Bottom-up Projects and the Study of

Their Prerequisite Starting Points

A Multiple Case Study on Temporary Use Projects in

Malmö

Sophia Friedel

Teerapong Sanglarpcharoenkit

Main field of study – Leadership and Organization

Degree of Master of Arts (60 credits) with a Major in Leadership and Organization

Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organization for Sustainability (OL646E), 15 credits

Spring 2020

Abstract

This paper uses an exploratory multiple case study research approach to investigate three bottom-up temporary use projects in Malmö. The aim is to provide an understanding of starting processes of temporary use through a project lens with a focus on phases and activities; key stakeholders and

motivations; and project key enablers. Regarding temporary use project phases and activities, this

study found that there are five steps/phases among the three cases: (1) inspiration; (2) ideation and

feasibility; (3) preparation; (4) implementation; and (5) on-going operation. Furthermore, the

common key stakeholders found in the projects are founders; landowner; intermediary;

authority; temporary user (participant, volunteer, or tenant); researcher; local community;

and funding body. Although the stakeholder groups were pretty similar, they engaged in different intensities in different projects. Their different motivations can be grouped in three different groups:

personal interest; assigned task; or monetary incentive. Some stakeholders had mixed

motivation. Moreover, this paper discovers 14 key project enablers: (1) municipality support; (2)

landowner support; (3) intermediary support; (4) financial support; (5) communication & expectation management; (6) network; (7) good planning; (8) community support; (9) openness and engagement; (10) partnership; (11) space and location advantage; (12) project team and entrepreneurial mindset; (13) luck; and (14) influence from the neighbor city. The study recommends creating a municipal temporary use activating unit in order to grow this

type of bottom-up movement in the city. This recommendation is in line with the discourse of the researchers in integrating bottom-up temporary use into the strategy and planning level of top-down activities. This research might allow future project leaders to get reference points and guidance for their own bottom-up temporary use projects, as well as provides understanding to researchers who are interested in temporary use and other bottom-up urban development fields.

Keywords: temporary use; project phase; project stakeholders; project enabler; bottom-up urban

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank all the people who supported us in creating this thesis. Your input, patience and positivity greatly contributed to this study.

We would like to thank our supervisor Elnaz Sarkheyli for her support and guidance throughout the whole development process of the paper. Your feedback often was challenging, but it was eye-opening and helped us to view our topic from different perspectives.

Thank you, to our interviewees whose information and expertise were the crucial factors for our research. We are grateful for the time and patience you had explaining us the long and complex processes of your projects.

Lastly, we are particularly thankful for the support and continuous encouragement of our families and friends during this challenging time. Keeva, Lina, Anna, Welmoed and Divya, thank you, you were the ones who kept us going, even when the end seemed unreachable.

Copies of relevant research materials as well as correspondence concerning the research study are available upon request.

