“A stronger Denmark” vs. “to welcome

people seeking refuge”

An analysis of Danish and Swedish newspapers’ and policy

documents’ framing of “the refugee crisis” and border controls

Diantha Jayananthan & Mette Kryger Pedersen

Malmö University

Date of examination: June 13, 2018 Media and Communication Studies:

Culture, Collaborative Media, and the Creative Industries

Faculty of Culture and Society, School of Arts and Communication Two-Year Master Thesis (15 Credits)

Supervisor: Tina Askanius Examiner: Bo Reimer

Abstract

The purpose of this thesis is to understand how Danish and Swedish news media and governments framed “the refugee crisis” in the context of the Swedish implementation of border controls in 2015 and the removal of external border controls in 2017. We operationalize framing theory (Entman 1993) to understand the differences and similarities in the framing of “the refugee crisis” in Denmark and Sweden. While the main focus is media representations, policy documents are included in the study to deepen the analysis and understand the similarities and differences across migration policies. Through a quantitative content analysis of 259 newspaper articles from eight Danish and Swedish newspapers, a framing analysis of ten policy documents and a qualitative framing analysis of the overall frames in the news articles and policy documents, we identified a dialectic relation of power between media and political discourse in both countries. We found that issues defined and represented in policy documents tend to reflect the challenges that news media define and the other way around. Even though Danish and Swedish newspapers and policy documents highlight similar problems, our data indicates clear differences in migration policies, in the two countries, in terms of the framing of asylum seekers, refugees and political events in 2015.

Keywords: asylum seekers, refugees, border control, bordering, migration policies, refugee crisis, framing, news media, policy documents.

Table of content

Lists of figures 1

1. Introduction 2

1.1 “Refugee chaos” vs. “refugee crisis” 3

1.2 The purpose and research questions 4

2. Literature review 5

2.1 Refugees, asylum seekers and migrants in media coverage 6

2.2. The refugee crisis as a term 6

2.3 The refugee crisis and media coverage 7

2.4 The relation between politics and media 9

2.5 Situating the study within migration and media research 10

3. Theoretical framework 10

3.1 Selection and salience 11

3.2 Who creates the frames? 12

3.3 Development, critique and limitations of framing theory 13

4. Methodology and empirical data 15

4.1 Research design 15

4.2 Data and sampling process 16

4.2.1 Newspaper articles from eight news outlets 16 4.2.2 Collecting newspaper articles 17 4.2.3 Collecting policy documents 19

4.3 Analytical framework 20

4.3.1 Analysing newspaper articles 20 4.3.2 Analysing policy documents 21 4.3.3 Qualitative framing analysis 22

4.4 Internal validity and ethical considerations 22

5. Understanding Danish and Swedish migration policies 24

5.1 Swedish policies: From an exceptionalist model to a civic turn 24 5.2 Danish policies: Civic selection and striving for Danish cohesion 25

6. Analysis 26

Part 1 27

6.1 Content analysis of news articles 27

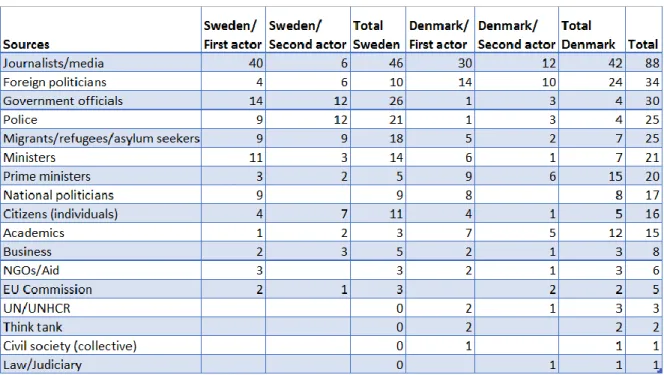

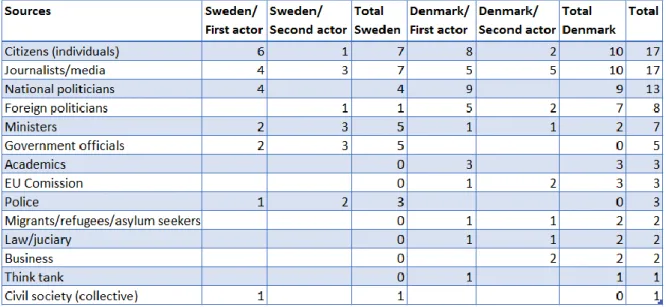

6.1.2 Who has a voice? 29

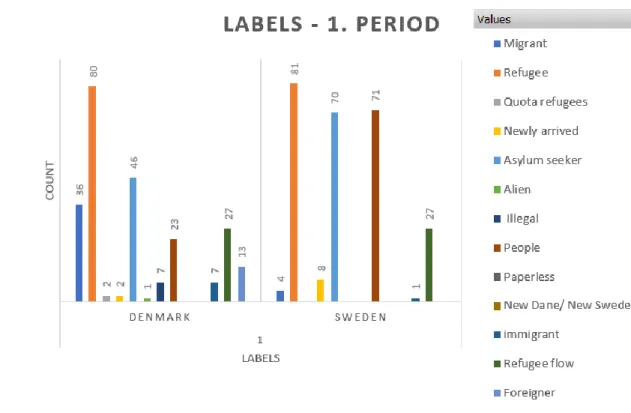

6.1.3 Description of people 31

6.1.4 Themes 33

6.2 Political strategies and national perspectives: a framing analysis of Danish and Swedish policy

documents 37

6.2.1 The communicator 38

6.2.2 The receiver 41

6.2.3 The texts 42

6.2.4 The culture 45

6.2.5 Summary of the policy document analysis 47

Part 2 49

6.3 Qualitative framing analysis 49

6.3.1 Defining the problem 49

6.3.2 Defined causes 53

6.3.3 Moral judgement 56

6.3.4 Solutions 60

6.3.5 Summary of the qualitative framing analysis 64

7. Concluding discussion 65

7.1 Negotiation of power in media and politics 65

7.2 The exertion of power in news media and politics 68

7.3 Limitations of our study and the need for further research 70

References 72

Literature 72

Empirical data 79

1

Lists of figures

Figure 1: The four comparative elements of the study 16

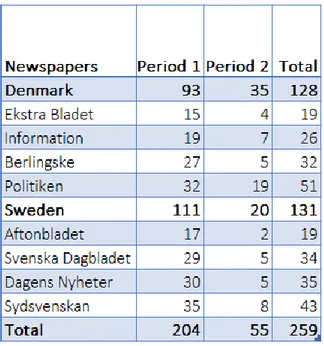

Figure 2: Distribution of articles in newspapers in the first and second periods. 27 Figure 3: The first and second sources given a voice in the first period. 30 Figure 4: The first and second sources given a voice in the second period. 31 Figure 5: Overview of the number of Danish and Swedish news articles that include

specific labels in the text to describe people coming to Denmark and Sweden in the first period.

32

Figure 6: Overview of the number of Danish and Swedish articles that include specific labels in the text to describe people coming to Denmark and Sweden in the second period.

