Creating Shared Value in the Insurance Industry – A case

study of factors influencing Shared Value opportunities

in the Swedish insurance industry

BACHELOR THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15 ECTS

AUTHOR: Carlsson, Simon & Hallén, Herman TUTOR: Rumble, Ryan

i

Abstract

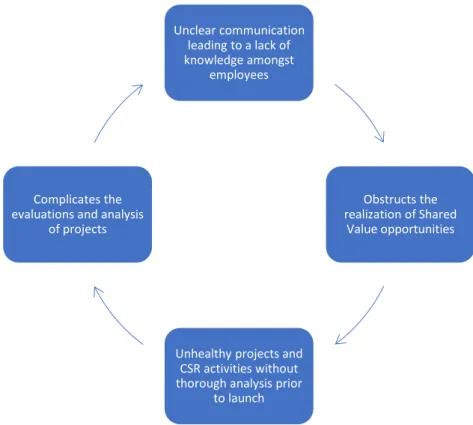

The interest and demand of sustainable actions have alongside with societal development increased over time. It has become crucial for companies in today’s society to show responsibility for the footprints they leave behind as a consequence of operating. A possible course of action could be the implementation of Creating Shared Value – CSV, which encompasses undertakings that result in value creation for both the company itself, and the local environment in which the company operates. Even though companies are expected to contribute to societal issues, there are still no blueprints declaring how to satisfy societal needs, and the challenges accompanied with it. CSV aims to tackle the distances between societal and business goals, however, despite CSV’s acknowledgement in academia, the concept is often criticized for being insufficient in practice. This has led to businesses trying to apply a CSV approach while still undertaking Corporate Social Responsibility – CSR related activities. The mixture of these concepts has made it difficult to explore what factors that affect the process of capturing Shared Value opportunities. This research investigates what factors that influence the process of capturing Shared Value in the Swedish insurance industry. The findings derived from this single company case study suggests that depending on what managerial decision-making approach used in a company affects the rate of success in terms of Creating Shared Value. An unclear communication plan, combined with the continuous confusion between the concepts, seems to increase the uncertainness of why and how different decisions are taken, hindering the process of CSV as well as the understanding of how Shared Value is created. A variety of factors were identified, where three main factors were considered to play a key role in, not only the capturing of Shared Value opportunities but the entire implementation process of the concept. Based on these factors, a model was established, showing how these main factors obstructs the realization of Shared Value opportunities.

Keywords

Creating Shared Value, CSV, Corporate Social Responsibility, CSR, Factors, Implementation Process, Business Value, Insurance Industry, Sweden, Shared Value, Corporate Responsibility, Decision-Making Process

ii

Acknowledgements

We would like to declare our gratitude towards Länsförsäkringar Jönköping, and all the representatives taking their time to make this research possible. A special thanks to Malin Sonnvik, at Länsförsäkringar Jönköping, for your commitment and engagement in terms of coordinating this collaboration with Länsförsäkringar.

Furthermore, we would like to express our gratitude towards our tutor, Ryan Rumble, for always being available to answer questions and delivering feedback during this journey of writing this thesis.

Thank you,

iii

Table of Contents

1

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Problematizing ... 3 1.3 Aim of Study ... 42

Theoretical Framework ... 5

2.1 Corporate Social Responsibility – CSR ... 5

2.1.1 Pursuing CSR ... 6

2.1.2 Criticism towards CSR ... 6

2.2 Creating Shared Value – CSV ... 7

2.2.1 How to Create Shared Value ... 7

2.2.1.1 Reconceiving Products and Markets ... 8

2.2.1.2 Redefining Productivity in the Value Chain ... 8

2.2.1.3 Enabling Local Cluster Development ... 8

2.2.2 Criticism towards CSV ... 8

2.3 Differentiation ... 9

2.4 Managerial Decision-Making ... 9

2.4.1 Levels of Influences ... 10

2.4.2 Rational Choice Theory ... 10

2.4.3 Behavioral Theory of the Firm ... 10

2.4.4 Garbage Can Model of Organizational Choice ... 11

3

Research Design ... 12

3.1 Research Philosophy and Approach ... 12

3.2 Research Method ... 12

3.3 Research Strategy ... 13

3.4 Data Collection... 13

3.5 Sampling ... 14

3.5.1 Sample Limitations ... 15

3.6 Validity and Reliability ... 16

3.7 Data Analysis ... 16

4

Case Study ... 17

5

Analysis ... 19

5.1 Factors Influencing Shared Value Opportunities ... 19

5.1.1 Institutional ... 19

5.1.1.1 Increased Demand of Sustainability from Coming Generations ... 19

5.1.1.2 Increased Demand from Society, Governments and NGO’s ... 20

5.1.1.3 Economic Condition of the Country ... 21

5.1.1.4 Climate Change ... 21

5.1.1.5 Increased Damages within Specific Sectors ... 22

5.1.2 Organizational ... 23 5.1.2.1 Managerial Decision-Making ... 23 5.1.2.2 Stakeholder Management ... 25 5.1.2.3 Allocating Resources ... 26 5.1.2.4 Corporate Structure ... 26 5.1.2.5 Communication Plan ... 27 5.1.3 Individual ... 28 5.1.3.1 Lack of Knowledge ... 28

5.1.3.2 Individual Preferences and Opinions ... 28

iv

7

Conclusion ... 33

7.1 Factors Influencing Investments in CSV ... 33

7.2 Implementing CSV in an Insurance Company ... 33

7.3 Future Research ... 34

References ... 35

1

1

Introduction

In the introduction chapter, the question of issue in this study is described. Both the problematization and motives of this research are addressed and clarified. Furthermore, a problem discussion was included in order to explain the objectives of this paper.

1.1 Background

Businesses have more or less always been subject of debate. As a consequence of this, it has become clear that businesses play a major role in today's society (Grafström, Widell & Göthberg, 2008). The footprints that businesses leave behind in terms of societal and environmental impact, has resulted in an emerging desire to change the way businesses operate in favor of a more sustainable manner. The companies in today's society that refuses to take responsibility for their impacts, will most likely endure critique and sanctions from the public sphere (Schrempf-Stirling, Palazzo & Phillips, 2016).

From a historical perspective, profit maximization has often been associated with business purposes. The economist Milton Friedman developed a theory in 1962 that explains the purpose of business. Friedman argued that the purpose of businesses is to present a satisfactory result in the eyes of the shareholders, the so-called Shareholder Theory (Smith, 2003). The norm of putting the business interest first have changed and it is nowadays essential for the survival of the firm to show, by actions, that the business operates with the aim of not exclusively present a solid financial report (Carroll, 1999; Epstein, 1987). Previously published research emphasizes the importance of operating with respect to external expectations, for the sake of the wellbeing of the company. If not, decreased turn-over, less market shares and/or lost collaborators or employees could be found as a consequence (Sullivan, Haunschild, & Page, 2007; Strachan, Smith & Beedles, 1983).

