GDPR - Are We Ready?

A Comparative and Explorative Study of the Changes in Personal

Data Privacy and Its Impact on ICT Companies

GDPR - Är vi redo?

En komparativ och utforskande studie av förändringarna i den

personliga datasekretessen och dess inverkan på ICT företag

by Therése Nielsen & Johannes Wind

2018-06-09

Bachelor Thesis in Computer Science and Information Technology, 15 hp Malmö University Spring 2018

Supervisor Agnes Tegen agnes.tegen@mau.se Examiner Mia Persson mia.persson@mau.se

Abstract

Personal data flows through our entire society in the shape of technological processing. This makes it difficult for individuals to have control over their personal data being processed by companies. On the 25th of May 2018 the Swedish Personal Data Act (PuL) is replaced by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The regulation is designed to set a uniform standard with regards to the way we collect, use and share personal data of European citizens. This research uses a two-step research approach. The first step is to perform a comparative legal research to identify the new requirements that comes with the upcoming Regulation in relation to the current Swedish legislation. The second step is to use the findings of the comparative legal research as a foundation for an explorative survey of how ICT companies are preparing for the new requirements of the GDPR. Our result shows that the participating ICT companies are preparing by implementing new processes and measures in order to comply with the Regulation. Additionally, all of the participating companies are at the time of our research not fully compliant with the Regulation. Our research concludes that the difficulties in achieving full compliance lies in the lack of resources and ambiguities of the interpretation of the Regulation.

Keywords

GDPR, PuL, Personal Data, Privacy Protection, GDPR-compliance, ICT Companies

Sammanfattning

Personlig data genomsyrar hela vårt samhälle och hanteras digitalt via informationsteknologi. Detta försvårar för individer att ha kontroll över den personliga data som hanteras av företag. Den 25 maj 2018 ersätts den svenska Personuppgiftslagen (PuL) med den nya Dataskyddsförordningen GDPR. Förordningen är utformad för att sätta en enhetlig standard gällande hur vi samlar in, hanterar och delar europeiska medborgares personliga data. Den här forskningen är uppdelad i två steg. I det första steget genomförs en komparativ undersökning av de två lagtexterna för att identifiera de nya lagkraven som Dataskyddsförordningen medför. I det andra steget används resultatet från den komparativa jämförelsen som grund för en explorativ undersökning av hur ICT-företag förbereder sig inför de nya lagkraven. Vårt resultat visar att de deltagande ICT-företagen förbereder sig genom att implementera nya processer och åtgärder för att följa förordningen. Inga av de deltagande företagen är vid tiden av denna undersökning fullständigt kompatibla med de krav den nya förordningen ställer. Vår forskning visar att svårigheterna med att bli fullständigt kompatibel ligger i bristen på resurser och tvetydigheten i tolkningen av förordningen.

Nyckelord

Contents

1 Introduction ... 1 1.1 Purpose ... 1 1.2 Research Problem ... 1 1.2.1 Scope... 2 1.2.2 Research Questions ... 31.3 State of the Art ... 3

1.4 Disposition ...4

2 Theoretical Background... 5

2.1 Personal Data ... 5

2.2 The Swedish Personal Data Act (PuL) ... 5

2.3 The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) ... 6

2.4 Keywords ... 6

3 Methodology ... 7

3.1 Mixed Methods Design ... 7

3.1.1 Exploratory Sequential Mixed Method Design ... 7

3.1.2 Challenges ...8

3.2 Comparative Legal Research ... 9

3.2.1 Selection ... 9 3.3.2 Review Approach ... 10 3.2.3 Method Discussion ... 10 3.3 Survey ... 11 3.3.1 Survey Approach ... 11 3.3.2 Method Discussion ...12 3.3.3 Covering Letter...12 3.3.4 Questionnaire ... 13 3.3.5 Expert Review ... 14 3.3.6 Case Selection ... 14 4 Results... 15

4.1 Comparative Legal Research ...15

4.1.1 Fines ...15

4.1.2 Documentation ...15

4.1.3 Consent ... 16

4.1.4 The Right to Be Forgotten ... 16

4.1.5 Data Portability ...17

4.1.6 The Controller and Processor ...17

4.1.7 The Data Protection Officer ... 18

4.1.8 Data Protection Impact Assessment... 19

4.1.10 Data Protection by Design and by Default... 20

4.1.10 The Rule of Misconduct ... 20

4.2 Survey Result ...21 5 Analysis ... 28 6 Discussion ... 32 7 Conclusion ... 35 8 Future Research... 36 References ... 37 Appendix ... 40

1

1 Introduction

Everyone talks about GDPR, but what is it? Who does it apply to? And how will it affect your company or organization?

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) comes into force on May 25, 2018 and replaces the current Data Protection Directive of 1995 (DPD). The purpose of the GDPR is to enhance and unify personal data protection within the European Union (EU) and the European Economic Area (EEA). The regulation is designed to set a uniform standard with regards to the way we collect, use and share personal data of European citizens. Individuals are becoming more aware of their rights and the responsibilities of the companies collecting their personal data. This calls for higher levels of data security, transparency, policies and procedures.

1.1 Purpose

The primary concern of this research is to examine the meaning and consistency of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

The reason for writing this report is to advance our understanding of what the GDPR entails and what its arrival currently means for companies that process personal data within the Swedish market.

The purpose of this research is twofold. First, this study identifies and analyses the differences between the current Swedish Personal Data Act (PuL) and the coming General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Secondly, we aim to explore the preparations of which the GDPR is having on Information and Communications Technology (ICT) companies within the Swedish market. Furthermore, this research provides valuable implications to where personal data protection within the EU is heading.

1.2 Research Problem

The last years of technological development has formed the Internet and life of many individuals. Internet has made it easier to find information, communicate and perform our everyday tasks. Spending so much time using digital services and social media implies that we most likely also leave traces of massive amounts of personal data behind. This enables new ways for companies to collect data about its users.

This data does not only consist of information directly associated to users such as name, phone number or addresses. It may consist of data that shows our preferences for food, clothes, interests, daily routines and so much more. As a result, companies have the possibility to use this data for other purposes then many of us intended. Therefore, it is reasonable to ask; is all this personal data processing necessary and what is it really used for?

An example of this problem is social media marketing. Marketing ads within social media applications are shaped after our previous browsing and searches on the Internet (Facebook, 2018). This seems like a harmless act of companies to increase the chances of us buying their products or services. What we now know is that this type of personalized marketing is just the

2

tip of the iceberg to what this data really is used for. In the beginning of 2018, it was internationally revealed that the company Cambridge Analytica had used personal data to create algorithms to try to affect the US Presidential Election (The Guardian, 2018).