33

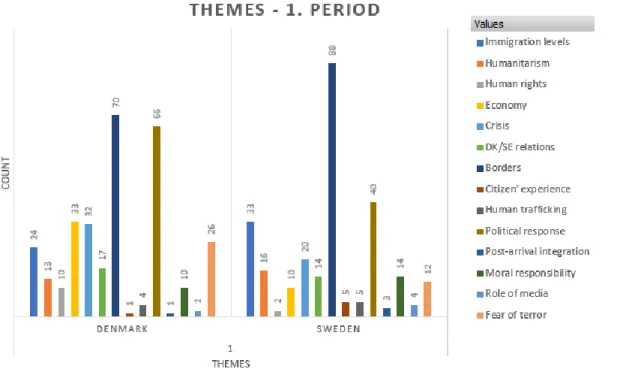

Figure 7: Themes that are included in the articles and how many times they appear in the sample in the first period.

34

Figure 8: Themes that are included in the articles and how many times they appear in the sample in the second period.

2

1. Introduction

In 2015, increasing numbers of asylum seekers reached the Northern region of Europe and crossed the borders of Denmark and Sweden. The arrival of thousands of people received a lot of attention in both Danish and Swedish news media, and the high influx was part of a period covered as chaotic and overwhelming (Kildegaard & Domino 2015, p. 4; Klarskov & Thobo-Carlsen 2015, p. 1; Mellin 2015, p. 20). Asylum seekers in Denmark and Sweden have caused administrative challenges, strains on governmental agencies, and not least contributed to political debates about national security, cultural differences and integration (Government Offices of Sweden 2015; Ministry of Immigration and Integration 2015; Government Offices of Sweden 2016; The Government of Denmark n.d.; Ministry of Immigration and Integration n.d.).

In both Denmark and Sweden, the large numbers of asylum seekers were treated as a burden creating a state of emergency. Thus, both the Danish and Swedish governments reacted with policy regulation aiming to limit the number of new entries (Government Offices of Sweden 2015; Ministry of Immigration and Integration 2015; The Government of Denmark 2016; Ministry of Justice 2017). In November 2015, the Swedish Government decided to implement temporary border controls1 (Ministry of Justice 2017). This decision became a turning point for

both Swedish asylum and migration policies and Danish politics as the Swedish government’s decision was assumed to increase the number of asylum seekers in Denmark. 18 months later, in May 2017, the Swedish government decided to remove the external2 border controls while

strengthening the internal3 border controls (Lönegård & Rogberg 2017, p, 7). The border

controls are the central aspect of our research as we analyse how Danish and Swedish news media have framed the refugee crisis in the context of these specific points in time. More specifically, we examine a delineated part of “the refugee crisis”4 by examining representations

of the Swedish government’s border controls in Danish and Swedish news media and policy

1 In this study, we use the term border controls to refer to the Swedish border controls and ID checks, as they are used to control borders. Some news media and governments perceive them as two different methods, which illustrates a way of framing border regulations.

2 External border controls refer to border controls and ID checks outside of Sweden on all public transportation entering Sweden.

3 Internal border controls refer to border controls on Swedish territory.

4 “The refugee crisis” is in quotation marks here to emphasize that we find that this is a problematic term (see 2.2. The refugee crisis as a term). In the rest of the study, we write the refugee crisis/the crisis without quotation marks.

3

documents. Our study provides insight into a specific sample of news media in a specific region and looks back at news coverage in two specific weeks, from November 12-19, 2015 – when the Swedish government implemented temporary border controls – and from May 1-8, 2017 – when the external border control was removed. We look at the framing of this delineation because frames in news texts and policy documents represent imprints of power that register the identity of actors or interests that compete to dominate the text (Entman 1993, p. 55).

News media have an important role with respect to how different aspects of the European crisis are framed, portrayed and discussed in public. Moreover, local and national news media have an influence on public opinion (Entman 1993, p. 57; Berry et. al. 2015 p. 5; Stjernborg et. al. 2015, p. 22; Hellström & Hervik 2018). Thus, it is important to examine how the media portrayed the arrival of asylum seekers and refugees and framed the crisis to understand how this group of people is represented in media coverage and politics because representations of people and events affect the way people relate to the discussion of this crisis.

1.1 “Refugee chaos” vs. “refugee crisis”

A source of inspiration for our study is the TV debate programme, Debatten om flygtninge: Danmark møder Sverige [The debate about refugees: Denmark meets Sweden] (2015) broadcasted on both the Danish channel, DR2, and the Swedish channel, SVT1, on September 17, 2015. In this programme Danish and Swedish actors discussed the refugee crisis and ways to handle the increasing number of asylum seekers. This debate programme clearly demonstrated fundamental differences in the political cultures of Sweden and Denmark specifically in relation to migration and asylum questions and political responsibilities for introducing newcomers. For instance, it is discussed how the overall situation has widely been referred to as “refugee chaos” in Denmark, while the term “refugee crisis” has been the most common term in Sweden (ibid.). Throughout the debate, actors from the two countries have indicated clear cultural differences in the perception of accepting asylum seekers, how these people are described, and how the situation in both countries and Europe in general should be handled. This difference is especially clear between Danish and Swedish politicians. Swedish politicians emphasize the importance of protecting the right to asylum, protecting people in need and in flight, and strengthening the cooperation between EU member states. Danish politicians mainly focus on the situation in Denmark, Danish cohesion and stress that newcomers must contribute to the Danish society in terms of

4

labour and active citizenship (ibid.). This TV debate programme sparked our interest in the migration policies of the two neighbouring countries.

Moreover, we both worked as research interns at Malmö University in autumn 2017 on projects about refugees who have arrived in Europe since 2015. The internship experience broadened our knowledge about asylum and migrant policies in Denmark and Sweden as well as Danish and Swedish newspaper coverage of the refugee crisis. The experience that we acquired during our internships motivated us to continue working on this topic and gain a deeper understanding of how Swedish and Danish news media and policy documents framed the refugee crisis in the context of border control and migration policies.

1.2 The purpose and research questions

The purpose of this thesis is to understand how Danish and Swedish news media frame the refugee crisis through the prism of border controls. While the main focus is media representations, policy documents are included in the study to deepen the analysis and understand migration policies in Denmark and Sweden, respectively.

Our study focuses on one border region, two national contexts and two specific time periods. We aim to understand similarities and differences in the framing of the refugee crisis in Denmark and Sweden. Moreover, we aim to understand the dialectic relationship between media and policy discourse on these subject matters and in relation to each other. Therefore, we analyse how Danish and Swedish news media represent the Swedish government’s implementation of border controls – and subsequent removal– of external border controls, and we analyse Danish and Swedish policy documents about asylum and migration. Overall, we examine media’s representation and framing of these issues and discuss the possible consequences of this framing to understand the relation between media and politics.

We present our analysis in two parts, approaching the study through the following research questions guided by Entman’s (1993) framing theory. The first two research questions concern how the refugee crisis has been framed in news media and policy documents. We answer this part through a content analysis of a sample of Danish and Swedish newspaper articles, and a framing analysis of Danish and Swedish policies concerning asylum and migration policies.

5

Part 1

1. How did news media in Denmark and Sweden frame the refugee crisis in November 2015 when the Swedish government implemented border controls and in May 2017 when the external border controls were removed?

