REVITALISING URBAN SPACE,

AN ANT-BASED ANALYSIS OF THE

FUNCTIONING OF THREE REDESIGNED

PUBLIC SPACES IN ROSENGÅRD

Fatemeh Hamidi Urban Studies

Master's (Two-Year) Thesis Supervisor: Jonas Alwall Autumn semester of 2019

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank my supervisor, Jonas Alwall, for his valuable guidance, intellectual generosity and consistent support throughout my work on this thesis. A special thanks to Jakob Schyberg and Susanne Strand Gustafsson for their great support and encouragement during my studies.

I would like to thank my wonderful family for being always supportive throughout my life and my studies.

A heartfelt thank you goes to the people of Rosengård who with their participation in the interview and co-operation in providing information helped me to realise this project.

Summary

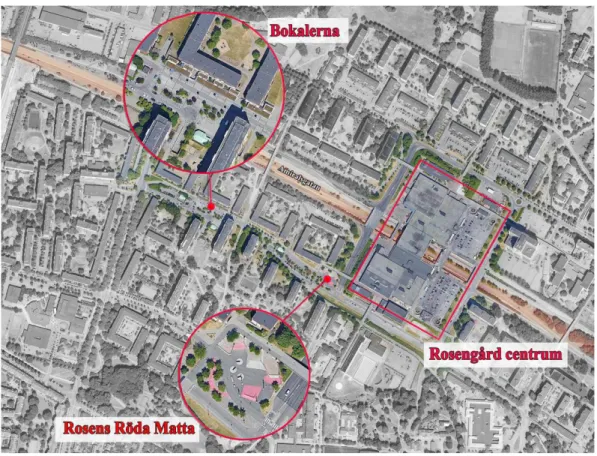

Public space functions are essential for society to function because they can support social exchanges and building public life. This master thesis is a study of public life that unfolds in the setting of three redesigned public spaces in Rosengård, including Bokalerna, Rosens Röda Matta, and Rosengård Centrum. Drawing on a conceptual toolbox developed from a territorial actor-network theory (ANT) I examine the socio-material exchanges that take place because of the redesigned materialities of space and explore their impact on the quality of the selected public places. I employ qualitative methods - visual ethnography and interviews - to address the questions of 1) how material topographies mediate social exchange and 2) What actors or events are important for assembling everyday sociality in the selected three public spaces.

I made use of six operative concepts of anchors, base camps, multicore and monocore spaces, tickets and rides, ladders, and finally punctiform, linear and field seating to explore their impact on the quality of the selected public places in terms of affording or hindering social exchanges. My field observations of the three sites and interviews indicate that the Rosengård Centrum accommodate a more pronounced public life compared the other, and perhaps the most popular one in the district. The programmed materialities and multiple points of organised activities allow space to facilitate heterogeneous clusterings of humans and non-human entities and the formation of a diverse collective. Moreover, the organization of a mixture of monocore and multicore space in combination with sheltered anchor spots appears to be essential for assembling and stabilising human collectives and everyday sociality in Rosengård.

My findings suggest that, while many of the discussions in the literature concentrate on centres of cities or large metropolitan areas, much could still be learned from a thorough study of public spaces at a finer scale and neighbourhood level.

Contents

1. Introduction ... 4

1.1. Research Aim and Questions ... 6

1.2. Previous Research ... 7

Public Space and Designing Sociality ... 7

Everyday Multiculturalism ... 9 1.3. Thesis outline ... 11 2. Theoretical Framework ... 12 2.1. Actor-Network Theory ... 12 2.2. Territoriality ... 15 2.3. Conceptual Toolbox ... 17

3. Presentation of Object of Study ... 21

3.1. Rosengård centrum ... 24

3.2. Bokalerna ... 26

3.3. Rosens röda matta ... 27

4. Methodology ... 29

4.1. Methods ... 29

4.2. Materials ... 31

4.3. Limitations ... 31

5. Analysis and Discussion ... 32

5.1 Rosengård Centrum ... 32

5.2. Bokalerna ... 39

5.3. Rosens Röda Matta ... 46

6. Discussion and Conclusions ... 49

7. References ... 50

1. INTRODUCTION

Malmö, Sweden’s third-largest city, is among the most multicultural in the country and nurtures the ambition to grow as a sustainable and attractive city (Anderson, 2014). Recent innovative construction projects in Västra Hamnen (Western Harbor) and Hyllie are the prominent examples of the strong emphasis that the city authorities and planners put on sustainable planning and development. Malmö, in the transition from a manufacturing hub into a hub for sustainable knowledge, faces the challenge of creating a socially sustainable and balanced city (Petersson & Tyler, 2008). However, in recent decades segregation with socioeconomic and ethnic dimensions has increased among the residents, and distinct patterns of residential segregation has emerged across the city (Anderson, 2014; Andersson & Hedman, 2016). In particular, in order to improve the living conditions for all citizens, the transformation of deprived areas such as the Rosengård district has proven challenging (Anderson, 2014).

Despite its geographical proximity to the centre of Malmö, Rosengård is perceived as a peripheral neighbourhood. This is partly due to the three busy roads - Amiralsgatan, Jagersrovagen, and Vastra Kattarpsvagen – which form physical and symbolic barriers and cut the districts from the rest of the city. Moreover, Rosegård, similar to other "Million Homes Program" –Miljonprogrammet- (Hall & Vidén, 2005) areas across Sweden, is associated with social problems and low quality built environment which has reinforced its image as a socially isolated and segregated area of Malmö (Borgegård & Kemeny, 2004; Grundström & Molina, 2016; Listerborn et al., 2014).

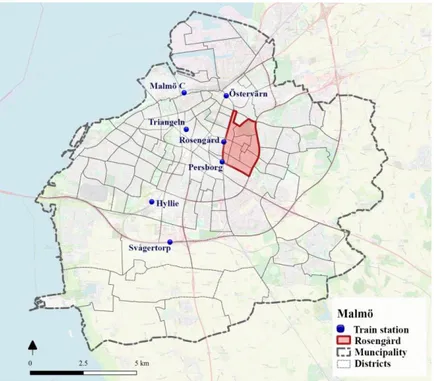

Figure 1- Rosengårds location in the city of Malmö, Sweden

Rosengård was built in 1960-1970, and its development under the million homes program was driven by the industrialisation of the city and the increased demand for accommodation of the industry workers at that time (Borgegård & Kemeny,

2004). Influenced by the ideas of modernism, and in particular Le Corbusier's ideal of housing, the area features high-rise and mono-use buildings with in-between large green spaces and wide roads designed for cars (Grundström & Molina, 2016). The buildings commonly have a simple facade, which at the time was considered modern and attractive. However, the area has experienced a decline as the industry workers moved out and lower-income groups began to move in (Andersson et al., 2010). Parker and Madureira (2016) associate this loss of popularity with the limited range of housing options available in the areas and that they are not living up to their extended needs.

