Virtuous circles between innovations, job quality and

employment in Europe? Case study evidence from the

manufacturing sector, private and public service sector

Karen Jaehrling (ed.)

with contributions from

Roland Ahlstrand, Susanne Boethius, Laura Corchado, Nuria Fernández, Jérome

Gautié, Anne Green, Miklós Iléssy, Maarten Keune, Bas Koene, Erich Latniak,

Csaba Makó, Fuensanta Martín, Chris Mathieu, Coralie Perez, Dominik Postels,

Filip Rehnström, Sally Wright and Chris Warhurst

January, 2018

Work Package 6: Qualitative Analysis Deliverable D 6.3

QuInnE – Quality of jobs and Innovation generated Employment outcomes – is an interdisciplinary project investigating how job quality and innovation mutually impact each other, and the effects this has on job creation and the quality of these job.

The project is running from April 2015 through March 2018. The QuInnE project is financed by the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 Programme ‘EURO-2-2014 - The European growth agenda’, project reference number: 649497.

Quinne project brings together a multidisciplinary team of experts from nine partner institutions across seven European countries.

Project partners:

CEPREMAP (Centre Pour la Recherche Economique et ses Applications), France Institute of Sociology of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Hungary

Lund University, Sweden Malmö University, Sweden

University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany University Rotterdam, The Netherlands University of Salamanca, Spain

Contents

CHAPTER 1 – Introduction: Prospects for Virtuous Circles? The institutional and economic

embeddedness of companies’ contemporary innovation strategies in Europe ... 1 Karen Jaehrling

CHAPTER 2 – Innovation, Job Quality and Employment Outcomes in the Aerospace Industry: Evidence from France, Sweden and the UK ... 35

Jérôme Gautié, Roland Ahlstrand, Anne Green and Sally Wright

CHAPTER 3 – The relationship between employment, job quality and innovation in the automotive Industry: a nexus of changing dynamics along the value chain. Evidence from Hungary and Germany 88

Csaba Makó, Miklós Illéssy and Erich Latniak

with the support of András Bórbely, Angelika Kümmerling, David Losónci, Anna F. Tóth and Ibolya Szentesi

CHAPTER 4 – Innovation, Job Quality and Employment Outcomes in the Agri-food Industry: Evidence from Hungary and Spain ... 128

Fuensanta Martín, Nuria Corchado, Laura Fernández, Miklós Illéssy and Csaba Makó with the support of Mariann Benke, Mónika Gubányi and Ákos Kálman

CHAPTER 5 – Digitalisation and Artificial Intelligence: the New Face of the Retail Banking Sector. Evidence from France and Spain ... 178

Coralie Perez and Fuensanta Martín

with the support of Nuria Corchado and Laura Fernández

CHAPTER 6 – Innovation and Job Quality in the Games Industry in Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden and the UK ... 231

Maarten Keune, Noëlle Payton, Wike Been, Anne Green, Chris Mathieu, Dominik Postels, Filip Rehnström, Chris Warhurst and Sally Wright

CHAPTER 7 – The digitisation of warehousing work. Innovations, employment and job quality in French, German and Dutch retail logistics companies ... 278

Karen Jaehrling, Jérome Gautié, Maarten Keune, Bas Koene and Coralie Perez

CHAPTER 8 – Innovation, Job Quality and Employment Outcomes in Care: Evidence from Hungary, the Netherlands and the UK ... 331

Anne Green, Miklós Illéssy, B.A.S Koene, Csaba Makó and Sally Wright

with the support of Claudia Balhuizen, Jolien Oosting, László Patyán and Anna Mária Tróbert

CHAPTER 9 – Innovation, Job Quality and Employment in Hospitals in Spain and Sweden ... 385 Chris Mathieu, Susanne Boethius and Fuensanta Martín

1

CHAPTER 1 – Introduction: Prospects for Virtuous Circles? The

institutional and economic embeddedness of companies’ contemporary

innovation strategies in Europe

Karen Jaehrling

1 Interrelationships between innovations and the world of work ... 2

1.1 ‘Virtuous circles’ between innovations and inclusive employment systems ... 2

1.2 Organisational prerequisites for innovation at the company level ... 5

1.3 Power relations and current economic trends and structures as important contextual conditions for innovation dynamics ... 6

1.4 Virtuous circles: prospects and research questions ... 9

2 Research design and analytical approach ... 10

2.1 Selection of industries and company cases ... 12

2.2 Case study methods ... 14

3 Overview on chapters: key issues and findings ... 15

3.1 Aerospace industry ... 16 3.2 Automotive Industry ... 18 3.3 Agri-food industry ... 20 3.4 Banking industry ... 21 3.5 Computer Games ... 23 3.6 Retail logistics ... 25 3.7 Care... 27 3.8 Hospitals ... 28 4 References ... 31

1

Advanced capitalist economies currently face ‘disruptive’ innovations that profoundly challenge existing market structures and business models. Most notably, a new generation of digital technologies and a more general trend towards the ‘digital economy’ are expected to revolutionise the production and consumption of goods and services across industries, such as through advanced robotics and the industrial internet in the manufacturing sector, or FinTechs in the banking and finance sector.

Although radical innovations are not new, their current apparent ubiquity across industries and countries raises concerns and questions about their cumulative impact on labour markets. Even if they may point to their overall long-term benefits, assessments on the transformational power of these technological innovations have tended to highlight their potential to undermine the very fundaments of work and society ‘as we know it’. The potential consequences include large-scale job losses linked to the substitution of human labour by machines (Brynjolfsson and McAfee, 2012; Frey and Osborne, 2013). Unlike the ‘skill-biased technological change’ theorem, which predicts that job losses will be concentrated among low-skilled employees, it is assumed that the new technologies will replace many ‘low-skilled’ routine tasks and thereby affect a much broader share of the workforce. With regard to the remaining jobs, the re-casualisation of labour as well as sustained attacks on employment status in the ‘gig economy’ are expected to gain speed and scope; some even predict the end of paid employment and of market-based transactions due to the spread of networked prosumerism and the sharing economy in the ‘collaborative commons’ (Rifkin, 2014).

The merit in such projections into the future lies in raising awareness of the potential benefits, risks and challenges and the need for action in order to manage these changes in a socially sustainable way, thereby trying to turn the ‘race against the machine’ into a ‘race with the machine’ (Brynjolfsson and McAfee, 2014). Despite a general commitment to the almost commonsensical view that technology is not a “destiny”, the specific role attributed to policies and society is often rather narrow. Policy recommendations by Brynjolfsson and McAfee, for instance, focus primarily on adapting the institutional framework to the projected future by providing the necessary human capital resources – for example through immigration policies that allow ‘talents' from the periphery to access the centres of globalised capitalism; through policies that promote entrepreneurship and basic research; or through an overhaul of the education system in order to produce the kind of flexible, creative, problem-solving thinking needed as a complementary resource to the machines.

