MAXWELL

HUBBERT

MOBILE PHONES IN

SOCIAL SETTINGS

How and what mobile phones are used for during

face-to-face conversations

Malmö Högskola, Spring 2016

Master’s in Media and Communication Studies: Culture, Collaborative Media, and Creative Industries

Faculty of Culture and Society at the School of Arts and Communication. Supervisor Pille Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt

One Year Master´s Thesis (15 ECTS Credits)

Table of Contents

1.0 Abstract 3

2.0 Introduction 4

3.0 Literature Review 7

3.1 Uses and Gratification Research 8

3.2 Mediatization Research 12

3.3 Social Presence Theory/ Self-Determination theory /Mindfulness

Research 14

3.4 Theory of Affordances 18

3.5 Research Relating to Problematic Mobile Phone Use 19

3.6 Benefits of Mobile Communications 24

4.0 Data Collection & Analysis Methodology 27

5.0 Analysis 33

5.1 H1- The majority of phone use will not be related to the face-to-face

conversation. 35

5.2 H2- Increased phone use will be related to phone use that is not related to

the face-to-face conversation. 40

5.3 H3- Friends will be most likely to use the phone for purposes of

socialization with non-present relationships. 43

6.0 Discussion 47

7.0 Conclusion 50

8.0 References 52

1.0 Abstract

Mobile phone use while in the presence of physical conversational partners is a reality in modern day life. Many researchers have investigated how different subgroups use mobile phones and the consequences of such use. The goal of this research was to determine how mobile phones are used in social settings when face-to-face conversations are taking place. The main questions that the research attempted to solve were: (1) If the phone use was related to the conversation at hand, (2) if the intensity of phone use was correlated to how the phone was used, (3) and if phones are used during conversations in different ways depending on the relationships and demographics of the conversational partners.

The research was conducted in Malmö, Sweden at bars and cafes´ by

administering a semi structured verbal interview on people seen using their cell phones while in face-to-face conversations. Relevant demographic information was recorded as well as five open ended questions. The questions were aimed at understanding how the phone was used, and the phones use in relation to the physical conversation.

The research was conducted using the research paradigm of Positivism and the data was analyzed using an Inductive research strategy. Uses and

Gratifications theory was the main theory that this research was viewed through. In addition, relevant information was drawn from various psychological theories as well as problematic mobile phone research.

The findings show that the majority of phone use is unrelated to the conversations at hand. But often this phone use is re-integrated into the

conversation at a later time. It was also found that phone use related to information retrieval was most likely to be related to the face-to-face conversation. Additionally, the data showed that conversational partners that use the phone a lot are highly unlikely to be using the phone in relation to the conversation. The data showed that friends are most likely to not use the phone in relation to the conversation.

2.0 Introduction

In the early 1990s the western world saw the introduction of portable

handheld mobile phones, with the widespread adoption of mobile phones coming between 1995 and 1998 (Wikipedia, 2016). The first iPhone was released in mid 2007, (Wikipedia, 2016), and has since been widely associated with being the first widely distributed smart phone. Its release represents a shift from standard mobile phones to the smart phone era (Goggin, 2013). Mobile phones are changing the communication traditions of families, friends, and social networks (e.g., Goggin, 2003; Przybylski, 2012; Liu, 2014; Coyne, 2013). However, research into how mobile phones are used in social settings, and the effects of such use, has largely lagged behind the rapid development of the mobile technologies. Currently young adults in developed countries use digital media devices in excess of 12 hours per day (Coyne, 2013). The impact of mobile phones on face-to-face communication has received little academic investigation and should be researched further.

This papers goal is to look at how people in social settings use their cell phones, and why they are using their cell phones. The data is approached with the Uses and Gratifications theory as its main theoretical reference (Dunne, et al., 2010). This Uses and Gratifications theory states that people seek out and use different media to satisfy specific psychological needs. I believe this theory is especially applicable, to mobile phone use research, because the mobile phone is now the dominant medium for consuming media as well as connection to social networks. People experience their lives through the mobile phone and therefore make decisions about how they wish to interact with the world through the phone. The goals of this research project are to explore the uses of mobile phones while in

social co-present settings, and to see if these uses complement or detract from the face-to-face conversation at hand. The study also aims to add to the body of

knowledge surrounding whether phone use in face-to-face conversations has an impact on interpersonal relationship development and communication.

The research project was conceived out of my personal observation of an increased use of mobile phones when people are in public places socializing. Reinsch labels the action of participating in multiple conversations simultaneously as multicommunicating (Reinsch, 2008, p. 391). I have noticed that, over the past few years, it has become more common to see people interacting with their

cellphones while in face-to-face conversations. My initial assumptions were that the use of a cellphone while participating in face-to-face communication would be detrimental to the conversation at hand, and result in less relationship development and a lower overall quality of conversation.

Although I have some previous experience with observing people using their phones while in co-present situations the research strategy that was used in this project is the Inductive research strategy. The research projects general outline is the collection of data and then drawing general conclusions from the collected data. The data the I have received from my survey has been coded into a qualitative form which has allowed me to do comparative analysis’s. I have

observed this approach in the majority of the literature that is closely correlated to the motivations and uses of mobile phones. This has led me to undertake this research project using the research paradigm of Positivism. As I am gathering data using the scientific and combining this with previous research that has been

obtained similarly I think that it is justifiable to assume that this form of data collection and analysis is a valid one and thus is supported by the naturalism doctrine (Blaikie, 2007).

This research interviews were conducted in Malmö, Sweden at bars and cafe´s with a structured five question survey administered verbally. Relevant demographics were noted, and answers were recorded in a written log book. I have, based on my pre-existing assumptions and theoretical review, three hypotheses for the data that was collected.

H1- The majority of phone use will not be related to the face-to-face conversation.

H2- Increased phone use will be related to phone use that is not related to the face-to-face conversation.

H3- Friends will be most likely to use the phone for purposes of socialization with non-present relationships.

The research project begins with a literature review of relevant theories, and related research, connected to mobile and face-to-face communication. The literature review covers Uses and Gratification theory, Mediatization theory, Self-determination theory, Social Presence theory, Mindfulness research, theory of Affordances, research into problematic mobile phone use, and research related to benefits of mobile phone use. The literature review is followed by the data and methodology section, an analysis of findings, a discussion, and finally conclusions about the research.

3.0 Literature review

The ways in which people interact with each other in face-to-face

communication are often accompanied by mediated forms of communication. The most ubiquitous device for mediated communications is currently the mobile phone. According to the Swiss Federal Statistics Office as of 2013 most countries in Europe have more than one mobile phone subscription per inhabitant, in

Sweden it was 1.30 subscriptions per inhabitant. Additional statistics show that around 83% of Swedes use smartphones as of 2015, with a 10% growth rate year over year (Statista, 2016). This literature review gives a theoretical and empirical examination of the research surrounding how people use their phones during face-to-face communication, and if the phone use is related to the present conversation. The literature review additionally addresses the impacts that mediated

communication may have upon face-to-face communication. I have attempted to give an impartial overview of the available research and have therefore included sections addressing both the positive and negative effects of mobile

communications. As I am attempting to find out how people are communicating with relation to their cell phones, I think that it is important to have a literature review that is relatively broad so that I can have a solid understanding of the competing motivations for communication.