Similarly, Andersen (2016) argues that different types of housing attract and enables different social groups, and asserts that there is a strong link between the uneven distribution of housing tenures and urban segregation. In other words, as a neighbourhood starts to be perceived as poor, the rest of the more economically stable inhabitants start to move out and distance themselves from the area (Andersen et al., 2016). Among the different activities and functions offered in a neighbourhood, public space plays a significant role in the quality of life of the residents because it is the place that integrates their political, economic, social and cultural activities (Madanipour et al., 2014). Public spaces are essential for urban areas to work and the nature and character of public spaces have been closely associated with the nature and character of cities as a whole (Madanipour, 2013). However, the public spaces of the Million Program areas have become a Swedish problem which originates from the architectural design and symbolic role of public institutions and services being downplayed in the Million Program areas (Kärrholm & Wirdelöv, 2019). Similarly in Rosengård, inspired by the principles of modernist industrial construction, the public spaces surrounding the residential buildings mostly include large green spaces that are perceived unsafe and lacking meeting places to attract diverse population groups or accommodate collective activities. The poor quality of the urban environment in Rosengård and issues such as technical defects and the flaws in the design of outdoor spaces have also been linked to the social problems and the segregation of Rosengård. The findings of previous studies on the social impacts of public spaces point out such links in other urban contexts. Neal et al. (2017) provide evidence that depending on the quality of public spaces, people would develop strong attachments to and emotional affection for such places in their living area and also such attachments could go beyond short-term temporal scale to generations or the neighbourhood level spatial level to the city level.

Rosengård's reputation was severely damaged by the increase in unemployment and crime, and it has been stigmatized in the national and international media. Dikeç (2017) views Rosengård as a symbol of the government's failure to achieve equality among different ethnic or economic population groups. While much of this negative symbolisation of Rosengård is due to media narratives disconnected from the reality of life in the district (Ristilammi, 1994), the city authorities have become increasingly occupied with transforming the area into an attractive and well-integrated neighbourhood. In this context, improving the identity and perception of the area to invite newcomers as well as enhancing current residents’ sense of attachment to the area and development of attractive public spaces have become an important goal for a large transformation process called “Rosengård in transition” initiated by the city authorities from 2010 to 2014 (Malmö stad, 2016). The transformation process included several interventions in terms of both symbolic and substantial physical developments of the neighbourhood to align it

with the city of Malmö's sustainability vision (Parker & Madureira, 2016). As strongly emphasised in the Comprehensive plan of Malmö, the recognition of the physical environment as a basis for social interactions and a fundamental prerequisite for the city's social life also motivates the investments (Malmö stad, 2018). Creating attractive public spaces that welcome all, enable human contact to increase and improve social spaces in Malmö and in turn stimulates democracy and inclusion, are highlighted as the planning objectives of the Comprehensive plan of Malmö (Malmö Stad, 2018). Ruiz-Tagle (2013) supports this idea and states that “the treatment of segregation should not be focused merely in terms of location but in terms of more complex sociology of place that includes human interactions and collective constructions” (Ruiz-Tagle, 2013). Moreover, Andersen (2008) highlights the links between the physical and social environment in urban areas and maintains that stronger identification and social bonds in the living environment stop residents from moving away and abandoning their neighbourhood (Andersen, 2008). For similar reasons, public spaces, and in particular meeting points, have been subject to redesign in order to create attractive spaces that harbour positive social interactions among the locals and also invite the rest of Malmö to visit the area (Chambaudy & Jing, 2014; Shotckaia et al., 2017).

The interventions aim to not only to blend the different functions -which were separated under the million homes program- and create a mixed-use neighbourhood with a more sustainable character, but also aim to reduce the mental distance between Rosengård and the rest of Malmö. Three of the latest redesigned areas in Rosengård include Bokalerna, Rosens röda matta, and Rosengård Centrum. It is relevant to examine the outcomes of such interventions and build a more comprehensive understanding of the functioning of the public spaces as well as the actors and forces that shape the social life and the challenge of segregation in an area such as Rosengård.

1.1. Research Aim and Questions

While Rosengård, characterized as a rundown neighbourhood, is home to less than 10% of Malmö’s inhabitants, the low quality of social life in this area not only affects the group who live there but also has implications for the society as a whole (Watson & Kessler, 2013). The recent urban interventions in Rosengård involving the redesign of three public spaces aimed to address the issues of poor design, lack of social functions and increased social problems which have been linked with the socio-special segregation of the district. In this context, this research project aims to examine how the physical changes implemented under the “Rosengård in transition” project can shape, condition and facilitate social public life in the three selected sites.

The research builds on previous research about the significance of the physical design of urban public spaces for enabling or hindering social interactions, and it seeks to provide deeper insights on how urban design could play a role in addressing socio-spatial segregation. Drawing on the actor-network theory (ANT), territoriality and the conceptual tools introduced by Magnusson (2016), the study explores the socio-material exchanges in public spaces and the ways that such exchanges may shape social interactions. This research project more specifically is an investigation of what actors (human and nonhuman) are important factors in facilitating human interactions in three public spaces including Bokalerna, Rosens

röda matta, and Rosengård Centrum. Since these sites are the three of the recently redesigned public spaces in Rosengård, it is fitting to examine the functioning and the outcomes of the investments.

The research questions guiding this study are:

1. How material topographies of Bokalerna, Rosens röda matta, and Rosengård Centrum mediate human interactions and social exchange?

2. What actors or events are important for assembling and stabilisation of human collectives and everyday sociality in the selected three public spaces in

Rosengård?

The study attempts to contribute to a deeper understanding of the impacts of physical design on public life and in general, the factors or actors shaping social life in the setting of public spaces and support approaches addressing the social challenges through planning and urban design. The results are expected to be of importance to the City of Malmö by providing references or evidence to inform future planning and design considerations.

1.2. Previous Research

Public Space and Designing Sociality

Public space is an integral part of urban structures that mirrors the complexities of our societies (Madanipour, 2013). Public spaces are recognized as an important part of the strategies for urban transformation and community revitalisation because of their significant role in shaping the image of an urban area and public trust (Carmona, 2015; Madanipour et al., 2014). Carmona (2015) states that while due to privatisation, commercialisation, homogenisation and exclusion taking place under the neoliberal urban plans, public spaces are associated with “decline” and reduced “publicness”, the same remarks as renewal and the return of a public spaces paradigm. However, there seems to be little consensus on the definition of public space and often it has been described as "open space" (Tonnelat, 2004).