Swedish authorities, municipalities, companies and organizations daily performs personal data processing of its 10 million inhabitants. That involves a lot of personal data. However, when it comes to personal data processing, Sweden already has rules to relate to in the Personal Data Act (PuL). The discussion of personal data has resulted in a new regulation called the General Data Protection (GDPR). Since this regulation comes into force in the near future, companies and organizations are right in the middle of their work towards GDPR-compliance. The new regulation involves new rules and therefore also imposes major changes for companies. To get closer to answering what those challenges might be, it is of great interest to identify the differences between current Swedish legislation (PuL) and the imminent EU legislation (GDPR). Though the upcoming legislation is yet to come into force, we are currently dealing with a phase of perplexity where both practical and theoretical interpretations of the legal content is being made. This is problematic in the sense that companies most likely handles the upcoming challenges differently, undertaking varying actions based on their own understandings. For this reason, it is highly interesting to explore companies’ GDPR-awareness and map what they are actually doing on their road to GDPR-compliance. In addition, it is noteworthy to find out how prone to change companies might be when they risk naming and shaming along with potential administrative fines.

1.2.1 Scope

The new Regulation affects all entities that collect and process personal data within the European Union. One of the changes is that the Regulation is even applicable to entities that direct their goods or services at European users, without physically being located within European territory (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p.5).This study does not include all Member States or third-party countries. The Swedish market is our area of focus.

Our study has a clear business perspective examining GDPR’s impact on companies and not individuals. The company impacts are of course a result of the changed rights of individuals, but we narrow the scope to specific company measures. This study examines how companies currently prepare for GDPR-compliance by assessing what they do to meet the new requirements.

The study is limited to companies within the Information and Communications Technology (ICT) area. The ICT-term is commonly accepted to mean all technologies that jointly allow people and organizations to interact in the digital world (Tech Target, 2017).

ICT is sometimes used synonymously with IT (Information Technology), but ICT is properly used to represent a broader list of all components related to computer and digital technologies (Tech Target, 2017).

3

1.2.2 Research Questions

- What are the differences1 between the Swedish Personal Data Act (PuL) and EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)?

-

How are ICT2 companies that process personal data within the Swedish market preparing for the upcoming General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)?1.3 State of the Art

To get an overview of the research area and to ensure that there is a relevant research gap to fill, a systematic literature review is conducted.

The chosen research area is new in the sense that it entails something that is currently happening in society and could not have been studied far back. As a result, there are relatively few scientific publications within this subject matter. This makes the research area favorably uncharted, providing many potential research gaps to fill. As of today, there is no full review of GDPR in relation to PuL. However, publications about GDPR and the general impacts and legal consequences within EU as whole can be found. Further, explicit parts of the Regulation have been studied which is noteworthy, but too specific and irrelevant to be included in our state of the art. As the Regulation comes into force, scientific research of the effects of GDPR will most likely increase, but as of today it is nearly non-existent.

In the article “The new European Union General Regulation on Data Protection and the legal consequences for institutions” a detailed examination of GDPR is made and the most significant practical applications are presented (Diaz, 2016). The study is based on an analysis of the legal framework established by the 1995 European Directive on Data Protection and it offers practical applications from the subject under obligation to issues for citizens, companies and the public sector (Diaz, 2016, p.207). They argue the value of GDPR by highlighting that the Regulation avoids fragmentation of the EU market and facilitates cross-border business, corporate activity and greater individual rights of European citizens (Diaz, 2016, p. 207). They list 10 several main innovations of GDPR and further discuss what practical applications this will entail. Adopting protectory measures according to the level of risk, better management of incidents related to cyber security and the implementation of legal and technical instruments that guarantee security, confidentiality and integrity of personal data is suggested as practical measures (Diaz, 2016, p. 232). It is further stated that technical advances are crucial and must go hand in hand with the identified practical measures (Diaz, 2016, p. 232).

What is common for all scientific publications of GDPR is that none are yet focused on examining the actual preparation or compliance state of specific company populations. This makes our research unique in the sense that it studies the GDPR-compliance of ICT companies pre GDPR.

1 By differences we mean both new additions and potentially removed legal requirements that does not get any equivalent meaning in the upcoming Regulation.

4

The interest in the preparations, challenges and effects of the GDPR can however be found amongst quite many studies performed on bachelor and master thesis levels. The purpose of acknowledging this is our need to be clear with the fact that our research ideas are not the first of its kind. We are aware of the lack of scientific significance of non-peer-reviewed publications, but we include it to fully cover what has already been done within the research area.

Previous research shows that knowledge about, and awareness of, the GDPR exists within media- and ICT-companies, but at the time of study the requirements are not yet implemented (Axelsson & Kidman, 2017). A difficulty in interpreting the new requirements is identified as one of the main challenges in preparing for the GDPR (Arkefeldt & Adolfsson 2017; Brädefors & Pettersson 2018; Lindstedt & Lång 2017). To successfully anchor GDPR within the organization and educate the employees is also identified as one of the central difficulties (Engberg & Höglund 2017; Erichsen & Månsson 2017). Adolfsson & Lundholm (2017) creates a requirement model as an instrument to measure and compare companies’ own perception of where they are in the preparatory work. The results indicate that the examined companies do not fully comply with the requirements of the GDPR (Adolfsson & Lundholm, 2017). Other findings suggest that companies do not have neither policies nor guidelines to be able to implement appropriate customizations (Gidlöf, 2017).

Common denominators for other research made on the GDPR is the fact that it is made at a stage where companies are still in a phase of figuring out the scope and meaning of GDPR. The findings are exposing the challenges and effects in a phase of preparation, where companies consider themselves to be too far away from the entry of GDPR to really be well-prepared. Today, with less than a month left until the law comes into force, the research conditions are different. This works in favor of the relevance and contribution of our research. Additionally, we aim to go deeper into specific parts of the implementation process to fully demonstrate the current level of compliance.

1.4 Disposition

The paper is presented as follows, section ‘2 Theoretical Background’ introduces the terms and definitions in which our research is based upon. Section ‘3 Methodology’ presents our mixed methods approach containing a comparative legal review and a survey data collection. In section ‘4 Results’, we present our research results distributed after qualitative and quantitative character. Thereafter, section ‘5 Analysis’ explains the significance of our findings by analyzing and interpreting the results. Section ‘6 Discussion’ contains our own speculations and ideas about the findings of our study. In section ‘7 Conclusion‘, the results and insights are put into context and the major contributions are presented. Lastly, suggestions to future work are presented in section ‘8 Future Research’.

