MALMÖ

UNIVERSITY

The Relation Between

Temporomandibular Disorders,

Catastrophizing, Kinesiophobia and

Physical Symptoms

Nora Jawad

Xochitl Mena Acufia

Supervisors:

Birgitta Häggman Henrikson

Thomas List

Master Thesis 30 hp

Dentistry

February 2020

Malmö University

Faculty of Odontology

205 06 Malmö

Abstract

Objectives: Temporomandibular disorders (TMD) are the most common causes of chronic

orofacial pain and affects both psychological and social aspects of life. The aim was to investigate the possible relationship between TMD, catastrophizing, kinesiophobia and physical symptoms.

Methods: The study was based on 401 participants (333 women, 86 men, mean age 45.8) in the

TMJ (temporomandibular joint) Impact Project recruited at University of Minnesota, University of Washington and University of Buffalo 2003–2006. Of these, 218 had TMD pain, 111 non-painful TMD, 63 pain-free controls and data was missing for 9 individuals. Participants were diagnosed in accordance with the Research Diagnostic Criteria for TMD, including a clinical and radiographic examination (axis I) and a psychosocial assessment (axis II). The possible correlations between TMD, catastrophizing, kinesiophobia and physical symptoms were evaluated with Pain

Catastrophizing Scale, Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia, Patient Health Questionnaire, together with Areas of Pain.

Results: Compared to controls, participants with TMD pain showed a higher degree of

kinesiophobia, somatic symptoms, and areas of pain and participants with non-painful TMD showed higher degree of kinesiophobia. There was a positive, low-moderate correlation between catastrophizing and kinesiophobia for participants with TMD pain (r = 0.37, p <0.001) and non-painful TMD (r = 0.53, p <0.001).

Conclusions: The results suggest an association between catastrophizing and kinesiophobia in

individuals with TMD regardless of presence of pain. The findings suggest that evaluating kinesiophobia and catastrophizing, as well as widespread pain and multiple non-TMD symptoms can be useful in the assessment of patients with TMD.

Sammanfattning

Objektiv: Temporomandibulär dysfunktion (TMD) utgör vanligaste formen av kronisk orofacial

smärta. Kronisk TMD har negativ inverkan på det psykosociala tillståndet vilket påverkar livskvaliteten. Syftet var att undersöka samband mellan TMD, katastrofiering, kinesofobi och fysiska symtom.

Material och metod: Studien baserades på 401 individer (333 kvinnor, 86 män, medelålder 45,8)

som deltog i TMJ (temporomandibular joint) Impact Project. Datainsamlingen utfördes på University of Minnesota, University of Washington och University of Buffalo (2003–2006). 218 individer hade smärtsam TMD, 111 icke-smärtsam TMD, 63 smärtfria kontroller och data saknades för 9 individer. TMD diagnosticerades enligt Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (RDC/TMD) som inkluderar en klinisk och radiologisk undersökning (axel I) och en psykosocial utvärdering (axel II). För att undersöka en potentiell korrelation mellan TMD, katastrofiering, kinesofobi och fysiska symptom användes följande instrument: Pain Catastrophizing Scale, Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia, The Patient Health Questionnaire och Areas of Pain.

Resultat: Deltagare med smärtsam TMD uppvisade högre grad av kinesofobi, somatisering och

fysiska symtom jämfört med kontroller. Deltagare med smärtfri TMD uppvisade högre grad av kinesofobi jämfört med kontroller. En låg till måttligt positiv korrelation sågs mellan

katastrofiering och kinesofobi hos deltagare med smärtsam TMD (r = 0,37 p < 0,001) och smärtfri TMD (r = 0,53 p < 0,001).

Konklusion: Resultaten uppvisar samband mellan katastrofiering och kinesofobi hos patienter

med TMD oberoende av smärtförekomst. Överlag föreslår resultaten att utvärderingen av kinesofobi och katastrofiering, utspridd smärta och multipla icke-TMD relaterade symtom kan vara av klinisk vikt vid utvärderingen av patienter med TMD.

Table of Contents

Abstract ... 2

Sammanfattning ... 3

Introduction ... 5

Temporomandibular disorders ... 5

Diagnostic and psychosocial assessment ... 5

Painful comorbidity ... 6

Catastrophizing ... 7

Kinesiophobia (fear of movement) ... 8

Physical Symptoms ... 8

Treatment of TMD ... 9

Aims of the study ... 9

Methods... 9

Population and design of study ... 9

Inclusion and exclusion criteria ... 10

Questionnaires ... 10 Statistics ... 11 Results ... 11 Discussion ... 16 Conclusion ... 18 Acknowledgements ... 18 References ... 19

Appendix 1: Inclusion and exclusion criteria ... 21

Appendix 2: Pain Catastrophizing Scale ... 23

Appendix 3: Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia ... 24

Appendix 4: Areas of Pain ... 25

Appendix 5: Physical Health Questionnaire-15 ... 26

5

Introduction

Temporomandibular disorders

Temporomandibular disorders, TMD, are a set of conditions involving a combination of subjective symptoms and clinical findings related to the muscles of mastication and/or the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). Examples of common temporomandibular dysfunctions are pain and tenderness in the facial- and temporomandibular region, limited jaw-opening and clicking or popping sounds in conjunction with mandibular movements.