It is this reductionist view of the role of policies and of society at large, among others, that has seen these projections face a lot of criticism for their inherent technological determinism and a resulting overestimation of the scale, scope and pace of change. In the economic and social sciences a much broader range of economic, institutional and societal factors has come to be considered as shaping the adoption, design and implementation of technologies, thereby mitigating their potentially negative impact. Pointing to experiences with earlier waves of computerisation and the diffusion of information and communications technologies (ICTs), researchers have, for instance, questioned the assumption of a direct causal link between technological innovations and increased productivity gains (Valenduc and Vendramin, 2016), or highlighted the way in which technologies are shaped through their uses, and how this in turn depends on contextual factors and on the power, preferences and perceptions of a broad diversity of actors (e.g. Holtgrewe, 2014).

The debate about disruptive innovations has thus revitalised both public policy and academic interest in the interrelationships between innovations and the world of work. These interrelationships lie at the heart of this working paper. As illustrated above, many contributions to the current debate are either future

2

projections based on generalisations from new phenomena considered as emblematic (e.g. crowdwork), or an analysis of and extrapolation from past experiences. By contrast, there is little empirical evidence on contemporary innovation dynamics and how they interact with employment systems. The working paper seeks to fill this gap by investigating the relationship between innovation, job quality, employment, social inclusion and inequality at the firm level, based on comparative case study research in seven European countries (Sweden, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Hungary, the Netherlands and Spain). This introductory chapter briefly revisits core arguments and findings from research on the institutional and economic embeddedness of innovations (1), before presenting the analytical approach and methods (2). The final section provides an overview of key issues and findings (3), which will be presented in more detail in the eight industry chapters that constitute the core of this working paper.

1

Interrelationships between innovations and the world of work

The institutional and economic embeddedness of innovations has been at the core of several strands of literature. Many of them, for instance the ‘National Innovation Systems (NIS) approach (Lundvall, 1992; Nelson, 1993)’, or the ‘societal effects’ school (Maurice et al., 1986; Maurice and Sorge, 2000), have focused on the micro-dynamics of knowledge building and learning activities at the firm level and the rootedness of innovation strategies in national education and training systems. One of the key findings has been that certain forms of work organisation are more conducive to individual and organisational learning and hence are an important element of a firms’ ‘innovative capacity’; and that the dominant modes of work organisation are linked to national education and training systems.

The ‘Varieties of Capitalism’ (VOC) approach has additionally highlighted the role played by the overall institutional framework and organisational patterns in orchestrating the competitive strategies of companies. This includes corporate governance modes, inter-firm relations, as well as laws and institutionalised patterns of conflict regulation with regard to extrinsic aspects of job quality, i.e. wages, working time and job security. In this account, strong employment protection, multi-employer collective bargaining and other institutional features of coordinated market economies would prepare the ground for ‘incremental innovations’ benefiting the market position of companies in certain industries, whereas the institutional framework in liberal market economies would be geared towards ‘radical innovations’ and provide them with competitive advantages in other industries (Hall and Soskice, 2001).

1.1

‘Virtuous circles’ between innovations and inclusive employment systems

The assumption of a ‘virtuous circle’ or a complementary relationship between innovations and institutions safeguarding employee interests is contrary to an assumption in neo-classical economics that strong trade unions, for example, may impede innovation as they reduce incentives for employers to invest in innovations because high wage increases divert too much of the productivity gains (‘hold-up problem’) – an assumption that has often failed to be confirmed by empirical research (e.g. Addison et al. 2013; Kleinknecht et al. 2014). Streeck (1997) has even described the institutional framework in coordinated market economies as a source of ‘beneficial constraints’. From this perspective, high levels of wages, strong trade unions and employment protection may work to the benefit of both economic performance and job quality in various ways. They may, for example, weaken worker resistance to the introduction of new technologies and enable employees to accumulate the tacit knowledge required for ‘incremental innovations’. Furthermore, they may reduce turnover and related costs, thereby creating incentives for firms to invest in training, and support relationships of trust, thereby enhancing knowledge sharing and reducing transaction costs. Finally, union-imposed obligations on employers to improve working

3

conditions may change the way in which new technologies are deployed on the shop floor. Taken together, “a set of constraints of this kind may virtuously move the production profile of a company, industry or economy towards more demanding markets that can sustain both high wages and high profits” (Streeck, 1997, p. 204).

The viability as well as the distributive effects of this kind of ‘virtuous circle’ has, however, since been questioned by many empirical and theoretical contributions.

Distributive effects of virtuous circles?

“Beneficial to whom?” asks Wright in his critique, and points out that “the optimal level of institutional constraints (…) might be systematically different for different categories of actors” (Wright, 2004, p. 410), thereby emphasising conflicts of interest and the importance of power relations between classes. Hence, “enlightenment of the capital class to their long-term interests in a strong civic culture of obligation and trust” will not be sufficient, since even the long-term interests of shareholders and managers may be different from those of employees. Moreover, critical analyses of company-level pacts for employment have called attention to potentially differential benefits within classes: even if employee representatives are involved in restructuring and innovation processes and help to develop alternatives to, for example, staff reductions at company level, this might partly be traded off against disadvantages for more vulnerable groups of the workforce, thereby reinforcing labour market segmentation or ‘dualisation’ (e.g. Hassel 2014). Another distributive dimension – the distribution between countries – is addressed by Hancké (2013). According to him “beneficial constraints within one [the German, K.J.] economy produced perverse external effects” and reinforced the effects of the financial crisis starting in 2008.

Diverse and hybrid virtuous circles

Apart from the critiques relating to the potentially selective and biased benefits of virtuous circles (where they exist), the empirical prevalence of these stylised national models of mutually reinforcing, complementary relationships between the institutional framework, innovation patterns, job quality and competitive advantages in certain industries have been called into question by a number of empirical findings. They reflect the fact that this theory was generated from studies examining the restructuring of manufacturing industries in a few selected coordinated market economies during the 1980s and 1990s. Studies focusing on different industries and countries and on more recent developments have provided ample evidence of sectoral and regional models of capitalism (and systems of innovation) that deviate from the national models (e.g. Crouch et al., 2004, Kirchner et al., 2012). Researchers have also questioned the alleged affinity of liberal market economies with radical innovations, arguing that certain features regarded as paradigmatic for coordinated market economies, such as long-term obligational forms of coordination both within and between firms, might be a necessary condition for radical innovations in some industries (Allen et al., 2011). In a similar vein, Witt and Jackson (2016) find some empirical support for their hypothesis that competitive advantages result from certain combinations of conflicting institutional logics, i.e. non-market and market institutions, rather than from the self-reinforcing institutional coherence emphasised by the standard VOC literature. These hybrid institutional configurations can be “beneficial for dealing with radical innovation by providing for both flexibility in restructuring of economic organisation as well as trust and coordination to solve problems of asymmetric information or hold-up.“ (Witt and Jackson, 2016: 784). It is worth recalling that, in this analysis (which refers to the period up until 2003), company-level pacts for employment figure as one example of the successful recombination of ‘liberal’ and ‘coordinated’ institutions. The positive effect of company-level pacts on innovativeness, competitiveness and wages is partly confirmed by empirical research (Addison et

4

al. 2015), while other studies have found few if any effects (e.g. on investment in training, see Bellmann and Gerner, 2012) or, as mentioned above, have called into question the distributive effects of such pacts (see Rehder, 2003; 2012; Hassel, 2014). Thus it is a contested issue whether in fact mixed institutional configurations necessarily combine ‘the best of two worlds of capitalism’, so to speak.

