural

violence (Hvidsten & Skarstad, 2018). Indeed, Lambourne (2014) follows Galtung in arguing that sustainable peace is intertwined with justice. Transitional justice is increasingly seen as a way of promoting a positive peace (Sharp, 2015). Simultaneously, there is a growing emphasis on

emancipatory peacebuilding (Leonardsson & Rudd, 2015). It is a holistic approach which seeks to build peace from below based on the ‘everyday’ needs of the individual victims and their

communities (Thiessen, 2011). For peace to be sustainable, one must understand the needs and challenges of the different individuals in a particular post-conflict setting. If the lived realities are ignored, tensions may persist (Sharp, 2015).

Transitional justice is a post-conflict response to violations of human rights. It is generally understood to consist of “both judicial and non-judicial mechanisms, […] [including] prosecution initiatives, reparations, truth-seeking, institutional reform, […] or a combination thereof”

(S/2004/616, 2004, §8). While transitional justice must consist of several of these measures to effectively address the root causes of conflict, it is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss all of them (ICTJ, 2009; Verdeja, 2006). Therefore, this paper will focus solely on reparations as the

victims’ right to a remedy are an essential part of international human rights law which have also framed transitional justice efforts (UN, 2014, HR/PUB/13/5).

3.2.2. Recognition as Transitional Justice

Reparations are a part of both transitional justice and international human rights law. Ultimately, they are about recognition as reparations both seek to satisfy the individual’s rights claim and offer recognition and reconciliation (Brett & Malagon, 2013; Moyo, 2012). Reparations indicate that the state recognizes the dignity, equality, and moral worth of the victims (Verdeja, 2006). The

recognition of victims as rights-bearers is a necessary condition for sustainable transitions from conflict as the lack thereof can limit the ability of citizens to engage in society as equals (Eisikovits, 2017; Verdeja, 2006). Thus, human rights must be at the core of any transitional justice measure. Reparations serve as a “rights enforcement” and a recognition of the State’s responsibility to respect or protect the individual’s fundamental rights (Laplante, 2014, p. 75). Haldemann (2008) argues that transitional justice must provide recognition to victims especially where the state has permitted “a large-scale violation of its own citizens' rights to life and liberty” (p. 714). It is a matter of transitional justice as misrecognition may occur when the State does not respond to the harms suffered during the armed conflict. Misrecognition is “a specific attitude of treating others as inferior […] or simply invisible” (ibid., p. 693). A state who has failed to protect its citizens from widespread violations of their rights can offer collective recognition in the form of e.g. truth-telling and reparations (ibid.).

Haldemann’s concept of justice as recognition is a victim-centered approach, which he defines as “the kind of justice that is involved in giving due recognition to the pain and humiliation experienced by victims of collective violence” (Haldemann, 2008, p. 678). He argues that every breach of a person’s fundamental right involves a symbolic devaluation of him or her. Therefore, it is imperative to focus on the victim’s own lived experiences of injustice as “due recognition is something we owe to the victims” (ibid., p. 693). Laplante agrees that reparation programs must be guided by a sensitivity to the individuality of victims. Thus, victims must be actively involved to ensure that reparation programs accommodate their needs (Laplante, 2014).

3.2.3. The Importance of Mutual Recognition

According to Taylor (1992), “due recognition is not just a courtesy we owe people. It is a vital human need” (p. 26). Honneth (1995) offers an extensive critical theory of recognition elaborating

on the importance of mutual recognition for the individual and society as a whole. He also argues that recognition is central to the well-being of the individual. Following his interpretation of Mead’s theory of intersubjective recognition, self-realization depends on others as the individual only discovers his or her own abilities through the recognition and reactions of others (ibid.). Norms are internalized through this development, which enables the subject to know his or her rights and obligations (Presbey, 2003). Therefore, the individual’s autonomy and identity are dependent on the development of self-confidence, self-respect, and self-esteem, which are all maintained through the relationships of mutual recognition (Honneth, 1995).