Introduction to Literature

Due to the rapid advancement of digital communications there is an

research surrounding mobile phone use. The ever-changing nature of digital communications, and the explosive growth that has been seen since the advent of the smart phone, has made it difficult for researchers to develop strong theories in relation to how mobile phones are used. In this literature review I will discuss the research that is most relevant to how mobile communications interact with face-to-face communications. This includes Uses and Gratifications theory, theory of Affordances, problematic uses of mobile phones, mobile phone addiction theories, Social Presence Theory, Self-Determination theory, Mindfulness theories, benefits of mobile communication, and multi-communication research.

3.1 Uses and Gratification Research

The Uses and Gratification theory is a theory that states that individuals seek out specific medias to fulfil specific needs. People are goal oriented and approach and use specific medias to satisfy specific personal needs (Kuss, 2011). In the current media saturated environment that we live in multiple media complete for user’s attention. Since people have a finite amount of attention and time they must be selective about which applications are best able to fulfil their needs such as connection, relational maintenance, information acquisition, and status. Uses and Gratification research focuses on what people do with media instead of what media does to people

Blumler and Katz (1974) were some of the first media effects researchers to use the Uses and Gratifications theory to look into how people use different media to receive information (Gerlich, 2015). According to Katz four needs are satisfied by users’ consumption of messages. (1) Social and personal needs are used to reinforce their idea of self as well as personal relations. (2) Media is used to

is used for the satisfaction of cognitive/informational needs. (4) Affective-aesthetic needs, used to reinforce emotional and pleasurable experiences (Curras-Perez, 2014, p.1480).

More recent researchers have further simplified the groupings of gratifications into two categories, the first being how people derive value from the content that is received through the media and the second being the value of the experience of interacting with the media (Chen, 2005). I agree with this simplification as it allows for me as a researcher to clearly distinguish between when people use the

cellphone in relation to the conversation or for other habits that they have

developed around their cellphone use. The content related gratifications from cell phone use have been divided into seven factors: fashion/status, mobility,

affection/sociability, immediate access, instrumentality, and reassurance

(Papahariss & Rubini, 2000, p.179). With relaxation/entertainment falling under the value of experience category of interacting with the media (Gerlich, 2015). It is often the case that these uses overlap in real world use, nonetheless it has still been useful to this research to think of the gratifications in these categories to aid in the analysis of the data.

Engaging in multiple forms of communication is referred to as

multicommunicating (Reinsch, Turner &Tinsley, 2008, p. 391). Research has shown that multicommunicating has been found to be driven largely by a desire for emotional gratifications (Seo, 2015). Seo´s research found that people often

receive emotional gratification from multicommunicating even though they are not consciously seeking this gratification. This same research has found that other seemingly rational motives such as time constraints have not been found to be correlated with multicommunicating. Multicommunicating with the purpose of

connectivity has been researched briefly and the initial findings point to there being a difference between how men and women use cellphones while in co-present

situations (Seo, 2015, p. 677). Research has shown that women are more likely to use their cellphones with the purpose of connecting with their outside social

networks while in a face-to-face conversation. This link has not been observed with men. “Wanting to be always connected and being available to others seems to play an important role in understanding females’ uses of mobile phones and

multicommunicating behaviors” (Seo, 2015, p. 677). The sex of the conversational partners has been noted in the demographics to see if there were different

gratifications received in this research project.

Social networking sites (SNS) have been studied and the data shows that people use SNS´s for different purposes based on their own personal orientations. Most commonly SNS´s are used for relationship maintenance and group

identification, upwards of 80% of respondents in a university sample claimed they used the SNS´s because all of their friends did (Kujath, 2011). This supports the Uses and Gratifications premise that if if people have a need to connect with others they will find a suitable medium to satisfy this need (Chen, 2010). As I expected to find many responses in my research relating to SNS`s I thought that it would be interesting to see if my respondent’s gratifications sought would be similar to that of previous research. SNS research has also found that these sites are used for the formation of social capital and are important for maintaining weak relationships (Kuss, 2011). Curras-Perez has found that most needs related to SNS can be grouped into 3 categories (Curras-Perez, 2014, p. 1480). (1) Functional needs relating to using the SNS as a contacts database/ event updates, calendar. (2) Social needs related to providing support for social circles and as a way to have communication with others. (3) Psychological needs can be fulfilled by feeling part of a community, access to groups and memberships, etc. These grouping can be used in the analysis to further narrow and classify the found uses.

third category of satisfying psychological needs (Curras-Perez, 2014, p. 1481). Curras-Perez (2014) cites the work of Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) which claimed that according to Social Capital Theory, early SNS´s were primarily used for the exchange of information in exchange/resulting in basic psychological needs like affections, gratitude, and socialization being achieved. Uses and Gratifications theory states that people seek out medias to fulfil needs, so if the need is fulfilled they will continue to use the same medium. Research has shown that it is the duration in terms of months and years that is most effective in determining gratifications received instead of how many hours someone uses a specific medium (Chen, 2011). As the data in my research has many accounts of using social networks it will be interesting to see what needs are most often being fulfilled and see if they are correlated to the existing research.

Additionally, Uses and Gratifications theory has been used to study how and why teenagers use mobile phones (Topalli, 2016). This study found that teenagers are most likely to use the mobile phone to access social networks, play video games, and assist in school related activities. However, the majority of research subjects in my sample were no longer teenagers so this theme will not be

developed.

Uses and Gratification Theory research is not universally agreed upon as a valid theory for investigating media effect. The opponents of this theory justify their criticisms by highlighting the lack of evidence showing connections between

gratifications sought and gratifications obtained (Curras-Perez, 2014). Although there is a lack of evidence showing direct correlation between sought gratifications and obtained gratifications it is still a useful theory in that it provides a map of how to think about the different motivations for communications. Additionally, it has been shown that people may seek out one gratification and incidentally receive another as was the case with Seo´s research (2015). Dunne et al. (2010) sites the

work of Severin & Tankard (1998) with another criticism that posits that the methodology often relies on self-reporting by respondents for the generation of data (Dunne et al., 2010). However, the flexibility to allow for self-reporting seems to be very beneficial for researching communication patterns, otherwise

motivations and actions would all too often be hidden. A further criticism has been that the Uses and Gratifications theory often results in the generation of a list of reasons of why people interact with media (Dunne et al., 2010, p. 48). This seems to me to be a very weak criticism as the generation of the motives of use would seem to be valuable information achieved by research.

Some level of self-reporting is necessary to discern the motivations of cell phone use, and the goal of this research is to gain a better understanding of the uses and motivations of cell phone. Therefore, I believe that this research into cell phone use is very well suited to be examined through the lens of the Uses and Gratifications theory.

3.2 Mediatization Research

On the other end of the research spectrum from Uses and Gratifications research is a theory of research that focuses on how media and media institutions exert influence over social institutions and individuals that have to accommodate and work with media to achieve their goals. Mediatization is not to be confused with the concept of mediation which is the use of a medium while communicating that distorts the message and reception of such message, though mediation is part of mediatization research. Simply put the research focuses on how media affect society and culture (Hjarvard, 2008). One of the first focuses of mediatization research was on the impact that media has on politics and how politics has had to change and adapt to new forms of media. One such change has been that there is

now an abundance of information available, therefore attention is increasingly valuable and is fought over by different political actors and media institutions. It will be interesting to see how dominant the mainstream applications have become with regards to use by individuals, given that cellphones have the potential to access the entire internet.

