Attitude-Behavior Gap

in sustainable clothing

consumption

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Digital Business AUTHORS : Cansu Tetik - 19920819T586

Ouafaa Cherradi - 19941201T562

JÖNKÖPING May, 2020

General aspects and findings on the main barriers influencing

sustainable purchase intention of Dutch consumers

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Attitude-Behavior Gap in sustainable clothing consumption Authors: Ouafaa Cherradi & Cansu Tetik

Tutor: Matthias Waldkirch Date: 2020-05-18

Key terms: “Attitude-Behavior Gap”, “Sustainable fashion”, “Sustainable fashion consumption”, “Theory of Planned Behavior”

Abstract

The attitude-behavior gap is an important theme in social research. The purpose of the study is to identify the main barriers that influence the intention to purchase sustainable clothing with the underlying thought to understand what prevents consumers from converting pro-sustainable attitudes into actual purchase behaviors. The study is based on the Theory of Planned Behavior by Ajzen (1991) and a quantitative methodology is followed. The findings show that trust and environmental knowledge are the main barriers that drive the attitude-behavior gap. The outcomes of this research provide thorough ways in which stakeholders can better understand the factors influencing the sustainable purchase intentions in order to anticipate accordingly. As a result, companies can use these findings to design effective strategies to encourage sustainable options among young generations who are presumed to constitute the main market of sustainable fashion consumption in the future.

Acknowledgement

First of all, thank you for your interest in this study!

The following thesis describes the results of our graduation research project regarding the attitude-behavior gap in the fashion industry, from February 2020 until May 2020.

We have many people to thank for finalizing this thesis. First, we would like to thank our supervisor Matthias Waldkirch, for providing us with guidance, support and feedback during this wonderful journey. Second, we would like to express a special thank you to fellow classmates for their input and critical eye. Their feedback has been very helpful to present the dissertation as it is today. Third, a sincere gratitude to all our participants for their time and effort.

Last but not least, a special thanks to our close circle for the support throughout the process. Ouafaa Cherradi & Cansu Tetik

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS ... III

1. INTRODUCTION ... 6

1.1BACKGROUND ... 6

1.2PROBLEM STATEMENT ... 7

1.3PURPOSE AND RESEARCH QUESTION ... 9

2. LITERATURE REVIEW ... 10

2.1SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT IN THE FASHION INDUSTRY ... 10

2.2SUSTAINABLE CONSUMPTION IN FASHION AMONG YOUNG GENERATION GROUPS ... 11

2.2.1 Sustainable clothing consumption ... 11

2.2.2 Consumer behavior of millennials and Gen Z ... 12

2.3.THE ATTITUDE-BEHAVIOR GAP ... 13

2.3.1 Theory of Planned Behavior ... 13

2.3.2 Factors influencing sustainable purchase intention ... 15

3. HYPOTHESES ... 17

3.1HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT ... 17

3.2ATTITUDE ... 17

3.3SUBJECTIVE NORMS ... 18

3.4ENVIRONMENTAL KNOWLEDGE ... 19

3.5TRUST IN A BRAND/PRODUCT ... 21

3.6PRICE OF THE PRODUCT ... 22

3.7CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK ... 23 4. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY ... 25 4.1RESEARCH DESIGN ... 25 4.2RESEARCH PHILOSOPHY ... 25 4.3RESEARCH APPROACH ... 26 4.4RESEARCH PURPOSE ... 26 4.5DATA COLLECTION ... 27 4.6SAMPLING PROCEDURE ... 28 4.7SURVEY CONSTRUCTION ... 28

4.8MEASUREMENT INSTRUMENTS OF THE VARIABLES ... 29

4.8.1 Independent variables ... 31

4.8.2 Dependent variable ... 33

4.9DATA ANALYSIS ... 33

4.10ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS ... 34

4.11LIMITATIONS OF METHODOLOGY ... 34

5. FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS ... 36

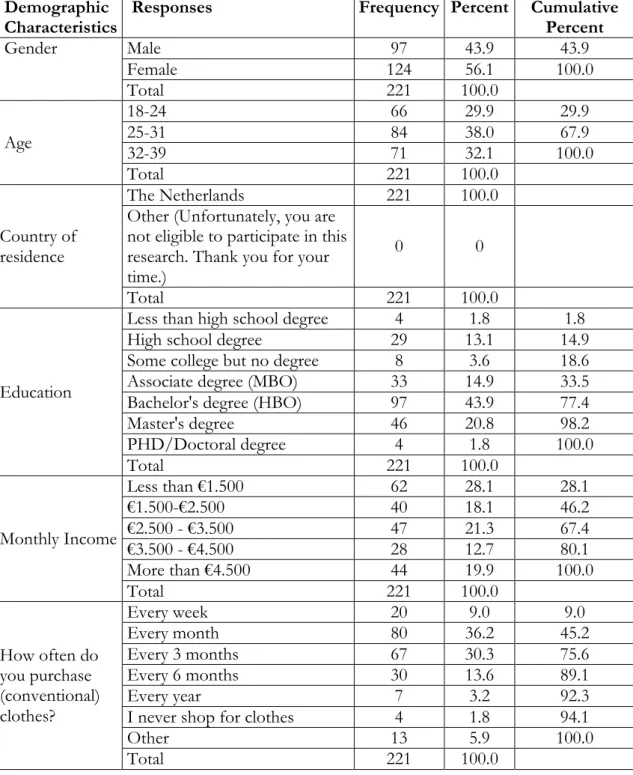

5.1SAMPLE PROFILE ... 36

5.2DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS FOR RESEARCH VARIABLES ... 36

