Nr 166A - 1981

Statens v'ag- och trafikinstitut (Vl'l) - 581 01 linkoping

ISSN 0347-6030 National Road & Traffic Research Institute - S-581 01 Linkoping - Sweden

Public transport in the era

of the automobile

PUBLIC TRANSPORT IN THE ERA OF THE AUTOMOBILE

Condensed version of a report in Swedish titled

"KOLLEKTIVTRAFIKEN I BILSAMHALLET".

Kenneth Asp, Swedish National Institute for Road and

Traffic, Linkoping,

Olof Lundin, Department for Human and Economic

Geo-graphy, Goteborg University.

Report sponsored by Swedish National Institute for

Road and Traffic, Linkoping, Sweden.

vw.

,w?

'

4

Contents

Page

1 BACKGROUND 1

2 SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION OF DWELLINGS AND WORK 3

PLACES

3 PRIVATE CAR TRANSPORTATION V. PUBLIC 6

TRANSPORTATION

3.1 The family car concept 6

3.2 Main trips 14

3.3 Long distance travelling 22

3.4 Can public transport substitute private 25

car transport?

3.5 Travelling time and distance I 26

3.6 Travelling hour by hour 34

4 AN ALTERNATIVE WAY OF STUDYING TRAVEL 37

BEHAVIOUR

4.1 Demand and supply 37

5 MAIN RESULTS 48

Literature

ABSTRACT

This report-studies a travel survey implemented by the

Swedish National Central Bureau of Statistics in 1978. It structures vital results from the travel survey into a frame of transport policy aspects where balancing between public transport and own car transport is put

in focus.

Long term travel consumption is stimulated by urban

sprawl and separating work places and dwellings. These

trends are made possible by widespread car ownership (50 % of single persons and 90 % of married couples owns a car in Sweden).

Work trip constitute 37 % of the total number of trips but only 21 % fo transportation output. Recreational trips correspond to 29 % total tripnumber but 45 % of transportation output. Earlier estimates give higher rates for work trips and lower for recreational

purposes.

In cities work trips are more often made by public transport but this partly leads to low rates for walking and cycling. 59 % of schooltrips are made by public transport making them constitute 15,6 % of total number public transport trips. The number of car passengers for work trips nearly equals that of work trip public transport passengers. This makes ride sharing nearly as inportant as public transport. Generally speaking low use is made of public transport except in big cities. Improvements would therefore become costly (without giving more revenues). Those who prefer going to work in their own car are often

saving a lot of time which makes public transport unatractive to them.

II

Transport policy debate in Sweden overstresses big city aspects. This makes traditional public transport

solutions unduly attractive. The report prefers more research and practical experiment with semi public transport solutions (eg para transit). Thats why the report raises the question if public transport of the present design is not on the wrong track.

PUBLIC TRANSPORT IN THE ERA OF THE AUTOMOBILE SUMMARY

During the years 1976 to 1978 the National Swedish Road and Traffic Research Institute (VTI) participated in an ad hoc working group which designed and planned a survey of Swedish National Central Bureau of

Statistics (SCB). When results from the survey started

to arrive in the autumn of 1979, VTI decided to ask Olof Lundin (of the Department for Human and Economic Geography, Goteborg University) to make a report on the material. The report has been co-authored by assistant professor Kenneth Asp of the VTI.

The report contains the vital results from the travel survey. It also tries putting the results into a frame of mainly transport policy aspects relevant to problems around public transport versus own car transport.

The travel survey of the SCB is built upon a stratified random sample of 8 500 interviews made by SCB. It refers to the crucial dilemma of furnishing peOplev thenlada ate transport supply without letting this lead to unduly

financial consequences for the community as a whole. Growth of private car owner-ship has hollowed out the base for public transport and has made it difficult for the community to maintain the standard of public trans-port supply.

The report points at the longterm consequences on travel consumption of urban sprawl and the separation of

housing and places of work. Transportation output by all modes of public transport has doubled since 1950 but transportation output by private cars has increased

8-fold in the same time. Urban decentralization and

IV

deconcentration have characterized the pattern of

housing the last three decades. It would thus be extre mely costly to supply these sparsely built up areas with public tranSportation e.g. if an acute energy

shortage would emerge.

The travel survey studies some back-ground variables. From these the report concludes that most families

consisting of a married couple (living together) owns

a car. Only about 50 % of singles are car owners, nearly 90 % of married couples owns a car and practically all married families with children are car owners. Young people without occupation living in greater cities and old age pensioners are seldom car owners. No geographi-cal differences like that are found among families with children; more than 85 % of them living in big cities

are also car owners.

In the survey the so called main trips are at the focus of the study. Trips to and from work comprised 37 % of the number of trips but result in only 21 % of trans portation output. Recreational trip purposes comprises 29 % in number but raise to 45 % of transportation out

put. In other words, work trips are rather short and

they don't correspond in transportation output those shares given to them in other estimates made previously. In a corresponding way previously made surveys have

underestimated the transportation output for recrea tional purposes.

Work trips are more seldom made by own car and more often made by public transport in cities. Outside cities more people are walking or cycling to and from work. Business trips are modally dominated by the car.

Shopping and similar service trips are equally parted

between own car travel and walking/cycling. Trips for recreation and social visits are also modally halved between walking/cycling and car travel in most areas.

Among trips by_public transport work trips are the most

usual purpose (45,4 %) but school trips are second

(15,6 %) partly due to abandonment of small, local schools in the country side in other than the lowest forms. Work trips are also vital among trips made by car drivers and car passengers (respectively 38,3 % and 25,6 %) but for car passengers visits and recreation together comprise 40 %.

If you spread the total number of trips on trip purposes

the low number of trips by public transport changes the

image of the picture (only 13,9 % of total number of\

trips are made by public transport).

0

Work trips are made in 68,2 % as a car driver, in 14,6 6 as a car passenger and in 17,2 % as a public transport passenger. This means that ride sharing by car is almost as significant as public transport. But contrary to

work trips, school trips are made by public transport to a very significant degree (59,0 %). One can also conclude that public transport is more or less a city phenomenon since 41 % of all trips made by public trans-port relates to the capital region of Stockholm.

Long distance trips are dominated by car travel.

Trips less than 2 kilometres are dominated by walking and cycling. Increasing the distance means sharply falling rates of walking and cycling. Over 5 km own

car travel generally takes 3/4 and public transport 1/4.

Parts of the modal split attributes to dwelling struc ture and the standard of supply of the public transport. Greater communities, and especially cities, have large rates of lodgings in large houses with more than one family. These areas have often a rather good public transport supply as well regarding distance to bus stops as regarding time-table density. Only in great VTI-REPORT 166A

VI

cities and especially in Stockholm the public transport rate is high. High rate public transport also consists mainly of work trips. For those who prefer going by car to work their gain in travel time is often of great significance. More than half of them are now claiming one-way trip times of less than 20 minutes compared to an estimated public transport one-way trip of 60 to 90 minutes. Most of the car travellers are seeming to have

legal right of deducting car mileage money from their income for their work trips. This is allowed in Sweden if you spare at least 90 minutes a day on going by car to and from work (two-way-trip).

Public transport has two definite work load humps in the morning and in the afternoon. Total trip schedule however, has a bell formed soft top at lunch and a much greater intensity after 6 p.m. It is difficult for

public transport to gain more passengers other than for

work trips and school trips, where it is rather attrac tive. For work trips and school trips it is now however rather heavily strained and additional passengers would mean that it would be necessary to put in more buses,

drivers etc.

In one chapter the report outlines tranSportation needs of different socio economic strata. That leads to no definite recommendations for which public transport would be suited. This approach is in contrast to tradi-tional thinking claiming that denser time tables and more bus lines automatically gives public transport new passengers, and in the report the enormous cost in

creases that would follow suit are pointed to. To make matters worse revenues from public transport are now-adays very scarce. This depends on the widely used low cost-unlimited-numbers of-trips-tickets valid one month. Attractive schemes therefore seldom leads to

increased revenues. Moreover the amount of tax subsi-dies to public transport are now so great that it is VTI-REPORT 166A

VII

politically difficult motivating increases in subsidies.