Epidemiological studies suggest that toothache and pain from the muscles of mastication and the TMJ are the most common occurring types of pain in the face- and mouth region (1). TMD-pain affects 10–15 % of the adult population and 4–7 % of adolescents. However, only half of these individuals seek treatment (2) and even fewer actually receive treatment (3). Pain caused by TMD is three-to-five-times more likely in care-seeking women than men (1). Chronic pain often leads to functional and psychosocial consequences for the affected

individual as cognitive, emotional, sensory and behavioral reaction patterns are affected which in turn maintains chronic pain and increases its severity (4). Many studies have found that psychosocial distress associated with depression, anxiety and stress often occurs in

combination with painful temporomandibular disorders (2,5,6).

The fact that TMD-pain is a multifactorial disease is reported in several studies (4,7) and there are several risk factors that are believed to predispose, trigger or prolong it. The etiology is complex and not completely understood, but several biological- and psychosocial risk factors of TMD have been identified (4). Examples of common risk factors including psychosocial factors, comorbidity, gender, trauma and overload have been addressed in the prospective OPPERA (Orofacial Pain: Prospective Evaluation and Risk Assessment) study (8). It is important to note that less than 15 % of TMD-pain is associated with occlusal factors, the remaining 85 % depend on other factors (1).

Diagnostic and psychosocial assessment

TMD is an umbrella term for several different diagnoses, which can be divided into three subgroups: muscle- (myofascial pain), disc- (disc displacement) and joint related (arthralgia and arthritis) issues (1). TMD is diagnosed by a combination of patient history, examination of familiar pain during jaw movements together with palpation of jaw muscles and the TMJ’s. The Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (RDC/TMD) has been the most cited classification system in TMD research since it was published in 1992 (9) and at that time also introduced psychosocial assessment as a complement to the clinical

examination. However, shortcomings with the RDC/TMD system have been identified, e.g. uncertainty in the palpation of certain areas and the diagnosis of joint displacement. Therefore, in 2014 a revised version, the Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular disorders

6

a structured manner and improved reliability. To receive a DC/TMD-diagnosis, the patient must show a well-defined combination of subjective symptoms and clinical findings.

The diagnostic assessment in DC/TMD involves an evaluation of the clinical condition, Axis I, which includes palpation of the jaw muscles and joints, registration of pain and tenderness in the facial- and temporomandibular region, limited jaw-opening and clicking or popping sounds in conjunction with mandibular movements. The second part of the DC/TMD includes a psychosocial evaluation, Axis II, with the help of validated instruments (2). The diagnosis together with the evaluation of a patient from a biopsychosocial point of view is important in the assessment of prognosis and hence choosing the right form of therapy (2,4). The

development of Axis II instruments started with the introduction of RDC/TMD and was further refined in the revised DC/TMD. The instruments were chosen based on availability of valid instruments that can assess pain, jaw function, depression, anxiety, somatization, comorbidity and daily function. The complete axis II assessment in DC/TMD includes the Graded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS), Jaw Functional Limitations Scale (JFLS), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 9), Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15), Oral Behavior Checklist and a Pain Drawing with Areas of Pain (AOP) (10). These

instruments were initially included in Axis II because they were considered clinically important markers for detecting psychosocial dysregulation relevant to pain conditions by contributing to pain and suffering, affecting expected responses to conventional treatment (11). Other domains that have been suggested to be of value in the assessment of a patient from a holistic point of view include instruments to evaluate sleep, stress, catastrophizing and kinesiophobia i.e. fear of movement.

As part of the development and evaluation of RDC/TMD The Validation project (5) was

conducted between August 2003 and September 2006at University of Minnesota, University of Washington and University of Buffalo. A total of 614 participants with TMD and 91 healthy controls were recruited. All participants underwent a thorough clinical examination and a radiographic investigation of the TMJs in order to validate the RDC/TMD criteria. Participants also completed 13 questionnaires to obtain information about demographics, chronic pain, pain intensity and psychosocial health. In the follow-up project, TMJ Impact Project (12)conducted eight years later, a total of 401 subjects who were considered representative of the initial 614 were re-examined. The longitudinal study helped evaluate many of the collected diagnostic parameters, and as a result radiographic imaging is no longer performed routinely as it has minor diagnostic value for Axis I diagnostics. At present not all 13 questionnaires used in the TMJ Impact Project are included in DC/TMD diagnostics.

Painful comorbidity

It is a known fact that patients who suffer from chronic pain e.g. orofacial pain, in which temporomandibular pain is the most common, often suffer from headaches and pain in other regions such as neck, shoulders and/or lower back simultaneously (13). To investigate whether an individual is suffering from pain in several areas of the body, a body diagram is usually administered for patient self-evaluation. Validating instruments using body diagrams are considered to have excellent reliability and validity (14). The medical term for when a person is diagnosed with at least two conditions at the same time is comorbidity. Chronic pain often has negative effects on physical, mental and cognitive health hence leading to psychological

7

comorbidity. A population based cross-sectional study involving 189 977 individuals reported that 83 % of those who suffer from TMD-related pain also suffered from pain in another area of the body whilst 59 % of all the study-participants reported the presence of at least two comorbid conditions simultaneously. The study also found that the prevalence of multiple chronic pain conditions is higher in individuals with low socioeconomic status and more common in women rather than men (15).

Several cross-sectional and case-control studies have shown that people with TMD-related pain are 1,5–8,8 times more likely to get headaches in comparison with people who do not suffer from any TMD symptoms. Women stand a higher risk of having pain associated with TMD or headache/migraine. There is a linear correlation between the likelihood of

developing headache and the number of TMD symptoms that a patient has, the more symptoms the higher the risk of developing a headache (13).