5.3FACTOR ANALYSIS ... 38

5.4MULTIPLE REGRESSION ANALYSIS ... 39

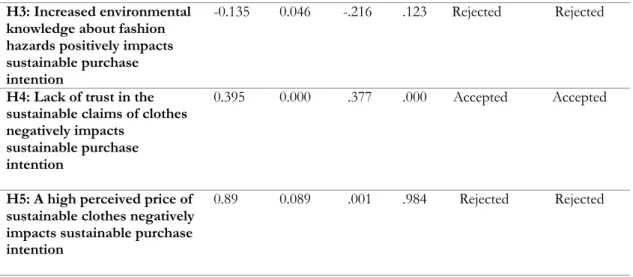

5.5HYPOTHESES TESTING ... 41

6. CONCLUSION ... 45

7. DISCUSSION ... 46

7.1.MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS ... 47

7.2LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH ... 49

APPENDIX II – MEASUREMENT MODEL ... 66

APPENDIX III – TABLES AND GRAPHS ... 68

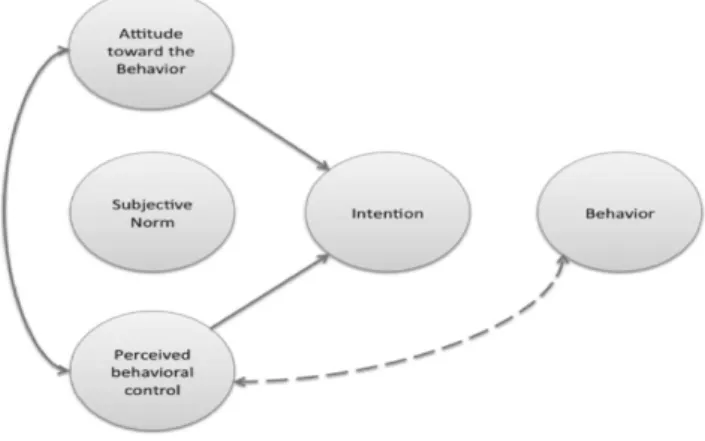

FIGURES FIGURE I:TPB-MODEL (AJZEN,1991) ... 15

FIGURE II:CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK ... 24

TABLES TABLE I:OPERATIONALIZATION OF THE VARIABLES ... 30

TABLE II:DEMOGRAPHIC STATISTICS ... 68

TABLE III:DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS ... 37

TABLE IV: KMO AND BARLETT’S TESTA ... 38

TABLE V: TOTAL VARIANCE ... 69

TABLE VI: COMPONENT MATRIX ... 70

TABLE VII: RELIABILITY STATISTICS ... 39

TABLE VIII: REGRESSION ANALYSIS (MODEL SUMMARY) ... 40

TABLE IX: REGRESSION ANALYSIS (ANOVA) ... 40

TABLE X REGRESSION ANALYSIS (COEFFICIENTS) ... 41

TABLE XI: HYPOTHESES TESTING ... 41

TABLE XII: CORRELATION AGE-KNOWLEDGE ... 75

Abbreviations

C2B Consumer to Business

CSR Corporate Social Responsibility

eco- ecology/ecological

EFA Exploratory Factor Analysis

e.g. example given

GDP Gross Domestic Product

Gen Y Generation Y (Millennials)

Gen Z Generation Z

KMO Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin

1. Introduction

______________________________________________________________________ The following section serves as a preface where concepts related to sustainable fashion and the attitude-behavior gap are introduced to get an impression of the problem.

______________________________________________________________________

1.1 Background

In this decade, individuals and companies are becoming increasingly aware that the current Western lifestyle is not sustainable (Ulanowicz, 2019). The repercussions of unmonitored consumption activities within this disposable society are currently leading to environmental, social and economic degeneration (Hume, 2010). Besides decreasing natural resources, global warming, climate change and increasing pollution, the fashion’s hazardous impact on the environment remains a worldwide concern (Gardetti & Torres, 2013; Amed et al., 2019; United Nations, 2019; Freudenreich & Schaltegger, 2020; Guo et al., 2020). Pollution in the fashion industry is caused by unrestrained utilization of chemicals and non-domestically produced textiles (Dickenbrok & Martinez, 2018). In spite of its detrimental effects, the fashion industry has a worth of $3 trillion and is expected to grow in the near future (Wang et al., 2019). Given its major size, the industry requires several changes regarding consumption habits and production processes (Cachon & Swinney, 2011). Production processes have changed over time (Cachon & Swinney, 2011) due to the trend of fast fashion causing wastage (Cachon & Swinney, 2011; Maldini et al., 2017). An amount of no less than $500 billions of value is lost annually on account of clothing underutilization and insufficiency of recycling (UN Fashion Alliance, 2020).

Countries across the world are starting to face this environmental threat (Joshi & Rahman, 2015). The Netherlands, among other European countries, is foreseeing the urge to move in the direction of minimizing harmful impacts of their environmental activities (van den Adel & Zeegers, 2017; Maldini et al., 2017). This realization in combination with increasing concerns has led to the emergence of sustainable development (Joshi & Rahman, 2015), highlighting the necessity for companies to advocate sustainability (van den Adel & Zeegers, 2017). Companies are becoming more aware of the repercussions of not being socially responsible (Wang et al., 2019) as it can result in losing competitive advantages (Wang et al., 2019; Guo et al., 2020). In order to change course, companies are integrating sustainability into their marketing strategies along with introducing sustainable innovations (Al Mamun et

al., 2018). To meet the needs for sustainability, retail stores are offering sustainable collections. Some retail stores do that through collections devoted to specific causes such as Burberry’s and Vivienne Westwood’s collaboration to save the rainforest (Hodge, 2018). Other retail stores are striving sustainability through campaigns that promote their commitment to carbon neutrality such as Reformation, a sustainable women's apparel brand, with its “Carbon is cancelled” campaign in order to offset carbon footprint (Greenstein, 2019).

As a consequence of the fashion industry shifting towards a more conscious mindset (Weed, 2017; Amed et al., 2019) and brands addressing environmental and social issues (Amed, 2018), there is little effect on actual consumer demand (Jacobs et al., 2018). The foregoing has proven to be one of the reasons why the sustainable clothing market is still relatively small compared to other markets, even though consumers are aware of the need and its beneficial effect (Reimers et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2019). This inconsistency, often referred to as the attitude-behavior gap in academic literature (Joshi & Rahman, 2015; Hassan et al., 2016; Henninger et al., 2017; Wiederhold & Martinez, 2018), looks into the current barrier between motivation and consumption. Many organizations are struggling with this so-called “gap” characterized by consumers who claim to be concerned about the environment but do not necessarily showcase this in their buying behavior (Joshi & Rahman, 2015). Sustainable consumption behavior relies on more than awareness alone (Joshi & Rahman, 2015). Consumers make buying decisions on a daily basis, sometimes not being aware of the individual and situational factors that drive them to this decision (Joshi & Rahman, 2015; Lemon & Verhoeven, 2016). The assumption behind this instance is that decision-making expresses apart from attitude, also price preferences, social influences, beliefs and the level of knowledge (Joshi & Rahman, 2015; Sreen et al., 2018). In this sense, it can be argued that consumers are facing barriers that prevent them from converting sustainable attitudes into behaviors (Carrete et al., 2012; Moser, 2016) and naturally tend to overlook environmental concerns of their purchases (Joshi & Rahman, 2016).

1.2 Problem statement

Today’s consumption habits are heading into a direction that might soon result in negative consequences if little or no measures are taken (Joshi & Rahman, 2016). Even though sustainability is an emerging trend, consumers yet do not “walk their talk” and repeatedly buy clothes that have harmful environmental impacts, irrespective of their willingness to purchase sustainable alternatives (Wiederhold & Martinez, 2018). In spite of consumers’

increasing interest in sustainability (Amed, 2018), it does not manifest in their consumption behavior (Niinimäki, 2010; McDonagh & Prothero, 2014; Jacobs et al., 2018; Bernardes et al., 2018; Dickenbrok & Martinez, 2018; Arasteh, 2019).

In recent years, complexities among consumers’ intention on sustainability and actual buying behavior have been investigated by different academicians (Belz & Peattie, 2012; Jacobs et al., 2018). Although the factors influencing the behavior are identified, their direct effect on sustainable purchase intention has not been extensively studied (Jacobs et al., 2018). This study therefore focuses on purchase intention to elucidate the role of the moderator “intention” in the attitude-behavior relationship, which is the key determinant of behavior (Ajzen, 1991) that observes the antecedents in the pre-consumption phase (Moser, 2016). Accordingly, attitude-behavior gaps have received great importance in research studies regarding sustainable consumption within different fields such as sustainable household products, food and personal care (Vermeir and Verbeke, 2006; Bray et al., 2011; Moser, 2016; Longo et al., 2017; Diddi et al., 2019). Relatively limited research has been conducted in the context of sustainable clothing (Hassan et al., 2016; Jacobs et al., 2018). This is quite remarkable considering the huge problems of unsustainability inherent in this industry (Jacobs et al., 2018; Guo et al., 2020). Given the importance of this occurrence, it is essential to understand the gap in sustainable fashion consumption in the Netherlands. Due to extraordinary results of overconsumption (Maldini et al., 2017), the Dutch clothing industry is in transition and making strides towards sustainability (van den Adel & Zeegers, 2017). This movement presents great potential to conduct research in this country. Findings derived from a survey by PwC, demonstrate that Dutch consumers are not quite the eco-friendly buyers (PwC, 2019). While nearly half of Dutch consumers (46 percent) show a positive attitude towards sustainable consumption (Duurzaam-ondernemen, 2018), just over 5 percent of consumers consider sustainable components in their clothing (Statista, 2019). However, there is a potential growth forecast among younger generations in the Netherlands to become more sustainable (Kamphuis, 2019; Statista, 2020). Millennials (Gen Y) and Generation Z (Gen Z), in particular, hold pro sustainable attitudes and are becoming more aware of the power of making concious consumption decisions in their journey (Han et al., 2017; Diddi et al., 2019). Sustainable attitudes alone, however, will not produce conclusive results on the actual sustainable buying behavior (Bernardes et al., 2018). Following this line of thought, it could be concluded that an attitude-behavior gap exists among Dutch fashion consumers.