In 1999, John Elkington published “Cannibals with forks”, which he claims was the start of today's perception of the framework of corporate responsibility (Elkington, 2006). He introduced the concept of the Triple Bottom Line, which meant that all firms should be measured in not only economic but also social and environmental performance. With its introduction, corporations now suddenly received pressure from governments and the society to declare their social and environmental performance as well as impact. This eventually resulted in a remodeling of corporate governance. The firm was no longer responsible for the outcomes of its operation, instead, the directors in the boardroom were the ones held accountable (Elkington, 2006). Elkington further argues that this transformation laid the foundation of Corporate Social Responsibility – CSR, and its framework that has been accepted and developed during the last twenty years. Alongside with societal progress, it is no longer a matter of exclusively being able to deliver the best product or service, but also to be able to manage expectations and pressure originating from the society (Namiki, 1986) According to Jonker & De Witte (2006), companies have, as a way of approaching this arising external pressure, begun to implement aspects of CSR and sustainability as a part of their business organization. It has become normal for businesses to integrate CSR in their everyday activities, often with the aim to facilitate environmental issues (Jonker & De Witte, 2006). Definitions of how to understand CSR efforts and activities for companies have been presented and implemented in legal terms (European Commission, 2011, p. 6) which have led

2

to businesses applying sustainable aspects in their business strategies because they simply have to. The pressure from NGO ‘s and governments in terms of the obligation of investing in sustainability injures the companies due to its ability to foresee the fact that firms are not automatically profitable (Wójcik, 2016). Due to this arising external pressure and the implementation of legal guidance, one could argue that it has resulted in a segmentation rather than uniting the society and businesses.

However, in recent years the concept of Creating Shared Value – CSV, has emerged and made its entrance within scholars and business journals. CSV is according to Porter & Kramer (2011) actions that result in value creation for both the company itself, and the local environment in which the company operates. Despite its recognition in academia, the concept has, more or less, never developed beyond this state (Dembek, Singh & Bhakoo, 2016; Wójcik, 2016). When Porter & Kramer first introduced the concept in 2011, in the Harvard Business Review, they believed that they were on the verge of a new way of capitalism. Porter & Kramer (2011) believed that this would flourish the markets and reunite the business industry with NGO’s and governments by creating value in synergy. Porter & Kramer (2011) further unravel the possibility of businesses receiving beneficial outcome, if acting upon opportunities considered to result in creating value for society and the business. The authors entitled this code of behavior as CSV (Porter & Kramer, 2011). In contrast to CSR, Porter & Kramer (2006) conjecture that CSV is not a response to the social pressure on the shareholder’s responsibility to the society, but a strategy aimed to strengthen the business long-term competitiveness.

There are several theories regarding how a business operates, and why it operates in certain ways. As stated earlier, external pressure is important when talking about the cause of exercising corporate responsibility. When breaking down external pressure, Vashchenko (2017) argues that the motivation behind pursuing CSR, or CSV, related objectives are often seen as a consequence of internal and external underlying factors. These factors are influencing the decision-making process and by that the potential undertakings of the company. Vashchenko (2017) continuous by explaining that the fundamental cause of implementing CSR related actions has often been from a societal behavior point of view. This is argued to be a reaction of what competitors do, also known as Institutional Theory, which basically means that there could be a lack of internal intentions of pursuing CSR since the firms do it exclusively because the competitors do it. This behavior is, according to Vashchenko, based on compelling with social structures, in order to avoid being excluded or to decrease the risk of being seen in a “bad light”. Based on this, the Institutional Theory presents a standardized, psychologic and regulative framework influencing the courses of actions taken in the company (Vashchenko, 2017). Others, including Godos-Díez, Cabeza-García, Alonso-Martínez & Fernández-Gago (2018), claim that CSR is a product of Stakeholder Theory first introduced by Freeman in 1984. The idea means that the firm should include all stakeholders when making a decision. Hence, the inclusion of the social and environmental aspect which later resulted in the concept of CSR. Because of this reason, even though the shareholders’ interest is no longer the one and only priority, the theories of Stakeholder Theory and Institutional Theory combined are affecting the way of managing decisions in a specific company (Campbell, 2007). Both ideas advocate the bearings of external factors in the process of implementing CSR, and by that, CSV activities. Furthermore, from an organizational point

3

of view, there are several decision-making process theories explaining how and why companies are operating in certain ways. These theories emphasize the influence, and the impact, of different factors affecting the decision-making processes (Fulop, Linstead & Clarke, 1999).

1.2 Problematizing

CSR and CSV are both sharing some core elements, CSV can somewhat be seen as a part of the CSR-umbrella term (Wójcik, 2016). Despite its similarities, there are some aspects in which CSV can be considered to be unique. Porter (2010) argues that the main differentiation between the two concepts is the purpose and the financing of the particular activity;

CSR is kind of separate from profit maximization, CSV is integral to profit maximization. In CSR, the impact you can have is limited to your CSR-budget, CSV is about mobilizing the entire budget of the corporation, to impact social issues.

− Porter (2010), CECP

The criticism towards CSV is that these aspects are not enough for the concept to fulfill the requirements for a novel concept. According to several authors, including Crane, Palazzo, Spence & Matten (2014) Dembek et al. (2016) and Wójcik (2016) the differentiation between CSR and CSV concludes that CSV runs short in its uniqueness. Wójcik (2016) refers to this as a “blurry line” separating the two ideas.

Porter & Kramer (2006) argue that activities associated with CSR generally fall short to identify business opportunities, and by that, fail to prioritize those opportunities that would generate the most profitable outcome. This is said to be due to CSR activities often being separated from the business core strategy and practiced only as a consequence of external pressure (Porter & Kramer, 2006). Wójcik (2016) continues by arguing that CSR investments are most likely to coincide with financial profits by simply transferring business profits into societal issues. This indicates that there is a potential trade-off between profit maximization and social responsibility. Rather than making strategic decisions outside of the business strategy, a CSV approach strives to integrate social and environmental aspects in the business and utilizes that process to create economic value (Moore, 2014). Porter (2013) even states that for CSV to function, one key prerequisite is that the opportunity must be internally identified. With that being said, it is important that the motivation behind decisions regarding value creation is internally identified and agreed upon, not as a consequence of external pressure. Shared Value is utilized when a company can identify opportunities that can create both economic and social value, which means that the Shared Value must be company-specific, this is backed up by Porter (2013). This makes it very difficult, if not impossible, to construct a general method or strategy of how to implement CSV in a business. In multiple forums, the lack of CSV in practice is seen as one of its major issues, making it an abstract concept. This makes it difficult for businesses to adapt CSV in their strategy, nor does it contribute to its acknowledgment. The concept has often been criticized for its inability to respect the differences and tensions between social and economic goals. As implied earlier, it could even be the case of faulty interpretation of what CSV really is and because of that reason often confused with CSR. Even though companies are expected to contribute to societal issues, there are still no general blueprints on how to implement or identify CSV opportunities,

4

in any industry. This misinterpretation of the concept has caused businesses trying to apply a CSV approach while still undertaking CSR-related activities (Van Marrewijk, 2003). The mixture of these concepts has made it difficult to explore what factors that actually affect the decision-making process within Shared Value opportunities. Furthermore, this has according to Van Marrewijk (2003) led to the identification of factors that influence the rate of success of a project has not been sufficiently declared. This could be one of the reasons why CSR continues to be the common way of tackling societal and environmental challenges whereas CSV remains a questioned, and by that, an undisclosed concept.

1.3 Aim of Study

The aim of this thesis is to investigate what underlying factors that are influencing and affecting the process of Creating Shared Value in the Swedish insurance industry. This paper will also distinguish CSV from CSR in theory, with the purpose of creating a deeper understanding of the factors influencing Shared Value investments. Furthermore, the study will present related concepts and how they affect investments in Shared Value opportunities.