Fibromyalgia is characterized by chronic pain and pain all over the body in combination with cognitive dysfunctions such as difficulty sleeping, fatigue and other somatic symptoms. Studies have found that 7–13 % of TMD patients also suffer from fibromyalgia and most of the

patients who suffer from fibromyalgia have TMD pain (13,16). A number of studies have suggested that patients with TMD-related pain also suffer from psychological comorbidity in the form of depression, anxiety, anxiety disorders, emotional suffering, stress, somatic

awareness, catastrophizing and kinesiophobia (13,17)

Catastrophizing

Pain catastrophizing is defined as an excessive or amplified cognitive response to self- experienced threats caused by painful sensations, which in turn affects the overall painful experience (18). Negative thoughts about pain or negative information about a disease may theoretically lead to a catastrophizing response in which the patient imagines the worst possible outcome, which in turn leads to fear and avoidance that strengthens the original negative thought. This vicious cycle that ultimately strengthens the negative attitude is described in The Fear-Avoidance model (FAM) (19).

Several studies (19–23) suggest that catastrophizing predominantly occurs in patients who suffer from chronic pain and have received inadequate pain relief. Results from a number of studies based on observation and treatment have found that catastrophic behaviors plays a big role in the prognostics of developing chronic pain (20). It has been suggested that patients who do not suffer from catastrophizing and hence avoid fear-evoking thoughts, stand a higher chance of confronting their problems and have a more solution-oriented cognitive pattern and behavior (19). The amount of catastrophic thoughts may vary on a daily basis depending on the severity of symptoms and other pain related factors. Little is currently known about the

symptom-related, stress-related or psychosocial factors that activate and trigger the catastrophizing thoughts (20).

In 1995 a validated instrument called The Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) was developed which assesses the three different dimensions of catastrophizing in relation to pain: rumination,

amplification and helplessness (20). PCS has been shown to have good validity and reliability and is considered to have a moderate to excellent quality. PCS is currently not included in modern

8

DC/TMD axis II diagnostics but is widely used in other areas of clinical research as

catastrophizing has been shown to predict future pain and distress responses. In theory, deepened knowledge about catastrophizing may provide important information relevant for elaboration or revision of psychosocial models of chronic pain (20).

Kinesiophobia (fear of movement)

The term kinesiophobia refers to an excessive, irrational and restrictive fear of movement as a result of vulnerability related to painful injuries in the past (24). Individuals who suffer from kinesiophobia have developed a particular anxiousness and concern towards reliving painful experiences and thereby avoid everything that might provoke it. Kinesiophobia has been highlighted as an important component in chronic pain (25,26) hence why it is of significant clinical value when treating and evaluating TMD patients (24). According to FAM,

catastrophizing has been suggested to predispose individuals who develop kinesiophobia, which can lead to impaired function (26). The FAM seems to be of particular relevance for patients with musculoskeletal diseases, and the severity of fear of movement is often assessed with the help of The Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK) (27) in these patients. The TSK-TMD questionnaire has shown good validity and reliability. It is not always the painful component in TMD and musculoskeletal disease that evokes kinesiophobia; other symptoms such as non-painful sounds from the temporomandibular joint, acute mandibular dislocation (luxation) or catching of the jaw may also give rise to kinesiophobia. However, a correlation between

kinesiophobia and non-painful TMD can only be noted when patients avoid movement because they either dislike or are embarrassed of catching/locking of the jaw or the noises associated with it (27). No study has demonstrated that painful TMD can trigger kinesiophobia even though kinesiophobia is often noted in chronic pain conditions.

Physical Symptoms

A symptom is defined as “a self-reported bodily sensation or mental experience that is perceived by a person as a change from normal health” (28). Symptoms may be an indication of disease or impairment in physiological function, however they are not always solely related to a specific pathology. Physical symptoms such as nausea, insomnia, headaches, dizziness, back pain, abdominal pain etc. can sometimes be related to psychological distress. An example of this is a condition called somatization, a phenomenon of converting psychological distress into physical symptoms. Somatization is seen in primary care and is connected to substantial functional impairment and increased healthcare utilization (29). Somatic symptoms affecting functionality are common, they often result in disability and patients often feel misunderstood, thus losing faith in the healthcare system, which complicates treatment outcome and results in more costly treatment alternatives (30). Physical symptoms are evaluated using Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-15) which is a reliable measure that has been used in multiple healthcare related studies and the validity is well-established (29).

9

Treatment of TMD

It is often difficult to prescribe cause-oriented treatment for TMD as causal factors are not easily identified, hence treatment is usually targeted towards alleviating symptoms and reestablishing normal function (1). The Swedish National Guidelines for Adult Dental Care primarily suggests minimally invasive, reversible treatment for TMD such as counseling, behavioral management, physical therapy and occlusal appliances. Other treatments for example postural training, pharmacological treatment with analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs, acupuncture, surgical treatment and occlusal adjustment are also listed, however, these have not been proven as effective. Non-steroidal-anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) have proven to have better effect on treating TMD in shorter periods, when combined with physical therapy/jaw-stretching and/or occlusal appliances (31). TMD pain is transient in most patients hence why it often has a good prognosis, only a few individuals develop a state of prolonged, chronic pain (1). Studies have stressed the importance of customizing treatment for every patient to obtain optimal treatment outcome (31).

