What are the Justifications

Provided by the Consumers who

Don’t Look Back in Anger?

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration – Marketing NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Civilekonom AUTHORS: Ekstener, Jakob | Sveningsson, Eric TUTOR: Ots, Mart

JÖNKÖPING May 2020

Insights from the Swedish money laundering

scandal.

Abstract

Title: What are the Justifications Provided by the Consumers who Don’t Look Back in Anger? Insights from the Swedish money laundering scandal.

Authors: Jakob Ekstener and Eric Sveningsson

Tutor: Mart Ots

Date: 2020-05-15

Key Terms: ”Brand Transgressions” “Swedbank” “Money Laundering” “Consumer Behavior” “Consumer Justifications”

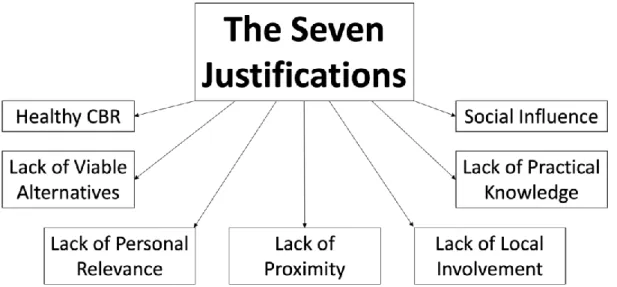

The purpose of this thesis is to use a real-world brand transgression example to extend the research and increase the knowledge around why people continue to consume brands they know have been involved in unethical organizational behavior. The research was of qualitative nature, and made use of semi-structured, in-depth interviews. Nine (9) consumers of the Swedish bank Swedbank, who was involved in a money laundering scandal, were interviewed around their justifications to sticking with the brand. The findings revealed seven (7) justifications to staying. Some of which could be linked to previous research, and some who by the authors’ were argued to be industry-specific. The thesis have implications for theory development, for managers, and for the society as a whole.

Acknowledgements

The authors of this thesis would like to take this opportunity to thank and express our gratitude to everyone who has contributed to the finalization of this report. Many people have assisted throughout the process, but there are a few to which we send a special thank you.

Firstly, we would like to thank all the participants in the study. A special thanks goes out to the nine participants who took time and resources from their free-time to be a part of this study. Without them this research would not have been possible.

Secondly, we send our gratitude to our tutor, Mart Ots. Mart has been a vital part of completing this thesis. Apart from providing us with useful feedback at the four seminars, he has always answered our questions and concerns in a quick and serious manner.

Thirdly, we want to notice the efforts put in from the other students in our seminar group. They have all provided us with feedback that has driven this thesis forward. Without their contributions, the report would not have become what it is today. We would also like to thank the other students at JIBS who, without any requirement to do so, have provided us with ideas and insightful comments.

Jönköping International Business School, Jönköping. May 15, 2020.

_______________________________ _______________________________

Table of contents

1 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION/BACKGROUND ... 1

1.1 BACKGROUND ... 1

1.2 SWEDBANK AND THE SWEDISH MONEY LAUNDERING SCANDAL ... 2

1.3 PROBLEM ... 4

1.3.1 Purpose ... 5

1.3.2 Research Question ... 5

1.4 DISPOSITION ... 6

1.5 DEFINITIONS /ABBREVIATIONS ... 6

2 CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW ... 7

2.1 BRANDS AND THE CONCEPT OF BRANDING ... 7

2.2 CONSUMER-BRAND RELATIONSHIPS ... 8

2.3 BANKING SECTOR BRANDS ... 8

2.4 BRAND TRANSGRESSIONS ... 9

2.5 CONSUMER RESPONSES TO BRAND TRANSGRESSIONS ... 10

2.6 ETHICAL DECISION-MAKING ... 14

2.6.1 Situational Contexts ... 15

2.6.2 Moral Awareness and Lack of Moral Awareness ... 17

2.6.3 Moral Consultation... 19 3 CHAPTER 3: METHODOLOGY ... 20 3.1 RESEARCH PHILOSOPHY ... 20 3.2 RESEARCH DESIGN ... 21 3.2.1 Research Approach... 21 3.2.2 Research Strategy ... 22 3.3 DATA COLLECTION ... 25 3.3.1 Sampling ... 25 3.3.2 Interview Guide ... 27

3.3.3 Collecting Empirical Data... 29

3.3.4 Protection of Personal Data – GDPR ... 30

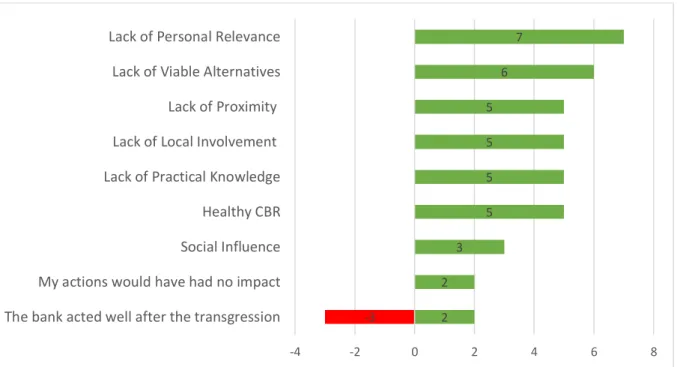

3.4 DATA ANALYSIS ... 31 3.5 TRUSTWORTHINESS OF DATA ... 32 3.5.1 Dependability... 32 3.5.2 Credibility ... 33 3.5.3 Transferability ... 34 3.5.4 Confirmability ... 34 4 CHAPTER 4: FINDINGS ... 35 4.1 HEALTHY CBR... 36

4.2 LACK OF VIABLE ALTERNATIVES ... 38

4.3 LACK OF PERSONAL RELEVANCE ... 39

4.4 LACK OF PROXIMITY ... 41

4.5 LACK OF LOCAL INVOLVEMENT ... 42

4.6 SOCIAL INFLUENCE ... 44

4.7 LACK OF PRACTICAL KNOWLEDGE ... 45

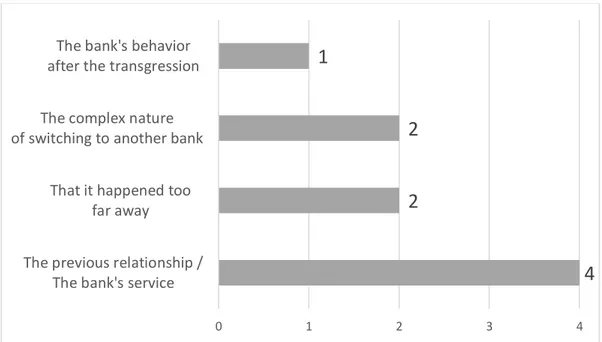

4.8 MOST IMPORTANT JUSTIFICATION ... 47

5 CHAPTER 5: ANALYSIS... 48

5.1 HEALTHY CBR... 48

5.2 LACK OF VIABLE ALTERNATIVES ... 50

5.3 LACK OF PERSONAL RELEVANCE ... 51

5.6 SOCIAL INFLUENCE ... 53

5.7 LACK OF PRACTICAL KNOWLEDGE ... 54

5.8 THE SEVEN JUSTIFICATIONS ... 55

6 CHAPTER 6: CONCLUSION & DISCUSSION ... 56

6.1 CONCLUSION ... 56

6.2 THEORETICAL IMPLICATIONS ... 56

6.3 MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS ... 57

6.4 ETHICAL/SOCIETAL IMPLICATIONS ... 59

6.5 LIMITATIONS ... 60

6.6 FUTURE RESEARCH ... 60

REFERENCES ... 62

APPENDICES ... 68

APPENDIX A–QUESTIONNAIRE SAMPLING (QUALTRICS) ... 68

1 Chapter 1: Introduction/Background

This first chapter of the thesis provides the reader with a background of the topic, as well as a background of the Swedish money laundering scandal revealed in 2019. The chapter then presents the problem formulation, the purpose, and the research question. Lastly, the thesis’ disposition as well as a list of definitions are provided.

