Do I Care Enough

to Engage?

MASTER OF SCIENCE: Business Administration THESIS WITHIN: International Marketing NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15 ECTS

AUTHORS: Huib de Bruijn and Quincy Verheul DATE AND PLACE: May 2020, Jönköping

An Investigation on Contributor Engagement Towards the

Dutch Cancer Society

2

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Do I Care Enough to Engage?Authors: H.E.R. de Bruijn and Q.L.M.B. Verheul Tutor: Adele Berndt

Date: 18/05/2020

Key Terms: Charitable Contribution – Charitable Organisation – Charity Sector – Contributor – Contributor Engagement – Dutch Cancer Society – Consumer Engagement

Project Initiation

This research paper has been conducted for Jönköping International Business School to demonstrate the authors’ competences acquired during the curriculum of the Master of Science in International Marketing.

Abstract

Background: The environment of the charity sector is changing. The overall sector of licensed charities in the Netherlands grew over the past couple of years, but this trend is not caused by a growth in contributors, as the numbers show a downwards slope. Besides that, research shows that the individual’s willingness to contribute to charity declines. Next to that, it is visible that the needs and wishes of contributors to charity change. This could possibly imply that individuals are willing to engage with charity, but in a different manner.

Purpose: The way contributors contribute to charitable organisations is evident, but how and why individuals engage is a relatively unexplored area, as previous research mainly focused on the motivations rather than the dimensions of engagement. Therefore, the research purpose of this paper is to investigate the dimensions of engagement of Dutch individuals towards DCS, whilst it adds to the existing body of literature about contributor engagement in the charity sector.

Method: The study revolved around a positivistic research philosophy, following a sequential mixed-method research design to gather the information and insights needed. A questionnaire was used to obtain the inputs of 333 unique respondents, which was followed up by 10 semi-structured in-depth interviews to enrich the findings. To analyse the data, various techniques, such as factor analysis, correlation and multiple regression, were executed to reveal statistically significant relationships and influences among the variables.

3

Conclusion: The results show that the five dimensions of volunteer engagement, namely behavioural, emotional, cognitive, spiritual and social, are also applicable when investigating contributor engagement. However, the study has shown that all dimensions apart from the spiritual one have a statistically significant influence on the contributor engagement of Dutch individuals towards DCS. Further findings and a more profound understanding of the motives of interviewees revealed that the deeper motivations to engage or not engage with DCS are in line with national trends visible within the charity sector. The outcomes could contribute to DCS’ and possibly other charitable organisations’ understanding of the altering needs and wishes of contributors and the Dutch society. More specifically, the findings can contribute to the existing knowledge of the dimensions of engagement and could be utilised for marketing purposes to focus on the right areas when developing future strategies.

4

Acknowledgements

The authors of this paper would like to make use of the opportunity to express their utmost gratitude to all the parties that guide and helped us throughout the process of writing this research paper. Their patience, help and support are much appreciated.

First of all, the authors would like to thank their tutor, Adele Berndt, for her guidance and constructive feedback during the topic selection, the wrap-up of the paper and all the stages in between. In addition, the authors appreciate the useful feedback received from their peers, Floris Korzilius and Jonas Weiss, during the thesis seminars.

Next, the authors would like to thank all the teachers, guest lecturers, peers, families, friends and acquaintances for their share in this study.

Last but not least, a huge thanks to the respondents of the online questionnaire and the participants of the in-depth telephone interviews. This paper would not have been possible without you.

Thank you to every single one of you for your help, support, guidance and advice.

5

Table of Contents

1. Introduction 10

1.1 Background 10

1.1.1 Sector Overview 10

1.1.2 The Changing Environment 11

1.1.3 The Gap 12

1.2 Problem Statement 12

1.3 Research Purpose 13

1.4 Central Research Question 13

1.5 Study Delimitations 13 1.6 Contribution 14 1.7 Key Terms 14 1.7.1 Charitable Contribution 14 1.7.2 Charitable Organisation 14 1.7.3 Charity Sector 14 1.7.4 Consumer Engagement 15 1.7.5 Contributor 15 1.7.6 Contributor Engagement 15

1.7.7 Dutch Cancer Society 15

1.8 Structure 16 2. Literature Review 17 2.1 Overview 17 2.2 Charity 17 2.2.1 History of Charities 17 2.2.2 Societal Responsibility 18 2.3 Charitable Contributions 20 2.4 Engagement 21

2.4.1 Why People Engage 21

2.4.2 The Domain of Engagement 22

2.4.3 Consumer Engagement 23

2.5 Contributor Engagement 24

2.5.1 Volunteer Engagement Model 25

2.5.1.1 Behavioural 25

2.5.1.2 Emotional 25

2.5.1.3 Cognitive 26

2.5.1.4 Spiritual 26

6 2.6 Conceptual Framework 28 2.7 Hypotheses 29 3. Research Methodology 30 3.1 Introduction 30 3.2 Research Philosophy 31 3.3 Research Approach 31 3.4 Research Design 31 3.5 Research Strategy 31

3.6 Research Sampling Strategy 32

3.7 Data Collection 32 3.7.1 Primary Research 32 3.7.2 Secondary Research 33 3.8 Questionnaire Design 33 3.8.1 Constructs 33 3.8.2 Scales 34 3.8.3 Pilot Test 35 3.9 Participant Profiles 35 3.10 Data Analysis 36 3.10.1 Viability 36 3.10.2 Reliability 36 3.10.3 Validity 37 3.11 Data Interpretation 37 3.11.1 Descriptive Statistics 37 3.11.2 Frequency Tabulation 37 3.11.3 Cross-Tabulation 37 3.11.4 Factor Analysis 37 3.11.5 Correlation 38 3.11.6 Multiple Regression 38 3.12 Time Horizon 38 3.13 Data Cleaning 38 3.14 Data Ethics 38 4. Research Findings 40

4.1 Quantitative Research Findings 40

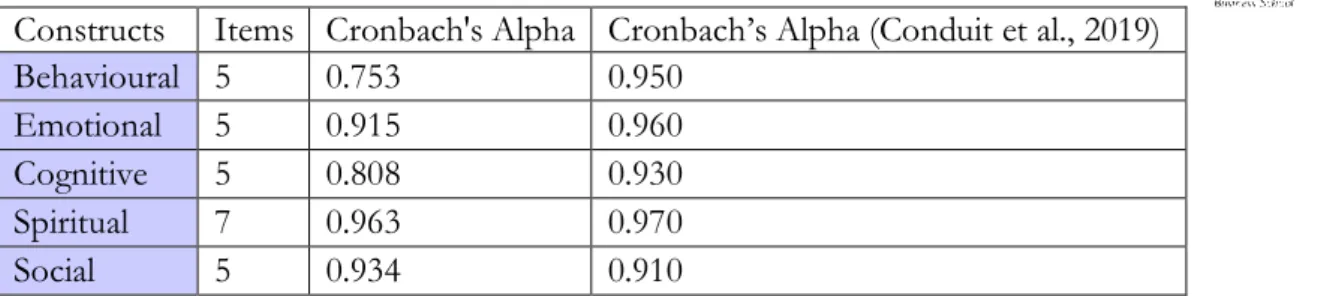

4.1.1 Scale Reliability 40

4.1.2 Descriptive Statistics 41

4.1.3 Ways of Engagement 43

7 4.1.5 Dimensions of Engagement 45 4.1.5.1 Behaviour 45 4.1.5.2 Emotional 46 4.1.5.3 Cognitive 46 4.1.5.4 Spiritual 47 4.1.5.5 Social 47

4.1.5.6 Summary of the Engagement Dimensions 48

4.1.6 Correlation 48 4.1.7 Multiple Regression 50 4.1.7.1 Outcomes 52 4.1.8 Hypotheses 52 4.1.8.1 Hypothesis 1 52 4.1.8.2 Hypothesis 2 52 4.1.8.3 Hypothesis 3 53 4.1.8.4 Hypothesis 4 53 4.1.8.5 Hypothesis 5 54 4.1.8.6 Hypothesis 6 54 4.1.8.7 Hypothesis 7 54