Aims of the study

Catastrophizing, kinesiophobia, comorbidity and physical symptoms have all been identified as risk factors for chronic pain (7), which suggests that evaluating these areas could be of clinical importance. It is not known however, whether there is a correlation between TMD,

catastrophizing, kinesiophobia and physical symptoms. To advocate inclusion of additional questionnaires to DC/TMD diagnostics, further research to assess possible correlations between risk factors of TMD is suggested. The data from The Validation project (5) and the TMJ Impact Project (12) have been made available to researchers at the Department of Orofacial Pain and Jaw Function at Malmö University, Sweden as part of a longstanding international collaboration. The aim of the study was to investigate whether there is a correlation between TMD,

catastrophizing, kinesiophobia and physical symptoms and whether a questionnaire evaluating kinesiophobia and catastrophizing can be recommended when assessing patients with TMD, as kinesiophobia and catastrophizing are currently not included in Axis II assessment.

Our hypothesis is that there is a correlation between TMD, catastrophizing, kinesiophobia and physical symptoms.

Methods

Population and design of study

The TMJ Impact Project (12) is a follow-up study of the subjects that participated in The

Validation Project (5) that was conducted eight years before. The recruitment of participants was conducted at University of Minnesota, University of Washington and University of Buffalo between August 2003 and September 2006 through advertisements or referral and aimed to include a variety of TMD-symptoms. The subjects in The Validation Project were initially

comprised of 724 participants aged 18–70, 19 were excluded because five of them were not able to fit in any of the test-groups while the remaining 14 had comorbid conditions. They underwent a thorough clinical examination and radiographic investigation of the TMJs. They also answered

10

several questionnaires to obtain information about demographics, chronic pain, pain intensity and psychosocial health. Out of 724 participants, 19 were excluded because five of them were not able no fit in any test-groups while the remaining 14 had comorbid conditions. A total of 614

participants with TMD and 91 healthy controls were recruited. The follow-up study, TMJ Impact Project, only permitted 400 subjects due to financial restrictions although 620 individuals had the potential to be recalled. A total of 401 subjects who were considered representative of the initial 724 from the three universities were signed for the follow-up study. The results from the initial examination were used to compare patients who received a follow-up in The TMJ Impact Project (n = 401) with those who were not recalled (n = 323) in order to further assess hypothesis

regarding jaw pain, jaw function and disability.

The Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol and all subjects provided informed consent. Participants were free to change their mind about participating and could also refuse radiographic imaging. Participants were randomly selected and economically compensated. All research was conducted using validated and reliable instruments, which minimized the risk of undergoing unnecessary examination.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Participants were included if they reported or presented with at least one of the three cardinal signs or symptoms of TMD: jaw pain, limited mouth opening or TMJ noise. Participants who did not have any of these three TMD symptoms were instead included in the healthy control group. Participants who have never shown signs of TMD were included as supercontrols. A detailed list of the inclusion and exclusion criteria is presented in Appendix 1.

Questionnaires

The Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) is an instrument consisting of 13 questions (see Appendix 2) about thoughts or feelings that arise when you experience pain. The variables are ranked in an ordinal scale with five different answer options where 0 means “not at all” and five “all the time”. One can obtain a total of 0–52 points by answering all questions (20).

Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK) is a questionnaire that was initially designed to evaluate the degree of fear of movement in chronic pain conditions such as lumbar spine disorders (see Appendix 3). The questionnaire was then adapted for TMD

patients, which resulted in a form consisting of 18 questions that concern fear of injury and relapse related to jaw movement. By answering all questions, the participants can obtain a maximum of four points per question and a total of 18–72 points (27).

Areas of Pain (AOP) is a form illustrating eleven body parts where participants must mark the areas where pain is present (see appendix 4). Participants can obtain between zero (no pain) and eleven (pain from all areas) points. In combination with

questionnaires evaluating psychological symptoms, a better understanding of disability and pain intensity can be obtained hence why AOP is included in Axis II diagnostics (14).

11

Patient Health Questionnaire 15 (PHQ-15) is one of few questionnaires for identifying and monitoring somatic symptoms. The PHQ-15 is derived from the full PHQ and consists of 15 questions about somatic symptoms or symptom clusters that comprise 90 % of the most common physical complaints, with three possible answers. When asked about physical symptoms such as “stomach pain” one can answer “not bothered at all” which equals zero points, “bothered a little” which equals one point or “bothered a lot” which equals two points. By answering all questions, the participants may obtain a maximum of two points per question and a total of 0–30 points (29).

Statistics

Results from the three different groups: No pain (healthy controls), TMD without pain and TMD with pain were used to investigate the correlations between TMD, catastrophizing, kinesiophobia and physical symptoms. The significance level was set at p < 0.05. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine whether there were statistically

significant differences between the means of three independent groups. Tukey’s test was used to locate specific differences between these groups. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine differences in age between groups and a chi-square (χ²) test was used to determine differences in sex distribution between TMD-groups and controls. A correlation analysis was conveyed using Pearson correlation coefficient to access correlation between TMD, catastrophizing, kinesiophobia and physical symptoms, an r-value between -1 to 1 is extracted and indicates the level of covariation.