5

2 Theoretical Background

The following sections introduces the terms and definitions in which our research is based upon in order to eliminate ambiguity of interpretations throughout the report. The purpose is to provide the essential theoretical background to assist further reading.

2.1 Personal Data

In the context of this paper we will use the following definition of personal data:

“personal data means any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (‘data subject’); an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier or to

one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that natural person. “

(EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, s. 33)

This definition includes many of the modern aspects of how personal data is used. Personal data includes all data that is collected from different type of sources, directly or indirectly. Directly means information such as name, home address, phone number and social security number (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 33). It is the data that can be uniquely used to identify an individual. Indirectly means information such as registration of user patterns in software that cannot by itself uniquely identify an individual (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 33). It may require the right complementary information or method. An example of this is GPS history. If a person daily uses a GPS that is connected to the Internet when driving to work, the GPS manufacturer can easily track this person. With this complementary information, it is possible to find out where the person lives, work and is doing on its spare time.

2.2 The Swedish Personal Data Act (PuL)

The Personal Data Act (PuL) is the current law for personal data protection within Sweden. It came into force 1998 and is founded on common rules decided within the European Union. The purpose of PuL is to protect individuals’ personal integrity when their personal data is being processed. It includes rules of how to collect, register, store, process, share and erase personal data within the Swedish market. The Act is largely based on the consent and information to the registrants, but also includes rules on the security and correction of incorrect data (Datainspektionen, 2018c). Companies, government agencies and other organizations are expected to assign data controllers who independently verify that personal data is processed correctly within the business (Datainspektionen, 2018c). Further, PuL separates structured data from unstructured data by applying more rules for data stored structurally, e.g. in databases.

6

2.3 The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

The GDPR replaces the previous Data Protection Directive from 1995. As the GDPR is a regulation, there is a difference in the enforcement required in comparison to the previous directive. A directive is a legislative act that sets out common goals for all the affected countries. In contrary, a regulation must be applied in its entirety and executed commonly by all that is affected (The European Union, 2018). The purpose of the GDPR is to enhance the protection of the individuals’ personal data. It is also an attempt to put individuals back in charge of their personal data.

As information technology is evolving, it is important that the legislation follows the same development. As a result, the GDPR focuses a lot of its different requirements on data that is processed and stored through modern technology.

2.4 Keywords

In this report, the following terms are used with the following meaning.

Term Definition

Data subject A natural person that can be identifiable indirectly or directly. For example, by an identifier such as a name, identification number, location data or any other factors specific to the cultural or social identify of that natural person (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 33).

Supervisory authority

Each member state in the EU shall provide for one or more independent public authorities for monitoring the application of the GDPR (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 65). In Sweden, the Supervisory authority is Datainspektionen.

Compliance ”the fact of obeying a particular law or rule, or of acting according to an agreement”

(Cambridge Dictionary, 2018a).

Violation ”an action that breaks a law, agreement, rule, etc.” (Cambridge Dictionary, 2018b)

7

3 Methodology

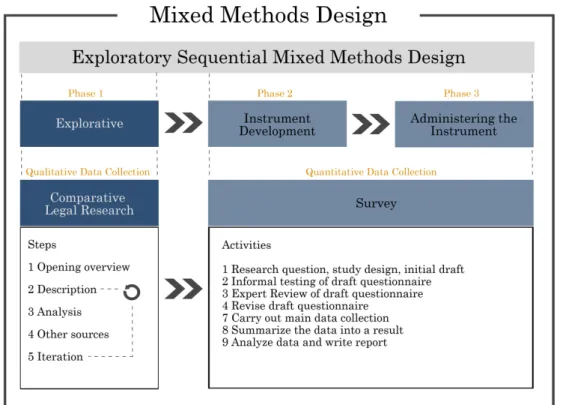

In the following section, three types of methodologies are introduced. The overall strategy of our research is a mixed methods design based on an exploratory sequential approach. The qualitative segment contains of a comparative legal research followed by a quantitative survey data collection. An introductory overview of the chosen methodology is presented below.

3.1 Mixed Methods Design

A research study with the combination of qualitative and quantitative research data goes under the term mixed methods design. Other terms also used for this approach are integrating, synthesis, multimethod and mixed methodology (Creswell, 2014, p. 217). By combining qualitative and quantitative data, you can achieve both open-ended and closed-ended responses (Creswell, 2014, p. 14). Under the assumption that each type of data collection has both limitations and strengths, we can reflect over how the strengths can be combined to reach a stronger understanding of our research problem (Creswell, 2014, p. 215). This means that if mixed data collections are used correctly, it can lead to a broader result than either data collection by itself. Mixed methods design includes the analysis of both forms of data which are integrated in the design through either merging, connecting or embedding the data (Creswell, 2014, p. 217). The procedures of our research could best be described as one data collection that builds upon another data collection which thereafter helps explain the original collection (Creswell, 2014, p. 15). In other words, our quantitative survey research builds upon the data collection of our qualitative comparative legal study. The type of mixed method design used in our research is the exploratory sequential mixed method which is introduced in the following section.

3.1.1 Exploratory Sequential Mixed Method Design

In an exploratory sequential mixed method, you start exploring with qualitative data and then use those findings in the upcoming quantitative segment (Creswell, 2014, p. 226). This approach can more specifically be divided into three phases; the exploratory, instrument development and administering the instrument to a sample population (Creswell, 2014, p. 226).

Exploratory

This is the first of the two data collections and it is performed through a comparative legal research. The comparison provides a result in which we can form categories of information that later can be explored in the quantitative phase (Creswell, 2014, p. 226). This will be further introduced in section ‘3.2 Comparative Legal Research’.

Instrument development

Based on the results of the qualitative data analysis we determine what findings to build on (Creswell, 2014, p. 227). The results generate guidelines for our survey and helps shape the design into becoming our ‘instrument’.

8

Administering the instrument

This is the second of the two data collections and it is performed by conducting a survey research on a selected sample population. The survey approach will be further introduced in section ‘3.3 Survey’.

