De-motivators among Temporary Agency

Workers in the Industrial Sector

A case study of Proffice AB in Jönköping

Bachelor thesis within Business Administration

Authors: Johansson Sofia 850702-1924 Müller Peder 850623-0195 Vestin Karolina 851013-0142

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express special gratitude and appreciation to several people that have helped during the process of writing this Bachelor Thesis.

First of all we wish to thank the managers at Proffice in Jönköping for allowing us to use their company as a target for this case study as well as giving consent to be inter-viewed.

The authors would also like to thank the managers at the host companies and all the temporary agency workers at Proffice that are employed within the industrial sector. The participation of these three parties allowed us to get a full insight in the problem area and the authors would not have been able to conduct this case study without their contribution.

The authors also wish to give special appreciation to our tutor, Dr. Erik Hunter for his guidance and support throughout the process of conducting this case study.

Sofia Johansson Peder Müller Karolina Vestin

___________________ ____________________ ____________________

Jönköping International Business School 2009-12-09

Bachelor Thesis in Business Administration

Title: De-motivators among temporary agency workers in the indus- trial sector – A case study of Proffice AB in Jönköping. Authors: Sofia Johansson, Peder Müller, Karolina Vestin Tutor: Dr. Erik Hunter

Date: December, 2009

Subject terms: Temporary agency workers, De-motivators, Temporary Agencies, Proffice, Industrial Sector.

Abstract

Purpose To identify among temporary agency workers at Proffice AB in Jönköping, which de-motivators constitute a problem with-in the with-industrial sector, and further propose a framework that can be used as an indicative tool for alleviating these prob-lems for companies working in the sector.

Background Temporary agency work is an increasingly growing industry. In the EU it has been the fastest growing market the last 20 years. At the same time, the rate at which temporary agency workers (TAWs) quit their jobs due to dissatisfaction is high-er than for most industries. Research on the subject has dis-covered that this is due to underlying reasons that emerge in the everyday work of the TAWs. These are labeled de-motivators. This research is aimed at the industrial sector, a sector within temporary agency work that has been over-looked in previous research. Due to the special working con-ditions, it contains many de-motivational factors, making it an interesting area to research.

Method In order to answer the purpose, interviews with managers at Proffice (a Swedish temporary agency), TAWs at Proffice, and managers at host companies have been conducted in or-der to test motivational theories, discover new de-motivators, and gain knowledge in order to develop a new framework for dealing with de-motivators subjected to TAWs within the industrial sector. Since the interviewees are differ-ent types of responddiffer-ents, the methods of interviewing have varied between being semi-structured, and unstructured. Conclusion As a result of the case study, the authors suggest a framework

for how managers at temporary agencies and host companies could prioritize dealing with the most important de-motivators in accordance with the empirical findings. This framework indicates that previous research done on de-motivators among TAWs does not completely correspond to TAWs within the industrial sector.

Kandidatuppsats i Företagsekonomi

Titel: De-motivations faktorer för ambulerande konsulter inom industri sektorn – En fallstudie av Proffice AB i Jönköping.

Författare: Sofia Johansson, Peder Müller, Karolina Vestin Handledare: Dr. Erik Hunter

Datum: December, 2009

Ämnesord: Ambulerande konsulter, De-motivations faktorer, Proffice, Industri sektorn.

Sammanfattning

Syfte Att identifiera, bland ambulerande konsulter anställda på Proffi-ce AB i Jönköping, vilka de-motivations faktorer som utgör ett problem inom industrisektorn samt föreslå ett ramverk som kan användas som ett indikativt instrument för att mildra dessa pro-blem för företag som är aktiva inom sektorn.

Bakgrund Bemanningsbranschen är en alltmer växande industri. Inom EU har den varit den snabbast växande branschen de senaste 20 åren. Samtidigt är graden av ambulerande konsulter som säger upp sig från sina arbeten på grund av missnöjdhet högre än för många andra branscher. Forskning visar att detta beror på under-liggande problem i den dagliga arbetsmiljön. Dessa problem kallas för de-motivations faktorer. Den här studien är riktad mot industri sektorn, en sektor som har blivit förbisedd i tidigare forskning gällande ambulerande konsulter. Industri sektorn sys-selsätter många konsulter och på grund av de speciella arbets-förhållandena innehåller arbetet många de-motivations faktorer, vilket gör den till en särskilt intressant bransch att utforska.

Metod För att kunna besvara syftet har intervjuer genomförts med che-fer på Proffice, cheche-fer på de företag konsulterna arbetar på, samt med ambulerande konsulter anställda av Proffice. Detta har gjorts för att erhålla kunskap om ämnet, kunna testa de-motivations teorier, samt finna oupptäckta de-de-motivations fakto-rer. Med hjälp av detta ska ett nytt ramverk för hur man hanterar de-motivations faktorer inom industri sektorn föreslås. Då de som har intervjuats är både chefer samt konsulter, så har både semi-strukturerade och ostrukturerade intervjutekniker använts.

Slutsats Som ett resultat av denna fallstudie föreslår författarna ett ram-verk för hur chefer på bemanningsföretag och företag som kon-sulterna arbetar på, kan prioritera att hantera de mest relevanta de-motivations faktorerna i enlighet med de empiriska resulta-ten. Ramverket indikerar att de-motivations faktorerna som åter-funnits bland de ambulerande konsulterna i tidigare forskning inte till fullo stämmer överens med de de-motivations faktorer

Table of Contents

1

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1

1.2 Introduction to Proffice AB ... 3

1.2.1 Proffice Jönköping ... 3

1.3 Problem discussion and Research Questions ... 4

1.4 Purpose ... 5

1.5 Structure of Study... 6

2

Theoretical Framework, Part 1. ... 7

2.1 The Temporary Agency Industrial ... 7

2.1.1 Temporary Agency Work ... 7

2.1.2 Types of Temporary Agency Employments and Their Conditions ... 8

2.2 The Industrial Sector ... 9

2.2.1 Proffice Employees within the Industrial Sector ... 9

2.3 De-motivators vs. Motivators ... 10

2.4 De-motivators ... 10

2.4.1 De-motivators within the Temporary Agency Sector ... 12

3

Methodology ... 14

3.1 Research Approach... 14 3.1.1 Case Study ... 14 3.2 Selection of samples ... 15 3.3 Research Strategy... 16 3.3.1 Pilot Study ... 16 3.3.2 Questioning Techniques ... 16 3.3.3 Listening Skills ... 173.3.4 Initial Interviewing Activities ... 17

3.4 Data Collection ... 18

3.4.1 Primary and Secondary Data. ... 18

3.4.2 Interviews ... 18

3.4.3 Data Display ... 20

3.4.4 Data Reduction ... 21

3.5 Validity, Reliability, and Generalizability ... 21

3.6 Criticism to Choice of Method ... 22

4

Empirical Findings ... 23

4.1 Interviews with Managers at Proffice in Jönköping ... 23

4.1.1 Unclear expectations ... 23 4.1.2 Performance Appreciation ... 23 4.1.3 Goals ... 24 4.1.4 Communication ... 24 4.1.5 Salary ... 25 4.1.6 Powerlessness... 26 4.1.7 Belongingness ... 27