The authors,

Table of Content

Introduction, Aim, and Problem 1

Background 1

Research Problem 2

Aim 3

Research questions 4

Research layout 4

Methodology and methods 5

Methodology 5

Methods 7

Data collection and selection of data sources 7

Data analysis method 12

Theory 14

Theoretical background 14

Temporary use (of vacant space) 14

Bottom-up approach in sustainable urban development 16

Project and project management theories 17

Development of the preliminary conceptual model 18

Different concepts related to temporary use 18

Development of the preliminary conceptual model based on literature 19

Preliminary conceptual model of how temporary use projects start 26

Temporary use projects in Malmö 29

Context of temporary use projects in Malmö 29

The transition of Malmö and its opportunities for temporary use 29

Innovative urban development in Malmö 30

National and municipal requirements regarding temporary use projects 30

Objects of multiple case study 31

Project 1: Vintergatan Urban Garden 31

Project 2: Caroli Park 32

Project 3: Lokstallarna 34

Findings and analysis 37

Vintergatan Urban Garden Project 37

Phases and activities 37

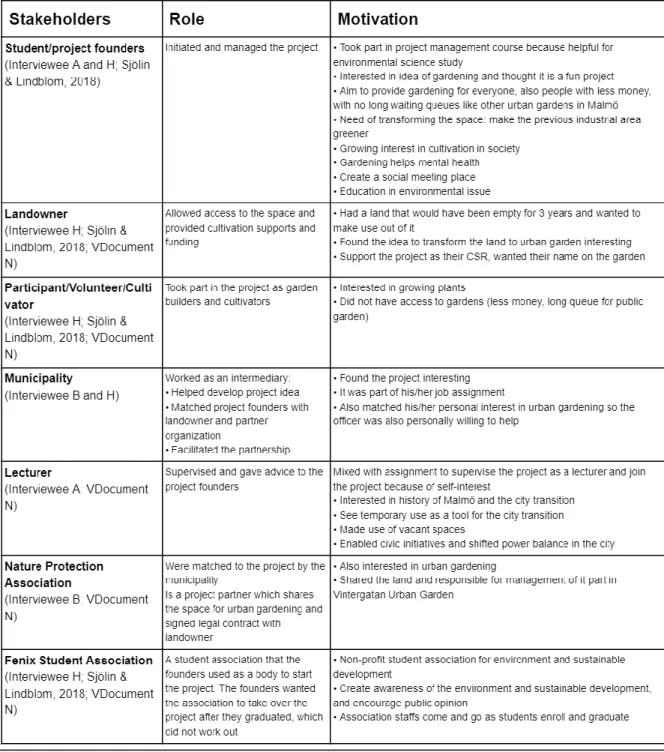

Project stakeholders’ roles and motivations 39

Caroli Park 42

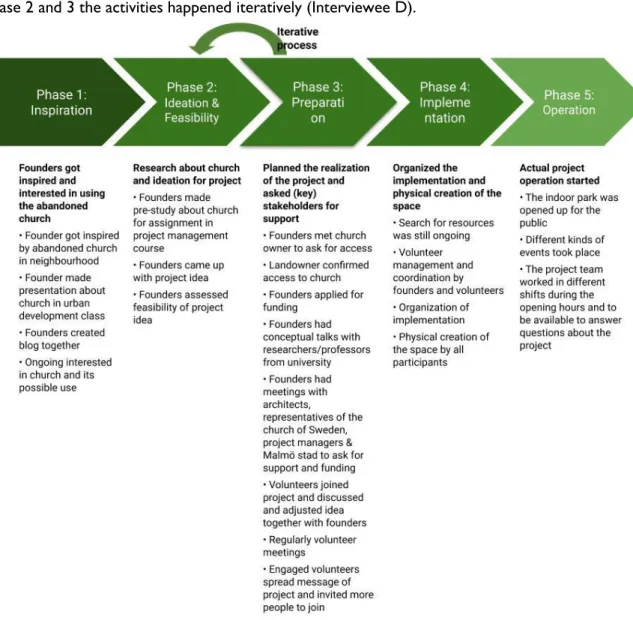

Phases and activities 42

Project stakeholders’ roles and motivations 45

Project key enablers 46

Lokstallarna 49

Phases and activities 49

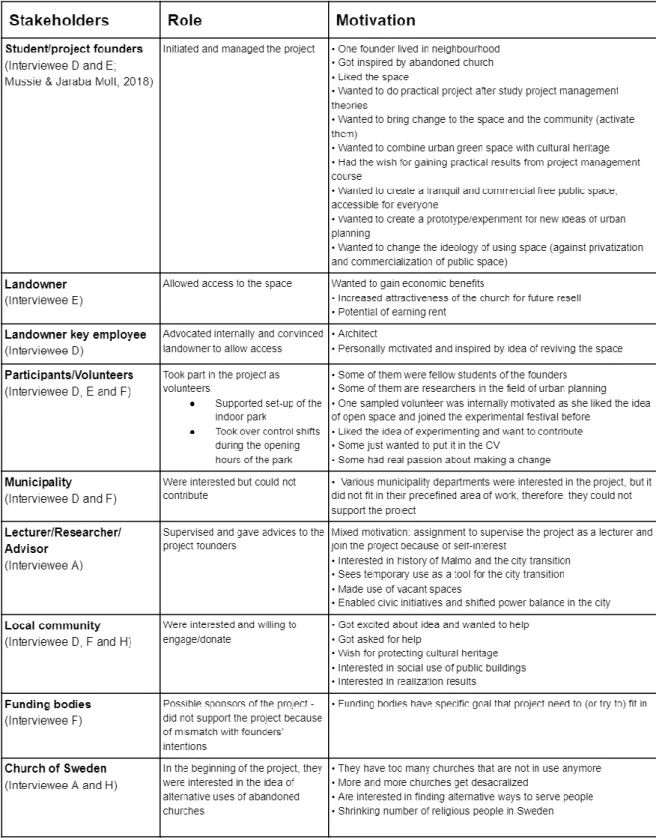

Project stakeholders’ roles and motivations 53

Project key enablers 55

Comparison of the cases and discussion 60

Phases and activities 61

Stakeholder engagement, roles and motivations 64

Project key enablers 67

Summary of the general findings of the examined cases 71

Conclusion 72

References 74

Appendices i

Appendix A: Benefit of temporary use i

Appendix B: Interview questions iv

Appendix C: Mindmaps for codings and themes v

Appendix D: Comparing phases and activities of the three projects xi

Table of tables

Table 1: Interviews used in this study ... 9

Table 2: Documents used in this study ... 10

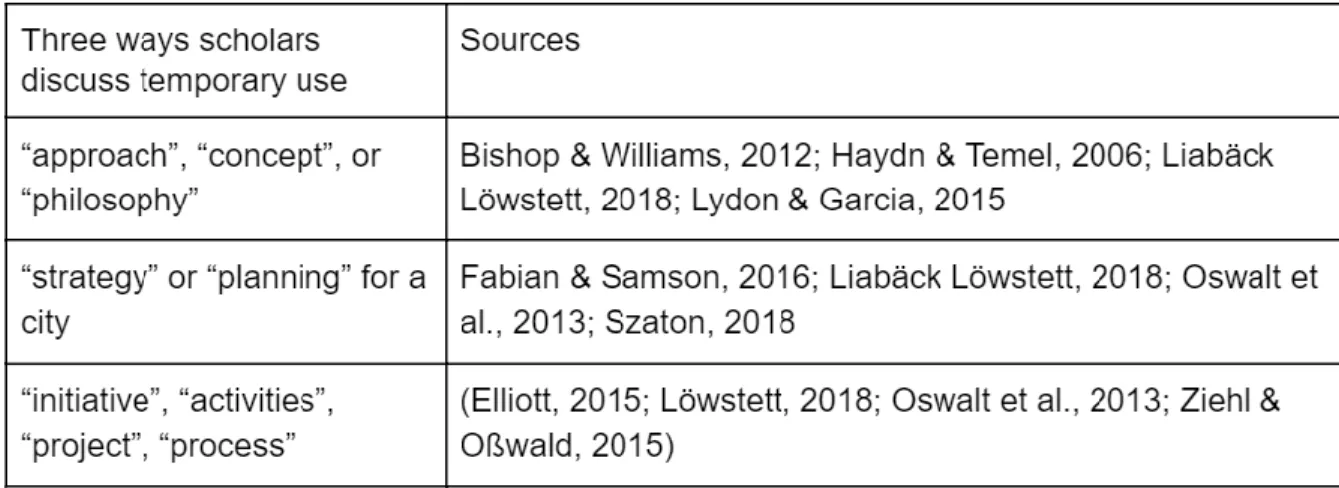

Table 3: Three ways scholars discuss temporary use in literature ... 15

Table 4: Different concepts related to temporary use ... 19

Table 5: Summary of literature used in the preliminary conceptual model ... 21

Table 6: Preliminary conceptual model of how temporary use projects started ... 26

Table 7: Temporary use projects examined in this study ... 36

Table 8: Vintergatan Urban Garden project’s key stakeholders, roles and motivation ... 39

Table 9: Caroli Park project’s key stakeholders, roles and motivation ... 45

Table 10: Lokstallarna project’s key stakeholders, roles and motivation ... 53

Table 11: Comparison of the stakeholder participation of the projects and the model ... 64

Table 12: Benefits of temporary use according to different literature ... ii

Table 13: Comparing phases and activities of the three projects ... xi

Table of figures

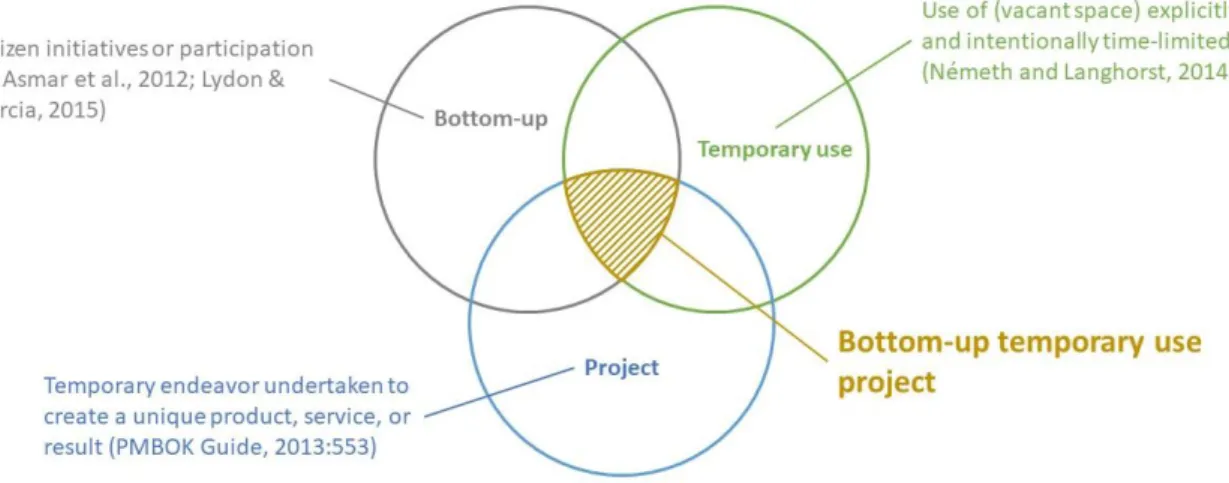

Figure 1: Three theoretical views of bottom-up temporary use projects ... 18

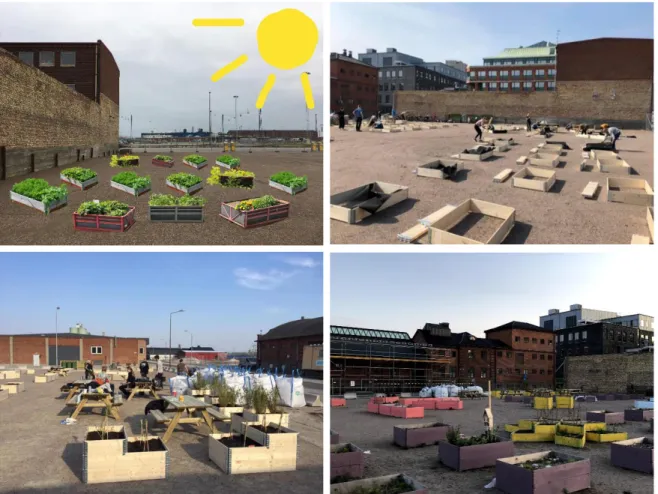

Figure 2: Vintergatan urban garden ... 31

Figure 3: Caroli Church ... 32

Figure 4: Caroli Park space and activities inside Caroli Church ... 33

Figure 5: Lokstallarna temporary use site ... 34

Figure 6: Lokstallarna and surrounding areas ... 35

Figure 7: Vintergatan Urban Garden Project phases and activities ... 37

Figure 8: Caroli Park Project phases and activities ... 42

Figure 9: Lokstallarna Project phases and activities ... 49

Figure 10: Community Organising Model used in Lokstallarna ... 53

Figure 11: Common phases of the three projects ... 61

Figure 12: Key enablers in the preliminary model and the studied projects in different intensity ... 68

Figure 13: Vintergatan Urban Garden project phases, activities, and stakeholders map ... v

Figure 14: Vintergatan Urban Garden project key enablers map ... vi

Figure 15: Caroli Park’s project phases, activities, and stakeholders map ... vii

Figure 16: Caroli Park project key enablers map ... viii

Figure 17: Lokstallarna project phases, activities, and key stakeholders map ... ix

1

Introduction, Aim, and Problem

Background

When scholars discuss the most influential developments of the globalized world, “urbanization” is often named. Elmqvist and colleagues (2013) defined the term “urbanization” as a “multidimensional process that manifests itself through rapidly changing human population and changing land cover” (p. 4). Urbanization is not a new trend, it has happened at all times, but the dimensions have gotten bigger and bigger during the last 100 years (Elmqvist et al., 2013). In the middle of the last century, the ratio of the world’s population, living in urban areas was 30% (United Nations, 2018). Two years ago, in 2018, another 25% of the world’s population were living in urban areas, and in 30 years, there are around 70% of the world’s population estimated to live in such areas (United Nations, 2018).