Another pillar of mediatization research is the role of media in social change. Schulz (2004, p.87) outlines four distinct processes by which media change communication patterns and human interactions. (1) Media allow people to communicate over larger areas of time and space. (2) Media can act as a

substitute to social activities that were previously carried out in person. (3) Media facilitates an amalgamation of activities “multi-communication”, whereby media is allowed access to all aspects of daily life. (4) The growth of media has enabled it to have a larger role in society, and now demands that people accommodate for media and adhere to the rules and routines that media encourages. These four pillars of mediatization all work together to make media into a richer more “real” environment which leads to and expansion of the interaction available as well a larger acceptance of the digital spaces that people ever increasingly live in

(Hjarvard, 2008). One such consequence of this is that face-to-face communication is given a different role in society due to its change in cultural significance, while at the same time other media are mimicking face-to-face communication, further reducing the circumstances where face-to-face communication is required. It will be interesting to see how easily these categorizations will fit into this research projects data, and to see which themes are most dominant.

3.3 Social Presence Theory/ Self-Determination theory /Mindfulness Research

Mindfulness research, Social Presence theory, and Self-Determination theory are included in this literature review to provide an overview of the best

psychological practices of interpersonal communication. This provides a backdrop of how and why people communicate best, thus allowing this research project to draw more generalizable, and research backed, conclusions from data.

There are many psychological, philosophical, and spiritual traditions that encourage and promote the practice of mindfulness (Warren, 2003). Mindfulness is defined as being conscious and attentive to what is taking place in the present (Brown, 2003, p. 822). Giving enhanced attention to current experiences allows for people to focus on the moment and task at hand. The action of practicing

mindfulness while communicating allows people to notice and attend to the subtle emotions that run through conversations and are conveyed through verbal and non-verbal cues. When one is attuned with their emotions, and the emotions of the current situation, they are said to have high emotional intelligence. This is achieved by being present and mindful of the emotional state of oneself and the immediate company that one is in (Warren, 2003). A subtopic that will be discussed in the discussion will be if the data shows that there is a disconnect between the uses and potential motivations for uses, and if this disconnect is caused by a lack of mindfulness while in conversation.

Self-Determination theory (SDT) is a theory that suggests that people are autonomously motivated to grow personally when their psychological needs of competence, psychological relatedness, and autonomy are satisfied (Wang, 2014). Most relevant to this research is peoples need for psychological relatedness.

desire interaction, connection, and caring from other people (Baumeister, 1995). The majority of people that were interviewed for this research were in conversation with friends, presumable satisfying their need for relatedness. The mobile phones introduction into conversations allows individuals another pathway to satisfy this need through interaction with larger social networks. However, as Social Presence theory shows this extra pathway may be detrimental to achieving the highest rate of return on time spent socializing due to not capitalizing fully on the advantages of face-to-face communication (Stafford, 2012).

SDT suggests that mindfulness is needed to act in a way that is consistent with ones needs, values, and interests. The vast majority of people have an interest in developing meaningful relationships, thus people should practice mindfulness while in social settings (Park, 2013). To achieve these goals people must be able to focus on their goals and and control their habits, automatic thoughts, and unhealthy behaviors. Practicing mindfulness has been shown to encourage this as well as enhancing present experiences with vividness, clarity, and higher levels of relatedness (Warren, 2003) SDT research has shown that practicing mindfulness is related to and can predict well-being, and less emotional and cognitive disturbance by serving as a self-regulatory function. SDT research is particularly of interest to this research projects as many instances of habitual use of the mobile phone have been observed throughout the interviews. SDT helps to explain why this might be as well as potentially why people are acting against their own interests by multicommunicating when in co-present situations.

Social Presence Theory (SPT) states that different communication mediums allow for different levels of social presence. This is understood as being on a continuum with written communication at the bottom end and face-to-face communication on the top end. SPT research is concerned with which mediums are most suitable for different forms of relationship maintenance. As not all

relationships are close, it is posited that different forms of mediated communication are advantageous over face-to-face communication, as they are able to allow for the appropriate levels of attention and commitment. But for effective interpersonal communication it is face-to-face communication that is considered most effective (Stafford, 2012). Given that we live in a world that people often travel and relocate the option of face-to-face communication is not always a possibility. In this world the mobile phones ability to connect loved ones and reduce feelings of loneliness, isolation, and anxiety are the best option possible, so far (Liu, 2014). SPT will allow me to value the different forms of communication that people interact with in this research project. It will give me a basis to draw conclusions about the perceived value that people draw from their mobile communications.

Closely related to social presence is the newfound phenomenon of perpetual connectivity. Perpetual connectivity, or “always availability” (Park, 2013, p. 182) is the situation where people are always available for contact and are in fact

expected to be available for communications. If one adheres to this then it is understandable that face-to-face communications will often be interrupted by other forms of communication (Stafford, 2012). This research project will investigate if there is a link between feelings of obligation and actual use

Research by Bayer et al. (2015) has focused on the relationship between mindfulness- the mental state of being present in the moment and aware of your feelings; and automaticity- the ability to perform and action with little thought (Bayer et al., 2015, p. 77). The study found that texting automatically is negatively related to trait mindfulness. This suggests that people that do not actively practice

mindfulness and respond to unconscious desires to fulfil emotional needs through the cellphone are likely not as engaged in conversation as those who resist the urge to look and use their cellphones. This research suggests that using a mobile phone while in a face-to-face conversation diminishes the conversation quality

(Bayer et al., 2015, p. 86). This is supported by research on how perceived attention to conversation influences beliefs about conversational partners and conversational subject matter (Rosenfeld, 2015). In this study it was found that diverting attention away from a face-to-face conversation led to decreased interest in the conversational partner as well as decreased interest in conversational matter by the person who was distracted. This research lends credibility to the assertion that mobile phone use is detrimental to face-to-face communication.

There is a term “absent presence” ( Gergen, 2002 P. 227, Rettie, 2005) that describes the duality of using a mobile device in a public space. This term

describes that the act of being physically present but mentally in another space. Being present is defined as being in a situation or environment. So one is present on their phone they cannot be wholly present in the physical place that their body occupies. Relationship development is dependent upon empathic understanding, therefore people who are involved in co-present situations have a lower empathetic attention to their physical counterpart (Rettie, 2005). It is also argued that face-to-face conversations are not “supplemented or substituted by mediated types of communication.” (Angeluci, 2015, p. 175). I think that my research is going to show that there is a distinct division between complementary uses and substituted uses.

3.4 Theory of Affordances

James Gibson is credited with the concept of affordances. According to this theory all mediums of communication have prominent characteristics within them that facilitate certain uses. That is to say that some technologies and media will be perceived by the majority of social actors as having a semi defined role upon what they are best able to do (Hjarvard, 2008, p. 121). For example, a cell phone can be used to write an essay on but a computer is generally accepted as a better tool due to the inherent affordances that the computer has. This is because a computer with its large keyboard and screen have what is called a “perceived affordance” for writing. A perceived affordance is a use that is dependent upon the desired objective of the user. This is one of the major dilemmas that the modern cell phone has. It is a tool that is perceived as the social lifeline to one’s social network and is seen as a tool that can be used at all times and have preference over one’s physical surroundings. This research will add to the body of knowledge concerned with what some of the most perceived affordances of the cell phone are. While the data shows that people use the mobile phone for many purposes the most

reoccurring purposes can been seen to be more readily perceivable in theory.