Perhaps a solution is to be found among those semi

public forms of traffic called paratransit. Research and practical experiment around this should be stimu-lated.

One can conclude that the travel survey implemented by the National Central Bureau of Statistics gives a lot of ideas which should be contemplated. People in Sweden are as a whole totally dependent on their own cars for supplying their needs of travel (perhaps not counting city inhabitants). In the cities public transport rates are higher but the rates of walking and cycling in

those areas are low. City aspects of Swedish transport policy are evidently overstressed. This often leads to recommendations of traditional puclic transport solu tions even in those areas where they are not attractive. Tax subsidies for public transport are so great that no more stimulation of travel habits are to be expected. Energy reasons are also hampering such a stimulation, especially in those parts of the country where public transport is not attractive. In those areas people generally don't use their public transport supply to a greater extent even though the supply might seem at least theoretically to be of a good standard.

That is why the report is asking if public transport of present design is not on the wrong track.

1 BACKGROUND

During .1978 'the Swedish National Central Bureau of

Statistics (SCB) made an extensive survey of Swedish

travel behaviour and volume. The National Swedish Road and Traffic Research Institute (VTI) has taken a

con-tinuous part in planning, implementing and analysing

this survey. When, in the beginning of 1980 computer tables from the survey started to emerge, VTI engaged

Olof Lundin. (MA) (HE Goteborg University to :make a

detailed study of the results. Work has been carried out together with assistant professor Kenneth Asp cf the VTI.

This report is an abridgement of a report in Swedish

entitled "KOLLEKTIVTRAFIKEN I BILSAMHALLET"

(VTI-rapport 166). It tries to structure main results from the travel survey into a context of transport policy

reasoning. Of special interest is the problem of

private car transport v. public transport. During the late 1980 and early 1981 most computer tables from the travel survey will be published by SCB together with an analysis around sampling problems etc.

Sampling surveys are often used to analyse

trans-portation. In Sweden sampling technique is IHKXi now adays to produce statistics regarding truck transports

and in 1975 there was a sampling survey coupled to

home interviews concerning long distance travelling.

British and Finnish Travel Surveys had produced

inte-resting' results and it was subsequently' decided to

make the Swedish Travel Survey based on a sample of 8

500 people who were interviewed at statistically

representative days. All trips more than 200 m of the

day before were to be included together with back

ground variables such as car ownership, age, family

structure etc. From a scientific point of view both

the Swedish travel survey and its foreign counterparts

should be repeated at periodic intervals (e.g. every

five year). If so, one could reduce the volume of the

survey both by reducing the sample and its regional

and socio economic splitting just to make it possible to carry out. We think results from periodic surveys could become extremely interesting by not only giving a snapshot view of travel pattern but also describing the dynamics of its evolution from time to time.

This report tries to make a fair overview of

inte-resting results from the Swedish Travel Survey of 1978

(IRRJ -78). When. comparing automobile transport. with

public transport we often use a social cost perspec-tive instead (n: a pure firmbased commercial view. To

achieve a corresponding tax base modern transport

policy of EurOpean nations are often pricing the traf

fic via some kind of marginal road cost principle.

Pricing should then be based on the cost for the soci-ety of supplying or tolerating the actual transport. Citizens on the other hand have a right to demand a certain transportation standard even in remote areas. However, costs for subsiding public transport both in remote areas and in cities have accelerated vigouri

ously. Therefore it is essential that transport

ser-vices subsidized by the society are not overused, that

is people going e.g. by bus when walking or cycling

would have been healthier both for the individual and the society.

2 SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION OF DWELLINGS AND WORK PLACES

Dispersed housing generates more travelling than con

centrated dwelling structures. Large factories and

other work places impressed by scale economies also

leads to more travelling (as well as more goods

trans-port). In Sweden post World War II decades have in

volved bgth these trends, i.e. dispersing the housing

and concentrating work places, and have subsequently meant an enormous increase in passenger transportation

output (see figure 2.1).

100 100 90 " 90 80 -' I 60 7O 70 60 ' 60 Persoan 50 - 50 40 " " 4O 30 " ' 30

0 I

sparvag, T- bana. buss, sjbfart, luftfart .

I 0

J rnvdg

I l I T l

Ar1950 1955 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980

Figure 2.1 Domestic transportation output 1950-1980,

(bill pass km).

Source: Swedish Ministry of Transport Gov.

proposals to Parliament.

Legend: Personbil = car

Sparvag, T bana etc. = Trams, U-ground,

bus, water, air

Jarnvag = Railway

This increase stems :mainly from. wide spread owning (and using) of cars. Owning a car is often a necessary requirement to be able to migrate to more dispersed areas of dwelling, but car ownership is certainly also

influenced by increased living standard in general.

However, intensive car traffic causes noise and

ex-haust emissions, and not least a lot of accidents. For

these reasons jpublic transport. is increasingly'

sub-sidized and stimulated, while car transport is

re-stricted. Vast efforts are made to estimate complete

social costs for car travelling but little research is

focused on both costs m benefits of car traffic.

Perhaps that is because social benefits are even less prone to measurement than social costs.

Anyhow, supplying regions with good public

transport-ation is difficult. This is often due to the fact that

functional regions tends to be asymmetrical with

regards to their centres of work. Swedish so called

A-regions, which contain local working markets are a

good example of functionally arrondated regions. A

majority of these are asymmetrical (see figure 2.2).

K174

A

A

Symmetrically Asymmetrically

located region center located region center

Figure 2.2 Region form and center location

Summarising the current tendencies of dwelling dis persal and work place concentration one can conclude:

Current tendencies in dwelling shows a long per-spective dispersal, generating many and long trips to and from work.

- Current trends in work. place location are

con-centrating these, generating longer trips to work.

- Forms of functional regions are often asymmetrical

making it difficult to supply them with public

transport.

- Current trends towards every family owning a car

make people less prone to use public transport.

PRIVATE CAR TRANSPORTATION V. PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION

3.1 The family car concept

Increased and general car ownership has caused greater

mobility but also problems concerning noise and

ex-haust emissions, especially in city areas. Public

debate is often initiated in great cities and mass

medias have duly concentrated their debating efforts regarding traffic on the problems with the car. Conse-quently they have also stressed the good sides of pub

lic transport praising the virtues of dense, attrac tive public transport giving equality between sexes,

equality between social strata, good environment,

fewer traffic accidents. Of lately stress has been put upon energy arguments in general and sometimes

especi-ally advocating electric means of transport like

trains and trolley buses.

All these arguments are very much aimed at dense popu

lation structures. In a country like Sweden with 8

mill. people on an area the size of France (more than

50 mill. inhabitants) and with only one large city

area (Stockholm) such arguments would objectively seem lopsided or biased, but leading mass medias are con centrated to Stockholm. Evidently public debate on car

traffic nationwide has been unduly influenced by city

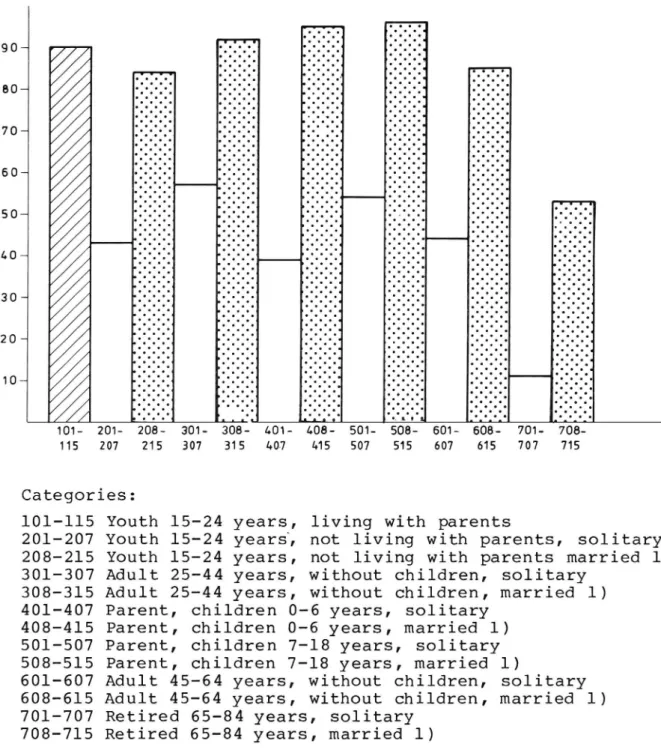

arguments. But how widespread is really car ownership? Figure 3.1 gives a hint.