4.2 Qualitative Research Findings 56

5. Discussion 58 6. Conclusion 61 6.1 Research Question 61 6.2 Contribution 61 6.3 Implications 62 6.4 Limitations 62 6.5 Future Research 63 7. References 64 8. Appendices 83

Appendix 1 - Gantt Chart 83

Appendix 2 - Questionnaire Design 84

8

Table of Figures

Figure 1 – Structure 16

Figure 2 – Overview 17

Figure 3 – Conceptual Framework 28

Figure 4 – Research Onion 30

Figure 5 – Likert Scale 35

Figure 6 – Multiple Regression Visualisation 51

Table of Tables

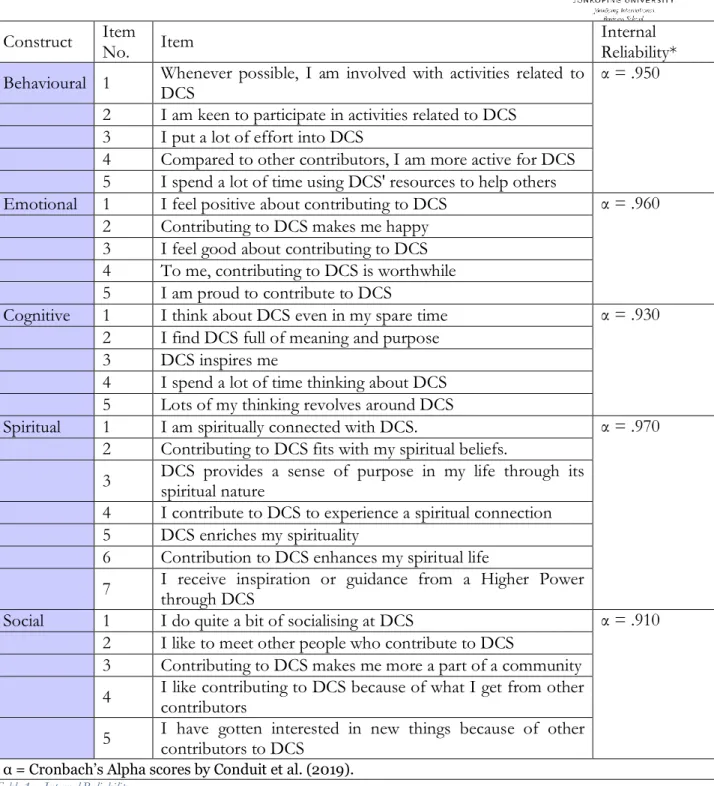

Table 1 – Internal Reliability 34

Table 2 – Participant Profiles 36

Table 3 – Scale Reliability 41

Table 4 – Gender Distribution Sample 41

Table 5 – Province Distribution Sample 42

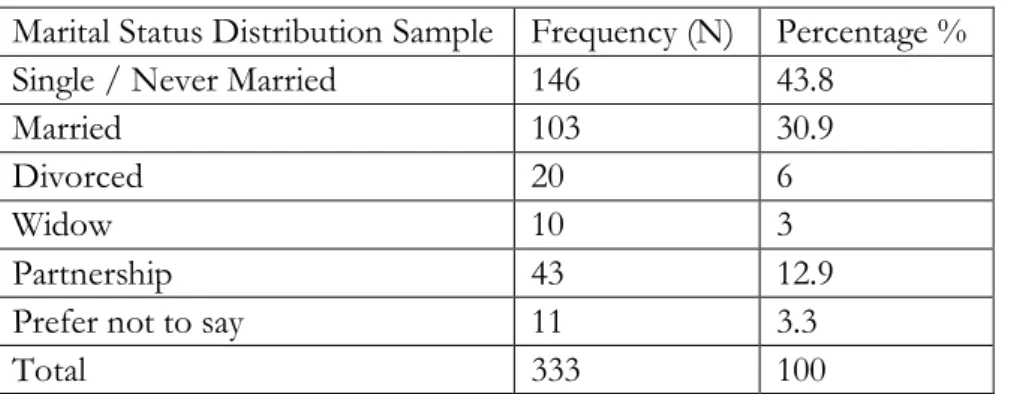

Table 6 – Marital Distribution Sample 42

Table 7 – Religious Distribution Sample 42

Table 8 – Religion Distribution Sample 42

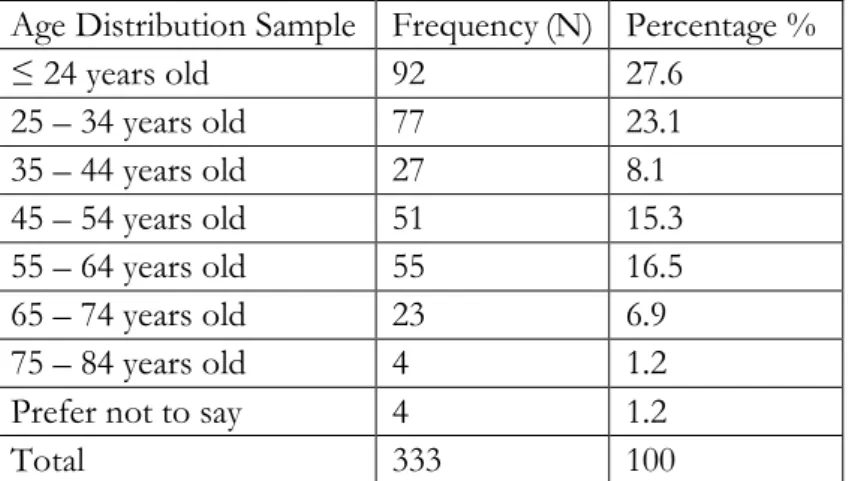

Table 9 – Age Distribution Sample 43

Table 10 – Labour Status Distribution Sample 43

Table 11 – Ways of Engagement 44

Table 12 – Rotated Component Matrix 45

Table 13 – Behavioural Dimension 46

Table 14 – Emotional Dimension 46

Table 15 – Cognitive Dimension 47

Table 16 – Spiritual Dimension 47

Table 17 – Social Dimension 48

Table 18 – Summary of the Dimensions 48

Table 19 – Pearson Correlation Levels 49

Table 20 – Overview of Correlations 50

Table 21 – Multiple Regression Scores 51

Table 22 – Statistical Evidence H1 52

Table 23 – Statistical Evidence H2 53

Table 24 – Statistical Evidence H3 53

Table 25 – Statistical Evidence H4 53

Table 26 – Statistical Evidence H5 54

Table 27 – Statistical Evidence H6 54

9

Table of Appendices

Appendix 1 – Gantt Chart 83

Appendix 2 – Questionnaire Design 104

10

1. Introduction

______________________________________________________________________________

This chapter aims to provide the introduction and a relevant background on the topic. After that, the problem statement, the research purpose and the research question are stated in order to demonstrate the direction of the research paper. Last but not least, the study delimitations, contribution and key terms are described to offer the reader a clear and concise overview of the overall study.

______________________________________________________________________________ 1.1 Background

Supporting a cause or organisation that has a significant personal meaning or for a specific reason is a form of charitable contribution (Sargeant, 1999). Where the total number of charities has been growing rapidly since 1960 (Turner, 2010), the concept of helping others in society by means of giving finds foundation in ancient history. The earliest forms derive from the Greek, where ‘philantropia’ meant love of mankind (National Philanthropic Trust, 2016b). This evolved towards nowadays’ conception of philanthropy; “the use of private resources for public purposes” (Jung, Phillips, & Harrow, 2016, p. 4). Philanthropy therefore forms a solid base for charitable contribution. However, charitable contribution mainly relies on people that engage based on a reason or meaning that impacted their life (Sargeant, 1999), and several different streams and purposes can be found within the charity sector. The total sector can be divided into eight different branches, to be found in International Help & Human Rights, Animals, Health, Welfare, Religion & Worldview, Art & Culture, Nature & Environment and Education (Brancheorganisatie Goede Doelen Nederland, 2019).