While most companies have more or less implemented CSR in their business strategy, Shared Value remains a theoretical concept which lacks clarification and distinctive goals for implementation in practice (Dembek et al., 2016). This blurry line between these frameworks as Wójcik (2016) refers to it, contributes to a misunderstanding in these concepts. It could be argued that this misunderstanding and poor conceptualization could be a factor enhancing the implementation of CSV successfully in a business strategy. Therefore, this paper focus on outlining the differences between these frameworks with the aim to make this blurry line clearer. To be able to identify the factors influencing Shared Value Opportunities one must distinguish CSR from CSV. The decision-making processes obtain influences from many sources in three general levels as Aguinis & Glavas (2012) puts it – Institutional, Organizational and Individual. The objective, based on the explanation above, with this study is to determine and categorize with respect to Aguinis & Glavas (2012) three levels, what factors that hinder or ease the process of granting Shared Value opportunities in the Swedish insurance industry. In the insurance industry, the society is the market, meaning that factors impacting society also have a direct impact on the business in terms of costs or profits. Based on this, the insurance industry possesses characteristics that could function as a motivator of why Shared Value should be created, since improving societal issues also creates economic value. With this in mind, the following question was developed, guiding the work throughout the entire process; Research Question: “What Factors Influence Insurance Companies’ Investments in Shared

5

2

Theoretical Framework

To be able to identify the factors affecting Shared Value opportunities one must distinguish CSR from CSV. Because of that reason, the theoretical framework is consisting of concepts and theories, aiming to make this blurry line between CSR and CSV clearer. What follows are definitions and procedures taken in the field of both CSR and CSV, which functions as a way of separating these two concepts apart from one another. Criticism towards the two concepts are also included considering that criticism could motivate, or demotivate, why organizations decide to operate in a certain way.

2.1 Corporate Social Responsibility – CSR

Corporate Social Responsibility began in the mid-1900s and has ever since been a matter of discussion in multiple kinds of literatures (Carroll, 1999). Researchers have for a long period of time tried to construct performance measurement of CSR and developed alternative ideas along the lines of sustainability. Business ethics, corporate behavior and civic commitment are all attempts to determine the effects of CSR (Byers, Slack & Parent, 2012). Corporate Social Responsibility is known as the courses of actions taken with the aim of embracing commitment and engagement through business activities, and advocates the positive by-products of its undertakings, that positively affect the community (Tai & Chuang, 2014). The normalization

of businesses establishing CSR related objectives as a part of their business strategy is a result of the increasingly common belief of CSR’s ability to Create Shared Value by competing shareholder´s interests with a deeper purpose that exceeds the belief of profit maximization (Bansal & DesJardine, 2014). Even though CSR, in later days, has received a vast amount of attention it is not a new phenomenon. In conjunction with observed issues such as deforestation, global warming and the exploitation of child labor CSR has been implemented with the motivation of businesses ability to affect the society and the environment around them (Carroll, 1999). The reaction to this, is that the theory of CSR has become very broad with a variety of definitions and boundary-free regulations which in turn has led to the terminology connected to CSR being many. It is not uncommon that aspects such as, local communities, environment and accountability often are mentioned when discussing CSR. This has resulted in CSR becoming an umbrella term used to describe the process of repaying the society and undertake responsibility in terms of environmental and social issues (Frynas & Yamahaki, 2016)

As previously mentioned, CSR has emerged and become a broad aspect which in turn has led to a variety of definitions. It has become a well-known term, with several meanings. The conceptualization of CSR varies throughout firms and individuals. This has according to Van Marrewijk (2003) led to companies interpreting CSR in a way that fits the company’s specific interests. Due to this reason, the activities or decisions taken in a company, in the field of CSR, can be very dissimilar and diversative. Moreover, de Jong & van der Meer (2017) present three divisions of CSR that are viewed and managed differently. Corporate Philanthropy is characterized as simply transferring money from the company to the society, as charity, with no expectations of receiving beneficial outcomes. Sponsor Philanthropy is when the company aims to make a certain association with a brand for a specific cause. Cause Related Philanthropy is a more deeply rooted behavior, where the company strives to combine the motives of the business with social causes (de Jong & van der Meer, 2017). Moreover, Hopkins (2012) discusses the possibilities of seeing a development in a country as a whole, through

6

organizations engagement in corporate responsibility. However, the progress of businesses’ CSR is not something that could be seen as a dramatic change. CSR is an ongoing progression within organizations’, where all components of the organization must work in synergy, shareholders as well as employees (Hazlett, McAdam, Sohal, Castka & Balzarova, 2007).As a consequence of this, CSR’s actions or maneuvers, which by-products are considered to be positive for both the environment and the public sphere, are likely to be beneficial for the business itself (McWilliams & Siegel, 2001)

2.1.1 Pursuing CSR

The fundamental belief is that the organization must be truly compassionate when engaging in CSR, not exclusively doing it to look good. The result of implementing CSR and the process of doing so, is argued to be mediated by factors that dents the managerial perception of these actions (de Jong & van der Meer, 2017). This is something that is supported by Ferrero-Ferrero, Fernández-Izquierdo & Muñoz-Torres (2012), research regarding a company’s CSR-orientation. A company’s standpoint regarding CSR, influences the actions taken by a company as well as the success of the company’s different projects (Ferrero-Ferrero et al., 2012). It is a matter of corporate governance i.e. the business established objectives, that affect the orientation (Godos-Díez et al., 2018). Furthermore, Reinhardt, Stavins & Vietor (2008) continue by arguing that a business’ participation in CSR-related activities is depending on the investor’s affection to do so. With the condition that investors are prepared to invest in projects characterized as corporate responsibility, the business is going to be able to pursue such opportunities. The state of the investor’s willingness is a subject of different circumstances, such as the current economic situation of the company, if the stakes are public or held privately or the condition of the market in which the company operates within (Reinhardt et al., 2008). Because of this reason, stakeholders possess an influential effect on CSR programs.

2.1.2 Criticism towards CSR

Due to the reason of CSR becoming a concept consisting of different definitions and views, a general definition is yet to be recognized (Van Marrewijk, 2003). Ahen & Zettinig (2015) argues that as a consequence of all these definitions, the concept has lost its significance (Ahen & Zettinig, 2015). Wójcik (2016), continues by arguing that CSR activities are only a way for businesses to market themselves and the link between CSR and the business’ actual objectives is absent (Wójcik, 2016). Moreover, the businesses in today’s society could use CSR to shield themselves from sanctions from the society, so called Greenwashing. This means that by presenting an appearance of acting upon societal issues, businesses could hide the fact that the business actually affects the society in a negative way (Ahen & Zettinig, 2015).E.g. An airline company that portrays themselves to make contributions to environmental goals could use that as a shield for the environmental deterioration that follows as a result of operating. The argumentation behind the statement of CSR being a marketing channel is based on the belief that the implementation of CSR is a result of dealing with societal pressure (Wójcik, 2016). By operating a business while experiencing pressure from the society, the business could fail to identify the problems where the organization could make the most difference (Porter & Kramer, 2011). The authors further criticize CSR by claiming that the concept is separated from profit maximization, meaning there is a trade-off between social and economic performance. Porter

7

and Kramer even charge that in many cases, CSR is a matter of charity, i.e. Corporate Philanthropy.