Results

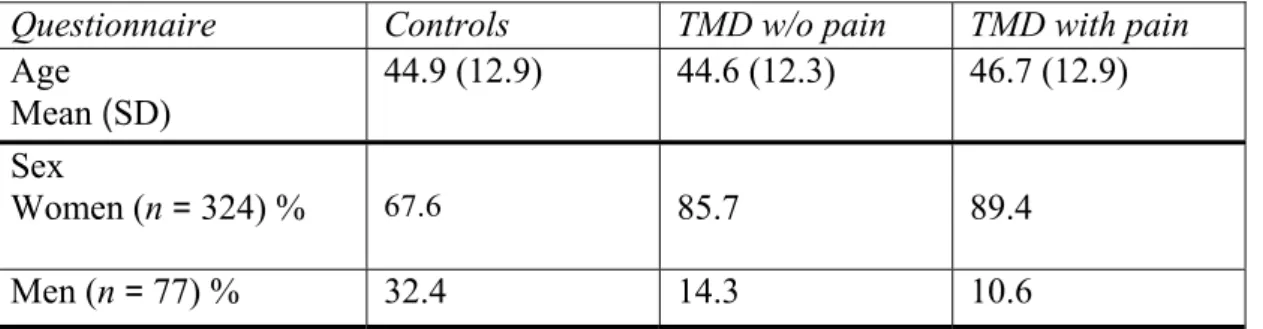

There was no significant difference in age (ANOVA) between groups (p = 0.323). However, a significant difference in sex distribution (χ²-test) existed (p < 0.001) where women were overrepresented in the TMD-groups (Table 1).

Questionnaire Controls TMD w/o pain TMD with pain

Age Mean (SD) 44.9 (12.9) 44.6 (12.3) 46.7 (12.9) Sex Women (n = 324) % 67.6 85.7 89.4 Men (n = 77) % 32.4 14.3 10.6

Table 1: Age and sex distribution for the three groups; controls (n = 111), TMD without pain (n = 63) and TMD with pain (n = 218).

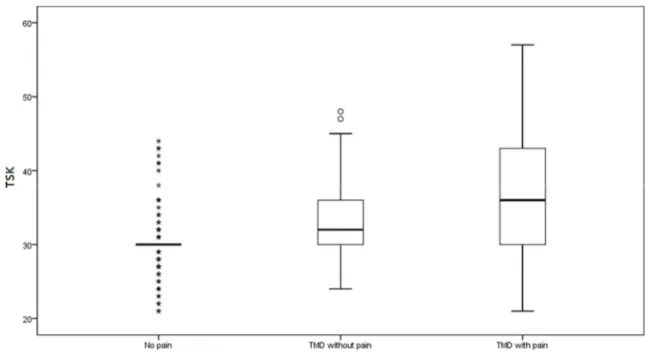

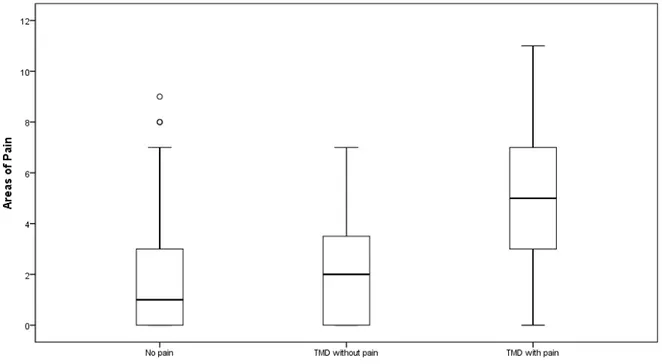

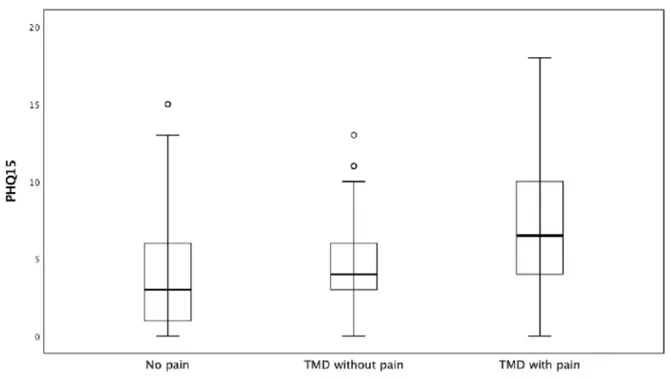

There was no significant difference between groups regarding PCS (Fig. 1) although the group with painful TMD showed higher mean scores for TSK, AOP and PHQ-15 in

12

comparison with controls and participants with painless TMD (Figure 2,3 and Table 2).

Figure 1: Box plot for the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS, 0–52 points) for the three groups; No pain (controls, n = 111), TMD without pain (n = 63) and TMD with pain (n = 218). Small circles and stars indicate mild and extreme outliers.

Figure 2: box plot for the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK, 18–72 points) for the three groups; No pain (controls, n = 111), TMD without pain (n = 63) and TMD with pain (n = 218). Small circles and stars indicate mild and extreme outliers.

13

Figure 3: Box plot for Areas of Pain (AOP, 0–11 points) for the three groups; No pain (controls, n = 111), TMD without pain (n = 63) and TMD with pain (n = 218). Small circles indicate mild outliers.

Questionnaire Controls TMD w/o pain TMD with pain p value

PCS Mean (SD) 7.0 (8.7) 7.2 (9.7) 8.4 (8.8) 0.316 TSK Mean (SD) 30.3 (4.2) 32.8 (5.5) 36.9 (8.3) < 0.001 Areas of pain Mean (SD) 1.8 (2.3) 2.1 (2.2) 5.2 (2.8) < 0.001 PHQ-15 Mean (SD) 4.0 (3.6) 4.6 (3.1) 7.4 (3.9) < 0.001

Table 2: Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS), Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK), Areas of Pain (AOP), and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-15) for the three groups; controls (n = 111), TMD without pain (n = 63) and TMD with pain (n = 218).

14

Figure 4: Box plot for the Patient Health Questionnaire 15 (PHQ-15, 0–30 points) for the three groups; No pain (controls, n = 111), TMD without pain (n = 63) and TMD with pain (n = 218). Small circles indicate mild outliers.