4.1.8 Clients (Host Companies) ... 27

4.2 Interviews with Managers at the Host Companies ... 28

4.2.2 Communication ... 29

4.2.3 Belongingness ... 29

4.2.4 Performance Appreciation ... 30

4.2.5 Clients (The Host Company itself) ... 30

4.3 Interviews with Proffice TAWs within the Industrial Sector ... 31

4.3.1 Organizational Politics ... 31

4.3.2 Unclear Expectations ... 31

4.3.3 Autonomy and Variety ... 32

4.3.4 Clients (Host Company) ... 33

4.3.5 Communication ... 33 4.3.6 Goals ... 34 4.3.7 Salary ... 35 4.3.8 Powerlessness... 35 4.3.9 Belongingness ... 36 4.3.10 Performance Appreciation ... 36

4.4 Newly discovered De-motivators ... 37

4.4.1 Culture ... 37

4.4.2 Job Insecurity... 37

4.5 Summary of Interviews with TAWs. ... 38

5

Theoretical Framework, Part 2. ... 39

5.1 Founding Theories ... 39

5.1.1 Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivational Factors ... 39

5.2 Herzberg’s Two Factor Theory ... 39

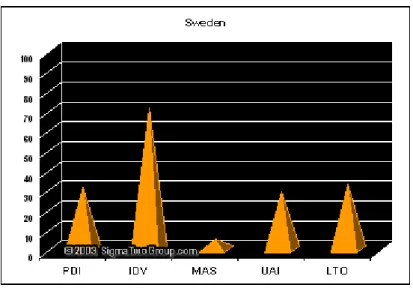

5.3 Swedish Culture According to Hofstede ... 40

5.4 Motivational Theory Concerning De-motivators within the Industrial Sector ... 42

5.4.1 Performance Appreciation ... 42

5.4.2 Belongingness ... 43

5.4.3 Communication ... 44

5.4.4 Job Insecurity... 44

5.4.5 Autonomy and Variety ... 45

6

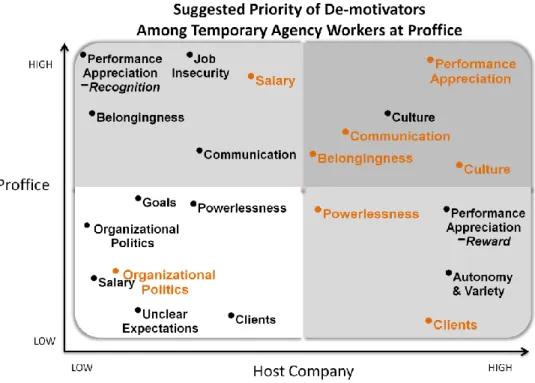

Analysis and Suggestion of Framework ... 46

6.1 Suggested Priority of De-motivators ... 46

6.2 Analysis of Found De-motivators... 47

6.2.1 De-motivators connected to Proffice ... 47

6.2.1.1 Job Insecurity ... 47

6.2.1.2 Communication ... 48

6.2.1.3 Belongingness ... 49

6.2.1.4 Performance Appreciation – Recognition ... 50

6.2.2 De-motivators connected to the Host Companies... 50

6.2.2.1 Autonomy and Variety ... 51

6.2.2.2 Performance Appreciation – Reward ... 51

6.2.3 De-motivators related to both Proffice and the Host Company ... 52

6.2.3.1 Culture ... 52

6.2.4 Remaining De-motivators ... 54

6.2.4.1 Clients ... 54

6.2.4.6 Organizational Politics ... 56

7

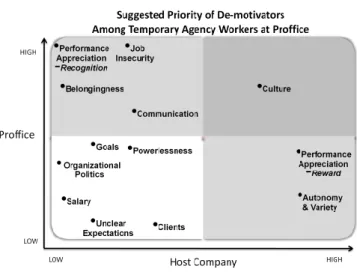

Conclusion ... 57

8

Discussion and Reflections ... 59

8.1 Final Comments and Critique of Study ... 59

8.2 Suggested Further Research ... 59

List of References ... 61

Appendices ... 65

Appendix 1 - Interview questions for the managers at Proffice ... 65

Appendix 2 - Interview Questions for Managers at the Host Companies... 67

Figures

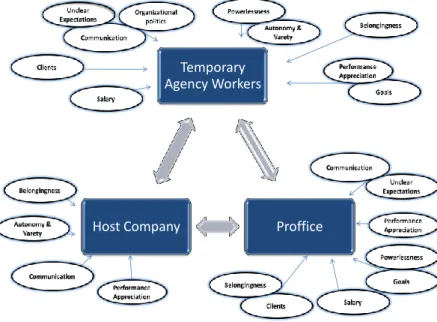

Figure 2-1 The Triangular Relationship ... 7Figure 3-1 De-motivators Sorted on Members in the Triangular Relationship ... 20

Figure 3-2 Relationship Matrix Visualizing the De-motivators ... 20

Figure 4-1 Summary of De-motivators Accordingly with the Empirical Findings ... 38

Figure 5-1 Cultural Dimensions in Sweden ... 41

Figure 6-1 Suggested Priority of De-motivators for Proffice and the Host Company 46 Figure 7-1 Suggested Priority of De-motivators for the New Framework ... 58

1

Introduction

This chapter will introduce the reader to the following case study. The section begins with introducing the background of the research followed by the problem area, research questions, and the purpose of the study. Further, the delimitations will be declared and the disposition of the study will be presented.

1.1 Background

Nearly 20 years ago, the monopoly on job recruitment of the Swedish Public Employment Service (AMS) was abolished, and the market opened up for additional employment agencies to enter. The industry of temporary employment soon became one of the fastest growing industries in Sweden (Aaronson, 2003). Temporary employment is defined as a legal relationship between a client and a temporary employment agency whereby the agency, in return for a fee, places its own employees at the disposal of the client to perform work in the clients’ business (Blanpain & Graham, 2004). The new market supplied companies with flexible recruitment solutions that were traditionally viewed as replacements for regular employees. These replacements were initially made in cases where the regular employees were absent for reasons such as illnesses and vacations (Nollen, 1996). Today, temporary agency workers (hereafter known as TAWs) are seen as a competitive and effective way of cutting labor costs, and as an effective recruitment solution for companies in order to respond to market fluctuations (Holmlund & Storrie, 2002). There are also positions that are staffed only with temporary employees and thus, some regard temporary workers as a critical part of their personnel strategies (Von Hippel, Mangum, Greenberger, Heneman, Skoglind, 1997). Temporary agency work is an increasingly growing form of employment. In the European Union alone, it has been the fastest growing type of employment for the last 20 years (European Trade Union Confederation, 2007). Subsequent to the abolishment of the AMS monopoly in Sweden, the industry has grown fivefold in terms of number of workers since the 1990's (Blanpain & Graham, 2004). The growing market indicates the importance of highlighting the problems that have arisen with this new business phenomenon.