3.1.2 Challenges

As with most strategy designs, several challenges and complexities arise with the multi-strategy approach. Using both qualitative and quantitative research strategies calls for an extensive data collection (Creswell, 2014, p. 218). Our research questions demand both types of data collections and it is the combination of the two that brings scientific value. To be able to achieve our research goal and answer our specific research questions, an extensive data collection is inevitable. This also leads to an expected time-intensive nature of analyzing both qualitative and quantitative data (Creswell, 2014, p. 218). Consequently, this is taken into consideration in the planning of our research schedule. Still, there are always a risk of potential timing issues due to the fact that qualitative and quantitative components sometimes have different time implications (Robson, 2011, p.166). As our quantitative data collection builds upon the qualitative data collection, completing the first collection and analysis is essential to move forward. This detail eliminates potential timing issues related to qualitative and quantitative data collections performed simultaneously.

Using a mixed methods design strategy also calls for a clear, visual model to understand the flow of research activities (Creswell, 2014, p. 219). To clarify the activity-flow we provide a visualization of the strategy from start to finish. This visual model is presented in Figure 1.

9

Another common concern among mixed method researchers is the lack of integration of findings. Responses indicate that only a small proportion of studies fully integrate both types of data collections when the research is written up (Robson, 2011, p.166). This calls for us researchers to have a clear sense of what we are trying to achieve, from practical strategy to the analytical linking of our data (Robson, 2011, p.167). These thoughts infuse our entire process.

3.2 Comparative Legal Research

The meaning of comparative legal research varies greatly. For that reason, defining the subject is necessary to facilitate further reading. In this research, comparative law involves the following, - comparisons of different legal systems with the aim of exploiting the similarities and differences (Bogdan, 2003, p. 18) and,

- processing of the identified similarities and differences (Bogdan, 2003, p. 18).

When embarking on comparative legal research, there is no agreed-upon overall methodology. Still, there are some recommendations for varying types of approaches that works well as a starting point. Mainly, it is the aim of the research and the research question that will determine which methods are suitable (Van Hoecke, 2015, p. 1).

A comparative process can be divided into three major stages, a) selection, b) description, and c) analysis (Dannemann, 2006, p.404). The chosen course of action is described in the following two subsections - Selection and Research Approach. The results of the comparison are presented separately in the results section ‘4.1 Comparative Legal Research’.

3.2.1 Selection

When conducting comparative research, it is still mainly about the comparison of national legal systems (Van Hoecke, 2015, p. 3). Different forms of globalization, such as Europeanization, challenges the very concept of ‘legal system’. In this research, the choice of comparison belongs to the European Union and the Swedish legal system. The subjects of assessment are the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Swedish Personal Data Act (PuL). To make a thorough comparative research, good reading knowledge of the local language is crucial (Van Hoecke, 2015, p. 4). The law texts to be assessed are both available in our native Swedish language. However, the English version of GDPR is used as support for making correct translations.

A meaningful comparison of two objects requires having some kind of common feature that works as the common denominator (Bogdan, 2003, p. 57). In this case, GDPR and PuL both deal with personal data protection. This means that they handle the same type of problem area and aim to regulate the same types of situations. For this reason, our focus will be on examining the differences and potential additions rather than the similarities. To do this type of comparison you must go further than examining terms and other abstract values (Bogdan, 2003, p. 58). More specifically, this comparison will focus on the functionality of the rules of the legal systems.

10

3.3.2 Review Approach

Before starting this comparative review, both law texts are carefully read. The two law texts differ in terms of structure and scope. GDPR holds 99 articles, followed by hierarchical lists using numerical and alphabetical classifications. PuL includes 51 paragraphs, occasionally followed by alphabetical classifications. The magnitude of the scope varies greatly amongst the documents, where GDPR is much more elaborate in its descriptions. Due to these differences, we consider it to be inappropriate to compare the two law texts chapter by chapter. There are simply not enough equal grounds for a chapter by chapter comparison.

Step 1 - Opening overview

Our starting point builds upon the differences identified by the Swedish Supervisory Authority (Datainspektionen, 2018a). This basis provides us with a clear, valid starting-point and works well as an opening overview of the main differences.

Step 2 - Description

In this descriptive stage, one will seek to find the differences in the description of legal institutions and rules (Dannemann, 2006, p. 412). The differences are one by one located in the GDPR and read thoroughly to provide a deeper understanding. To ensure that there is no equivalent in PuL, the document is examined for equivalents and resemblances.

Step 3 - Analysis

In this analytical stage, one will seek to find explanations for the differences (Dannemann, 2006, p. 416). The new additions and potential defaults are listed and presented by defining the term of the distinction and by specifying in what way it differs from previous legislation.

Step 4 and 5 - Other sources and iteration

To make sure that no differences are missed out, other valid sources are reviewed and analyzed to determine full coverage. Step 2 and 3 are repeated.

3.2.3 Method Discussion

An obvious risk with our comparison is the fact that one of the legal systems, the GDPR, is yet to come into force. This means that there is still much to come in terms of interpretations and actual effects. Comparing only legislation is risky when there is no information available on how it works in practice (Van Hoecke, 2015, p. 6). This makes our comparison both highly interpretive and predictive. Still, it can be considered necessary and of great value and interest for the future of personal privacy. Because without predictions and interpretations, we would not be able to prepare for the upcoming legislation.

Apart from the risks of incorrect assumptions, there is also a potential risk of us making misinterpretations when reviewing the legal documents. We aim to prevent that by thoroughly compare our results to valid sources of legal knowledge, such as the Swedish supervisory authority ‘Datainspektionen’. Still, describing law will never be an ‘objective’ activity offering ’pure facts’ (Van Hoecke, 2015, p. 27). This means that we initially always look at other legal

11

concepts at the background of our own legal system. The tertium comparatonis emphasizes the need to be aware of this potential bias and the aim to try to see beyond the own conceptual framework (Van Hoecke, 2015, p. 27). However, this warning against biases in comparative research, is developing towards being an inevitable part of comparative methods.

Furthermore, although there is no generally accepted definition of science when it comes to comparative research, it is still considered to be of a scientific nature when performed properly (Bogdan, 2003, p.23).

3.3 Survey

” There is a sense in which surveys are a research strategy (i.e. an overall approach to doing social research) rather than a tactic or specific method. In those terms a survey is a non-experimental fixed design, usually cross-sectional in type. However, many of the concerns in doing a survey are not so much

questions of overall strategic design but more with highly practical and tactical matters such as the detailed design of the instrument to be used (almost always a questionnaire, largely or wholly composed of

fixed-choice questions), the sample to be surveyed, and obtaining high response rates.”