:2 7

/

z

/

/

00001 a a o _1 I o o o I I o o a 4 I o o o 1 I o o a 1 Ioooq ' I I I I I I I I p.000! D I I I U I I I I I boo-q I I I I 1 I I I I 1 I. a o o 1 I o I o 1 n I o o 1 o o o o 1 0001 0000 poo.D I I I I o L

201-207 203- 301- 566: 401215 307 315 407 Categories: 101-115 201-207 208-215 701-707 708-715 Youth 15-24 years, Youth 15-24 years, Youth 15 24 years, Adult 25 44 years, Adult 25-44 years, Parent, 408-A15 501- $06- 501- Sbéi515 701-707 76m: children 0-6 years,

living with parents

not living with parents, solitary not living with parents married 1) without children, solitary

without children, married 1) solitary

Parent, children 0-6 years, married 1)

Parent, children 7-18 years, solitary

Parent, children 7 18 years, married 1) Adult 45 64 years,

Adult 45 64 years, Retired 65-84 years,

without children, solitary without children, married 1)

solitary Retired 65-84 years, married 1)

l)Married or living together under similar circum-stances. This is valid for all figures.

Figure 3.1 Socio-economic

VTI REPORT 166A

Figure 3.1 shows a distinctly higher car disposal among

married persons (dotted) than among solitary persons.

Youths living with their parents are separated by a

different striping since for them car disposing is not

"of their own". One in two solitary people dispose a

car, nine in ten married persons dispose a car. This is a much higher degree of car disposal than might theo retically (randomnally) be expected (3 in 4).

Car ownership, however, is not evenly spread from a spa tial aspect. To study such things we have to introduce a concept called T-regions. They are mapped in figure 3.2

FARDMEDELSFURDELNING BEROENDE PA T'ATORTSTORLEK Mu XVIII \ K\ W ll ' /

OZ // // A//// /'X //, 2'50 / . . /V J/

055 1 l 3

1L 30134 4% | 45

25 500 0 2 .. 2 SCI] 1 [m TUSENTALs IN-A

l-GLESBYGDéf TATORT )1 v NARE '

I \ smunu

[1|'l'rrlll'I'IIIIACKUMULERAT \ AC

3 5 6 7 8 ANTAL INVA-NARE; MILJ. ('\. \<\\ 0mm

\ T- Peron ,/"\~/ \

re : 'Tq ' T5 W1"1

\ ~0115m -\ \\ Y owsmwsvu \ 0 35 ND SOHU'VU . Z . s u \ O / s )/ Canto 3 / V J I / "MOSA IO { - Hung \ A \ SUJIDSVAU. \ ~ \ ~ I \d J I < / . ._ _) Ouusm-\ \K / mama .\- _ \ J . A x \ B I \\aou~ns O xow- m - J O was: \ \r \\ \ o«m \\ N ' \ w SAND'vag 5 "

\. \\own. un: -U". ) man 5w! xun S

. \ ' I .Mo vol-{mans I OII \ °" 6 msu j k) H V . h uncuau' m .. Q ) I /

nurouso ). I wantALA1 C ( O

LlS lVll ._J \ .V um) O UPPSALz \

1(- 0 1111 s : bummer. ) NPMWBLJ V SY/( R zsl 5v. __/ Own-u. u _ nnu mouuvcLA I!, . \ O " 1 \ unooronum !~O \O m. gsf\h p A ' ' ususxocno no _ at 5! H slow I "90 Q'D IILIA (.uslnslllc

/ itsxnswun ( _ 116m: \\ 'y x \ amount QIALR . NUHIKJEI UUOEV...LL S sounmvnc LIAOIPIK;

5 /( mommqu 5x vot ~:;ON° ' - mun:I

SHNWS u 0 P lililIL-O [9 V E O: u\ @kmusf vk r \ f\ \ \ L L . n l _ .unnm ( LU-L3 BO S La? JONKOPML 00 ; 0 Hanan nab

O / 35.1 ( Om'm m / F O r \ (0'; . 1 H unusc N I r . I» .S . L \ uuluru. r~

\ G O - FEDNS BLUL U "-KIGIONUU H SIJCKKC LJ My NRORHP

: b "30'. AIL-Lo. Deana, ugly,

SDulh uhl. Wl. uPldiCX-VISBL

(NOE-ii}, ungu. uuu'aL us

'ii-nncl. AliliSHPJ I H

N _

S

12 QUEBDRL l\ib VCROHUI masons, IOU..th uoa'onv. nu 30-1. nau-w. uni-m n n :3 1:10:11 > 25 DOC IWA:.A2E I. HIJEIER 5 036 ~ 2') 0011 11w . - 2 30: 1M 00 .4 l Sin-v1 S-EHLL 'Jrigi 20' \l i :H.Hpnn; M v, I' 2'. if.» 0% 73' x 1 7" '., u - )IiviJ

Figure 3;? T-regions in Sweden.

T-regions or transport regions are classified according

to number of inhabitants in their urban area. T1 is

Stockholm and its urban suburbs (see map). T2 is Gote-borg correspondingly. T3 is constituted by all other ur

ban areas with more than 25 000 inhabitants (based on

parishes as subareas). T4 is urban areas between 5 000

and 25 000 inhabitants. T5 is urban areas 200-5 000

in-habitants and non urban areas in southern Sweden, while

T6 is the corresponding areas in northern Sweden (see

map). T5/T6 are separated since one can assume that

northern Sweden with vast, very sparsely populated areas

has a different transportation pattern than southern

Sweden.

Perhaps one should stress that regions T3 to T6 are not areas as such but are stratas of internally homogenous areas. T1 and T2 on the other hand are areas of their own. From the figure you can see the proportions of Swe dish inhabitants in each T-region. Work trip modal

rela-tions are also mapped (from an investigation made in

connection with the census of 1975).

Now return to car disposing, this time including spatial relations (figure 3.3).

VTI REPORT 166A

Figure 3.3 Car disp051ng,

types of family.transport regions and

71,73

44,54,45,55

Retired (65 + years) Parents, married

42,52 Parents, solitary

marriedAdults 25 64 years,

33, 63 no children,

Adults 25-solitary

their parents, married

31, 61 64 years, no children,

23 Youth 15-24 years, not living with

their parents, solitary Legend

21 Youth 15-24 years, not living with

°/.iurVo| 7 8 6 L L 5 232221 (212219151212 151618171318 533322 22222L292928 21 21 22 23 26 28 LL,LS,SL.SS 60 50 L0- 30- 20-10 70-1 80-90-1 100 00 0. 00 u0 n0 n0 n0 n0 n0 n0 n0 m0 n0 n.».n0 >0 w v.. . .C. n . n . . . R. .. .0 . 00 u. u0 n. no u 0. 0 .0 .. . .0 .. .0 .. .0 0. 0. .. 0 .0 n . . 0 . . T1 T1 T2 TI. T5 T6 1 . . . 4 -. . . . . 4 . . . . . . . . . .. 00 00 00 00 .0 .. 0. 00 00 .. .0 .. 0. .0 00 .. 0. .0 .. 0 0 0 0 0 0 . 0 . . 0 0 . . . . . 0 . 0 0 . .0 .0 . .0 0 0 00 .0 .0 00 0 0. .0 .0 .0 .0 .0 . 0 0. .0 0 0 . 0 O 'O OQ .. I D DO . I I D D0 00 0. .. .n . . .. 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 4 0 0 0 6 0. 4 0 0 0 . 00 00 0000 .0 00 00 00 09 00 00 00 00 0 09 00 00 0 0 0 T1 T2T3 Tl. TS T6 3 . O O . .. u. n0 . p 0 o 1. U D . C O O O C O 0 .. 0 . .o .. .. .0 0..0 0. .. 00 .0 00 0£. 00 0. .. .0 0 00 .0 0. .. .0 .. . 0 0 0 0 . . . . . . 0 0 0 0 0 . 0 ¢. . . 0 0 . . o 00 . . 0. .. .. .. .. 0. .. 0. .0 00 0. 00 5 0 . 5 1 . 0 0 .0 00 .0 0. .. 00 0 0. 0 . . . . . . , 0 1 . . . 0 0 m . . 0 9 0 . . . .

