From harvest to end consumer:

Consequence of the behaviour of

“Generation Y” regarding food waste

on the supply chain of fresh fruits and

vegetables

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: From harvest to end consumer: Consequence of the behaviour of “Generation Y” regarding food waste on the supply chain concerning fresh fruits and vegetables

Authors: Mustafa Ahmed Khan and Lena Nabernik Tutor: Imoh Antai

Date: 2020-05-18

Key terms: food supply chain, fruits and vegetables, food waste, sustainability, generation y

Abstract

Food waste is a major issue from various perspectives. During the process from harvest to the end consumer, almost one-third of food produced is wasted. It is not just the wasted food during the process that is concerning, there are issues in sustainability related to food waste that need to be considered. Moreover, there has been little attention to the issue of food waste in the downstream part of the supply chain and how specific behaviours affect the issue of wasting food.

This thesis explores the food waste of fresh fruits and vegetables from a consumer´s perspective. To specify, the purpose of the study is to investigate the drivers of the disposal pattern of fresh fruit and vegetables, with an emphasis on the behaviour of "Generation Y" (born 1980 – 1995). Therefore, a revised model of the Theory of Planned Behaviour is applied. Also, to understand the behaviour of "Generation Y" regarding disposal, it is expected to identify impacts on the supply chain.

A deductive approach is applied to this thesis. The qualitative study was conducted with open-ended survey questions to supplement the results with the answers of the respondents. The empirical data is collected from consumers within the “Generation Y” who usually purchase their fresh fruits and vegetables for their respective households. The data was analysed using the coding analysis which involves summarization and categorization of data.

The results of the research reveal that external attitudinal factors such as price and marketing perception, storage habits, and quality consciousness and internal attitudinal factors such as sustainable environmental awareness, health consciousness, and subjective norms influence the respondents’ disposal behaviour. Moreover, the sustainable attitude of “Generation Y’’ leads to most of the consumers’ waste reduction, and highly influences the supply chain.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

1

1.1 Background 1

1.2 Problem discussion 3

1.3 Purpose and Research Question 3

1.4 Scope and Delimitation 4

1.5 Definitions 5

1.6 Outline 6

2. Literature Review

7

2.1 Food supply chain 7

2.2 Food wasted across the supply chain in Europe 8

2.3 Food wasted across the supply chain in Europe per food type 9

2.4 Food wasted across the supply chain in Europe per sector 10

2.4.1 Reasons for the waste of ffv in the agricultural sector 12

2.4.2 Reasons for the waste of ffv in post-harvest 13

2.4.3 Reasons for the waste of ffv at the end consumer 14

2.5 Generations 15

2.6 Generation Y 17

2.7 Sustainability 17

2.8 Sustainability issues due to ffv 18

3 Theoretical framework

20

3.1 Selected modified models of TPB 22

3.1.1 Modified TPB by Tarkiainen and Sundqvist 22

3.1.2 Modified model of Chu 23

3.2 Proposed theoretical framework 24

4. Methodology

27

4.1 Research Philosophy 27 4.2 Research Approach 28 4.3 Research Design 29 4.4 Data Collection 31 4.5 Data Analysis 32 4.6 Research Quality 335. Empirical Findings