2.2 Creating Shared Value – CSV

“Creating Shared Value” is a theoretical concept that refers to when society and a business creates both societal and economic value in synergy with one another. Porter & Kramer (2011, p. 66) define it as; “policies and operating practices that enhance the competitiveness of a

company while simultaneously advancing the economic and social conditions in the communities in which they operate”. The concept itself was first introduced by Porter & Kramer in (2006). They had during their exploratory studies at Nestlé pursued the exploration of the concept Shared Value. They found that Shared Value opportunities did exist, and its strategy could be implemented successfully (Crane et al., 2014). With the success at Nestlé, Shared Value was elaborated further and published by Porter & Kramer in the Harvard Business Review (2011), as The Big Idea, this was the actual introduction of “Shared Value” as a framework. It was explained as a new way of capitalism with the purpose of restoring the legitimacy of a business. With further substance than its previous introduction, the concept now received greater attention. From this point, CSV has been embraced and criticized to a wide extent by scholars and business journals (Crane et al., 2014; Strand, Freeman & Hockerts, 2015; Dembek et al., 2016; Wójcik, 2016).

In contrary to CSR, which in some cases is argued to be an expenditure (Wójcik, 2016), CSV is about identifying business opportunities that create business value while satisfying societal needs. Porter (2013) exemplifies this by referring to personnel safety. Businesses with the “Conventional Wisdom”, as he calls it, categorizes this as a cost. The enlightened firms with “The New Thinking” see this as an opportunity, investing in the wellbeing and safety of the employees will lower costs in terms of sickness leave and improve the overall quality of production, in other words, Shared Value has been created. The purpose of CSV is to encourage businesses to work in the direction of the society, in synergy creating value which in this case is defined as benefits relative to cost (Porter & Kramer, 2011). Porter (2013) explains that CSV is a consequence of businesses’ failure of solving societal issues. Crane et al. (2014) claim that Porter and Kramer assume, with CSV, that compliance between companies and governments is taken for granted. Without it, CSV would not be functioning. As a contradiction to this, Porter & Kramer (2011) motivates CSV by arguing that capitalism sometimes suffers from a lack of ethics and morals, i.e. ignores society meaning that they also ignore governments. To Create Shared Value, the opportunities must be internally identified, which means that firms are proactive, searching for Shared Value opportunities where the business is operating (Porter & Kramer, 2011). The “Conventional Wisdom” as referred to earlier, indicates that there is a trade-off between economic and social performance, however, according to Porter (2013) the reality is the opposite. Where CSV is a part of the solution, addressing societal goals and needs, Porter implies that there is no trade-off in pursuing Shared Value opportunities.

2.2.1 How to Create Shared Value

While Porter & Kramer (2011) explains the concept in its core and presents case studies which has successfully implemented the framework in their business strategy, there are still no blueprints of how to implement the framework successfully in a business. This could be due to

8

the fact that CSV opportunities must be internally identified, meaning that each firm must have an individual strategy for Creating Shared Value (Porter & Kramer, 2011). Nevertheless, the lack of methods or blueprints of implementation is one of the major aspects in which the framework has received criticism. This shortcoming complicates how businesses could implement CSV in their strategies and how they identify these opportunities in order to Create Shared Value. Porter & Kramer (2011) explained in their presentation of the concept in 2011 that a firm can Create Shared Value in three ways, Reconceiving Products and Markets,

Redefining Productivity in the Value Chain and Enabling Local Cluster Development. 2.2.1.1 Reconceiving Products and Markets

Porter & Kramer (2011) claim that by reconceiving products and markets one can Create Shared Value. They mean that firms have not prioritized the “customers’ customers” when developing new products and markets. The demand for products and services that meet societal needs, in which they claim is the “greatest unmet needs in the global economy” (Porter & Kramer, 2011, p. 7), is rapidly growing. Firms are now offering more sustainable alternatives benefitting society. By seizing these opportunities, such as Wells Fargo’s products aiding customers to budget, manage credit and payment plans, businesses can Create Shared Value (Porter & Kramer, 2011).

2.2.1.2 Redefining Productivity in the Value Chain

The value chain of a firm is affected by societal issues. Natural resources, water usage, the health and safety of workers and gender equality are factors affecting the quality of the value chain and its efficiency (Porter, 2013). Societal problems as Porter & Kramer (2011) calls it, could in many cases result in economic costs for the firm. Firms should, therefore, invest in and improve societal circumstances, resulting in lower costs for the firm while working conditions are improved. E.g. Nestlé, by educating their farmers in developing countries and providing them with better tools and chemicals they increased a higher yield of the harvest and therefore increased the profit, by doing good, i.e. Redefining Productivity in the Value Chain (Porter & Kramer, 2011).

2.2.1.3 Enabling Local Cluster Development

To be successful, it is important for firms that they are surrounded by other supporting companies and a well-developed infrastructure. Local Clusters – geographic concentration of firms, education and institutions sharing fields in which they operate, boosts the productivity innovation and competitiveness (Porter & Kramer, 2011). Firms can Create Shared Value by forming and developing these clusters, improving the firm’s productivity while addressing the challenges faced in the surrounding context. Porter and Kramer further claim that improved education and supply of resources increases a firm’s success.

2.2.2 Criticism towards CSV

The concept CSV has, since its first appearance in 2006, endured heavy criticism from several directions. Some key flaws in which the concept is most criticized is its tendency to ignore tensions between social and economic goals (Bergengren & Präauer, 2016; Crane et al., 2014). Its’ similarity to CSR, Blended Value, Social Innovation, Corporate Philanthropy etc., has often been argued to be a shortcoming of the concept, resulting in its labeling of “Strategic CSR” (Motilewa, Worlu, Agboola & Gberevbie, 2016). Porter and Kramer responds to this by

9

adopting, as Crane et al. (2014) puts it, “a largely unrecognizable caricature” (Crane et al., 2014, p. 134) view of CSR, aiming to reinforce the border between the two concepts, CSR and CSV. Nevertheless, this is a recurring subject of criticism, CSV is often viewed to be unoriginal and not a novel concept (Crane et al., 2014; Dembek et al., 2016) which, with addition to the shortcomings of the concept, results in a gap of knowledge regarding what challenges a company could face if intending to adopt the concept CSV. More specifically, Crane et al. (2014) claims that Porter and Kramer’s framework does not present sufficient literature separating CSV from Stakeholder Theory. Again, Crane et al. (2014) points out that to neglect the tensions between societal and corporate goals and its naïve conception of business compliance wipes out any potential of practical conceptualization.

2.3 Differentiation

The idea of Shared Value was derived from the sustainability and corporate governance debate held last decades, none the less, the concept of CSR. Shared Value has been heavily criticized by various scholars and forums e.g. Crane et al. (2014) and Wójcik (2016) for being too similar to CSR. It has often been viewed as not being an original, or novel, concept. However, unlike CSR, Shared Value is identified by being generated within the company, aiming for profitable investments rather than reacting to external pressure from other sources such as NGO’s and Governments in terms of corporate responsibility (Porter & Kramer, 2011). Karnani (2011) claims that CSR is occasionally argued to be too abstract for application in a business strategy, Porter & Kramer (2011) further review that the concept itself focus on how business value can be transferred into society and therefore is separate from profit maximization. CSV, on the other hand, means new business opportunities and creating value by benefitting both parties, business and society. It is a concept where businesses are working in synergy with society to create value. The conception of corporation’s role in society varies in these frameworks, CSR is, according to Porter & Kramer (2011), separated from profit maximization, CSR actions are taken because of guilt, rising from the negative impacts firms induce on society. CSV, as presented by Porter & Kramer (2011), introduces a new way of capitalism, that supersedes this issue, focusing on profit maximization while simultaneously satisfying societal needs.