The faster urban areas are growing, the more obvious the downsides of this process are revealed. Pollution-related health conditions, changes in insolation norms, communicable diseases, poor sanitation and housing conditions, road traffic and high population density are just a few issues mentioned in conjunction with urbanization (Kuddus et al., 2020; Musinova, 2019). Urbanization does not necessarily mean that the population of an urban area is rising, it can also imply that its land cover is rising. This means that even if a city’s population is stagnating or shrinking, the land cover of the city can rise when its inhabitants demand more and more space per capita (Elmqvist et al., 2013). The physical growth of the world’s urban areas is on average twice as fast as the growth of its population (Elmqvist et al., 2013). Therefore, the lack of space is also a problem in urban areas and will become an even bigger one in the future (Elmqvist et al., 2013). This shows that growing urban areas demand efficient use of space, temporary use in abandoned, or vacant land or buildings could be one of the solutions for. They offer an “opportunity for regeneration and renewal” (Madanipour, 2018) of urban areas and more efficient use of space, as well as other benefits that contribute to sustainable urban development (Frisk et al., 2014; Madanipour, 2018; Németh & Langhorst, 2014; Refill, 2018a).

“Temporary use” can be defined as “explicitly and intentionally time-limited in nature” (Németh & Langhorst, 2014), p. 144). Examples for temporary use projects are urban gardens, pop-up stores, small business ventures, festivals, music clubs, concerts, theaters, art studios, exhibitions, parks, food markets, restaurants (Moore-Cherry & Mccarthy, 2016; Németh & Langhorst, 2014; Ziehl & Oßwald, 2015). Temporary use projects can be started by top-down or bottom-up initiatives. Top-down initiatives are often led by mayors, municipal departments or city councilors (Lydon & Garcia, 2015). Projects led by community groups, neighborhood organizations or citizen activists are bottom-up initiated (Lydon & Garcia, 2015).

Temporary use is highly linked to sustainable urban development (Frisk et al., 2014; Madanipour, 2018; Németh & Langhorst, 2014). The term “Sustainable urban development” was defined by Camagni (1998) as “a process of synergetic integration and co-evolution among the great subsystems making up a city (economic, social, physical and environmental), which guarantees the local population a non-decreasing level of wellbeing in the long term, without compromising the possibilities of development of surrounding areas and contributing by this towards reducing the harmful effects of development on the biosphere” (p. 6). Temporary use projects could be identified as a tool for sustainable urban development, as they have economic, social, and environmental benefits for their stakeholders.

2 From an economic perspective, temporary use can be highly cost-efficient compared to new projects, as they require very little investment for development. Their spaces and facilities already exist (Németh & Langhorst, 2014). The rents of the spaces are often low and therefore make it more affordable, especially for small tenants and small businesses (Refill, 2018b). Thanks to these characteristics, temporary use projects not only save costs but could also generate money quickly. These factors enable people to start businesses, who would not be able to do this under normal circumstances (Németh & Langhorst, 2014). Not only the founders of temporary use projects experience benefits, but also landowners and authorities benefit through commercial advantages and the creation of a sense of space (Löwstett, 2018). Furthermore, temporary use can be valuable for landowners as “soft maintenance” for their abandoned spaces (Refill, 2018b).

Temporary use also creates social benefits. The increasing activities on formerly vacant land create a vibrant atmosphere and attract more and more people to join these new public spaces (Németh & Langhorst, 2014). The positive atmosphere and rising attention are not only useful for the temporary project itself, but also for the whole neighborhood (Refill, 2018b; Németh & Langhorst, 2014). There is a chance for new communities to be built around temporary use projects, which can have a positive impact on the local people (Németh & Langhorst, 2014; Bishop & Williams, 2012). Also, people of marginalized groups are enabled to actively engage in these activities, which contributes to greater social equality. Thus temporary use is also contributing to an extension of democracy. It offers opportunities for marginalized groups to be heard and get or take responsibility for spaces (Frisk et al., 2014).

Temporary use projects also have positive impacts on the environment of an urban area. For example, the usage of vacant urban brownfields for urban gardening or as stormwater runoffs can improve living conditions for insects and other animals living in cities, as well as contribute to a better microclimate in cities (Bishop & Williams, 2012; Németh & Langhorst, 2014). Further benefits of temporary use can be found in Appendix A.

Convinced by the benefits of temporary use projects, citizen groups, landowners, and urban planners might ask themselves how to start such projects. However, the process of starting one is still a mystery. This paper tries to find answers to this question.

Research Problem

Most of the current literature about temporary use projects focus on the following aspects: the description of former and actual temporary use projects, the comparison of different kinds of usage of vacant spaces and the listing of benefits of temporary use projects (e.g., Bishop & Williams (2012); Madanipour (2018); Németh and Langhorst (2014); and Ziehl and Oßwald (2015)). Furthermore, the discourse is mainly about how to integrate or strategically include temporary use in planning or on policy level (e.g., De Smet (2013); Fabian and Samson (2016); Löwstett (2018); Oswalt and colleagues (2013); and Szaton (2018)). Only a little attention has been paid to the starting processes of bottom-up temporary use projects by research, even though these processes seem to be harder to comprehend for interested project outsiders, as they are often less formalized than top-down projects. Furthermore, most of the researchers who addressed temporary use projects come from fields such as urban planning, architecture or geography (e.g., Frisk and colleagues (2014); Löwstett (2018); Németh and Langhorst (2014); and Ziehl and Oßwald (2015)). Therefore, temporary use is mainly

3 viewed from these perspectives, but not from a project perspective including phases and activities; key stakeholders and motivations; and project key enablers.

Stakeholders are mostly mentioned in regard to benefits they gain because of the projects, but not when it comes to their motivation and active participation in the different starting phases of the projects. Regarding published literature, the starting phases and activities of bottom-up temporary use projects are not examined sufficiently, therefore, the projects’ key enablers can hardly be identified. There is too little information about the starting process of such projects, to understand which stakeholders or factors were indispensable for the successful start.

The lack of information about the starting processes of temporary use projects, its phases, activities, stakeholder involvement, and key enablers constitutes a gap in academic literature. The missing information might also hinder future project leaders from learning from former projects and research. This could make their new projects struggle or lead to mismanagement of resources and expectations of stakeholders. In the worst case, those factors could lead to project failures. In contrast, getting the knowledge could provide insights in and guidance for the starting process of new temporary use projects, and the management of resources and stakeholders. Therefore, this multiple case study will investigate and explore how temporary use projects in Malmö were started.

Malmö was chosen as the research area, as it is the fastest growing city in Sweden (Malmö Stad, 2019a, 2019b). At the same time it still has many vacant spaces, which offer opportunities for temporary use . Furthermore, it is interesting, as in Sweden there is a unique legal right called “Allemansrätten” about the equal right of everyone to access public assets (Förening.se, 2020). The law could impact the planning and realization of such projects. Moreover, the municipality has shown interest in innovative urban development concepts, including temporary use, by establishing the Malmö Innovation Arena (Bigdelou, 2020). The conditions above will be described in the context part. There have been some bottom-up temporary use projects in Malmö already, but it seems there might be even more potential for such projects. Due to these characteristics and the research availability, Malmö is an interesting example area for a study about temporary use projects.