Alongside this increase, the temporary agencies have according to previous research struggled with the problem of de-motivated employees (European Trade Union Confederation, 2007). Temporary employees have expressed that they are unsatisfied with their working conditions, and further, the rate of resignations has significantly increased when compared to other sectors (Ward, Grimshaw, Rubery, Beynon, 2001). The factors underlying these issues are commonly labeled de-motivators and can appear in many different forms (Spitzer, 1995). The uncertainty acceptance, flexibility, and the fact that the workers have less job security than regularly employed workers are some examples of what makes this type of employment different to permanent employments. This creates special working conditions for TAWs, which makes the issue of de-motivation different when compared to regular employment conditions (European Trade Union Confederation, 2007).

Previous research shows inconsistency in conclusions regarding the most relevant de-motivators among TAWs. One research shows that the greatest disadvantages can be economic insecurity, lack of responsibility, and discontinuity of social relations at the

that the main concern is the inconsistency between the temporary agency firm and the firm at which the employee is performing his or her work (Fargus 2000). A third research states that the main cause for de-motivation for TAWs is that compared to regular employees, TAWs are paid less, and experience less favorable working conditions (Nienhüser & Matiaske, 2000). In other words, previous research comes to different conclusions regarding the issue of de-motivators within the temporary agency sector. Some researchers suggest that the social aspects are most relevant for de-motivation, while others are of the opinion that the professional aspects should be given the most attention. This indicates a gap in the academic research regarding which de-motivators that seem to be the most relevant to this sector and opens up for further research on the subject.

Important to mention is that there are different types of TAWs. These can be divided in-to; management, IT, strategy, and industrial workers (Block, 2007). Different types of TAWs are exposed to different working environments and conditions, and therefore need to be treated separately in terms of problems associated with their work. Previous research seems to have focused mainly on the management, IT and strategy workers and almost none on the industrial workers. One reason as to why these sectors seem to have been more thoroughly researched is because TAWs working within the management, IT, and strategy sector have more influence and play a more important part in the deci-sion making process compared to the TAWs working in the industrial sector (Creplet, Dupouet, Kerna, Mehmanpazir, Munier, 2001). Another reason as to why the industrial sector has been poorly researched could be the fact that generally, the rate of employee turnover within the industrial sector is significantly higher than for other sectors. This might be an explanation for the lack of consistency regarding de-motivators in previous research. The reason as to why this is, is that companies often bring in TAWs as a tem-porary solution during work accumulations (Ward et.al., 2001). Therefore, it is the au-thors belief that TAWs within the industrial sector might be perceived as less exposed to de-motivators due to many short term assignments.

The TAWs within the industrial sector are facing more risks in their work than other groups of TAWs due to their work with for example warehousing, and heavy machines. For example, several respondents have in the interviews that can be found in the empiri-cal findings, expressed that the safety routines are not completely explained to them, es-pecially when they work at companies during shorter assignments. Further they are im-posed to less favorable working conditions much because of the nature of their work (European Trade Union Confederation, 2007).

Within this thesis, the authors approached the temporary agency Proffice AB with the intention of investigating existing de-motivators among TAWs within the industrial sec-tor in Jönköping. Proffice will be used as a source of the case study, and as a foundation for the empirical material. A further aim of the authors is to propose a framework for dealing with de-motivational problems. This framework has the intention of being used as a foundation for future studies, and as an indicative tool for other companies dealing with de-motivational issues within the industrial sector.

To summarize the importance of this study; the previous research made on de-motivation may or may not be applicable to the industrial sector since, as previously ex-plained, the attention has been given to the TAWs working in the management, IT, and strategy sector who face different job assignments and working conditions than the TAWs within the industrial sector. De-motivators among industrial workers thus

con-duct a highly interesting area of research, especially since the temporary industry has grown in such a high rate in recent years. Further, since the gap in previous research al-so includes a lack in research concerning which de-motivators that are of highest impor-tance to the TAWs within the industrial sector, this area also needs to be researched fur-ther.

1.2 Introduction to Proffice AB

Proffice is one of the major employment agencies in Sweden, with a turnover of over SEK 4,2 billion. In 2008, when many other companies were struggling with layoffs and poor results due to the recession, the recruiting industry in Sweden grew by 13 percent, and Proffice alone grew by 20 percent (Proffice, 2008). Proffice was chosen as a target for this case study due to its specialization on the Nordic market and its high involve-ment in the industrial sector.

Proffice AB is a temporary agency firm that originated in “Snabbstenografen”, a typing office founded by Berit Flodin in 1960 in Stockholm, Sweden. Mrs. Flodin together with her husband Hans Hägglund, initially provided typing agency services and secreta-ries for other companies to hire. Later on, telephone operators, and administrative assis-tants were added to their offered pool of personnel. In 1976, a new office was founded in Malmö, and in 1986-1987 two more offices opened up in Uppsala and Gothenburg, Sweden. The new establishments were successful and the company expanded by pro-viding an even wider range in personnel that could be hired. During 1987, all chapters were brought together under the name Proffice, and in 1989 the current main owner Christer Hägglund acquired the company. In 1997, Proffice bought the Norwegian company Personell-Assistanse and in the same year Proffice Care, that recruits and hires out medical personnel, was launched. The year after, in 1998, Proffice expanded to in-clude the Danish market, and in 1999 the company started its operations in Finland as well as got listed on the Stockholm Stock Exchange. Today Proffice has over 12,000 employees and about 100 offices spread over Sweden, Denmark, Norway and Finland. Its customers consist of both private and public companies and the company foremost markets itself for its speed and flexibility. (Proffice, 2009).

Proffice is to “Be the most successful staffing company in the Nordic Region” (Proffice, 2009) and the company currently claim to be a Nordic specialist in Temporary staffing, Recruitment, and Career & Development. Temporary staffing stands for 91% of opera-tions, Recruitment stands for 5%, and Career & Development for the remaining 4% of total operations. Within temporary staffing, which this case study is focusing on, Prof-fice specializes in the economic sphere, administration, customer service, IT, Industry & Production, Warehouse & Logistics, and care. (Proffice, 2009).

1.2.1 Proffice Jönköping

One of Proffice’s 100 offices is located in Jönköping, Sweden. There are currently 6 full time employees at the office, which each is responsible for different areas of operations. There are three major areas of operations handled at the Jönköping Office:

Key Accounts Growth

Each area of operations at the Jönköping office is managed by 2 employees. Responsi-bilities are further divided within these areas of operations. Key Accounts deal with the Public Authorities in Sweden. Within this area, one employee deals more directly with temporary staffing, and the other is more involved with customer relations. Growth is managed by one employee that is responsible for the industrial industry, logistics, IT, and engineering, and the other employee deals with services, and staffing within the field of economics. Of interest to this case study are both the manager for Key Accounts who is involved with the temporary staffing, and the manager for Growth that is respon-sible for the industrial sector. These managers both deal with the TAWs within the in-dustrial sector and are thus highly relevant to the study. The area of recruitment is not relevant for this study since it does not deal with the form of industrial work that the au-thors are focusing on.