Honneth’s Theory of Recognition: Love:

The first stage of mutual recognition, love, is important as it is the first experience of recognition. According to Hegel, it is the stage where individuals confirm and recognize their neediness and dependency on each other. It is an affective form of recognition between two individuals that depends upon confirmation, reciprocity, and encouragement (ibid.). “If love is provided, one develops self-confidence […] because one is certain of one’s unique value to the other” (Presbey, 2003, p. 543). However, if the individual is subjected to physical or psychological abuse, it can lead to lasting damage to his or her basic self-confidence and even a “loss of trust in oneself and the world” (Honneth, 1995, p. 133).

Respect:

Individuals realize their obligations towards other subjects and become aware of their own rights through the process of mutual recognition as “one can have rights only if one is socially recognized as a member of the community” (Presbey, 2003, pp. 543-44). Moreover, rights enable a person to develop self-respect. This is due to the fact that the individual becomes aware of the respect that he or she deserves from other community members (Honneth, 1995). At the personal level, the mutual recognition of each other as legal persons, therefore, permits the subject to develop a positive self-image. Rights are an expression of autonomy (Presbey, 2003). Human rights entail that all human beings are equal and deserves the same respect and protection. However, these liberties depend on mutual recognition of each other’s capacity to exercise one’s personal autonomy (Honneth, 1995). The denial or exclusion of rights can diminish the individual’s self-respect and social integrity (Presbey, 2003). It implies that the person is not viewed as having the same level of autonomy as

others. As a result of this disrespect, he or she does no longer feel like a legal person with equal standing in society (Honneth, 1995).

Esteem:

After the equality of rights is realized, it is possible to develop self-esteem through the recognition of an individual or a group’s unique traits (Presbey, 2003). Thus, this third category of recognition is dependent upon the others (Honneth, 1995).

The Struggle for Recognition:

Honneth conceives struggles for recognition as “movements for justice […] motivated by individuals’ and groups’ felt need for recognition” (Presbey, 2003, p. 537). The dependency on others for the development of one’s identity through love, respect, and esteem is what makes the individual vulnerable to recognition. Social struggles can emerge when a person does not feel duly recognized (Honneth, 1995; Presbey, 2003). Honneth stresses that the struggles for recognition must be distinguished from conflicts based on collective interests. The latter is based on the wish to strengthen control over scarce resources, while the former is based on the feeling of unjust

treatment (Honneth, 1995, p. 165). Notably, recognition is not static and the struggle for recognition is a phenomenon that, in principle, can be overcome (ibid.). Furthermore, only the recognition associated with rights and social esteem can give rise to struggles for recognition as these “personal experiences of disrespect can be interpreted and represented as something that can potentially affect other subjects” (ibid., p. 162). An example would be the denial of the right to adoption for a

homosexual couple. Arguably, this can affect e.g. other same-sex couples (Honneth, 1995). Economic expectations can also, to a certain extent, set off social struggles as the “people feel that they have been denied social recognition and worth” (Presbey, 2003, p. 549). Therefore, Fanon suggests that increasing educational opportunities is a concrete example of recognition (ibid.). While struggles for recognition has the potential to develop society, Honneth (1995) points out that the success of social movements is also dependent on the cultural and political environment.

3.2.4. Justice as Recognition and Redistribution

Fraser has questioned the validity of Honneth’s theory of recognition, in particular, his claim that recognition is the basis of each individual’s well-being. She argues that “justice today requires both redistribution and recognition; neither alone is sufficient” (Fraser, 2001, p. 22, original emphasis).

Fraser (2001) bases her own theory of recognition and redistribution on the notion of ‘parity of participation’, which she defines as the “social arrangements that permit all (adult) members of society to interact with one another as peers” (p. 29). First, the objective condition must be satisfied which requires redistribution of material resources. Secondly, the intersubjective condition entails equal respect and opportunity for all individuals (ibid.). However, as Presbey (2003) points out the disagreement between Fraser and Honneth is small as they both view redistribution and recognition as important dimensions which should not be overlooked. Fraser acknowledges that redistribution and recognition are intertwined in reality, but she maintains that they are distinct aspects of justice. She contends that Honneth risks ignoring material inequalities (Fraser, 2001). On the other hand, Honneth argues that economic redistribution can be provided for under symbolic recognition (Honneth, 1995).

