The effect of marketing

appeals on consumers’

intention to pro-environmental

behaviour

BACHELOR’S DEGREE

THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Marketing Management AUTHOR: Senja Lunden, Aya Suliman & LisaBeth Sundström JÖNKÖPING May 2020

A social marketing study applying the Theory of

planned behaviour in Jönköping, Sweden

i

Bachelor Thesis in Business Administration

Title: The effect of marketing appeals on consumers’ intention to pro-environmental behaviour – A social marketing study applying the Theory of planned behaviour in Jönköping, Sweden

Authors: Senja Lunden, Aya Suliman & LisaBeth Sundström Tutor: Jenny Balkow

Date: 2020-05-13

Key terms: “Social Marketing”, “Theory of Planned Behaviour”, “Marketing Appeals”, “Intention to Behavioural Change”, “Palm oil”

Abstract

Background: Due to increasing environmental issues, the social marketing efforts from

organisations are increasing with the aim to push for more sustainable behaviour. One recurring issue in these campaigns is palm oil production. Generally, social marketing relies on negative emotional appeals, such as fear, shame, and guilt, to generate desired responses to the message. This paper focuses on the use of both positive and negative emotional appeals in social marketing within the area of environmental sustainability.

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to examine the relationships between the elements of the

theory of planned behaviour with the addition of the social marketing appeal and how it, in turn, affects the intention to avoid palm oil. Further, the research aims to study the effects of positive emotional appeals within pro-environmental social marketing.

Method: To conduct this study, a quantitative approach was taken. Two questionnaires were

made with the aim to measure respondents’ motivational factors leading to an intention to behavioural change based on the marketing appeal. One questionnaire included an advertisement using a positive appeal whereas the other utilised a negative appeal.

Conclusion: Both marketing appeals show positive relationships between the elements in the

adapted theoretical framework, with perceived behavioural control being the strongest predictor of the intention to behavioural change. Further, it was discovered that the financial factor can be important to consider when it comes to sustainable consumption.

ii

Acknowledgements

We want to express our gratitude to all of those who contributed to and facilitated the process of this thesis.

First, we want to thank our tutor, Jenny Balkow, for her support. Through her critical eye and her engagement, she has pushed us to always strive to be better and to keep on working. We would also want to thank all the students who participated in our study and our friends who forwarded our questionnaire to their contacts.

Last, but not least, we want to thank Toni Duras for his time and kind guidance of statistics and SPSS.

Senja Lunden Aya Suliman LisaBeth Sundström

__________________ __________________ __________________

iii

Table of Contents

1. INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1 BACKGROUND ... 2

1.1.1 Defining Social Marketing ... 3

1.1.2 Differences and Similarities between Commercial Marketing and Social Marketing ... 5

1.1.3 Appeals in Advertising... 6

1.2 PROBLEM STATEMENT ... 6

1.2.1 Purpose ... 7

2. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND ... 8

2.1 VALUE-ACTION GAP... 8

2.2 THEORY OF PLANNED BEHAVIOUR ... 9

2.2.1 Attitudes ... 10

2.2.2 Subjective Norm ... 12

2.2.3 Perceived Behavioural Control ... 13

2.2.4 Intention... 14

2.3 APPEALS... 15

2.4 ADAPTED THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ... 18

2.4.1 Problem Formulation ... 19

3. METHODOLOGY AND METHOD ... 21

3.1 METHODOLOGY ... 21 3.2 LITERATURE REVIEW ... 21 3.3 QUANTITATIVE SURVEY ... 22 3.3.1 Video Advertisements ... 23 3.3.2 Pilot Survey ... 23 3.3.3 Sampling ... 25 3.3.4 Questionnaire Design ... 26

3.4 CODING OF THE DATA ... 27

3.4.1 Coding of the Open-Ended Questions ... 28

3.5 STATISTICAL ANALYSES ... 29

3.6 ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS ... 30

3.6.1 Validity of Research ... 31

4. RESULTS... 32

4.1 DEMOGRAPHIC AND CHARACTERISTICS OF RESPONDENTS ... 32

4.2 CONSTRUCTS... 32

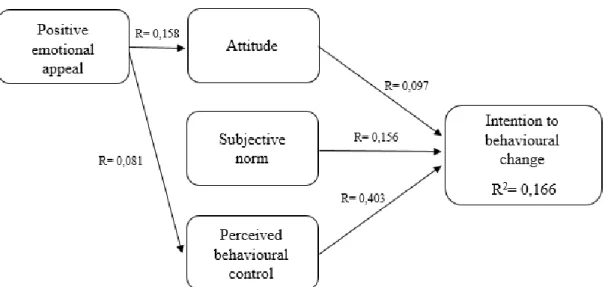

4.3 EMPIRICAL FINDINGS FOR THE POSITIVE EMOTIONAL APPEAL ... 34

4.4 EMPIRICAL FINDINGS FOR THE NEGATIVE EMOTIONAL APPEAL ... 35

5. ANALYSIS ... 37

5.1 RELIABILITY TESTING... 37

5.2 MULTIPLE LINEAR REGRESSION ... 39

5.2.1 Assumption of Continuous Variables ... 39

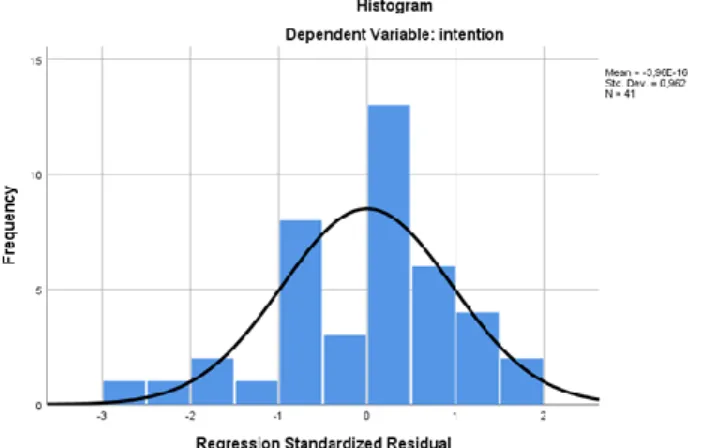

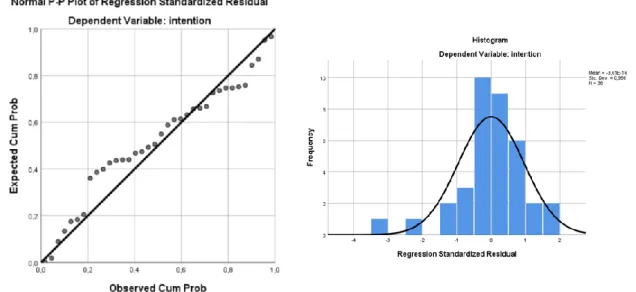

5.2.2 Normality of the Residuals ... 40

5.2.3 Multicollinearity Diagnostics ... 41

5.3 MULTIPLE LINEAR REGRESSION ANALYSIS ... 42

5.3.1 Testing for Attitude and Perceived Behavioural Control as Dependent Variables ... 42 5.3.2 Evaluating Independent Variable for the Attitude and Perceived Behavioural Control . 43