1.3 Problem discussion and Research Questions

De-motivators are becoming increasingly noticed as a problem in the workplace, and one of the reasons for why employees consciously or sub-consciously put less effort and energy into their work after a period of time (Spitzer, 1995). The problem of having an unmotivated workforce has indirect effects such as poor working commitment, but can also cause direct effects of financial loss through for example high employee turnover (Gupta-Sunderji, 2004).

Previous research done by the European Trade Union Confederation (2007), indicates that TAWs are less satisfied with their employments and working conditions than per-manent employees. Most workers seem to prefer secure, perper-manent employment and mostly engage in temporary work to gain experience, or while searching for a perma-nent job (Kvasnicka, 2005). This makes de-motivators within temporary agencies espe-cially interesting to investigate, since there might be a connection between the de-motivators and the level of dissatisfaction within this sector in general, and the industri-al sector in particular. There is some information to be found about temporary agency work in the industrial sector, but none that specifically deals with de-motivators. There-fore, the authors found that there is room for further research within this area.

The authors have identified three underlying reasons as to why de-motivators within the industrial sector for TAWs need to be researched:

First, the use of temporary workers has increased significantly in order to respond to the constant demand of cost efficiency and fluctuations in the market (Holmlund & Storrie, 2002).The growth in temporary employment during the last decade is one of the most spectacular and important events that have occurred in labor markets recently(Nollen, 1996).As the need for temporary agency employees increases, we might also conclude that the accompanying problem of de-motivation in the workforce will also increase. The de-motivation problems in temporary agency work cannot afford to be ignored when temporary employment now stands for around 1,3 per cent of total employment in Sweden (Almega, 2009), and the industry is expected to double in the future. (Blanpain & Graham, 2004).

Second, previous research on de-motivators among temporary agency workers has not agreed upon which de-motivators that these kinds of employees are most concerned with. Different research deals with different de-motivators, but within the industrial

sec-tor, there is little research that deals with these problems. Overall there seem to be little interest in the TAWs within the industrial sector and there is almost no research to be found. Therefore the authors experience a gap in the research, which means that there is room for more research regarding both TAWs within the industrial sector, and the de-motivators that this area is struggling with.

Third, de-motivators occur in most organizations, but temporary agency work has the worst record for working conditions judged on a number of indicators, including repeti-tive labor, and the supply of information about workplace risks (European Trade Union Confederation, 2007). This creates special working conditions for the TAWs, which means that existing de-motivational theories need to be treated accordingly.

To elaborate on the problems mentioned above, research questions will be applied in addition to the purpose in order to investigate how de-motivators within the industrial sector are perceived from both the perspective of the managers and the employees. Both parties have an interest in the result, and both parties will affect the outcome of the study. The research questions are:

1. What types of motivators are there in general, and in particular, which de-motivators have previously been discovered among temporary agency workers? 2. Do the managers at Proffice or the Host Companies currently pursue any actions

to reduce de-motivators, or motivate the TAWs working in the industrial sector? If so, what is done?

3. Which de-motivators are by TAWs working in the industrial sector perceived as most problematic, as well as reoccurring?

4. Based on both existing theories and empirical findings, how could managers for temporary agencies and host companies best deal with the most problematic de-motivators for TAWs working in the industrial sector?

1.4 Purpose

To identify among temporary agency workers at Proffice AB in Jönköping, which de-motivators constitute a problem within the industrial sector, and further propose a framework that can be used as an indicative tool for alleviating these problems for com-panies working in the sector.

1.5 Structure of Study

The introductory chapter presents the background to why the problem with de-motivators is an area worth of research. The problem discussion presents previous research within the field of de-motivation and how this can be related to the case study. Further research ques-tions and purpose are presented.

This chapter deepens previous research by explaining the theoretical framework regarding temporary agen-cies, TAWs, de-motivators and the industrial sector that Proffice are involved with. This chapter will later work as a foundation for the empirical study.

The methodology chapter provides information regard-ing the research approach and strategy that the authors have chosen for the case study. Further, the selection of samples, data collection, validity and criticism of method is presented.

In this section, empirical findings from the interviews with managers at Proffice, TAWs and managers at us-er companies are presented. Also a summary of the discovered de-motivators in the industrial sector will be presented. The empirical findings will be used as a base for the analysis.

In the second theoretical framework founding theories and motivational theories concerning de-motivators within the industrial sector will be presented. These theories will constitute a supplement to previously pre-sented theories and work as a foundation for the new framework

In this chapter the empirical findings are analyzed and evaluated with help of the theoretical frameworks. Further a new framework for treating the problems of de-motivators within the industrial sector is presented. In this chapter the authors presents a generalized summary of the most important findings in the study as well as a summary of the framework.

In the last chapter personal reflections, limitations and how these were overcome are presented. Finally, sug-gestions on further studies are presented.

2

Theoretical Framework, Part 1.

This chapter will answer Research Question 1 by presenting the theories behind tempo-rary agency work, the industrial sector, and de-motivators in general and among TAWs. It will also explain the difference between de-motivators and motivators.

2.1 The Temporary Agency Industry

Temporary employment is a modern invention that has caused a lot of debate on the la-bor market. This is due to its significant growth in such a short period of time (Hol-mlund & Storrie, 2002) together with the special working conditions this type of em-ployment implies (Ward et al., 2001). In the European Union, temporary agency work has been the fastest growing form of employment over the last twenty years. In Sweden alone, the use of TAWs has increased by more than 500% (European Trade Union Con-federation, 2007). Still, the potential growth within the industry is high. According to Blanpain & Graham (2004), the industry has a potential to double in Europe in the near future.This makes the market for temporary agencies of great interest to research, and even though there exist previous studies, this field still has unexploited areas that are in need of further investigation.

According to Blanpain & Graham (2004) there are several reasons as to why companies use TAWs. The most common reason is that the companies want to increase labor flex-ibility, and consequently cut labor cost. Also, the trend of focusing on core competen-cies has increased the use of temporary agencompeten-cies in terms of hiring staff for positions outside the core activities. Finally, for many companies, using temporary agencies in-stead of hiring on their own has also become a fast and inexpensive way of screening employees. All of these reasons have contributed to the market growth and made tem-porary agency work a type of business to be reckoned with on the labor market.

2.1.1 Temporary Agency Work

According to Biggs & Swailes (2006), temporary agency work is a special kind of em-ployment where a person is employed by a temporary agency (staffing company) that in turn hires out that person to another company. The temporary agency function is to be an intermediary between the host company that is in need of personnel, and the em-ployee. The authors further explain that this is commonly called the “Triangular Rela-tionship” which can be seen in figure 2-1, and describes the relationship between the Temporary agency worker, the temporary agency firm, and the host company.