James Gibson´s theory of Affordances provides a theoretical umbrella to what has been discussed so far. Simply put the mobile phone enables people to

participate in the world unimpeded by time and space. But this affordance of total freedom operates within the boundaries of established societal norms and

practices. The Uses and Gratifications theory allows me as a researcher to uncover the underlying motivations for this readily perceived affordance. The review of SDT, SPT, and research into mindfulness allows for a deeper understanding of the motivations surrounding mobile phone use and multi-communicating.

3.5 Research Relating to Problematic Mobile Phone Use

As of the writing of this paper there is no consensus on whether or not

individuals can be considered medically addicted to their mobile devices. However, correlations have been demonstrated between phone use and negative life

consequences. One of the most widely accepted consequence of mobile phone use is the correlation between driving and phone use, resulting in lack of attention capabilities, even when using hands-free devices (Barkana, 2004). This is so widely accepted in the literature that I will not develop this theme further. But this concept of not being able to concentrate on two things at once, combined with the mindfulness research, lends credibility to the believe that when the mobile phone is being used for multi communication the face-to-face conversation will suffer.

Joel Billieux is the most published researcher attempting to prove this connection between Problematic Mobile Phone Use (PMPU) and addiction. In 2008 Billieux developed the Problematic Mobile Phone Use Questionnaire

(PMPUQ). This was developed in response to the observation that mobile phones are increasingly disturbing social activities. The PMPUQ attempts to target

dangerous/prohibited use, financial problems, and dependencies resulting from phone use. His study found correlations between amounts of sms´s sent and lack of impulse control, as well as elevated depression levels in relation to sms´s sent. The study also showed that men were more likely to use phones in dangerous situations and for sensation seeking, while women have higher levels of urgency, defined as having strong impulses to use the phone in times of emotional stress (Billieux, 2008). However, the findings of this research appear to often be based on assumptions and conjunctions instead of scientific causation. That being said this research project will draw on some of these findings and attempt to corroborate

them if possible.

The lack of a clinical diagnosis of addiction does not mean that phones do not have negative effects on people lives. A Swiss study showed that 30% of people surveyed consider themselves addicted to their phones (Billieux, 2012). Young adults spend more time interacting with digital media, upwards of 12 hours per day, than any other activity (Coyne, 2013). Nomophobia is defined as the fear of not being able to use one’s cellphone (Wikipedia, 2016). Neuroticism and extraversion have also been linked to PMPU (Igarashi, 2008). The extroverted personality trait has been linked to PMPU with extroverts being driven by the need to develop relationships as well as communicate with non-present relations. Igarashi believes: “There is no doubt that compulsive use of text-messages is the most fundamental characteristic of dependency.” This quote sums up his finding neatly by stating that this is the reality of mobile phone use currently. The neurotic pathway has been explained as a dependency by individuals to be constantly reassured of existing relational status (Seo, 2015). Also decreased impulse control has been linked to PMPU and impulse control is highly related to addictive behaviors. Additionally, low self-esteem has been linked to low impulse control in relation to PMPU (Bianchi, 2005). This research project does not go into the personality traits of the

participants, but this perspective on the negative effects of compulsive use does help to support some of the data that has been collected.

Given that mobile phones are a relatively new phenomenon longitudinal studies are needed to prove these theories. Billieux proposes a pathways model of PMPU with four main pathways (1) impulsive pathway; (2) relationship

maintenance pathway; (3) extroversion pathway; (4) cyber addiction pathways (Billieux, 2012). This was later refined to three pathways described as (1) an excessive reassurance pathway; (2) an impulse-antisocial pathway; (3) An

extraversion pathway. This is the only comprehensive model that has been found in this literature review that attempts to explain a road map towards the

classification of PMPU as a clinical addiction. Although this model is well reasoned there is currently a lack of supporting evidence to confirm or deny its validity. This review of Billieux´s work is intended to lend evidence in support of the position that there can be negative consequences of phone use. This research combined with the SDT and mindfulness research create a compelling argument for restraining from using mobile phones without clear gratifications sought.

Phubbing (Angeluci, 2015, p. 174) is a combination of the words phone and snubbing. It is used to describe the circumstance where a phone is interacted with instead of a physically present person. A study performed on Chinese and

Brazilian students found that there are different culturally accepted norms relating to phubbing, with Chinese performing phubbing on friends and acquaintances but not close family and girlfriends/boyfriends. While Brazilians performed phubbing on everyone except for parents (Angeluci, 2015). For Chinese respondent’s

spontaneity was the most significant cause of phubbing. It will be interesting to see if this research projects data agrees with these findings. Both groups expressed that these actions had negative effects on the capacity to talk and express opinions while in face-to-face situations. This is directly related to the Postmodernist Theory of mediatization where media has become so real and vivid that it appears to be more real than the physical and social reality and therefore commands the

attention of the users regardless of time and place (Hjarvard, 2008). In fact, studies have shown that a significant portion of couples that eat together regular interrupt their meals to check for messages on their cellphones. The researchers concluded that this was because the mere presence of a cellphone orients people to thinking about their wider ranging social circles and therefore think about events outside of their immediate social context (Przybylski, 2012). Again this ties back into the SDT and the importance of being mindful about one’s actions. While this research project does not address the mere presence of a phone it will add the the data on how couples use their phones when in each other’s presence.

Engaging in multiple forms of communication has been linked to ADHD and research shows that people with ADHD often are prone to a restlessness that inclines them to constantly be multicommunicating even when a clear goal is not present (Seo, 2015). This leads to less attention for the co-present conversational partner and therefore a negative influence on interpersonal relationships (Turkle, 2011). When an interpersonal relationship is in the beginning stages this can be especially detrimental. Research shows that while people are getting to know each other it is important to participants to have their self-disclosures met with an

appropriate amount of empathy. If a conversational partner is engaged in multi-communication it is difficult to be attentive enough to give this empathy that is necessary for relationship formation (Przybylski, 2012). Some studies have even shown that the presence of a mobile phone is enough to be detrimental to

relationship development. Results of this experiment showed that the presence of a mobile phone was able to inhibit the development of closeness and trust, reduce empathy, and reduce meaningful conversational topics (Przybylski, 2012). When seen through the lens of Uses and Gratifications theory it would appear that there is a disconnect between peoples uses and desired gratifications. This research project will attempt to confirm to which extent this is the case.

Another avenue of research into the effects of mobile phone use is the use of mobile devices in public places. The mobile phone allows for individuals to turn a public place into a private space (Turkle, 2008; Lasen, 2005, p.25), similar to the concept of absent presence. This can be seen as a distraction for co-present individuals that are then expected to apply private norms to public spaces (Park, 2013). Additionally, people can decide more and more who it is that they interact with because of the mobile phones ability to take one out of the public space while still in a public place. This is especially relevant to this research project because its relation to when people use their phone for personal reasons while in the presence

of someone else. A new norm has been developed where it is accepted to be in a face-to-face conversation and exclude the other co-present individual for other social groups ( Park, 2013, p. 184).