1.3 Purpose and Research Question

To gain a deeper understanding of complex factors affecting sustainable purchase intention, the current study attempts to expand the still narrow scope of research on sustainable fashion consumption in the Dutch field. Hereby, the focus lies on two generation groups: Millennials, born between 1981-1996 (Bernardes et al., 2018) and Gen Z, born between 1997-2012 (Noble et al., 2009). These young generations are considered to be the next customer groups that will shape the future and are likely to contribute to a climate-safe environment (Vermeir & Verbeke, 2006). An explanatory study is essential to identify the main barriers hindering the magnitude of this gap as there is a lack of understanding of the constraints that stand in the way of Dutch young consumers’ intention to purchase sustainable clothing. The following citation by Connel (2018) emphasizes the importance of understanding barriers to achieve sustainable goals:

‘’Overall, we must better understand the barriers facing a transition to sustainability [...] to overcome these obstacles and realize the fashion industry’s full potential to achieve sustainability.’’ (Connel, 2018, p. 17)

Therefore, the main purpose of this dissertation is to identify prevailing barriers behind the attitude-behavior gap in sustainable fashion consumption through consumer-centric research and, ultimately, seek applicable solutions for players in the fashion industry on how to bridge the prevailing gap between attitude and behavior. Hence, the following main Research Question (RQ) is formulated:

“What are the main barriers that influence consumers' intention to buy sustainable clothing?” The answer to this main question results in strategic advice specifically developed for marketers, managers and CSR specialists of (potential) ethical fashion brands by examining an advanced understanding of what shapes the intention of Dutch consumers to make ethical consumption decisions. In addition, the findings of this dissertation provide fashion retailers and brands with managerial insights on what prevents Dutch consumers from translating sustainable purchase intentions into sustainable clothing consumption. At the same time, the results yield public policy and communication recommendations for stimulating the purchasing behavior amongst young consumers.

2. Literature Review

______________________________________________________________________ The purpose of this chapter is to provide theoretical background to the emergence of sustainable fashion in relation to the attitude-behavior gap; how this gap is formed, and which factors influence this gap.

______________________________________________________________________

2.1 Sustainable development in the fashion industry

Sustainability refers to the development that meets current needs without compromising the needs of future generations (Joy & Peña, 2017). The fashion industry is a polluting and resource-intensive industry due to the emergence of fast fashion. Therefore, the industry requires sustainable solutions (Joy & Peña, 2017). Fast fashion is characterized by its short product life cycles with high volatility of demand and fast-changing large quantity production of seasonal fashion content (Cachon & Swinney, 2011). This trend showcases frequent deliveries to stores with high impulsive purchase decisions of consumers as a result (Cachon & Swinney, 2011). Retail companies are facing environmental challenges as a result of fast fashion (Javed et al., 2020). The global supply chain of fast fashion companies is responsible for pollution, chemical wastes, eco-hazards, the upswing in consumption, and environmental catastrophes in developing countries (Yang et al., 2017; Guo et al., 2020). Likewise, the clothing industry outsources the workforce from third-world countries to exploit cheap labor opportunities (Dabija et al., 2016; Javed et al., 2020).

The future success of the fashion industry relies on decreasing the environmental harms during the life cycle of apparel production (Joy & Peña, 2017). Manufacturing both cotton and polyester fibers have the greatest negative impact on the production process of clothes, especially cotton is detrimental to the environment considering its ubiquitousness (Joy & Peña, 2017). During production processes, cotton uses a lot of water (Joy & Peña, 2017). Polyester production, on the other hand, utilizes significantly less water and no pesticides (Joy & Peña, 2017). Nylon and wool are also harmful fibers to the environment due to extensive land use, over-grazing and waster waste during the production process (Joy & Peña, 2017). To tackle the environmental impacts, sustainable fashion solutions are integrated in repositioning the strategies during the production and consumption stage (Joy & Peña, 2017). Diminishing environmental impacts is necessary in order to protect the environment (Joy & Peña, 2017). Even though consumers are of the opinion that making a valuable change should start with the operational practices of organizations rather than adapting

consumption patterns on an individual level (Han et al., 2017), prospects contrariwise argue that consumption habits should be changed first (Shen et al., 2012).

2.2 Sustainable consumption in fashion among young generation groups

Greater protection and attention to the environment have pushed consumers towards more sustainable decision making (Park & Lin, 2018). Consumers’ consumption habits are the main influential determinants behind sustainability in the fashion industry (Hassan et al., 2016). Sustainable consumption is related to slow fashion movements in which sustainable or ethical consumption is pursued by acting in a socially responsible way (Joshi & Rahman, 2015). The perception of what is considered sustainable and what is not in regard to consumption is of subjective interpretation (Bray et al., 2010, Lundblad & Davies, 2016; Geiger et al., 2017). In this sense, sustainable consumption can concern sustainable clothing purchases (Joshi & Rahman, 2015; Henninger & Singh, 2017; Park & Lin, 2018), whereas in other cases it can be interpreted as the conscious and minimal consumption behavior of conventional clothes (Sánchez & Raymaekers, 2018).

Consumers have the ability to choose from a wide variety of sustainable clothing types: re-purposed & recycled, high quality & timeless design focused, vintage & secondhand, vegan, custom made and rent, fair & ethical, pro-environment and loan, swap & share (Henninger & Singh, 2017). In the context of this study, sustainable clothes are defined as clothes that are made from environmentally friendly materials (e.g. recycled materials) along with environmentally responsible production (e.g. no child labor) to minimize adverse environmental impacts (Joy & Peña, 2017). Minimizing the impact is closely linked with recycled materials and ethical production processes (Chan & Wong, 2012; Joy & Peña, 2017) or switching to alternate fibers with low-resource intensity (Joy & Peña, 2017).

Following up on the various sustainable clothing types, consumers have the ability to make conscious fashion choices and have the opportunity to consider sustainable components in their clothing (Henninger & Singh, 2017). Also, consumers in this digital world have access to various business operations, thus it is efficient for (sustainable) consumers to keep an eye on the fashion industry sustainable practices (Kauppi & Hannibal, 2017). Sustainable practices are closely associated with consumption patterns that are developed at a young age and form the basis for consumer behavior as an adult (Etgar & Tamir, 2020). Changing consumer behavior at an early stage is, therefore, critical as today's youth will serve as a role

model for subsequent generations (Etgar & Tamir, 2020). Kang et al. (2013) argue that it is of great importance to target generations, especially the younger ones, to establish lasting attitudes and behaviors towards environmentally sustainable consumption of clothing.