2.4 Managerial Decision-Making

The decision-making process in a company is according to Bauer, Morrison & Callister (1996) a process facing several parameters when managing decisions in a company. As Aguinis & Glavas (2012) argued, there are three main levels of influences affecting the decision-making processes; Institutional, Organizational and Individual. This could be applied in the process of undertaking CSV activities. However, to understand the role, and power, of each level of influence it is important to investigate what decision-making process is used when managing CSV activities. This could ease the process of identifying factors since different decision-making processes are influenced by different factors and parameters. Due to this reason, in order to make the process of identifying and understanding what factors affect insurance companies’ investments in CSV easier, it is favorable to first identify what decision-making process that is being used. Because of this, this section will focus on three common processes of decision-making. The motivation behind presenting the following processes is to cover separate areas in decision-making theory with the aim to explain decision-making behavior.

10

2.4.1 Levels of Influences

As stated earlier, Aguinis & Glavas (2012) argues that there exist three different levels of influences in which undertakings in the field of CSR could be categorized into (Aguinis & Glavas, 2012). The Institutional level refers to common standards, rules or regulations that are present in the environment that the company operates within. It also includes influences from third parties, such as the society. The Organizational level emphasizes factors such as firm size, how the company is structured and/or how the company is managed, i.e. established procedures and ways of operating. The Individual level on the other hand, addresses decision-makers’, or employees’, values or beliefs as a foundation of factors influencing the decision-making process (Godos-Díez et al., 2018).

2.4.2 Rational Choice Theory

Fulop et al. (1999) states that a fundamental assumption for Rational Choice Theory is that all parties involved have agreed upon and understood the process and rules used in the decision-making process. The theory suggests that there is only “one best way”, always, aiming to identify this optimal decision through careful evaluation. Zey (1998) refers to this evaluation process and explains that what the individuals evaluate is cost and gain, i.e. the profit generated by pursuing a specific decision. With a desire to reach individual goals and ends, the Rational Choice Theory is based on a hierarchy of personal preferences. The option that will get selected, as Fulop et al. (1999) referred to as optimal, is the decision that will result in the highest net profit for the individual deciding (Zey, 1998). Furthermore, Rational Choice Theory as a framework, neglect what these goals and ends consist of, meaning that the objective is not economic per se, even if that is often the assumption and actual case. To identify this ”one best way”, expertise in the concerned area and adequate information is key. However, the complex reality with its many different environments in terms of time, cost and uncertainty are in some cases enhancing the implementation of the Rational Choice Theory, i.e. the measurability of CSR actions (Fulop et al., 1999).

2.4.3 Behavioral Theory of the Firm

In 1963, Cyert & Marsh published A behavioral theory of the firm – BTF, this introduced a framework containing several theories aiming to explain behavior and decision-making within organizations. It has become a pillar in Organizational Theory (Argote, 2015) and is often considered as a predecessor in applying the perspective of bounded rationality into organizational behavior (Argote & Greve, 2007). Argote (2015) further reviews that the book presents a theory explaining the underlying mechanism in organizations and their decision-making processes. Todeva (2007) argues that BTF suggests that decisions could be of both rational and non-rational nature. As a conjecture to Rational Choice Theory which aims to identify the one and only best way, always. This theory or framework grasps the complexity of organizations and therefore the complexity of decision-making.

One of the theories within the Behavioral Theory addresses the consequences of different participants’ attention. According to Scott (1998), a firm’s behavior is a product of the actions of its employees. The author argues that depending on where decision-makers address their attention, the firm is going to affect the organizations’ operation – Attention-based Theory (Scott, 1998). Scott continues by explaining organizational attention as a network of various processes that absorbs commitment. A crucial aspect of explaining why decisions are taken in

11

a company is, according to Scott,to realize the effect the organization have on decision-makers. The organizations’ economic and social construction initiate employees to engage in “discrete processes”, which represents the foundation of the organizational behavior. Based on this, the main argumentation behind business behavior is consists of a sequence of different attentional processes. The answer to the question of why an organization is operating in a certain way could be explained as the outcome of what decision-makers are allocating their attention towards. Why the decision-makers are acting in a certain way is the result of aspects such as regulations at the firm, means available and different partnerships which all transmit decision-makers into different proceedings (Ocasio, 1997).

2.4.4 Garbage Can Model of Organizational Choice

Cohen, March & Olsen (1972) presented a model that explains a process in decision-making which they called the “Garbage Can Model of Organizational Choice”. This process is characterized by the absence of no clear criteria, unknown factors and influences and when solutions are not compelling with the original problem. The model suggests that all issues faced by an organization could serve as a problem or solution depending on the circumstances. Therefore, these issues are dumped into a “garbage can”. According to Fulop et al. (1999), this means that when it suits the company, they can merge two issues. Hoping that some problems may serve as solutions to another problem without evaluating an optimal solution to that specific problem. That is why, this model is sometimes called “Circumstantial Rationality”, meaning that it depends on what issues the organization currently face of what solutions that may be addressed to certain problems (Fulop et al., 1999). Compared to the Rational Choice Theory, this model is not based on careful evaluation to find an optimal “best way” solution. You simply make the best of the situation by pursuing the solution that you have at that given time, in your garbage can. Again, the solution is therefore dependent on the circumstances at that time.

12

3

Research Design

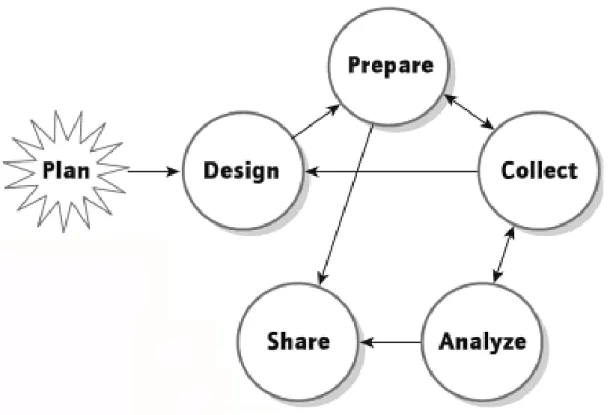

In order to present sufficient understanding and knowledge for discovering what factors that influence insurance companies in their pursuit of Shared Value, it was decided upon to carry out an exploratory, qualitative, single case study. This research is conducted from an interpretivist perspective, a philosophy that supports the inductive oriented research (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Furthermore, The Case Study Research: Design and Methods (Yin, 2009) has been used as guidance during this study to certify that the case study would be carried out in a trustworthy manner. Yin argues that when writing a thesis, it is important to set a research paradigm early in the process. This serves as guidance for the authors during the research process. A step-by-step process presented by Yin (2009) was used during the study, (See Figure A1 in Appendix A). In the following section, the data collection and its methods will be presented and argued for, furthermore, the research design will be outlined.

3.1 Research Philosophy and Approach

Positivism and interpretivism are argued to be the two main paradigms in research philosophy (Collis & Hussey, 2014). This research is conducted from an interpretivist philosophy point of view. The ontological assumption in an interpretivist philosophy is that the reality is socially constructed, that multiple realities can co-exist, meaning that the reality is not static, i.e. more complex (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Therefore, according to Collis & Hussey, interpretivists’ epistemological approach emphasizes qualitative methods rather than quantitative, since it is argued that the measuring of reality is difficult due to its irregularity. Because of this, interpretivists often seek to explain the reality by investigating phenomena derived from non-statistical data (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Based on this perspective, the research design was developed. When writing a dissertation, or thesis, there are two major approaches one can use, inductive and deductive approach. The approach used in this research is based upon the adopted philosophy and the research question: “What Factors Influence Insurance Companies’ Investments in Shared Value Opportunities?”. Being an exploratory study, the recommended research approach is inductive oriented research (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill, 2012). This means that the authors are working in a bottom-top approach. An exploratory study is a paper that, usually, focus on a specific phenomenon or finding in a field-study while trying to draw conclusions and explain these phenomenon or findings by theory (Saunders et al., 2012). Researches can also apply a deductive approach which can be explained as a top-bottom approach, which means that the researcher explores previous research and acknowledged theoretical frameworks, narrowing it down to answering the research question in a more general and theoretical manner (Collis & Hussey, 2014). An exploratory case study process is an iterative, complex process of gathering data which continuously intervenes with the theoretical framework of the thesis (Yin, 2009), See Appendix A. The bottom-top approach, that is, inductive approach, is applied in this research, answering the research question through an exploratory case study backed by theoretical frameworks.