1.1.1 Sector Overview

With a net value of €3.1 billion, the charity sector is steadily growing in the Netherlands (Brancheorganisatie Goede Doelen Nederland, 2019). In line with global trends, the industry grew from 396 licensed charities in 2015 to a current total of 609 in 2020 (Centraal Bureau Fondsenwerving, 2020). However, this growth is not funded by an equal growth in contributors to charitable organisations in general. This decrease is mainly caused by a drop in the number of contributors, as well as the declining willingness of people to contribute, indicating individuals are engaging less with charitable organisations (European Fundraising Association, 2017). Therefore, charities have to adapt their approach to remain relevant in order to attract new contributors, but also to ensure that current contributors remain engaged. An example of alternative approaches are people that contribute by devoting time to clean up oceans and beaches for a certain period of time. World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) has reacted to this willingness by hosting events and providing platforms where people committed to the cause can apply and help, with no strings attached (WWF, n.d.). Where the WWF

11

example focuses on changing the actions, charities seem to try to play into technological innovations too, mainly because technological solutions make the donation of money easier and more convenient (KWF Kankerbestrijding, n.d.b).

Within the Dutch charity sector, KWF Kankerbestrijding (Koningin Wilhelmina Fonds voor de Nederlandse Kankerbestrijding, hereafter referred to as DCS (Dutch Cancer Society)), is the largest charity when looking at net income and number of contributors (Centraal Bureau Fondsenwerving, 2020). Within the eight branches, DCS operates within the health branch. DCS was founded in 1949 and over the years, big accomplishments have been achieved regarding the prevention, research and treatment of cancer. In order for DCS to continue making an impact, the focus relies on three main pillars: investigating into scientific research for cancer, education about cancer and patient (after)care and support (KWF Kankerbestrijding, n.d.a). Based on these pillars, the most occuring form of engagement to DCS is in the form of monetary donations. Over the fiscal year of 2018, DCS received a total of €144.2 million in donations, of which €137.1 million could be directly dedicated towards these main three pillars (van den Gronden & Falkenburg, 2019).

1.1.2 The Changing Environment

Although DCS remains the biggest charity within the Netherlands in 2020, the decreasing number of contributors is a trend that tends to have a greater impact on national charities (Brancheorganisatie Goede Doelen Nederland, 2019). Where many charities suffered, it is the younger generation that is not in favour of being attached towards contracts and deals for fixed periods of time (Charities Aid Foundation, 2019). Long-term obligations require some form of financial stability and perhaps younger people have fewer possessions to contribute, as well as a decreasing disposable income (YouGov, 2019). Another reason for contributing is due to the religious orientation of contributors and this was reflected in a study by Bekkers, de Wit & Felix (2017), which showed that the Dutch contribute at least partly because of religion. However, in recent times, the size of the religious population has declined (Hemming & Madge, 2017), which also potentially impacts the contributions to charities in the Netherlands and therefore the level of engagement towards charitable organisations.

The overall numbers of contributors declined by 1% for large Dutch charities, such as DCS, WNF and UNICEF, amongst others. However, the overall income of all charities grew with approximately 2% to a total of €3,1 billion in 2018 (Brancheorganisatie Goede Doelen Nederland, 2019). With this amount of money involved, it is highly desired by individuals to have a certain assurance that their resources will be used appropriately when engaging with a charitable organisation (Tremblay-Boire &

12

Prakash, 2016). This level of trust and confidence is measured as donor confidence, which is strongly correlated with perceived overall confidence in charitable organisations, as well as consumer confidence in general (Alhidari, Veludo-de-Oliveira, Yousafzai, & Yani-de-Sorianoet, 2018). Therefore, donor confidence is of influence when looking at individual’s engagement with charity. A report by The Dutch Donor Panel (Het Nederlandse Donateurspanel, 2019) shows a decreasing trend in overall donor confidence, where the consumer confidence slightly increased. This diverging trend showcases that the overall confidence in charitable organisations is decreasing. An updated report shows that the confidence in large national charities significantly decreased from 33% in 2016 to 25% in 2019 (Het Nederlandse Donateurspanel, 2020). This decreased confidence in charities is visible in figures of the Dutch society showing responsibilities for national concerns and issues. Approximately 17% of the Dutch society thinks charities are responsible for taking care of incurable diseases as a societal issue (Het Nederlandse Donateurspanel, 2019). Compared to 47% of the population that believes that the government should take responsibility for the same sector, the decreasing confidence and different views on responsibility impact the engagement to charity.

1.1.3 The Gap

Although there are several perspectives to explain the shift in contributions and thus the engagement, it is important for charitable organisations to remain relevant for their contributors. Especially because of the broad intrinsic pallet of dimensions of which consumer engagement, hence contributor engagement, consists of (Dessart, Veloutsou & Morgan-Thomas, 2015). Therefore, the focus relies on finding out what drives Dutch individuals to engage with DCS in a way of donating money, devoting time and the (co-)creation and sharing of information. Goede Doelen Nederland, the union for charitable organisations in the Netherlands, tries to connect with contributors to find out their needs and wants. Professor of philanthropy René Bekkers expresses the urgency for explaining the existing gap between how the organisations recruit and engage new contributors and what their needs and wishes are (van Sadelhoff, 2019), in order for charities to remain relevant and keep individuals engaged. To explore this, the Volunteer Engagement Model (Conduit, Karpen, & Tierney, 2019) will be utilised to investigate the dimensions that motivate Dutch individuals to engage with DCS.

1.2 Problem Statement

As discussed before, the overall sector of licensed charities in the Netherlands grew over the past couple of years. This trend is not caused by a growth in contributors, as the numbers show a downwards slope. Besides that, the individual’s willingness to contribute to charity declines. Whilst the trends within the sector tend to indicate a downwards tendency, it is even more remarkable that the

13

total monetary amount of donations keeps on growing, meaning that the people that do donate, donate more. Next to that, it is visible that the needs and wishes of contributors to charity change. This could possibly imply that individuals are willing to engage with charity, but in a different manner. Therefore, it is eminent that the domain of engagement of individuals to charitable organisations is altering. Thus, this paper serves to identify, examine and evaluate the dimensions that influence Dutch individuals whether or not to engage with DCS.

1.3 Research Purpose

The way contributors contribute to charitable organisations is evident, but how and why individuals engage is a relatively unexplored area, as previous research mainly focused on the motivations rather than the dimensions of engagement, such as Beaumont & Baker (2011) and Duncan & Oliver (2017), amongst others. Therefore, the research purpose of this paper is to investigate the dimensions of engagement of Dutch individuals towards DCS. The importance for charitable organisations relies in obtaining information regarding the engagement contributors show towards charities.

1.4 Central Research Question

To investigate how and why Dutch individuals engage with charity, it is imperative to be able to answer the central research question that guides the study on this topic.

RQ - What is the influence of the dimensions of engagement on Dutch individuals towards DCS? 1.5 Study Delimitations

The scope of this research study solely lays on DCS, due to the fact that it is the largest organisation within the Dutch charity sector, considering net income and number of contributors (Centraal Bureau Fondsenwerving, 2020). It allows the research to be more in-depth on one specific charitable organisation rather than an entire sector, which tends to make the results more trustworthy. This, however, does not necessarily entail that the outcomes of this research are also applicable in different branches within the charity sector. Besides, since the research focuses on Dutch individuals engaging with DCS, all other nationalities are excluded. For that reason, the used framework by Conduit et al. (2019) has been translated from English to Dutch to avoid language barriers and enhance the trustworthiness of the outcomes. Lastly, the research focuses on three forms of contribution that lead to engagement, namely donation of money, devotion of time and (co-)creation of content. Other forms and motives, such as goods, services and expertise, are excluded from this paper because of the irrelevance for the charity sector.