36

5.1 Empirical findings of common disposal pattern 36

5.1.1 Amount of weekly bought ffv 36

5.1.2 Characteristics that affect the buying behaviour of ffv 37

5.1.3 Results about the number of ffv people throw away 38

5.1.4 Disposal habits of ffv 39

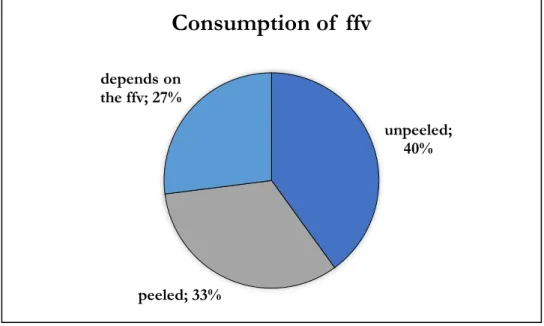

5.1.5 Eating behaviour of ffv 40

5.2 Empirical findings of external factors 41

5.2.1 Purchasing behaviour 41

5.2.2 Correlation between bought and disposed ffv 43

5.2.3 Reasons to buy imperfect ffv 44

5.2.4 Outcomes for most mutual reasons of disposal of ffv 45

5.2.5 Disposal due to appearance reasons 46

5.2.6 Storage facilities and influence on disposal 46

5.3 Empirical findings internal factors 47

5.3.1 Buying and disposing ffv as a symbol of standard and courtesy 47

5.3.2 Impact of the ffv supply chain on the environment 49

5.3.3 Facts and influence about discard behaviour 49

5.3.4 Correlation between environmental harm and discard behaviour 50

5.3.5 Sustainable aspects related to ffv buying behaviour 51

5.3.6 Reasons for the consumption of ffv 52

5.3.7 Opinions about imperfect ffv harm the health 52

5.4. Empirical findings on supply chain influence 52

6. Analysis

55

6.1 External Factors 56

6.1.1 Influence of price and marketing perception on disposal behaviour 56

6.1.2 Influence of the storage habits on disposal behaviour 57

6.1.3 Influence of quality consciousness on disposal behaviour 57

6.1.4 Influence of awareness of discard on disposal behaviour 58

6.2 Internal factors 59

6.2.1 Influence of sustainable and environmental awareness on disposal behaviour 59

6.2.2 Influence of health consciousness on disposal behaviour 59

6.4 Attitudinal behaviours affecting the supply chain 61

6.4.1 Agricultural sector 61

6.4.2 Post-harvest sector 62

6.4.3 The sector of the end-consumer 62

7. Discussion and Conclusion

64

7.1 Discussion 64 7.2 Conclusion 66 7.3 Limitations 68 7.4 Further Research 69

8. Bibliography

70

9. Appendix

75

Figures

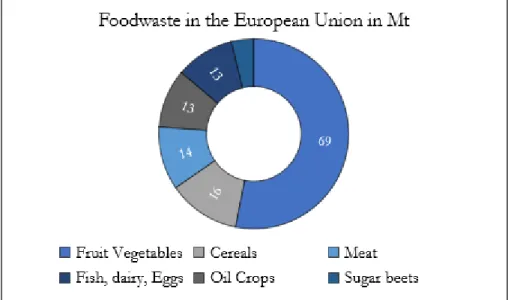

Figure 1 Caldeira et. al (2019): Waste of food in the EU in Mt 9

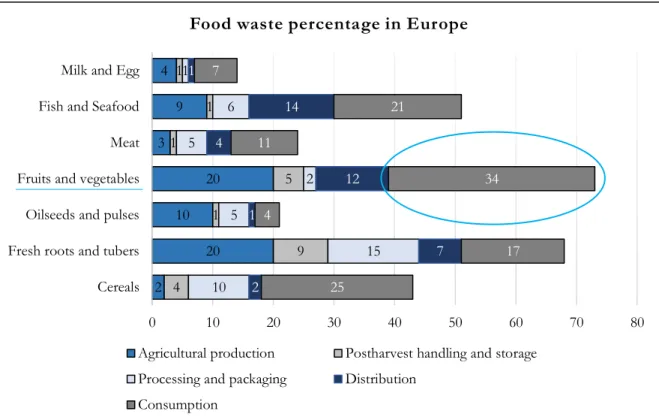

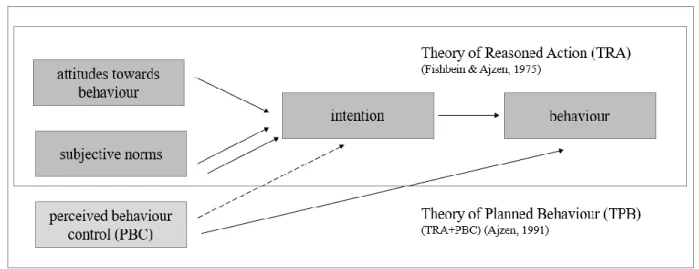

Figure 2 Food waste percentage (Gustavsson, Cederberg, Sonesson, van Otterdijk, et al., 2011) 11 Figure 3 Theory of Reasoned Action and Theory of Planned Behaviour, (Ajzen, 1991) 21 Figure 4 Adapted TPB model of Tarkianien & Sundqvist (2005) about the buying behaviour 23 Figure 5 Adapted TPB model of Chu (2018) about the attitude towards organic food 24 Figure 6 Adapted TPB model about the attitude towards disposal pattern of ffv 25

Figure 7 Weekly bought ffv 37

Figure 8 Characteristics considered while buying ffv 38

Figure 9 Pieces of ffv discarded per week 39

Figure 10 Consumption of ffv 40

Figure 11 Incentive to purchase ffv 42

Figure 12 Reasons for changing the buying behaviour 43

Figure 13 Reason to buy imperfect ffv 44

Figure 14 Common reasons to dispose ffv 45

Figure 15 Buying ffv as level of standard and courtesy 48

Figure 16 Changes of discard behaviour 50

Figure 17 Changes for the environment 53

Figure 18 Revised TPB model for further studies 65

Abbreviations

CO2: Carbon dioxide

FAO: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Ffv: Fresh fruits and vegetables

ISO: International Organization for Standardization Mt: Million tons

OECD: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development Pbc: Perceived behavioural control

TPB: Theory of Planned Behaviour TRA: Theory of Reasoned Action

1. Introduction

________________________________________________________________________________________ This study begins with some background information about the topic of food waste and its impact on the supply chain and sustainability. Afterward, the research gap is demonstrated, followed by the scope and delimitations of this study. Thereafter, research purpose and questions are demonstrated, suited by important definitions. Conclusively, the introduction closes with the outline of the work.

_________________________________________________________________________

1.1 Background

Food wastage has grown into an important phenomenon, as it has been studied thoroughly in recent years. It is estimated that one-third of the food along the food supply chain from the production to the consumption faces loss or waste (Abiad & Meho, 2018). The topic of food waste has morphed into an inescapable behaviour in our modern society. This is due to food shortage still being one of the main threats for millions of people inside and mostly outside of Europe. For this reason, the main objective is to assess the food waste along the food supply chain. While the issue of food waste is a cause of concern for the planet, it is estimated that approximately 50% of the food wastage comprises of fresh fruits and vegetables (ffv) (De Laurentiis et al., 2018).

The demand for ffv has increased enormously in recent years due to lifestyle and nutritional trends. This means that end consumers increase the demand for ffv through their motives of shifting towards a healthier lifestyle. At the same time, this also leads to a higher workload on the supply chain and increased waste in this area. (Klein, 2019; Porat et al., 2018). Thus, it is important to focus on the area of ffv and identify the losses there.

Food waste is identified in a variety of ways and as witnessed has a direct impact on the sustainability of the planet. It occurs as a result of edible food being wasted due to human intervention or negligence. It usually arises as a result of decisions made by actors along the supply chain such as farmers, producers, retailers, and consumers. For instance, consumers often discard or throw away food that is even though not in the optimum quality but still very much

edible (Mattsson et al., 2018). Thus, the food wasted at the consumer’s end is classified as a significant part of the overall food losses (Ishangulyyev et al., 2019).

Previously conducted studies have shown that the largest division of food that is wasted along the supply chain comprises of ffv. As research shows, 70% of the total loss of ffv occurs in households and retail sectors (Mattsson et al., 2018). There are numerous reasons why wastage occurs during the retail phase ranging from short shelf life, transportation issues, fragile packing, overstocking, and damage during handling (Wikstrom et al., 2019). However, in terms of households, this wastage arises for reasons such as nearing expiry dates, surplus buying in comparison with actual consumption, and premature disposal. Therefore, wastage of ffv due to the human inability to consume the products qualifies nonetheless as a total food loss (Cicatiello et al., 2016).

The promotion of food sustainability has gained widespread attention in recent years, as consumers and producers alike switch their behaviours and shift towards sustainable development. However, a major concern remains; the wastage of food during the last couple of years and its carbon footprint on the planet (Porat et al., 2018). The primary indicators of sustainability in food supply chains are the impact on materials (waste and spoilage) and energy (emissions, carbon footprint) (Gokarn & Kuthambalayan, 2019). The global food loss leads to greenhouse gases being released into the atmosphere which reaches up to 3.3 billion tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) costing 750 billion USD annually (Eriksson et al., 2015). It is understood that while food loss being inevitable, it can still be preserved and used in parts of the world where there is a dire shortage of food (Melbye et al., 2017).

It is important to note that the production of food requires natural resources and that takes a significant impact on the environment. From the point of production to final consumption i.e. the food supply chain, production of food has an impact on the environment in terms of ecotoxicity, acidification, and biodiversity (Sala et al., 2017). Food wastage represents an utter loss of natural resources and as we move further down the supply chain towards the consumption side, the food wastage carries a more severe impact (Scherhaufer et al., 2018). Additionally, non-consumable ffv due to quality and freshness issues at the consumers’ end results in economic drainage for every actor in the supply chain. Thus, along the entire food

supply chain, costs associated with food production accumulate, not only resulting in value but in terms of resources as well as financial capital (Caldeira et al., 2019).

1.2 Problem discussion

The issue of food waste is not simple to controvert, due to the various actors involved in the food supply chain (Ozbuk & Coskun, 2020). During the process from harvest to the end consumer almost one-third of food produced is wasted, which depicts a huge issue in different areas (HLPE, 2014). It is not just the wasted food during the process that is concerning, there are issues in sustainability occurring as well that need to be further deliberated and considered (Garcia-Herrero et al., 2018). Moreover, there has been paid too little attention to the issue of food waste in the downstream part of the supply chain and how specific behaviours would affect the issue of wasting food.

1.3 Purpose and Research Question

Recently, several studies about the issue of food waste are available, which affirms the importance of the topic. Some research was conducted in the sector of the food supply chain and the influences of the waste on the environment. The significance of resources, sustainability, and global warming affects today's society (Asian et al., 2019; Porter et al., 2018). Nevertheless, in terms of the issue of food waste on the supply chain, the current stage of the investigation is still not satisfactory. Furthermore, examinations across the supply chain, and the losses in different parts (combined and in segments) are allocable (Kelly et al., 2019; Raut et al., 2019). Especially, in terms of the biggest problem of the consumer sector, the younger generation “Generation Y” is disposing of more food than their predecessor before (Klein, 2019). There is barely information about this development and it can influence the entire supply chain intensely. Therefore, the attitudinal factors and the behaviour of “Generation Y” might have an enormous effect on the supply chain of ffv (Eyerund & Neligan, 2017).