Verdeja (2006) follows Fraser in viewing redistribution and recognition as a matter of justice. To him, reparation programs must aim “to restore the victims’ dignity and self-worth in such a way that allows them to be full participants in social, economic, and political life” (ibid., p. 454). As many survivors find themselves in poor economic conditions after armed conflict and their well-being is dependent on reciprocal recognition, he proposes a dualistic model of reparations. His model, which is supported by Haldemann (2008), aims at providing victims with collective,

individual, material, and symbolic reparations (Verdeja, 2006). He agrees with Honneth on the importance of symbolic recognition for the development of dignity and self-respect. Collective symbolic reparations such as public apologies or official monuments reflect the State’s recognition of the victims’ experiences and their right to be treated as equals. As suffering is always personal, “individual symbolic recognition emphasizes the importance of remembering that victims are not merely a statistic but actual people who often suffered intolerable cruelties” (Verdeja, 2006, p. 456). Arguably, in practice, there are often a large number of victims after an armed conflict. Yet, if the individual victims are not recognized as equals, it is questionable whether their status as citizens with equal rights can be secured at all. Verdeja (2006) also claim that economic inequality cannot be remedied by means of symbolic recognition. Thus, there is a need for collective material

reparations, which seek to improve the victims’ livelihood. However, it should be noted that “what the state may call reparations for victims may be viewed as part of the state’s duties to all citizens” (ibid., p. 457). On the other hand, the provision of individual material reparations, e.g.

compensation, respect the autonomy of victims as it allows each person to independently identify and fulfill his or her needs (ibid.). It should be remembered that compensation might be worth little

without acknowledgment of harm, whereas apologies can be seen as meaningless without any material reparations (Haldemann, 2008). For that reason, this paper will use a combination of Verdeja’s dualistic model and Honneth’s theory of mutual recognition to analyze the reintegration experiences of former abductees in Uganda.

4. Method

The minor field research took place in Gulu district in Northern Uganda from 16th of April to 15th of June, 2018. While many of the interviews were conducted in the local community, others took place in an office. The main methodology used was semi-structured interviews with former abductees and professionals working in different NGOs, community leaders, and state officials.

4.1. Semi-Structured Interviews

Considering that I wanted to study the personal experiences of former abductees, I choose to do a qualitative study based on interviews as it yielded the possibility of getting an insight into the individual respondent’s thoughts and feelings. Semi-structured interviews were advantageous in this regard as they are flexible and allows for a two-way communication, where the researcher can “rephrase questions, and make changes according to the interview situation” (Gelletta, 2012, p. 75). Moreover, the accuracy of the obtained data is increased by employing this method as the

researcher may ask for clarification and elaborations to gain additional insight (ibid.). Thus, it allowed the participants, in their own voices and within their own context, to describe the impact that the armed conflict has had or continues to have on their lives. Phenomenologists argue that researchers must study several individuals who have experienced a certain phenomenon in order to discover the essence of their experience. Only then can a researcher move from the individual experience to a description of universal importance (Creswell, 2006).

It might be argued that qualitative data derived from interviews can be difficult to quantify and compare, but Luker (2010) contends that the point of interviews is that they are “narratives” and as such an account of the individual’s perception of the social world (p. 167). Moreover, face-to-face interviews also allow the researcher to study e.g. the body language of the interviewee. The former abductees who were interviewed for this study tended to avoid eye contact or fumble with something while talking due to the sensitivity of the topic. However, they insisted on continuing even if it became hard. A disadvantage is that the outcome of the interview might be affected by power structures and social inequalities. As pointed out by Hammersley and Gomm (2008): “what people say in an interview will indeed be shaped, to some degree […] by the