Research has shown that people who interact with SNS´s often do so at the expense of their real life communities (Kuss, 2011). This can create a self-fulfilling cycle which leads to less feeling of physical communities and therefore more dependency on SNS´s. This has been correlated to people who are introverts and have low self-esteem. High levels of SNS´s use has also been linked to increased jealousy, and obsessive behaviors by some users (Coyne, 2103). Not all research is in agreement about the effects of high SNS´s use. For example, some research has shown that increased levels of SNS´s use and cell phone use results in

increased face-to-face social interaction time (Coyne, 2013). This research project will attempt to confirm these findings.

Other research has shed light onto how the availability of mobile

communications allows for the psychological separation of physically present relations. Research has shown that pre-teens often use mobile devices during family gatherings leading to strained immediate relationships with parents

(Stafford, 2012). SDT would argue that the pre-teens may actually be fulfilling their needs, values, and interests best by participating in these communication practices if their main goal is to develop their social networks, however misguided the goal might be (Park, 2013). This research acknowledged that it is also often the parents that use their phones with the same result. Other research has highlighted that minors having mobile phones decreases the interaction that parents have with their children friends due to the absence of land line phone use (Srivastava, 2005). This is because when calling a fixed telephone there is no assurance of who is going to pick up. This leads parents to having less control and understanding of their

children's social lives. This is especially worthy of research because it is the family relationships that are often considered to be the conveyers of society and cultural values through their reproduction of stable and predictable elements of modern society. The institution of the family is responsible not only for the nuclear family but also the close social actors that interact with the family and derive meaning and social understanding from the family. When this connection is lost in both a direct and indirect way it is possible that culture and society will change rapidly from the traditional norms that have been adopted over generations (Hjarvard, 2008).

3.6 Benefits of Mobile Communications

Most of the research that this literature review has encountered has focused on the negative aspects of mobile communication in relation to face-to-face communication. This is most likely due to the prevailing moral panic surrounding the changes that communication is going through (Wikipedia, 2015). But that is not to say that there are not many positive aspects of mobile communications. Mobile phones allow for communication without the constraints of physical proximity (Billieux, 2012; Wellman, 2001; Park, 2013). Long distant relationships are able to be maintained allowing for people to travel and live where they desire without damaging important relationships (Stafford, 2012). Additionally, large social

networks are much easier to maintain due to SNS´s that are available through the mobile phone (Seo, 2015; Rettie, 2008). While some research emphasizes the negative impacts of not using fixed land lines anymore other research shows how the adoption of mobile phones increases the availability and amount of time that is spent speaking with family members due to ease of use and mobility (Liu, 2014).

Mobile phones also allow for relational maintenance with the ability to carefully cultivate correspondence how one sees fit (Billieux, 2015). This is especially beneficial for people that are not comfortable in social interactions that can have a limiting effect on people’s ability to express emotions. While the data that that this research project has collected does not address the time spent cultivating messages, the occurrence of SMS´s are much higher than phone calls. This literature sheds light onto why this might be. SNS´s in particular have been shown to allow for introverts to maintain social networks and gain self-esteem (Kuss, 2011). In other studies, it has been found that shy communicators feel more comfortable in mediated interactions (Stafford, 2012).

Contrary to Billieux´s 2008 research it has been found the increased use of communication tools by young adults is related to reduced depressive symptoms. This study found that young adults value close friendships and relationship

development, and that the use of SNS allowed for emotional support, trust building, and sharing activities that resulted in more intimate relationships (Subrahmanyam, 2008). If social activities are carried out through the phone during face-to-face conversations it could be beneficial for the participant using the phone.

Additionally, some research has shown that interruptions to face-to-face dialog is not necessarily perceived as negative. It has been demonstrated that when

individuals receive a text message, and discuss the message with their co-present partner, no relational damage occurs and co-present partners often can have a feeling of inclusion in the other relationship (Stafford, 2012). This research project will investigate how often interruptions are re-introduced into the conversation, and this may lead the findings towards different conclusions about the effects of

interruptions to face-to-face conversations.

For good or for bad the sense of belonging has been transformed from a physical space with social actors, to one’s communicative network (Rettie, 2005).

But this space potentially has simply moved online since research has shown that internet access and online discussion groups like Twitter and Facebook bolster community connections, though not as strongly as face-to-face interactions (Chen, 2011). These SNS´s allow for for larger and more diversified social networks that in turn should allow for a people to obtain more specialized attention to gratifications that are sought (Liu, 2014).

4.0 Data Collection & Analysis Methodology

This study was conceived from my personal experience of seeing an increased level of phone use in face-to-face interactions in my personal and professional life. I wanted to design a study that would allow me to see what people do on their phones, when having face-to-face conversations, as well as if what people did on their phones has anything to do with the present conversation. Although I have some previous experience with observing people using their phones while in co-present situations the research strategy that was used in this project is the Inductive research strategy. This strategy I believe is most useful because it allows me to overcome many preconceptions that I may have surrounding the issues of mobile phone use while in face-to-face conversation. Some of the literature review and supporting evidence draws upon the

Retroductive RS, but the goal of this research is to explain the uses; not to uncover the underlying motivations for such uses (Blaikie, 2007, p. 8).

The research projects general outline is the collection of data and then the drawing of general conclusions from the collected data. This has led me to undertake this research project using the research paradigm of Positivism supported by the naturalism doctrine (Blaikie, 2007).

With the guidance of my thesis advisor, Pille Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt, a structured interview was developed. It was decided that the date, time, sex, location, age, intensity of use, and atmosphere would be recorded, as well as five open ended

questions.

(1) What was your phone used for? (2) How do you know each other?

(3) How did the phone contribute to the conversation?

(4) How typical was this conversation in relation to the phone use? (5) Are you local or visiting?

The first question is intended to get a list of applications that the phone was used for, unrelated to why it was used. This was intended to get people to disclose as many uses as possible without reflection on what they were used for. The second question is aimed at revealing relation status. Viewed through the lens of Uses and Gratifications theory I will be able to discern if relational status is related to different communication objectives. The third question is related to motivations of use and allowed me to understand how and why the different applications were used. The fourth question was intended to get people to further disclose their communication practices with the goal of getting people to open up. This allowed me to get more information about how the mobile phone was used. The fifth question was included based on the belief that the phone may have different perceived affordances if the user is in an unfamiliar location.

The interviews have been conducted in Malmö, Sweden at cafes´ and bars where people often hang out with friends and acquaintances. The decision of who to approach was determined by if I observed people using a mobile phone while in the presence of one or two acquaintances. I limited the sample pool to this

demographic to attempt to get people when they are interacting with a specific person opposite themselves. Before approaching the research subjects, I observed how much time they spent on their mobile phones. I decided to group people into three groups comprised of low intensity users, medium intensity users, and high intensity users. I defined low intensity users as people that only occasionally

looked at their phones and when doing so did not interact with the phone for more than a 30 seconds. Medium intensity users are defined as people that interacted with their phones throughout the conversation but spent the majority of the time in conversation with the present person. High intensity users are defined as people that interacted with their phone constantly, rarely setting the phone down on table, and using the phone at least once every 2 minutes. The interviews were conducted in locations that I usually attend, and therefore the respondents are generally in the early adulthood age range.

The interview started with me approaching the observed group of people and telling them that I had a research project, with Malmö University, that had to do with how people use their mobile phones when out with friends. I then asked if they could help me out by answering a few questions. I directed the questions at the individual that I observed using the mobile phone the most. Without exception it was always the case that the research subjects answered together and discussed their answers between eachother. Interviews usually lasted between 3-5 minutes, sometimes with a longer discussion following the interview. Interview responses were recorded physically into a pre-prepared log book. The log book was

transcribed onto the computer the same or next day as to not lose any of the subtleties recorded in the log book.