14 1.6 Contribution

The aim of this research paper is to add to existing literature about contributor engagement in the charity sector. Additionally, it attempts to elaborate on the dimensions of volunteer engagement and how this affects the behaviour of Dutch individuals towards DCS. The insights of this study do not only advance the theoretical understanding of the engagement phenomenon in this context, but may also provide grounds for managerial implications of organisations within the charity sector.

1.7 Key Terms

For this research paper, it is crucial that several key terms are distinguished and elaborated on from the very start, since it is essential that these components are used in the appropriate context. The key terms are presented in alphabetical order.

1.7.1 Charitable Contribution

Charities receive help and support in many different forms. To narrow down the scope and to delimit the research, this study refers to the term ‘charitable contribution’ as the donation of monetary resources, the provision and devotion of time and the sharing and (co-)creation of content related to DCS. A deliberate decision has been made to exclude the donation of goods by individuals, where this is less relevant within the health sector of charity.

1.7.2 Charitable Organisation

This paper will refer to DCS as a ‘charitable organisation’ or a ‘charity’. Looking at the field of charitable organisations, DCS is considered to be the biggest organisation within the health branch, which makes it a profound reason to establish the research around that organisation. A charity, or charitable organisation, is characterised as a non-profit organisation that mainly focuses on philanthropy and social well-being or uncovered societal concerns (Reiling, 1958).

1.7.3 Charity Sector

For this study, ‘charity sector’ is specified as the entire environment of charities. The total sector can be divided into eight different branches, to be found in International Help & Human Rights, Animals, Health, Welfare, Religion & Worldview, Art & Culture, Nature & Environment and Education (Brancheorganisatie Goede Doelen Nederland, 2019). Since DCS is active within the health branche, this paper only investigates that specific area of interest.

15

1.7.4 Consumer Engagement

Consumer engagement is defined in various ways and contexts. For the research at hand, it is referred to as the level of an individual’s motivational, brand-related and context-dependent state of mind characterised by specific levels of cognitive, emotional and behavioural activity in direct brand interactions (Hollebeek, 2011). It implies the level of a customer's physical, cognitive and emotional presence in their relationship with a product or service organisation (Patterson, Yu, & de Ruyter, 2015).

1.7.5 Contributor

The study continues to use ‘contributors’ as the specific term for the population sample of the research, since it entails the individuals of the Dutch society that contribute their money, time, services, goods, expertise, knowledge, effort and exposure to a charitable organisation. Due to time constraints, however, the focus will rely on money, time and (co-)creation. Overall, it is believed to be the right term that fits the general direction of the research study.

1.7.6 Contributor Engagement

Within this research, the scope relies on contributor engagement, which is a subdomain within overall consumer engagement. In this study, contributor engagement is assumed to be similar to volunteer engagement, which is defined as a multi-dimensional approach consisting of behavioural, emotional, cognitive, spiritual and social components that lead to engagement (Conduit et al., 2019).

1.7.7 Dutch Cancer Society

KWF Kankerbestrijding (Koningin Wilhelmina Fonds voor de Nederlandse Kankerbestrijding, in this study referred to as DCS (Dutch Cancer Society)), is the largest charity when looking at net income and number of members (Centraal Bureau Fondsenwerving, 2020). DCS is founded in 1949 and over the years, big accomplishments have been achieved regarding the prevention, research and treatment of cancer.

16 1.8 Structure

17

2. Literature Review

______________________________________________________________________________

The purpose of this chapter is to provide the theoretical background relevant for this topic in order to provide a solid framework for the research study to be based on.

______________________________________________________________________________ 2.1 Overview

Figure 2 – Overview

2.2 Charity

“Wealth is not new. Neither is charity. But the idea of using private wealth imaginatively, constructively, and systematically to attack the fundamental problems of mankind is new” - John Gardner (Janus, 2017). When reviewing charity, it is eminent to focus on determining the domain of the terminology. A charity, or charitable organisation, is characterised as a non-profit organisation that mainly focuses on philanthropy and social well-being or uncovered societal concerns (Reiling, 1958). Nonetheless, the term charity also covers the practical concept of voluntarily helping others by giving and sharing (Bekkers & Wiepking, 2010), as well as the religious framework of unconditional love and benevolence (Crumley, 2017). Within this extensive domain, the focus relies on charitable organisations, motivation for charitable contribution and the dimensions that make people decide to engage with charity.

2.2.1 History of Charities

In order to understand engagement towards charitable organisations, it is important to understand how charities became as deeply established within society (Abramson, 2018). The shift of living in rural areas to moving and centralizing into cities from the 15th century caused social orders among mankind because of the rapid but unprecedented growth of the exchange of people, goods, ideas and cultural values. This growth had a significant effect on philanthropy and made citizens start to notice the ones in need. This resulted in that giving from a religious or political perspective changed into giving as a philanthropic act (National Philanthropic Trust, 2016c). Due to these increasing philanthropic acts or charitable initiatives, the English Parliament enacted the Charitable Uses Act in 1601. This Act provided a written register containing charitable purposes and its qualifications (Jones, 1969). As being

18

the first written documentation of charitability within society, the question on how the quality of human life in urban areas could be improved arose. Where chaotic times of war, revolution and industrialisation caused challenges of urban growth with refugees, widows, orphans and atrocious sanitation and working conditions in factories, the need for action grew (National Philanthropic Trust, 2016b). The answer was found in private efforts and growing responsibility for the underprivileged, causing emerging philanthropy (National Philanthropic Trust, 2016c). However, the first legally operating and noted charity that operated independently from religion founded in 1741 by Thomas Coram (Banerjee & Foundling Museum Brunswick Square, 2016). This first registered charity founded in the form of an orphanage served as the precedent for organized charitable associations in general (Wagner, 2004). From then, charities emerged and started to develop and perform away from civil and human rights into science, health and technology, political and social reform and many other causes (Abramson, 2018). Where the operational activities and subject areas grew, the number of charities increased yearly, but the organisations also became more structured, organised and coordinated in order to fully exploit resources and increase reliability (Smith, 2002).

2.2.2 Societal Responsibility

Years after, the principle of philanthropic traditions within society in order to address societal issues or concerns remains relevant. However, philanthropy in the form of charitable organisations is more “organized, professional, and global than ever before” (National Philanthropic Trust, 2016a, 1980 ‒ present: Global Outlook of Giving, para. 1). Where the number of charities has been growing in every sector since its origin in 1741, the main question asked is why the addressing of these societal issues rely on private organisations. As mentioned earlier in this research, the overall confidence in the large national charities decreased from 33% in 2016 to 25% in 2019 (Het Nederlandse Donateurspanel, 2020). Nonetheless, 17% of the Dutch society believes that responsibilities around taking care of incurable diseases is for private organisations, where almost half the population (47%) thinks it is a governmental concern (Het Nederlandse Donateurspanel, 2019). However, societies remain built up in a way where governments handle crisis situations when it comes to emergency help or natural disasters, but other societal impact causes remain the responsibility of private help (Blanchette, 2007).

This same trend is visible within a corporate organisational environment when looking at sustainable and societal impact (Lougee & Wallace, 2008; Sahlin-Andersson, 2006). Within all levels of businesses and organisations, corporate social responsibility and the company’s ecological footprint grows and individual impact is made on the environment, as well as on society (Ji & Miao, 2020; Wang, Tong, Takeuchi, & George, 2016). This shows that it is imperative that, instead of leaving the issues and

19

challenges unaddressed, individuals as well as organisations take responsibility when the government does not. In this context, the philanthropic philosophy of “the use of private resources for public purposes” (Jung, Phillips, & Harrow, 2016, p. 4) is woven through all levels of society.