(Robson, 2011, p.237f)

Our survey research uses an Internet-based questionnaire as the instrument to measure how companies that process personal data within the Swedish market are being affected by the upcoming regulation. The survey approach and its various parts are presented in the following sections.

3.3.1 Survey Approach

Inspired by Robson’s (2011) steps in carrying out a small-scale interview-based questionnaire (Robson, 2011, p.257), the following activities are conducted:

Activity Number of days

1. Research question, study design and initial draft of questionnaire 20

2. Informal testing of draft questionnaire 2

3. Expert review of draft questionnaire 4

4. Revise draft questionnaire 4

5. Carry out main data collection 7

6. Summarize the data into a result 5

7. Analyse the result and write report 18

Total 60 Since a survey using questionnaires by email differs from postal surveys in terms of estimated time-period, our time period is smaller than Robson’s (2011) suggested three to four months for the whole process (Robson, 2011, p.236).

12

3.3.2 Method Discussion

A substantial amount of surveys is considered academic in the sense that they are seeking to find out something about what is currently going on in our society. Hence, ‘getting it right’ is the superior goal, implicating accurate and unbiased evaluations of whatever it is being measured (Robson, 2011, p.236). Surveys provide a fairly simple and upfront approach to the study of attitudes, values, beliefs or motives and can be extremely efficient at providing large amounts of data (Robson, 2011, p.241).

Nevertheless, researchers tend to have different views about the place and importance of surveys. Some see the survey as the central real-world strategy, but concurrently it is associated with complex concerns about e.g. sampling, question-wording and answer-coding (Robson, 2011, p.239). These concerns lie heavily on those running the survey. Securing reliability and validity of the survey data of the respondents is a matter of internal validity (Robson, 2011, p.239). Incomprehensible or ambiguous questions is really a waste of time because they do not provide us with answers to what is currently going on in our society. In addition, there is a potential risk of external validity where the sampling is faulty and produces a generalizability that cannot represent the wider population (Robson, 2011, p.239).

Another potential issue is to generalize from what people say in a survey to what they actually do. There is a notorious lack of relation between attitude and behavior (Erwin, 2001). Not to forget, people might have a desire to be seen in a good light which can affect their true feelings, beliefs or behaviors (Robson, 2011, p.240). For us, this issue is really our most critical risk. Since our survey builds upon an upcoming EU legislation where it is illegal to not comply with the law, companies have a huge interest to be seen in a good light. To try to eliminate this critical aspect, we attach an introductory letter where we ensure the respondents that all information will remain confidential. Still, a self-administered Internet survey allows for an anonymity which can encourage frankness when sensitive areas are involved (Robson, 2011, p.241). That type of anonymity would not be possible if we would perform face-to-face interviews. The purpose and message of the letter can be found in section ‘3.3.3 Covering Letter’.

Ambiguities or misunderstandings of the questions being asked in the questionnaire are not always detected (Robson, 2011, p.241). To try to eliminate as many shortcomings as possible we performed an expert review on our initial draft questionnaire. More details of the expert review can be found in section ‘3.3.5 Expert Review’.

3.3.3 Covering Letter

The covering letter works as an invitation to participate in the survey. The letter introduces the main purpose and context of our research, the time required to complete the questionnaire and the requested deadline. Most importantly, it contains details regarding the assurance of confidentiality. It is of our greatest interest that the participants feel comfortable and confident in the processing and analysis of their answers. Without this reliance, there is a risk of getting a low response rate or biased answers (Ejlertsson, 2014, p.115).

The letter further emphasizes that no information will ever be associated with the respondent or the company that they represent. The covering letter can be seen in its full form under attachment ‘1.0 Covering Letter’.

13

3.3.4 Questionnaire

The first step towards formulating the questions is, based on the purpose and goal of the research, to find out what needs to be measured and how (Ejlertsson, 2014, p.47). Initially, problem areas are identified in accordance with the research question and the identified differences between PuL and the GDPR. Based on 10 problem areas, sub-areas are formulated. At this stage, the problem areas are ready to be operationalized and broken down into actual questions (Ejlertsson, 2014, p.47).

The questionnaire is administered as a self-completion survey where respondents fill in the answers themselves (Robson, 2011, p.243). This requires the questionnaire to be self-explanatory as there is no interviewer to explain instructions or questions (Robson, 2011, p.248). Short subject descriptions are therefore used as introductions to each category of the questionnaire. Although surveys usually rely on closed-ended questions (Robson, 2011, p.245), our questionnaire also holds some open-ended questions along with the possibility to add complementary comments. The questionnaire is structured into the following categories, order and format:

Category Number of questions Question format

1. General Information 2 Single choice

2. The Controller and Processor 8 Single choice

3. The Data Protection Officer 2 Single choice

4. Data Protection Impact Assessment 2 Single choice

Multiple choice

5. Consent 2 Single choice

Multiple choice

6. The Right to Be Forgotten 3 Single choice

Multiple choice

7. Data Portability 3 Single choice

8. Personal Data Breach 2 Single choice

Multiple choice

9. Data Protection by Design and by Default 7 Multiple choice

10. Administrative Fines 1

Total 32

Single choice

Too visit the online survey or read the questionnaire in its full form, see attachment ‘1.2 Questionnaire’.

14

3.3.5 Expert Review

To eliminate as many shortcomings as possible we perform an expert review on our initial draft questionnaire. The reviewer is an Information Security Expert working at an IT consulting company with establishments in five cities within the Swedish market. The expert is certified in:

- GDPR-compliance

- Advanced Computer Security - Ethical Hacking (CEH Certification)

The review is conducted online, where the expert is asked to provide us with as much in-depth feedback as possible. Along with the initial draft questionnaire, a short description of our research goal is presented to the expert. The expert feedback is provided to us via email, enabling the expert to have time to reflect over prevailing comments and criticism.

3.3.6 Case Selection

Our target population is ICT companies that process personal data on a daily basis within the Swedish market. Our research refers to a population in a general sense and is not limited to any specific ‘people’. Though it is impossible to be able to deal with the whole of our population, the use of a sample selection is in order (Robson, 2011, p.270).

Sampling within surveys is an important aspect of social research and is closely linked to the external validity or generalizability of the findings (Robson, 2011, p.270). Where the probability of the selection of each respondent is not known, you are not able to make any general assumptions or statistical inferences about your case selection. Conversely, these non-probability samples may still say something sensible about the population, just not on the same statistical grounds as a probability sample would (Robson, 2011, p.271).