As shown in Figure 2-1, the temporary agency is responsible for everything except for managing the daily work, which falls on the responsibility of the host company where the temporary agency worker carries out his or her daily work. The host company signs a contract concerning the hiring out of employees with the temporary agency, and con-sequently pays a commission to the agency for its services (Biggs & Swailes, 2006). The role of the temporary agency firm is to be able to provide their customers with edu-cated and knowledgeable employees within specific fields (Bronstein, 1991). This al-lows the host company to rapidly replace temporarily absent personnel, or add person-nel when there is an increase in workload (European Trade Union Confederation, 2007). The temporary agency manages all the costs and administration concerned with the TAWs, and the employee reports his or her work hours and salary claims to the agency (Nienhüser & Matiaske, 2006).

2.1.2 Types of Temporary Agency Employments and Their Conditions To be able to investigate de-motivators among Proffice employees further on in the study, the following section provides background information on the different employ-ments that a TAW can hold. The section below is provided in order to give the reader an understanding of why the authors have chosen to interview TAWs employed under dif-ferent contracts within Proffice, and how their salary is regulated.

There are several different kinds of employment alternatives involved in temporary agency employment. A person can be employed as a civil servant and thus be employed under the HTF/Academic Unions agreement (HTF, 2009). To be employed as a civil servant means being employed at an office. A temporary agency worker can also be employed under the collective wage agreement by LO; The Swedish Trade Union Con-federation. This employment is vocationally oriented and the employed worker does not necessarily have any specialized qualification (LO, 2009). Another common ment, which is also regulated under the collective wage agreement, is hourly employ-ment. Temporary agencies are not allowed by Swedish laws and regulations to hire part time employees, thus temporary agencies hire workers on an hourly basis under the condition that the workers have an additional occupation such as studies or another hourly employment. The special law policy for the Swedish labor market is known as “The Swedish model”. It includes different regulations, and the two key elements are the centralized wage bargaining, and the active labor market policies. (Freeman, Topel, Swedenborg, 1997). These regulations were implemented in order to protect employees from being exposed to adverse working conditions (Blanpain & Graham, 2003). “The Swedish model” thus means more strict regulations for employers, and better working conditions for the employees (Freeman, Topel, Swedenborg, 1997). These wage agree-ments and the labor market policies are what make the “Swedish Model” unique com-pared to those of other countries. In many other countries, TAWs are faced with worse working conditions and salaries than those of regular employees. However, even though TAWs might be better off in Sweden compared to other countries, the TAWs still have less beneficial employment conditions than those of regular employees (European Trade Union Confederation, 2007), which contributes to the authors’ interest in TAWs.

To further elaborate on what “The Swedish Model” contributes with, the wage agree-ments regarding TAWs needs to be explained. The TAWs employed under LO in Swe-den are guaranteed a minimum wage that is personal to each worker. This wage is called “Genomsnittligt förtjänstläge” (GFL), which roughly explained means that the TAW is guaranteed a certain amount of income independent of how many hours you are hired

out during a month. Every TAWs’ salary follows each host company’s average wage level. This means that a the salary of a TAW might vary since they are performing work at different companies, but due to the GFL, the TAW is guaranteed a personal minimum wage. The workers under the LO agreement also have the right to receive a minimum wage each month, even though they have not been assigned to any work at a host com-pany (LO, 2009). This is however not the case for the hourly employees, since they are hired out to the host companies on different premises, but they are still regulated under the GFL (Almega, 2009).

Further, according to Almega (2009) the civil servants have another form of guaranteed income. They have the right to receive salary for a minimum of 133 hours a month, and if they work additional hours they receive a special incentive pay. However, the worker is not guaranteed to work these 133 hours, or any specific amount of hours per month for that matter.

In summary, despite the protections afforded Swedish TAWs compared to TAWs in many other countries, this special kind of employment still seem to have room for im-provement since there are many factors that differ from regular, steady employments.

2.2 The Industrial Sector

The industrial sector, in this case study, refers to the types of businesses with forms of production that are characterized by factory work. These businesses can for example be operating in the manufacturing industry, production industry, or the engineering indus-try. Common types of job assignments within this area of industry are; assembling, op-erating machinery, opop-erating trucks, transporting goods, and various warehouse chores. (Nationalencyklopedien, 2009).

2.2.1 Proffice Employees within the Industrial Sector

In Jönköping, both Growth and Key Account deal with the industrial sector. Several of the public authorities employ TAWs to work at their warehouses and similar facilities. The area of Growth also holds several, both major and minor, companies within the in-dustrial sector that are in need of warehouse labor in particular. The most common job assignments for the temporary agency workers include; packaging, operating trucks, collecting orders, and assembling. These job assignments can be physically heavy and thus there are mostly men employed within this sector. To work within the industrial sector implies being subjected to a higher level of risk for workplace accidents, and a lower level of safety for the TAWs, since they are often operating heavy vehicles and machinery. There is also a lot of lifting involved with working within the industrial sec-tor, which can be heavy and wear on the TAWs’ bodies (Europen Trade Union Confe-deration, 2007). Due to the nature of the work within the industrial sector, many of the TAWs work in shifts. The shifts can be scheduled on both days and nights, and they of-ten vary in length. Some user companies might need different amounts of personnel on different days due to variations in workload, and TAWs are thus called in by the tempo-rary agency firm when they are needed. This can be the case for both weekly assign-ments and daily assignassign-ments, which implies that the TAW might not know if he or she is going to work until a few hours before they are needed at the host company. The vari-ation in workload is one of the reasons as to why companies hire temporary agency

At Proffice, the ages among the employees in the industrial sector range from between 18-55 years old. A large amount of the employees are employed hourly due to simulta-neous studies or part time employments outside Proffice, but many are also employed fulltime. Proffice employees within the industrial sector are thus employed under the LO collective wage agreement, and regulated with GFL, or under an hourly employ-ment contract. (Managers at Proffice, personal communication, 2009-10-20).

2.3 De-motivators vs. Motivators

De-motivation and motivation are easily perceived as the opposite of each other, but ac-cording to much previous research they are not. Acac-cording to Herzberg (1991), the pri-mary role of dealing with de-motivators is to adjust the level of dissatisfaction of a per-son. Thus, motivators can only decrease the level of dissatisfaction when de-motivators exist, i.e. when there are factors de-motivating a person in effect, motivational factors cannot increase an employee’s level of satisfaction. He further claims that motivators only can be used to adjust the level of employee satisfaction when de-motivators have been eliminated. (cited in Allen, Wysocki, Kepner, Glasser, 2001). A person is moti-vated when he or she WANTS to do something (Adair, 1990), but at the same time, even though a person wants to do something, they may still be de-motivated whilst per-forming that task. For example, an employee might love to install televisions, but he or she can still experience de-motivational factors, such as a low salary, or lack of perfor-mance appreciation from the manager. In other words, even a task that motivates an employee can be perceived as tedious if the task entails de-motivational factors. This is what mainly separates the two concepts. This theory has its foundation in Herzberg’s “Two factor theory” (Herzberg, 1968), which will be explained in the second part of the theoretical framework.