The question remains that when the majority of society feels that responsibilities of addressing societal issues are placed wrongly, how it is possible that no structural changes are made to this construction. Answers tend to be found in how the help is provided. “The primary reason private charity is more effective and more humane in providing aid lies in how aid is given, not simply how much is given” (Blanchette, 2007, p. 18). Another factor relies on the fact that the overall confidence in charitable organisations is decreasing. An updated report shows that the confidence in large national charities significantly decreased from 33% in 2016 to 25% in 2019 (Het Nederlandse Donateurspanel, 2020). This decreasing confidence is partly explained by individual issues regarding the transparency in operational governance of charitable organisations (Hyndman & McConville, 2016). A Dutch organisation investigating transparency levels of certified charitable organisations found that the transparency level of DCS is only 40% (Geef.nl, 2020). Even though DCS is a certified, transparent charity and several millions of euros have been spent towards the improvement of the overall transparency over the past years (KWF Kankerbestrijding, n.d.b), it is not sufficient to increase individuals’ confidence and trust.

Despite the fact that individuals feel that charitable organisations are not transparent enough, the majority of society feels that private governance and the freedom in the destination and provision of the aid is the main influential factor for the contributions to private charity (Khovrenkov, 2017). That makes it even more contradicting that 47% of the Dutch population strongly believes that the government should be responsible for the care of incurable diseases as a societal concern (Het Nederlandse Donateurspanel, 2019). Besides that, it is stated that governmental influence in for example tax reforms, government funding and even growing confidence in the government negatively affects charitable giving (Brooks, 2004). Thus, along with organisational contributions to charitable organisations and causes as a form of social responsibility, governments fund private charity in order to support the societal issues addressed (Andreoni & Payne, 2003). However, this does not eliminate the fact that confidence and trust in larger charities decreases. Therefore, it is imperative that society believes in the philanthropic philosophy of helping others considering the continuously growing amount of charities. This results in the belief of finding contributing to charity is worth the effort, time and/or money. In order to investigate the engagement that leads to a charitable contribution, it is crucial to understand the concept of charitable contribution.

20 2.3 Charitable Contributions

Giving is what makes humans different (Muth, Lindenmayer, & Kluge, 2014). Through good and bad economic times, charitable gifts have continued to roll in largely unabated over the past half century. As mentioned before, charitable contributions finds its foundation in the ancient Greek times. However, the environment of charitable contribution has changed over time, adapting to societal changes (Unerman & O’Dwyer, 2010). Already in 1999, the trend of a declining number of individuals supporting charities came to light, whilst the growing number of registered charities appeared (Sargeant, 1999). This caused an ever-ongoing trend of requiring charitable organisations to adapt to a changing society and refining both the quality and the targeting of their contributors (Hassan, Masron, Mohamed, & Thurasamy, 2018). Therefore, the environment of charitable contribution and how the concept is delimited is important to understand.

According to Glazer and Konrad (1996), only rich people contribute used to contribute to public good in order to demonstrate wealth. However, it is found that spending a share of one’s income towards others has a positive impact on happiness and even increases the emotional feeling (Dunn, Aknin, & Norton, 2008). Despite this positive emotional result of making a monetary donation to help others, in the Netherlands only approximately 0,7% of the overall Gross Domestic Product is devoted to charity (Bekkers, Schuyt, & Gouwenberg, 2015). Nevertheless, the concept of a charitable contribution contains of a wider scope than solely monetary contributions. “The donation of money to an organisation that benefits others beyond one’s own family” (Bekkers & Wiepking, 2011, p. 925) is defined as charitable giving and is therefore a concept within charitable contribution. However, contradicting arguments are found in the fact that charitable giving includes forms of helping behaviour, ranging from helping others in daily tasks to the donation of organs (Schwartz & Howard, 1980).

Nowadays, the concept of charitable contribution primarily revolves around two major pillars: the monetary donation to a charitable organisation and the devotion of time to or for a charitable organisation (Bekkers & Wiepking, 2011). However, due to emerging technological advancements, the sharing of information becomes more and more convenient and the sharing of knowledge and information can be considered an important intangible asset for organisations (Omar, Dahalan, & Yusoff, 2016). Therefore, the creation of awareness and the sharing of information regarding an organisation, its actions and purposes becomes more and more valuable (Lim, Lu, Chen, & Kan, 2015). Despite the little theoretical background available arguing the addition of the sharing and co-creation

21

of information and content to the terminology of charitable contribution, it is clear that the co-creation of information and content leads to increased knowledge and awareness, which, presumably, leads to higher contributions as a matter of time or money (Grace & Griffin, 2006). Examples can be found in viral social media campaigns, such as the 2014 ‘ALS Ice Bucket Challenge’ that lead to a quadrupling in the amount of monetary donations (Wallace, Buil, & de Chernatony, 2017).

However, the (co-)creation and sharing of content regarding charity goes beyond social media. Word-of-mouth and information regarding other people’s behaviour is considered social information and is a proven to be an influencer, which makes it an often used method on increasing charitable contribution (van Teunenbroek, Bekkers & Beersma, 2019). Where this social information is most commonly used by practitioners to increase contributions, it is meaningful to take into consideration the recommendations and information provided by friends, relatives and acquaintances. Research conducted in the travel industry shows that there is a significant positive influence on behavioural decisions when recommended by this group (Murphy, Mascardo & Benckendorff, 2007; Yeoh, Othman & Ahmad, 2013). This provides additional theoretical foundation for adding (co-)creation of content as a form of engagement to charitable organisations in this research.

2.4 Engagement

Narrowing down the scope and extent of the research and limiting the smaller and less specific forms of engagement, several other forms of charitable contribution, such as goods, services and expertise, are excluded. However, it is eminent that despite the chosen form of charitable contribution, individuals feel the need, want, desire or urge to contribute to and therefore engage with a certain cause (Sargeant, 1999). This is regardless the earlier described trends focusing on the changing environment of charitable organisations, where the most important factor for the changing environment is the changing society (Atkinson, Backus, Micklewright, Pharoah, & Schnepf, 2011).

2.4.1 Why People Engage

Bekkers and Wiepking (2011) argue that the intrinsic motivation for individuals to contribute to charity comes down to an individual’s needs, psychological costs and benefits, values and efficacy. These basically form the determinants for philanthropic actions. However, an individual’s need for contribution spreads widely and can consist of multiple considerations (Baard, Deci & Ryan, 2004). This is enhanced by the rewarding for charitable contribution, coming down to a tangible or intangible reward (Bekkers & Wiepking, 2011). For the dimensions of engagement, the focus solely relies on the

22

intangible rewards, where all the drivers and rewards are intrinsic. Rewards therefore focus on and influence the five dimensions and how this rewarding drives engagement.

This is closely related to a nomological model, such as the input-output model, which is based on the input–mediator–output–input framework (Costa, Passos, & Bakker, 2014). In this context, the inputs are considered to be the dimensions, whereas the rewards for contribution are the drivers for engagement and therefore form the output. According to Conduit et al. (2019), the location of where charitable contribution is formed and decided upon within a person is based on behavioural, emotional/affective, cognitive, spiritual and social (intrinsic) dimensions. However, this is applied in the context of charitable giving in terms of volunteering and devoting time, where this differs slightly. This, nevertheless, serves as a solid foundation for this research to dive in the theoretical gap of investigating the five dimensions (behavioural, emotional, cognitive, spiritual and social). In order to do so, it is eminent to firstly focus on the theoretical domain of engagement and where contributor engagement takes place within this domain.

2.4.2 The Domain of Engagement

All contributions to charity are driven by a certain extent of engagement towards an organisation or its cause (Farmer & Fedor, 2001). In order to understand what drives Dutch individuals to engage with charitable organisations, it is key to understand the broad theoretical domain of engagement with focus on consumer engagement. Engagement refers to involvement, commitment, passion, enthusiasm, absorption, focused effort, zeal, dedication, and energy (Truss et al., 2013).