iv

5.3.3 Testing for Intention as the Dependent Variable ... 44

5.3.4 Evaluating the Independent Variables for the Intention ... 45

5.4 HYPOTHESES TESTING ... 46

5.4.1 Hypothesis 1 ... 47

5.4.2 Hypothesis 2 ... 47

5.4.3 Hypothesis 3 ... 48

5.4.4 Hypothesis 4 ... 48

6. INTERPRETATION OF THE ANALYSIS ... 50

6.1 GENERAL ANALYSIS ... 50

6.2 EMOTIONAL APPEAL ... 51

6.3 ATTITUDE... 52

6.4 SUBJECTIVE NORM ... 53

6.5 PERCEIVED BEHAVIOURAL CONTROL ... 54

6.6 INTENTION ... 54

7. CONCLUSION ... 56

8. DISCUSSION ... 58

8.1 IMPLICATIONS ... 58

8.2 LIMITATIONS AND FURTHER RESEARCH ... 59

REFERENCES ... 61

v FIGURES

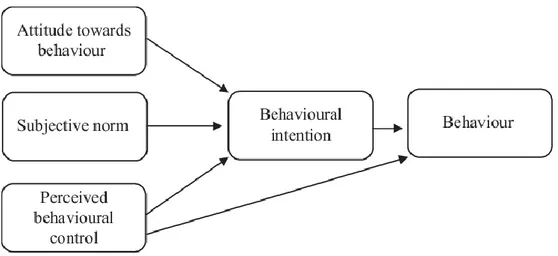

FIGURE 1:THEORY OF PLANNED BEHAVIOUR ... 10

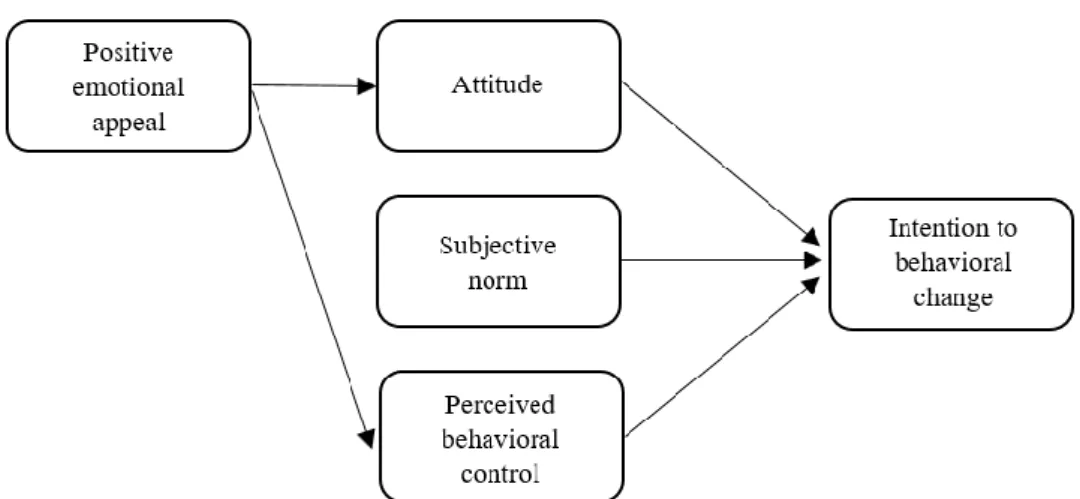

FIGURE 2:THE ADAPTED THEORY OF PLANNED BEHAVIOUR FRAMEWORK WITH THE POSITIVE APPEAL ... 18

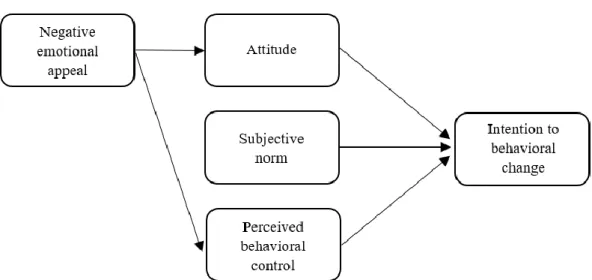

FIGURE 3:THE ADAPTED THEORY OF PLANNED BEHAVIOUR FRAMEWORK WITH THE NEGATIVE APPEAL ... 19

FIGURE 4:REGRESSION ANALYSIS FOR THE POSITIVE APPEAL ... 35

FIGURE 5:REGRESSION ANALYSIS FOR THE NEGATIVE APPEAL ... 36

FIGURE 6:NORMALITY OF RESIDUALS FOR POSITIVE APPEAL ... 40

FIGURE 7:NORMALITY OF RESIDUALS FOR NEGATIVE APPEAL ... 41

TABLES TABLE 1:CRONBACH'S ALPHA... 38

TABLE 2:MULTICOLLINEARITY... 42

TABLE 3:ANOVAS FOR POSITIVE APPEAL ... 43

TABLE 4:ANOVAS FOR NEGATIVE APPEAL ... 43

TABLE 5:CONSTRUCT ANALYSIS FOR APPEAL AS AN INDEPENDENT VARIABLE ... 44

TABLE 6:ANOVAS FOR MULTIPLE REGRESSION ... 45

TABLE 7:CONSTRUCT ANALYSIS FOR INTENTION AS A DEPENDENT VARIABLE ... 46

TABLE 8:SUMMARY OF HYPOTHESES TESTING ... 49

1

1. Introduction

_____________________________________________________________________________________ In this section, the reader is introduced to the topic of palm oil, and the concepts of social marketing and advertising appeals. Thereafter, the problem will be discussed further as well as defining the purpose of this study.

______________________________________________________________________

The environment is constantly changing. But due to human activity, the climate is now changing more drastically than ever before, and the temperatures and sea levels are rising at an alarming rate (IPCC, 2013). We as humans are now facing plenty of issues concerning the climate and there are many obstacles to overcome until we can reach environmental sustainability. Many organisations are increasingly trying to shed light on these issues and to push for more pro-environmental behaviour not only for individuals but for the society. Pro-environmental behaviour is defined by Kollmuss and Agyeman (2002, p. 240) as “behavior that consciously seeks to minimize the negative impact of

one’s actions on the natural and built world”. This is often done through social marketing

campaigns promoting sustainable behaviour (McKenzie-Mohr, Lee, Kotler & Schultz, 2011). Within these campaigns, different environmental issues are portrayed in such a manner that aims to close the gap between individuals’ values and actions. Although the message may be the same, it can be delivered differently through different marketing appeals (Fill & Turnbull, 2016). When it comes to environmental issues, palm oil is a constantly recurring topic due to its contribution to greenhouse gas emissions and deforestation.

Palm oil is one of the most used vegetable oils in the world (Barthel et al., 2018) and an increasing number of products in our everyday life such as food products and cosmetics contain palm oil. As palm oil has a higher yield per hectare than, for example, soy, rapeseed, and sunflower oil, it is more advantageous for producers to grow (Barthel et al., 2018). A large part of the worlds palm oil production is based in South East Asia, specifically in Indonesia and Malaysia, both of which are known to have rainforests with rich animal life. However, when the rainforest in these areas are devastated to leave room for production of crops like palm oil, it has a vast effect on biodiversity and the

2

surrounding environment (Aguiar, Martinez & Caleman, 2018; Disdier, Marette & Millet, 2013) leading to the extinction of animal species such as orangutans (Disdier et al., 2013). While the primary cause of deforestation in these areas is the conversion of rainforest to the production of palm oil the deforestation is also one of the highest contributors to the countries’ greenhouse gas emissions (Abood et al., 2015; Warr & Yusuf, 2011). The effects that the current palm oil production has on the environment are unarguably destructive. To drive the change towards more sustainable options something must be done. Studies show that consumers are concerned by the palm oil issue (Disdier et al., 2013) and have negative perceptions of the use of palm oil but this concern does not extend to the products they consume (Aguiar et al., 2018). In other words, the concern does not impact their behaviour when it comes to verifying if the products contain palm oil. To help consumers make conscious choices when it comes to products containing palm oil, even when the decision time is short, such as in fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG), social marketing efforts can be increased.