conventions about what can be spoken about” (p. 100). Thus, taboo and social stigma might impact the answers. Nonetheless, interviews do yield the possibility of uncovering information that might not have been possible to obtain from using e.g. questionnaires where interviewees have to fit their experiences into the limited options provided by the researcher. As noted by Luker (2010), it should

be remembered that researchers themselves are also “socially located individuals” with potential biases as they are attached to the social world (p. 59). As a Western researcher, I cannot reject entering the field with a certain understanding of the world. I choose to maintain a Western conceptualization of childhood although it might not reflect the local customs (Annan, Brier & Aryemo, 2009). This approach still seemed reasonable since a child is defined as below 18 in various international treaties and domestic laws and I wanted to investigate the tension between Uganda’s legal obligations and the experiences of former abductees. However, it does also reflect my own position of power as none of the local partners or interviewees were consulted.

4.1.1. Primary Target Group

Purposive sampling was used as all interviewees were recruited on the basis of their rich knowledge of the reintegration of former abductees or their personal experience. The formerly abducted

children were targeted as they are the actual people whose fundamental rights were violated when they were abducted and used as child soldiers by the LRA. They are crucial to this research as they provide first-hand information as to the perceived effectiveness of the current remedies. They also give much-needed information about the opportunities and obstacles to reintegration in Gulu. Arguably, they are in the best position to give an insight into how the provision or lack of

reparations in Uganda impact their lives. The inclusion criteria for participation was to have been abducted as a child from Gulu district (as defined by the time of the armed conflict2) and being an adult at the time of the interview (i.e. above 18 years old). Thus, five additional interviews were left out because the interviewees did not fulfill the first criteria. Moreover, a gender balance was

actively sought. A presentation of the characteristics of each former abductee who was interviewed can be found in Appendix 1.

4.1.2. Secondary Target Group

Purposive sampling was also used in the selection of the other interviewees, which included a state official, community leaders, and professionals working in local NGOs. Moreover, three of the interviewees were engaged in the Juba Peace Talks (2006-08) as a coordinator or an active

participant (Bishop Ochola, 2018; Nyeko, J., 2018; Oywa, 2018). The reasoning behind including them in this study was to get a greater understanding of the needs and challenges that former abductees face. As these respondents all had rich knowledge on the topic due to their work

experience, these interviews were used as a way of complementing and affirming the ones

conducted with the primary sources (i.e. the former abductees). Hence, they were used as a way of enriching the data and increasing the validity of the findings. Each of the respondents is presented in Appendix 1.

4.1.3. Sampling and Data Collection

Interviewees were recruited through my local contacts, Mr. Godfrey Canwat and Mrs. Rosalba Oywa. Mrs. Oywa, the founder of People’s Voices for Peace, enabled me to do most of the interviews with the FACs as she introduced me to two organizations, which are run by former abductees and other community members. The trust and support of Youth Leaders for Restoration and Development (YOLRED) and War Victim Children Networking were indispensable for the study as some of the former abductees were reluctant to engage in the research at first because Gulu has been a setting for many previous studies with little benefit reaching the interviewees. I have tried to address this concern by informing all interviewees of the potential risks and benefits and ensuring that the results and a translated summary are available to all interviewees.

Most of the interviews with FACs were conducted in the local community with the support of War Victim Children Networking. Thus, six of the interviews took place in the private homes of the interviewees while one was set in a church in Gulu district. The choice of location was based on the preference of the interviewees and an ethical consideration of the risks associated with

interviews in a public setting. Yet, the interviews in Lukodi took place in a communal space upon the request of the returnees and the local district council. Lukodi is a village in Gulu district which suffered from numerous attacks by the LRA and a massacre where 60 people were killed. It is also of interest as Dominic Ongwen is currently being tried at the International Criminal Court for his role in this massacre of May 19, 2004 (ICC, 2016). These interviews were made possible through the support of YOLRED. The remaining interviews took place in the offices of the interviewees or at Gulu War Affected Training Center. The majority of the contact with the other respondents (e.g. community leaders) was made through Mr. Godfrey Canwat, the Director of Hope and Peace for Humanity, Uganda.