The purpose of the study is to investigate the driversof the disposal pattern of fresh fruit and vegetables, with an emphasis on the behaviour of "Generation Y". In addition, by understanding the behaviour of "Generation Y" regarding disposal, it is expected to identify impacts on the supply chain of fresh fruits and vegetables.

Due to the problem discretion and the objective mentioned recently, this study resolves the following research questions:

What are attitudinal factors that affect the wastage behaviour on fresh fruits and vegetables of “Generation Y”? How does the attitudinal behaviour of “Generation Y” affects the supply chain of fresh fruits and vegetables?

To find the right answers to these questions, the food supply chain of ffv will be examined from literature. First of all, it is important to reveal the main causes of food loss and its effects on the supply chain. Nevertheless, the final consumer is the most important player in terms of food consumption, which makes it very significant to determine what they are willing to contribute to this issue. Especially the attitudinal factors that influencing the behaviour of the “Generation Y” regarding their disposal pattern of ffv supply chain are going to be examined. Subsequently, the relevant factors are considered in determining the impact on the supply chain.

1.4 Scope and Delimitation

Concerning the rising significance of the topic of food loss, the investigation of the supply chain of food and the entire process is advisable for gaining the optimum amount and scale of the loss. Nevertheless, it is not possible to consider all of the divisions and different foods in this study. Due to time and other resources containing, only ffv are treated in terms of the food type, because this sector is the biggest contributor in terms of food waste (Caldeira et al., 2019). Furthermore, to narrow down the scale in geography, only Europe is getting observed. The amount of food wasted in western Europe averages 71 – 92 kg per head per year, so the examination of this region is highly recommended (Blanke, 2015). The study will examine the supply chain from the agricultural sector in the beginning, over to the production and retailer, until the end consumer (restaurants will not be considered). The main focus of this work is the end consumer, the down-stream part of the supply chain because this is the biggest contributor to food waste. In the range of the end consumer especially the “Generation Y” is inspiring to

inspect since they are known as the generation of waste. This focus group has an enormous influence on the entire supply chain due to the “pull” principle (Klein, 2019). Their behaviour and possible changes are affecting the chain from the downstream to the upstream part and therefore the study is essential to close the recent gaps in research. The empirical study is conducted in a case study approach while execute online surveys with open-ended questions in the target group of “Generation Y”.

1.5 Definitions

Fruits and vegetables: Botanic describes “fruit” as the seeds and surrounding tissues of a plant and the term in culinary is pulpy seeded tissue with a sweet or tart taste. Vegetables are edible parts of a plant including i.e. roots, tubers, bulbs, and leaves (Pennington & Fisher, 2009). Food loss and food waste: Food losses occur in the early phases of the supply chain, i.e. after the harvest and in the processing phase. It is the number of edible foods and will also be considered as destruction (Gustavsson, Cederberg, Sonesson and, et al., 2011; HLPE, 2014; Parfitt et al., 2010).

Food waste tends to occur in the final stages, i.e. in the distribution and the consumer level. This is leftovers and completely disposed of food used i.e. in households and retailing destruction (Gustavsson, Cederberg, Sonesson and, et al., 2011; HLPE, 2014; Parfitt et al., 2010; Rezaei & Liu, 2017). Food waste can be distinguished in three different sectors. The first one is the avoidable food waste, which is defined as a food that has been fully enjoyable by the time of its disposal e.g. originally packed food or half-open packages. Second, is the partly avoidable food waste. It is waste due to consumer habits e.g. apple peels, potato skins. The last sector is the unavoidable food waste that is wasted due to preparation. These are mostly uneatable such as banana peels, coffee grounds, and bones (Kranert et al., 2012).

Sustainability: Sustainability focuses on meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs. Waste reduction is the principal factor in achieving sustainability of the food supply chains (Brundtland, 1987; Gokarn & Kuthambalayan, 2019). Environmental sustainability is often associated with the reduction of waste, pollution,

and emission as well as the efficient use of energy. Furthermore, it aims at reduced consumption of materials that are hazardous, harmful, or toxic (Gimenez et al., 2012).

Defined steps in the food supply chain:: In the literature, the areas of the food supply chain are classified and named differently (Caldeira et al., 2019; Gustavsson, Cederberg, Sonesson and, et al., 2011; Kelly et al., 2019). So the categories for this study are defined as follows: the supply chain starts with the agricultural sector, followed by the post-harvest sector, which includes processing, manufacturing, wholesale, and retailing, the last part of the supply chain focuses on the end customer.

Generation Y: This generation includes individuals born between 1980 and 1995. They are also termed as “Digital Lovers”, “Millennials” and “Facebook Generation”. These individuals are known as different from their predecessors and this generation is grown up with digitalization and globalization. They are noted as more culturally liberal and ethnically diverse (Kurzmann, 2015; Neuborne & Kerwin, 1999).

1.6 Outline

The second chapter is presenting some literature that has been written in the field, starting with a broader perspective for a common understanding up to a narrowed down part. The literature review is followed by a theoretical framework and a newly developed framework out of the literature These two parts are the base for the later following empirical study and analysis. Chapter four obtains the methodology for the study just been mentioned. Thereafter, the empirical findings will be represented in chapter fife. Summarizing, these findings will be analysed, discussed, and concluded in chapters six and seven.

2. Literature Review

________________________________________________________________________________________ The following chapter contains the study of the literature related to the topic food waste of ffv across the supply chain. It starts with a broad overview about the topics and in the end a narrowed down version of the most important sections is given. This chapter includes matters of supply chain, food waste, generations, and sustainability, which are supposed to support the answers to the research questions.

_________________________________________________________________________

2.1 Food supply chain

Food is processed throughout a supply chain that starts with the harvest and ends with the end customer. The food supply chain is responsible for the distribution and organisation of vegetable or meat-based products. It is possible to divide the supply chain into two different areas in a simplified way. On one hand, the supply chain for fresh products with an origin at the farm, which generally consists of the farmers, wholesalers and retailers, and shops. The main processes are storage, packaging, transport, and trading of the goods (van der Vorst 2000). On the other hand, the supply chain for non-fresh packaged products, where fresh products are used as raw materials that add value to another product. This type of supply chain goes through the same processes as fresh products. Usually, the processing procedure extends the life of the food products(Downey, 1996; Ozbuk & Coskun, 2020; van der Vorst 2000).

Further literature separates the supply chain into two areas. The part of primary production which includes agriculture, as well as industry, which comprises of food processing and manufacturing. This is then followed by the distribution and retail sector and ends with the end customer and households (Caldeira et al., 2019; Göbel et al., 2015).

As already mentioned in the previous paragraphs the food supply chain passes through many stations to get from the farmer to the end consumer. The first stage is referred to as the "upstream" supply chain and the end of the supply chain is called the "downstream". The structure of this supply chain can be generalized for each country and the food commodities. These can be divided into five sections: Starting with the agricultural sector, through storage and

handling, processing and distribution to the end customer (Gustavsson, Cederberg, Sonesson and, et al., 2011; Ozbuk & Coskun, 2020; S.D. Porter et al., 2016).