0 0. .

1 1 c 4 G 1 l Q 1 1 l 1 1 Q . 1 O . .. ,. ,. . .. . . . 1 . . . .9 .. . .uu 31+61 .0 .0 .. . .0 . n. 3.. 0 .0 .0 .u. .. .. 0 0H 0N 0" .. . 0. .. .. . T1 T2 T3 TL T5 T6 .4 . . . . . ... c u. . . c. 0. 1 O. .. 0. .. .. .O tI OD OOI. .G O. .C O. 0. . '0 . .. .. .. . 0 00 .. .. .. 00 .. 0. .0 0. 0. 0. .. . 0. .. 0. .. . . 3. .. : .0 .0 .. .. .0 .. .. .0 .0 01 0. .... . .4 03 .. .. .0 00 0 00 00 . 0. .0 . .. .. .. -. 00 0. C O O O C . 0. 00 ... .. . Q Q 0 O O . A a Z Q Z Q Z Z Z E Z QZ W J W Z W . .. . .. .. .. . .0 .0 . . .. 0. .. 0. 0. 0. 0w0 .0 w0 w. w0 .0 V. 0. 0 00.3 0 3 0. 0. 0. 0. 00 0 0 . o . o . 3. 0. 00 37 .. . 33:63 . . . . -0. 02 0' OL 0 . . o . 0 o 0 . .u. .. .. 0.0 . . O O O . on . .0 . O . .0 ¢. 0. . . .. 0 o . C 0 O .0 0. .. 0 . 0 § 0. . l 0. 0. .. . 00 .. .. 0. . . a . . 00 11 T2 T3 TL T5 T6 . o . . O I 23 .3 .. . OO DO DO DO IQ I. t o . . . .. 0. .-0. .. .0 .. .0 . 0 0 . ! . . . 4. 0 0 . 0. .. 0. . 00 .0 .. .. 0. .. 0. . 00.. . 30 .0 .5 .0 .. . 00 .. .. .. . 0 .5 0. 30 0. .. 0. .. .. .0 .. .. .. .. .. .. . 0 0 . .. -0 0. 0. 0 . 0 . . . . . . . . DO who m.» no. ..n ouo non ouo mon ouo uon owo noo 0. . % % % Z % % Z Z %% % % % % % . .s ... ... .. 3.x. n.n. 33. ,u. .n. n.u.n.n. u.n. u.u . 0 . 0 0 . 0 . . . . O C O O C O Q O . I . I . O O O . . O . .. w. u0 u. 4. u. uo u. m. . .. a.. 40 ?? ?»o «3 &5 .w0 u. 1. u. .0 u. u. w. u 0 u . L2+52 0014 9, T1 T2 T3 TL T5 T6 1 o u . . o . .. .. 0. . o .. 0. .. .. .. .. 0 o 0. 0. .. . 0. .. . .0 00 .. . 0. . $0 .0 .. . . p . .0 .. 0. .. .. . 0 . . .0 00 .. .0 00 00 .0 .. 0 0 o 0 0 0 . 0 . 00 .. 00 0. .. 00 .0 .. 0 0 p 0 I 0 0 n0u. M0». M0». M0n 0n. 0000M0 n0n 0n0 u0n 000 0.n 0u0 n0u0 u0n 0n0 n0n0n0 0x .n.0 0 0 .. 0..... .O . . 0 . % % % % Z % % %% % % % % Z Z % % Z Z % % 0 . . 0 0 . 0 0h 0 0. 0 0 0n . . O O. 0 00 . Y T1 T2 T3 TL T5 T6 .. 00 .. 0. 00 .0 .. .. 00 ?. 00 00 0. 00 .. 00 .0 0. .. .00m .0 00 .. .. .0 .. .0 .. 0.. . . 0.0 0 . . 0 . . . . 0 . . . 0 . 0 . . 0 . 0 . . . . . . 0 . . 00 00 .. .. 0. .. .0 .. 00 .. . .0 .. .. .0 00 00 .. 0. .0 0. . .0 .. .0 00 0. 0. .. .. 00 .. 0 . . O . . . . . . . . 0 . . . . . . 0 . . . . . O ' . 0 . . O .

0 .0 . «0 0. 00 w. 0. .. .. r. .0 .. r 00 0 0 . 0 0 0 . 0 . 0 .o . 00 0.00 0. 00 0 00 0. .. .. . 0 0 0 . 0 . 0 0 0 1 . . . J

. 002 n. 71 73

AQ

g

a

0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. »0. 0. .. /. an .m.um m... mmwm mmmm mmmm mm . 0 . o . . 0 . .: o . 0 .0 0 . n 0 00 .. .0 .. . 00 .0 0. 00 4 0 0. .. .. . . . . 1 . A n n v . . . : . 1 . . . . . u n c . . . D D 0 0 b D D 0. 0. 0. 00 00 . 0 . . 0 . 0 .. 00 00 0. 0. . 0 o 0 . 0 0 . . .u.9.C . u» .O. . 0 0 00 0. 0 .0 00 00 0090 .o . 00 .0 .0 . .0 0. 0. 0. .. . .. .0 .0 00 00 0 . 0 . O 0 0 o ...0. . 0. .. .0 0. ~90 100 llStudents living in city centres are often very active regarding transport policy and traffic environment. They are keen on debating and make a cnnsiderable amount of

demonstrations and they are evidently a very potent

pressure: group with hight impact on jpoliticians. The

traffic environment of the capital of Stockholm seems of utmost importance and this has led to generally sparsely populated Sweden having the strictest emission rules of Europe. Students are mainly found in the solitary youth group (21) since they form families later than non aca

dendt: youths. Especially :hi Tl (Stockholm) their car

disposing is extremely low. Evidently they live in an

area with sufficient population per square km looking

from a public transport viewpoint. They can cope without a car but when looking at car disposing for other groups

and in other areas quite another picture is emerging.

From a group ego viewpoint transport political activity

by students is OK, but one cannot name them representa

tives for the people.

Generally' the picture from figure 3.1 gets nuances.

Solitary people have lower car disposing (figure 3.1),

very much lower in the two big cities (Tl,T2) than in

other areas of lower density. Relations between adjacent

columns are not always regular but that can be due to

the population of the investigation being split on age, areas, socioeconomy etc. To compensate we have tried to add as many groups of people as possible but still some irregularities remain. The total picture of less cars in city areas is relevant anyhow.

Married people own a car to a high degree, as could be expected, and regional differentiation is small. This is especially relevant for parents where even those living

in Stockholm and Goteborg (Tl,T2) are car owners

(approaching 90 %). Retired people by tradition seldom

have a car and differences between regions are small.

Low transport activity and plenty of time might make

public transport sufficient for this group even in lower density areas.

These backgrounds might lead us to pose some questions:

- Families with children often have cars. Do they use

them more often?

- Low car density in Stockholm reflects high population

and good public transport. Do people in Stockholm use their public transport in a different way than people in other parts of the country?

To supply' a f g i density area like Stockholnt with

good public transport is relatively easy. Stockholm

is also the transport policy capital of Sweden. Does

this plead to exessive belief in public transport

means of solving transport problems? Does this also explain why transport policy ambitions are often too high.

We are not trying to get exact answers to all these

questions - the travel survey cannot furnish us with

that much information. When turning to transport

activi-ty in the survey however, it might be useful keeping

some of these questions in mind.