Aim

This paper aims to explore and investigate starting processes of temporary use projects through examining three temporary use cases in Malmö. The aspects studied are the starting phases and activities, stakeholders’ involvement, and the key enablers of the projects. These aspects will be viewed from a project perspective. By analyzing findings from three different cases and comparing them, this paper aims to provide insights and an understanding for future temporary use project founders as well as for theories on temporary use, bottom-up initiatives, direct democratic processes, and sustainable urban development.

4

Research questions

RQ 1: How were bottom-up temporary use projects in the city of Malmö started?

To specify the research question the following sub questions have been formulated:

RQ 1.1: What were the steps taken when starting bottom-up temporary use projects in Malmö?

RQ 1.2: Who were key stakeholders of the bottom-up temporary use projects in Malmö and what were their contributions and motivations?

RQ 1.3: What were the enabling factors for starting bottom-up temporary use projects in Malmö?

Research layout

The research is divided into 6 major parts. Chapter 1 illustrates the purpose of the research and provides background information. Chapter 2 describes the underlying methodological approach and the chosen methods of the study. Chapter 3 gives an overview of contemporary theories and practices regarding the bottom-up temporary use projects and defines a preliminary model. In Chapter 4, the context of temporary use projects in Malmö and the examined temporary use cases are described. The purpose of Chapter 5 is to give detailed insights in the findings of the three examined. Therefore, the cases get analyzed, structured and compared to each other as well as put in relation to the prediction of the preliminary model. The results are then discussed in regard to the underlying theories and the preliminary model. Finally, chapter 6 provides a summary of the whole paper.

5

Methodology and methods

The research questions lead to a qualitative research method. This study consists of two major parts: (1) creating a preliminary, conceptual model of the starting process of temporary use projects and (2) exploring cases of bottom-up temporary use projects in Malmö, using the preliminary model as a framework. This chapter will explain the research design, the selection of the cases, data gathering and analysis methods, reasons behind the chosen data sources, limitations, and reliability and validity.

Methodology

Case study researches are used to study social processes or phenomena (Baxter & Jack, 2008; Silverman, 2015). They provide opportunities to “explore or describe a phenomenon in context using a variety of data sources” (Baxter & Jack, 2008, p. 544). According to Yin (2013), a case study should be considered when (1) the study aims to answer “how” and “why” questions; (2) the researcher can not influence the behavior of people involved in the case; (3) the contextual conditions should be covered as they may be relevant to the phenomenon; or (4) the boundaries are not clear between the phenomenon and context. As a case study research, this study is based on a constructivist paradigm (Baxter & Jack, 2008; Yin, 2013). Constructivists claim that “truth is relative and that it is dependent on one’s perspective” (Baxter & Jack, 2008, p. 545).

An exploratory case study is an approach used to investigate phenomena that have no clear, single set of outcomes (Yin, 2013). Moreover, investigating multiple cases enables researchers to explore similarities and differences between them in order to replicate findings across cases and provide opportunities for broader understanding beyond specific cases (Baxter & Jack, 2008; Silverman, 2015, Chapter 3; Yin, 2013). According to the research aim, this study used these two approaches combined as an exploratory multiple case study approach.

For the case study approach, Baxter and Jack (2008) suggested some steps including (1) Determine

the type of case study according to the overall study purpose. (2) Determine propositions to guide the study (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Stake, 1995 cited in Baxter & Jack, 2008). The propositions

can be viewed as an educated guess to the possible outcomes of the research. (3) Develop a

conceptual framework to serve as an anchor for the study, especially in the stage of data

interpretation (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Stake, 1995; Yin, 2003 cited in Baxter & Jack, 2008). The framework should continue to develop and include all themes that emerged from data analysis. (4)

Study cases from different data sources to get holistic views of the cases and enhance data

credibility (Patton, 1990; Yin, 2003 cited in (Baxter & Jack, 2008). Moreover, Silverman (2015) suggested using theoretical sampling to select cases (p. 122). Theoretical sampling refers to “selecting cases in corresponding to research questions, theoretical position, and explanation that are developing in a case study” (Silverman, 2015, p. 105). This approach, based on deviant-case analysis and comparative methods, provides opportunities for a broader understanding and generalization of case study research (Silverman, 2015). Case studies’ reports could be complicated, repetitive, and not easy to understand due to the complex nature of this approach (Baxter & Jack, 2008). This paper will report each studied case in chronological method and all cases together in comparative method according to Yin's (2013) suggestion.

6

Preliminary conceptual model of how temporary use projects started

In order to examine the process of bottom-up initiated temporary use projects and understand their enabling factors, various literature and documents related to temporary use projects were studied, analyzed, and put together to create a framework. It was built to understand overall temporary use projects’ processes, stakeholders, and key enablers. Based on the literature, this study used the

systemic review combined with the integrative review approach to create a preliminary

conceptual model (Vossler, 2014). The elements in the model served as the propositions to guide the study and data collections as well as the whole model served as the conceptual

framework to guide data collections and interpretations, as suggested by (Baxter & Jack, 2008; Miles

& Huberman, 1994; Stake, 1995; Yin, 2003, 2013).

Selection and study of temporary use cases

Based on the theoretical sampling approach and availability, three temporary use projects were selected based on different scales, bottom-up processes, and supporting resources — (1)

Vintergatan Urban Garden, (2) Caroli Park, and (3) Lokstallarna. The different supporting

resources include funding, level of municipality support, and level of intermediary involvement.

Vintergatan Urban Garden is a small-scale bottom-up temporary use that received great support

from the municipality and the landowner. The municipality also acted as an intermediary in this project.

Caroli Park is also a small-scale bottom-up initiative and experiment project. The project could not

get any significant support from any municipality departments and funding bodies. It appeared to have no intermediary involved. Despite the lack of these supports, the project was able to operate on a volunteer basis.

Lokstallarna is a unique large-scale top-down temporary use project that utilizes a bottom-up

approach. The project was initiated by the municipality with great support from various municipality departments, the landowner, and a temporary use expert as an intermediary. This project is also a part of a large-scale EU project funded by 4 funders.

Scope of the project phases studied

Due to their temporary nature, any project will have an ending phase (AXELOS, 2009; Cobb, 2012; Rose, 2013). The researchers are aware of this phase; however, the ending stages of temporary use projects are not covered in this study as they are out of the scope of “starting process”. In addition, there was no data available for ending phases as two of the selected cases are still operating.

7

Methods

Methods to develop the preliminary conceptual model

Unlike a theoretical literature review that is usually used to give background and identify research gaps for a study, the systematic review allows researchers to find an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated empirical question (Onwuegbuzie, 2016; Vossler, 2014). Moreover, an integrative literature review could be used to generate new frameworks and perspectives on a topic by reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on the topic (Vossler, 2014). In order to create the preliminary model various literature and documents related to temporary use projects were reviewed. The relevant literature was identified on Google scholar, Google search, and Malmö University’s Libsearch platform with relevant keywords, such as “temporary use project”, “project management”, and “bottom-up urban development”. Both peer-reviewed research and grey literature such as reports, professional articles, handbooks, books, and theses, were used in order to get a broader sense of the project in practice. The authors used a systematic literature review approach with the empirical question: “How were bottom-up initiated temporary use projects

started?”, to create a new preliminary framework for temporary use projects from the literature. In

total, 53 pieces of literature were read in this process and 12 pieces were mainly used as described in the preliminary conceptual framework section.

Data collection and selection of data sources

Data collection method

To get a holistic view of the cases and enhance data credibility, studying cases from different data sources is recommended (Baxter & Jack, 2008; Yin, 2013). This study combined two methods to collect data (1) semi-structured interviews and (2) document analysis.

The semi-structured interviews were conducted with key members of the projects’ starting processes, in order to understand their experiences in these processes. The interviews include the project founders, intermediaries, volunteers, and municipality staff. This method allows the researchers to explore the processes as well as investigate deeper details with follow up questions. The interview questions were based on the preliminary model, preliminary document study, and information from prior interviews. They were formed attentively to get the relevant responses that answer the research questions as well as to understand the projects’ context. The interviews were used as the main data source.