2.2 Food wasted across the supply chain in Europe

An in-depth study on food waste has been conducted by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) in 2011, even though it is already some time ago, the most relevant studies in this field refer to these data repeatedly (Gustavsson, Cederberg, Sonesson, van Otterdijk, et al., 2011). According to the HLPE (2014), approximately 1.3 billion tons of food are discarded every year and the increase in food loss and waste has been enormous in recent years. The world average per capita was 177 kg in 1961 and rose to 240 kg in 2011 and the developing countries increased more than developed countries. In Europe the increase was “just” 5% from 285 kg in 1961 to 298 kg in 2011, nevertheless, this was already far above the average in 1961 and is still much higher than today’s average (Gustavsson, Cederberg, Sonesson, van Otterdijk, et al., 2011; HLPE, 2014; S. D. Porter et al., 2016). It should also be noted that the largest food loss in the EU is caused by the United Kingdom. The United Kingdom is ahead of Germany, France, and the Netherlands (Richter & Bokelmann, 2016).

The greatest loss is indicated to occur in the manufacturing industry. For instance, 18% of the loss in Germany is generated by this industry. This is also confirmed by figures from Poland with a loss of 7 million tons (Mt), as well as the Netherlands and Italy with a loss of 6 Mt each (Monier et al., 2010; Richter & Bokelmann, 2016).

In 2012, 11 Mt of food were disposed of in Germany, which leads to an amount of food waste of 82 kg of every person per year (Eyerund & Neligan, 2017). In Spain, 20% of all food is thrown away or wasted and every Spanish citizen wastes an average of 180 Euros a year on food (Garcia-Herrero et al., 2018). Blanke (2015) also confirms the high number of food wastage with 71-92 kg per capita per year in western Europe, which amounts to 200 - 260 Euro per person per year. The impact of food waste on the economy in European countries is also estimated by another study to be 143 billion pounds (Raut et al., 2019).

2.3 Food wasted across the supply chain in Europe per food type

A study in Danish households has shown that the biggest areas of loss are fresh vegetables with 30% and fresh fruits with 17%. These are followed by bakery products accounting for 13%, corn and desserts with 12%, meat and fish with 7%, and eggs representing 5% (Porat et al., 2018). In Spain, analyses on food loss revealed that vegetables and fruits are the most ineffective sectors in the supply chain. The loss in this sector is calculated to be approximately 65 kg per person, capita, and year, which represents almost 60% of the total Spanish food loss (Garcia-Herrero et al., 2018). Fruits and vegetables are an important part of the supply chain, especially with a focus on environmental aspects. The products are often casually thrown away, still being unused and thus leading to high losses. The literature states that the average loss of food products is 35 %, ranging from producers to retail shelves to consumers’ refrigerators (Kaipia et al., 2013). Three product groups account for 80% of the mass of food waste in the last five decades, including ffv, cereals, and roots and tubers. The biggest change is in ffv, where annual global waste has increased from about 30% in 1990 to 42% in 2011 (S.D. Porter et al., 2016).

Figure 1 Caldeira et. al (2019): Waste of food in the EU in Mt

Caldeira et al. (2019) shows, the product group of fruits and vegetables are the largest in terms of food waste with around 50% and 68.7 Mt. Continuously, the study shows that this is the sector with the greatest potential for waste prevention. Caldeira et al. (2019) show that 41% of

wastage can be avoided in the fruit sector and 46% in the vegetable sector. This is also confirmed by another study that describes that 54% of food wastes can be avoided in the area of ffv (Blanke, 2015).

In summary, the literature presents a very high loss of vegetables and fruits. In most cases, this sector accounts for well over half of the total loss of food.

2.4 Food wasted across the supply chain in Europe per sector

Research confirms that there are many different reasons for food loss along the supply chain and the causes depend on the level at which they occur in the chain (Guiseppe et al., 2014; Lipinski et al., 2013; Richter & Bokelmann, 2016). Losses can arise at any point in the supply chain due to different circumstances and causes (Gustavsson, Cederberg, Sonesson and, et al., 2011). That the loss depends on the level and the type of food is also shown by a study of Caldeira et al. (2018), which describes that most food is wasted during the downstream phase of the supply chain - the end consumer. The amount of waste that is lost in this sector is comparable to the amount of fruit and vegetables that are wasted at all. In total 129,2 Mt of food was wasted in 2011 and the largest share of this is in the household sector, which accounts for 38% of the total waste (Caldeira et al., 2019; Gustavsson, Cederberg, Sonesson, van Otterdijk, et al., 2011). Blanke (2015) also confirms that private households are the biggest cause of food wastage. The study points to a loss of food in private households of 61%. The sector of the biggest loss is also confirmed by Porat et al. (2018) they are defining the consumption in households as the biggest sector of food loss with 28%. Additional literature examines the various aspects of food waste in their study and concludes that the largest area of food waste in Europe is households (Garcia-Herrero et al., 2018; Parfitt et al., 2010; Porat et al., 2018; S. D. Porter et al., 2016). However, there are also supplementary sources of food waste in the supply chain, even if they seem to implicate a minor role. In Sweden, for instance, as much waste is generated in the areas of industrial production, wholesalers and retailers combined as it is generated in households (Liljestrand, 2017).

Though it is not the same case for all types of food, some find their greatest loss in other phases of the supply chain, for instance, considering fish and sugar beets. In terms of fish, the biggest

loss area is in production and processing and for sugar beets it is in the agricultural sector (Caldeira et al., 2019). Also, Porter (2016) is defining the agricultural sector as the second biggest in terms of food loss. This is followed by the processing and distribution part and ends with transportation.

In general, distribution and retailing are the area where food losses are lowest with a waste of about 5%, followed by the primary production and processing and manufacturing sectors with about 25% (Caldeira et al., 2019). Other figures illustrate the production with 20%, the retail sector with 12%, and finally storage and packaging with a very small portion of 3% and 1% respectively (Porat et al., 2018).

Figure 2 Food waste percentage (Gustavsson, Cederberg, Sonesson, van Otterdijk, et al., 2011)

The figure above represents the FAO report, which includes an extensive and detailed study about food waste. The study is very detailed and a respectable source in terms of food waste, even if it is from 2011 it is taken into consideration for this figure. It contains seven different

2 20 10 20 3 9 4 4 9 1 5 1 1 1 10 15 5 2 5 6 1 2 7 1 12 4 14 1 25 17 4 34 11 21 7 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 Cereals Fresh roots and tubers Oilseeds and pulses Fruits and vegetables Meat Fish and Seafood Milk and Egg

Food waste percentage in Europe

Agricultural production Postharvest handling and storage Processing and packaging Distribution

types of food and examines the loss in a wide range of areas. The findings indicate that the area of households or end consumers is the largest in most cases. Exceptions are oilseeds and pulses and fresh roots and tubers, for these the agricultural sector is the one that wasted the most. But all in all, this study supports the results of the previously mentioned studies, the largest contributor of waste is the consumer sector, followed by agriculture. It is succeeded by processing, packaging, and distribution (Gustavsson, Cederberg, Sonesson, vanOtterdijk, et al., 2011)

2.4.1 Reasons for the waste of ffv in the agricultural sector

The significance of the agricultural sector in terms of the total quantity of food waste accumulated along the food supply chain can be considered important. It represents a substantial portion i.e. 35% of all the food wasted along the food supply chain (Gustavsson, Cederberg, Sonesson, vanOtterdijk, et al., 2011)

Ffv that fail to meet the aesthetic quality are discarded from the food supply chain, having never got past the supplier, or even left the farm (Porter et al., 2018). This unfavourable practice takes quality and commercial requirements into consideration and no standard regulations. Retailers and consumers alike demand perfect appearing ffv from the farmers and the food industries. This phenomenon has already been discussed in previous studies (Parfitt et al., 2010).