Transport policy is generally called traffic policy in

Sweden. Traffic relates to vehicle movements in the

transportation system, while transport is the production of the system. Transport policy debate regarding public transport has often been directed more towards creating

traffic than towards filling actual transportation

demand.

14

3.2 Main trips

Trips in the travel survey are made mainly for the fol lowing purposes.

Trips to and from work or school Trips during work

Service trips (e.g. shopping, children care or health care)

Visits and recreational trips Figure 3.4 shows their relationship.

100

Not specified Not specified

90 recreational 8% recreational 7%

l

80

Visits, trips

Visits, trips

29 % 4 %

1. 7o

5

+ 60 SerVice trips. . 17 % 4+ 50 ' k Service tri sh 40. Trips during wor ll % p

i 9 o

30 Trips to and from Trips during work

7"

work or school

15 %

37 % 4, 20

Trips to and from

10 work or school

'

21 %

Number of trips Transportation output.(WWLkm)

Figure 3.4 Trips in Sweden 1978 for specified

purposes.

From the figure two important factors in trips pattern emerge. Firstly trips to and from work are great in num

bers but rx : equally significant. regarding

transport-ation output. Evidently those trips are so numerous that they have great impact on public transport dimensioning.

However' their transportation output. is less than ex

pected. The Swedish Transport Ministry, for instance,

estimated work trips to 50 % of passenger transportation output in 1975. At that time they included trips during

work, which forces us to compare the travel survey s 36

% with the Transport Ministry's EM) %, still ea sizeable

difference. Secondly trips for visits and recreation are greater in number and longer than expected (giving more pass kms). Official ministerial material from 1975 esti mates their share of total transportation output to 25

%. The Travel Survey estimate is 45 %.

Having only one investigation in the travel survey form it is perhaps premature to say how great time visit

re-creational share is, but earlier estimates might have

overestimated the importance of work trips and corre

spondingly they' might have underestimated the visit/

recreational share. From the point of transport policy

this is interesting since so called necessary trips

(e.g. trips to and from work, and for service purposes) are rather inelastic relative to the price for the trip.

However trips during leisure time (e.g. social visits

and for recreation) are rather price sensitive. The

price for petrol might therefore have more impact on

total travel volume than earlier expected and increasing tax on petrol might primarily have reducing effects on

trip purposes that are not individually regarded as

necessary.

VTI REPORT 166A

KOLL = Public transport

BIL

Walking, cycling, motor cycling

Car Ovr

GCM Not specified

Travel modes:

fritidsresor Visits and recreation

Besoks-Serviceresor

och

Tjansteresor Trips during workTrips to and from work

Shopping and misc. services Arbetsresor

Purposes:

purposes, modal distribution and T-regions.

Figure 3.5 Total number of trips related to trip

FRI T l DSRESOR

ARBETSRESOR SERVICERESOR

T1 T2 T3 T1. T5 T6

TJANSTERESOR BESUKS- OCH

T1 T2 T3 T1. T5 T6 T1 T2 T3 Tl. T5 T6 T1 T2 T3 T4 T5 T6 100

\\\

\\\

\\\

\\\

x<\

\\\

\\\

\\\

&

a

VA

T/

1

a

a

7

/

3

6

§a

§

a

7//

///

///

ma/

///

//A

s7

///

///

///

/%,

,//

///

///

/

\\\

\\\

\\\

\\\

\\\

\\\

\\\

\\wu\

\\\

\\\

\\\

\\\

\\\

\§

e

7/

//

/n

V/

/

s

\\\\

\\\\

\\\\

\\\\

\\\\

a\\\

\\\\

\\\\

\\\\

\\\\

%7//

///é%

///zv

100..

mg

?

§§u§§s

%

us

§§m

§

7

§u§uy

w

§§m

§§ws

o

1 0 0 2§a

§

w.

7//

///

///

///

97/

///

///

///

/

§m

§

u

7//

///

///

///

Am%

///

///

///

/

2\\\

\\\

\\\

\\\

\\\

\h

\\\

\\\

\\\

\\\

\\\

\\&

37/

///

///

///

M%W

///

///

/

§m

§§ém

zz

§m

§i

g

év

100§m

§

w.

7/

//

//

//

%%

//

//

//

//

a

3\\\

\\\

\\\

\\\

\m\

\\\

\\\

\\\

\\\

§e

7//

///

///

///

%wV

///

///

//

\\\

\\\

\\\

\\\

\§\

\\\

\\\

\\\

\\\

\

e

///

///

///

//.

///

///

///

///

/f

m

m

m

m

\

1

\

&

W a ///

/

tion.motivated since the figure contains a lot of

informa-tion modally and regionally. An extensive commentary is

in different regions. Figure 3.5 shows their distribu

Travel patterns are different for different purposes and _ l6 _

Trips to and from work

Here one finds a characteristic modal split. Tl

(Stockholm) has a significantly low share of car trips but also low share of walking/cycling. Other investi-gations have shown trips to and from work in city re-gions to be longer than those in less densely popula

ted areas. This explains partly the low walking/

cycling share in T1 and T2 but one can also suspect

other factors like dangerous traffic conditions and

difficulties in keeping a cycle in city areas

(van-dalism and theft). One might also propose that good

public transport with short distance between stops

leads to excessive consumption of transport, i.e.

people use public transport instead of walking and

cycling. Great cities does not always show good pat-terns of energy economy.

Trips during work

These trips are dominated by car transport, which

seems natural (high value on time, irregular travel

patterns etc). But total number of trips is sparse and

one should not stretch internal modal relations too

far.

Service trips for shopping etc

These trips have a different pattern than the above mentioned. A lot of them are made by foot or cycling.

Probably this reflect that most of them citen twing

short distance trips. Only in cities they are made by public transport to a significant degree.

Trips for visits and recreational purposes

These trips are modally similar to service trips. Only in Stockholm (Tl) these trips are made to any sizeable amount by public transport.

_ 18 _

A11 purposes

Figure 3.5 is essential. In all regions but great cities people do not use their public transport very much. The

great bulk of filling transport demands relies on car

travelling. When having a car, people evidently use it for nearly all kinds of transportation. Public transport is most widely used for travelling to and from work cm school.

If one cuts away the regional differences one can split up purposes more (due to statistical reliability). Table

3.1 sums up purpose relations for car drivers, car pas

sengers and public transport passengers (omitting walk-ing/cycling).

Table 3.1 Purpose relations among total of trips for

car drivers, car passengers and public transport passengers.(%).

Purpose Car Car Public transport

driver passenger passenger

Mkn <, to and front 38,3 25,6 45,4

School, to and from 1,2 3,3 15,6

During work 15,6 4,6 3,9

Shopping

11,4

11,9

10,8

Service 2,5 1,2 1,7 Health care 1,0 1,5 1,9 Child care 0,4 0,2 0,1 Visiting relatives,friends 8,9 20,4 7,4 Recreation 11,6 24,0 10,4 Other _ 9,1 7,3 2,8 T o t a 1 100,0 100,0 100,0Car drivers have a wide range of purposes, with a gravi-ty point towards trips to and from work. This point of

gravity is more stressed among public transport

pass-engers however. Also notice the great share of trips to and from school among public transport passengers. Child

care trips are few among car drivers (as well as among

car passengers and public transport passengers). This is somewhat astonishing since child (Emma is often used to

explain why peOple are going by car to work although

they theoretically have good public transport possibili-ties. Since only "main trips" are counted in the table, leaving or fetching children while going to or from work

is not a trip purpose per se. Other material in the

Travel Survey also indicates that 45% of child care

trips are made walking/cycling and a dominating share of them are shorter than 2 km.

Car passengers are concentrated around trips to and from

work, for shopping, paying visits and for recreational

purposes. Together these purposes constitute 82 % of

total number trips 'made* by' car passengers. Evidently

these four purposes are most suited for some kind of ride sharing.