The document analysis covered project reports, presentations, internal email records, minutes of meetings, project pages and websites, as well as other project documents that were available to this study. The documents were used as secondary data to support the interviews.

Selection of interviewees and documents

In order to understand the starting process of the temporary use projects, the project members involved in the project management were selected. There were some founders and intermediaries, as well as a volunteer and a consultant. The interviews aimed to explore the phenomena from multiple perspectives regarding Baxter and Jack's (2008) suggestions. The municipality staff, working with the regulations of Malmö, was interviewed in order to understand the municipality's roles and influences on the temporary use projects. All interviews used in this study are listed in table 1.

8 Due to the key persons’ availability and the time limit, the researchers could not interview all project founders and key persons. Regarding the COVID19 pandemic situation, only one interview was done in person while the rest were conducted online. There were also limitations in interviewing in English language. The interviewers prepared a long time to cope with this issue and intently used follow up questions to confirm their understanding when discussing complex processes with various factors. They also kept in mind the ethical aspects and avoided leading-the-witness questions. All interviews were intently done by both researchers to capture potential missing points and confirm their understanding with each other. All the interviews were recorded with the consent of the interviewees. Regarding document study, this research had limited access to all three projects’ documents. This paper used two types of documents: (1) documents about the processes, mainly used in Lokstallarna, and (2) internal documents used in the project process, mainly used in Vintergatan. Documents that are available to the public online were reviewed. Relevant documents were selected, including pages, websites, and project reports. There was also access to many internal documents thanks to project leaders, especially in the Vintergatan project. Many relevant documents were selected including presentations, emails, and minutes of meetings.

Due to limitations in Swedish language, some project documents were initially translated from Swedish to English with the Google translation software. All incompatible points with the interviews and other documents were verified in order to minimize the translation issues. Only points verified with other sources were used to ensure correctness. They were only used as a secondary source to support the interviews. All the points used in this study were also sent back to the interviewees to confirm the correctness as well as their consent to use the data. All the documents used are listed in table 2. In Vintergatan, one municipality staff who played an important part in intermediation, one of the three founders and one professor who was a consultant and participant were interviewed. The founder also allowed this study to access most of their unpublished internal documents. Despite only interviewing one founder, data from all interviewees was coherent and supported by many important internal documents such as email records, minutes of meetings, and an executive summary of the land use contract.

This study was able to interview all two project founders of Caroli Park along with one key volunteer and one project consultant. According to the founders, the project was quite informal and therefore only had few documents available.

The Lokstallarna project was owned by both the landowner and the municipality. The intermediary played an important role in facilitating all stakeholders and their bottom-up process. The municipality project leader and the intermediary leader were interviewed; however, there was no interview conducted with the landowner due to their availability. The researchers were granted access to both internal and published documents about the project’s unique process of top-down development utilizing the bottom-up approach.

9 Table 1: Interviews used in this study

10 Table 2: Documents used in this study

12

Data analysis method

This study used thematic analysis to analyze the collected data. In order to analyze data, this paper follows 5 steps suggested by (Liu, 2020)): (1) organize the data, (2) identify ideas and concepts — coding, (3) build overarching themes (4), generate findings, (5) confirm findings.

All interviews were transcribed using the AI transcription software Otter.ai. The transcriptions were organized in tables and coded manually. In line with Silverman (2015), codes were created for key phrases or topics mentioned by the interviewees. The researchers manually confirmed and corrected the transcription with the help of the records while coding. Initially, double codings on the same transcription were done independently by both researchers. Their results were cross-checked to make the coding more consistent.

The codes should be allocated to an umbrella topic or theme to structure the analysis (Silverman, 2015). This study uses the topics from the preliminary model as umbrella topics. The themes included

13 activities, stakeholders´ roles and motivations, and key enablers. The emerging themes were discussed, mapped, and organized in tables and mind maps for each project by consensus of both researchers. The key elements from the document studies were also mapped into the existing themes to confirm the findings as well as support the themes in deeper detail. The final findings were also sent back to the interviewees to discuss, clarify the interpretation, and confirm their correctness as suggested by (Baxter & Jack, 2008; Liu, 2020).

This study uses a combination of deductive and inductive approaches. The researchers are aware that using a conceptual framework may “limit the inductive approach when exploring” a social process or phenomenon (Baxter & Jack, 2008, p. 553). To prevent being too deductive, Baxter and Jack (2008) suggested that the researchers should be aware if their thinking has become too driven by the framework. They encourage to think outside the model and discuss this with other researchers. Although based on the preliminary model, this study did not only stick with the model, but also explored other important aspects as they suggested. This can be seen in the results and the discussion part.

14

Theory

A bottom-up temporary use project can be viewed as a sustainable urban development project. A project is considered a temporary organization and is a part of leadership and organizational studies (AXELOS, 2009; Witmer, 2019). In this chapter, theories related to project and project management, temporary use, and bottom-up approach in sustainable urban development will be discussed. Then the development of the preliminary conceptual model of how temporary use projects could start will be explained. This research used the model as a framework to guide the study as stated in the methodology and method section.

Theoretical background

Temporary use (of vacant space)

In order to tackle some of the problems of urbanization, temporary use concepts emerge in more and more cities around the globe as a possible solution (Németh & Langhorst, 2014). The trend of temporary use of space has gained increased attention by scholars, practitioners and politicians in the last few years (Madanipour, 2018). According to Bishop and Williams (2012), “temporary use” cannot be “based on the nature of the use, or whether rent is paid, or whether a use is formal or informal, or even on the scale, longevity or endurance of temporary use, but rather the intention of the user, developer or planners that the use should be temporary” (p. 5). Németh and Langhorst (2014) summarize this definition of “temporary use” shortly: “[T]hat which is explicitly and intentionally time-limited in nature” (p. 144).

There are different terms for “temporary use” which mean the same, such as “temporary

urbanism” (Kossak, 2012; Madanipour, 2018; Tardiveau & Mallo, 2014; The U.S. Department of

Housing and Urban Development, 2014), “temporary urban use” (Moore-Cherry & Mccarthy,

2016), “interwhile use” (Reynolds, 2011) or “meanwhile use” (Butler, 2017; Hill et al., 2013;

Meanwhile Foundation, 2020). However, this paper will refer to this concept as "temporary use" as it seems to be the most common one.

The term “use of space” in the context of temporary use means the use of vacant land. The term “vacant land” again can be interpreted broadly as “all land that is unused or abandoned for the longer term” (Németh & Langhorst, 2014). This includes for example brownfields but also complexes of buildings that have been abandoned and have not been used within the last couple of months (Pagano & Bowman, 2000, cited in Németh & Langhorst, 2014). The appearance of vacant land is not dedicated to certain areas of cities. It can be more or less at every place of a city, but there is a tendency that it occurs often at transitioning zones, like in former industrial areas close to highways (Németh & Langhorst, 2014). Reasons for the appearance of vacant land can be little interest of the economy and politics in investing in the reconstruction of already existing buildings, but also the shift from an industrial towards a service oriented society (Németh & Langhorst, 2014). There are also different words for the term “vacant land”, like “second hand spaces” or “interim spaces” (Ziehl & Oßwald, 2015).

The usage of vacant spaces can be diverse. There are urban gardens, “pop”-up stores, small business ventures, festivals, music clubs, concerts, theaters, art studios, exhibitions, parks, food markets, restaurants, etc. (Moore-Cherry & Mccarthy, 2016; Németh & Langhorst, 2014; Ziehl & Oßwald, 2015). Although they are usually utilized by citizens in the bottom-up approach, temporary uses can be

15 bottom-up, top-down, or the combination of these two approaches (Bishop & Williams, 2012; Frisk et al., 2014; GivRum, 2016; Oswalt et al., 2011, 2013; Stevns, 2020).

Different aspects to consider temporary use

Temporary use could be considered in different aspects: Scholars and practitioners have discussed temporary use on many different levels such as an “approach”, “concept”, or “philosophy”; “strategy” or “planning” for a city; an “initiative”, “activity”, “project”, or “process” (see Table 1 for example literature). According to Bishop and Williams, (2012), in general, temporary uses of space are “practices through a limited amount of time”. They are usually utilized by citizens to experiment and create their city. Regarding project management theories, a project is a “temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result” (Rose, 2013, p. 553). According to the definitions, a temporary use initiative can be considered as a project. Therefore, this study will consider it in that aspect and will emphasize its processes.