Managing ffv supply chains is a highly daunting task due to their specific attributes. Ffv have considerably high perishability (Balaji & Arshinder, 2016). The major forces behind the wastage of ffv in pre-harvest or agricultural production stage are aesthetic imperfection, overplanting, damage, and quality (Gustavsson, Cederberg, Sonesson and, et al., 2011; Gustavsson, Cederberg, Sonesson, van Otterdijk, et al., 2011; Porter et al., 2018). These two forces are intertwined as farmers have to contractually obliged to provide a particular amount of products that should meet certain standards (Beretta et al., 2013; Halloran et al., 2014). Numerous studies consider avoidable food loss due to aesthetic standards and its impact on the environment due to greenhouse gas emissions. However, the major reason for food waste in the production phase is unanimously considered to be an accidental loss, such as from hazards and natural crop diseases (Gille, 2012). Another reason that results in food waste such as processing waste, lack of adequate infrastructure, for instance, cold-storage facilities and process contamination (Balaji

& Arshinder, 2016). Furthermore, food waste results out of payments of subsidiaries to specific commodities in the food area, which leads to a waste of more than 50%, that is directly destroyed at the farm (S. D. Porter et al., 2016).

It is important to note that wastage of food at the level of agriculture may have different reasons depending upon different regions. In the context of industrialised countries, a surplus of food is produced which cannot be sold due to not meeting certain requirements concerning size, colour, shape as well as visual requests. This results in food wastage after harvest and the products are not harvested at all but are ploughed into the soil (Felicitas, 2011). However, in the context of developing countries, a lack of proper infrastructures such as cold chains and adequate storage places leads to a loss of ffv. Wastage amongst perishable products and their crops such as ffv are generally higher than for other food products. This wastage is estimated to be a staggering 25-40 % higher than wastage of regular food products (Parfitt et al., 2010).

2.4.2 Reasons for the waste of ffv in post-harvest

The significance of the retail phase in terms of the total quantity of food waste accumulated along the food supply chain is considered as important. However, it represents a relatively small percentage i.e. 5% of all the food wasted along the food supply chain (Buzby & Hyman, 2012). Previous studies show that ffv are the major contributor to food waste among the retail sector. These critical products consist of a very short shelf life, generally two weeks and in some instances only 2-3 days (Balaji & Arshinder, 2016; Mena et al., 2011). Quality is often the key component due to their highly perishable nature, postharvest handling requirements, and their outward appearance (Kelly et al., 2019). At their delivery to the retail store, ffv go through acceptance or rejection depending upon their quality standards (Eriksson et al., 2012; Eriksson et al., 2015; Mattsson et al., 2018).

Apart from quality control, wastage of ffv usually occurs due to natural deterioration, handling damage, shortfalls in transportation methods, unsuitable packaging, and nearing or passed expiry dates(Buzby et al., 2011; Gustavsson, Cederberg, Sonesson, vanOtterdijk, et al., 2011). Additionally, a few other uncommon factors might also implicate in wastage of food. Firstly, batches that fail or look not appealing as they should, for instance, due to a difference in either the production method or natural raw materials. Secondly, spillage on conveyor belts and at transfer points. Thirdly, dust extraction to maintain safety at a working environment and lastly,

unforeseen equipment failures resulting in an operational bottleneck (Verghese et al., 2015). Retail stores sometimes also dispose of these products due to sub-optimal stock rotation and overstocking (Buzby et al., 2011).

It is also noted that sometimes inadequate temperatures and their management may result in spoilage or wastage up to 50% (Kelly et al., 2019; Raut et al., 2019). In addition to that, current refrigeration equipment used in ffv storage are usually set at adequate temperatures, but in reality, the temperatures inside the display can be variable (Kelly et al., 2019).

2.4.3 Reasons for the waste of ffv at the end consumer

The biggest share of food waste in developed countries occur at the consumption stage (Lipinski et al., 2013; Stancu et al., 2016). In terms of food wasted by consumers, it is estimated to represent upwards of 50% of the total food waste in Europe (Kummu et al., 2012). This large figure of food waste at the consumer level should act as an indicator to reduce food waste at the last stage of the supply chain to ensure greater sustainability (Parfitt et al., 2010). Thus, if food is wasted by consumers then the resources invested into its harvesting, production and processing, transportation, cooling and preparation will no longer carry any value.

There are several reasons that lead to the wastage of ffv at consumer level such as a lack of food-related planning, inadequate storage facilities, retail discounts, perceived social norms, mould, expiring date, leftovers that do not attract any more, and aesthetic qualities (Gaiani et al., 2018; Porter et al., 2018). Unexpected changes may result in food being thrown away even for consumers who properly plan their food purchases. Hence, food-related planning is an essential part of the buying pattern of consumers (Aschemann-Witzel et al., 2015). Consumers often cannot assess the ripeness and freshness of these ffv and in these circumstances, the previous purchase might be replaced by “newer” and ”fresher” products (Porat et al., 2018).

Inadequate storage facilities also play a major role in the premature disposal or wastage of ffv. As it is evident that temperature is an important variable in terms of the maintenance of ffv quality, keeping and storing ffv at ambient or room temperature. If not properly maintained, its will strongly contribute to quicker spoilage (Rollin et al., 2011).Another concern for consumers who do store properly is that, ffv if stored for longer periods might get contaminated due to cross-contamination with other food items (Waitt & Phillips, 2016).

Retail discounts are often drivers of food waste as retailers try to persuade consumers to buy larger quantities of ffv than they can consume. For instance, retail stores offer various promotions, price discounts, and several other marketing tools designed to trigger impulse buying behaviours (Jaeger et al., 2018). This particular merchandising behaviour leads to over-stocking and later complete deterioration thereby passing on the retailer’s ffv risks onto the consumers (Porat et al., 2018).

Social norms and values can be considered as subjective by the consumers. However, some consumers consider immediate and unhindered access to ffv in their homes as a source of an acknowledgement as it is embarrassing to not have ffv (Campbell et al., 2009). Consumers objective to be always accommodating will then contribute to being overcompensating when purchasing, and later on failing to consume all the purchased ffv. This is a common practice of many consumers and it is widely regarded as poor predictors of compliance even if the intentions of the consumers were positive (Bowman et al., 2004)

Aesthetic requirements are a significant part of quality standards for ffv that are produced and sold in Europe (Porter et al., 2018). Along with the time that ffv have been bought and stored at their homes, consumers also take into account the outward appearance of ffv, for instance, visual discoloration shrivelling, wilting, deformities and bending that arise due to awkward storage position (Normann et al., 2019; Porat et al., 2018). Most of the time, consumers throw ffv away solely based on their outward appearance. It occurs seldom that consumers smell or taste fruits before deciding that it should be thrown away (Campbell et al., 2009; Evans, 2011).