4.1.4. Delimitations

As the official language is English, I was able to conduct the majority of the interviews without a translator. However, given that the majority of former abductees have lost years of education, a

local translator was available for all of these interviews. Some of the former abductees only spoke the local language, Luo, while others felt more comfortable in it as they were able to express themselves more freely than in English. There is, of course, a risk that this process of translation will lead to a loss of information or make it difficult to build up trust. At times, it was harder to ask follow-up questions due to the language barrier as e.g. one of the translators tended to summarize rather than interpret word by word. There is a risk that the own words of the former abductee got lost due to the language barrier. Moreover, four different translators were used. While this might seem odd, the main reason behind this choice was to ensure the confidentiality of the interviewees. As the former abductees preferred a translator internal to the organization, their wishes were respected. Thus, several translators were used in this study as the former abductees were

interviewed in collaboration with different local organizations. When external translators are not used, there is always a risk that the translator or interviewee will modify the answers to ask for support. However, it was stressed prior to the study that there would not be any direct benefits or incentives for participation. An advantage of using translators who knew the interviewees was that they already trusted him or her and were more open. Moreover, the translator was extra aware of any personal signs of distress. It should also be noted that interviews are always driven by theory. Thus, it “dictates where we will start interviewing, what we will ask, and when we will decide to come out of the field” (Luker, 2010, p. 180). Arguably, it is limited to what extent the findings can be generalized. One of the reasons is that most of the former abductees who were interviewed are part of the same group. Hence, 8 out of 14 are connected to the War Victim Children Networking, while the rest are associated with HPH or YOLRED. But due to limited time and resources, “we have to sample, whether we like it or not” (ibid., p. 101).

4.2. Ethics

A sensitive research approach should be taken when interviewing former abductees. It is crucial to avoid re-traumatization of the interviewees by exposing them to questions they are uncomfortable with (Melville & Hincks, 2016). The choice of method is partly based on an ethical concern as semi-structured interviews are more appropriate for investigating sensitive topics since they allow the researcher to skip questions or stop the interview at any time. The inclusion criteria for the former abductees was also due to ethical concerns as I am a student researcher with no experience in interviewing trauma victims. It is also one of the reasons why my questions focus more on the aftermath and reintegration of former abductees. Thus, it is up to the interviewee if he or she wants

to share what happened during the period of abduction. The option to do so was left open due to the importance of giving the individuals the chance to share what they deem important. While this field research was conducted for academic purposes what it includes is the very personal accounts of extremely traumatic events. Therefore, I found it important to present the voices of these victims.

Informed and voluntary consent is vital. Before agreeing to participate in the study, the interviewees were informed, in a language that they understood, that their participation was completely voluntary and that the interview could be paused or terminated at any point. Moreover, they were informed of the purpose of the study and of the arrangements to protect and conceal their identities, e.g. the numbering of interviews or use of other indicators such as age and gender. An informed consent form for qualitative studies has been retrieved from the World Health

Organization’s Research Ethics Review Committee (ERC) and adapted to fit the different types of interviews (WHO, n.d.; see Appendix 2). They have also been reviewed by the Director of Hope and Peace for Humanity, Mr. Godfrey Canwat. For the former abductees, the informed consent form was not translated to Luo but it was discussed with them prior to the interview. Then,

voluntary consent was given either orally or in writing. This choice was based on the awareness of the illiteracy of many former abductees due to the loss of education. Lastly, pseudonyms were granted to those that wished to be anonymous and it serves as their security. Still, all participants have been informed of the potential risks and benefits of the study prior to giving consent.

5. Analysis

As the aim of this paper is to discuss whether the provision of remedies aid or hinder the reintegration of former abductees in Gulu, their personal experiences of return will be analyzed using theories of recognition. The research findings will be presented in the following order: Material Reparations in Northern Uganda, Symbolic Reparations and the Lack of Recognition, and Suggestions for Successful Reintegration. This division is based on Verdeja’s dualistic model of reparations as it is acknowledged that successful reintegration is dependent on mutual recognition and equal distribution of resources. It is also based on the theory of emancipatory peacebuilding and justice as recognition, which are two distinct approaches that both stress the individuality of victims of human rights violations. Therefore, the former abductees’ own suggestions for reparations that can enable their successful reintegration are included. Additionally, Honneth’s theory of social struggles for recognition will be used in the analysis of symbolic reparations.