While some urban scholars define public space as the spaces between buildings together with the objects and artefacts in them as well as the building features that imply some physical boundaries of the spaces (Mehta, 2014), others such as Staeheli & Mitchell (2007) recognise public space as the physical setting and sites for negotiation, contest or demonstration, and social meetings. Latham & Layton (2019) refer to public space as the social infrastructure of our cities and maintain that the design, maintenance, distribution, and qualities directly affects their function. For Gehl & Svarre (2013), what public space studies entail, is studying public life and its relation to the physical environment in the process of urban design and planning. What is common in many definitions is that public space are key places for meetings (between strangers) and also that sociability and formation of the public culture are recognized as important roles that such space takes in urban setting (Amin, 2008; Carmona, 2015; Gehl & Svarre, 2013; Latham & Layton, 2019; Madanipour, 2013; Madanipour et al., 2014; Tonnelat, 2004).

As public spaces are physically constructed through a process of planning and design, the literature has studied these spaces in regards to both physical and procedural aspects. There has been a growing interest and awareness among planner scholars and architects regarding the role of urban design in improving public space in declined areas. However, planning and design practice seem to be disconnected from the theoretical and empirical knowledge development. While Durning et al. (2010) links the absence of application in practice to the lack of urban design knowledge and skills among local authorities and the actors who are in charge of the actual work of redesign, Carmona (2010) suggest that integrated and collaborative approaches that could cross the traditional professional and departmental boundaries could bridge this gap. Watson & Kessler (2013) provide empirical evidence that design-driven approaches could produce positive outcomes in practice. In a study of the renewal of parks and other public places in declined areas of London, they took a more comprehensive approach and observed the processes and resources required to realize the renewal, the usage of the areas before and after the changes, as well as the impacts on the perceived safety and the quality of life in such areas (Watson&Kessler, 2013). Their findings support that the physical changes under an urban design-led approach could lead to improvements in both the usage and the perceived safety of such spaces, as well as reducing crime and health-related problems which were in turn linked to positive contributions to the people’s well-being and their perception of the locations. However, what is less studied are the negative effects, e.g. conflicts that may arise from such redesign and changes – mostly the positive effects have been recorded.

When it comes to evaluation of public spaces, the literature on urban design and open spaces is also less consistent on what good public spaces would entail or what qualities make public spaces successful (Carmona, 2010). Nevertheless, three groups of studies have been dealing with such questions. The first group focus on the aesthetic properties of open spaces (Cullen, 1971), while the second group examines the perceived and experiential aspects (Coleman, Brown, Cottle, Marshall & Redknap, 1985; Gehl, 2010; Jacobs, 1961). The third group include typological and morphological studies (Kropf, 2011; Watson, 2016) which aim to studies the physical form and socio-spatial aspects of public space.

Young (2003) defines accessibility, inclusion and tolerance of difference as desirable qualities of public spaces. After reviewing the development of public space in contemporary cities through a series of major empirical case studies, Madanipour (2013) recognises public space as a public good and defines it as an accessible place developed through inclusive processes. In literature access, openness and visibility appear as the key measures of publicness of a space (Hong & Shin, 2016; Latham & Layton, 2019; Tonnelat, 2004). Kärrholm (2007) distinguishes between accessibility and availability and highlights that a site may be technically available to people but due to some barriers become accessible to a certain group. In addition to access, safety and security have been put forward as an important quality of good public space. Schmidt & Németh (2010) note that planners and designers have increasingly become concerned with the ways to improve the real and perceived safety of public spaces.

Madanipour’s (2004, 2013, 2014) work on public places in deprived neighbourhoods in ten European cities, including Stockholm's Tensta provides some basis for comparisons with Rosengård's context. His findings suggest that

the number of public places was limited in these areas, whereas the existing ones were of poor quality and not maintained well. The public locations also often served as an arena of conflict, which can be explained by the fact that many groups of different backgrounds live in the area, who do not speak the same language. There could also occur conflicts about the access to the areas, because some groups, who use the site more, tended to exclude other groups (Madanipour, 2004). Although the study by Manipour (2004) does not focus on how to improve public meeting places, the empirical findings support that good quality public spaces and meeting places can contribute to improved quality of life for the residents in marginalised areas.

Mehta (2014) in his empirical study of public spaces in downtown Tampa, Florida, argues that good public space is responsive, democratic and meaningful. He highlights inclusiveness, meaningfulness, safety, comfort and pleasurability as five qualities to consider while planning and evaluating public spaces. In terms of functions, facilitating a platform for engagement and discussion, for planned and spontaneous encounters, and for the learning of diverse attitudes and beliefs are suggested as the roles that good public space should take on (Mehta, 2014). Kärrholm (2007) and Hong & Shin (2016) also agree with Mehta (2014) in recognizing adaptability as a good public space characteristic and argue that public space must accommodate a wide range of uses and possible activities.

Publicness is also a key notion in public space studies and it encompasses the key qualities used in conceptualising public space (de Magalhães, 2010; Németh & Schmidt, 2011; Varna, 2014). Varna (2014) develops a so called Star Model to measure the publicness of a public space using five themes or dimensions of ownership; physical configuration, animation, control and civility. By applying the model to empirical cases, Varna concludes that the five dimensions could reflect the reality and the public spaces while considering the specificity of their cultural context.

In an empirical study of the public spaces in London, Carmona (2015) has observed ten qualities as the key features of a good public space. According to his findings, good public spaces are evolving, shaped and reshaped through processes of design, development, use and management. The spatial organisation in good public spaces usually distribute the space between pedestrians and traffic in a balanced way. Good public spaces, while being free inclusive social spaces, are delineated in such a way that the boundaries between private and public do not become unclear or confusing. The physical design of public spaces usually reflects the trends, styles and formats dominating at the time when they are developed, however, good design of public spaces are timeless, have a robust design and are adaptable to change over time. As for the perceptual and experiential qualities of the space, good public spaces often offer meaningful experiences and encourage the user to engage in activities. Finally, good public spaces are not scary spaces and offer comfort, security and safety to their users.

Everyday Multiculturalism

As societies become increasingly diverse, the need for generating powerful connections that cross difference has become an important goal for the developments in many domains, including planning the built environment and public spaces (Neal et al., 2017). Public space offer potentials for exchange

among people of diverse cultures and backgrounds, which in turn could harbour opportunities for learning from differences and building common bonds (Gaffikin, McEldowney & Sterrett, 2010). Amin (2008) reasons that “public space, if organised properly, offers the potential for social communion by allowing us to lift our gaze from the daily grind, and as a result, increase our disposition towards the other” (Amin, 2008). In dominantly immigrant neighbourhoods, the value of public space is crucial since such areas tend to have a large share of the groups who are vulnerable and at the risk of exclusion. In such a context, meeting and developing social bonds with native people helps the immigrants to nurture a normal social life (Gilroy & Speak, 1998). Nevertheless, it is often the case that public space in immigrant neighbourhoods appears to be of low quality since these locations are perceived to be of small significance, all of which make immigrant neighbourhoods more exposed to exclusion and deprivation (Zirk, 2011). Watson & Kessler (2013) also highlight the value of urban design for revitalisation of rundown neighbourhoods and state that in both Europe, UK and the USA, there are marginalised areas that could benefit greatly from improved design and development of good public spaces.