16

Bottom-up approach in sustainable urban development

Bottom-up or grassroot can refer to local residents, citizen activists, community groups, or neighborhood organizations while top-down usually relates to governments and policies at different levels such as municipal departments, city councilors, or mayors (Eckerberg et al., 2015; El Asmar et al., 2012; Lydon & Garcia, 2015). A bottom-up approach is a citizen-led process. It can be both a citizen initiative or citizen involvement in a participatory process (El Asmar et al., 2012; Lydon & Garcia, 2015). Bottom-up initiatives allow citizens to take action to address their own problems, while the participatory approach allows citizens and communities to share their views and take part in planning strategies to improve and solve issues related to their communities (El Asmar et al., 2012; Lydon & Garcia, 2015). The bottom-up process allows effective use of available resources through mobilizing communities’ resources (Scubeler, 1996; O’Hara, 1999 cited in El Asmar et al., 2012). The benefits of this approach include creating sustainable communities as well as contributing to environmental, social, and economic sustainability (El Asmar et al., 2012).

In some situations bottom-up and top-down can conflict and create tension (Lydon & Garcia, 2015, p. 11). However, Eckerberg and colleagues (2015) found that bottom-up and top-down collaborations can complement each other “in situations with considerable conflict over time and where public policies have partly failed” (p. 289). Moreover, the bottom-up approach can even be combined with a top-down approach in urban development in order to balance their advantages and disadvantages (Bishop & Williams, 2012; Frisk et al., 2014; GivRum, 2016; Oswalt et al., 2011, 2013; Stevns, 2020). Bottom-up approaches play an important part in sustainable urban development. El Asmar and colleagues' (2012) study found that top-down command and control can not produce effective sustainable urban development. In order to tackle this issue, they suggested that a bottom-up approach in urban development and management is needed. Moreover, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) also emphasize the role of bottom-up approaches in goal 11 about sustainable cities and communities (United Nations, 2020b). The goal includes the target 11.3 to “enhance inclusive and sustainable urbanization and capacity for participatory, integrated and sustainable human settlement planning and management” with indicator 11.3.2 for regularly and democratically direct participation of civil society in urban planning and management (United Nations, 2020a). Regarding the goal and indicators, Al-Zu’bi and Radović (2019) suggest governments to explore the potential for bottom-up community engagement in policy formulation and adoption.

17

Project and project management theories

The term “project” is defined by many scholars and professional communities. PRINCE2 and PMBoK Guide are the most widespread project management frameworks (Albert et al., 2017). The PMBoK Guide defines a project as a “temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result” (Rose, 2013:553). PRINCE2 views a project as a temporary organization created for the purpose of delivering agreed results on each case (AXELOS, 2009). A project consists of “a unique set of processes consisting of coordinated and controlled activities, with start and end dates, performed to achieve project objectives” (ISO 21500, 2012). Cobb (2012) summarizes that projects are unique

and temporary. They are unique in terms of “the outcomes they produce as well as in terms of how

they are conducted” (p. 4). Projects are also temporary and have a life cycle that fundamentally affects their structure, dynamics, operations, and their results (p. 4).

Project life-cycle — a project is temporary and usually has a predetermined life cycle (Cobb, 2012;

Rose, 2013; G. Silvius, 2019b). Both scholars and professionals divide the project lifecycle into five phases (Carboni et al., 2018; Cobb, 2012; Rose, 2013; G. Silvius, 2019b). Although the names and some details are different, the project phases, in general, are quite similar. For example, initiation, planning, launch, execution, and closing (Cobb, 2012, pp. 4–5); initiation, planning, development, implementation (G. Silvius, 2019b); pre-project phase, discovery phase, design phase(s), delivery phase(s), and closure phase in the PRiSM Project lifecycle (Carboni et al., 2018); and initiation, planning, execution, performance/monitoring, and project closure in the PMBOK Guide (Rose, 2013). Despite different names, the activities and objectives in the different phases are quite similar. Based on Cobb (2012), activities in each phase of a generic project are as follows (pp. 4-5):

● Project initiation is the stage in which a project’s key stakeholders first come together to

define the broad outlines and research if the project is feasible. One key objective is to decide whether the project will move forward.

● Project planning focuses on setting goals and roadmaps to guide the project. More detailed

planning, including tasks, estimated resources, costs, and time, is done in this stage.

● Project launch is the beginning of actual work. This stage is started after the planning is done

and initial resources are committed. The forming and structuring of the project team are also done in this phase.

● Project execution — most of the project’s work is done in this stage. The tasks are

delegated to the project team members. It is needed to work with external stakeholders in this stage to maintain the project support.

● Project closing is when the final project outcomes are delivered. Some reports might be

produced in this stage. In this stage, the project ends and the project team disbands.

Project stakeholders — According to Cobb (2012), generic key project stakeholders are clients,

host organizations, project teams, end users, and suppliers. Key stakeholders are the ones “who have the power and authority to make important decisions about the conduct and outcomes of the project” (p. 19). Other scholars also emphasize that based on stakeholder theory, an organization needs to take the needs of wider groups of stakeholders into account, than just their shareholders (ISO 21500, 2012; G. Silvius, 2019b). The International Standard Organization extended the definition of project stakeholders to a “person, group or organization that has interests in, or can affect, be affected by, or perceive itself to be affected by, any aspect of the project” (ISO 21500, 2012). One success criteria of a project is to meet the needs of its stakeholders (Albert et al., 2017). Concerning the broader stakeholders definition, Silvius and Schipper (2019) suggested sustainable projects to consider (1)

18 stakeholders with economic interests, (2) stakeholders with social interests, and (3) stakeholders with environmental interests.

Project stakeholders — Cobb (2012) suggests to take a project‘s stakeholders interests and needs into account, bridge the gap between stakeholders, communicate effectively, negotiate agreement, and maintain support and commitment. Moreover, in the novel field

of sustainable project management, many scholars agree that a project‘s stakeholders play an important role (Eskerod & Huemann, 2013; Gilbert Silvius et al., 2017; A. J. G. Silvius & Schipper, 2014; G. Silvius, 2019a; G. Silvius & Schipper, 2019).

Project enablers — Elements for project success can be viewed as project key enablers. According

to Cobb (2012), the factors that contribute to a project‘s success, in general, are scope, cost, and time. Regarding these factors in generic projects, he suggests considering resources, planning, managing

risk, project team and leadership, and stakeholders´ support and commitment. However,

Albert and colleagues (2017) found that the project success elements and criteria in detail differ in various working areas and there is no pattern across various fields.

Figure 1: Three theoretical views of bottom-up temporary use projects (authors’ creation)

Development of the preliminary conceptual model

Since there is no research directly addressing the starting process of temporary use projects, this study reviews both peer-reviewed and grey literature about temporary use as well as other different concepts that are highly related to temporary use. The literature was reviewed using the systematic review approach to create a conceptual model of how temporary use projects start.

Different concepts related to temporary use

Temporary use is a concept that fosters urban fluidity. In addition to the mentioned terminologies, there are other various concepts that strongly connect and aim for urban fluidity such as Do It

Yourself (DIY) urbanism, Everyday urbanism, Open-source urbanism, Tactical urbanism and Placemaking (Bishop & Williams, 2012). Although these concepts often involve similar aspects

as temporary use, such as a temporary time frame or bottom-up initiatives, none of them is exactly the same nor has the exact same goals. The concepts will later be used to develop the preliminary model.

19 Table 4: Different concepts related to temporary use

Development of the preliminary conceptual model based on literature

In order to examine the processes of bottom-up initiated temporary use projects and understand their enabling factors, various literature and documents related to temporary use, as well as other mentioned related concepts, were studied. Both peer-reviewed research and grey literature such as reports, professional articles, handbooks, books, and master theses, were also included in order to get a broader view of the concept.