Public transport is dominated by trips to and from work and to and from school (together 61 %). Shopping, visits

and recreation in city areas are having a relatively

small impact on public transport shares for these pur poses. Each of them constitutes near 10 %.

Mode specific 'purpose relations (like above) are one

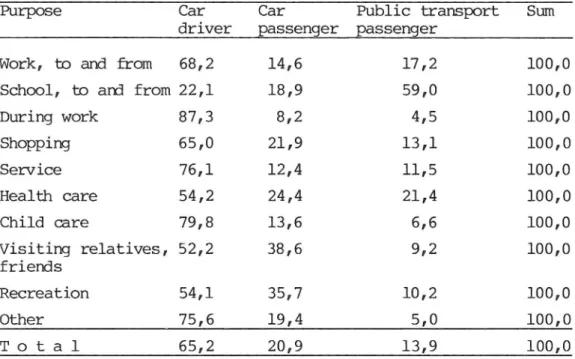

thing. Inter modal relations for each purpose is another aspect well worth contemplating. This is shown in table

3.2.

Table 3.2 Intermodal shares per purpose among total trips for car drivers, car passengers and public transport passengers.

Purpose Car Car Public transport Sum

driver passenger passenger

'Wbrk, to and from 68,2 14,6 17,2 100,0

School, to and from 22,1 18,9 59,0 100,0

During work 87,3 8,2 4,5 100,0 Shopping 65,0 21,9 13,1 100,0 Service 76,1 12,4 11,5 100,0 HEalth care 54,2 24,4 21,4 100,0 Child care 79,8 13,6 6,6 100,0 Visiting relatives, 52,2 38,6 9,2 100,0 friends Recreation 54,1 35,7 10,2 100,0 Other 75,6 19,4 5,0 100,0 T o t a 1 65,2 20,9 13,9 100,0

This table is significantly dominated by the car. Travel-ling as car driver constitutes between 50 and 85 % of all purposes except to and from school. Children going to and from school do this mainly by public transport (59 %) and school trips have also a significant share of all public transport trips (15,6 % in table 3.1). Another very inte

resting feature is shown by work trips. Nearly as many

trips to and from work are made by car passengers as by

public transport. It is probably quite unexpected that

ride sharing to and from work nearly equals public

transport. Also for other purposes car passengers make

more trips than by public transport. Totally, car pass

enger trips are one and a half as many as public trans port trips!

As mentioned school trips constitute a significant share

(If public transport. Zni rural (n: semi-urban regions (T5

and T6) people aged 15-24 years constitute more than a

Ihalf ( ? total. public transport trips. IU1 denser areas

this share is "only" 24 to 35 %, reflecting a more wide spread use by all age groups. This shows what impact on transportation the school reform of Sweden has had. Only

in lower forms are schools situated near home which

forces children i ) years old and more to "travel" to

school. Evidently this school policy has lead to a trans

portation dependency perhaps not envisaged at the time

when the cbcision was made. ZU1 many rural areas school

busing is vital to total volume of public transport

supply.

The mentioned rural dependency on school trips for public transports supply is an aspect on Swedish population geo

graphy. Sparsely populated areas are common and only one

"real" city region is present - Stockholm. The Stockholm

region consequently contrasts itself to the rest of the

country since more than 40 % of all public transport

trips are made in the Tl region.

As a whole one might summarize this part of the report in the following way:

Families with children are owning a car nearly always.

They are also seldom using public transport. People in

Stockholm are less prone to car owning than the rest of the population, but they use their good public transport more than other people. A dark shade in that bright pic ture is their low use of walking or cycling as a mean of transportation. Stockholm dominates the transport policy debate but people there are definitely not representative of the country as a whole. With less than 20 % of

nation-al population they constitute more than 40% of public

transport trips reflecting a very atypical transportation geography.

3.3 Long distance travelling

Trips more than 100 km are defined in the travel survey

as long distance trips. Compared to local trips these

trips are rather few and those interviewed was

conse-quently asked to try remembering not only trips made the

day before. For trips at least 100 km the period was ex

tended to 14 days, for trips more than 400 kms the

period was 6 months. One must be very cautious about

these long memory periods since they are often biased and distorted by failure to remember. For instance the questions on traffic accidents had to be withdrawn from publication due to characteristic time related losses of

memorated events.

Bearing these cautions in mind one have to treat long

distance travelling with a certain amount of sceptisism.

Some facts might be mentioned though. Trips with only

one visit or stop dominate and the trips are as a whole

clearly dominated by car travelling (91 % for one way

trips 88 % for return trips). The long distance trip

material is dominated by its shortest distance classes

(53 % of one way trips are thus 100-199 kms, 56 % of

return trips are 200-399 kms, that category's shortest

distance class). If a trip comprises more than one visit or stop it is often longer but these trips on the whole

are few.

Purposes for long distance trips are firstly recrea

tional (43 %), secondly shopping, service, health care,

child care and social visits to relatives and others

(together comprising 34 %). On third place, perhaps un expectedly low, come trips to, from and during work, 23 % of total number long distance trips.

Modal split is not inherent in long distance travelling, mainly due to the fact that the shortest group of trips with only one visit or stop are dominating. Modal

combi-nations are subsequently sparse and 96 % of all long

distance trips are single mode trips. For all purposes car travelling also dominates, not surprising since the large share of recreational trips makes the private car attractive also on rather long distances.

Distance relations for long distance trips are often in-teresting. We have chosen a custance pmofile technique to show how many percent of travelling is made by each

mode cumulating distances. The technique :hs applied in

figures 3.6 and 3.7. It explains how many accumulated

percent of total trips are made up to 200 kms, up to 400

kms etc. The first figure shows trip purposes that are

not supposed tx> be paid by the traveller personally

(trip to, from and during work). In the second it is

assumed that rmx : travellers pay for the trip them

selves. {62) IO 50 )0 60 so... no 30 '

/

m [f // {D I __.¢- -"-1'/' l A n0 Ian 21. 300 9'0. 57:. so. 700 elm 90. MD. "00 I200 I700 mo 190 I600 "00 I830 Km

Figure 3.6 Long distance trip to, from and during

work

Legend: Flyg = airplane

Tag = train

Buss = bus

Bil = car

i w

0 mo joo 500 in SD. (.00 0 " 1+" "100 '0 l0. 90 $09 '0' "0° "0° "0' $00 k

Figure 3.7 Long distance trips for shopping, service,

health care, child care, visiting

relatives and others, for recreation.

It follows from the figures that car is the HDSt short

distance oriented travel mode. However, bus and train

are rather close in distance profiles. Only airplane is

significantly':more innu; distance prone. Travelling by

own means or having the trip paid by others does not in

fluence distance profiles for car, tum; or train.

Air-plane, however, is evidently only used for really long

trips especially when people pay the ticket themselves.

3.4 Can public transport substitute private car transport?

Analysing competition between transport modes is not an

easy task. However, it is facilitated by a process of

segmentation, followed by separate studies of each

seg-ment. Paradoxically enough this often. points to less

competition than perhaps expected. Studying goods trans-port as well as personal travelling often leads to iden-tifying a sequence of submarkets for each mode where no real competition is present. Competition can then be lo

cated to Imnxa or less wide zones between these sub

markets. The competition areas move with time in one or the other direction, e g influenced by changing economic relations between modes, changing goods structure, vari-ations in the volume of demand which different modes are varyingly able to cope with, etc.

To make a realistic estimate of where and when public transport might substitute private car transport we have decided to approach the problem in accordance with these lines. First we try to map modal variations in segments

of travel times, distances and hour by hour. Then we try

to estimate and allocate those areas where the private

car is not having a total monopoly, or where it might

show deficiences being able to be exploited by public

transport. It follows from this reasoning that we

con-sider it unrealistic to recommend traditional forms Ci

public transport as a general substitute for car trans-port e g in geographic environments where presently pub-lic transport is virtually not used.