The literature offers two strands of thinking about public spaces and urban diversity, one perspective views public spaces as where differences based on distinctive and closed identity can be affirmed, and the second perspective takes a more relational approach and recognises public spaces as where negotiations, collaborations and contestations of the differences lead to pluralism of identities and belongings (Gaffikin et al., 2010). While Mean & Tims (2005) emphasises on understanding a public space from the perspective of the people using it, the extent to which space is perceived public may depend on both physical/material and social/human factors. Amin (2008) argues that in order to understand the relationship between public space and public life, it is important to examine the total dynamic involving human and non-human that is present in a public setting. Accordingly, urban sociologists and planners have been occupied with the question of how the design and qualities of the spaces as the material field where collective and social practices happen can facilitate social bonds, or in other words, create more inclusive urban spaces. Building on the discussion in the previous section, one could argue that a public space should be accessible to all, or as Zirk (2011) claim, it could be seen as a neutral territory, and should not exclude anyone based on age, gender, race, ethnicity, social status, etc. Exclusion is a multidimensional phenomenon with both social and spatial dimensions, this implies that an enhanced physical and material environment could mitigate social exclusion and encourage social inclusion and diversity (Zirk, 2011).

Neal et al. (2017) in their empirical studies, using participant observation and interviewing, find that public spaces, no matter open or closed, unregulated or orderly, provide possibilities of gathering unknown others and provide settings facilitating encounters and interactions between strangers. They further assert that public spaces can strengthen a sense of connection between people even without them having direct interpersonal interaction. Their findings suggest that access to social spaces, be it open green spaces - as visual multicultural landscapes- or cafés or restaurants - as managed or regulated spaces- could support a range of social connections including short encounters to strong bonds of recognition. In particular, spaces that are characterised as anonymous with predictable routines, seem to be perceived accessible and different groups feel more confidence and ease in using them. This aspect is in line with what Madanipour (2005) identifies

as the common feature of public spaces. He argues that public spaces are outside an individual´s or group´s control, and the less restriction it has, the more public it becomes (Madanipour, 2005). Neal et al. (2017) also highlight that shared activities such as team sports, writing groups or gardening groups play a significant role in shaping social connections from a sense of commitment to closeness.

In a recent study, Kärrholm & Wirdelöv (2019) studied public spaces in the ethnically and socially diverse area of Norra Fäladen, Lund. They observed that the transformation of local spaces into reduced or scattered public spaces could lead to weakening association and appropriation of the neighbourhood as well increased differences among people because of public space dependency and quality of life of living standards (Kärrholm & Wirdelöv, 2019).

In planning practice, multi-national urban developers tend to build remarkably similar urban spaces around the world regardless of their local context. Only parameters connected to consumption and entertainment are kept in a local context. A result of this can be that the distance between the developing people and the local inhabitants grow continuously. One may conclude that there is a conflict in interest or a failed understanding of local needs, and the gathering of feedback from the people who use the spaces being developed is missed. As public space becomes a market for profit, there is a risk that the generalisation of the design of urban space makes it poorly adapted and thus not relevant for the affected citizens. This may, in turn, create problems for people to build an identity in relation to space, and to identify with the city. Even though a similar setting in two very different locations will affect the way people use and visit the area, the problem comes down to not listening to the local needs and the potential that space serves as an arena for expressing these needs (Madanipour, 2003; Magnusson, 2016). Carmona (2015) rejects a universal model for the perfect public space and offers a new flexible narrative of diverse spaces that acknowledges the diversity of users and the differences in their needs.

With all the above taken into consideration, when it comes to interactions between people with diverse age, social and cultural background, the design of public space plays a substantial role for them even to take place. Finally, in the light of new narratives of multicultural public spaces, any evaluation of public spaces should be situated in the local context.

1.3. Thesis outline

With this introduction aiming to set the relevance of the research problem in the context of urban studies and introduce the aim and questions guiding this research project, the following chapter presents the theoretical framework informing my data collection and analysis. Chapter three presents the study object, describing the features and background of Rosengård as well as introducing the selected study sites in more detail. In chapter four the methodology and methods employed in the research to address the research questions is covered. The analysis and results are presented in chapter fine and finally, chapter six concludes the report by a reflection and response to the questions introduced in the first chapter.

2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The aim for the thesis is to examine the outcomes of the redesign of three public spaces on public life in the socially segregated area of Rosengård in Malmö. In particular the function of public spaces and the effect from public spaces on the public life as well as the socio-material exchange is of interest. Magnusson (2016) introduces a conceptual toolbox with concepts that looks promising in the scope of this thesis work, and these concepts build on Actor-network theory (ANT) and

territoriality. In order to examining the impact public space has on public life, the

relationship between people and the materialities of the space and the way they shape social dynamics is interesting. ANT is helpful for the analytical analysis of the process of how different practices of public life is shaped, while territorial perspective enables the possibility to describe the practised public life using the socio-material formations. The conceptual toolbox aims to analyse the function of public spaces and examine to what extent the concepts could explain the relationship between the materialities of and the public life unfolding in those spaces in the context of the vulnerable neighbourhood such as Rosengård.

In order to support the work in this thesis, this chapter starts with an overview of actor-network theory, followed by an overview of territoriality and concludes by explaining the different concepts in the toolbox by Magnusson (2016) based on ANT and territoriality terminology.

2.1. Actor-Network Theory

Actor-Network Theory (ANT) is a relational and agency-based theory established by Bruno Latour, Michel Callon and John Law in1980s (Blok et al., 2019; Michael, 2017). ANT, as a theoretical and methodological approach, was a response to the need for a new social theory adjusted to science and technology studies aiming to rebuild a social theory out of networks (Latour, 1996, 2005). The ANT perspective has become a popular approach for studying the role of nonhumans in social life in more disciplines, including anthropology, geography, management and organisation studies, political science (Michael, 2017). This popularity is due to the analytical tools that ANT offers for exploring the socio-material world as a composition of both human and non-human elements. Recently, there has been an increased interest in applying ANT within the field of architecture and urban studies, and several researchers have employed ANT in their investigations of the political and social dimensions of design (Kärrholm, 2007; Kim, 2019; Magnusson, 2016; Müller & Reichmann, 2015; Storni, 2015; Yaneva, 2009). ANT builds on the idea of that there is nothing but networks (Latour, 1996) and is characterised as a relational theory because of its emphasis on specificity, situatedness and subjectivity rather than objectivity and truisms which guide the traditional approaches in architecture and studies of space (Magnusson, 2016).