3.2 Research Method

In general, there are two major methods researchers can use, qualitative and quantitative. To develop a method or strategy for “What Factors Influence Insurance Companies’ Investments in Shared Value Opportunities?“ in a specific company one must understand, in-depth, how the business works with these issues and activities in their day-to-day business. In these cases, a

13

qualitative approach is suitable (Saunders et al., 2012). To certify that the knowledge needed for understanding the business would be accomplished, a single company case study was decided upon. As mentioned, it is key to achieve deep knowledge of how a single management works with these kinds of investments to identify the factors influencing the decision-making process. Easterby-Smith, Thorpe & Jackson (2015) tune in on Saunders et al. (2012) that a qualitative approach is suitable when the researchers want to investigate certain circumstances or occurrences. Palinkas, Horwitz, Green, Wisdom, Duan & Hoagwood (2015) argue that quantitative method is suitable when the researchers want to develop superficial knowledge while often including more samples. This method usually emphasizes deductive research. They further claim that qualitative method is suitable when the aim is to gain a deep understanding. Hence, this was the method used throughout the paper.

3.3 Research Strategy

To develop in-depth knowledge of how a business is working with sustainability activities, one should also get a hold on their day-to-day activities and understand their decision-making process. Yin (2009) presents six methods of data collection suitable for case studies and its strengths and weaknesses. Three of these are included in this research, Documents, Interviews and Direct Observations. While the strengths for Documents and Interviews are “stable and

unobtrusive” respectively “targeted and insightful” (Yin, 2009, p. 102), both methods introduce

a risk of biased evidence. To decrease this risk of biased findings, direct observations were included in the data gathering process which Yin (2009) claims is often accompanied with high time consumption and cost. This was, fortunately, not an issue in this paper.

3.4 Data Collection

A clear strategy was set, an exploratory case study gathering data through documentations, direct observations and semi-structured interviews. The interviews were held with all known internal parties influencing the decision-making process regarding sustainability in the company. These individuals and departments were identified through council with the Head of Business Support and Human Resources within the company of study. To reduce the risk of overlooking units influencing these specific decisions, it was evaluated whether there could exist additional managers or units influencing these processes. Subordinates and other managers were considered as possible targets of interviewing, this resulted in additional representatives being included in the sample. The interviews were held at Länsförsäkringar Jönköping’s headquarters in Jönköping, Sweden. Each interview was estimated to endure for 45-90 minutes. In total, the time consumption for these sessions, including compiling of the data, was approximately 32 hours. By interviewing personnel, the researchers can accomplish a solid understanding of how the processes are executed, how decisions are made and what influence them (Yin, 2009). Semi-structured interviews also offer the opportunity to highlight what the interviewed believes is of importance. With the objective of developing an understanding of the day-to-day business and the decision-making process in general, semi-structured interviews is argued by Yin (2009) to be a suitable tool. Nevertheless, multiple sources of evidence, such as direct observations in addition to interviews, could be a way of improving the quality of the information gathered. Because of this, the data collection of this study consists of semi-structured interviews and directs observations. The combination of these sources offers the opportunity to compare the conception of the employees with the business

14

actual practice. As a complement, documentations and forms will be included to enhance the understanding of the business.