3.5 Travel time and distance

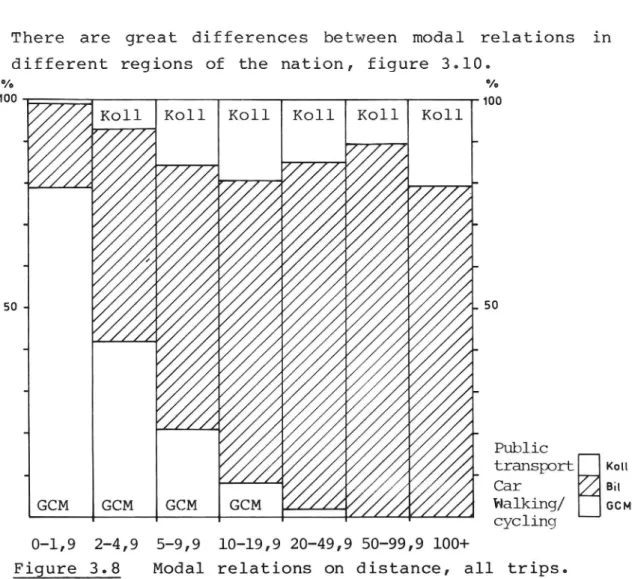

Public transport has its strength :hi medium distances,

see figure 3980

This is further accentuated counting only trips to and from work, where public transport is generally stronger, figure 3090

However, public transport is not dominating any single

distance class, c f walking and cycling on distances

less than 2 kms. The private car competes with walking/ cycling on short distance and with public transport on

trips more than 5 kms. Public transport evidently has

advantages for really long trips over 100 kms.

There are great differences between modal relations in

different regions of the nation, figure 3.10.

0/. °/o W0 mo K011 K011 K011 K011 K011

/

50-1\\

\\

Public transportlll Car Walking/ cycling 1n\

\\

\.

\\

\\

\

k

GCM GCM GCM O l,9 2-4,9 5-9,9 lO-l9,9 20 49,9 50-99,9 100+Figure 3.8 Modal relations on distance, all trips.

100 Koll. B l GCM M . I C G _ 27 _ 100 W M W M H Q _ m W -=

mm

m

K

7/////

//////

//////

///

Km

1

_

.

_

_

b

.

.

a

V/////

//////

//////

cm

a

/

/

W

,

.7/////

///////

///////

//

as

K

V

1

a

1

_///////

////////

////

m

1

/

/

9,

m

a

7////

/////

///Km

a

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

%

K

7///

////

/K

K

//

/

m

d

m

,

/

/

a,

o

7////////

///////,i

Km

K

7

/

K

m.

////////

////////

////////

i

cm...

1

/

m

.3

///////

///////

/////4

GT

a

/

//

9,

Km

7//////

///////

//4

Km

K

W

/

K

am

u

7/////

//////

/2

cm

1 7 ,/1 m r_ m m W % W % m a a/

/

V

G

a

M

a

//

//

/Z

M

%

u

%

K

9

//////

/é

cm

m

/

K

K

0

//////

z

Km

/ _ m 3 M 3Q

M

m

M

Z

c

m

% . . . m .W J _ _ L / 7 / / Z _ _ _ _ _ °/o 100 h 0 5 5 - 9,9 km 2 - 4,9 km 0,1 1,9 kmFigure 3.10 Modal relations on distance in T-regions,

trips to and from work.

°/o 100 28 -50 °/o 100 " 50 T1 T2 T4

Legend of standard classes: Distance to stop 1. 0 499 m 2. 0 499 m 3. 500 - 2000 m 4. 0 - 499 m 5. 500 - 2000 m 6. 0 499 m 7. 500 - 2000 m 5. not Figure 3.11 specified or known

VTI REPORT 166A

H -n w 5 T6 Trip frequency at at at at at least least least least least 2/h daily 2/h work days 2/h work days 4/day 4/day less than 4/day less than 4/day

On distance less than 2 kms only people in Stockholm

(Tl) use public transport for their work trips. In all

other regions public transport is virtually nil. This is probably due to the great standard and general access

ibility ( ? public transport. in Stockholm. Coupled to

short distances between bus stops this leads to what

might be called excessive consumpthmn of public trans port. However, the standard of public transport must be rather high to compete with walking or cycling on such short distant trips. How high is the standard of public

transport in Stockholm compared with other areas of

Sweden? Figure 3.11 gives a hint on frequences and

dis-tances from time homes of the interviewed persons to

nearest bus stop.

Classes 1 and 2 might be treated as relevant for work trips. Apparently no significant difference exists

bet-ween Stockholm (Tl), Goteborg (T2) and medium sized

towns (T3). However, a bus frequency of 2 per hour is

not a very frequent traffic and theoretic measures like this cannot distinguish between good and decent or

half-decent transport supply. IX crude measure ( ? frequency

does not always tell much about how well transport supp-ly covers actual transportation demands geographicalsupp-ly.

A clue might be found in dwelling structure, whereone

can expect much better transport supply in denser areas with multi storey or multifamily houses.

0/0 0/0 100 100 :-q . 50 " - 50 T1 T2 T3 T4 T5 T6

Figure 3.12 Dwelling structure in T-regions, percental

shares of people living in multi family houses.

Dwelling structure 1h] different T regions :Es mapped 111

figure 3.12. In denser regions like T1, T? auKi'T3 more

than 2/3 lives in multi family houses. We can now return to figure 3.11 and review our standard measurement dis

tributed on single family and multi family housing,

figure 3.13. Width of columns are proportional to the

share of people living in respective type of housing

according to figure 3.12.

96 1 III/[Ill]

.. /

jg

///{////4

/ '

..

3 / 0 b-

_

3

S

//////

90 L 3 L 7 ./32Z 6Z6? 2 I -L 6 7 780-

2

2

%

3

5

6

6

//

70- 3 3 h 7 60~ - 2 4 5 5 __3:

__

s

504

7

5

__ 6 _ 1 1 4 _. O 4 5 4 3 30* 5 _ n 1 1 1 2 -3L 2 20- 3 4 __ -2 410 ~

1

2

11

~

1 2 O 1 1 F E F E F E F E F E F E T1 T2 T3 T4 T5 T5 Legend:E = single family houses

F = multi family houses

For standard classification see figure 3.11

Figure 3.13 Standard of public transport on T regions

and dwelling structure.

Most of the differences in public transport supply can

evidently? be attributed to housing structure. In the

denser regions (T1, T2, T3) transport supply is much

better in multi family house areas. However the step to the standand of T4 is rather great even when counting

only multi family houses of that region. From T4 and up

wards there is seldom any special type of urban public transportation service. What is to be seen here is when

rural transport reaches (n: passes urban areas (c f'T4).

It follows from figures 3.11 and 3.13 that one

should not expect public transport supply concerning work trips to any significant degree outside regions T1,

T2 and T3. Going to what could be called school bus

standard or service/visit standard (classes 3 and 4) the

coverage is decent also in T4. In sparsely populated

areas like T5 and T6 however even that type of public transport standard is not frequent.

However, it follows from above and from earlier figures

that gnly in Stockholm is more use made of public trans

port supply than elsewhere in the country. This suggest

that. increasing public transport standard does not a

priori lead to fuller use of public transport. If people should really be stimulated to full use of their public transport the supply must evidently be nearly excellent. Can then public transport substitute car transport? Or put the question the other way round: Why don't people use public transport instead of their own car? The only way in this survey where one can compare one person's choice of transport modes is in a table where the inter viewed (if found to have gone to work by car yesterday)

was asked how long the car trip took and how long a

corresponding public transport trip would take. The

interviewers were asked to bring time tables etc to the interview to be able to help people make relevant esti-mates of corresponding public transport trips.

Table 3.3 shows car travellers trip time to work by car, table 3.4 shows their corresponding time if they would have gone by public transport instead.

Table 3.3 Travel time for car travellers to work,

percental shares. Minutes % 0- 9 18 10 19 40 20 29 20 30 39 10 40-59 6 60 89 2 90+ 1

Table 3.4 Travel time by public transport for car

travellers to work, percental shares.

Minutes % 0 9 0 10-19 2 20-29 5 30-39 7 40 59 8 60 89 6 90+ 7 "won't go" 58

Source tables 3.3 and 3.4: Travel Survey of Sweden, table 7021.