In this paper, social marketing and marketing appeals will be studied to create two advertisements. These advertisements are used in this research to determine the elements affecting the viewers’ intention to change when it comes to avoiding palm oil consumption. First, the background of social marketing and appeals is established after which the problem is discussed in more detail. Second, the theoretical background will introduce the concept of theory of planned behaviour as well as a more comprehensive view of marketing appeals, both of which are used in the creation of our advertisements as well as analysing the results. Third, the method of our study is explained regarding subjects, such as literature review, quantitative survey and the making of the advertisements. Fourth, the results from our primary data are presented and analysed. Lastly, we discuss the limitations of our study and directions for future research.

1.1 Background

The approach of social marketing and its origins were introduced in the early 1950s after a sociologist, Wiebe (1951-1952) started advocating the use of marketing in a way that would benefit society through highlighting social issues. In his article, he noted that non-profit campaigns mimicking corporate marketing campaigns strategies have led to great success. Thus, Wiebe (1951-1952) emphasised the role of social marketing in shaping

3

and improving the quality of life and of communities. The term resurfaced a decade later where it was not yet formalised, nevertheless, scholarly discussions opened the door for this marketing field to be born.

The concept was mainly questioned of its authenticity due to marketers believing that concepts such as social and environmental issues could not be marketed, and that this idea was believed to diminish the reputation of general concept of marketing (Fox & Kotler, 1980). After researchers explained the niche of social marketing, which is concerned with behavioural change, the concept finally gained its recognition, and that it can indeed be used in contributing to resolving social issues. The limitations of the field were also identified and discussed, which helped to contribute to understand the role of social marketing and knowing when it should be utilised. Nowadays, social marketing is an effective form of promoting and encouraging better behaviour for the sake of society and the environment. The concept is recognised in many parts of the world and even practiced by private sectors and non-profit organisations. Nonetheless, debates are ongoing regarding whether the field should focus on influencing citizens or policymakers, and other discussions consist of how the use of marketing strategies should be applied for it to be efficient (Andreasen, 2006; French & Lefebvre, 2012).

1.1.1 Defining Social Marketing

The first definition of social marketing was offered by experts Kotler and Zaltman (1971, p. 5) where they stated that “Social Marketing is the design, implementation and control

of programs calculated to influence the acceptability of social ideas and involving considerations of product planning, pricing, communication, distribution, and marketing research.” This was during the era when the concept was still somewhat controversial

and rejected by many due to the cause of confusion. Years later, Rangun and Karim (1991) pointed out that individuals can confuse the terminology with the concept of societal marketing. Societal marketing differs from social marketing, the researchers argue that social marketing consisting of influencing attitudes, beliefs, and behaviours of people as well as organisations for the benefit of society. Additionally, the authors added that social change is the primary purpose of the campaigns. On the contrary, societal marketing focuses on regulatory issues and does not include the purpose of influencing target consumer in any way (Rangun & Karim, 1991). Societal marketing can simply be

4

defined as a marketing concept where a private sector company makes marketing decisions with the consideration of consumers’ needs, the company’s conditions and with a focus of society’s long-term interests. This can be linked to corporate social responsibility and sustainable development, but their primary focus is not social change (Rangun & Karim, 1991). Thus, this concept is distinguishable from social marketing. Another problem that the authors pointed out was the confusion of whether it is only limited and applied by public and non-profit marketers, however, private sector firms can engage in social marketing in a correct way. This indicates that social change will not be categorised as a secondary purpose of campaigns from private sectors standpoint.

Kotler and Roberto (1989) were also among the first to present a definition of social marketing as a process of programme planning which promotes a voluntary behaviour of a specific target audience. This is done by offering them benefits they want and reduce barriers that are of concern to the audience and using persuasion for the motivation to participate in programme activity. This is also suitable to the definition of the concept according to one of Andreasen’s (1994) objectives of the definition of social marketing, where marketers should focus on the influential aspect. The field expert also proposed his own definition where he states that “Social marketing is the adaptation of commercial

marketing technologies to programs designed to influence the voluntary behavior of target audiences to improve their personal welfare and that of the society of which they are a part” (Andreasen 1994, p. 110). In another article, Andreasen also emphasises the

importance of utilising technology or strategies from the private sector marketing while having “behaviour influence” as a bottom-line (Andreasen, 2002). Recent researchers have offered a similar definition to expert Andreasen’s (1994), for instance, a study by Wymer (2011) suggested that the concept is shaped to correct social problems. Other researchers, Inoue and Kent (2014), explained the goal of corporate social marketing programmes or campaigns, which is encouraging people to perform more prosocial behaviours.

Social marketing can simply be described as a planned approach to social innovation, where marketing principles are applied in order to develop activities with the goal of changing or maintaining consumers’ behaviours for benefits on both individual and societal level (Lefebvre, 2012). This definition complies with previous definitions of field

5

experts, and it is the definition used in this study. Social marketing can be used in different areas (Kotler & Lee, 2019), the most common aspects would be:

1. Public health & safety, where campaigns are focused on creating awareness

and educating about such issues as smoking, with the aim of changing consumers’ behaviour to change or reduce their habits. It also includes campaigns about safe driving.

2. Democratic citizenship & social activism, which consists of programmes or

campaigns about gender inequality, racial issues, thus it also includes anti-bullying campaigns.

3. Environment and sustainability, where the campaigns or programmes are

addressing different environmental issues with the aim of influencing individuals’ behaviour through e.g. reducing production and or consumptions of harmful goods. This is the aspect chosen for this paper with the main topic being the palm oil issue.

1.1.2 Differences and Similarities between Commercial Marketing and Social Marketing

Social marketing is a method where the main objective is to inspire behavioural change and create awareness of social and environmental issues for societal and individual gain. Commercial marketing on the other hand, is about selling services and products for mostly financial gain. The priority of commercial marketing is finding the perfect target audience to generate profit. In social marketing, segments are selected based on the ability to reach the audience and how ready they are for change and primarily prevalence of social dilemma (Kotler & Lee, 2019). Andreasen (1994) has also addressed the differences between the two practices, where he mentions that private sector marketing is mainly created in a way to achieve sales objectives. Marketers in this sector engage in activities that are supposedly designed to change values, beliefs, and attitudes, which is similar to social marketing, however, in difference to social marketing, private sector marketers expect changes such as increased sales. Additionally, Andreasen (1994) raises awareness on how commercial marketers can potentially design campaigns that prevent change through e.g. switching to newly introduced brands. This is one factor that the expert stresses that borrowing commercial technology does not mean using the same bottom lines (Andreasen, 2002).