2. How do the Danish and Swedish governments frame migration and asylum in policy documents?

Part 2

The second part of our analysis focuses on key themes and patterns identified in the first part of our analysis. The aim is to understand the differences and similarities in the two countries over the two different time periods. Moreover, we aim to understand the differences and similarities of the news media’s and the government’s framing of the refugee crisis in the context of border controls. We approach this part of our analysis with the next question:

3. How can we understand the differences and similarities in framing of the refugee crisis in the context of border controls and Danish and Swedish migration policies across two time periods and between the media's and government's framing?

2. Literature review

In this chapter, we present how scholars have previously studied asylum and migration issues and the refugee crisis in media studies. First, we discuss how researchers have engaged with media representations of asylum seekers, refugees and migrants and their findings. We continue with a discussion about the term the refugee crisis and how scholars approach this term critically. Moreover, we look at how others have studied the refugee crisis and how scholars have looked at the relationship between politics and media. Lastly, we place our study and contribution within the media and migration research field.

6

2.1 Refugees, asylum seekers and migrants in media

coverage

The representation of refugees, asylum seekers and migrants in media has been studied from many different perspectives. Several framing analyses of media coverage of refugees, asylum seekers and migrants at different points in time and in different national contexts have shown that asylum seekers, refugees and undocumented migrants are often framed as either a threat or a victim (Van Gorp 2005; McKay et. al. 2011; Ihlen & Thorbjørnsrud 2014; Horsti 2013; Lawlor 2015). However, some scholars argue that these two frames are not competing, as they often support the same ideological position and may be combined in a frame of reason/rationalization (Horsti 2013, p. 79; Triandafyllidou 2018, p. 198). Based on an automated content analysis of Canadian print media coverage over a 10-year period, Lawlor and Tolley (2017) found that there are distinct differences between the framing of immigrants and refugees. They found that immigrants are frequently positively associated with economic considerations, while refugees are more frequently negatively associated with validity considerations (Lawlor & Tolley 2017, p. 985). Further, they argue that findings from studies of media coverage in one country can be applied to other contexts because “the media’s structural and institutional features are consistent across many Western liberal democracies” (Soroka, 2014 cited in Lawlor & Tolley 2017, p. 968). However, recent findings from two cross-European studies on the media’s coverage of the refugee crisis in 2015 showed that there are significant differences in the coverage of asylum seekers and immigrants across Europe (Berry et. al. 2015, p. 10; Georgiou & Zaborowski 2017, p. 3). Further, Berry et. al. (2015) state that “one size does not fit all” for media work on refugees (Berry et. al. 2015, abstract).

2.2. The refugee crisis as a term

Triandafyllidou (2018) uses the terms “refugee crisis” and “refugee emergency” interchangeably to refer to the high influx of asylum seekers and irregular migration that Europe experienced during 2014-2016 (Triandafyllidou 2018, p. 200). She argues that the crisis was a multiple crisis: “a crisis in terms of unprecedented volume and pace of refugee and migrant flows; in terms of the receiving countries’ asylum reception policies; and with regard to EU politics and policies” (ibid., p. 200). Georgiou and Zaborowski (2017) argued that the European press had a key role in framing refugees’ and migrants’ arrival in Europe in 2015. Further, Musarò and Parmiggiani

7

(2017) studied the media’s role in shaping perception and policies in Italy concerning the migrant crisis. They argue that the “depoliticized politics, based on compassionate care and technocratic control, contributes to the construction of the image of the Mediterranean as a ‘migration crisis space’, in which the role of culpability is totally misperceived in what has become a routine production of grave harm” (Musarò & Parmiggiani 2017, p. 254).

Krzyżanowski et. al. (2018) discuss the discourse of the refugee crisis and argue that this term is inaccurate. The use of crisis is “stigmatizing” for the migrants and adds “unnecessarily alarmistic connotation to the discourse”, as well as the term has a specific political function (Krzyżanowski et. al. 2018, p. 3). They argue that the refugee crisis has been developed by the media and political discourse “to legitimize the alleged urgency, including various measures, that were or were supposed to be taken in recent months and years” (ibid. p. 3).

2.3 The refugee crisis and media coverage

The refugee crisis as it was dubbed by the media and politicians in 2015 has recently been studied from many different perspectives. A growing body of literature focuses on the media’s coverage of the refugee crisis and takes a variety of approaches to study the events in 2015. Several scholars look at the refugee crisis from a national perspective focusing on how this crisis has influenced the media and political discourse in one country (Dahlgren 2016; Boukala & Dimitrakopoulou 2016; Greussing & Boomgaarden 2017; Musarò & Parmiggiani 2017; Rheindorf & Wodak 2018; Krzyżanowski 2018). Further, many studies take a cross-national perspective studying discourse across multiple countries in Europe, the Middle East and Canada to gain a more holistic perspective of the media’s influence on framing the crisis (Berry et. al. 2015; Chouliaraki & Stolic 2017; Chouliaraki & Zaborowski 2017; Abid et. al. 2017; Georgiou & Zaborowski 2017; Mortensen et. al. 2017; Triandafyllidou 2018).

While most of these studies base their findings on the analysis of texts such as print and online news articles, social media and speeches, a handful of scholars focus on visual data such as newspaper headline images (Chouliaraki & Stolic 2017), instant news icons (Mortensen 2016) and migrant selfies (Chouliaraki 2017). The many images that appeared in news media during this period contributed to the framing and discourse about the situation. Some images like the image of the three-year old Alan Kurdi lying dead on a beach in Turkey changed media and

8

political discourse around Europe because the image came to symbolize the tragedy of the Syrian people and all the people fleeing war and seeking refuge in Europe (Mortensen et. al. 2017; Triandafyllidou 2018). Chouliaraki and Stolic (2017) conducted a conceptually-driven semiotic analysis of newspaper headline images of news in five European countries at three key moments from June-December in 2015. They found that “regimes of visibility,” how refugees are situated in news images, are “key spaces of moralization that produce and regulate the public disposition by which we collectively take responsibility for the plight of distant others” (Chouliaraki & Stolic 2017, p. 11). Based on their empirical data, Chouliaraki and Stolic constructed a five-part typology, which situates refugees in different perspectives, concluding that all these “regimes of visibilities” fail to address refugees and migrants as human beings (Chouliaraki & Stolic 2017, p. 12).

The media have long been criticized for not considering the views of ethnic minorities, asylum seekers and refugees important enough to interview, quote or mention their names (Wal et al. 2002 in Horsti 2008, p. 47). Similarly, Chouliaraki and Zaborowski (2017) found that politicians speak in the news and refugees do not. They argue that this hierarchy of voices leads to a triple misrecognition of refugees as political, social and historical actors, which has serious implications on both refugees and on Europe’s national public (ibid. p. 616). In addition, several studies address the lack of migrant and refugee voices in the news coverage (Horsti 2008; Alhayek 2014; Berry et. al. 2015; Chouliaraki & Zaborowski 2017; Chouliaraki & Stolic 2017; Georgiou & Zaborowski 2017). Based on a content analysis of news coverage from eight European countries, the Council of Europe’s report on media coverage of the refugee crisis found that refugees and migrants were given limited opportunity to speak of their experiences and suffering, and female refugees and migrants were hardly ever heard across Europe (Georgiou & Zaborowski 2017, p. 3).