1.1 Background

The world we live in today is filled with brands. Although not nearly all of these brands are loved, appreciated, or used by all, people can, similar to the love felt against one another, also feel love towards a brand (Albert, Merunka, & Valette-Florence, 2008; Batra, Ahuvia, & Bagozzi, 2012). Within marketing literature, love, and the positive aspects of consumer-brand relationships (CBR), have been the main focus. Reality is, up until the end of the last decade, the negative side have been neglected (Hegner, Fetscherin, & van Delzen, 2017). This despite the fact that psychological studies (Blum, 1997) have proven people to have an easier time remembering negative information and feelings, compared to positive ones. This highlights the importance of studying negative aspects of marketing and brand management as well, since consumers are likely to be deeply affected by negative emotions towards a brand.

In light of this, scholarly interest in negative aspects of CBR has increased lately, and a realization has been made that not all love stories have a happy ending. Just as one can be hurt by another person, a transgression from a brand can halt the ecstatic feelings one might have towards a brand. People can move from liking/loving a brand to disliking/hating a brand based upon the acts of the organization and the company behind it. Scholars have identified two main types of brand transgressions; performance-related, and values-related (Dutta & Pullig, 2011). However, a betrayal or a transgression from a brand does not always constitute the end of the relationship. For example, people are capable of forgiving other people (McCullough, Worthington Jr, & Rachal, 1997), and due to the similarities between person-person relationships and person-brand relationships (Fournier, 1998), the interest amongst marketing scholars for consumer responses following questionable organizational behavior has increased (see for example; Ahluwalia, Burnkrant, & Unnava, 2000; Fetscherin & Sampedro, 2019; Septianto, Tjiptono, & Kusumasondjaja, 2020; Tsarenko & Tojib, 2015).

However, little is known about the justifications behind the return to, or the continuous use of, brands that have been involved in ethical, moral, or legal transgressions (Fetscherin & Sampedro, 2019; Khamitov, Grégoire, & Suri, 2019). Within consumer behavior literature, it is agreed upon the fact that the intention of consumers to make ethical purchasing decisions is higher than their actual ethical purchasing behavior (Auger & Devinney, 2007; Carrigan & Attalla, 2001; Carrington, Neville, & Whitwell, 2010). This implies that even though the logical and rational decision would be to avoid unethical, and purchase ethical products and services, the reality tells a different story. The same phenomena can be spotted amongst consumers of a brand involved in a scandal. For example, after releasing millions of barrels of oil into the Mexican Gulf in 2010 and severely damaging wildlife, British Petroleum’s total sales in 2018 accounted to over $303 million (British Petroleum, 2019), Volkswagen Passenger Cars sold close to 4 million new cars in 2018 (Volkswagen, 2019) despite being caught tampering with emission tests, and the Swedish bank Swedbank, is still one of the largest banks in Sweden (Swedish Banker's Association, 2019) despite last year’s disclosure of them laundering billions of Swedish SEK. Money who had strong connections to organized crimes.

This brings the question of why consumers decide to support brands they know have acted in an unethical way, despite living in an age where information is easier than ever to find. A question this thesis aims to answer, or at least help to bring some clarity around. This will be done by a study around the last of the aforementioned examples, the money laundering scandal in Swedbank. Consumers to the bank will be interviewed in order to shed light on why they decided to act (or not to act) in the way they did. In order to further introduce the reader to the topic, the following section will contain a historical overview of Swedbank, and a summary of their involvement in the money laundering scandal and its consequences. Important to note, however, is that this thesis is not a case study around these events per se. Rather, it aims to use them as a basis to develop an understanding of consumers’ behaviors and intentions.

1.2 Swedbank and the Swedish Money Laundering Scandal

In 2018 and 2019 the Swedish bank Swedbank was accused of being involved in money laundering. After the turn of the millennium, the bank is estimated to have laundered billions of SEK (Bergsten & Lindahl, 2019). The Swedish Central Bank warns money laundering could be a threat to the balance within the Swedish economy. Something that would not only harm the Swedish economy, but also the trust for the banks (Carlström, 2019). The following sections

provide a historical overview of the bank Swedbank, and an explanation of their involvement in the money laundering scandal.

Swedbank has been in the Swedish bank market for centuries. Year 1820, the first bank that would later be called Swedbank was founded. The business evolved and during the early 1900’s it came to be a bank focusing on, and mostly giving credits, to smaller agricultures. When Swedish banking regulations were reworked in the late 1960’s, there was an opportunity for the bank to gain market shares. This since the new regulations allowed Swedbank to enter the commercial banking market as well. Something that gave results during the 1980’s where the current Swedbank was gaining great market shares, mainly within real estate, and the financing sector. During the 1990’s reorganizations were done due to the financial crisis, and in 1997 a fusion between Sparbanken Sverige and Föreningssparbanken occurred. Together a new bank named Föreningssparbanken was founded, with a customer base of approximately 5 million. Furthermore, in 2004 they acquired shares in Hansabank, something that was the beginning of the expansion into the Baltic market. In 2006, Föreningssparbanken changed name to the more international name Swedbank AB (Swedbank, 2020).

In 2019, one of the most extensive money laundering scandals in Swedish history was revealed. Journalists at Sveriges Television (SVT) got their hands on classified documents containing suspicious transactions made by Swedbank between 2007 to 2015. The material showed that over 40 billion SEK had been transferred through Swedbanks’ branch in the Baltics by 50 different customers. Furthermore, it was revealed that the people behind the transactions were not your average customer. For example, the Russian oligarch Iskander Makhmudov had one of the biggest contributions to the suspicious transactions (Bergsten & Lindahl, 2019). Following the disclosure, the bank’s stock fell with almost 14% (Mokhtari & Allen, 2019), the CEO was fired, and the chairman chose to step down from his position (Yttergren, 2019).

Later on, in March 2020, news came from the Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority, Finansinspektionen, where Swedbank got a warning, and were required to pay a sanction fee of 4 billion SEK. The sanction fee was rationalized by the extensive deficiencies in the work against money laundering, something that was found by the investigation executed by the Swedish and Estonian Financial Supervisory Authority (Finansinspektionen, 2020). Furthermore, the press release from the Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority showed that

enough actions or followed the regulations in order to prevent further money laundering (Finansinspektionen, 2020).

Swedbank was on the other hand not the only bank involved in the money laundering scandal. Danske Bank and Nordea are two other examples of banks that used Baltic subsidiaries to launder money. For Danske Bank it all started in 2007 when Sampo Bank was acquired, a bank operating in Estonia. The Estonian and non-residential customer portfolio included a variety of people who later came to use the bank with the purpose of laundering money up until 2015 (Bruun & Hjejle Advokatpartnerselskab, 2019). The other bank, Nordea, is believed to have laundered a total of 1.5 billion SEK (Lagerström, 2018), and they have been involved in money laundering cases before. In 2015 a fine was received due to the undermined work that had been done in order to prevent money laundering through the bank (Zeilon Lund, 2017).