For survey research, it is recommended to use fairly large numbers (Robson, 2011, p.128). Our sample size is 20 ICT companies randomly selected from the top 100 ICT companies based on revenue and size. All sample selections are acting within the Swedish market.

Responses are usually obtained from individuals, but an individual can respond on behalf of a group or organization (Robson, 2011, p.243). It is essential to us that someone with the appropriate knowledge answers the questionnaire. We target those individuals within the companies that either are responsible for personal data protection or actively work with GDPR-related issues. Although the response bias tends to be high on Internet surveys, it favors from more ‘educated’ respondents (Robson, 2011, p.245). The survey accuracy then relies on the skill and experience of those involved (Robson, 2011, p.274).

15

4 Results

In the following section, the results from our mixed methods design strategy are presented. Initially, we present the results of our comparative legal research. Thereafter, the results of our survey research are presented.

4.1 Comparative Legal Research

The results of our comparative legal research are categorized and labeled by the identified differences between PuL and the GDPR.

4.1.1 Fines

In the GDPR, penalties including administrative fines will now be imposed when there is a violation of the Regulation. The level of violation will be measured, and the fine will scale in relation to the magnitude of the violation. The fine will also depend on the turnover of the concerned authority. The maximum fine that can be enforced is 20 000 000 EUR, or 4% of the worldwide annual turnover of the authority (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, s. 83). This means that a regional breach will affect the company globally if the magnitude of the breach is high enough. It would require severe violation of the regulation to reach the maximum fine and at this stage there is not yet any defined guidelines of measuring the level of violation. In GDPR it is also mentioned that in case of minor infringements a fine will not be issued but rather a reprimand (Rush Files, 2017, p.13). When deciding the punishment, a case by case basis will be used. Some of the known measurements that will be considered during a violation, will be the willingness to cooperate with supervisory authority, intentionality and actions taken to reduce future violations (Rush Files, 2017, p.13).

When comparing the fine issued by GDPR and the current penalties of PuL, it is clear that the fines are not a replacement but rather a new addition (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 83). In PuL no predefined fine exists for severe violations. Instead, PuL suggests imprisonment followed by unspecified fines (PuL 49 § p. 14).

4.1.2 Documentation

In GDPR there is a big focus on documentation throughout the regulation. The concerned authorities will be required to have documentation that proves their compatibility with the regulation. The documentation includes information such as processes, technical systems and inventories of where personal data is located and processed. The importance of the documentation is that the concerned authority can by documentation prove their compliance (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 51f).

In PuL, requirements of documentation can be found in one of the paragraphs, but it is only mentioned at this one place. PuL suggests that the Supervisory Authority have the right at any time to request documentation regarding the processing of concerned personal data (PuL 43 § p. 13). In comparison to the GDPR there is no enforcement of the documentation requirement. As a result, this is one of the major changes because GDPR compliance is requiring that the documentation is in place.

16

An example of documentation required for a company could be when dealing with marketing. Today a lot of companies are using personal data for marketing purposes. It can be in the shape of data collection, directional marketing or making automated decisions. After the 25th of May, the companies that is still using this type of data processing, must make sure to also have documentation in place. The key importance for this is to proof compliance to GDPR and make it easier for the data subject to obtain all the data processed by the company if required.

4.1.3 Consent

The consent within GDPR is always referred to the consent of the data subject. It means that the data subject must give consent by free will. The consent must also be given in a clear and affirmative way that by no means can be ambiguous to the data subject (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 34).

Consent by itself is not new in comparison to PuL. The consent of the data subject is not as strictly defined in PuL as it is in the GDPR. In PuL, the focus of the definition lies within the data subjects consent of approving that his or her data will be used. This represents a major difference. In the GDPR, it is not only the consent itself being highlighted, but the efforts in making sure that the data subject is completely aware of the consent given.

This means that it will be a lot tougher for parties to hide the information of personal data processing within the small prints of an agreement or declaration. The GDPR is compelling that if a consent should be given within a context of a written declaration or agreement, it must be clear and distinguishable from the rest of the content (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 37). Any agreement that is not following this regulation shall not be binding.

In addition to the new conditions of consent, the GDPR is differentiating the consent given by an adult compared to a child. To protect the younger generation there will now exist a minimum age requirement to give the consent of personal data processing. The consent of processing personal data of a child is only lawful if the child is at least 16 years. If the child is below the age of 16 years the consent to process the personal data of the child must be given by the holder of parental responsibility (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 37).

4.1.4 The Right to Be Forgotten

According to the GDPR, a data subject has the right to have his or her personal data erased and therefore no longer processed under certain circumstances. The right to be forgotten is also known as ‘the right to erasure’ which probably provides a much better visual of what the principle entails (Rush Files, 2017). The right to be forgotten is not absolute, but it can be used by the data subject where processing of personal data in any way does not comply with the Regulation. The controller is obliged to erase personal data without unreasonable delay when a data subject makes a justified request (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 43). However, there are some exceptions where the data subject’s rights can be overridden by the public interest. These are in case of archiving purposes such as scientific or historical research and statistical purposes (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 29).

The right to be forgotten is considered a new addition due to its more elaborate specification. The right is granted at any of the following circumstances:

17

- when the personal data no longer is necessary in relation to the purpose for which it was originally collected (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 43a.).

- at withdrawn consent (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 44b).

- when a data subject objects to the processing and the company does not have an overriding legitimate ground (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 43c).

- at unlawfully processed personal data (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 43d).

- when an erasure is necessary to comply with a legal obligation (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 43e). - if personal data is processed in relation to the offer of information society services to a

child (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 43f).

Nevertheless, there are some similarities between the current Personal Data Act (PuL) and the GDPR. PuL also covers the obligation of the data controller to erase personal data which has not been treated in accordance with this Act or regulations issued under the Act (PuL 28 § p. 9). At withdrawn consent by the data subject, PuL requires a cessation of the processing of personal data (PuL 12 § p. 5) but the GDPR takes it further by requiring the controller to physically erase it (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 12). The data subject does not even have to put forth any particular reasons to substantiate their request (Rush Files, 2017). If there is no legitimate reason to process the personal data of a subject, the company must delete it immediately. Considering the massive scope of personal data and how many single files just one data subject could carry, the extent of the consequences is potentially massive (Rush Files, 2017). This means that companies need to have their routines in order and be able to manage this right to erasure in both time, quantity and with the right technical means.