6

1.1.3 Appeals in Advertising

Like commercial marketing, social marketing uses appeals to generate desired responses to the message. Message appeals can be categorised into information-based and emotions- and feelings-based appeals (Fill & Turnbull, 2016). Information-based appeals include factual, slice of life, demonstration, and comparative appeals, whereas emotional appeals comprise fear, humour, and shock (Fill & Turnbull, 2016). In commercial marketing, the appeals are used mostly to generate purchase intentions and brand loyalty. However, social marketing’s aim is to stimulate voluntary compliance with the message, meaning adopting a desired behaviour, such as waste reduction or minimising carbon footprint (Brennan & Binney, 2010). Social marketing tends to rely on emotion-based appeals and even though there are positive emotional appeals that could be utilised, negative emotional appeals are most used by social marketers. According to Brennan and Binney (2010), the three most common appeals in social marketing are fear, guilt and shame which are used to create an emotional imbalance in the recipient of the message. To solve this imbalance, social marketers expect recipients to engage in the desired behaviour promoted by the message.

1.2 Problem Statement

As awareness about climate change is increasing, the topic is more and more becoming a part of daily conversations. However, it seems that the change for a more sustainable society is not coming fast enough and that current efforts to bring about desired behavioural change are failing in their effectiveness. Social marketing can be an effective tool to encourage and facilitate this behavioural change and the role of social marketing is increasing as the campaigns are becoming increasingly visible. As discussed previously, in the field of environmental sustainability, social marketers often opt for the negative emotional appeals in their messages. However, the use of negative appeals, particularly fear, has been criticised by several scholars as not only being ineffective but also unethical (Brennan & Binney, 2010; Hastings et al., 2004). Additionally, Brennan and Binney (2010) found in their study of negative appeals that participants were likely to reject the message if fear was used as an appeal.

While there is a clear research gap regarding positive emotional appeals in the field of social marketing, a study by Henley, Donovan and Moorhead (1998) showed promising

7

results and concluded that the positive appeal of a message in a parenting campaign was well-received and motivated action. What is currently unknown, is whether using positive appeals could produce similar results specifically in environmental social marketing in terms of voluntary compliance. Since it has been discovered that messages using positive appeals do not provoke feelings of guilt and shame in the recipient, but rather encourage actions in a hopeful manner, it is interesting to investigate if these findings could be applied to the environmental social marketing as well.

For the reasons discussed previously, it is important to reconsider the use of negative emotional appeals in social marketing, which are especially prominent in environmental sustainability marketing. Finding more efficient ways to inspire voluntary compliance would increase the effectiveness of sustainability efforts and this is where social marketing could help inspire change both at the individual level and at the level of policymakers. Social marketing in environmental sustainability is increasing in its importance as consumers are aware of environmental issues but might lack the adequate tools and information to act. One reason behind this is that policymakers are actively talking about environmental challenges but often fail to address how they could be resolved. Therefore, social marketing is responsible for educating consumers about the concrete actions they can take regarding environmental sustainability. This accentuates the importance of social marketing and therefore, it is crucial to know how it can be used most effectively.

1.2.1 Purpose

The thesis aims to gain a comprehensive understanding of how the appeals used in social marketing in the field of environmental sustainability affect the motivational factors that influence the intention to change behaviour. Also, we will further broaden the use of the theory of planned behaviour by adding the element of the marketing appeal to the existing model. The purpose of this study is to examine which of the elements in the theory of planned behaviour, with the addition of the different social marketing appeal, have a significant effect on the intention to avoid palm oil consumption. Additionally, we aim to contribute to the existing research gap by studying the effects of positive appeals.

8

2. Theoretical Background

_____________________________________________________________________________________ The purpose of this chapter is to provide the theoretical background on the relevant concepts for this research. The concept of value-action gap is evaluated to understand why awareness does not always lead to action. Furthermore, previous research on the theory of planned behaviour is assessed to form a comprehensive understanding of the concept, as well as examining the status of current research on marketing appeals. Lastly, these concepts are utilised to create the adapted frameworks for this research and the formulation of the hypotheses.

______________________________________________________________________

2.1 Value-Action Gap

Within research on pro-environmental behaviour, the fact that people are aware of and concerned by environmental issues (Nisbet & Myers, 2007) but fail in their commitment to change their behaviour and act on their values, is well known. This inconsistency between values and behaviour is often referred to as the value-action gap (Babutsidze & Chai, 2018; Chai, Bradley, Lo, & Reser, 2015; Gifford, 2011; Flynn, Bellaby, & Ricci, 2009; Markowitz & Shariff, 2012). Within the value-action gap on pro-environmental behaviour, the values are commonly referred to as the “stated concern about climate

change” (Babutsidze & Chai, 2018, p. 290). Simply put, the value-action gap can be

identified as the disconnection between what people say and what they do. The only way this gap would be diminished is for individuals to act on their concerns.

Chai and colleagues (2015) identify the value-action gap as a major barrier to sustainable consumption. Further, the authors argue that the gap can be diminished through the individual’s attitudes towards the issue. These attitudes would be formed based on the discretionary time an individual possesses (Chai et al., 2015). Likewise, other underlying factors could hinder pro-environmental behaviour. For example, Flynn et al. (2009) argue that, in the context of energy-conscious behaviour, switching costs and that people feel that their actions are insignificant could be the cause of the value-action gap.

9

However, it is suggested that there is not only a gap between values and action. In Barr’s (2006) investigation on the value-action gap related to waste management in the home, it was found that there is a conflict between the intention of pro-environmental behaviour and the actual action. On the other hand, the author also found that the intention was the highest predictor of the examined behaviour as opposed to the values on their own. Therefore, Barr (2006) argues that the relationship between intention and action as described by Fishbein and Ajzen (1975) in the theory of reasoned action can be used to conceptualise the value-action gap. According to Barr’s (2006) findings, behaviour can to a high degree be predicted by the intention to act, thus it is interesting to examine the motivational factors that could predict the intention.

2.2 Theory of Planned Behaviour

In 1975, Fishbein and Ajzen identified two major factors that determine an individual’s intention to adopt a behaviour asthe assumptions of the outcomes of the behaviour and how the person perceives that people important to him will recognise the behaviour. This was then known as the theory of reasoned action. The theory of reasoned action was further developed into the theory of planned behaviour in 1988 and was then extended to include the effect of an individual’s perception of one’s ability to perform the behaviour (Ajzen, 1988). In literature on social marketing practices, the theory of planned behaviour is often used to understand the influences that generate behavioural change in individuals (Almestahiri, Rundle-Thiele, Parkinson, & Arli, 2017; Lefebvre, 2001).

The theory of planned behaviour aims to grasp the complexity of human social behaviour by gaining an understanding of what enables or hinders an individual to act on their values. According to Ajzen (1991), a person’s behaviour can best be predicted by their intention to act. The theory of planned behaviour model hypothesises three theoretically independent determinants that form the intention to behaviour which in turn affect the actual behaviour as seen in Figure 1 (Ajzen, 1991). These determinants are the attitudes towards the behaviour, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control.