Young consumers have been reported to be a significant fashion-conscious consumer group since they are in the development stage of long-term mindsets (Vermeir & Verbeke, 2008). The consumption behavior of millennials is driven by increased knowledge about fashion. Millennials seek for value in clothes that are in line with their own ideals (Noble et al., 2009). This generation values functional aspects of brands and highly expects value for their money (Moser, 2016). Preceding research demonstrates that this group is willing to pay more for clothes that are made from ecological raw materials (Noble et al., 2009; Moser, 2016). Gen Z, on the other hand, are active fashion consumers and their influence on their family and their decision making should not be underrated (Morgan & Birtwistle, 2009). As a matter of fact, in household decision making, they are the major source of information as they are true digital natives (Morgan & Birtwistle, 2009) who are familiar with technology, online shopping and share information at a high speed (Morgan & Birtwistle, 2009).

Even though there is a difference between how these two generations think and act, they have a similar mindset when it comes to the concept of sustainability and prefer long-lasting, high-quality apparel over disposable items (Morgan & Birtwistle, 2009; Etgar & Tamir, 2020). These two groups are exposed to a constant flow of options, yet they developed better mechanisms to cope with sustainable alternatives without being uncomfortable about it (Etgar & Tamir, 2020). Both generation groups are information seekers who have a distinct sense of responsibility (Morgan & Birtwistle, 2009) by paying attention to where their products are made, by whom, and with what materials. Herewith, trust in the brand and sustainable claims are of great importance (Braga Junior et al., 2019). If trust is perceived in combination with a sustainable brand offering high quality in combination with an affordable price, it will result in greater sustainable consumption purchases (Wang et al., 2019). Most of the time, consumers within this age-category find the prices of sustainable clothing too expensive, thus leading to less sustainable purchase intentions (Wang et al., 2019). In conclusion, young consumers are known to be the most consumption-oriented generation group that hold positive attitudes towards sustainability due to increasing awareness of sustainability and previous education on environmental issues (Morgan & Birtwistle, 2009; Hume, 2010). However, pro sustainable attitudes are not in any case predictors of behavior

for young consumers (Hume, 2010). In fact, young consumers show almost no sign of adopting sustainable practices when it comes to sustainable purchasing practices (Hume, 2010; Niinimäki, 2010).

2.3. The Attitude-Behavior Gap

Taking into consideration scientific findings, it can be concluded that the attitude-behavior gap in sustainable purchasing behavior also accounts for millennials and Gen Z, though their positive sustainable attitudes would suggest otherwise (Morgan & Birtwistle, 2009; Niinimäki, 2010; Maldini, 2017). The attitude-behavior gap presents an obstacle to sustainable development due to the fashion industry’s increasing attention to sustainability and the lack of sustainable fashion consumption (Joshi & Rahman, 2015). In the field of sustainable consumption, the discrepancy between attitudes and actual behavior is referred to as the attitude-behavior gap (Hassan et al., 2016; Park & Lin, 2018; Jacobs et al., 2018). The gap is also known as intention-behavior gap (Caruana et al., 2016), knowledge-behavior gap (Markkula & Moisander, 2012) or value-behavior gap (Joshi & Rahman, 2015).

A positive relationship between consumers’ attitudes and purchase intention of sustainable products is validated (Jacobs et al., 2018) and while the demand for sustainable products are increasing (Bong Ko & Jin, 2017), an attitude-behavior gap is discovered in both past literature and practice regarding sustainable clothing consumption (Niinimäki, 2010; Chan & Wong, 2012; Reimers et al., 2016). The attitude-behavior gap is formed when consumers expect companies to be socially responsible and produce sustainable products, but do not translate their positive attitudes into actual purchases (Joshi & Rahman, 2015). Consumers might face barriers when trying to convert sustainable purchase attitudes into sustainable purchase behaviors due to factors that stand in the way (Stern, 1999; Vermeir & Verbeke, 2006; Joshi & Rahman, 2015). In this context, barrier is defined as the inability or unwillingness. Niinimäki (2010) states that consumers’ sustainable clothing decision making is a complex process, considering the named factors causing this actual gap. In order to elaborate on why attitudes alone do not predict behavior and will not provide profound results on young consumers’ behavior in purchasing sustainable clothing, it is crucial to identify how the intention is shaped.

Ajzen (1991) established the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) in which he emphasizes the effect of attitude, subjective norms (also known as social norms) and perceived behavioral

control on intention. TPB deals with the complexities of human social behavior and is one of the most cited theory that is frequently applied in the attitude-behavior context (Ajzen, 1991). This theory is widely applied and acknowledged to elucidate sustainable intention and behavior (Moser, 2016) and observes the antecedents of consumer intentions in the pre-consumption phase (Ajzen, 1991), so is the present research.

Attitudes, subjective norms and perceived control over the behavior are commonly found to predict behavioral intentions on a high level of accuracy (Ajzen, 1991). As a result, these intentions, in combination with perceived behavioral control, are responsible for a fair proportion of variance in behavior (see Figure I). Attitude has been considered as an independent context for foreseeing behaviors (Al Mamun et al., 2018) and can be defined as the path of a consumer's assessment of particular behaviors (Ajzen, 1991). Fishbein and Ajzen (1975) describe attitude as a positive or negative evaluation of an object, action, issue or individual. The well-established TPB theory proposes that behavior is affected by behavioral intentions in which attitude is influenced by behavioral beliefs and attributes of a particular object that guides people to act consistently (Johnstone and Tan, 2015; Braga Junior et al., 2019). According to various studies, a positive attitude leads to a greater sustainable buying behavior and vice versa (Ajzen, 1991; Kim & Chung, 2011; Al Mamun et al., 2018; Jacobs et al., 2018). Therefore, attitude is considered the main predictor of behavior (Ajzen, 1991). Subjective norms refer the perceived social pressure to perform a certain behavior (Ajzen, 1991). Studies conducted by Ajzen (1991) and Sreen et al., (2018) imply that social influence is a so-called key driver to sustainable purchase intention that is determined by a combination of positive and negative attitudes towards sustainable products. The last antecedent, which is known as the perceived behavioral control, is defined as the perceived ease or difficulty to perform a particular behavior (Ajzen, 2002) and specifies constraints or barriers which might hinder consumers' sustainable buying intention (Moser, 2016).

From a general point of view, attitude, intention, perception of behavioral control, and subjective norms each reveal an

aspect of the behavior which can serve as a point of attack in attempts to change this behavior. The exact form of the relations of these antecedents is still uncertain (Ajzen, 1991) as implementing sustainable purchasing does not just easily occur (Moser, 2016).

TPB forms the main theory of this dissertation as it is one of the most established attitudinal theories incorporating measures of intention and behavior (Ajzen, 1991). The attitude-behavior gap, however, requires a more holistic approach, considering the complexity of the determinants hindering pro-environmental intention (Joshi & Rahman, 2015). This thesis takes the factors attitude and subjective norms into account and extends it with specific additional factors since perceived behavioral control demonstrates the importance of individual and situational constraints (Moser, 2016). Therefore, the factors of Ajzen (1991) are extended with additional factors in order to obtain comprehensive results on young consumers’ intention in purchasing sustainable fashion clothes. Individual factors are internal components (Hirsch & Terlau, 2015) that affect decision-making such as knowledge and trust (Joshi & Rahman, 2015; Hirsch & Terlau, 2015; Zheng & Chi, 2015; Hassan et al., 2016; Braga Junior et al., 2019) whereas situational factors are external influences that a consumer cannot control, but impact the attitude-behavior relation, e.g. financial health (Chang, 2011; Joshi & Rahman, 2015) as well as the ability to carry out the intended behavior (Ajzen, 1991). These factors could negatively influence the young consumer’s sustainable purchasing intentions (Ajzen, 1991).