Spitzer (1995) claims that de-motivators are usually a part of everyday activities, while managers rather impose motivators either consciously or sub-consciously. Spitzer (1995) further claims the de-motivators that exist in an organization are there because managers allow them to be there, indicating that there is a need for managers to actively deal with the subject of de-motivators. Further, Gupta-Sunderji (2004), claim that it is less costly and more effective to reduce de-motivators than it is to increase motivators, giving managers more reason to focus on the issue. This is another reason as to why the authors have chosen to focus on de-motivators as opposed to motivators.

2.4 De-motivators

To be able to answer research question 1, “What types of de-motivators are there in general, and in particular, which de-motivators have previously been discovered among temporary agency workers?” given the fact that there is a lack of research on de-motivation within the industrial sector, this section will address the most common and noticed de-motivators found in previous research. The empirical section will later dis-cover which of these that is applicable to TAWs within the industrial sector.

To be able to grasp the impact that de-motivated employees can have on an organiza-tion, the following section will explain the effects that might occur. De-motivational theory has been studied for a long time, and two well established measurements of de-motivation are lack of job satisfaction, and organizational commitment (Fargus, 2000). Lack within any of these two areas can consequently lead to absenteeism and high em-ployee turnover, which are the two most commonly acknowledged forms of withdrawal

(Ward et.al., 2001). Absenteeism means discontinuous attendance at work. This is a costly personnel problem and can directly lead to reduction in output (Björklund, 2001). Further, lack of attendance at work has been proven to decrease organizational com-mitment (Hackett, 1989). High employee turnover has not only a financial impact, but also adversely affects training, organizational development, and other human resource-development interventions (Björklund, 2001).

The most common signs of de-motivated employees can be; lacks in effort, arriving late, extending breaks, taking less or no initiative, showing frustration, or openly criti-cizing management (Spitzer, 1995). According to previous research done by Robb & Myat (2004), there is a wide spread of motivators, and the range of factors that de-motivates employees is wider than factors that motivate. Therefore, since it is perceived to be easier for managers to grasp, more focus is currently being put on how to motivate employees than on how to diminish de-motivation (Gupta-Sunderji, 2004).

The most common and noticed de-motivators according to previous research done among employees are:

Organizational politics – Involves competition for power, influence, favors, and scarce

promotions (Nollen, 1996).

Unclear expectations of the employee – When there is inconsistency between what is

said and what is done, together with mixed messages being transmitted throughout an organization, employees tend to express frustration. (Spitzer, 1995).

Autonomy and variety – When employees are not allowed to work autonomously with a

variety of tasks that suit their capability, the work tends to be perceived as tedious and unsatisfying (Hunt, 1994).

Clients – The clients can be an important source of de-motivation if they for example

demand more work than what was originally stated, or change projects without explain-ing how it will affect the worker (Hunt, 1994).

Communication – Decisions which will somehow affect the employees are constantly

made. If these decisions and the implications of them are not clearly explained to the employees, people start questioning and accusing management, and de-motivation is bound to arise (Gupta-Sunderji, 2004).

Goals – When goals are not conveyed clearly enough, employees can start to question

what is expected of them, making them de-motivated to carry out their tasks (Gupta-Sunderji, 2004).

Salary – Ian Kessler (2000) suggests that a fundamental source of de-motivation arrives

from employee’s perception of them being wrongly rewarded in monetary terms.

Powerlessness – Refers to the employee’s ability to exhibit power over something or

Belongingness – Is referred to as “the feeling of not belonging” and “the engagement to

the company”, also known as organizational commitment (Jungqvist and Tagesson, 2009)

Performance appreciation- Appreciation is a critical basic human need that includes a

special notice or acknowledgement for the person’s accomplishment (Hansen, Smith, Hansen, 2002).

2.4.1 De-motivators within the Temporary Agency Sector

Since there is little research done on the industrial sector for de-motivation among TAWs, the following section will present found de-motivators for TAWs working with-in the management, IT, and strategy sector.

As mentioned earlier, previous research done by the European Trade Union Confedera-tion (2007) indicates that TAWs are less satisfied with their employments and working conditions than permanent employees. TAWs are constantly moved between different workplaces, and securing collective representation rights is therefore harder for these kinds of employees than for permanent workers. In Sweden, temporary agency workers are secured with a national deal under the trade union Almega as a result of “The Swe-dish Model” (Almega, 2009). However, this deal is, as previously mentioned, not as beneficial as the deal for permanent workers, leaving TAWs with worse working condi-tions (European Trade Union Confederation, 2007).

One example of the less favorable working conditions of this kind of employment is the fact that TAWs have less control over what kind of work they are engaged with and how this work should be performed. They receive less training, do more work in shifts, and have less time to complete their work (Ward, et.al., 2001). To not have the possibil-ity to influence what work to conduct works as a de-motivator (European Trade Union Confederation, 2007). Within this problem, since the TAWs are not able to choose what they are working with, a lack of autonomy and variety can sometimes be a de-motivator. Further, the rate of TAWs being involved in workplace accidents is significantly higher than that of permanent employees. This is due to the fact that little emphasis is being put on information on safety and routines at the host companies. This is also due to the fact that since the employment tax is lower for the temporary agencies if they employ people under the age of 25, most of the employees fit into this category. Since many within this age range have little or no previous work experience, and are thus in many cases not able to determine what is to be considered as common routine, and what to demand, this age average constitutes a problem. (European Trade Union Confederation, 2007). Not informing the TAWs about safety and routines can work as a de-motivator, since no one is motivated to be in a workplace where they do not feel safe. Naturally these problems are also connected to lack of communication, which is one of the most common de-motivators (Nienhüser & Matiaske, 2006).

Temporary agency workers also have less possibility to influence their work situation and to climb the work ladder (Connell & Burges, 2002). This is also reflected in the fact that because permanent employees often are prioritized in the workplace, much of the work offered to TAWs is repetitive and monotonous (Kvasnicka, 2005). According to Nollen (1996) it is common for TAWs to feel neglected and to find themselves to be caught in the grey area of answering to one company and working for another. Since

TAWs are not generally aware of what different managers are responsible for, they of-ten feel confused regarding whom to turn to (Nollen, 1996). This feeling of not belong-ing is a de-motivator that may be more connected to the temporary agency sector than to regular types of employments.

The employment that TAWs employed under the LO collective wage agreement are en-gaged in requires great flexibility since they shift workplace more regularly than a per-manently employed worker (Connell & Burgess, 2002). The TAW is employed on dif-ferent assignments at the user companies, which vary also in length. Thus, the employee at a temporary agency needs to be prepared to shift workplace from one day to another, and also to shift from one geographic location to another (Kalleberg, 2000). This im-plies that managers need to constantly inform the TAWs on where, how, and when the next assignment will take place, who their contact person at the host company will be, and what will be expected of them when at the host company. If the managers fail to uphold a clear communication, this might be a source of de-motivation for the TAWs (Ward et.al., 2006).

An additional de-motivator that TAWs are subjected to, can be the fact that the worker is overqualified for one assignment, and under-qualified for another (Nollen, 1996). The variety of work requirements and geographical location of the host company re-quires the temporary agency worker to be flexible and adjustable in accordance with the current assignment. Due to the mixed assignments, it can be difficult to set clear goals for the TAW (Gupta-Sunderji, 2004). By not having a goal to strive for, the TAW might become de-motivated and question whether his or her work is of importance.