Besides causing financial costs and downfalls in Swedbank’s and some of the other involved banks’ stock prices, the trust felt from Swedish consumers also seems to have been negatively affected. In a report made by Medieakademin together with Kantar SIFO measuring the level of trust for social institutes and companies in Sweden, it was revealed that the level of trust for the Swedish banks took a major hit in 2019. The banks moved from 9th position in 2018 to 17th in 2019 (Medieakademin, 2019). Furthermore, when looking at customer satisfaction for the specific bank involved, they tend to score the lowest when it comes to for example mortgages (Svenskt Kvalitetsindex, 2019). Some of the competitors to Swedbank also noticed an increase of consumers wanting to move their business away from Swedbank, into their bank instead (Tidningarnas Telegrambyrå, 2019). All this indicates that the trust for Swedbank, and also other Swedish banks, took a major hit when acts of money laundering were revealed. However, the banks still have a lot of business and a majority of their customers chose to stay as a consumer of the bank. This is where the purpose of this thesis stems from. Why is it that consumers choose to stay, despite knowing a brand transgression have occurred?

1.3 Problem

As now indicated, the practical notion that people continue to purchase and consume products and services from organizations involved in an ethical transgression is much confirmed. However, within the academic field very few explanations to why this is the case have been provided. Noteworthy exceptions being Tsarenko and Tojib (2015) who looked at how an

organization’s CSR activities affected the responses from consumers in the light of a transgression, Fetscherin and Sampedro (2019) who examined how the type, and severity of the transgression, impacted consumers’ willingness to forgive, and Dawar and Lei (2009) who argued that familiarity with a brand helps consumers to better asses a crisis or scandal. Furthermore, as of today, very few studies have focused on transgressions from brands within the financial sector (Khamitov et al., 2019). Therefore, to investigate this problem becomes highly important, and have the potential to drive the society as a whole forward. Consumers have a great opportunity to impact the market, as they are the ones paying for products and services. If people decide to not consume a specific brand due to something they have done, that brand will not survive for a long time. Hence, to understand why some consumers return to brands involved in unethical behavior can aid in the process of creating more ethical and sustainable markets.

1.3.1 Purpose

The purpose of this thesis is to use aforementioned transgression example to extend the research and increase the knowledge around why people continue to consume brands they know have been involved in unethical organizational behavior. It aims to investigate the consumers, and to identify what justifications they provide to support their actions. Within the academic field, a need to investigate this phenomena in relation to a real-world transgression have been identified (Dawar & Lei, 2009; Khamitov et al., 2019; Tsarenko & Tojib, 2015), something this thesis can assist in.

1.3.2 Research Question

Accordingly, this thesis aims to investigate Swedish bank consumers, and understand why they choose to remain as customers after a brand transgression. This in order to yield insights on the reasons behind these decisions. Therefore, our research question reads as follows:

RQ1 – Within the banking sector, what are the main justifications provided by Swedish consumers to why they continue to consume a brand they know have been involved in an ethical transgression?

Answering this question will help contribute to the theoretical field of consumer responses following a brand transgression, by adding to a gap existing within the field. Furthermore, by

identifying the justifications provided by consumers, the thesis will assist brand managers, and marketers in understanding the complex process of consumer reasoning.

1.4 Disposition

So far, this thesis has introduced a general background of the present issue, from which a problem has been derived. Then, the purpose and specific research question, based on the problem formulation, were introduced. Next, a chapter covering relevant previous literature within the field is presented. Following that chapter, the methodology of the thesis is outlined and discussed. The methodology chapter is followed by the presentation of the thesis’ findings, and an analysis of those findings. Towards the end, the main findings are summarized in the thesis’ conclusion. Lastly, a discussion is held covering theoretical, managerial, as well as ethical/societal implications, limitations, and future research opportunities.

1.5 Definitions / Abbreviations

Brand Transgression – A negatively valued (conscious or unconscious) action that violates the expectations a consumer has of a brand, and therefore has an impact on the consumer’s future evaluation of the brand and their joint relationship.

Money Laundering – “the processing of assets generated by criminal activity to obscure the link between the funds and their illegal origins” (International Monetary Fund, 2018).

Moral Agent – “a person who makes a moral decision, even though he or she may not recognize that moral issues are at stake” (Jones, 1991, p. 367).

CBR – Consumer-Brand Relationship

2 Chapter 2: Literature Review

This second chapter of the thesis presents a review of literature that can aid in the process of answering the presented research question. It includes theories and studies from multiple streams of research. However, all relevant in understanding the studied phenomena.

2.1 Brands and the concept of branding

One of the most important intangible assets a company possesses is its brand (Keller & Lehmann, 2006). Despite this, to conceptualize and define a brand and the concept of branding, has proven a difficult task. In an attempt to do so, De Chernatony and Dall’Olmo Riley (1998) studied definitions provided both by scholars, but also by branding professionals. The extensive study identified twelve themes around the term “brand”, who ranged from mere legal statements of ownership, to being a part of consumers’ identities or something people form great relationships with. This implies that managing a brand is both highly important, but many times also quite complex, and it may include diverse tasks such as positioning, evaluating, and strategically manage, your brand (Keller & Lehmann, 2006). Organizations who succeed with these tasks can reap the benefits stemming from a high brand equity, or “the added value with which a given brand endows a product” (Farquhar, 1989, p. 24). A high brand equity can help firms generate sales and increase market share (Hooley, Greenley, Cadogan, & Fahy, 2005), operate on higher margins (Farquhar, 1989), and create more efficient advertisements (Keller, 1993).

Moreover, since markets tend to be large, it makes it impossible for a company to have a personal relationship with every customer. Therefore, organizations rely on their brand in the relationship creating process. Hence, a trust for this brand becomes vital. When trusting a brand, it is not a physical person that is trusted, instead it is the symbol that a company stands behind, and the values that this symbol is associated with (Lau & Lee, 1999). Trust and loyalty are factors which are central in a relationship between customer and company. Reichheld and Schefter (2000) and Lau and Lee (1999) argue that before a customer’s loyalty is gained, the brand must be trusted. Trusting a brand and being loyal towards it, is therefore something that goes hand in hand, and something that has been recognized in the marketing literature for decades (Howard & Jagdish, 1969). Having a customer's loyalty will yield advantages, such as

customers. Loyal customers may also be ready to pay a higher price because it comes from a specific brand due to the uniqueness no other can offer (D. A. Aaker, 1991). Furthermore, another benefit stemming from trust and loyalty is the construction of a long-lasting relationship between a customer and a brand, where both trust (de Chernatony & Dall'Olmo Riley, 1998), as well as loyalty (Ahluwalia, 1999; Morgan & Hunt, 1994) are important antecedents.

2.2 Consumer-Brand Relationships

Previously, consumers were argued to mostly engage in transactional exchanges with companies. However, that notion have changed, and modern consumers tend to form meaningful relationships with the brands they consume (Webster, 1992). This change started a trend amongst marketing scholars to focus on the term consumer-brand relationships (CBRs). Fournier (1998) provided seminal work within this field where she followed three individuals and interviewed them around their brand usage history in relation to contextual factors of their lives. Results indicated participants to have an “interconnected web of brands” (Fournier, 1998, p. 359), which helped form their identity. Furthermore, and also more relevant to the purpose of this thesis, the notion was made that a CBR is not static, rather it is something that can evolve and change over time (Fournier, 1998).