The empirical relevance and competitiveness of ‘hybrid’ or mixed institutional configurations were also revealed by analyses of foreign investors’ strategies in the new member states of the European Union. Comparing two Volkswagen automotive assembly plants in Germany and Hungary, Keune and co-authors (2009) highlight how the institutional settings of the multinational corporation’s home country were successfully adopted by the Hungarian subsidiary; this points to the capacity of multinational companies (MNCs) to “mould” the institutional framework (Keune et al., 2009, p. 114). According to Allen and Aldred (2009), foreign investors do in fact shape the innovation dynamics in new member states. However, they argue that “domestic institutions play an important role in shaping the competitive strengths of firms” in these countries as well so they cannot be easily subsumed into the group of ‘dependent market economies’ (Allen and Aldred, 2009, p. 593).

Erosion of institutional prerequisites for virtuous circles

While these studies have provided a more nuanced picture of the broad range of diverse institutional configurations that shape innovation patterns and firms’ competitive strategies, more fundamental doubts about the significance of any ‘coordinated’ institutions arise from studies pointing to their limited reach. Studies of the retail industry, for instance, have shown that the introduction of information technology-based automation led to higher service productivity but did little to improve wages, work organisation or training, either in the US (Bernhardt, 1999) or in European coordinated market economies (Carré et al., 2010). A likely part of the explanation is that the institutional framework of coordinated market economies has never had the same strength and influence in private service industries. Furthermore, the liberalisation of product markets, globalisation and financialisation have created challenges for the functioning of ‘beneficial constraints’, even in the core manufacturing sectors of coordinated market economies, as they have increased the exit options available to owners of capital and contributed to the erosion of ‘patient capital’, among other things (Scharpf, 2006). On a more general note, several scholars have highlighted how financialisation of the economy has also weakened coherent institutional complementarities in liberal market economies, by breaking the mechanisms of exchange and trust, and the ‘implicit contracts’ (Appelbaum et al., 2013) between management and employees that previously under laid business models in these countries (see also Thompson, 2003). Moreover, in view of the increasing shift from inclusive to exclusive employment systems (Gallie, 2007), it could be argued that the workplace-based prerequisites for incremental innovation are potentially disappearing, because an increasing share of workers are not or are only partially covered by the protective institutions that previously characterised coordinated market economies. In line with the assumption of a complementary relationship, the incentive for companies to invest in training and to adopt a form of work organisation that supports incremental innovation and thereby helps to sustains ‘high wages and high profits’ would probably decrease as well.

One possible conclusion could be that the erosion of ‘beneficial constraints’ even in the last protected corners of coordinated market economies facilitates the adoption of radical innovations and helps companies to stay competitive in the contemporary ‘disruptive’ age. However, the mere absence or weakness of (non-market) institutional constraints is not a sufficient condition for innovation, nor does it establish a ‘level playing field’ for companies and make them converge towards similar competitive

5

strategies, innovation patterns or employment relationships. Rather, these are also shaped by economic dynamics and structures, as well as by organisational prerequisites at the firm level.

1.2

Organisational prerequisites for innovation at the company level

While the legal foundations and power resources supporting the enforcement of workplace characteristics favourable to incremental innovations seem to be in decline, paradoxically an ever broader range of academic literature and management philosophies has long been lauding the benefits of ‘high performance workplaces’, which in a similar way are assumed to reconcile competitiveness, innovation and job quality. For instance, an essential element of the Japanese Kaizen philosophy, which found its way into American and Western European management strategies through the ‘lean’ approach (Womack et al. 1990), is its emphasis on employee involvement in decision-making, team work and job rotation as means of ensuring greater flexibility and commitment in the workforce and harnessing their tacit knowledge and problem-solving skills. In a similar vein, empirical and conceptual contributions to the literature on national innovation systems (NIS) have underscored the importance of an experience-based, ‘doing-using-interacting (DUI)’ mode of innovation that “can be intentionally fostered by building structures and relationships, which enhance and utilise learning by doing, using and interacting. In particular, organisational practices such as project teams, problem-solving groups, and job and task rotation, which promote learning and knowledge exchange, can contribute positively to innovation performance.” (Jensen et al. 2007: 684).

There is also a strong overlap with other concepts such as ‘high involvement work practices’ (Ichniowsky et al., 1996); ‘high performance work systems’ (Appelbaum et al., 2000), ‘high involvement innovation’ (Bessant, 2003), ‘employee-driven innovation’ (Høyrup et al, 2012) and ‘workplace innovation’ (Oeijs et al., 2017). Their origins can partly be traced back to concepts and policy programmes that long preceded the diffusion of ‘lean’ principles but succeeded in infiltrating management thinking and innovation policies and guidelines on a broader scale around the same time as lean principles, i.e. from the mid-1990s onwards, at both national and supranational level (see Brödner and Latniak, 2003; Alasoini, 2009; Totterdill, 2016; Pot et al., 2017 for Europe, Kochan et al., 2013 for the US; see also the QuInnE Working Paper by Csaba et al. 2016 for a critical evaluation of current European innovation policies). The common thread running through all these concepts is that both job quality and the innovation capacity and competitiveness of companies require participatory practices suited to developing and leveraging creativity, individual and collective learning at all levels of the organisation, thereby generating a complementary resource to technological innovations.