10

2.2.1 Attitudes

The first element of the framework is attitudes. Consumers’ attitudes occupy central roles in research and theories linked with consumer behaviour. Although there are various formal definitions of the concept, majority of theorists agree that it can be best described as the tendency to respond to an object, or in social marketing, a behaviour, with some degree of favourableness or unfavourableness (Ajzen & Cote, 2011). Normally, social attitudes are not innate, in this manner, there is a great number of factors such as cultural, political, economic, and more that shape our evaluative dispositions and thus beliefs. Attitudes are prevalently determined by some beliefs. One important term is “behavioural beliefs”, which is the perception of positive or negative outcomes of performing a behaviour, and the subjective values and evaluations of those outcomes (Ajzen, 2016). These behavioural beliefs, which are accessible in memory, are what can lead to the formation of positive or negative attitudes towards a behaviour. Nevertheless, researchers also argue that it can be assumed that these beliefs do not always significantly influence a consumer’s attitude (Ajzen, 2016).

Attitude models, including the theory of planned behaviour, usually do not make any assumptions regarding rationality, on the contrary, models rely on attitudes being formed from beliefs about the behaviour. The more positive the beliefs are, the more strongly

Figure 1:Theory of planned behaviour. Adopted from Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned

11

they are held and thus the more favourable the attitude would be (Ajzen & Cote, 2011). Additionally, the source of these beliefs is immaterial, thus it is not of importance whether these beliefs are biased or unbiased, they still represent subjectively held information upon which attitudes are based on. In other words, consumers may hold certain beliefs about many objects or behaviours, it does not necessarily derive from logical processes of reasoning, they can be biased by emotions (Ajzen & Cote, 2011). In general, it is important to understand that the theory of planned behaviour’s avoidance of assuming rationality indicates that attitude towards behaviour can be poorly informed, reflect unconscious biases, self-serving motives, and other irrational processes. Moreover, people should not be assumed to go through careful examinations of beliefs whilst performing a behaviour.

A general fact for this theoretical framework is that in most cases when outcomes linked with a certain behavioural change are valued as positive, it is autonomous and simultaneous that an attitude is acquired toward the behaviour (Ajzen, 2016). Thus, positive attitudes toward a behaviour can produce desirable results, meaning a higher intention to perform a preferable behaviour, and unfavourable behaviour can be the cause of non-desirable outcomes. In many cases, a consumer’s attitude was the strongest predictor of intentions when applied to consumption decisions (Ajzen, 2016).

Previous studies about environmental consumption have discussed consumers’ attitudes toward other environmental issues. One study introduces the term environmental attitude, which is an individual’s judgement toward protecting the environment and promoting it (Cherian & Jacob, 2012). The study also mentions that previous empirical research has found results conflicting regarding the relationship between attitude towards the environment and subsequent behaviour. Cognitive and affective functions are impacted by the attitude a consumer shows, hence, it impacts their overall perception of consumption behaviour. This led to the conclusion that there is also a need to change consumers’ attitudes towards consumption behaviour. This gives the elucidation that environmental marketing campaigns can be useful. Researchers Cherian and Jacob (2012) have applied the theory of planned behaviour to study consumers attitudes regarding green consumption and found that there is not much conclusive evidence. However, the authors still proposed that there is a link between a consumer’s attitude and behaviour when it comes to choosing to purchase environmentally friendly products. The

12

researchers also pointed out the need for marketers to raise awareness when it comes to environmental issues since they believed that not many consumers had the environmental knowledge required to shift their attitudes and behaviour to more desirable ones.

Another research focused on the gap between attitude and behaviour for sustainable consumption, with the application of the theory of planned behaviour framework. Vermeir and Verbeke (2006) were aware that sustainable consumption is based on a decision-making process, and that consumers’ everyday consumption is driven by habit, convenience, or health concerns and even value for money. Furthermore, these consumers would be most likely to resist change. However, the researchers believe that the reason could be the attitude-behaviour gap as attitude alone can be a poor predictor of intention. While these experts were investigating which factors influence the intention of choosing sustainable consumption, they commenced with the premise that having a positive attitude toward purchasing sustainable products does not necessarily mean it would be followed by positive intentions. Nevertheless, a positive attitude is an efficient starting point to stimulate sustainable consumption.

2.2.2 Subjective Norm

The second element in the theory of planned behaviour predicting intentions is subjective norm, which refers to the socially expected mode of conduct (Ajzen, 1991). Subjective norms stem from the belief that a significant individual or a group will approve and support certain behaviours, and disapprove of other behaviours (Ham, Jeger & Ivković, 2015; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1977). Along with attitudes and perceived behavioural control, subjective norms motivate individuals to change behaviour by introducing social pressure from these “referent individuals or groups” (Ajzen, 1991, p.195). The element determining the power of subjective norms is the individual’s motivation to comply with the referent individuals’ or groups’ views, which is the driver of the behavioural change since it is assumed that individuals are likely to behave in a way which is regarded as desirable by significant others (Ham et al., 2015).

Subjective norm consists of two components which can be individually measured. First, the injunctive component is based on the assessment of “whether one believes their social

13

evaluates “whether one’s social network performs a behaviour” (Rhodes & Courneya, 2003, p.130). In their study, Rhodes and Courneya (2003) evaluated the effect of both injunctive and descriptive norms and found them to be common factors in the prediction of intention. Therefore, the authors concluded that injunctive and descriptive norms have a significant effect on the perceived social pressure and together can represent subjective norm (Rhodes & Courneya 2003). Similarly, Ramayah, Lee and Lim (2012) discovered subjective norm to be the strongest predictor of recycling behaviour.

2.2.3 Perceived Behavioural Control

The third element of the theory of planned behaviour is perceived behavioural control which refers to an individual’s perception of how easy or difficult it would be to perform a behaviour (Ajzen, 1991). This is assumed to reflect past experience as well as anticipated impediments and obstacles. The perceived behavioural control element was not a part of the original theory of reasoned action but was later added when the theory of planned behaviour was developed as there may be situations where individuals do not have complete volitional control over the behaviour (Ajzen, 2002).

The construct of perceived behavioural control, however, is not unique to the theory of planned behaviour but is comparable to other concepts. The most similar one to the perceived behavioural control is the concept of self-efficacy (Ajzen, 1991). According to Bandura (1998, p. 624) self-efficacy is “the beliefs in one’s capabilities to organize and

execute the courses of action required to produce given levels of attainments”. This

definition is similar to that of perceived behavioural control which is presented as

“people’s expectations regarding the degree to which they are capable of performing a given behaviour, the extent to which they have the requisite resources and believe they can overcome whatever obstacles they may encounter” (Ajzen, 2002, p. 676-677).

Ajzen (2002) points out that the perceived behavioural control consists of both measures of self-efficacy, such as the ease or difficulty of performing a behaviour, and measures of controllability, which is the individual’s belief about the extent to which it is up to him or her to perform the behaviour. Further, the author argues that perceived behavioural control reflects both internal and external factors of control.

14

According to the theory of planned behaviour, a high level of perceived behavioural control will make an individual’s intention to perform the behaviour stronger as well as raising the effort and perseverance (Ajzen, 2002). Naturally, if an individual feels that he would succeed in performing the behavioural adoption it would be more likely to happen. In this way, the perceived behavioural control indirectly influences the actual behaviour.