There was a moderate correlation (r = 0.53, p < 0.001) between PCS and TSK in participants with painless TMD (Fig. 5). TSK was chosen to be the dependent variable, as we believe that catastrophizing leads to increased kinesiophobia.

Figure 5: The correlation between the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS, 0–52 points) and the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK, 18–72 points) for the TMD group without pain (n = 63).

15

There was a low correlation (r = 0.37 p < 0.001) between PCS and TSK in participants with painful TMD (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: The correlation between the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS, 0–52 points) and the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK, 18–72 points) for the TMD group with pain (n = 218).

The correlation was low and insignificant (r = 0.17 p = 0.18) between PHQ-15 and PCS in participants with painless TMD. PHQ-15 was chosen to be the dependent variable, as we believe that physical symptoms lead to increased catastrophizing (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: The correlation between the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS, 0–52 points) and the Patient Health Questionnaire 15 (PHQ-15, 0–30 points) for the TMD group without pain (n = 63).

16

The correlation was low to moderate and significant (r = 0.46 p < 0.001) between PHQ-15 and PCS in participants with painful TMD (Fig. 8).

Figure 8: The correlation between the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS, 0–52 points) and the Patient Health Questionnaire 15 (PHQ-15, 0–30 points) for the TMD group with pain (n = 218).

Discussion

The main finding in this study was that participants with painful TMD reported higher levels of kinesiophobia, pain-comorbidity and physical symptoms compared to controls and participants with pain-free TMD. This aligns with the results presented in another case-control study comprising 1633 controls and 185 TMD patients, claiming that patients with TMD related pain have a higher risk of reporting anxiety, depression, stress, somatic awareness, hostility, neuroticism and catastrophizing in comparison with controls (8). However, in our study there was no difference in catastrophizing between controls and TMD groups. Controls in our study, who did not suffer from TMD or any kind of pain, showed the lowest mean scores in the other areas of examination: kinesiophobia, pain- comorbidity and physical symptoms. Not only did our study include controls, participants who did not suffer from TMD at the examination, it also included supercontrols,

participants who had no lifetime history of TMD symptoms. It was not possible however in the time frame of the present study to include a separate analysis of supercontrols.

Participants with painful TMD showed more physical symptoms (PHQ-15) compared to controls and participants with painless TMD, i.e. clicking noises of the jaw. This is in line with suggestions that chronic pain conditions are related to general physical symptoms (29). Participants with painful TMD also showed the highest number of painful

17

These findings coincide with results from two other cross-sectional and case-control studies (13,15).

The levels of catastrophizing in our study are lower for participants with painful TMD in comparison with other studies (8,32) but mean values of controls are similar. The reason for no significant differences between controls and TMD groups may be related to that the painful TMD group had less severe symptoms, which might indicate that participants in our study were not representative of the greater mass of patients with painful TMD. Participants with painful TMD showed higher levels of kinesiophobia in comparison with controls, these results are statistically significant and coincide with one conducted study investigating the correlation between TMD and kinesiophobia (24). Participants with painless TMD showed higher levels of kinesiophobia compared with controls, which might be related to the observation in a study suggesting that clicking noises may cause embarrassment in patients and thereby avoidance of movement (27).

When analyzing the correlation between catastrophizing and kinesiophobia, a positive correlation was seen for both TMD groups. The group with painless TMD showed a higher albeit moderate correlation compared to painful TMD. These findings suggest that catching of the jaw and clicking noises may contribute to higher levels of kinesiophobia, which in turn is related to higher levels of catastrophizing. Because no relation between TMD and catastrophizing was confirmed, it is suggested that catastrophizing may have less value on its own but is linked to kinesiophobia, where higher levels of catastrophizing might

contribute to higher levels of kinesiophobia. This relationship may be bidirectional, thereby affecting assessment and management of these patients. In clinical terms as dentists we do not treat catastrophizing in order to alleviate kinesiophobia since it requires knowledge in cognitive behavioral therapy, which we do not possess. However, we may target

kinesiophobia by administering physical therapy, which in turn may have a positive influence on the level of catastrophizing.

The correlation between catastrophizing and general physical symptoms was moderate for participants with painful TMD in comparison with the low correlation found for painless TMD. These findings indicate that patients with painful TMD and multiple physical symptoms such as nausea, stomach pain and dizziness show higher levels of

catastrophizing. Studies have also shown that physical symptoms can be a predictor for the development of chronic painful disorders and that catastrophizing affect prognosis and outcome of treatment.

Our study is based on data from a longitudinal follow-up study. Longitudinal studies are often designed to evaluate risk factors by enabling comparison of results before and after. Because the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia was not developed at the time the study was initiated (2003), we cannot benefit from this study design since relevant baseline data in the primary examination does not exist. The results were based on a group of 401

randomized individuals from the baseline population consisting of 724 subjects originating from three different geographical areas in the U.S. The advantages of having a randomized sample is minimizing the risk of sampling bias i.e. lessen the influence of coincidence on differences in groups. Despite the broad spectrum of ages (18–70 years) included in our study, no differences within and/or between different age groups existed, we can therefore presume that there is no age bias in the presented results. There is however a significant difference in gender representation, whereby women are overrepresented in the TMD

18

groups. Although TMD, and other chronic pain conditions, are more common in women, the fact that women were generally overrepresented in the present study, especially in the TMD groups, means that it is difficult to assess the possible influence of gender bias. The data in the present study was collated in The Validation Project which followed ethical recruitment conditions such as random selection of participants, obtained consent and participants were free to change their mind about participating and could also refuse radiographic imaging. Participants were furthermore economically compensated. All research was conducted using validated and reliable instruments, which minimized the risk of undergoing unnecessary examination. Eric Schiffman conducted an extensive study including a variety of TMD symptoms and diagnoses. In a broader perspective the study enabled further correlative research whereby we can examine the relationship between i.e. TMD and catastrophizing and thereby deepen our knowledge in a very small field with little to no conducted research which in turn might lead to revision of Axis II instruments. The longitudinal study design helped evaluate many of the collected diagnostic parameters, and radiographic imaging is no longer commonly performed as such procedures showed minor diagnostic value for Axis I diagnostics. Increased economic efficacy moreover leads to societal gain because patients with high treatment need are identified and prioritized.