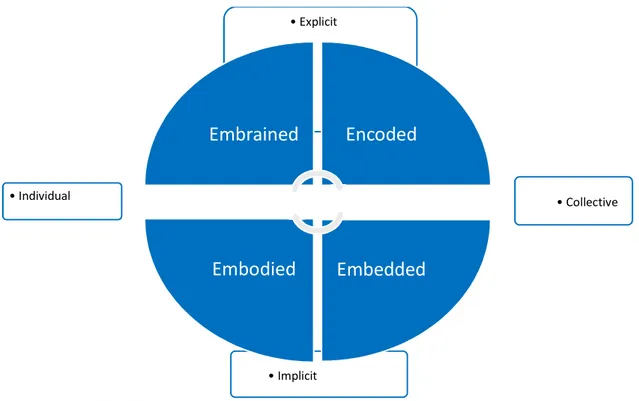

It might be expected that an almost hegemonic consensus of this kind would result in the widespread uptake of such practices. To the extent that management subscribes to these ideas they may be a possible source to compensate for the increasing weakness of the institutional foundations of virtuous circles. The empirical evidence is, however, mixed. On the one hand, survey results clearly indicate that, while the share of Taylorist organisations remains high in some sectors and countries, many firms have moved away from Taylorist forms of work organisation towards organisational practices suited to enhancing learning and problem-solving. On the other hand, empirical and conceptual studies have established that these organisational practices vary considerably from each other and that different types of organisational learning need to be distinguished in order to adequately capture the “institutionalised variation in organisational learning” (Lam, 2000). Based on a cluster analysis of employee survey data, Lorenz and Valeyre (2005) for instance have identified two models that are associated with strong learning dynamics and rely on employees’ contributions to problem-solving; they call them the ‘learning’ and the ‘lean’ models. Compared with the ‘learning’ model, however, the ‘lean’ model is characterised by relatively low

6

levels of autonomy in work and the use of tight quantitative production norms to monitor employee effort. These two models are diffused unevenly across European countries, with the learning model most prevalent in the Netherlands and the Nordic countries, and the ‘lean’ model most prevalent in the UK and Spain and to a lesser extent in France. The two models also correspond to distinct HRM practices around training and extrinsic factors of job satisfaction such as job security and pay (Lorenz and Valeyre, 2005). Further research established that they also correlate with distinct innovation patterns: Arundel et al. (2007) find evidence that the ‘lean’ model is more highly correlated with technology adoption, while the ‘learning’ or ‘discretionary learning’ model is more conducive to “in-house innovation activities that lead to the creation of new-to-the-market innovations and possibly radical innovations” (Arundel et al., 2007: 22).

Although these studies, in part, explicitly refer to the VOC approach in order to explain country differences in the prevalence of the ‘discretionary’ model’, their findings actually contradict a core assumption of VOC, i.e. that the institutional setting in liberal market economies is more favourable to radical innovations. On the contrary indeed, “relatively well-developed systems of employer coordination around matters of pay and vocational training constitute a favourable institutional setting for establishing learning forms of work organisation characterised by high levels of employee competence and autonomy at all levels of the organisational structure”. (Lorenz and Valeyre, 2005). Further contributions additionally link the ‘learning’ model to less ‘elitist’ national education systems (Lam, 2000) or else to more generous systems of unemployment protection, as the latter are assumed to support the inter-firm mobility of professionals on whose expert knowledge the ‘learning’ model relies to a certain extent (Lorenz and Lundvall, 2011; Lorenz, 2015). Finally, the persistence of adverse ”historically inherited management-worker relations” and low levels of generalised trust in a society (Arundel et al., 2007) are considered to be further possible obstacles. Taken together, these factors might help to explain both country differences and the overall stagnation or even decreases in the diffusion of discretionary learning modes across countries (Lundvall, 2012).

Thus compared to studies in the VOC tradition, those that adopt the NIS approach place greater emphasis on the micro-level aspects of work organisation and provide a more detailed framework for analysing the mechanisms through which innovations are generated. They also take into account additional factors, such as cultural ones, that impact on these mechanisms. Like studies in the VOC tradition, however, they see non-market, ‘coordinated’ institutions as important levers for the kind of organisational practices that are regarded as a “key to genuinely sustainable competitive advantage” (Totterdill et al., 2016: 64) – albeit with one important difference. Namely, their findings suggest that incremental innovations based on the mobilisation of tacit knowledge are in practice not a separate mode of innovation but a complementary resource to radical innovations. By implication, the erosion of non-market institutions would not free companies from institutional constraints detrimental to ‘radical innovations’ but rather dry up an important source of enabling factors.

With their primary focus on cross-country comparisons, however, there has been comparatively little research in this body of literature on changes in the institutional and economic context in which innovations and job quality are embedded.

1.3

Power relations and current economic trends and structures as important contextual

conditions for innovation dynamics

What is largely absent in the analyses discussed in the previous section is the role played by recent economic trends, and by power relations both between and within firms. For instance, changes in

7

industrial relations systems, financialisation of economies or the restructuring of value chains are hardly taken into account as factors potentially explaining the uneven, and in some cases sluggish, diffusion of ‘discretionary learning’ practices. Arguably, the quality of management-labour relations, the extent of a firm’s shareholder value orientation or the degree of interdependence and power characterising the relationship between a lead firm and its suppliers might be difficult to capture in quantitative surveys, on which these studies primarily relied. On the other hand, these issues have figured prominently in qualitative industry and company case studies of technological change and their interaction with employment systems.

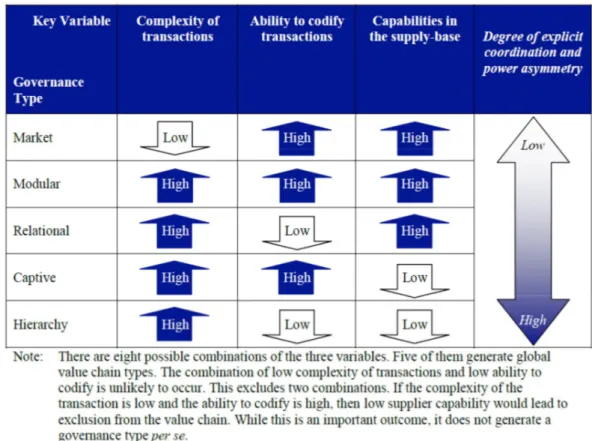

The way in which inter-firm relations impact on the innovation-employment-job quality nexus was highlighted by studies adopting the ‘societal analysis’ approach. As Sorge and Maurice (1990) show in their analysis of the different business strategies among French and German machine tool firms with regard to new CNC technology, the differences can partly be explained by differences in customer requirements – large industrial plants in France versus smaller firms in Germany – and the relative status of firms vis-à-vis their customers. This angle has been developed more systematically by the ‘global value chains (GVC)’ body of literature (e.g. Gereffi et al. 2005; Huws, 2006). The growing importance of multinational corporations and the increasingly international division of labour in the production of goods and (more recently) services have focused greater attention on the different characteristics of these inter-firm relationships and how they impact on the competitive strategies of firms. Building on the key insight “that coordination and control of global-scale production systems, despite their complexity, can be achieved without direct ownership” (Gereffi et al., 2005: 81), that is through networks rather than vertically integrated transnational firms, the GVC literature develops more fine-grained analytical tools in order to describe the nature of transactions and coordination in these networks of firms.The dichotomous distinction between producer and buyer-driven value chains1 soon proved insufficient in capturing the

complexity and variety of governance modes that have developed as a result of several economic trends facilitated and triggered not least by advanced ICT (Gereffi 2001). In the networked forms of value chains, besides legal and financial or economic power (depending on ownership structures), transactions are shaped by the uneven distribution of “functional power” which “tends to be more and more concentrated in the hands of the customer, through the establishment of a wide and increasing variety of specific contract regulations such as vendor contracts, service level agreements, quality control certification, competence certifications, etc.” (Ramioul and Huws, 2009: 28). This is also corroborated by the industry analyses below