Within marketing, customer engagement is an influential component when looking at consumer behaviour. Literature has provided insight regarding consumer engagement as a psychological mind-set comprising focal cognitive, emotional and behavioural dimensions (Brodie, Hollebeek, Jurić, & Ilić, 2011). While several studies have explored consumer engagement in different contexts and proposed influences on, and outcomes of, consumer engagement, a number of significant conceptual and empirical contributions remain to be made to this emerging literature stream (Brodie, Hollebeek & Conduit, 2015). However, studies focusing on consumer engagement show the complexity of the subject (Brodie et al., 2011). Where engagement and the specification of consumer engagement are largely covered in literature, the concept is eminently changing along with society (Heinonen, 2018; Waddell, 2002). This causes it to be a convoluted and ever-changing landscape. The complexity is enhanced by the fact that, within the umbrella of consumer engagement, all forms of consumer actions or practices precipitate a slightly different and adapted form of consumer engagement (Dessart, Veloutsou & Morgan-Thomas, 2016). Due to emerging technological advancements, the environment

23

of consumer engagement changed significantly (Yadav & Pavlou, 2014). The majority of current research therefore shifts into several forms and varieties of online consumer engagement. In line with those findings, other studies confirm the multidimensionality of engagement and argue that similar patterns are visible in an online environment (Dessart et al., 2015). Nevertheless, the multidimensionality of consumer engagement and all its branches is controversial and the literature on this topic is often conceptual (Ben-Eliyahu, Moore, Dorph & Schunn, 2018; Dessart et al., 2015; van Doorn et al., 2010; Verhoef, Reinarts & Krafft, 2010; Wirtz et al., 2013). In some former literature, a unidimensional (often behavioural) approach towards engagement is embraced (Jaakkola & Alexander, 2014; Sprott, Czellar, & Spangenberg, 2009; Verhoef et al., 2010). However, this research, based on the Volunteer Engagement Model of Conduit et al. (2019) emanates from, or relates to, Brodie and Hollebeek’s multidimensional works (Brodie et al., 2011; Brodie, Ilić, Jurić, & Hollebeek, 2013; Hollebeek, 2011; Hollebeek, Glynn, & Brodie, 2014; Hollebeek and Chen, 2014).

2.4.3 Consumer Engagement

Consumer engagement is defined in various ways and contexts. It is referred to as the level of an individual’s motivational, brand-related and context-dependent state of mind characterised by specific levels of cognitive, emotional and behavioural activity in direct brand interactions (Hollebeek, 2011). Other research implies it involves the level of a customer's physical, cognitive and emotional presence in their relationship with a product or service organisation (Patterson et al., 2015). This is in line with the definition of the concept of consumer engagement by Brodie et al. (2011), which focuses mainly on the psychological state of mind experienced through interactive consumer moments with an object. However, the multidimensional concept definition is expanded by Hollebeek (2011), which is applied in a volunteering context by Conduit et al. (2019).

Still, the dimensions contributing to the eventual form of consumer engagement evolve and are often contributed to within literature (Dessart et al., 2015). This results in innovation within the context of consumer engagement by application of current dimensions on advanced and newer forms of engagement or the implication of new dimensions for existing forms of consumer engagement (Brodie et al., 2011; Brodie et al., 2013; Dessart et al., 2015; Hollebeek, 2011; Hollebeek & Chen, 2014). An overarching result is the altering concept of consumer engagement and the constant critical attitude towards the concept (Dessart et al., 2016). The evolving concept is mainly caused by emerging technology (Yadav & Pavlou, 2014), where this has a significant effect on the overall concept of consumer behaviour, of which consumer engagement is a subdomain (Dixit, 2017).

24

However, the broad concept of consumer engagement specifies for different environments, where the original relationship marketing perspective is now extended to consumer relationships beyond core purchasing situations and thus expanding (Vivek, Beatty, & Morgan, 2012). This leads to several studies in the broad concept of engagement, however the concept of contributor engagement is relatively unknown. Thus, because of the diversity and quantity of studies regarding the wide range of engagement and its branches, the dimensionality differs per form of engagement (Dessart et al., 2015), which implies that subdomains of consumer engagement (e.g. volunteer engagement and contributor engagement, amongst others) have different influential dimensions on the engagement.

As mentioned earlier, the work of Conduit et al. (2019) is an extension on earlier work of Brodie and Hollebeek, in which the behavioural, emotional and cognitive dimension were put central, but the spiritual and social dimension have been added to the concept of volunteer engagement later. Adding the spiritual dimension to a beneficiary context is new within engagement, but is comprehensive when looking at the overall environment. Spirituality revolves around philosophies and beliefs concerning life’s meaning and how humanity and relationships structure and integrate (MacKinlay, 2003), but also around a “deeper sense of being, meaning and connection, occurring by virtue of interactions with the beneficiary” (Conduit et al., 2019, p. 467). Therefore, spirituality shows a relevant link towards the concept of contributor engagement within consumer engagement due to its influence on philanthropic actions (Spohn, 2003). Including spirituality and therefore religion in this study is a deliberate decision in order to enhance the current concept of contributor engagement.

2.5 Contributor Engagement

Within this research, the Volunteer Engagement Model (Conduit et al., 2019) is used to test the model that was designed for volunteers within the context of contributors to include other types of contribution in addition to donation of time. Where consumer engagement mainly focuses on behavioural, cognitive and emotional dimensions (Hollebeek et al., 2014), Conduit et al. (2019) argue that volunteers also gain a connection with a cause or organisation through a spiritual and social dimension. Although some literature points to the importance of both spiritual engagement (e.g. Zomerdijk & Voss, 2010) and social engagement (e.g. Vivek et al., 2012), these aspects have not been explicitly addressed or captured in this context, and their relevance and relative impact are thus unknown and assumed (Conduit et al., 2019). Although contributor engagement is explored before, considering engagement from a contributor perspective is relatively new and little work has been undertaken and little research has been conducted in this area of study.

25

2.5.1 Volunteer Engagement Model

As elaborated on earlier, the Volunteer Engagement Model (Conduit et al., 2019) focuses on the behavioural, emotional, cognitive, spiritual and social dimensions of engagement. In the remainder of this chapter, all five dimensions are thoroughly discussed and evaluated to provide a deeper understanding of the domain. The model is illustrated in the conceptual framework in figure 3. 2.5.1.1 Behavioural

Behavioural engagement reflects a state of activation and consists of the level of time, energy and physical effort spent on an engagement object (Hollebeek et al., 2014). It draws upon the idea of participation (Charland et al., 2015). The more time, energy and physical effort people give to their role and the organisation (i.e. behavioural engagement), the more value they will place in the achieved outcomes (Rich, Lepine, & Crawford, 2010). For instance in the volunteering context, the act of helping another person and hence investing time and energy in desired outcomes of the role creates value for the volunteer as well as the beneficiary (e.g. the general well-being of both) and the organisation (e.g. supporting and improving the welfare of others) (Gage & Thapa, 2012). Behaviourally engaged volunteers are more likely to engage frequently and more intensively in the role activities with the charitable organisation (van Doorn et al., 2010). This focus on the success of identifiable outcomes of the volunteer behavioural engagement suggests that it is motivated by competence (Deci & Ryan, 2000), or that the investment of time and energy are generating positive task outcomes (Gage & Thapa, 2012).

2.5.1.2 Emotional

Emotional, or also called affective, engagement reflects the emotional connection people invest in their interactions with a focal object (Mollen & Wilson, 2010). It showcases the levels of emotions experienced by, in this case, a contributor, without losing focus of the initial idea of engagement (Dessart et al., 2015). Where the spectrum of emotions is large, there is a clear division between positive and negative emotions (Barrett, Mesquita, Ochsner, & Gross, 2007). This further defines in the level of engagement that is derived from either positive or negative emotional experiences (Vivek et al., 2012). In this study’s context, this means that people invest positive emotions in their interactions with a charitable organisation. This dedication to the organisation can manifest as enthusiasm, inspiration, pride, gratitude or general euphoria (Brodie et al., 2011). However, in the context of contributor engagement, it is very likely that emotional expressions such as trust and confidence play an important role, since the subject comes down to societal responsibility and tends to have a high impact (Vivek et al., 2012).