One should use the above figures with care since they probably are connected with some bias and random errors. Firstly tables do not cover those with really good

pub-lic transport since they seldom use car for going to

work. Secondly there is a large share of non answerers to this question suggesting large difficulties in esti

mating corresponding public transport travel times for

those normally using car for their trip to work. Thirdly there is a regional bias in having 59 % of the answers coming from region T6, namely norhtern rural areas. This

being said however, there are some interesting facts

which can be extracted from the tables.

For instance people going by car will evidently increase

their travel time substantially switching to public

transport. A careful interpretation is picking out medi an time, which leads us to the 10-19 minute class for car travelling but forces us into the "won't go" class for corresponding public transport.

That in turn leads us to believe that for most car com-muters public transport is IKH: a feasible alternative.

Put it another way: One might believe these people to

change work place (or perhaps give up work) rather than

use public transport. Since in Sweden legal deduction

from income for trips to and from work is permitted to

be based on car mileage if a person spares at least 90

minutes for the return trip (both ways) one might

con-clude that a majority of car commuters does have this legal right. It is often discussed however to increase the required time gain tx><e g two hours or to stop the

deduction possibility completely, which would increase

actual travel costs for car commuters.

From the above mentioned figures one might conclude that

the effect of such a decision would perhaps not be to

stimulate peOple going by public transport instead of by car. More probable a possibility seems to be a change in work place, ride sharing or work cessation.

3.6 Travelling hour by hour

Transport capacity is often directed by peak loads

during the day. Trips to and from work and school is

concentrated to two peaks at 7-9 am and at 3-5 pm. For people working with public transport capacity planning

this is a well known problem. Public transport has its

main purpose furnishing work and school trips and this

500

-in between hours. The two peaks

that it is

causes slack capacity

are so distant apart, however, not often

possible for one bus driver to cover both peaks thereby the

morning and afternoon shifts for

turn leads to slack hours not only in between hours but

forcing public transport company to have early

its drivers. This in

before and after peaks too. Total travelling does not

have these peaks, see figure 3.14.

It

04 5

total number of trips

- trips to and from work or school

Figure 3.14 Travelling hour by hour.

Total trip number has a soft peak at noon. That is

em-plained by activities around the lunch break such as

short walks to home or to restaurants, canteens etc and

also errands like shopping, other service, visits of all cycling kinds etc. These trips are often made by foot,

or by car.

VTI REPORT 166A

In the figure is also mapped work trips and school trips where the two humped character are evident. Total travel peaks off rather slowly "The later the trip the greater the car share" is one of the general results from other travel surveys made in Sweden. Most of this late travel-ling is going to and from leisure activities, cultural activities, and evening classes. Another often not men

tioned trip purpose is parents driving children to or

from sport activities, friends etc. Let us conclude this part:

Work trips and school trips have a two-humped hour-by hour profile.

- Public transport is generally oriented towards fill

ing trip needs for work and school, and consequently it shares this profile.

At peak hours buses are full and increasing

trans-portation output at those hours requires (expensive) additional traffic.

- Additional passengers at non peak hours are cheaply

accomodated but hard 13) geta Traditional forms of

public transport is evidently not attractive for pur-poses relevant at those hours.

- Total transportation output has a soft peak at noon

which slopes gently downwards in the evening.

4 AN ALTERNATIVE WAY OF STUDYING TRAVEL BEHAVIOUR

4.1 Demand and supply

When people debate human needs of mobility, they often

recommend public transport as some kind of universal solution for problems like the energy crisis, the de-toriating quality of the traffic environment, etc. That is easier said than done. Public transport is

astonish-ingly' declining, generally' speaking, in term of its

share of total transportation output. Why is it so? Are

people overlooking the problems around solving energy

problems and environmental problems with public trans

port? The Travel Survey of Sweden so far described has

shown some of the problems, e g with low use of public transport outside city areas. We are now trying to seek

new answers by analysing demand and supply of

trans-portation. After that we shall try to estimate if

better public transport can meet typical demands from

the public.

Total demand for transport is generated by present

spa-tial. organization coupled to those functions in the

society that need to be reached (e g schools, health

care, shops) or done (e g work).

Creating demand

Eogsing/ 0£k_s_e_psratioa

Traditionally density in the dwelling structure has in-creased. However, in the latest decades one can discern

a return towards lower density in housing. An inter

national trend of migrating from. multi store houses

towards lower houses is evidently present (see ch 2). This leads to more and longer transportation needed for trips to and from work and the low density

dwelling areas cause additional problems since such areas are difficult to cover with dense public trans port. Additionally, these spatial problems are severed by concentrating work places into large industrial com plexes, externally located areas for industries, etc.

Ecenemies 9f_ssa_l_e_i_r1 shepgiag_a d_dis£rib9_tioa

In the old days local shops covered most of the demands

of the population. Nowadays more and more shopping is

done in super-markets. These are often easily reached

by car. They often in one location supply the customer

with a wide range of service opportunities, but they

also create car trips. Perhaps trips to the shop are

made less often now, but they are now made by car, not

foot.

lnErEa§i£9_W2 - Ei g_rit§ _: exfegnelyhildfers

In the old days of the core family the wife was home with the children and the husband alone was working for

cash. Increasing female work rate increases the number

of trip to and from work, but it must be pointed out

that women making trips to and from work are more often

using public transport than men. Male/female rate in

public transport in general is 40/60. Increased female

work rate also causes child care trips if child care

demand is not filled at home or very close to home. lnErEaéeé 2m292t_0£.lei32rs Ei e

Fewer work days and shorter working hours are increas

ing recreational travelling. This is a current trend

that can be stretched into the future. Most

recrea-tional trip purposes cannot be met sufficiently without a car. Disposing a car is perhaps going to be even more

essential for a family if for instance more families

aquire recreation huts, etc. Trying to reach a recrea-tion house by public transport probably means no trip at all.

ingreaseé etenslariof lili

Standard of living expansion rate has levelled off in

the l970:s. More glum a future is envisaged for the

l980:s. Car owning rate is generally proportional to

total car mileage. In other words: Car use has expanded

during the l970:s but expansion rate is modest now

adays. There is still room for a small amount of in

creased car ownership but mileage might be retarded by switching towards more tax on use (e g petrol tax) than on ownership (normal forms of road tax etc).

Scale scenemiee _i_H_e§_usa:c_ien_ap_d_0£hsr_pgblis service

School hierarchies have caused a lot of travelling

during the last decade. The system of letting children choose among different alternative courses and general

directions and still keeping these courses inter

changeable inside the same school has made school units

large, and in turn this has forced children from ten

years age and older to "travel" to school.

The school system is an excellent example of public

sector scale economies where you want better standard

(on education) e g by increasing selection possibili

ties but where you unfortunately in the bargain get

bigger units c f a non local character. Other examples

can be chosen. For instance health care in Sweden is

now more centralized towards larger hospitals, giving

possibilities of specialized treatment but forcing

patients to transport themselves to the hospital to get

the desired care. Another example is the communal

reform which in two steps during the last two decades

has diminished the number of communes from 2 400 to

275. Earlier, different forms of contact and service

were reached locally, now people must go by car or bus

to get those services.

Eoial Sema2d§.£0£ Ersvsl

The enumerated trends and changes in society give a

hint on how much travel people need in a modern society compared to earlier, more locally oriented (and static)

society. Add to that all social needs, i e recreation

and visits which are always present. One can then form a stepwise procedure to describe how demand and supply

interact, also restricted and combined with people's

wishes to minimize costs and efforts for their trips. Figure 4.1 is an example encompassing also the sampling and blow up procedure.

WISHES AND NEEDS FOR

TRANSPORTATION

TRANSPORTATION SUPPLY RESOURCE RESTRICTIONS MINIMIZING EFFORTS RESULTANT TRIPSSAMPLING BLOW UP OF SAMPLE TRAVEL SURVEY TRIPS

Figure 4.1 Image of relations between transportation

demand, supply, trip pattern and sampling