When comparing a wide range of previous literature on individual factors, knowledge is one of the most studied determinants in the attitude-behavior context (Joshi & Rahman, 2015). Environmental knowledge is defined as a generalized knowledge base that is based on the facts, concepts and the relationship between the natural environment and its major ecosystems (Kumar et al., 2017). This factor represents the know-how of individuals about

the environment and the results of their actions on the environment (Pagiaslis & Krontalis, 2014). Next to knowledge, trust is also considered to be one of the main preserved variables (Braga Junior et al., 2019). Trust is defined as the belief or expectation in relation to environmental practices (Joshi & Rahman, 2015). It is crucial to determine if lack of trust influences consumer attitudes towards sustainable consumption, especially given the occurrence of greenwashing. Greenwashing means that some products are promoted as sustainable while they are not (Braga Junior et al., 2019). Sustainable products differentiate themselves with packaging and/or environmental certification from conventional products (Braga Junior et al., 2019). These products might look to have the same features of a sustainable item but are truly far away from reality (Braga Junior et al., 2019). Hence, the lack of consumer trust acts as a barrier towards sustainable purchase intention. Last but not least, a study on sustainable purchase behavior by Dabija & Bejan, (2018) stated that although participants are driven by sustainability and eco-consciousness, they would nonetheless favor the price of unsustainable clothing over ethicality. It is found that fashion consumers are not always willing to make personal sacrifices such as paying a higher price, when it comes to final purchase decisions (Chang & Wong, 2012). Price is said to provide a barrier for consumers to engage in sustainable purchase behavior, and it has been consistently proven that price has a negative effect on sustainable purchase intention and behavior (Vermeir & Verbeke, 2006). To gain a deeper understanding of quantitative effects of specific barriers, the present study incorporates above explained specific antecedents on which hypotheses are formed and presented in the following chapter in order to acquire a real grasp of the consumers purchase intention.

3. Hypotheses

______________________________________________________________________ The purpose of this chapter is to present the developed hypotheses that serve as the backbone of this dissertation, including the conceptual framework which is drawn based on theory.

______________________________________________________________________

3.1 Hypotheses development

As previously discussed, this dissertation focuses on TPB in relation to the attitude-behavior relationship. The factors of the TPB model are further extended with additional factors in order to best explain the constraints of intention in relation to the attitude-behavior relationship in sustainable clothing. A broad range of literature has been investigated and compared for identifying and selecting the most emerging attributes that are considered as key determinants for sustainable consumption intention. According to the foregoing literature studies, attitudes, subjective norms, trust, environmental knowledge and price are dominant influencing factors of sustainable consumption (Chang, 2011; Joshi & Rahman, 2015; Zheng & Chi, 2015; Hirsch & Terlau, 2015; Hassan et al., 2016; Sreen et al., 2018; Braga Junior et al., 2019). These antecedents can either act as barriers (minimizing) or enablers (maintaining) of the attitude-behavior gap (Zralek, 2017) and are highlighted in the current study to analyze the impact of these factors on consumers’ sustainable purchase intention with the goal to recognize main barriers.

3.2 Attitude

On the basis of theoretical evidence, attitude is a significant predictor of purchase intention (Ajzen, 1991; Hirsch & Terlau, 2015; Johnstone & Tan, 2015; Wiederhold & Martinez, 2018; Al Mamun et al., 2018; Sreen et al., 2018; Jacobs et al., 2018). Attitude is described as the psychological emotion path through consumers evaluations and, if positive, intentions are positively affected (Paul et al., 2016). It can thus be argued that mindsets of consumers have to change first to reach a pro sustainable attitude (Ajzen, 1991). Within the studied context, a high attitude toward sustainable consumption and attitude toward environmental concerns are centralized. Attitude toward sustainable product consumption refer to a consumer’s cognitive evaluation (Joshi & Rahman, 2016), and includes the level of judgement to whether a behavior under consideration is favorable or unfavorable (Ajzen, 1991; Paul et al., 2016; Al Mamun et al., 2018). Attitude toward environmental concerns, on the other hand, is specified

as the degree to individuals' awareness of environmental issues and their efforts to solve them (Paul et al., 2016). Also, it can refer to the willingness to contribute personally to seek for solutions (Paul et al., 2016).

Prior studies support the claim that a significant and positive attitude regarding environmental concerns and sustainable consumption influences intention positively (Ajzen, 1991; Chang, 2011; Paul et al., 2016; Moser, 2016; Sreen et al., 2018; Al Mamun et al., 2018). In the context of sustainable fashion, positive attitudes on sustainable clothes also enhance the sustainable consumption (Zheng & Chi, 2015; Jacobs et al., 2018). Literature also contended that consumers are more willing to learn about environmentally friendly products when they hold positive attitudes toward these products (Paul et al., 2016; Sharma and Dayal, 2016).

This hypothesis is based on the foundational idea that when consumers hold positive attitudes of sustainable purchasing, it turned out that they had a higher intention to consume sustainable products (Kim & Chung, 2011). The above-mentioned studies emphasize how attitude toward environmental concerns and sustainable consumption in different contexts impact purchase intention of consumers and have therefore developed a similar hypothesis (Joshi & Rahman, 2016; Sreen et al., 2018; Al Mamun et al., 2018). Thus, this research naturally assumes a positive attitude toward both the environment and sustainable consumption has a positive effect on sustainable purchase intention of clothes. To examine whether consumers indeed have positive attitudes, this predictor is included for hypotheses testing to confirm the existence of the attitude-behavior gap.

H1: A positive attitude toward environmental concerns and sustainable clothing consumption positively impacts sustainable purchase intention

3.3 Subjective norms

The TPB theoretical framework shows that alongside attitude, subjective norms are also identified to be one of the key drivers behind purchase intention and behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Joshi & Rahman; 2016; Sreen et al., 2018; White et al., 2019). Subjective norms refer to the perceived social pressure to perform or not perform a particular behavior (Ajzen, 1991). If consumers have positive subjective norms towards a given behavior, then the more likely intentions are positive (Paul et al., 2016).

As a result of deeply rooted herd instincts (Hirsch & Terlau, 2015) and fashionability being a symbol of social identity (McNeill & Venter, 2019), social groups such as family, friends,

colleagues, or business partners can have either enabling or preventing effects on an individual’s purchase decision making (Paul et al., 2016; Sreen et al., 2018). In case of uncertainty about a particular consumption behavior, consumers might seek advice from social groups (Sreen et al., 2018). Social groups provide vital social and emotional support as people usually tend to adjust their own behaviors to match the perceived behaviors of valued social groups (Sreen et al., 2018). Within the subjective norms’ context, all individuals belong to social groups that have norms on both sustainable consumption behavior and norms regarding environmentally responsible behavior (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1975; Joshi & Rahman, 2016). Consumers are likely to follow these norms in order to receive social approval and acceptance among their social groups. In this sense, this “group effect” may be a predictor of the way consumers would behave towards sustainable purchase intention (Joshi & Rahman, 2016).