Originally it was planned to audio record all conversations and then transcribe the conversations from Swedish to English. But due to the amount of background noise at bars and the intrusive nature of having audio recording equipment it was decided to keep a physical log book instead. This log book was carried with me for the duration of two weeks and interviews were conducted when the opportunity presented itself. My own biases about approaching people and asking about personal information was an interesting obstacle to overcome. I initially believed that people would be not interested in participating in such an encounter but have

been surprised in people’s openness to answering the research questions. One of the limitations of conducting the surveys with this method is the possibility of limited information disclosure by the participant due to not feeling comfortable disclosing such personal information to a stranger. I attempted to overcome this limitation by be as professional as possible and reassuring the interviewees that all the

information was confidential and anonymous.

A total of 40 interviews were conducted between April 20th, 2016 and April 30th, 2016. In total 82 individuals were interviewed. The 82 interviewees were between the ages of 19-45 years old and there were 52 women and 30 men. There were four separate group dynamics that were observed in the research. The first was two females in conversation labeled F/F, the second group dynamic was one male and one female M/F, the third dynamic was two male M/M, and the fourth dynamic was three females F/F/F. There was a total of 19 interviews with F/F respondents, eight interviews with F/M respondents, 11 interviews with M/M respondents, and two interviews with F/F/F/ respondents (Appendix A).

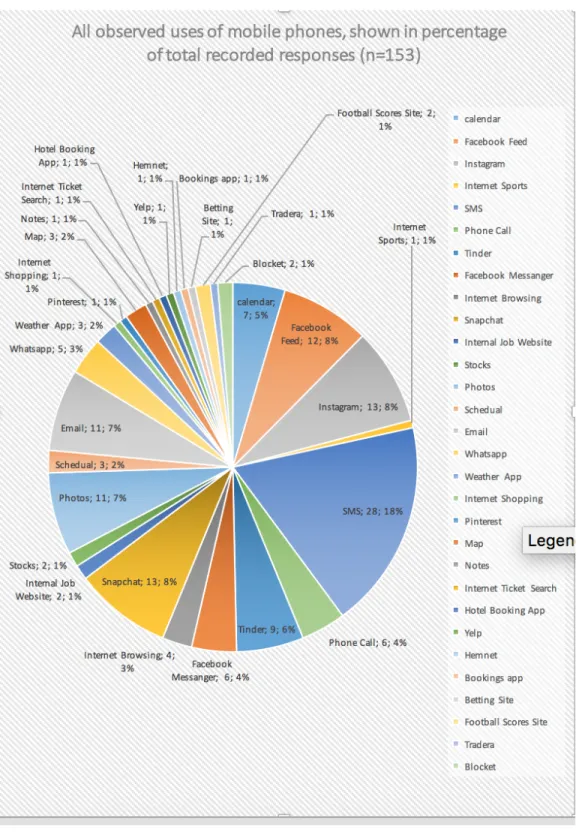

After the log book was transcribed into a word document the results to the first question were coded and numbered, giving 153 responses that were coded into 30 observed different applications that the mobile phone was used for. The 30 observed uses of the mobile phone are as follows.

1. Calendar (n=7) 2. Facebook Feed (n=12) 3. Instagram (n=13) 4. Internet looking up sports (n=1) 5. SMS (n=28) 6. Phone call (n=6) 7. Tinder (n=9) 8. Facebook messenger (n=6) 9. Internet (n=4) 10. Snapchat (n=13) 11. Job internal website (n=2) 12. Stocks (n=2) 13. Photos (n=11) 14. Schedule (n=3) 15. Email (n=11) 16. WhatsApp (n=5) 17. Weather app (n=3) 18. Internet shopping (n=1) 19. Pinterest (n=1) 20. Map (n=3) 21. Notes (n=1) 22. Internet ticket search (n=1) 23. Hotel app for booking (n=1) 24. Yelp- reviews app (n=1) 25. Hemet (n=1) 26. Google

auction site (n=1) 30. Blocket auction site (n=2). (See Figure. 1)

Figure 1. All observed uses of mobile phone shown in percentage of total

A limitation of the data set is both its size and distribution of participants. In future research I would like to have a larger data pool as well as more conversations documented between couples and family members. This would allow for more accurate comparisons between the ways in which different relationships affect communication patterns.

This research project has the aim of investigating what people do with their phones while multicommunicating. I have, based on my pre-existing assumptions and theoretical review, three hypotheses for the data that was collected.

H1- The majority of phone use will not be related to the face-to-face

conversation.

H2- Increased phone use will be related to phone use that is not related to the

face-to-face conversation.

H3- Friends will be most likely to use the phone for purposes of socialization

with non-present relationships.

5.0 Analysis

As Fig. 1 shows there were 30 distinct applications that mobile phones were used for in my study. This information shows the frequency of use, but does not say anything about the way in which the application was used. For example,

someone looking at Facebook can be doing this for entertainment purposes or they can be updating their status for social purposes. A phone call can be used for informational purposes, planning, or social purposes. For this reason, I pulled from previous Uses and Gratification research (Gerlich, 2015) and created five

categories of uses that the mobile phones were used for. I labeled these five uses (1) Entertainment- this is when a phone is used for the viewing of pleasurable material (n=17).

(2) Information- this is when the phone is used to look up information that is relevant to the immediate situation.

(3) Social- this is when the user actively reaches out to their social network and or responds to their social network (n=35).

(4) Pictures- this is when the phone is used as a picture viewing device enabling the owner to show images to their conversational opposite (n=10).

(5) Planning- this is where the phone is used for the planning of future events not occurring during the conversation (n=16).

These five categories correspond to the original four categories that Blamer and Katz laid out in 1974 (Curras-Perez, 2014, p.1480), with the addition of a fifth category of Planning. I decided to add this category because of the prevalence of planning related activities in my data (See Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Distribution of uses based on Uses and Gratification categorizations (n=89).

I categorized the uses by going through the transcripts and coding for the way that the specific applications were used in each conversation. I did this so that the uses of the phone would be more accurately shown instead of just the labelling of the specific function that the phone was used for.

This grouping of the different uses gives a more accurate description of what phones are used for in face-to-face conversations. In total the conversations showed there to be 89 distinct uses. The distribution shows that people us the phone primarily for social (39%), followed by entertainment (19%), planning (18%), information retrieval (12%), and showing of pictures (11%). This distribution

17; 19% 11; 13% 35; 39% 10; 11% 16; 18%

Distribution of uses based on Uses and Gratification

categorizations (n=89)

supports the Social Capital theories assertion that social networks are primarily used for satisfying psychological needs, in this case the need to socialize (Chen, 2011). Uses and Gratifications theory would say that people have a need to socialize and have found a medium, the cell phone, that allows them to fulfil this need (Gerlich, 2015).

5.1 H1- The majority of phone use will not be related to the face-to-face conversation.

Hypothesis 1 was analyzed by comparing the total number of stated uses vs. the amount of applications that were used to assist and or discussed in the

conversation. In total there were 153 independent uses stated by the 82

respondents. Of the 153 states uses 40 were used in direct relation to the face-to-face conversation. Additionally, there were 30 uses that were not related to the conversation but were discussed afterwards with the conversational partner.