5.1. Material Reparations in Northern Uganda

5.1.1. Individual Material Reparations

Few, if any, individual material reparations have been provided by the GoU. The State has granted all ex-combatants monetary support through the Amnesty Commission. According to the

interviewees, it consisted of approximately 200-260,000 UGX which is equivalent to 54 – 70 USD. It was a flat rate with no extra support to the child mothers who returned with as many as four children (Catherine, 2018; Emily, 2018; Grace, 2018; Lanam, 2018). While the provision of individual monetary reparations respects the autonomy of the victim to utilize the money as he or she best sees fit, only two of the former abductees found that it aided their economic reintegration as they used it to start their businesses (Dan, 2018; Grace, 2018; Verdeja, 2006). Meanwhile, the provision of this support was fraught with challenges. First of all, it was not equally accessible to all as illustrated by the fact that only eight of the interviewed returnees received it along with some additional material support e.g. a mattress, blanket, saucepans, or food. Yet, none received the same amount of material support nor were any one of them consulted in the process. Secondly, the

Amnesty Commission ran out of money and did not fulfill its mandate of “resettlement, reintegration, and rehabilitation of war victims” (Angwech, 2018). Thirdly, some of the

interviewees suggested that the Amnesty certificate and the material support was not obtained by many returnees as they feared to report to the authorities (Angwech, 2018; Lanam, 2018; Lokwiya, 2018; Omony, 2018; Oywa, 2018).

Moreover, its value has been questioned by the former abductees, e.g. Catherine (2018): “We came out and they said, ‘you have the amnesty’. We do not know at the time, what is amnesty?” As pointed out by Haldemann (2008), material or monetary reparations, such as the one provided by the Amnesty Commission, has little value when it is not combined with an official acknowledgment of the harm suffered. It should be noted that the Amnesty Act (2000) gave immunity to everyone engaged in the armed conflict against the GoU (s. 2(1)). Thus, it did not include any recognition of the violation of the child’s fundamental rights. As described earlier, the right to not be a part of the hostilities is included in various human rights treaties to which Uganda is a Party. Arguably, the support from the Amnesty Commission cannot be described as a legal remedy since there is no acknowledgment of the GoU’s failure to protect the child from abduction. As pointed out previously, reparations are about rights and they must entail recognition of the violation and its harms (Laplante, 2014; UN OHCHR & UHRC, 2011; Verdeja, 2006). Yet, it is interesting to note that the returnees’ views on the amnesty differ as illustrated in the opinions of LanamStella Angel and Omony Geoffrey:

Amnesty is supposed to be for the person who goes and fight, but not a child who they just come and take and ruin the life of in the bush (Lanam, 2018).

Amnesty is one of the greatest things that the government gave the returnees. To give them that pardon that they should be welcomed and allowed in the community (Omony, 2018).

Notably, the non-state actors played a big role when it comes to providing material support to the former abductees (Kisembo, 2018). Nearly, all of the interviewees explained that most of the material support was given to them by non-state actors rather than the GoU.

5.1.2. Collective Material Reparations

As pointed out by Verdeja (2006), collective material reparations might take the form of development programs including health initiatives, education, and livelihood assistance.

Physical health and psychological support:

Although all of the respondents received counseling and medical care upon their return, none of them received this kind of support from the State. Importantly, the right to the highest attainable (physical and mental) health is guaranteed by various human rights treaties which Uganda is a Party to (ACRWC, 1990, Art. 14; UN ICESCR, 1966, Art. 12). The two returnees who self-integrated received medical and psychological support from their families and friends (Lena, 2018; Sophia, 2018). Meanwhile, all of the formerly abducted children who went through a reception center