Joshi & Rahman (2016) have also found that close circles like parents may be considered role models for observational learning. Close circles are a reliable source of information with respect to sustainable products (Joshi & Rahman, 2016). Taking this into account together with the fact that consumers are mainly loyal to their closest circle (Joshi & Rahman, 2016; Sreen et al., 2018), it can be assumed that consumers might be influenced by their environment and thus can impact consumers' sustainable purchase decision-making process. Scientific papers found that social pressure has a potential direct and positive influence on the intention of consumers (Ajzen, 1991; Joshi & Rahman, 2016; Sreen et al., 2018). In the context of sustainable fashion, consumers' subjective norms also positively affect their intentions to purchase sustainable clothes (Zheng & Chi, 2015). Given the importance of subjective norms on intention, the current research takes social pressure into consideration to confirm the effect on the attitude-behavior relation and to gain an in-depth understanding of whether consumers’ purchase intention is influenced when directly confronted with social pressure.

H2: The perceived social pressure toward sustainable clothing consumption positively impacts sustainable purchase intention

3.4 Environmental knowledge

Knowledge regularly appears in literature (Joshi & Rahman 2015) and is defined as the level of information consumers possess about the environment and awareness of the environmental issues (Zheng & Chi, 2015; Goh & Balaji, 2016). Environmental knowledge

is distinguished in two types, namely: objective knowledge and subjective knowledge (Pagiaslis & Krontalis, 2014; Goh & Balaji, 2016). Objective knowledge refers to what consumers actually know about sustainable products whereas subjective knowledge relates to what customers perceive to know about sustainable products (Goh & Balaji, 2016). Consumers rely on both knowledge types during information search and decision making (Goh & Balaji, 2016) which is why this research does not make a distinction in the two. Moreover, Pagiaslis & Krontalis (2014) mention that demographics are significant determinants of environmental knowledge. Especially age is one of the important demographics to measure knowledge. An explanation for this, is that the older an individual is, generally the more knowledge they have (Pagiaslis & Krontalis, 2014).

Numerous studies are consulted regarding the role of environmental knowledge towards sustainable products (Joshi & Rahman 2015; Zheng & Chi, 2015). Increased environmental knowledge of environmental concerns is said to positively influence consumer purchase intention (Zheng & Chi, 2015; Joshi & Rahman, 2015; Hassan et al., 2016; Kumar et al., 2017; Longo et al., 2017), leading to involvement and engagement in sustainable practices. Zheng & Chi (2015) even argue that a higher level of environmental knowledge is essential for taking responsible actions towards environmental protection. As young consumers are information seekers in nature (Morgan & Birtwistle, 2009), performing information-processing exercises is part of their everyday lives (Longo et al., 2017). The assumption is that consumers are rational decision makers who adopt logic to look up information so as to be able to make efficient ethical decisions (Longo et al., 2017). Herewith, both quality and quantity of information play a significant role in regard to sustainable consumption intentions (Longo et al., 2017).

In contrast, there are also academic papers that show a negative relationship between environmental knowledge and sustainable purchase intention (Chang, 2011; Hirsch & Terlau, 2015; Kumar et al., 2017; Henninger & Singh, 2017; Park & Lin, 2018) as increased environmental knowledge can lead to the perception of information overload and skepticism (Hirsch & Terlau, 2015; Goh & Balaji, 2016; Longo et al., 2017; Kumar et al., 2017). The richness of information could paradoxically hinder consumers’ decision-making processes as a consequence of the information overload and the effort invested in processing the information (Longo et al., 2017; Kumar et al., 2017). Thus, it follows the thought that being exposed to environmental information does not by definition transmit into more sustainable actions where consumers feel overwhelmed by the amount of information related to sustainability (Longo et al., 2017). The overload of information can also lead to skepticism

as consumers might get confused (Longo et al., 2017). Skepticism is defined as the doubt on the authenticity of environmental degradation (Goh & Balaji, 2016; Longo et al., 2017). Widespread societal concerns that companies are presenting ambiguous environmental information has resulted in consumers becoming skeptical about the environmental performance and benefits of sustainable products (Goh & Balaji, 2016).

The increasing societal and environmental public concerns (Paul et al., 2016) shed a light on the importance of researching this relationship. Since empirical obtained results vary on whether the relationship is positive or negative, this factor is incorporated in the study. The majority of the consulted studies about environmental knowledge show that there is a positive and direct relationship between environmental knowledge and intention (Zheng & Chi, 2015; Joshi & Rahman, 2015; Hassan et al., 2016; Kumar et al., 2017; Longo et al., 2017). The authors aim to find out if environmental knowledge indeed positively affects sustainable purchase intentions of consumers in the Netherlands. Therefore, the hypothesis is positively formulated. For the above-mentioned reasons, the authors propose the following hypothesis which has been replicated from the study of Zheng & Chi (2015) on which this thesis also bases the measurements on.

H3: Increased environmental knowledge about fashion hazards positively impacts sustainable purchase intention

3.5 Trust in a brand/product

An often-researched factor within the attitude-behavior context is trust (Joshi & Rahman, 2015). Trust is defined as a belief or expectation about the environmental performance of sustainable products (Joshi & Rahman, 2015). Previous researches show a negative correlation between trust and sustainable consumption (Joshi & Rahman, 2015; Henninger & Singh, 2017; Braga Junior et al., 2019). Hence, trust has become significant in times of “greenwashing” (Braga Junior et al., 2019) that is causing confusion related to the advertisements of brands and the perceived risks when purchasing sustainable items (Braga Junior et al., 2019). Although consumers aim to gain more information on companies’ sustainable claims and their manufacturing processes (Henninger et al., 2017), they face difficulties in defining the validity of an eco-friendly product (Braga Junior et al., 2019). Despite the willingness to acquire information, previous outcomes illustrate that consumers do not spend much time and effort into investigating whether environmental claims are true or not (Carrete et al., 2012). Individuals usually feel anxious about the actual sustainability of

a particular product (Braga Junior et al., 2019) resulting in the mistrust of information and suspicious feelings concerning the true intentions of organizations (Henninger et al., 2017). Research also implies that consumers have the impression that companies act in their self-interest for higher profit margin purposes (Carrete et al., 2012). Lack of trust in organic labeling causes uncertainty and consumers are unconvinced that the organic claim of clothes (Peirson-Smith & Evans, 2017).

Generally speaking, attitudes range from skepticism towards eco-friendly labels to deep conviction that mass media and companies are not being fully genuine in their claims (Carrete et al., 2012). Extant research proposes that skepticism towards greenwashing is derived from false information creating distrust of the credibility of sustainable claims (Longo et al., 2017). Lack of trust in organic labeling causes uncertainty and consumers are unconvinced that the organic claim of clothes (Peirson-Smith & Evans, 2017). This having said, the level of trust in relation to environmental products and sustainable claims appears to be low (Carrete et al., 2012), eventually leading to the lack of trust being a substantial obstacle in sustainable purchases (Henninger & Singh, 2017; Braga Junior et al., 2019). The foregoing is referred to as mistrust in sustainable claims, in which consumers are assumed to be less likely to have sustainable purchasing intentions. As the authors aim to investigate possible barriers, this variable is selected for hypotheses testing in accordance with Braga Junior et al., (2019).