20 These documents were studied, analyzed, and put together in order to create a framework to understand overall temporary use projects’ processes, stakeholders, and key enablers. Overall contents were analyzed and organized into three project-related categories: phases and activities; stakeholders´ involvement in the process; and possible key enablers mentioned in a process.

21 Table 5: Summary of literature used in the preliminary conceptual model

26

Preliminary conceptual model of how temporary use projects start

Through a project process lens, the content of documents and literature were put together and structured into four phases of temporary use projects along with possible activities, stakeholders engaged, and key enablers. This aimed to create a conceptual model for a possible starting process of temporary use projects. The elements in the model serve as propositions to guide the study while the whole model serves as the conceptual framework for the data collections and interpretations of the case study research, as suggested by (Baxter & Jack, 2008; Yin, 2013).

Based on the literature and project phases concept, the starting process of temporary use projects

could be divided into four phases. The project closing phase is out of the study‘s scope.

Table 6: Preliminary conceptual model of how temporary use projects started based on 13 sources in table 5

27

Phase I: Feasibility — This phase relates to introducing ideas and engaging people.

In site construction projects, the first phase is to assess feasibility (Robichaud & Anantatmula, 2011). This might also apply to and explain starting a temporary use site. Projects for Public space (2016) suggested the first step for the place-led, community-based process is to identify place and

stakeholders. Silvius and Schipper (2019) also proposed identifying stakeholders at the beginning

of sustainable projects. In the initial phase of a temporary urbanism collaboration project, Elliott (2015) found that a project involves gathering initial support, especially from individuals; creating

mock-ups to showcase and get feedback; layout key supporters and possible roadblocks.

Lydon and Garcia (2015) suggested to understand for whom you are really planning or

designing in the first step of Tactical Urbanism. Since the main objective in this phase is to engage

stakeholders to get support and evaluate feasibility, communication could be a key activity in this stage. Communication is also emphasized in starting temporary use by (Refill, 2018b). Project stakeholders involved in this phase can be individuals (Elliott, 2015; Lydon & Garcia, 2015; Oswalt et al., 2013), communities and neighborhoods (Bishop & Williams, 2012; Löwstett, 2018; Projects for Public space, 2016). Regarding these activities, people and community participation,

feedback to improve the design, and individual and neighborhood supporters, could be key

project enablers in this phase.

Phase II: Design — The next phase for the space is design (Robichaud & Anantatmula, 2011). In this

step, it is expected that the project will be more active, especially in getting feedback and adapting. It is suggested to evaluate the space and identify issues, then create a place vision (Projects for Public space, 2016). In a concept of tactical urbanism, similar advice is proposed in the second phase:

identify a specific opportunity site, as well as clearly understand the root causes of the problems (Lydon & Garcia, 2015). In addition, they recommended to research and develop ways to address the defined problem. Graham (2012) found that regulatory challenges can be one key

barrier to temporary use. The challenges include issues about permits, insurance, and other

legal requirements. In phase two, Elliott (2015) cites that the urban collaboration project discusses the progress and initial setbacks the project faced during its initiation. Many researchers

emphasize the importance of partnerships in a project (Lydon & Garcia, 2015; Oswalt et al., 2011, 2013; Projects for Public space, 2016; Refill, 2018a, 2018b). Lydon and Garcia (2015) also add that project partners are important in the prototyping step. Partners that can support the project can come from institutions and administration support as well as political support, and mentoring and

technical coaching from intermediaries (Elliott, 2015; Frisk et al., 2014; Refill, 2018a, 2018b; Ziehl

& Oßwald, 2015). Although not explicitly mentioned, negotiation for the space could begin in this step as both (Lydon & Garcia, 2015; Projects for Public space, 2016) discussed securing places as a next step. The project can also get access to the landowner through temporary use brokers or

intermediaries (Refill, 2018a, 2018b). Refill (2018b) suggested to match demand and supply of

the temporary use space. Although they did not state clearly in which stage, these activities are likely to begin in this phase before starting the implementation in the next stage.

Regarding all activities in this phase, the stakeholders involved can be individuals, landowners,

municipalities, and intermediaries. Moreover, the possible key enablers can be (1) supporting partners and/or administrators; (2) matching or intermediation; (3) necessary information about permits and legal requirements; and (4) legal framework for the possible

land use. The permits and legal requirements of governments can be complex and time-consuming (Graham, 2012; Ziehl & Oßwald, 2015). Also, agreeing on a legal framework with the landowner is

28 another complicated issue. It can be achieved through the support of an intermediary (Refill, 2018a, 2018b).

Phase III: Implement — This phase involves getting everyone on board and securing necessary

resources in order to start the implementation. The name of this phase is also based on the third phase of Robichaud and Anantatmula's (2011) green project, to indicate the beginning of the implementation. Since stakeholder involvement, co-creation, and shared values are important in a complex project (Bishop & Williams, 2012; Graham, 2012; Löwstett, 2018; Oswalt et al., 2013; Refill, 2018a, 2018b; G. Silvius & Schipper, 2019), clarification and agreement on expectations of all stakeholders could be important before the implementation starts. In addition, financial and key administrative

support as well as the space should be secured before the implementation (Elliott, 2015; Lydon &

Garcia, 2015). The key administrative support could include permits, legal requirements, as well as a legal framework in order to use the space (Graham, 2012; Lydon & Garcia, 2015; Refill, 2018a, 2018b; Ziehl & Oßwald, 2015). For starting the project, it is suggested to create prototypes and do

short-term experiments to test and gather feedback (Lydon & Garcia, 2015; Projects for Public

space, 2016; Ziehl & Oßwald, 2015). According to Projects for Public space (2016), the experiment should be designed to be low-cost, fast to test, and should have potentials to create high impact. This experiment can be iterated to gather feedback and improve the prototype (Lydon & Garcia, 2015). The key stakeholders in this phase might be landowners, the municipalities, intermediaries, as well as individuals, communities, and neighborhoods. The possible key enablers in this stage include legal framework (Graham, 2012; Lydon & Garcia, 2015; Refill, 2018a, 2018b; Ziehl & Oßwald, 2015); secure financial support (Elliott, 2015; Lydon & Garcia, 2015); and flexibility, good

preparation, and understanding landowners’ conditions in negotiation (Frisk et al., 2014;

Graham, 2012). Moreover, since the project would create both monetary and non-monetary

values, communication about these values and expectations in complexity and temporary time period are also important (Bishop & Williams, 2012; Graham, 2012; Löwstett, 2018; Oswalt et

al., 2013; Projects for Public space, 2016; Refill, 2018a, 2018b; G. Silvius & Schipper, 2019). Effective

iterative experiments are key for prototyping (Lydon & Garcia, 2015; Projects for Public space,

2016). The experiment should (1) be light, fast, and cheap (Projects for Public space, 2016); (2) use available resources (Oswalt et al., 2013; Projects for Public space, 2016); and (3) promote co-production and shared values (Bishop & Williams, 2012; Graham, 2012; Löwstett, 2018; Oswalt et al., 2013; Projects for Public space, 2016; Refill, 2018a, 2018b).

Phase IV: Operate — A temporary use site setup and on-going operation are done in this phase.

The site building or renovation should be done at this stage as well as the on-going operation of the temporary use (Lydon & Garcia, 2015; Projects for Public space, 2016; Ziehl & Oßwald, 2015),. The operation should be flexible to demands and managed by collective self-organisation of the temporary use users (Ziehl & Oßwald, 2015). (Löwstett, 2018; Projects for Public space, 2016) also suggested on-going reevaluation and long-term improvement regarding the operation period. Based on these activities, the key stakeholders in this phase could be temporary users including

individuals, communities, and neighbourhoods. They could engage in a form of collective self-organisation (Ziehl & Oßwald, 2015). Key enablers might include using available resources and appreciating the incomplete (Oswalt et al., 2013; Projects for Public space, 2016); flexible operation and adjustment to demands (Ziehl & Oßwald, 2015); and on-going reevaluation and long-term gradual improvement (Löwstett, 2018; Projects for Public space, 2016).