Taken together, our results indicate that including kinesiophobia and catastrophizing as another variable in Axis II assessment can be worthwhile as the evident correlations showed that kinesiophobia and catastrophizing are co-dependent. Approximately 20 % of patients suffering from acute TMD pain developed chronic pain (33) and kinesiophobia has been highlighted as an important component in chronic pain (25,26), which is yet another reason to include this questionnaire.

This study is unprecedented in investigating correlations between three integral

components: catastrophizing, kinesiophobia and physical symptoms in association with TMD. Lack of published research in this field limits our potential to compare results. Although our research is extensive, one study alone is not enough to decide on including another questionnaire in Axis II diagnostics. Our study lays the foundation for further investigation.

Conclusion

The results suggest an association between catastrophizing and fear of movement in individuals with TMD regardless of presence of pain. The overall findings suggest that evaluating for fear of movement and catastrophizing, as well as widespread pain and multiple non-TMD symptoms can be useful in the assessment of patients with TMD.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Eric Schiffman for giving us access to The Validation Project database and Per-Erik Isberg for helping us with statistical analytics.

19

References

1. List T, Tegelberg A, Lundeberg T, Ohrbach R. Smartlindring i ansikte och huvud ur bettfysiologiskt perspektiv. 1999.

2. List T, Ekberg E, Ernberg M, Svensson P, Alstergren P. Diagnostik av käksmärta. Tandlakartidningen. 2015;(3):64–72.

3. Lovgren A, Karlsson Wirebring L, Haggman-Henrikson B, Wanman A. Decision-making in dentistry related to temporomandibular disorders: a 5-yr follow-up study. Eur J Oral Sci. 2018 Dec;126(6):493–9.

4. List T, Jensen RH. Temporomandibular disorders: Old ideas and new concepts. Cephalalgia. 2017 Jun;37(7):692–704.

5. Schiffman EL, Truelove EL, Ohrbach R, Anderson GC, John MT, List T, et al. The Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders. I: overview and methodology for assessment of validity. J Orofac Pain. 2010;24(1):7–24.

6. List T, Dworkin SF. Comparing TMD diagnoses and clinical findings at Swedish and US TMD centers using research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders. J Orofac Pain. 1996;10(3):240–53.

7. Slade GD, Ohrbach R, Greenspan JD, Fillingim RB, Bair E, Sanders AE, et al. Painful Temporomandibular Disorder: Decade of Discovery from OPPERA Studies. J Dent Res. 2016 Sep;95(10):1084–92.

8. Fillingim RB, Ohrbach R, Greenspan JD, Knott C, Dubner R, Bair E, et al. Potential psychosocial risk factors for chronic TMD: descriptive data and empirically identified domains from the OPPERA case-control study. J Pain. 2011 Nov;12(11 Suppl):T46-60. 9. Dworkin SF, LeResche L. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular

disorders: review, criteria, examinations and specifications, critique. J Craniomandib Disord. 1992;6(4):301–55.

10. Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, Truelove E, Look J, Anderson G, Goulet JP, et al. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network* and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Groupdagger. J oral facial pain headache.

2014;28(1):6–27.

11. Ohrbach R, Turner JA, Sherman JJ, Mancl LA, Truelove EL, Schiffman EL, et al. The Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders. IV: evaluation of psychometric properties of the Axis II measures. J Orofac Pain. 2010;24(1):48–62. 12. Schiffman EL, Ahmad M, Hollender L, Kartha K, Ohrbach R, Truelove EL, et al.

Longitudinal Stability of Common TMJ Structural Disorders. J Dent Res. 2017 Mar;96(3):270–6.

13. Velly A, List T, Lobbezoo F. Comorbid pain and psychological conditions in patients with orofacial pain. In: Sessle BJ, editor. Orofacial Pain: Recent Advances in

Assessment, Management, and Understanding of Mechanisms. 2014. p. 53–73. 14. Rhon DI, Lentz TA, George SZ. Unique Contributions of Body Diagram Scores and

Psychosocial Factors to Pain Intensity and Disability in Patients With Musculoskeletal Pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017 Feb;47(2):88–96.

15. Plesh O, Adams SH, Gansky SA. Temporomandibular joint and muscle disorder-type pain and comorbid pains in a national US sample. J Orofac Pain. 2011;25(3):190–8. 16. Suvinen TI, Kemppainen P, Le Bell Y, Kauko T, Forssell H. Assessment of Pain

Drawings and Self-Reported Comorbid Pains as Part of the Biopsychosocial Profiling of Temporomandibular Disorder Pain Patients. J oral facial pain headache.

2016;30(4):287–95.

20

Management of chronic orofacial pain: a survey of general dentists in german university hospitals. Pain Med. 2010 Mar;11(3):416–24.

18. Sullivan MJ, Lynch ME, Clark AJ. Dimensions of catastrophict thinking associated with pain experience and diasability in patients with neuropathic pain conditions. Pain. 2005;113:310–5.