H4: Lack of trust in the sustainable claims of clothes negatively impacts sustainable purchase intention

3.6 Price of the product

Price is one of the factors that is continually brought forward in academic studies. Studies regarding the attitude-behavior gap identified price as one of the key barriers for sustainable consumption (Vermeir & Verbeke, 2006; Chang, 2011; Joshi & Rahman, 2015; Jacobs et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019). Mainly higher prices of sustainable products are considered to be a prevailing barrier (Vermeir and Verbeke, 2006; Chang, 2011; Joshi & Rahman, 2015), especially when consumers are not willing to sacrifice on personal needs (Henninger & Singh, 2017). Consumers, therefore, perceive sustainable products as more expensive in comparison to conventional products (Chang, 2011; Moser, 2016). If consumers have sufficient trust in a brand offering high quality in combination with an affordable price, they are more likely to develop purchase intentions (Wang et al., 2019). Chang (2011) and Moser (2016) display that consumers are willing to pay more (at least 5 percent) for sustainable products provided that the attributes are the same. In the context of sustainable fashion specifically, Jacobs et al.,

(2018) state that price sensitivity hinders sustainable clothing consumption. Additional costs are included in the price such as labor costs and eco-friendly raw materials (Jacobs et al., 2018) yet it has not been identified how much more consumers are willing to pay more for sustainable clothes in terms of percentage.

Naturally, price perception also depends on one’s financial situation and financial health (Chang, 2011; Al Mamun et al., 2018). Prior research has shown that consumers with a high income are more likely to purchase sustainable items and luxury items (Han et al., 2017). In this sense, one driver behind this phenomenon is the fact that price can be perceived either higher or lower based on income (Chang, 2011). Given the fact that the prices of sustainable products are perceived higher compared to conventional counterparts, it can be argued that a relatively lower income is associated with a higher perceived price and thus form a barrier for consumers to engage in sustainable consumption (Chang, 2011). Low price sensitivity of consumers has a positive effect on purchasing sustainably (Joshi & Rahman, 2015). Conversely, high price sensitivity has a negative effect on both intention and behavior (Joshi & Rahman, 2015). Lin & Huang, (2012) also state that price is considered a barrier but is becoming less significant due to price trade-offs and rising environmental awareness. As literature shows that there is a negative relationship between a high perceived price and sustainable purchase intention (Vermeir & Verbeke, 2006; Chang, 2011; Joshi & Rahman, 2015; Jacobs et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019), it is included as a control variable in the analysis of this thesis to make sure no important barrier affecting the attitude-behavior relationship is neglected. This hypothesis is replicated from Chang (2011), following the dominant logic that higher prices act as impeding factors, though slightly adapted to the fashion context.

H5: A high perceived price of sustainable clothes negatively impacts sustainable purchase intention

3.7 Conceptual framework

The hypotheses serve as a backbone of the present study in which the authors test these factors further. The conceptual model is based on the previously discussed influencing factors (attitude, subjective norms, environmental knowledge, trust and price). Therefore, this section is devoted to the development of the conceptual framework and the supporting hypotheses that are established from the current stance in literature. Given the fact that literature already assumes that there is a pro-sustainable attitude among young consumers, it is of great importance to observe what factors influence intention, or to be more specific, what prevents consumers from turning attitudes into behaviors. Therefore, intention can be

seen as the main dependent variable which will have a direct effect on the behavior. The independent variables can have either a positive or negative impact on sustainable purchase intention. A positive impact on sustainable consumption intention and behavior means bridging the gap. Vice versa, a negative impact means strengthening or maintaining the gap. Based on theory, the following conceptual framework is illustrated in Figure II, in which independent and dependent variables are identified:

Independent variables Dependent variable

Attitude Subjective/social norms Knowledge Price Trust

Sustainable purchase intention H1

H2 H3 H4 H5

4. Research methodology

______________________________________________________________________ The purpose of this chapter is to describe the research method used to test the hypotheses based on the literature review. The methodology is divided into the research design, philosophy, approach, purpose, the data collection process and finally yet importantly; limitations of the methodology.

______________________________________________________________________

4.1 Research design

As the purpose of this report is to examine the main barriers behind the attitude-behavior gap, quantitative research helps to investigate key influencing factors by testing pre-defined hypotheses and looking at the impact of selected barriers from an explanatory perspective. Also, the quantitative approach is crucial for this thesis in order to achieve objective measures of the attitude-behavior relationship rather than individual beliefs, motivations and experiences (Saunders et al., 2009). For this reason, this study uses a questionnaire in the form of an online survey to test five hypotheses that are formed in the previous chapter. Questionnaire-based surveys are found to be an effective method to measure hypothesized relationships in regard to sustainable fashion consumption as prior TPB-based studies made use of this method. Subsequently, assessing intention is useful with large samples. The sample size of this thesis is (n=221), which is why quantitative research is the most appropriate strategy for this type of research as well (Saunders et al., 2009). With a sample of more than 100, it can be concluded that there is normalization of the data, which ensures consistency (Bryman & Bell, 2011).

4.2 Research philosophy

The research philosophy forms the research design, which indicates how knowledge is developed and how literature and observations are connected with each other (Blumberg et al., 2011). Researcher Easterby-Smith (2015) describes four types of ontologies: realism, internal realism, relativism and nominalism. The ontological position in this study is realism. In contrast to other ontologies, the realism ontology assumes that there is one single truth, facts exist and can be revealed. In this case, a large sample size survey measures the attitude-behavior gap, which already exists according to literature, by obtaining straight facts on main barriers instead of in-depth opinions. What further strengthens the realism perspective is that this research is testing already existing information gained from the theory as the findings of

this thesis in the following chapter either confirm or reject the assumptions that are made in the literature review. In this research context, there is generally more emphasis on theory-building rather than on direct engagement to get insights on underlying motivations (Easterby-Smith, 2015)

The epistemology is a part of research philosophy and is categorized into two contrasting views of how research can be conducted: positivism and social constructionism. According to (Easterby-Smith, 2015), there is a clear correlation between epistemology and ontology, in which positivism fits realist ontology. The epistemology is positivism in this study. Blumberg et al., (2011) believes that knowledge is developed by studying the social reality within objective realities. Positivist epistemology also fits data derived from statistics and factual knowledge (Saunders et al., 2009), which is the case in this present research where surveys are conducted and spread through social media channels among a large number of participants to obtain statistical data. Lastly, the authors are examining the research from an objective point of view.

4.3 Research approach

Moving to the research approach, Saunders (2012) differentiates two types of research approaches: inductive and deductive. In a deductive approach, theory or hypotheses are based on prevailing literatures which form the whole construct of data collection. Therefore, the deductive approach is applied in this research as this reasoning is generally associated with quantitative research and includes hypotheses development (Saunders, 2012). Particularly in a positivism approach, the relationship between a theory and a research can be revealed and the reality can be objectively observed. This study is focusing on sustainable clothing consumption and the barriers that influence the purchase intention of fashion consumers. From the hypotheses that are developed in the previous chapter, outcomes result in a “confirmation” or “disconfirmation” of the proposed hypotheses. In total, five hypotheses are presented and tested in the remainder of this thesis. The hypotheses testing examines an understanding which barrier(s) influence the intention of consumers to purchase sustainable clothing and enables the authors to answer the main question.

4.4 Research purpose

The purpose of a research can be exploratory, descriptive or explanatory (Saunders et al., 2009). Explanatory or causal research is quantitative in nature and examines an occurrence that can be a situation or a problem in order to identify the relationship between independent

and dependent variables. The independent variable is what one changes or what can change, while the dependent variable is what changes because of that. Further, the explanatory purpose focuses on cause and effect determination (Saunders et al., 2009). The factors (attitude, subjective norms, environmental knowledge, trust and price) are the “cause” of (not) having sustainable buying intentions (dependent variable), this can be seen as the “effect”. One could therefore argue that the nature of this research is explanatory as the aim of this thesis is to identify the direct effects of the selected independent variables on the purchase intention. By explaining the attitude-behavior relation in a detailed manner, the study follows up on an already existing theory which is the attitude-behavior gap. This research is not used to provide conclusive evidence and new theory but instead seeks to extend the attitude-behavior gap by gaining an in-depth understanding of the constraints and behaviors of a certain group of people, in this case Dutch young consumers.