2.3 Banking Sector Brands

Brands within the banking sector, and the relationships consumers have with such brands, tend to be a bit different from other brands. First and foremost, a strong brand, and especially a good organizational image, is extra important for a bank (Bennett, 1999). This since the industry is characterized by the need for trust, integrity, security, and dependability (Ennew, Wright, & Thwaites, 1993). Academic research focusing the characteristics of the Swedish banking industry in particular is to the authors’ knowledge very limited. However, some scholars have investigated potential determinants of bank selection. For example, 400 Swedish bank customers were surveyed in a study conducted by Zineldin (1996). The findings suggested there were five factors the consumers referred to as important when deciding upon which bank to use. These were (1) the service quality, (2) the price competitiveness, (3) the delivery systems, (4) the promotion and reputation, and (5) the differentiation. However, other studies have found bank selections to be a process of randomization, where up to a third of the Swedish customers have no real reason to why they are a customer of their particular bank (Martenson, 1985). Furthermore, the personal advisor at one’s bank have also been argued to be of key importance

when it comes to loyalty towards Swedish banks. Being pleased with the personal advisor can help increase the loyalty towards the bank as a whole. Something referred to as a “rubbing off” effect (Wahlberg, Öhman, & Strandberg, 2016). Important to note, however, is that the studies of Zineldin (1996) and Martenson (1985) were made prior to the financial crisis of 2007-2008. Something that, at least in other European countries, is argued to have impacted the banking industry substantially (Bennett & Kottasz, 2012; Kottasz & Bennett, 2016)

However, by looking at the research conducted on the characteristics of the banking industry in other European countries post the financial crisis, some insights can still be gained. In the United Kingdom for example, it is a common consensus that the banking industry, and its reputation, took a major hit due to the financial crisis of 2007-2008 (Bennett & Kottasz, 2012; Kottasz & Bennett, 2016). By surveying 1066 UK bank customers, Bennet & Kottasz (2012) also identified some groups of customers who held particularly low favorable views of the banking industry. One of these groups included customers who had been personally affected by the crisis. Similarly, Gritten (2011) found people who had suffered substantial financial loss as a consequence of the crisis, to negatively evaluate the banking industry. Furthermore, another group who, according to Bennett & Kottasz (2012), had non-favorable views of the banking industry were those who had obtained much information from media. During the crisis, UK banks were accused as being partly responsible for the economic downfall. Something Bennett & Kottasz (2012) argued to have impacted the customers who thoroughly followed reports from the media. Hence, they tended to evaluate the banking industry less favorably.

2.4 Brand Transgressions

The relationship between a consumer and a brand is impacted by many different factors, one of which being transgressions from brands. Brands who are involved in transgressions or scandals are often faced with a lot of negative responses from consumers (see for example: Ahluwalia et al., 2000; Dawar & Lei, 2009; Einwiller, Fedorikhin, Johnson, & Kamins, 2006; Trump, 2014). A brand transgression can take on many forms and an exact definition of such is difficult to provide. However, amongst marketing scholars some attempts to do so have been made; J Aaker, Fournier and Brasel (2004, p. 2) defined it as “a violation of the implicit or explicit rules guiding relationship performance and evaluation”. Magnusson, Krishnan, Westjohn and Zdravkovic (2014, p. 22) interpreted it as “a negative disconfirmation of customer expectations through acts of omission or commission by the brand”. Sayin and Gürhan-Canli(2015, p. 235)

argued it was “any behavior that violates the norms of the consumer-brand relationship”. Lin and Sung (2014) conceptualized it as a brand-related incident that ranges from product failure and poor service to companies’ violations of social codes, and that may serve as defining moments leading to significantly negative financial and psychological consequences. By analyzing the many definitions, the authors conceptualize a brand transgression as a negatively

valued (conscious or unconscious) action that violates the expectations a consumer has of a brand, and therefore has an impact on the consumer’s future evaluation of the brand and their joint relationship.

In academia, scholars have made separations between different types of brand transgressions. Most commonly, although sometimes named differently, they are divided into (1) performance-related crises, and (2) values-performance-related crises (Dutta & Pullig, 2011). Performance-performance-related crises are, as the name suggests, connected to an organization’s direct performance. It can include for example defect products (Pullig, Netemeyer, & Biswas, 2006), or inadequate service delivery (Roehm & Brady, 2007). Values-related crises, on the other hand, are not directly traced to the quality of the product or service an organization offers. Rather, it has to do with brands who deviate from the social or ethical expectations their consumers have, and whether the brand’s business in any way is creating societal damage (Dutta & Pullig, 2011). Instead of discussing functional benefits, it relates to an organization's ability to deliver more symbolic, societal, and psychological benefits (Pullig et al., 2006).

2.5 Consumer Responses to Brand Transgressions

Alongside the focus on what brand transgressions are, and what different forms they may take on, some brand transgression research have focused on the responses coming from consumers (Ahluwalia et al., 2000; Dawar & Lei, 2009; Einwiller et al., 2006; Fetscherin & Sampedro, 2019; Hassey, 2019; Kim, Park, & Stacey Lee, 2019; Septianto et al., 2020; Trump, 2014; Tsarenko & Tojib, 2015; Zhang, Kashmiri, & Cinelli, 2019). Just as a brand transgression can, and is likely to be, unique and different from case to case, so can the responses from consumers. There are many factors that influence how consumers react following a brand transgression. Factors such as the severity and type of the transgression (Fetscherin & Sampedro, 2019; Trump, 2014; Tsarenko & Tojib, 2015), the strength of the consumer-brand relationship (Ahluwalia et al., 2000; Dawar & Lei, 2009; Einwiller et al., 2006; Trump, 2014), and a brand’s characteristics (Hassey, 2019; Kim et al., 2019; Septianto et al., 2020; Tsarenko & Tojib, 2015;

Zhang et al., 2019) have all been argued to influence the outcome of consumers’ responses to bad firm behavior.

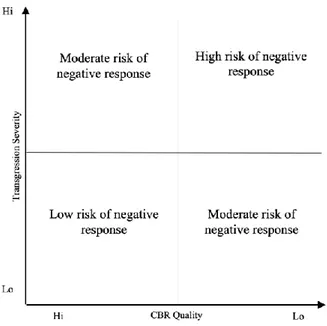

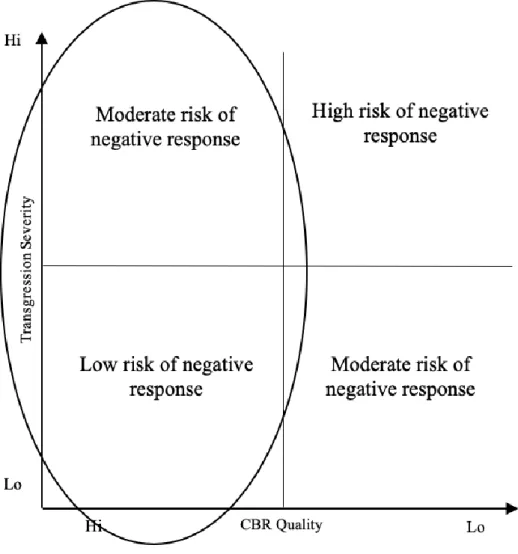

As discussed earlier, brand transgressions can take on many different forms (Dutta & Pullig, 2011), and the type of transgression has amongst scholars been argued to have an effect when consumers evaluate the situation. Fetscherin and Sampedro (2019) studied the difference in consumers’ willingness to forgive a brand dependent on whether the transgression was performance- or values-related. They surveyed 472 consumers from the United States, and results indicated a performance-related crisis was more likely to be forgiven by consumers, compared to a crisis that was values-related. Similarly, Trump (2014) found brands to be judged harder by consumers when the transgression was of an ethical nature. Furthermore, there has also been strong argumentations within academia that the severity of the transgression influences whether a transgression can be overlooked or not. For example, Tsarenko and Tojib (2015) found significant statistical support for the notion that as transgression severity increases, the level of forgiveness is likely to decrease, and similar studies have shown transgression severity as the main decider for forgiveness, independent of transgression type (Fetscherin & Sampedro, 2019). This is an idea that does not only hold true in the context of consumers and brands. When it comes to interpersonal relationships, transgression severity is also seen as the main decider of forgiveness (Fincham, Jackson, & Beach, 2005). By summarizing the literature presented in this section, it becomes possible to present a conceptual model around the relationship between the severity of the brand transgression (y-axis) and how the transgression is classified (x-axis). This model is presented in Figure 1.