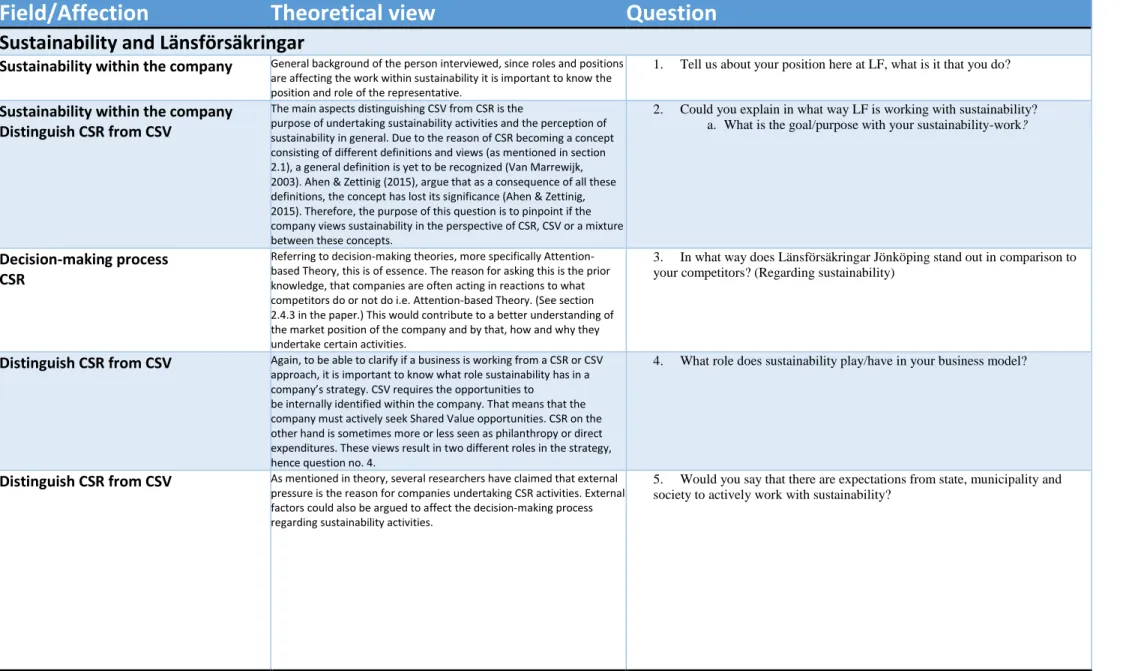

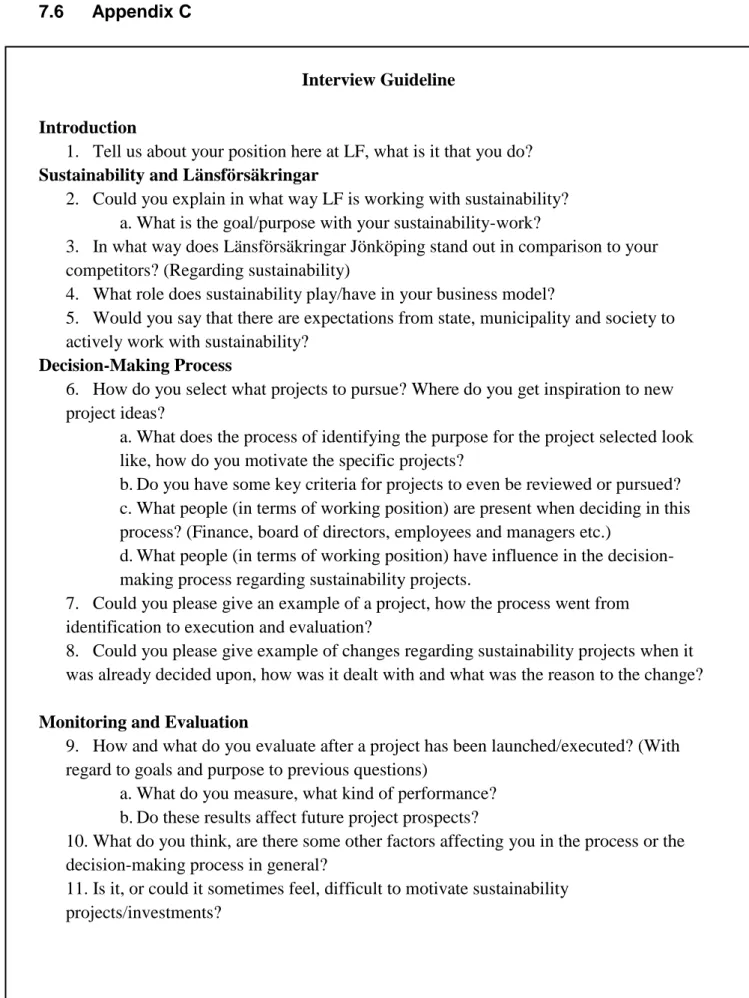

As mentioned in the introduction to this section, the process used throughout the case study itself was acquired from Yin (2009), (See Appendix A). This process shows the iterative and continuous process of an exploratory case study which intends to reflect upon the declared question of issue. Yin further presents a guideline regarding interviews which implies that questions can be categorized into different levels. The levels of questions, more specifically, level one and two constituted the major part of the guideline applied in this study. Level one refers to questions characterized as specific for certain representatives. The second level refers to questions asked in which the authors might already know what kind of answer the representative will express. The main motivation behind structuring the guideline as stated above, was to keep control of the data collection process (Yin, 2009). Prior to the actual interviews, the guideline was tested through an interview held with an employee with insight in the sustainability work within a company. This was done to certify that the guideline was outlined in a manner that would generate the results desired i.e. certify that the answers would become useful for this study. After this test, feedback and the general opinion from the company representative were embraced. The interview guideline was later refined and processed based on the outcome of the test-interview, aiming to optimize the interview sessions held throughout the study. The motivation behind the structure of the interview guideline (Table B1) is presented in Appendix B, showing clearly the intention with each question while the final interview guideline (See Figure C1), used throughout the data collection, is presented in Appendix C. During the semi-structured interviews, many of the representatives answered questions by referring to documents established by the organization. These documents included useful information such as records of limiting fire damages using a fire-extinguisher, operating planning processes and other forms of work conducted by the company. The documents were at the end of each interview submitted through email and later analyzed and included in the compiling of the data obtained. However, these were not included in the appendices of this thesis due to reasons of confidentiality. To make the visualization of the data collected clearer, a compilation of each interview was composed. According to Patton (2015) it is important to organize and register the information obtained for case studies. This is due to his argumentation of case studies not being appointed as an institutional practice. Patton further argues that the data provided in case studies are often being equivalent to the author’s description of the data provided in the report. This leads to the reader not having access to the raw data, i.e. the foundation of the report cannot be critically analyzed. Because of this reason, the compilation of the data obtained increases the reliability of the entire report (Yin, 2009). As a mitigation strategy towards Patton’s (2015) arguments, this paper intends to present undisguised citations as an attempt to enable, for the reader, to critically analyze the data.

3.5 Sampling

When conducting a qualitative research, the processing and sampling of the information obtained is an important process. An agreement with Länsförsäkringar Jönköping was established, which meant that interviews with different employees at Länsförsäkringar could be conducted. What highlighted Länsförsäkringar Jönköping as a promising candidate for this

15

study was their actions in the field of sustainability. According to themselves, Länsförsäkringar has been actively working with sustainability, with the aim of creating business value while simultaneously satisfying societal needs. This makes them a suitable company for this study, due to the fact that it is a Swedish insurance company which claims to Create Shared Value. A limitation of tenindividuals was set, as it is according to Marshall (1996) not practical neither effective, to study entire populations. The sampling approach used in this study is the so-called purposeful sample which, according to Marshall (1996), also is known as the most frequently used sampling method. This method is characterized as the researchers chooses the most valuable representation with the aim to provide an answer, or an explanation, to the pre-established question of issue. Based on this, it provides the researchers to select subjects that align with their research motive and discard the findings that would not be suitable for the specific topic (Marshall, 1996; Devers & Frankel, 2000). In contrast, random sampling would have been applied if the intention was to create some sort of a broad, simplified generalization or a stereotype based on the information. Random sampling does, however, induce a risk of generating a sample that have not implemented the concept of study. It was crucial that the company that were chosen had implemented CSV to be able to investigate what underlying factors affect Shared Value opportunities, meaning that random sampling was not suitable. Purposive sampling is argued to be appropriate when cases, that are considered educational and/or informative, are being used, like in the case of conducting a case study (Tongco, 2007). Devers & Frankel (2000) continue by saying that the purposive sampling method is altered to increase understanding of a group, and/or individual, knowledge and insights (Devers & Frankel, 2000). This is carried out by choosing a group or individuals that possess expert-knowledge in a subject of interest.

The intention with the interviews was to gain both in-depth knowledge of what factors that affect Shared Value opportunities and to receive an overall understanding about the decision-making process. Due to this, one could argue that a criterion sampling would be an appropriate approach, which in turn is a strategy used in order to execute purposive sampling. Criterion sampling is defined as when researchers aim to “Identify and select all cases that meet some

predetermined criterion of importance” (Palinkas et al., 2015). However, according to the

authors, using criterion sampling method could result in an inadequate outcome. By focusing on both big picture understanding and in-depth knowledge could result in capturing neither, since not enough commitment is invested in neither of them (Palinkas et al., 2015). Based on this, it was important to choose information-rich individuals and always keep in mind what knowledge and aspects that were relevant for this study i.e. purposeful sampling was the method used.

3.5.1 Sample Limitations

This research paper was constrained to the Swedish insurance industry, since Länsförsäkringar operates exclusively in Sweden. Because of that reason, the reliability and generalizability of this study might not be applicable outside the insurance industry. A Limitation of ten representants from Länsförsäkringar Jönköping was also present during this study. However, a conjecture that could be made is that this research could create some standardized perception of the differentiation between CSR and CSV. Moreover, it could generate further understanding

16

of how Shared Value could be created in Sweden and what factors that influence how its created, especially in the insurance industry.

3.6 Validity and Reliability

According to Yin (2009) there are four tests that are applicable for case study research to measure its quality. Construct Validity, Internal Validity, External Validity and Reliability, Yin (2009) further uncovers several tactics to deal with these shortcomings and to build a solid quality of the research design. In this study, these tactics have served as guidance in order to achieve validity and reliability.

“Construct Validity” refers to the authors ability to “identify correct operational measures for

the concepts being studied” (Yin, 2009, p. 40). Case studies are, according to Yin (2009) often

considered as insufficient in this aspect and as a counteract to this, multiple sources of evidence were used in the data collection process. Internal Validity is first and foremost regarding explanatory research and not exploratory, therefore, it is not treated as a shortcoming in this paper. External Validity, on the other hand, is argued by Yin to be a “major barrier” (Yin, 2009, p. 43) in legitimizing case studies. The issue is that case studies do not offer a sufficient base for generalizing the research. This can somewhat be treated by unveiling and explaining the background theory in which the result and discussion are based on, as done in this paper. The study must be reliable, meaning that it should be possible for the reader to follow step by step how the research was carried out. The reader should experience similar results if deciding to execute a similar research. By describing and presenting what has been done and why, researchers can enforce the reliability of the paper. Therefore, readers can find information in the methodology section of how this case study was planned, executed and analyzed.