Further, Georgiou and Zaborowski’s (2017) and Berry et. al.’s (2015) content analyses of newspapers in eight and five countries, respectively, give an overview of trends in the media coverage of people arriving in Europe in 2015 as well as an insight into the press culture that was agenda-setting during this period (See Berry et. al. 2015; Georgiou & Zaborowski 2017). The reports identified large variations in the way that the press reports on asylum and immigration in different countries. There is a strong contrast between East and West, receiving

9

and non-receiving countries, as well within the national press systems (Berry et. al. 2015; Georgiou & Zaborowski 2017). Both reports stress the media’s role in providing information about the new arrivals and framing these events as well as influencing public and elite political attitudes towards asylum and migration (Berry et. al. 2015; Georgiou & Zaborowski 2017). As such, Mortensen et. al.’s (2017) analysis of the editorial mediation and response to the Alan Kurdi photographs in Danish, Canadian and UK newspapers revealed editorial self-reflexivity.

2.4 The relation between politics and media

A number of recent studies have examined how media influence different political issues across national contexts with different results. Hayes et al. (2007) studied how Canadian news coverage of health stories reflected the issues embedded in the health policy documents. They found that the “overall prominence of topics in newspapers is not consistent with the relative importance assigned to health influences” in the policy documents (p. 1842). Fawzi (2018) studied energy policies in Germany as a case to examine media’s impact on all stages of the political process. She found that media coverage has a strong influence on the political processes with only the implementation stage being less influenced. In another study, van der Pas et. al. (2017) apply the concept “political parallelism” to examine the connection between newspapers and political parties in the Netherlands. They conclude that political actors and newspapers influence each other in terms of the topics each of these institutions address (van der Pas et. al. 2017, p. 505). Simultaneously, both institutions benefit from this reciprocal connection as politicians gain attention and space in media to reach the public and journalists’ reports are “legitimized by the adoption of parliamentarians” (van der Pas et. al. 2017, p. 506). Furthermore, Ciaglia (2013) conducted a comparative analysis of the bond between media and politics and how this varies in the national contexts of United Kingdom, Germany and Italy. He found that the link between politics and media constantly is present, but the degree and implications of this link varies (pp. 552-553). In another study, Pallas et al. (2015) argue that the mediatization of government agencies can be understood as a pull rather than a push factor. The political agencies want to interact with media rather than they are forced to adapt to media (p. 1050). Their findings support “a general picture of government agencies putting great value on the media and investing scarce resources in media-related rules and activities” (p. 1060).

10

2.5 Situating the study within migration and media

research

Our study can be placed in the research field of media coverage on migration because it contributes to the field of research by providing insight into a specific sample of news media coverage on the implementation of Swedish temporary border controls in 2015 and the removal of external border controls in 2017 as a consequence of the refugee crisis in a specific region. Moreover, our study includes an analysis of policy documents regarding migration and asylum in two neighbouring countries on which there has not been done much research.

As shown in this literature review, the media’s coverage of the refugee crisis in 2015 has already been studied by a number of scholars from multiple perspectives. However, few have made studies with a border perspective in relation to policy documents and media coverage. The purpose of our thesis is to understand the similarities and differences with respect to how Danish and Swedish news media and governments framed the refugee crisis during the Swedish government’s implementation of border controls and the removal of the external border controls. Our study examines two national contexts and two specific time periods. We argue that it is important to examine how media and governments in both countries frame these situations to understand the differences and similarities of the framing. By including asylum and migrant policy documents, we discuss how news media and governments compete and negotiate over frames concerning the refugee crisis. We are aware that people get news from multiple sources today, in different languages, and that neither readers nor news outlets live inside information bubbles. Nonetheless, news media influence public opinion (Entman 1993, p. 57; Berry et. al. 2015 p. 5; Stjernborg et. al. 2015, p. 22; Hellström & Hervik 2018).

3. Theoretical framework

In this chapter, we discuss the theoretical framework of our thesis. We apply framing theory to uncover our research questions and mediatization to understand the relationship between media and politics. First, we discuss Entman’s (1993) definition of framing. Then, we discuss the power and creators of framing. Lastly, we discuss the development, critique and limitations of framing perspectives.

11

3.1 Selection and salience

Framing theory is a perspective applied in many academic traditions. Framing is often used to analyse political communication and journalistic news coverage (Hjarvard 2015, p. 104). We use framing theory to understand how journalists and politicians frame the refugee crisis in the context of border controls. We operationalize Entman’s (1993) salience-based definition of framing to structure the analyses.

For Entman, framing is “to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation of the item selected” (Entman 1993, p. 52). Van Gorp (2005) defines a frame as a “persistent meta-communicative message that specifies the relationship between elements connected in a particular news story and thereby gives the news coherence and meaning” (Van Gorp 2005, p. 503). According to Entman, framing is about selection and salience, which provides a method to describe the power of a communicating text (Entman 1993, p. 51). Entman explains that to select and make an aspect of reality more salient in a communicating text is to make a piece of information more noticeable, meaningful, or memorable to the audience, which increases the chance that the receiver will perceive, discern meaning, process or store the information and meaning in their memory (ibid. p. 53).

Furthermore, Entman (1993) argues that frames have four functions or reasoning devices: to define problems, diagnose causes, make moral judgements and suggest remedies. The four framing functions can appear in one sentence in a text, but all are not necessarily present in one particular text. These framing functions are used to select and highlight specific aspects of reality, and the highlighted elements are used to construct an argument of problems and their causation, evaluation and or solution (ibid. p. 53). Garvin and Eyles (2001) argue that framing is useful when studying policy problems because Entman’s framing functions link the defined problem to the proposed solutions (ibid., p. 1176). Moreover, Hjarvard (2015) argues that this definition of framing has made it easier for scholars to operationalize the framing concept in text analyses because it makes it possible to look for and identify certain aspects, which together create a frame (Hjarvard 2015, p. 105).

12

Entman (1993) proposes that frames exist in all aspects of the communication process: the communicator, the text, the receiver and the culture. Similar to Hall’s (1973 in Hjarvard 2015, p. 111) encoding and decoding communication model with a communicator, a text and a receiver, Entman (1993) argues that culture as a whole is important to understand how opinions are created (Entman 1993, p. 53). The existing frames within a culture or group influence how frames in texts are understood (Hjarvard 2015, p. 105). Garvin and Eyles (2001) argue that these four locations can help identify how participants in the policymaking process guide policy solutions (p. 1177). In a qualitative frame analysis of asylum seekers in Finnish news, Horsti (2013, p. 83) argues that framing of asylum seekers takes place in the cultural context of a text, a perspective which we apply in our study.

3.2 Who creates the frames?

The use of framing is important in political power. Matthews and Brown (2011) exposed how tabloid newspapers can perform as a “claims maker, producing coverage that establishes, legitimates and demonstrates the UK immigration system as in crisis” (Matthews & Brown 2011, p. 813). Their study challenged the existing explanations of elite influences as their study revealed how tabloid news rather than government viewpoints frame the character and contours of campaign representations, which leads to the question: who determines the frame of the crisis, the media or the government? (ibid.). According to Murphy and Maynard (2000 in McKay et al. 2011), the way an issue is framed in the media and public discourse has much to do with who the framing is created by (ibid, p. 612). Further, Scheufele (1999) questioned whether journalists’ frames of an issue are mostly “a function of how elites, interest groups, or other sources frame an issue? Or, do journalists themselves interpret issues based on frames conveyed to them by other news sources?” (ibid, p. 117).