Another important area of research around the topic of brand transgressions is how the consumer-brand relationship influences the evaluations from consumers. As noted, relationships are formed between consumers and brands. Relationships that can be of varying quality and intensity (Fournier, 1998), and this relationship is argued to have an impact on consumers’ evaluations following transgressions from, and negative information about, a brand (Ahluwalia et al., 2000; Dawar & Lei, 2009; Einwiller et al., 2006). One important study to test this idea was performed by Ahluwalia et al. (2000). Through two experiments involving a total of 139 respondents they looked at how commitment impacted consumers’ reactions to negative publicity. The results of the study showed how people who were highly committed to a brand were less likely to change their attitude towards it, as a result of the negative publicity. Furthermore, the highly committed group of consumers was also more ecstatic in their defense of the brand, and more likely to provide counterarguments to the information, in comparison to the less committed people. Another, similar study, looked at how identification could help buffer negative responses from consumers (Einwiller et al., 2006). Just as with commitment (Ahluwalia et al., 2000), consumers who felt a strong identification with a brand expressed less negative brand associations after being exposed to negative publicity, compared to those who felt a weak or no identification (Einwiller et al., 2006). Another important study touching upon this is that of Dawar and Lei (2009). This study tested how familiarity with a brand influenced the responses from consumers following a crisis. Similar to the aforementioned studies (Ahluwalia et al., 2000; Einwiller et al., 2006), results indicated consumers who were more familiar with a brand to be less judgmental following the crisis. The explanation to this Dawar and Lei (2009) claimed was the familiar consumers’ ability to more accurately evaluate the situation. This since they had the knowledge and information to decide whether the transgression was relevant to the brand’s core values or not, and could therefore make an adequate assessment of whether to act upon the scandal. Non-familiar consumers, however, did not have this capability and therefore tended to evaluate brands negatively irrespective of the relevance of the transgression (Dawar & Lei, 2009). Once again, this research can be summarized into a conceptual model. Just as in Figure 1, the y-axis represents transgression severity. However, the x-axis now relating to the quality of the consumer-brand relationship. Important to note is that the model makes the assumption that there always is a relationship present. This implies that having a “low” CBR quality in this particular model does not equal having no relationship. A relationship need to be present in order for the matrix to be applicable. This second model is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2 - Transgression Matrix (Severity vs Relationship Quality)

Following this, the presence of a previous relationship between the consumer and the brand, whether it has to do with commitment (Ahluwalia et al., 2000), identification (Einwiller et al., 2006), or familiarity (Dawar & Lei, 2009), can be argued to protect brands against transgressions and negative publicity. This notion have been conceptualized as a buffering effect (Dawar & Lei, 2009; Trump, 2014). However, some research have also looked critically at this buffering effect in order to determine in what situations it actually holds true. Dawar and Lei (2009, p. 192) for example, argued that when it came to “extremely negative information”, the buffering effect no longer held. Furthermore, an argumentation has also been made that the type of transgression may impact the buffering effect. Trump (2014), for example, conducted research on 166 undergraduate students to examine this notion. Results indicated that a buffering effect was present, however, only to some extent; when transgressions were self-relevant to the consumer, and/or of an ethical nature the impact of the buffering effect seemed to diminish. This provides an important aspect to consider when discussing the effect of previous relations between the brand and a consumer on evaluations following brand transgressions. It is true that a healthy consumer-brand relationship can help protect brands against transgressions and negative information (Ahluwalia et al., 2000; Dawar & Lei, 2009; Einwiller et al., 2006). However, the extent to which this holds true depends on how negative the information is (Dawar & Lei, 2009), and/or what type of transgression that has taken place (Trump, 2014).

During the last years, there has also been an increase in the interest around how brand characteristics and brand image affect responses from consumers when exposed to a brand transgression. One of the major studies around this was made by Tsarenko and Tojib (2015). They investigated how a firm’s previous corporate social responsibility (CSR) behavior impacted the responses of consumers. CSR is when an organization works in a sustainable way and takes environmental, societal, economic, stakeholder, and philanthropic responsibility (Dahlsrud, 2008). Findings amongst the 202 respondents indicated that an organization involved in beneficial CSR activities prior to the transgression were excused to a larger extent, compared to organizations who was not (Tsarenko & Tojib, 2015). Another study on brand characteristics’ effect on consumer responses touches upon the concept of brand personality (Hassey, 2019). This study divides brands into two major categories; warm brands and competent brands. Warm brands are associated with characteristics such as friendly and sincere, whilst competent brands are seen as capable and skilled (J Aaker, Vohs, & Mogilner, 2010; Hassey, 2019). Somewhat surprisingly, findings suggested that consumers who were exposed to a values-related (communal) failure tended to judge warm brands less negatively compared to competent brands. On the other hand, when consumers were exposed to a performance-related (functional) failure, the competent brand was easier excused (Hassey, 2019). This implies that a brand’s characteristics can influence how consumers respond to a transgression, and different types of transgressions might be evaluated differently dependent on the particular characteristics of the involved brand.

Another characteristic of a brand that has been argued to influence consumer responses is the age of the brand (Zhang et al., 2019). By surveying a total of 659 respondents across two different studies, the authors came to the conclusion that brand age was another factor that could have buffering effects against transgressions. This buffering effect was mainly present when information from the organization was ambiguous and had room for interpretation. In such situations, the brand age helped consumers to judge the brand, and an older brand was seen as more credible compared to a younger one. However, when the situation was clear and easily understandable, brand age did not seem to buffer against transgressions (Zhang et al., 2019).

2.6 Ethical Decision-Making

Another stream of research which is relevant when discussing how people make decisions is that of ethical decision making (EDM) theory. When a decision is ethical, it is “both legal and

morally acceptable to the larger community” (Jones, 1991), whilst a decision that is unethical is “either illegal or morally unacceptable to the larger community” (Jones, 1991, p. 367). Amongst scholars, research on why (or why not) individuals make ethical decisions has been a popular topic during the late 20th and early 21st century, and much have been discovered within

the field (Schwartz, 2016). Studies within business and administration have mainly focused on EDM amongst employees, and in organizations (see for example: Anand, Ashforth, & Joshi, 2004; Ferrell & Gresham, 1985; Jones, 1991). However, most findings stem from psychological research (Schwartz, 2016). Hence, they can be argued to be relevant also in EDM from consumers, which is the focus of this thesis. In an attempt to connect and bridge the different streams of EDM research into one model, Schwartz (2016) proposed an integrated ethical decision making model (I-EDM). The model builds on previous literature and incorporates different aspects of EDM. The following sections will use parts of Schwartz I-EDM model to explain relevant fields of EDM.

2.6.1 Situational Contexts

One important factor in EDM, and also a part of Schwartz’s (2016) I-EDM model, is the situational factors of the issue/dilemma itself (Jones, 1991). Jones (1991) argues that the characteristics of the issue itself impact the decision of the moral agent. This is referred to as the moral intensity, and consists of six components; (1) Magnitude of Consequences, (2) Social Consensus, (3) Probability of Effect, (4) Temporal Immediacy, (5) Proximity, and (6) Concentration of Effects. These are described below.