The temporary agency is not always able to provide longer assignments than a month, week, or even a day, which can cause insecurity for the TAW (European Trade Union Confederation, 2007). The TAW might therefore find him- or herself to stand between assignments, and consequently without an income or with a lower salary than was of-fered on the previous assignment. However, as mentioned earlier, the TAWs salaries in Sweden are regulated with by GFL and the TAWs thus are guaranteed at least some in-come. Notice that this does not hold for hourly employed TAWs. The inconsistency in salary, the special regulations concerning salaries for TAWs, and the fact that they do not have the power to affect this since it is regulated by collective wage agreements can all act as de-motivators.

To summarize, TAWs are highly exposed to de-motivators due to the nature of the em-ployment. TAWs are constantly moved between different workplaces, have less control over what kind of work they are engaged with, they get less training, do more work in shifts, and have less time to complete their work. Further, the TAWs are required to be flexible since they shift workplace more regularly than a permanently employed worker, and their work is often repetitive and monotonous. It is also common for the TAWs to find themselves to be caught in the grey area of answering to one company and working for another.

3

Methodology

In this section, the authors present the methods used in order to fulfill the purpose of the study. The section is meant to provide the reader with information on how the study has been performed, as well as information on what strategies that have been implemented to conduct the study.

3.1 Research Approach

In order to fulfill the purpose of this thesis, a case study approach, focused on examin-ing the reasons behind de-motivatexamin-ing factors within the industrial sector for temporary agency workers at Proffice AB, have been implemented. Since the authors wish apply existing theories to an actual organization, in this case Proffice, in order to discover de-motivational factors for TAWs within the industrial sector, a case study approach will be taken. According to Yin (2003), when conducting a case study, it is most suitable to collect qualitative data. Corbin and Strauss (2008) explain that using a qualitative re-search approach, as opposed to a quantitative approach, allows the rere-searcher to view the situation from the eyes of the respondent in order to gain better insight to the prob-lems at hand, and from that, develop empirical knowledge. Patton (1990) further de-scribes that when the aim of a study is to discover what people have experienced by conducting qualitative research, there is less need for standardized measures, which can be created by conducting a quantitative study. In this case study it is important to inves-tigate how the TAWs experience their work situation in order to be able to invesinves-tigate the purpose of the study, i.e. what kind of de-motivators that exists within the industrial sector.

To perform this research the authors have chosen to use both semi-structured interviews and unstructured interviews. The reason for choosing different methods is because the interviews with the managers and the TAWs need be different in order to acquire as credible data as possible. The semi-structured interview style will be applied when in-terviewing the managers. This kind of interview allows the authors to have a list of questions to be covered, but important to notice is that these questions may vary from interview to interview, allowing questions to be varied depending on the flow of the conversation (Saunders, Lewis, Thornhill, 2007). When interviewing the TAWs, on the other hand, the unstructured style of interviewing will be applied. An unstructured in-terview is informal and is used to explore an area of interest in-depth (Yin, 2003). There are no predetermined set of questions, but rather a few open-ended questions or topics imposed by the interviewing person that the interviewee is allowed to talk freely about (Saunders et.al., 2007).

3.1.1 Case Study

A case study refers to research that investigates one or a few cases. It is used as an in-tensive and in-depth study of either a specific organization, an individual, an institution, or a whole society (Gomm, Hammersly & Foster, 2000). According to Yin (2003), con-ducting a case study is helpful when there is a problem that needs to be understood, and experiences and previous research can be extended. Since the purpose of this research is to find out what de-motivators that exist among the TAWs within the industrial sector, a case study approach will help the authors to look into the Proffice organization. The reason for choosing Proffice is their large amount of workers within the industrial sec-tor. Proffice is contracted by both the Public Authorities, which demands large amounts

of industrial workers, as well as many large private companies in need of personnel within the same sector. The problem of de-motivators in the specific context of an in-dustry and a company can be researched, and some additional findings can be added to the small amount of previous research conducted regarding TAWs within the industrial sector. The nature of the case study implies that qualitative research is the given way to investigate a problem since the researchers need to speak to people regarding their expe-riences (Patton, 1990).

3.2 Selection of samples

After discovering the lack of research on de-motivators regarding the TAWs within the industrial sector, the authors chose to focus their research on all three members of what Biggs & Swailes (2006) call the triangular relationship; the employees, the host compa-ny, and Proffice. Interviews will be conducted with both managers at Proffice, managers at host companies, and TAWs working in the industrial sector in order to answer the purpose and research questions of the study. By interviewing all three parties, the au-thors will be allowed to compile a complete image of the problem with de-motivators among the industrial TAWs employed at Proffice.

Due to the nature of this research, a non-probability sampling method will be used when gathering empirical findings. This method is commonly used in case studies, and entails that the sample size will not be pdetermined, but rather evolve, based on what the re-search will discover (Saunders et.al., 2007). The sample size will be set in relation to the research questions and the findings in the interviews that will be useful and credible (Patton, 1990). Important to notice is that the data collection and the authors analysis skills with this research approach is of greater importance than with many other re-search methods since the sample is often smaller than for other methods (Patton, 1990). The particular method of non-probability sampling used for this research will be purpo-sive sampling, which allows the researcher to base the sampling evolvement on judg-ment, in order to suit the purpose of the research. This type of sampling was chosen since it often deals with smaller samples (Neuman, 2006).

To elaborate on the above mentioned method of non-probability, the authors will be provided (by Proffice) with a list of names and occupations of both TAWs at Proffice, and managers at host companies. The authors will then randomly choose whom to con-tact and ask for an interview. When the first sample of 6 TAWs has been interviewed, the findings will be compiled and a decision will be made whether additional interviews should be made. This non-probability sampling method will allow the authors to judge how many interviews that are needed in order to get a fairly correct opinion regarding which de-motivators that exists, and if the managers are doing anything to avoid them. (Neuman, 2006).

The managers at the host companies that have been chosen will be contacted and asked if they agree to an interview. If they do not agree, another manager will be contacted un-til 2 managers have agreed to be interviewed. The managers that will be interviewed from Proffice are the two managers who deal the most with TAWs in the industrial sec-tor.

3.3 Research Strategy

According to Saunders et.al., (2007), before conducting any empirical research, there is a need to establish a strategy. They further suggest that this strategy should be both de-signed to be able to answer established research questions, as well as oriented towards how to collect the data required in order to fulfill the purpose of the thesis. According to Yin (2003), the preferred research strategy when the focus is on a contemporary phe-nomenon within a real-life context, is to conduct a case study. Yin (2003) further offers the technical definition of a case study as “an empirical inquiry that investigates a con-temporary phenomenon within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries be-tween phenomenon and context are not clearly evident”.