26

Higher levels of emotional attachment to the organisation makes contributors feel more invested in their activities and perceiving greater emotional rewards (Meier & Stutzer, 2008). In line with this, research suggests that how people spend their money may be at least as important as how much money they earn. Specifically, it is hypothesised that spending money on other people may have a more positive impact on happiness than spending money on oneself. Providing converging evidence for this hypothesis, it is found that spending more of one's income on others predicted greater happiness (Dunn et al., 2008). On the other hand, it is eminent that emotions play in important role for the initial contribution towards a charitable organisation, where the chosen organisation or cause for supporting often has a significant personal meaning or reason (Sargeant, 1999). This results in a certain level of emotional engagement which appears to make the contribution to and interaction with the charitable organisation more memorable, leading to continuing levels of support (Sargeant, Ford, & Hudson, 2007).

2.5.1.3 Cognitive

Cognitive engagement reflects the level of concentration and mental focus given to a focal engagement object (Scott & Craig-Lees, 2010). It refers to durable and active psychological states of mind that a consumer encounters regarding the object for engagement (Dessart et al., 2015). In this context, cognitive engagement helps create a deeper understanding of the role and the organisation, manifesting in an appreciation of the contribution made through the role and the development of cognitive bonds (Harmeling, Moffett, Arnold, & Carlson, 2017). Besides, cognitive engagement represents a psychological disposition in which contributors invest mental effort to understand the volunteer experience and the organisation, with the intent to attain the desired outcomes (Calder, Malthouse, & Schaedel, 2009). Within the context of cognitive engagement in a charitable environment, the amount of time thinking about and reflecting upon a certain charity or charitable contribution is included (Saks, 2006). Therefore, the cognitive dimension for engagement comes down to rationalizing the contributional experience in terms of meaningfulness and whether the form of contribution is valuable towards the desired goal (Conduit et al., 2019).

2.5.1.4 Spiritual

In organisations where the purpose is benevolent rather than profit generation, such as a charitable organisation, there is closer perceived alignment between the spiritual values of the contributor and the organisation or cause (Brophy, 2015). Previous research considers spiritual engagement to be akin to a personal transformation, an expression of humanitarian values, or participation in religious activities (Penman, Oliver, & Harrington, 2013). The notion of spiritual engagement, however, has not

27

been thoroughly considered previously in this context, nor has it been deeply considered as a component of employee or customer engagement of service organisations. Spirituality revolves around philosophies and beliefs concerning life’s meaning and how humanity and relationships structure and integrate (MacKinlay, 2003), but also around a “deeper sense of being, meaning and connection, occurring by virtue of interactions with the beneficiary” (Conduit et al., 2019, p. 467). Therefore, spirituality shows a relevant link towards the concept of contributor engagement within consumer engagement due to its influence on philanthropic actions (Spohn, 2003). However, spirituality is often confused with religion (Penman et al., 2013). Where in this concept the belief in some sort of ‘higher power’ is included, it is not similar. Still, within the spiritual dimension, religion is considered to be a component or element of the dimension and therefore intertwined (Conduit et al., 2019; Penman et al., 2013). In the context of charitable giving and charity, the spiritual dimension shows a relevant link towards the philanthropic actions. Especially because many religions (Christianity, Islam and Judaism) require the religious to do good for others and the Islam also requires Muslims to give to the less fortunate (Franco et al., 2010). Thus the added spiritual factor gives more insight in what role religion plays and is therefore relevant when looking at charities and the origin of its contributions.

2.5.1.5 Social

In the field of social psychology, social engagement is conceptualised as a sense of initiative or involvement with social stimuli, being part of social activities and interacting with others (Achterberg et al., 2003). The notion of social engagement is similarly represented in business literature, with several authors including a social dimension of engagement (e.g. Vivek et al., 2012). Other research recognises the social interaction embedded in the engagement experience, and propose that talking to other people and sharing experiences makes people feel more connected and part of the group, giving rise to a sense of engagement with that group (Calder et al., 2009). Besides, there is a social aspect in charitable contributions, since a study shows that social influence has a severe impact on individual contribution and informing contributors about others' contributions can significantly increase or decrease their own contribution (Bryant, Jeon-Slaughter, Kang, & Tax, 2003). Younger volunteers, in particular, recognise personal and social benefits to contributing including strengthening social relationships, developing skills, enhancing career prospects, as well as the more traditional contributing to community and “making a difference” (Walsh & Black, 2015). While contributors typically have no expectation of material pay or benefit to themselves, this attribute does not preclude them from experiencing benefits from their involvement (Wilson, 2000). Hence, charitable organisations must deepen their understanding of the nature of contributor engagement and the value outcomes contributors seek if they wish to retain a base of contributors.

28

Where the social dimension is defined by a contributor’s connection with other contributors in relation to the reciprocal experiences with the organisation or cause (Conduit et al., 2019), the social dimension looks outside the concept of devoting time towards a cause or organisation. Due to emerging technological advancements, the environment of consumer engagement changed significantly (Yadav & Pavlou, 2014), and therefore also the social aspect of charitable contributions. Social media allows contributors to like, share and create content regarding a cause, organisation or activity and to, thereafter, share this online (Dolan, Conduit, Fahy, & Goodman, 2015). This results in an unpredictable reach whenever the publication is public, but also in the forming of groups with a shared interest or goal (Schmidt & Iyer, 2015). Due to this social (media) behaviour and emerging technology, the online social interaction in support groups and online communities is therefore even preferred over offline social interaction (Chung, 2013). Within the context of charity and charitable giving, the social impact is undeniable and especially this online behaviour proves the importance of the engagement form of (co-)creation of content for this study.

2.6 Conceptual Framework

Figure 3 – Conceptual Framework

Even though the model of engagement is more extensive, this paper excludes the drivers, also referred to as the antecedents, of contributor engagement. This allows the researchers to more intensively focus on the various dimensions that impact the degree of engagement towards DCS, namely behavioural, emotional, cognitive, spiritual and social. More specifically, the conceptual framework illustrates the potential influence of the five dimensions on contributor engagement, as well as a potential influence among the dimensions. If executed correctly, the research outcomes will entail what motivates Dutch individuals to engage with DCS and, in turn, to what extent this model influences that correlation. This leads to possible charitable contribution to DCS, which, in this context, consists of the donation of money, the devotion of time and the (co-)creation of content.

29 2.7 Hypotheses

In order to test the potential relationship between two or more concepts or variables, a set of hypotheses has been established to form a theory (Blaikie, 2009). The hypotheses are based on the dimensions of engagement published by Conduit et al. (2019). Where the society and the landscape of the charity sector are changing, it is eminent to explore what motivates Dutch individuals to engage with DCS. The dimensions of engagement form a solid base to anticipate on the changing needs and wishes within the society and therefore serve as a solid framework to test. The outcomes of the developed hypotheses will eventually determine the influence of the dimensions on contributor engagement.

H1: The behavioural dimension has a significant influence on the contributor engagement of Dutch individuals towards DCS.

H2: The emotional dimension has a significant influence on the contributor engagement of Dutch individuals towards DCS.

H3: The cognitive dimension has a significant influence on the contributor engagement of Dutch individuals towards DCS.

H4: The spiritual dimension has a significant influence on the contributor engagement of Dutch individuals towards DCS.

H5: The social dimension has a significant influence on the contributor engagement of Dutch individuals towards DCS.

H6: The five dimensions of engagement combined have a significant influence on the contributor engagement of Dutch individuals towards DCS.

H7: The five dimensions all have a significant influence on each other when looking at the contributor engagement of Dutch individuals towards DCS.