While Gereffi and co-authors (2005) and others in the GVC body of literature have focused mainly on global value chains in the manufacturing sector and how this impacts on firms’ competitive strategies, other researchers have developed the concept further, with a view to also analysing the different power and control mechanisms governing domestic value chains, including in the public and private service sector (cf. in particular Huws, 2006 and Huws et al., 2009). Moreover, they focus on how power relations between firms have more or less direct consequences for employment relations and working conditions within each firm, depending on the firm’s position in the value chain (Flecker et al. 2009). However, the value chain is not viewed as a static system but rather as a dynamic system that allows firms to move up and down, with

1 The aerospace and the automotive industry have for a long time been regarded as examples of the

‘producer-driven’ type of value chain characterised by vertical integration by transnational corporations based on ownership and control; while the food value chain was regarded as an example for the buyer driven chain, based on global sourcing networks established by large retailers and pure marketers (which build and commercialise their own brand names, but own neither factories nor stores).

8

possible effects on job quality (Flecker et al. 2009: 78). The analyses assembled in Huws and co-authors (2009) (based on the EU-financed WORKS project) also show that value chain restructuring not only encompasses external realignments (for example, off-shoring, out-sourcing), but also continuous processes of internal reorganisation, including the conversion of business units into separate profit centres, or ‘internal outsourcing’ into separate subsidiaries.

The focus of the WORKS project was predominantly on the effects on work organisation, job quality and industrial relations, less so on the innovative capacity of firms. However, the study still addresses interactions with innovations by examining the part played by advanced information and communication technology (ICT) as well as workers’ knowledge in the overall process of value chain restructuring. Advanced ICTs in this account both enable and drive the development of ever more complex and spatially distributed value chains, by facilitating the codification of knowledge and thereby the integration of business partners outside the organisational boundaries of the firm. Value chain restructuring is also closely interconnected to other product or process innovations which trigger changes in the labour division both between and within firms. The joint effect of these trends is found to be the increasing standardisation and formalisation of skills and tacit knowledge (Greenan et al., 2009; Ramioul and De Vroom, 2009). In the case of process innovations “tacit knowledge is made explicit and extracted from the individual worker to become the collective property of the team or the private property of the employer or customer; and ‘skills’ are disembodied from the workers who have traditionally exercised them” (Ramioul and Huws, 2009: 30). This assessment resonates with and explicitly refers to the classic Labour Process Theory (LPT) (Braverman, 1974), which was developed on the basis of an analysis of the functioning and effects of Taylorist production. Classical LPT sees innovations essentially as means to increase management control of the labour process, thereby enhancing productivity but leading to a deskilling of jobs and a degradation of job quality. Thus the greater knowledge intensity that now characterises economic activity is not necessarily accompanied by a change in the organising principles underlying restructuring, according to this perspective. Even though most pronounced for low-skilled jobs – which are therefore most likely to be either outsourced or substituted by technology – the organisational case studies from the WORKS project aim to show that the standardisation of knowledge stretches across all skill levels and business functions (such as R&D, customer service, IT services). This can also help to explain the overall decrease in work complexity found in survey-based analyses, i.e. declining levels of discretion with regard to the pace and methods of work and declining weight of problem-solving tasks (Greenan et al., 2009). Skilled labour and tacit knowledge do not invariably decrease though, not least because new functions and work roles are needed for inter-organisation transactions in the value chain (Flecker et al., 2009). Moreover, moving up the value chain by developing higher value-added services may increase skill requirements at the company level. However, as Ramioul and Dahlmann point out, even for those parts of the business function that have increased skill requirements the ‘learning’ organisation is not a necessary corollary. The case studies rather point to “contradictory pressures, such as the speeding up of business processes and the shortened time to market of product innovation“. “Furthermore, increased performance monitoring and control systems (such as scripts and procedures) accompanying new value chain structures, supported by ICT, may limit the opportunities employees get to use and develop their professional skills.“

As mentioned above, there is a strong overlap, both with regard to analytical concepts and empirical findings, between these studies and more recent ones following in the footsteps of LPT (see contributions assembled in Briken et al, 2017). As Pfeiffer (2017) shows, for instance, opportunities for improved job quality associated with advanced manufacturing systems fail to materialise, as in practice such systems

9

are predominantly oriented towards rationalisation and standardisation. In attempting to explain the limited spread of high performance work practices, labour process scholars have recently pointed in particular to the financialisation of the economy, i.e. an increasing concentration of capital, the power of new financial institutions such as private equity funds and the predominant focus of management on short-term performance and shareholder value (Thompson 2003; 2013). These factors exert contradictory pressures on firms, creating tensions not only between management and labour, but also between lower and higher management levels. “Local, unit and functional managers were tasked with responsibility for pursuing high performance from labour, but they ultimately lacked the capacity to sustain the enabling conditions. (…) Such disconnections and their largely negative consequences for innovation and stability at firm level and for opportunity and security for labour belie the optimistic promises of a new stable and progressive settlement associated with post-Fordist and related perspectives such as the knowledge economy or informational capitalism.” (Thompson, 2013). Still, as Kochan and co-authors (2013) aim to show, even financial investors are well advised and might be persuaded that fostering high performance workplaces is in their best own interests – or to pick up Wrights’ dictum, they might be ‘enlightened to their long-term interest’, to the extent that they have long-term interests.

A common thread and a core takeaway lesson from these studies is the importance of the competitive economic environment in which innovation strategies operate, and more specifically the power relations both between and within firms. This is seen as an important factor that limits the spread of certain workplace characteristics beneficial to both job quality and innovation capacity. GVC and LPT studies likewise share the view (as do other strands of research discussed above) that companies still largely depend on employees’ tacit knowledge and experience and that, besides the potential divergence of interests between employees and management, this is a source of constant tension between diverging principles or logics, namely “more learning and autonomy versus more control and less complexity” (Ramioul and De Vroom, 2009, p. 53). As Briken and co-authors (2017b: 5) note, the view of the “workplace as a contested terrain” also restrains authors from advancing deterministic arguments about the impact of innovations in conjunction with economic trends.

1.4

Virtuous circles: prospects and research questions

In sum, several signs point to an undermining of the institutional foundations supporting a virtuous circle that – at least in some countries and industries – has helped to reconcile innovation dynamics and inclusive employment systems. One possible conclusion could be that the erosion of ‘beneficial constraints’ facilitates the development and adoption of radical innovations and helps companies to stay competitive in the contemporary age of ‘disruptive’ innovations. There is, however, a broadly shared understanding across different disciplines and professional contexts that the mere absence of non-market constraints is not conducive to any innovation. Instead, both theoretical-conceptual considerations and empirical findings suggest that certain workplace characteristics are required – which in part at least seem to be anchored also in non-market institutional constraints. Recent economic trends like financialisation and value chain restructuring can be identified as factors that run counter to the proliferation of these workplace practices, despite a broad awareness, at the normative level, of their potential benefits for both job quality and innovativeness.