2.2.4 Intention

A consumer’s intention can simply be defined as the commitment, plan or decision of an individual to carry out an action or achieve a goal (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993). Normally, intentions can lead to actions directly, but they can also lead to behaviour change after a gap in time. The element is assumed to be determined by behavioural beliefs, which in technicality refer to the attitude element of the framework of theory of planned behaviour. Another influence that is known to determine an intention are normative beliefs, which refer to a person’s perceived expectations as well as behaviours of important groups of people. This would be the element of subjective norms in the theoretical framework (Ajzen, 2016). Moreover, control beliefs influence an intention as well. These are what people believe are factors that could interfere or facilitate a behavioural performance, which refers to the element of perceived behavioural control. Lastly, a positive measure of the three elements would mean that a person is more likely to have a higher intention to perform a certain behaviour.

Expert Ajzen (1991) explains that “the relative importance of attitude, subjective norm,

and perceived behavioural control in the prediction of intention is expected to vary across behaviours and situations” (Ajzen, 1991, p. 188). Thus, there might be instances where

only one or two of the three determinants have a significant impact on intentions and in others, all three make independent contributions. Ajzen (1991) also points out that the only way the intention to behaviour can become an actual behaviour is if the question is under volitional control. This means that the person should be able to decide to perform or not to perform the behaviour. Furthermore, an actual behavioural control, i.e. capability of performing the behaviour in question, can moderate the effect of intention on behaviour (Ajzen, 2016).

15 2.3 Appeals

Appeals are used by advertisers to trigger desired emotions in the receiver of the message. In commercial marketing, the goal is that the emotional response of an individual leads to a higher purchase intention (Fill & Turnbull, 2016), whereas in social marketing the aim is to get the recipient to engage in the advertised behaviour. Previous research on appeals in social marketing has vastly focused on the use of negative appeals since they are the most utilised by social marketers. Henley et al. (1998, p. 48) define positive and negative appeals as follows: “In the literature, positive appeals are generally considered

to be appeals eliciting or promising positive emotions as a result of using a product or adopting a recommended behaviour. Conversely, negative appeals are considered to be those eliciting or promising negative emotions as a result of not using the product or adopting the behaviour.” Furthermore, based on Rossiter and Percy’s (1987) model

connecting emotions to motivations in advertising, it can be said that negative appeals use threats based on the motivation of problem avoidance whereas positive appeals apply promises based on achieving mastery (Henley et al., 1998).

The use of negative appeals in social marketing is based on the assumption that they create an emotional imbalance in the receiver of the message which can be amended by engaging in the desired behaviour (Brennan & Binney, 2010). Emotional imbalance creates discomfort which is expected to act as a motivator for the recipient to act (Brennan & Binney, 2010). One of the most used negative appeals in social marketing is fear. Fear appeals can be further categorised into physical fear appeals, which are threats implying harm to the body, and social fear appeals which relate to threats regarding social acceptance as well as harm to the recipient’s family (Brennan & Binney, 2010; Brooker, 1981). Examples from Brooker’s (1981) study are “Protect yourself from the dangers of flu” as a physical fear appeal, and “Protect your family from the flu” as a social fear appeal. Another popular negative appeal in social marketing is guilt, which is aimed to inspire the recipients to consider their moral obligations towards other people and the environment by arousing sympathy (Brennan & Binney, 2010). In environmental social marketing, guilt appeal is used for example when showing pictures of sea turtles with plastic straws in their nostrils, and if the recipients use plastic straws it is expected that they will sympathise with the turtles and reconsider their use of plastic straws. Lastly, using shame as an appeal is also common practise in social marketing. In an extensive

16

study of fear, guilt and shame appeals conducted by Brennan and Binney (2010, p. 144), participants defined shame “as an emotion that individuals experience when other people

who are significant to them become aware of their socially unacceptable behaviour.”

Therefore, shame appeals might not be effective in inspiring behavioural change. In the case of individuals living in a homogenous environment where everyone acts in the same manner, there is no way for them to feel shame about their behaviour.

Even though these negative appeals are the most used in social marketing, there are plenty of studies showing that they might be ineffective as well as unethical. Fear appeals are often perceived to promote acceptable behaviour by scaring individuals about the potential risks and consequences regarding the unacceptable behaviour (Brennan & Binney, 2010), which in turn can lead to anxiety (Hastings et al., 2004). It has also been found that negative appeals tend to lead to defensive self-protection and passivity rather than voluntary compliance (Brennan & Binney, 2010; Henley et al., 1998). Moreover, Schoenbachler and Whittler (1996) found that fear appeal messages, especially ones including physical threats, are only effective in the short-term, but their persuasive effect diminishes over time. Additionally, the overuse of negative appeals is problematic. Brennan and Binney (2010) discovered that as participants were overly exposed to negative appeals, they would “switch off” from the message. Similarly, according to Hastings et al. (2004), repetition of negative appeal messages can lead to habituation, feelings of annoyance and ignoring the message.

However, indications of the effectiveness of negative appeals have been found. Ray and Wilkie (1970) dedicated an entire study to show that the fear appeal is not used to its full capabilities in advertising. They argue that fear can have some facilitating effects in relation to learning and acting on the recommendations of the message. Particularly messages with fear appeals have also been found to have the ability to generate more accurate recalls among recipients, especially if these messages include a threat of personal consequences or fear for others (Brennan & Binney, 2010). While this evidence seems to encourage the use of negative appeals, it is important to note that most studies about fear appeals have been short-term studies in laboratory settings and due to lack of resemblance with the real world, it is unlikely that these findings can directly be applied in a natural setting (Hastings et al., 2004). Therefore, it could be beneficial to consider the potential

17

of positive appeals which are currently underutilised in social marketing (Henley et al., 1998).

Considering the inadequacy of research on the effectiveness of positive appeals in social marketing, it is necessary to study how they are used in commercial marketing and then apply the findings to social marketing. This idea is based on Wiebe’s (1951-1952) research in which he concluded that the most effective social marketing campaigns were the ones that had more similarities to commercial marketing. Commercial advertisers tend to prefer positive appeals in their messages (Wheatley & Oshikawa, 1970) due to their proven effectiveness in the consumer market. Advertisements that can generate positive feelings in the recipient are associated with creating higher advertisement and brand recognition (Geuens & De Pelsmacker, 1998). One of the most used positive appeals is humour, which is known to draw attention to the advertisement and generate interest (Fill, 2006). Humour can be applied by using puns, jokes or one-liners (Brooker, 1981), which could also be employed by social marketers. Another positive appeal, which can easily be applied by social marketers, is animation. Animation combined with other positive message appeals results in the message being visually appealing and the advertisements are often perceived to be “cute” (Fill & Turnbull, 2016). Additionally, advertisements utilising animation are effective in gaining consumers attention and breaking through the commercial clutter (Fill & Turnbull, 2016; Bush, Hair & Bush, 1983). The main advantage of positive appeals is that they can put the receiver in a good mood (Fill, 2006). In persuasive communications, positive mood is associated with increasing the message acceptance and leads to a more positive evaluation of the arguments in the message (Batra & Stayman, 1990). This is fundamental for social marketing, where the aim is to convince the recipients to accept the message and act accordingly.