4.1.5 Data Portability

Article 20 (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 45) provides the data subject with the right to receive and transmit personal data concerning him or her. This addition of the GDPR requires the controller to be able to deliver the data in a structured, machine-readable format without any technical hindrances. This means that data controllers should be encouraged to develop interoperable formats that enable this type of data portability (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 13). Furthermore, it should not oblige the controllers to adopt or maintain processing systems which are technically compatible. The right to data portability shall also be without prejudice to the right to be forgotten and shall not apply where the processing is necessary for the public interest (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 29).

The data portability of the GDPR is a completely new addition to legal personal privacy, no equivalent can be found in PuL. The right to data portability provides the data subject with the right to obtain and reuse personal data for their own purposes on different services and platforms (Rush Files, 2017).

4.1.6 The Controller and Processor

The role of the controller and processor remains in the GDPR. The controller is the legal person who controls the purpose and the personal data being processed, while the processor is an organization that processes personal data on behalf of the controller, i.e. a data supplier (24 Solutions, 2017). The role of the processor is changing in terms of a significantly increased responsibility and accountability (Datainspektionen, 2018b). Nonetheless, this does not entail

18

that the responsibility of the controller in any way diminishes. Instead, what solely used to be the responsibility of the controller is now evenly distributed amongst the different data processors (Datainspektionen, 2018b). The major changes for the role of the processor are the requirements to:

- maintain a record of processing activities under its responsibility (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 50). The record shall contain name, contact details, processing purpose, category description and recipients, third country transfers and where possible erasure time limits with technical and organizational security measures (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 51).

- cooperate with the supervisory authority on their request (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 51).

- implement appropriate technical and organizational measures to ensure a level of processing security (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 51). This could entail pseudonymisation, encryption, the assurance of ongoing confidentiality, integrity and availability and the ability to restore values and regularly test and assess its effectiveness (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 52).

- without undue delay notify personal data breaches to the supervisory authority and to the concerned data subject (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 52).

- assist the controller in the fulfillment of its obligation to respond to requests and ensure regulation compliance (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 49).

- be accountable for potential administrative fines or reprimands for infringement of the Regulation (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 27).

- use contracts authorized by the controller to assign processors (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 49). In reality, this requires the processor to have enough knowledge about personal data privacy to get support and authority to be able to perform its mission in an efficient and independent manner (Datainspektionen, 2018b). Due to the risk of suffering great individual fines and reprimands, the changing accountability also implies the importance to have clear routines of where in the organization such reporting obligation should be (Datainspektionen, 2018b).

4.1.7 The Data Protection Officer

The role of a Data Protection Officer (DPO) differs from the role of the controller and the processor. A DPO is not always required but when it is, it is designated by the controller and the processor. All public authorities and bodies that process personal data shall assign this role, but courts acting in their judicial capacity is exempted from this requirement (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 55).

Companies that systematically and regularly process personal data to a large extent and scale is entitled to assign a DPO (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 55). Large organizations with multi-location operations can use the same officer for all locations, but it is important that both size and organizational structure is taken into account (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 55). Since the data protection officer is required to monitor compliance with the Regulation, give advice to controllers and cooperate with the supervisory authorities, expert knowledge of the data protection officer is essential. The DPO shall also work as the main contact for data subjects regarding all issues related to processing of their personal data and exercise of their rights under the Regulation (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 56). It is also considered fundamental that the DPO is working under secrecy or confidentiality regarding the performance of his or her tasks, and that those duties do not result in any conflict of interests (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 56).

The role of the DPO within the GDPR is a completely new addition to legal personal privacy. No equivalent can be found in PuL.

19

4.1.8 Data Protection Impact Assessment

To maintain security and prevent unlawful processing of personal data, the controller or the processor needs to evaluate the risks of the data management beforehand (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 16). To enhance compliance with the Regulation, a data protection impact assessment should be carried-out. Such assessment should evaluate the origin, nature, particularity and severity of the potential risks (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 16). The assessment shall contain a description of the purpose and legitimate interest of the processing, the necessity and proportionality in relation to the purposes and lastly, the measures envisaged to address the risks (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 54). The result of the assessment should then be used to make decisions regarding appropriate security measures. In practice, this means the higher the risk the higher the technical and organizational measures. In the case of a high risk where there is an uncertainty regarding the company’s ability to maintain lawful processing, the controller shall consult the supervisory authority prior to the processing (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 16). A data protection impact assessment is particularly required in the case of:

- systematic and extensive evaluations of personal aspects based on automated processing (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 53).

- large scale processing of data within specified categories; revealing racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, trade union membership, genetic data, biometric data, data concerning health or sexual orientation (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 53). - systematic monitoring of a public area on a large scale (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 53).

The meaning of this part of the Regulation is a new addition due to the fact that PuL never required any risk or impact assessments. PuL mentions the “particular risks” involved with processing personal data” (PuL 28 § p. 9) but never specifies what those are or how and when they should be assessed.

4.1.9 Personal Data Breach

A personal data breach is a breach of security leading to accidental or unlawful destruction, loss, alteration or unauthorized access to personal data (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 34). In the case of such a breach, it is the controller’s responsibility to, within 72 hours of becoming aware of it, notify it to the supervisory authority (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 52). If notifications to the supervisory authority is made later than 72 hours, there must be legitimate reasons for the delay.

Likewise, a personal data breach needs to be communicated to the concerned data subject, without undue delay and in a clear and plain language (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 53). The requirement to report data breaches is introduced to help prevent data subjects from suffering; limitation of their rights, discrimination, identity theft or fraud, financial loss, unauthorized reversal of pseudonymisation, damage to reputation, loss of confidentiality or any other significant economic or social disadvantage (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 16). A personal data breach communicated to the concerned data subject should contain:

- the nature of the breach, including the concerned data category (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 52).

- name and contact details of the DPO (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 52). - a description of the likely consequences (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 52).

20

The obligation to report personal data breaches does not exist in PuL and is therefore considered one of the differences. PuL mentions an obligation to report automated processing of personal data before processing (PuL 28 § p. 14), but never suggest any potential consequences for infringements.

4.1.10 Data Protection by Design and by Default

When developing, selecting, designing and using applications, services and products that process personal data, the right to data protection should influence the decision-making. The controller should adopt internal policies and implement privacy design and default measures to be able to demonstrate compliance with the Regulation (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 15). Costs, the nature, scope, context and processing purposes as well as the likelihood and severity of imposed rights should determine what technical and organizational measures to implement (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 48). Such measures could for example be pseudonymisation or data minimization, where data protection principles are integrated and provide necessary safeguards (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 48). Data privacy by design and by default also requires the controller to implement appropriate measures to make sure that only personal data which are necessary for a specific purpose are processed. This obligation includes the amount of data collected, the extent of the processing, the time-period of the storage as well as the accessibility (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 48). In practice, this means that personal data should not be made accessible without the individual’s intervention to an indefinite number of persons.