Politics are influenced by mediatization. Mediatization is a concept that unfolds the social and political processes influenced by the logic of the media (Schulz 2004; Strömbäck 2008; Hjarvard 2013). According to Ciaglia (2013), there has been a shift in modern democracies, in which politicians have acknowledged the importance and impact of media on their political success. Simultaneously, politicians have become more dependent on media, as media are perceived as a significant source of information (Ciaglia 2013, p. 543). For instance, politicians “adjust their behavior and the presentation of their messages in order to accommodate the news values and

13

formats of journalism” (Schudson 1989, p. 143). According to Strömbäck (2008), politics are about “collective and authoritative decision making” (p. 233). In these processes of decision making, politicians and political parties are the primary actors that define societal problems, solutions and decide how these are addressed to the public (Patterson 1993 in Strömbäck 2008, p. 233). Thus, it is important for politicians to have a voice in the media because media can be used strategically “to gain power and legitimacy in policy processes” (Tresch 2009, in Korthagen 2015, p. 618).

The way an issue is framed influences the discourse about an issue during a period. Foucault defined discourse as “a group of statements which provide a language for talking about – a way of representing the knowledge about – a particular topic at a particular historical moment” (Hall, 1992, p. 291 in Hall 2013 [1997], p. 186). Furthermore, Foucault argued that “what we think we ‘know’ in a particular period” about a specific topic influences how we regulate, control and punish that issue (Hall 2013 [1997], p. 189). This has an influence on the “regime of truth” (Hall 2013 [1997], p. 189), which further can be related to the concept of “news wave”, where a frame of a news story from one news outlet is picked up by other journalists and news media (Fishman 1980 in Scheufele 1999, p. 117).

These reflections about who creates the frames are important for our analytical framework because framing influences what is defined and judged as the problem, causes and solutions. We operationalize these considerations by examining who is given a voice in the news articles, and who are the senders of the policy documents to identify how these actors define asylum and migration.

3.3 Development, critique and limitations of framing

theory

Framing theory has often been used to show how news texts not merely report on reality, but include important choices, which provides meaning to events and mirror the actor’s interests (Hjarvard 2015, p. 105). The representation and framing of reality is never neutral but is guided by choices that all have consequences for how we understand reality (Hjarvard 2015, p. 105; Price, Tewksbury, & Powers 1995, p. 4 in Scheufele 1999, p. 107). Thirty years ago, Schudson (1989) argued that “journalists make the news” (p. 263). He explained by referring to Murdock

14

(1973 in Schudson 1989) that “news ‘coincides with’ and ‘reinforces’ the definition of the political situation evolved by the political elite” (p. 268). To a certain extent this still holds true, although much has changed in 30 years.

Five years ago, Kammer (2013) argued that journalism was undergoing a process of mediatization, in which society becomes increasingly dependent on media and its logic (Hjarvard 2008, p. 113 in Kammer 2013, p. 144). Despite the increasing dependency on the logic of media, Hjarvard (2015) argues that framing is still useful for systematically analysing texts to understand their possible connection to the construction of opinion (Hjarvard 2015, p. 112). A framing analysis can be both inductive and deductive by either identifying specific frames within the texts or looking for existing defined frames in the texts such as topic, specific frames or generic frames (ibid. p. 111).

Framing theory is often criticized for being too vague theoretically and empirically because it can be used to explain basically everything, especially within the sociological tradition of framing (Scheufele 1999, Hjarvard 2015; Cacciatore et al. 2016, p. 15). Cacciatore et al. (2016) criticize emphasis-based framing studies for arguing that any observed effect “may be the result of difference in the persuasive power or quality of a given message, rather than differences in the way the same information is presented” (Cacciatore et al. 2016. p. 13). Therefore, they argue for a narrower definition of framing to better distinguish between the effects of framing and the effects of agenda-setting. They propose moving away from the emphasis-based framing operalizations towards equivalence-based definitions “that are more directly tied to alterations in the presentation of information rather than the persuasive value of that information” (Cacciatore et al. 2016, p. 15). Hjarvard (2015) acknowledges the relevance of this critique and the problem of framing being too broad and vaguely theorized. However, he argues that Cacciatore et al.’s (2016) narrow definition of framing can only be conceptualized and operationalized through experimental conditions and not in the real world (Hjarvard 2015, p. 109).

It is important to emphasize that the way we use framing cannot be used to study how opinions are created or affected. We draw on mediatization theory to understand the relation between politics and media. Therefore, our study can contribute with a discussion about how news media

15

and governments in Denmark and Sweden frame the refugee crisis in the context of borders, migration and asylum and what consequences these frames may have when migration and asylum issues are positioned in a certain way. However, our study cannot discuss how specific ways of framing this topic influence public opinions.

4. Methodology and empirical data

In this chapter, we describe the methodology applied in our study. We describe how we selected, collected and analytically approached our empirical data to help answer our research questions. Furthermore, we discuss the limitations of the data and discuss ethical considerations encountered in this study.

4.1 Research design

We employ a mix of methods to understand how Danish and Swedish news media framed the refugee crisis through implementation of border controls and removal of external border controls by conducting a quantitative content analysis and a qualitative framing analysis (Blaikie 2009, p. 218). The empirical data consists of two separate data collections: newspaper articles and policy documents. The newspaper articles stem from four Swedish newspapers and four Danish newspapers from two specific weeks. The first period is a week in November 2015, when the Swedish temporary, border controls were implemented, and the second week is in May 2017, when external border controls were removed. The policy documents include Swedish and Danish policy documents that concern asylum and migration policies from 2015-2017.

16

Figure 1: The four comparative elements of the study

We focus on these periods and newspapers to understand how the implementation and removal of border controls were framed in news media during this time in Denmark and Sweden. Moreover, we include policy documents concerning migration and asylum policies from the two neighbouring countries to understand how the refugee crisis was framed by the Danish and Swedish governments. Altogether, the two datasets help us understand the similarities and differences in the framing of the refugee crisis in news coverage and policy discourse within two specific national contexts and two specific time periods. We use these four elements to examine a delineated area of the refugee crisis (See figure 1).

4.2 Data and sampling process

The data consists of articles from newspapers in Denmark and Sweden and policy documents from both governments. In the following section, we elaborate on the data and the sampling process.

4.2.1 Newspaper articles from eight news outlets

The newspaper articles were collected from four Danish newspapers: Berlingske, Ekstra Bladet, Information and Politiken, and four Swedish newspapers: Aftonbladet, Dagens Nyheter, Svenska Dagbladet and Sydsvenskan. The newspapers are all national, daily papers positioned differently in

17

terms of readership, type of journalism and political stance. We selected these newspapers to gain and insight into how differently traditional, national news outlets framed the refugee crisis and border controls in Denmark and Sweden.