2.5 Generations

A generation is a group of people of the same age, similar views of life, and social orientation. Generations are shaped by certain events such as occurrences in politics and society. This leads to the development of individual norms and preferences (Mangelsdorf, 2015).

Further studies do also support the assertion that social, political, and economic events affect individuals of a certain age (Patota et al., 2007). Supplementary research claims that differences between generations are due to the belief that people change their values and attitudes with their ages. They also state that the values of a generation last a lifetime and are resistant to change (Arsenault, 2004; McGuire et al., 2007; Rood, 2010).

The different generations can be divided into five diverse groups. Beginning with the "Mature", which represents about 13.7 million people and whose years of birth are between 1922 and 1945. This is followed by the generation of the "Baby Boomers", which correspond to approximately 20.7 million people and this generation was born between 1946 and 1964. The succeeding generation is "Generation X", which amounts to about 17.8 million people and was born between 1965 and 1979. Afterward the "Generation Y" or “Millennials” with roughly 14.8 million people whose years of birth are determined to be 1980 – 1995 succeed. Last but not least is "Generation Z", which was born from 1996 onwards and includes so far nearly 14.7 million people (Mangelsdorf, 2015; Rood, 2010).

As explained at the beginning of the chapter, all generations are shaped by different events that determine certain values. The "Matures" through the Second World War and the Great Depression, which shaped them to be hard workers with high respect for authorities. (Rood, 2010). The "Baby Boomers" experienced the women's movement, the economic revolution, and the building of the Berlin Wall in Germany, which leads to the characterization of conflict-shy, energetic, and optimistic. For "Generation X" the oil crisis, the fall of the German Wall, Chernobyl, and AIDS are major events to mention, which formed the core values of diversity and informality. "Generation Y"s defining moments are terrorism, globalisation, climate change, and helicopter parents, which characterise the values optimism, sustainability, and achievement (Mangelsdorf, 2015; Rood, 2010). For the "Generation Z" the mobile phone, the economic- and financial crisis, and the "Crown Prince Childhood" are the defining moments. Their values are demanding and realistic (Mangelsdorf, 2015).

In terms of food disposal, a clear pattern is identifiable. Generations that were born close to the war or in times of war are the very least in discarding food. One-third of the people born before World War II never throw food away. In the case of the “Baby Boomers”, the percentage of people who dispose of food is 16%, they do not just discard edible food without thinking about the value of it. One in four people in this generation throws away food once a week. More often food is disposed of by "Generations X and Y". Only 8% of both generations never throw food away (Eyerund & Neligan, 2017).

2.6 Generation Y

“Generation Y" is marked by the permanent threats of environmental pollution, global warming, and natural disasters. However, they are not afraid of this threats and enjoy their lives to the full. Parents spoiled this generation and strengthened the self-esteem of their children and nothing was too expensive for them. They had the world wide web as their playground and full access to all information around the world. Their attitude towards work is not to earn money but to realize themselves and they are very demanding and erratic. Nevertheless, sustainability plays a crucial role in their lives and the value of their generation (Mangelsdorf, 2015).

“Generation Y” is particularly studied due to the large difference between embedded values and action. On the one hand, this generation is known for the fact that values for environmental protection and sustainability are very important to them, on the other hand, they are called the generation of waste. Klein (2019) claims in her study that every eighth food product purchased by consumers is discarded. A large proportion of this waste is due to “Generation Y”. Severo et al. (2018) describes “Generation Y” as a generation with a lesser understanding of socio-environmental practices. It is claimed that despite access to any information, for instance via social media, this generation has no socio-environmental awareness. According to the study, it is important to drive this generation to a behaviour of environmental awareness and sustainable consumption (Severo et al., 2018).

36% of the people in “Generation Y” do discard food at least one time per week. Furthermore, there are people belonging to this generation who throw away food every day – even if it is a much smaller part with 3%- it is very relevant to mention. Eyerund and Neligan (2017) also describe in their study, that just 8% of the people in “Generation Y” do not dispose of food regularly, which means that 92% do so. This is a very enormous part of people that can cause an immense difference with their behaviour in the whole consumption sector in terms of food disposal (Eyerund & Neligan, 2017).

2.7 Sustainability

There is a wide range of literature available on this subject. The foundation for sustainability was described as a development that meets the needs of the current situation without compromising

the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. (Brundtland, 1987). Concerning the promotion of sustainability and the environmental awareness, it is stated that sustainability is the responsibility of the consumers to make decisions to live in such a manner that the resources are not used up faster than they regenerate. (Sandhu et al., 2014). Both of the declarations refer to the possible behaviour of future generations with regards to food production and consumption patterns as well as preserving natural resources. To be more sustainable, a collective effort is required to reduce waste as much as possible.

Sustainability is a field that revolves around continuous improvement and adaptation to new conditions (Ianos et al., 2009). According to Gustavsson et al. (2011) 1.3 billion tons of food is wasted annually out of which 50% comprises of ffv. This is a situation that requires immediate attention and action as this huge amount of food wastage also leads to greenhouse gases being released into the atmosphere. The greenhouse gases are equivalent to 3.3 billion tons of CO2 annually, costing approximately 750 billion dollars and water equivalent to the yearly flow of Russia’s Volga River (Eriksson et al., 2015). Additionally, rapid population growth, increasing demand for ffv, and the behavioural consumption patterns have resulted in intensive use of energy resources. These energy resources spent on agri-food industry along with its greenhouse gas emission go as high as up to 30% of the total energy resource generation (Garcia-Herrero et al., 2018). Food waste is classified as a major global concern that puts the environment, economy, and health security at risk (Stoessel et al., 2012).

2.8 Sustainability issues due to ffv

It is challenging to describe the true meaning of sustainability in the context of food waste specifically for ffv. The impacts of ffv production are considered in various categories of environmental impact such as climate change, impacts of land and water use, and eco-toxicological effects (Stoessel et al., 2012). The production of ffv and its proper disposal once it has been lost or wasted requires energy and water resources. Ranging from early agricultural harvesting down to the end consumer, the embodied amount of energy builds up along the chain. It means the later the waste happens, the bigger the energy wastage and greenhouse gas emissions will be (Scherhaufer et al., 2018). According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), upwards of one-third of the food production globally is

lost along the supply chain which incurs about 38% of the energy. In addition to that, it is estimated that food production and global energy consumption are expected to rise by 50% respectively by the year 2050 (Garcia-Herrero et al., 2018).