4.5 Data collection

The authors decided to conduct a self-completion (also known as self-administered) web-based survey for primary data collection. By using self-completion questionnaires, the respondents record their own responses on an online platform, in this case Qualtrics. Self-administered questionnaires bring along many advantages. They are cheap and quick to administer, there is an absence of interviewer effects, no interviewer variability and more importantly, it is convenient for respondents (Bryman & Bell 2011). A web-based survey, also known as an online survey, is a survey that is conducted on the internet (Easterby-Smith, 2015). By the use of online surveys, a large audience can be reached to obtain a high level of general capability through the collection of data. The questionnaires are shared via different Facebook groups (Fashion Institute of Amsterdam and Survey Exchange Public Groups), Instagram and e-mail and are asked to send forward, which broadens the reach to get the most respondents in the same age category and within the same country. The aim was to interact with young consumers in the environment of the authors and (close) networks in the Netherlands. Usually people in this target group are students or (young) professionals. Furthermore, internet-based questionnaires make the customization of individual responses easier. There are other advantages attached to the interactivity of web technologies such as pop-up instructions that can explain parts of the web survey that are more difficult to understand. The authors have the possibility to detect error-checking of answers to ensure that people respond consistently throughout as well. Next to that, the dependent and independent variables within this research can also be efficiently analyzed by using a survey

(Easterby-Smith, 2015). It is often easier to find statistically significant results with surveys compared to other data gathering approaches (Easterby-Smith, 2015). The obtained results are saved directly in an online database for further statistical analysis purposes.

4.6 Sampling procedure

Convenience sampling is applied in this study. This type of sampling is part of a non- probability sampling design (Easterby-Smith, 2015). The selected sampling method enables the researchers to distribute the survey in a convenient way throughout social media, thus receiving answers in a short duration of time. Next to convenience sampling, the snowball sampling method is applied as well. Personal and professional networks that meet the requirements are asked to invite other participants for reaching a larger sample size and ensure external validity. To increase the external validity, the sample is heterogeneous. In addition, the data collection would only take place once, which reduces the external validity. In order to receive truthful responses, ethical considerations are secured in order to avoid deception about the nature of the research.

4.7 Survey construction

In respect of the constructs, mainly existing validated constructs are used from previous studies. These constructs are measured through multi-item scales which are adopted from previously used survey instruments in the literature to assure validity and reliability. The questionnaire is presented with the same questions in an identical format, to all participants, in both the desktop and mobile version. The survey (see Appendix I) is developed with the online program Qualtrics and consists of 53 sub-statements spread among 22 main questions in total. To eliminate semi-finished results, every question has to be completed in order to move on to the next. The questions are based on the influencing factors of the attitude-behavior gap identified in the theoretical framework. Moreover, the language of the questionnaire is English. English is relatively easy for a native Dutch speaker, especially within the age-category selected. In the Netherlands, the Dutch speaking community is immersed in the English-speaking culture from very early on. Therefore, it is provided that young consumers in the Netherlands possess sufficient English proficiency.

The survey consists of two parts. The first part includes general demographic questions such as sex, age, education, origin, occupation and income to gain a better understanding of the consumer’s profile as to exclude people that are not eligible for this research. This is essential to properly analyze the data as well as to check the external validity of the collected data.

These questions are constructed in the form of multiple choice where a maximum of one response can be provided, except for occupation. The reason for this is that a student can also be a worker at the same time, so this question can be answered by multiple answers. Furthermore, questions are asked regarding the purchase behavior of conventional clothing in order to get an impression of the consumption habits. The questions are divided into multiple choice questions and a 5-point Likert Scale with the values 1: “Strongly disagree” to 5: “Strongly Agree”.

The second part of the survey centralizes the factors that could hinder Dutch consumers from buying sustainable clothing. The survey includes close-ended questions and statements composed by disciplines from the aforementioned literature. In order to fit the purpose of observing participant’s intentions towards sustainable clothing consumption, some adopted scales are altered. The following variables that are measured within the questionnaire are: “Attitude Towards Sustainable Consumption” (ATSC), “Attitude Towards Environmental Concerns” (ATEC), “Subjective Norms” (SN), “Environmental Knowledge” (EK), “Trust” (T), “Price” (P) and “Sustainable Purchase Intention” (SPI). The scales are measured on a 5-point Likert scale, unless indicated differently. The values are labelled as (1) “Strongly disagree”, (2) “Disagree”, (3) “Neither disagree nor agree”, (4) “Agree”, (5) “Strongly agree”. Participants had the ability to express how much they agree or disagree with a particular statement in order to allow the respondents to fill in the responses in an effortless and quick way. Moreover, to ensure the same interpretation of the sustainable fashion concept, the definition is presented to the participants in the introduction right before questions about different related constructs are asked. The questionnaire is included in Appendix I and the measurement model is illustrated in Appendix II.

4.8 Measurement instruments of the variables

The measures used in this research are mostly altered from past research (see Table I). The dependent variable in this research is intention as dependent variables represent the factors that the research is trying to predict (Easterby-Smith, 2015). The following influencing factors are assumed to have a direct effect on the sustainable purchase intention: attitude, subjective norms, knowledge, price and trust. These factors are derived from previous literature (Chang, 2011; Joshi & Rahman, 2015; Joshi & Rahman, 2016; Nguyen et al., 2018; Al Mamun et al., 2018; Sreen et al., 2018; Braga Junior et al., 2019) and are defined as independent variables, also known as predictor or control variables (Easterby-Smith, 2015). In particular, measures for the dependent variable in this research include the SPI (Nguyen

et al., 2018) of sustainable produced clothes. ATSC is modified from the items in Al Mamun et al., (2018), ATEC is derived from the studies Joshi & Rahman, (2016) and Sreen et al., (2018), SN is altered from Sreen et al., (2018), T is replicated from Joshi & Rahman (2016), Sreen et al., (2018) and Braga Junior et al., (2019). Finally, yet importantly, P is mainly based on Chang (2011).

Variable Construct measure Items

Attitude (Al Mamun et al., 2018; Joshi & Rahman, 2016; Sreen et al., 2018)

Attitude toward environmental concerns and sustainable consumption

11 5-point Likert scale statements

(1: Strongly disagree – 2: Strongly agree)

Subjective norms (Sreen et al., 2018)

The perceived social pressure to perform or not to perform a certain behavior

4 5-point Likert scale statements

(1: Strongly disagree – 2: Strongly agree)

Environmental knowledge (Zheng & Chi, 2015; Minnaard, 2019)

Level of general knowledge about specific environmental concerns, mostly within the textile industry

8 statements with the options “I know” and “I do not know”

Trust (Joshi & Rahman, 2016; Sreen et al., 2018; Braga Junior et al., 2019)

Level of trust in sustainable claims and sustainable product attributes in relation to fashion

11 5-point Likert scale statements

(1: Strongly disagree – 2: Strongly agree)

Price(Chang, 2011) The price perception of sustainable clothing

5 5-point Likert scale statements (1: Strongly disagree – 2: Strongly agree) Sustainable purchase intention (Nguyen et al., 2018)

The willingness to purchase sustainable clothing resulting from attitudes leading to behaviors

4 5-point Likert scale statements

(1: Strongly disagree – 2: Strongly agree)

1 multiple choice question Table I: Operationalization of the variables