19. Wertli MM, Eugster R, Held U, Steurer J, Kofmehl R, Weiser S. Catastrophizing-a prognostic factor for outcome in patients with low back pain: a systematic review. Spine J. 2014 Nov 1;14(11):2639–57.

20. Darnall BD, Sturgeon JA, Cook KF, Taub CJ, Roy A, Burns JW, et al. Development and Validation of a Daily Pain Catastrophizing Scale. J Pain. 2017 Sep;18(9):1139–49. 21. Picavet HS, Vlaeyen JW, Schouten JS. Pain catastrophizing and kinesiophobia:

predictors of chronic low back pain. Am J Epidemiol. 2002 Dec 1;156(11):1028–34. 22. Pavlin DJ, Sullivan MJ, Freund PR, Roesen K. Catastrophizing: a risk factor for

postsurgical pain. Clin J Pain. 2005;21(1):83–90.

23. Burns JW, Kubilus A, Bruehl S, Harden RN, Lofland K. Do changes in cognitive factors influence outcome following multidisciplinary treatment for chronic pain? A cross-lagged panel analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003 Feb;71(1):81–91.

24. He S, Wang J, Ji P. Validation of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia for

Temporomandibular Disorders (TSK-TMD) in patients with painful TMD. J Headache Pain. 2016 Dec;17(1):109.

25. Hapidou EG, O’Brien MA, Pierrynowski MR, de Las Heras E, Patel M, Patla T. Fear and Avoidance of Movement in People with Chronic Pain: Psychometric Properties of the 11-Item Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK-11). Physiother

CanadaPhysiotherapie Canada. 2012;64(3):235–41.

26. Gil-Martinez A, Navarro-Fernandez G, Mangas-Guijarro MA, Lara-Lara M, Lopez-Lopez A, Fernandez-Carnero J, et al. Comparison Between Chronic Migraine and Temporomandibular Disorders in Pain-Related Disability and Fear-Avoidance Behaviors. Pain Med. 2017;

27. Visscher CM, Ohrbach R, van Wijk AJ, Wilkosz M, Naeije M. The Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia for Temporomandibular Disorders (TSK-TMD). Pain. 2010

Sep;150(3):492–500.

28. Zijlema WL, Stolk RP, Lowe B, Rief W, White PD, Rosmalen JGM. How to assess common somatic symptoms in large-scale studies: a systematic review of

questionnaires. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74(6):459.

29. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(2):258–66. 30. Zijlema WL, Stolk RP, Lowe B, Rief W, White PD, Rosmalen JGM. How to assess

common somatic symptoms in large-scale studies: a systematic review of questionnaires. J Psychosom Res. 2013 Jun;74(6):459–68.

31. Wanman A, Ernberg M, List T. Orofacial smärta och käkfunktionsstörningar, riktlinjer för behandling. Tandlakartidningen. 2016;(3):58–67.

32. Kothari SF, Baad-Hansen L, Svensson P. Psychosocial Profiles of Temporomandibular Disorder Pain Patients: Proposal of a New Approach to Present Complex Data. J oral facial pain headache. 2017;31(3):199–209.

33. Sessle BJ. Advances in epidemiology, societal, and classification aspects of orofacial pain. Orofac Pain Recent Adv Assessment, Manag Underst Mech. 2014;

21

Appendix 1: Inclusion and exclusion criteria

INCLUSION CRITERIA

1 Inclusion criteria for TMD cases:

Participant reports or presents with at least 1 of the 3 cardinal signs or symptoms of TMD: jaw pain, limited mouth opening,

or TMJ noise.

2 Inclusion criteria for controls: I. History

A. No lifetime history of TMD symptoms (“supercontrols”) 1. Absence of TMJ noise, locking or catching of the jaw, and 2. Absence of pain in the jaw or the temporal area, and

3. Absence of headaches affected by jaw movement, function, or parafunction. B. Prior history of TMD symptoms (“controls”)

1. In the last 6 months, no history of TMD symptoms 2. Prior to 6 months ago:

a. No more than 5 isolated episodes of TMJ noise, with each episode lasting less than 1 day and not associated with jaw pain or limited mouth opening, and

b. No more than 1–2 isolated episodes of locking or catching of the jaw in the wide-open mouth position, and

c. No headaches in the temporal area affected by jaw movement, function, or parafunction.

II. Clinical examination

a. Any pain produced by procedures must be nonfamiliar, and

b. No TMJ clicking, popping, or snapping noises with more than 1 movement, and c. No coarse crepitus with any movement.

III. Imaging

a. TMJ MRI is negative for anterior disc displacement, and b. TMJ CT is negative for osteoarthrosis.

EXCLUSION CRITERIA FOR CASES AND CONTROLS I. History

a. Systemic rheumatic, neurologic/neuropathic, endocrine, or immune/autoimmune diseases or wide spread pain.

(Exception: participants with medical documentation of rheumatoid arthritis or fibromyalgia). b. Pathologic processes found on imaging including neoplasm (Exception: Disc displacements and osteoarthritis/

osteoarthrosis)

c. Radiation treatment to head and neck. d. TMJ surgery.

e. Trauma to jaw in the last 2 months (exclusion regardless of time: jaw trauma from auto accident).

22 f. Presence of non-TMD orofacial pain disorders. g. Pregnancy.

h. Unable to participate due to language barrier or mental/intellectual incompetence.

i. Use of narcotic pain medication, muscle relaxants or steroid therapy unless discontinued for 1 week prior to

examination.

23

24

25

26