Another phenomenon associated with environmental hazards due to wastage of ffv is an increasing demand for water along with its continuous depletion. Water footprint studies have garnered significant attention in the area of food production, showing the high usage of water and its related impact (Hoekstra & Chapagain, 2007). It is calculated that currently 30% of the total water consumption is extracted from overuse of non-renewable groundwater resources. This is estimated to increase to 40% by the end of the century (Liu et al., 2017). The issues due to water depletion pose numerous potential environmental hazards, including the loss of biodiversity (Parajuli et al., 2019). Thus, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) is developing a benchmark on water footprint which would ascertain thorough analysis and reporting for product labelling (Stoessel et al., 2012). With this proportional increase in resource consumption over the years, more efficient usage of energy and water resources is an essential step towards reducing environmental issues, preserving natural resources, and promoting food sustainability (Yakovleva, 2007).

3 Theoretical framework

________________________________________________________________________________________ In the following paragraph a model is designed, to fulfil the research strategy and test the theory. The particularly developed Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) model for the disposable behaviour of “Generation Y” is based on the original TPB model from Ajzen (1991) and two modified versions. The model serves as a base for the empirical part of the study and its attitudinal factors will be tested at the end of the study.

_________________________________________________________________________ The base of the theoretical framework is built by the TPB, which is based on the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA). According to the TRA, behaviour is completely determined by an intention to behave. It was developed by the Islamic-American sociopsychologist Icek Ajzen and the American psychologist Martin Fischbein in 1980. Ajzen later modified this theory into the TPB. Both theories have since become popular models of the relationship between behaviour and attitude (Ajzen, 1991; Bamberg & Schmidt, 1999; Frey et al., 1993).

The TRA is an attitudinal model for predicting behaviour related to attitudes. According to the model of TRA is the behavioural intention a result of the personal attitude and from subjective norms that a person perceives. These norms are social assumptions that affect the intentions to act. In this model, it was found that behaviour is not always voluntary and under control. Based on this discovery, a successor model was developed by Ajzen (Ajzen, 1991; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980).

Therefore, an additional variable is added at TPB to complete and optimize the model. This variable is called perceived behavioural control (PBC) and can be used to predict the desired behaviour and intentions of individuals. This, in turn, indicates the willingness to act (Ajzen, 1991).

The TPB consists of three variables which are independent of each other and represent the determinant for behavioural intentions (Ajzen, 1991). These three components are “attitude towards behaviour”, “subjective norm”, and “perceived behavioural control”, which are presented and explained hereafter.

Attitude towards behaviour:

“the degree to which a person has a favourable or unfavourable evaluation or appraisal of the behaviour in question” (Ajzen, 1991 p.188). It means that the attitude is created by the behavioural belief individuals have about an entity (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980).

Subjective norm:

”the perceived social pressure to perform or not to perform the behaviour” (Ajzen, 1991 p.188). It describes the normative beliefs of an individual group that lead to certain behaviour in some situations (Ajzen, 1991).

Perceived behavioural control

“the perceived ease or difficulty of performing the behaviour and it is assumed to reflect experience as well as anticipated impediments and obstacles” (Ajzen, 1991 p.188). Prediction of volitional behaviour that indicates a readiness that an individual performs a specific action (Ajzen, 1991).

Figure 3 Theory of Reasoned Action and Theory of Planned Behaviour, (Ajzen, 1991)

This model is used frequently to predict general behaviours. It is known as very effective in terms of estimating an action and this is confirmed by several studies (Albarracin et al., 2001; Olsson et al., 2018; Sheeran, 2002).

3.1 Selected modified models of TPB

Nevertheless, numerous researchers have modified the general model of Ajzen (1991), to better serve their own and specific research purpose.Some studies must adapt the model towards the topic of the research to get an ideal outcome. The TPB allows these adaptions when it serves a better knowledge about the behaviour as a final achievement (Ajzen, 1991).

3.1.1 Modified TPB by Tarkiainen and Sundqvist

The study by Tarkiainen and Sundqvist (2005) is an adapted version of the TPB model. It investigates the buying behaviour of consumers in terms of organic food. In this version, the variable subjective norm and the newly added variable health consciousness should indirectly influence the behavioural intention through attitude. In this model, the variable health consciousness was added because the authors assumed that it is an important factor in terms of buying organic food (Zanoli & Naspetti, 2002).

Further, the model is extended by two additional factors, as they are the importance of the price and availability of the products. It is reasonable that an increased price and a lack of availability influences the positive attitudes towards the purchase behaviour of organic food. For instance, a too expensive price and a gap in product availability leads to the fact that no purchases will be made (Tarkiainen & Sundqvist, 2005).

The adaptations of the model were made in the area of moral in decisions, where behavioural intentions only indirectly intervene via attitude. It was assumed that buying organic food is a moral decision with a benefit for the environment and the individual itself. Finally, the study showed that it is possible to predict buying behaviour for organic food and the intention to buy is influenced by attitude and subjective norms (Tarkiainen & Sundqvist, 2005).

Figure 4 Adapted TPB model of Tarkianien & Sundqvist (2005) about the buying behaviour

3.1.2 Modified model of Chu

Such as the previously presented model by Tarkiainen and Sundqvist, the model of Chu (2018) is a modified version of the TPB model as well. It is supposed to investigate the buying behaviour of consumers in China in terms of organic food.

This model has a different structure than the predecessors it is based on internal and external factors. These factors are notorious for controlling consumer behaviour and influencing the buying behaviour of organic food (Mohiuddin et al., 2018). It defines a new variable - the marketing communication - which together with the subjective norms forms the external factor. For this model, the variable of marketing communication was significant to determine how it affects the buying behaviour of organic food. For the internal factors, price and health consciousness are taken into account as well as in the previous model (Tarkiainen & Sundqvist, 2005). As an additional factor, environmental awareness is added to the model and completes the internal factors (Chu, 2018).

It was determined that consumers are changing their attitudes towards the environment positively through healthy and ecological behaviour. According to the study, producers and

sellers should label and promote organic products. That leads to a benefit in profit, the environment, and the individual consumer. The sellers are advised to inform consumers why organic products are possibly more expensive and should make the whole process transparent. This will lead to more understanding and purchase of these products by end consumers. It is very important to let the customers know that they are essential factors for the environmental protection. While they understand this fact, their behaviour will lead to the sales of more organic products (Chu, 2018).

Figure 5 Adapted TPB model of Chu (2018) about the attitude towards organic food

It was demonstrated in the previous two examples that the original model of TPB still works in an adapted form and can predict the behaviour. The authors can exchange or add various factors that they considered important for their study (Chu, 2018; Tarkiainen & Sundqvist, 2005).

3.2 Proposed theoretical framework

For this study, too, an adapted model of the TPB is to be developed that is better suited to the purpose of the research and thus a more accurate result can be achieved. It is not relevant for this research how people's buying behaviour is influenced by different variables, but their

disposable habits. Changing the purpose causes a modification of the remaining factors and based on the literature and the previous models the following TPB model is proposed.

Figure 6 Adapted TPB model about the attitude towards disposal pattern of ffv

The concept is a combined version of the two modified models of TPB presented above. It takes up the division of the variables into internal and external attitudinal factors, which occur in Chu's (2018) model. These factors influence the consumers and are supposed to impact their decision of food disposal. The following external attitudinal factors have to be considered for disposable behaviour. The first component is price and marketing perception and how these two influence the disposable process. Do people, for instance, dispose of a product purchased for a higher price less than a cheaper one (Chu, 2018; Tarkiainen & Sundqvist, 2005). Three additional factors came up in the literature review, which intends to play a role in the external factors. The first of these variables that affect the disposal process is storage habit and how these are affecting the behaviour. Secondly, the quality consciousness and especially the appearance of ffv is a relevant factor for this study. The last point of external factors is the awareness of discard of people and if a higher awareness leads to different disposable behaviour among consumers.