3.7 Data Analysis

This is, as mentioned, a qualitative and inductive research, meaning that the analysis, as well as the data collection, will be executed manually in a bottom-top approach. The theoretical framework presented defines the scope of this research, however, during the analysis of the results, additional frameworks and theories could be included due to the uncertain findings that an exploratory case study could generate. The analysis is focused on identifying factors that have influenced the firm in its undertaking of Shared Value and the decision-making processes accompanied with it. The analysis will be based on the material gathered throughout the case study. These factors will be categorized into two main levels, External and Internal factors. Aguinis & Glavas (2012) categorized influences of corporate responsibility into three levels in which the factors will be sub-categorized into: Institutional, Organizational and Individual factors. The factors will further be evaluated whether they hinder or ease the process of undertaking CSV opportunities.

17

4

Case Study

Länsförsäkringar Jönköping is a company that together with 22 other insurance companies form the Federation Länsförsäkringar, located in Sweden. Länsförsäkringar Jönköping is a mutual insurance company which means that the company is owned entirely by its policyholders. Sustainability constitutes a major part of their business. Even though the awareness of sustainability has grown during the past years, the company has been actively working with sustainability for more than 180 years (Länsförsäkringar Jönköping, n.d.). Their sustainability commitments can be divided into three major areas; People and Society, Local and Global

Environment and Responsible Business. In the organizational structure, the division of

Sustainability and Communication is responsible for managing sustainability within the company. The Head of Sustainability and Communication has stated that the bottom line, in all their activities engaged in sustainability is – and should be – from a perspective that it creates business value. While creating business value, it should also simultaneously satisfy societal needs, i.e. CSV, making it a well-suited company for this study.

The concept of CSV suggests that the purpose of undertaking social activities should be from a business perspective. Porter & Kramer (2011) introduced, as presented in section 2.2.1, three ways in which companies can Create Shared Value. In the insurance industry, the society is the market, meaning that factors impacting society also have a direct impact on the business in terms of costs or profits. While, this makes the insurance industry a well-suited prospect for implementing the concept of CSV, the increased frequency and complexity that climate change, theft and other events, that bear increased risk-uncertainty, obstructs the core function of an insurance business. As a counteract to this, many insurance companies have started to undertake activities improving the safety and security in society with the aim to decrease costs, so-called accident prevention. Projects such as, financing water barriers, handing out fire extinguishers and educating farmers and other important policyholders in how to prevent accidents i.e. the aim is to Create Shared Value. All these actions can be categorized in Redefining Productivity

in the Value Chain, whereas policyholders are part of the value chain in terms of being the end

customer and the supplier. Länsförsäkringar is a company that focus on their local region, aiming to improve and aid companies, agriculture and other associations in their proximity, meaning that they Create Shared Value by Enabling Local Cluster Development. While it has been observed that these are Länsförsäkringar’s primarily ways of Creating Shared Value, it has also been discovered that, to some extent, they are Creating Shared Value through

Reconceiving Products and Markets.

During this case study, ten representatives from Länsförsäkringar were interviewed, five internal documents and direct observations were used. In the table below, the position of the persons interviewed, duration and in what way the interviews were carried out is presented as well as the content of the documents used, see Table 1. Each representative was assigned a randomly chosen label of “Employee 1-10” to guarantee anonymity. After composing the case study notes, examining the documents and observing the business environment, the factors shown in Table D1 (See Appendix D) were identified and later categorized as described in section three. While several factors were identified as influencing the firm’s investments in Shared Value, not all were further elaborated and discussed in this paper. Factors that were identified as bearing a more severe potential impact and where there was sufficient foundation

18

for discussion were reviewed in the following section. This means that not all factors presented in Table D1 (See Appendix D) will be discussed and explained due to the increased risk of jeopardizing the trustworthiness of this paper.

Position

Interview Manner Duration (minutes)Head of Sustainability and Communication In-person 60

Marketing Manager In-person 55

Head of Claim Adjusters – Movable goods In-person 46

Head of Agriculture Insurances In-person 32

Head of Business Support and Human Resources In-person 38

Accident Preventer In-person 53

Insurance Sales Agent In-person 30

Insurance Sales Agent Videocall 68

Insurance Sales Agent In-person 55

Insurance Sales Manager In-person 34

Document

Content

Randstad Employer Brand Research – Länsförsäkringar

A research of Länsförsäkringar brand and what role sustainability plays in attracting new workforce.

Table of Accidents Prevented Showing saved expenses by actively working with preventing accidents and damages.

Circular Accident Management Explaining the way of operating with circular accident management.

Sustainability Policy Declaring and explaining Länsförsäkringar Jönköping’s sustainability policy.

Business and Operating Process Declaring and explaining in what why

Länsförsäkringar should operate and what factors that could affect them in their business.

Annual Report 2019 Länsförsäkringar Jönköping’s annual report, presenting financials and contains a sustainability report.

19

5

Analysis

In this section, the findings derived from the information obtained from direct observations, documents and the interviews held at Länsförsäkringar Jönköping are exhibited and deliberated. The discussion of the factors selected, in what way they influence investments in Shared Value, is based on the representative's perception of how these factors influence Shared Value opportunities. The theoretical framework functions as a foundation when explaining the factors presented in which conclusions later could be drawn from. Undisguised citations are included in order to demonstrate thoughts, views and statements expressed by the representatives.

5.1 Factors Influencing Shared Value Opportunities 5.1.1 Institutional

5.1.1.1 Increased Demand of Sustainability from Coming Generations

According to Ranstad Employer Brand Research (See Table 1), carried out on the behalf of Länsförsäkringar, consisting of over 200 000 representatives, 96% of the population considers that the corporate culture must be consistent with their personal values and beliefs. Furthermore, the research presented the sixteen most common valued factors when considering working for a certain employer. Amongst these factors, societal undertakings in the shape of “giving back to society” was one of the most valued. The research presents evidence of an increase in valuing an organization’s effort in giving back to society. This is also supported by Sullivan et al. (2006) research suggesting that a company could face difficulties in the shape of losing, amongst others, employees if not acting upon the increased interest in social responsibility. This is something that Employee 2 also expresses by saying;

Today, it is imperative for people who are searching for jobs, especially the younger generation, to ask what companies do and what companies stand for in terms of sustainability. Generally, what young people value and appreciate, with an employer in today's society, is often connected to what the company does for the society. Young people tend to choose future employers based on other factors than just making money. You want to be a part of something bigger.

− Employee 2

This implies that in order to be attractive in the eyes of future employees, i.e. staying competitive, Länsförsäkringar must show, by actions, that they do not exclusively focus on delivering the best product or service. There exists a demand from the coming generations to undertake social responsibility. Due to this reason, it could be argued that an increase in demand for sustainability could ease the process of implementing Shared Value opportunities. This is based on the fact that by motivating sustainability actions, it could lead to Länsförsäkringar acquiring competitive advantage in terms of being an attractive employer. However, just because the motivation behind pursuing social undertakings exists, does not necessarily indicate that Shared Value is created. But with undertaking social responsibility with the aim of attracting the employees of tomorrow creates value in synergy, making it Shared Value.