2.6.1.1 Magnitude of consequences

An important factor in ethical decision-making has been argued to be the magnitude of the consequences, or the level of harm (benefit) the moral issue brings to the victims (beneficiaries). The idea stems both from the common-sense understanding that the worse the consequences of a decision are, the less likely humans are to make such decision (Jones, 1991), but also from empirically tested data. For example, research conducted on ethical behavior amongst marketing managers indicated a higher likelihood of an ethical decision when serious consequences were likely to arise (Fritzsche & Becker, 1983). It is assumed that a reason for unethical decisions can be the fact that the magnitude of the consequences are perceived as too low, and hence the moral agent make an unethical, or at least a non-ethical, decision (Jones, 1991).

2.6.1.2 Social consensus

The second component of moral intensity is the idea that a social agreement upon whether how good or how evil an act or a decision is impacts the moral agent in the decision-making (Jones, 1991). An empirical study testing this investigated the differences in responses toward an illegal (and unethical) issue compared to a legal (but still unethical) one. Results showed ethical decisions to be more likely when the issue was illegal than if not (Laczniak & Inderrieden, 1987). The reasons for this the authors claim might stem from people perceiving a higher ethical severity in illegal actions, whilst an unethical but still legal action is more difficult to recognize. Hence, unethical decisions that have a largely shared social consensus of being evil, tend to bring more ethical decisions from people, and vice versa (Jones, 1991). To further strengthen his arguments, Jones (1991, p. 375) provides an example: “The evil involved in bribing a customs official in Texas has greater social consensus than the evil involved in bribing a customs official in Mexico”. This indicates that an unethical decision is more likely to arise in a country or region where the decision is viewed as less unethical, compared to a country or region where it is viewed as more unethical.

2.6.1.3 Probability of effect

Another component of moral intensity is the probability of effect. The probability of effect refers to the likelihood of the ethical issue taking place, and also the probability of it causing the harm it is expected to cause. Whenever the probability of either the occurrence of an act, or the occurrence of the act’s consequences, falls below 1, moral intensity is reduced. Hence, also decreasing the likelihood of the moral agent making an ethical decision (Jones, 1991). It is important to remember that individuals are poor at estimating probabilities (Kahneman, Slovic, & Tversky, 1982). However, in this context estimates are often sufficient (Jones, 1991).

2.6.1.4 Temporal Immediacy

The fourth component of Jones’s (1991) moral intensity is the temporal immediacy. This component refers to the length of time between the decision and the potential occurrence of the unethical act. Jones (1991, p. 376) claims “people tend to discount the impact of events that occur in the future. [...]. The greater the time period, the greater the discount”. The basic idea is that additional time can impact the moral agent in a way that might reduce the feeling of urgency. Hence, leading to an unethical decision (Jones, 1991).

2.6.1.5 Proximity

The fifth component is proximity. Proximity refers to how close a moral agent feels to the victims of the evil act, and it can include social, cultural, psychological, or physical distance. The larger this distance (social, cultural, psychological, or physical) is perceived to be, the less likely the moral agent is to make an ethical decision (Jones, 1991). Empirically this was tested in a famous study within psychology by Milgram (1975). In Milgram’s (1975) experiment the subjects, in that case labelled “teachers”, were ordered to induce shocks to what they thought was a learner when the learner answered questions incorrectly. The findings of the study reported subjects to have a much lower obedience to authority when physical contact with the learner was present, compared to when it was not. Hence, their feelings of closeness (proximity) to their learner impacted how much harm they could induce him or her.

2.6.1.6 Concentration of effects

The last component of moral intensity is the concentration of effects, and includes how concentrated the effect of the moral issue and its consequences are. A more concentrated effect, that is it impacts only a few individuals, tend to cause more ethical decisions compared to issues where victims are many (Jones, 1991). Jones (1991, pp. 378-379) further illustrates this by stating an example: “Cheating an individual or small group of individuals out of a given sum has a more concentrated effect than cheating an institutional entity, such as a corporation or government agency, out of the same sum.” Hence, when consequences are concentrated to a small group of victims, the ethical issue seem to be more present.

2.6.2 Moral Awareness and Lack of Moral Awareness

Other areas of research around EDM, and another incorporation in Schwartz’s (2016) I-EDM model, is moral awareness, and the potential lack thereof. Moral awareness is defined as “the point in time when an individual realizes that they are faced with a situation requiring a decision or action that could affect the interests, welfare, or expectations of oneself or others in a manner that may conflict with one or more moral standards” (Schwartz, 2016, p. 765). Moral awareness can originate from many factors. Within organizations for example, codes of ethics and ethical training can increase moral awareness amongst employees (Tenbrunsel, Smith-Crowe, & Umphress, 2003). However, it can also originate from an individual’s moral capacity and ability

to recognize ethical issues (Hannah, Avolio, & May, 2011), something that can be argued to be more important for the purpose of this thesis.

The role of moral awareness in EDM becomes apparent when you start to look at the lack thereof. This since someone who is not aware of an ethical dilemma can still engage in what can be referred to as “unintentional” ethical or unethical behavior (Tenbrunsel & Smith-Crowe, 2008). It is important to note that the lack of moral awareness is not simply a lack of knowledge around the issue’s occurrence. Rather, a common process within EDM is moral disengagement. Moral disengagement is when a moral agent convinces oneself that ethical standards do not apply (Bandura, 1999). Bandura (1999) proposes a number of antecedents to moral disengagement, two of which being of importance for this study. Firstly, people tend to transfer the responsibility of the ethical decision to someone else. A process referred to as displacement

of responsibility. The idea stems from people’s tendency to obey authorities (see for example

Milgram, 1975). When people displace their responsibility they tend to feel less personal responsibility for the immoral or unethical actions, since they are not actually the moral agent (Bandura, 1999). Secondly, the responsibility of individuals can also be diffuse and unclear. This is referred to as diffusion of responsibility. One common part of diffusion of responsibility is group decision making. When there are groups making (or not making) the ethical decision, it becomes unclear who actually is to be held accountable (Bandura, 1999).

Bandura’s (1999) framework on moral disengagement was extended by Anand et al. (2004) who researched justifications provided by employees to why they engaged in corruption. Some of the findings were similar to those of Bandura (1999). For example, the authors found denial of responsibility as a common rationalization (Anand et al., 2004). However, they also identified other antecedents such as denial of injury, denial of victim, social weighting, appeal

to higher loyalties, and the metaphor of the ledger. Since Anand et al.’s (2004) research was

conducted in an organizational context, some of these (e.g. appeal to higher loyalties and the metaphor of the ledger) are of less importance to this thesis. Therefore, only the remaining three are described below.

Firstly, denial of injury is when individuals convince themselves that their unethical behavior has no real negative consequences. It can also include people comparing the severity of the issue to others, judging the situation they are involved in as less severe. Secondly, denial of

can for example include the claim of victims deserving it due to past bad behavior (Greenberg, 1998), or depersonalization of victims (Bandura, 1999). Lastly, social weighting occurs when people compare themselves or the situation to others who could be argued to be even more unethical (Gibbons et al., 2002). Hence, by doing so the individual can rationalize the behavior by claiming others have been just as bad (Anand et al., 2004).

2.6.3 Moral Consultation

Another factor that might influence the decision-making of a moral agent is the interaction with others. Schwartz (2016, p. 789) referred to this as moral consultation, and defined the concept as “the active process of reviewing ethics-related documentation or discussing to any extent one’s ethical situation or dilemma with others in order to receive guidance or feedback”. The feedback can come from for example a friend, a family member, or a colleague (Schwartz, 2016). The idea is that people are influenced by their peers as they for example are provided with counterarguments they would not have seeked out themselves, leading to a change (good or bad) in the decision to be made. Hence, it is argued that moral change is usually an outcome of social interaction (Haidt, 2007). Consulting others is most often a way to make a more ethical decision. However, interacting with others can sometimes also impact moral agents to make unethical decisions. This since as they, for example, might realize that the unethical behavior is not frowned upon by their peers. Hence, reducing the likelihood of avoiding such behavior (Schwartz, 2016).