ANT, which in some literature is also referred as the sociology of translation (Callon, 1984), deals with the mechanics of power and describes social relations such as power and organisation as network effects (Law, 1992). The central idea to this perspective is suggesting that “the social is nothing other than patterned networks of heterogeneous materials” (Law, 1992). He further clarifies that

‘social’ for ANT indicates a type of momentary association between entities when they are clustered together into new shapes. Latour (2005) describes that “social emerges when the ties in which one is entangled begin to unravel; the social is further detected through the surprising movements from one association to the next”. Having the term actor in its name, one can view ANT as a study of events that are understood as networks of associated actors, and the interest is to trace how different actors associate with each other and how such associations shape and reshape the social. The main slogan of ANT would be “Follow the actors!” (Blok et al., 2019; Latour, 1996). Actors are entities that can provoke change in the state of affairs and “made to act by many others” (Latour, 2005). Accordingly, it is possible to identify the qualities of actors by tracing their actions (Magnusson, 2016). Another key concept to ANT is actant which is simply anything that can act but they may be the agency that enable actors to “modify other actors through a series of trials”(Latour, 2004).

The definitions also imply that the type of actors accounted for shaping social is not limited only to human. Latour (2005) argues for granting non-humans active roles and suggests that the world should be understood as made up of actors that can associate with anyone or anything in various ways. ANT thinkers recognise the material “artefacts”, “things” as actants which can produce and reproduce the relations, social networks or “practices”’ that make up the social world (Müller & Reichmann, 2015). As Magnusson (2016) emphasise, ANT does not exclude anything from being able to interact, change or differentiate the composing of heterogeneous clusters, thus in the context of urban space, the urban material such as benches is an example of actants and in different situations may act as a vital actors shaping the public life. Similarly, one can expand the nonhuman actants examples to include ideas, organisations, machines, etc.

Drawing on the ANT, public life could be understood as collective or a group of coexisting clusters of humans and nonhumans that could exchange properties (Latour, 2004). Latour (2004) states that collective represents the procedure for collecting associations of humans and nonhumans into a whole and such pairing “make it possible to fill up the collective with beings endowed with will, freedom, speech, and real existence” (Latour, 2004). For networks to retain their shape, the relations and associations need to repeat frequently to stabilise them.

As it was discussed above a signature quality of ANT is using the conceptualization of actors and actants to distribute agency symmetrically among human and nonhuman such as materials, movements, etc. (Blok et al., 2019). Agency designates the ability to prompt a difference and modify other actors actions; however, ANT thinkers separate agency from notions of free will or intention. Although actors can exercise agency and authorize, allow, afford, encourage or forbid the actions of other actors, their agency is more open than the traditional natural causality (Latour, 2005). Agency in this sense “is ascribed to actors, rather than ‘possessed’ by them” (Michael, 2017), it is always distributed, temporal and fluid as it is created by the associates; thus it can not be essential to the actor itself (Magnusson, 2016).

Mediation and translation are another set of key ANT concepts that describe the process of composing networks. Latour (2005) emphasised that “there is no social realm, and no social ties, but there exist translations between mediators that may generate traceable associations”. Translation is the mechanism by which networks

take shape and represents the continuousness transformation and displacement of meanings, goals, interests etc. (Callon, 1984). On the other hand mediation reflects the role of other entities participating in the course of actions as they are overtaken by other agencies (Latour 2005). Objects, both human and non-human are not mute but rather speak through mediators and intermediaries (Magnusson, 2016). While a mediator can transform, translate, distort and modify meanings, an intermediary is faithful and predictable and conveys meaning without any transformation (Latour 2005).

Acknowledging that both human and non-human have the ability to act is the principle of generalised symmetry, which also characterised ANT as a less hierarchical empirical and analytical approach with a flat and horizontal ontology (Magnusson, 2016; Storni, 2015). Magnusson (2016) notes that the same principle encourages ANT-influenced studies to take more explorative approaches, instead of presupposing, and seek to recognise only hierarchies that are situated and produced in time and space. This quality of ANT is valuable for the studies of urban space. In urban studies literature, it is common to assume that events take place because of human actions despite the constant presence of the material space, and the architecture is merely abstract, fixed and passive and without agency (Müller & Reichmann, 2015). ANT helps to lose the predetermined perspective on how events and actions produce and are produced in urban space (Magnusson, 2016). Moreover, ANT integrates a relational perspective to design by likening it to composing heterogeneous clusters of human and nonhuman actors that are associated and reinforce each other (Storni, 2015). Similarly, in my explorative study, I build on the view that urban space and any other non-human entities, similar to humans, have the potential to assume an active role in the production of social and public life. I trace the actors in the urban public space and seek to understand their capacities for creating clusters of humans, architectures, mobile artefacts, cultural and social practices.

One common critique concerns whether ANT is a theory or not (Latour, 2005). While being referred to as a theory, ANT could be recognised as a more of an analytical and exploratory framework which provide useful concepts and approach for examining clustering of objects, humans that shape the socio-material world (Magnusson, 2016). ANT might not provide a general theory of the social nor explain the causation, but it rather increases sensibility of the investigations and finely tunes the researcher to deal with complexity or describe the specificity (Blok et al., 2019; Law & Singleton, 2014). Other criticisms arise from comparing ANT to alternative intellectual traditions or its inadequacy in dealing with the findings of some empirical studies (Michael, 2017).

In summary, ANT offers concepts useful for studying the urban and ANT-influenced urban studies have been productive (Blok et al., 2019). An ANT analytic approach is helpful for the analysis of socio-spatial effects by exploring the transformation of relations among both human and nonhuman entities. It allows for accounting for more complex networks of associations, tracing actors and actants across scales which are useful for studying the factors underlying the formation and stabilisation of heterogeneous collectives of human and material entities in urban spaces.

2.2. Territoriality

“[territory is] a meaningful aspect of social life, whereby individuals define their scope of their obligations and the identity of themselves and others” (Shils, 1975).