29

Temporary use projects in Malmö

Context of temporary use projects in Malmö

Temporary use is considered to be context dependent (Bishop & Williams, 2012; Madanipour, 2018; Refill, 2018b). In order to understand temporary use projects in Malmo, the general context of Malmo will be described first.

Malmö is a city in the south of Sweden.

Population rate: 344,166 in 2019 (Malmö Stad, 2019b).

Population density: over 5,000 inhabitants per sq. mile at the urban area (United Nations, 2018; World Population Review, 2020).

Population growth: In 2019 the population increased by +1,4% (Malmö Stad, 2019b). Malmö’s average annual population growth of the last few years lies at 5,000 (Malmö Stad, 2019b). In general, the population of Malmö has increased statically over the last 70 years (Population Stat, 2020; United Nations, 2019). Only between 1970 and 1980 the population of Malmö dropped by 13% (Population Stat, 2020; United Nations, 2019). In the following 10 years, however, it increased again by 11% and between 2000 and 2010 the growth laid at 15% (United Nations, 2018; World Population Review, 2020).

Void rate (Percentage of vacant buildings): 7.5% in 2018 (Malmö Stad, 2019a)

Malmö is the third largest city and the fastest growing metropolis in Sweden (Malmö Stad, 2019a, 2019b). Reasons for the high increase of the population are high birth and influx rates. In Malmö, there are people living from 184 countries (Malmö Stad, 2019b). Almost one-third of its population was born abroad (Malmö Stad, 2019b). The average age of almost half of the city’s inhabitants lies below 35 (Malmö Stad, 2019b).

Malmö is a close neighbor city of Copenhagen in Denmark. Its urban development has been highly influenced by Copenhagen (Interviewee I).

The transition of Malmö and its opportunities for temporary use

Although Malmö is the fastest growing city in Sweden, the city still has a high vacancy rate. This contradiction could be caused by various reasons. According to Interviewee A, in the view of a researcher and historian, Malmö has begun to transform from an old to a modern city during the late 1960s, early 1970s. In the wave of city development, large parts of the city were torn down and became vacant and disposed for new development. When the economic crisis hit, the construction stopped and left the space empty in the middle of attractive areas in 1971. This is what is called “bomb holes”, as if somebody dropped bombs on the city (Interviewee A). Another wave of new vacancies came in the 1990s when the city faced massive deindustrialization, leaving shipyards and industrial sites unused. It was not until the 2000s that the city began to make use of the areas such as Western Harbour. The steadily growing population of Malmö, the establishment of Malmö University and the strategy of the city of Malmö to become a “city of knowledge”, could be reasons for a great demand for living and

30 working space in Malmö. To cover these needs, many vacant or abandoned places of Malmö are planned to be changed (Interviewee A). Transition, however, takes time, the combination of a fast-growing city with a high vacancy rate provides an interesting opportunity to examine temporary use projects, as it can be a “way to make the transition more, more easily flowing” (Interviewee A).

Innovative urban development in Malmö

"Malmö Innovations Arena'' was created at the end of 2016 and existed until December 2019. Its aim was to collaborate with academia, businesses, nonprofits and the public sector in response to the rising demand of living spaces in Malmö (Bigdelou, 2020). The goal of the Malmö Innovation Arena was to evolve, test and disperse concepts, methods and innovations. These aimed to increase the number of living apartments in a sustainable and cost-effective way, and transform the priority development areas into more sustainable residential areas (Bigdelou, 2020). The Malmö Innovation Arena was funded by the European Regional Development Fund, Vinnova and the city of Malmö (Bigdelou, 2020). The creation of this project shows that the city of Malmö is interested in new, innovative concepts of urban development. As temporary use projects can work as prototypes or experiments for new urban development approaches, the city of Malmö can be generally seen to be open for temporary use projects.

National and municipal requirements regarding temporary use projects

In Sweden, there are special requirements for the temporary use of public land. Public land is identified as land that belongs to everyone. This includes for example parks, squares and sites (Förening.se, 2020). Each time the use of land is temporarily changed from public to private use, the initiators of the change have to apply for a permit from the police of the concerned city (Interviewee G). The police checks the temporary use application regarding the compliance of order and safety regulations of the city (Interviewee G). Afterward, the referral is sent to the municipality of the city and checked regarding the following criteria: Will the land stay unharmed during the temporary use project? Is the maintenance of the land for the duration of the project guaranteed by the applicant? Does the project interfere with the city’s infrastructure(traffic, people passing by, etc.)? (Interviewee G).

In Sweden, there is a legal speciality, the “Allemansrätten”, the general right of public access (Förening.se, 2020). There are different translations for the meaning of this right. It could either be translated as the right that “everyone should have access to nature” (Förening.se, 2020) or as Interviewee G expressed, the right that “everyone should have the same chance, to do the same thing”. In the case of temporary use projects on public land in practice, the right implies that the land can just be provided to associations but not to individuals (Interviewee B and G). The reason, therefore, is that the municipality would not be able to provide public land to every single person, but regarding the right they would have to, if they would have provided it to one (Interviewee G).

Normally, temporary use is in a grey zone between citizen and government (Interviewee I). Bottom-up initiatives can get municipality sBottom-upport for the start of their project, but it is complicated to get continuous support (Interviewee I). Even though the municipality sees the benefits of the project and wants to continue the support, Malmö municipality can only provide support in the sense of an “activating role” not in a “maintenance role” (Interviewee I).

31

Objects of multiple case study

The three different temporary cases examined in this paper will be briefly presented in the following.

Project 1: Vintergatan Urban Garden

Figure 2: Vintergatan urban garden (Photo 1-3 by Vikell and colleagues (2020), photo 4 taken by an author on 10 April 2020)

The project “Vintergatan Urban Garden” is an urban cultivation project, which was started by three students of a project management class at Malmö University (Interviewee A, B and H). Regarding the project document, the urban garden was built on a former demolished area, waiting for its future development, in the north of Malmö (Sjölin & Lindblom, 2018). The land is owned by a construction company (Interviewee B and H; Sjölin & Lindblom, 2018). The project initiation was a bottom-up process, however the project founders got a lot of support from the landowner and a municipality employee, who acted as their intermediary (Interviewee A, B and H). Further support for the project was received from a Nature Protection Association, a student organization, the lecturer of the project management course and the cultivators of the garden (Interviewee H). The landowner assured the project founders the use of the space for three years, from 2019 until 2021 (Sjölin & Lindblom, 2018).

32

Project 2: Caroli Park

Figure 3: Caroli Church (Photos taken by an author on 12 August 2020)

“Caroli Park'', was a green indoor park in the culture heritage building, Caroli Church (Jaraba Molt & Mussie, 2019). This temporary use project was intended and identified as a temporary use experiment (Interviewee E). The project was again initiated by students in a project management class at Malmö University (Interviewee A, D, E and F). The abandoned church, which in former times had belonged to the Church of Sweden, was owned by a Shopping Mall when the project took place (Interviewee D and E). The indoor park was initiated in a bottom-up process without any financial support, but with the help of many volunteers (Interviewee A, D, E and F). The park was opened to the public for three weeks in September 2018 and it had 3604 visitors in total (Jaraba Molt & Mussie, 2019).

33 Figure 4: Caroli Park space and activities inside Caroli Church (Jaraba Molt & Mussie, 2019)

34

Project 3: Lokstallarna

Figure 5: Lokstallarna temporary use site (Photo 1-2: open house on 10 May 2019 (Lokstallarna, 2019), Photo 3-4 taken by authors on 25 April 2020)

Lokstallarna, a large 100-year former railway workshop, is owned by the governmental railway company, and located in Kirseberg, a city district of Malmö (Jernhusen, 2020a; Lokstallarna, 2020; Malmö stad, 2020). The whole space is approximately 18 hectare (Google Maps, 2020). The goal of this temporary use project is to establish a culture and craft center with creative businesses (Lokstallarna, 2020). The project was initiated by the municipality of Malmö in collaboration with the landowner (Lokstallarna, 2020; Malmö stad, 2020). The initiation of this project was a mixture of top-down and bottom-up processes (Malmö stad, 2020). The project started in 2019 and will continue until 2025 (Lokstallarna, 2020).