Gathering the empirical findings requires knowledge on how to conduct interviews. Burns (2000) offers a guide regarding the most important aspects to keep in mind in or-der to achieve the best results from the interview. The factors applied to this research taken from Burns’ guide regard conducting a pilot study, studying questioning tech-niques, learning listening skills, and understanding initial interviewing activities.

3.3.1 Pilot Study

Before conducting any interviews, a trial version can be conducted on a third part. This pilot study can contribute to enlighten the researcher with the knowledge of which ques-tions to clarify, or if the quesques-tions are relevant at all. The main aim of the pilot study is not to gather new data, but rather to learn.

For this case study the authors will conduct three pilot studies on the semi-structured in-terviews, and perform two unstructured interviews with help from two previously em-ployed TAWs at Proffice. These pilot studies are important tools for the authors to be able to understand which questions that gives relevant answers, and which questions that is misinterpreted or inadequate. By performing the pilot studies the authors are able to get an insight in how the interviewees will respond and react, and how the two tech-niques work in reality.

3.3.2 Questioning Techniques

Burns further suggests that it is important to establish a relationship and build trust with the person one is interviewing. This can be achieved by asking descriptive, non-threatening, questions initially. As time progresses, more structural, and emotional questions can be used. During the interview, making use of “Mirroring”, which means that the last few words the informant says are repeated back to them, should be imple-mented. This will shows the informant that you are interested and understand what they are saying. The same thing can be said about using minimal encouragers such as “I see”, “Can you tell me more?”, and “Hmm”.

In the beginning of all the interviews, the authors will use a script, i.e. presenting our-selves and the case study, as well as assuring the persons interviewed that they will re-main anonymous. The interviewees will also be allowed to ask questions they might have concerning the study or the interview. The semi-structured interview will consist of open-ended questions followed up by additional closed ended questions if necessary. To build trust the authors will start with questions such as: age, length of employment at Proffice etc. The managers will then be asked to present their company and the duties

they have in order to make them feel that they are in control of what information the au-thors have regarding their employment and their company. Then, questions regarding TAWs, what de-motivators they believe that TAWs experience, and what kind of prob-lems they might bring with them will be asked. The managers will also be able to tell if they currently pursue any actions to either decrease de-motivators or increase motiva-tion among the TAWs. The authors will use the mirroring technique in order to convey interest in what the interviewees are saying and to make the transition to the next ques-tion smooth and understandable.

The interviews with the TAWs will also begin with a script and introductory questions concerning age, type of contract, length of employment etc. The author will then care-fully introduce the interviewee to the different topic areas that are divided into; the em-ployee, the host company, and Proffice. The TAWs will be encouraged to tell his or her experiences and feelings regarding these areas, and if necessary the author will impose follow up questions to lead them into the subject of perceived de-motivators. This will however be done with great carefulness in order to maintain the trust between the TAW and the author.

3.3.3 Listening Skills

In order to gain the level of trust required for the informant to convey their true feelings during the interview, which is crucial to the findings, the researcher needs to display ac-ceptance and empathy, convey respect, and create an ethos of trust. This requires the re-searcher to “be an active listener, look interested, and be sensitive to verbal and non-verbal cues” (Burns, 2000). Non-non-verbal communication should be given special atten-tion due to the fact that much of what is being communicated is not actually verbalized, but still of significant interest.

During the interviews both with the managers and the TAWs, the authors will try to maintain a respectful and emphatic manner towards the interviewee. Due to the sensi-tive nature of the topic it is important to read the non-verbal cues, for example if a per-son looks very uncomfortable with a topic or question. De-motivators might be exposed in areas that the authors did not expect, and it is therefore crucial to notice these devia-tions and explore on these if possible.

3.3.4 Initial Interviewing Activities

Before starting the interview, fundamental issues should be addressed. For this research, for example, we make sure that the interviewee is well aware of the fact that he or she is anonymous in order for them to be able to answer truthfully. Burns (2000) further de-scribes that creating an initial rapport with the interviewee by implementing the conver-sational approach of the recursive model is the best suited form of questioning. One negative aspect of using the recursive model, in which the set of questions are not struc-tured, can be that the interviewee strays too far of topic. This can be countered by com-piling a guide containing the general issues to cover. This guide can be revised as fur-ther insight and new topics are introduced during the interview.

The interviews with the managers will be performed at their offices to strengthen their feeling of security and to make sure that they feel relaxed with the surroundings. On

terviews with the TAWs will be held at a small coffee shop in Jönköping that most people are familiar with. This is done in order to ensure anonymity from Proffice and the host companies, as well as to make them feel that they are in a welcoming and re-laxed surrounding. In order to make the interviews as rere-laxed as possible, only one of the authors will be present for each interview. The author will buy the TAW “fika”, present the script, and then lead them into the topics of the case study.

3.4 Data Collection

3.4.1 Primary and Secondary Data.

Within this case study, the authors have chosen to use both primary and secondary data in order to make the research as complete as possible. Theoretical framework part 1 and part 2 are both based on secondary research since the case study is in need of a founda-tion. The reason for dividing the theoretical framework into two parts is that the first one act as a foundation for the empirical section, and the second part presents the moti-vational theories that allow the authors to propose a framework for alleviating the de-motivators that the empirical findings discovered.

The primary data used in this study is gathered from interviews and is displayed in the empirical findings. Primary data is concerned with the collection of new data for a spe-cific purpose (Burns, 2000). The primary data used in this case study will be based on interviews with managers and TAWs that deals with the industrial sector. Secondary da-ta refers to the dada-ta that has already been gathered or summarized for some other pur-pose that is related to the topic being researched (Saunders et.al.,2007). Other sources of secondary data that the authors have chosen to use are gathered from Proffice’s Annual Report 2008, welcome brochures and folders for the TAWs at Proffice, manager guides from Proffice, data from Trade Unions such as the European Trade Union Confedera-tion and the collective agreement union Almega, as well as previous research from Kai-sen Consulting Ltd. regarding motivation of employees. The reason for choosing these secondary data sources are to get an overview of the problem to be able to understand what TAWs, de-motivators, and Proffice are.

3.4.2 Interviews

Data will be gathered through interviews with two managers at Proffice in Jönköping, two managers at two different host companies, and at least 6 TAWs employed in the in-dustrial sector. The number of TAWs to interview will be based on a non-probability sample, meaning that it depends on how the interviews and findings evolve. If for ex-ample the first six interviewees all say the same things, a smaller sex-ample size than in-itially planned could be motivated (Saunders et.al., 2007). The authors have chosen to conduct these interviews differently depending on whether a manager or a TAW is in-terviewed. The interviews with the managers, both at Proffice and the host company, are conducted as semi-structured interviews. Since the managers at Proffice and the manag-ers at the user companies have different responsibilities and experiences of the TAWs, this type of interview allows the authors to vary and adjust the questions according to which type of manager they are dealing with. By being able to vary the questions, the authors can be able to see which de-motivators that the different managers perceive among the TAWs and in what way these might be a problem. Burns (2000) further ex-plains that when conducting semi-structured interviews, the researcher does not need to have a specific schedule for it, but rather develop a guide that will contribute to keeping