The territorial perspective aims to explain how people, activities, and rules can by claiming and producing time-spaces, become associated with, and expressed through a specific territory (Kärrholm & Wirdelöv, 2019). Sack (1986) refers to territoriality as a deliberate strategy and “attempt by any individual or social group to affect, influence, and control people, phenomena and relationships by delimiting and asserting control over a geographical area” (Sack, 1986). He maintains that the territoriality is about using space as a medium for gaining power. Under this perspective, territory is understood as an act or practice and it is not confined to the traditional definition as an object or a bounded geographical area (Brighenti, 2010; Kärrholm, 2014). In light of this definition, Kärrholm (2014) asserts that while territories are dependent on materialities, they constitute events and expressive power relations that produce boundaries. This defines territory as a socially constructed phenomenon denoting power and meaning beyond a fixed horizontal physical space (Kärrholm, 2007; Smith & Hall, 2018). Time is another significant dimension for territories and additionally Bell et al.(1996) suggests that a set of behaviours exhibited by a person (or a group of persons) based on their perceived ownership of physical space is human territoriality.

There are several ways to produce territories, Kärrholm discusses four forms of production in (Kärrholm 2004, 2007): territorial associations, appropriation, tactics and strategies and these forms can be used as tools in analysis of the public life in urban space. There are several activities (e.g. social interaction and commercial activities) that produce territories, territories “are the effect of the material inscription of social relationships” (Brighenti 2010). In Brighenti (2010) this interactional nature is emphasized by stating that a territory “is not defined by space, rather it defines spaces through patterns of relations” and territorial productions can be fixed, or moving both in time and space. The various forms of territorial production describe the nature of collective space as an on-going process, where aspects of power and power relations are evident and become apparent. It can also be noted that tactics and appropriation are personal production forms while strategies and associations are impersonal. Strategies are usually intentional and linked to outside actors, focusing on the control of certain space like a parking space. Territories always exists somewhere even though territorial production doesn’t always involve physically present actors. A territory always consists of a particular set of nonhuman and human actors, thus this set can always be used to define the limits or boundaries of the territory even if such boundaries doesn’t clearly exist in the physical sense. Additionally, territorial boundaries often become evident through conflicts and controversies, for example a geographical territory is not guarded by the walls and fences that surround them but rather by the distributed agencies operating inside and outside the actual boundaries.

Kärrholm (2007) explains that there is no space that is not a territory, however, territories can be of different kinds where some are permanent and others just last for a short time. In the public space a multitude of territories are produces by different means (physical properties, social interactions, use, etc.) and these

territories can overlap differently, thus forming a landscape with different degree of territorial complexity (Kärrholm 2007). Territorial complexity is a label Kärrholm introduces to describe that the capacity of a space to support several overlapping territorial productions in a non-hierarchic relationship is closely related to the publicness of the space (Kärrholm 2004, 2007, 2012). Territories that overlap can also exchange actors if they are produced in the same spatial and temporal space. Territorial complexity can be seen as a beneficial property of a space since any space that opens up for a range of possible actions should also attract a varied public and enable social exchange, and additionally this exchange usually occurs at the boundaries hence motivating the study of the role boundaries make in the public life.

Territories can be design for a specific activity (for example a bus stop) but can also come into existence from repeating practice. A group of friends having a coffee together at certain public spot every day is an example of territorial appropriation. In this example the physical entities involved is coffee mugs, seating and table facilities, views and so on, and combined with the people involved in the action it assembles into a collective supporting territorial production. Another example of territorial production through association, where for example one would know a park based on visual input because one would have seen a park before. Association is not limited to visual input, colour markings on the road to indicate bike and car lanes as well as the smell from a pizzeria are other examples of association. In Kärrholm (2004) another property of territories is discussed, institutionalized territories. An institutionalized territory is a territory that is reproduced often and regularly. As an example, Kärrholm described that a meadow repeatedly used for football games can be institutionalized in the form of a football field. In terms of production of territories this can be viewed as first an unplanned tactic (spontaneous football) followed by association (the meadow turns into a place football is played) and finally strategic by introducing goals and white lines to solidify the activity.

Another example of strategic territorialisation is when used by authorities in order to make citizens behave in a certain way. Related to urban planning this can be found when the planning authority constructs pedestrian and bike routes. Clear visual markers are for example important for people to know where things can be done or not (waiting for busses, crossing the road.) for flows to be led properly to avoid dangerous situations. These easy to understand indications also play a helping role for foreigners who might not be sure about the Swedish customs regarding the use of public space. An effective distribution of agency is necessary to successfully maintain territorial productions, and robust territorialisation can be made by power delegation to nonhuman actors. For example the maintenance of the territory in the form of the football field from the previous example is based on the preparation of the field, the material quality, schedules and similar.

A seeming notion is that spaces that are empty and underdesigned, i.e. has a low level of specific functionality built in, are the ones that are the most publicly accessible and should invite the most diverse spread of uses and visitors. However, Kärrholm (2007) takes the opposite view, “The access to space has to be subdivided (in time or space) to accommodate different uses and to make room for as many different categories of users as possible.”, because boundaries are not automatically erased just because a space is made open and public. Of course an overspecified architecture may support territorial fixation and decrease the

territorial complexity, and hence territorial concepts become useful in order to determine the level of design, and the effect from it in the public space.

The territorial perspective is a useful concept that can be used when analysing and planning public space and public life in the urban space. "A territory is, in short, a spatial actant, and it brings about a certain effect in a certain situation or place (the network) [...] Territories need to be constantly produced and reproduced (by way of control, socialized behaviors, artefacts, etc.) to remain effective. Borders and control are thus the result of territorializing, rather than vice versa (S. D. Brown & Capdevila, 1999)" (Karrholm, 2007, p.440). Thus inspecting the territorial perspective from the actant perspective can be a promising approach, since the actant perspective turns the what into an empirical question. Further Magnusson (2016) notes that territoriality can be of used in urban design through the incorporation of aspects such as emergence and stabilizations of socio-material formations; i.e. clustering’s and situated heterogeneous clusters. Territoriality initially accounts for all actors (human and non-human) in the ANT perspective and thus aligns very well with this perspective on public life in the urban space. Also, worth mentioning is that territorology is introduced by Brighenti (2010) as a more adequate term for the academic field of territorial research. Both Brighenti and Kärrholm views territoriality something more associated with practice and action, than with physical space (Brighenti, 2010; Kärrholm, 2007).

2.3. Conceptual Toolbox

Combining ANT and territoriality perspectives, Magnusson (2016) has developed a set of conceptual tools to analyse the role of architecture and artefacts in public life. This toolbox composed of six concepts including Anchors, Base Camps,

Multicore and Monocore spaces, Tickets and Rides, Ladders, and finally Punctiform, Linear and Field Seating (Magnusson, 2016). Considering the

previous discussions about ANT and territoriality, these concepts seems the most relevant for describing the potential socio-material exchanges in a public space. This conceptualisation, while providing theoretical contributions to the territoriality perspective –by identifying different material figures or actants-, offers potentials for deepening our understanding of how the physical design impacts urban social life. The six concepts reflect the significance of architecture as a social facilitator and how the design and distribution of particular materialities in public space can mediate meetings between strangers and shared social activities. Moreover, these concepts are sensitive to the actors that have traditionally been overlooked or discarded as less powerful. Accordingly, an application of the toolbox could be instrumental both for building a comprehensive understanding of actors shaping the public life and posing questions in relation to planning strategies and processes (in particular when the concern is dealing with the issues of representation and democratic planning practice). In other words, the approach could be of analytical value while addressing the challenges of segregation and polarization caused by planning and urban design. The rest of this section presents the six concepts from the toolbox in more detail.