Data protection by design and by default is a completely new addition within the GDPR. The new legislation places greater demands on the privacy protection throughout the entire life cycle, from the gathering of requirements to the development and actual usage. It is common for security and data privacy protection to be added afterwards, when you realize that you need it, but this will not be accepted by the new Regulation (24 Solutions, 2017). The new legislation provides a protection for the data subject by requiring strict privacy settings to be active per default rather than configured manually (24 Solutions, 2017).

4.1.10 The Rule of Misconduct

The rule of misconduct from PuL contains simplified rules of how to process unstructured personal data. In the GDPR no difference is made between structured and unstructured personal data (Datainspektionen, 2018d). For this reason, the rule of misconduct is not necessary anymore.

21

4.2 Survey Result

The results of our survey research are categorized and labeled by the identified differences between PuL and the GDPR. Our findings are reported in charts with complementary text.

28

5 Analysis

As presented in the current state of the art there are no previous peer-reviewed research on the GDPR and the preparation of Regulation compliance, to our knowledge. As there are no scientifically valid research results to associate our results with, no legitimate comparisons can be made. The following section therefore only contains comparisons between our findings and the legislation of the GDPR.

All the companies participating in the survey are working for GDPR compliance. Generally, the companies have worked for GDPR compliance between 6 and 24 months, while only a few companies have worked with the GDPR for a shorter period than 6 months (Diagram 1). This implies that work towards GDPR compliance is a priority for all participating companies and no companies are overlooking the importance of the upcoming Regulation.

A majority of the participating companies always maintain a record of personal data processing activities (Diagram 3) which indicates a full level of compliance (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p.50). However, 20% of the participating companies very often maintain a record (Diagram 3). This indicates that the companies are progressing in their work towards full compliance, but still has work left to be able to always maintain records of personal data processing activities. 25% of the companies sometimes or rarely maintain records (Diagram 3) which shows a low level of GDPR compliance. Even though a majority are well prepared, there is a significant amount of companies that are not completely prepared to meet the requirements of the GDPR.

A significant majority of the participating companies always have a clear process that enables them to cooperate with the supervisory authority on their request (Diagram 4) which indicates a high level of preparation to cooperate with the supervisory authority (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p.51). 25% of the companies does not always have a clear process. A significant majority of the participating companies always have a clear process that enables them to notify personal data breaches to the supervisory authority 35% of the companies does not always have a clear process to notify personal data breaches to the supervisory authority (Diagram 6). This means that the companies’ processes are not always clearly defined. However, to be compliant you do not need to have a clear process, only be able to cooperate with or notify the supervisory authority when needed (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p.52). Additionally, not having a clear process for cooperation or notification strongly indicates that these companies are not fully prepared for the upcoming Regulation at this stage.

65% of the participating companies always ensure a level of processing security by implementing appropriate technical and organizational measures (Diagram 5). This shows that a majority of the companies are compliant and prepared with the appropriate technical and organizational measures. 25% very often ensure a level of processing security which indicates that they still prepare aiming for full compliance.

For processes regarding notification of personal data breaches to the concerned data subject (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p.52), the companies do not have as clear processes as towards the supervisory authority. This clearly implies that there are differences in the prioritization between individuals and governmental authorities. In this case, only 45% of the companies have a clear process to notify personal data breaches to the concerned data subject (Diagram 7). Processors assisting the controller in the fulfillment of its obligation to respond to requests and ensure regulation compliance is something that is managed by 75% of the participating

29

companies at all times or very often (Diagram 8). This result shows that a majority of the participating companies suit the requirements of having processors assisting the controllers in their obligations(EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 49). Concurrently, 20% of the participating companies state that they do not know if they do (Diagram 8). These 20% implies an undoubtful level of uncertainty and absence of GDPR compliance.

Contracts authorized by the controller to assign processors, is used by 65% of the companies either very often or always (Diagram 9). This suggests that a majority of the participating companies have the appropriate groundwork to be able to fulfill the GDPR contract requirements (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 49). Still, some of the participating companies only use contracts sometimes or never which clearly points out shortages in their preparatory work. Additionally, it is noteworthy that 15% of the participating companies states that they do not know whether they use contracts or not (Diagram 9). This result strongly shows an uncertainty and insufficiency of their compliance.

60% of the participating companies have already assigned a Data Protection Officer while 25% are not obliged to do so (Diagram 10). Something that is remarkable is the fact that 15% of the companies say that they intend to assign a Data Protection Officer (Diagram 10). This is noteworthy due to the fact that the enforcement of the Regulation is weeks away and all companies that are obliged to have a DPO should have assigned one by now (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 55). This indicates a certain lack of readiness and preparation.

40% of the participating companies have performed Data Protection Impact Assessments (Diagram 11). As this is one of the requirements that evaluates the overall data protection (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 16), the companies that have completed DPIA’s are therefore considered well-prepared. The remaining 60% intend to perform DPIA’s or do not know what they are. This indicates a lack of readiness since performing DPIA’s are considered a mandatory process in order to measure and enhance data protection compliance.

The DPIA’s that are performed by the participating companies includes many of the requirements of what a DPIA should contain. The spread between the different alternatives is very even. The companies include a description of the necessity and proportionality, the legitimate interest and the measures envisaged to address the risks (EUT L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 54). These answers show that the participating companies use several of the required descriptions which indicates a high level of compliance and preparation. A description of the purpose of the processing stands out slightly. With its 87,5% (Diagram 12), it shows us that the purpose of the processing is the part that the companies prioritize the most in a DPIA.

30% of the participating companies do not need to take any action to achieve the requirement for the consent of their data subjects (Diagram 13). This shows that almost a third of the companies have prepared sufficiently to achieve the GDPR’s consent compliance. 70% of the companies takes action to send out additional information to obtain the required consent (Diagram 13). As the Regulation was approved in 2016, companies have had almost two years to collect consent from their data subjects. This indicates that the participating companies at this stage are not yet prepared and do not achieve full compliance. A possible justification can be the uncertainty within the companies of whether their previous purpose of processing had a legitimate consent or not.

When the participating companies receive a consent from a data subject, 80% keep documentation of how the personal data is allowed to be processed (Diagram 14). This shows that this specific topic is the most important for the companies along with documenting when the consent was collected.