30

3. Research Methodology

______________________________________________________________________________

The aim of this chapter is to provide the research methodology executed to conduct this research paper. It is key to carry out this process adequately in order to come up with trustworthy outcomes and conclusions to tackle the research problem at hand.

______________________________________________________________________________ 3.1 Introduction

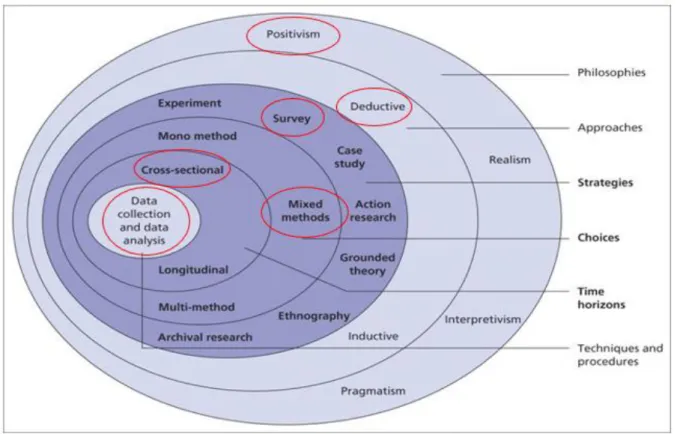

Research methodologies are referred to as the process of techniques and procedures to obtain and analyse data. This includes questionnaires, observation and interviews as well as both statistical and non-statistical analysis techniques, also known as quantitative and qualitative approaches (Saunders, Lewis, and Thornhill, 2016). The selection of the suitable research methodology is crucial for the conclusions that are to be made about a phenomenon. Besides, it is imperative that this research method is within the limits of time, money, feasibility, ethics and availability to measure this phenomenon correctly (Blakstad, 2019). This structure is illustrated in the research onion in figure 4, resembling the various research layers (Saunders et al., 2016). The marked components represent the research path for this study.

31 3.2 Research Philosophy

Several philosophical approaches are possible in the science of research (Holden & Lynch, 2004). As illustrated in the research onion, the outer layer resembles the different philosophies; positivism, realism, interpretivism and pragmatism (Saunders et al., 2016). For this research, the applicable research philosophy is positivism, which is a philosophy that advocates the observation of a phenomenon from an external and objective perspective (Blumberg, Cooper, & Schindler, 2011). This research philosophy suits the context at hand, since it aims to conduct an in-depth analysis of the engagement behaviour of Dutch individuals towards DCS.

3.3 Research Approach

The study revolves around a deductive research approach, as it starts from a general observation and aims to explain a specific phenomenon through the investigation of an existing theory (Saunders et al., 2016). The positivistic philosophy leads to a deductive perspective, as the research aims to investigate and explain contributor engagement by the means of a general observation derived from a theory. This is a suitable approach, since the Volunteer Engagement Model (Conduit et al., 2019) allows the researchers to investigate and evaluate the dimensions of engagement of Dutch individuals towards DCS. Furthermore, the interviews allowed the research to be more extensive by assessing and enriching the quantitative research findings.

3.4 Research Design

The research design is a key component of the research methods. In simple terms, a research design can be described as the overall strategy that is used to conduct a research study (Saunders et al., 2016). More specifically, a research design is the blueprint or plan that will be used by researchers to answer a specific research question (Bloomfield & Fisher, 2019). It will follow a sequential mixed-method research design, which entails both qualitative and quantitative research methods. This is carried out with the purpose of expanding or elaborating on the findings at each stage (Saunders et al., 2016) and allows the researchers to obtain a better understanding of the research problem (Creswell, 2012). When used in combination, quantitative and qualitative methods complement each other and allow a more robust analysis, taking advantage of the strengths of each (Green, Caracelli, & Graham, 1989; Miles & Huberman, 1994; Green & Caracelli, 1997; Tashakkori & Teddlie, 1998).

3.5 Research Strategy

After selecting the suitable research design, it is imperative to elect an appropriate research strategy. This is referred to as the overall plan of conducting research with its techniques and procedures

32

(Dantzker & Hunter, 2011). For this paper, a survey research strategy has been adopted in order to enable the researchers to meet the research objectives and answer the research question (Saunders et al., 2016) in an easy, cheap and safe way for large numbers of individuals (Dantzker & Hunter, 2011). To cross-check the research findings derived from the questionnaire, various semi-structured in-depth interviews were carried out within the sample of the population to obtain a better understanding of identified themes (Saunders et al., 2016). Altogether, this allowed the researchers to collect an extensive amount of data from a variety of sources within the available framework of time and resources. 3.6 Research Sampling Strategy

The objective of most researches is to receive information about a population (Zickermann, 2014). The research population signifies the set of all objects that possess some common set of characteristics with respect to a marketing research problem (Kumar, Aaker, & Day, 2002). Since it is not attainable to research the entire Dutch society, sampling methods are often used to carry out the research. This involves any procedure that draws conclusions based on measurements of a portion of the population. In other words, a sample is a subset from a larger population (Zikmund, Babin, Carr, & Griffin, 2010). More specifically, it revolves around a mix of purposive sampling, voluntary sampling and convenience sampling. In terms of quantitative data collection, the questionnaire was distributed within the professional and personal network of the researchers via online channels. In turn, the qualitative data collection resulted from a voluntary sampling approach among the respondents of the questionnaire. 3.7 Data Collection

3.7.1 Primary Research

The primary research for this paper, the field research, is obtained through the distribution of a questionnaire in terms of quantitative research and various in-depth interviews in terms of qualitative research. Through this, it was feasible to assess the contributor’s engagement towards DCS in an extensive and trustworthy way. The questionnaire was distributed online, which grants the opportunity to reach a fairly large number of individuals and broader area coverage in an effective way in terms of money and time (Dantzker & Hunter, 2011). This was carried out through online channels such as LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp and Microsoft Outlook. Besides, the in-depth interviews served the purpose to obtain a deeper understanding of the individual’s motives and beliefs (Saunders et al., 2016).

33

3.7.2 Secondary Research

The secondary research for this study, the desk research, was gathered through the use of several sources. Trends, figures and analyses are derived from relevant and trustworthy sources to establish a framework for this paper. Key concepts that contributed to this included ‘engagement’, ‘contributor’ and ‘charity’, amongst others, while other relevant data were derived from secondary and tertiary sources such as academic journals and books. Search engines that were used to retrieve secondary data entailed Primo (Primo, 2020) by Jönköping International Business School, Google Scholar (Google Scholar, 2020) and Google Books (Google Books, 2020). Key terms for these searches entailed ‘research methodology’, ‘data analysis’ and ‘sampling strategy’, amongst others.

With regards to the data collection processes, it is essential that the outcomes represent trustworthy outputs. In order to assure that is the case, the questionnaire used throughout this research is based on reliable and valid previous research that serves as a guideline (Conduit et al., 2019). The software Qualtrics was used for constructing, online distributing and gathering the questionnaire, which is a professional tool available through Jönköping International Business School. Electronic collection, however, required careful consideration of how the study was advertised and how data was collected to ensure high quality data and validity of the findings (Cantrell & Lupinacci, 2007), since it tends to come along with individuals that refuse to cooperate in the research, also known as non-respondents (Zikmund et al., 2010).

3.8 Questionnaire Design

3.8.1 Constructs

As mentioned before, a questionnaire based on the Volunteer Engagement Model (Conduit et al., 2019) is used as a solid framework for accurate and trustworthy questionnaire results. The questionnaire design can be found in table 1. The constructs of the questionnaire were based on the dimensions of this academic foundation; behavioural, cognitive, emotional, spiritual and social, including the original internal reliability scores by Conduit et al. (2019). The component of value-in-context (Conduit et al., 2019) is deliberately excluded, due to its irrelevance to this study. The questionnaire, however, has been translated from English to Dutch for distribution purposes in order to fit the research paper at hand. The Dutch version of the questionnaire can be found in appendix 2.