The Danish Newspapers

Ekstra Bladet is a tabloid, whose readers are mainly workers and people outside the labour market, including retired people, whose income is in the lower quartile (Ekstra Bladet n.d.). In 2017, Ekstra Bladet had 103,000 readers (Kantar Gallup 2018). Politiken’s readers are primarily highly educated workers (Tabloid n.d.) and in 2017, the newspaper had 263,000 readers (Kantar Gallup 2018), which makes it the second largest daily newspaper in Denmark (Tabloid n.d.). Both Politiken and Ekstra Bladet are described as independent, radical-social-liberal newspapers (JP/Politikens hus n.d.). In 2017, Berlingske had 160,000 readers (Kantar Gallup 2018), and it has a liberal-conservative orientation (Euro|topics: Berlingske n.d.). Information provides critical journalism and is independent of political parties as well as economic interests (Den store danske: Information n.d.). The political orientation of Information is left-wing (Euro|topics: Information n.d.), and in 2017, the newspaper had 90,000 readers (Kantar Gallup 2018).

The Swedish Newspapers

Dagens Nyheter is the leading newspaper in Sweden, and it has a liberal orientation. In 2017, it was read by 625,000 people (Kantar SIFO 2018). Svenska Dagbladet is positioned as independent and conservative (Schibsted Media Group n.d.). In 2017, the newspaper had 376,000 readers (Kantar SIFO 2018) and most of these have a higher education (Tabloid n.d.). More than half of Sydsvenskan’s readers also have a higher education, are full-time employees and live in the area of Skåne (Tabloid n.d.). In 2017, Sydsvenskan had 186,000 readers (Kantar SIFO 2018). Sydsvenskan is politically positioned as independent liberal (Euro|topics: Sydsvenskan n.d.). In 2017, Aftonbladet was read by 538,000 readers (Kantar SIFO 2018). This newspaper is a tabloid with a Social Democratic identity (Aftonbladet info n.d.).

4.2.2 Collecting newspaper articles

We collected the newspaper articles through the Swedish media database, Retriever (retriever.se) and the Danish media database, Infomedia (infomedia.dk). The search for the first period was limited to articles published from November 12, 2015 to November 19, 2015. The second period

18

was limited to articles published from May 1, 2017 to May 8, 2017. The first day of the period indicates either the day of the implementation of border controls or the removal of external border controls. The specific search string for both periods included border, asylum and refugee. We applied broad search tags to include all articles that touch upon borders, asylum or refugees. The specific search strings were:

Danish database: grænse* AND asyl* OR flygtning* Swedish database: gräns* AND asyl* OR flykting*

The initial search on Infomedia matched 319 articles for the first period and 101 articles for the second period. Having excluded false positives, we reduced the number of articles to 93 in the first period and 35 articles in the second period. False positives in the Danish search included articles without the word, grænse [border], but e.g. the Danish word begrænse [limiting] in a context not relevant for our topic. Moreover, some articles only included the word grænse and not flygtning [refugee] or asyl [asylum] and were not relevant for our topic. These articles concerned e.g. borders outside Europe and were not related to asylum or refugees. Other false positives did include the word, grænse, but as boundaries in contexts of other topics than refugees and asylum. Some articles did not include any of the words, grænse, asyl or flygtning, which could have been caused by an error. We conducted the search several times, nonetheless, the same articles appeared each time. Lastly, we excluded letters from readers because we specifically engage with how journalists and the newspapers represent issues concerning the refugee crisis and borders, and not the opinions of the public.

The first search on Retriever matched 135 articles for the first period and 20 articles for the second period. Having excluded false positives, we reduced the articles in the first period to 111 and the second period remained the same with 20 articles. The false positives in the Swedish search regarded articles that included the word gräns [border] but in relation to other topics than asylum or refugees. E.g. articles about IS and their territories in Iraq and Syria. Additionally, a few articles did not include the word, gräns. Some articles that employed the word, gräns, as boundaries/limit in phrases such as “there must be a limit” in relation to the topic, were included in the data sample. The use of the word, gräns, as boundaries and limits can be relevant to understand the mental state of boundaries and limitations in relation to issues concerning

19

refugees and asylum. While sorting for false positives, we noticed that some articles in Svenska Dagbladet appeared twice, however, with edited headlines and/or images and in some cases a long and a short version of the same article. These articles were edited on the same date, one version published in the morning edition and the second in the evening edition. We decided to include both versions in the data collection and mark the occurrence of the similar/edited articles in the coding table because the headline in the evening version was different compared to the morning version.

The total number of newspaper articles in the sample is 259 articles: 128 Danish articles and 131 Swedish articles.

4.2.3 Collecting policy documents

The policy documents were retrieved from websites of the Swedish and Danish governments, ministries and services. We selected five Swedish policy documents and five Danish policy documents according to the following criteria:

● The policy documents must be published by governments, governmental departments or ministries in Denmark or Sweden.

● The policy documents must be published between 2015-2017.

● The policy documents must concern asylum and migration rules or regulations hereof.

The selected documents provide information about policy proposals and changes regarding asylum, migration, and border controls. They exemplify how the Swedish and Danish governments address issues as well as political solutions. The gathered sample includes press releases, governmental reports and publications. We were mainly able to find documents published in Danish from the Danish government except from the document, English information about changes to regulations applied in the area of asylum (Ministry of Immigration and Integration 2015). However, we found several Swedish governmental publications in English. Thus, we chose four Swedish documents published in English and one report published in Swedish.

20

4.3 Analytical framework

We operationalize Entman’s (1993) salience-based definition of framing and contextualize his understanding of framing to structure our two-fold analysis. In the first part of the analysis, we first conduct a content analysis of the sampled newspaper articles, which provides an overview of recurring themes and terms to help examine the salience of the selected aspects of reality. Moreover, we conduct a framing analysis of the collected Danish and Swedish policy documents, in which we examine what Entman (1993) proposes as the four key locations of a communication process: the communicator, the text, the receiver and the culture. Through these four locations, we examine how frames are “communicated, reflected, reinforced or challenged” in relation to issues about migration and asylum in Denmark and Sweden (Garvin & Eyles 2001, p. 1177). In the second part of the analysis, we combine the key findings from the first part of the analysis to understand the differences and similarities of the framing of the refugee crisis in the context of border regulations in Denmark and Sweden at two different points in time. This part of the analysis is structured in accordance with Entman’s (1993) four framing functions: the defined problems, the defined causes, moral judgement and suggested solutions.

4.3.1 Analysing newspaper articles

To uncover the first research question, we coded all the news articles with the coding table described below (see Appendix 1) and conducted a quantitative content analysis in which we looked for main patterns and characteristics in the articles.

Coding newspaper articles

We created a coding table (see Appendix 1) that coded for a number of parameters within the news articles, which were selected with the intention of answering our research questions in the best possible way. We employed an inductive approach to identify specific frames within the texts by identifying a number of different parameters that together create a frame (Hjarvard 2015, p. 111). In the coding table, we coded for sources (first actor, second actor), inclusion of citizen and migrant/refugee voices, labels in both Danish and Swedish, themes in coverage, moral and value judgements and metaphors. We coded for the first and second actors to gain insight into the individuals who are given a voice in the articles. In addition, we marked when voices of citizens and newcomers were represented or cited to locate when and if the voices of

21

these actors were included. To get an overview of how newcomers and their positions are represented, we coded the different labels utilized in the newspapers. To determine dominant and recurring topics in the news articles, we included a category covering themes apparent in each text. To determine the moral value/judgement of the articles, we judged whether the articles had a generally positive, negative or neutral tone. Whether an article was coded as being either negative, positive or neutral depended on the use of language, use of sources and whether it expressed explicit opinions towards or against the situation. Overall, we strove to uncover as many qualitative characteristics within the news sample as possible and to limit subjective assessments in our content analysis through these coding categories and variables. (See related coding categories, variables and descriptions in Appendix 1).