Merely pointing to persisting discrepancies between theory and practice, however, would miss the more relevant takeaway lesson that also informed the empirical research assembled in this Working Paper. This literature review seeks to highlight the interplay of contradictory drivers of change and the need to take them into account when investigating our core research question, which is, how and why companies currently do (or do not) succeed in reconciling innovation with ‘more, better and inclusive jobs’. Under

10

what conditions and through what mechanisms can innovation capacity, employment and job quality support each other in a productive way? What factors and dynamics tend to block such a ‘virtuous circle’? Based on the available empirical evidence we can certainly assume that powerful ideas about the benefits of high performance work practices are themselves one of the drivers of change. But how do they interact with recent changes in the institutional and economic context in which companies’ innovation activities are embedded, such as the financial crisis in 2008, the resulting constraints on public budgets, the ongoing dynamics of value chain restructuring, the deregulation of labour markets, or societal changes like the ageing workforce and the increasing inclusion of women into the labour market?

As we will see, the findings presented in the industry chapters below are, to varying degrees, linked to the different theoretical approaches touched upon in this overview, depending on the disciplinary background of the researchers involved as well as on the specific characteristics and dynamics present in each industry. What these analyses share, however, is an awareness of the diverse factors that may either support or inhibit ‘virtuous circles’. Moreover, while many of the studies discussed in this overview primarily focus on intrinsic dimensions of job quality, the industry studies below take a comprehensive view on job quality, encompassing both intrinsic and extrinsic aspects, following a multi-dimensional definition of job quality that was adopted for the QuInnE project (based on Davoine et al. 2008 and Munos de Bustillo et al. 2011)2.

Finally, they seek to shed light on the inclusiveness (or otherwise) of virtuous circles. The potentially uneven distribution of the benefits of ‘virtuous circles’ has been touched upon in parts of the literature (see 1.2) but has so far been rather neglected in empirical research. As noted in the QuInnE operational guide, ‘high performance’ work practices may be implemented in a selective way. For example, they may be restricted to those with relatively high skills, thereby “sharpening the polarisation between an elite stratum of ‘knowledge’ workers and the lower skilled” (Warhurst et al., 2016). An important research question therefore is whether a spread of innovation-conducive workplaces (in conjunction with other trends) helps to reduce or rather accentuates long-standing social differentials in work (by age, gender, skills, nationality) or whether it is largely neutral to these inequalities.

2

Research design and analytical approach

The working paper investigates the relationship between innovation, job quality, employment, social inclusion and inequality at the firm level in eight different industries (aerospace, automotive, agri-food, banking, computer games, retail logistics, social care and health care), based on comparative case study research in seven participant countries (France, Germany, Hungary, Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom) (see Table 1 below). This comparative setting allows us to explore the extent to which different regulatory constraints and economic contexts in the countries and industries under investigation result in different organisational strategies.

The inclusion of a range of different industries as well as the focus on industry-specific innovation dynamics have several implications. Firstly, the types of innovations studied in this working paper are more varied than in analyses that focus on certain technologies (advanced ICTs) or on specific types of innovations (radical). The industry analyses cover the whole spectrum of innovations distinguished by the Oslo manual (OECD/Eurostat 2005) – thus both technological innovations (either product or process innovations), as

2 The definition includes six dimensions of job quality: wages, employment quality (e.g. job security), education

and training, working conditions (e.g. individual discretion, work intensity), work-life balance and consultative participation and collective representation.

11

well as non-technological innovations (including organisational and marketing innovations) 3. While this

heterogeneity narrows down the empirical basis for each of the innovations studied and thus imposes constraints on generalisability, this approach was best suited to the purpose of our study. In line with the literature and with the overall approach of the QuInnE project, we assume that organisational innovations are of particular importance, particularly from the point of view of job quality. Moreover, they are of considerable empirical relevance, not only in the sense that they are increasingly recognised as being either a necessary prerequisite, corollary or consequence of technological innovations, but also as key innovations in their own right, particularly (but not solely) in service sector industries. The inclusion of incremental innovations is also in line with the overall approach of the QuInnE project, which seeks to transcend a rather narrow focus on the ‘science, technology and innovation’ (STI) mode of innovation that makes use of codified scientific and technical knowledge through research and development (R&D) and interactions with research institutions; to pay particular attention to the ‘doing, using, interacting’ (DUI) mode of innovation (Jensen et al. 2007).

A second feature that sets our approach apart from other studies that have focused on particular innovations is the particular attention we pay to factors in play at the meso-economic industry level. Such factors are acknowledged in the literature as being of crucial importance. Factors impacting on both innovation dynamics (such as demand conditions, company structures, technological regimes or innovation policies) and those directly affecting job quality (such as the industrial relations system) vary between industries at least as much or even more than between countries (e.g. Malerba, 2005; Bechter et al., 2011).

Thirdly, and related, the primary goal of this investigation is to generate fresh empirical knowledge on how job quality and inclusiveness are changing and how such changes might be related to innovation dynamics. That is, rather than analysing how a particular innovation changes certain aspects of job quality, while leaving aside other, potentially more important dynamics that are impacting on job quality as well. This requires us to systematically take into account the broad set of other factors affecting job quality – either in close conjunction with, or independently of – innovation dynamics. This holistic design is a typical feature of qualitative case study research and fully exploits its strengths, namely that it accounts for the multitude of historically contingent, simultaneous trends. It is widely acknowledged that the strength of quantitative research lies in isolating and measuring the effects of a single factor (e.g. a certain innovation), whereas case study research is best suited to identifying and describing the mechanisms of causal relations (i.e. ‘why and how’ these effects are generated) (e.g. Gerring, 2007). Another, less frequently acknowledged advantage of case study research is that it opens up opportunities to identify and describe what happens when diverse and potentially unrelated trends come together at one place and one point in time and to assess their cumulative impact. This is an advantage the QuInnE case study research seeks to exploit. To give an example: instead of trying to isolate the impact of an organisational innovation, such as the introduction of ‘scrum’ methods in a computer games developer studio, preferably by comparing it with similar firms who have not yet introduced scrum, the approach adopted for this

3 The classification of the Oslo manual distinguishes between four different types of innovations (cf OECD/Eurostat

2005: 53ff). Product innovations involve new or significantly improved goods and services Process innovations represent significant changes in production and service delivery methods. Organisational innovations refer to the implementation of new organisational methods, such as changes in business practices, in workplace organisation or in the firm’s external relations. Finally, Marketing innovations involve the implementation of new marketing methods, including changes in product design and packaging or in methods for pricing goods and services.