For the internal attitudinal factors that influence the behaviour towards the disposal pattern of ffv, a very important point is the sustainable and environmental awareness. It has to be established whether people change their habits towards disposal when they are more aware of the damage to the environment. Furthermore, health consciousness has to be added, and the connection between unhealthy and imperfect ffv has to be identified. Do people throw away ffv because they no longer appeal "good" and do they associate this with harm to their health (Chu, 2018)? Finally, the subjective norm follows, where we investigate whether people only have fruit and vegetables at home because society "demands" it and most of the products are not eaten but disposed of (Ajzen, 1991).

All the factors mentioned above might influence the attitude towards disposal patterns of ffv according to the literature and the previous models (Chu, 2018; Tarkiainen & Sundqvist, 2005). This leads to a better interpretation and identification of the behaviour of the respondents (Ajzen, 1991), which helps to answer the research questions. Individual factors, which have been identified in the literature as the main reasons for disposal in the consumer sector, contribute to this, which are taken into account in the adapted model. These can be used to determine how “Generation Y” relates to the individual variables and how their behaviour concerning disposal could be influenced by these attitudinal factors. By using this model as a base for the questionnaire, the behaviour that is determined by attitudinal factors of “Generation Y” should be evaluated. Also, the aim of how the attitudinal factors of “Generation Y” affect the supply chain of ffv should be discovered.

4. Methodology

________________________________________________________________________________________ This chapter leads through the process of the empirical study that will be accomplished for this research. First, the research philosophy is defined followed by the research approach. This is succeeded by the research design and the data collection. This section concludes with the analysis and quality of this research.

_________________________________________________________________________

4.1 Research Philosophy

The comprehension of the philosophical point of view is very important in terms of conducting research as it has a significant impact on the formulation of the study and its results. It brings clarity to the research design, presented views and it also shows possible limitations with the research approach (Easterby-Smith, 2002; Easterby-Smith et al., 2015). The research philosophy is divided into two parts namely; ontology and epistemology.

The ontological viewpoint of this study is focused on relativism. This is due to its view that the truth can be variable or subjective depending upon the place and observers’ varying outlooks. The basis of the survey is on the words of the respondents. Hence, the “truth” can be variable due to different individual experiences. Therefore, we have decided to have the relativist ontological approach. Although the individual factors in the model are checked for their "truth", opinions of the survey participants may differ on the topics. Disposable behaviour could, for instance, be influenced positively or negatively by quality. This is why the relativist theory is applied, which emphasizes several truths (Easterby-Smith, 2002).

The emphasis of epistemology is on the most appropriate ways of questioning the world and gives us the nature of knowledge while ontology emphasizes the nature of reality (Easterby-Smith et al., 2015). The major epistemological viewpoints are constructionism and positivism. Constructionism perspective is that the world is a subjective plane that thrives through shared assumptions. Positivism, on the contrary, states that all information and theories that subsist, can be calculated with the use of logical facts without a subjective input and therefore the world’s existence is objective (Easterby-Smith, 2002; Easterby-Smith et al., 2015). The process of selecting the right epistemology for the study is highly important as it regulates the guidelines of the study itself. Easterby-Smith et al. (2015) viewpoint about positivism is that it gives an optimum process of investigating human and social behaviour. This is the reason that this study

will be based on a positivist perspective. A positivist perspective is more appropriate for this study due to its strength in understanding people’s behaviour. Furthermore, the ability to explain and test existing data and theoretical aspects of the study is another convincing aspect.

4.2 Research Approach

The research approach deployed in the thesis is qualitative. Easterby Smith et al. (2015) are describing the qualitative approach as a data-gathering in a non-numeric way. Data can be gathered in the form of open-ended questions and written comments on questionnaires, testimonial, individual interviews, observations, case studies, etc.(Taylor-Powell & Renner, 2003).The significance of a qualitative style of research is also defined by Easterby Smith et al., (2015) as: ”Qualitative research is a creative process, which aims to understand the sense that respondents make of their world. If done well, processes of data collection can be beneficial for everybody involved, both researchers and participants” (Easterby Smith et al., 2015, p.378). There are two objectives for selecting the qualitative research method. Firstly, a qualitative approach involves a research strategy expressed by interpretivism. For a study marked by interpretivism, the researchers search for an understanding within the consumers´ subjective experiences instead of looking at the data at hand objectively (Bryman & Bell, 2011). Secondly, in the field of consumer perception and associated behaviour, it is necessary to get a thorough understanding of the basic reasons. The aim is to understand the attitudinal factors of “Generation Y” that affect the behaviour and the effects regarding sustainability and supply chain. Asking questions and then analysing the answers of individuals provide the best answers to these questions. In addition to that, since there is minimal research conducted in food wastage from a consumers’ perspective, important insights and ideas can arise by conducting qualitative research. For this research, open-ended survey questions are used in a questionnaire in order to obtain the most accurate and broad information on the topic.

A deductive approach will be implemented for this research with the objective to test the theory and check which attitudinal factors influence the behaviour of consumers of

“Generation Y”. This is due to the deductive approach to create a theoretical framework in addition to supporting the epistemological position of positivism (Bryman & Bell, 2011; Saunders et al., 2016). A deductive approach is creating a research strategy and theory out of

the literature. This particular approach was adopted since it complies with the qualitative method of data collection (Saunders et al., 2016). It is essential for studies that are aimed at finding new relationships and variables. The primary objective concerns on empirical findings and from there the development of theoretical models. It focuses on exploring existing concepts and developing those concepts in line with existing theories rather than creating new theories (Saunders et al., 2016). Adapting the deductive approach for this study the first step is finding a theory, which is based on the literature review. Afterwards, an assumption to test the theory shall be developed, which is used as a revised TPB model in this research. This model is developed from the preceding literature on the issue of food waste and from already existing TPB models. In the next step of the deductive approach, the model needs to be tested. This is done by collecting data through open-ended survey questions, to investigate if the theory is really fitting to the actual behaviour of the people in “Generation Y”. In the last step, the model will be confirmed or rejected with the results obtained. However, it is important to note that the study could also have been conducted following an abductive approach. The abductive approach is known as a mixture of deductive and inductive approaches. The objective is to generate new concepts from pre-existing theoretical models, rather than confirmation of the existing theory. Since, our aim is to develop the existing theory, using existing literature to extend the tested model, in order to make additions to the theory on food waste management from a consumer’s perspective, we believe the deductive method to be the most suitable approach.

4.3 Research Design

The research design is intended to be a link between philosophy and the method of data collection. It serves as a methodological link between these two elements and should fulfil the research purpose and answer the research questions. The design determines the quality of the study, as it confirms the assumed theories of the research philosophy (Easterby-Smith et al., 2015; Saunders et al., 2016).

As already explained, a deductive research approach is selected to validate the theoretical findings, and the research obtained up to now. It represents a suitable evaluation design in this research approach for the survey strategy (Saunders et al., 2016). Survey research with