The limited amount of research done regarding positive appeals in social marketing has shown that appeals generating positive emotions, could be equally as effective as negative appeals (Hastings et al., 2004). Brooker (1981) conducted a research comparing humour and fear appeals using advertisements for a vaccine and a toothbrush as examples. He found that mild forms of humour were more persuasive than mild forms of fear. Similarly, Brennan and Binney (2010) concluded in their study that humour motivated action, in comparison to the negative appeals, which led to participants rejecting the messages. Furthermore, Henley et al. (1998) discovered that positive appeals have the power to

18

facilitate substantial behavioural and attitudinal change. These findings suggest that social marketers could benefit from the use of positive appeals such as positive reinforcement appeals toward the favourable behaviour, self-approval motivations and intellectual needs of the recipient (Hastings et al., 2004; Henley et al., 1998).

2.4 Adapted Theoretical Framework

One study that examined plastic consumption among university students argued that environmental knowledge influences attitudes and therefore added the element of environmental knowledge to the theory of planned behaviour (Appendix 1) (Hasan, Harun & Hock, 2015). In a similar manner, it can be argued for this study that the marketing appeal can influence the attitudes of consumers as well as their perceived behavioural control. Therefore, the element of appeal was added to the theory of planned behaviour (as seen in Figures 2 and 3) to examine the relationship between the appeal, attitude, and perceived behavioural control. Furthermore, to examine the intention to change to a certain behaviour, the effects of all the elements in the model will be analysed. Since this was a short-term study, complete behavioural change could not be examined, thus the element was removed from the adapted models.

19

2.4.1 Problem Formulation

Previous research in different settings identifies the connection between positive appeal, favourable attitudes, and intention to behavioural change. Therefore, in the context of avoiding products containing palm oil hypothesis one is defined as:

H1: The social marketing advertisement using a positive appeal has a stronger effect on attitude towards the advertised behaviour compared to the negative appeal.

As mentioned in the theoretical background, Ajzen (2016) suggested that a consumer’s attitude was the strongest predictor of intentions when applied to consumption decisions. Hence, the second hypothesis is as follows:

H2: Attitude is the strongest predictor of intention to behavioural change for both appeals.

Given that subjective norms can be defined by the answer to the question “do other people important to me want me to do that?” the appeal’s effect is not apparent. Thus, hypothesis three is as follows:

H3: Subjective norm has a positive and direct effect on the intention regardless of the

appeal.

Previous research has applied the theory of planned behaviour on reducing plastic consumption (Hasan et al., 2015). This research identified perceived behavioural control

20

to be the strongest predictor of intentions and due to this research being in the same field, hypothesis four is as follows:

H4: The perceived behavioural control is the strongest predictor of intention to

21

3. Methodology and Method

_____________________________________________________________________________________ In this chapter, the chosen research approach and the method will be discussed. Two main methods were considered in this paper, the first being a qualitative literature review and the second a quantitative survey. Additionally, a pilot survey was conducted. All aspects regarding the execution, design and structure of this study, and data collection and analysis are considered below. Lastly, ethical considerations regarding this research are presented.

______________________________________________________________________

3.1 Methodology

This research was constructed under the positivist paradigm. Positivism is concerned with measuring a social phenomenon with quantitative methods (Collis & Hussey, 2014). In our case attitudes toward palm oil and willingness to avoid the consumption of palm oil were measured with a quantitative survey. Additionally, we used a larger sample size compared to studies using interpretivism as a paradigm and the output of our survey is precise, objective, and quantitative data, both of which are features of positivism. Furthermore, our study is concerned with hypothesis testing, which again displays the application of positivism. We also followed the guidelines of deductive research, which is often the case in positivist studies (Collis & Hussey, 2014). In deductive studies, the theory is developed before testing it by empirical observation (Collis & Hussey, 2014). The basis of our study was the hypothetical frameworks created based on previous research and literature, which we then tested by collecting data from our sample.

3.2 Literature Review

For the secondary data, a literature review was conducted where academic books, as well as ABS-listed and peer-reviewed journal articles, were systematically reviewed. The databases used were the Jönköping University library search engine Primo, EBSCOhost and Google Scholar. The key elements were the concept of social marketing and the marketing appeals used in various campaigns or programmes. To gain a general understanding of the purpose of social marketing and certain factors that could affect consumers’ actions, intention to behavioural change was discussed in the theoretical

22

chapter. The specific area that is examined in this paper is the environmental and sustainability aspect of social marketing, thus some of the keywords used for research were the following: social marketing, theory of planned behaviour, environment and sustainable behaviour, consumer attitudes, social marketing appeals and consumer behaviour, positive and negative appeals in social marketing and value-action gap. All concepts were connected to create a hypothetical framework.

3.3 Quantitative Survey

The objective to why this study was designed as quantitative was to generate knowledge and create an understanding about a social phenomenon, in this case, consumer intention through the theory of planned behaviour. Quantitative studies are popularly used by scientists to study occurrences that affect individuals in a group of people (Allen, 2017). It is used to study behaviours and attitudes to possibly make a generalisation of a larger population, which is why it was more fitting for our study. Additionally, the use of a survey seemed logical since all participants’ answers would be anonymous, encouraging them to answer truthfully without the interference of social pressure.

The primary data was collected through an online survey. In the survey, the respondents were asked about motivational factors that would lead to a possible intention to behavioural change connected to the avoidance of palm oil. Some of the participants saw an advertisement with negative appeals and others with positive appeals. The advertisements were meant to inspire people to avoid consuming products that contain palm oil due to the environmental issues linked to its production. The aim was to examine if one of the advertisements results in a higher intention to change behaviour. After the advertisement, respondents were asked questions regarding their attitudes, subjective norm, and perceived behaviour control. Respondents were also asked about their past behaviour concerning palm oil and their possible intention to behaviour change. The advertisements were created by us to be able to control the appeals. Before the survey was sent to our sample, a pilot survey was conducted to ensure that the advertisements are perceived as intended by our participants.

23

3.3.1 Video Advertisements

Based on the theoretical background on how positive and negative marketing appeals are perceived by and affect consumers, two video advertisements were made (Appendix 2 and 3). One was based on mainly positive appeals and the other was based on negative appeals. Since we are marketing majors, we decided to edit the advertisements using material found on YouTube (Appendix 4). As the videos were intended for educational purpose, the copyright falls under fair use (WIPO, n.d.). Video format was chosen due to the ability to include a storyline which is difficult to bring about in, for example, a print ad. Additionally, by making a video, music could also be included to set the mood. The ambition was to have the content of the two advertisements similar so that the factors that would determine attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control would not differ too much.

In the videos, the viewers are introduced to an orangutan named Oscar. This is to create a relationship between the viewer and the advertisement and to further enhance the emotional effect of the advertisements by making Oscar a real character. In the advertisement using negative appeals, Oscar says that his home has been destroyed because of the viewer’s everyday products. The message is accompanied by pictures of devastated rainforest and dismal music. This is meant to evoke shame and guilt in the viewer. Additionally, the advertisement aimed to portray the action of avoiding palm oil consumption to be difficult to affect the perceived behavioural control. Contrarily, in the advertisement that utilised positive appeals, Oscar says that with your help the rainforest can be preserved. In this video, pictures of a healthy rainforest were used together with happy music. The aim here was to give the viewer a sense of hope. However, there was a glimpse of negative appeal in this video. This was for the sake of creating hope for a better future even though it looks bad right now.