As indicated by this extensive literature review, there are multiple factors that have the potential to influence how consumers’ respond to brand transgressions. Explanations relating to for example transgression severity (Fetscherin & Sampedro, 2019; Tsarenko & Tojib, 2015), type of transgression (Fetscherin & Sampedro, 2019; Trump, 2014; Tsarenko & Tojib, 2015), brand characteristics (Hassey, 2019; Zhang et al., 2019), and the previous consumer-brand relationship (Ahluwalia et al., 2000; Dawar & Lei, 2009; Einwiller et al., 2006) are touched upon. Furthermore, EDM theory (Anand et al., 2004; Bandura, 1999; Jones, 1991; Schwartz, 2016) might also help explain decisions of consumers. This highlights the fact that there are many factors influencing consumer responses following a brand transgression, and contexts are likely to be judged differently by different individuals. Hence, this will be of key importance to consider throughout the work with this thesis.

3 Chapter 3: Methodology

This third chapter of the thesis presents a detailed overview of how the research went about. It starts with a discussion of the research philosophy applied, and is then followed by the research design. Furthermore, it describes how the data was collected, and how that data later was analyzed. Lastly, the chapter discusses how trustworthiness of the data was assured.

3.1 Research Philosophy

The research philosophy applied in this research was that of interpretivism. Interpretivism argues that humans are different from physical phenomena as humans create meanings. Meanings that interpretivists later studies from a subjective perspective. Contrary to positivism, interpretivism does not aim to create a universal law for how people act.Rather, it focuses on yielding new, and more in-depth understanding of the social world and its context (Saunders, 2016). In relation to this thesis, this implies that by using the interpretivist approach it becomes possible to create a deeper understanding of the justifications provided by consumers to why they choose to consume unethical brands. Furthermore, since these justifications are expected to be of different nature, the creation of a universal law on how people act following brand transgressions would not fit the purpose of the research. Hence, the interpretivist approach becomes the most suitable for this particular thesis.

People with different cultural backgrounds, at different circumstances and time will create different meanings. This will also result in that different people will experience different social realities. This is the part of interpretivism that is most critical against the part of positivism where general laws are applied to everybody. The risk of using positivism is to lose deep insights of the humanity as too simple rules are applied to much more complex phenomena (Saunders, 2016). Furthermore, the interpretivist strand phenomenology was applied throughout the study. Phenomenology studies the lived experiences of individuals, with the recollections and interpretation of the experience (Saunders, 2016). Since the aim of this thesis was to ask for insights around consumers’ experiences, a phenomenological approach was applicable. Also, the fact that interpretivism is focusing on the human and its social world and not setting any general rules made it a suitable philosophy to use in the research that was conducted.

3.2 Research Design

The main purpose of this thesis was to extend the research and increase the knowledge around why people continue to consume brands they know have been involved in unethical organizational behavior. Furthermore, it aims to answer the question; “Within the banking

sector, what are the main justifications provided by Swedish consumers to why they continue to consume a brand they know have been involved in an ethical transgression?” Based upon

this, it was decided to pursue an exploratory study. This since exploratory studies help to clarify the understanding of a phenomena of which people are unsure about its precise nature (Saunders, 2016). The phenomena in this case being the consumption of unethical brands. Furthermore, as indicated in section 1.3 and in the literature review, previous research around the specific purpose of this thesis is limited. Therefore, to perform for example an explanatory study would not be suitable (Saunders, 2016).

After carefully analyzing and specifying the purpose of this thesis in order to clarify what type of study was to be conducted, the next step was to decide upon which method to be the most suitable to the research. In general, researchers make use of three main methods; quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods (Saunders, 2016). For the purpose of this thesis, it was decided to make use of a qualitative method. In qualitative research, the researcher studies and analyzes socially constructed meanings provided by individuals (Saunders, 2016). The reason for deciding upon a qualitative research approach once again stems from the purpose of the thesis. The aim is to find what justifications consumers provide to why they choose to consume brands the know have been involved in unethical behavior. The number of previous studies identifying such justifications are very limited. Hence, it becomes difficult to test them only using numerical numbers (i.e. using a quantitative method). Rather, this thesis becomes a way to identify the explanations provided by consumers. Explanations that could be a foundation for quantitative research in the future. Furthermore, qualitative studies are closely connected to the research philosophy of interpretivism, and to exploratory studies (Saunders, 2016). Since both interpretivism and exploratory research are parts of this thesis, this provides further argumentation to the relevance of the choices.

3.2.1 Research Approach

Another important aspect of the methodological considerations made for this thesis was how to approach the theory development, and how the data was to be analyzed. Initially the plan was

to adopt inductive reasoning. Inductive reasoning moves from data to theory, and a researcher’s task is to make sense of the interview data collected (Saunders, 2016). However, along the process it became apparent that some deductive aspects to theory development could also be helpful to answer the research questions. Deductive reasoning is the opposite of inductive reasoning, and instead of moving from data to theory, one moves from the presented theory to the data. In short, deductive reasoning could be explained as an empirical test of an existing theory (Saunders, 2016). This helped reach the conclusion that the thesis could benefit from a combination of the two approaches. Therefore, the ultimate decision landed on abductive reasoning. Abductive reasoning combines both inductive and deductive reasoning (Suddaby, 2006), and is the approach most commonly used in practice when it comes to research in business administration (Saunders, 2016). In academia, abduction is often conceptualized as starting with a surprising fact, which the researcher then aims to explain or partly explain with the help of empirical and academic evidence (Ketokivi & Mantere, 2010). In this thesis the

surprising fact is the consumers’ decisions to consume brands involved in unethical behavior,

something that aims to be answered with the help of the data collected. Hence, using an abductive approach for this particular study also makes sense from an academic perspective. Furthermore, abductive reasoning allows the researcher to incorporate existing theories where applicable, whilst at the same time leaving room to modify them or suggesting new theories (Saunders, 2016). This is beneficial for this thesis in the sense that some of the answers provided by consumers are likely to be related to existing theory, whilst others might reveal new insights. Hence, the use of an abductive approach will increase the ability to elaborate on different explanations, and therefore increase the depth and relevance of the final conclusions.

3.2.2 Research Strategy

The way to how these final conclusions were to be reached was then outlined in the research strategy. For the purpose of this thesis, it was decided to make use of in-depth qualitative interviews. Such interviews are characterized by not having a standardized format that is replicated during each interview. Instead, there are only key questions and themes that the researcher aims to cover during the interview (Trost, 2010). When deciding upon which strategy to use, Saunders (2016) outlines some important factors to consider. Factors that were used in the methodological development of this thesis. How these factors coincide with the purpose of this particular thesis is discussed in the following section.

Firstly, Saunders (2016) highlights the importance of connecting your research strategy with the purpose of the study. He suggests that when undertaking an exploratory study, in-depth interviews are the most appropriate strategy to adopt. This since such studies often have the need for a deep understanding of the decisions made by interviewees, something that in-depth interviews can help to provide. Following this logic, the use of in-depth interviews becomes the most appropriate also for this thesis. What it aims to achieve is to identify justifications to why people continue to consume a brand involved in unethical behavior. Therefore, a deep understanding of the decisions of these consumers is of key importance in order to provide insightful conclusions. Furthermore, having in-depth interviews will allow for the possibility to let participants elaborate around their answers (Saunders, 2016). This becomes vital since this thesis is adopting an interpretivist approach, and answers need to be interpreted by the authors. Hence, allowing participants to elaborate is crucial in order to make sure their answers are understood in a correct way.