Anchors

The concept of anchor refers to individual or clusters of artefacts that demonstrate the capacity to attract and collect humans or even other artefacts frequently. Such

entities, often perceived as desirable to appropriate, support territorial productions and expose struggles for space in public places. Magnusson (2016) characterised anchors as clustering machines and attributes such capacity to their durability as well as them accommodating multiple uses over time. Such features, in turn, enable them to mediate social exchange and stabilise collectives.

Similarly, one can identify anchors based on their links to recurring practices and everyday activities performed when heterogeneous collectives, human/nonhuman assemblages are formed. For example, platforms, trees, lamp posts, signs, furniture and utility boxes in a public space could work as anchors, and their spatial organisation directly affects the human activities that they can accommodate e.g. sitting, placing things or sheltering from the weather or traffic.

Magnusson (2016), in his empirical study, observes that the agency and affordances of anchors vary depending on the situations and whether they are present as an individual or in groups. A successful group of anchors are the ones that provide shelter from undesirable phenomena (bad weather condition, traffic, noise, etc.) and have a higher capacity in clustering both humans and artefacts. Magnusson further explains that an urban space may have multiple anchors, or anchors with capacity enough to serve multiple individuals (unknown to each other) or multiple groups at the same time that could lead to increase in both the potentials for social interactions and territorial complexity. On the other hand, a space with a single anchor may risk dominance of only one individual or a homogeneous group. To summarise, a public space with multiple anchors fosters potentials for social exchange between strangers as such features afford diversified and overlapping appropriations and movements (Magnusson, 2016).

Base Camps

Base camps are territorial appropriations that are formed in relation to the existing anchors in space. One could see them as the anchors that individuals or groups, using territorial tactic and territorial marking, frequently access and appropriate overtime. A typical example for base camp formation occurs when individuals or groups leave objects such as blankets, bags, clothes, etc. to mark a space as a territory and secure the possibility to leave and return without losing their access. According to Magnusson (2016), base camps as actants are closely connected to anchors, but the two actants differ in terms of their functions. While anchors enable social exchange via increased exchanges between humans and nonhumans, base camps support human interactions by encouraging remaining in the space.

Mobile anchors such as mobile furniture not only can, similar to the stable anchors, facilitate the emergence of base camps, but even more so they can carry their base camp features while moving and when meeting each other gain the potential for more composite and larger base camps. As for the physical design, the camps mostly feature horizontal surfaces, which could accommodate sitting or placing other artefacts on them (Magnusson, 2016).

Magnusson (2016) links the quality of the base camps to the territorial tactics and the properties of the artefacts used to mark the base camps around anchors. He maintains that the number, distribution and permanence of such artefacts are significant for the nature of the connections between the artefacts and the anchor, thus affecting the stability of the base camps. In his empirical study, Magnusson (2016) also observed that collective camp arrangements could support stronger

territorial tactics. One reason is that in the spaces hosting multiple camps higher number of collectives including human and nonhuman actors who can guard a camp are also present.

Multicore and Monocore Spaces

Magnusson (2016) defines a core as an activity that is closely connected to a spatial position, specific material form and certain usabilities. A core attracts people like anchors do, but unlike anchors, they collect humans for a specific purpose or activity administrated by human actors or the strategic organisation of non-human entities. Accordingly, mono-core spaces cluster people for a single type of activity, and thus, people with similar interests will appear at the site. Magnusson (2016) argues that managed and more private collective spaces tend to be monocore. A basketball court where no other activity than watching or playing basketball is offered could be a typical monocore space. However, the same space may become a multi-core space if it provides more diverse activities e.g. accommodating eating and drinking by adding food stands. Similarly, Magnusson (2016) suggests that depending on the number of activities and the diversity of the attracted clusters, a space may change from monocore to multi-core and vice versa at different points in time.

Multi- and mono-core spaces serve different functions in the social space. A monocore space will create stronger bonds between strangers that meet there, due to their common interest in that particular single activity. The same people will likely return and form persistent groups. However, this narrow profile of interest or skillset may mean that the individuals that do not match in the monocore space may be, actively or passively, excluded. At the same time, depending on the activity, it may create opportunities for forming new collectives and creating social bonds across cultural and social differences (Magnusson, 2016). In a multicore space, the probability of drawing a broader audience from the citizens is higher, which in itself would cause more frequent encounters between strangers. However, these would be a lot briefer, and not form as strong bonds (Magnusson, 2016). A conclusion that could be made from this is that these interactions change the space on a more territorial level, as the exchanges are more connected to the actual territory than the activity around it.

Magnusson (2016) argues that a mixture of monocore and multicore spaces formed in close distances could support encounters among strangers to take place and grow into durable relations.

Tickets and Rides

Magnusson (2016) developed this concept based on his observations on indirect relations between humans and multiple artefacts and in particular the cases where certain actors or artefacts are required to gain access to another group of actors. The first one, a “ticket”, is often a personal artefact that is carried by and belongs to an individual. The ticket enables or gives access to an affordance of another artefact or in the language of Magnusson (2016), a “ride”. Simply put, the ride is a public and shared artefact, but to enable certain its usages, it requires the user to have a personal artefact, i.e. the ticket, to interact with it (Magnusson, 2016).

This metaphor can stretch rather widely from being very abstract to almost literal. One very abstract example would be a cup of coffee acting as a ticket, and a block of concrete acting as a table. To enable the “ride” of the concrete block to become a table, the visitor must have the ticket – a cup of coffee. A slightly more concrete example would be a boule court, where the players bring their boule sets. To play boule (the ride), the visitor must have a boule set (the ticket). The ride could be a bicycle pump, and the ticket a bicycle – an example that is not very uncommon in Malmö. In the most concrete example, the ticket is an actual ticket to a carousel, and the ride is the carousel. Some tickets can inspire a search for a specific ride. Some examples of this brought up by Magnusson (2016) include Take-away food - which triggers a search for a horizontal surface to sit, a BMX or skateboard – which triggers a search for a suitable landscape to ride one of those. And the concept works the other way around; a nice spot in the sun might trigger a search for a coffee, and a nice skateboard park might cause the visitor to come back with a skateboard (Magnusson, 2016).