3.3.2 Pilot Survey

Following the method proposed by Fishbein and Ajzen (2015), a pilot survey was made with the help of esMaker, a web survey tool provided by Jönköping University. This survey was conducted to obtain readily accessible behavioural outcomes, normative referents, and control factors. In this survey, the video advertisements were also tested to

24

explore how the positive and negative appeals affected the respondents' feelings towards the message, and thus if the advertisements were perceived as intended. Convenience sampling was used for the pilot survey with a sample size of ten per cent of the projected sample, as recommended by Connelly (2008), thus the sample size consisted of ten people. For the pilot sample to represent the real sample, Swedish university students and newly graduated Jönköping University students were chosen. None of the individuals from the chosen sample knew beforehand what the research was about. The sample consisted of eight women and two men between the ages of 18-29.

To elicit behavioural outcomes from performing the behaviour of avoiding the consumption of products containing palm oil, respondents were asked about the advantages and disadvantages of performing the behaviour. Similarly, to determine the normative referents, the respondents were asked to list the individuals and groups who would approve or disapprove of the behaviour as well as the people who were most and least likely to engage in the very same behaviour. The control factors were obtained from asking the respondents what factors would either enable or prevent their performance of the behaviour. Lastly, the respondents were shown both video advertisements separately, each followed by a question about how they felt after seeing the advertisements. All questions in the pilot survey were open-ended so that the respondents would not be restricted by pre-identified options. The pilot survey design can be seen in Appendix 5.

3.3.2.1 Pilot Survey Results

A content analysis of the responses to the pilot survey was utilised to identify patterns in the answers. The objective of the analysis was to list the modal salient outcomes, referents and control factors which then could be used for the questionnaire design of the final survey. We all did the initial coding individually after which we compared the identified topics. There were no disagreements in this process. The topics mentioned can be seen in Appendix 6. The topics mentioned by at least 30% of the respondents were used for the survey. The recognised salient outcomes were identified as conserving rainforest, preserving biodiversity, saving the environment, giving up on products one likes, and having to pay higher prices. Referents were identified as vegans, activists, and environmentally conscious people. Lastly, the control factors were recognised as available information, price, and availability of alternative products.

25

The responses to the video advertisements were also explored using content analysis. Here, expressions such as hopeful, joy, encouraged, and optimistic were identified as positive responses whereas, sad, ashamed, anger and guilt were identified as negative responses. This resulted in 80% of the sample having positive feelings toward the advertisement using positive appeals and 90% of the sample having negative feelings toward the advertisement using negative appeals (see Appendix 6). As expected, due to the positive appeal advertisement having a moment of a negative appeal as well, the video was also identified with some negative feelings, namely sad. However, all but two of those identified more positive feelings than negative. Therefore, it can be seen that the overall perception of the advertisement using the positive appeal remains positive.

3.3.3 Sampling

To be able to conduct a conclusive statistical analysis, we aimed for a sample size close to one hundred. Our sample consisted of students at Jönköping University since we believe that they are exposed to similar information. As this study did not aim to examine the awareness of palm oil, the sample was chosen based on the assumption that students most likely have some knowledge about the issue. The initial sampling method was convenience sampling, meaning sending the survey personally to people in our contacts on social media platforms. These people were then encouraged to forward the survey to people in their contacts. Therefore, our sampling method combined convenience and snowball sampling. This allowed us to have a larger sample size than we would have had with only convenience sampling and diversify our sample by including people who are not in our direct contacts. Our convenience sample consisted of 87 individuals. The respondents were given three weeks to complete the survey. During this time, they were also sent reminders. The survey was closed after the three weeks since the authors had already used all their contacts and the snowball sampling started to reach people outside of the intended sample. In total there were 91 replies out of which six were not Jönköping University students and were thus excluded.

During the first analysis of the data, outliers were discovered. Outliers are extreme values which do not comply to the general pattern and differ substantially from other observations. This indicates that these outliers can cause a distortion to the results of

26

statistical analysis, which is why they are usually excluded from a data set (Collis & Hussey, 2014). The number of outliers was eight in total, and after the exclusion of these outliers along with the non-Jönköping University students, the number of responses used for the final analysis was 77.

3.3.4 Questionnaire Design

Two questionnaires were made with the only difference being the video advertisement. The reason for this was to be able to, with help from an online random redirector, randomly distribute who would see which advertisement. An alternative way was considered, which would have included selecting our sample beforehand, then dividing it randomly into two groups. After that one of the groups would have been sent the link to the survey with the negative appeal and the other with the positive one. The disadvantage of this method is that it does not allow snowballing or sharing the link on social media platforms. For these reasons, the online random redirector was used, which enabled us to have only one link that was sent and forwarded to our sample. Furthermore, the system made sure that we would get an almost equal number of answers for both appeals. To use the online random redirector, the survey had to be made with Google Forms. The questionnaire design was adopted from Fishbein and Ajzen’s (2015) book “Predicting

and changing behaviour” which connects to the elements of the theory of planned

behaviour. According to Fishbein and Ajzen (2015), the object of the factors that affect the intention to behaviour change must consist of and be assessed on the same target, action, context, and time element of the behaviour in question. Therefore, the behaviour must first be well-defined. The behaviour of interest in this study was avoiding the consumption of products containing palm oil.

The first part of the questionnaire handled demographic characteristics. Here the respondents were asked about their age, gender, and nationality as well as what they associated with palm oil. From the pilot survey, a common belief was that vegans, environmentally conscious people and individuals involved in environmental or animal protection organisations would be most likely to avoid palm oil. Therefore, questions about these matters were included in the first part to observe if they have an influence on how the appeals are perceived and if they were more likely to form an intention to behavioural change. However, there was not enough data for a conclusive statistical analysis. In the second part of the questionnaire, respondents were given brief, neutral

27

information about the usage of palm oil. The reason for this was to give the respondents a background before viewing the video and to even out the imbalance of informational content of the two advertisements. Thereafter, about half of the sample saw the advertisement using negative appeals and the other half saw the advertisement using positive appeals. After viewing the video, the respondents were asked about their feelings towards the advertised issue.

The remaining parts of the questionnaire explored the attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control of the participants. For the attitudes, questions about the direct attitudes, behavioural belief strength and outcome evaluation were asked. When it comes to subjective norms, the beliefs about what the generalised referent views as appropriate or inappropriate behaviour as well as the respondent’s motivation to comply with or mimic the referent are assessed. When assessing perceived behavioural control, it is advised by Fishbein and Ajzen (2015) to measure this by asking direct questions about the capability to perform a behaviour. Additionally, the belief of the likelihood that specific factors may make it easier or more difficult to perform the behaviour was measured. The full questionnaire can be seen in Appendix 7. All questions regarding the elements of the theory of planned behaviour were accompanied by a Likert-style seven-point scale with contrasting adjectives.

3.4 Coding of the Data

Before entering the data into SPSS, a codebook was created with instructions on how to transform the responses from the questionnaires into a format that SPSS understands (Pallant, 2010). In this codebook (Appendix 8), all variables were defined and labelled, and numbers were assigned to each response. For the first part of the questionnaires, each predefined response was given a number where the first listed response was given the value of 1, the second as 2 and so on. Further, since the question of birth year already generated a numeric answer this did not need to be coded in another way. Respondents were also given an identification number so that they could easily be identified in the dataset.

For the Likert-scale responses, Fishbein and Ajzen (2015) discuss whether these should be coded using a scale from -3 to +3 or 1 to 7. However, from their discussion, it is evident