12

project is to study how this organisational innovation interacts with other related or unrelated factors that shape job quality in this industry and to consider their cumulative impact on job quality. Thus, in addition to the kind of complementary relationships that many of the theoretical approaches discussed above focus on, case study research also needs to be sensitive to possible co-incidences, i.e. the simultaneous impact of different factors (e.g. tax subsidies for research and development on the one hand and labour market regulation on the other hand) affecting job quality and innovations independently from each other, or a co-evolution whereby the same factor impacts on job quality and innovation, but in a largely unrelated way (see figure 1). To give a hypothetical example for the latter, an ageing population can, for instance, benefit both job quality and innovation, as it may force firms to make workplaces more sustainable (+ job quality) and at the same time incentivise firms to develop innovative services and products tailored to the needs of ageing customers (+innovation).

Figure 1: Potential causal relationships between innovation, job quality and institutional, economic an societal constraints

Coincidence

dependent on different factors

Co-evolution

Dependent on same factors, but not interdependent

Complementary relationship

(Inter)dependence, mutual reinforcement

Source: own elaboration

2.1

Selection of industries and company cases

The selection of industries was motivated by a number of aims. Firstly, to not solely focus on manufacturing but to also include public and private sector service industries. Secondly, to include industries with different skill structures and social composition of the workforce, so as to be able to investigate the inclusiveness of innovation/job quality interrelationships, as explained above. Relatedly, the industry selection also sought to include industries with both higher and lower levels of aggregate job quality, as well as both higher and lower levels of innovations. The final decision about which industries to study in which of the seven participating countries was informed both by statistics on innovation intensity and job quality made available by the Work Package 5 of the QuInnE project, as well as by desk-based research and consultations with national stakeholders via workshops and interviews. Taken together, this information provided valuable intelligence and assessments on the industries that would be most interesting to study, due to their relevance for the respective national economy and in light of current dynamics thought likely to have an impact on the job quality/innovation nexus. The original research design envisaged the selection of four industries, each to be studied in at least three countries. Ultimately, in order to reach a more balanced sample of industries that took into account the above selection criteria, it was decided to increase the number of industries studied from four to eight and to for each industry to be studied in at least two countries. The resulting sample is shown in table 1 below.

Labour Market Reg. Tax subsidies for R&D JQ IN IN JQ IN JQ Training systems Ageing population

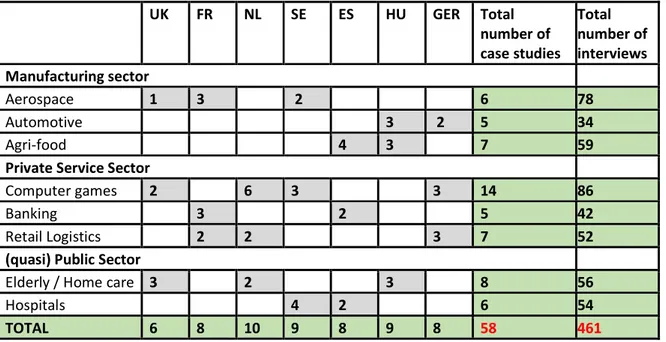

13 Table 1: Sample of industries and countries, number of case studies and interviews

UK FR NL SE ES HU GER Total number of case studies Total number of interviews Manufacturing sector Aerospace 1 3 2 6 78 Automotive 3 2 5 34 Agri-food 4 3 7 59

Private Service Sector

Computer games 2 6 3 3 14 86

Banking 3 2 5 42

Retail Logistics 2 2 3 7 52

(quasi) Public Sector

Elderly / Home care 3 2 3 8 56

Hospitals 4 2 6 54

TOTAL 6 8 10 9 8 9 8 58 461

According to the clustering of industries by job quality and technological innovation, as provided by WP5, the selected industries spread across three of the four cluster types (see table below). The ‘high job quality – low innovation’ cluster is not represented. It should be kept in mind that the table below only covers technological innovation (due to the absence of data in the EWCS on organisational innovation).

Table 2: Relationship between job quality and technological innovation

Innovation

Low High

Job Quality Low Food production (A1; C10); Care (Q88)

Retail logistics (H52; H53)

High Hospitals (Q 86); Aerospace (C30), Car

Manufacturing (C29), Computer Games (J58); Banking (K95)

Source: EWCS (based on data provided by WP5, see also Erhel and Guergoat-Larivière, 2016). The numbers in brackets refer to the NACE codes that include the respective industries under study

The rationale for selecting the case studies in each industry is explained in the relevant industry chapters. As a general rule, however, the selection criteria was chosen on the basis of characteristics that were reasonably expected to ‘make a difference’ for the investigated issue. In our case, the selection criteria should make a difference to the innovation/job quality nexus. Criteria chosen for the selection of cases were decided by each cross-national industry team, based on national industry profiles on competitive structures, current innovation dynamics and job quality written beforehand. These industry profiles were in turn based on relevant literature, available statistics and interviews with industry experts. In order to exploit the analytical potential of the comparative method, the sample of cases was selected in order to be as similar as possible between the countries. At the same time, consideration was given to the different business structures in the selected countries. For instance, while in one country, there may be

14

predominantly large firms operating in the selected market segment, it may be almost exclusively SMEs in another country – in which case selecting comanies based on firm size would neither be feasible nor appropriate. The industry teams therefore needed to agree on the appropriate selection criteria, depending on the relevant features in the particular industry.

2.2

Case study methods

Case study research is particularly appropriate for studying a contemporary phenomenon (‘the case’) within its real-world context (Yin, 2009, p. 16). A first important step in case study design is thus to define the social, spatial and temporal boundaries of the case, as well as the relevant context conditions. This primarily depends on the research questions and propositions. Our investigation seeks to contribute to a better understanding of organisations’ recent and upcoming decisions on innovation and job quality related issues, and of the interplay of these decisions and their outcome with regard to employment, job quality and inclusiveness. Our ‘cases’ are thus not certain types of innovations but companies or more generally organisational units that produce goods or services. The majority of the selected cases are indeed legally independent companies; however, in several instances a focus on organisational units within a larger company (e.g. an in-house warehouse of a large logistics company, a hospital ward) was more appropriate in order to narrow down the broad variety of innovation processes to be studied; and in other instances, where production processes are typically strongly networked, as in the computer games industry, a case could also include freelancers working for a company or be a network of self-employed workers cooperating in temporary projects. With regard to the relevant context conditions, as spelled out above, the innovation and job quality related strategies of these organisational units are both enabled and constrained by their institutional environment, their position in the value chain, by their organisational context (if part of a larger company) and by support from infrastructures and institutions at the regional, sectoral, national or international level. In order to capture the impact of this ‘real-world’ context, research for each case study included, firstly, desk-based research in order to retrieve as much information on these contextual conditions for the company or organisational unit under study beforehand. Secondly, in addition to the interviews at company level – with managers, employees and employee representatives – the fieldwork included interviews with representatives from this wider context, for example trade unions and business organisations, public administration, or research institutions. These interviews are included in the total number of interviews listed in Table 1. Thirdly, a semi-structured thematic protocol was jointly developed to guide the interviews and subsequently, to be used as the intial basis for the case study report. The protocol included a broad range of questions aimed at identifying the broad range of possibilities that embed companies’ innovation strategies

Wherever interviewees gave their consent, interviews were recorded and transcribed and supplemented by documents and statistics, available media reports and expert interviews. These materials were thematically coded along the questions defined beforehand and emerging issues and written up as case study reports. As mentioned above, for the purpose of comparability between cases, the interview guidelines and the case study reports followed a common protocol that was developed jointly and finalised after a first set of pilot case studies in a few industries.