Tickets and rides can also create clustering and encourage social exchange. Picnic areas are great examples, presented by Magnusson (2016), which can be observed in context of Malmö as well. It is common that when people have barbecues or picnic in the park or at the beach, the grill/picnic basket act as a ticket to use the grill facilities. Here we often see a combination of rides – the ocean, for those who brought swimwear, an area to play football or Raquetball, among other things. To summarise, the concept of ticket and ride captures how human-artefact hybrids could have a different agency and how what we bring with us to space can condition our access to space, social exchanges and actions or vice versa. Magnusson (2016) emphasises that tickets and tides are important actors while designing for connectivity and territorial diversity as the organisation of the “rides” in the urban space can efficiently cluster people and encourage social exchange.

Ladders

As it is natural that different locations in space would be valued differently, Magnusson (2016) uses the concept of ladder to refer to individuals’ subjective ranking of the attractive locations in a site. Appropriation ladders help analyse the choices visitors make in positioning themselves on a site as it can capture a hierarchy within these places and the visitors. While the ladders, due to personal taste and the situation, may vary among the individuals, it is possible that interests and preferences overlap and result in common patterns of attractive locations in a site. As a result, competition for the appropriation of such location is likely to increase. Typical examples are sheltered spots or locations with a good view. When this happens, both people and artefacts frequently form clusters near these appealing actors. A ladder consists of several micro locations with different affordances and usages clustered together, where competition is formed among the visitors to distribute among these (Magnusson, 2016).

Presence of places with real or perceived varying qualities leads to different people finding different places appealing and, thus formation of several ladders in a site. This points out the implications that ladders for design, as it indicates that material diversity in space, is equally important as accommodating variety of activities. With differences in material qualities attracting different groups of people, a space with several different qualities can accommodate diverse social

and socio-material clustering as well as the movements between the alternative locations (Magnusson, 2016).

Magnusson (2016) notes that ladders can add a temporal dimension to the analysis as they reveal the movements and the relocations that people make in space to reach more attractive locations of their ladder. To summarise, a set of attractive micro-locations enables space to afford for both larger and more diverse group of visitors to find comfort, relocate between alternatives, and engage in different clusters.

Punctiform, Linear and Field Seating

Seating, which is an essential factor in all public spaces, come in many different forms and shapes. Magnusson (2016) talks about three essential types of seating artefacts – Linear, Field and Punctual. One example of the linear seating constellation is typically a bench. The main property of such an artefact is that it is very limited in how users can arrange their sitting positions. They can only sit next to each other, in a linear formation, and typically only offers seating for a pair or a small group of friends. People who are strangers to each other tend to choose different benches or sit as far away from each other as possible. Sometimes benches are arranged opposite to each other allowing for bigger groups to sit, thus inviting more social interactions between strangers, but the options for the users to arrange their sitting positions are still limited because of linear features (Magnusson, 2016).

The field seating constellation opens up a variety of uses for the seating artefact. This artefact could vary extremely in its look, from a wooden deck, a grandstand, stairs, or benches with a different shape other than the traditional straight one. The common denominator is that the user can choose in a variety of ways of sitting and arranging themselves on the seating artefact. A punctiform seating is to put it simply a seat for one person like a chair or stool. What is especially interesting is that this kind of seat is very often movable. Stationary punctiform seats also occur, but very often the users can move and arrange this kind of seats as they like, creating freedom for the users to arrange their seating after their individual needs (Magnusson, 2016).

Magnusson (2016) suggests that stationary seating form, like a bench or a more open field constellation, can be used by the urban designers and planners to control where to draw people in a space, to create and encourage social interactions for example. The mobile seating can then be used to increase the available options for the users, to work towards a more diverse solution that fit the needs of more people. The field seating option also in itself offers a large amount of freedom, as the users can arrange their constellations on the artefact and choose how they position themselves.

3. PRESENTATION OF OBJECT OF STUDY

This section will provide an introduction to the Rosengård district along with its history, architecture, and the stigma built up around the district after its construction. Three chosen sites – the public spaces Bokalerna, Rosens röda

matta, and a part of Rosengård Centrum will be described, all of which are the latest redesigned areas of Rosengård.

Rosengård district, covering approximately an area of 3.3 km2 in the eastern part of Malmö (Malmö stad, 2019), was constructed during the years of 1960-1970 as part of Sweden's Million Programme in Malmö (Hall&Viden, 2006). The housing development in the area took place to address the increased demand for housing due to the industrialisation of the city (Borgegård & Kemeny, 2004).

Based on the ideas of modernism, the neighbourhood design composed of high-rise and mono-use buildings with wide roads focused on the availability of cars and large green space between buildings. The houses were built with simple facades, all of them with a similar look. With a hospital, a library, schools, and even its own shopping mall, the idea was to make Rosengård look like a city in the city. After the decline of the large shipping industries which were the main force behind the developments at the time in Malmö, the city and areas such as Rosengård started the face major challenges (Petersson & Tyler, 2008).

Already before it was completed, critical voices were raised against the design of area (Tykesson, 2002) and in the early 1970s, many of the new apartments stood unoccupied and social problems had arisen. Rosengård stood as a representative for the construction of the million program, which many have regarded as a major failure and this stigma has stayed. In 1966, Rosengård was described as “newly built slum”(Tykesson & Magnusson Staaf, 2009). People started moving from Rosengård to single household villas outside of Malmö, and more low-income families moved in. When talking to Rosengård's residents, they experience the feeling of security and enjoyment of their homeland, as opposed to the international media discourse – talking about violence, urban rage and the social exclusion of citizens.

In the 1990s, Malmö received a large flow of immigrant which were mostly refugees (Petersson & Tyler, 2008). Today, Rosengård with about 24000 inhabitants -according to the data available from the end of 2018-(SCB, 2018) features a dominantly immigrant area of Malmö. As Figure 2 illustrates, about 48% of the population living in Rosengård have an immigrant background, while the other 48% of the inhabitants are Swedish with both parents born abroad (SCB, 2018). In total, approximately 96% of the residents have a foreign background which is much higher than the average city level in Malmö (slightly over 40%) (SCB, 2018). According to the population data from Statistics Sweden -Statistiska centralbyrån- (SCB) the area has significantly higher rates of unemployment and people unqualified for higher education than the rest of the city (SCB, 2018). Overall the district struggles with many challenges due to concentration of poverty and deterioration (Dikeç, 2017; Parker & Madureira, 2016). In this context, the city authorities adopted several strategies such as “Welfare for All”(Välfärd för alla)(Petersson & Tyler, 2008) and “Rosengård in transition”(Rosengård i förvandling)(Malmö stad, 2016) to address the mentioned social problems.