Fig. 3 Distribution of the total stated uses in relation to if use was related to the conversation (n=153).

30; 20%

83; 54% 40; 26%

Uses of Phone Related to Conversation (n=153)

These figures support H1 as only 26% of stated uses were directly related to the conversation and an additional 20% were discussed afterwards. This figures show that the majority of phone use is not related to the conversation at hand. This can be related to the mediatization research on social change, and how the mobile phone is requiring more space in the social arena. This data demonstrates the four processes of how mediatization is affecting social change. The data from Fig.1 and Fig. 3 show that people are communicating without the barriers of location and time, that the mobile phone is substituting face-to-face communication with mediated forms, that people are multicommunicating, and that social norms have changed to allow for all of these processes to take place (Schulz, 2004). However, these numbers may not accurately reflect the duration and intensity of use of the individual applications. Thus potentially minimizing the actual time spent on the applications that were associated with the conversation.

To visualize the way that the mobile phone was used in the conversation I coded the information into dialogue maps. The dialog maps start with a blue circle representing the face-to-face conversation and then an orange circle representing how the phone was used within that conversation. The phone can be used either in direct relation to the conversation or as an un-related activity. If the phone is used for an unrelated activity, it can either stay as an unrelated activity or can be

reintroduced into the conversation. I observed seven distinct dialogue maps within my data sample (See Fig 4).

(1) The phone is used for unrelated purposes; some uses are re-introduced and some are left personal. (n=3)

(2) The phone is used for unrelated and related purposes; the unrelated uses are re-introduced. (n=2)

(3) The phone is used only for unrelated purposes; all uses are re-introduced to the conversation. (n=7)

are not reintroduced. (n=17)

(5) The phone is used only for related purposes. (n=5)

(6) The phone is used only for unrelated purposes; the uses are not re-introduced to. (n=3)

(7) The phone us used for unrelated and related purposes; the unrelated uses are re-introduced and left personal. (n=3)

Fig. 4 Seven distinct dialogue maps relating to the way that mobile phones are

Fig. 4 shows that there is a diversity of ways that the mobile phone is used in social settings and that unrelated uses of the mobile phone are often re-introduced into the conversation. When the data is presented in this manner it shows that the mobile phone was used in relation or re-introduced into the conversation in 37 out of 40 interviews. This can be seen as evidence of the mobile phone supporting conversations and potentially adding to the quality of the face-to-face conversation (Stafford, 2012). This information goes against H1.

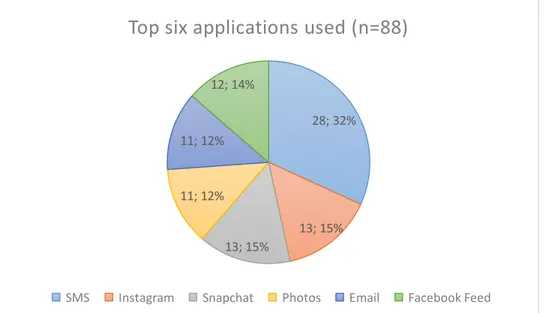

Another way that I have tested H1 is to look into the most occurring uses of the mobile phones. The top 6 uses for the phone were the Facebook Feed,

Instagram, SMS, SnapChat, Photos, and Email, in total accounting for 88 individual accounts, resulting in 58% of the total recorded responses. As the Fig. 5 shows there is a fairly even distribution of around 15% for five of the six applications, with SMS´s accounting for 32% of the distribution.

Fig. 5 Top 6 uses of the mobile phone accounting for 58% of the overall uses (n=88).

28; 32% 13; 15% 13; 15% 11; 12% 11; 12% 12; 14%

Top six applications used (n=88)

Given that the mobile phone has potentially an infinite amount of applications it is interesting that there has been such a dramatic consolidation of the

applications that are used by the research subjects. This may be the result of the fight over people’s attention that Hjarvard emphasized in his mediatization

research (Hjarvard, 2008). Only one participant mentioned time restraints as a motive for using their cellphone while in conversation, this corroborates the findings that time restraint is not linked to socialization practices (Seo, 2015). This research stated that with the abundance of information currently available political and

commercial actors will fight to have control over people’s attention. The data shows that people have largely conformed to using Instagram, Facebook, and Snapchat for their socialization and entertainment needs.

The use of these six applications were stated as being related to the

conversation at hand 16 times in total, meaning that they were only directly related to the conversation at hand 18% of the time. The outlier in this grouping is the use of the phone as a picture viewing platform. 72% of the time when the phone was used to show pictures were directly related to the conversation at hand. This I think is because the phone is being used in a different way. When showing a picture, the phone us being used as displaying device instead of a mobile communication device. The phone is then being used more like a physical artefact of one’s life instead of a connected device enabling communication. This is a very clear demonstration of the multiplicity of affordances that the mobile phone has (Hjarvard, 2008, p. 121).

When the different data analyses are compared to each other the evidence shows that H1 is overwhelmingly supported. The majority of phone use is unrelated to the conversations at hand.

5.2 H2- Increased phone use will be related to phone use that is not related to the face-to-face conversation.

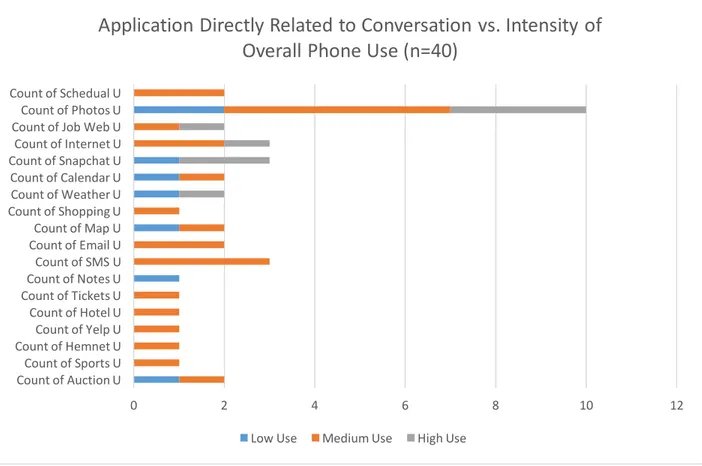

H2 was analyzed by comparing the applications stated to be used to aid the conversation, to the overall intensity of phone use. I hoped to find out if the

intensity of use was related to applications being used to aid the face-to-face conversation. In total the data shows that there were 10 conversations labeled low intensity, 21 conversations labeled medium intensity, and 9 conversations labeled high intensity. There were in total 18 uses of the mobile phone that were stated as being directly related to the conversation at hand (See Fig. 6)

Fig. 6 Applications directly related to conversation in relation to intensity of phone use by conversational partners (n=40). 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 Count of Auction UCount of Sports U Count of Hemnet UCount of Yelp U Count of Hotel U Count of Tickets UCount of Notes U Count of SMS U Count of Email UCount of Map U Count of Shopping UCount of Weather U Count of Calendar U Count of Snapchat UCount of Internet U Count of Job Web UCount of Photos U Count of Schedual U

Application Directly Related to Conversation vs. Intensity of

Overall Phone Use (n=40)

Fig. 6 shows that there were 40 individual confirmed uses, assisting the conversation, distributed over the 18 applications. This figure is shown to demonstrate that there is a wide variety of applications that are used when in relation to the conversation. This suggest to me that the most occurring

applications are not used to aid conversations but rather it is specific applications that can give relevant information that is sought out to aid in conversations. Six of the 18 applications were only named once as being directly related to conversation and 17 out of 18 applications were cited by three or less conversations as being relevant to the conversation. Again the outlier in applications relevant to

conversation is using the phone to view pictures which was cited by 10 conversations.