A common concern about case study research is its apparent limits to generalise findings based on a few cases only. However, as Yin (2009, p. 21) notes, case studies are in principle generalisable to theoretical propositions (analytic generalisations), not to populations, as in quantitative research (statistical generalisations). Thus the findings do not allow us for example to make any assumptions about how many organisations in the same market segment or industry are characterised by similar innovation-job quality interlinkages as those identified in the organisations under study. They however do allow for more general

15

conclusions about the conditions that support these particular interlinkages, provided that researchers take the necessary precautions when seeking to establish the causal relationships for their particular case (internal validity) – for example by considering rival explanations – and when reflecting on whether findings are generalisable beyond the particular case (external validity) – for instance by comparing the findings to earlier research and theoretical propositions. The latter task was most importantly assumed by the author teams who wrote up the cross-case analyses in the industry chapters below. There are however two inevitable limits to generalisability that are linked to the boundaries of the cases and therefore need to be noted here: the first is to do with the temporal boundaries: The time span that we were able to observe was often shorter than some of the causal relationships discussed, as recent and current innovations only deploy their impact over the longer term. This leaves us with open questions and merely preliminary conclusions into which directions job quality, employment and inclusiveness will ultimately evolve – even more so with a view to the constant adjustment processes observed in the cases under study (see next section) . Secondly, by focusing on single organisations we’re studying micro-economic effects of the interaction between job quality and innovation, not the effects at the macro-level. There might be quite successful models that are beneficial to the market position of a firm and to secure jobs in this organisation; yet whether this translates into beneficial effects (on innovativeness, job quality, competitiveness) at the macro-level is another question.

3

Overview on chapters: key issues and findings

The industry analyses below illustrate the broad variety of strategies that companies adopt in dealing with the diverse challenges brought about by technological changes, customer demands and societal needs, labour market as well as competitive structures in their respective industries. They also shed light on the variety of reasons why companies opt for organisational changes geared towards fostering individual and organisational learning and making better use of employees’ knowledge and skills. The dynamics in value chain restructuring are an important factor here. A number of case studies from various industries, for instance, show how companies’ innovation strategies (including workplace innovations) are motivated by the aim to improve their position in the value chain by developing higher value added products and services. Another recurrent finding is the importance of skill and labour shortages, not only for high skilled, but also for medium and, to some extent, even lower skilled occupations: When labour markets are tight, employers are likely to be incentivised to improve job quality in order to attract and retain scarce workers; hence they can be a key driver behind companies’ efforts to improve both intrinsic and extrinsic determinants of job quality. However, the incentives inherent in the broader economic context are neither uni-directional nor necessarily strong enough to channel company strategies unambiguously in the direction of ‘high performance work systems’. In fact, few occupational and regional labour markets are characterised by skill shortages; and strong cost pressures imposed by dominant players in the value chain can also trap companies in price-competitive strategies that come along with Taylorist or hierarchical ‘Lean’ forms of work organisation.

Companies however do not neatly fall into two or three distinct types of strategies. Our argument here is however not that reality is more complex and requires more nuanced typologies in order to adequately describe them. Rather, the point we want to make here, and perhaps the most important contribution of these qualitative analyses, is that they shed light on the contradictory effects – a) of diverse factors on job quality and innovations; b) of one and the same factor on innovations and job quality, and c) of one and the same innovation on job quality – and on the tensions, dynamics and constant adjustment processes resulting from these contradictory effects at the company level. For instance, some innovations may

16

improve intrinsic aspects of job quality, but come along with work intensification (see for example, chapters on Automotive and Banking). Value chain restructuring can turn organisational innovations which prima facie sought to increase employee involvement into strategies predominantly geared towards cost-cutting; and this in turn can lead to dissatisfaction among both managers and employees and trigger new organisational changes (see for example, Aerospace chapter). Tight public budgets can result in unsatisfactory wage levels and amplify recruitment problems, which in turn can motivate companies to seek organisational innovations that improve other aspects of job quality, yet still constrain companies’ investments in training (see chapters on Care and Hospitals). An ageing workforce can lead companies to implement job rotation as a means to reduce physical strain, but in a context of increasingly Taylorised workplaces and strong pressures to remove ‘down’ times, job rotation also reduces forced breaks and makes employees rotate between highly repetitive tasks (see chapter on retail logitics). Instead of framing company responses as a coherent set of strategic choices, the analyses rather point to simultaneously diverse and partial responses to the challenges faced by companies and trace the resulting winding paths of company development. They nevertheless display the impact of structural factors on these dynamic adjustment processes and show how, next to the economic environment, institutional and cultural factors (e.g. management styles; power resources and attitudes of trade unions, national training systems or corporate governance) can – and do - make a difference.

The following sections provide summaries of the industry analyses, in particular highlighting their findings regarding

− the economic context in which the innovations operate and how the economic context impacts on these innovations

− the interactions of recent/current innovations with employment levels, skill requirements, job quality and inclusiveness, with a particular emphasis on the incidence of high performance workplaces; and

− the factors that make a difference in how companies innovate and deal with the challenges (national institutional setting, position in value chain, corporate governance; management styles)

3.1

Aerospace industry

The chapter on the aerospace industry by Gautie and co-authors covers both original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) and supplier firms in France, Sweden and the UK. With the dominant position of transnational corporations like Boeing and Airbus the aerospace industry still preserves key elements of the ‘producer driven’ value chain. The state however plays a more important role here than in other manufacturing industries: Private companies in all three countries under study are benefitting from public purchases of military and security devices; moreover, public funding is a very important source for research and development (R&D). In the 2000s, several trends gained speed and scope and thoroughly modified the aerospace value chain: Most importantly, a modularisation of production, accompanied by outsourcing and thus a shift to networked production in long-tailed value chains; and a stronger vertical differentiation within the group of suppliers, and accordingly an increased variety of relationships between them – ranging from fully integrated partnerships with some suppliers, to simple market relationships with others. Finally, financialisation in the aerospace industry has oriented firms more strongly toward the goal of maximising shareholder value. In the past decade, the trend towards globalisation has accelerated, partly induced also by the 2008 crisis that has further curtailed the purchasing capacity of the public customer (lower military and space budgets) and pushed firms to look for new clients, often at the international level. Moreover new international competitors have emerged and gained market shares,