Content analysis

Based on the coding table, we conducted a univariate descriptive content analysis of the collected news articles (Blaikie 2009, p. 209). We focused on the single variables that are coded for in the newspaper articles to report the distribution and to produce a summary of characteristics within the sample (ibid., p. 209). According to Entman (1993), a content analysis should identify and describe frames to determine textual meaning and to “avoid treating all negative or positive terms or utterances as equally salient and influential” (Entman 1993, p. 57). The descriptive content analysis provides an overview of recurring themes and terms in the news sample, which helps us understand the salience of different elements in the texts (ibid. p. 57).

4.3.2 Analysing policy documents

To answer the second research question, we conducted a framing analysis of the policy documents, structured according to Entman’s four proposed locations: communicator, text, receiver and culture (Entman 1993, p. 53). According to Entman (1993), these four locations can be used to identify, evaluate and recommend action on issues within the Swedish and Danish policy documents (ibid., p. 53). This analytical approach is employed to understand the similarities and differences in the way the Danish and Swedish governments frame and strategically communicate asylum and migration policies. Policy documents are a form of strategic communication, which can be described as purposeful communication activities that aim to advance a mission and achieve strategic goals (Hallahan et. al. 2007, p. 27). We engaged with

22

these texts to understand the explicit intentions and methods that the Danish and Swedish governments utilize to rationalize and legitimize their politics to the broader public.

We identified each framing location within each document to understand how the Danish and the Swedish governments communicate questions and concerns regarding asylum and migration. Moreover, we looked for the addressed problems and solutions. Entman (1993) explains that the way problems and solutions are framed plays an important role in the extension of political power (Entman 1993, p. 55). We provide an overview of the four framing locations in the Danish and Swedish policy documents that include recurring themes, characteristics and tendencies in each country. These findings are used in combination with the findings of the content analysis as a starting point for the qualitative framing analysis.

4.3.3 Qualitative framing analysis

The second part of our analysis is a holistic qualitative framing analysis based on the key findings in the first part, which aims to answer the third research question. Moreover, we aim to understand the differences and similarities in the framing of the refugee crisis by focusing on the Swedish implementation of border controls in November 2015, the removal of the external border controls in 2017, and Danish and Swedish migration policies. The framing analysis is structured according to Entman’s (1993) four framing functions: problems, causes, moral judgements and remedies. The concept of framing helps us uncover the details of how the different texts exert power (Entman 1993, p. 56).

4.4 Internal validity and ethical considerations

In all research projects, there are ethical considerations. As we mix quantitative and qualitative methods to approach our research questions, there are certain criteria for assuring quality in our research. Internal validity and objectivity were important considerations in the process of coding news articles and in the quantitative content analysis. To ensure internal validity and reliability when coding news articles, we picked a sample from the collected news articles and we both coded the same sample. Afterwards, we compared our selections in the coding scheme. The most challenging category was “moral value/judgement”, which assesses the general tone of the article. It was without doubt difficult to code. Although, we discussed and agreed on guidelines for each category, we experienced that the coding was highly subjective depending on our

23

personal views, predefined knowledge and culture. E.g. if an article represents newcomers as people who should be well received and welcomed, we marked the article as positive. If an article represents the arrival of newcomers as e.g. a threat towards society, creating a societal collapse or mainly places emphasis on limiting the entries of newcomers, we marked the article as negative. Moreover, we marked articles negative, if the included sources mainly expressed negative opinions about the arrival of people. If journalists and other sources represented the situation without expressing any particular positive or negative perspective, we marked the article as neutral. We are aware that this evaluation is influenced by our own political position and our individual perspectives on the topic. Hence, we are not able to provide a completely objective assessment as there is no such thing.

When doing qualitative research, it is important to establish trustworthiness by ensuring the credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability to ensure the quality of the research (Collins 2010, p. 168). Important reflections throughout this research project are how we select quotes and examples from the data to illustrate how the refugee crisis was framed in Danish and Swedish news media and policy documents. Our specific selection of quotes and examples influences how we as researchers frame media’s and governments’ framing of the situation. Our aim has been to select examples that illustrate different perspectives to provide a nuanced and balanced view on the news coverage and the policy documents for the chosen periods. Furthermore, the initial overview of general tendencies found in the content analysis guided our selection of main topics that we analyse in the qualitative analysis.

As researchers, we are aware of our responsibility in terms of how we engage with this specific moment in time and vulnerable groups of people. We have a responsibility of not reproducing existing frames and discourse when analysing how news media or governments frame the crisis or asylum seekers and refugees. In this study, we aim to understand how media and governments represent this period and these specific people. Therefore, we present how these institutions frame the topic. According to Barker (2008), when engaging in discourse research, there is an issue of trustworthiness in terms of how researchers read, interpret and represent texts. Thus, it is important that methods employed are explained to strengthen the reliability and validity of study results (Barker 2008, pp. 162-163). By thoroughly describing our methodological procedure, we explain our choices and the claims that we have established.

24

5. Understanding Danish and Swedish migration

policies

To understand how Danish and Swedish news media and governments represent the refugee crisis, it is relevant to look at the development of Danish and Swedish asylum and migration policies. In the following section, we briefly describe the migration policies in the two countries.

5.1 Swedish policies: From an exceptionalist model to a

civic turn

Several scholars have identified a shift in Swedish political rhetoric and policies about asylum, immigration and integration (see Shierup & Ålund 2011; Borevi 2014; Shierup et. al. 2014; Dahlgren 2016, p. 386; Bech et. al 2017). Most recent changes emerged in 2015, when the Swedish government implemented temporary border controls for all public transportation arriving in Sweden and temporarily aligned Swedish asylum policies with the minimum levels of EU laws. The purpose of these policy regulation was to lower the influx, thereby easing the burden on reception services and organizing the reception of newcomers by registering asylum seekers (Fratzke 2017, p. 1). These changes have been a turning point in Swedish politics and a step towards anti-immigration policies that Sweden have long been avoiding (Dahlgren 2016, pp. 385-386).

Some scholars have identified and reproduced a discourse about Sweden’s previous immigration policies as being fair and generous. Overall, they describe the Swedish welfare system as an exceptional model compared to other European immigration policies (Shierup & Ålund 2011; Shierup et. al. 2014; Borevi 2014; Dahlgren 2016, p. 386). The Swedish model of exceptionalism emphasizes the protection and equality of all Swedish citizens and new immigrants arriving in Sweden. Hence, everyone has access to fundamental rights – a persistent objective in the Swedish welfare society. Moreover, equal rights may be essential to enable newcomers to feel and consider themselves as equal and legitimate citizens (Borevi 2014, p. 717).