When looking at the applications, that were used directly in relation to the conversations, there are 12 (Auctions, sports, hemnet, yelp, hotel, tickets, map, weather, email, shopping, internet, and calendar) out of 18 that can be considered information retrieval applications (See Fig. 6). This suggests that applications that are used to assist conversations are often applications that allow for the retrieval of information specific to the conversation at hand, instead of applications that allow for socialization or other functions. It appears that the use of these applications is related to being primarily focused on the face-to-face conversation. This makes sense if Self Determination theory and Social Presence theory are taken into account. By being present in the conversation people are more likely to be attuned to the goal of socializing with the person opposite them (Warren, 2003). This in turn leads people to using their mobile phones for purposes related to the conversation, instead of the automatic actions of using the phone for entertainment and

socialization that are related to lower conversational quality (Bayer et al. 2015). By using the phone as an information retrieval tool people are demonstrating that they are involved in the conversations and seek to use the phone to compliment the

conversation.

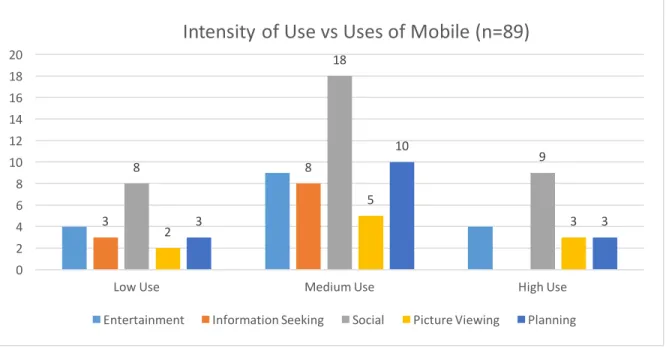

When the uses of the mobile phone are compared to the intensity of use the data shows that all groups use the phone most for socializing followed by

entertainment purposes. Missing is the use of the phone for information retrieval in the High Use group (See Fig 7).

Fig. 7 Intensity of use compared with the Uses and Gratifications categorization (n=89).

This suggests that conversations where the mobile phone is most prevalent are not using the phone for information retrieval, which is highly associated with being relevant to the conversation at hand. This shows that the conversational partners that are in High Use groups are experiencing an “absent presence” (Gergen, 2002 P. 227, Rettie, 2005), and are potentially demonstrating symptoms of PMPU (Billieux, 2012). If the goal of meeting up with friends is to socialize and develop meaningful bonds, as Social Presence theory states, then the High Use

3 8 8 18 9 2 5 3 3 10 3 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20

Low Use Medium Use High Use

Intensity of Use vs Uses of Mobile (n=89)

participants are using their phones in a way that is not congruent with Self-Determination theory and therefore exhibiting signs of compulsive use.

Taking into account the previously mentioned analyses, it is concluded that the data supports H2 that increased use of the mobile phone during face-to-face conversations is unrelated use.

5.3 H3- Friends will be most likely to use the phone for purposes of socialization with non-present relationships.

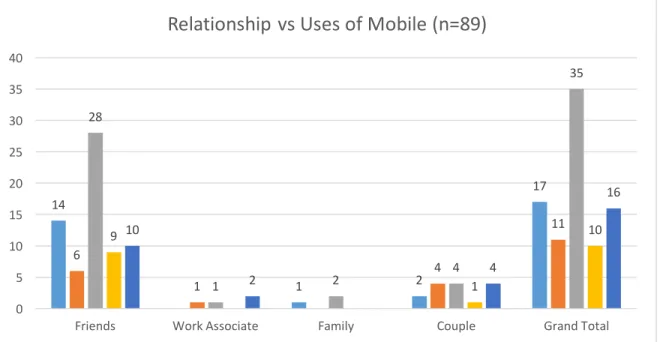

By comparing the relationship of the conversational partners to the uses of the mobile phone I was able to determine how the different relationships affects the uses of the mobile phone. Again the data from Fig. 2 shows the distribution is as follows: Entertainment (n=17), information retrieval (n=11 social activity (n=35), picture viewing (n=10), planning activities (n=16). The distribution of relationships is 30 friendships, 3 work colleagues, 2 family members, and 5 couples. Fig. 8 shows when these two sets of data are combined.

Fig. 8 Relationship of conversational partners compared with Uses and Gratifications classifications (n=89).

This comparison shows that work associates are likely to use the phone for information retrieval, planning activities and social contact related to the

conversation. Family members are likely to use the phone for entertainment purposes and socialization. Couples are most likely to use the phone for planning, information retrieval, and socialization. And friends have a representation

distributional of the total data, this is due to the majority of respondents affiliating with the friendship category. The data shows that work associates, family

members, and couples are less likely to participate in “phubbing” (Angeluci, 2015, p. 174), but there is not a large enough data set to realistically expand these findings beyond this study. Therefore, this research project cannot confirm or deny H3.

When the group dynamic is compared with the Uses and Gratification classification some interesting trends emerge. The data collected shows that the

14 1 2 17 6 1 4 11 28 1 2 4 35 9 1 10 10 2 4 16 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40

Friends Work Associate Family Couple Grand Total

Relationship vs Uses of Mobile (n=89)

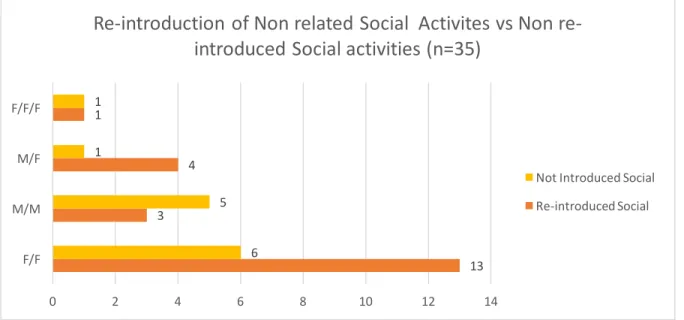

40 groups are divided into 19 groups of two female’s F/F, eleven groups of two male’s M/M, eight groups of one female and one male F/M, and two groups of three female’s F/F/F. Fig. 9 shows the relationship between group dynamics and Uses and Gratification classifications.

Fig. 9 Group dynamic of sexual orientation compared with Uses and Gratifications classifications (n=89).

This comparison shows that F/F groups are very likely to participate in socialization activities and very unlikely to participate in information seeking. As information seeking has already been correlated to mindfulness, and Self-Determination theory, it appears this group may have different underlying

motivations for coming together for face-to-face conversations. It could be that F/F feel a stronger attachment to non-present social groups and have a stronger feeling of “always availability” (Park, 2013, p. 182). Research has shown that multicommunicating can have a positive effect on face-to-face communication satisfaction if the communication partner later converses with the co-present individual about the multicommunicating (Stafford, 2012). When this information is taken into consideration, and the frequency of re-integration of socialization

10 2 3 2 1 5 5 18 9 6 2 4 3 2 1 8 2 5 1 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 F/F M/M M/F F/F/F