Secondly, Saunders (2016) argues that when a topic is of sensitive nature, in-depth interviews can be beneficial as it helps to ensure trust for the researchers. The topic of this thesis could be argued to be of rather sensitive nature. Even though the authors are not judging the participants in any way, there is an understanding that the interview might be viewed as some type of “interrogation”, where participants are questioned about a decision that the general public might frown upon. Therefore, it becomes extra important to create a comforting environment where participants feel secure. Participants who only receive a survey via the internet, tend to be reluctant to answer sensitive information (Saunders, 2016). An in-depth interview on the other hand will allow for a feeling of trust to be created, and therefore also help to increase the authenticity and depth of participants’ answers.

Lastly, when deciding upon research strategy, a researcher need to examine what type of questions that are intended to be asked during the data collection. For example, when questions are complex and/or of open-ended nature, in-depth interviews are the most appropriate strategy to use (Saunders, 2016). The questions planned to be asked during the collection of data for this particular thesis can be considered both complex, and certainly open-ended. Providing a questionnaire with a list of alternatives which participants were to choose from would be close to impossible due to the open-ended nature of the questions. Hence, the use of in-depth interviews is a suitable fit for the type of questions that are to be asked.

In conclusion, there are a number of argumentations supporting the decision to use in-depth interviews as the method of data collection for this particular thesis. However, as with all other techniques, in-depth interviews provide the researcher with a number of challenges. These challenges and how we have made sure to reduce the risks associated with them are discussed below.

3.2.2.1 Challenges Associated with Chosen Strategy

When conducting interviews, there is always a risk of collecting data that does not fulfill the desired quality. One large concern is how reliable the data is. Data is reliable when the study can be replicated and still show the same results. In qualitative research, the reliability is sometimes threatened by biases. It can be bias from the interviewer (interviewer bias), bias stemming from interviewees perception of the interviewer (interviewee/respondent bias), or a bias in participators’ characteristics (participant bias) (Saunders, 2016). In order to make sure to limit these biases as much as possible, the authors followed five suggestions from Saunders (2016); Firstly, by the help of the extensive literature review and relevant industry sources, the interviews were entered with a great level of topic knowledge. Secondly, relevant information about the interviews were provided prior to the day of the interview, and at the day of the interview, to assure the knowledge amongst participants. Thirdly, the interview location was thoroughly evaluated in order to create a comforting environment. Initially the plan was to hold all interviews face-to-face in a similar room at Jönköping International Business School. However, an outbreak of the Coronavirus Covid-19 (more on this in section 3.3.3) made this inappropriate. Therefore, the majority of the interviews were conducted digitally. However, the interview location was still taken into consideration. The interviewers were placed in environments that were calm and non-disturbing. Interviewees, on the other hand, got to choose their location themselves. Even though digital interviews might be inferior compared to face-to-face interviews, the ability to perform the interview in a comforting environment at home can sometimes be beneficial as it is familiar and feels safe for the participant (Hanna, 2012). Fourthly, even though interviews were conducted digitally, the interviewers still dressed appropriately, and used similar, non-offensive clothing. Lastly, a focus was put on delivering questions in a unified approach were the tone was neutral and the content was clearly expressed. By spending time and effort on these factors, the reliability of the thesis is hoped to be increased. However, important to note is that qualitative research is not necessarily intended to be completely replicable. This since such studies reflect the time they were conducted in, and are

thorough explanation of the used research design, and what argumentations there are to support the decisions.

3.3 Data Collection

3.3.1 Sampling

Sampling is close to always necessary in order to conduct research. This since the research in most cases is limited by time, resources, and access (Saunders, 2016). The focus of this thesis was to investigate why consumers continue to consume a brand they know have acted unethically, by investigating consumers of Swedbank. Hence, participants in the study needed to be aware of the scandal, and also a consumer of the bank, in order to suit the purpose of the study. Therefore, it was essential to find people that fulfilled these criteria. In order to do so, purposive sampling was applied. Purposive sampling is when a researcher uses his or her own judgement in order to select cases that are of particular interest, and therefore can provide rich data which will help to answer the defined research question(s) (Saunders, 2016). According to Guba (1981), the purposive sampling method does not aim to be representative or typical. Furthermore, this sampling method does not have the purpose of generalizing the sample, but instead go more into depth on individual level. The goal is to find out as much information as possible from the source, and diversity in a non-representative way is rather preferred than frowned upon (Guba, 1981). For this particular research, this implies that the sample consisted of people who were (1) consumers of the bank in question, and (2) aware of the money laundering scandal.

The first step in the process of finding relevant people to interview was to distribute an online questionnaire, which was distributed through social media. The purpose of the questionnaire was to identify participants that fit the aforementioned criteria, and hence were suitable for the interviews that were to be conducted. Furthermore, the questions were very few and simple. It included sections on what bank the person used at the time of answering, whether they at any time had switched bank, and about the awareness of the discussed brand transgression. Towards the end of the questionnaire, an option to include contact information was presented. People who filled out their contact information, and fitted our criteria, was contacted and interviewed. Those who answered the questionnaire remained anonymous, unless, of course, they chose to enter their contact information. This since the anonymity and confidentiality of participants are

important to respect (Saunders, 2016). Even if respondents chose to enter their contact information, they were always allowed to withdraw from participating, as recommended by Saunders (2016). The questionnaire in full can be found in Appendix A.

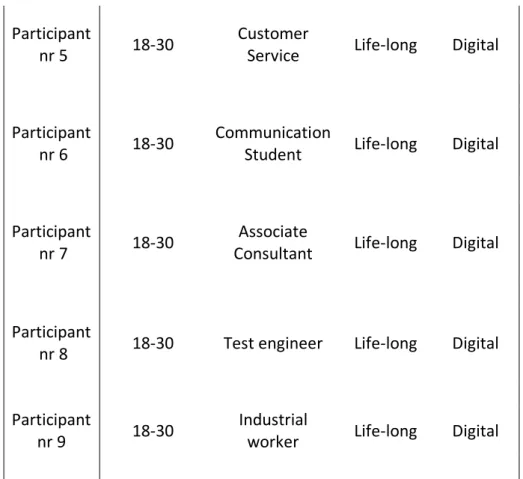

In total 137 answers were received, out of which 19 people signed up for a potential interview. The answers of these people were then analyzed in order to find people relevant and suitable for an interview. As mentioned, there were two criteria people needed to fulfill in order to fit the purpose of this thesis. First and foremost, they had to be a customer of Swedbank, and secondly they needed to be aware, and have some knowledge, about the money laundering scandal. This last criteria was assessed by a question in the survey asking people to (based on their own judgment) indicate their own level of knowledge. Four alternatives were given, and only people choosing the highest (I know the scandal have occurred, and have thoroughly followed the media coverage), or the second to highest (I know the scandal have occurred, and have partly followed the media coverage), alternative were chosen for interviews. In conclusion, this resulted in nine (9) people being interviewed. A summary of relevant information about the nine (9) participants can be found in Table 1.

Age Category Occupation Years as a customer Interview Location Participant nr 1 18-30 Business

Student Life-long JIBS*

Participant nr 2 31-50 Consultant within digital marketing 4 Digital Participant nr 3 51 + Management Consultant 7 Digital Participant nr 4 18-30 Freelance within media production 8 Digital