However, by looking at recent Swedish integration policies, scholars have found that the model of exceptionalism is challenged by a civic turn (Shierup & Ålund 2011; Borevi 2014; Bech et. al. 2017). The focus in the new policies has moved from the access to rights to an approach that

25

makes rights a reward that people will receive after fulfilling certain goals and obligations. Consequently, newcomers must earn their rights (Borevi 2014, p. 717). The notion of civic integration is a political tendency, which is also seen in Danish policies (Bech et. al. 2017). Shierup and Ålund (2011) argue that recent Swedish policies follow the trends of other EU member states, which breaks with Sweden’s former tradition of migration and citizenship policies (p. 47). Through an examination of the development of Swedish migration and integration policies since the 1970s, Shierup and Ålund (2011) explain how Swedish exceptionalism is being dissolved by the impact of the neoliberal ideology. According to Dahlgren (2016), the most recent shifts in Swedish asylum and migration policies have disturbed Swedish self-perception. This shift in policies demonstrates that the handling of new arrivals and the economic situation in Sweden is prioritized over moral values (Dahlgren 2016, p. 386). Bech et. al. (2017) argue that Swedish migration policies still reflect humanitarian principles and a fundamental belief that newcomers are able and willing to contribute to Swedish society. Although Swedish asylum, migration and integration policies are becoming stricter and increasingly influenced by the pressure of neoliberalism and policies in other EU member states (p. 20).

5.2 Danish policies: Civic selection and striving for

Danish cohesion

Danish policies are claimed to emphasize welfare over humanitarianism. Bech et. al. (2017, pp. 9-10) argue that Danish policies explicitly argue for and justify the goal of reducing the numbers of asylum seekers, making Denmark less attractive to newcomers and ultimately protecting the Danish welfare regime. In general, a radical contrast has been identified between the policies and the political debate about immigration in Denmark and Sweden (see Borevi 2014; Hellström & Hervik 2014; Bech et. al. 2017). The two countries represent two different approaches to immigration, the inclusion of newcomers, active citizenship and two different ideas of national identity (Borevi 2014, p. 712). According to Bech et. al. (2017), the civic integration in Denmark goes hand in hand with civic selection. In practice this means that only those people who fit the Danish egalitarian way of life and those who seem to have potential to be able to contribute to Danish society should be allowed in (Bech et. al. 2017, p. 20).

26

This is a tendency that Horsti (2008) identifies throughout Europe where different attempts at selective immigration regulation have been made to distinguish between the people who are expected to integrate into the host country and the people who are assumed not to integrate. She explains that in Denmark selective immigration includes measurements of newcomers’ ability to integrate, which for instance is done by testing people's knowledge about the Danish language and culture. She claims that such tools and developments reflect “the worries and fears that are present in contemporary European societies” (Horsti 2008, p. 43). Critical studies of Danish immigration policies have several times described the Danish approach as promoting assimilation and being anti-multicultural (Jensen 2010, p. 187; Holtug 2013 pp. 207-208; Laegaard 2013; Borevi 2014, p. 712). According to Borevi (2014), newcomers to be included in the Danish welfare system are required to adjust to Danish values and traditions. By contrast, the Swedish welfare model attempts to include more cultural diversity (Borevi 2014, p. 712). Overall, some scholars argue that Denmark is among the European countries that have implemented most civic integration policies and adopted some of the most strict, complex and demanding migration policies (Borevi 2014, p. 716; Bech et. al. 2017, p. 6).

6. Analysis

In this chapter, we conduct a two-part analysis. In the first part, we make a quantitative content analysis of the news articles (6.1). Subsequently, we conduct a framing analysis of the policy documents (6.2), in which we identify the four framing locations: communicator, text, receiver and culture (Entman 1993). In the second part of the analysis, we merge the key findings from the first part into a qualitative analysis (6.3). This part of the analysis is structured according to the four framing functions: defined problems, defined causes, moral judgement and suggested solutions (Entman 1993). Lastly, we summarize the findings of the analyses (6.4).

27

Part 1

6.1 Content analysis of news articles

The total sample includes 259 articles5. In the first period in 2015, there was a total of 204 articles,

111 (54%) from the Swedish newspapers and 93 (46%) articles from the Danish newspapers. In the second period, we collected a total of 55 articles, 35 (64%) Danish articles and 20 (36%) Swedish articles. There were significantly more articles concerning asylum and migration in the first period in November 2015 compared to the second period in May 2017. Although migration and asylum policies continued to be high on the news agenda in 2017, the frequency of the words borders, and refugees or asylum seekers appeared significantly fewer times in the search in May 2017. Figure 2 below shows the distribution among the eight different newspapers in the first and second periods. The most common type of articles in both periods in the Danish and Swedish newspaper articles are traditional news articles or reportages, which represent 59% of the Danish articles and 70% of the Swedish articles in the first period, and 60% of the Swedish sample and 49% of the Danish sample in the second period.

Figure 2: Distribution of articles in newspapers in the first and second periods.

28

6.1.1 Front-page stories

In the sample of Swedish articles in the first period, the implementation of border controls reached the front-page six times, of which two times on the day of the implementation in Aftonbladet and Dagens Nyheter. Both headlines stated that Sweden implemented temporary border controls and that it could lead to more asylum seekers (Aftonbladet 2015, p. 1; Olsson 2015a, p.1). Aftonbladet featured a photo of the Öresund bridge (Aftonbladet 2015, p. 1), while Dagens Nyheter showed a photo of Malmö Central Station with an incoming train, police and passengers (Olsson 2015a, p. 1). Furthermore, the story hit the front-page three times on November 13, 2015, in Dagens Nyheter, Svenska Dagbladet and Sydsvenskan. The front-page of Sydsvenskan stated that “Strong reinforcement is on its way” (Sydsvenskan 2015, p. 1), while Svenska Dagbladet’s front-page story stated, “Quiet start for controls” (Svenska Dagbladet 1 2015, p. 1). Two days after the implementation of temporary border controls, Svenska Dagbladet ran another front-page story about the consequences of the temporary border control for the affected refugees and asylum seekers under the headline “Hostages of the border control” (Svenska Dagbladet 2 2015, p. 1).

In the Danish news articles, the Swedish implementation of border controls reached the front-page four times of which three times in Politiken and once in Berlingske. Three of the front-front-page stories in the Danish sample concerned the Swedish implementation of temporary border controls. For example, Politiken ran a front-page story on the day of the implementation with the following headline “Pressure for Danish border control” (Klarskov & Thobo-Carlsen 2015, p. 1). In this story, multiple Danish politicians stated that the Danish government should also implement border controls. For instance, the spokesperson from the Conservative People’s Party claimed that “When Sweden closes for ten days, it leaves a big flow of migrants in Denmark. Denmark is in no way geared for this. It is a little strange being taken over by our sister country, which we normally perceive as a bit feeble. This calls for an extraordinary reaction” (Klarskov & Thobo-Carlsen 2015, p. 1). Only the leader of the party the Alternative was critical towards Danish border controls, claiming that “It is understandable that Sweden does what it does. But at the same time, it is a sad result of the lacking European leadership that countries are trying to solve this crisis on their own instead of solving this together” (Klarskov & Thobo-Carlsen 2015, p. 1). Another front-page story in Politiken on November 14, 2015 under the headline “Swedish reprimand to Denmark” described the relationship between Denmark